Abstract

Achieving fast gates and long coherence times for superconducting qubits presents challenges, typically requiring either a stronger coupling of the drive line or an excessively strong microwave signal to the qubit. To address this, we introduce on-chip filters of the qubit drive exhibiting a stopband at the qubit frequency, thus enabling long coherence times and strong coupling at the subharmonic frequency, facilitating fast single-qubit gates, and reduced thermal load. The filters exhibit an extrinsic relaxation time of a few seconds while enabling sub-10-ns gates with subharmonic control. Here we show up to 200-fold improvement in the measured relaxation time at the stopband. Furthermore, we implement subharmonic driving of Rabi oscillations with a π pulse duration of 12 ns. Our demonstration of on-chip filters and efficient subharmonic driving in a two-dimensional quantum processor paves the way for a scalable qubit architecture with reduced thermal load and noise from the control line.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The physical realization of a universal useful quantum computer comes with very stringent technical requirements, including those summarized in the DiVincenzo criteria1. One such requirement is a high coherence-time-to-gate-time (CT2GT) ratio, ensuring that the physical system representing a quantum bit, qubit, stores the encoded information with high fidelity until the execution of the assigned task. This property is reflected in the measured energy relaxation time of the qubit, T1, which is the time scale for the qubit to exponentially lose an excitation and return to its ground state. Various qubit modalities such as trapped ions2,3,4,5, spin qubits6,7,8,9, photonic qubits10,11,12,13, and superconducting qubits14,15,16,17 are being explored for longer relaxation times to enhance the CT2GT ratio.

Superconducting qubits, in particular, have exhibited significant progress, with relaxation times extending from a few nanoseconds14,18,19,20,21,22 to nearly a few milliseconds23,24,25,26 over the past two decades. The quest for further improvement of the coherence time is still ongoing. Alternatively, gates can be sped up to further improve the CT2GT ratio27,28. However, this requires strong external coupling of the qubit to the drive line, which inadvertently decreases the coherence of the qubit, thereby posing a significant trade-off.

The coherence times of a qubit are influenced not only by the external coupling but also by intrinsic losses, which, in properly designed qubits, represent the primary loss mechanism, thus limiting the qubit performance. These losses arise from various sources, such as the presence of two-level-system defects near the qubit29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 associated with dielectric losses and quasiparticle tunneling37,38,39,40. Significant progress has been made in understanding41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49 and mitigating these internal losses through the implementation of high-coherence materials25,26,50,51,52,53, fabrication recipes23,24,54,55, and improved qubit geometry56,57 leading to a situation where the external coupling should be made very weak not to limit qubit coherence, thus calling for high drive power at the qubit.

While engineering's very weak coupling to the qubit can increase the CT2GT ratio, it will impose a significant heat load on the dilution refrigerators that house the qubit, and especially on the attenuators that provide an electromagnetic environment for the qubit. To minimize the corresponding thermal noise reaching the qubit, attenuators are placed at multiple stages of the dilution refrigerators58. Additionally, this will also limit the number of gate operations that can be carried out before the cooling capacity of the dilution refrigerator is exceeded.

Recent progress59,60 has shown promise in addressing the above-discussed challenge of simultaneously achieving fast control and long coherence time. However, the approach of ref. 59 raises concerns about quasiparticle generation due to the saturation of the Josephson junction employed in the qubit drive line at high power levels. Another important work60 utilizes a novel way to drive a three-dimensional (3D) transmon qubit by subharmonics of the qubit resonance. Namely, the non-linearity of the qubit up-converts the drive at one-third of the qubit frequency to the qubit frequency in the spirit of three-wave mixing60. Inconveniently for scaling, the previous work employs bulky low-pass filters in the control line to suppress the spontaneous qubit decay to the strongly coupled drive line. Furthermore, to enable subharmonic control, only 43 dB of attenuation is used in the control line, which leads to a significant thermal noise photon of around 0.145 at a qubit frequency of 5 GHz.

In this work, we introduce designs and provide implementations of on-chip filters for subharmonic driving in two-dimensional qubit schemes. The on-chip filters are devised to fully isolate the qubit from the drive line at its resonance frequency while establishing two orders of magnitude stronger coupling at the subharmonic frequency compared to standard drive lines. This result enables fast single-qubit gates via subharmonic drive while demonstrating the T1 limit owing to the external coupling of seconds, thereby substantially improving the corresponding CT2GT ratio. Encouragingly, the introduced on-chip filters facilitate the use of over 60 dB of attenuation in the control lines to ensure a thermal noise photon below 2.5 × 10−3. Furthermore, we show that the use of a bulky low-pass filter creates unwanted resonances in the qubit drive line, modulating the measured T1 in extreme ranges. Thus our demonstration of subharmonic driving of a qubit in two dimensions, integrated with an on-chip filter, seems a promising pathway for scalable superconducting quantum processing units.

Results

Design and implementation of on-chip filters

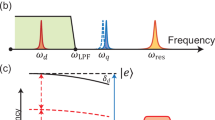

We have developed two distinct versions of on-chip filters: λ/4 and λ/2 filters as shown in Fig. 1a, b. Essentially, these filters are coplanar-waveguide (CPW) transmission lines that connect capacitively to the qubit at the position x = 0 and end in an open circuit at x = Lf, where Lf is the length of the filter. In the case of the λ/4 filter, Lf = λq/4, where λq is the wavelength of the mode in the drive line at the qubit frequency. Similarly, for the λ/2 filter, Lf = λq/2. We also note that λ/2 filter couples to the qubit at two separate positions as opposed to the single-point coupling in the case of the λ/4 filter. This two-point coupling design is inspired from multi-point coupling investigated in waveguide quantum electrodynamics61,62.

a, b Schematic representation of qubits (white crosses) strongly coupled to a transmission line (turquoise) implemented as (a) λ/4 and (b) λ/2 filters at the qubit frequency fq which corresponds to the full wavelength λq. c, d Voltage amplitude of the transmission line mode as a function of position x along the transmission line for the (c) λ/4 and (d) λ/2 filters. At the resonance frequency f = fq (red line), both on-chip filters effectively decouple from the qubit due to net zero voltage at the qubit, whereas at the subharmonic frequency f = fq/3 (blue line), the on-chip filters couple strongly to the qubit. The pink shading highlights the region where the modes couple to the qubit. e False-color optical-microscope image of the device. The device consists of three flux-tunable transmon qubits (violet) labeled Q1, Q2, and Q3. Each qubit is individually coupled to its own readout resonator (red) and flux lines (magenta). The readout resonators are further coupled to a common Purcell filter (yellow) for qubit readout. Additionally, qubits Q2 and Q3 are coupled to λ/4 and λ/2 filters respectively, whereas qubit Q1 is weakly coupled to a standard transmission line for control (turquoise).

The working principle of the on-chip filters is illustrated in Fig. 1c, d. In the λ/4 filter, the open-end creates a boundary condition for the voltage along the transmission line, resulting in a voltage anti-node at the open-end and a node at the qubit location when operating at the resonance frequency of the qubit as depicted in Fig. 1c. In contrast, the λ/2 filter exhibits a voltage anti-node at both the x = 0 and x = λ/2 locations, but with opposite polarities as shown in Fig. 1d. Both configurations enforce net-zero voltage amplitude for the qubit, effectively decoupling the qubit from the drive line at the qubit resonance frequency. However, at the subharmonic frequency, the voltage profile at the qubit is close to its maximum, thereby establishing a strong coupling between the qubit and the drive line. The length, over which the mode voltage is integrated to obtain the effective coupling strength between the mode and the qubit, is highlighted in Fig. 1a–d.

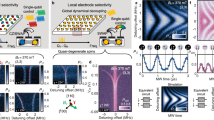

Our realized device is shown in Fig. 1e. The on-chip filters are integrated as a part of the qubit drive line. The device features three flux-tunable Xmon-style transmon qubits, labeled Q1, Q2, and Q363. Qubit Q1 is connected to a standard, weakly coupled CPW transmission line. In contrast, qubits Q2 and Q3 are connected to λ/4 and λ/2 filters, respectively. Additionally, the device includes flux lines to tune the frequencies of the qubits. Each qubit is coupled to its respective quarter-wavelength resonator for readout. These readout resonators are inductively and capacitively connected to a common quarter-wavelength Purcell filter64 to suppress qubit decay through the resonator.

We target the length of the on-chip filters such that their stopband is centered ~5 GHz. The results of our numerical simulations of these filters are shown in Fig. 2. For a detailed description of the electromagnetic (EM) simulations, we refer to the Supplementary Note S1 in Supplementary Information.

a Schematic of a 3-port network labeled P1, P2, and P3. Port P1 is connected to a qubit drive line through a filter which is a standard transmission line for Q1, λ/4 filter for Q2, and λ/2 filter for Q3. b Equivalent lumped-element model, where Cd is the capacitance between the qubit and the drive line, Cg is the capacitance between the qubit and the readout resonator, and Cq is the shunt capacitance of the qubit to the ground. The coupling capacitances Cd are 80 aF, 4.5 fF, and 9.2 fF for qubits Q1, Q2, and Q3, respectively. c Transmission amplitude from the qubit port to the drive line, S21, as a function of frequency for the different filter configurations as indicated. The λ/4 and λ/2 filters are designed to have a stopband at 5 GHz. The inset highlights the region in the vicinity of the filter stopband for convenient comparison. The shaded gray region corresponds to transmission at subharmonic frequency. d Estimated relaxation time, T1,ext, of the qubit owing to its coupling just to the drive line as a function of qubit frequency. This estimation is based on the total capacitance of the qubit and the input admittance Yin parallel to the qubit port P2. At the stopband, the estimated relaxation times of the qubit for the standard drive, the λ/4 filter, and for the λ/2 filter are approximately 0.3 ms, 7161 ms, and 2421 ms, respectively.

Figure 2a,b depict a schematic and its equivalent lumped-element model of a qubit coupled to an on-chip filter and to a readout resonator. In the model, 50-Ω lumped ports, labeled P1 for the drive line, P2 for the qubit, and P3 for the readout resonator, are introduced for EM simulations. We focus on the scattering parameter S21, which relates to the power transmission from the drive line to the qubit port, and on the input admittance Yin parallel to the qubit. Here, we are only interested in the coupling between the drive line and the qubit. Therefore, both S21 and Yin are calculated for the drive line port P1 matched to an impedance of 50 Ω and the resonator port P3 grounded. With this procedure, one can estimate the external coupling rate just from the drive line to be \({\gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}(\omega )={{{{{\rm{Re}}}}}}[{Y}_{{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}}(\omega )]/{C}_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}\)65,66. In the low-temperature limit, the relaxation time is given by \({T}_{{{{{{\rm{1}}}}}}}(\omega )={[1/{T}_{1,{{{{{\rm{ext}}}}}}}(\omega )+1/{T}_{1,{{{{{\rm{diel}}}}}}}(\omega )+1/{T}_{1,{{{{{\rm{oth}}}}}}}(\omega )]}^{-1}\), where T1,ext(ω) = 1/γq(ω) is the contribution from just the external coupling to the drive line, T1,diel(ω) corresponds to the dielectric losses of the qubit, and T1,oth(ω) accounts for other sources of relaxation such as readout resonators, flux lines, etc.

Figure 2c shows that within the filter stopband centered at 5 GHz, the transmission from the qubit port to the transmission line lies below −110 dB, greatly suppressed from −72 dB obtained for the standard drive line. Importantly, within the subharmonic frequency range of 1–2 GHz, we observe an increase of over 30 dB in the transmission of the on-chip filters over the standard case.

In Fig. 2d, we examine the relaxation time T1,ext of the qubit resulting from the external coupling to the drive line. Within the filter stopband, we observe an enhancement in T1,ext by a factor of over 1000 with the λ/4 and λ/2 filters compared with the standard drive line. The estimated T1,ext times at 5 GHz are as follows: 0.3 ms for the standard drive, 7161 ms for λ/4 filter, and 2421 ms for λ/2 filter. The widths of the frequency range where qubit T1,ext exceeds 1 ms are 70 MHz and 450 MHz for λ/4 and λ/2 filter, respectively. We attribute this difference of feasible frequency ranges to the fact that the λ/2 filter is of higher order than the λ/4 filter since the coupling points of the qubit are located at the voltage anti-nodes where the gradient of the voltage with respect to position vanishes.

Assuming a coupling that results in T1,ext = 1 ms for a qubit driven resonantly through a standard transmission line, we estimate that a microwave pulse with a peak power of −11 dBm at room temperature is necessary to implement 10-ns single-qubit gates. With the above-simulated parameters of the on-chip filters, corresponding peak powers of −16 dBm and −22 dBm will be required for λ/4 filter and λ/2 filter, respectively, using a subharmonic drive approach. Thus the filters combined with subharmonic driving may yield a significant reduction in power consumption for single-qubit gates. These values are calculated considering 60 dB of attenuation in the drive line and a simple rectangular pulse shape. Note that the peak powers may significantly increase for complex pulse shapes, which are currently being used to minimize the leakage out of the computational subspace for high-fidelity gates27.

Furthermore, with the above estimates, we obtain a heat dissipation of −53 dBm at the base plate resulting from a resonant drive with the standard transmission line. In the case of a subharmonic drive with the on-chip filters, we estimate heat dissipations of −58 dBm with λ/4 filter and −64 dBm with λ/2 filters.

Characterization of on-chip filters

We follow the typical steps to fabricate the device on a silicon wafer, which includes a niobium metallization layer on top. The micron-sized features in the niobium are created using maskless lithography and etching, while the Manhattan-style Josephson junctions are patterned using electron-beam lithography and thermal evaporation of aluminum. We cool down the device in a commercial Bluefors XLD500 dilution refrigerator for cryogenic measurements. For more detailed information on the fabrication process and the experimental setup, see the Supplementary Note S2 and S3 in Supplementary Information.

We carry out typical time-domain measurements to characterize the device parameters summarized in Table S1 in Supplementary Information. To quantify the performance of the on-chip filters, we measured the Rabi frequency and the T1 of the qubit around the target filter frequency of 5 GHz. A comprehensive description of the measurement sequence can be found in greater detail in the Supplementary Note S4 in Supplementary Information.

Figure 3a, b show the measured Rabi frequency for qubits driven through the λ/4 and λ/2 filters. We observe an impressive 50-fold and 220-fold suppression in measured Rabi frequency at the stopbands of λ/4 and λ/2 filters, respectively, corresponding to 34 dB and 47 dB changes in S21. The suppression factor is defined with respect to the maximum Rabi frequency observed in the qubit frequency range of 4–6.5 GHz. The simulated data depicted in Fig. 3a, b correspond to the Rabi frequency derived from the input admittance Yin obtained through EM simulations, see Methods. Evidently, the measured and simulated Rabi frequencies exhibit a high level of agreement. Some minor deviations observed can be attributed to parasitic resonance and imperfections stemming from coupling with the control lines.

a, b Measured (dots) and simulated (dashed line) Rabi frequencies of the qubit for (a) λ/4 and (b) λ/2 filters as functions of the qubit frequency fq = ωq/(2π). We swept qubit frequency in the range of 4 to 6.5 GHz and carried out the Rabi measurement to characterize the coupling strength of the drive lines to the qubit. The dashed line represents the Rabi frequency estimated using \({f}_{{{{{{\rm{R}}}}}}}={\Omega }_{{{{{{\rm{R}}}}}}}/2\pi =2\sqrt{{\gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}}\beta \), where \({\gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}={{{{{\rm{Re}}}}}}[{Y}_{{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}}]/{C}_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}\) and \(\beta \propto {\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}^{-1/2}V\), where V is the peak-to-peak voltage amplitude at the chip level. Note that the measured Rabi frequency for the λ/2 filter shows two distinct stopbands centered around 4.7 GHz and 5.7 GHz, the presence of which is attributed to the unequal coupling at positions x = 0 and x = λ/2. c, d Measured (dots) and simulated (dashed line) relaxation time, T1, of the qubit for (c) λ/4 and (d) λ/2 filters as functions of the qubit frequency. The dielectric loss tangent of 3 × 10−6 obtained from the fit is used to account for dielectric losses limiting the T1, represented by the red dashed line. While orange dashed line corresponds to the case without the dielectric losses. The simulated T1 also takes Purcell decay through the resonator into account. The error bars represent 1σ fitting uncertainty.

Note the significant discrepancy in the measured Rabi frequency for the λ/2 filter shown in Fig. 3b in comparison to the simulated transmission depicted in Fig. 2c. In contrast to a single stopband at 5 GHz, we observe two stopbands centered around 4.7 GHz and 5.7 GHz. As detailed in Supplementary Note S1 in Supplementary Information, this splitting of the stopband mainly arises from the asymmetry in the coupling capacitance between the drive line and the qubit at the positions x = 0 and x = λ/2, in addition to the fact that the coupling region at x = λ/2 is of finite length. Consequently, we show a good agreement between the measured and simulated results in Fig. 3b by introducing an asymmetric coupling at the open end of the λ/2 filter in the EM simulation.

Figure 3c, d depict the measured T1 for the λ/4 and λ/2 filter. In our device, we consistently observe a T1 ceiling of approximately 10 μs across all qubits. To investigate the reason for this limited T1, we fit the Purcell decay and dielectric-loss models to the measured T1 of qubit Q1 near its readout resonator frequency, see Supplementary Note S5 in Supplementary Information. From the fit, we obtain a dielectric loss tangent of 3 × 10−6, confirming dielectric loss as the primary loss mechanism in our device. Consequently, we used the dielectric loss tangent of 3 × 10−6 in the EM simulations, yielding the simulation results for qubits Q2 and Q3 in good agreement with the experiments. Without considering dielectric losses in the simulation, the extrapolated T1 at the filter frequency reaches hundreds of milliseconds range. Due to the Purcell decay through the resonator, the simulated T1 at the second stopband centered ~5.7 GHz shows only a few milliseconds.

For the qubit T1 measured at the stopband of the filter, we observed a remarkable 20-fold improvement for the λ/4 filter and an even more substantial 200-fold improvement for the λ/2 filter in comparison to the values measured at the flux sweet-spot of the qubit, see Supplementary Table S1 in Supplementary Information. This enhancement has the potential for further improvements through the use of low-loss dielectric materials and implementation of state-of-the-art fabrication processes for high coherence.

Resonant and subharmonic drive

Figure 4a, b present the flux spectroscopy results for qubit Q3 coupled to λ/2 filter using both resonant and subharmonic driving techniques. By sweeping the flux bias Φ threading through the SQUID in the units of flux quanta Φ0, we tune the frequency of qubit Q3 in a range of 500 MHz near the second stopband of the λ/2 filter centered around 5.7 GHz. With resonant driving, we observe a major reduction in the qubit linewidth as it approaches the stopband at 5.7 GHz. Note that also the two-photon process to excite the qubit from its ground state to the second excited state is visible at different flux bias but frequency matching to 5.7 GHz, consistent with the filter protecting the qubit at its stopband rather than the qubit itself being substantially different at a certain flux bias. However, with subharmonic driving, we observe a broadened qubit linewidth at around f = 5.7/3 = 1.9 GHz. This observation indicates that the λ/2 filter exhibits strong coupling at the subharmonic frequency but very weak coupling at the resonance frequency, which agrees with our intended design and purpose.

a, b Normalized readout signal of the qubit as a function of the flux bias and the frequency of the (a) resonant drive and (b) subharmonic drive. The top diagonal feature indicates the lowest transition frequency of the qubit and the bottom feature reveals the two-photon transition to the second excited state of the qubit. c,d Normalized readout signal of the qubit as a function of the driving-voltage amplitude at room temperature and the frequency of the (c) resonant drive and (d) subharmonic drive for a flux bias of 0.32 Φ0. Note the power broadening and up to − 70 MHz alternating-current (AC) Stark shift in (d) with increasing pulse amplitude. e, f Normalized readout signal of the qubit as a function of the pulse length and the frequency of the (e) resonant drive and (f) subharmonic drive for a flux bias of 0.32 Φ0. In e, the pulse amplitude 1 V yields a Rabi frequency of 17.57 MHz and in f, we have 0.9 V and 31.12 MHz, respectively, at the Stark-shifted frequency of 1.809 GHz.

Qubit power spectroscopy with resonant driving in Fig. 4c demonstrates a broadening of the qubit line with increasing pulse amplitude. The spectroscopic line remains centered at the frequency of 5.6 GHz independent of the pulse amplitude. In contrast, Fig. 4d exhibits a pronounced AC Stark shift caused by the off-resonant nature of the subharmonic drive. The AC Stark shift of the qubit frequency is typical for an off-resonant driving of the qubit49. This shift increases with increasing pulse amplitude, reaching ~−70 MHz at the maximum amplitude used. The negative direction of the shift arises from the negative anharmonicity of the transmon qubit. Figure 4e, f illustrate Rabi oscillations of the qubit under resonant and subharmonic driving. For room-temperature pulse amplitudes of 1 V and 0.9 V, the measured Rabi frequencies for resonant and subharmonic driving are 17.57 MHz and 31.12 MHz, respectively. In the case of subharmonic drive, the Rabi frequency corresponding to the slowest oscillation occurs with an AC Stark shift of −57.67 MHz.

Rabi frequency and AC Stark shift

Figure 5a shows the AC Stark shift arising from the off-resonant nature of the subharmonic drive. For a maximum pulse amplitude of 1 V, the measured shift is ~−33 MHz for the λ/4 filter and −73 MHz for the λ/2 filter. We obtain a good agreement between the measured Stark shift and the fit using a quadratic function in the pulse amplitude as theoretically expected from Eq. (5) in the “Method” section.

In Fig. 5b, we conduct a performance comparison between the λ/4 and λ/2 filters using the subharmonic drive. This comparison involves varying the pulse amplitude to measure the Rabi frequency at the AC-Stark-shifted frequency studied in Fig. 5a. We observe that the maximum measured Rabi frequency is approximately 13 MHz and 43 MHz, resulting in π pulses of lengths 37 ns and 12 ns with the λ/4 and λ/2 filters, respectively. We employ a cubic function to fit the measured Rabi frequencies as a function of the pulse amplitude, showing an excellent agreement with the experimental results as expected from the three-wave-mixing nature of subharmonic driving, as can be seen from Eq. (5) in the Method section. Importantly, we maintain over 70 dB of attenuation in the drive line to ensure that the thermal occupation of the qubit remains below 0.5%, and limit heat dissipation at the base plate to less than −40 dBm = 100 nW.

Discussion

In this work, we addressed the seemingly competing challenges of implementing fast single-qubit gates and mitigating the decoherence of qubits due to the strong coupling needed for such fast gates. These challenges are intimately related to the power dissipation budget in the dilution refrigerator that houses the qubits and cross-talk mitigation between the qubits.

A transmon qubit with a standard capacitive coupling to its broadband drive line resulting in T1,ext of 1 ms requires a peak power of −11 dBm at room temperature to implement 10-ns-long single-qubit gates using a resonant drive. This power requirement is estimated considering 60 dB attenuation in the drive line to keep thermal qubit excitations low. In contrast, a subharmonic drive requires roughly 25 dBm in this scenario with no drive line filter. Such drive power leads to heat dissipation of ~−17.5 dBm at the base plate, unfortunately matching its cooling capacity of −17 dBm.

Our proposed on-chip filters are designed to achieve a T1,ext bound of 7161 ms for the λ/4 filter and 2421 ms for the λ/2 filter at the stopband near the qubit transition frequency. We estimate peak powers of −16 dBm for the λ/4 filter and −22 dBm for the λ/2 filter at room temperature to implement 10-ns-long gates using subharmonic driving. With 60 dB of attenuation in the drive lines, the heat dissipation at the base plate is reduced to −58 dBm for the λ/4 filter and to −64 dBm for the λ/2 filter, enabling tens of thousands of simultaneous gate operations before reaching the cooling power of typical refrigerators.

Experimentally, we achieved an impressive 50-fold and 220-fold suppression in the measured Rabi frequency and a factor of 50 and 80 improvements in the measured T1 at the stopbands of the λ/4 and λ/2 filters, respectively. We measured a maximum T1 of 10 μs across the device, mainly limited by dielectric losses. The simulated and measured data exhibited excellent agreement, from which we conclude that the on-chip filters function as desired. We note that using state-of-the-art fabrication processes for high coherence and low-loss dielectric materials may further enhance these results and allow for more thorough study of the effects of the filters on the qubit energy relaxation time.

In our subharmonic-drive experiments, we obtained qubit spectroscopy akin to those with resonant driving using standard two-tone measurements. We measured π pulse lengths of 37 ns and 12 ns for the λ/4 and λ/2 filters, respectively, using Rabi measurements. This result was obtained with 62 dB of attenuation distributed across various dilution stages, combined with an additional 12 dB of attenuation from filters and wires at room temperature and inside the refrigerator, yielding ~74 dB in total in the drive line. This configuration effectively reduced thermal noise photons to below 2.5 × 10−3 at qubit frequency and around 0.03 at subharmonic frequency. This is a prominent improvement compared to the work in ref. 60, where single-qubit gate of length 35 ns has been demonstrated with only 43 dB attenuation in the qubit control line and with the use of bulky off-chip low-pass filters.

The off-resonant nature of the subharmonic drive led to a substantial AC Stark shift of ~−73 MHz at a Rabi frequency of about 43 MHz with the λ/2 filter, significantly more pronounced than in resonant driving. As a result, the standard approach for implementing and characterizing single-qubit gates through Randomized Benchmarking may not be feasible as such, calling for special attention to phase correction between gates. In addition, minimization of leakage errors with such brief gates is also pivotal. Although the drag scheme effectively reduces leakage errors in resonant driving, a similar approach adapted for subharmonic driving needs to consider the large AC Stark shift. Addressing this issue stands as an interesting topic for future research.

Methods

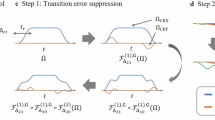

Single-qubit control

The Hamiltonian describing the control of the qubit has the following form

where the first term on the right is the Hamiltonian of the undriven qubits and the the second term is the drive Hamiltonian. The Hamiltonian of the transmon qubit is given by

where ωq is the angular frequency of the lowest qubit transition, α is the anharmonicity, and \(\hat{b}\) and \({\hat{b}}^{{{\dagger}} }\) are the annihilation and creation operators acting on the qubit states, respectively. The driving Hamiltonian assumes the form

where ΩR is the Rabi angular frequency, and ωd and φd are the frequency and the phase of the microwave drive. To implement arbitrary single-qubit gates, the Rabi frequency and the phase of the drive are temporally controlled.

In the case of resonant driving, we have ωd ≈ ωq. By going into a frame rotating at ωd, we obtain a simplified qubit-drive Hamiltonian with the detuning \({\delta }_{{{{{{\rm{res}}}}}}}={\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}-{\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}\),

For the subharmonic driving, instead we have ωd = ωq/3 + δsub and following the derivation in60, we find

where \(\eta =\frac{{\Omega }_{{{{{{\rm{R}}}}}}}({\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}-\alpha )}{{\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}^{2}-{({\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}-\alpha )}^{2}}\) represents the strength of the subharmonic drive. From the Hamiltonian, we obtain the AC Stark shift δsub = 2α∣η∣2/3 resulting from the off-resonant drive and the subharmonic Rabi frequency \({\Omega }_{{{{{{\rm{R}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}}}=2\alpha | \eta {| }^{3}/3\).

Relation of the external coupling strength and Rabi frequency with admittance

In our experiments, we capacitively couple a CPW transmission line to the qubit for control. The interaction strength between the drive line and the qubit is given by ref. 67

where e is the elementary charge, Cd is the capacitance between the qubit and the drive line, EJ is the Josephson energy, EC is the charging energy of the qubit, Ztml is the characteristic impedance of the drive line, and Cq is the capacitance of the qubit island, respectively.

We express the Rabi frequency in terms of the interaction strength as

where \(\beta ={(\frac{1}{2\hslash {\omega }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}{Z}_{{{{{{\rm{tml}}}}}}}})}^{\frac{1}{2}}V\) and V is the voltage amplitude of the drive67. From Eqs. (6) and (7), we observe that for the resonant case, the Rabi frequency ΩR ∝ V, whereas for subharmonic drive, \({\Omega }_{{{{{{\rm{R}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}}}\propto {V}^{3}\). This cubic scaling with respect to the voltage amplitude renders the subharmonic drive favorable over resonant driving at high amplitudes or coupling strengths.

The above simplified analytical equation may be used to obtain γq of the qubit at weak coupling to the transmission line. In our case, we also consider the complete system of a qubit strongly coupled to an on-chip filter and to the readout resonator. Here, we resort to electromagnetic simulations to estimate the external coupling strength using \({\gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}(\omega )={{{{{\rm{Re}}}}}}[{Y}_{{{{{{\rm{in}}}}}}}(\omega )]/{C}_{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}\), where Yin is the admittance in parallel with the qubit obtained from the simulations65,66.

Electromagnetic simulations

The device layout is created using KQCircuits, an open-source Python library, within the KLayout editor. Subsequently, this layout is exported to the electromagnetic-simulation environment of the Sonnet software. Owing to the relatively large size of the qubit-drive geometry and the associated complexity of the simulation, we simplify the model by replacing a part of the transmission line by a lumped port, which allows for building a simulation of the full device using a lumped-circuit simulator.

The scattering-parameter data is exported from Sonnet to Microwave Office AWR, where we construct and simulate a full-circuit model. We extract and export the input admittance Yin for further analysis in Python. A comprehensive description of the steps taken to achieve these simulation results is presented in the Supplementary Note S1 in Supplementary Information.

Data availability

All relevant data and codes generating the figures in this article are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1123484268.

References

DiVincenzo, D. P. The physical implementation of quantum computation. Fortschr. der Phys. 48, 771–783 (2000).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum computations with cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4091–4094 (1995).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579–584 (2017).

Bluvstein, D. et al. A quantum processor based on coherent transport of entangled atom arrays. Nature 604, 451–456 (2022).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A- Mol. Opt. Phys. 57, 120–126 (1998).

Xue, X. et al. Quantum logic with spin qubits crossing the surface code threshold. Nature 601, 343–347 (2022).

Weinstein, A. J. et al. Universal logic with encoded spin qubits in silicon. Nature 615, 817–822 (2023).

Burkard, G., Ladd, T. D., Pan, A., Nichol, J. M. & Petta, J. R. Semiconductor spin qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 025003 (2023).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & Milburn, G. J. A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics. Nature 409, 46–52 (2001).

Browne, D. E. & Rudolph, T. Resource-efficient linear optical quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 010501 (2005).

O’Brien, J. L. Optical quantum computing. Science 318, 1567–1570 (2007).

Shi, S. et al. High-fidelity photonic quantum logic gate based on near-optimal Rydberg single-photon source. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–6 (2022).

Nakamura, Y., Pashkin, Y. A. & Tsai, J. S. Coherent control of macroscopic quantum states in a single-Cooper-pair box. Nature 398, 786–788 (1999).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A- Mol. Opt. Phys. 76, 042319 (2007).

Devoret, M. H. & Martinis, J. M. Implementing qubits with superconducting integrated circuits. Exp. Asp. Quant. Comput. 3, 163–203 (2005).

Kockum, A. F. & Nori, F. Quantum bits with josephson junctions. Springe Ser. Mater. Sci. 286, 703–741 (2019).

Mooij, J. E. et al. Josephson persistent-current qubit. Science 285, 1036–1039 (1999).

Friedman, J. R., Patel, V., Chen, W., Tolpygo, S. K. & Lukens, J. E. Quantum superposition of distinct macroscopic states. Nature 406, 43–46 (2000).

Vion, D. et al. Manipulating the quantum state of an electrical circuit. Science 296, 886–889 (2002).

Han, S., Yu, Y., Chu, X., Chu, S. I. & Wang, Z. Time-resolved measurement of dissipation-induced decoherence in a Josephson junction. Science 293, 1457–1459 (2001).

Simmonds, R. W. et al. Decoherence in josephson phase qubits from junction resonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 077003 (2004).

Wang, C. et al. Towards practical quantum computers: transmon qubit with a lifetime approaching 0.5 milliseconds. npj Quant. Inf. 8, 1–6 (2022).

Verjauw, J. et al. Path toward manufacturable superconducting qubits with relaxation times exceeding 0.1 ms. npj Quant. Inf. 8, 1–7 (2022).

Place, A. P. et al. New material platform for superconducting transmon qubits with coherence times exceeding 0.3 milliseconds. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–6 (2021).

Somoroff, A. et al. Millisecond coherence in a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 267001 (2023).

Werninghaus, M. et al. Leakage reduction in fast superconducting qubit gates via optimal control. npj Quant. Inf. 7, 1–6 (2021).

Ding, L. et al. High-fidelity, frequency-flexible two-qubit fluxonium gates with a transmon coupler. Phys. Rev. X 13, 031035 (2023).

Martinis, J. M. et al. Decoherence in Josephson qubits from dielectric Loss. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 210503 (2005).

Gao, J. et al. A semiempirical model for two-level system noise in superconducting microresonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 212504 (2008).

Lindström, T., Healey, J. E., Colclough, M. S., Muirhead, C. M. & Tzalenchuk, A. Y. Properties of superconducting planar resonators at millikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 80, 132501 (2009).

Macha, P. et al. Losses in coplanar waveguide resonators at millikelvin temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 62503 (2010).

Pappas, D. P., Vissers, M. R., Wisbey, D. S., Kline, J. S. & Gao, J. Two level system loss in superconducting microwave resonators. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 21, 871–874 (2011).

Neill, C. et al. Fluctuations from edge defects in superconducting resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 72601 (2013).

Müller, C., Lisenfeld, J., Shnirman, A. & Poletto, S. Interacting two-level defects as sources of fluctuating high-frequency noise in superconducting circuits. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 92, 035442 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Surface participation and dielectric loss in superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 162601 (2015).

Lutchyn, R. M., Glazman, L. I. & Larkin, A. I. Kinetics of the superconducting charge qubit in the presence of a quasiparticle. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 74, 064515 (2006).

Paik, H. et al. Observation of high coherence in Josephson junction qubits measured in a three-dimensional circuit QED architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 240501 (2011).

Catelani, G. et al. Quasiparticle relaxation of superconducting qubits in the presence of flux. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 077002 (2011).

Catelani, G., Nigg, S. E., Girvin, S. M., Schoelkopf, R. J. & Glazman, L. I. Decoherence of superconducting qubits caused by quasiparticle tunneling. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 86, 184514 (2012).

Paladino, E., Galperin, Y., Falci, G. & Altshuler, B. L. 1/ f noise: Implications for solid-state quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 361–418 (2014).

Burnett, J. et al. Evidence for interacting two-level systems from the 1/f noise of a superconducting resonator. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–6 (2014).

Pop, I. M. et al. Coherent suppression of electromagnetic dissipation due to superconducting quasiparticles. Nature 508, 369–372 (2014).

Lisenfeld, J. et al. Electric field spectroscopy of material defects in transmon qubits. npj Quant. Inf. 5, 1–6 (2019).

Yan, F. et al. The flux qubit revisited to enhance coherence and reproducibility. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–9 (2016).

Vepsäläinen, A. P. et al. Impact of ionizing radiation on superconducting qubit coherence. Nature 584, 551–556 (2020).

Murray, C. E. Material matters in superconducting qubits. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 146, 100646 (2021).

Siddiqi, I. Engineering high-coherence superconducting qubits. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 875–891 (2021).

Carroll, M., Rosenblatt, S., Jurcevic, P., Lauer, I. & Kandala, A. Dynamics of superconducting qubit relaxation times. npj Quant. Inf. 8, 1–7 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Improving the coherence time of superconducting coplanar resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 233508 (2009).

Megrant, A. et al. Planar superconducting resonators with internal quality factors above one million. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 113510 (2012).

Chang, J. B. et al. Improved superconducting qubit coherence using titanium nitride. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 12602 (2013).

Stern, M. et al. Flux qubits with long coherence times for hybrid quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 123601 (2014).

Bruno, A. et al. Reducing intrinsic loss in superconducting resonators by surface treatment and deep etching of silicon substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 182601 (2015).

Deng, H. et al. Titanium nitride film on sapphire substrate with low dielectric loss for superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 024013 (2023).

He, H., Wang, W., Liu, F., Yuan, B. & Shan, Z. Suppressing the dielectric loss in superconducting qubits through useful geometry design. Entropy 24, 952 (2022).

Martinis, J. M. Surface loss calculations and design of a superconducting transmon qubit with tapered wiring. npj Quant. Inf. 8, 1–12 (2022).

Krinner, S. et al. Engineering cryogenic setups for 100-qubit scale superconducting circuit systems. EPJ Quant. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-019-0072-0 (2019).

Kono, S. et al. Breaking the trade-off between fast control and long lifetime of a superconducting qubit. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–6 (2020).

Xia, M. et al. Fast superconducting qubit control with sub-harmonic drives http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.10162 (2023).

Frisk Kockum, A., Delsing, P. & Johansson, G. Designing frequency-dependent relaxation rates and Lamb shifts for a giant artificial atom. Phys. Rev. A- Mol. Opt. Phys. 90, 013837 (2014).

Kannan, B. et al. Waveguide quantum electrodynamics with superconducting artificial giant atoms. Nature 583, 775–779 (2020).

Barends, R. et al. Coherent josephson qubit suitable for scalable quantum integrated circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 080502 (2013).

Jeffrey, E. et al. Fast accurate state measurement with superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 190504 (2014).

Esteve, D., Devoret, M. H. & Martinis, J. M. Effect of an arbitrary dissipative circuit on the quantum energy levels and tunneling of a Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 34, 158–163 (1986).

Houck, A. A. et al. Controlling the spontaneous emission of a superconducting transmon qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 080502 (2008).

Blais, A., Grimsmo, A. L., Girvin, S. M. & Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025005 (2021).

Sah, A., Kundu, S., Suominen, H., Chen, Q. & Möttönen, M. Data and codes for “Decay-protected superconducting qubit with fast control enabled by integrated on-chip filters https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11234843 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the KAUTE Foundation for their support through the Ph.D. grant awarded to the first author. We acknowledge the European Research Council under the Advanced Grant no. 101053801 (ConceptQ), Business Finland under the Quantum Technologies Industrial project (Grant no. 2118781) and Academy of Finland under its Centre of Excellence Quantum Technology Finland (Grant no. 352925) and through the Finnish Quantum Flagship. Special thanks are extended to Sergei Lemziakov, Dmitrii Lvov, and Joonas Peltonen for their invaluable assistance with the Otanano cryogenic facility. The authors acknowledge Giacomo Catto, Timm Mörstedt, and Priyank Singh for useful discussions related to the fabrication and Jukka-Pekka Kaikkonen from VTT Technical Research for providing us with the unpatterned Niobium-on-Silicon wafer. Furthermore, we are thankful for the enriching general discussions on the subject matter with Michael Hatridge, Florian Blanchet, Arman Alizadeh, Wallace Santos Teixeira, Vasilii Vadimov, and Johannes Heinsoo. We thank Eric Hyyppä for encouraging discussions and insightful comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. and M.M. conceived the experiment. A.S. and S.K. designed and carried out the electromagnetic simulations of the device. H.S. and A.S. wrote the measurement codes for the experiment. Q.C. helped with the theoretical discussions on subharmonic drive. A.S. fabricated the device, conducted the experiments, and analyzed the results with feedback from S.K. A.S., S.K., and M.M. wrote the manuscript with comments from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.M. declares that he is a Co-Founder and Shareholder of IQM Finland Oy. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Martina Esposito and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sah, A., Kundu, S., Suominen, H. et al. Decay-protected superconducting qubit with fast control enabled by integrated on-chip filters. Commun Phys 7, 227 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01733-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01733-3

This article is cited by

-

Fast superconducting qubit control with subharmonic drives

Nature Communications (2025)