Abstract

Valley degree of freedom, associated with the valley topological phase, has propelled the advancement of the elastic waveguide by offering immunity to backscattering against bending and weak perturbations. Despite many attempts to manipulate the wave path and working frequency of the waveguide, internal characteristic of an elastic wave such as rich polarization has not yet been utilized with valley topological phases. Here, we introduce the rich polarization into the valley degree of freedom, to achieve topologically protected in-plane and out-of-plane mode separation of an elastic wave. Accidental degeneracy proves its real worth of decoupling the in-plane and out-of-plane polarized valley Hall phases. We further demonstrate independent and simultaneous control of in-plane and out-of-plane waves, with intact topological protection. The presenting procedure for designing the topologically protected wave separation based on accidental degeneracy will widen the valley topological physics in view of both generation mechanism and application areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of the topological phase has led to a new paradigm for information and energy transfer1,2. On the boundary of two materials having distinct topological phases, the wave propagates unidirectionally immune to structural imperfections, defects, and sharp angles. Fueled by this unparalleled transmission characteristic, the concept of topological phase has been extended from condensed matter physics3,4,5,6,7 to classical waves including photonic wave8,9,10,11,12, acoustic wave13,14,15,16,17,18,19, and elastic wave20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Especially, an extension of valley topological phase to classical waves10,16,19,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 is noticeable because neither external force nor complex geometry is required on its formation: they are necessary for other classes of topological phase, quantum Hall phase8,14,20 or quantum spin Hall phase9,15,21,22,23, to break time-reversal symmetry or to form pseudo-spin, respectively. One pre-requested condition for the valley Hall phase to emerge in classical waves is the Dirac degeneracy, the double degeneracy with linear dispersions34. Fortunately, the Dirac degeneracy appears deterministically for some point group symmetry, for instance, C6 or C3v of wavevector k35 on hexagonal-lattice: such degeneracy is named deterministic Dirac degeneracy. Valley Hall phase emerges when Dirac degeneracy is lifted by some perturbations and inequivalent valleys emerge. Because the perturbations require an only-single degree of freedom, the structure does not need to be complex24. Thanks to the deterministic Dirac degeneracy, the valley Hall phase in classical waves is often generated by breaking the point group symmetry, mostly by breaking the space-inversion symmetry10,19,24,26,28,29,30,31 or mirror symmetry16,17,18,25, after observing the deterministic Dirac degeneracy at valleys.

Elastic wave, phononic fluctuation in a solid medium, has some unique characteristics exhibiting distinguished applications related to the waveguide. Because elastic wave speed is significantly slower than the photonic wave, elastic wave devices can be used to manipulate the photonic information compactly with phonon–photon coupling36. The pervasiveness of elastic vibration emphasizes the elastic wave routing and focusing for the energy harvesting37. One other peculiar characteristic of the elastic wave is that it has both longitudinal and transverse wave components, namely, rich polarization, while acoustic wave has only longitudinal one and photonic wave has only transverse one. These two components of elastic wave have been utilized independently in both engineering and science owing to their distinct physics, although hybridization and conversion between variously polarized components of elastic wave are quite common. Accordingly, filtering out a singly polarized wave or splitting the elastic waves according to their polarization has been one of the crucial questions in controlling the elastic wave, and various phononic crystals (PCs) have been designed to solve this problem based on the polarization bandgap38,39, wave phase difference40, and tensor engineering41.

Elastic PCs possessing valley Hall phase also have been limited to deal with only one polarized component of elastic wave that the lifted Dirac degeneracy belongs to, in the formation of the valley Hall phase. Mostly in two-dimensional PCs, the valley topological phase acts only on either in-plane polarized (IPP) wave26,27,28,29 or out-of-plane polarized (OPP) wave24,25,30,31 leaving the other one as redundancy. However, because IPP and OPP waves have different physics, Dirac degeneracy of IPP and OPP waves can be set to overlap so that IPP and OPP valley Hall phases are generated simultaneously in the same frequency. This gives the valley Hall phase the potential to be utilized for the mode separation of elastic waves and may serve the unparalleled robustness in the elastic wave mode separation, named topologically protected separation.

The challenge on the separation exists obviously, regarding the strategy generating valley Hall phase. A common strategy utilizing the deterministic Dirac degeneracy cannot break the link between IPP and OPP valley Hall phases since the degeneracy depends on the point group symmetry without distinguishing IPP and OPP waves. Accidental Dirac degeneracy, a complementary set of the deterministic Dirac degeneracy, only has the possibility to differentiate IPP and OPP valley Hall phases. Though only a few topological PCs were reported utilizing accidental degeneracy, and they are also limited to deal only one polarized component27. Moreover, sufficient condition for constructing accidental degeneracy has not been explored so far.

Here, we demonstrate the topologically protected elastic wave separation into IPP and OPP waves with two-dimensional PCs possessing superposed valley Hall phases, i.e., superposition of IPP and OPP valley Hall phases, based on accidental Dirac degeneracy. Sufficient conditions for constructing accidental degeneracy and strategies exploiting the degeneracy for multiply polarized waves in the identical medium are found and utilized for the separation of IPP and OPP topological edge states. First, we design the PCs with three tunable geometric parameters, so that the set of parameters establishing the deterministic Dirac degeneracy is connected in the parameter space. Then, the continuity of Bloch frequency with respect to the geometric parameters guarantees the existence of accidental degeneracy. This accidental degeneracy together with the following topological phase diagram reveals the separation of IPP and OPP phases, so all possible superposed topological phases. We find a pair of PCs possessing the same bandgap by Jaccard index in this setup for the topologically protected separation. A topologically protected edge state with any polarization can be created utilizing the pair of PCs and their valley pairs. Using these edge states, topologically protected independent routing of IPP and OPP waves is demonstrated as well as the topologically protected separation into IPP and OPP waves.

Results

Design of phononic crystals with three tunable parameters

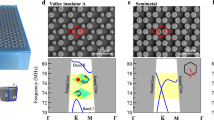

The designed hexagonal-lattice PC is a truss-like structure with periodic hexagonal-like holes as shown in Fig. 1a, b. The substrate is a 2 mm thick linear elastic plate with the properties of conventional acrylic plastic (method), and the size of the unit cell is l = 10 mm with a thickness of the ligand wall t = 1.5 mm. Figure 1c, d shows the schematic representation of the unit cell without and with the perturbation, respectively. Two different-sized hemicylinders are attached to the hexagonal cell walls alternatively so that C3 symmetry is preserved throughout the PC. Three tunable geometric parameters exist given as c, b1/B1, and b2/B2. c represents the nondimensionalized radius difference with the radiuses of the hemicylinders r1 = (1 + c)r0 and r2 = (1 − c)r0. b1 and b2 represent the respective displacement of the hemicylinders displaced from the center of the hexagonal cell walls, while B1 and B2 are the maximum magnitudes that b1 and b2 can attain, respectively. For full restriction of the parameters b1 and b2, see Supplementary Note 1 with Supplementary Fig. 1. The value of c is restricted to reside in [0,1], and the values of (b1/B1, b2/B2) is restricted to range in |b1/B1| + |b2/B2| ≤ 1 for convenience. Among three parameters, only the locations of two hemicylinders (b1/B1, b2/B2) are regarded as variables for perturbation, and the radius difference c is usually fixed.

a, b Perspective view (a) and top view (b) of a two-dimensional phononic crystal with periodic hexagonal-like holes made of the linear elastic material having properties of acrylic plastic. Black solid hexagon is a primitive cell with side length l = 10 mm, and a1 and a2 are lattice vectors of the crystal. p and q indicate two inequivalent triangular sublattices. c, d Detailed schematics of the primitive cell without (c) and with (d) the perturbations, nonzero (b1/B1, b2/B2). Three tunable parameters, nondimensionalized radius difference c and perturbation variables b1/B1 and b2/B2, are green-colored. e Energy band structures of the phononic crystal for various geometric parameters. The polarization factor of each state is indicated by color, blue for polarization factor 0 (purely in-plane polarized state) and red for polarization factor 1 (purely out-of-plane polarized state). The extended version of (e) is in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Since the structure preserves the horizontal mirror plane (σh) symmetry or is equivalently symmetric with respect to its midplane, symmetric and antisymmetric waves corresponding to IPP and OPP waves, respectively, are preserved and differentiated. In the band diagram, polarization factor p42, defined to be 0 for purely IPP wave and 1 for purely OPP wave (method), verifies this correspondence on the frequency of interest (around bandgap or Dirac degeneracy) by having a value lower than 0.01 (IPP, blue) or higher than 0.86 (OPP, red) only as shown in Fig. 1e. The Dirac degeneracy appears when (c, b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0, 0, 0), (0, 0.3, 0.3), and (0.25, 0, 0) for both IPP and OPP waves, while the bandgap appears when (c, b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0.25, 0.3, 0.3). Dirac frequencies for the IPP and OPP wave band are adjacent when the Dirac degeneracies appear owing to the appropriate choice of the thickness dimension of the two-dimensional PCs. As the thickness changes, only OPP band frequency varies, but IPP band frequency does not change as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Dirac degeneracies that appeared in Fig. 1e reveals to be the deterministic Dirac degeneracy protected by some point group symmetry of wavevector k, as follows. When the PC is unperturbed [(b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0,0)], the energy band features the deterministic Dirac dispersion at both valleys as a result of C3v symmetry35 (mirror symmetry as well as C3 symmetry) regardless of the value of c. Contrastively, when the PC is perturbed [(b1/B1, b2/B2) ≠ (0,0)], the mirror symmetry breaks and only C3 symmetry is intact unless c is not 0 nor 1, eliminating the deterministic Dirac degeneracy. If c is 0 or 1, deterministic Dirac degeneracy can appear even if the PC has nonzero perturbations (b1/B1, b2/B2). For the PC with c = 0, the radiuses of the hemicylinders are all the same, so the energy band features deterministic Dirac degeneracy at both valleys if b1/B1 = b2/B2 as a result of C6 symmetry35. When c = 1, the Dirac dispersion appears when b1/B1 = 0 regardless of the value b2/B2, since the hemicylinder with radius r2 vanishes (r2 = 0). Supplementary Fig. 3, which is the extended version of Fig. 1e, shows the band diagrams for all these deterministic Dirac degeneracies, together with the bandgaps or accidental degeneracies in the case when there is no point group symmetry generating deterministic Dirac degeneracy.

Accidental Dirac degeneracy from deterministic Dirac degeneracy

We had found all PCs featuring the deterministic Dirac degeneracy. At least one among three conditions must be satisfied for the degeneracy: (I) 0 < c < 1 and b1/B1 = b2/B2 = 0; (II) c = 0 and b1/B1 = b2/B2; and (III) c = 1 and b1/B1 = 0 (Fig. 2a). By merging these three conditions in parametric space (c, b1/B1, b2/B2), a set of all parameters enabling the deterministic Dirac degeneracy is revealed to be a connected set, PDD (Deterministic Dirac degeneracy), as shown in Fig. 2b. This connectedness property is important because it ensures that the components of all deterministic Dirac degeneracies are identical regardless of the parameter value (c, b1/B1, b2/B2) for each IPP wave and OPP wave.

a Three conditions [(I), (II), and (III)] and associated schematics of primitive cells individually guaranteeing the deterministic Dirac degeneracy at K or K′ for the phononic crystals (PCs). b Parameters (solid violet lines) of the PCs satisfying conditions (I), (II), or (III), or equivalently, having deterministic Dirac degeneracy at K or K′ in the restricted parameter space (volume enclosed by gray solid lines). PDD indicates the set of all such parameters. The complete parameter space is described in Supplementary Note 1. c Energy distributions and displacement fields of a primitive cell of the PC with parameter (0, 0, 0) at the in-plane polarized (IPP) and out-of-plane polarized (OPP) Dirac degeneracies at K point. Arrows on the energy distribution, blue for IPP, and red for OPP wave show the rotation direction of the motion. Four displacement fields taken at one-third of a period interval show the time-varying motion of the degenerated state; top view presents for IPP states and perspective view presents present for OPP states, and black arrow in OPP displacement field points to the displacement maxima. The black circle and arrow associated with each displacement field show the direction of the motion as well as the phase step. Characters (p− or q+) and triangular symbols are a shorthand representation of the state; moving sublattices (location of moving sublattices) and signs (fill) indicating the rotation direction are used for characters (symbols), and colored blue for IPP and red for OPP state.

To reveal the components of deterministic Dirac degeneracy, two degenerated states at valley K of the unperturbed PC [(c, b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0, 0, 0)] are depicted for each IPP and OPP waves in Fig. 2c. In every state, one sublattice between p and q moves while the other is still, as observed in kinetic energy distribution. The four sequential displacement profiles taken at one-third of a period intervals reveal the time-varying motion of the states. For IPP degenerated states, each moving sublattice rotates circularly16, while for OPP degenerated states, moving sublattice shows gyro motion25. The direction of the gyro or circular rotation are opposite between two degenerated states for both IPP and OPP waves, proving that two degenerated states have opposite chirality25. For the notation (symbol), moving sublattice p/q (triangle/inverted triangle) and the sign indicating the chirality ± (filled/unfilled) of the motion are used16, and colored to indicate whether it belongs to IPP wave (blue) or OPP wave (red). Following this notation (symbol) rule, states p− (triangle unfilled) and q+ (inverted triangle filled) reveals as the components of deterministic Dirac degeneracy, for both IPP and OPP waves. The degenerated states at valley K′ also can be deduced from that of valley K owing to the preserved time-reversal symmetry.

The states p− and q+ for both IPP and OPP waves are preserved even when the deterministic Dirac degeneracy breaks by a slight change of b1/B1 or b2/B2, owing to the intact C3 symmetry11. Accordingly, as long as the parameter (c, b1/B1, b2/B2) of the PC is in the neighborhood of PDD, the PC must have states p− and q+ on band-edge frequencies at valley K, for both IPP and OPP waves. We consider the difference of the frequencies between states p− and q+,

in the neighborhood of PDD to verify the existence of accidental degeneracy whether for IPP wave or OPP wave. Δω must be continuous with respect to the geometric parameters (c, b1/B1, b2/B2) with its image covering both some positive and negative values, so there must be a surface including PDD in the parameter space which satisfies Δω = 0 (Supplementary Note 2). Thus, nonzero perturbations (b1/B1, b2/B2) in the vicinity of (0,0) which allow the PC to have the Dirac degeneracy at valleys always exist for any c between 0 and 1, verifying the existence of accidental Dirac degeneracy for all c between 0 and 1.

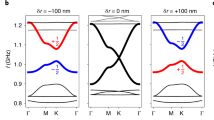

Topological phase diagram with superposed valley hall phase

The PC with lifted degeneracy or bandgap, generated by a slight change of (b1/B1, b2/B2) from the PC possessing Dirac degeneracy, turns out to have a nontrivial valley topological phase owing to its valley pseudospins named p− and q+ states. The frequency order of the split degenerated-states (a sign of Δω) directly discloses the valley Hall phase16, whereas, in the strict sense, it is nontrivial valley Chern number \(C_K^V\) revealing the valley Hall phase. Two valley Hall phases may arise for each IPP and OPP wave as shown in Fig. 3a: IPP phase i0 for Δω < 0 (or \(C_K^V\) = 0.5) and i1 for 0 < Δω (or \(C_K^V\) = −0.5); and OPP phase o0 for 0 < Δω (or \(C_K^V\) = 0.5) and o1 for Δω < 0 (or \(C_K^V\) = −0.5), when the intervalley mixing is neglected. Correspondence between the sign of Δω and the ideal valley Chern number is confirmed by numerical calculation of the valley Chern number for given Δω as shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 9. Four topological phases may appear when IPP phase and OPP phase are superposed: i0o0, i0o1, i1o0, and i1o1.

a In-plane polarized (IPP), out-of-plane polarized (OPP), and superposed valley Hall phase of the phononic crystal (PC). Frequency order between p− and q+ states and ideal valley Chern numbers at valley K linked to each IPP or OPP phase are denoted. Different colors assigned to each valley Hall phases are shown, for example, yellow for the phase i0o0. b Superposed phase diagram of PCs with c = 0 and restricted perturbation b1/B1 + b2/B2 = 0.6. Blue and red solid lines represent the IPP and OPP band-edge frequencies at point K, and symbols on the lines represent the Bloch states. Insets show the energy distributions of the Bloch states at (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0.1, 0.5) (empty star) and (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0.5, 0.1) (filled star). c Superposed phase diagram of PCs with c = 0. A solid violet line indicates the deterministic Dirac degeneracy or phase transition line. The Black dashed line indicates the restricted perturbations used in (b). d IPP, OPP, and superposed phase diagram of PCs with c = 0 and 1. Blue (red) lines and arrows in IPP (OPP) phase diagram represents the phase transition line and direction of the phase transition line at origin (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0, 0), respectively. A superposed phase diagram is nothing but the superposition of IPP and OPP phase diagram; the violet line is a superposition of blue and red lines. e IPP, OPP, and superposed phase diagram of PCs with c = 0.25. All superposed phases appear, different from the diagram of (d) c = 0 and 1.

Before proceeding to the superposed topological phase by accidental degeneracy, to expose the superposed phase and its transition by deterministic Dirac degeneracy, the Bloch frequency with Bloch state at valley K is plotted for the PC with c = 0, varying the perturbation variables restricted on the line b1/B1+b2/B2 = 0.6 in Fig. 3b. Topological phase transition takes place on the deterministic Dirac degeneracy or at b1/B1 = b2/B2 = 0.3 for both IPP and OPP waves. From the sign of Δω for IPP and OPP waves, the topological phase is disclosed to be i0 and o0 for b1/B1 < b2/B2 and i1 and o1 for b2/B2 < b1/B1. For clarity, Bloch wave functions and Berry curvatures around valley K for PCs with (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0.1,0.5) and (0.5,0.1) are drawn in Supplementary Fig. 4. Dirac frequencies of IPP and OPP wave is almost the same at the degeneracy b1/B1 = b2/B2 = 0.3, and the bandgap width | Δω | gets larger as the |b1/B1−b2/B2 | gets larger. Thus, for some PCs with large |b1/B1−b2/B2 | , for example for PCs with (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0.1,0.5) and (0.5,0.1), the bandgap for IPP wave and OPP wave overlaps significantly and superposed valley Hall phase is generated. With these two PCs, a topologically protected edge state carrying both IPP and OPP waves can be generated as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 and explained in Supplementary Note 3. Actually, such PC pairs with superposed topological phase is rare and hard to find even with the deterministic Dirac degeneracy, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6 and explained in Supplementary Note 3.

The topological phase of the PC for general perturbations (b1/B1, b2/B2) with fixed c is visualized by the topological phase diagram. As shown in Fig. 3c, when c is fixed to be 0, topological phase transition takes place only on the deterministic degeneracy line b1/B1 = b2/B2, so the topological phase boundary for IPP wave and OPP wave matches perfectly. Consequently, IPP phase i0(i1) and OPP phase o0(o1) are inherently tied in the PC with c = 0, so only i0o0 and i1o1 are allowed to appear among four possible superposed topological phases. Contrastively, in the PC with c = 1 in which deterministic degeneracy line exists as well, the topological phase diagram shows that the IPP phase i0(i1) and OPP phase o1(o0) are inherently tied, so only i0o1 and i1o0 are allowed to appear (Fig. 3d). In any case, the deterministic Dirac degeneracy indeed turns out to be inadequate for our purpose of decoupling the IPP and OPP edge states.

We already proved the existence of accidental Dirac degeneracy for all of c between 0 and 1. To figure out the formation nature of the accidental Dirac degeneracy line, the topological phase diagram for IPP wave and OPP wave independently presents for the recognized cases c = 0 and 1 in Fig. 3d. In each IPP(OPP) topological phase diagram, we define a continuous function of c, θIPP = θIPP(c) (θOPP = θOPP(c)), as the tangent angle to degeneracy line at (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0,0) having i1(o1) phase on its right side. Because the difference between θIPP and θOPP,

is 0 (mod 2π) for c = 0, and π (mod 2π) for c = 1, there must be some c0 between 0 and 1 satisfying

so that all possible superposed topological phases, i0o0, i1o1, i0o1, and i1o0, emerge on the neighborhood of (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0,0) with the equal portions. Figure 3e shows the topological phase diagram for c = 0.25, in which all superposed topological phase emerges with nearly the same proportion. θIPP and θOPP with respect to c and topological phase diagram for various c is drawn in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Topologically protected edge state from accidental Dirac degeneracy

For two topological PCs to form the topologically protected edge state, they need to have not only different topological phases, but also the common bandgap frequencies. Specially, since we deal with IPP and OPP waves simultaneously, four bandgaps should share the same frequency range: each IPP and OPP wave bandgap for both the two PCs. Jaccard index J, the index gauging the similarity between two sets, is utilized here to describe the correspondence between bandgaps, while it attains 0 if two bandgaps have no intersection, and 1 if two bandgaps coincide (Supplementary Note 3). Figure 4b shows the Jaccard index between IPP and OPP bandgaps with respect to perturbation variables b1/B1 and b2/B2 for the PCs with c = 0.25, whose topological phase diagram is shown in Fig. 4a. Since the intersection of bandgaps vanishes on the degeneracy lines, the Jaccard index is 0 on both IPP and OPP degeneracy lines and gets larger as the perturbation goes farther from the degeneracy lines. Consequently, the Jaccard index has a significantly large value following two crossing lines L1 and L2 approximately, and the eigenfrequencies following these lines clearly show the significant correspondence between IPP and OPP bandgaps (Supplementary Fig. 8). Next, to find two PCs with different topological phases and common bandgap, the Jaccard index is calculated again between intersected bandgaps along L1 and L2 lines (Fig. 4c). In Fig. 4c, every point with a significantly large Jaccard index represents two topological PCs, candidates for generating the topologically protected edge states with superposed topological phases.

a Feasible PCs S00, S10, S01, and S11 in the superposed phase diagram with c = 0.25. S00, S10, S01, and S11 are named after their superposed topological phase. Black dashed triangles have vertices S10, S01, and S11, and used in (e). b Jaccard index between in-plane polarized (IPP) bandgap and out-of-plane polarized (OPP) bandgap of the PCs with c = 0.25. Line L1 and L2 indicates perturbation sets possessing large Jaccard index approximately, where L1: 3(b1/B1) − 5(b2/B2) = 0 and L2: 7(b1/B1) + 3(b2/B2) = 0. c Jaccard index between intersected bandgaps (intersection of IPP and OPP bandgap) of L1 and L2. Part of the graph which can be drawn by symmetry is omitted. The red arrow indicates the perturbation intensity hierarchy of the PC pairs having large Jaccard indices. d Energy band structures of the PCs S10 and S11. The overall common bandgap is from 29.0 to 30.7 kHz, so the width of the bandgap is 5.7%. e Superposed phase diagram of PCs on the black dashed triangle shown in (a). Only IPP (OPP) phase transits between S01 and S11 (S11 and S10) owing to the accidental Dirac degeneracy while both IPP and OPP phase transits between S10 and S01, mirror-symmetry pair.

On the final selection of the PCs for the valley topologically protected edge state, the intervalley mixing should be carefully considered, because large intervalley mixing may directly disturb the topological protection. The reduction of the numerically calculated valley Chern number compared to the ideal magnitude of 0.5 reveals the intervalley mixing level, as the magnitude represents the localization level of Berry curvature near the valleys: the larger the magnitude of the valley Chern number, the smaller the intervalley mixing30. (In this work, deviation of the transmission from 0 dB is shown in transmission spectra in Supplementary Figs. 5c and 12b, d, f, and they reveal the relation between intervalley mixing and valley Chern number together with the numerically calculated valley Chern number in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 9.) The magnitude of the intervalley mixing is strongly and positively correlated with perturbation intensity, so limited perturbation intensity is required for small intervalley mixing43. However, limited perturbation intensity also leads to the limited width of the bandgap, which means a narrow working frequency for the topological protection. Thus, a moderate level of perturbation intensity is required for the valley PC to have both negligible intervalley mixing and significant bandgap19.

Among all candidates sorted by Jaccard index (Fig. 4c), PCs with perturbation (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (0.25, 0.15) and (0.15, −0.35), named S10 and S11 following their topological phases i1o0 and i1o1, respectively, have such moderate perturbation intensity with a magnitude of valley Chern numbers larger than 0.31 (Supplementary Fig. 9a), and the common bandgap wider than 5% (Fig. 4d). Their mirror-symmetry pairs with perturbations (b1/B1, b2/B2) = (−0.25, −0.15) and (−0.15, 0.35), named S01 and S00, respectively in the same way, also satisfy the desired conditions with the same common bandgap undoubtedly. Now, four PCs (S00, S01, S10, and S11) having all distinct superposed topological phases with common bandgap are successfully designed. For clarity, Bloch wave functions and Berry curvatures for the four PCs were drawn in Supplementary Fig. 9. Topological phase transition among S11, S10, and S01, revealed by Bloch frequency with Bloch states at valley K, clearly shows that the formation of accidental Dirac degeneracy can differ according to the polarization of elastic wave, and indicate how to design polarized and topologically protected edge states (Fig. 4e).

The number of topologically protected edge states emerging at the boundary between two PCs is the same as the difference of topological index between the two PCs, as the bulk-boundary correspondence states. Figure 5a shows the domain wall S01S10, in which S01 is located on the upper domain and S10 is located on the lower domain, together with its band diagram. Because the difference of ideal valley Chern number between S01 and S10 is 1 for both IPP and OPP waves, one IPP edge state and one OPP edge state must emerge on the domain wall S01S10 if the intervalley mixing is negligible according to the bulk-boundary correspondence. Supplementary Fig. 10a proves that the blue and red solid lines in the band diagram correspond to these IPP and OPP edge states, respectively, validating that the intervalley mixing is negligible in this domain wall. In the same manner, domain wall S01S11 possesses one IPP topological edge state only (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 10b), and domain wall S11S10 possesses one OPP topological edge state only (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 10c) according to the bulk-boundary correspondence. The IPP edge state in the domain wall S01S11 and the OPP edge state in the domain wall S11S10 resemble IPP and OPP edge states of the domain wall S01S10 respectively, because S11 has the same topological phase with S10 for IPP wave and, with S01 for OPP wave (Supplementary Fig. 10). The band diagrams for the other domain walls are shown in supplementary Fig. 11. Topological protection against sharp angles at the proposed domain walls are also demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 12.

a, b, c Schematics of (a) domain wall S01S10, (b) domain wall S01S11, and (c) domain wall S11S10, and their band diagrams. Ideal valley Chern numbers and their difference for in-plane polarized (IPP) [out-of-plane polarized (OPP)] wave are written in blue[red] color. The solid blue(red) line in the band diagram corresponds to the IPP(OPP) edge state of the domain wall, and the light-blue(light-red) area corresponds to the bulk band of the phononic crystals. The dotted blue(red) line in the diagram corresponds to IPP(OPP) edge state for the domain wall S10S01 for (a), S11S01 for (b), and S10S11 for (c). Linear polarization of each edge states are presented in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Waveguiding dependent on elastic wave polarization

Separation of the elastic wave into IPP and OPP waves can be achieved by PC constructed with the three domains S10, S01, and S11 shown in Fig. 6a. The separation mechanism is depicted in Fig. 6b. The hybridized vibration, a mixture of IPP wave and OPP wave, is injected into the PC through port 1. Both IPP wave and OPP wave can be guided to the junction from port 1 through the S10S01 domain wall based on the nontrivial edge states. The wave is separated into IPP wave and OPP wave following the bulk-boundary correspondence at the junction. The IPP wave transmits toward port 2 from the junction because S11 has IPP topological phase (i1) same as S10 (i1) but different from S01 (i0). In contrast, the OPP wave transmits toward port 3 because the OPP topological phase of S11 (o1) is different from S10 (o0) but the same as S01 (o1). As a result, the hybridized vibration injected through port 1 gets split into IPP and OPP waves through ports 2 and 3, respectively. Moreover, since every wave path for the separation is the boundary of two domains with different topological phases, the wave separation process, as well as the wave propagation, is topologically protected. IPP displacement and OPP displacement fields are presented in Fig. 6c, d, respectively, for harmonic hybridized vibration input to port 1, showing perfect separation of the IPP and OPP waves. Here, no standing wave is observed despite the wave path bend, showing the robustness of topologically protected waves. The separation performance for more generalized input to port 1 is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 13c, d. More evidences demonstrating the topologically protected separation including broadband characteristics within the topological bandgap of the separation and robustness against various disorders are presented in Supplementary Figs. 13, 14, respectively. Moreover, we tested if the separation performance is maintained even with the nonlinear effect in Supplementary Fig. 16. We found that the separation performance is preserved even when the maximum displacement is several times larger than the plate thickness with a nonlinear effect.

a Configuration of phononic crystals (PCs) with Y-junction made of S10, S01, and S11 for the separation of elastic waves. All edges between two PCs are zigzag edges, in which intervalley scattering is negligible. b Separation mechanism of an elastic wave at the Y-junction. The Violet arrow represents the hybridized vibration or wave injected to port 1. IPP and OPP wave trajectory are denoted as arrows, blue-colored for IPP and red-colored for OPP wave respectively, where ideal valley Chern numbers at valley K of each PCs are present to support the existence of the corresponding edge states. c, d In-plane displacement field (c) and out-of-plane displacement field (d) of the configuration for the hybridized vibration of 30 kHz injected to port 1.

In addition to the separation, IPP and OPP waves can be guided simultaneously and independently in the same platform. They can be merged, separated, or even cross each other, since we have all superposed topological phases. This independent routing ability of IPP and OPP waves has great potential for information transfer because IPP and OPP guided waves can be utilized as two different non-crosstalk channels. Figure 7a shows the PC design with three decided domains S10, S11, and S01, and one undecided domain X for independent routing of IPP and OPP waves. Irrelevantly to X, the information can be transferred through IPP wave via port 2 or through OPP wave via port 1 (Fig. 7b). By choosing the appropriate domain for X, the IPP wave and OPP wave can be transferred to either port 3 or port 4, independent of each other. For instance, when the domain X is S00, because the IPP phase is the same between S10 and S11, and between S00 and S01, and because the OPP phase is the same between S11 and S01, and between S10 and S00, the IPP wave is routed toward port 4, and the OPP wave is routed toward port 3, crossing each other. The rest cases are presented in Fig. 7c, verifying the potential of elastic waves in the information transfer. Supplementary Fig. 17 also demonstrates the crossing of IPP and OPP guided waves, but together with their topological protection against the bent path.

a Configuration of phononic crystals (PCs) made of S10, S01, S11, and undecided X for independent control of IPP and OPP wave. b Schematics of IPP and OPP wave input. IPP and OPP waves of 30 kHz are injected through ports 2 and 1 respectively, where ideal valley Chern numbers at valley K of each PCs are present to support the existence of the corresponding edge states. c In-plane and out-of-plane wave trajectories and displacement fields of the configuration for X = S00, S01, S10, and S11.

Discussion

In this work, we have utilized the rich polarization of elastic wave together with valley degree of freedom via the accidental Dirac degeneracy, to achieve the topologically protected elastic wave separation according to the polarization of the wave. IPP and OPP valley Hall phases, which are usually dealt separately, are designed to generate the superposed valley phase which can be used to deal with all components of elastic wave in the frequency of interest. In this process, all the valley Hall phase is provoked via the accidental Dirac degeneracy instead of deterministic degeneracy, so that IPP and OPP valley Hall phases can be coupled arbitrarily without sticking to each other. The generation mechanism of accidental degeneracy is for the first time proposed with the deductive reasoning based on deterministic Dirac degeneracy, as no sufficient mechanism generating the accidental degeneracy have been revealed to the best of our knowledge. Strategy to achieve the topologically protected separation with the accidental degeneracy is also suggested with the aid of the Jaccard index.

Recently, Wen, X. et al. suggested the topologically protected edge state based on accidental degeneracy using rotating scatterers27. However, the rotating scatterers do not necessarily guarantee the existence of accidental Dirac degeneracy, and accordingly, such accidental degeneracy cannot be tuned easily. In this work, we have tuned the accidental degeneracy line to effectively separate the IPP and OPP topological phase, owing to the definite existence of accidental degeneracy offered by mechanisms adopted. Regarding the elastic wave separation using the topological property, separation according to the valley-polarization has been demonstrated numerically and experimentally based on helical-valley modes32. Elastically polarized IPP and OPP waves had been hybridized to generate helical mode, thus separated wave was linear-mode-hybridized as well. In this work, we have differentiated IPP and OPP waves from the beginning, and the superposed valley Hall phase is used to separate them, instead of helical-valley mode. Thus, this work is distinguished by both the standard of separation, and physics underlying the separation. Lastly, separation of IPP and OPP waves has been demonstrated based on the polarization bandgap38,39, wave phase difference40, and tensor engineering41. What differentiates this work from them is the topological protection during the separation process. In this work, thanks to the topological protection, the separation can be maintained even when the structure is a little bit perturbed, and energy or information can be preserved with transmission close to unity during the separation process.

While we have only concentrated on the frequency around 30 kHz in this work, the working frequency for the separation can be tuned according to the application area owing to the scalability of elastic PCs. In the ultrasonic or higher frequency range, independent controllability for IPP and OPP waves can be utilized in signal processing or information transfer, by treating the elastic PCs as the multiple channels, which have no crosstalk with each other. In audible or lower frequency range, elastic wave manipulation can be used in energy harvesting or vibration isolation, while independent controllability for IPP and OPP waves enables each IPP or OPP wave to be applied independently as needed. This work can also be adopted in sensor or actuator applications, since 2D motion can be converted into two 1D motion by the separation of IPP and OPP waves (or vice-versa by merging IPP and OPP waves). We note that the same procedure can also be applied to steer the transverse electric (TE) mode and transverse magnetic (TM) mode independently and simultaneously in photonic devices.

Methods

Numerical simulations

The commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics Structural Mechanics (Solid Mechanics) module, which is based on the finite element method (FEM), is used for numerical simulations. The computer models used for the simulations are three-dimensional solid, not the two-dimensional plate except for Supplementary Figs. 5c and 12b, d, f: In these figures, 2D FEM based on Mindlin–Reissner plate theory is used. The substrate is assumed to have the properties of acrylic plastic with a density of 1190 kg m−3, Young’s modulus of 3.2 GPa, and Poisson’s ratio of 0.35. We note that acrylic plastic was chosen for the ease of fabrication to conduct the experiments later on, and the same phenomenon in this work can be realized with the properties of other substrates. The maximum element size of the mesh is set to be less than one-thirtieth of the wavelength of 30 kHz shear wave in acrylic plastic. Eigenfrequency study is implemented with Bloch periodicity boundary conditions for calculating the energy band diagram for both bulk and edge, while single primitive cell is used for the bulk and 24 × 1 supercell composed of two different primitive cells are used for the edge23. Polarization factor42,

is calculated for each state to differentiate IPP and OPP waves in the band diagram, where (u, v, w) is the displacement field. After the differentiation of the state, IPP and OPP band is drawn independently with 48 (51) points for the bulk (edge), equispaced in k-space. On the other hand, for the full-field simulation, frequency-domain perturbation study is implemented with a low-reflecting boundary (for 3D FEM) or spring foundation (for 2D FEM) on the outermost boundary of configuration. The in-plane and out-of-plane displacement field is calculated by \(\sqrt {\left| u \right|^2 \,+\, \left| v \right|^2}\) and |w | , respectively, and the polarization factor for each port is calculated by the expression given in Eq. (4) with the volume comprised of 10 × 3 primitive cells at each port, where (u, v, w) is complex-valued displacement field with respect to the harmonic perturbations.

Computation for topological phase diagram and Dirac degeneracy angle

To classify the topological phase of PCs without calculating the valley Chern number,

and

are calculated for each state in addition to the polarization factor p where (uX, vX, wX) is displacement field at sublattice X. Since every valley state at valley K is either p− or q+, the sign of ηIPP and ηOPP and value of p determines the valley Hall phase of the PC. A topological phase diagram is drawn by determined valley Hall phases, with 20,201 points when c = 0.25, with 5101 points in Supplementary Fig. 6, and with 841 points for the rest. For the Dirac degeneracy angle θIPP and θOPP, valley Hall phases are determined for PCs with perturbations (b1/B1, b2/B2) = 0.1(cos γ, sin γ) where γ varies from 0° to 180° with 181 steps. Then, θIPP and θOPP are determined with error less than 0.5° by x-intercept of the graph Δω = ωp− − ωq+ with respect to γ for IPP and OPP waves.

Calculation of valley Chern numbers

From the Bloch wave function or displacement field of the primitive cell, integration of Berry curvature over an infinitesimal area or line integration of Berry connection around the area can be calculated by the phase evolution of Bloch wave function along with the counterclockwise rotation. The infinitesimal area used here is square44 with side length 0.01 × (2π/a), where a is the magnitude of the lattice vector. The Valley Chern number is obtained by summing up the Chern invariant of bands under the bandgap, where the Chern invariant is an integration of the Berry curvature divided by 2π. In this work, Berry curvature is integrated over the square of side length 0.04 × (2π/a) centered at point K, for the Chern invariant. Berry curvatures shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 9 are not the Berry curvatures of the single band, but the summed Berry curvatures of the bands under the bandgap, so valley Chern number at valley K is obtained by integrating them.

Data availability

All data needed to reach the conclusions of this study are included in this published article and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X. L. & Zhang, S. C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Klitzing, K. V., Dorda, G. & Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized hall resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494–497 (1980).

Pankratov, O. A., Pakhomov, S. V. & Volkov, B. A. Supersymmetry in heterojunctions: band-inverting contact on the basis of Pb1xSnxTe and Hg1xCdxTe. Solid State Commun. 61, 93–96 (1987).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 1–4 (2005).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 1–4 (2007).

Mak, K. F., McGill, K. L., Park, J. & McEuen, P. L. The valley hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489–1492 (2014).

Wang, Z., Chong, Y., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Observation of unidirectional backscattering-immune topological electromagnetic states. Nature 461, 772–775 (2009).

Khanikaev, A. B. et al. Photonic topological insulators. Nat. Mater. 12, 233–239 (2013).

Ma, T. & Shvets, G. All-Si valley-Hall photonic topological insulator. N. J. Phys. 18, 1–9 (2016).

Ma, T. & Shvets, G. Scattering-free edge states between heterogeneous photonic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 95, 1–12 (2017).

Kim, M., Jacob, Z. & Rho, J. Recent advances in 2D, 3D and higher-order topological photonics. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 1–30 (2020).

Xiao, M. et al. Geometric phase and band inversion in periodic acoustic systems. Nat. Phys. 11, 240–244 (2015).

Khanikaev, A. B., Fleury, R., Mousavi, S. H. & Alù, A. Topologically robust sound propagation in an angular-momentum-biased graphene-like resonator lattice. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7 (2015).

He, C. et al. Acoustic topological insulator and robust one-way sound transport. Nat. Phys. 12, 1124–1129 (2016).

Lu, J. et al. Observation of topological valley transport of sound in sonic crystals. Nat. Phys. 13, 369–374 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Topological acoustic delay line. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 1–11 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Directional acoustic antennas based on valley-Hall topological insulators. Adv. Mater. 30, 1–7 (2018).

Tian, Z. et al. Dispersion tuning and route reconfiguration of acoustic waves in valley topological phononic crystals. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–10 (2020).

Prodan, E. & Prodan, C. Topological phonon modes and their role in dynamic instability of microtubules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 1–4 (2009).

Mousavi, S. H., Khanikaev, A. B. & Wang, Z. Topologically protected elastic waves in phononic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7 (2015).

Yu, S. Y. et al. Elastic pseudospin transport for integratable topological phononic circuits. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–8 (2018).

Guo, Y., Dekorsy, T. & Hettich, M. Topological guiding of elastic waves in phononic metamaterials based on 2D pentamode structures. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–7 (2017).

Pal, R. K. & Ruzzene, M. Edge waves in plates with resonators: an elastic analogue of the quantum valley Hall effect. N. J. Phys. 19, 1–18 (2017).

Yan, M. et al. On-chip valley topological materials for elastic wave manipulation. Nat. Mater. 17, 993–998 (2018).

Liu, T. W. & Semperlotti, F. Tunable acoustic valley-Hall edge states in reconfigurable phononic elastic waveguides. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 1–10 (2018).

Wen, X. et al. Acoustic Dirac degeneracy and topological phase transitions realized by rotating scatterers. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 1–4 (2018).

Li, S., Kim, I., Iwamoto, S., Zang, J. & Yang, J. Valley anisotropy in elastic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 100, 1–10 (2019).

Ma, J., Sun, K. & Gonella, S. Valley Hall in-plane edge states as building blocks for elastodynamic logic circuits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 1–8 (2019).

Zhu, H., Liu, T. W. & Semperlotti, F. Design and experimental observation of valley-Hall edge states in diatomic-graphene-like elastic waveguides. Phys. Rev. B 97, 1–9 (2018).

Zhang, Q., Chen, Y., Zhang, K. & Hu, G. Dirac degeneracy and elastic topological valley modes induced by local resonant states. Phys. Rev. B 101, 1–7 (2020).

Miniaci, M., Pal, R. K., Manna, R. & Ruzzene, M. Valley-based splitting of topologically protected helical waves in elastic plates. Phys. Rev. B 100, 1–11 (2019).

Ma, G., Xiao, M. & Chan, C. T. Topological phases in acoustic and mechanical systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 281–294 (2019).

Mei, J., Wu, Y., Chan, C. T. & Zhang, Z. Q. First-principles study of Dirac and Dirac-like cones in phononic and photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 86, 1–7 (2012).

Lu, J. et al. Dirac cones in two-dimensional artificial crystals for classical waves. Phys. Rev. B 89, 1–10 (2014).

Shin, H. et al. Control of coherent information via on-chip photonic-phononic emitter-receivers. Nat. Commun. 6, 2–9 (2015).

Park, C. S. et al. Two-dimensional octagonal phononic crystals for highly dense piezoelectric energy harvesting. Nano Energy 57, 327–337 (2019).

Ma, G. et al. Polarization bandgaps and fluid-like elasticity in fully solid elastic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–8 (2016).

Liu, H., Zhang, Q., Zhang, K., Hu, G. & Duan, H. Designing 3D digital metamaterial for elastic waves: from elastic wave polarizer to vibration control. Adv. Sci. 6, 1–6 (2019).

Su, X., Lu, Z. & Norris, A. N. Elastic metasurfaces for splitting SV- and P-waves in elastic solids. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 1–9 (2018).

Zheng, M. et al. Non-resonant metasurface for broadband elastic wave mode splitting. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 1–5 (2020).

Miniaci, M. et al. Proof of concept for an ultrasensitive technique to detect and localize sources of elastic nonlinearity using phononic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 1–6 (2017).

Qian, K., Apigo, D. J., Prodan, C., Barlas, Y. & Prodan, E. Topology of the valley-Chern effect. Phys. Rev. B 98, 1–15 (2018).

Fukui, T., Hatsugai, Y. & Suzuki, H. Chern numbers in discretized Brillouin zone: efficient method of computing (spin) Hall conductances. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 74, 1674–1677 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Creative Research Initiative Program (2015R1A3A2028975) funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-J.L. and I.-K.O. conceived the idea of the topological separation of elastic waves. M.-J.L. designed the study, carried out the whole numerical simulations, analyzed the data, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. I.-K.O. supervised the research at all stages and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, MJ., Oh, IK. Robust separation of topological in-plane and out-of-plane waves in a phononic crystal. Commun Phys 5, 17 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00793-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00793-z

This article is cited by

-

Simultaneous low-frequency vibration isolation and energy harvesting via attachable metamaterials

Nano Convergence (2024)

-

Quantum valley Hall effect-based topological boundaries for frequency-dependent and -independent mode energy profiles

Communications Physics (2024)

-

On Klein tunneling of low-frequency elastic waves in hexagonal topological plates

Applied Mathematics and Mechanics (2024)