Abstract

Quantum illumination is an entanglement-based target detection protocol that provides quantum advantages despite entanglement-breaking noise. However, the advantage of traditional quantum illumination protocols is limited to impractical scenarios with low transmitted power and simple target configurations. Here, we address these challenges by introducing a quantum illumination network that leverages a transmitter array and a single receiver antenna. Thanks to multiple transmitters, quantum advantage is achieved with a high total transmitted power. Furthermore, the network resolves complex target configurations involving multiple unknown transmissivity or phase parameters. Despite the interference of different returning signals at the single antenna and photon loss due to multiple-access channels, we develop two types of measurement designs: one based on parametric amplification and the other on correlation-to-displacement conversion. Finally, we generalize the parameter estimation scenario to a general hypothesis testing scenario, where the six-decibel quantum illumination advantage is achieved at a much greater total probing power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entanglement is a unique feature of quantum physics that brings benefits in information processing tasks1. Quantum illumination (QI) is an example where entanglement provides advantages in sensing tasks even when it is eventually destroyed by noise and loss during the sensing process2,3. The protocol sends out a signal to probe the target while storing the entangled idler for reference. Upon return of the noisy signal, a measurement is performed on both the return and the idler to determine the properties of the target.

QI came as a conceptual surprise, and much effort has been devoted towards making the quantum advantage practically relevant. To begin with, the original paper by Tan et al.3 showed quantum advantage with performance bounds and left the measurement design problem open. The initial design based on off-the-shelf components of the parametric amplifier provides sub-optimal quantum advantages4, which has been demonstrated in the optical domain5,6 and more recently in the microwave domain7. The optimal measurement has been subsequently proposed, with the sum-frequency generation process8 and via the correlation-to-displacement (CtoD) conversion9. With the development of the CtoD concept, simplified sub-optimal receivers based on heterodyne-homodyne is proposed to bring hope to practical microwave implementations10.

While the challenges in the measurement design have been relaxed, many other issues plague the practical relevance of QI, as summarized in refs. 11,12. One problem regards the fact that the original protocol only detects the presence and absence of a single target in a spatiotemporal bin, which is far away from real radar detection scenarios. Efforts in extending the applicability of QI have shown that advantage in ranging can be possible13,14, where the target can be at different locations along a single direction. However, the more important problem is that QI is considering an energy constraint that is far from realistic. As the brightness, defined as the photon flux per bandwidth, together with the ratio of signaling to background photon flux, needs to be less than unity to enable quantum advantage, the power of the transmitter is extremely low given the gigahertz bandwidth available at microwave frequency.

In this work, we propose a quantum illumination network to resolve the above low-power and single-target constraints of the original QI protocols. While a single transceiver can only detect a single target, in the QI network, multiple targets are simultaneously probed with a network of transmitters, and the return is detected by a single receiver antenna (see Fig. 1i). Due to multiple transmitters probing the same region, the total probing power can be large. As a result, for single target case, the advantage of QI network over the original single-transmitter QI protocol increases with the number of transmitters before saturation (see Fig. 1ii). The inevitable interference of different returning signals creates a challenge to the reception end. Here, we show that even with a single receiver, one is able to overcome the interference problem and achieve estimation precision advantages over the best classical strategies in the estimation of multiple phases or transmissivities. We also provide the measurement strategy to achieve quantum advantage based on parametric amplification4 or the CtoD conversion9,10.

i Quantum illumination network set-up. A transmitter array sends out multiple probes {Sj} to multiple targets (or different aspects of the same target) and then stores the corresponding entangled idlers {Ij} in quantum memory marked by M. The physical parameters that need to be identified correspond to the phase {θj} and reflectivity {ηj} imprinted on the return state. With a single antenna to receive the returning mode R, the experimenter can conduct multi-parameter quantum estimation and hypothesis testing under the influence of background noise (marked by B). ii Discrepancy between the estimation error of QI networks and conventional QI protocols. Here, we illustrate the root-mean-square error \({\epsilon }_{\overline{\theta }}\) in estimating an average of multiple phases with reflectivity ratio η ~ 0.5, the photon numbers NS = 0.5 and noise NB = 32. The plot is in log scale in both x and y axis. The variable m on the x-axis represents the number of transmitters, whereas \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) indicates the maximum number of target’s spatial modes that can be excited. The QI network demonstrates an error scaling of \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}({m}^{-1/2})\) for \(m\le {m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\), while conventional QI protocols are subject to a constant error.

Results and discussion

Quantum illumination network set-up

As shown in Fig. 1i, a quantum illumination network consists of an array of m transmitters, each emits a signal-idler pair {Sj, Ij} in a two-mode squeezed vacuum (TMSV) state15

where NS is the average photon number of Sj or Ij, \({a}_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{j}}({a}_{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{j}})\) and \({a}_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{j}}^{{{\dagger}} }({a}_{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{j}}^{{{\dagger}} })\) denote the annihilation and creation operators of the signal (idler) mode, respectively, and \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) is the vacuum state. Then, the experimenter stores the idlers, \({\{{a}_{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{j}}\}}_{j = 0}^{m-1}\), and sends the m signal modes, \({\{{a}_{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{j}}\}}_{j = 0}^{m-1}\), to the target. The experimental realization of the transmitter array can be potentially achieved by nano-antenna array16,17, in particular at the higher frequency end of radar detection.

At the common receiver, a single return mode is received, with interference between all return probes. The m transmitters are able to excite more spatial modes of the target, which may have non-zero overlap with the receiver spatial mode. As a simplified model, we assume the maximum number of spatial modes of the target (or multiple targets) being excited is \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) and different transmitters excite different spatial modes. Therefore, the return mode is given by the input-output relation

which forms a multiple-access channel18,19 from \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) senders and a single receiver. Note that we assume that the other \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}-1\) output modes other than \({\hat{a}}_{R}\) are not accessible to the receiver end. When there are \(m\le {m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) transmitters, the rest \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}-m\) transmitter modes are in vacuum. Here we define each virtual individual return \({a}_{{{{{\rm{R}}}}}_{j}}\) to model the loss and noise in the channel3,20,21,

where ηj ∈ [0, 1] is the reflectivity, θj ∈ [0, 2π) is the phase angle and the noise mode \({a}_{{{{{\rm{B}}}}}_{j}}\) has an average photon number NB/(1 − ηj) ≫ 1. Typically, the actual number of transmitters \(m\, \ll \, {m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\), therefore we focus on the case where \(m \, < \, {m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\). Here, we adopt the premise of reflectivity-independent noise NB as in the original approach3, which may arise from realistic scenarios such as low reflectivity3, bright thermal-noise bath3,22, Gaussian measurement23, and Gaussian additive noise channels15.

Note that our modeling is likewise straightforward, following the simplicity of the original QI model3. Our model is independent of the system’s frequency, hence enabling possible applications in the microwave, THz, and optical domains24. In addition, we have assumed full knowledge about the target to evaluate the quantum advantage, and therefore the maximal input mode number \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) is also known. In practice, \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) can be determined by electromagnetic simulations of targets and antenna or by experimental calibration. We want to emphasize that for a QI sensing system operating in the \(m \, < \, {m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) region, the knowledge of \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) can be merged into the knowledge of the full-path transmissivity—the QI network protocol does not rely on knowing \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) to achieve the performance, once the full-path transmissivity is known.

Here the targets are described by m phase shifts \({\{{\theta }_{j}\}}_{j = 0}^{m-1}\) and m transmissivities \({\{{\eta }_{j}\}}_{j = 0}^{m-1}\). These parameters can in general model different targets in the same region, or different parts of a single target. As a special case, the m sets of parameters can also be equal, representing a degenerate case where only a single target is being considered. Such a degenerate case represents a spatial multiplexing at the transmitter. Due to multiple transmitters, the total transmitted average photon number is increased to mNS; at the same time, as we assume a single receiver, the received photon number

increases linearly with m before saturation at large \(m={m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\) transmitters. As a result, the performance of the QI network increases with the number of transmitters m before saturation at \(m={m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\). As exemplified in Fig. 1ii, the root-mean-square error of estimating an average of multiple phases of QI network decreases as the number of transmitters increases. The QI network demonstrates an error scaling of \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}({m}^{-1/2})\) for \(m\le {m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\), while conventional QI protocols are subject to a constant error. The performance evaluation utilizes Eq. (13) in the degenerate case, as we detail in section ‘Multiple-phase sensing’.

The final measurement is applied on the return mode R jointly with m idler modes, \({\{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{j}\}}_{j = 0}^{m-1}\). The resulting (m + 1)-mode is in a zero-mean Gaussian state with quadrature covariance matrix (see basic definitions with natural units ℏ = 2 in ref. 15):

where \({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }:= {N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}+{\sum }_{j = 0}^{m-1}{\eta }_{j}{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}/m\) refers to the adjusted background photon number, \({{\mathbb{I}}}_{\ell }\) is the identity matrix of dimension ℓ, \(\left\{{S}_{j}:= 2\,\sqrt{{\eta }_{j}{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}({N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}+1)/{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}}\,{\mathbb{Z}}{{\mathbb{R}}}_{j}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\right\}\) are 2 × 2 matrices defined by \({{\mathbb{R}}}_{j}=\cos {\theta }_{j}{{\mathbb{I}}}_{2}-i\sin {\theta }_{j}{\mathbb{Y}}\) with \({\mathbb{Z}}\) and \({\mathbb{Y}}\) being the Pauli matrices.

To achieve the desired high precision in sensing, one sends out ν mode pairs, \({\{{{{{\rm{S}}}}}_{j}^{(n)},{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{j}^{(n)}\}}_{n = 0}^{\nu -1}\), at each transmitter 0 ≤ j ≤ m − 1 and therefore receive modes R(n)’s. Such a repetition is typically realized by broadband probes, where ν = BT is the time-bandwidth product for bandwith B and pulse duration T. We can also introduce the virtual received modes \({R}_{j}^{(n)}\), similar to the single pair case in Eq. (3). The multiple mode pairs can come from the large time-bandwidth product of the spontaneous parametric down-conversion source that generates the TMSVs.

Finally, the performance of sensing is characterized by the square root of the weighted mean-square error (rWMSE)

where ρϕ refers to ν copies of output states from the QI process, the parameters of interest are \({{{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}}={({\theta }_{0},\cdots ,{\theta }_{m-1})}^{T}\) for multiple-phase sensing or \({{{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}}={({\eta }_{0},\cdots ,{\eta }_{m-1})}^{T}\) for reflectivity sensing, {Ma} refer to the positive operator-valued measure (POVM) associated to ν-rounds of measurement, the estimator \(\{{\hat{\phi }}_{j}(a)\}\) are mapping from the measurement data a (which could be multidimensional) to the parameters.

Given the classical and quantum Cramér-Rao theorem25,26,27,28,29,30,31, the rWMSE of a measurement \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\) can be bounded as follows:

where \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}\) is the classical Fisher information matrix based on the measurement results \(p(a)={{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{\rho }_{{{{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}}}{M}_{a}]\): \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}},{\phi }_{j},{\phi }_{k}}={\sum }_{a}p(a)(\partial p(a)/\partial {\phi }_{j})(\partial p(a)/\partial {\phi }_{k}),\) and \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) is the quantum Fisher information matrix based on the output state ρϕ: \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{{\phi }_{j},{\phi }_{k}}={{{\rm{Tr}}}}[({L}_{i}{L}_{j}+{L}_{j}{L}_{i}){\rho }_{{{{\boldsymbol{\phi }}}}}]/2\) with Li being the symmetric logarithmic derivative (SLD) defined by ∂ρϕ/∂ϕi = (ρϕLi + Liρϕ)/2.

The interference among multiple returning modes, as shown in Eq. (2), will have distinct consequences in classical and quantum scenarios. For instance, in the trivial lossless and noiseless limit of ηj = 1, NB = 0, θj = 0, classical illumination (CI) with coherent probe states11,32 will lead to the output coherent state with an amplitude \(m\sqrt{{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}/{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}}\). In this scenario, the receiving photon number will have a scaling \({\left\langle {a}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} }{a}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{ci}}}}} \sim {{{\mathcal{O}}}}\left({m}^{2}/{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}\right)\). The photons of m returning modes are regained in a single mode. In contrast, the receiving photon number in the QI network, given by Eq. (4), has a scaling \({\left\langle {a}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} }{a}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\right\rangle }_{{{{\rm{ci}}}}} \sim {{{\mathcal{O}}}}(m/{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}})\) with a much higher level of photon loss. Nevertheless, we will show that the QI network can still achieve quantum advantages in multi-parameter estimation and hypothesis testing.

Application scenarios

In contrast to previous QI protocols2,3,11,12, the present approach exhibits significantly enhanced power of probing as a result of an m tramsmitter system, hence increasing its practical applicability. Here we provide modeling for different sensing scenarios in terms of the parameter choices. We will obtain thermal noise from Bose-Einstein distribution \({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\propto 1/[\exp (h{f}_{p}/{k}_{B}T)-1]\), where fp is the center frequency, T is the effective temperature of the system, h is the Planck constant and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The total power of the QI network will be P ≔ mNSB h fp, where B refers to the bandwidth.

One parameter region of interest is the traditional microwave radar being considered in quantum illumination3,11,14. For instance, most radars operate within a frequency range of 1–20 GHz33. If we consider a radar detection scenario with a frequency fp = 2GHz and sky temperature T = 10K (assuming probing the vertical direction), we have NB ~ 104. Another example is the W-band radar, typically with fp = 100 GHz, bandwidth B = 10 GHz and sky temperature T = 150 K (assuming probing closer to horizontal direction), leading to thermal noise NB ~ 32. This type of radar has a more compact size for integration34. Another parameter region of interest is the THz-wave radar35,36. At THz frequency (wavelength ~ 100 um), with the implementation of nano-antenna array16,17, a large number of transmitters can be engineered, greatly enhancing the total power output over the single transmitter QI system11. In the quantum realm, an array of quantum THz transmitters can be implemented on chip37. Alternatively, they can be potentially realized via multiple frequency modes37,38. We consider NB = 0.6 for 300 K as THz radar is in short range. In this case, the QI network has the potential to exhibit advantages robust to the presence of various forms of sky noise36,39.

On this ground, the QI networks can be applied to multi-parameter estimation and hypothesis testing, which feature circumstances when a macroscopic target cannot be effectively characterized by a single parameter due to its complexity. Moreover, the QI network may be taken into account when assessing the temporal evolution of the target. In the present work, the parameters of interest are phases and reflectivities imprinted on the returning state, each associated with the range or presence of the target. Finally, via the design of measurement protocols, these physical parameters and their statistical properties can be determined.

Classical benchmark

As a benchmark for quantum advantage, we examine the minimal estimation error achievable by classical strategies, under the constraint that probes are prepared via a statistical mixture of coherent states11,32 with the same total signal power as the quantum case. We shall use the rWMSE to characterize the performance of estimation. In the degenerate case where all the phases have the same value, or where only the global information in the form of weighted average phase \({\overline{\theta }}^{{\prime} }={\sum }_{j}\scriptstyle\sqrt{{\eta }_{j}/{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}}\,{\theta }_{j}\) is unknown, we also adopt the root of the mean-square error (RMSE) directly to characterize the performance.

Based on this premise and the convexity of quantum Fisher information matrix (QFIM)31,40,41, we can obtain the following theorem.

Theorem 1

(Asymptotic benchmark of phase sensing (ν ≫ m)) In the classical illumination network, where the input is restricted to random mixtures of coherent states, its rWMSE of estimating m independent phases satisfies the asymptotic bound

A detailed proof of Theorem 1 is illustrated in Supplementary Note 1. Note that it is impossible to achieve the equality of Ineq. (8) by pure coherent states when the number of experiments is limited, particularly with the condition ν < ⌈m/2⌉. This is caused by the fact that only mixed input states can output states with full-rank QFIMs. However, mixed input states such as amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) source are not optimal due to the convexity of QFIM (see detailed proof in Supplementary Note 1). Nevertheless, one can resolve this issue by conducting more than m/2 experiments, by which a full-rank QFIM can be achieved by a summation of non-full-rank QFIMs. We can prove that the rWMSE \({\epsilon }_{{{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}},{{{\rm{c}}}}}=\sqrt{{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}(2{N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}+1){\sum }_{j}{\eta }_{j}^{-1}/(4m\nu {N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}})}\) is achievable with pure input states for the favorable condition ν = ℓm/2, for any positive integer ℓ and any positive even integer m. Specifically, the experimenter estimates two parameters θj and θk in each experiment, with an effective concentration of energy15,42 and fine-tuned phases. Therefore, a diagonal QFIM \({F}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{\{j,k\}}=2m{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}/[{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}(2{N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}+1)]{{{\bf{diag}}}}({\eta }_{j},{\eta }_{k})\) can be achieved29,43. By repeating this experiment yet with different pairs of parameters, the experimenter is able to obtain the minimum rWMSE.

Measurement design for quantum illumination

We propose two designs of measurement to achieve the quantum advantage of a QI network.

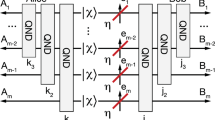

Parametric amplifier network

The quantum illumination network allows the establishment of a multiple-access channel18,19, where the follow-up measurement design of the (m + 1) modes can resort to the protocols based on parametric-amplifiers (PAs). For the sake of simplicity, we will examine two PA-based protocols: the parallel and serial phase-conjugate receiver (pPCR/ sPCR), where PA is adopted to perform a phase conjugation on the return. Both receivers provide a 3 dB quantum advantage in the error-probability exponent when it comes to discriminating between target’s presence or absence4.

Specifically, the pPCR consists of the following steps (see schematic in Fig. 2a and detailed derivation in Supplementary Note 2):

-

(O1) Conduct a joint PA operation on the return and vacuum to obtain the phase-conjugated return.

-

(O2) Distribute the phase conjugated return from the PA via a multi-port beamsplitter.

-

(O3) Implement balanced beamsplitters that produce interference pairwisely on each portion of the phase conjugated return output from the multi-port beamsplitter and a set of idlers.

-

(O4) Perform photodetection on the interfered modes and estimate physical parameters from the difference between total photon numbers from the two output ports of each balanced beamsplitter.

a parallel phase-conjugate receiver (pPCR), (b) serial phase-conjugate receiver (sPCR). Here, “R” and “I” denote the returning and ancilla modes, respectively. Parametric amplifiers are labeled as “PA,” while vacuum inputs are indicated as “vac.” Single-mode quantum measurement process is represented by “PD”.

In addition to applying the pPCR protocol, the experimenter can implement multiple PA operations in a sequence. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the sPCR consists of the following steps (see details in Supplementary Note 2):

-

(O1′) Same as O1.

-

(O2′) Consume one of the outputs from the PA operation to interact with one of the stored idler. Provide the other output and an additional vacuum to a subsequent PA. Repeat the aforementioned step for m times in total.

-

(O3′) Implement balanced beamsplitter operations to pair-wisely generate interference between the PA outputs and the idlers.

-

(O4′) Perform photodetection on the interfered modes and estimate the parameters of interest via measuring the photon current difference at each balanced beamsplitter.

Note that photon statistics from PA receivers are phase sensitive. To achieve the best performance, either prior information about the phases or adaptive strategies are needed to choose the right phase angles. In section ‘Multiple-phase sensing’, we shall show that the PA protocols are adequate for achieving quantum advantages over any classical strategies.

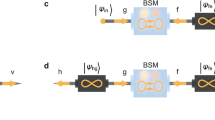

Correlation-to-displacement conversion

In addition to the PA receiver network, one can consider the CtoD conversion protocol (see details in Supplementary Note 2), which involves the following steps:

-

(Q1) Upon receiving the return, perform heterodyne measurement described by the positive operator-valued measure (POVM) \(\{\left| \chi \right\rangle \left\langle \chi \right| /\pi \}\) on the returning mode, where \(\left| \chi \right\rangle\) refers to the coherent state with complex amplitude χ. The measurement outcome can be described by the vector x = 2[Re(χ), Im(χ)]T, which satisfies the distribution:

$$p({{{\boldsymbol{x}}}})={[4({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }+1)\pi ]}^{-1}\exp \left[-{[4({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }+1)]}^{-1}| {{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}{| }^{2}\right].$$(9)Conditioned on the measurement result x, the remaining idlers will have the mean and covariance matrix

$$\left\{\begin{array}{rcl}{{{\xi }}}_{\chi }&=&\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!{[2({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }+1)]}^{-1}{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}({{\mathbb{I}}}_{m}\otimes {{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}),\\ {{{{\boldsymbol{V}}}}}_{\chi }&=&(2{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}+1){{\mathbb{I}}}_{2m}-{[2({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{\prime}+1)]}^{-1}{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}{{{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}},\end{array}\right.$$(10)where \({{{\boldsymbol{S}}}}={\left({S}_{0}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}},\cdots ,{S}_{m-1}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\right)}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) is a 2m × 2 matrix. Considering the multi-mode nature of the return, we denote the heterodyne measurement result as χn for each n = 0, ⋯ , ν − 1-th mode, where ν is the total number of modes.

-

(Q2) Implement identical ν-mode passive operations \({V}_{\{| {{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{n}| \}}\) on each of the idler (containing ν modes) to align the displacements \(\{{{{{\boldsymbol{\xi }}}}}_{{\chi }_{n}}\}\) and to concentrate all displacements of mν modes into a single m-mode state (see details in Supplementary Note 4.2.).

-

(Q3) Perform homodyne measurement \(\{\left| q\right\rangle \left\langle q\right| \}\) on each of the m concentrated idlers, where \(\left\vert q\right\rangle\) refers to the eigenstate of the position operator \(\hat{q}:= a+{a}^{{{\dagger}} }\).

The diagram of the CtoD protocol is illustrated in Fig. 3. The protocol is based on the CtoD conversion9, and is a direct generalization of the heterodyne-homodyne version of CtoD receiver10. In the following parts of this paper, we will evaluate the quantum advantages of the PA and CtoD protocols in the context of multiple-phase sensing and pattern classification.

Multiple-phase sensing

With the receivers in hand, now we examine the performance of the QI network in multiple-phase sensing. We begin with the PA receiver in section ‘Parametric amplifier network’. Denote the PA gain of the pPCR as g; For sPCR, we also choose uniform PA gains and denote it as g, while the actual value of g is optimized separately in sPCR and pPCR. The following theorem is obtained by applying the central limit theorem to simplify the measurement probability of photodetection into a Gaussian function and the Gaussian nature of the probe states (see Supplementary Note 3).

Theorem 2

(PA network for multiple phase sensing) In the QI network, the PA protocol can achieve the Fisher information matrix (ν ≫ 1):

where the coefficients are \({{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}_{j}={f}_{j}(g-1)({N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }+1)(2{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}+1)+{N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\) and \({{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}}_{j}=\sqrt{2{f}_{j}(g-1){N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}({N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}+1){\eta }_{j}/{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}}\cos {\theta }_{j}\), fj = 1/m for pPCR and fj = g j for sPCR.

The corresponding rWMSE \({\epsilon }_{{{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}}=\sqrt{{{{\rm{Tr}}}}\left[{({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}^{{{{\rm{pa}}}}})}^{-1}\right]/m}\) to the leading order can be obtained as

A detailed proof of Theorem 2 can be found in Supplementary Note 3. In the above result, the PA gain is not specified. Indeed, one can optimize the sensing performance by tuning the values of gain. We observe that the ideal amplification rate g varies between pPCR and sPCR. In pPCR, the best value of g is close to two, while in sPCR, it is close to one.

For the CtoD measurement approach, exact expression of the Fisher information matrix is complicated. On the other hand, we can obtain the rWMSE expression asymptotically.

Theorem 3

(CtoD conversion for multiple phase sensing) In the QI network for multiple phase sensing, the CtoD protocol achieves the rWMSE

A concrete proof of Theorem 3 is shown in Supplementary Note 4. To thoroughly understand the trend of the precise rWMSE obtained by the QI network in terms of the signal and noise brightness, we consider the two application scenarios introduced in section ‘Application scenarios’ where the noise NB = 32 for a W-band radar and NB = 0.6 for a THZ radar. Then we tune the signal brightness NS and evaluate the phase sensing rWMSE error ϵθ for pPCR, sPCR and CtoD in QI network. In Fig. 4, we plot the ratio of the quantum rWMSE (Eqs. (12) and (13)) over the classical rWMSE (Eq. (8)) versus the ratio NS/NB. It is shown that, as the input signal brightness grows, the quantum advantage tends to vanish as expected. On the other hand, given the low-brightness limit (NS ≪ 1), the ratio between the rWMSEs will converge to a constant factor9,44—a factor of two advantage in terms of the variance.

Here we precisely evaluate three cases: (i) microwave Radar with NB = 104; (ii) W-band Radar with NB = 32; (iii) THz Radar with NB = 0.6, with m = 50 transmitters with ν = 5000 rounds of experiment. For PA receivers, the amplification rate is g ~ 2m for parallel phase-conjugate receiver (pPCR) and g ~ 2 for serial phase-conjugate receiver (sPCR). Its error refers to the minimum error of all phase values. For correlation-to-displacement (CtoD) protocol, the error is calculated for θj → 0 and ηj ~ 0.5.

Theorems 2 and 3 extend upon earlier approaches of quantum illumination2,3,11,12,44 by introducing an efficient measurement design for the QI network in the typical parameter region of NS < NB. In particular, the errors shown in Eqs. (11) and (13) converge to the same value in various frequency regions (see Fig. 4). Further, Eq. (13) achieves the quantum limit for single-parameter estimation9,45, indicating that the quantum strategy has a double value of Fisher information, thus being tight in the scenario when only one phase is unknown. In the multi-phase estimation with microwave and W-band radars, the ratio between rWMSEs of quantum and classical strategies converges to a value \(\sqrt{1/2}\) in the weak signal limit (Fig. 4). Moreover, it is shown in Supplementary Note 4 that the second and third steps of the CtoD method are optimal, conditionally on the choice of heterodyne measurement in its first step.

Note that Eqs. (12) and (13) approach a scaling of \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}(\sqrt{{m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}/\nu })\). This is caused by the fact that information about each phase is vanishing as its corresponding quantum amplitude decreases. To resolve this issue, we can alternate the parameter of interest to the average phase \(\overline{\theta }\), which induces an error of scaling \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}(\sqrt{1/(m\nu )})\). Thus, it is possible to achieve a finite error with an arbitrarily high number of transmitters, even when the number of transmitters m far exceeds the number of experiments ν.

In addition to estimating the phase of each mode, the QI network can also be used to estimate the reflectivity (assuming knowledge of the phases). Given that the PA and CtoD have the same leading order of rWMSE, by changing parameters of interest, we have the following Corollary:

Corollary 1

(Reflectivity sensing) In QI reflectivity sensing for {ηj}, the achievable rWMSE is:

Corollary 1 can be quickly verified by substituting parameters of interest by reflectivity ratios when computing QFIMs (see Supplementary Note 4).

Remark 1: ((m + 1)-mode vs single-mode output states) The QI network produces a Gaussian state with (m + 1) modes, using m copies of TMSV input states (see Eq. (5)). The zero-mean state’s properties are defined by its 2m-by-2m covariance matrix, which in turn allow for the estimation of m independent phases. In contrast, classical correlations can only be produced by classical mixtures of states, which does not help in achieving the bound in Eq. (8). In addition, if the input state is pure, the corresponding output state will be a single-mode displaced thermal state, in which the information of m independent phases can only be determined by its displacement, with only two independent degree of freedom. The limited degree of freedom cannot allow the independent extraction of m parameters. In Supplementary Note 1, we show that the rWMSE for arbitrary classical estimation protocol is subjected to \({\epsilon }_{{{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}},{{{\rm{c}}}}}=\sqrt{2\nu {E}_{{{{\rm{1-c}}}}}/m+\left(1-2\nu /m\right){\pi }^{2}/3}\) in the case ν < m/2, where E1-c refers to the minimum mean-square-error achievable via a single-shot measurement of the output state from classical illumination networks.

Remark 2: (Practicality) The PA receiver network and the CtoD receiver network possess different advantages and face specific challenges in experimental applications, respectively. Both receivers use on Gaussian measurements, which is more accessible than non-Gaussian measurement, such as that with photon number resolving detectors. From numerical calculation of Fig. 4, the CtoD receiver consistently outperforms all other PA receivers in terms of estimation error. In addition, the CtoD receiver as well as the pPCR receiver (shown in Fig. 2) allows for simultaneous access to all idlers in each experiment trial, while the sPCR receiver need access to each idler at a designated time. A practical concern might be that the CtoD receiver requires a multi-port beamsplitter, when concentrating signals from different experiments, in which the rotation parameters are based on the heterodyne measurement results. This concern can be alleviated through effectively “implementing” the beamsplitter using classical data-processing and feed-forward to establish an equivalent joint measurement10. A possible concern in the practicality of pPCR is that it requires a PA with high amplification rate ~ 2 m (see Fig. 5). Intuitively, this is due to the presence of a single PA in the pPCR scheme, but the effective amplification ratio in the sPCR technique may accumulate via a successive application of PAs. At last, idler storage might be a challenge to the implementation of QI networks, regardless of the detection schemes. At optical frequencies, one may be able to rely on fiber loops which has reasonably low loss at the target distances of interest; At microwave frequencies, quantum memory storage and operations can be possible with superconducting cavities. Loss and noise in the idler storage will be detrimental to the quantum advantage, similar to the original QI protocol. In this regard, the CtoD receiver has an advantage of not requiring the direction interaction between the noisy return acquired by the antenna at room temperature and the idler storing in the quantum memory.

Here, we numerically simulate the microwave Radar with photon numbers NB = 32, NS = 0.5, and parameters ηj ~ 0.5 and θj ~ 0. The maximal modes is \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}=120\). Number of transmitters is m = 50. Experiments rounds is ν = 2 ⋅ 104. The inset illustrates a zoomed figure of the estimation error associated with the serial phase-conjugate receiver (sPCR) method with low amplification ratios. It can be observed that the parallel phase-conjugate receiver (pPCR) protocol achieves the same error as the sPCR protocol with much higher value of g.

Pattern classification

Besides multi-parameter estimation, hypothesis testing between different targets is one of the first applications of QI, particularly in determining the presence or absence of a target2,3. In the setting with a QI network, the hypotheses can be described by the change of possible values of reflectivity: (I) η = η(0), and (II) η = η(1), where \({{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}}}^{(h)}={({\eta }_{0}^{(h)},\cdots ,{\eta }_{m-1}^{(h)})}^{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\) for h = 0, 1. Given multiple copies of the (m + 1)-mode signal-idler state, the CtoD scheme will generate conditional states at j-th mode, whose displacement depends on the reflectivity ηj and the heterodyne measurement results {xn}. By conducting passive operations on the ν copies of each mode, it is possible to produce ν identical m-mode states only based on the knowledge of the heterodyne measurement results (see detailed proof in Supplementary Note 4.2 and Supplementary Note 5): \({\rho }_{{{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}}}^{(h)},{{{\rm{hp}}}},\{{{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}_{n}\}}={\rho }_{{{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}}}^{(h)},\overline{{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}}^{\otimes \nu }.\) Therefore, if we quantify the performance of pattern classification by the error probability: \({p}_{{{{\rm{hp}}}}}({\rho }_{{{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}}}^{(0)},{{{\rm{hp}}}}},{\rho }_{{{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}}}^{(1)},{{{\rm{hp}}}}})=1-{\max }_{\{{\hat{\Pi }}_{h}\}}{{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{\hat{\Pi }}_{h,\overline{{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}}}{\rho }_{{{{{\boldsymbol{\eta }}}}}^{(h)},{{{\rm{hp}}}}}]/2\) with \(\{{\hat{\Pi }}_{h}\}\) being an arbitrary (mν)-mode measurement, the following two theorems are given:

Theorem 4

(Benchmark for pattern classification) When the reflectivities are unknown or time-varying, which prevents the concentration of power in some probe modes, the minimal error probability for multiple-pattern classification is:

A concrete proof of Theorem 4 can be found in Supplementary Note 5. It is shown that the benchmark can be achieved by preparing a statistic mixture of coherent states as input11,15.

On the other hand, we have the following theorem if entangled probes are allowed:

Theorem 5

(Quantum limit for pattern classification) The QI network that satisfies the conditions that \({N}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}={{{\mathcal{O}}}}(1) \, \ll \, {N}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) can achieve the error probability:

A concrete proof of Theorem 5 can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

Remark 3: (Quantum advantage vs disadvantage) We note that the CI and QI error probabilities in Eq. (15) and Eq. (16) have different dependence on the reflectivities—the classical case has amplitude summed and then square while the quantum case has amplitude squared and then summed. Such a difference comes from the interference in Eq. (2): in the classical case, Eq. (2) will directly combine coherent state in amplitudes; while in the quantum case the multiple idlers are obtained in weakly thermal coherent states and they will only be combined in energy even if one further applies beamsplitter to concentrate all coherent states. Similar scaling difference can also be identified for single-parameter estimation (see Supplementary Note 6). Note that this phenomenon does not appear in multi-parameter estimation. In simple terms, the reason is that Eq. (7) excludes the off-diagonal elements of the inverse of Fisher information matrices, resulting in the rWMSE being unaffected by how parameters are collectively encoded in states.

Finally, Eq. (16) achieves the optimal error probability for hypothesis testing with a single parameter9. The error exponent of the QI network has an overhead as follows:

where in the second approximation we have considered the NB ≫ 1 and NS ≪ 1 limit. When the number of transmitters m = 1, the above results recovers the general hypothesis testing result in ref. 9 and provides a factor of \(\ln (2\,{p}_{{{{\rm{qi}}}}})/\ln (2\,{p}_{{{{\rm{ci}}}}})\simeq 4\) advantage in error exponent (6 dB). In typical cases where the differences \(\left\{\sqrt{{\eta }_{j}^{(0)}}-\sqrt{{\eta }_{j}^{(1)}}\right\}\) has values ± c with equal probabilities (representing absent or present), there will be an exact 6 dB advantage in error exponent as the denominator of Eq. (18) will be proportional to m46.

Discussion: potential advantage in optics

Conventionally, QI protocols exhibit advantage in noisy scenarios where the signaling photon number is much smaller than that from background noise2,3,11,12. However, the background noise typically vanishes in most optical settings. On this account, it is usually not straightforward to figure out quantum advantages. In the setting of illumination networks, there exists situations where the measurement round is much smaller than the number of transmitters. Examples of such scenarios include evading targets or targets whose properties change over time. As addressed in preceding sections, the signal-idler pairs of classical illumination networks can only convey a maximum of two independent parameters in their displacements, leaving other parameters to be determined randomly. On the other hand, the returning state QI networks combined with the idlers is able to carry information of multiple independent parameters. In this context, the QI network may provide possibilities for achieving quantum advantage in optical settings. Here, we provide upper and lower bounds for the classical benchmark in non-asymptotic phase estimation as a first step in this study:

Theorem 6

(Non-asymptotic benchmark for phase sensing (ν < m/2⌉)) The classical benchmark for multiple phase sensing with the uniform distribution has the following non-asymptotic bounds:

where EBaye(ρ(θ), θj) is a Bayesian variance43,47,48,49, {Ec,homo,k} is the mean-square-error achievable by preparing coherent state probes and performing homodyne measurement for \(J=\lfloor 2\nu /{\nu }^{{\prime} }\rfloor (/{J}^{{\prime} }=\lfloor \nu /{\nu }^{{\prime} }\rfloor )\) phases with \({\nu }^{{\prime} }=1,2,\cdots \,,2\nu /J(\nu /{J}^{{\prime} })\).

A concrete demonstration of Theorem 6 is shown in Supplementary Note 1.4. In simple terms, when the value of ν is much less than m, the rWMSE converges to a constant. This phenomenon is caused by the limitation that coherent state probes can only carry information for two independent phases. Additionally, a statistical mixture of coherent states will induce a biased measurement results at each possibility, thus leaving other parameters at random guess with a RMSE \(\sim \sqrt{{\pi }^{2}/3}\).

Here, we numerically evaluated the non-asymptotic bounds of the classical benchmark (Eqs. (19) and (20)) in an optical setting with ν < m. As shown in Fig. 6, the benchmark bounds are close to the rWMSE from random guess and decrease slowly with experiment round ν. Due to the difficulty of computing non-asymptotic bound of rWMSE with correlated measurement data (see section ‘Multiple-phase sensing’), we leave the explicit proof of the quantum advantage open for future approaches. In addition, the optimal sensing strategy of estimating multiple phases might involve global measurement49. The optimal design of a global estimation strategy for non-asymptotic scenarios is a further topic for future research.

Here we numerically evaluate the square root of the weighted mean-square error (rWMSE) in the optical scenario with signaling photon number NS = 200, background photon number NB = 0.01, m = 1600 effective transmitters, \({m}_{{{{\rm{re}}}}}=2000\) transmitter modes for saturation, and transmissivity ratios ηj ~ 0.7. The classical benchmarks ϵθ,c is evaluated by assuming that the whole energy mNS is concentrated in a single probe in each experiment trail. Given a fixed experiments round number ν, we optimize the phase number \(J,{J}^{{\prime} }=\nu /{\nu }^{{\prime} }\) to be estimated while leaving the other phases at random guess. The upper bound of benchmark is evaluated by \({\nu }^{{\prime} }\)-shot homodyne measurement with MSE \({E}_{{{{\rm{c}}}},{{{\rm{homo}}}},{{{\rm{k}}}}}\approx 6.31/{\nu }^{{\prime} }\). The lower bound of benchmark is evaluated by the Bayesian bound with \({E}_{{{{\rm{Baye}}}}}=3.53/{\nu }^{{\prime} }\). The explicit calculation of the cases where two classical probes are used, i.e. \(J=2\nu /{\nu }^{{\prime} }\) is an open problem as it induces negative Beyasian bound in this case.

Conclusions

We investigated the metrological usefulness and measurement design in the quantum illumination network, where a transmitter array and a single receiver antenna are used. We proved an advantage in multiple-parameter sensing and hypothesis testing. Specifically, we analytically computed the minimum rWMSE achievable by both the QI network and arbitrary classical strategies for the typical scenarios where the probe photon number is smaller than that of the background noise. We show that for a significant range of probe photon numbers, the rWMSE achieved by either a PA or CtoD measurement protocol has a favorable value. In contrast, all classical strategies are subjected to a larger error when the signal is comparatively smaller than the noise. Further, we extend the discussion to pattern classification of the reflectivity pattern. We show that when each transmitter is constrained to a fixed number of photons, the QI network can achieve the six-decibel advantage as in the single-parameter hypothesis testing case. As explored in ref. 14, we expect the six-decibel advantage can lead to large resolution advantage in the threshold region of parameter estimation.

Finally, we point out a few future directions. Our work demonstrates the classical benchmark and achievable precision in phase estimation with QI networks. However, the rWMSE from the overall output state (described in Eq. (5)) is unknown. Future research could be determining whether the current advantage from PA and CtoD protocols are optimal or whether improvement in these measurement protocols within the framework of QI networks is possible. Such QFI evaluation for general multi-parameter estimation case may encounter the issue of measurement incompatibility50. In addition, we have only considered a single receiver antenna in the QI network. An array of antenna such as that in the multiple-input and multiple-output (MIMO) channel scenarios can enable further enhancement of signal-to-noise ratios. While we considered multi-parameter estimation, it is an open question how such advantages can be generalized to more general measurement settings, such as tomography and learning. Future research may also be expanded to include moving targets, where multiple parameters at various time intervals are estimated.

Methods

In Supplementary Note 1, we derived analytical expressions for the classical benchmarks relevant to our study. Specifically, we modeled classical quantum illumination processes as those employing classically correlated coherent states as probes. Leveraging the convexity property of the quantum Fisher information matrix (QFIM), we established an upper bound on the QFIM for such classical strategies. Using the quantum Cramér-Rao bound31, we established a lower bound of the rWMSE for arbitrary classical protocols. We then illustrated a specific classical protocol and demonstrated that its performance establishes the upper bound for the classical benchmark under this framework. Furthermore, we extended the analysis to non-asymptotic estimation scenarios, where we derived classical benchmarks based on the Bayesian bound43,47,48,49 with a uniform prior distribution. Finally, we provided an upper bound on the non-asymptotic classical benchmark achievable through pure probes and homodyne measurements. We numerically illustrated the non-asymptotic benchmarks in Fig. 6.

As a preparation step toward calculating the achievable estimation error in phase sensing and hypothesis testing, Supplementary Note 2 provides explicit expressions for the displacement vector and covariance matrix at each stage of the quantum illumination process, from the premise that the probe states are Gaussian and the process can be modeled as a Gaussian quantum channel. Furthermore, we derived the output quantum state and the corresponding multivariate classical outcomes based on a practical implementation of a measurement network—specifically, the PCR network—in both serial and parallel configurations. Additionally, we detailed the evolution of the covariance matrix within the context of the CtoD strategy.

The optimal design of the PA protocol and the CtoD strategy is demonstrated in Supplementary Notes 3 and 4, respectively. In Supplementary Note 3, We computed the rWMSE achievable by both the sPCR and pPCR networks, derived from the multivariate Gaussian distribution of the homodyne measurement results. In Supplementary Note 4, we computed the QFIM of the output state within the CtoD strategy utilizing its Gaussian feature31. Furthermore, we demonstrated how to design a CtoD experiment with heterodyne-homodyne measurements that achieves a classical FIM with a dominant component matching that of the QFIM.

In Supplementary Note 5, we proved the quantum advantage of quantum illumination networks in hypothesis testing for distinguishing between different reflectivity patterns. Particularly, we computed the quantum Chernoff bound of the Gaussian output state51 for the CtoD protocol and established the benchmark for all classical strategies. Finally, we discussed average phase sensing in Supplementary Note 6.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The theoretical results of the manuscript are reproducible from the analytical formulas and derivations presented therein. Additional code is available from the first author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Z. et al. Entanglement-based quantum information technology: a tutorial. Adv. Opt. Photonics 16, 60 (2024).

Lloyd, S. Enhanced sensitivity of photodetection via quantum illumination. Science 321, 1463 (2008).

Tan, S.-H. et al. Quantum illumination with gaussian states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 253601 (2008).

Guha, S. & Erkmen, B. I. Gaussian-state quantum-illumination receivers for target detection. Phys. Rev. A 80, 052310 (2009).

Zhang, Z., Mouradian, S., Wong, F. N. & Shapiro, J. H. Entanglement-enhanced sensing in a lossy and noisy environment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 110506 (2015).

Hao, S. et al. Demonstration of entanglement-enhanced covert sensing. Phys. Rew. Lett. 129, 010501 (2022).

Assouly, R., Dassonneville, R., Peronnin, T., Bienfait, A. & Huard, B. Quantum advantage in microwave quantum radar. Nat. Phys. 19, 1418 (2023).

Zhuang, Q., Zhang, Z. & Shapiro, J. H. Optimum mixed-state discrimination for noisy entanglement-enhanced sensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 040801 (2017).

Shi, H., Zhang, B., Shapiro, J. H., Zhang, Z. & Zhuang, Q. Optimal entanglement-assisted electromagnetic sensing and communication in the presence of noise. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 034004 (2024).

Reichert, M., Zhuang, Q., Shapiro, J. H. & Di Candia, R. Quantum illumination with a hetero-homodyne receiver and sequential detection. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 014030 (2023).

Shapiro, J. H. The quantum illumination story. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 35, 8 (2020).

Karsa, A., Fletcher, A., Spedalieri, G. & Pirandola, S. Quantum illumination and quantum radar: a brief overview. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.06049 (2023).

Zhuang, Q. Quantum ranging with Gaussian entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 240501 (2021).

Zhuang, Q. & Shapiro, J. H. Ultimate accuracy limit of quantum pulse-compression ranging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 010501 (2022).

Weedbrook, C. et al. Gaussian quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 621 (2012).

Llatser, I. et al. Graphene-based nano-patch antenna for terahertz radiation. Photonics Nanostruc. Fundam. Appl. 10, 353 (2012).

Kavitha, S., Sairam, K. & Singh, A. Graphene plasmonic nano-antenna for terahertz communication. SN Appl. Sci. 4, 114 (2022).

Winter, A. The capacity of the quantum multiple-access channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 47, 3059 (2001).

Shi, H., Hsieh, M.-H., Guha, S., Zhang, Z. & Zhuang, Q. Entanglement-assisted capacity regions and protocol designs for quantum multiple-access channels. npj Quant. Inform. 7, 74 (2021).

Yuen, H. P. Two-photon coherent states of the radiation field. Phys. Rev. A 13, 2226 (1976).

Yuen, H. P. & Nair, R. Classicalization of nonclassical quantum states in loss and noise: Some no-go theorems. Phys. Rev. A 80, 023816 (2009).

Wilde, M. M., Tomamichel, M., Lloyd, S. & Berta, M. Gaussian hypothesis testing and quantum illumination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 120501 (2017).

Karsa, A. & Pirandola, S. Noisy receivers for quantum illumination. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 35, 22 (2020).

Ganapathy, D. et al. Broadband quantum enhancement of the ligo detectors with frequency-dependent squeezing. Phys. Rev. X 13, 041021 (2023).

Fisher, R. A. Theory of statistical estimation. In Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, (ed. Green, B. J.) 700–725 (Cambridge University Press, 1925).

Rao, C. R. Information and the accuracy attainable in the estimation of statistical parameters. In Breakthroughs in Statistics (eds. Kotz, S., Johnson, N. L.) 561 (Springer, New York, USA, 1992).

Cramér, H. Mathematical Methods of Statistics (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA, 1999).

Helstrom, C. W. Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory 1st edn, Vol. 231–252 (Academic press, 1976).

Holevo, A. S. Probabilistic and Statistical Aspects of Quantum Theory, 1st edn, Vol. 340 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Braunstein, S. L. & Caves, C. M. Statistical distance and the geometry of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3439 (1994).

Liu, J., Yuan, H., Lu, X.-M. & Wang, X. Quantum fisher information matrix and multiparameter estimation. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 53, 023001 (2020).

Serafini, A. Quantum Continuous Variables: A Primer of Theoretical Methods 1st edn, Vol. 368 (CRC Press, 2017).

Skolnik, M. I. et al. Introduction to Radar Systems (McGraw-hill New York, 1980)

Lee, J., Li, Y.-A., Hung, M.-H. & Huang, S.-J. A fully-integrated 77-ghz fmcw radar transceiver in 65-nm CMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid State Circ.45, 2746 (2010).

Cooper, K. B., Dengler, R. J., Llombart, N., Thomas, B., Chattopadhyay, G. & Siegel, P. H. Thz imaging radar for standoff personnel screening. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 1, 169 (2011).

Kokkoniemi, J., Lehtomäki, J. & Juntti, M. A discussion on molecular absorption noise in the terahertz band. Nano Commun. Netw. 8, 35 (2016).

Yang, Z. et al. A squeezed quantum microcomb on a chip. Nat. Commun. 12, 4781 (2021).

Herman, D. I. et al. Squeezed dual-comb spectroscopy, Science 0,eads6292 (2025).

Ippolito, L. J., Kaul, R. & Wallace, R. Propagation Effects Handbook for Satellite Systems Design 3rd edn (National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC, 1981).

Takeoka, M., Seshadreesan, K. P., You, C., Izumi, S. & Dowling, J. P. Fundamental precision limit of a mach-zehnder interferometric sensor when one of the inputs is the vacuum. Phys. Rev. A 96, 052118 (2017).

Slaoui, A., Drissi, L. B., Saidi, E. H. & Laamara, R. A. Analytical techniques in single and multi-parameter quantum estimation theory: a focused review. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv:2204.14252 (2022).

Guha, S. Structured optical receivers to attain superadditive capacity and the holevo limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 240502 (2011).

Helstrom, C. W. Quantum detection and estimation theory. J. Stat. Phys. 1, 231 (1969).

Sanz, M., Las Heras, U., García-Ripoll, J. J., Solano, E. & Di Candia, R. Quantum estimation methods for quantum illumination. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 070803 (2017).

Shi, H., Zhang, Z. & Zhuang, Q. Practical route to entanglement-assisted communication over noisy bosonic channels. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 034029 (2020).

Lawler, G. F. & Limic, V. Random Walk: a Modern Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Personick, S. Application of quantum estimation theory to analog communication over quantum channels. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 17, 240 (1971).

Yuen, H. & Lax, M. Multiple-parameter quantum estimation and measurement of nonselfadjoint observables. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 19, 740 (1973).

Rubio, J. & Dunningham, J. Bayesian multiparameter quantum metrology with limited data. Phys. Rev. A 101, 032114 (2020).

Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R., Górecki, W. & Guţă, M. Multi-parameter estimation beyond quantum fisher information. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 53, 363001 (2020).

Pirandola, S. & Lloyd, S. Computable bounds for the discrimination of gaussian states. Phys. Rev. A 78, 012331 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Science Foundation CAREER Award CCF-2142882, the National Science Foundation (NSF) Engineering Research Center for Quantum Networks Grant No. 1941583, Office of Naval Research (ONR) Grant No. N00014-23-1-2296, National Science Foundation OMA-2326746, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under Young Faculty Award (YFA) Grant No. N660012014029. QZ also acknowledge supports from Halliburton Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. proposed the study. X.Z. performed the analyses and calculations, under the supervision of Q.Z. Z.Z. contributed to the modeling of the physical systems. X.Z. generated all figures. X.Z. and Q.Z. wrote the manuscript, with inputs Z.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Z.Z. and Q.Z. are Editorial Board Members for Communications Physics, but were not involved in the editorial review of or the decision to publish this article. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Giacomo Sorelli and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, X., Zhang, Z. & Zhuang, Q. Quantum illumination networks. Commun Phys 8, 54 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01968-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01968-8