Abstract

Lysine malonylation (Kmal) is a novel post-translational modification (PTM) implicated in numerous biological processes. Our recent study finds that human sperm proteins are modified by Kmal, but the functional significance of Kmal in human sperm remains unclear. The present study shows that Kmal primarily occurs in human sperm tail proteins with molecular weights ranging from 15 to 250 kDa. Similar to somatic cells, Kmal is derived from malonyl-CoA, with acyltransferase P300 and sirtuin 5 (SIRT5) potentially acting as the writer and eraser, respectively, for Kmal in human sperm. The Kmal level in asthenozoospermic sperm is significantly higher than that in normozoospermic sperm and exhibits a negative correlation with progressive motility. Elevated Kmal levels in asthenozoospermic sperm are associated with reduced sperm SIRT5 and ATP levels, as well as inhibited glycolysis. Furthermore, the induction of sperm Kmal by sodium malonate significantly diminishes the motility and penetration ability of normozoospermic samples by reducing sperm [Ca2+]i, ATP, and cAMP levels, and by suppressing glycolysis and PKA activity. Our findings elucidate the regulatory function of Kmal in human sperm motility and its association with asthenozoospermia, thereby offering insights for the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic male infertility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The polypeptide chain requires further processing and modifications following synthesis in order to become functional proteins1. Among the modified amino acid residues, lysine residues, which carry a positive charge, are particularly vital for modulating protein function. This makes protein lysine modification (PLM) a primary focus in functional PTM research2. To date, hundreds of PLMs have been identified on lysine residues of both histones and non-histone proteins in mammalian cells3. Lysine short-chain acylations, such as lysine methylation and acetylation (Kac), are important types of PTMs. Between 2010 and 2020, dozens of novel lysine short-chain acylations, such as lysine malonylation (Kmal), succinylation (Ksucc), glutarylation (Kglu), crotonylation (Kcr), 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation, and lactylation, were identified. These modifications participate in diverse biological events and play important roles in many pathological processes4.

Kmal is a novel lysine short-chain acylation discovered in 20115. It alters the charge of substrate proteins from +1 to −1 by adding a malonyl group to the side chain of the lysine residue5. Studies on the Kmal regulatory system have revealed that malonyl-CoA may serve as a precursor for the lysine malonylation reaction in mammalian cells, while lysine deacetylase sirtuin 5 (SIRT5) serves as an eraser for Kmal to remove malonyl from substrate proteins5. The knockout of SIRT5 results in elevated Kmal levels, which in turn disrupt mitochondrial function6, indicating a role for Kmal in cellular energy metabolism. Interestingly, individuals with short-term abstinence show improved sperm quality, including higher sperm concentration, motility, vitality, normal morphology, acrosome reaction capacity, and total antioxidant capacity, but lower Kmal levels compared to those with long-term abstinence7, suggesting a negative association between Kmal and sperm quality. However, the function of Kmal in human sperm remains unclear.

Sperm are transcriptionally and translationally silent cells, and their functional regulation is proposed to depend more on PTMs than other somatic cells8,9. For instance, phosphorylation is widely recognized to play a role in several biological processes essential for sperm motility, capacitation, hyperactivation, and the acrosome reaction10. Lysine short-chain acylations are also involved in the modulation of sperm functions. Lysine acetylation occurs on multiple human sperm proteins and is important for sperm functions11,12. Our previous studies showed that lysine glutarylation and lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation affect human sperm motility, and their abnormal levels in human sperm are related to asthenozoospermia13,14. In a mouse model of high-fat diet-induced obesity, we found that low sperm motility is associated with an increased testicular Kmal level15. In addition, our recent proteomic study identified 196 malonylated sites in 118 human sperm proteins, which are enriched in metabolic and signaling pathways, such as glycolysis and the calcium signaling pathway16. Glycolysis is a crucial source of ATP, which provides the energy necessary for maintaining human sperm motility17,18,19. Concurrently, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is derived from ATP and activates protein kinase A (PKA) to stimulate hyperactivated motility and penetration ability20. In addition, Ca2+ plays a vital role in human sperm motility21. These results suggest the functional role of Kmal in human sperm motility.

In this study, the regulators of Kmal (“writer”, “eraser”, and cofactor) were investigated in human sperm. The levels of Kmal, SIRT5, ATP, and glycolysis were examined in asthenozoospermic and normozoospermic sperm, and differences in these parameters were compared between asthenozoospermic and normozoospermic sperm. The association of sperm Kmal with progressive motility was evaluated. In addition, the functional roles of Kmal in sperm motility, glycolysis, the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway, and the calcium signaling pathway were validated by elevating the sperm Kmal level via sodium malonate (Na2-mal) in normozoospermic sperm. The findings indicate that lysine malonylation in human sperm may play a regulatory role in sperm motility through its involvement in energy metabolism and signal transduction pathways within the sperm tail.

Results

Kmal occurs mainly in the proteins of human sperm flagella

Western blot analysis of human sperm total protein (TP) using a validated pan-anti-malonyllysine antibody revealed that Kmal modifications occur in multiple proteins ranging from 10 to 250 kDa (Fig. 1A). Protein fractions specific to the sperm head, mitochondrion, and cytoplasm were extracted from human sperm and validated by Western blot using the corresponding markers: PRM2 for the sperm head (Head, Fig. 1A), COX6B1 for the mitochondrion (Mit, Fig. 1A), and ACTIN for the cytoplasm (Cyt, Fig. 1A). Lysine-malonylated proteins were predominantly localized in the sperm cytoplasm and mitochondria (Fig. 1A). Additionally, immunofluorescence assays imaged by laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM, Fig. 1B) and super-resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM, Fig. 1C) confirmed that Kmal modifications are primarily present in the proteins of the human sperm flagella, which contain mitochondria and cytoplasm. No fluorescence was observed in the negative control when the anti-Kmal antibody was replaced with nonspecific IgG (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A The Kmal in total proteins of (TP) and protein fractions of the mitochondrion (Mit), head, and cytoplasm (Cyt) isolated from human sperm were examined by Western blot. The specificity of cellular components was validated by Western blot using the corresponding markers: PRM2 for sperm head, COX6B1 for mitochondrion, and ACTIN for cytoplasm. The proteins for Western blot were shown in the coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining image. B, C The localization of malonylated proteins within human sperm was investigated by immunofluorescence assay via laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM, (B)) and super-resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM, (C)). All the experiments were conducted with samples from 8 normozoospermic men. The scale bar represents 5 μm.

Regulatory enzymes and cofactor for Kmal in human sperm

The results of the Western blot demonstrated that 0.5 and 1 μM C646, a histone acetyltransferase P300 inhibitor, decreased the global level of lysine acetylation in human sperm, indicating that C646 is effective in inhibiting P300 in human sperm (Supplementary Fig. 2). At these concentrations, C646 also reduced the global Kmal level in human sperm, as evidenced by the results of the Western blot (Fig. 2A) and immunofluorescence assay (Fig. 2B, G). These results suggest that P300 may serve as a “writer” for Kmal in human sperm.

Human sperm were exposed to different concentrations of C646, nicotinamide (NAM), and sodium malonate (Na2-mal) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. The effect of the P300 inhibitor C646 on the human sperm Kmal level at concentrations of 0.5 and 1 μM was examined by western blot (A) and immunofluorescence assay (B). The effect of sirtuin inhibitor NAM on the human sperm Kmal level at concentrations of 20 and 40 mM was assessed by western blot (C) and immunofluorescence assay (D). The effect of Na2-mal on the human sperm Kmal level at concentrations of 20 and 40 μM was evaluated by western blot (E) and immunofluorescence assay (F). G–I Conduct a semi-quantitative statistical analysis of the fluorescence intensity representing Kmal modification in the various treatment groups, with normalization to the parallel control group. For the immunofluorescence assay, laser scanning confocal microscopy was utilized to detect the presence of Kmal in human sperm. Scale bars in the images represent 5 μm. Data points represent mean ± SEM of n = 8 biologically independent samples. Statistical analysis was performed via one-way analysis of variance to determine differences between the control and Na2-mal-treated groups. Non-significant (ns) values are indicated for p values greater than 0.05, while *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were used to denote statistical significance compared with the control group.

In this study, we investigated whether histone deacetylases are involved in demalonylation in human sperm. TSA, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase class I/II, was found to suppress lysine deacetylation in human sperm but did not affect the Kmal level (Supplementary Fig. 3). NAM, an inhibitor of sirtuins, not only elevated the global level of lysine acetylation (Supplementary Fig. 2) but also increased the global level of Kmal in human sperm at concentrations of 20 and 40 mM (Fig. 2C, D, H). These results are consistent with previous studies indicating that SIRT5 possesses demalonylase enzymatic activity in somatic cells5, suggesting that SIRT5 may function as an “eraser” for Kmal in human sperm.

In somatic cells, malonyl-CoA serves as the precursor for Kmal. Na2-mal can enter cells and be converted into malonyl-CoA, which is then used in the lysine malonylation reaction. Intriguingly, Na2-mal (20 and 40 μM) also increased the levels of Kmal in human sperm (Fig. 2E, F, I). However, Na2-mal did not affect the levels of other short-chain lysine acylations structurally similar to Kmal, including lysine acetylation, crotonylation, succinylation, glutarylation, 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation and benzoylation (Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition, malonyl-CoA is generated by the action of ACC and is utilized by FASN in somatic cells5,6. Immunofluorescence assays revealed that ACC1 and FASN are localized in the middle piece of human sperm flagellar (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, neither TOFA, a cell-permeable ACC inhibitor, nor the FASN inhibitor cerulenin affected human sperm Kmal levels (Supplementary Fig. 4). These results indicate that malonyl-CoA acts as a cofactor for human sperm Kmal, but its metabolism may differ from that in somatic cells.

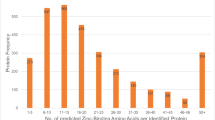

Asthenozoospermic sperm are associated with increased Kmal levels, reduced SIRT5 and ATP levels, and inhibition of glycolysis

To investigate whether human sperm Kmal is related to asthenozoospermia, we examined the sperm Kmal levels in 53 normozoospermic men and 41 asthenozoospermic men using Western blot. The results demonstrated that the mean level of sperm Kmal in asthenozoospermic men was significantly elevated compared to that in normozoospermic men (1.38 vs. 1.00, Fig. 3A, B). A negative relationship between sperm Kmal levels and the progressive motility of human sperm was found by linear regression analysis (Fig. 3C). Based on the highest value of relative Kmal levels in normozoospermic men (1.51, Fig. 3B), there were 10 asthenozoospermic men whose sperm Kmal levels exceeded 1.51 (the red box in Fig. 3B). The semen parameters for the 10 asthenospermic patients are summarized in Table 1. Notably, the sperm glycolysis and ATP level were significantly lower in these ten asthenozoospermic men than in normozoospermic men (Fig. 3D, E). Further linear regression analysis revealed that sperm progressive motility and intracellular ATP levels were inversely correlated with Kmal levels (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, the relative sperm SIRT5 level in asthenozoospermic men decreased significantly compared to normozoospermic men (Fig. 3F). Linear regression analysis revealed a negative correlation between Kmal levels and SIRT5 level in human sperm (Fig. 3G).

The levels of Kmal and SIRT5 were analyzed in 53 normozoospermic men (NOR) and 41 asthenozoospermic men (AST) by western blot. A An example illustrating the presence of sperm Kmal and SIRT5 in AST and NOR. B Semi-quantitative analysis of Kmal in NOR and AST was conducted as outlined in the “Materials and methods” section. The red box indicates 10 AST whose sperm Kmal levels exceeded 1.51, the highest value of relative Kmal levels in NOR. C Correlations between sperm Kmal and progressive motility in 94 samples were evaluated through linear regression analysis. The glycolysis (D) and ATP level (E) were examined in 10 AST indicated in the red box in Fig. 3B. F Semi-quantitative analysis of SIRT5 in NOR and AST was conducted as outlined in the “Materials and methods” section. G Correlations between sperm Kmal and SIRT5 in 94 samples were assessed through linear regression analysis. The error bars represent the means ± SEM. The differences between NOR and AST were analyzed by unpaired t-test with statistical significance indicated by *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001.

Elevation of sperm Kmal by Na2-mal reduces the motility and penetration ability of normozoospermic samples

Since Na2-mal could specifically increase the human sperm Kmal level (Fig. 2E, F and Supplementary Fig. 2), we examined whether Na2-mal affected sperm functions. After 1-, 2-, and 4-h exposures, 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal had no cytotoxicity to human sperm (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 6A), but significantly compromised total motility (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 6B) and progressive motility (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 6C). In addition, 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal significantly reduced the number of human sperm that penetrated the 1 and 2 cm of the 1% methylcellulose solution after 1-h exposure (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. 6D). These results indicate that the elevation of human sperm Kmal affects both basal motility and motility in the viscous medium.

Human sperm were exposed to 0, 20, and 40 μM Na2-mal at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for durations of 1 h. Sperm viability (A), total motility (B), and progressive motility (C) were examined as outlined in the “Materials and methods” section. D For assessment of the effect of Na2-mal on penetration ability, capacitated human sperm were incubated with 0, 20, and 40 μM Na2-mal for 1 h. Capillary tubes filled with 1% methylcellulose were inserted into the sperm mixture and the sperm were allowed to penetrate upward through the methylcellulose solution for 60 min. The sperm counts were measured at distances of 2 cm from the capillary base. The cell numbers in each group were normalized to the mean number of the “0” group (control group). Data points represent mean ± SEM of n = 8 biologically independent samples. Statistical analysis was performed via one-way analysis of variance to determine differences between the control and Na2-mal-treated groups. Non-significant (ns) values are indicated for p values greater than 0.05, while *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were used to denote statistical significance compared with the control group.

Na2-mal decreases sperm [Ca2+]i, ATP, and cAMP, and suppresses glycolysis and PKA activity

To investigate the potential mechanisms by which Kmal regulates human sperm motility, we examined the effects of Na2-mal on mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), glycolysis, ATP levels, the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway, and calcium signaling pathways in human sperm. We observed that 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal did not affect the MMP in human sperm, but CCCP, an oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler, significantly reduced MMP in human sperm, serving as a positive control (Fig. 5A). Sperm glycolysis was significantly inhibited by 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal (Fig. 5B). As expected, ATP levels in human sperm decreased following exposure to 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal (Fig. 5C). Since ATP can be converted to cAMP, which stimulates the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway to activate sperm functions, we assessed the cAMP levels in human sperm. IBMX, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, significantly increased the cAMP level in human sperm (Fig. 5D), indicating that the cAMP detection system was functional. Na2-mal reduced the cAMP level in human sperm at concentrations of 20 and 40 μM (Fig. 5D). Given that Na2-mal lowered the cAMP level in human sperm, we examined whether PKA activity was affected by Na2-mal. Similar to the PKA-selective inhibitor Rp-cAMPS, 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal significantly decreased the overall phosphorylation levels of PKA substrate proteins in both non-capacitated and capacitated human sperm (Fig. 5E, F). To explore downstream signaling pathways affected by Na2-mal induced lysine malonylation, we examined the phosphorylation levels of PDK1 and PPP1R2, two critical proteins involved in the regulation of sperm motility, in normozoospermic human sperm following Na2-mal treatment. Our findings revealed that exposure to Na2-mal significantly diminished the phosphorylation of both PDK1 and PPP1R2 (Supplementary Fig. 7). Additionally, since calcium signaling is essential for sperm motility, we assessed the influence of Na2-mal on [Ca2+]i in sperm. The [Ca2+]i in human sperm was gradually reduced by 50–60% after exposure to 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal for 5 min (Fig. 5F, G). Although CATSPER is the predominant calcium channel in human sperm, we did not find that 20 and 40 μM of Na2-mal affected the CATSPER current in human sperm (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Human sperm were exposed to 0, 20, and 40 μM Na2-mal at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h. A The mitochondrial membrane potential was determined by the ratio of the fluorescent intensity of JC-1 aggregate/monomer. The fluorescence of JC1 was detected by a PerkinElmer EnSpire® Multimode Plate Reader. CCCP (10 μM), an oxidative phosphorylation uncoupler, was used as a control. n = 9 biologically independent samples. The glycolysis (B, n = 8 biologically independent samples), ATP level (C, n = 8 biologically independent samples), and cAMP level (D, n = 6 biologically independent samples) were examined using commercial kits as outlined in the “Materials and methods” section. The PKA activity in both non-capacitated (E) and capacitated (F) human sperm was assessed by quantifying the levels of its phosphorylated substrates through Western blot analysis. The coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining image showed the proteins for western blot. RpcAMP, a membrane-permeable competitive cAMP antagonist that blocks PKA activation, was used as a control. G, H The [Ca2+]i in human sperm was assessed by the fluorescent changes of the calcium probe (Fluo-4 AM) via an EnSpire® Multimode Plate Reader as outlined in the “Materials and methods” section. n = 6 biologically independent samples. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed via One-way ANOVA. Non-significant (ns) values are indicated for p values greater than 0.05, while *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were used to denote statistical significance compared with the control group.

Lysine glutarylation of GAPDHS and VDAC3 was significantly increased in asthenozoospermia, and Na2-mal exposed normaspermia

In our prior investigation into the malonylome profiling of human sperm16, we identified that GAPDHS (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, testis-specific), a critical enzyme in glycolysis, and VDAC3 (voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 3) undergo malonylation in human sperm. To elucidate the functional significance of these post-translational modifications, we conducted co-immunoprecipitation assays utilizing an anti-Kmal antibody to evaluate the malonylation levels of GAPDHS and VDAC3 in human sperm. Our findings revealed that treatment with sodium malonate (Na₂-mal) markedly enhanced the malonylation levels of both GAPDHS and VDAC3 in normozoospermic sperm (Supplementary Fig. 9). Furthermore, sperm from asthenozoospermic individuals displayed increased malonylation of GAPDHS and VDAC3 in comparison to normozoospermic controls (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Discussion

Lysine short-chain acylations are important types of PTMs that participate in diverse biological events and play crucial roles in many pathological processes4. In our recent study, we found that Kmal, a novel short-chain acylation, is enriched in energy metabolism and signaling transduction pathways, such as glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, tricarboxylic acid cycle, cAMP-PKA pathway, and calcium signaling pathway16. These pathways are essential for maintaining human sperm motility22. To explore the potential mechanisms by which Kmal regulates human sperm motility, we examined the effects of Na2-mal on MMP, glycolysis, ATP levels, the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway, and calcium signaling pathways in human sperm. The results reveal that asthenozoospermia was associated with increased sperm Kmal level, reduced ATP level, and declined glycolysis. Sperm Kmal level was negatively correlated with progressive motility. In addition, the elevation of sperm Kmal significantly compromised the motility and penetration ability of normozoospermic samples by decreasing sperm [Ca2+]i, ATP, and cAMP, and suppressing glycolysis and PKA activity. These results indicate that lysine malonylation in human sperm regulates sperm motility via energy metabolism and signaling transduction pathways in the sperm tail.

In this study, we observed a decrease in sperm PKA activity following in vitro exposure to Na2-mal. This reduction may be attributed to two potential mechanisms: (1) Our recent malonylome analysis of human sperm16 indicates that both the binding and catalytic subunits of PKA are malonylated proteins. We hypothesize that Na2-mal directly modulates enzyme activity by influencing the Kmal level of PKA; (2) Na2-mal inhibits glycolysis and decreases the levels of ATP and cAMP in human sperm, and subsequently reduces PKA activity. Further in vitro experiments are essential to validate these findings in future research.

This study found that the elevation of Kmal declined human sperm progressive motility and [Ca2+]i without affecting the CATSPER current. Given that CATSPER is essential for sperm hyperactivation but not for progressive motility, it is suggested that Kmal may impede the progressive motility of human sperm by influencing other signaling pathways. On one hand, VDAC3 is a mitochondrial membrane protein that regulates the entry and exit of anions, cations, and ATP into and out of mitochondria. It plays a crucial role in regulating intracellular calcium homeostasis23. Mice lacking VDAC3 are infertile due to decreased sperm motility24. Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated the distribution of VDAC in the midpiece surface of human sperm flagellum, and an anti-VDAC antibody can reduce sperm motility by inhibiting the transmembrane flow of Ca2+ 25. In humans, the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) necessary for sperm motility is predominantly produced via glycolysis. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, spermatogenic (GAPDHS), serves as a pivotal regulator of this metabolic pathway, with empirical evidence indicating a positive correlation between its protein expression levels and enzymatic activity in human sperm and sperm motility18,19,26. Interestingly, our recent malonylome data of human sperm identified the Kmal in VDAC3 and GAPDHS16. In this study, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays to quantify Kmal levels on GAPDHS and VDAC3 in both normozoospermic and asthenozoospermic sperm, as well as in normozoospermic sperm treated with Na₂-mal. The results demonstrated a significant increase in Kmal modification of both GAPDHS and VDAC3 in asthenozoospermia compared to normozoospermia (Supplementary Fig. 9). Similarly, Na₂-mal treatment led to elevated Kmal levels on these proteins in normozoospermic sperm (Supplementary Fig. 9). These findings, combined with our observed reductions in glycolytic output and intracellular calcium levels upon Na₂-mal exposure, strongly suggest that excessive malonylation of GAPDHS and VDAC3 contributes to the functional deficits in sperm motility by impairing energy production and calcium signaling.

The present study indicated that human sperm has a similar regulatory system for Kmal to that of somatic cells. Na2-mal is transported into cells and converted to malonyl-CoA, which can increase Kmal in human sperm, indicating that the malonyl-CoA serves as the cofactor for Kmal in human sperm. Our observations suggest that the Kmal levels in sperm from individuals with asthenozoospermia are significantly elevated compared to those in normozoospermia. This finding prompts an inquiry into whether these differences can be attributed to variations in malonyl-CoA levels between asthenozoospermia and normozoospermia. In addition, the sirtuin inhibitor nicotinamide (NAM) and the P300 inhibitor C646 could upregulate and downregulate Kmal levels in human sperm, respectively. SIRT5, a member of the sirtuin family, is a key upstream regulatory enzyme of Kmal in HeLa and HepG2 cells5. By screening the sperm samples, we found that SIRT5 is negatively correlated with Kmal in human sperm and decreased in asthenozoospermic sperm. These results indicate that SIRT5 may be an “eraser” for Kmal in human sperm and is related to asthenozoospermia. Notably, NAM and C646 can also influence the levels of Kglu, Khib, and Kac in human sperm13,14. To further validate the regulatory roles of P300 and SIRT5 on Kmal, we first transfected GC-1 cells with SIRT5 siRNA and a P300 overexpression plasmid, respectively. The results showed that SIRT5 siRNA transfection significantly reduced both mRNA and protein levels of SIRT5 (Supplementary Fig. 10A–C) and increased the level of Kmal modification (Supplementary Fig. 10D) compared with the control group. In contrast, transfection with the P300 plasmid markedly elevated P300 expression at the mRNA and protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 10E–G) and decreased Kmal levels (Supplementary Fig. 10H). Neither SIRT5 knockdown nor P300 overexpression significantly affected the viability of GC-1 cells compared to wild-type controls (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Subsequently, we performed lentiviral pinpoint injection into the mouse testicular tissue. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed successful transduction of testicular germ cells by lentiviruses carrying the P300 overexpression plasmid or sh-Sirt5 constructs (Supplementary Fig. 12). Hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed no obvious structural alterations in the testicular tissue of lentivirus-injected mice compared to wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 13). Interestingly, in epididymal sperm from lentivirus-injected mice, the expression level of P300 was upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 14A and Supplementary Fig. 15), while SIRT5 was downregulated (Supplementary Fig. 14B and Supplementary Fig. 16), accompanied by a significant increase in Kmal levels (Supplementary Fig. 14C and Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Fig. 16). Although sperm concentration (Supplementary Fig. 17A) and normal morphology (Supplementary Fig. 17B) remained comparable between the groups, the forward motility rate of sperm was significantly reduced in lentivirus-injected mice (Supplementary Fig. 17C). These findings demonstrate that SIRT5 and P300 act as upstream regulatory enzymes of Kmal in germ cells. Alterations in Kmal modification do not affect GC-1 cell survival but impair the motility of mature epididymal sperm. Moreover, exposure to Na2-mal did not affect mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) levels in normozoospermia but inhibited glycolysis. Notably, the glycolysis in asthenozoospermia with elevated Kmal levels is considerably lower than that in normozoospermia. These findings imply that Kmal primarily disrupts intracellular ATP synthesis by impacting glycolysis rather than mitochondrial function.

To investigate whether alterations in Kmal are indicative of upstream defects during spermatogenesis or are secondary to abnormal metabolism in mature sperm, we conducted complementary in vitro experiments utilizing GC-1 cells. These experiments were designed to assess the direct impact of Na₂-mal on Kmal levels and cell viability. Our findings reveal that Na₂-mal treatment resulted in a significant increase in Kmal levels in GC-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 18A). Notably, CCK-8 assays confirmed that this increase in Kmal did not significantly compromise cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 18B), thereby excluding potential confounding cytotoxic effects. These results suggest that the elevation of Kmal can occur independently of substantial metabolic disruption in developing germ cells and may represent a regulatory event with functional significance.

Although dozens of lysine short-chain acylations have been identified4, only lysine methylation27, Kac11, Kmal16, Ksucc16, Kglu13, Kcr16, and lysine 2-hydroxyisobutylation14 have been reported in human sperm. All these modifications are associated with asthenozoospermia. Our recent acylomic data showed that Kac, Kmal, Ksucc, and Kcr occur in glycolysis-related and motility-related proteins16. In addition, the “writer” (P300) and “eraser” (SIRT5) modulate the sperm levels of Kac11, Kmal, Kglu13, and lysine 2-hydroxyisobutylation14. Both of the proteins are localized in the flagellum of human sperm13. Furthermore, the cofactors (short-chain acyl-CoA) corresponding to these modifications are closely related, and the content changes affect each other4. These results indicate that Kmal in human sperm might affect the energy metabolism crucial for sperm movement and may be involved in the development of male infertility. Therefore, the crosstalk of these modifications in sperm and how they coordinate to regulate human sperm motility is a topic worthy of study.

Our prior research, along with the findings of this study, demonstrates that in asthenozoospermia, Kglu levels are downregulated, whereas Khib and Kmal levels are upregulated, and intracellular ATP levels are diminished, in comparison to normozoospermia13,14. A recent study has identified substrate proteins in normozoospermia that are modified by Kmal, indicating that numerous key regulatory proteins involved in glycolysis possess Kmal sites16. We identified specific lysine residues that are targeted by malonylation in key proteins involved in energy metabolism and calcium regulation. Notably, lysine 287 (K287) in GAPDHS was found to undergo malonylation. Additionally, lysine residues at positions 12, 20, 28, and 63 (K12, K20, K28, and K63) in VDAC3, a mitochondrial channel involved in calcium and ATP flux, were also malonylated. In this study, treatment with Na₂-mal resulted in a significant reduction in both L-lactate production and intracellular calcium levels in human sperm. These observations prompt the question of whether these modifications might influence sperm motility by affecting the same lysine residue sites of key regulatory proteins involved in sperm energy metabolism. This hypothesis could be tested through mutagenesis of the malonylation site, enzyme activity assays, or reconstitution in a functional in vitro model. Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether the types and levels of modifications (Kglu, Khib, and Kmal) at these lysine residue sites in asthenozoospermia differ from those in normozoospermia. Further research is warranted to integrate proteomics with specific lysine modification omics approaches to facilitate a comparative analysis of differentially modified proteins and lysine sites in both normal and asthenozoospermic sperm. This research should aim to elucidate the spatiotemporal interactions between modifications and identify key regulatory proteins involved in sperm energy metabolism that possess multiple modification sites. These proteins may regulate sperm motility through two primary mechanisms: (1) The synergistic regulation of substrate protein function by various types of modifications occurring at distinct lysine sites; (2) The alteration of substrate protein function due to the competitive effects of different modifications at the same lysine residue sites.

In conclusion, this investigation focused on the function of a novel lysine short-chain acylation, Kmal, in human sperm. The results demonstrated that Kmal negatively regulates progressive motility by affecting glycolysis, cAMP-PKA signaling pathway, and calcium signaling pathway in human sperm. Our findings indicate the regulatory role of Kmal in human sperm motility and the association of sperm Kmal with asthenozoospermia, providing potential targets for future research into male infertility.

Methods

Reagents

Anti-Kmal antibody (PTM-901), anti-Kac antibody (PTM-101), anti-Ksucc antibody (PTM-419), anti-Kcr antibody (PTM-501), anti-Kglu antibody (PTM-1151), anti-Khib antibody (PTM-801), and anti-Kbz antibody (PTM-762) were obtained from PTM BioLabs Inc. (Hangzhou, China). Anti-ACTIN antibody (66009-1-Ig), anti-SIRT5 antibody (67257-1-Ig), anti-acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) antibody (21923-1-AP), anti-fatty acid synthase (FASN) antibody (10624-2-AP), anti-protamine 2 (PRM2) antibody (14500-1-AP), anti-GAPDHS (83290-3-RR) and anti-VDAC3 (82666-14-RR) were obtained from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Rosemont, IL, USA). Anti-cytochrome c oxidase subunit 6B1 (COX6B1) antibody (ab110266), anti-P300 antibody (ab14984), and anti-PPP1R2 antibody (ab27850) were purchased from Abcam Limited (Cambridge, UK). The phospho-PKA substrate (RRXS*/T*) rabbit antibody (9624S) was procured from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-PDK1 antibody (Ab-241) was obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). The HRP- or fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies and the rabbit (or mouse) IgG were acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). C646 (HY-13823), Trichostatin A (HY-15144, TSA), nicotinamide (HY-B0150, NAM), Na2-mal (HY-W017165), TOFA (HY-101068), cerulenin (HY-A0210), carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (555-60-2, CCCP), 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; Isobutylmethylxanthine (28822-58-4, IBMX), Rp-cAMPS (73208-40-9), and JC-1 (HY-15534) were obtained from MedchemExpress LLC. (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Solarbio Life Sciences (Beijing, China) provided the 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, C0065).

Sperm sample collection

Semen samples were collected through masturbation after 3–5 days of sexual abstinence from men who attended the Yichun People’s Hospital (Yichun, China) between March 2022 and December 2024. The selection of donors adhered to the criteria outlined in the Fifth Edition of the World Health Organization Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. The reproductive history of normozoospermic men had been documented within the past two years, and these men exhibited a progressive motility of ≥32%, whereas asthenozoospermic men demonstrated a progressive motility of <32%. Participants in this study were aged 20–39 years. To ensure the integrity of the study, certain individuals were excluded based on specific medical criteria, including varicocele, prostatitis, or other disorders related to the endocrine or metabolic systems. A total of 53 normozoospermic men and 41 asthenozoospermic men participated in the investigation, and the sample size was determined via a power calculation conducted using G*Power 3.028. The semen parameters of the donors are exhibited in Table 2.

Human sperm preparation and treatment

Following half an hour of liquefaction at 37 °C, sperm samples collected from individuals with normozoospermia were subjected to purification via Percoll gradient density centrifugation. This process was employed to remove somatic cells and obtain relatively uniform, high-quality sperm. The collected purified sperm were subsequently washed with a (2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) solution composed of 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 5 mM glucose, 1 mM Na-pyruvate, 10 mM lactic acid, and 20 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 using NaOH, to remove any residual Percoll. The cell precipitate was subsequently resuspended in the HEPES solution, maintaining the sperm in an uncapacitated state. For chemical administration, purified sperm were treated with C646 (0.5 and 1 μM), 20 and 40 mM NAM, 3 μM TSA, 20 and 40 μM Na2-mal, TOFA (5–100 μg/mL), cerulenin (20-400 μM), 10 μM CCCP, 100 μM IBMX, and 10 μM Rp-cAMPS in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 1–4 h. After treatments, the Kmal level, sperm functions, glycolysis, cAMP and ATP levels were examined. During sperm capacitation, there is a progressive increase in PKA activity, reaching maximal phosphorylation levels of its substrates upon completion of capacitation. Consequently, we investigated the impact of Na2-mal and RpcAMPS on the substrate phosphorylation level of PKA in both non-capacitated and capacitated human sperm. The 0.1% DMSO group served as the control or “0” group to mitigate any potential effects of DMSO on sperm functions, given that all chemicals were prepared using DMSO.

Cell culture and transfection

Mouse spermatogonia GC-1 (iCell-m022) were procured from iCell Bioscience Inc. (Shanghai, China). The GC-1 cell line was derived from BALB/c male mice. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (12100; Solarbio Life Sciences, Beijing, China), supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (FS401-02; TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Subculturing was conducted when the cell density reached approximately 80%, specifically selecting cells in the logarithmic growth phase for subsequent experiments. The pCMV-mCherry-P300-Neo plasmid was obtained from WZ Biosciences Inc. (Shandong, China) and transfected into the GC-1 cells using the standard Lipofectamine 2000 protocol. Additionally, SIRT5 siRNA was supplied by GenScript Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). Transfection was performed at a cell density of 60–70%, with SIRT5 siRNA and the transfection reagent added to the culture medium following the supplier’s recommended transfection protocol.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from transfected cells 48 h post-transfection using TRIzol reagent. After quality verification, 1 µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a PrimeScript RT kit with gDNA Eraser. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on a CFX96 system using SYBR Green chemistry. The reactions comprised cDNA, 0.4 µM of each primer, and SYBR Green master mix. The thermal cycling protocol was: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Target gene expression was normalized to Gapdh and calculated via the 2(–ΔΔCt) method. The primers used in the present study include P300 (TTGTGTTTCTTCGGCATGCA and AGGTGGATGGCAATGGAAGA)29 and SIRT5 (ACTCTTCCTGAAGCCCTTGC and TTGGGGCTTGAAGGGTGTTT)30.

Protein extraction and co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP)

Protein lysates were prepared from GC-1 cells and purified sperm cells using RIPA lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche, Germany). After lysis on ice for 2 h, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was measured with a BCA assay kit (Pierce, USA). All samples were normalized to a uniform concentration of 1 μg/μL and stored at −80 °C.

For Co-IP, 500 μg of protein was diluted to 500 μL with ice-cold RIPA buffer. To reduce nonspecific binding, lysates were pre-cleared using 20 μL of Protein A/G Plus Agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) for 1 h at 4 °C. The pre-cleared lysates were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with 2 μg of either phospho-PKA substrate (RRXS*/T*) rabbit antibody or anti-malonyllysine antibody. Rabbit IgG served as the negative control. Subsequently, 40 μL of Protein A/G Plus Agarose beads were added, followed by 4 h of incubation. The beads were pelleted and washed five times with ice-cold RIPA buffer. Bound proteins were eluted in 2× Laemmli sample buffer by heating at 95 °C for 10 min and then subjected to Western blot analysis.

Western blot

Total proteins and protein fractions specific to the sperm head, mitochondria, and cytoplasm were isolated from human sperm samples, and their concentrations were quantified utilizing the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, 30 μg of these proteins was subjected to Western blot analysis, adhering to the protocols detailed in our prior publication13. Antibodies were diluted to precise concentrations to ensure accurate detection: anti-COX6B1 and anti-SIRT5 antibodies at 1:500, anti-PLMs, anti-PMR2, anti-ACC1, anti-FASN, anti-PDK1, anti-PPP1R2, anti-GAPDHS, anti-VDAC3, anti-P300, anti-SIRT5, and phospho-PKA substrate antibodies at 1:1000, anti-ACTIN and secondary antibodies at 1:10000. The specificity of cellular components was validated by Western blot using the corresponding markers: PRM2 for sperm head, COX6B1 for mitochondrion, and ACTIN for cytoplasm. Uncropped blot images are provided in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 19–30). ImageJ software (version 1.44, National Institutes of Health) was used to facilitate band intensity measurement. Target malonylated protein quantification involved normalizing their band intensities against ACTIN signals. The relative Kmal and SIRT5 levels in normozoospermic and asthenozoospermic samples were determined by normalizing to the mean values of the normozoospermic samples.

Gene delivery in animal models

All experiments utilized 6-week-old male C57BL/6J mice. The mice, which were wild-type with no targeted genetic modifications, were purchased from Sikebeisi Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Henan, China). Upon arrival, mice were housed in a barrier facility under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. The housing environment was maintained at 24 ± 1°C with 50–60% humidity and a 12-h light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to standard rodent chow and water.

The health status of the colony was routinely monitored, and surveillance reports indicated the absence of common murine pathogens. All mice underwent a 10-day acclimatization period prior to any procedures. Only healthy animals showing no overt signs of illness or injury were included in the study. Furthermore, any mouse whose body weight at the start of the experiment deviated by more than 20% from the cohort average was excluded. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use and were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Yichun University (Approval Code: 2025-044).

The pAAV-U6-shRNA (Sirt5)-CMV-mScarIet-WPRE (AAV2/8, titer: 1.39 × 1013 v.g./ml), pAAV-CMV-P300-T2A-mScarlet-WPRE (AAV2/8, titer: 1.16 × 1013 v.g./ml) were designed and produced by Obio Technology (Shanghai, China). Based on established methodologies31,32, mice were randomly allocated into experimental and control groups using a random number table, with six mice per treatment condition. The study comprised two independent experiments:

Sirt5 knockdown experiment

Experimental group (n = 3): injected with pAAV-U6-shRNA(Sirt5)-CMV-mScarlet-WPRE (AAV2/8, titer: 1.39 × 1013 viral genomes (v.g.)/mL).

Control group (n = 3): injected with pAAV-U6-CMV-mScarlet-WPRE (AAV2/8, titer: 1.39 × 1013 v.g./mL).

P300 overexpression experiment

Experimental group (n = 3): injected with pAAV-CMV-P300-T2A-mScarlet-WPRE (AAV2/8, titer: 1.16 × 1013 v.g./mL).

Control group (n = 3): injected with pAAV-CMV-T2A-mScarlet-WPRE (AAV2/8, titer: 1.16 × 1013 v.g./mL).

Prior to procedures, each mouse was anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of tribromoethanol (Avertin; 250 mg/kg) prepared as a 1.25% solution. Upon induction of anesthesia, the mouse was secured in a supine position on a surgical platform. The lower abdominal area was shaved, and the testes were gently guided into the scrotum. The scrotal skin was disinfected with 75% ethanol. Using a 10 μL microsyringe, 6 μL of viral solution was accurately injected into the testicular stroma. Following AAV administration, mice were kept under a heating lamp or on a warming pad until fully ambulatory and behaviorally normal, then returned to their home cages. Assessments to evaluate the efficacy of gene knockdown or overexpression were conducted 2 weeks post-injection.

Stringent standardization procedures were implemented to minimize technical and environmental variation. All testicular intra-stromal injections were performed by a single, highly trained researcher at a consistent time to ensure uniformity in surgical technique, injection parameters, and postoperative care. Post-injection, mice from different experimental groups were housed in the same room, with cages from all groups placed in close proximity. This ensured exposure to identical macro-environmental conditions (light cycle, temperature, humidity, and noise).

To minimize observer bias, all subsequent analyses, including sperm collection, computer-assisted sperm motility assessment, and tissue processing for histology (H&E staining), qPCR, Western blot, and immunofluorescence, were performed by an investigator blinded to group allocation (experimental vs. control) throughout data acquisition and initial processing.

As this was an exploratory investigation designed to probe the roles of SIRT5 and P300 in sperm malonylation and function, a formal, detailed experimental protocol was not pre-registered. The procedures and analyses were developed based on this primary objective.

Animal welfare and endpoints

Given that the experimental design culminated in a terminal procedure at a fixed endpoint (8 weeks post-injection for tissue and sperm collection), formal, predefined humane endpoints were not established. All animals were euthanized at this predetermined endpoint prior to the potential development of any sustained discomfort related to the procedures. No adverse events were observed during the study.

Hematoxylin & eosin staining

Testicular tissues were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut to a thickness of 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) utilizing a commercial kit (AR1180-100, Boster Biological Technology, Wuhan, China). Histological analyses were conducted using a Leica DM2500 microscope, with eight random fields assessed per sample.

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis

Immunofluorescence staining was carried out using a method established in our earlier study13,33. The harvested testes were initially fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently frozen in liquid nitrogen before being sectioned into 5 µm thick slices using a Leica CM1950 cryostat. For the purpose of intracellular protein detection, the sections underwent permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min. To prevent non-specific antibody binding, a blocking step was performed using 3% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-P300 antibody (1:100) and anti-SIRT5 antibody (1:100), followed by staining with CoraLite594-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200) and 1 µM DAPI. In parallel, mouse sperm, including normozoospermic and asthenozoospermic samples, as well as sperm subjected to various chemical treatments, were similarly fixed, permeabilized, blocked, and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies (1:200). The dilution factors for the primary antibodies were as follows: anti-Kmal antibody (1:100), anti-COX6B1 antibody (1:50), anti-ACC1 antibody (1:50), anti-FASN antibody (1:50), anti-P300 antibody (1:100) and anti-SIRT5 antibody (1:100). After incubation with the antibodies, the sperm were stained with CoraLite488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200), CoraLite594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200) and 0.5 μM DAPI for 30 min. The stained sperm were visualized using a laser scanning confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a super-resolution structured illumination microscopy (SIM) (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell viability assay

GC-1 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and cultured in DMEM at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 24 h. Then, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution (E-CK-A362; Elabscience, Wuhan, China) was added to each well, followed by incubation in the dark for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Thermo Scientific Multiskan FC microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated as follows:

where Ae represents the absorbance of wells containing cells and the test compound, Ac denotes the absorbance of control wells (cells only), and Ab corresponds to the absorbance of blank wells (medium only).

Analysis of sperm morphology and functions

Sperm viability following Na₂-mal exposure was evaluated using an eosin-nigrosin staining kit (G2581, Solarbio Life Sciences, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each experimental condition, a minimum of 200 spermatozoa were assessed microscopically. Viable spermatozoa remained unstained, whereas non-viable cells were identified by the uptake of eosin, which resulted in distinct red staining of the sperm head. The total motility and progressive motility were evaluated utilizing a 10-µm-deep sperm counting chamber (Laja, Luzernestraat, Netherlands) with an Axio Lab A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany). The analysis was executed by experienced investigators who were unaware of the treatment groups. In each test, at least 200 sperm were analyzed. Sperm penetration ability was carried out by a sperm methylcellulose penetration assay adhering to established methodologies14. Sperm morphology was evaluated utilizing the Diff-Quick staining method (G1540, Solarbio Life Sciences, Beijing, China). Sperm were classified as morphologically abnormal if they exhibited anomalies in the head or tail, or if there was an excess of cytoplasmic residues. For each specimen, a minimum of 200 sperm were examined under a light microscope at a magnification of ×1000. Subsequently, the proportions of viable sperm and those exhibiting normal morphology were calculated.

Detection of sperm physiological and biochemical indexes

Glycolysis was measured by the production of L-Lactate from glycolysis in human sperm using the glycolysis assay kit (KA6207) provided by Abnova Corporation (Taipei, China) according to the assay procedure in the kit. ATP in human sperm was measured using a non-radioactive ATP assay kit (KA1661, Abnova) strictly following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. MMP in human sperm was examined by JC-1 staining34. In brief, purified sperm were incubated with 2 μM JC-1 in a high-salt solution for 20 min at 37 °C under 5% CO2. After staining, cells were washed with high-salt solution to remove unbound dye. Test substances were then introduced, and the samples were incubated for 2 h. Fluorescence readings were acquired on an EnSpire Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Inc.) using excitation/emission settings of 525 nm/590 nm for the red signal (Fred) and 488 nm/530 nm for the green signal (Fgreen). Measurements were taken prior to treatment (baseline) and at 30 min after incubation. Sperm cAMP level was assessed by a cAMP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (581001), which was procured from Caymen Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA), adhering closely to the provided protocols to ensure reliable and reproducible results.

Detection of human sperm [Ca2+]i

Purified human sperm were stained with 5 µM Fluo-4 AM, a fluorescent calcium indicator from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., along with 0.05% pluronic F-127 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at 37 °C for 30 min. After washing, the stained sperm were loaded into a microplate and analyzed using a PerkinElmer EnSpire® Multimode Plate Reader (Waltham, MA, USA)33. Before adding Na2-mal, the fluorescence of the stained sperm was continuously monitored for 1 min to ensure that a stable baseline was established before any chemical intervention. After adding Na2-mal, the fluorescence of the stained sperm was monitored for another 5 min. The time interval is 2 s. The sperm [Ca2+]i were quantified and expressed as a percentage change, indicated as ΔF/F0 (%). This metric was calculated using the formula (F − F0)/F0 × 100%, where F0 represents the average basal fluorescence measured before the application of any chemicals, and F indicates the fluorescence intensity observed at each respective time point during the experiment.

Electrophysiological experiments

Recording of patch-clamp data from human sperm was performed following standard procedures to investigate the monovalent currents associated with CATSPER35. Specifically, recordings were obtained in a divalent-free solution composed of 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EDTA, adjusted to a pH of 7.4. The study focused on assessing the influence of 20 and 40 μM Na2-mal, dissolved in the divalent-free solution, on the resting monovalent CATSPER currents. All patch-clamp data collected during the experiments were thoroughly analyzed using Clampfit version 10.4 software, developed by Axon located in Gilze, Netherlands.

Statistics and reproducibility

GraphPad Prism version 10.1.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was employed to analyze and interpret the data. The data are expressed as means ± standard error of the means (SEM) and were verified to adhere to a normal distribution. An unpaired t-test was employed to compare differences between the groups of normozoospermic and asthenozoospermic men. Simple linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the correlations between sperm Kmal level and progressive motility, sperm Kmal level and sperm SIRT5 level, and sperm Kmal level and sperm ATP level. In addition, differences observed between control samples and those subjected to chemical treatments were analyzed through One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test. Given the limited sample size (n = 3 biologically independent samples per group) in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 17, parametric tests were not used due to insufficient statistical power to reliably assess data distribution assumptions. Non-parametric tests were therefore applied for group comparisons. Specifically, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to evaluate differences between the control and each experimental group for the following outcomes: relative protein levels of P300/β‑actin and SIRT5/β‑actin (Supplementary Fig. 14), as well as sperm concentration, progressive motility, and abnormality rate (Supplementary Fig. 17). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval

Each participant provided their informed consent by signing a consent form, thereby affirming their voluntary involvement in the research. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. Furthermore, the study received ethical approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Yichun University (approval code: 2022-21). This approval permitted the researchers to conduct semen collection and related experiments. All animal experiments were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Yichun University (approval code: 2025-044). This study complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal experimentation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data underlying the graphs and charts are provided in the Supplementary Data. The uncropped images of the western blots can be found in Supplementary Figs. 19–30. All other data are available from the corresponding author (or other sources, as applicable) on reasonable request.

References

Vu, L. D., Gevaert, K. & De Smet, I. Protein language: post-translational modifications talking to each other. Trends Plant Sci. 23, 1068–1080 (2018).

Hao, B. et al. Substrate and functional diversity of protein lysine post-translational modifications. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 22, qzae019 (2024).

Fu, Y., Yu, J., Li, F. & Ge, S. Oncometabolites drive tumorigenesis by enhancing protein acylation: from chromosomal remodelling to nonhistone modification. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 41, 144 (2022).

Zhong, Q. et al. Protein posttranslational modifications in health and diseases: Functions, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. MedComm 4, e261 (2023).

Peng, C. et al. The first identification of lysine malonylation substrates and its regulatory enzyme. Mol. Cell Proteom. 10, M111.012658 (2011).

Colak, G. et al. Proteomic and biochemical studies of lysine malonylation suggest its malonic aciduria-associated regulatory role in mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation. Mol. Cell Proteom. 14, 3056–3071 (2015).

Shen, Z. Q. et al. Characterization of the sperm proteome and reproductive outcomes with in vitro, fertilization after a reduction in male ejaculatory abstinence period. Mol. Cell Proteom. 18, S109–S117 (2019).

Gur, Y. & Breitbart, H. Protein synthesis in sperm: dialog between mitochondria and cytoplasm. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 282, 45–55 (2008).

Wang, Y., Wan, J., Ling, X., Liu, M. & Zhou, T. The human sperm proteome 2.0: an integrated resource for studying sperm functions at the level of posttranslational modification. Proteomics 16, 2597–2601 (2016).

Serrano, R., Garcia-Marin, L. J. & Bragado, M. J. Sperm phosphoproteome: unraveling male infertility. Biology 11, 659 (2022).

Sun, G. et al. Insights into the lysine acetylproteome of human sperm. J. Proteom. 109, 199–211 (2014).

Yu, H. et al. Acetylproteomic analysis reveals functional implications of lysine acetylation in human spermatozoa (sperm). Mol. Cell Proteom. 14, 1009–1023 (2015).

Cheng, Y. M. et al. Lysine glutarylation in human sperm is associated with progressive motility. Hum. Reprod. 34, 1186–1194 (2019).

Cheng, Y. M. et al. Posttranslational lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation of human sperm tail proteins affects motility. Hum. Reprod. 35, 494–503 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. Diet-induced obesity is associated with altered expression of sperm motility-related genes and testicular post-translational modifications in a mouse model. Theriogenology 158, 233–238 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. Global proteomic analyses of lysine acetylation, malonylation, succinylation, and crotonylation in human sperm reveal their involvement in male fertility. J. Proteom. 303, 105213 (2024).

Ford, W. C. Glycolysis and sperm motility: does a spoonful of sugar help the flagellum go round? Hum. Reprod. Update 12, 269–274 (2006).

Li, Y. et al. Lysophosphatidic acid improves human sperm motility by enhancing glycolysis and activating L-type calcium channels. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 896558 (2022).

Skinner, W. M. et al. Mitochondrial uncouplers impair human sperm motility without altering ATP content. Biol. Reprod. 109, 192–203 (2023).

Buffone, M. G., Wertheimer, E. V., Visconti, P. E. & Krapf, D. Central role of soluble adenylyl cyclase and cAMP in sperm physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 2610–2620 (2014).

Finkelstein, M., Etkovitz, N. & Breitbart, H. Ca2+ signaling in mammalian spermatozoa. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 516, 110953 (2020).

Amaral, A. Energy metabolism in mammalian sperm motility. WIREs Mech. Dis. 14, e1569 (2022).

Rosencrans, W. M., Rajendran, M., Bezrukov, S. M. & Rostovtseva, T. K. VDAC regulation of mitochondrial calcium flux: from channel biophysics to disease. Cell Calcium 94, 102356 (2021).

Sampson, M. J. et al. Immotile sperm and infertility in mice lacking mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel type 3. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39206–39212 (2001).

Liu, B. et al. Co-incubation of human spermatozoa with anti-VDAC antibody reduced sperm motility. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 33, 142–150 (2014). Epub 2014 Jan 24.

Hereng, T. H. et al. Exogenous pyruvate accelerates glycolysis and promotes capacitation in human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 26, 3249–3263 (2011).

Hosseini, M. et al. Sperm epigenetics and male infertility: unraveling the molecular puzzle. Hum. Genom. 18, 57 (2024).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G. Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Yang, B. et al. Histone acetyltransferease p300 modulates TIM4 expression in dendritic cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 21336 (2016).

Liu, L. et al. SIRT5 promotes the osteo-inductive potential of BMP9 by stabilizing the HIF-1α protein in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Genes Dis. 12, 101563 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Melatonin receptor 1a alleviates sleep fragmentation-aggravated testicular injury in T2DM by suppression of TAB1/TAK1 complex through FGFR1. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 15, 3591–3610 (2025).

Pang, J. et al. Targeted gene silencing in mouse testicular Sertoli and Leydig cells using adeno-associated virus vectors. Asian J. Androl. 27, 627–637 (2025).

Xu, W. et al. Oral exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics reduced male fertility and even caused male infertility by inducing testicular and sperm toxicities in mice. J. Hazard Mater. 454, 131470 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Occurrence, toxicity and removal of polystyrene microplastics and nanoplastics in human sperm. Environ. Chem. Lett. 22, 2159–2165 (2024).

Zou, Q. X. et al. Diethylstilbestrol activates CatSper and disturbs progesterone actions in human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod. 32, 290–298 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32460183 to T.L.; 82101690 to Y.C.), the Jiangxi Province Major Discipline Academic and Technical Leaders Training Project (20243BCE51171 to Y.C.), the Ganpo Talent Plan (gpyc20250054 to T.L.), the Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20224BAB216029 to Y.C.), the Science Foundation of Jiangxi Provincial Office of Education (GJJ2501612 to Y.C.), and the Science and Technology Plan Project of Yichun (2023ZDJH2699 to Z.P.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M.C., Y.T., and Z.P. performed the Western blot analyses. The immunofluorescence assays were conducted by Y.M.C., Y.T., and Z.P. T.L. and Z.P. executed the super-resolution microscopy. H.Y.C. and S.L.P. were instrumental in the collection and processing of all semen samples. H.Y.C., Y.M.C., Y.T., and Z.P. analyzed sperm functions and examined physiological and biochemical indexes. Y.T. and Y.C. conducted the sperm patch clamp experiment and the animal study. Y.M.C. and Y.C. analyzed sperm [Ca2+]i. T.L. and Y.M.C. supervised the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors contributed substantially to reviewing and editing the manuscript and approved the final version before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Mark A. Baker, Fei Sun and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Frank Avila and Kaliya Georgieva.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, Y., Tian, Y., Chen, H. et al. Lysine malonylation regulates human sperm motility. Commun Biol 9, 178 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-026-09683-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-026-09683-y