Abstract

The clogging phenomenon finds extensive application in both industrial processes and daily life events. While this broad spectrum of application motivated extensive research to identify the general factors underlying the clogging mechanism, it results in a fragmented and system-specific understanding of the entire clogging process. Therefore, it is essential to establish a holistic understanding of all contributing factors of clogging based on the microscopic physical mechanisms. In this paper, we experimentally investigate clogging of granular materials in a two-dimensional hopper flow and present a self-consistent physical mechanism of clogging based on precursory chain structures. These chain structures follow a specific modified restricted random walk, and clogging occurs when they are mechanically stable enough to withstand the flow fluctuations. We introduce a single-particle model that can explain the arch-forming probability. Our results provide insight into the microscopic mechanism behind clogging and a broader understanding of the dynamics of dense granular flow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The clogging of granular flow in silos or hoppers is ubiquitous and closely related to many industrial processes such as the transportation of granular materials in pipelines1, as well as daily life events like traffic jams2,3. Previous studies, both theoretical and experimental, have investigated the influencing factors on the clogging process, such as outlet size4,5 and shape6,7, particle shape8 and friction9, external mechanical agitation10,11 and presence of obstacles above the outlet12,13,14.

A hallmark feature of clogging is the formation of an arch near the outlet15, which can withstand stress induced by particles above16. To et al. 15,17,18 developed a restricted random walk model (RRWM) to describe a strict convex shape of the arch, by which they successfully reproduced the clogging probabilities at different outlet sizes. This model only yields a geometric understanding of the arch structure without explaining its dynamical origin. To understand the frequency of a clogging event and the avalanche statistics, refs. 19,20 proposed an empirical Poisson process model, where they introduce a single particle probability p for each particle flowing out the orifice without forming an arch based on the exponential distribution of avalanche size. Nevertheless, it is difficult to reconcile this single-particle model with the cooperative nature of the arch-forming process as suggested by ref. 15. Later, ref. 21 suggested that clogging happens by the occurrence of certain multiple-particle clogging configurations, with the clogging probability determined by the ratio between these clogging configurations with their full configuration space. However, the nature of the configuration space and the multi-particle configuration remains elusive. Moreover, it is found that the flow speed can also strongly affect clogging. Through an innovative silo discharge setup where the flow rate is controlled by a conveyor belt22, it is observed that clogging probability can be empirically decomposed into two independent terms with one depending on outlet geometry and the other on particle kinematics. While these studies have successfully elucidated specific aspects of the clogging phenomenon, the microscopic mechanism for clogging and how it is influenced by multiple factors are still not yet well understood18,20,23.

It should be noted that arch-like structures are already observed in dense granular flows due to the coexistence of solid- and liquid-like phases1. When these structures flow through constrictions, they have the potential to transform into static arches, consequently arresting the flow. To develop a holistic understanding of the clogging phenomenon, it is, therefore, necessary to identify these structures in the flow and also investigate the microscopic processes of how these structures transform into arches under the influence of all contributing factors, including the arch geometric structure, the clogging probability of a multiple-particle configuration, and the flow speed.

In this article, we experimentally investigated the clogging process of grains in a two-dimensional hopper and revealed that clogging happens due to the formation of some precursory chain structures in the flow. These chains induce clogging when they are mechanically stable enough to withstand the stress imposed from above. We further investigate the geometric structure and dynamic stability of these chains at different outlet sizes and flow speeds. We find that clogging can be decomposed into two distinctive processes: chain formation, governed by outlet size and the particle contact geometrical structures, and its subsequent transformation into an arch, controlled by the configuration evolution associated with flow speed. Finally, we present an analytic expression for the clogging probability, which accurately reproduces our experimental results.

Results

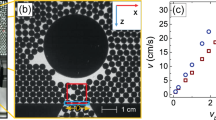

Our experimental granular system is a monolayer of bi-disperse disks flowing through the outlet in a quasi-two-dimensional hopper, shown schematically in Fig. 1a. The disks are injected from above, and as the particles flow, arch structures form at the outlet over time, eventually leading to clogging. Following a clogging event, we use a rod to gently perturb the arch at the outlet with very minor perturbations to restart the flow. By increasing the outlet widths, we collect a series of statistics on the discharge flux between two clogging events. Figure 1b shows the complementary cumulative distribution of the avalanche size s. This distribution shows exponential behavior for all outlet widths D. Since the occurrence of a clogging event is accompanied by an arch-forming above the outlet, the clogging probability \({P}_{c}=1/\langle s\rangle\) can be defined as the probability of forming an arch after an average outflow of \(\langle s\rangle\) particles. Figure 1c shows that \({P}_{c}\) decreases quickly with the increase of D/d. This finding is consistent with previous works where \({P}_{c}\) has been fitted with various forms5,7,20,24.

a Schematic of the experimental setup. The high-speed camera images the area within the red frame and chain structures are analyzed in the red dashed trapezoidal region. \({\theta }_{h}=45{^{\circ }}\) is the hopper opening angle. Inset: raw images for the formation, evolution, and breaking processes (about 0.02 s) of a 5-particle chain (marked with red circles) at D = 3.49d. The scale bar corresponds to 50 mm. b Complementary cumulative distribution of the avalanche size s for different D. c Experimentally obtained clogging probability \({P}_{c}\) (black dots) as a function of D/d and the corresponding theoretical results from Eq. (5) (red line). The dashed curve is the empirical fitting using \({P}_{c}=\exp [C{(D/d)}^{2}]\). In this study, each data point corresponds to the mean value of five independent measurements for clogging experiments. The error bars represent the standard deviations. The calculation method for all figures with error bars is the same.

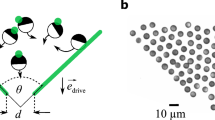

The geometric rules of chain structures and their formation in the flow

To understand the nature of clogging and its associated phenomena in our experiment, it is essential to carry out a thorough investigation into the microscopic mechanisms that govern the formation of arches at the hopper outlet. We note that before a clogging event, transient arch-like structures already exist in the flow, which we denote as chain. These chains demonstrate a certain degree of mechanical rigidity and continuously form and disintegrate throughout the flow process [inset of Fig. 1a]. We note that when a chain forms at the outlet with both ends in contact with the hopper boundary and possesses sufficient stability to withstand the flow impact, it transforms into an arch, ultimately resulting in the arrest of the flow. We first identify the flowing chain structures in the system. These chains are defined based on the geometrical features of clogged arches. By doing so, we can systematically exclude mechanically unstable structures in the flow, thereby facilitate the identification of stable ones that potentially contributes to the clogging process. We characterize the geometry of the arch structures by examining the angle \({\theta }_{i}\) (\(i=1,{{{{\mathrm{..}}}}}.,n-1\)) formed by the vector connecting the centroid of the \({i}_{th}\) particle and the \({(i+1)}_{th}\) particle with respect to the horizontal direction [inset of Fig. 2a]. Here \({\theta }_{0}=45{^{\circ }}\) and \({\theta }_{n}=-45{^{\circ }}\), as we treat the hopper boundaries as virtual supporting particles25. The probability distribution functions (PDFs) of \(\theta\) for arches are shown in Fig. 2a. In our case, the presence of friction can lead to some local “defects”26,27, deviating from the idealized behavior of RRWM for frictionless particles15, in which \({\theta }_{i}\) satisfy the strict decreasing trend. Therefore, the geometric rule of an arch can be relaxed to \({\theta }_{i}+\delta \theta \, > \, {\theta }_{i+1}\), where \(\delta \theta\) characterizes those defects. Additionally, we find \({\theta }_{i} \, > \, {\theta }_{i+2}\)27, which ensures that an arch is globally convex to be mechanically stable. Equivalently, these two rules can also be described by the angle between the two neighbors of a central particle, \({\phi }_{i}=180{^{\circ }}+({\theta }_{i}-{\theta }_{i-1})\) [inset of Fig. 2a], and they are now transformed into \({\phi }_{i} \, < \, 180{^{\circ }}+\delta \theta\) and \(({\phi }_{i}+{\phi }_{i+1})/2\le 180{^{\circ }}\), where we denote \(({\phi }_{i}+{\phi }_{i+1})/2\) as \({\alpha }_{i}\) for simplify.

a PDFs of \({\theta }_{i}\) (from right to the left, i = 1, 2, …, 5) for arches consisting of 6 particles. Inset: schematic diagram of a chain structure. b The correlation between \({\phi }_{i}\) and \({\phi }_{i+k}\) within an arch of different n at D/d = 3.8. The straight line corresponds to \(C(k)=0\). c The number of identified arches (red triangle) and chains (blue circle) as a function of \(\delta \theta\). Inset: PDF of \(\delta \theta\) at different D. The black dash line represents the threshold at \(\delta \theta =20^{\circ}\). d PDFs of \({\phi }_{i}\) for chains (triangle) and arches (square) at D = 3.49d. Inset: PDFs of \({\alpha }_{i}\) for chains (triangle) and arches (square) at the same D.

We note that these rules are mathematically sufficient in defining arch structure as the correlation of \(\phi\) only extends to its neighbors. The correlation of \(\phi\) within an arch can be measured using \(C(k)=\frac{\langle ({\phi }_{i}-{\bar{\phi }}_{i})({\phi }_{i+k}-{\bar{\phi }}_{i+k})\rangle }{{{\sigma }_{\phi }}^{2}}\), where k represents the \({k}_{th}\) nearest neighbors of the \({i}_{th}\) particle within the arch, \(\bar{\phi }\) and \({{\sigma }_{\phi }}^{2}\) denote the respective average value and variance of \(\phi\), and \(\langle \cdots \rangle\) indicates the average over all chains. As shown in Fig. 2b, a strong inverse correlation is observed concerning the nearest neighboring \(\phi\). However, when considering \(\phi\) correlations at greater distances, \(C(k)\) fluctuates around zero, indicating that, although the correlation is not Markovian, it decays very fast. Therefore, there is no necessity to account for the correlations of \(\phi\) for \(k > 2\).

Subsequently, we define a chain as a linear contacting structure that satisfies the same geometric rules specified for an arch structure, i.e., \({\phi }_{i} < 180{^{\circ }}+\delta \theta\) and \({\alpha }_{i}\le 180{^{\circ }}\), with both ends making contact with the hopper boundaries when the system is still flowing [Inset of Fig. 1a]. The inset of Fig. 2c shows the PDF of \(\delta \theta\) for real arch structures at different D. We systematically vary the value of \(\delta \theta\) from \(0{^{\circ }}\) to \(40{^{\circ }}\) and calculate the corresponding number of discovered arches and chains in all experiments with D/d = 3.49. Figure 2c demonstrates a rapid linear increase in the number of correctly identified arches with the increasing \(\delta \theta\) when \(\delta \theta \le 20{^{\circ }}\), followed by a gradual saturation of arch number identified as \(\delta \theta\) further increases. Nevertheless, the number of chains still increases linearly. Given the saturation of identified arch structures and the significant computational demands associated with the sharp rise in chain numbers beyond \(\delta \theta =20{^{\circ }}\), we set \(\delta \theta =20{^{\circ }}\) in our specific case to ensure that the above two rules encompass more than 90% of the arch structures and are strong enough to exclude many chains that are unlikely to contribute to the arching process. We display the PDFs of \(\phi\) and \(\alpha\) for the identified chains and arches in Fig. 2d and its inset. Note that \(P(\phi )\) of chains is significantly wider than that of arches, although both exhibit a most probable value about \(165{^{\circ }}\). This disparity arises from the varying probabilities of different configuration chains transforming into arches.

Upon identifying chain configurations, we can obtain the chain-forming probability \({p}_{chain}\) by calculating the ratio of the number of chains to the particles that flow through the outlet. It turns out that \({p}_{chain}\) is determined by both particle contact geometry and outlet truncation effect, and independent of the flow speed v [Fig. 3a]. Here v represents the instantaneous vertical velocity of grains in the vicinity of the outlet region (within a 4d distance above the outlet) [Supplementary Fig. S2]. As shown in Fig. 3b, the probability of forming an n-particle chain at different outlet sizes demonstrates the same exponential decay at large n, \({p}_{chain}(n) \sim {p}^{n}\) [the dashed line in Fig. 3b], suggesting a constant probability \(p=0.36\) for a chain to extend by one additional particle at its ends28. We can explain the origin of this constant by considering the geometric features of particle contacts. We simply assume that particle configurations with various \(\phi\) values are uniformly distributed within the system without any geometric constraints. After imposing the geometric rules, they subsequently adopt the identified \(P(\phi )\) of chains, as shown in Fig. 2d. Note that the configuration of \(\phi =165{^{\circ }}\) is the most probable configuration proposed by our theoretical model (particles with \(\phi =165{^{\circ }}\) always satisfy the geometric rules). Therefore, the value of p can be calculated by the area of the shaded region that represents the distribution of remaining particle configurations, \(\frac{1}{{\phi }_{upper}-{\phi }_{lower}}{\int }_{{\phi }_{lower}}^{{\phi }_{upper}}P(\phi )d\phi\), see Fig. 3c. The lower boundary \({\phi }_{lower}\) occurs when two small disks are in contact with a central large disk [inset of Fig. 3c], which is 49.4°. While the experimentally observed non-zero \(P(\phi )\) only occurs after 57°, p can therefore be calculated by: \(\frac{1}{200{^{\circ }}-57{^{\circ }}}{\int }_{57{^{\circ }}}^{200{^{\circ }}}P(\phi )d\phi =0.36\).

a \({p}_{chain}\) as a function of the average flow speed v for different D. b Chain-forming probability \({p}_{chain}\) for n-particle chains at different D. The dashed line is the empirical fitting of \({g}_{0}{p}^{n}\). Inset: experimentally obtained \({p}_{chain}\) (dots) and the corresponding theoretical prediction (curve) as a function of D. c Schematic diagram of the process for estimating p. The black solid line represents a uniform distribution of contact configurations without taking their geometric rules into account. The distribution formed by the blue-shaded region represents the ratio of remaining chains after considering the rules. The horizontal line is \(P(\phi )=1/(200-49.4)\) and the vertical line is \(\phi =49.4{^{\circ }}\). Inset: schematic diagram illustrating the contact configuration with the minimum \(\phi\) that three particles can form within a bi-disperse system. d Experimentally obtained PDFs \({a}_{n}(x)\) for a chain with n particles to have a horizontal projection length x (n = 4 to n = 9). Solid curves are results given by the polygon model. Inset: schematic diagram of the polygon model.

Note that the sudden decrease of \({p}_{chain}(n)\) for small-n configurations is due to the truncation of the outlet width since a chain is defined to make contacts with both boundaries. To gain a simple theoretical understanding of this truncation effect, we suggest that the most probable chain configuration that n particles can form is part of a regular polygonal structure. In this configuration, \(\phi\) of each interior particle is the same, and the base angles on the left and right sides are \(90{^{\circ }}-{\theta }_{h}=45{^{\circ }}\) [inset of Fig. 3d], where \({\theta }_{h}\) is the hopper opening angle. Therefore,\(\phi =180{^{\circ }}-2(90{^{\circ }}-{\theta }_{h})/n\). \(\phi\) ranges from \(162{^{\circ }}\) to \(167{^{\circ }}\) for n = 5–7, which is consistent with the experimentally observed mean value of \(\phi\) being around \(165{^{\circ }}\) since n = 5–7 chains are most common at different D. Real chains fluctuate around this mean structure, with the standard deviation of \({\theta }_{i}\) being \({\sigma }_{{\theta }_{i}}\) = 28.3°. Subsequently, we empirically apply a truncated Gaussian distribution to approximate the PDF \({a}_{n}(x)\) for a chain with n particles having a horizontal projection length x greater than the outlet size \(D/d-\sqrt{2}/2\) (\(\sqrt{2}/2\) comes from the contribution of two boundary particles) with average value \({x}_{n}={\sum }_{i=1}^{n-1}\cos {\theta }_{i}\) and variance \({\sigma }_{{x}_{n}}^{2}={\sum }_{i=1}^{n-1}{\sin }^{2}{\theta }_{i}\cdot {\sigma }_{{\theta }_{i}}^{2}\). This simple model accurately captures the behavior of experimentally observed \({a}_{n}(x)\) at D = 3.49d, see Fig. 3d. Using this model, the chain-forming probability is \({p}_{chain}={\sum }_{n=3}^{\infty }{g}_{0}{p}^{n}{\int }_{D/d-\sqrt{2}/2}^{\infty }{a}_{n}(x)dx\), where \({g}_{0}=27.4\) is an empirical fitting parameter. As shown in the inset of Fig. 3b, the theoretically calculated \({p}_{chain}\) are consistent with the experimental results. Note that when D/d > 4, there still exist chains composed of four particles due to bidispersity.

Dynamics of chain structures and their subsequent transformation into arches

To better understand why not all chains can transform into arches, we note that chains are dynamic structures. Clogging can only happen when a chain maintains the geometric constraints specified for arches longer than the stopping time required to halt the flow. This helps explain why chains with large \(\phi\) and \(\alpha\) are less likely to form arches as they are more likely to evolve across the geometric constraints within this period. Note that we experimentally confirm that 40% of the chains break when \(\phi\) evolves exceeding \(200{^{\circ }}\), 49% at the location with \(\alpha > 180{^{\circ }}\), and 10% where both \(\phi > 200{^{\circ }}\) and \(\alpha > 180{^{\circ }}\). This naturally prompts us to analyze the dynamic evolution of chain structures over time. The rotational mean-squared displacement (rMSD) of \(\phi\) associated with each particle is:

where N averages over all possible chains, irrespective of the number of particles they consist of. Figure 4a shows that \(\langle {\phi }^{2}(t)\rangle \sim {t}^{2}\), which suggests that \(\phi\) evolves linearly as a function of ton short time scales. This contrasts with the sub-diffusive behavior of \(\phi\) when a stagnant arch is vibrated11,29. We calculate the angular speed \(\dot{\phi }=\frac{\phi (t+\varDelta t)-\phi (t)}{\varDelta t}\) with \(\varDelta t=0.002s\), and find that its standard derivation \(\sigma (\dot{\phi })\) satisfies a linear relation with v: \(\sigma (\dot{\phi })=0.14v+1.24\), see Fig. 4b. The non-zero value of \(\sigma (\dot{\phi })\) as v tends to zero implies that the chain structure can still undergo structural rearrangement. This is consistent with the observation in ref. 22. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4c, \(\phi\) and \(\dot{\phi }/\sigma (\dot{\phi })\) for all outlet widths empirically satisfy a universal joint Gaussian distribution with a covariance dependent on \(\phi\):

where \(\overline{\dot{\phi }}/\sigma (\dot{\phi })=0.025\phi -4\) for all outlet widths. The linear evolution of \(\phi\) and the corresponding \(P(\dot{\phi },\phi )\) provide a basis for the further derivation of the structural evolution of chains. Note that the influence of neighboring disks needs to be considered due to the strong correlation existing between the nearest neighboring \(\phi\), as mentioned previously.

a The rMSD for chain structures as a function of \(t\) at D = 3.49d. The black dash line is a guide for eye with rMSD\(\sim {t}^{2}\). b Standard derivation \(\sigma (\dot{\phi })\) as a function of v, which satisfies the same linear relation for all D. c Universal joint probability density distribution \(P(\dot{\phi }/\sigma (\dot{\phi }),\phi )\) for all D. The relation between the rescaled \(\overline{\dot{\phi }}\) and \(\phi\) can be collapsed onto a single curve for all D. d Single-particle probability of a chain transforming into an arch \({p}_{s}(v)\) as a function of v at D = 4.5d. Solid curve is the result of the theoretical model. Inset: Multiple-particle probability of a chain transforming into an arch \({p}_{a/c}(v,n)={p}_{s}{(v)}^{n}\) as a function of v at D = 4.5d.

Now, we can theoretically calculate the probability of a chain transforming into an arch with a simple model based on the microstates of single particle in the chain. Specifically, each particle in a chain can be considered to be in the phase space composed of \(\phi\) and \(\dot{\phi }\). We start with the configuration of a single particle \({\phi }_{1}\) and its nearest neighbor \({\phi }_{2}\) within a chain. We randomly sample \({\phi }_{1}\in [100{^{\circ }},200{^{\circ }} \, \, ]\) of disk 1 from \(P(\phi )\), along with its initial angular speed \({\dot{\phi }}_{1}\) from \(P(\dot{\phi })\). Since \(\phi\) evolves linearly in a short time, \({\phi }_{1}\) evolves to \({\phi {\prime} }_{1}={\phi }_{1}+{\dot{\phi }}_{1}\delta t\) after a characteristic stopping time \(\delta t\). Thus, we can determine the lower and upper limits of \({\dot{\phi }}_{1}\) for chains eventually transforming into clogged arches. \({\dot{\phi }}_{1lower}=(100-{\phi }_{1})/\delta t\) and \({\dot{\phi }}_{1upper}=(200-{\phi }_{1})/\delta t\) as these chains should maintain the arch configurations \({\phi }_{1}^{{\prime} }\in [100{^{\circ }},200{^{\circ }} \, \, ]\). In addition, to satisfy the nearest neighbor constraint in defining a chain, \(\alpha {\prime} =({\phi }_{1}^{{\prime} }+{\phi }_{2})/2\) must be within \([125{^{\circ }},180{^{\circ }} \, \, ]\), where \({\phi }_{2}\) is the angle of the neighboring grain which also satisfies \(P(\phi )\). This implies that the lower and upper limits for \({\phi }_{2}\) is \({\phi }_{2lower}=\,\max (100,250-{\phi }_{1}^{{\prime} })\) and \({\phi }_{2{{{upper}}}}=\,\min (200,360-{\phi }_{1}^{{\prime} })\). When \({\phi }_{1}^{{\prime} }\) is fixed, the probability that \({\phi }_{2}\) is within these limits is:

Eventually, the single-particle probability \({p}_{s}(v)\) of a chain transforming into an arch can be calculated as:

Here \(A={\int }_{{\phi }_{0lower}}^{{\phi }_{0upper}}P({\phi }_{2})d{\phi }_{2}\cdot {\int }_{{\phi }_{1lower}}^{{\phi }_{1upper}}P({\phi }_{1})d{\phi }_{1}\) is the normalization factor because the chain structures are defined when \({\phi }_{1,2}\in [100{^{\circ }},200{^{\circ }} \, \, ]\) and \(\alpha \in [125{^{\circ }},180{^{\circ }} \, \, ]\). The stopping time \(\delta t=0.018{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) here is an empirically fitted value which enables the theoretical results to best match experimental observations for different outlet widths. Within this timescale, chain particles can only move about 0.1d. This finding is consistent with the observations in previous studies that the load-bearing structures in granular flows are transient rather than enduring over relatively long durations during flow30. We calculate this triple integral numerically since it is difficult to reach an analytical solution. Specifically, \({p}_{s}(v)\) decreases monotonically with increasing \(v\), and asymptotes to a non-unity value as v approaches zero. This model can therefore explain the significant influence of flow speed on the clogging process, as observed in recent studies22,31.

For a chain consisting of n particles, we simply assume that its probability of transforming into an arch is \({p}_{a/c}(v)={p}_{s}{(v)}^{n}\). To validate this assumption, we calculate both \({p}_{s}(v)\) and \({p}_{a/c}(v)\) at D = 4.5d as a function of flow speed v based on the experimental data [symbols in Fig. 4d and its inset respectively]. The experimentally observed \({p}_{s}(v)\) for chains of length n collapse onto the same curve. This universal behavior of \({p}_{s}(v)\), regardless of the chain structure and outlet width, suggests that this quantity can be analyzed on the single particle level and indeed only depends on v. The experimentally obtained \({p}_{s}(v)\) also exhibits excellent agreement with the numerical results, confirming the validity of our model.

The clogging probability

By examining the formation and subsequent transformation of the chain structures, it is therefore possible to obtain the clogging probability quantitatively. The clogging probability \({P}_{c}\) can be decomposed as the product of two terms: \({p}_{chain}\) is the chain-forming probability and \({p}_{a/c}\) is the probability of a chain transforming into an arch. The first term \({p}_{chain}\) relies solely on the outlet shape and the particle contact geometry, while \({p}_{a/c}\) only depends on the flow speed. Considering the varying flow speed in granular hopper flow, the probability of forming an arch \({P}_{c}\) in this context can be mathematically expressed as:

where \({p}_{a/c}(v)\) is the conditional clogging probability at flow speed \(v\) and \(P(v)\) is the PDF of the flow speed v [Supplementary Fig. S2a]. In Fig. 1c, the theoretically obtained \({P}_{c}\) based on Eq. (5), which incorporates the influence of outlet size, friction, and flow speed, agrees very well with the experimentally measured results. Furthermore, Eq. (5) also yields theoretical results of the PDF of the number of particles n contained in the arch, which also agree nicely with the experimental results [Supplementary Fig. S3].

Our theoretical model also provides a natural explanation for the observed empirical exponential decay in \({P}_{c}=\exp [-C{(D/d)}^{2}]\) with respect to \({D}^{2}\), reported in both experimental and simulation works5,7,20,24, as a consequence of the combined effect of both dynamics and structure. Specifically, \({p}_{s}(v)\) demonstrates exponential decay with increasing flow speed v [see Fig. 4d], and the average flow speed \(\bar{v}\) shows a clear linear dependence on D/d [Supplementary Fig. S2b], which signifies a decrease in the probability of a single particle maintaining its mechanically stable configuration. Meanwhile, the average length \(\bar{n}\) of arches depends linearly on D/d [Supplementary Fig. S3b], indicating an augmentation in the number of particles required to form an arch at large outlet sizes. The combined effects ultimately lead to a rapid decrease in the clogging probability with the form of \({P}_{c} \sim {p}_{s}{(\bar{v})}^{\bar{n}} \sim \exp [-{(D/d)}^{2}]\), where \({p}_{s}(\bar{v}) \sim \exp [-(D/d)]\). Therefore, the clogging probability significantly decreases but does not reach zero as the outlet size increases. These findings suggest that clogging can, in principle, occur for arbitrarily large outlet sizes, without a critical threshold beyond which clogging disappears.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a microscopic framework elucidating the physical mechanism behind the clogging phenomenon in gravity-driven granular hopper flow by introducing specific chain structures within the flow. These chain structures continuously form and disintegrate during the flow process, with their structural evolution closely related to the flow speed. By considering the formation and mechanical stability of these chains, we have gained a deeper understanding of the dynamic origin behind the formation of arch structures during clogging events. This approach seamlessly integrates previous studies on clogging statistics, arch structure, and velocity dependency, and provides a holistic perspective. We also derive an analytical expression for the clogging probability, which successfully reproduces our experimental results. Our work has convincingly explained the clogging phenomenon and established a general framework for any future investigation in this field.

Additionally, our work has implications for the understanding of dense granular flows, as similar rigid clusters have been previously identified in experimental studies32. These clusters are considered as solid-like components in the flow which exhibits mechanical rigidity and can resist external stress, thus modifying the rheological properties of granular materials. Traditionally, these solid-like components have been attributed to linear force chain structures as observed in photoelastic experiments33,34,35. However, similar to our case, the presence of gravity results in the formation of force-bearing structures that are always arch-like. These structures, originating from the joined effect of structural heterogeneity and gravity, demonstrate the unique force-bearing structures in granular media under gravity, which are unlike those observed in the absent of gravity. Understanding these specific structures is therefore vital for comprehending the influence of gravity on the rheological behaviors of dense granular flows.

Moreover, our results can be extended to three-dimensional (3D) cases. While the mechanically stable structures are linear configurations in our 2D systems, they form more complex dome-like structures in 3D systems. Systematic characterizations of complex bridge/dome structures have been developed based on tetrahedral structures, which serve as the 3D counterpart of triangles in 2D36,37,38. It is worth noting that despite the dimension difference, the load-bearing structures in 2D and 3D share similar characteristics. Therefore, there exists in principle no technical difficulty in generalizing the conclusion of our study to the 3D case.

Furthermore, our results can carry significant implications for the control of granular flows and various similar systems such as traffic flows and crowd dynamics. The presence of solid-like components in the flow process is pivotal to the occurrence of clogging phenomena. Strategies aimed at reducing the stability of these “rigid” clusters, such as enhancing flow, or disrupting existing structures like incorporating obstacles may prove effective in preventing clogging.

Methods

Experimental details

Our experimental setup consists of a quasi-two-dimensional hopper with dimension of \(100{{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}}(H)\times 40{{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}}(W)\), constructed using two transparent acrylic plates [Fig. 1a]. These plates are separated by two aluminum strips along the boundary, creating a 6 mm gap between them. To form the hopper outlet, two movable aluminum bars are used, which are inclined at an angle of \(45{^{\circ }}\) with respect to the side walls. The outlet width D can be continuously adjusted by raising or lowering the side bars. For our experiment, D ranges from 2.5d to 4.8d. To ensure a two-dimensional particle flow, we use bi-disperse acrylic disks with a thickness of 5 mm and diameters of 8 mm and 11.2 mm. The average particle diameter, denoted as d, is 9.6 mm. These disks are laser-cut from smooth acrylic glass plates, minimizing friction interactions with the front and back plates. Before being fed into the hopper, particles are uniformly mixed with a number ratio of 2:1 to achieve roughly equal area fractions. When a clogging event happens, we use a rod to lightly poke the arch at the outlet to restart the flow. The rod is quickly removed to avoid interfering with the flow. To capture the full dynamic process between two clogging events, we employ a high-speed camera (Photron FASTCAM SA5) that records images at a rate of 500 frames per second. The imaging area is about \(30\times 30c{m}^{2}\) which covers the outlet and the region above it, and only disks within a 4d distance from the outlet are analyzed in our experiment since experimentally no arch can form above this height, see Fig. 1a. For better statistics, the clogging process is repeated ~700 times for each outlet width. Following the image processing procedures and tracking algorithms of our previous study39,40, we can obtain the centroid coordinates and trajectories of disks with an uncertainty less than \(3.1\times {10}^{-3}{d}\). Technical details of our implementation of the image processing, particle tracking algorithm, and contact detection are provided in Supplementary Note 1.

Data availability

All data that support the plots within this paper are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Duran J. Sands, Powders, and Grains: An Introduction to the Physics of Granular Materials (Springer, New York, 2000).

Helbing, D. Traffic and related self-driven many-particle systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 1067–1141 (2001).

Schadschneider, A. Traffic flow: a statistical physics point of view. Phys. A 313, 153 (2002).

Masuda, T., Nishinari, K. & Schadschneider, A. Critical bottleneck size for jamless particle flows in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 138701 (2014).

Janda, A., Zuriguel, I., Garcimartin, A., Pugnaloni, L. A. & Maza, D. Jamming and critical outlet size in the discharge of a two-dimensional silo. Europhys. Lett. 84, 44002 (2008).

Saraf, S. & Franklin, S. V. Power-law flow statistics in anisometric (wedge) hoppers. Phys. Rev. E 83, 030301 (2011).

Thomas, C. C. & Durian, D. J. Geometry dependence of the clogging transition in tilted hoppers. Phys. Rev. E 87, 052201 (2013).

Ashour, A., Wegner, S., Trittel, T., Boerzsoenyi, T. & Stannarius, R. Outflow and clogging of shape-anisotropic grains in hoppers with small apertures. Soft Matter 13, 402–414 (2017).

Koivisto, J. et al. Friction controls even submerged granular flows. Soft Matter 13, 7657–7664 (2017).

Mankoc, C., Garcimartin, A., Zuriguel, I., Maza, D. & Pugnaloni, L. A. Role of vibrations in the jamming and unjamming of grains discharging from a silo. Phys. Rev. E 80, 011309 (2009).

Merrigan, C., Birwa, S. K., Tewari, S. & Chakraborty, B. Ergodicity breaking dynamics of arch collapse. Phys. Rev. E 97, 040901 (2018).

Endo, K., Reddy, K. A. & Katsuragi, H. Obstacle-shape effect in a two-dimensional granular silo flow field. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 094302 (2017).

Zuriguel, I. et al. Silo clogging reduction by the presence of an obstacle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 278001 (2011).

Lozano, C., Janda, A., Garcimartín, A., Maza, D. & Zuriguel, I. Flow and clogging in a silo with an obstacle above the orifice. Phys. Rev. E 86, 031306 (2012).

To, K., Lai, P.-Y. & Pak, H. K. Jamming of granular flow in a two-dimensional Hopper. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 71–74 (2001).

Pugnaloni, Luis, A. & Barker, G. C. Structure and distribution of arches in shaken hard sphere deposits. Phys. A 337, 428–442 (2004).

To, K. & Lai, P.-Y. Jamming pattern in a two-dimensional hopper. Phys. Rev. E 66, 011308 (2002).

To, K. Jamming patterns in a two-dimensional hopper. Pramana J. Phys. 64, 963 (2005).

Zuriguel, I., Pugnaloni, L. A., Garcimartín, A. & Maza, D. Jamming during the discharge of grains from a silo described as a percolating transition. Phys. Rev. E 68, 030301 (2003).

Zuriguel, I., Garcimartín, A., Maza, D., Pugnaloni, L. A. & Pastor, J. M. Jamming during the discharge of granular matter from a silo. Phys. Rev. E 71, 051303 (2005).

Thomas, C. C. & Durian, D. J. Fraction of clogging configurations sampled by granular hopper flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 178001 (2015).

Gella, D., Zuriguel, I. & Maza, D. Decoupling geometrical and kinematic contributions to the silo clogging process. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 138001 (2018).

Marin, A., Lhuissier, H., Rossi, M. & Kähler, C. J. Clogging in constricted suspension flows. Phys. Rev. E 97, 021102 (2018).

To, K. Jamming transition in two-dimensional hoppers and silos. Phys. Rev. E 71, 060301 (2005).

López-Rodríguez, D. et al. Effect of hopper angle on granular clogging. Phys. Rev. E 99, 032901 (2019).

Lozano, C., Lumay, G., Zuriguel, I., Hidalgo, R. C. & Garcimartin, A. Breaking arches with vibrations: the role of defects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 068001 (2012).

Garcimartín, A., Zuriguel, I., Pugnaloni, L. A. & Janda, A. The shape of jamming arches in two-dimensional deposits of granular materials. Phys. Rev. E 82, 31306–31306 (2010).

Doi, M. & Edwards, S. F. The Theory of Polymer Dynamics (Clarendon, Oxford, 1986).

Guerrero, B. V., Chakraborty, B., Zuriguel, I. & Garcimartín, A. Nonergodicity in silo unclogging: broken and unbroken arches. Phys. Rev. E 100, 032901 (2019).

Mills, P., Rognon, P. G. & Chevoir, F. Rheology and structure of granular materials near the jamming transition. Europhys. Lett. 81, 64005 (2008).

Koivisto, J. & Durian, D. J. Effect of interstitial fluid on the fraction of flow microstates that precede clogging in granular hoppers. Phys. Rev. E 95, 032904 (2017).

Bonamy, D., Daviaud, F., Laurent, L., Bonetti, M. & Jp, B. Multiscale clustering in granular surface flows. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 034301 (2002).

Cates, M. E., Wittmer, J. P., Bouchaud, J. P. & Claudin, P. Jamming, force chains and fragile matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 1841–1844 (1998).

Bi, D., Zhang, J., Chakraborty, B. & Behringer, R. P. Jamming by shear. Nat. (Lond.) 480, 355–358 (2011).

Liu, A. J. & Nagel, S. R. Jamming is not just cool any more. Nat. (Lond.) 396, 21–22 (1998).

Mehta, A., Barker, G. C. & Luck, J. M. Cooperativity in sandpiles: statistics of bridge geometries. J. Stat. Mech.-Theory E. 2004, P10014 (2004).

Yang, J. et al. Three-dimensional clogging structures of granular spheres near hopper orifice. Chin. Phys. B 31, 14501–014501 (2022).

Mehta, A., Barker, G. C. & Luck, J. M. Heterogeneities in granular materials. Phys. Today 62, 40 (2009).

Cao, Y. X. et al. Structural and topological nature of plasticity in sheared granular materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 2911 (2018).

Kou, B. Q. et al. Granular materials flow like complex fluids. Nature 551, 360–363 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11974240, No. 12274292), and the Science and Technology Innovation Foundation of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. 21X010200829).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. designed the research. S.Z., Z.Z., H.Y., Z.L., and Y.W. performed the experiment. S.Z., Z.Z., H.Y., and Y.W. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Zeng, Z., Yuan, H. et al. Precursory arch-like structures explain the clogging probability in a granular hopper flow. Commun Phys 7, 202 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01694-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01694-7

This article is cited by

-

Identifying bridges from asymmetric load-bearing structures in tapped granular packings

Communications Physics (2025)