Abstract

The development in attosecond physics allows for unprecedented control of atoms and molecules in the time domain. Here, ultrashort pulses are used to prepare atomic ions in specific magnetic states, which may be important for controlling charge migration in molecules. Our work fills the knowledge gap of relativistic hole alignment prepared by femtosecond and attosecond pulses. The research focuses on optimizing the central frequency and duration of pulses to exploit specific spectral features, such as Fano profiles, Cooper minima, and giant resonances. Simulations are performed using the Relativistic Time-Dependent Configuration-Interaction Singles method. Ultrafast hole alignment with large ratios (on the order of one hundred) is observed in the outer-shell hole of argon. An even larger alignment (on the order of one thousand) is observed in the inner-shell hole of xenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For decades, optical pumping has been used to prepare quantum systems, such as atoms and molecules, in specific magnetic quantum states1. Given the many advances of attosecond science over the last two decades2,3,4,5, we now ask if it is possible to prepare ions in well-defined magnetic states on ultrafast timescales. In the present work, we theoretically investigate state preparation in noble gas atoms by photoionization using ultrashort pulses on the femtosecond and attosecond timescales. The resulting ions then consist of different holes characterized by the properties of the missing photoelectrons. Here, we are interested in the population ratios between holes with different magnetic quantum numbers, mj, but the same total angular momentum, j, a property generally referred to as hole alignment. Heinrich-Josties et al.6 have studied hole alignment in neon using the 2s−13p Fano resonance. More recently, Gryzlova et al.7 looked at the time-dependent and stationary hole alignment in krypton and investigated how the polarization of the ionic state influences the process of sequential ionization induced by intense laser fields.

Since holes in noble gas atoms, particularly the heavy ones, are coupled to the total angular momentum: j = ℓ + s, it is crucial to account for spin-orbit coupling, which is a relativistic (fine-structure) effect. While semi-relativistic corrections can be made to the Schrödinger equation, such as the Breit-Pauli Hamiltonian employed in R-Matrix with Time-dependence8, or relativistic effective core potentials applied to Time-Dependent Configuration-Interaction Singles (TDCIS)9, the Dirac equation stands out as the more fundamental framework for studies of relativistic atomic and molecular effects10. Approximate methods have been developed to find a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency depending on the application. While atomic structure calculations typically involve relativistic multi-configuration approaches with large numbers of optimized and adapted states11, many-body screening effects in dynamical processes can be treated by the self-consistent Hartree-Fock theory that is based on a single Slater determinant for noble gas atoms12. As an example, the time-dependent linearized relativistic Hartree-Fock theory, referred to as the Relativistic Random Phase Approximation13, has recently been used to compute attosecond time delays from heavy atoms14. Strong-field processes require theories beyond the linear response, which serves as a motivation for the development of novel theoretical relativistic many-body methods. The Relativistic Time-Dependent Configuration-Interaction Singles (RTDCIS) method15 is a methodology that was directly adapted from the non-relativistic TDCIS, a many-body theory developed to study electron correlation effects of atoms in strong laser fields16.

Analogous to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, there is a trade-off between the temporal and spectral domains. Therefore, a review of cross sections of the atomic systems is critical for hole alignment, as they impose fundamental limitations on the degree of hole alignment that is possible to achieve. Photoionization cross sections of many-electron atoms provide valuable information about correlated processes17,18,19. Fano resonances emerge as distinctive asymmetric profiles, arising from interference between indistinguishable pathways: direct ionization and autoionization, which both lead to the same final state of the photoelectron and the ion20. Cooper minima appear when photoelectrons exhibit a strongly reduced rate due to a vanishing dipole matrix element from the initial orbital to the continuum state21. Moreover, heavy atoms, like xenon, exhibit a giant resonance as a result of the interaction of 4d electrons when trapped behind the centrifugal potential barrier22,23,24. Beyond their fundamental significance, these atomic processes have found a new era of applications in high-order harmonic generation25,26, attosecond time delay studies27,28,29, and attosecond transient absorption30. While the timescales of Fano resonances typically span femtoseconds or longer, the broad bandwidth of several electronvolts associated with Cooper minima and giant resonances implies electron dynamics on attosecond timescale31,32. Besides, giant resonances have found applications as a mechanism for two-photon XUV processes33 and their phase has been studied34. The developments in attosecond physics allow us to study the temporal dynamics of the corresponding ions in transient absorption experiments35. Control of atomic ions36 is also critical for understanding charge migration in molecules37,38,39.

In this work, we use the RTDCIS method15, to investigate cross-sections and photoelectron fluxes from closed-shell atoms interacting with ultrashort pulses. Founded on Dirac-Fock spin-orbitals, RTDCIS accounts for electron correlation effects on the level of single excitations, enabling the simulation of photoelectron-hole pairs within a relativistic framework. We are particularly interested in the populations of the reduced ion channels that together account for all ionization from the atom. The computed reduced populations are then used to calculate the hole alignment. Time-dependent simulations are performed to optimize femtosecond and attosecond pulse excitation dynamics for achieving maximum alignment. Additionally, the laser field frequency is tuned to exploit specific spectral properties of the photoionization cross section of neon, argon, and xenon to control the hole alignment.

Methods

First, we provide a brief overview of the RTDCIS methodology, which is fundamental to our study, and then define the alignment of ion holes in relativistic (ℓs)j-coupling and explain how the RTDCIS is used to compute the required ionic populations using photoelectron probability fluxes. Atomic units (au) are the default unless specified otherwise e = ℏ = me = 4πϵ0 = 1.

RTDCIS methodology

The time-dependent Dirac equation (TDDE) for a many-electron atom in a laser field is given by

where \(\hat{H}\) is the Dirac Hamiltonian of the stationary atom, and \(\hat{V(t)}\) represents the time-dependent electron interaction with the laser field within the dipole approximation. In RTDCIS, the time-dependent many-electron wave function is expressed in terms of the RCIS (relativistic configuration-interaction singles) ansatz,

where \(\left\vert {\Phi }_{a}^{p}\right\rangle ={\hat{a}}_{p}^{{{{\dagger}}} }{\hat{a}}_{a}\left\vert {\Phi }_{0}^{{{{{\rm{DF}}}}}}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {\Phi }_{0}^{{{{{\rm{DF}}}}}}\right\rangle ={\hat{a}}_{N}^{{{{\dagger}}} }\ldots {\hat{a}}_{c}^{{{{\dagger}}} }{\hat{a}}_{b}^{{{{\dagger}}} }{\hat{a}}_{a}^{{{{\dagger}}} }\left\vert 0\right\rangle\), with \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) being the vacuum state15. Indices a, b, c, …are used for occupied orbitals, while p, q, r, s, …are used for virtual orbitals, and i, j, k,…are used to generally indicate any orbital. One-electron (4-component spinor) orbitals are obtained by solving the Dirac-Fock equation:

where \({\hat{h}}_{0}^{{{{{\rm{DF}}}}}}\) is the one-particle Dirac-Fock operator and εi are the corresponding orbital energies given by

where the two-electron integrals \(\langle ib| {r}_{12}^{-1}| ib\rangle\) and \(\langle ib| {r}_{12}^{-1}| bi\rangle\) are expressed in the physicists’ notation. The one-particle Dirac operator is

where c is the speed of light, p = − i ∇ the electron momentum operator, r the electron position, Z the nuclear charge, and Dirac matrices (α and β) are defined in terms of Pauli spin-matrices, σi, i = x, y, z and the identity 2 × 2 matrix as

For a spherical polar coordinate system, the Dirac-Fock orbitals are given by

with Pn,κ and Qn,κ being the radial parts, and χκ,m the spin angular part, and the angles θ, and ϕ collectively represented by Ω. Within the so-called ℓs-convention, the angular functions are expressed as follows,

where the good angular quantum number is denoted by κ and relates the spin and the orbital angular momentum with the total angular momentum j to describe an atomic state uniquely. Thus, we have the following relations:

At this point, the relativistic equations of motion can be derived. The many-body field-free Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) is given by

where the Dirac-Fock Hamiltonian written in the second quantization is

The perturbation term, H1, is the difference between the exact Coulomb interaction and the Dirac-Fock potentials:

As usual, the zero energy reference is chosen to be the Dirac-Fock ground state energy,

to achieve concise equations of motion. The interaction Hamiltonian in the length (Goeppert-Mayer) gauge takes the following form:

where E(t) is the electric field of the laser. Finally, by inserting the ansatz outlined in Eq. (2) into the Dirac equation in Eq. (1), and projecting onto either the ground state or the singly excited states, we derive the time evolution of the coefficients c0(t) and \({c}_{a}^{p}(t)\), respectively. Then, the RTDCIS equations of motion are given by

Note that our methodology differs from the non-relativistic calculations (TDCIS) in refs. 40 and 16 in the use of relativistic one-particle orbitals. As discussed in ref. 15, the level of electron-correlation included in RTDCIS is equivalent to the so-called Tamm-Dancoff approximation (forward diagrams only in linear response). The advantage of RTDCIS compared to the standard implementations of the Relativistic Random Phase Approximation is the possibility of exploring explicit time-dependent processes in weak and strong regimes. The drawback of RTDCIS is that it is not a self-consistent field theory as it builds on field-free orbitals rather than time-dependent orbitals that depend on the external field41. For more details about single-reference methods, see ref. 42.

Numerical implementation

The equations of motion are numerically integrated using a basis set of B-splines to represent the radial part of the Dirac-Fock orbitals. The numerical solution of the radial Dirac-Fock equation is not trivial due to the appearance of the so-called spurious states. To mitigate this issue, we employ a basis consisting of two B-spline sets with different orders for the large and the small components43. Additionally, to prevent nonphysical reflections during time propagation, core, and virtual orbitals are determined through a Dirac-Fock calculation in the presence of a complex absorbing potential44. Time propagation was carried out using a second-order finite-differencing scheme45. It should also be noted that in our study, we look at the final ionic state populations, which implies that our propagation times are chosen to be long enough to capture the decay of any autoionizing states. Here, the negative-energy states are omitted in Eqs. (15) and (16), which results in time-dependent dynamics purely in the positive-energy state space. This is a good approximation for the Dirac equation expressed on the length-gauge form15. Moreover, cross sections are computed using RTDCIS as described in our methodology paper15 following earlier work on TDCIS17.

Theory of hole alignment

According to quantum mechanics, the probability density and flux can, respectively, be constructed from the time-dependent wavefunction, Ψ(r, t), as follows46:

which are related to each other through the continuity equation,

Relativistic time-dependent photoelectron fluxes, denoted by \({{{{{\mathcal{J}}}}}}_{\kappa ,a}({{{{\bf{r}}}}},t)\), can be derived from Eq. (19) by using the relativistic time-dependent wavefunctions, resulting from solving the TDDE, as described in the previous section. We are interested in the (time-dependent) photoelectron fluxes going out from a sphere volume with radius R. So we integrate both terms in Eq. (19) with respect to this volume, to arrive at the expression:

where κ denotes the ionized electron from a hole a. According to Eq. (9), κ describes the orbital and total angular momenta, lp and jp, of the photoelectron, respectively. The time-integrated photoelectron fluxes give the photoelectron populations for a given electron-hole channel. To compute the population of a specific hole, the photoelectron populations associated with it are summed incoherently:

with \({m}_{j}^{p}={m}_{j}^{a}={m}_{j}\) due to linear polarization of the field. Laser-driven ionic couplings beyond R are not considered but are part of the equations of motion (Eq. (16))47. The quantity of interest in the hole alignment study is the ratio between the ion hole populations with the same \({j}_{a}=j_{a}^{\prime}\) quantum number, but different \({m}_{j} \, \ne \, m_{j}^{\prime}\) quantum numbers, and it is defined as:

In non-relativistic hole alignment, the focus lies on the ratio among holes characterized by distinct mℓ quantum numbers6. One should note, however, that such alignment is not stationary in the presence of relativistic (spin-orbit) effects in the ion. In contrast, the total magnetic quantum number, mj, is a conserved quantity, for both non-relativistic and relativistic cases, over the total lifetime of the ion. Furthermore, hole alignment should be distinguished from spin polarization, which concerns the proportion of ionized electrons with different ms quantum numbers instead. Unlike the ionic case, the stationary magnetic quantum numbers of the photoelectron are ms and mℓ for asymptotic scattering states, kσ, c.f. refs. 19,48.

Results

Results for hole alignment are presented for three atomic systems: neon, argon, and xenon. The corresponding total photoionization cross sections, computed by RTDCIS, are shown in Fig. 1a, b, and c, respectively. Fano resonances (F) in neon and Cooper minimum (C) in argon are both structures that serve as candidates for stationary hole alignment in outer atomic orbitals (the 2p and 3p, respectively). In xenon, the giant resonance (G) and the Cooper minimum (C) are candidates for non-stationary hole alignment in inner atomic orbitals, such as the 4d. In the following, we present results for these atoms in order. Excitation by pulses of different central frequencies and pulse durations, ranging from attoseconds to a few femtoseconds, is considered to investigate ultrafast hole alignment.

Neon

Figure 1 (a) shows the RTDCIS cross-section of neon with a Rydberg series of Fano profiles, corresponding to the autoionizing states in the 2s−1np configuration. Here, we will focus on the strongest Fano resonance (2s−3p) for hole alignment purposes (marked with F). In this case, the pathway 1s22s22p6 + γ → 1s22s22p5ϵℓ is interfering with the pathway 1s22s22p6 + γ → 1s22s12p63p → 1s22s22p5ϵℓ.

According to the dipole transition selection rules for linearly polarized light, the 2p atomic orbitals with mj = 1/2 can ionize to ϵs and ϵd, while the ones with mj = 3/2 can only ionize to ϵd. It is known that the partial d-wave is suppressed, while the s-wave is enhanced at the Fano resonance in neon6 (also true for 3s − 4p in argon49). This gives rise to a photon-energy-dependent structure of the mj contributions, as shown in Fig. 2 (a), where the population of the ion hole 2p, with j = 3/2, is depicted for different mj. Data for a 300 as and a 20 fs pulse, both at a peak intensity of 1013 Wcm−2, are compared. The exact duration for the attosecond and femtosecond pulses considered here are quite arbitrary, but they correspond well to typical pulse durations from high-order harmonic generation and free electron laser sources, respectively. We observe that the structure from the Fano profile is not resolved using the attosecond pulse, while for the femtosecond pulse, the structure is resolved. Due to the Fano-induced structure, the hole with mj = 1/2 is relatively more populated than the one with mj = 3/2. Clearly, the pulse duration is essential to control the hole alignment. In Fig. 2 (b), the hole alignment ratio, \({A}_{2{p}_{3/2}}^{1/2,3/2}\), given by Eq. (22), is presented as a function of the central photon energy for the attosecond and femtosecond pulses. These curves represent the ratio between the lines with different mj numbers in Fig. 2 (a). The maximum value of the ratio with the 20 fs pulse, occurring precisely at the resonant photon energy, is 1.49. With the 300 as pulse, there is no enhancement of the alignment of the holes, as the value remains fixed at 1.38 while the central photon energy is changed. This shows that it is not possible to create enhanced hole alignment using attosecond pulses with Fano resonances. In fact, the enhancement factor of the 20 fs pulse is merely 8%, compared to the ineffective 300 as pulse case, which implies that even longer pulses would be required for a higher degree of hole alignment.

a Populations of ion hole 2p, j = 3/2 with different magnetic quantum numbers in neon when {2s, 2p} orbitals are open. Two pulses are used: the first pulse has a duration of 20 fs, a \({\cos }^{2}\) envelope, the intensity of 1013 Wcm−2 (propagation time from -25 fs to 145 fs); the second pulse has a duration of 300 as, a Gaussian envelope, the intensity of 1012 Wcm−2 (propagation time from -2400 as to 7200 as). Values corresponding to the 300 as pulse are multiplied by a factor of 103. b the hole alignment ratio of populations in (a).

Argon

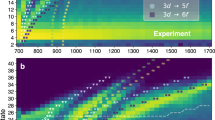

The RTDCIS cross section analysis of argon is presented in Fig. 1b within the frequency range from 25 eV to 95 eV to highlight the Cooper minimum of the outer orbital, 3p. Generally, Cooper minima exhibit a broader profile than Fano resonances in the frequency domain and may open the possibility of employing a high degree of alignment on shorter timescales. Here, the system is subjected to a linearly polarized pulse of 300 as duration with the intensity of 1012 Wcm−2. Figure 3a presents the population of the hole 3p, with j = 3/2, for different mj values as a function of the photon frequency. According to the dipole transition selection rules, linearly polarized light allows the ionization of mj = 3/2 p-electrons exclusively into the d-wave. However, due to the suppression of 3p → ϵd transitions at the Cooper minimum, the population of holes characterized by mj = 3/2 is lower than those with mj = 1/2. This is very visible in Fig. 3a, where the mj = 3/2 goes down almost two orders of magnitude, compared to the mj = 1/2.

a The populations of ion hole 3p, j = 3/2 with different magnetic quantum numbers in argon as a function of the photon energy. The system interacted with a Gaussian pulse of 300 as with the intensity of 1012 Wcm−2 In the computations, only the 3p orbital was open and propagation ran from −2400 as to 7200 as. b the hole alignment ratio of populations in (a).

This preference for the magnetic quantum number becomes further evident in the hole alignment ratio, which is plotted in Fig. 3 (b), as a function of photon energy. This strong outer hole alignment, \({A}_{3{p}_{3/2}}^{(1/2,3/2)}\) (see Eq. (22)), reaches a maximum of approximately 24 at the Cooper minimum and gradually decreases as the frequency is detuned from this value.

Next, we consider in more detail the role of the pulse duration, to find the optimal alignment for the frequency that is resonant with the Cooper minimum, 56.6 eV, which is the frequency that minimizes the d-wave. As observed in Fig. 4, by manipulating the pulse duration, the hole alignment ratio can reach large values on ultrafast timescales, reaching a value of 200 for a pulse duration of 3 fs. This means that the hole in the ion can be accurately prepared in the magnetic quantum number states with ∣mj∣ = 1/2 within a few femtoseconds. While the alignment continues to increase with the duration of the pulse, the rate of increase decreases to zero. This implies that an exact value for maximal alignment can only be reached in the asymptotic limit of long pulses.

Xenon

Figure 1c shows the theoretical RTDCIS cross section of xenon, where the giant resonance50 and the Cooper minimum51,52 are labeled by G and C, respectively.

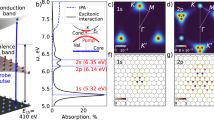

Figure 5a demonstrates the photon energy dependence of the population with ion hole 4d, with j = 5/2, for the mj quantum numbers 1/2, 3/2, and 5/2. A Gaussian pulse of 300 as with the intensity of 1012 Wcm−2 was used. The idea here is to investigate the possibility of having enhanced alignment via the Cooper minimum or the giant resonance, both of which have a broad width in the energy domain. In the giant resonance region, there is no significant difference between the partial waves which signals no preference in the magnetic quantum number around these photon energies. In contrast, the Cooper minimum in xenon results from the minimized transition rate from the d orbital to the f-wave, corresponding to mj = 5/2. As seen in Fig. 5a, the population of the mj = 5/2 hole experiences a dramatic fall at the Cooper minimum compared to the others. Populations of the mj = 1/2 and mj = 3/2 holes follow the same trend; gradually decreasing in this area.

a The populations of ion hole 4d with j = 5/2 for different magnetic quantum numbers in xenon as a function of photon energy. The same pulse parameters and propagation time as in Fig. 3 was used, and {4d, 5s, 5p} orbitals were open in the calculations. b the hole alignment ratio of populations in (a).

The hole alignment ratio for different magnetic quantum numbers, \({A}_{4{d}_{5/2}}^{({m}_{j},m{{\prime} }_{j})}\) (see Eq. (22)), is plotted in Fig. 5b as a function of photon energy with labels corresponding to different spectral features. The solid line shows the ratio between mj = 1/2 and m'j = 3/2. There is no significant alignment (1.5) because there is no mechanism that selects one over the other. In the Cooper minimum region, the dotted and dashed lines depict a significantly stronger alignment, corresponding to the proportionality of ion population with mj = 3/2 and mj = 1/2 to \(m^{{\prime}}_{j}=5/2\), respectively. The enhancement happens only for pulses that are resonant with the Cooper minimum. There is no enhancement at the giant resonance. Alignment ratio \({A}_{4{d}_{5/2}}^{(3/2,5/2)}\) reaches a peak of 141.4, while \({A}_{4{d}_{5/2}}^{(1/2,5/2)}\) goes as high as 211.7.

Next, we consider the role of the pulse duration. The hole alignment ratio is plotted in Fig. 6 for different pairs of magnetic quantum numbers at the photon energy resonant with the f-wave Cooper minimum (192.7 eV). In only 2 fs, the ratio of mj = 1/2 to \(m^{{\prime}}_{j}=5/2\) reaches a value of 1500:1, while for mj = 3/2 and \(m^{{\prime}}_{j}=5/2\), the ratio goes to 1000:1. This shows that xenon 4d hole alignment can be produced with higher precision, and on shorter timescales, than for the case of 3p in argon.

Discussion

In the study by Heinrich-Josties et al.6, the TDCIS method was employed to compute the populations of the non-relativistic ion channels in neon, from which the alignment of the ion holes, characterized by the magnetic quantum number mℓ, was extracted. To calculate the mj-based ratios, they used Clebsch-Gordan coefficients to transfer the mℓ populations to the spin-orbit-split orbitals. In our work, by employing the RTDCIS method, we directly get the population of the relativistic mj-holes. In both works, the photon energy is tuned to the 2s−1ϵp autoionizing states of neon. Before discussing the dynamics, it is important to consider the lifetime of this state. In Table 1, we compare the lifetime of the state given by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)53 with the theoretically calculated values by CIS and RCIS. The pulse duration in ref. 6 was 174 fs, which was chosen to be much longer than the lifetime of the 2s−13p state to resolve well its atomic structure. In contrast, we considered shorter pulses to study how the alignment of this hole builds up gradually with increasing pulse duration. For this reason, the ratios observed in our work, i.e. 1.38 for 300 as pulse and 1.49 for the 20 fs one, are lower than reported in ref. 6, where a maximum ratio of approximately 13 was observed. Since Fano profiles are spectrally narrow, according to the Heisenberg uncertainty relation, they require long XUV pulses to achieve high degrees of alignment. As we demonstrate by the 20 fs pulse, which is comparable to the calculated (theoretical) lifetime of the dominant state with j = 3/2 (see Table 1), one must use pulses that are considerably longer to obtain a sizable effect. The relativistic subdominant state (j = 1/2) has an even longer lifetime that would require more than twice as long pulses to achieve high alignment, compared to the non-relativistic case.

Our main targets for the study were argon and xenon, where it was shown that Cooper minima can be used to create high alignment ratios of ultrafast timescales. Looking at Fig. 3b and Fig. 4 for the case of argon, and Fig. 5b and Fig. 6 for xenon, we observe a clear connection between the short pulse duration and the broad width of Cooper minima. The fact that rise times of hole alignment for argon and xenon is similar is reasonable given their comparable width of Cooper minima in the energy domain.

Finally, it was found that the giant resonance in xenon does not distinguish between different magnetic quantum numbers. Here, we studied an inner hole (4d), which would be subject to autoionization in an experiment. Due to the limitations of the RTDCIS methodology, such an Auger-Meitner decay process (or fluorescence) is beyond the scope of the present work. However, it should be noted that the lifetime of the 4d hole in xenon, as indicated by Svensson et al.54, is 7 fs, which is long enough for strong hole alignment. This implies that the mechanism proposed here may indeed be useful for the preparation of non-stationary alignment of holes, on an ultrafast timescale, before the ion has time to further decay.

Physically, the different hole alignment properties of Cooper minima and giant resonances can be understood from how the angular momentum of the photoelectron is related to the magnetic quantum number of the hole. The mj can be efficiently controlled by reducing the angular momentum of the photoelectron compared to the hole. For the 4d Cooper minimum in Xe, the photoelectron is confined to a p-wave, because the f-wave is blocked. That means that the maximal possible j value of the electron is 3/2, which implies a maximal value of mj = 3/2. This is smaller than the magnetic quantum number of the occupied 4d electrons (maximal j and mj = 5/2). Thus, the lower value 3/2 is selected for ionization, and strong alignment is produced. The situation is the opposite for the giant resonance where the largest angular momentum is instead enhanced in photoionization (f-wave from 4d). Since the f-wave supports all magnetic quantum numbers from − 7/2 to 7/2, it covers all the possible magnetic quantum numbers of the 4d electrons: − 5/2 to 5/2. Thus no selection of magnetic quantum number is achieved and hole alignment will not be enhanced.

Conclusion

In summary, we have investigated the prevalence of hole alignment when the noble gas atoms: neon, argon, and xenon interact with femtosecond and attosecond pulses in resonance with specific spectral features. The effect of photon energy and pulse duration on hole alignment, defined as the population ratio of holes with different total magnetic quantum numbers mj, is studied in different cases.

For neon, our simulations showed that the narrow spectral width of the 2p Fano resonances does not allow for hole alignment with attosecond pulses. For high alignment values, one needs to employ hundreds of femtosecond pulses, as was done in a previous study6.

For argon, our focus on the broader spectral feature of the Cooper minimum opened up the possibility of using shorter pulses in the attosecond regime to achieve large hole alignment. Finally, we investigated hole alignment in the inner 4d shell of xenon, where the focus was on the role of broad spectral features, such as the giant resonance and the Cooper minimum. We observed that in the region of the Cooper minimum, the alignment ratios reached substantial values on the order of one thousand. Overall, we have proposed that it is possible to achieve a high degree of hole alignment in noble gas ions on ultrashort timescales. Since Cooper minima are present also in molecules, this alignment process may be relevant in more complex systems. We imagine that such aligned holes, positioned on a specific atomic site in a complex molecule, will couple and migrate differently to their molecular environment. Therefore, our work opens up the possibility for future applications in quantum state preparation or ultrafast chemistry.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The electronic source data file can be found in the Supplementary Data.

Code availability

Codes used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Svanberg, S.Atomic and Molecular Spectroscopy. Graduate Texts in Physics (Springer International Publishing, 2022). https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-04776-3.

Baltuška, A. et al. Attosecond control of electronic processes by intense light fields. Nature 421, 611–615 (2003).

Dahlström, J. M., L’Huillier, A. & Maquet, A. Introduction to attosecond delays in photoionization. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 45, 183001 (2012).

Calegari, F., Sansone, G., Stagira, S., Vozzi, C. & Nisoli, M. Advances in attosecond science. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 49, 062001 (2016).

Lindroth, E. et al. Challenges and opportunities in attosecond and xfel science. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 107–111 (2019).

Heinrich-Josties, E., Pabst, S. & Santra, R. Controlling the 2p hole alignment in neon via the 2s-3p fano resonance. Phys. Rev. A. 89, 043415 (2014).

Gryzlova, E. V., Kiselev, M. D., Popova, M. M. & Grum-Grzhimailo, A. N. Evolution of the ionic polarization in multiple sequential ionization: General equations and an illustrative example. Phys. Rev. A. 107(1), 013111 (2023).

Brown, A. C. et al. RMT: R-matrix with time-dependence. solving the semi-relativistic, time-dependent schrödinger equation for general, multielectron atoms and molecules in intense, ultrashort, arbitrarily polarized laser pulses. Comput. Phys. Commun. 250, 107062 (2020).

Carlström, S., Bertolino, M., Dahlström, J. M. & Patchkovskii, S. General time-dependent configuration-interaction singles. ii. atomic case. Phys. Rev. A 106, 042806 (2022).

Grant, I. P. (ed.) Relativistic Quantum Theory of Atoms and Molecules, vol. 40 of Springer Series on Atomic, Optical, and Plasma Physics (Springer New York, 2007). http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-0-387-35069-1.

Jönsson, P. et al. An introduction to relativistic theory as implemented in GRASP. Atoms 11, 7 (2022).

Amusia, M. Y. Photoabsorption in the One-Electron Approximation, 47–97 (Springer US, Boston, MA, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-9328-4_3) 1990.

Johnson, W. R., Lin, C. D., Cheng, K. T. & Lee, C. M. Relativistic random-phase approximation. Phys. Scr. 21, 409–422 (1980).

Vinbladh, J., Dahlström, J. M. & Lindroth, E. Relativistic two-photon matrix elements for attosecond delays. Atoms 10, 80 (2022).

Zapata, F., Vinbladh, J., Ljungdahl, A., Lindroth, E. & Dahlström, J. M. Relativistic time-dependent configuration-interaction singles method. Phys. Rev. A 105, 012802 (2022).

Greenman, L. et al. Implementation of the time-dependent configuration-interaction singles method for atomic strong-field processes. Phys. Rev. A 82, 023406 (2010).

Krebs, D., Pabst, S. & Santra, R. Introducing many-body physics using atomic spectroscopy. Am. J. Phys. 82, 113–122 (2014).

Carlson, T. A. Photoelectron spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 26, 211–234 (1975).

Starace, A. F.Theory of atomic photoionization, vol. 6/31 of Encyclopedia of Physics/Handbuch der Physik, 1–121 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1982).

Fano, U. Effects of configuration interaction on intensities and phase shifts. Phys. Rev. 124, 1866–1878 (1961).

Cooper, J. W. Photoionization from outer atomic subshells. a model study. Phys. Rev. 128, 681–693 (1962).

Cooper, J. W. Interaction of maxima in the absorption of soft x-rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 762–764 (1964).

Ederer, D. L. Photoionization of the 4d electrons in xenon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 760–762 (1964).

Amusia, M. Y. & Connerade, J.-P. The theory of collective motion probed by light. Rep. Prog. Phys. 63, 41 (2000).

Pabst, S., Greenman, L., Mazziotti, D. A. & Santra, R. Impact of multichannel and multipole effects on the cooper minimum in the high-order-harmonic spectrum of argon. Phys. Rev. A 85, 023411 (2012).

Schoun, S. B. et al. Attosecond pulse shaping around a copper minimum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 153001 (2014).

Alexandridi, C. et al. Attosecond photoionization dynamics in the vicinity of the cooper minima in argon. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, L012012 (2021).

Klünder, K. et al. Probing single-photon ionization on the attosecond time scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 143002 (2011).

Palatchi, C. et al. Atomic delay in helium, neon, argon, and krypton*. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 47, 245003 (2014).

Ott, C. et al. Lorentz meets Fano in spectral line shapes: A universal phase and its laser control. Science 340, 716–720 (2013).

Kheifets, A. S. Time delay in valence-shell photoionization of noble-gas atoms. Phys. Rev. A 87, 063404 (2013).

Saha, S. et al. Relativistic effects in photoionization time delay near the cooper minimum of noble-gas atoms. Phys. Rev. A 90, 053406 (2014).

Mazza, T. et al. Sensitivity of nonlinear photoionization to resonance substructure in collective excitation]. Nat. Commun. 6, 6799 (2015).

Magrakvelidze, M., Madjet, M. E.-A. & Chakraborty, H. S. Attosecond delay of xenon 4d photoionization at the giant resonance and Cooper minimum. Phys. Rev. A 94, 013429 (2016).

Goulielmakis, E. et al. Real-time observation of valence electron motion. Nature 466, 739–743 (2010).

Mehmood, S., Lindroth, E. & Argenti, L. Ionic coherence in resonant above-threshold attosecond ionization spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 107, 033103 (2023).

Yuen, C. H. & Lin, C. D. Density-matrix approach for sequential dissociative double ionization of molecules. Phys. Rev. A 106, 023120 (2022).

Yuen, C. H. & Lin, C. D. Coherence from multiorbital tunneling ionization of molecules. Phys. Rev. A 108, 023123 (2023).

Yuen, C. H. & Lin, C. D. Probing vibronic coherence in charge migration in molecules using strong-field sequential double ionization. Phys. Rev. A 109, L011101 (2024).

Rohringer, N., Gordon, A. & Santra, R. Configuration-interaction-based time-dependent orbital approach for ab initio treatment of electronic dynamics in a strong optical laser field. Phys. Rev. A 74, 043420 (2006).

Sato, T., Pathak, H., Orimo, Y. & Ishikawa, K. L. Time-dependent multiconfiguration self-consistent-field and time-dependent optimized coupled-cluster methods for intense laser-driven multielectron dynamics. Can. J. Chem. 101, 698–709 (2023).

Dreuw, A. & Head-Gordon, M. Single-reference ab initio methods for the calculation of excited states of large molecules. Chem. Rev. 105, 4009–4037 (2005).

Fischer, C. F. & Zatsarinny, O. A b-spline Galerkin method for the Dirac equation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 879–886 (2009).

Riss, U. V. & Meyer, H. D. Calculation of resonance energies and widths using the complex absorbing potential method. J. Phys. B 26, 4503 (1993).

Leforestier, C. et al. A comparison of different propagation schemes for the time-dependent schrödinger equation. J. Comput. Phys. 94, 59–80 (1991).

Sakurai, J. J. & Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

You, J.-A., Rohringer, N. & Dahlström, J. M. Attosecond photoionization dynamics with stimulated core-valence transitions. Phys. Rev. A 93, 033413 (2016).

Carlström, S., Dahlström, J. M., Ivanov, M. Y., Smirnova, O. & Patchkovskii, S. Control of spin polarization through recollisions. Phys. Rev. A 108, 043104 (2023).

Carette, T., Dahlström, J. M., Argenti, L. & Lindroth, E. Multiconfigurational hartree-fock close-coupling ansatz: Application to the argon photoionization cross section and delays. Phys. Rev. A 87, 023420 (2013).

Wendin, G. Collective resonance in the 4d10 shell in atomic xe. Phys. Lett. A 37, 445–446 (1971).

Kutzner, M., Radojević, V. & Kelly, H. P. Extended photoionization calculations for xenon. Phys. Rev. A 40, 5052–5057 (1989).

Lindle, D. W., Ferrett, T. A., Heimann, P. A. & Shirley, D. A. Photoemission from xe in the vicinity of the 4d cooper minimum. Phys. Rev. A 37, 3808–3812 (1988).

National Institute of Standards and Technology. Nist atomic spectra database https://www.nist.gov/pml/atomic-spectra-database (2024).

Svensson, S. et al. Lifetime broadening and ci-resonances observed in esca. Phys. Scr. 14, 141 (1976).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Eva Lindroth and Dr. Jimmy Vinbladh for the useful discussions. JMD acknowledges support from the Olle Engkvist Foundation: 194-0734 and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation: 2019.0154.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.T. and J.M.D. wrote the manuscript with feedback from A.P, S.C., and F.Z. R.T. performed simulations and analyzed the results using codes developed by A.P., F.Z., and J.M.D. F.Z. co-supervised R.T., and J.M.D. was the principal investigator.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tahouri, R., Papoulia, A., Carlström, S. et al. Relativistic treatment of hole alignment in noble gas atoms. Commun Phys 7, 344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01833-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01833-0