Abstract

Two-phase cooling has become a promising method for improving the sustainability and efficiency of high energy-density and power-density devices. Fundamentally, however, two-phase thermal transport is not well understood for local, transient processes, especially at critical to near-critical heat fluxes at the macro, micro, and nano-scales. Here we report spatiotemporal characterization of the single-bubble ebullition cycle in a hot-spot heating configuration with heat fluxes approaching 3 kW cm−2. In particular, we experimentally reconstruct the spatiotemporal heat transfer coefficient in terms of its proportionality at both the macro-scale (l >> 1 μm) and the micro-to-nanoscale (l < 1 μm). We show that the maximum rates of heat transfer occur during the microlayer evaporation stage of the ebullition cycle, corresponding to critical maxima in the heat transfer coefficient of ~160 ± 40 kW m−2 K−1 and ~5300 ± 300 kW m−2 K−1 at the macro-scale and micro-to-nanoscale, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Micro-scale and nano-scale phase change heat transport has become a popular research topic in thermal sciences due to its potential role for actively cooling current and future microelectronics1,2, datacenters3,4, energy harvesting and conversion systems5, and many other technologies exposed to high heat fluxes6. Recently, there has been growing focus on deciphering the relative importance of the different thermo-physical mechanisms that dictate the cooling efficiency of a phase-change boiling and evaporation process at the macro-, micro-, and nano-scale. The process is complex with many interrelated thermo-physical phenomena that occur at varying time- and length-scales. Most commonly, four key, transient mechanisms are attributed to the heat transfer process during the vapor-bubble ebullition cycle7,8,9,10 (or forced convection boiling in general): microlayer evaporation, interline evaporation, transient conduction, and micro-convection—while other mechanisms such as condensation11,12 and liquid imbibition13,14,15,16 can contribute with varying significance at different heat flux conditions.

Despite the concerted effort within the thermal sciences community, there are still significant challenges in deciphering the relative importance of each transport mechanism, especially over multiple length-scales and at high-to-critical heat fluxes10,17,18,19. The vital bottleneck in deciphering their relative importance coincides with the lack of high spatiotemporal diagnostic systems capable of independent temperature, heat flux, and flow-field measurements20,21. For example, during the bubble ebullition cycle, synchronized temperature and flow-field measurements are needed at spatial- and temporal-resolutions of <5 μm and <200 μs, respectively17—i.e., length- and time-scales that can resolve the difference between both (1) microlayer and interline evaporation during bubble growth and (2) micro-convection and transient conduction after bubble release. The temperature and wall heat flux are rarely measured independently. Most commonly, the surface heat flux is estimated based on spatiotemporal temperature measurements10,22,23,24,25 with the assistance of numerical modeling to account for conjugate effects26,27. Moreover, the fluid temperature is typically measured at large distances from the three-phase-interface (e.g., at the inlet and outlet of a microchannel device)18; or alternatively, it is calculated via numerical methods using an estimated surface heat flux21. Contact-based temperature measurements are intrusive and temporally lag the transient boiling dynamics due to their relatively long thermal response times17. Therefore, of particular interest are some of the new, non-contact techniques for surface and fluid temperature characterization25,28,29,30,31,32. However, no single method can measure all the key thermo-fluid parameters. Therefore, all traditional methods suffer from insufficient resolution in at least one spatial, temporal, or temperature-diagnostic.

In this communication, we present the extended application of the time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) technique33 to characterize both the local, transient wall temperature and the local, transient heat transfer coefficient (HTC) during subcooled flow boiling. We focus on the ebullition cycle of a single vapor bubble over a micron-sized hot-spot in a microchannel using two different cooling configurations: (1) subcooled flow boiling and (2) subcooled pool/confined boiling. In both of these subcooled boiling configurations, localized wall-to-fluid heat fluxes beyond 2 kW cm−2 are achieved with in-situ HTC characterization during the consecutive bubble ebullition cycles. In particular, we report the spatiotemporal heat transfer coefficient during the bubble ebullition cycle in terms of its proportionality at both the macro-scale (l ≫ 1 μm) and the micro-to-nanoscale (l < 1 μm). These spatiotemporal HTC studies support that the maximum rates of heat transfer coincide with the microlayer evaporation stage of the ebullition cycle, where we observe upper-limit macroscale and micro-to-nanoscale HTCs of ~160 ± 40 kW m−2 K−1 and ~5300 ± 300 kW m−2 K−1, respectively. Although the micro-to-nanoscale HTCs are seeming large, the macroscale HTCs coincide with those that are commonly reported during two-phase flow at significantly smaller heat fluxes. In light of the extreme local heat fluxes imposed in this work, our reproduction of commonly measured macroscale HTCs offers promise for the adept use of conventional HTC correlations in extreme thermal gradient processes.

Results

TDTR experiments for subcooled boiling in microchannels

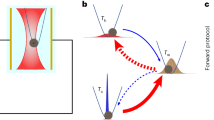

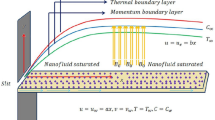

Figure 1a–e illustrates the different heat and mass transport processes during the vapor bubble ebullition cycle. These transient processes are depicted in a hot-spot heating configuration to emphasize the local heating by the TDTR pump-probe lasers. The TDTR method provides in-situ HTC characterization during the bubble ebullition cycle33. Figure 2 illustrates the experimental configuration for combining TDTR with local subcooled boiling in a microchannel. The acrylic substrate is optically transparent to allow both high-speed imaging of the flow-field and positioning and alignment of the pump-probe lasers in the microchannel (Fig. 2a, b). The microchannel assembly serves as the central sample stage for the coolant flow loop and TDTR optical setup (Supplementary Fig. 1). Detailed descriptions of the TDTR technique for in-situ HTC characterization are provided in refs.33,34 for both single-phase microchannel cooling and microdroplet evaporation, respectively. The TDTR pump and probe beams are concentrically focused on a metal thin-film transducer in thermal contact with the material of interest35,36,37,38,39,40. We use the in-phase to out-of-phase voltage ratio (|Vin/Vout|) as the key measurement parameter for characterizing the thermal transport properties of the materials in contact with the metal thin-film. The unique experimental aspect of this work is that measurements of |Vin/Vout| are used to extract the local, transient HTC of flowing, boiling, and stagnant fluids, where the transient changes in |Vin/Vout| (e.g., due to boiling events) are recorded with a high-speed oscilloscope connected to the channel outputs of the lock-in amplifier (Fig. 2c).

Transient processes during bubble ebullition on a hot-spot. a Microlayer evaporation during bubble growth; b Quenching with transient conduction during onset of release; c Wake flow with transient conduction during release; d Bubble mixing with transient conduction and turbulent micro-convection during post release; e Microlayer evaporation with liquid imbibition (wicking) and condensation during bubble regrowth

Experimental Setup. a Schematic representation of TDTR (pump-probe) HTC characterization of two-phase cooling in a PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane)-patterned microchannel between an Acrylic substrate and a 70 nm Hf80 alloy transducer deposited on a fused silica (FS) window. Distilled, degassed water at 22 °C flows through the microchannel with the flow rate controlled via a syringe pump flow loop; b Cross-sectional view of single bubble growth in a microchannel with cross-flow and in-situ TDTR. The frequency-modulated pump beam at ≈976 kHz induces a temporal heat flux in the three-layers stack (FS window, Hf80 transducer, and subcooled water), where at large heat fluxes (or wall superheats) single bubble nucleation, growth, and release occurs; c Schematic representation of the TDTR measurement principle for transient HTC characterization. The photodetector records the temporal thermoreflectance signal of the probe beam (which is a modulated pulse-train of ≈140 fs in width laser pulses). Then, lock-in amplifier measurement techniques (coupled with oscilloscope recordings) facilitate transient HTC characterization (via the Vin/Vout TDTR voltage ratio) at the three-phase interfacial region between the Hf80 hot-spot and liquid/bubble interface

Local, single-bubble boiling data with subcooled water

Boiling heat transfer curves which correlate the wall-to-fluid heat flux to the wall superheat are traditionally used to explain different boiling heat transfer regimes41. They also facilitate predictions of overall HTC, critical heat flux (CHF), and limits for device burnout42,43,44. Internal two-phase flows inside microchannels also highlight the importance of different boiling regimes, depending on the heat flux, relative size of bubbles (compared to the channel dimensions), mass flux, and the vapor quality of the flow. Commonly, boiling curves for internal two-phase flows are correlated to maps of the different flow and heat transfer regimes (e.g., starting from the subcooled boiling region and then transition to developing bubbly, slug, annular, and mist flows for continuous heat loads). Understanding the connection (and/or mechanisms for transition) between the different flow boiling regimes is incredibly challenging. This challenge is due to not only experimental limitations, but also due to the non-linear dependence between the wall heat flux and phenomenon including (but not limited to) changes in the nucleation site density, hydrodynamic instabilities, the existence (and/or thickness) of liquid macrolayers, vapor recoil, liquid imbibition, and bubble mixing. In this regard, we have conducted single bubble boiling experiments on a smooth microchannel wall to (1) minimize the significance of bubble mixing and liquid imbibition25 and (2) maximize the significance of transient conduction and microlayer evaporation within the vicinity of the micro-regions and macro-regions of the vapor bubble45.

Figure 3 provides raw TDTR data measured as a function of laser heating power (i.e., heat flux) for both subcooled stagnant water (open circles) and subcooled flowing water (filled circles) in the microchannel. These experiments correspond to the average, steady-state thermal transport behavior recorded over several minutes and a hot-spot area of ≈200 μm2. The measured lock-in voltage data are plotted as a function of the total laser heating power, where the incident probe power on the sample was fixed at ≈3 mW and the incident pump power on the sample was varied from ≈7.5 mW to ≈37.5 mW in increments of ≈ 3.75 mW. The reflectivity of Hf80 is 60%; so, only 40% of this incident laser power is absorbed by Hf80, and thus, as indicated in Fig. 3, the laser power associated with heating ranges from 4.2 mW ≲ \(\widetilde {{P}}\) ≲ 16.2 mW. Due to the small focused beam waists of the pump (wpump≈9.5 µm) and probe (wprobe ≈ 7.5 µm), we are able to achieve relatively large hot-spot heat fluxes from the Hf80 alloy—e.g., 1.5 kW cm−2 \(\lesssim \hskip 2pt {q''_{\mathrm{net}}} \lesssim\) 5.7 kW cm−2, where \(q''_{\mathrm{net}} = {\tilde{P}}{\mathrm{/}}{{\pi }}\overline {{w}} ^2\) and\(\overline w\) is the laser power weighted 1/e2 radius of the hot-spot. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the hot-spot heat flux from the Hf80 alloy is distributed into both the fluid (f) and the fused silica (FS) substrate—e.g.,

where

are the heat fluxes into the fluid and FS (respectively) and \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) is the effective thermal conductivity of the fluid coolant. For the studies presented in the manuscript, the effective thermal conductivity of the “molecular-water” coolant ranges from values as large as ~ 1.67 W m−1 K−1 (e.g., during nucleate flow boiling) to values as small as ~0.06 W m−1 K−1 (e.g., during wall-dryout at Twall ≳ 220 °C). The effective thermal conductivity of the fluid coolant (f) can be expressed as: \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}} = k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{bulk}}} + k_ \uparrow\), where \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{bulk}}}\) is the bulk thermal conductivity of the fluid coolant and k↑ represents a local enhancement. We note that \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{bulk}}}\) can be simply calculated via effective medium theory for any mixture. However, calculation of k↑ is not as straightforward because this “conductive enhancement” can be either a positive [+] or negative [−] quantity—due to phase-change (boiling [+], condensation [−]), chemical reactions (endothermic [+], exothermic [−]), and sensible heating [−] or cooling [+] coupled to the thermophysical properties of the flow-field.

TDTR data for steady-state subcooled boiling experiments. Lock-in amplifier measurements of a In-phase, Vin; b Out-of-phase, Vout; and c ratio, |Vin/Vout| signal at different TDTR laser heating powers (\(\widetilde P\)) and a constant pump-probe time delay of 100 ps. The different symbols correspond to experiments with either subcooled stagnant water (◯) or subcooled flowing water (●) in the microchannel, where Dh ≈ 480 μm, Re D ≈ 0 (◯), Re D ≈ 1850 (●), fmod = 976 kHz, and τd = 100 ps. All data reported as mean±standard deviation via repeated measurements at a prescribed laser heating power

For the data in Fig. 3 at low laser heating powers (i.e., \(\widetilde P\) ≲ 6 mW—corresponding to \(q''_{\mathrm{f}} \lesssim\)0.74 kW cm−2 and \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}} \lesssim\)1.62 kW cm−2), the fluid remains single-phase over the hot-spot for both flowing and stagnant subcooled water in the microchannel. For these lower-limit laser heating conditions, there is a relatively small difference between the TDTR in-phase (Fig. 3a), out-of-phase (Fig. 3b), and ratio (Fig. 3c) signals for the flowing and stagnant water experiments. However, at laser heating powers ≳7 mW (\(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\) ≳ 0.87 kW cm−2, \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}}\) ≳ 1.88 kW cm−2), vapor bubbles start to nucleate in the microchannel—coinciding with a significant contrast between these TDTR signals with increasing laser heating power.

Figure 4 provides a time series of images of the hot-spot region in the center of the microchannel with \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7 mW. These images (Fig. 4a–e) are for a transient subcooled flow boiling experiment, where both subcooled stagnant water and subcooled flow boiling conditions are utilized (Supplementary Movie 1). Typically, for a subcooled flow boiling experiment with a laser heating power of \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 ± 0.5 mW, a vapor bubble does not nucleate unless there is an interruption in flow. This is because this heating power (\(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 ± 0.5 mW) coincides with hot-spot surface heating within a few degrees of the corresponding wall temperature for the onset of nucleate boiling (ONB)46. Thus, an interruption or stoppage can induce rapid increase in the average hot-spot/wall temperature (THS) to a value just beyond that required for bubble nucleation (\(T_{{\mathrm{HS}}} > T_{\mathrm{w}}^{{\mathrm{ONB}}}\)). This is a unique laser heating condition and a bubble may nucleate during subcooled cross-flow. In this case, the vapor bubble it will either detach from the hot-spot or vibrate without release from the hot-spot. However, when the fluid is stagnant fluid in microchannel at \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 ± 0.5 mW, a vapor bubble will immediately nucleate and grow to a steady-state volume (without release), sustaining a balanced evaporation–condensation mode of heat transfer (as illustrated in Figs. 1e and 4a). For the larger laser heating conditions, \(\widetilde P\) ≳ 10 mW (\(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\) ≳ 1.24 kW cm−2, \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}}\) ≳ 2.69 kW cm−2), nucleate subcooled boiling commences in the microchannel for both the stagnant water and flowing water conditions. As shown in Fig. 3 for \(\widetilde P\) ≳ 10 mW, significant departures in the TDTR signals are observed between the subcooled flow boiling data (filled-circles) and the stagnant water data (open-circles). The largest difference is associated with the out-of-phase TDTR voltage signal (Fig. 3b), supporting that the in-phase (Vin) and out-of-phase (Vout) signals correlate well with changes in the sensible and latent heat transfer modes, respectively.

Vapor bubble nucleation, growth, and release in a microchannel. a Stagnant subcooled water (i.e., \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≅ 0 m s−1), where a vapor bubble grows to a steady-state volume over the TDTR induced hot-spot in the microchannel; b Camera image taken t = 1.36 s after steady flow was induced in the microchannel, where the vapor bubble is vibrating (prior to release) in the subcooled cross-flow (flow: left-to-right with \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≅ 3.5 m s−1); c Camera image taken after vapor bubble release from the hot-spot in cross-flow; d Image after nucleation of a new vapor bubble over the hot-spot in cross-flow; e Image of this second vapor bubble (vibrating) just prior to release from the hot-spot in cross-flow. a–e White scale bar=100 μm. Time stamp: elapsed time after subcooled flow was introduced in the microchannel. Laser heating power: \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW. While the laser heating power is constant, the hot-spot wall temperature and wall heat flux are highly transient during the bubble ebullition cycle. For example, in d with \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW corresponds to THS ≈ 122 °C and \(q''_{\mathrm{f}} \approx\)0.9 kW cm−2 and \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}} \approx\)2.0 kW cm−2 for the average hot-spot Hf80 (wall) temperature and hot-spot heat fluxes into the fluid and FS substrate, respectively. Whereas, in e with \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW, THS ≈ 141 °C, \(q''_{\mathrm{f}} \approx\)0.6 kW cm−2 and \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}} \approx\)2.3 kW cm−2. b–e Dotted-line circle: representative location of the steady-state bubble in image a

For the stagnant water experiments, it is important to point out that the water is both fully “stagnant” and “subcooled” at large distances from the laser induced hot-spot (i.e., at the microchannel inlet and outlet). However, while subcooled nucleate boiling can still occur over the hot-spot at high heat fluxes with a stagnant fluid, it is more appropriate to refer to these stagnant water experiments at large heat fluxes as subcooled confined boiling. Therefore, throughout the remainder of this communication, the expression “stagnant water” will correspond to single-phase, natural convection heat transfer in the microchannel and the expression “confined boiling” will correspond to two-phase boiling heat transfer in the microchannel in the absence of externally-driven fluid flow.

To reconstruct subcooled boiling heat transfer curves from the measured TDTR ratio data in Fig. 3, we implement a TDTR data analysis scheme that is analogous to that used previously33,34. The commonality with the analysis approach relative to previous work33,34 is that a bidirectional TDTR heat transport model is used to fit the effective thermal conductivity of the fluid (\(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\)) to the measured Vin/Vout ratio data at each laser heating power (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). The new caveat in our analysis approach for this communication is that an iterative fitting procedure is used to minimize the number of fitting parameters at each laser heating condition (Supplementary Note 2). The key result is that \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) becomes the only fitting parameter in the iterative process because all other thermal transport properties can be interpolated from literature data using the hot-spot wall temperature as the reference temperature for interpolation. For example, after each fitting iteration, the volumetric heat capacity of the fluid (\(C_p^{\mathrm{f}}\)) and the thermal conductivity and volumetric heat capacity of the substrate (\(C_p^{{\mathrm{FS}}}\), kFS, respectively) are updated in accordance with literature values41 at a calculated hot-spot wall temperature. This iterative approach facilitates a convergence in the calculated hot-spot temperature (Supplementary Fig. 3). To calculate the average hot-spot (wall) temperature we use the low-frequency limit TDTR model solution for the DC temperature rise of the metal transducer35:

where \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) is effective thermal conductivity of the fluid, kFS is the thermal conductivity of the FS substrate at THS, and T∞ = Tbulk = 22 °C is the ambient temperature. Usually three (3) fitting iterations are required for convergence of THS to within 5 °C. This iterative fitting procedure also facilitates calculation of the wall heat flux for each corresponding laser heating power (equations (1–3)).

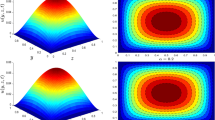

Figure 5 provides the results of this iterative TDTR analysis for the Vin/Vout ratio data in Fig. 3c. The results are disseminated in terms of the thermal effusivity of the fluid (\(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{\mathrm{f}} = (k_{\mathrm{f}}C_p^{\mathrm{f}})^{1{\mathrm{/}}2}\)) and FS substrate (\(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{FS}}} = (k_{{\mathrm{FS}}}C_p^{{\mathrm{FS}}})^{1{\mathrm{/}}2}\)). Figure 5a, b are plotted with respect to the laser heating power (\(\widetilde P\)) and hot-spot wall temperature (THS), respectively. The thermal effusivity is the key focus because both the magnitude of |Vin/Vout| at a given pump-probe delay (τd) and the cooling rate of the metal transducer (e.g., \(\frac{\partial }{{\partial \tau _{\mathrm{d}}}}\left| {V_{{\mathrm{in}}}{\mathrm{/}}V_{{\mathrm{out}}}} \right|\)) are dictated by the thermal effusivity of its surroundings. Moreover, a key focus is placed on the thermal effusivity because measurements of it (via |Vin/Vout| ratio analysis) using the TDTR method facilitates subsequent calculation of the local, transient heat transfer coefficient33,34:

where ω = 2πfmod is the heating (modulation) frequency of the TDTR pump laser (Supplementary Notes 3 and 4). The spatial (local) length-scales of the HTC measurement are dictated by both the size of the hot-spot (e.g., 2\(\overline w\)) and the thermal penetration depth (\(l_{{\mathrm{th}}} = \sqrt {2k{\mathrm{/}}\omega {\it{C}}_p}\)). Whereas, the temporal (transient) timescale of the HTC measurement is dictated by the temporal measurement resolution of |Vin/Vout| (or, indirectly, eth). For comparative analysis The following subsections of this communication describe the analysis of the HTC for both (i) steady-state subcooled boiling and (ii) transient bubble ebullition (boiling) in subcooled cross-flow.

Thermal effusivity measured with TDTR. Thermal effusivity data plotted as a function of a the pump-probe laser heating power; b the calculated average wall temperature of the hot-spot (via iterative TDTR model fits to the Vin/Vout data). Thermal effusivity data are provided for both the FS substrate (\(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{FS}}}\)) and the water coolant (\(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{\mathrm{f}}\)). The open and closed-symbols correspond to experiments with either stagnant or flowing water in the microchannel, where Dh ≈ 480 μm, Re

D

≈ 0 (◯, ), Re

D

≈ 1850 (●,

), Re

D

≈ 1850 (●, ), fmod = 976 kHz, and τd = 100 ps. All data reported as mean±standard deviation

), fmod = 976 kHz, and τd = 100 ps. All data reported as mean±standard deviation

Figure 6 is a reconstruction of the boiling curve for the subcooled flow boiling and stagnant-to-confined boiling experiments. Both the wall heat flux (equation (2)) and hot-spot wall temperature (equation (4)) were calculated using the measured effective thermal conductivity of the fluid and thermal conductivity FS substrate. The boiling curve data in Fig. 6 suggests that CHF is reached at THS ≈ 200 ± 30 °C for subcooled confined boiling, whereas CHF is reached at THS ≈ 220 ± 10 °C—i.e., a comparable wall temperature—for subcooled flow boiling in the microchannel (Supplementary Note 5). These hot-spot wall temperatures match well with that expected based on the Leidenfrost effect with water47,48. It is also noted that the subcooled flow boiling data reveals a negative slope at the onset of nucleate subcooled boiling.

Subcooled boiling curve. Boiling curve reconstructed from the calculated wall-to-fluid hot-spot heat flux (equation (2)) and hot-spot wall temperature (equation (5)). The size (2\(\overline w\)) and net heat flux (\(q''_{{\mathrm{net}}}\)) from the hot-spot are dictated by the power and focused beam waists of TDTR pump-probe lasers, whereas, the hot-spot heat flux into the fluid (\(q_{\mathrm{f}}^\prime\prime\)) and the average hot-spot wall temperature (THS) are dictated by the local HTC at the fluid–wall interface. The filled-symbols and open-symbols correspond to experiments with flowing water and stagnant (or confined) water in a microchannel, respectively, where 2\(\overline w\) ≈ 18 μm, \(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty \approx\)22 °C, Dh≈480 μm, Re D ≈0 (◯), Re D ≈ 1850 (●), fmod = 976 kHz, and τd = 100 ps. All data reported as mean±standard deviation using the fitted thermal effusivity and hot-spot temperature data

Macro-scale and micro-scale heat transfer coefficients

Figure 7 provides the heat transfer coefficients (HTCs) measured as a function of the hot-spot temperature. The HTC data is provided with respect to two different length-scales. Figure 7a provides hω→0 the low-frequency-limit (or large length-scale) HTC, whereas Fig. 7b provides h ω the high-frequency (short length-scale) HTC. For example, the HTC measured in the low-frequency-limit (hω→0) corresponds to that associated with heat and mass transfer at the “macroscale”: hω→0 = \(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\)/ΔTHS, where \(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\) is the wall-to-fluid heat flux and ΔTHS = THS-\(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty\) is hot-spot temperature rise (see, Fig. 6). Whereas high-frequency HTC (h ω ) corresponds to a local heat transfer coefficient measured at the micro-to-nanoscale: h ω = \(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\sqrt \omega\), where ω = 2πfmod, fmod is TDTR laser heating frequency (~ 1 MHz), and \(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) is the effective thermal effusivity measured in a two-phase flow experiment (see, Fig. 5). The inset plots in Fig. 7 shows the local HTC enhancement (h↑), where h = h0 + h↑, h0 represents the local HTC at low heating powers (\(\widetilde P\) ≲ 6 mW) due to conductive heat transport from the hot-spot into a single-phase (stagnant) fluid, and h↑ is a positive or negative enhancement due to a variety of potential mechanisms that include advection, transient conduction, microlayer-to-interline evaporation, nucleate flow-to-film boiling, and vapor-layer formation coupled to wall-dryout and CHF. While the high-frequency HTCs measured by TDTR are quite large—e.g., h ω ≫ 1000 kW m−2 K−1, the corresponding low-frequency-limit HTCs are very well aligned with that reported by others—e.g., hω→0 ≈ 106 ±40 kW m−2 K−1 (see, Table 1 in ref. 33). Because the magnitude of h ω scales as \(\sqrt \omega\) TDTR studies at moderate heating frequencies (e.g., fmod ≲ 1 kHz) would effectively yield h ω data comparable to that typically observed with water in subcooled flow boiling (h ≈ 150 ± 50 kW m−2 K−1). In this regard, we note that 1 kHz is a typical upper-limit frequency (sampling rate) for measuring the wall temperature with IR, thermocouple, or thermistor-based thermometry methods. More detailed studies of this scaling principle based on application of the frequency-domain counterpart of TDTR (i.e., FDTR) is adjourned for a future work due to experimental challenges with TDTR at low heating frequencies. Nevertheless, these HTC results (coupled with the former remarks on scaling-limits) are provided to emphasize that the TDTR method—combined with low-frequency-limit calculations of the hot-spot wall temperature (equation (4)) and wall-to-fluid heat flux (equation (2))—facilitate previously unrealized measurements of both the macroscale HTCs (hω→0, Fig. 7a) and micro-to-nanoscale HTCs (h ω , Fig. 7b). In regards to the latter, h ω is measured over a thin, micro-to-nanoscale interfacial region which is dictated (for solid–liquid systems) by heat transport within the thermal boundary layer (TBL), where the measurement length-scales are defined by both (1) the surface area of the hot-spot (2\(\overline w\) ≈ 18.5 ± 0.5 μm) and (2) the depth (or thickness) of fluid measurement region commonly referred to as the thermal penetration depth (\(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\)). In this study, the thermal penetration depth ranges from thicknesses as thin as \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}|_{\mathrm{f}} \approx\) 250±50 nm (for single and two-phase cooling, before dryout, THS ≲ 180 °C) to thickness as large as \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}|_{\mathrm{g}} \approx\) 1–2 μm (for post-CHF cooling, after dryout, THS ≳ 200 °C).

HTCs for subcooled boiling in a microchannel. a Macroscale heat transfer coefficients (HTCs) resolved using the low-frequency-limit boiling curve data; b Micro-to-nanoscale HTCs measured by TDTR using equation (5) and measured thermal effusivity of the fluid. The inset plots provide the relative enhancement (h↑) in the HTC due forced convection, boiling, and vapor-layer formation (Re

D

≈0 (◯), Re

D

≈1850 ( ), \(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty \approx\)22 °C, Dh≈480 μm). All data reported as mean±standard deviation using the fitted thermal effusivity and hot-spot temperature data

), \(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty \approx\)22 °C, Dh≈480 μm). All data reported as mean±standard deviation using the fitted thermal effusivity and hot-spot temperature data

The iterative fitting procedure indirectly accounts for parasitic heat losses in the FS substrate, facilitating the conception of Figs. 6 and 7a. Although lateral conduction of heat in the Hf80 metal, fluid, and substrate are seemingly neglected, the TDTR hot-spot (2\(\overline w\)) is much larger than the thermal penetration depth (\(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\)) so the temperature gradient is mainly one-dimensional (1D) in the through-plane directions49. This also allows the natural and forced convection above the hot-spot (at a depth greater than \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\)) to conceptualized experimentally as a spatiotemporal boundary condition—i.e., all the 3D heat and mass transfer outside the TDTR hot-spot (>2\(\overline w\): laterally, \(> \ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\), vertically) is seen by TDTR as a 1D thermal effusivity enhancement.

Transient, local HTC predictions during bubble ebullition

To compliment the previous steady-state microchannel boiling experiments, transient flow boiling experiments were conducted. Figure 8 provides the results of a spatiotemporal TDTR experiment for vapor-bubble ebullition in subcooled cross-flow. These local, transient TDTR experiments were synchronized with visible camera videography of the bubble ebullition cycle (Supplementary Movie 1). In this study, the timescale for bubble ebullition are initially rather slow due to the subcooled conditions and applied heat fluxes for the onset of vapor bubble nucleation (e.g., several seconds for bubble ebullition in comparison to 1–200 ms during saturated boiling). For reference, bubble nucleation, growth, and departure can range from <0.522 to 50 ms25 or even longer than 1 s depending on boiling conditions and configuration.

Transient TDTR voltage, HTC, and wall superheat data. a In-phase and; b Out-of-phase components of the transient TDTR voltage signal recorded during subcooled flow boiling of water in a microchannel; c Corresponding TDTR voltage ratio, where the time-stamped vertical lines signify the time of the selected image from the recorded video. White scale bar=100 μm. Time-stamp: elapsed time after subcooled flow was initiated. Red-dot: embedded overlay representing the size and location of the hot-spot. d Transient micro-to-nanoscale HTC based on fitting the transient TDTR ratio data in c to the predictions of the TDTR thermal transport model. The horizontal line predictions correspond to HTC expected using equation (5) with the thermal conductivity of that of subcooled water at 100 °C ( , \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}}\)), subcooled water at 20 °C (

, \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}}\)), subcooled water at 20 °C ( , \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{20{\mathrm{C}}}\)), and saturated water at 1 bar (

, \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{20{\mathrm{C}}}\)), and saturated water at 1 bar ( , \(h_0^{{\mathrm{sat}}.{\mathrm{w}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}}\)); e Corresponding wall superheat during the subcooled flow boiling experiment. The upper and lower plots in e are based on the low-frequency limit solution of the hot-spot (wall) temperature (equation (4)). Upper-plot, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\mathrm{w}}|_{2r^{\ast}}\) is the wall superheat averaged over the central region of the hot-spot (2r*, twice the nuclei (embryo) radius, r* ≈ 765 nm). Lower-plot, ΔTw|2\(\overline w\) is the wall superheat averaged over the 1/e2 diameter of the focused heating lasers (2\(\overline w\)). The line prediction (

, \(h_0^{{\mathrm{sat}}.{\mathrm{w}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}}\)); e Corresponding wall superheat during the subcooled flow boiling experiment. The upper and lower plots in e are based on the low-frequency limit solution of the hot-spot (wall) temperature (equation (4)). Upper-plot, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\mathrm{w}}|_{2r^{\ast}}\) is the wall superheat averaged over the central region of the hot-spot (2r*, twice the nuclei (embryo) radius, r* ≈ 765 nm). Lower-plot, ΔTw|2\(\overline w\) is the wall superheat averaged over the 1/e2 diameter of the focused heating lasers (2\(\overline w\)). The line prediction ( ) corresponds to the wall superheat expected at incipience46, ΔTw,ONB ≈ 43 °C. Experimental details: \(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty \approx\)22 °C; Dh ≈ 480 μm; 2\(\overline w\) ≈ 19 μm; \(\widetilde P\)pump ≈ 5.4 mW; \(\widetilde P\)probe ≈ 1.6 mW; fmod = 976 kHz; τd = 80 ps; t < 0 s (Re

D

≈ 0, \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 0 m s−1); 0≲t≲6 s (Re

D

≈ 1850, \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 3.5 m s−1); and t ≳ 6 s (Re

D

≈ 2050, \(\overline {\nu} _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 3.9 m s−1)

) corresponds to the wall superheat expected at incipience46, ΔTw,ONB ≈ 43 °C. Experimental details: \(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty \approx\)22 °C; Dh ≈ 480 μm; 2\(\overline w\) ≈ 19 μm; \(\widetilde P\)pump ≈ 5.4 mW; \(\widetilde P\)probe ≈ 1.6 mW; fmod = 976 kHz; τd = 80 ps; t < 0 s (Re

D

≈ 0, \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 0 m s−1); 0≲t≲6 s (Re

D

≈ 1850, \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 3.5 m s−1); and t ≳ 6 s (Re

D

≈ 2050, \(\overline {\nu} _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 3.9 m s−1)

For this local, transient flow boiling experiment, the specific laser heating power of \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW was chosen because it coincides with an incipient hot-spot heating power to initiate subcooled bubble nucleation with both stagnant and flowing water. This heating power is also unique because further increases in laser heating power (heat flux) will induce dramatic changes in the bubble dynamics (especially with comparison between flow boiling and stagnant/confined boiling conditions). For example, with \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW and stagnant water in the microchannel (i.e., no subcooled cross-flow), the bubble grows to size less than roughly one fourth the microchannel height; so, there is no direct bubble size confinement effects due to upper wall interactions. However, for larger laser heating powers (e.g., \(\widetilde P\) ≳ 10 mW), the apex of the vapor bubble starts to interact with the upper wall of the microchannel.

As shown in Fig. 8a, the in-phase part of the lock-in voltage signal (Vin) remains relatively constant throughout the bubble ebullition experiment with subcooled cross-flow. However, the out-of-phase voltage signal (Vout) in Fig. 8b experiences spike (or dip in magnitude) after each bubble release event, which subsequently results in a pulsed-like increase in the magnitude of the TDTR ratio (Fig. 8c). Snapshot images are provided to emphasize that the observed maxima in |Vin/Vout| coincides within a time period that coexists between the time of vapor bubble release and the growth of a new vapor bubble. Hence, the maximum rates of heat transfer are observed predominately during the period of microlayer evaporation—given that the vapor-bubble has a triple-line diameter less than the 1/e2 diameter of the hot-spot (DVB ≲ 2\(\overline w\)). If the vapor bubble grows to size larger than 2\(\overline w\), then the TDTR method is effectively interrogating the center, dry spot of the vapor bubble—therefore, there is an observed decrease in the TDTR ratio. The corresponding images in Fig. 8 also illustrate the significant decrease in thermal energy exchange (i.e., eth∝|Vin/Vout|) between the vapor/coolant and the heated hot-spot (red-overlay) when DVB ≳ 2\(\overline w\).

Figure 8d provides the predicted/measured transient HTC during bubble ebullition—via equation (5) combined with iterative fits of \(e_{{\mathrm{th}}}^{\mathrm{f}}\) to the transient |Vin/Vout| data in Fig. 8c. Figure 8e shows the corresponding wall superheat (ΔTw) based on Tsat. = 100 °C and the hot-spot (wall) temperature calculated using equation (4). For comparison, superheat data is provided based on averaging over two different areas: (1) an area corresponding to the average laser heating beam waist and (2) an area corresponding to the nuclei embryo radius (Supplementary Note 6, Supplementary Fig. 4). We point out that the first two peaks in the temporal HTC data (at t≅1.9 and 4.3 s) correspond to large bubble release (DVB ≫ 2\(\overline w\)) then nucleation and slow growth (>1 s) over the hot-spot in cross-flow. However, the plateau region (at t ≳ 6.7 s) corresponds to rapid (<10 ms), small bubble (DVB ≪ 2\(\overline w\)) boiling events (or thin-film boiling) over the hot-spot. This transition from several second (timescale) bubble ebullition to millisecond (timescale) bubble ebullition is coupled an experimentally imposed increase in the water flow rate in the microchannel. For example, in this transient flow boiling experiment the flow rate was increased at t ≈ 6 seconds from \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 3.5 m s−1 (Re D ≈ 1850) to \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\) ≈ 3.9 m s−1 (Re D ≈ 2050).

The shaded (overlay) regions of the HTC data in Fig. 8d are provided to emphasize that heat transfer in this region is predominately due to microlayer evaporation. For example, at HTCs beyond ≈ 4100 kW m−2 K−1 the size of the vapor bubbles are comparable to (or less than) the 1/e2 diameter of the hot-spot (DVB \(\underline \le\) 2\(\overline w\)). The horizontal lines in Fig. 8d are the predicted HTC due to purely thermal conduction in a stagnant fluid (i.e., h = h0). The dash-dot-dot ( ) and dash-dot (

) and dash-dot ( ) lines are for hot-spot cooling via heat conduction with subcooled water (at 20 °C and 100 °C, respectively), whereas the lower dash-dash (

) lines are for hot-spot cooling via heat conduction with subcooled water (at 20 °C and 100 °C, respectively), whereas the lower dash-dash ( ) line is for cooling via conduction with saturated water41. Close inspection of this transient HTC data reveals a potential change in the slope of the transient HTC data at these corresponding stagnant fluid predictions for subcooled water (\(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{20{\mathrm{C}}}\), \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}}\)). The video footage of this subcooled flow boiling experiment also reveals that vapor bubble nucleation only occurs after the transient HTC surpasses the predicted (upper-limit) stagnant fluid HTC for subcooled water at 100 °C (\(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}} \approx\)4100 kW m−2 K−1). The timescale for transient conduction after bubble release is on the order of τ

k

≈ 90 ms, which correlates to a sensible wall heat flux of \(q''_{{\mathrm{sens}}} \approx\)525 W cm−2—i.e., a value comparable to that predicted/measured previously in the steady-state flow boiling experiments (see, Fig. 6 at THS ≈ 100 °C).

) line is for cooling via conduction with saturated water41. Close inspection of this transient HTC data reveals a potential change in the slope of the transient HTC data at these corresponding stagnant fluid predictions for subcooled water (\(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{20{\mathrm{C}}}\), \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}}\)). The video footage of this subcooled flow boiling experiment also reveals that vapor bubble nucleation only occurs after the transient HTC surpasses the predicted (upper-limit) stagnant fluid HTC for subcooled water at 100 °C (\(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}|_{100{\mathrm{C}}} \approx\)4100 kW m−2 K−1). The timescale for transient conduction after bubble release is on the order of τ

k

≈ 90 ms, which correlates to a sensible wall heat flux of \(q''_{{\mathrm{sens}}} \approx\)525 W cm−2—i.e., a value comparable to that predicted/measured previously in the steady-state flow boiling experiments (see, Fig. 6 at THS ≈ 100 °C).

Discussion

Figure 9 summarizes the results from the transient subcooled flow boiling studies in terms of the all the key parameters measured in the experiment. These results are also compared to the recent spatiotemporal HTC studies in ref. 10 in terms of the ratio between the two-phase (h) and single-phase (h0) HTC within a bubble ebullition cycle (Supplementary Note 7, Supplementary Fig. 5). A key result of our hot-spot cooling study is that both the transient micro-to-nanoscale HTC (h ω ) and transient macroscale HTC (hω→0) are simultaneously measured (Fig. 9a). Moreover, similar to the steady-state flow boiling experiments (Figs. 6 and 7), the transient experiments yield macro-scale HTCs (hω→0) that are equivalent to that commonly measured by others in studies of subcooled flow boiling in microchannels. This is an important result, not only because most flow boiling studies in the literature are based on significantly larger heat sources, but also because simultaneous measurement of both hω→0 and h ω support that there is not an experimental chasm between (1) traditional micro-scale to macro-scale two-phase cooling studies and (2) nano-scale thermal transport studies using high-frequency (≫1 kHz) or small length-scale (<1 μm) characterization techniques such as TDTR.

Overview of transient vapor bubble ebullition data for subcooled cross-flow in a microchannel. a Transient micro-to-nanoscale HTC (h ω , left axis) and transient macroscale HTC (hω→0, right axis) during bubble ebullition cycle in subcooled flow boiling. The dashed-line (- -) is the HTC expected for stagnant subcooled water at 100 °C; b–d Selected images from the recorded video. Time stamp: elapsed time after subcooled flow was introduced in the microchannel. Subcooled flow: left-to-right with \(T_{\mathrm{f}}^\infty \approx\)22 °C, Dh ≈ 480 μm, \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\)≅3.5 m s−1 (t < 6 s) and \(\overline \nu _{\mathrm{flow}}\)≅3.9 m s−1 (t > 6 s). White scale bar=100 μm. Red-border circle overlay: representative size and location of laser-induced hot-spot; b Image acquired before vapor bubble release; c, d Images acquired after nucleation of a new vapor bubble; e Relative size of the vapor bubble during the ebullition cycle with respect to the 1/e2 diameter of the hot-spot (DVB/2\(\overline w\)); f Other key dimensionless thermal transport data acquired during the transient subcooled flow boiling experiment: \(h_\omega {\mathrm{/}}h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}}\), HTC ratio between micro-to-nanoscale HTC and the stagnant subcooled water HTC at 100 °C; ΔTw/ΔTw,ONB, wall superheat ratio between that measured (over 2\(\overline w\)) and that predicted at incipience;46 and \(q''_{\mathrm{f}} {\mathrm{/}}q''_{\mathrm{net}}\), ratio of the hot-spot heat flux into the coolant (wall-to-fluid) relative to total hot-spot heat flux. Laser heating power: \(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW (corresponding to \(q''_{{\mathrm{net}}} \approx\)2.9 kW cm−2 with 2\(\overline w\) ≈ 19 μm, ΔTw,ONB ≈ 43 °C, and \(h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}} \approx\)4100 kW m−2 K−1)

Figure 9 also provides data to correlate the spatiotemporal HTC with the size of the vapor bubble. Camera images of the vapor bubble at different times are provided in Fig. 9b, c, d. Based on this videography data (Supplementary Movie 1), Fig. 9e plots the relative size of the vapor bubble with respect to the 1/e2 diameter of the hot-spot (i.e., DVB/2\(\overline w\)). This bubble size data—correlated with the transient HTC—demonstrates that the upper-limit HTCs are primarily due to thermal energy exchange during microlayer evaporation (Fig. 9f). For example, no HTC enhancements are observed after the vapor bubble grows to a size beyond the hot-spot diameter—supporting established simulation and experimental results that the local HTC in the dry-spot region of the vapor bubble is equivalent to the HTC observed at heat fluxes beyond CHF. Because these studies were conducted with flat heating surfaces (i.e., a non-textured alloy wall), CHF enhancement is not attributed to imbibition-induced rewetting of the dry-spot—supporting the potential for additional heat transfer enhancements during subcooled flow boiling with a local, hot-spot cooling configuration via multi-scale (nano-to-micro) surface texturing. It is also noted that the extreme hot-spot heat fluxes reported in this work (e.g., \(q''_{\mathrm{HS}} > \)1000 W cm−2) have already been corrected for conduction losses in the microchannel wall (FS glass). The transient wall heat flux data in Fig. 9f exemplifies the transient nature of these conductive losses in microchannel (glass) wall. For example, the hot-spot heat flux into the coolant, \(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\), is at a maximum during early stages of bubble ebullition cycle (i.e., the bubble nucleation phase and microlayer evaporation phase with DVB ≲ 2\(\overline w\)), where increases in \(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\) coincide with decreases in \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}}\) (i.e., the heat flux dissipation the microchannel wall). See equations (1–3) for a constant laser heating power (\(\widetilde P\) ≈ 7.5 mW), such that during bubble ebullition there is an extreme variation in \(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) (the effective thermal conductivity of the fluid coolant) which causes significant variations in \(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\) and \(q''_{{\mathrm{FS}}}\). Most commonly corrections for parasitic losses require the use of supplementary simulations; however, the iterative nature of our data analysis method facilitates direct calculation/correction for dissipative losses into the heater substrate. It is also noted that the extreme hot-spot heat fluxes imposed in this work (\(q''_{\mathrm{f}} > \)1000 W cm−2) match very well with those projected for cooling next-generation microelectronics50. Moreover, the extreme heat fluxes complement those recently achieved via boiling in capillary-fed porous wicks26,51,52 and jet-impingement boiling53.

The presentation of convective heat transfer data in terms of both a micro-to-nanoscale HTC (h ω ) and macroscale HTC (hω→0) is rather unorthodox. However, in essence all theory for local heat transfer phenomenon reduces to the spatiotemporal heat transfer coefficient of the form: h = keff/δth, where keff is the effective thermal conductance within the thermal BL of thickness δ th . In regards to the classical notation for the wall heat flux under steady or fully developed conditions: q'' = h(TS−T∞), where h is coupled to q'' using the bulk fluid and surface temperatures. We note that for laminar BL flow with Pr > 0.5, the wall heat flux can be expressed (classically) as \(q'' = - k_0\frac{{\left( {T_\infty - T_{\mathrm{S}}} \right)}}{{\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}}}}\), where k0 is the bulk thermal conductivity and δth is expressed in terms of Prandtl and Reynolds numbers (i.e., \(\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}} \propto x\mathop {{\Pr }}\limits^{ - 1{\mathrm{/}}3} {\mathrm{Re}}_x^{ - 1/2}\))54,55. The concept of describing the local HTC as h = keff/δth is not unusual. For example, in turbulent BL flow the wall heat flux follows: \(q'' = - k^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\frac{{\left( {\bar T_\infty - \bar T_{\mathrm{S}}} \right)}}{{\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}}}}\), where \(\overline T _\infty\) and \(\overline T _{\mathrm{s}}\) are time averaged temperatures, keff = k0 + k↑, and the “conductive enhancement” (\(k_ \uparrow = C_p\epsilon _H\)) is dictated by the thermal eddy diffusivity (\(\epsilon _H\))54,55. With respect to transient heat loads and/or thermo-fluid transients (e.g., boiling, chemical reactions, transitional turbulent flow, etc.), both keff and δth are time-dependent. And as with any time-dependent quantity, such a quantity (say, δth) can be transformed from time-domain to the frequency-domain. In this study, we implement local, periodic surface heating via the TDTR pump laser, where the thermal penetration depth (\(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\)) is essentially a frequency dependent thermal BL thickness (i.e., \(\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}}^\omega = \frac{{\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}}}{{\sqrt 2 }} \propto \frac{1}{{\sqrt \omega }}\)). Thus, for periodic surface heating by the pump laser at (ωp/2π)~1 MHz, the thermal BL (interrogated by the TDTR probe laser) is very thin (e.g., \(\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}}^{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}\sim\)200 nm). And, as a consequence, the local HTC (measured by the TDTR probe laser) is large because \(h^{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}} \propto 1{\mathrm{/}}\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}}^{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}\). With this said, boiling and transient forced convection induce much slower thermo-fluid transients at timescales dictated by, for example, the period of a bubble ebullition cycle (e.g., τb = 2π/ωb, where τb ≳ 500 μs and ωb ≪ ωp). Therefore, at τb timescales, we should expect the existence of another, large length-scale thermal BL (or penetration depth) for this lower-frequency boiling phenomena—i.e., \(\delta _{{\mathrm{th}}}^{\omega _{\mathrm{b}}}\) ≳ 2 μm, assuming τb ≈ 1 ms.

Figure 10 illustrates the correlation between δth, \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\), and changes in the fluid temperature distribution from the wall (Supplementary Note 8). Figure 10 includes two main temperature plots that relate the transient data in Fig. 9 for before (THS ≈ 140 °C) and after (THS ≈ 120 °C) vapor bubble release. These two plots also include T(y) associated with the high-frequency temperature oscillations induced by the modulated pump laser (dotted-blue lines). We note that at steady-state conditions with a constant hot-spot wall temperature (i.e., no periodic laser heating), the thermal boundary layer (and corresponding local HTC) is constant. In this study, we measure both the micro-to-nanoscale HTC (h ω ) and macroscale HTC (hω→0), where h ω is the HTC measured within the nanometer thick \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\) region and hω→0 is the HTC measured within the thicker δth region. We stress that because the hot-spot dimensions are small (≲20 μm), the developing thermal BL is very thin (e.g., ≲20 μm). Moreover, the fluid temperature decays ≳50 °C within an even thinner (≈5 μm) fluid layer from the microchannel wall. For reference, the average flow-field velocity within this thin (≈5 μm) fluid layer is roughly 5% the mean cross-flow velocity (i.e., \(\bar u_{{\mathrm{flow}}}^{5{\mathrm{\mu m}}}{\mathrm{/}}\bar u_{{\mathrm{flow}}} \approx\)0.049). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the heat transfer in both δth and \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\) is largely dominated by transient conduction (Supplementary Fig. 6). With this said, during a boiling event, the bubble growth process significantly increases the overall thickness of δth. Yet, this increase in δth (during bubble growth) coincides with a significant increase in the “conductive enhancement” (i.e., an increase in k↑ due to microlayer evaporation). On the other hand, after bubble release both δth and k↑ decease. So, with respect to h = keff/δth, increases (or decreases) in δth are essentially counteracted by increases (or decreases) in k↑. In support, the boiling process in a microchannel typically yields only a moderate increase in the HTC (e.g., 2–5 times in comparison to that of single-phase flow cooling in a microchannel).

Fluid temperature profiles from the TDTR hot-spot with subcooled cross-flow in a microchannel. Fluid temperature profiles (T(y)) normal to microchannel wall for two different hot-spot wall temperatures: THS ≈ 118 °C ( ) and THS ≈ 143 °C (\({- \cdot}\)). The temperature profiles are based on both the similarity solution and the integrated BL energy equations for Pr > 1. The blue lines are the corresponding transient, nanometer length-scale temperature oscillations (\({\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}^{{\mathrm{TDTR}}}\)) due to periodic heating by the TDTR pump laser at (ωp/2π) = 976 kHz. As shown, the TDTR pump laser induces both DC and AC heating of the hotspot, where ΔTDC = THS−Tbulk, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{{\mathrm{AC}}} = {\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}^{{\mathrm{TDTR}}}\), and \(\left. {{\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}^{{\mathrm{TDTR}}}} \right|_{y = 0} \approx\)6.6 °C and ≈ 4.1 °C for THS ≈ 143°C (\({- \cdot}\)) and ≈ 118 °C (

) and THS ≈ 143 °C (\({- \cdot}\)). The temperature profiles are based on both the similarity solution and the integrated BL energy equations for Pr > 1. The blue lines are the corresponding transient, nanometer length-scale temperature oscillations (\({\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}^{{\mathrm{TDTR}}}\)) due to periodic heating by the TDTR pump laser at (ωp/2π) = 976 kHz. As shown, the TDTR pump laser induces both DC and AC heating of the hotspot, where ΔTDC = THS−Tbulk, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{{\mathrm{AC}}} = {\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}^{{\mathrm{TDTR}}}\), and \(\left. {{\mathrm{\Delta }}T_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}^{{\mathrm{TDTR}}}} \right|_{y = 0} \approx\)6.6 °C and ≈ 4.1 °C for THS ≈ 143°C (\({- \cdot}\)) and ≈ 118 °C ( ), respectively. The vertical lines correspond to the thermal BL thicknesses (δth) and thermal penetration depths (\(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\)) for each experimental scenario—i.e., a vapor bubble after nucleation (

), respectively. The vertical lines correspond to the thermal BL thicknesses (δth) and thermal penetration depths (\(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}\)) for each experimental scenario—i.e., a vapor bubble after nucleation ( , \(h_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}/h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}} > \)1) or before release (\({- \cdot}\), \(h_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}/h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}} \approx\)0.7)

, \(h_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}/h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}} > \)1) or before release (\({- \cdot}\), \(h_{\omega _{\mathrm{p}}}/h_0^{{\mathrm{scw}}} \approx\)0.7)

In comparison to previous work, the extreme heat fluxes in this study are coupled with significantly smaller heater dimensions (i.e., micron-sized hot-spots), which corresponds to extreme temperature gradients (∇T > 5 × 106 K m−1) within the “hot-spot induced” thermal boundary layer. Hence, this study demonstrates experimental two-phase cooling conditions that are not only applicable to local, transient cooling of high power-density microelectronics, but also extreme conditions that are appropriate for questioning the legitimacy-limits of traditional modes/descriptions of heat and mass transfer (e.g., limits associated with the breakdown in Fourier’s law and the limits to variations in pressure and temperature during phase-change phenomena). Nevertheless, even with these extreme heat fluxes (and/or extreme temperature gradients), this study has experimentally reproduced macroscale heat transfer coefficients (hω→0) that coincide with those that are commonly reported during two-phase flow at significantly smaller heat fluxes (i.e., hω→0 ≈ 100 kW m−2 K−1 observed with \(q''_{\mathrm{w}} \left| {\,_{{\mathrm{this}}\,{\mathrm{study}}} \approx 20 \times q''_{\mathrm{w}} } \right|{\,_{\mathrm{Lit.}}}\))—shedding optimism for adept and insightful simulations of highly non-equilibrium systems (or extreme-gradient transport) with the use of equilibrium-established materials properties (or transport properties deduced from relatively small-gradient processes).

Methods

TDTR optical setup and experimental details

The TDTR method is a pump-probe femtosecond laser diagnostic that uses two concentrically focused laser beams to heat (with the pump) and measure (with the probe) the temporal changes in thermal transport in a material (Fig. 2a, b). The method measures (in the time-domain) the cooling rate of the metal thin-film, which is dictated by both (1) the thermal effusivity (eth) of the material in contact with the metal and (2) the interfacial thermal conductance of the metal/material interface. We use a differential photodiode detector to measure the probe’s thermoreflectance, R(T), signal from the metal’s surface at a fixed pump-probe delay time (τd ≈ 100 ps). The time-domain voltage output of the detector is measured by a lock-in amplifier (Fig. 2c). The lock-in amplifier extracts the detector voltage signal into in-phase (Vin) and out-of-phase (Vout) voltage components in the frequency domain. The laser source is a Coherent Chameleon femtosecond Ti:Sapphire laser (pulse frequency: 80.1 MHz, pulse width: 140 fs, central wavelength: 787 nm). The laser output is split into two laser beams (pump and probe). The pump beam is modulated using an Electro-Optic Modulator (EOM). The pump beam is delayed with respect to the probe beam (−120 ps < τd < 3.3 ns) using a mechanical delay stage after the EOM. After passing through other optics for filtration, collimation, and polarization (Supplementary Fig. 1), the pump and probe beams are concentrically focused onto the metal thin-film on the sample using a 20× Mitutoyo, infinity corrected, long-working-distance microscope objective. For TDTR characterization of the testing stage without water in the microchannel, the pump and probe laser powers on the sample are set to minimize the DC temperature rise/heating of the pump-induced hot-spot to below 60 K and maximize the measurement signal. Pump and probe beams waists on the sample are measured as wpump ≈ 9.5 µm and wprobe ≈ 8 µm, using the knife-edge method for both x and y-directions relative to the z-axis direction of propagation. For data analysis and description in the manuscript we use a laser power weighted beam waist: \(\overline w\) = (wpump\(\widetilde P\)pump + wprobe\(\widetilde P\)probe)/\(\widetilde P\), where \(\widetilde P\) = \(\widetilde P\)pump + \(\widetilde P\)probe is the net laser heating power and \(\widetilde P\)pump is varied in the boiling experiments.

In a TDTR experiment, only the pump beam is externally modulated with an EOM. In result, the thermal penetration depth of the pump beam is significantly larger than that of the probe beam. For example, the modulation/heating frequency of the pump beam is fpump = 976 kHz, whereas the duty/pulse frequency of the probe beam is fprobe = 80.1 MHz, which corresponds to a thermal penetration depth ratio of \(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{probe}}}{\mathrm{/}}\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{pump}}} = \sqrt {f_{{\mathrm{pump}}}{\mathrm{/}}f_{{\mathrm{probe}}}} \approx\) 0.11. This means that the probe beam only heats (via AC thermal waves) the fluid within a very thin fluid region from the wall (\(\ell _{{\mathrm{th}}}^{{\mathrm{probe}}}\sim\)25 nm). Furthermore, with regards to thermo-fluid transients, the intrinsic time-delay between pump and probe beams effectively prevents the probe beam from self-probing its instantaneous heating effects as it measures the thermal decay in the pump beam’s heating waves. However, for steady-state (or low-frequency) phenomena, the DC heating from the probe laser will contribute to the rate of change in wall/surface temperature; therefore, our wall heat flux and hot-spot wall temperature calculations (equations (1–3) and (4), respectively) include the power of both the probe and pump lasers. With this said, the power of the probe laser is typically <30% of that of the pump laser, such that the hot-spot heat flux and wall temperature are primarily due to DC heating by pump laser.

Fabrication and construction of microchannel testing stage

The microchannel device comprises of a 400 µm thick PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) seal, a ~ 70 nm thick metal alloy deposited on a two inch diameter fused silica (FS) glass window, and an acrylic substrate (Fig. 2a). The microchannel device is pressure sealed and facilitates leak-free flow at mass fluxes (or Reynolds numbers) tested up to G ≈ 3840 kg m−2 s−1 (\({\mathrm{Re}}_{D} \approx\) 2050). The PDMS seal is patterned into the microchannel geometry: length (L ≈ 15 mm), width (W ≈ 600 μm), and height (H ≈ 400 μm), corresponding to a hydraulic diameter of D h ≈ 480 μm. The microchannel assembly is mounted on the main TDTR stage which has six degrees of freedom for precise alignment and motorized micro-translation of the focused local spot on the sample. The acrylic polymer substrate (1″ diameter, 1/8″ thickness) is the top wall of the microchannel, providing flow inlet and outlet into the microchannel using two 1 mm holes in the substrate. The holes are made using laser cut (conical profiles), providing tight tolerance and better sealing to flow needles. Transparency of the Acrylic substrate facilitates flow and bubble imaging (Supplementary Fig. 1). The PDMS film (≈400 μm thickness) acts as the side walls of the microchannel and the central pressure sealer. For PDMS microchannel fabrication an Acrylic cast is micro-fabricated by laser ablation processing. To remove air bubbles for better sealing and visibility, before cast molding the PDMS slurry mixture is put in a vacuum chamber for 15 min. Then, the PDMS slurry is the cast molded via heat curing at 130 °C for 25 min. The fused silica (FS) substrate/window (2″ diameter, 1/16″ thickness) is coated with metal alloy thin-film, which serves as both the laser heated wall and metal transducer for TDTR measurements. The surface roughness (Ra) of the FS window (measured via AFM) is <Ra≲0.01 μm. The high optical transmittance (>96%) at the measurement wavelength range (780–790 nm) has allowed it to act as one of the best substrates to perform TDTR experiments at solid–liquid interfaces, where both laser beams pass through the backside and then focus, adsorb, and reflect from the metal transducer. The metal thin-film, called Hf80, is an alloy composed of primarily Hf (90.2%) with ~ 3.1% Gd, ~ 1.7 % Fe, ~ 0.4 % Ni, and ≲ 0.1% Mn and Si elements (characterized via X-ray fluorescence (XRF), Ag source). Hf80 serves as both the heater and thermometer in a TDTR experiment. It is a low thermal conductivity alloy (kHf80 ≈ 10.1 W m−1 K−1, measured via TDTR). Most importantly, this thin-film alloy is robust in aggressive flow boiling environments at high heat fluxes. The Hf80 layer on FS was deposit by simultaneous DC magnetron sputtering of Hf target, pulsed laser deposition (PLD) of Gd target, and PLD of a HyMu 80 target. The Hf80 film has a clear acoustic echo with a thickness variation of 70 ± 2 nm.

Dual-syringe pump flow loop and imaging system

We use degassed, distilled water supplied at laboratory temperature for the subcooled experiments (Tbulk ≈ 22 °C), where a dual, counter-action syringe pump controls the volume flow rate in the microchannel33. Fluid flows in a closed loop between the microchannel, a degasser assembly connected to a vacuum pump, and two syringes on a syringe pump (i.e., the dual, counter-action syringe pump). The pump can provide flow rates in the microchannel up to 55 mL min−1.

Video imaging in the visible spectrum is accomplished with a digital camera attached to compound microscope optics. There are two imaging cameras. A back-view camera facilitates both flow visualization and alignment of the pump-probe lasers in the microchannel, where a front-view camera is for focusing and alignment of the TDTR beams on the Hf80 alloy. For flow visualization, we use short-pass filter (750 nm) after TDTR alignment to remove pump and probe light.

Data acquisition and analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 2c, a differential photo-detector measures the transient thermoreflectance signal (R(t)) at a prescribed pump-probe delay (τd) from the TDTR measurement region. This signal is then converted into a transient voltage signal that is subsequently transformed into a frequency-domain voltage signal (\(\widetilde {\mathrm{V}}\)(t)→V(ω) = V^{'}(ω) + iV''(ω)) using a lock-in amplifier at the reference pump heating/modulation frequency (ω = 2πfmod). We use a two-tint TDTR optical arrangement with both a combined resonant and band-pass filter (980 kHz) before the lock-in signal input to minimize 1/f and higher-harmonic measurement noise. For transient TDTR analysis, the lock-in time constant is set to 100 µs; whereas for steady-state TDTR studies, the lock-in time constant is set to 30 ms. Also, as illustrated in Fig. 2c, the transient in-phase (V^{'}(ω) = Vin) and out-of-phase (V''(ω) = Vout) lock-in voltages are recorded with a 1 GHZ bandwidth oscilloscope. LabView software is used to synchronize data acquisition between the lock-in, oscilloscope, and CCD camera. For TDTR data analysis we use the bi-directional TDTR heat transport model to extract/fit the effective thermal conductivity of the fluid coolant (\(k_{\mathrm{f}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\)) from the measured magnitude of the TDTR voltage ratio (|Vin/Vout|) during either a steady-state or transient experiments (Supplementary Notes 2 and 3). In general, TDTR method has lower measurement uncertainties at an interface between low thermal conductivity materials (e.g., water and glass) and at sub-nanosecond delay times (e.g., 80 ps < τd < 200 ps) because of higher signal-to-noise ratio56. The provided error of the “steady-state” TDTR data are associated with the standard deviation of the average values via repeated measurements at a prescribed laser heating power and delay time. For the transient TDTR data (Figs. 8–10), error bars are not provided because the measurement noise in transient signal is reflected by the transient fluctuations in the measured TDTR voltages.

HTC and its dependence on the average vapor quality (\(\overline x\)) above the hot-spot

For hot-spot wall temperatures beyond 100 °C, all TDTR ratio data were iterative fitted based on the use of both (1) the volumetric heat capacity of “saturated” liquid water (\(\overline x\) = 0, C p = Cp,f) and (2) the volumetric heat capacity of a “saturated” water–vapor mixture (0.01 < \(\overline x\) < 0.99, C p = \(\overline x\)Cp,g + (1−\(\overline x\))Cp,f). For the latter, the vapor quality is estimated based on the average, local equilibrium quality within a thin (\(\ell =\)1 μm) fluid layer above the hot-spot (2\(\overline w\) = 18.6 μm):

where xin = −0.149 is the quality of the subcooled water fed into the hot-spot region and xout is the vapor quality of the “saturated” water–vapor mixture that exits this thin, “disk-like” fluid layer above the hot-spot. Thus, we employ a simple energy balance57 to estimate the average, local vapor quality in the TDTR measurement:

where ΔT = THS−Tsat is the wall superheat, h is the HTC, \(\widetilde L\) = 2\(\overline w\), hfg is the latent heat of vaporization, and \(\overline G\) and \(\tilde D_{\mathrm{h}} \approx 4\ell\) are the average mass flux and corresponding hydraulic diameter of a thin (\(\ell =\)1 μm) fluid region above the hot-spot, respectively. The mass flux in this thin, 1 μm thick microlayer region is estimated using the experimental mass flux (G ≈ 3840 kg m−2 s−1) weighted near the wall for a Hagen–Poiseuille flow-field (\(\overline G\) ≈ 38.4 kg m−2 s−1).

Equation (7) is commonly used in microchannel flow boiling studies using the wall heat flux (q″)—as opposed to the product of the HTC and the wall superheat, q″ = hΔT (as implemented in equation (7) for this study). We are unaware of the use of equations (6) and (7) in confined (or pool) boiling studies; yet, from an energy balance perspective it should still be valid given an accurate prediction of the average mass flux and inlet quality (xin) into the microlayer region during the single bubble ebullition cycle. Nevertheless, with knowledge of both the magnitude of the HTC and the wall superheat, equations (6 and 7) can be used to estimate the average vapor quality (\(\overline x\)) in the microlayer region (Supplementary Note 4, Supplementary Fig. 7).

As stated previously, we also conducted HTC data analysis based on the use of a volumetric heat capacity of ‘saturated’ liquid water (i.e.,\(\overline x\) = 0, \(C_p^{{\mathrm{fg}}} = C_{p,{\mathrm{f}}}\)). A comparative assessment of relative significance between these two different data analysis approaches is provided in Supplementary Note 4. The significance between these two different data analysis approaches was relatively minor with respect to predicted micro-to-nanoscale HTC (h ω ) because TDTR measures the fluid’s thermal effusivity (\(e_{{\mathrm{th}}} = \sqrt {k\rho c_p} = \sqrt {kC_p}\)) such that increases (decreases) in C p will be counteracted by decreases (increases) in k. However, variations in C p do moderately influence the predicted macroscale HTC (hω→0) because both the hot-spot temperature (THS, equation (4)) and wall heat flux (\(q''_{\mathrm{f}}\), equation (2)) are functions of k (see, Supplementary Fig.s 8–10 and corresponding discussion in Supplementary Note 4).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Cho, J. & Goodson, K. E. Thermal transport: cool electronics. Nat. Mater. 14, 136–137 (2015).

Suzuki, K., Yuki, K. & Mochizuki, M. Application of boiling heat transfer to high-heat-flux cooling technology in power electronics. Trans. Jpn Inst. Electron. Package 4, 127–133 (2011).

Marcinichen, J. B., Olivier, J. A. & Thome, J. R. On-chip two-phase cooling of datacenters: cooling system and energy recovery evaluation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 41, 36–51 (2012).

Li, Z. & Kandlikar, S. G. Current status and future trends in data-center cooling technologies. Heat. Transf. Eng. 36, 523–538 (2015).

Puscasu, O. et al. A disruptive technology for thermal to electrical energy conversion. Microelectron. J. 45, 554–558 (2014).

Sung, M. K. & Mudawar, I. Single-phase and two-phase hybrid cooling schemes for high-heat-flux thermal management of defense electronics. J. Electron. Package 131, 21013 (2009).

Podowski, M. Z. & Podowski, R. M. Mechanistic multidimensional modeling of forced convection boiling heat transfer. Sci. Technol. Nuclear Installations 2009, 387020 (2009).

Collier, J. G. & Thome, J. R. Convective Boiling and Condensation 3rd edn, 148–163 (Oxford Univeristy Press, Oxford, 1994).

Carey, V. P. Liquid Vapor Phase Change Phenomena: An Introduction to the Thermophysics of Vaporization and Condensation Processes in Heat Transfer Equipment 2nd edn, Vol. 221, 259–273 (CRC Press, New York, 2008).

Bigham, S. & Moghaddam, S. Microscale study of mechanisms of heat transfer during flow boiling in a microchannel. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 88, 111–121 (2015).

Prosperetti, A. Vapor bubbles. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 49, 221–248 (2017).

Warrier, G. R., Basu, N. & Dhir, V. K. Interfacial heat transfer during subcooled flow boiling. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 45, 3947–3959 (2002).

Rahman, M. M., Ölçeroğlu, E. & McCarthy, M. Role of wickability on the critical heat flux of structured superhydrophilic surfaces. Langmuir 30, 11225–11234 (2014).

Kim, B. S., Lee, H., Shin, S., Choi, G. & Cho, H. H. Interfacial wicking dynamics and its impact on critical heat flux of boiling heat transfer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 191601 (2014).

O’Hanley, H. et al. Separate effects of surface roughness, wettability, and porosity on the boiling critical heat flux. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 024102 (2013).

Chen, R. et al. Nanowires for enhanced boiling heat transfer. Nano Lett. 9, 548–553 (2009).

Buongiorno, J. et al. Micro- and nanoscale measurement methods for phase change heat transfer on planar and structured surfaces. Nanoscale Microsc. Thermophys. Eng. 18, 270–287 (2014).

Bigham, S. & Moghaddam, S. Role of bubble growth dynamics on microscale heat transfer events in microchannel flow boiling process. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 244103 (2015).

Plawsky, J. L. et al. Nano- and microstructures for thin-film evaporation- a review. Nanoscale Microsc. Thermophys. Eng. 18, 251–269 (2014).

Li, W., Yang, F., Alam, T., Khan, J. & Li, C. Experimental and theoretical studies of critical heat flux of flow boiling in microchannels with microbubble-excited high-frequency two-phase oscillations. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 88, 368–378 (2015).

Rao, S. R. & Peles, Y. Spatiotemporally resolved heat transfer measurements for flow boiling in microchannels. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 89, 482–493 (2015).

Rao, S. R., Houshmand, F. & Peles, Y. Transient flow boiling heat-transfer measurements in microdomains. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 76, 317–329 (2014).

Solotych, V., Kim, J. & Dessiatoun, S. Local heat transfer measurements within a representative plate heat exchanger geometry using infrared (Ir) thermography. J. Enhanc. Heat. Transf. 21, 353–372 (2014).

Chandramohan, A., Weibel, J. A. & Garimella, S. V. Spatiotemporal infrared measurement of interface temperatures during water droplet evaporation on a nonwetting substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 041605 (2017).

Dhillon, N. S., Buongiorno, J. & Varanasi, K. K. Critical heat flux maxima during boiling crisis on textured surfaces. Nat. Commun. 6, 8247 (2015).

Palko, J. W. et al. Approaching the limits of two-phase boiling heat transfer: high heat flux and low superheat. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 253903 (2015).

Yu, X., Woodcock, C., Wang, Y., Plawsky, J. L. & Peles, Y. Enhanced subcooled flow boiling heat transfer in microchannel with Piranha Pin Fin. J. Heat. Transf. 139, 112402 (2017).

Duan, X., Phillips, B., McKrell, T. & Buongiorno, J. Synchronized high-speed video, infrared thermometry, and particle image velocimetry data for validation of interface-tracking simulations of nucleate boiling phenomena. Exp. Heat. Transf. 26, 169–197 (2013).

Kim, H., Park, Y. & Buongiorno, J. Measurement of wetted area fraction in subcooled pool boiling of water using infrared thermography. Nucl. Eng. Des. 264, 103–110 (2013).

Wu, X. & Hull, R. The material dependence of temperature measurement resolution in thermal scanning electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 113107 (2013).

Abram, C., Pougin, M. & Beyrau, F. Temperature field measurements in liquids using ZnO thermographic phosphor tracer particles. J. Exp. Fluids 57, 1432–1114 (2016).

Chamarthy, P., Garimella, S. V. & Wereley, S. T. Measurement of the temperature non-uniformity in a microchannel heat sink using microscale laser-induced fluorescence. Int. J. Heat. Mass Trans. 53, 3275–3283 (2010).

Mehrvand, M. & Putnam, S. A. Probing the local heat transfer coefficient of water-cooled microchannels using time-domain thermoreflectance. J. Heat. Transf. 139, 112403 (2017).

Putnam, S. A. et al. Interfacial heat transfer during microdroplet evaporation on a laser heated surface. Int. J. Heat. Mass Trans. 55, 6307–6320 (2012).

Cahill, D. G. Analysis of heat flow in layered structures for time-domain thermoreflectance. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 5119–5122 (2004).

Ding, D., Chen, X. & Minnich, A. J. Radial quasiballistic transport in time-domain thermoreflectance studied using Monte Carlo simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 143104 (2014).

Schmidt, A. J., Chiesa, M., Chen, X. & Chen, G. An optical pump-probe technique for measuring the thermal conductivity of liquids. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 064902 (2008).

Feser, J. P. & Cahill, D. G. Probing anisotropic heat transport using time-domain thermoreflectance with offset laser spots. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 104901 (2012).

Feser, J. P., Liu, J. & Cahill, D. G. Pump-probe measurements of the thermal conductivity tensor for materials lacking in-plane symmetry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 104903 (2014).

Wang, L., Cheaito, R., Braun, J., Giri, L. A. & Hopkins, P. E. Thermal conductivity measurements of non-metals via combined time- and frequency-domain thermoreflectance without a metal film transducer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 094902 (2016).

Incropera, F. P. DeWitt, D. P. Bergman, T. L. & Lavine, A. S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 7th edn, Vol. 1003, 655–673 (John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2011).

Leong, K. C., Ho, J. Y. & Wong, K. K. A critical review of pool and flow boiling heat transfer of dielectric fluids on enhanced surfaces. Appl. Therm. Eng. 112, 999–1019 (2017).

Buchholz, M., Auracher, H., Lüttich, T. & Marquardt, W. A study of local heat transfer mechanisms along the entire boiling curve by means of microsensors. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 45, 269–283 (2006).

Henry, C. D. & Kim, J. A study of the effects of heater size, subcooling, and gravity level on pool boiling heat transfer. Int. J. Heat. Fluid Flow. 25, 262–273 (2004).

Stephan, P. & Hammer, J. A new model for nucleate boiling heat transfer. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 30, 119–125 (1994).

Basu, N., Warrier, G. R. & Dhir, V. K. Onset of nucleate boiling and active nucleation site density during subcooled flow boiling. ASME J. Heat. Transf. 124, 717–728 (2002).

Bernardin, J. D. & Mudawar, I. The Leidenfrost point: experimental study and assessment of existing models. ASME J. Heat. Transf. 121, 894–903 (1999).

Putnam, S. A. et al. Microdroplet evaporation on superheated surfaces. Int. J. Heat. Mass Trans. 55, 5793–5807 (2012).

Jiang, P., Qian, X. & Yang, R. Time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) measurements of anisotropic thermal conductivity using a variable spot size approach. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 074901 (2017).

Mudawar, I. Assessment of high-heat-flux thermal management schemes. IEEE Trans. CPMT: Compon. Packag. Technol. 24, 122–141 (2001).

Semenic, T. & Catton, I. Experimental study of biporous wicks for high heat flux applications. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 52, 5113–5121 (2009).

Nam, Y., Sharratt, S., Cha, G. & Ju, Y. S. Characterization and modeling of the heat transfer performance of nanostructured Cu micropost wicks. J. Heat. Transf. 133, 101502 (2011).

Chen, Y.-J., Li, Y.-Y. & Liu, Z.-H. Experimental study on the stagnation line heat transfer characteristics with high-velocity free slot jet impingement boiling. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 91, 282–292 (2015).

Bejan, A., Convection Heat Transfer 4th edn, 30–56, 325–327, 338–342 (John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2013).