Abstract

Laser frequency comb generators on photonic chips open up the exciting prospect of integrated dual-comb microspectrometers. Amongst all nanophotonic platforms, the technology of low-loss thin-film lithium-niobate-on-insulator shows distinguishing features, such as the possibility to combine various optoelectronic and nonlinear optical functionalities that harness second- and third-order nonlinearities, and thus promises the fabrication of a fully on-chip instrument. Here, a critical step towards such achievement is demonstrated with an electro-optic microring-based dual-comb interferometer. Spectra centered at 191.5 THz and spanning 1.6 THz (53 cm−1) at a resolution of 10 GHz (0.33 cm−1) are obtained in a single measurement without requiring frequency scanning or moving parts. The frequency agility of the system enables spectrally-tailored multiplexed sensing, which allows for interrogation of non-adjacent spectral regions, here separated by 6.6 THz (220 cm−1), without compromising the signal-to-noise ratio. Our studies show that electro-optic-based nanophotonic technology holds much promise for new strategies of molecular sensing over broad spectral bandwidths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The past decade has witnessed a remarkable progress in designs and technologies for chip-scale spectrometers1 relying on different spectrometric techniques based e.g., on interference2,3,4,5,6 or dispersion7. However, acquiring a large number of spectral elements with a high resolution in a single measurement remains challenging. In recent years, a new spectrometric technique, dual-comb interferometry, has emerged as a powerful approach to high-resolution spectroscopy. It has been successfully demonstrated with a variety of table-top laser sources, including rather compact ones, such as fiber-doped mode-locked laser and electro-optic (EO) modulators8. This technique measures the time-domain interference between two frequency combs of slightly different line spacings. The Fourier transform of the interference pattern reveals a radio-frequency (RF) spectrum made of the beat notes between pairs of comb lines, one from each comb. Similar to Michelson-based Fourier transform spectroscopy9, all the spectral elements are simultaneously measured on a single photodetector, in a multiplexed fashion, resulting in spectra with an unparalleled consistency. The main distinguishing features of dual-comb spectrometers are the absence of moving parts, the use of coherent light sources that enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), the possibility of directly calibrating the frequency scale within the accuracy of an atomic clock, and narrow instrumental line shapes. Transferred to an integrated miniaturized device, such characteristics could significantly enhance the capabilities of in-situ real-time spectroscopic sensing. First proofs of concept towards an on-chip dual-comb spectrometer have been reported with Kerr combs10,11,12,13 and quantum -and interband- cascade lasers14,15. The suitability of an on-chip III-V-on silicon mode-locked laser of 1 GHz repetition frequency for dual-comb spectroscopy has also been investigated16. Kerr combs rely on the third-order nonlinearity of the material and, until recently17, have been most efficient in ranges of large line spacing (hundreds of GHz to several THz). This makes them appealing for broadband spectroscopy of condensed matter samples11,12. Nevertheless, scanning the frequency of the comb lines via thermo-optic effect has been reported as a means to improve the resolution18,19. Electrically-pumped quantum- and interband-cascade lasers directly emit in the molecular fingerprint mid-infrared region, though their span and number of usable comb lines are small14,15.

Here, we report an experiment of dual-comb spectroscopy using integrated comb sources based on second-order nonlinearity, implemented in a low-loss thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) photonic platform. We also demonstrate the ability to spectrally tailor frequency combs, crucial for signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) optimization, by simultaneously exciting the integrated comb source with different lasers. An important feature of our approach is its frequency agility, that is, the possibility to select the combs’ spectral position quickly and freely by simply dialing a knob.

Results

Device design and principle

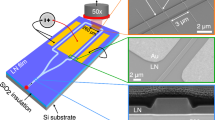

Our EO dual-comb set-up consists of two racetrack optical resonators (on two separate chips), each with through and drop optical ports, integrated with a pair of microwave electrodes (Fig. 1)20. For this proof-of-principle demonstration, the two EO resonators are implemented on two separate chips for facilitating the exploration of the parameter space and improving the fabrication yield. The resonators are formed by partially etching a 1.3 µm-wide waveguide into a 600-nm-thick X-cut LN device layer sitting on top of 2 µm of thermal SiO2. The fabricated devices are cladded with a 1 µm-thick SiO2 layer (see Methods). The cross-section of the waveguide is chosen to support a high Q-factor fundamental transverse electric mode (loaded Q ~106, see Supplementary Note 1). Furthermore, its weak normal dispersion enables broadband frequency comb generation. For efficient EO interaction, the microwave electrodes are placed along the y-axis of the LN crystal in order to utilize the largest electro-optic coefficient (r33 = 30 pm V−1). As compared to conventional EO-Comb generators21,22 based on bulk LN crystals, the tight confinement of the light allows for electrodes to be placed close to the optical waveguide (~ 3.3 µm from each side) without introducing significant optical losses23.

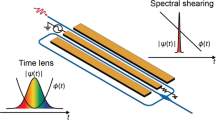

In this conceptual representation, three narrow continuous-wave (CW) laser lines of frequency f1, f2, and f3 are used to excite the optical modes of a resonant EO modulator, driven at the microwave frequency fRF1 that corresponds to the resonator free spectral range. The generated composite comb contains three non-adjacent combs, centered at f1, f2, and f3, each having comb line spacing of fRF1. Central frequency and span of each of the three combs are chosen to interrogate targeted features in an absorbing sample, while leaving out regions without absorber or with interfering species, and can be adjusted independently with agility. Three slightly frequency-shifted replica of the original laser lines are produced and injected into a second resonant EO modulator, driven at a slightly different repetition frequency fRF2, providing a reference spectrum. The interrogating and reference comb beams interfere on a fast photodetector. In this process, pairs of comb lines, one from each beam, produce a composite radio-frequency (RF) comb of line spacing fRF2-fRF1, mapping the spectral information from the optical domain, centered at f1, f2, and f3 to the RF domain, centered at δf1, δf2, δf3, respectively. The frequency agility of the resonant EO modulator is a unique feature that enables on demand spectral tailoring and optimization of the signal-to-noise ratio.

To generate an EO comb, each racetrack resonator is fed simultaneously with a continuous-wave (CW) laser (frequency around 191.5 THz) and with a microwave synthesizer. The frequency of the microwave source is chosen to be the same as, or close to, the free spectral-range of the racetrack resonator. In this way, the three-wave mixing process is resonantly enhanced and results in an efficient sideband generation during each cavity roundtrip24,25,26. Owing to the low optical loss of the LN platform, the equivalent path length of the light is (F/2π) × L ~ 10L, where F is the cavity finesse, and L is the cavity roundtrip length (See Supplementary Note 1). The beam of the generated frequency comb is outcoupled via the drop port of the racetrack resonator, and collected using a lensed optical fiber.

Concept of spectrally-tailored spectroscopy

The multiplexed nature of Fourier transform spectroscopy provides an unparalleled consistency of the spectra, often at the expense of sensitivity9: assuming that the total power onto the detector is kept constant, the SNR is inversely proportional to the number of spectral elements, here the comb lines. Detector nonlinearities usually set the maximum acceptable power to values much smaller than what is available from short-pulse laser sources. In other words, the broader the span, the lower the SNR when all other parameters are kept equal (measurement time, resolution, total power). Acquiring spectral regions where there are no transitions of interest comes at a high price: while the SNR scales linearly with the number of comb lines, it scales with the square root of measurement time. The widely-used solution to boost the SNR has been to use optical filters that select a single spectral band of interest. With EO combs though, it becomes possible to simultaneously inject several CW lasers into each EO microring, labeled EO-Comb source1 and EO-Comb source2 in Fig. 1. Several (three in Fig. 1) pairs of mutually coherent combs are thus produced. All combs generated in one microring share the same line spacing but their center frequencies are independently tunable. To illustrate the unique possibilities of spectral tailoring in our platform, we simultaneously excite one of the LN racetrack resonators with two independent CW feed lasers at a frequency of 178.9 and 199.9 THz, respectively (wavelength: 1676 nm and 1500 nm, respectively). Then, by driving the resonator at the microwave frequency of 10.49 GHz, we simultaneously generate two EO combs, which are not mutually coherent and which are separated by more than 21 THz (see Supplementary Note 2). Importantly, the low group velocity dispersion (GVD) of this resonator allows the generation of several combs from 172 to 210 THz range (1430 to 1740 nm in wavelength), which can be further extended by increasing the modulation strength (see Supplementary Note 3). The detuning of the optical carriers and that of the microwave frequency are additional tuning knobs for adjusting the span and the shape of the spectrum20. This ability to tailor the spectra lifts the compromise between span and SNR: the interrogated regions are freely selected, and other domains may be left out, where e.g., there is no absorption or only of unwanted species, or where there is strong overlap between the transitions of the target and those of interfering species (such as water vapor). The spectral tailoring can be dynamically changed and quickly adapted to new situations.

Dual-comb-spectrometer characterization

We first characterize a dual-comb set-up in a single spectral band using a single CW laser and no sample inserted in the beam path (Methods). Since the two combs originate from the same CW laser, a good passive mutual coherence may be achieved, which is important for dual-comb interferometry. We measure the mutual coherence time of 5 × 10−3 sec, currently limited by the fact that two comb sources, on two different chips, are located on two different optical benches, due to lab space restrictions. The layout of our dual-comb interferometer is similar to that used with bulk EO modulators27,28, where mutual coherence times exceeding 1 s have been reported28. Thus, we anticipate that similar performance will be possible in our approach, e.g., by fabricating the two microrings on the same photonic chip. The time-domain interference signal, the interferogram, is sliced in 5 × 10−3-s sequences, and a complex Fourier transform of each sequence provides amplitude and phase spectra with well-resolved individual comb lines. The averaged spectrum (95-s averaging time) reveals 160 comb lines (Fig. 2b), with a remarkable cardinal sine line shape (Fig. 2c). The instrumental line shape (Fig. 2c), which perfectly follows the theoretical expectation of convolution of narrow beat notes by the Fourier transform of a boxcar, and the evolution of the SNR of the comb lines as the square root of the averaging time (Fig. 2d) illustrate the high degree of interferometric control. The large tunability of the line spacing can be obtained by detuning the microwave signal driving the resonator, and it can be used to vary the refresh rate of the interferograms on demand (Fig. 2e). This could be of interest for broadband real-time dual-comb spectroscopy applications. However, similar to all other on-chip dual-comb spectrometers, the strong variation of the intensity of the comb lines across the spectrum currently limits the measurement time of the spectrum.

a The setup for dual-comb spectroscopy for the acetylene gas cell at near atmospheric pressure with two EO-Comb sources (CW: Continuous-wave laser, AOFS: Acousto-optic frequency shifter; BS: Beam splitter). b Apodized dual-comb spectrum (f1 = 191.55 THz and δfrep1 = 40 MHz) with the measurement time of 95 s. 19,000 interferograms (5 ms each) are acquired and processed, and the amplitude spectra are averaged. The two EO combs are driven with microwave frequencies with fRF1 = 10.45 GHz and fRF2-fRF1 = 0.1 MHz. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the center comb line is 8 × 105, and the average SNR of 160 comb lines is 1 × 105. c An unapodized individual comb line, near 41 MHz in (a), is shown featuring a cardinal sine instrumental line shape. d The evolution of the SNR of three selected comb lines from (a) at 40 MHz, 42 MHz, and 44 MHz over the measurement time. Their linear fitted slopes (black line) are 0.46, 0.49, and 0.54, respectively, indicating that SNR increases with the square root of the measurement time. e The reconfigurability of the microring EO dual-comb system. The interferogram refresh rate (fRF2-fRF1) is varied on demand at 0.800, 0.200, 0.100, and 0.001 MHz.

Absorption spectroscopy of acetylene

A cell, filled with acetylene at close to atmospheric pressure, is then inserted in the set-up. The cell is probed by EO-Comb source1, while EO-Comb source2 serves as the local oscillator. The transmittance (amplitude) and the dispersion (phase) in three spectra, averaged over 95 s each, are stitched to increase the span. The results are displayed in Fig. 3 for the spectral samples corresponding to the maxima of comb lines. The resolution of 10 GHz, determined by the comb line spacing, is two times better than what has been accomplished using Kerr combs10, and is slightly larger than the self-broadened full-width at half-maximum of the rovibrational lines at 9.86 × 104 Pa, of 7.7 GHz, on average (Methods). The residuals - the difference between the observed spectrum and HITRAN database29 – are below 10%, with a standard deviation of 3.4%. Supplementary Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of our work with previous dual-comb experiments using two frequency comb generators on photonic chips.

a Experimental transmittance spectrum (blue circles – experimental samples – connected by a red line) and transmittance spectrum (blue) computed from the line parameters available in the HITRAN database. The spectral resolution is 10.45 GHz. Three spectra, centered at frequencies of 193.93 THz, 194.56 THz, and 194.64 THz, are stitched. The residuals (green) - the difference between the observed spectrum and HITRAN – are below about 10% with a standard deviation of 3.4%. The residuals are calculated by subtracting the experimental intensity of the spectral sample and the intensity of the calculated sample at the same frequency, for each experimental frequency (positions of the open dots). b Experimental dispersion spectrum (red) and dispersion spectrum simulated from HITRAN database (blue). The residuals (green) are below 10% with a standard deviation of 2%.

Experimental demonstration of a spectrally-tailored dual-comb spectrometer

Finally, we demonstrate a first proof-of-concept of a spectrally-tailored dual-comb interferometer (Fig. 4). The LN electro-optic comb platform allows for the operation with multiple input lasers due to the inherent phase-locking mechanism established by the microwave driving, as well as the capability of tailoring the dispersion profile. In our experiment, we use two CW lasers, centered at f1 = 192.7 THz (wavelength: 1556 nm) and f2 = 186.1 THz (wavelength: 1661 nm), to drive the EO-Comb source1, while the EO-Comb source2 is fed with acousto-optically frequency-shifted light at frequency f1+δf1 and f2 + δf2, with δf1 = 40 MHz and δf2 = 25 MHz (Fig. 4). Two comb sources are driven with microwave signals of frequency fRF1 = 10.45 GHz and fRF2 = fRF1+0.1 MHz, respectively. As a result, two pairs of combs, each comprising 162 comb lines over a span of 1.7 THz, are generated with center frequencies that are 6.6 THz apart (see Supplementary Note 4). Owing to the distinct acousto-optic frequency shifts, the two RF spectra do not overlap. The RF spectra could also be interleaved to achieve a homogeneous SNR (Methods) by choosing, e.g., δf2 = δf1+(fRF2-fRF1)/2, as long as the mutual coherence time of the system allows for resolved comb lines to disentangle the spectra. Even in this simple proof-of-principle demonstration, more than 100 spectral sections of 2000 comb lines each could be simultaneously measured, which represents overwhelming capabilities. Our integrated platform is thus capable of probing transitions that are spectrally distant. Such a capability is particularly interesting for optimizing the simultaneous detection of several species, as e.g., encountered in a gas mixture, where the most intense resonances of each species can be spectrally remote from each other. Meanwhile, by tailoring the comb spectra to the narrow regions where each molecule of interest absorbs, the SNR is optimized: the gaps between regions are not acquired and therefore do not contribute to degrading the SNR.

a Experimental set up. CW, continuous-wave laser; RF, radio frequency; AOFS, acousto-optic frequency shifter; BS, beam splitter. CW1 and CW2 with f1 = 192.7 THz and f2 = 186.1 THz pass through two AOFS (with δf1 = 40 MHz, and δf2 = 25 MHz), respectively. CW1 and CW2 are injected into EO-Comb source1, while their frequency-shifted replica are sent to EO-Comb source2 with fRF1 = 10.45 GHz) and fRF2-fRF1 = 0.1 MHz. The outputs are heterodyned on a balanced detector, and the time-domain interference signal is digitized with a data acquisition board. b Dual-comb spectrum with a measurement time of 9.8 s. The two RF combs, which center frequencies are 15 MHz apart, correspond to two EO combs that are 6.6 THz apart in the optical domain.

Discussion

Here, we have demonstrated an EO dual-comb spectrometer based on thin-film lithium-niobate technology for measuring the absorption and dispersion spectra of gas-phase acetylene. A proof of concept of spectrally-tailored dual-comb interferometry highlights one of the assets of the lithium-niobate platform. Compared to other on-chip demonstrations based on Kerr combs10,11,12 or semi-conductor lasers14,15, our EO system points to a high versatility. The frequency agility and the spectral tailoring are its most promising features. Specifically, when compared to on-chip microresonator comb sources based on the Kerr effect, the advantages of our EO approach include less stringent requirement on dispersion, flexibility with comb line spacing, ability to operate at low optical powers, and simultaneous operation at a number of different frequencies. Unlike with non-resonant EO-comb synthesizers30, our EO microrings do not allow dual-comb generation in a single generator straightforwardly. Driving the microring at two distinct RF frequencies generates a forest of sidebands, as each sideband within the microring resonances becomes modulated by each radio-frequency signal31. Recently, two independent mode families of orthogonal polarizations could be independently excited, using whispering-gallery-mode resonator polished from bulk lithium niobate32. However, such a configuration did not allow to choose the difference in repetition frequencies freely and therefore did not allow to simultaneously record, without aliasing, the dual-comb spectrum of more than 15 comb lines. In our present implementation with EO-comb generators on photonic chips, the line spacing of our EO-comb generators could be decreased (and thus, the resolution of our spectrometer improved) by increasing the size of the resonator, while maintaining (or even increasing) the comb spectral span. For example, a 10-fold increase in the resonator size, combined with a 5-fold increase in resonator Q-factor33 and a 2-fold increase in modulation strength, would enhance the resolution to 1 GHz, while maintaining the same comb span. Even larger spans could be achieved using EO-comb-generator designs based on coupled-ring resonators34 that could allow for two orders of magnitude increase in pump-to-comb generation efficiency. Our theoretical predictions indicate that an octave-spanning comb could be realized by improvements in Q-factor and with proper dispersion management20. This will enable broader interrogation regions for accessing many different species and self-referencing for high accuracy. LN’s wide transparency window (0.3–5 µm) can support EO-comb sources both in the visible region35, where electronic transitions of atoms and molecules are, and in the mid-infrared molecular fingerprint range, where most molecules have fundamental rovibrational transitions, which strengths may be up to three orders-of-magnitude larger than in the near-IR. Thus, the generation of mid-infrared EO combs is highly desirable. To accomplish this, it will be important to eliminate oxide losses beyond 3 µm, which can be achieved using suspended LN devices36 or LN on sapphire platform37.

The availability of various components in our LN platform, such as acousto-optic modulators38 and phase-modulators39 can be used for temporal and spectral shaping of the generated combs, while spectral broadening using PPLN waveguides with engineered third-order nonlinearity40 can be then used to stabilize the carrier-envelope offset frequency41. These functionalities are specific to the LN platform and they are essential for realization of practical comb sources for spectroscopy applications. They cannot be realized in e.g., Si3N4 platform popular with Kerr comb community. Combined to wafer-scale fabrication processes42, our platform can pave the way towards a fully-integrated dual-comb spectrometer on a photonic chip. One of the challenges, which is shared with all existing on-chip systems, is the improvement in resolution for multiplex gas-phase spectroscopy, without scanning the frequency of the comb lines19. Similarly, the decrease in the intensity of the comb lines from the carrier frequency narrows the spectral span and increases the measurement times. Overcoming the limitations of the dynamic range of on-chip comb sources sets another defy in device fabrication and photonic design. Nevertheless, the thin-film lithium-niobate platform, with its unique combination of ultra-low losses and strong second- and third-order nonlinearities, promises an incomparable set of novel opportunities for on-chip high-resolution spectrometers.

Methods

Device fabrication

The electro-optic (EO) racetrack microresonators are fabricated on a commercial 600 nm-thick X-cut lithium niobate (LN) wafer on 2 µm thermally grown silicon dioxide on a 500-µm silicon handle substrate (NanoLN). The waveguides and racetracks are defined using negative-tone resist (Fox16–Dow Corning) and electron-beam lithography (Elionix-F125) through multipass exposure. The pattern is then transferred to LN with a standard Ar+ reactive ion etching33. The targeted etch depth for our devices is 350 nm leaving around 250 nm of LN slab underneath. To suppress the input signal, a drop port is fabricated, using the same waveguide-to-resonator gap (650 nm) as in the case of the through port. The devices are then cladded with 1 µm thick silicon dioxide, deposited using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. A second photolithography (Heidelberg-MLA150) is performed (positive tone SPR-700 photoresist) to pattern the electrodes with ~8 µm separation. Layers of a thickness of 15 nm of Ti and 500 nm of Au are deposited using electron-beam evaporation (Denton) as the metallic contacts. Finally, after a lift-off process, the chips are diced, and their facets are mechanically polished for lensed-fiber coupling.

EO-comb-generator operation

In our experiment, the microresonator is optically injected with a CW laser at a transverse electric (TE) polarization, and it is driven by a microwave signal, provided by an amplified microwave frequency synthesizer. The cavity resonances are identified by monitoring the transmission through the through port while sweeping the input laser frequency. Next, the microwave signal is turned on to identify the cavity mode with the highest EO response - as manifested by a large resonance-broadening20,31. The microwave frequency is then finely tuned to match the free spectral range of the cavity. The laser is tuned into the cavity resonance till the broadest possible EO comb is generated. With microwave and optical sources tuned into resonance, the output fiber is aligned to the drop port and the optical signal is collected. The drop port device allows for suppression of the carrier and thus adapts the dynamic range of the dual-comb interferometer to the optical signal of interest. The straight sections of the racetrack cavity (~ 6 mm) and the gold microwave electrodes are patterned along the y-axis of the LN crystal resulting in the electric-field along the z-direction. This ensures that LN’s highest EO tensor component is utilized. We select a ground-signal-ground (GSG) configuration for the microwave electrodes in order to simultaneously modulate the light traveling in each arm of the optical cavity.

Detailed description of the dual-comb set-up

We first describe the configuration (Fig. 2a) using a single CW laser, used for producing the spectra shown in Figs. 2, 3. The entire set-up is realized with single-mode optical fibers. The beam of a single-frequency CW laser, of frequency f1 in the telecommunication region, is split into two beams. The frequency of one of the beams is shifted to f1+δf1 with an acousto-optic frequency shifter (AOFS). In our set-up, δf1 = 40 MHz. The role of the AOFS is to shift the center of the RF dual-comb spectrum to δf1. If this were not performed, the optical carrier f1 would be mapped at the zero frequency in the dual-comb spectrum and the pair of comb lines of index -n on one side of the optical carrier would be aliased at the same RF frequency as the pair of the comb lines of index n on the other side of the carrier. The use of an AOFS to avoid aliasing is already commonly reported in dual-comb spectroscopy experiments with bulk EO modulators27,28. The optical beams are coupled in and out their corresponding chips, with racetrack resonators labeled EO-Comb source1 and EO-Comb source2, using lensed fibers. Two separate LN chips are used, one of which is equipped with a thermoelectric cooler. Frequency-tuning of the laser enables to match the laser frequency and one resonance of EO-Comb source1. For overlapping the resonance of EO-Comb source2 and the laser line, adjustment of the second chip temperature is used, with the thermoelectric cooler. Each cavity is modulated at a microwave frequency that matches, or is close to, the free spectral range of the cavity. The microwave signal is provided by a commercial synthesizer and is delivered to gold electrodes placed on each side of the waveguides in the ring using RF probes. One of the microwave synthesizers driving the chip is phase-locked to the internal 10-MHz clock of the other. For EO-Comb source1, the radio-frequency is fRF1 = 10.45 GHz and for EO-Comb source2, it is varied such that fRF2- fRF1 ranges from 0.001 MHz to 0.8 MHz. An absorbing sample, at room temperature (293 K), consisting of a fiber-coupled multipass gas cell filled with acetylene (80 cm path length, 9.86 × 104-Pa pressure of acetylene in natural abundance) may be placed on the beam path of EO-Comb source1. A manual polarization controller, also on the beam path of EO-Comb source1, adjusts the relative polarization of the two beams to maximize the interference signal. The beams from EO-Comb source1 and EO-Comb source2 are then combined onto a 50:50 fiber coupler. The two outputs of the coupler are detected by a balanced photodetector with a frequency bandwidth of 150 MHz. The output of the balanced photodetector is electronically filtered to about 50 MHz and amplified. The resulting time-domain interference signal is digitized using a 16-bit data acquisition board with a rate of 125 × 106 sample s−1. The interferograms are Fourier transformed per segments of 5 × 10−3 s, corresponding to 625,000 time-domain samples. The duration of 5 × 10−3 s is selected as it is experimentally determined to correspond to the time for which one can compute the spectrum without visible distortion to the instrumental line-shape (mutual coherence time). Before the complex transform is calculated, the interferograms are zero-filled six-fold to interpolate the spectra. The amplitude (absorption spectrum) and the phase (dispersion spectrum) are then averaged 19,000-fold up to a total measurement time of 95 s. The RF spectrum is composed of lines at δf1 + n (fRF2- fRF1), where n is an integer. The computation procedure is validated by the perfect instrumental line-shape, obtained before and after the averaging process (Fig. 2b), and by the square root evolution of the signal-to-noise ratio of the comb lines as a function of the averaging time (Fig. 2d). Each comb line appears as a cardinal sine, which is the instrumental line-shape of the spectrometer (Fig. 2c). The interferogram is indeed multiplied by a boxcar function, which corresponds to the finite measurement time. Therefore, in the spectral domain, the comb lines are convolved by a cardinal sine which has a width equal to 1.2 times the inverse of the measurement time. In Fig. 2c, the full-width at half-maximum of the comb line is 240 Hz. This is 1.2 times the inverse of the measurement time of 5 × 10−3 s, used in the computation of each interferogram. Our observed line width exactly corresponds to the transform-limited expected value for the transform of time-domain traces of 5 × 10−3 s. The optical scale can be reconstituted a posteriori by substituting δf1 for f1 and (fRF2- fRF1) for fRF1.

Experimental set-up for spectrally-tailored interferometry

When spectral tailoring is implemented, as in the set-up sketched in Fig. 4, several (two in Fig. 4) CW lasers are simultaneously injected in the two EO microrings. The two CW lasers in Fig. 4 emit at the optical frequencies f1 and f2, respectively. Each laser beam is split into two beams, one of which is sent into an AOFS driven at a frequency of δf1 and δf2, respectively. In our experiment δf1 = 40 MHz and δf2experiment δf1 = 25 MHz. We used two RF shifts δf1 and δf2 rather distant because of the availability of the equipment. In practice, it would be possible to interleave the two RF spectra provided that δf2 is different from δf1. The laser beams at frequencies f1 and f2 are combined and sent into EO-Comb source1, while the beams at shifted frequencies f1 + δf1 and f2 + δf2 are combined and sent into EO-Comb source2. At the output of the microring EO-Comb source1, two combs, centered at frequencies f1 and f2 are produced. In the example of Supplementary Note 4, the two spectra, measured with a commercial optical spectrum analyzer, are separated by 6.6 THz. Similar spectra are obtained for EO-Comb source2. When the signals of EO-Comb source1 and EO-Comb source2 beat on the fast photodetector, the dual-comb spectrum (of a free spectral range of fRF1/2) contains two RF combs, one centered at δf1 and the other centered at δf2. They both have a line spacing of (fRF2- fRF1), and they are not expected to be mutually coherent. The comb centered at δf1 reports on the absorption and dispersion experienced by the sample in the region of the optical frequency f1, while the comb centered at δf2 corresponds to optical frequencies around f2. The optical frequencies f1 and f2 can be adjusted independently.

Computation of reference spectra using literature data

The acetylene computed transmittance spectrum (Fig. 3a) is calculated using the simulation tool on “HITRAN on the web”43, which takes its line parameters in the HITRAN database29. Lorentzian line profiles are chosen. The computed dispersion spectrum (Fig. 3b) is derived from the calculated transmittance spectrum using the Kramers–Kronig relations44.

Data availability

The data that support the plots of this paper and other findings within this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

No original algorithms or codes have been developed for this article. The MATLAB program used for processing the data is nevertheless available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, Z., Albrow-Owen, T., Cai, W. & Hasan, T. Miniaturization of optical spectrometers. Science 371, eabe0722 (2021).

Pohl, D. et al. An integrated broadband spectrometer on thin-film lithium niobate. Nat. Photonics 14, 24–29 (2020).

le Coarer, E. et al. Wavelength-scale stationary-wave integrated Fourier-transform spectrometry. Nat. Photonics 1, 473–478 (2007).

Nie, X., Ryckeboer, E., Roelkens, G. & Baets, R. CMOS-compatible broadband co-propagative stationary Fourier transform spectrometer integrated on a silicon nitride photonics platform. Opt. Express 25, A409–A418 (2017).

Kita, D. M. et al. High-performance and scalable on-chip digital Fourier transform spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 4405 (2018).

Redding, B., Liew, S. F., Sarma, R. & Cao, H. Compact spectrometer based on a disordered photonic chip. Nat. Photonics 7, 746–751 (2013).

Faraji-Dana, M. et al. Compact folded metasurface spectrometer. Nat. Commun. 9, 4196 (2018).

Picqué, N. & Hänsch, T. W. Frequency comb spectroscopy. Nat. Photonics 13, 146–157 (2019).

Griffiths, P. R. & De Haseth, J. A. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. 2nd edn, (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2007).

Suh, M. G., Yang, Q. F., Yang, K. Y., Yi, X. & Vahala, K. J. Microresonator soliton dual-comb spectroscopy. Science 354, 600–603 (2016).

Dutt, A. et al. On-chip dual-comb source for spectroscopy. Sci. Adv. 4, e1701858 (2018).

Yu, M. et al. Silicon-chip-based mid-infrared dual-comb spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 1869 (2018).

Pavlov, N. G. et al. Soliton dual frequency combs in crystalline microresonators. Opt. Lett. 42, 514–517 (2017).

Villares, G., Hugi, A., Blaser, S. & Faist, J. Dual-comb spectroscopy based on quantum-cascade-laser frequency combs. Nat. Commun. 5, 5192 (2014).

Scalari, G., Faist, J. & Picqué, N. On-chip mid-infrared and THz frequency combs for spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 150401 (2019).

Van Gasse, K. et al. An on-chip III-V-semiconductor-on-silicon laser frequency comb for gas-phase molecular spectroscopy in real-time. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.15113 (2020).

Shen, B. et al. Integrated turnkey soliton microcombs. Nature 582, 365–369 (2020).

Yu, M. et al. Gas-phase microresonator-based comb spectroscopy without an external pump laser. ACS Photonics 5, 2780–2785 (2018).

Lin, T. et al. Broadband ultrahigh-resolution chip-scale scanning soliton dual-comb spectroscopy. arXiv preprint arXiv 2001.00869, (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. Broadband electro-optic frequency comb generation in a lithium niobate microring resonator. Nature 568, 373–377 (2019).

Jiang, Z., Huang, C.-B., Leaird, D. E. & Weiner, A. M. Optical arbitrary waveform processing of more than 100 spectral comb lines. Nat. Photonics 1, 463–467 (2007).

Carlson, D. R. et al. Ultrafast electro-optic light with subcycle control. Science 361, 1358–1363 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101–104 (2018).

Ho, K. & Kahn, J. M. Optical frequency comb generator using phase modulation in amplified circulating loop. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 5, 721–725 (1993).

Kourogi, M., Nakagawa, K. & Ohtsu, M. Wide-span optical frequency comb generator for accurate optical frequency difference measurement. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 29, 2693–2701 (1993).

Rueda, A., Sedlmeir, F., Kumari, M., Leuchs, G. & Schwefel, H. G. L. Resonant electro-optic frequency comb. Nature 568, 378–381 (2019).

Long, D. A. et al. Multiheterodyne spectroscopy with optical frequency combs generated from a continuous-wave laser. Opt. Lett. 39, 2688–2690 (2014).

Millot, G. et al. Frequency-agile dual-comb spectroscopy. Nat. Photonics 10, 27–30 (2016).

Gordon, I. E. et al. The HITRAN2016 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 203, 3–69 (2017).

Huh, J. H., Chen, Z., Vicentini, E., Hänsch, T. W. & Picqué, N. Time-resolved dual-comb spectroscopy with a single electro-optic modulator. arXiv preprint arXiv 2105.06527 (2021).

Hu, Y., Reimer, C., Shams-Ansari, A., Zhang, M. & Loncar, M. Realization of high-dimensional frequency crystals in electro-optic microcombs. Optica 7, 1189–1194 (2020).

Lambert, N., Trainor, L. & Schwefel, H. An ultra-stable microresonator-based electro-optic dual frequency comb. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2108.11140, (2021).

Zhang, M., Wang, C., Cheng, R., Shams-Ansari, A. & Lončar, M. Monolithic ultra-high-Q lithium niobate microring resonator. Optica 4, 1536–1537 (2017).

Buscaino, B., Zhang, M., Lončar, M. & Kahn, J. M. Design of efficient resonator-enhanced electro-optic frequency comb generators. J. Lightwave Technol. 38, 1400–1413 (2020).

Desiatov, B., Shams-Ansari, A., Zhang, M., Wang, C. & Lončar, M. Ultra-low-loss integrated visible photonics using thin-film lithium niobate. Optica 6, 380–384 (2019).

Shao, L. et al. Microwave-to-optical conversion using lithium niobate thin-film acoustic resonators. Optica 6, 1498–1505 (2019).

McKenna, T. P. et al. Cryogenic microwave-to-optical conversion using a triply resonant lithium-niobate-on-sapphire transducer. Optica 7, 1737–1745 (2020).

Cai, L. et al. Acousto-optical modulation of thin film lithium niobate waveguide devices. Photon. Res. 7, 1003–1013 (2019).

Ren, T. et al. An integrated low-voltage broadband lithium niobate phase modulator. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 31, 889–892 (2019).

Jankowski, M. et al. Ultrabroadband nonlinear optics in nanophotonic periodically poled lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 7, 40–46 (2020).

Okawachi, Y. et al. Chip-based self-referencing using integrated lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 7, 702–707 (2020).

Luke, K. et al. Wafer-scale low-loss lithium niobate photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Express 28, 24452–24458 (2020).

Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, V. E. Z. I. o. A. O., National Research Tomsk State University. Hitran on the web, http://hitran.iao.ru/.

Sheik-Bahae, M. Nonlinear optics basics. Kramers-Kronig relations in nonlinear optics. Encyclopedia Mod. Opt. 234–239 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0123693950007491?via%3Dihub (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Edward Ackerman (Photonicsystems) and Dr. Yoshitomo Okawachi (Columbia University) for help with the experiment. Funding: This work is supported in part by Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR; award number of FA9550–19-1–0310), National Science Foundation (NSF PFI-TT; award number of IIP-1827720), Defense Advanced Projects Agency (DARPA; W31P4Q-15-1-0013), the Max-Planck Society and by the Max-Planck Harvard Research Center for Quantum Optics. Device Fabrication is performed at the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems, a member of National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (award number of ECCS-1541959).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S.-A., designed the devices with help from M.Z. and C.R. A.S.-A. fabricated the devices. M.Y. designed and set-up the thermo-electrically-controlled frequency comb generator. N.P. proposed the concept of spectrally-tailored dual-comb spectroscopy. N.P, Z.C., and M.Y. designed the dual-comb experiment. M.Z. proposed the concept of the microrings with drop port. M.Y., A.S.-A., and Z.C. carried out the measurements with help from C.R. Data analysis was performed by Z.C. with help from A.S.-A., and M.Y., guided by N.P. A.S.-A., Z.C., and M.Y. prepared the figures. N.P., A.S.-A., M.Y., and Z.C. drafted the manuscript that was discussed and improved by all co-authors. N.P. and M.L. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.Z., C.R., and M.L., are involved in developing lithium niobate technologies at Hyperlight corporation; A.S.-A., M.Y, Z.C., N.P. declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shams-Ansari, A., Yu, M., Chen, Z. et al. Thin-film lithium-niobate electro-optic platform for spectrally tailored dual-comb spectroscopy. Commun Phys 5, 88 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00865-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00865-8

This article is cited by

-

Photonics-integrated terahertz transmission lines

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Integrated bionic LiDAR for adaptive 4D machine vision

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Practical GHz single-cavity all-fiber dual-comb laser for high-speed spectroscopy

Light: Science & Applications (2025)

-

Scalable miniature on-chip Fourier transform spectrometer for Raman spectroscopy

Light: Science & Applications (2025)

-

Interdisciplinary advances in microcombs: bridging physics and information technology

eLight (2024)