Abstract

Extremely large magnetoresistance (XMR) is typically observed in topological materials as associated with factors such as high mobility carriers and electron-hole compensation. However, its occurrence in magnetic materials is rather rare due to the stability of the electron spin in magnetic fields. In this study, the synthesis of high-quality single crystals of Fe2Ge3 with the highest residual resistivity ratio (RRR = 4778) has allowed to explore its intrinsic magnetic and electrical transport properties, revealing a narrow-gap semiconductor nature with a high XMR of 2057% at 1.8 K and 12 T. In addition, Fe2Ge3 is able to bridge the gap between magnetism and XMR. These findings not only advance our understanding of Fe2Ge3, but also open avenues for the development of spintronic devices and other technologies based on magnetic semiconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

XMR is characterized by a dramatic increase in resistance when an external magnetic field is applied, typically within the range of 103 to 108%1. This phenomenon has been observed in various non-magnetic materials, particularly related to 2D materials2,3,4 and topological matters5,6,7. The XMR observed in these materials is generally attributed to factors such as electron-hole compensation8,9, high RRR10,11,12, high-mobility carriers13,14,15, or topologically protected electronic states16,17. In magnetic materials, the electron spin direction remains relatively stable when exposed to a magnetic field, leading to a reduced impact on electron scattering and minimal resistance change under the magnetic field18,19,20,21. This makes XMR quite rare in magnetic materials. However, magnetism order provides the ability to control the spin direction within the material, while XMR allows for substantial modulation of electrical transport properties, making it highly promising for applications in spintronics and magnetic memory devices22.

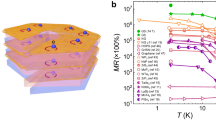

Magnetic semiconductors integrate the tunable electrical properties of semiconductors with magnetic spin properties, which is critical for the development of spintronic devices. The incorporation of magnetic metal elements into non-magnetic semiconductors is a common method for inducing magnetism23,24. Achieving stable ferromagnetism alongside superior electrical transport properties in semiconductor materials remains a challenge. β-FeSi2 nanocubic particles exhibited saturated magnetization up to 15 emu g-1 with Curie temperature (TC) around 800 K, achieving strong and stable room temperature ferromagnetism25. Theoretical calculations indicate that FeSb2 exhibits properties characteristic of a nearly ferromagnetic narrow-gap semiconductor, in analogy to FeSi26,27,28. The Fe-Ge system displays complex magnetic properties29,30 and theoretical calculations and experimental results confirm that Fe2Ge3 is a narrow-gap semiconductor31. We hypothesise that it is likely to be part of the iron-based magnetic semiconductors, which would provide a direction in the search for qualified materials for field-sensitive device applications.

In this paper, high-quality single crystals of Fe2Ge3 were synthesized to investigate its intrinsic physical properties. The magnetic and electrical transport properties were systematically investigated and the discovery of several phenomena is noteworthy. Energy band calculations show that Fe2Ge3 is a narrow-gap semiconductor with a band gap of <0.1 eV, while experimental results show that resistivity exhibits metallic behavior and a very high RRR. The observed XMR of 2057% at 1.8 K and 12 T without any sign of saturation is distinct from previous reports31,32. Hall data suggest that the electrical transport properties are influenced by both electron and hole carriers, and the XMR at low temperatures can be attributed to high hole mobility and the large RRR. It has also been found that Fe2Ge3 remains magnetic at ultra-high temperatures. All results indicate that Fe2Ge3 is a magnetic semiconductor exhibiting remarkable XMR, with potential applications in magnetic sensors, information storage, spin quantum science and quantum technology.

Results and discussion

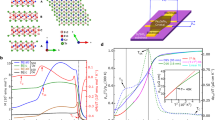

High-quality single crystals of Fe2Ge3 were synthesized using the chemical vapor transport method. As shown in Fig. 1a, Fe2Ge3 single crystals have a tetragonal structure with the space group of P\(\bar{4}\)c2 (No. 116)32,33. The typical features of the Nowotny chimney-ladder phase are observed, consisting of a sublattice of iron atoms forming chimneys and germanium atoms forming ladders. The periodicities of these two sublattices are not necessarily commensurate along the c-axis. Figure 1b depicts a scanning electron microscopy image of the single crystal and the X-ray diffraction spots observed in three distinct orientations. The crystal data and structure refinement results obtained from single-crystal X-ray diffraction are presented in Supplementary Table S1 and Table S2, respectively. The refined lattice parameters are a = b = 5.595(3) Å, c = 8.930(4) Å, which are slightly smaller than those previously reported31,32,34. The X-ray diffraction pattern in Fig. 2c reveals sharp Bragg (100) peaks with no detectable impurity peaks. The Laue diffraction pattern (inset in Fig. 2c) of Fe2Ge3 along the a-axis displays clear and bright diffraction spots, indicating the high crystallinity of the single crystal.

a Crystal structure of Fe2Ge3 single crystal. The pink and purple balls represent Fe and Ge atoms. b Scanning electron microscope image of the Fe2Ge3 crystal and the diffraction spots observed with X-ray single-crystal diffraction at 293 K in three different orientations. c X-ray diffraction and Laue diffraction pattern along the a-axis of Fe2Ge3. d The temperature (T) dependence of transverse resistivity ρxx at zero magnetic field. Inset: low-temperature data fitted to ρ = ρ0 + aT2, where residual resistance ρ0 is the resistance when T tends to 0 K and a is the constant. e Electronic energy band structure of Fe2Ge3 obtained from first principles calculations. The vertical coordinate is the energy difference of the electron energy with respect to the Fermi energy level and the energy coordinate is the point of high symmetry in crystal momentum space (f) Orbital projected electronic energy band structure and the symbol size is positively related to the density of states. g Density of states (DOS). The inset shows the Brillion zone of the tetragonal structure.

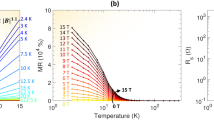

a Magnetoresistance (MR) as a function of magnetic field at different temperatures. b Kohler plots showing MR as a function of B/ρxx(0), B is magnetic induction intensity and B = μ0H, μ0 is the magnetic conductivity of the vacuum and H is magnetic field strength. c MR is fitted with Bα (α is exponential) in both low (solid line) and high field (dashed line) regions at 1.8 K. The lower inset shows MR at 30 K, which can be fitted by quadratic polynomial in the whole measured field region. The upper inset shows α fitted to MR at different temperatures under low fields (red) and high fields (blue). d Magnetic field dependence of Hall resistivity ρxy from 1.8 K–200 K. Inset: experimental data at 1.8 K (black line) and nonlinear fits based on the two-carrier model (red line). e, f Temperature dependence of carrier mobility μe, h and the carrier density ne, h for both electrons and holes. The inset in (f) shows the ratio between two types of carriers.

Figure 1d shows the temperature dependence of resistivity for Fe2Ge3 in the absence of magnetic field, with current along the c-axis. The sample shows a typical metallic behavior with the RRR = ρ(300 K)/ ρ(1.8 K) = 4778, where ρ(300 K) = 9.895 mΩ cm, ρ(1.8 K) = 2.071 μΩ cm, indicating the high quality of the crystal. As shown in the inset of Fig. 1d, ρ(T) can be well fitted using the Landau Fermi liquid formula \(\rho ={\rho }_{0}+{\mbox{a}}{T}^{2}\) below 12 K, suggesting that the electron-electron scattering dominates the transport behavior. The extracted residual resistivity ρ(T = 0) is around 1 μΩ cm, which is comparable with the well-known XMR topological semimetals such as WTe2 (2 μΩ cm)5, TaAs2 (0.7 μΩ cm)35,36 and NbP(0.63 μΩ cm)4, and is 10 times lower than that of Cd3As2 (28.2 μΩ cm)37, indicating that the sample contains minimal impurities or defects.

Based on the observed lattice parameters, the band gap structure is calculated based on first-principles theory. It is revealed that Fe2Ge3 is a narrow-gap semiconductor, with a narrow band gap of 0.093 eV (Fig. 1e). V. Y. Verchenko et al. reported similar calculation results31. The band gap of <0.1 eV is extremely narrow, so the electrons can be easily excited to the conduction band, thereby exhibiting a certain degree of conductivity. This explains the metallic properties, whereby the resistance increases monotonicaly with increasing temperature. As shown in Fig. 1f, the orbital-protected band structure of the d-orbitals of Fe and the p-orbitals of Ge is depicted. The top of the valence band is characterized by an almost parabolic maximum of the Ge-p band situated at the Γ point within the Brillouin zone. Conversely, the bottom of the conduction band is predominantly constituted by the flat Fe-d orbitals with a minimum at the same Γ point. The total DOS of Fe2Ge3, as well as the element-specific partial DOS (PDOS) of Fe and Ge atoms, are illustrated in Fig. 1g. The DOS near the Fermi level predominantly consists of the PDOS of Fe atoms and is primarily influenced by the d-orbitals of Fe.

A previously unreported XMR of 2057% at 1.8 K and 12 T is observed as shown in Fig. 2a. The MR shows a strong temperature dependence, which decreases with increasing temperature, and becomes negaligible above 30 K. The Kohler fits at different temperatures are plotted in Fig. 2b. The scaled MR curves do not converge to a single curve. The violation of Kohler rule suggests a nonnegligible variation of electron scattering with temperature38,39,40,41, and the orbital quantization effect in terms of the variation of carrier mobility and carrier density with temperature must be taken into account.

The MR curves of Fe2Ge3 exhibit different magnetic field dependencies and the trends are distinct at different temperatures (temperature dependence of resistivity under external magnetic fields in Supplementary fig. S2 and Supplementary Discussion 1), suggesting that the origin of XMR is complex and may involve other mechanisms. A power law dependence MR∝Bα can be found, and the index α varies with temperature. At 1.8 K, the field dependence of MR can be roughly divided into two regions, yielding α = 1.3 below B = 1.5 T and α = 0.8 above 4 T. Similarly, MR is fitted at different temperatures in 0–1.5 T and 4–12 T ranges, and the resulting parameter α is shown in the upper inset of Fig. 2c. In low field region α ~ 1.2 is nearly temperature independent, while in high field region α increases monotonically with increasing temperature, reaching 1.8 at 30 K. A linear MR is often observed in high magnetic fields in Dirac semimetals42,43,44, whereas in conventional metals α = 2 is expected45,46. A possible explanation for the complex temperature dependence of α is that there is an approximately quadratic approach to the Ge-p orbit near the Fermi level. This complex relationship has been observed in other XMR materials, for example, in Ga single crystal α changes from 1.787 (T = 2 K) to 1.5 (T = 30 K)47 and in MoP2 α increases with increasing temperature and saturates at 1.748. The MR fitting at 30 K results in MR = 3.03*10-10*B2 + 4.45*10-5*B + 0.116 (lower inset of Fig. 2c) with a trace of a linear contribution, but the quadratic term dominates in MR. The observed MR∝B2 behavior is in accordance with the perfect carrier compensation mechanism, which is clearly different from the trend of MR at low temperatures.

To obtain related information about the charge carriers in Fe2Ge3, the Hall effect has been measured at various temperatures as shown in Fig. 2d. It can be seen that the curves of Hall resistivity versus magnetic field clearly deviate from the linear dependence at low temperatures, indicating the presence of at least two types of carriers in Fe2Ge3. A two-carrier model (Eq. 1) is used to fit the Hall resistivity, from which the carrier density and mobility can be deduced. The two-band model is given by the following equation49:

where ne (nh) is the charge density of electrons (holes), μe (μh) is the mobility of electrons (holes). When ne = nh, i.e., at the perfect compensation condition, MR is supposed to follow B2 and Hall resistivity is expected to be proportional to B50. The inset of Fig. 2d shows the fitting to the data at 1.8 K, which yields carrier densities of ne = 9.42 × 1021 cm-3, nh = 4.62 × 1019 cm-3 and the corresponding carrier mobilities of μe = 6.89 cm2V-1s-1, μh = 1087 cm2V-1s-1. The temperature dependences of the carrier mobility and the carrier density are shown in Fig. 2e, f, respectively. Below 30 K, the density of electrons is found much larger than that of holes, and the carrier transport is dominated by holes. This may be due to the smaller effective mass of holes at low temperatures and their movement in the lattice is affected by less scattering. The hole density is almost unchanged with increasing temperature, the energy gap of Fe2Ge3 semiconductors is only 0.093 eV, which is characteristic of degenerate semiconductor behavior. The rather small MR above 30 K indicates that the electron-hole compensation does not contribute to the MR. Considering all possible factors, the origin of XMR at low temperatures in Fe2Ge3 can be mostly attributed to the high hole mobility and large RRR values.

It is well known that the Fermi surface symmetry is closely related to the anisotropy of the resistivity. In order to explore the Fermi surface symmetry of Fe2Ge3 and to check whether the electronic structure is altered by temperature and magnetic field, the angle-dependent magnetoresistance was measured at different temperatures and magnetic fields. Figure 3a illustrates the schematic of the measurement, depicting the current alignment along the c-axis and the magnetic field rotation in the ab-plane with an angle θ respect to the a-axis. The MR displays a substantial anisotropy with a two-fold symmetry below 30 K (Fig. 3b–d) in the applied field region. A maximum MR at θ = 90° (b-axis) and a minimum MR at θ = 0° (a-axis) are observed. Above 30 K, the MR becomes isotropic with the value close to 80% at 12 T and 55% at 2 T, respectively. The polar plot of MR shows the symmetry of the projected profile of the Fermi surface in ab-plane perpendicular to the current. It is reasonable to hypothesize that the Fermi surface of the ab-plane is anisotropic at low temperatures, which disappears above a certain temperature. This is also consistent with the observed deviation of hole and electron carrier densities below 30 K in Fig. 2f.

a Schematic of the experimental configuration for angle-dependent magnetoresistance. B is the magnetic field direction and I is the current direction. The magnetic field rotates in the ab-plane, the angle of rotation is θ and the angle of magnetic field with respect to the a-axis. b–f Polar plots of the angle dependence of magnetoresistance at different temperatures and magnetic fields.

The magnetic properties of Fe2 Ge3 were investigated through magnetic susceptibility versus temperature (χ-T ) curves measured under zero-field-cooling (ZFC) and field-cooling (FC) conditions at μ0H = 0.1 T, as well as isothermal magnetization loops (M-H). During the measurements, the magnetic field was applied along H // ab. As shown in Fig. 4a, the magnetic susceptibility continuously decreases with increasing temperature up to room temperature and does not follow the Curie-Weiss law. Beyond room temperature, the magnetization further decreases up to 850 K without reaching saturation, indicating that the single crystal is not paramagnetic and suggesting a ferromagnetic state with a high TC above 300 K. In the high-temperature region, the decreasing trend of magnetization shows bends and turns (Fig. 4b), highlighting the complexity of the magnetic behavior that warrants further investigation. Moreover, the hysteresis loops measured from 1.8 K (with a coercivity of 235 Oe) to 800 K (with a coercivity of 51 Oe) confirm the presence of potential room-temperature ferromagnetic ordering in Fe2 Ge3 single crystals. In order to eliminate the influence of possible impurities on the surface, the samples were polished to a surface roughness of <8 nm, which showed that the magnetizsation had no difference from that of the unpolished samples and hysteresis was still observed at 800 K (Supplementary fig. S5). Additionally, the continuous increase in magnetization with the applied magnetic field suggests a possible coexistence of antiferromagnetic interactions. A more detailed analysis of the magnetic structure is necessary to fully understand these observations.

a, b The temperature (T) dependence of magnetic susceptibility (χ) curves with the magnetic field along ab-plane. c, d The magnetic hysteresis curves at different temperatures. e Summary of magnetic materials that exhibit large magnetoresistance18,19,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. The bar graph represents magnetoresistance and the scatter plot represents residual resistivity ratio (RRR). Antiferromagnetic compounds are marked in blue, ferromagnetic compounds in green, and red is for Fe2Ge3 in this work.

The observation of magnetism in the semiconductor Fe2Ge3 with XMR is surprising. In magnetic materials, MR is typically small or negative due to spin disorder scattering. Figure 4e lists the MR and RRR values of different magnetic materials. Among all the magnetic materials EuGa4 shows the largest nonsaturating MR up to 40 T as a consequence of the node ring state51. CoS2 is an excellent soft ferromagnet (TC = 124 K) with linear positive MR of 500% among known magnetic topological materials52. The maximum MR observed in ferromagnetic MnBi (TC> 630 K) reaches only 250%53,54. The MR of ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal Co3Sn2S2 is around 50%18. It is noteworthy that the carrier mobilities of CoS2 (μh ~ 6100 cm2V-1s-1, μe ~ 820 cm2V-1s-1) and MnBi (μh = μe = 5000 cm2V-1s-1) are considerably higher than that of Fe2Ge3, yet the MR value is an order of magnitude lower, suggesting that the high RRR of the Fe2Ge3 plays a critical role in facilitating XMR. Among all the magnetic magetrials, Fe2Ge3 shows the largest MR except for EuGa4, while keeps the record MR value among all the materials showing ferromagnetism. In consideration of the magnetism, XMR, and semiconducting electronic structures, Fe2Ge3 and compounds of homologous elements are potential candidates for the development of spintronics.

Conclusion

In summary, this study elucidates the unique properties of high-quality Fe2Ge3 single crystals, a narrow-gap semiconductor that exhibits XMR of 2057% and magnetism. The synthesis of high-quality single crystals and comprehensive investigations of its magnetic and electrical properties contribute valuable insights into the Fe-Ge system, paving the way for further exploration of iron-based magnetic semiconductors and their applications in next-generation technologies. Our results enhance the understanding of XMR and provide directions in search for XMR materials. The combination of magnetism and XMR in this material bridges a critical gap, offering opportunities for technological applications in spintronics, quantum science, and magnetic memory devices.

Experimental Section

The single crystalline Fe2Ge3 were grown using chemical vapor transport method. Before the growth, polycrystalline Fe2Ge3 were first prepared by solid-state reaction. High purity iron (aladdin, 99.99%) and germanium powders (aladdin, 99.999%) were mixed thoroughly in a 2: 3 molar ratio and sealed in an evacuated quartz tube. The quartz tube was rapidly heated to 1000 °C and kept for 5 days, then maintained at 700 °C for an additional 5 days. The polycrystalline pellets were reground into powder and sealed in quartz tubes together with 5 mg cm-3 iodine as the transport agent. The source and sink zone temperatures were set to 700 °C and 600 °C for 2 weeks, respectively. Fe2Ge3 single crystals with metallic luster were obtained at the cold end with a maximum length of 2 mm and a cross section of 1 × 1.5 mm². Prior to testing, soak samples in anhydrous ethanol and clean with ultrasound.

The crystal structure was studied using the X-ray diffraction (XRD, D2 Bruker) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) at room temperature. X-ray back reflection Laue crystal diffraction (TDF-3000) was used to check the quality of single crystals and to determine the crystallographic orientation. The Fe: Ge composition of 40.2: 59.8 was confirmed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (see Supplementary fig. S1). The crystal structure and lattice parameters were collected using a single crystal X-ray diffractometer, and the data were analyzed using Jana software. Electrical transport properties were studied by the Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS-14 T, Quantum Design). Magnetization measurements were conducted using a Magnetic Property Measurement System (MPMS-7 T, Quantum Design). Electrical and magnetic transport properties of different Fe2Ge3 samples are shown in Supplementary fig. S3-S4 and Supplementary Discussion 2.

The electronic band structure of Fe2Ge3 was calculated using first-principles methods based on the density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the DS-Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) program under the Device Studio platform. The DS-PAW is based on the plane-wave basis and the PAW representation. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation energy functional within the generalized gradient approximation was employed. In the calculations, the atomic positions were fully relaxed until the force on each atom was <0.02 eV Å-1, with an electronic iteration convergence criterion set to 10-5 eV. The wave functions are expanded in plane waves up to a kinetic energy cutoff of 600 eV. The Brillouin zone integration was performed using a k-point sampling mesh of 5 × 5 × 5, generated according to the Gamma-centered method. The exploration data for the relevant parameters and the electron density can be seen in Supplementary fig. S6-S8 and Supplementary Discussion 3.

Data availability

All the data are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

Niu, R. & Zhu, W. Materials and possible mechanisms of extremely large magnetoresistance: a review. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 113001 (2021).

Xu, C. et al. Topological type-II Dirac fermions approaching the Fermi level in a transition metal dichalcogenide NiTe2. Chem. Mater. 30, 4823–4830 (2018).

Zhao, L. et al. Magnetotransport properties in a compensated semimetal gray arsenic. Phys. Rev. B 95, 115119 (2017).

Shekhar, C. et al. Extremely large magnetoresistance and ultrahigh mobility in the topological Weyl semimetal candidate NbP. Nat. Phys. 11, 645–649 (2015).

Ali, M. N. et al. Large, non-saturating magnetoresistance in WTe2. Nature 514, 205–208 (2014).

Keum, D. H. et al. Bandgap opening in few-layered monoclinic MoTe2. Nat. Phys. 11, 482–486 (2015).

Mangelsen, S. et al. Large nonsaturating magnetoresistance and pressure-induced phase transition in the layered semimetal HfTe2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205148 (2017).

Luo, Y. et al. Electron-hole compensation effect between topologically trivial electrons and nontrivial holes in NbAs. Phys. Rev. B 92, 205134 (2015).

Xu, J. et al. Origin of the extremely large magnetoresistance in the semimetal YSb. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075159 (2017).

Gong, J. X. et al. Non-stoichiometry effects on the extreme magnetoresistance in Weyl semimetal WTe2. Chin. Phys. Lett. 35, 097101 (2018).

Ali, M. N. et al. Correlation of crystal quality and extreme magnetoresistance of WTe2. Europhys. Lett. 110, 67002 (2015).

Xing, L., Chapai, R., Nepal, R. & Jin, R. Topological behavior and zeeman splitting in trigonal PtBi2-x single crystals. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 10 (2020).

Kumar, N. et al. Extremely high magnetoresistance and conductivity in the type-II Weyl semimetals WP2 and MoP2. Nat. Commun. 8, 1642 (2017).

Mondal, R. et al. Extremely large magnetoresistance, anisotropic hall effect, and Fermi surface topology in single-crystalline WSi2. Phys. Rev. B 102, 115158 (2020).

Dasoundhi, M. K., Baral, S., Rajput, I., Kumar, D. & Lakhani, A. Extremely large magnetoresistance and non-trivial band topology in YSb semimetal. Mater. Today Phys. 40, 101310 (2024).

Wang, Z., Weng, H., Wu, Q., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Three-dimensional Dirac semimetal and quantum transport in Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125427 (2013).

Liang, D. D. et al. Extreme magnetoresistance and shubnikov-de haas oscillations in ferromagnetic DySb. APL Mater. 6, 086105 (2018).

Liu, E. et al. Giant anomalous hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1125–1131 (2018).

Ye, L. et al. Massive Dirac fermions in a ferromagnetic kagome metal. Nature 555, 638–642 (2018).

Sakai, A. et al. Giant anomalous Nernst effect and quantum-critical scaling in a ferromagnetic semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1119–1124 (2018).

Hu, J. & Rosenbaum, T. F. Classical and quantum routes to linear magnetoresistance. Nat. Mater. 7, 697–700 (2008).

Zhang, Z. et al. Memory materials and devices: from concept to application. InfoMat 2, 261–290 (2020).

Wang, R., Steckl, A. J., Nepal, N. & Zavada, M. Electrical and magnetic properties of GaN codoped with Eu and Si. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 103901 (2010).

Deng, J. et al. Ferromagnetism with high curie temperature of Cu doped LiMgN new dilute magnetic semiconductors. Front. Mater. 7, 595953 (2021).

He, Z. et al. Strong facet-induced and light-controlled room-temperature ferromagnetism in semiconducting β-FeSi2 nanocubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11419–11424 (2015).

Lukoyanov, A. V., Mazurenko, V. V., Anisimov, V. I., Sigrist, M. & Rice, T. M. The semiconductor-to-ferromagnetic-metal transition in FeSb2. Eur. Phys. J. B 53, 205–207 (2006).

Takahashi, H., Okazaki, R., Yasui, Y. & Terasaki, I. Low-temperature magnetotransport of the narrow-gap semiconductor FeSb2. Phys. Rev. B 84, 205215 (2011).

Yang, B. et al. Atomistic investigation of surface characteristics and electronic features at high-purity FeSi (110) presenting interfacial metallicity. Proc. Nat., Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2021203118 (2021).

Hashizume, M., Yokouchi, T., Nakagawa, K. & Shiomi, Y. Anisotropic magneto-seebeck effect in the antiferromagnetic semimetal FeGe2. Phys. Rev. B 104, 115109 (2021).

Kúkoľová, A. et al. Cubic, hexagonal and tetragonal FeGex phases (x = 1, 1.5, 2): Raman spectroscopy and magnetic properties. CrystEngComm 23, 6506–6517 (2021).

Verchenko, V. Y. et al. Crystal growth of the Nowotny chimney ladder phase Fe2Ge3: exploring new Fe-based narrow-gap semiconductor with promising thermoelectric performance. Chem. Mater. 29, 9954–9963 (2017).

Xu, Y. et al. Single crystal growth and thermoelectric properties of Nowotny chimney-ladder compound Fe2Ge3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 125404 (2023).

Sato, N., Ouchi, H., Takagiwa, Y. & Kimura, K. Glass-like lattice thermal conductivity and thermoelectric properties of incommensurate chimney-ladder compound FeGeγ. Chem. Mater. 28, 529–533 (2016).

Le Tonquesse, S. et al. Crystal structure and high temperature X-ray diffraction study of thermoelectric chimney-ladder FeGeγ (γ ≈ 1.52). J. Alloy. Comd. 846, 155696 (2020).

Wang, Y. Y., Yu, Q. H., Guo, P. J., Liu, K. & Xia, T. L. Resistivity plateau and extremely large magnetoresistance in NbAs2 and TaAs2. Phys. Rev. B 94, 041103 (2016).

Yuan, Z., Lu, H., Liu, Y., Wang, J. & Jia, S. Large magnetoresistance in compensated semimetals TaAs2 and NbAs2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 184405 (2016).

Zhao, Y. et al. Anisotropic Fermi surface and quantum limit transport in high mobility three-dimensional Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031037 (2015).

Xu, J. et al. Extended Kohler’s rule of magnetoresistance. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041029 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Anisotropic magnetotransport and exotic longitudinal linear magnetoresistance in WTe2 crystals. Phys. Rev. B 92, 041104 (2015).

Leahy, I. A. et al. Nonsaturating large magnetoresistance in semimetals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10570–10575 (2018).

Wang, Y. L. et al. Origin of the turn-on temperature behavior in WTe2. Phys. Rev. B 92, 180402 (2015).

Zhang, C. et al. Room-temperature chiral charge pumping in Dirac semimetals. Nat. Commun. 8, 13741 (2017).

Savvidou, A. et al. Anisotropic positive linear and sub-linear magnetoresistivity in the cubic type-II Dirac metal Pd3In7. npj Quant. Mater. 8, 68 (2023).

Campbell, D. et al. Topologically driven linear magnetoresistance in helimagnetic FeP. npj Quant. Mater. 6, 38 (2021).

Du, J. et al. Extremely large magnetoresistance in the topologically trivial semimetal α-WP2. Phys. Rev. B 97, 245101 (2018).

Tafti, F., Gibson, Q., Kushwaha, S., Haldolaarachchige, N. & Cava, R. Resistivity plateau and extreme magnetoresistance in LaSb. Nat. Phys. 12, 272–277 (2016).

Chen, B. et al. Large magnetoresistance and superconductivity in α-gallium single crystals. npj Quant. Mater. 3, 40 (2018).

Wang, A. et al. Magnetotransport properties of MoP2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 195107 (2017).

Liang, T. et al. Ultrahigh mobility and giant magnetoresistance in the Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 14, 280–284 (2015).

Luo, Y. et al. Hall effect in the extremely large magnetoresistance semimetal WTe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 182411 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Giant magnetoresistance and topological hall effect in the EuGa4 antiferromagnet. J. Phys. Condens Mat. 34, 034005 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Scaling of berry-curvature monopole dominated large linear positive magnetoresistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2208505119 (2022).

McGuire, M. A., Cao, H., Chakoumakos, B. C. & Sales, B. C. Symmetry-lowering lattice distortion at the spin reorientation in MnBi single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 90, 174425 (2014).

He, Y. et al. Large linear non-saturating magnetoresistance and high mobility in ferromagnetic MnBi. Nat. Commun. 12, 4576 (2021).

Hirschberger, M. et al. The chiral anomaly and thermopower of Weyl fermions in the half-Heusler GdPtBi. Nat. Mater. 15, 1161–1165 (2016).

Kang, M. et al. Dirac fermions and flat bands in the ideal kagome metal FeSn. Nat. Mater. 19, 163–169 (2020).

Lyu, M. et al. Nonsaturating magnetoresistance, anomalous hall effect, and magnetic quantum oscillations in the ferromagnetic semimetal PrAlSi. Phy. Rev. B 102, 085143 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 12174242, 11804217) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant No. 2018YFA0704300). Z.L. acknowledges the financial supports by the Shenzhen research funding (GXWD20231130102757002) and GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025A1515011863). J.-Y.G. also thanks the support by the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning. We acknowledge HZWTECH for providing computation facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-Y.G conceived the idea and designed the experiments. Y.-Q.C and W.-W.B. grew the samples and performed the experiments. Y.-Q.C, W.-W.B., Y.-X.H, J.-Y.Z, T.H, Z.L. and J.-Y.G analyzed the data. Y.-Q.C. drafted the original manuscript. Z.L., Q.-L.X and J.-Y.G. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, YQ., Wu, WB., He, YX. et al. Extremely large magnetoresistance in high quality magnetic Fe2Ge3 single crystals. Commun Phys 8, 116 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02041-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02041-0