Abstract

Existence of 2π-planar domain walls (DWs) are often reported for transition metal-rare-earth (TM/RE) layered systems. The magnetization process of such two-dimensional randomly anisotropical system in the form of 2π-DWs is directly correlated with topologically stable helices. Here, instead of TM/RE, we have investigated [Dy/Tb]10 multilayers involving two different anisotropic layers of rare-earth/rare-earth (RE/RE). Using magnetization and susceptibility as function of temperature along with thermo-remanent magnetization measurements we have confirmed superspin-glass type of behavior within this RE/RE system. Additionally, an exchange bias field up to –0.88 kOe (–88 mT) was also revealed for such rare-earth based multilayers. Interestingly, using detailed analysis of the polarized neutron reflectometry profiles, we find evidences of superimposed helical magnetic configurations within both materials of Dy and Tb associated with spin-frustrated interfaces. Furthermore, magnetization fluctuations around the mean magnetization from vertically uncorrelated domains were observed with polarized off-specular neutron scattering. We believe that coexistence of helical ground states with superspin-glass-like ordering are fundamentally instrumental for topologically stability in RE/RE systems, which in principle, can be exploited in all-spin-based technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thin films composed of rare-earth (RE) metals are known to form a helical antiferromagnetic (AF) structure due to competing magnetoelastic, crystalline anisotropy, and exchange interactions1,2,3. These interactions can lead to topologically stable spin configurations, which are virtually indispensable in all-spin-based technology3. Numerically, Vedmedenko et al. have shown that magnetic states corresponding to modulated helices with integer number of twists, commensurate with the chain’s length, are topologically stable4. Such stability comes without the presence of chiral Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction relevant in skyrmions, where its shape protects it from trivial unwinding. The quantized energy spectrum within finite magnetic chains results in stabilizing topologically protected configurations of helices. Such helices, initially twisted in an external magnetic field, stay stable even without the presence of a field as they are created by exchange interaction and does not allow a trivial unwinding5.

Using polarized neutron reflectivity (PNR) measurements, it was shown earlier that AF-coupling at a pure transition metal-rare earth (TM/RE) (e.g., Fe/Tb) interface felicitates the formation of π or 2π planar domain walls (DWs)6,7. Within a multilayer, formation of such 2π-DWs resemble a helical form leading to double hysteresis loop (DHL). DHLs are associated with exchange-bias (EB)-like shifts along and opposite to the field cooling axis below the ordering temperature of RE. The energy it takes to form a DW within the soft layer, which remains frozen upon cooling, results in the EB shift. Subsequently, exchange coupling and helical phase characteristics were also reported within both layers of Fe and Dy, comprising the multilayer8. At low fields, the TM/RE layers exhibit ferrimagnetic spin alignment, which form twisted magnetic helices in the form of planar 2π-DWs. However, at higher fields, a more complicated but stable and continuous helical arrangement was observed. In another case, evidence of such stable helices within single layer Er films was shown using PNR2.

Even though TM/RE multilayers are commonly studied, RE/RE multilayers remain scantily probed. Some combinations of epitaxial RE/Y multilayers showing modified helical moment configurations had been reported in the past using neutron diffraction9. Epitaxial erbium thin films and Er-Y superlattices were reported to show the effects of basal-plane strain on the modulated spin structure by Borchers et al.10. However, all strain related phenomena are expected in epitaxial films and are insignificant in polycrystalline ones. Moreover, Y is a transition metal but is often classed as RE due to its similar electronic behavior. Note that exchange coupling has also been observed in several TM/RE systems11,12,13, but not in RE/RE systems. In contrast to the direct exchange in the transition elements, RE magnetism finds its explanation in an indirect exchange interaction known as the Ruderman-Kittel-Kasuya-Yosida (RKKY) interaction. Experimentally, it is found that in addition to normal ferromagnetism, some of the rare earths exhibit a helical AF state over a limited temperature range. On application of an external magnetic field, the helical state is radically distorted and eventually collapses into a ferromagnetic configuration. Presence of large orbital momentum in Tb, Dy, and Ho leads to strong spin-orbit coupling and larger magnetic anisotropy14. Moreover, a large difference in spin-orbit coupling for different RE elements, would consequently have a significant influence on the overall demagnetization processes. In a recent example of RE/RE system, Er-Tb superlattice has been shown to posses long range magnetic order despite their competing anisotropy directions. Probing the vertically correlated magnetic structures by off-specular polarized neutron scattering the existence of magnetic vortex-like domains associated with magnetic helical ordering within the Er layers was evidenced3.

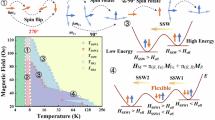

Here, we investigate polycrystalline [Dy10/Tb10]10: [Dy(10.0 nm)/Tb(10.0 nm)]×N=10 multilayers on Si substrates where N is the number of bilayer repetitions. The temperature ranges where Tb and Dy show AF helical magnetization, are distinctly different in bulk. For Tb, this range hovers around 220 K, whereas for Dy it ranges approximately between 180–80 K, below which both are ferromagnetic6,8. We found that the multilayer is magnetically very hard, with a saturation magnetization beyond 50 kOe (5000 mT). Most interestingly, we observed an EB coupling up to –0.88 kOe (–88 mT) due to strong pinning at spin-frustrated interfaces. Direct current (DC) magnetization as a function of temperature and alternating current (AC) susceptibility measurements for various frequencies and temperature confirmed such superspin-glass (SSG) type of behavior for the multilayer. Additionally, thermo-remanent magnetization (TRM) confirms the dynamics in the SSG phase and test its scaling behavior. Using PNR and polarized off-specular neutron scattering, we determined the magnetic profile of the multilayer indicating spin configurations like helices and associated magnetic fluctuations within the stack. Double spin spirals within Dy and Tb leads to spin-frustrated SSG-like ordering at the interfaces. Stability of the 2π-DWs at a higher field ensures their topological stability. Our study is expected to open up a path for a broader base of researches as it describes novel phases of long range helical ordering in RE/RE polycrystalline system across spin-frustrated interfaces with innumerable possible combinations to explore in the future.

Results

X-ray characterization

For details on the initial characterization such as X-ray reflectivity (XRR) and X-ray diffraction (XRD), see the discussion in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Magnetization measurements

In order to characterize the magnetic properties of the multilayer, the magnetization M(T) was measured as a function of temperature for [Dy10/Tb10]10. We applied different magnetic field strengths Ha = 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, and 50.0 kOe (25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000, and 5000 mT) during the measurements. All samples were either initially cooled down to 5 K in presence of a field HFC = 70 kOe (7000 mT) to obtain the field cooled (FC) curves or with no magnetic field to obtain the zero field cooled (ZFC) curves. The M(T) curves are shown in Fig. 1a, b. The ZFC curves show a broad peak which can be referred to as blocking/freezing temperature (TF) whereas the FC curves do not show a temperature independent platform-like behavior. A well-defined irreversibility temperature (Tirr), which is indicated by the temperature where FC and ZFC curves diverge, could be identified. The gradual convergence of ZFC and FC curves with increasing field, indicates the attainment of similar type of magnetic configuration near equilibrium as exemplified for 50 kOe (5000 mT). As both 5/5 ([Dy5/Tb5]10) and 10/10 ([Dy10/Tb10]10) multilayers show a similar behavior (see Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), we restrict further analysis to the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample only. Note that for neutron measurements, sub-loops were measured for a limited FC condition of 10.0 kOe (1000 mT) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Field cooled (FC) and zero field cooled (ZFC) measurements. a, b The plot of in-plane magnetization versus temperature for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample. The measurements were done on heating at various fields (indicated in the figure) after ZFC and FC in 70 kOe (7000 mT). A broad maximum can be observed for the ZFC curves (TF) followed by a furcation point (Tirr) with the FC curves. Presence of a maximum for the ZFC curves at fields of 10 kOe (1000 mT) and lower indicates a freezing-like state. c The plot of Tirr and TF as estimated from the ZFC and FC curves versus increasing fields of measurement Ha. The lines are guide to the eye. Error bars represent standard error of the measured temperature value. d The plot of Ha2/3 versus Tirr showing Tirr(0) = 205 K. The blue line is the linear fit to the data following the Almeida-Thouless (AT) equation. The inset of (d) shows phase diagram of the same in a plot of Ha2/3 as a function of 1−Tirr(Ha)/Tirr(0). The region below the line is SSG while it is SPM above

The transition from ferromagnetism to superparamagnetism (SPM) or super spin glass (SSG) behavior is generally expected for discrete nano-clusters (collection of nanoparticles) where individual magnetic moments within clusters are thermally unstable. The SSG state is believed to result from frustration generated by dipole–dipole interactions among superspins (magnetic moments of nano-clusters) and from disorders in the system (e.g., the random distributions of clusters, positions, sizes and anisotropy-axis orientations)15. The irreversibility temperature (Tirr) and the blocking or freezing temperature TF as a function of field is shown in Fig. 1c for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 multilayer. TF is slightly below Tirr, which in some respects resembles cluster-glassy behavior16. They both show a gradual decrease which suggests that the frozen state is suppressed by the field (a similar behavior is seen for [Dy5/Tb5]10: see Supplementary Fig. 2).

The shift of Tirr to lower temperatures can follow the Almeida-Thouless (AT) line indicating a SSG-like behavior17,18. The AT line is expressed as

where Tirr(0) is the zero field freezing temperature and ΔJ is the width of the distribution of exchange interactions. The plot of the measuring field \(H_{\mathrm{a}}^{2/3}\) as a function of Tirr has been shown in Fig. 1d, which fits to a straight line following the AT equation. The line cuts the x axis at around Tirr(0) = 205 K for [Dy10/Tb10]10 (Tirr(0) = 210 K for [Dy5/Tb5]10: see Supplementary Fig. 2) which is similar to TF. AT line separates a nonergodic (SSG) phase from a ergodic (SPM) one. In the inset of Fig. 1d we additionally plot Ha2/3 as a function of 1 − Tirr(Ha)/Tirr(0), showing the transition line separating the SPM and SSG phases19.

In-plane magnetic field hysteresis loops were measured at seven different temperatures after field cooling in 70 kOe (7000 mT) from 300 K and are shown in Fig. 2a for [Dy10/Tb10]10. Apparently, there are no distinct DHLs as observed earlier for TM/RE multilayers6,8. The hysteresis loops show high saturation fields of 50 kOe (5000 mT), large increments in their coercive fields (Hc) up to 1.1 kOe (110 mT) and an increase in exchange bias fields (HEB) up to –0.65 kOe (–65 mT) for [Dy10/Tb10]10 (HEB = –0.88 kOe or –88 mT for [Dy5/Tb5]10), particularly at temperatures below 75 K.

Hysteresis loop measurements. a Hysteresis loops for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample at various temperatures after field cooling in 70 kOe (7000 mT) from 300 K. The loops are corrected for their diamagnetic contributions. b Plot of coercive field Hc and exchange bias HEB (negative bias) at various temperatures. c Plot of Hc versus temperature \(T^{\frac{1}{2}}\) and its linear fit showing the maximum for the zero field cooled (ZFC) curves TF(0) = 205 K. Error bars in (b) and (c) represent standard error of the estimated field value. The plot can also be fitted with an exponential function which leads to an ambiguity regarding the phase identification

The temperature dependence of \(H_{\mathrm{c}} = (H_{\mathrm{c}}^{ + \alpha } - H_{\mathrm{c}}^{ - \alpha })/2\) (blue triangles) and \(H_{{\mathrm{EB}}} = (H_{\mathrm{c}}^{ + \alpha } + H_{\mathrm{c}}^{ - \alpha })/2\) (black squares), where \(H_{\mathrm{c}}^{ + \alpha / - \alpha }\) are the coercive fields for the positive and negative field axes, are shown in Fig. 2b for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 multilayer. One can see a gradual decrease of the coercivity Hc with increasing temperature. The HEB value decreases gradually with increase in temperature and vanishes at around 200 K. Note that the temperature dependence of the remanent magnetizations MR = (|M|(H) + |M|(−H))/2 (red circles in Fig. 2b) goes to zero also at 200 K (a similar behavior was seen for the [Dy5/Tb5]10 multilayer as well).

Dy exhibits a rich magnetic phase diagram, including a few modulated magnetic phases and also posses one of the highest intrinsic magnetic moments (bulk value of 10.6 μB/atom)20,21. The magnetic modulations propagate coherently over a long range, even with intervening nonmagnetic layers, via RKKY interaction. The magnetic moment of Tb (with bulk value of 9.0 μB/atom and 6.4 μB/atom at 10 K in epitaxial thin film22) is slightly lower than Dy. The range of stability of the helical state in Tb is quite restricted compared to Dy. An applied field of less than 1 kOe (100 mT) will produce a transition to the ferromagnetic state in Tb, while in Dy the reminiscent of the helical state can be found even at lower temperatures8. Moreover, due to basal–plane anisotropies existing both in Dy (a axis) and Tb (b axis), a combination of these two RE elements may lead to an exchange coupling as well. With an increase in spin-frustration in the pinning layers at the interfaces, a transition from a helical AF domain state to a spin-glass type state might be expected which can eventually increase the HEB field.

If we assume that randomly oriented nano-clusters are following the usually observed \(T^{\frac{1}{2}}\) law of nucleation and propagation for an ensemble of non-interacting clusters, it should show a linear behavior23. We plot Hc versus \(T^{\frac{1}{2}}\) in Fig. 2c, a linear fit to the plot cuts the x axis at around TF(0) = 205 K for [Dy10/Tb10]10 (TF(0) = 210 K for [Dy5/Tb5]10). One may note that the peaks in the respective ZFC curves, corresponding to the average SPM/SSG freezing temperature TF, is similar to TF(0). However, the same plot can also be subjected to an exponential fit which leads to an ambiguity. In such case of low interacting system, it often becomes difficult to distinguish between the SSG and SPM type of phases from the analysis of the hysteresis curves alone19. The rate of change of d2HEB/dT2 with respect to temperature does not exhibit any peak as was reported earlier for SSG nanoparticles24. Thus, the appearance of HEB and the onset of spin blocking/freezing (TF(0)) may not be interdependent. The physical origin of exchange-coupling is rather due to the two hard magnetic layers with two different anisotropies5.

We measured the temperature dependence of the AC magnetic susceptibility over a frequency range of 10 to 10,000 Hz in the presence of a small AC field of 0.01 kOe (1 mT) to differentiate between the SPM an SSG characteristic. Figure 3a shows the frequency dependence of the real part of the susceptibility (χ′(T)) versus temperature for [Dy10/Tb10]10. The curves show peaks centered at around \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}} \simeq 206\,{\mathrm{K}}\). The paramagnetic Curie temperature at around TC = 230 K can also be estimated from a 1/χ′(T) versus temperature plot. The \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}\) peaks decrease in magnitude and shift to higher temperature with increasing driving frequency. The shift gives the activation energy and is characteristic of the SPM-type or SSG-type behavior. Non-interacting SPM clusters are expected to show larger frequency dependence than SSG clusters, because the distribution of relaxation times is characteristic for the SSG phase. To qualitatively analyze the dynamical behavior, three common models are employed in discerning the supermagnetic dynamics. The models are embodied in the (i) Néel-Arrhenius law25,26, (ii) Vogel-Fulcher law27,28 and (iii) power law29 in addition to the (iv) empirical equation7,30.

AC susceptibility measurements. a The temperature dependence of the real part of the AC susceptibility (χ′(T)) for frequencies ranging from 10 to 10,000 Hz for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample. Frequency dependence of the χ′(T) peak \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{AC}\) and its fit using b the Néel-Arrhenius model, c the Vogel-Fulcher model and d the critical slowing down model. Error bars, typically of the symbol sizes, represent standard error of the estimated \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{AC}\) values in (b), (c) and (d)

Noninteracting SPM clusters generally obey the Néel-Arrhenius law25,26.

where τ0 = (2πf0)−1 is the relaxation time for the attempt frequency f0 and τm = (2πfm)−1 is the measuring time (~102 s for the DC magnetization measurement) for the measuring frequency fm. Here, ΔE (=KAV) is the activation energy, KA is the anisotropy constant, kB (=1.38 × 10−16 erg/K) is the Boltzmann constant and V is the average cluster volume critical for SPM or SSG state. The value of τ0 typically ranges from ~10−9 – 10−13 s for a SPM behavior31. In Fig. 3b, the dependence of \(\left( {T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}} \right)^{ - 1}\) on the natural logarithm of the measurement frequency is plotted. A linear fit to the data yields a slope of ΔE/kB = 190,344 K, which implies an unreasonably small value of τ0. Failure of the Néel-Arrhenius expression in describing the dynamics suggests the presence of non-ignorable magnetic dipole–dipole interactions.

Weak interactions among spin nano-clusters are taken into account within the Vogel-Fulcher law27,28. Phenomenologically, it describes the frequency response of the relaxation time and is expressed by

where T0 is the characteristic temperature that accounts for the static interaction field of the surrounding clusters. In Fig. 3c, a plot of ln(τm) versus \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}\) is shown. The values obtained from a fit to the equation 3 are ΔE/kB ~ 112 K, T0 ~ 203 K and τ0 ~ 10−13 s. From the linear fits to the plots of \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}\) versus 1/ln(τ0/τm), there can be a few possible combinations where τ0 can be within a reasonable range yielding different ΔE/kB values32. For example, τ0 = 10−17 s corresponds to ΔE/kB = 214 ± 12 K and T0 = 201 ± 0.4 K while τ0 = 10−9 s corresponds to ΔE/kB = 35 ± 2 K and T0 = 205 ± 0.2 K (see the discussion under AC susceptibilities within Supplementary Note 2 and subsequent Supplementary Fig. 5a). These values are reasonably comparable with the conventional spin glass behavior for which the typical value of τ0 ~ 10−10–10−13 s or even lower33. A longer τ0 yields dynamics on a shorter accessible time scale and are probed within the experimental time window available for a SSG type of behavior. The maxima observed in χ′(T), would therefore correspond to the freezing of weakly interacting moments of the nano-clusters.

The power law relies on the relation of critical slowing down of the relaxation time near the transition temperature. It is also known as the scaling hypothesis, which predicts the existence of an equilibrium phase transition29. The relaxation behavior corresponding to a characteristic temperature TSSG for superspin-glass behavior is expressed by

where τ* is a relaxation time for each nano-cluster, zν is the dynamical scaling critical exponent constant34 related to the correlation length ξ, which is a measure of the size of the lateral coarsening (ν describes the divergence while z is involved in the dynamical scaling hypothesis τm ~ ξz). Tholence criterion requires a very small value for \(\eta = (T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}} - T_{{\mathrm{SSG}}})/T_{{\mathrm{SSG}}}\) in order to comply with the SSG type of behavior. In Fig. 3d we plot the variation of τm (in log scale) versus \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}\). A fit to the Eq. (4) yields zν ~ 5.0 (typical range for SSG is between 4 to 12), τ* ~ 3 × 10−15 s, and TSSG ~ 206.8 K. Considering this TSSG value, the maximum value for η ~ 0.01. Alternatively, linear fits to the plots of ln(τm) versus \(\ln [(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}} - T_{{\mathrm{SSG}}})/T_{\mathrm{SSG}}]\) yield a few possible values, for e.g., zν = 4.0 ± 0.4 and τ* = 3 × 10−13±1 s for TSSG = 207.0 K and zν = 6.0 ± 0.4 and τ* = 5 × 10−17±1 s for TSSG = 206.6 K (see Supplementary Fig. 5b). These values are fairly comparable with the typical values reported for a SSG type of behavior35. One may note that the values of TF(0), Tirr(0) and TSSG all coincide roughly with the helical ordering temperature in bulk Tb.

Lastly, another useful and sensitive criterion to distinguish between the freezing and the blocking processes is to determine the relative shift of the χ′(T) peak with frequency using the empirical equation

where \(\overline {T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}}\) is the mean value of the frequency dependent maximum in χ′(T), whereas \(\Delta T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}\) is the difference in \(T_{{\mathrm{max}}}^{\mathrm{AC}}\) over the frequency interval Δlog10(fm)35,36. Typically, for SSG phase, the parameter p assumes values of 0.0045–0.06 whereas for SPM phase, it is between 0.1–0.530. The parameter p for the SPM phase is typically an order or two higher than that for the SSG phase. Here, we obtain p = 0.0028, which again points towards an interacting SSG-type of behavior7. The obtained lower value of p indicates that the accessible time scale for SSG dynamics is indeed shorter.

For TRM measurements37, the sample is heated to a temperature above the superspin-glass transition temperature (TSSG = 205 K) and subsequently cooled to a measuring temperature (Tm = 143 K) in the presence of a small excitation field, HTRM = 0.005 kOe (0.5 mT). After a waiting time tw, the field is switched off and the relaxation of the magnetization is measured over t = 30,000 s. A waiting time dependence was examined to evaluate the aging character of the dynamics. The field should remain small enough so that the response of the sample remains in the linear regime (non-perturbative probe) to avoid an influence of the field on aging.

Figure 4a shows the relaxation of magnetization MTRM(t) for [Dy10/Tb10]10, normalized to the field cooled magnetization (MFC) for values of waiting times tw varying from 30 s, 300 s, 1,000 s, 3,000 s to 30,000 s. The plot for tw = 0 s (t0) is used for reference. It can be seen that the relaxation depends on the value of tw: this illustrates the aging character of the dynamics. Longer the tw, slower is the relaxation, indicating a stiffening of the sample response during the waiting time. The relaxation trend S(t) = ΔMTRM/log(t) can be used to show the changes in MTRM(t) more clearly, where ΔMTRM = MTRM(tw) − MTRM(t0). Note that S is slightly different from the commonly defined derivative term. Nevertheless, the quantity S is equivalent to the relaxation time distribution, a wide breadth of which is the reason behind the slow and non-exponential relaxation of the response function in a SSG state. The inflection point tinfl in the curves can be found from the S(t) versus log(t) plot in Fig. 4b.

Thermo-remanent (TRM) measurements. a Normalized relaxation of the TRM MTRM(t) at 143 K for [Dy10/Tb10]10 after different waiting times (tw) as indicated in the figure; excitation field HTRM = 0.005 kOe (0.5 mT). The curve for tw = 0 is the reference curve. b Corresponding relaxation trend S(t) curves versus log(t), S = ΔMTRM/log(t). c Scaling plot of the same MTRM(t) curves as a function of the scaling variable λ/tw. d Log-log plot of the inflection point time tinfl versus tw. Error bars represent standard error of the estimated tinfl values. The dashed line corresponding to log(tinfl) = log(tw), shows the deviation of the data points from the line

Two features distinguish a SSG behavior from an atomic spin glass behavior. Firstly, a departure from approximate scaling in the TRM curves versus the scaling variable λ/tw plot in Fig. 4c where the effective time λ = tw[(1 + t/tw)1−μ − 1]/[1 − μ] with μ = 0.5, which is much smaller than is normally found for atomic spin glasses (0.7–0.9) and is similar to that of SSG (0.4)38. Values of μ ≠ 1 indicate by how much the effective age of a SSG deviates from the nominal age; i.e., the experimental waiting time, tw15. Secondly, log(tinfl) ≠ log(tw), which is unlikely for an atomic spin glass where an approximate scaling is usually observed (Fig. 4d). Thus, the SSG behavior is well established for the multilayer under investigation.

Polarized neutron scattering measurements

For the investigation of the magnetic structure of the sample, PNR measurements were carried out. While specular scattering is used for depth information, off-specular scattering can deliver information on lateral structure. A sketch of the neutron scattering geometry is shown in Fig. 5a. Figure 5b shows the sketch of lateral magnetic domains with respect to the lateral projection of the neutron coherence length l||, which is deterministic in observing specular and off-specular scattering. For details see the “Methods” section.

Neutron scattering geometry. a Illustration of the in-plane neutron scattering geometry. Here, MFM is the in-plane magnetization vector making an angle ϕA with respect to the field (Ha) along the y axis. The spatial fluctuation of MFM from region to region is designated by ΔϕA. b Sketch of lateral magnetic domains (green arrows) with respect to the coherence ellipse (shaded green area) or the lateral projection of the neutron coherence length l||. Here, for αi ≠ αf, one may observe off-specular scattering where αi and αf are incident and exit angles for scattering. When the magnetic domains are smaller than the coherence ellipse length lx, both specular and off-specular scattering are observable. When the domains sizes are larger than lx, mainly specular scattering are observable

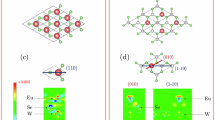

PNR measurements were performed for different magnetic histories of [Dy10/Tb10]10. Figure shows the specular polarized neutron intensity profiles along Qz (see the “Methods” section for details) and their fits. The measurements were done after cooling the sample to 10 K in zero field (ZFC) (Fig. 6a) and in +10.0 kOe or +1000 mT (FC) (Fig. 6b). Both measurements took place at an external field Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT). The corresponding hysteresis sub-loops measured at 10 K are shown for the FC condition in Supplementary Fig. 4. The fits were initialized using simple models of block-potentials. The parameters used for fitting were the individual layer thicknesses along with the nuclear and magnetic scattering length densities (SLDs) of individual layers. The errors in the thickness of the layers are ±0.2 nm, while that for the nuclear and magnetic SLDs ρn and ρm are ±0.1 × 10−6 Å−2 and ±0.05 × 10−6 Å−2, respectively. As the top layer is susceptible to oxidation, we assumed a different ρn and ρm values when compared with the stack. The interface roughness is \(2.0({\!}\pm 0.5)\,{\mathrm{nm}}\). Fitted parameters were obtained using the minimization of the reduced chi-squared (χ2 or the goodness of fit) value. The insets in the figure for PNR show the fitted SLDs values ρn and ρm versus the thickness of the multilayer.

Polarized neutron reflectivity (PNR) measurements. Specular neutron reflectivity patterns (solid symbols) along with their best fits (open symbols) as a function of Qz for the non-spin flip (NSF) [R−− (black) and R++ (red)] and spin flip (SF) [R+− (blue) and R−+ (green)] channels measured at a reduced-remanence field Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) after a zero field cooled (ZFC) and b field cooled (FC) and measured at 10 K for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample. Error bars represent standard error of the estimated intensity. Shown alongside are the nuclear (ρn) and magnetic (ρm) scattering length densities (SLDs) versus thickness of the multilayer

Due to the limitation in providing the maximum applied field at the experimental station, the saturation moments could not be determined. The ZFC data (Fig. 6a) at Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) (virgin state) was found similar to the room temperature data with no net magnetic moment. Absence of any net magnetization is due to the formation of domain states in accordance with the ZFC data in Fig. 1a. The peaks at Qz = 0.038 Å−1 and Qz = 0.109 Å−1 are the 1st order and 3rd Bragg peaks due to the structural periodicity. The 2nd order structural Bragg peak is expected to be significantly reduced since the layer thicknesses are almost equal. For the structural SLDs, the fits yielded the following values: \(\rho _{\mathrm{n}}^{{\mathrm{Tb}}} = 2.5 \times 10^{ - 6}\)Å−2, \(\rho _{\mathrm{n}}^{{\mathrm{Dy}}} = 4.8 \times 10^{ - 6}\)Å−2. We also found an interdiffused layer of around 0.5 nm and 1.0 nm at the Dy/Tb and Tb/Dy interfaces, respectively. This diffusion layer was also evident in the XRR measurements (estimated from the fits to the XRR data in Supplementary Fig. 1). In the case of a random distribution of domain magnetization directions, the dispersion is \(\langle {\mathrm{cos}}^2{\phi} _{\mathrm{A}}\rangle - \langle {\mathrm{cos}}{\phi} _A{\rangle}^2 \,{\ne}\, 0\). Here, ϕA is the angle that the magnetization MFM subtends with the applied field Ha. For a coherent rotation this dispersion is essentially zero. One should not expect here any SF specular signal due to the formation of domain states and no net magnetism, therefore the SF specular intensity visible is attributed purely to the inefficiencies (2–5%) of the optical elements. Note that the so-called leaked SF specular signal is at least two orders of magnitude smaller than the corresponding NSF specular signal. The plot in the inset show the depth profiles in terms of ρn values for the two layers while the ρm value is zero for both.

The nuclear SLDs, thus obtained, were used to fit the FC data (Fig. 6b) at Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) and obtain the magnetic SLD parameters close to the reduced-remanence field of the sub-loop hysteresis. Here again, the fit was started with a simple model of block-like-potentials with average magnetic SLD values to fit the profiles. At this field, the magnetic SLD values obtained from the fits are: \(\rho _{\mathrm{m}}^{{\mathrm{Tb}}} = - 1.4 \times 10^{ - 6}\)Å−2, \(\rho _{\mathrm{m}}^{{\mathrm{Dy}}} = - 1.6 \times 10^{ - 6}\)Å−2. The corresponding magnetic moments are Tb: 1.7 μB/atom and Dy: 1.9 μB/atom. These values are found to be much lower than those known for bulk or values reported earlier (polycrystalline Tb: 2.4 μB/atom6 and polycrystalline Dy: 7.1 μB/atom8) for thin films. This lowering of moment is caused by the fact that the FC process was done not in a saturation field but in an intermediate field. The top layer was found to posses a similar average moment and was associated with a small rotation, oriented 10(±5) away from the applied field direction. This disorientation gave rise to a small SF signal. Such an increase in the SF signal also was reported earlier for another multilayer system39. The difference between the two SF curves is basically due to a difference in the instrumental (polarizer and analyzer) inefficiencies. The plot in the inset show the ρn and ρm values for the two layers as function of thickness.

Similarly, fits to the FC profiles (Fig. 7) at Ha = –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT) were used to obtain the magnetic SLD parameters near the coercive field. Like that for the ZFC measurement at Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT), no true SF signal could be observed at this field, which indicates existence of either domain states or compensated moments40. We have investigated several models representing different possible scenarios in an attempt to simulate the intensity profiles (see the discussion under Model description within Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Table 1 along with Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Out of these, two of the most probable scenarios are discussed below.

Polarized neutron reflectivity (PNR) measurements. Specular neutron reflectivity patterns (solid symbols) along with their best fits (open symbols) as a function of Qz for the non-spin flip (NSF) [R−− (black) and R++ (red)] and spin flip (SF) [R+− (blue) and R−+ (green)] channels measured at a coercive field Ha = −10.0 kOe (–1000 mT) after field cooled (FC) and measured at 10 K for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample. Error bars represent standard error of the estimated intensity. The simulations are done using models considering cases a without any 2π-domain wall and b with 2π-domain walls in both layers of Dy and Tb. Shown alongside are the nuclear (ρn) and magnetic (ρm) scattering length densities (SLDs) versus thickness of the multilayer

In Fig. 7a uniform average magnetizations within both layers were considered. This simple model of block-like-potentials with average magnetic SLD values failed to fit the profiles. The magnetic SLD values which could be obtained were: \(\rho _{\mathrm{m}}^{{\mathrm{Tb}}} = 0.25 \times 10^{ - 6}\)Å−2, \(\rho _{\mathrm{m}}^{{\mathrm{Dy}}} = 0.7 \times 10^{ - 6}\)Å−2. The magnetic SLDs and thereby the corresponding magnetic moments of Tb: 0.3 μB/atom and Dy: 0.8 μB/atom are much lower than in bulk or thin film at saturation. The plot in the inset show the ρn and ρm values versus thickness obtained for the two layers. This drastic lowering of layer magnetizations indicate that they allow 2π-DWs formation within the layers which are stabilized by the in-plane magnetocrystalline anisotropy and exchange coupling at the interfaces.

Furthermore, the magnetization vector of each layer to rotate in-plane (x − y) by an angle ϕA(z) within the multilayer stack is considered, which mimics the existence of 2π-planar DWs within both layers of Dy and Tb6. The scenario is shown in Fig. 7b. The plot in the inset show the ρn and ρm values obtained for the two layers as a function of depth. The larger Dy and Tb moments are confined within a range of a few nanometers from the core of the layers. The planar DWs, which are compressed with an increase in field, are spanned on both sides of the remaining layer while they penetrate on either side of the adjacent layer. Extension of continuous helices, from one layer to the other, is owed to ferromagnetic coupling of the core layers and formation of DWs due to the pinning at interfaces. Within each layer, integration of magnetic moments show little or no variation around the core, whereas around the interfaces the DWs being laid spanned results in a lowering of magnetization. The improved quality of the fit with planar DWs indicates a possibility of our helical modulation model. Since no additional parameters were included other than those mentioned we believe that this is the most logical consequence. Earlier, helical magnetic structures or 2π-DWs have been reported for similar systems2,3,8.

Unlike TM/RE systems, here the layers are neither ferrimagnetically or antiferromagnetically aligned but are ferromagnetically aligned to each other. Signatures of magnetic helices in Dy has have been reported earlier in presence of low fields (0.03–0.1 kOe or 3–10 mT) even at 5 K20,41. The magnetic ordering of helical modulation is sensitive to the cooling history and interface clamping. Thus, one can expect a similar helical phase within Dy and Tb, which are merely reminiscent of the helical ordering realized at higher temperatures. The magnetic stability of the confined helices, demonstrated at –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT), can be attributed not only to the internal field that is created by exchange interaction which stores the magnetic energy but also to the strong anisotropy of the Dy layer (axial: 109–108 erg/cm3; basal-plane: 107–106 erg/cm3). Note the difference in the basal-plane anisotropy constant for Tb (2.4 × 106 erg/cm3) and Dy (7.5 × 106 erg/cm3) at 4 K42. This difference in anisotropy leads to planar DW formation whose energy is modified by exchange interactions. The anisotropy in both Tb and Dy keeps the magnetic moments confined to the basal plane.

We show the specular and off-specular NSF and SF intensity maps in Fig. 8a, b for the multilayer with two different field histories, ZFC and FC and measured at Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) and =–10.0 kOe (–1000 mT), respectively. The scenario for FC condition and measured at –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) also showed a similar intensity map (not shown). The measurement channels shown are the NSF channels I++, I−− and the SF channel I−+. The intensity along the diagonal αi = αf is the specular reflection along the scattering vector Q⊥ and has been discussed in the last section43. Apart from the multilayer Bragg peaks along the specular ridge depicting the periodicities of the multilayer, we could observe off-specular intensities in form of sheets of intensities perpendicular to the specular line (Bragg sheets) emanating across the Bragg peaks (I++ and I−− channels) and intensities near the critical edge and along the Yoneda wings. Additional intensities along the Bragg peaks, parallel to αi,f (diffuse streaks in the I−+ channel) indicate configuration of a domain state for sample magnetization perpendicular to the Ha direction.

Non-spin flip (NSF) and spin flip (SF) intensity maps. NSF and SF intensity maps [I++, I−− and I−+] measured at a Ha = −0.01 kOe (−1 mT) and b −10.0 kOe (−1000 mT) after reo field cooled (ZFC) and field cooled (FC), respectively for the [Dy10/Tb10]10 sample. The black arrows indicate the presence of vertically correlated structural Bragg sheets and the vertically uncorrelated diffuse streaks wherever visible. The color bars encode the scattered intensity on a logarithmic scale. The right hand panels show the distorted wave Born approximation (DWBA) simulated SF intensity maps [I−+] at the respective fields considering small-scale vertically uncorrelated domains as indicated by the arrows. The simulated and measured maps are plotted within a similar dynamical range

Similar intensities of the specular Bragg peaks in the NSF channels indicate that they were measured either at –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) after ZFC (Fig. 8a) or at the coercive field of –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT) after FC (Fig. 8b). A slight imbalance in intensity along the specular ridge at = –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT) between I++ and I−− channels indicate a preferential alignment of the magnetization, which is also in accordance with the fits to the specular profiles shown in Fig. 7b.

In the SF channel, there exists no off-specular Bragg sheet. However, off-specular diffuse streaks exist in the NSF channels as well as in the SF channels, indicating a domain state configuration of the sample magnetization also along and perpendicular to the Ha direction (parallel and perpendicular components). The Bragg sheets in the NSF channels remain similarly intense with a change in the Ha value while the diffuse streaks (indicated by arrows) are more intense in the I++ channel for ZFC and in the I−− channel for FC. Similarly, in the SF channel I−+, it is more intense along αi at –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) as compared to that along αf at = –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT), which obviously indicates that the diffuse streaks are of magnetic origin while the Bragg sheets, which remain similar at both fields, are not of magnetic origin. Such a temperature or field dependence of off-specular SF scattering from vertically correlated domains was reported earlier by Paul et al. in epitaxial Er/Tb system3. Owing to the reciprocity theorem, SF channels intensity maps, I+− and I−+, are interchangeable by a magnetic field directional switch. For a certain field without any change in the field direction, they are supposed to remain asymmetric with respect to the diagonal intensities, i.e., I+− ≠ I−+. Thus, the change in asymmetry of the scattered intensity in the respective SF channel I−+ for ZFC and FC in Fig. 8a, b, accounts for the fact that the spin states of the incoming and outgoing neutron waves are inversely populated indicating that they have been reversed by the field. This interchange of intensity obviously confirms their magnetic origin.

On the one hand, the Bragg sheets occur due to pronounced structural and/or magnetic vertical correlation along the stack of the multilayer. On the other hand, diffuse streaks run parallel to αi,f axes. Due to some instability in the system, one often witnesses fluctuations of the magnetization (ΔϕA) from vertically uncorrelated domains around the mean magnetization in the form of diffuse scattering. Perpendicular fluctuations are characterized by the mean value \(\overline {\sin ^2(\Delta \phi _{\mathrm{A}})}\), which are commonly seen in the SF channels below a saturation field40,43.

Distorted wave Born approximation (DWBA) has been applied in simulating the corresponding SF intensity maps in the SF I−+ channel (Fig. 8a, b). The parameters for the off-specular data simulations follow from the fit parameters obtained from the fitting of the corresponding specular data. Thus the inefficiencies of the polarizer and analyzer are intrinsically incorporated in the simulations. One can see an increase in the off-specular SF intensities near the critical edge in the simulated maps. These are typical signatures of random non-collinear arrangement of small-scale domains with sizes ranging from 1.5 ± 0.5 μm and 0.5 ± 0.5 μm accompanied by fluctuations of magnetization ΔϕA = 4 and 15, for ZFC and FC conditions measured at –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) and –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT), respectively. The domain sizes are typically smaller than the neutron coherence length along the x axis (few microns), i.e., as and when the coherence ellipse covers several domains40,43. The change in asymmetry for ZFC and FC has duely been accounted for in the respective simulations.

Noncollinear configuration of planar spin chain

Theoretically, Popov et al.44 treated in-plane exchange interaction within mean field approximation, the energy of which can be described by a finite size 1D model for N planar classical spins

Here, hA = HA/HEB and h = Ha/HEB, where HEB, HA, and Ha are the effective exchange field, effective uniaxial anisotropy field and external applied field, respectively. A spin on ith side of the chain forms an angle \(\phi _{\mathrm{A}}^i\) perpendicular to the chain axis. A number of collinear ground state and noncollinear equilibrium stable configurations were numerically calculated. Even though the theoretical discussion is meant for epitaxial films9, we could find it relevant for polycrystalline films as well emphasizing the robustness of spin configurations and thereby the generality of results.

A multilayer stack can relax into different equilibrium states depending upon the energy density introduced by an external magnetic field. With removal of the external field, the multilayer typically relaxes into a ground state as all magnetic moments remain aligned and attains a global minimum. However, for an intermediate field, the stack relaxes into a metastable state as the spins remain misoriented with the attainment of a number of local energy minima5,8. In the present context, Fig. 6b represents a scrambled ground state at –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) where all spins are randomly oriented while Fig. 7b represents a state of noncollinear equilibrium configurations at –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT) where spins are appreciably misoriented with respect to the hard axis as expected for an intermediate field.

Supplementary Fig. 8a shows a schematic of the noncollinear spin configurations containing two π-DWs (topologically protected non-trivial structure) so that the overall rotation of the spins along the chain is 2π within the layers \(\left( {\frac{N}{\xi }\, {> }\, 2\pi } \right)\) of Dy and Tb. Alternatively, a combination of π-DW and π-antiDW (topologically unstable trivial structure) of width ξ is possible. It may be noted that PNR alone cannot distinguish between the two configurational states. However, magnetic stability of the 2π-DWs or confined helices at –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT), exemplifies the fact that a non-trivial topological structure cannot be easily destroyed by a field.

In order to reduce the cost of uniaxial anisotropy the spin orientations remain close to an integer multiple of π at the end points of the chain. Due to halved number of nearest neighbors, the spins at the surface/interface (centers of DW nucleation) were shown to be two times less, which reduces the energy \((E_{\mathrm{w}} = 4a\sqrt {J_{{\mathrm{ex}}}K} )\) near the end points by a factor of \(\sqrt 2\). The DW width, which is given by \(\xi = \frac{a}{{2\sqrt \gamma }} \simeq \pi \sqrt {\frac{A}{K}}\), leads to an uneven distribution of spins within an individual layer with relative compression at the interfaces and decompression in the inner layers. Here, \(\gamma = \frac{K}{{J_{{\mathrm{ex}}}}}\) as Jex, a and K are the exchange coupling constant, lattice constant and uniaxial anisotropy constant, respectively. Also, \(J_{{\mathrm{ex}}} = \frac{{aA}}{{2S^2}}\) where A is the exchange stiffness. Assuming the parameter A = 8 × 10−8 erg/cm for Dy and Tb and KDy = 7.5 × 106 erg/cm3 and KTb = 2.4 × 106 erg/cm3, the basal plane DW widths are ξDy ~ 3.2 nm and ξTb ~ 5.7 nm. Thus, a difference in the reduced number of spins at the end points due to unequal ξ along with structural interdiffusion \((= 2.0 \pm 0.5\,{\mathrm{nm}})\) at the interfaces of Dy and Tb layers would contribute to vertically uncorrelated domains when the two layers are stacked as a multilayer.

Based upon the temperature-dependent neutron-scattering intensity, a picture of the spin-glass state coexisting with the helical spin ordering was discussed earlier by Sato et al.45. An interdomain interaction should be pronounced when the competition of two types of modulated spin fluctuation becomes significant, particularly at the interfaces. A frustrated interdomain magnetic interaction would lead to the coexistence of spin-glass-like ordering and helical spin modulation.

Model interpretation of spin-glass as a short-range spin density wave (SDW) has been proposed earlier by Mydosh17. Therefore, magnetic configurations of topologically stable modulated helices can be visualized as a superposition of the double spin spirals or SDW within Dy and Tb with similar propagation wave vector q(=2π/N) and pitch, and separated by a phase factor. A resultant of superposition of two helices represented by the magnetic SLD profile is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8b, for clarity. The number of nodes/anti-nodes (modulation period) in the modulation of the envelope lines forming the double helices, which being commensurate with the chain’s length, determines the number of twists in the chain. Increase in the number of twists increases the helix modulation, which in turn enhances the energy stored in the system4,8.

Discussion

We have demonstrated the realization of magnetic helices in form of 2π–planar DWs in an unprecedented multilayered system involving two hard rare-earth materials (Dy/Tb), instead of a more familiar soft-hard (Fe/Tb or Fe/Dy) combination. Using depth sensitive PNR, DWs have been shown to exist within both Dy and Tb. Since both materials are anisotropically hard and their respective helical and ferromagnetic ordering temperatures are also significantly different in bulk form, it was hardly expected for them to establish exchange coupled helices. Thus, our work realizes a novel state of spin configuration even within such unusual candidates.

The robustness of the helices at an applied field of –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT) ensures their topological stability. The helices within both RE/RE layers are stabilized by the strong in-plane magnetocrystalline anisotropy of the Dy and relatively softer Tb layers induced by the growth process. Exchange bias coupling of around –0.88 kOe (–88 mT) and –0.65 kOe (–65 mT) were revealed in two multilayers with different tDy and tTb thicknesses combinations, which can be owed to the enhanced pinning at spin-frustrated interfaces.

Rigorous magnetic data analysis suggests the existence of superspin-glass type of freezing of weakly interacting disordered spins. Additionally, such SSG type of behavior with TSSG ≃ 206 K, was found to be coexistent with the helical spin configurations. The dynamics in the superspin glass phase and its scaling behavior was further confirmed by TRM measurements. Such a coexistence of SSG and helical phases, is due to the spin-frustrated interdomain magnetic interaction as indicated by polarized off-specular neutron scattering.

We believe, that topological stability for the effective periodicity of the modulation and the internal effective field in the helix, which stores the magnetic energy density, can be interesting for exploiting their applicability in all-spin-based technology.

Methods

Sample preparation

The samples were prepared by DC magnetron sputtering using Si(100) as substrate, of compositions [Dy10/Tb10]10: [Dy(10.0 nm)/Tb(10.0 nm)] × N = 10 and [Dy5/Tb5]10: [Dy(5.0 nm)/Tb(5.0 nm)] × N = 10. Two different multilayers, with different thicknesses of tDy and tTb, were prepared in order to investigate the effect of changing Dy and Tb magnetization. Thicknesses of the layers were carefully chosen such that the volume anisotropy is confined to the film plane overcoming the surface anisotropy.

The substrates were single crystalline Si wafers of 20 × 20 mm2, which were used after cleaning them in isopropyl alcohol. The targets were disks of 2 inch diameter and 0.125 inch thickness with a purity of 99.9%. They were bonded to a copper backing plate. The targets were cleaned by pre-sputtering for 10–15 min in Ar atmosphere. The deposition rates were about 0.215 nm/s for Tb and 0.282 nm/s for Dy and were precalibrated. During deposition, the Ar pressures in the magnetron sputtering chamber were 3.9 × 10−3 mbar for Tb and 2.9 × 10−3 mbar for Dy and the base pressure was 1.5 × 10−8 mbar. The magnetron sputtered samples were expected to grow with a high degree of crystallographic orientation (texture) and in-plane easy axis as confirmed earlier from the XRD patterns (see Supplementary Fig. 1)8.

X-ray characterization

XRR and XRD measurements were performed on an Empyrean diffractometer from PANalytical which provides information on the structure, thickness and interface roughness of the individual layers (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The individual layers and multilayers show broad polycrystalline peaks when investigated by XRD as observed earlier for similarly grown films46. X-ray contrast between Dy and Tb is very poor due to their adjacent atomic numbers, hence a multilayer structure could not be properly studied using XRR.

Magnetometry

Conventional in-plane magnetization measurements were performed at various temperatures and fields using a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) from Quantum Design (MPMS-XL). Conventional AC field susceptibility measurements were acquired at various temperatures and frequencies using a physical property measurement system (PPMS) from Quantum Design.

Polarized neutron scattering

PNR measurements were performed at the reflectometer MARIA at MLZ, Germany47. In-plane magnetic fields of 10 kOe (1000 mT) and 0 Oe (0 mT) were used before the samples were cooled to 10 K separately in a cryostat and measured at applied fields Ha = –0.01 kOe (–1 mT) and –10.0 kOe (–1000 mT). From the neutron polarization analysis we resolve different components of the magnetization within the film plane. The saturation field of approximately 50.0 kOe of the system exceeded the experimentally available field of 10.0 kOe (1000 mT) at MARIA. The SLDs of a specimen are given by the nuclear (ρn) and magnetic (ρm) components. Four different cross sections were measured, namely non-spin flip (NSF) scattering: (ρn ± ρm cos ϕA) represented by R++ and R−− and spin flip (SF) scattering: (\(\rho _m^2\) sin2 ϕA) represented by R+− and R−+. Here, + and − signs are used to distinguish the intensity contributions R representing a polarization component parallel or anti-parallel to the guiding field, respectively. The angle ϕA is between the magnetization MFM and the applied field Ha. The spin dependent NSF reflectivities are given by

while the SF reflectivities are given by

Here, R+, R− are the Fresnel reflection amplitudes for neutron polarizations parallel and anti-parallel to magnetic induction of the sample. The amplitudes are given by the eigenvalues of the reflectance matrix which is diagonal at ϕA = 0, π. The NSF reflectivities involve squares of the combinations of (1 − cosϕA) and (1 + cosϕA) terms. Thus, within the one dimensional analysis of the polarization vector it is not possible to discriminate the tilt angle ϕA from (ϕA + π) or the rotational sense of magnetization40. Note that by convention when the critical angle for R++ precedes R−− along Qz, the ρm value is regarded as negative.

Following the scattering geometry the momentum transfer vector Q can be written in terms of its various components:

where the incident wave-vector defined by ki, makes an angle αi with respect to the x axis while the scattered wave-vector kf makes angle αf in the x–z plane and also χ in the x–y plane (relevant for diffuse scattering) and λ is the wavelength (here λ = 4.5 Å). The sample is located in the (x, y) plane. The Qy element can be ignored in this geometry as we do not resolve the intensities, but integrate, along that axis40.

Figure 5a shows a sketch of the scattering geometry. The projection of the parallel component of magnetization onto the neutron polarization axis (y axis) is proportional to 〈cosϕA〉, while the projection of the component perpendicular with respect to the polarization axis onto the x axis is proportional to \(\langle {\mathrm{sin}}^2\phi _{\mathrm{A}}\rangle\). Different length scales \(\xi = \frac{{2\pi }}{Q}\) ranging from nm to μm can be accessed by using different scattering geometries in most practical cases.

The neutron coherence lengths48 can be estimated from the uncertainties in the reciprocal space with the help of instrument resolutions. Thereby lx (along Qx) and ly (along Qy), which are contributions to the coherence length l|| at the sample surface, turn out to be few μm and few å ngströms, respectively40. For domains (magnetic inhomogeneities) or roughness (nuclear inhomogeneities) larger than l||, the intensities reflected from different domains superimpose incoherently in the specular beam. In Fig. 5b, we have shown that if the domains are smaller than l||, then the neutron wave is scattered in specular and off-specular directions. If the domain correlations are larger \((\xi _\parallel \,{> }\, l_\parallel )\), then each domain reflect independently, which are then averaged over all possible domain orientations. Thus, the mean value of the orientation 〈cosϕA〉 can be obtained. The off-specular scattered intensity thus can be coherent (for periodic structure) or diffuse (for random distribution) with a spatial distribution of ΔϕA. This means that the domain magnetization is randomly tilted by angle ΔϕA with respect to the mean value averaged over the coherence volume along the perpendicular (〈sin2ΔϕA〉) and parallel directions (〈cosΔϕA〉).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source codes used for neutron scattering fitting/simulation are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dumesnil, K. et al. Magnetic structure of dysprosium in epitaxial Dy films and in Dy/Er superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 54, 6407 (1996).

Satchell, N. et al. Probing the spiral magnetic phase in 6 nm textured erbium using polarised neutron reflectometry. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 055801 (2017).

Paul, A. Stiffness in vortex-like structures due to chirality-domains within a coupled helical rare-earth superlattice. Sci. Rep. 6, 19315 (2016).

Vedmedenko, E. Y. & Altwein, D. Topologically protected magnetic helix for all-spin-based applications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 017206 (2014).

Dzemiantsova, L. V., Meier, G. & Röhlsberger, R. Stabilization of magnetic helix in exchange-coupled thin films. Sci. Rep. 5, 16153 (2015).

Paul, A., Mukherjee, S., Kreuzpaintner, W. & Böni, P. Exchange-bias-like coupling in a ferrimagnetic multilayer Fe/Tb. Phys. Rev. B 89, 144415 (2014).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Exchange-bias-like coupling in a Cu-diluted-Fe/Tb multilayer. Phys. Rev. B 91, 104419 (2015).

Fust, S. et al. Realizing topological stability of magnetic helices in exchange-coupled multilayers for all-spin-based system. Sci. Rep. 6, 33986 (2016).

Majkrzak, C. F. et al. Magnetic rare-earth superlattices. J. Appl. Phys. 63, 3447 (1988).

Borchers, J. et al. Structural and magnetic properties of Er thin films and Er/Y superlattices. II. Modification of the commensurate spin states. Phys. Rev. B 44, 11814 (1991).

Mangin, S., Marchal, C. & Barbara, B. Evidence of exchange-bias-like Phenomenon in GdFe/TbFe/GdFe domain wall junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4336 (1999).

Mangin, S., Montaigne, F. & Schuhl, A. Interface domain wall and exchange bias phenomena in ferrimagnetic/ferrimagnetic bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 68, 140404 (2003).

Higgs, T. D. C. et al. Magnetic coupling at rare earth ferromagnet/transition metal ferromagnet interfaces: a comprehensive study of Gd/Ni. Sci. Rep. 6, 30092 (2016).

Dieke, G. H. Spectra and Energy Levels of Rare-earth Ions in Crystals. (Academic Press Inc., New York, 1967).

Nakamae, S. et al. Superspin glass aging behavior in textured and nontextured frozen ferrofluid. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 09E135 (2010).

Mukherjee, S., Ranganathan, R., Anilkumar, P. S. & Joy, P. A. Static and dynamic response of cluster glass in La0.5Sr0.5CoO3. Phys. Rev. 54, 9267 (1996).

Mydosh, J. A. Spin glasses: redux: an updated experimental/materials survey. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 052501 (2015).

Almeida, J. R. Lde & Thouless, D. J. Stability of the Sherrington-Kirkpatrick solution of a spin glass model. J. Phys. A 11, 983 (1978).

Gabold, H. et al. Structural and magnetic properties of cobalt iron disulfide (CoxFe1−xS2) nanocrystals. Sci. Rep. 8, 4835 (2018).

Herz, R. & Kronmüller, H. Field-induced magnetic phase transitions in dysprosium. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 9, 273 (1978).

Wakabayashi, N., Cable, J. & Robertson, J. Magnetic structures of Dy in applied fields. Phys. B 241, 517 (1997).

Mougin, A., Dufour, C., Dumesnil, K., Mangin, Ph & Marchal, G. Stabilisation of the helical phase in epitaxial Y/DyxTb1−x/Y trilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 165, 168 (1997).

Paul, A., Paul, N., Müller-Buschbaum, P., Bauer, A. & Böni, P. Superparamagnetic regular nanopillar-like structures studied by grazing-incidence X-ray scattering: effect of vertical correlation. J. Appl. Cryst. 47, 1065–1076 (2014).

Chandra, S. et al. Spin dynamics and criteria for onset of exchange bias in superspin glass Fe/γ-Fe2O3 core-shell nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. 86, 014426 (2012).

Néel, L. Théorie du traînage magnétique des ferromagnétiques en grains fins avec application aux terres cuites. Ann. Geophys. (C. N. R. S.) 5, 99 (1949).

Néel, L. Influence des fluctuations thermiques sur laimantation de grains ferromagnetiques tres fins. Acad. Sci. 228, 664 (1949).

Vogel, H. The law of the relation between the viscosity of liquids and the temperature. Phys. Z. 22, 645 (1921).

Fulcher, G. S. Analysis of recent measurements of the viscosity of glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 8, 339 (1925).

Halperin, B. I. & Hohenberg, P. C. Scaling laws for dynamic critical phenomena. Phys. Rev. 177, 952 (1969).

Dormann, J. L., Bessais, L. & Fiorani, D. A dynamic study of small interacting particles: superparamagnetic model and spin-glass laws. J. Phys. C: Solid St. Phys. 21, 2015 (1988).

Félix, L. León et al. Structural and magnetic properties of core-shell Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 7, 41732 (2017).

Toro, J. A. De et al. Spin-glass-like behavior in mechanically alloyed nanocrystalline Fe-Al-Cu. Phys. Rev. 60, 12918 (1999).

Jönsson, P. E., Yoshino, H., Mamiya, H. & Takayama, H. Absence of strong rejuvenation in a superspin glass. Phys. Rev. B 71, 104404 (2005).

Hiroi, K., Komatsu, K. & Sato, T. Superspin glass originating from dipolar interaction with controlled interparticle distance among γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles with silica shells. Phys. Rev. B 83, 224423 (2011).

Zelenáková, A., Zelenák, V., Michalík, Ŝ., Kovác, J. & Meisel, M. W. Phys. Rev. B 89, 104417 (2014).

Mydosh, J. A. Spin Glasses: An Experimental Introduction. (Taylor & Francis, London, 1993).

Mathieu, R., Jönsson, P., Nam, D. N. H. & Nordblad, P. Memory and superposition in a spin glass. Phys. Rev. B 63, 092401 (2001).

Parker, D. et al. Spin-glass behavior in an interacting γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticle system. Phys. Rev. B 77, 104428 (2008).

Paul, A., Krist, Th, Teichert, A. & Steitz, R. Specular and off-specularscattering with polarization and polarization analysis on reflectometer V6 at BERII, HZB. Phys. B 406, 1598 (2011).

Paul, A. Low-angle polarized neutron and x-ray scattering from magnetic nanolayers and nanostructures. Springer Tracts in Modern Physics 273, Springer-Verlag (2017).

Yu, J. Exploring the magnetic phases in dysprosium by neutron scattering techniques, PhD thesis (University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 2014).

Rhyne, J. J. & Clark, A. E. Magnetic anisotropy of terbium and dysprosium. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 1379 (1967).

Paul, A., Teichert, A., Krist, Th & Steitz, R. Substrate–stress induced magnetic and nonmagnetic structural correlations in Fe/Si multilayers. J. Appl. Cryst. 48, 1023 (2015).

Popov, A. P., Rettori, A. & Gloria, M. Spectrum of noncollinear metastable configurations of a finite-size discrete planar spin chain with a collinear ferromagnetic ground state. Phys. Rev. B 92, 024414 (2015).

Sato, T., Ando, T., Oku, T. & Furusaka, M. Helical-spin-glass reentrant transition in itinerant electron type magnet Cr1−xMnxGe. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 140, 1785 (1995).

Scheunert, G. et al. Improved magnetization in sputtered dysprosium thin films. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 46, 152001 (2013).

Heinz Maier-Leibnitz, Zentrum et al. MARIA: Magnetic reffectometer with high incident angle. J. Large-scale Res. Facilities 1, (A8 (2015).

Majkrzak, C. F. et al. Determination of the effective transverse coherence of the neutron wave packet as employed in reflectivity investigations of condensed-matter structures. I. Measurements. Phys. Rev. A 89, 33851 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank M. Opel for some SQUID measurements. Thanks are also due to P. Böni for his fruitful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Technische Universität München within the Open Access Publishing Funding Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. assisted T.B. in sample preparation. N.P. and A.P. did the X-ray measurements. T.B. and J.Y. did the DC and AC magnetization measurements while A.P. did the TRM measurements. J.Y. and S.M. did the PNR measurements from a beamtime proposal of A.P. All authors reviewed the manuscript. A.P. conceived and designed the work, analyzed all datasets, coordinated the work, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, J., Baldauf, T., Mattauch, S. et al. Topologically stable helices in exchange coupled rare-earth/rare-earth multilayer with superspin-glass like ordering. Commun Phys 2, 114 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0210-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-019-0210-0

This article is cited by

-

Non-collinear magnetic configuration mediated exchange coupling at the interface of antiferromagnet and rare-earth nanolayers

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Surface distortion of Fe dot-decorated TiO2 nanotubular templates using time-of-flight grazing incidence small angle scattering

Scientific Reports (2020)