Abstract

Field-particle energy exchange is important to the magnetic reconnection process, but uncertainties regarding the time evolution of this exchange remain. We investigate the temporal dynamics of field-particle energy exchange during magnetic reconnection, using Magnetospheric Multiscale mission observations of an electron-only reconnection event in the magnetosheath. The electron energy is in local minimum at the x-line due to a density depletion, while the magnetic energy is in local maximum due to a guide field enhancement. The electromagnetic energy transport comes almost entirely from guide field contributions and is confined within the reconnection plane, while the most significant contribution to electron energy transport is independent of the drift velocity with additional out-of-plane signatures. Multi-spacecraft analysis suggests that the guide field energy is decreasing while the electron density is increasing, both evolving such that the system is moving toward a more uniform distribution of magnetic and thermal energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Field-particle energy exchange processes in collisionless plasmas are often associated with the evolution of highly non-Maxwellian phase space structures, suggesting a thermodynamic process where the path that energy takes toward dissipation involves localized reductions in kinetic entropy1,2. Despite the lack of an obvious dissipative mechanism, collisionless reconnection is irreversible3 and collisionless systems tend to exhibit “collisional-like” behavior4 in particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations. Recent theoretical insights regarding the pressure strain interaction term have also provided a more detailed picture of energy conversion processes in systems far from local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE)5,6.

Despite recent insights on the thermodynamic processes of collisionless reconnection, it is still unclear how the evolution of the local magnetic field influences local thermodynamics. One way to address this problem is by directly measuring the flow of energy and its relationship to the time evolution of the energy density structures in a reconnecting system. Energy continuity dictates a direct relationship between the local time evolution of energy density and the various energy fluxes that may be present.

where ut,uk, and uem are the thermal (pressure), kinetic (bulk motion), and electromagnetic energy densities, respectively. The energy fluxes \(\overrightarrow{H}\),\(\overrightarrow{K}\),\(\overrightarrow{Q}\),and \(\overrightarrow{K}\) are the enthalpy flux (thermal convection), kinetic energy flux (bulk flow), heat flux (asymmetry in the distribution function), and Poynting flux (electromagnetic energy flow), respectively. In the non-relativistic limit, the standard energy densities and energy fluxes are defined7,8 by

where n is the particle density, m is the particle mass, \(\overrightarrow{v}\) is the velocity, \(\overleftrightarrow{P}\) is the pressure tensor, \(\overrightarrow{E}\) is the electric field, and \(\overrightarrow{B}\) is the magnetic field. Previous studies9,10 have presented in-situ observations of the various energy fluxes associated with reconnection and found that the ion enthalpy flux typically dominates in the outflow with smaller, more filamentary contributions from electron enthalpy flux. Measurements of heat flux are not presented in this article for reasons explained in the methods.

Modern reconnection models emphasize the importance of charge separation effects in the dynamics and rate of magnetic reconnection. Due to their different masses, and therefore different gyroradii, ions and electrons demagnetize at different length scales and create an electron diffusion region (EDR) embedded within a larger ion diffusion region (IDR). As a consequence, additional Hall electromagnetic fields can develop in the IDR due to current-carrying electrons following the field lines while ions are demagnetized. These Hall currents are an important kinetic mechanism underlying the source of the electric fields associated with fast reconnection in the IDR11,12,13,14,15, and the Hall electromagnetic fields can influence the Poynting flux structure in the reconnection exhaust and allow more rapid energy transport and higher reconnection rates16,17. Direct in-situ observations of the EDR at the magnetopause18 and in the magnetotail19 have been previously reported and have demonstrated the importance of electron-scale kinetic physics to the transfer of electromagnetic energy to particles. In-situ measurements of the terms in the generalized Ohm’s law found that the divergence of the electron pressure tensor is the most significant contribution to energy dissipation in the EDR, though there are also contributions from electron inertial effects20.

New observations have complicated the Hall reconnection model and the concept of embedded EDR-IDR structures. Within the last few years a unique form of magnetic reconnection has been observed in which only the electrons take part in the reconnection process without the presence of a traditional IDR. Recent studies21,22 have suggested that electron-only reconnection may be an early stage of traditional reconnection, after onset but before the ions begin to respond to the local Hall fields and gain energy. This is also supported by an earlier analysis23 which found that ion participation can be prevented if the domain size is sufficiently small in PIC simulations of reconnection. An electron-only reconnection event was first observed24 by the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission in the turbulent magnetosheath, including an interval in which both inflows and outflows of the x-line were observed simultaneously by the four spacecraft. Due to the relative positions of the MMS spacecraft and the x-line, this magnetosheath event24 provides a unique opportunity to study the energy transport processes of an electron-only x-line. This event is also well-suited to the analysis of non-equilibrium reconnection dynamics because it exists within a turbulent environment which may provide highly variable inflow conditions.

The following study is a detailed analysis of the electromagnetic and thermal evolution of an electron-only reconnection event24. In the Methods section, the methods behind our analysis is presented in more detail. In the Results section, we present the observed energy density structure of the x-line and various other terms relevant to the electromagnetic and electron thermal energy densities (“Energy Density Structure” subsection), we describe how energy is being transported near the x-line by examining the local energy flux structures, their divergences, and the primary terms contributing to them (“Energy Flow Structure” subsection), and we use multi-spacecraft techniques to take local measurements of the time-evolution of various terms relevant to energy conversion and local thermodynamic evolution of the electrons (“Local Time Evolution” subsection). In the Discussion section, we discuss the results of the previous sections and what they imply about the relationship between collisionless reconnection and the “arrow of time”. The Conclusions section summarizes our findings.

Methods

MMS Instrumentation

This study uses high-time resolution burst mode data from the suite of particle and field instruments aboard MMS. Magnetic field data come from the fluxgate magnetometers (FGM), which measure magnetic field vectors at a cadence of 128 samples per second25. Electric field data come from the electric field double probes (EDPs), which measure spin plane26 and axial27 components of the electric field at 8,192 samples per second. Particle data come from the electron and ion spectrometers part of the fast plasma investigation (FPI)28.

The most significant sources of error that may affect the results in the following sections come from the FPI moments data. Within the time interval in this article the electron velocity \({\overrightarrow{v}}_{e}\), temperature \(\overleftrightarrow{{T}_{e}}\), and density ne have approximate relative errors of 0.1, 0.01, and 0.005, respectively. The errors associated with each parameter are taken directly from the FPI data products28.

X-line Reference Frame

All vector quantities in this study are presented in a previously defined24 current sheet normal LMN coordinate system, and are transformed into the x-line reference frame to isolate energy fluxes associated with the reconnection process from energy fluxes associated with the overall motion of the x-line relative to MMS. The electric field \(\overrightarrow{E}\) and electron velocity \({\overrightarrow{v}}_{e}\) are transformed into their x-line frame equivalent with the x-line velocity \({\overrightarrow{v}}_{xl}\), which is taken to be the ion velocity measured at the center of the EDR crossing as is the case in other similar studies9.

While it is possible that the ion reference frame and the x-line reference frame may not be explicitly identical, the ion reference frame is still an appropriate choice at the center of the x-line since it represents the local center-of-mass frame and it isolates the electron energy fluxes from the background (non-reconnecting) ion flow. The above relations can be used to transform any of the energy fluxes or energy densities mentioned in the introduction. In the non-relativistic regime, quantities such as \(n,Tr(\overleftrightarrow{P})\), and \(\overrightarrow{B}\) are frame-independent, and therefore do not need to be altered from the direct MMS data products. In the following sections, the heat flux \(\overrightarrow{Q}\) will be neglected, due to the lack of significant signal that can be distinguished from the noise.

Calculating Time Derivatives

This work also requires evaluations of time derivatives to isolate the temporal evolution from the spatial evolution as MMS observes a passing structure. The standard method of evaluating the time derivative of an arbitrary scalar γ in a co-moving fluid frame is to use a convective derivative:

where \(\frac{d\gamma }{dt}\) is the time derivative in the MMS frame, and ∇ γ is calculated using multi-spacecraft techniques29. For variables with multiple contributions to the product, such as ute ∝ neTe, the temporal derivative is broken down into its separate contributions.

The terms in angled brackets represent a simple four-spacecraft average, while the partial derivatives are determined via standard multi-spacecraft methods29.

Validity of Linear Gradient Approximation

This work also utilizes multi-spacecraft techniques29 to calculate energy flux divergences and the directional contributions to their sum. However, there are several limitations to these methods that should be mentioned. The first is that they assume that similar measurements vary linearly between any two spacecraft. A common test for the reliability of this assumption is to see how well the curlometer current density \({\overrightarrow{J}}_{curl}=\frac{\nabla \times \overrightarrow{B}}{{\mu }_{0}}\) matches the spacecraft-averaged moments current density \({\overrightarrow{J}}_{mom}\) calculated by FPI. In this case there is reasonable agreement between the current density via both methods (see Figure S1 in supplementary note 1), suggesting that the barycentric quantities in this study are reasonably well-resolved. The second limitation has to do with the determination of divergences, and how the net divergence of a given quantity may be affected due to the timing of encounters with the inflows or outflows between spacecraft, even if the separate component contributions to the sum are reliable. An illustration explaining this is also provided in Figure S2 in supplementary Note 1.

Results

Energy Density Structure

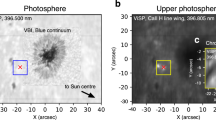

The left panel of Fig. 1 presents the electromagnetic energy density (uem), electron thermal energy density (ute) and their sum observed during the encounter by MMS2. uem is larger than ute, and it is in a local maximum compared to its surroundings, whereas ute is in a local minimum. The local enhancement in uem is larger than the ute depletion and results in a local enhancement in the sum of the two terms.

(a) Electromagnetic and (b) electron thermal energy densities from MMS2, (c) Magnetic field components from MMS2, Diagonal components of the (d) electron pressure tensor, (e) temperature tensor, and (f) the electron density. Separate L, M, N contributions to the terms in panels c–e are colored blue, green, and red, respectively. The shaded intervals represent the full x-line crossing and the dashed lines represent the times of the first and last encounter of the x-line center (where BL = 0) by MMS4 and MMS2, respectively.

Figure 1 further highlights the source of these energy densities. The most significant contribution to uem and its local enhancement is the large guide field BM associated with the event. Depletion in ute comes primarily from a depletion in ne, rather than Te. The electron pressure Pe and its depletion are not fully isotropic, but instead are largely within the LN plane, with a negligible PeMM contribution parallel to the guide field.

The large guide field BM in this event causes the local field curvature radius, defined as \({R}_{c}=\frac{1}{| \hat{b}\cdot \nabla \hat{b}| }\) (\(\hat{b}\) is the magnetic unit vector) to be relatively large. Figure 2 compares the local Rc with the thermal gyroradii of both the ion and electron populations (Ri and Re, respectively). Rc is larger than Ri and much larger than Re, suggesting that the electrons are well-magnetized even near the x-line.

Energy Flow Structure

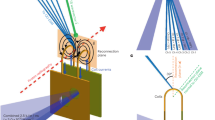

The energy flux densities observed by all the MMS spacecraft are shown in Fig. 3. The Poynting flux \(\overrightarrow{S}\) is predominantly along the L and N axes, with simultaneous observations of both inflow SN components by MMS 2 and 4 and of both outflow SL components by MMS 1 and 3. Unlike \(\overrightarrow{S}\), there is a large HeM component observed by all spacecraft, which is approximately parallel to the local magnetic field due to the large BM present over the interval. There are also smaller contributions by HeL and HeN. The kinetic energy flux structure has spikes in KeL and KeM, but they are an insignificant contribution compared to the overall energy transport in the system.

Poynting flux (panels a1-a4), electron enthalpy flux (b1-b4) and electron kinetic energy flux (c1-c4) components observed by each spacecraft with a diagram depicting the approximate trajectory of MMS through the energy flow structures. The L, M, N components of all terms are colored blue, green, and red, respectively. The Poynting and electron enthalpy structures in the diagram are depicted in black and green, respectively, while the MMS spacecraft are depicted as red dots with red dashed arrows indicating their direction of motion relative to the x-line.

Figure 4 presents the breakdown of the individual components of \(\overrightarrow{S}\) from MMS 2 into separate contributions from different field components, as well as a comparison of \({\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\) without the ‘drift’ enthalpy flux HeD, which is defined here as the electron enthalpy flux associated with the electron \(\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}\) drift velocity.

where \({v}_{d}=\frac{\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}}{{B}^{2}}\). The results indicate that the HeM contribution is largely independent of the \(\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}\) drift, and that \(\overrightarrow{S}\) is dominated by guide field contributions along with electric fields in the LN plane.

a Total electron enthalpy flux from MMS2 and (b) the enthalpy flux excluding the drift contribution, where the L, M, N contributions in panels a, b are colored blue, green, and red, respectively. Contributions to the (c) L and (d) N components of Poynting flux, where the terms in green represent contributions by in-plane electric fields and the guide field, and the terms in red represent contributions from the reconnecting magnetic field components and the reconnection electric field.

Figure 5 shows the calculated divergences of the energy fluxes from Fig. 3 using standard multi-spacecraft techniques29. \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\) is the most significant term with somewhat comparable ∂LSL > 0 and negative ∂NSN < 0, though the ∂NSN contribution is generally larger and produces a net negative \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\) between the first and last encounter of the x-line center. The net \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\) consists of a local minimum magnitude of \(| \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}| \approx 10-30\,nW/{m}^{3}\) adjacent to two larger spikes of \(| \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}| \approx 70-100\,nW/{m}^{3}\). \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\) consists of roughly balanced ∂LHeL > 0 and ∂NHeN < 0, with an additional ∂MHeM < 0 contribution resulting in a net negative \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\), which peaks in magnitude at \(| \nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}| \approx 50\,nW/{m}^{3}\) around the same time of the local minimum magnitude \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\). At its peak, the magnitude of enthalpy flux divergence exceeds that of the Poynting flux divergence \(| \nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}| > | \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}|\) (interval highlighted in orange in Fig. 5). Though the magnitude of \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{K}}_{e}\) is negligible, it still exhibits some interesting structure that distinguishes it from \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\). \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{K}}_{e}\) has net positive spikes, one before the first encounter of the x-line center and one near the last encounter, with a comparably small negative spike in between. \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{K}}_{e}\) is comparably small in the center due to roughly balanced ∂LKeL > 0 and ∂MKeM < 0, whereas the positive spikes mostly come from an imbalance between ∂MKeM > 0 and ∂LKeL < 0.

Includes divergence of (a) Poynting flux, (b) electron enthalpy flux, and (c) electron kinetic energy flux, where the totals are in black and the L, M, N contributions are in blue, green, and red, respectively. The grey shaded interval represents the full x-line crossing, the dashed lines represent the times of the first and last encounter of the x-line center, and the orange shaded interval represents the observation of the local \(| \nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}|\) maximum and \(| \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}|\) minimum.

Local Time Evolution

Figure 6 presents the local time evolution of the electron thermal ute and electromagnetic uem energy densities, as well as the power density of energy transfer \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) broken down into its separate contributions. uem is locally decreasing with time at a rate similar to the spacecraft averaged \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) at its peak. Further decomposition of uem into separate magnetic field component contributions suggests that the magnetic energy loss at the center of the reversal is almost entirely due to a loss in guide field energy density.

Power density of (a) field-to-particle energy transfer, b magnetic energy evolution, and c electron thermal energy evolution. The separate L, M, N contributions to the terms in panels a–b are colored blue, green, and red, respectively. The separate contributions by density evolution and temperature evolution in panel c are colored blue and red, respectively. The grey-shaded region represents the x-line crossing interval, the dotted lines represent the center of the BL reversal observed by MMS 4 and 2, and the orange shaded interval represents the observation of the local \(| \nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}|\) maximum and \(| \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}|\) minimum from Fig. 5.

Figure 6 also shows the temporal evolution of ute and its separate contributions. The results suggest that the local ute is increasing, but at a smaller magnitude than that of the guide field energy loss. The increasing ute is largely due to the increase in ne rather than Te. The electrons are therefore being locally compressed with minimal temperature enhancement while the local guide field is decreasing. A comparison of the separate contributions to the total convective derivative can be found in supplementary Note 2, Figure S3.

Discussion

This particular event has both a strong background guide field BM and a local BM enhancement at its center, whereas the electron density ne is a local minimum compared to its surroundings. This results in a ute depletion within a uem enhancement, though it should be emphasized that these two features do not appear to balance one another (Fig. 1) due to the uem enhancement being larger than the ute depletion. The result is an electron-scale feature that has a non-uniform distribution of energy density. The thermal energy density ute and the scalar pressure Pe are directly proportional to one another where Pe = 2ute/3. Therefore, Pe is smaller than ute and the feature is also not in local pressure balance. The “Energy Flow Structure” and “Local Time Evolution” subsections in the Results provided a detailed look at the mechanisms that influence the system’s path toward a local equilibrium.

The strong BM responsible for the locally enhanced energy density also heavily influences the local energy flow structures by causing \(\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}\) to largely be confined to the LN plane. This influences both the Poynting flux \(\overrightarrow{S}\) and the ‘drift’ enthalpy flux \({\overrightarrow{H}}_{eD}\) (Figs. 3 and 4). The decomposition of SL and SN (Fig. 4) demonstrate that magnetic energy transport comes almost entirely from BM contributions and in-plane electric fields, suggesting that the reconnection electric field EM is not a significant mechanism of electromagnetic energy transport in this case (although this does not mean EM is unimportant to the reconnection process). In contrast, HeM is typically the largest component of \({\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\) (Fig. 3). The HeL and HeN terms can be significant, but are largely due to the strong \({\overrightarrow{H}}_{eD}\) that comes from the \(\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}\) drift. The HeM contribution is mostly independent of \({\overrightarrow{H}}_{eD}\) (Fig. 4), and distinct from \(\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}\) drift effects. The electric and magnetic field structures of this event have been previously examined in detail30, but not the energy flow structures as we have examined here.

The energy flux divergences in Fig. 5 highlight the spatial variability of energy transport. Overall, the most significant term is \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S} < 0\), in particular the strong ∂NSN < 0 and ∂LSL > 0 contributions associated with the electromagnetic energy inflows and outflows, respectively. The transport of electron thermal energy also has these inflow and outflow signatures. There are ∂NHeN < 0 and ∂LHeL > 0 contributions that approximately balance each other out, but unlike \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\) there is also a strong ∂MHeM < 0 contribution that makes \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e} < 0\). That is, the negative \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\) is confined to the reconnection plane while the negative \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\) is significantly influenced by its out-of-plane contribution. Since all four spacecraft measured HeM in the same direction (Fig. 3), this signature of ∂MHeM < 0 is not indicative of converging thermal flows in the x-line frame, but it may be due to more thermal energy flowing along M into one side of the tetrahedron than out the other. Though it is insignificant in magnitude, \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{K}}_{e}\) also has a considerable ∂MKeM < 0 term that almost balances its ∂LKeL > 0 contribution due to the outflows. The contributions to \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{K}}_{e}\), though negligible, are confined to the plane of the current sheet. It is not entirely clear what role variability along M could play, but the existence of 3D structure in this particular event is consistent with an earlier study30, and it is also consistent with another study9 of an EDR at the magnetopause that found significant out-of-plane electron energy flux structures suggesting the existence of mesoscale 3D effects. A recent statistical analysis31 of EDRs observed at the dayside magnetopause also found that significant positive and negative ∂MHeM contributions are common, suggesting that variable thermal energy transport along the M direction may be a ubiquitous and important aspect of reconnection generally. The 3D effects may also be important to the reconnection rate of electron-only reconnection, as it has been shown32 that 3D electron-only reconnection can allow for higher reconnection rates than in 2D due to the differential mass flux along the M direction allowing for faster inflows.

At its largest, \(| \nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}| > | \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}|\) where \(| \nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}|\) is in a local minimum (orange shaded interval in Fig. 5). This brief interval occurs just after the first encounter of the x-line center by MMS 4 coinciding with the maximum \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E} > 0\) and with the largest power density associated with \(\frac{\partial {u}_{te}}{\partial t} > 0\), but not with the maximum \(\frac{\partial {u}_{em}}{\partial t} < 0\) near the last encounter of the x-line center by MMS 2 (Fig. 6). Within this brief interval, \(\frac{\partial {u}_{em}}{\partial t}\approx 0\) and Poynting’s theorem is nearest to closure with \(-\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\approx 10-30\,nW/{m}^{3}\) and \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\approx 5\,nW/{m}^{3}\). The averaged \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) shown in Fig. 6 is smaller than the individual measurements by the MMS spacecraft since they measure its peak at different times. If we were to consider the maximum magnitudes observed by individual spacecraft, which are closer to \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\approx 10-20\,nW/{m}^{3}\)24,30, then Poynting’s theorem could be close to balanced \((\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\approx -\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S})\) in the short interval with the maximum\(\frac{\partial {u}_{te}}{\partial t} > 0\) (Figs. 5 and 6). Although they do not occur simultaneously (or in the same exact location on the x-line), the maximum \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) early in the interval is comparable to the maximum \(\frac{\partial {u}_{em}}{\partial t} < 0\) late in the interval, which is mainly due to the loss of guide field energy.

The mechanism that relates magnetic topological changes to the observed electron compression (Fig. 6) at the x-line is worth further consideration. It has been shown that the electrons are well-magnetized (Fig. 2) due to the strong BM that reduces magnetic curvature across the x-line. Local reduction in BM is equivalent to local reduction in the magnetic curvature radius Rc and a contraction in the magnetic topology along M. One would expect the magnetized electrons to closely follow such topology changes, and compress to higher density as the magnetic field contracts. A simple illustration of this mechanism is presented in Fig. 7. While the magnitude of magnetic energy loss may not be fully accounted for by this mechanism, this serves as a potential explanation for why compressive work and guide field reduction are related processes in sheared magnetic fields.

Diagram depicting the isothermal compression of magnetized electrons due to the local reduction of the radius of curvature, where BM is the guide field, Rc is the magnetic radius of curvature, and ne is the electron density. The blue dots are representative of magnetized electrons along the field line, and the red arrows indicate how the structure evolves with time.

It is not clear what may fully account for the loss rate of guide field energy or the similar \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) contribution if not the electron compression. Additional contributions could come from ions if they undergo a similar compressive mechanism, which is possible since the local Rc is larger than Ri by roughly an order of magnitude at the x-line center (Fig. 2). There is insufficient FPI ion data along the interval to reliably determine their temporal evolution and spatial derivatives via techniques described in the methods. However, if it is assumed that the plasma is locally quasi-neutral during the compression, then \(\frac{\partial {n}_{i}}{\partial t}\approx \frac{\partial {n}_{e}}{\partial t}\). \(\frac{\partial {u}_{ti}}{\partial t}\) could therefore be estimated based on the temperature ratio for this event, which is approximately Ti/Te ≈ 10. The power density associated with ion compression would therefore be roughly an order of magnitude larger than that of the electron density compression \(\frac{\partial {u}_{ti}}{\partial t}\approx 10-15\,nW/{m}^{3}\), which is larger than the averaged \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) presented here, but is similar in magnitude to the maximum measured \(\overrightarrow{J}\cdot \overrightarrow{E}\) in previous studies of this event24,30. Since there is scale separation between the ions and electrons (Ri > Re), their dynamics may differ. If local fluctuations in electron density are smaller than ion density fluctuations, there may be small-scale non-neutral regions that exhibit electric fields due to local charge separation. Analysis of multi-species compression and its relationship to energy dissipation may be a worthy topic for future studies.

The purpose of this study was to address three questions: 1) What is the distribution of energy for this event? 2) Where is the energy flowing? 3) How is the structure changing in time? All of the previous analysis is in service of a more fundamental question: Why is the system evolving this particular way? Macroscopic systems tend to have a preferred direction in phase space along which they evolve, despite the laws of physics being fully reversible at kinetic scales. This emergent “arrow of time” explains classic thermodynamic phenomena as a consequence of the mean behavior of many colliding particles. Despite the lack of the traditional collisional mechanism, evidence suggests that collisionless dissipation exhibits statistical properties similar to those in collisional systems4, and that collisionless reconnection is an entropy-producing1 and irreversible3 process. It is therefore worth reflecting on the results of the preceding sections from this perspective.

The results of the preceding sections suggest that as a density depletion is being filled in, a local guide field enhancement is being reduced (Fig. 6), thereby pushing the ratio of electron thermal pressure to magnetic pressure (βe = Pe/uem) closer to its upstream value while the locally enhanced total pressure decreases. The observed trend toward a local equilibrium begs the question of how a local non-equilibrium state as observed in Fig. 1 developed in the first place. Since this is an in-situ measurement over a short time interval, the preceding dynamics that led to the observed state of the system in the “Energy Density Structure” subsection of the Results can only be left to speculation. Due to the turbulent environment in which this x-line exists, the upstream conditions may be highly variable. Such variability in the local conditions would mean that there is variability in what the local equilibrium state should be. For example, it may be the case that local pressure balance was disrupted due to a reduction in the upstream guide field strength and/or an increase in the upstream density, leaving behind a guide field enhancement within a density depletion. Previous studies have demonstrated considerable variability in the guide field associated with electron-only reconnection in the magnetosheath, and have suggested that electron-only reconnection may be more prevalent in turbulent environments33,34. A more detailed analysis of non-equilibrium reconnection dynamics may be needed, and will likely require the aid of PIC simulations in future studies. Recent progress has been made with a study that suggests non-equilibrium current sheet dynamics can play an important role in reconnection onset35.

The nearly isothermal electron compression at the x-line is a form of compressive work6 on the local electron population. Isothermal processes are associated with an exchange of thermodynamic heat Q with the surroundings in order to sustain a constant temperature. In this case the electron population is compressed, which reduces the local position-space kinetic entropy and must result in a loss of heat from the electrons in the compressed region to the surroundings ΔQe = − ΔQsurr < 0. The most significant transport of thermal energy that is not associated with drift velocity is the HeM component of electron enthalpy flux, which is parallel to the negligible component of the anisotropic pressure PeMM. For reasons mentioned in the methods, the measurements of heat flux \({\overrightarrow{Q}}_{e}\) are not included. Previous studies have found heat flux signatures comparable in magnitude to the enthalpy flux9,31, suggesting that heat flux can significantly influence the energy budget of reconnection. While the heat flux could play an important role in the transfer and transport of energy during reconnection, it is unclear whether it is significant for this event.

This system appears to undergo a multi-step process of field-to-thermal energy transfer where excess guide field energy loss drives local isothermal compression, which increases the local pressure, expels heat into its surroundings, drives thermal energy transport down the local pressure gradient and pushes the system toward a more balanced configuration. It implies a relationship between energy transfer and entropy production in a system that is collisionless. A simple diagram depicting this magneto-thermodynamic system is included in Fig. 8.

Diagram depicting the magneto-thermodynamic process observed, where the boxes represent the interacting “systems”: the local electromagnetic fields, the local electrons, and the surroundings. Magnetic compressive mechanism (red arrows) does work to increase the local electron thermal energy density ute, decreasing the magnetic energy density uem and guide field BM within the diffusion region (dotted circle) while heat, Q (green arrows) is expelled from the local compressed region, resulting in a local reduction in position-space kinetic entropy.

It is important to consider whether the observed time variation in this study is fundamentally related to the reconnection process or whether is merely a consequence of the turbulent environment. This is a difficult question to answer based on the results of this study. One should expect any current sheet, reconnecting or not, to evolve in such a way that the system tries to approach a more rather than less balanced state. However, reconnection may expedite this process by allowing for the rapid convection of excess guide field energy along L (Fig. 4 due to the emergence of the x-line geometry and the influence of Hall EN structures. Distinguishing characteristics of reconnection from those of turbulence may also be a particularly difficult problem as both processes can influence each other either in the form of reconnection-driven turbulence or turbulence-driven reconnection, making it difficult to make any generally applicable statement about which is the “cause” and which is the “effect”34,36,37,38.

Conclusion

We have analyzed the dynamics of energy transport and transfer for an electron-only reconnection event observed in the magnetosheath. First, we determined the energy density structure of the system, exhibited by a local depletion in electron thermal energy (via density) with an enhancement in the magnetic energy density (via the guide field) at the center of the x-line. Next, we performed an analysis of the various means by which magnetic and electron thermal energy flowed in the system, finding that the transport of electromagnetic energy came in the form of guide field energy transport via in-plane electric fields while the largest contribution to electron thermal energy transport was roughly parallel to the guide field and independent of the \(\overrightarrow{E}\times \overrightarrow{B}\) drift motion. We also examined the various contributions to the divergence of the energy fluxes and found that a negative \(\nabla \cdot \overrightarrow{S}\) was largest and confined to the LN plane while there was also a considerable negative \(\nabla \cdot {\overrightarrow{H}}_{e}\) with contributions in all 3 dimensions. Lastly, we measured the temporal evolution of magnetic and electron thermal energy density in the ion reference frame, finding that the magnetic energy was decreasing via guide field reduction while the electron thermal energy was increasing via density enhancement.

Data availability

The MMS data used in this study are also stored at the Science Data Center (SDC) in Boulder, CO and can be accessed at https://lasp.colorado.edu/mms/sdc/.

Code availability

The Python notebook used to compute energy fluxes, densities as well as divergence and curl calculations is provided as supplementary software.

References

Argall, M. et al. Theory, observations, and simulations of kinetic entropy in a magnetotail electron diffusion region. Phys. Plasmas 29, 022902 (2022).

Liang, H. et al. Kinetic entropy-based measures of distribution function non-maxwellianity: Theory and simulations. Journal of Plasma Physics86(5) (2020).

Xuan, M., Swisdak, M. & Drake, J. The reversibility of magnetic reconnection. Phys. Plasmas 28, 092107 (2021).

Bandyopadhyay, R. et al. Collisional-like dissipation in collisionless plasmas. Physics of Plasmas30(8) (2023).

Cassak, P.A., & Barbhuiya, M.H. Pressure–strain interaction. i. on compression, deformation, and implications for pi-d. Phys. Plasmas. 29(12) (2022).

Cassak, P. A., Barbhuiya, M. H., Liang, H. & Argall, M. R. Quantifying energy conversion in higher-order phase space density moments in plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 085201 (2023).

Birn, J., & Hesse, M. Energy release and conversion by reconnection in the magnetotail. Annales Geophysicae. 23, 3365–3373 (2005).

Birn, J., & Hesse, M. Energy release and transfer in guide field reconnection. Phys. Plasmas. 17, (2010).

Eastwood, J. et al. Energy flux densities near the electron dissipation region in asymmetric magnetopause reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 265102 (2020).

Eastwood, J. P. et al. Energy partition in magnetic reconnection in earth’s magnetotail. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 225001 (2013).

Mandt, M., Denton, R. & Drake, J. Transition to whistler mediated magnetic reconnection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 21, 73–76 (1994).

Challenge, R. Geospace environmental modeling (gem) magnetic. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 3715–379 (2001).

Huba, J. & Rudakov, L. Hall magnetic reconnection rate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 175003 (2004).

Macek, W., Silveira, M., Sibeck, D., Giles, B. & Burch, J. Magnetospheric multiscale mission observations of reconnecting electric fields in the magnetotail on kinetic scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10295–10302 (2019).

Macek, W., Silveira, M., Sibeck, D., Giles, B. & Burch, J. Mechanism of reconnection on kinetic scales based on magnetospheric multiscale mission observations. Astrophys. J. Lett. 885, 26 (2019).

Liu, Y.-H. et al. First-principles theory of the rate of magnetic reconnection in magnetospheric and solar plasmas. Commun. Phys. 5, 1–9 (2022).

Payne, D., Torbert, R., Germaschewski, K., Forbes, T. & Shuster, J. Relating the phases of magnetic reconnection growth to energy transport mechanisms in the exhaust. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 129, 2023–032015 (2024).

Burch, J. & Phan, T. Magnetic reconnection at the dayside magnetopause: Advances with mms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8327–8338 (2016).

Torbert, R. et al. Electron-scale dynamics of the diffusion region during symmetric magnetic reconnection in space. Science 362, 1391–1395 (2018).

Torbert, R. B. et al. Estimates of terms in ohm’s law during an encounter with an electron diffusion region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5918–5925 (2016).

Hubbert, M. et al. Electron-only reconnection as a transition phase from quiet magnetotail current sheets to traditional magnetotail reconnection. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 127, 2021–029584 (2022).

Lu, S. et al. Electron-only reconnection as a transition from quiet current sheet to standard reconnection in earth’s magnetotail: Particle-in-cell simulation and application to mms data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 2022–098547 (2022).

Sharma Pyakurel, P. et al. Transition from ion-coupled to electron-only reconnection: Basic physics and implications for plasma turbulence. Phy0. Plasmas 26, (2019).

Phan, T. et al. Electron magnetic reconnection without ion coupling in earth’s turbulent magnetosheath. Nature 557, 202–206 (2018).

Russell, C. et al. The magnetospheric multiscale magnetometers. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 189–256 (2016).

Lindqvist, P.-A. et al. The spin-plane double probe electric field instrument for mms. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 137–165 (2016).

Ergun, R. et al. The axial double probe and fields signal processing for the mms mission. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 167–188 (2016).

Pollock, C. et al. Fast plasma investigation for magnetospheric multiscale. Space Sci. Rev. 199, 331–406 (2016).

Paschmann, G., Schwartz, S. Issi book on analysis methods for multi-spacecraft data. Cluster-II Workshop Multiscale/multipoint Plasma Measure. 449, 99 (2000).

Pyakurel, P.S. et al. On the Short-scale Spatial Variability of Electron Inflows in Electron-only Magnetic Reconnection in the Turbulent Magnetosheath Observed by MMS.

Fargette, N. et al. Statistical study of energy transport and conversion in electron diffusion regions at earth’s dayside magnetopause. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 129, 2024–032897 (2024).

Pyakurel, P. et al. Faster form of electron magnetic reconnection with a finite length x-line. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 155101 (2021).

Stawarz, J. E. et al. Properties of the turbulence associated with electron-only magnetic reconnection in earth’s magnetosheath. Astrophys. J. Lett. 877, 37 (2019).

Stawarz, J. et al. Turbulence-driven magnetic reconnection and the magnetic correlation length: Observations from magnetospheric multiscale in earth’s magnetosheath. Phys. Plasmas 29 (2022).

Yoon, Y. D., Moore, T. E., Wendel, D. E., Laishram, M. & Yun, G. S. Enablement or suppression of collisionless magnetic reconnection by the background plasma beta and guide field. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, 2024–112126 (2024).

Richard, L., Sorriso-Valvo, L., Yordanova, E., Graham, D. B. & Khotyaintsev, Y. V. Turbulence in magnetic reconnection jets from injection to sub-ion scales. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 105201 (2024).

Stawarz, J. et al. The interplay between collisionless magnetic reconnection and turbulence. Space Sci. Rev. 220, 90 (2024).

Matthaeus, W. H. et al. Pathways to dissipation in weakly collisional plasmas. Astrophys. J. 891, 101 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The primary funding for this work comes from the NASA MMS Project through the MMS Early Career Grant 80NSSC23K1662. P.S. Pyakurel was supported by NASA grants 80NSSC24K0559 and 80NSSC21K1481. J.P. Eastwood was supported by UKRI/STFC grant ST/W001071/1. This work would not be possible without the entirety of the MMS team and those that keep the instrumentation operational. We also acknowledge the impact of insightful conversations with Dr. Matthew Argall, Dr. Hasan Barbhuiya, Dr. Kevin Genestreti, Dr. Daniel Gershman, Dr. Tak Chu Li, Dr. Yi-Hsin Liu, Dr. William Mattheus, and Dr. Anthony Rogers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. Payne conceived of this study, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. M. Swisdak made significant contributions to the data interpretation, developing the methods, manuscript review and editing. J.P. Eastwood contributed to the data interpretation, analysis techniques, and manuscript review. J.F. Drake contributed to data interpretation, manuscript review, and supplemental material. P.S. Pyakurel contributed to data interpretation and manuscript review. J.R. Shuster contributed to data interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Payne, D.S., Swisdak, M., Eastwood, J.P. et al. In-situ observations of the magnetothermodynamic evolution of electron-only reconnection. Commun Phys 8, 36 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01948-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01948-y

This article is cited by

-

Smile-shaped electron gradient distributions observed during magnetic reconnection at Earth’s magnetopause

Communications Physics (2026)

-

An analytical model of “Electron-Only” magnetic reconnection rates

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Structure of the Electron Diffusion Region During Magnetic Reconnection

Space Science Reviews (2025)