Abstract

Floquet modulation plays a crucial role in manipulating the phases of quantum matter. However, experimentally characterizing the Floquet topological phase transition, particularly in one-dimensional systems, remains challenging. In this study, we investigate the Floquet topological phase transition within the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model in room-temperature superradiance lattices. Due to their resilience to thermal noise, superradiance lattices can undergo strong phase modulation to synthesize an effective AC electric field via Peierls substitution. Since the one-dimensional momentum-space Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model breaks time-reversal symmetry, we can classify the topologically distinct phases through optical nonreciprocity. We observe the topological phase transition induced by effective AC and DC electric fields, successfully mapping the complete phase diagram. Our results provide a novel spectroscopic approach to characterizing the topological phase transitions of Zak phases, which can contribute to the exploration of other non-equilibrium topological phases under strong modulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Floquet engineering has emerged a powerful tool for manipulating quantum states, enabling a range of applications such as freezing transport in lattices1,2,3,4, opening energy gaps to modify electronic properties5,6, and improving the precision of optical clocks7. More importantly, it plays a pivotal role in quantum simulation, especially in the study of topological matters8,9. By breaking time-reversal symmetry through temporal modulation, Floquet engineering facilitates the realization of artificial gauge fields10,11 and the Haldane model12,13, which features nonzero Chern numbers, marking a significant milestone in simulating topological phenomena. Furthermore, this technique not only enables the exploration of anomalous Floquet topological phases which do not exist in equilibrium systems14,15,16, but also allows for the investigation of two-dimensional (2D) and even higher-dimensional topological effects in a zero-dimensional qubit using synthetic frequency dimensions17,18.

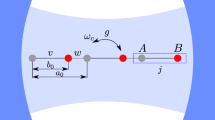

The Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model19 stands out as a minimal one-dimensional (1D) topological insulator, whose topological invariant is the geometric Zak phase20. In contrast to characterizing the Chern number in 2D systems, measuring the Zak phase in the SSH model, where inversion symmetry is broken rather than time-reversal symmetry, is fundamentally different. Conventionally, the Zak phase is characterized through interferometry21 or tracking dynamical evolution22,23. However, these methods rely on adiabatic quantum operations and prolonged quantum coherence, which intrinsically conflict with the heating effects associated with strong Floquet driving. Therefore, direct mapping of the Zak phase transition in the Floquet SSH model remains challenging. As schematically shown in Fig. 1, the AC electric field induced topological phase transition in the SSH model, which exhibits a rich phase diagram24, has long since been predicted but has yet to be realized.

a Schematics of the SSH model in an AC electric field. The black boxes indicate the choice of unit cell. b Two topological phases of the SSH model. The Hamiltonian is written as H = h ⋅ σ, where σ are the Pauli matrices, and h = (hx, hy, 0). The corresponding Zak phases are ± 0.5π, manifesting opposite winding direction of the vector h.

Here we report the observation of the Floquet topological phase transition in an SSH-type superradiance lattices (SLs)25,26,27 in room-temperature atomic vapor. Operating under ambient conditions, SLs allow for strong phase modulation of the intra- and inter-cell hoppings28, synthesizing an effective AC electric field through Peierls substitution. Since SLs are defined in momentum space, breaking the momentum inversion symmetry (k → − k) is equivalent to breaking time-reversal symmetry (t → − t). As a result, the inversion-symmetry-breaking SSH SLs can exhibit optical nonreciprocity29. By comparing the contrast of the transmission spectra of the probe light from two opposite directions, we determine the Zak phase and thereby map the phase diagrams of the SSH SLs driven by AC fields. Moreover, by taking advantage of the atomic thermal motion28,30,31, we also study the topological phase transition in the presence of the interplay between AC and DC electric fields.

Results

Model

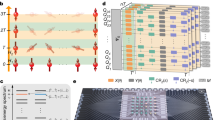

We perform the experiment in a 2 cm long naturally abundant rubidium vapor as shown in Fig. 2. A titanium sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics, Matisse CX, 1 mm e−2 beam width) is divided to two counter-propagating laser fields, represented by wavevectors ± k and Rabi frequencies t1,2, to resonantly couple the excited state \(| b\left.\right\rangle \equiv | {5}^{2}{P}_{1/2},F=2\left.\right\rangle\) and the metastable state \(| a\left.\right\rangle \equiv | {5}^{2}{S}_{1/2},F=2\left.\right\rangle\). A fiber laser (Precilaser, EFL-SF-1590-3-CW, 0.5 mm e−2 beam width) directed into the vapor cell in two opposite directions with the same optical power is used as the probe field, which couples the transition between ground state \(| g\left.\right\rangle \equiv | {5}^{2}{S}_{1/2},F=1\left.\right\rangle\) and the excited state \(| b\left.\right\rangle\). Two high-gain photodiodes detectors (Thorlabs, PDA36A2) are used to simultaneously record the transmission spectra of probes fields when propagating through the 1D SL, constructed by a standing-wave-coupled electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT) configuration, as shown in Fig. 3a). The interaction Hamiltonian of the coupling fields is written as (see Methods for details),

where the phases of coupling fields are modulated by electro-optic modulators (EOMs) with \({\varphi }_{+}={f}_{1}\sin (\omega t)\) and \({\varphi }_{-}=-{f}_{2}\sin (\omega t)\). Here f and ω represent the modulation depth and driving frequency, respectively.

a The temporally driven 1D SL (left) and atomic energy levels (right). The two counter-propagating coupling fields are phase modulated by EOMs with a driving frequency ω = 80 MHz. The topological phase is characterized by the transmission difference of a pair of counter-propagating probe fields. b The spatially and temporally driven atomic ensemble can be mapped to 1D Floquet SL \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}\) in momentum space or (1+1)D static lattice \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\) in synthetic momentum-frequency space. The solid, dashed and dotted lines refer to the hopping strengths modulated by Bessel functons J0, J±1, and J±2, respectively, while the arrows shaded in orange, green and blue indicate the 1D lattice along the \({\hat{m}}_{1}+n{\hat{m}}_{2}\) (n = 0, 1, 2) direction. c Typical transmission spectra. Top panel: the yellow (purple) line T1 (T2) is the transmission spectrum of the probe field along + x ( − x) direction. Bottom panel: the sign of the transmission difference ΔT = T1 − T2 at Δ ≈ nω indicates the Zak phase of the 1D lattices along equalpotential lines \({\hat{m}}_{1}+n{\hat{m}}_{2}\). The peak (dip) corresponds to the Zak phase with + 0.5 π ( −0.5 π). Here the Rabi frequencies are t1 = t2 = 25 MHz and the modulation depths are f1 = 2.5, f2 = 4.7.

Since the Hamiltonian is periodic in both time and space, satifying H(x + 2π/k, t + 2π/ω) = H(x, t), it allows us to expand the system in momentum space \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\), spanned by different momentum states. The quantum state of the atomic ensemble \(| \Psi \left.\right\rangle ={\prod }_{x}\left[\alpha (x,t)| a\left.\right\rangle +\beta (x,t)| b\left.\right\rangle +| g\left.\right\rangle \right]\) can be expanded as,

where the weak excitation approximation is assumed (α, β ≪ 1). The creation operators are defined as \({d}_{{m}_{1}}^{{{\dagger}} }=1/\sqrt{N}{\sum }_{j}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{m}_{1}k{x}_{j}}| {d}_{j}\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.{g}_{j}|\) (d = a, b), with j labeling the position xj of the jth atom and N ≫ 1 being the total number of atoms. The operator \({d}_{{m}_{1}}^{{{\dagger}} }\) creates a timed Dicke state (TDS)32,33,34 from the collectively ground state \(| G\left.\right\rangle \equiv | {g}_{1}\ldots {g}_{N}\left.\right\rangle\),

which carries a momentum of m1ℏk. Taking the Fourier transformation, we obtain the Hamiltonian of a 1D momentum-space SSH model featuring phase modulated intra- and inter-cell hoppings,

Remarkably, the phase modulation of the coupling field \({\varphi }_{\pm }(t)\propto \sin (\omega t)\propto A\) is equivalent to a time-dependent vector potential according to the Peierls substitution. In this framework, we effectively apply an AC electric field \({E}_{{{{\rm{AC}}}}}=-{\partial }_{t}A\propto -\cos (\omega t)\) along the 1D lattice. By exploiting the Floquet theory, we further expand the temporally periodic \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}\) to the direct-product hybrid space \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}\)24,35, where \({{{\mathcal{T}}}}\) is the frequency space spanned by \({{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{m}_{2}\omega t}\), with m2 indicating the m2th Floquet replica (see Fig. 3b). The associated quantum state is,

where \({d}_{{m}_{1},{m}_{2}}^{{{\dagger}} }\equiv {{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}{m}_{2}\omega t}{d}_{{m}_{1}}^{{{\dagger}} }\) (d = a, b) creates a Floquet TDS, absorbing an energy of m2ℏω from the driving fields.

By substituting the ansatz solution (5) into the time-dependent Schrödinger equation \({{{\rm{i}}}}{\partial }_{t}| {\Psi }_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}(t)\left.\right\rangle ={\sum }_{x}H(t)| {\Psi }_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}(t)\left.\right\rangle\), we obtain an effective Hamiltonian \({H}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}={H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}+V\) (see methods). Here \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}={\sum }_{n}{H}^{(n)}\) denotes the (1+1)D tight-binding model in the momentum-frequency space. The nth component H(n) is expressed as28,

which is aligned along the \({\hat{m}}_{1}+n{\hat{m}}_{2}\) direction. Here \({\hat{m}}_{1}\) and \({\hat{m}}_{2}\) are the unit vectors along the momentum and frequency dimensions, respectively, and Jn refers to the nth-order Bessel function. On the other hand, the onsite potential term V corresponds to an effective DC electric field along \(-\delta {\hat{m}}_{1}+\omega {\hat{m}}_{2}\) in the momentum-frequency space24,

where δ = kv results from the Doppler shift of the moving atoms with velocity v (see Methods). Intuitively, this potential term can be understood in the reference frame of the atoms, where the co- and counter-propagating coupling fields experience opposite Doppler shifts of ∓ kv. Consequently, an energy difference arises during the transition from \({a}_{2{m}_{1},{m}_{2}}\) to \({b}_{2{m}_{1}\pm 1,{m}_{2}}\) by absorbing a red-(blue-)shifted photon from the co-(counter-)propagating coupling field, respectively.

Topological phase characterization

In the high-driving-frequency regime, where ω ≫ t1,2, the effective DC electric field localizes the lattice dynamics around the equipotential line, which is perpendicular to the direction of the DC field. When δ ≈ nω (see Fig. 3b for n = 0, 1, 2), the sites on the equipotential line forming 1D lattices described by the Hamiltonian H(n). In real space, it can be written as31,

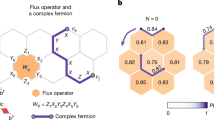

where σ = (σx, σy, σz) are the Pauli matrices and h = (hx, hy, 0) with \({h}_{x}=({\Omega }_{1}^{(n)}+{\Omega }_{2}^{(n)})\cos kx\), \({h}_{y}=({\Omega }_{1}^{(n)}-{\Omega }_{2}^{(n)})\sin kx\), and \({\Omega }_{i}^{(n)}\equiv {t}_{i}{J}_{-n}({f}_{i})\) (i = 1, 2). We use the topological invariant, the Zak phase, to characterize the topology of the driven SLs. Owing to the chiral symmetry in one-dimensional lattices and the periodicity of the Floquet quasi-energy, the Zak phases of the two bands within a single Floquet replica are identical, and they remain invariant across different Floquet sidebands. A change in the Zak phase is accompanied by a band closing, which can occur at either the regular 0 or the anomalous π gap35. For \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(n)}\), the Zak phase is calculated by20,

where \(| {u}_{n}(x)\left.\right\rangle\) is the upper eigenstate satisfying \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(n)}| {u}_{n}(x)\left.\right\rangle =h| {u}_{n}(x)\left.\right\rangle\) with \(h=\scriptstyle\sqrt{{h}_{x}^{2}+{h}_{y}^{2}}\). We notice that the Zak phase of \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(n)}\) is governed by the ratio of the effective hopping strength \(| {\Omega }_{1}^{(n)}/{\Omega }_{2}^{(n)}|\). Therefore, a topological phase transition can be induced by adjusting the two modulation depths f1 and f2. We note that the Zak phase is gauge dependent21, and only the difference between two Zak phases is gauge invariant. In our scheme, the half-π quantization of the Zak phase arises from how the linear potential is introduced in Eq. (7), which effectively fixes the gauge21.

The topological phase of H(n) can be measured using probe fields that couple the ground state \(| g\left.\right\rangle\) to the excited state \(| b\left.\right\rangle\). During the experiment, we introduce the probe field with a detuning Δ, defined as the frequency difference between the probe field and atomic transition, to select the atoms with the Doppler shift δ ≈ Δ28. By setting Δ = nω, we manage to excite the \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\) under the condition δ ≈ nω, which is equivalent to selecting an axis corresponding to the reduced 1D lattice of H(n).

In order to extract the topological phase from the transmission spectrum, we apply two probe fields in opposite directions with momenta ± k. These fields excite the atoms to the Floquet TDS b1,0 and b−1,0, respectively, owing to the phase-matching condition (see Methods). From the perspective of the two opposite probe fields, the roles of the two coupling fields t1 and t2 are interchanged. Therefore, the one directed along − x direction effectively detects the topologically distinct SSH configuration compared to the + x one, with an opposite Zak phase \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}^{{\prime} }=-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\). As demonstrated in our recent work29, the bulk band response of SL with \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.5\pi\) is transparent for the probe field, whereas the one with \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=-0.5\pi\) blocks the transmission. This correspondence between the Zak phase and optical nonreciprocity can be understood by considering three well-established limiting cases in quantum optics. In the symmetric case (t1 = t2), which corresponds to the phase transition point, both probe fields experience strong, identical absorption, a phenomenon known as electromagnetically induced absorption36. In the single-coupling-field limit (t1 = 0 or t2 = 0)37, which can be interpreted as the dimerization limits of the SSH model with opposite Zak phases, the probe field that co-propagates with the coupling field exhibits transparency due to its Doppler-free configuration, while the counter-propagating probe is blocked.

This one-to-one correspondence between optical nonreciprocity and topological phase provides a spectroscopic way to characterize the topological phase transition. Throughout the experiment, we set the driving frequency ω = 80 MHz, which is much larger than the Rabi frequency t1,2, ensuring that the SLs are well described by the effective 1D Hamiltonian H (n). In Fig. 3c, we present typical transmission spectra for the probe fields from opposite directions, along with their difference. The sign of the transmission difference at Δ = nω determines the topological phases of H (n). Specifically, transmission peaks (ΔT > 0, red shaded) correspond to \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.5\pi\) for H (±1) and H (±2) while the dip (ΔT < 0, blue shaded) is associated with \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=-0.5\pi\) regarding H (0).

In Fig. 4b, we plot the transmission difference ΔT = T1(Δ = 0) − T2(Δ = 0) as a function of the modulation depth f1, with f2 = 1.7 held constant. Initially, the lattice has \({\Omega }_{1}^{(0)}\, > \,{\Omega }_{2}^{(0)}\) with \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.5\pi\), leading to ΔT > 0. As we increase the modulation depth f1, the band gap closes at \({\Omega }_{1}^{(0)}={\Omega }_{2}^{(0)}\) (J0(f1) = J0(f2)), marking the topological phase transition point, after which the system jumps into another topological phase where \({\Omega }_{1}^{(0)}\, < \,{\Omega }_{2}^{(0)}\) and \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=-0.5\pi\). The phase transition points measured in Fig. 4b have well agreement with the theoretical prediction (Fig. 4a). We further plot the phase diagrams for two cases, as shown in Fig. 4c t1 = t2 and (d) t1 = 1.5t2. The measured transmission differences ΔT (right panels) demonstrate a good agreement with the Zak phases predictions (left panels). In Fig. 5, we set the probe detuning at Δ = nω (n = 1, 2), and measure the transmission difference, which manifests the optical response from the reduced 1D lattices along equipotential lines \({\hat{m}}_{1}+{\hat{m}}_{2}\) (a) and \({\hat{m}}_{1}+2{\hat{m}}_{2}\) (b). It is noted that the phase transition depicted here is no longer associated with a single isolated Floquet replica, but should be viewed as the interplay between the AC and DC electric fields in a 1D momentum-space SL.

a The 0th Bessel function difference ∣J0(f1)∣ − ∣J0(f2)∣ as a function of f1 with f2 = 1.7. b The transmission difference ΔT(Δ = 0) as a function of f1 with f2 = 1.7 and t1 = t2 = 25 MHz. Insets: schematics of the two topological phases of the 1D lattice H(0). The black dashed lines in (a, b) indicate the phase transition lines. The phase diagrams with different original Rabi frequencies (c) t1 = t2 = 25 MHz and (d) t1 = 30 MHz, t2 = 22 MHz. The left and right panels denote the Zak phase prediction and transmission measurement, respectively. The error bars in (b) represent standard deviation calculated from five independent data points.

The Bessel function difference for (a) ∣J1(f1)∣ − ∣J1(f2)∣ with f2 = 1.3 and (d) ∣J2(f1)∣ − ∣J2(f2)∣ with f2 = 2.1. The transmission difference for (b) ΔT(Δ = ω) with f2 = 1.3 and (e) ΔT(Δ = 2ω) with f2 = 2.1 as a function of f1. The black dashed lines indicate the phase transition lines. Insets: schematics of the topological phases of the associated 1D lattice H(n) along \({\hat{m}}_{1}+n{\hat{m}}_{2}\) for (b) n = 1 and (e) n = 2. The (c, f) present the Zak phase prediction and transmission measurement, respectively. Here the parameters are t1 = t2 = 25 MHz. The error bars represent standard deviation calculated from five independent data points.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the Floquet engineering, when incorporated with SLs in room-temperature atomic vapors, provides an efficient and tunable method for synthesizing and detecting the topological properties of Floquet systems. By leveraging the unique property of the momentum-space lattices, we find that the two topological phases of 1D systems break time-reversal symmetry, allowing us to characterize the topological invariant through optical nonreciprocity. Our method is efficient and straightforward in distinguishing the two topologically distinct states of the SSH model, while a full spectral analysis30,31,38,39 would be required for systems with continuously varying Zak phases (e.g., the Rice-Mele model). We successfully observe the topological phase transition, as well as the associated phase diagram, induced by an effective AC electric field in the SSH model. Furthermore, it is important to note that this characterizing method can also be applied to probe the exotic non-equilibrium phases of matter, such as the anomalous Floquet topological phases14,15,16.

Methods

Effective Hamiltonian

We start from the original Hamiltonian of the standing-wave-coupled EIT configuration,

where x(t) = x0 + vt = x0 + δt/k is the position of the atoms moving with velocity v, Ωp is the Rabi frequency of the probe field, νc,p is the frequency of the coupling and probe fields, respectively, and ωij is the atomic transition frequency between levels \(| i\left.\right\rangle\) and \(| j\left.\right\rangle\). We then transform the Hamiltonian into the interaction picture,

where \(\,{{{\mathcal{U}}}}=\exp (-{{{\rm{i}}}}St)\) and \(S=({\omega }_{ag}+{\nu }_{c})| b\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.b| +{\omega }_{ag}| a\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.a|\). The coupling fields is resonant with the atomic transition frequency νc = ωba, while the probe field has a detuning Δ = νp − ωbg.

Next, we introduce the TDS operators to transform the Hamiltonian of the atomic ensemble \({\sum }_{j}{H}^{{\prime} }({x}_{j},t)\) to momentum space,

where the notation \(| {d}_{{m}_{1}}\left.\right\rangle ={d}_{{m}_{1}}^{{{\dagger}} }| G\left.\right\rangle\) denotes the TDS, and \({H}_{p}=\sqrt{N}{\Omega }_{p}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}\Delta t}{b}_{1}^{{{\dagger}} }+H.c.\) represents the interaction Hamiltonian of the probe field.

According to the Floquet theorem, we further expand the Hamiltonian \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}\) into momentum-frequency space using the Floquet TDS, denoted by \(| {d}_{{m}_{1},{m}_{2}}\left.\right\rangle ={d}_{{m}_{1},{m}_{2}}^{{{\dagger}} }| G\left.\right\rangle\). From the Schrödinger equation \({{{\rm{i}}}}{\partial }_{t}| {\Psi }_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}(t)\left.\right\rangle ={H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}(t)| {\Psi }_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}(t)\left.\right\rangle\), we obtain,

where the nonzero non-diagonal inner products are (T = 2π/ω),

From the dynamic equations in Eq. (13), the (1+1)D lattice is described by the Hamiltonian \({H}_{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}\otimes {{{\mathcal{T}}}}}={\sum }_{n}{H}^{(n)}\) and the onsite potential term V,

The interaction Hamiltonian of the probe field can also be rewritten using the Floquet TDS operator as \({H}_{p}=\sqrt{N}{\Omega }_{p}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}\Delta t}{b}_{1,0}^{{{\dagger}} }+H.c\).

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The simulation code is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Dunlap, D. H. & Kenkre, V. M. Dynamic localization of a charged particle moving under the influence of an electric field. Phys. Rev. B 34, 3625 (1986).

Holthaus, M. Collapse of minibands in far-infrared irradiated superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 351 (1992).

Longhi, S. et al. Observation of Dynamic Localization in Periodically Curved Waveguide Arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 243901 (2006).

Lignier, H. et al. Dynamical Control of Matter-Wave Tunneling in Periodic Potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 220403 (2007).

Oka, T. & Aoki, H. Photovoltaic Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 79, 081406(R) (2009).

Mclver, J. W. et al. Light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 38 (2020).

Yin, M. et al. Floquet Engineering Hz-Level Rabi Spectra in Shallow Optical Lattice Clock. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 073603 (2022).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045 (2010).

Qi, X. & Zhang, S. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057 (2011).

Aidelsburger, M. et al. Realization of the Hofstadter Hamiltonian with Ultracold Atoms in Optical Lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185301 (2013).

Miyake, H., Siviloglou, G. A., Kennedy, C. J., Burton, W. C. & Ketterle, W. Realizing the Harper Hamiltonian with Laser-Assisted Tunneling in Optical Lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 185302 (2013).

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a Quantum Hall Effect without Landau Levels: Condensed-Matter Realization of the “Parity Anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015 (1988).

Jotzu, G. et al. Experimental realization of the topological Haldane model with ultracold fermions. Nature 515, 237 (2014).

Rudner, M. S., Lindner, N. H., Berg, E. & Levin, M. Anomalous Edge States and the Bulk-Edge Correspondence for Periodically Driven Two-Dimensional Systems. Phys. Rev. X 3, 031005 (2013).

Zhang, J. Y. et al. Tuning anomalous Floquet topological bands with ultracold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 043201 (2023).

Wintersperger, K. et al. Realization of an anomalous Floquet topological system with ultracold atoms. Nat. Phys. 16, 1058 (2020).

Boyers, E., Crowley, P. J. D., Chandran, A. & Sushkov, A. O. Exploring 2D Synthetic Quantum Hall Physics with a Quasiperiodically Driven Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 160505 (2020).

Malz, D. & Smith, A. Topological Two-Dimensional Floquet Lattice on a Single Superconducting Qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 163602 (2021).

Su, W. P., Schrieffer, J. R. & Heeger, A. J. Soliton excitations in polyacetylene. Phys. Rev. B 22, 2099 (1980).

Zak, J. Berry’s Phase for Energy Bands in Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2747 (1989).

Atala, M. et al. Direct measurement of the Zak phase in topological Bloch bands. Nat. Phys. 9, 795 (2013).

Meier, E. J. et al. Observation of the topological Anderson insulator in disordered atomic wires. Science 362, 929 (2018).

Li, G. et al. Direct extraction of topological Zak phase with the synthetic dimension. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 81 (2023).

Gómez-León, A. & Platero, G. Floquet-Bloch theory and topology in periodically driven lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 200403 (2013).

Wang, D. W., Liu, R. B., Zhu, S. Y. & Scully, M. O. Superradiance lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 043602 (2015).

Chen, L. et al. Experimental observation of one-dimensional superradiance lattices in ultracold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 193601 (2018).

Mi, C. et al. Time-resolved interplay between superradiant and subradiant states in superradiance lattices of Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 104, 043326 (2021).

Xu, X. et al. Floquet superradiance lattices in thermal atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 273603 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Zak Phase Induced Topological Nonreciprocity. arXiv 2409, 17559 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Velocity Scanning Tomography for Room-Temperature Quantum Simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 183403 (2024).

Mao, R. et al. Measuring Zak phase in room-temperature atoms. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 291 (2022).

Scully, M. O., Fry, E. S., Ooi, C. R. & Wódkiewicz, K. Directed spontaneous emission from an extended ensemble of N atoms: Timing is everything. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 040501 (2006).

Scully, M. O. & Svdzinsky, A. A. The super of superradiance. Science 325, 1510 (2009).

He, Y. et al. Geometric Control of Collective Spontaneous Emission. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 213602 (2020).

Dal Lago, V., Atala, M. & Torres, L. E. F. Floquet topological transitions in a driven one-dimensional topological insulator. Phys. Rev. A 92, 023624 (2015).

Lezama, A., Barreiro, S. & Akulshin, A. M. Electromagnetically induced absorption. Phys. Rev. A 59, 4732 (1999).

Zhang, S. et al. Thermal-motion-induced non-reciprocal quantum optical system. Nat. Photon. 12, 744 (2018).

Cai, H. et al. Experimental Observation of Momentum-Space Chiral Edge Currents in Room-Temperature Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 023601 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Flat-Band Localization in Creutz Superradiance Lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 103601 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFA1408900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12325412, 12374335, 11934011, 12434020, 12404573 and U21A20437), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. R25A040015), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (Grant No. 2025C01028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C. and X.X. conceived the project. J.W. and X.X. built the experimental setup, carried out measurement and collected data. J.D. and H.C. did the numerical simulation. H.C. and J.D. formulated the theory. All authors participated in data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Eric Meier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, J., Wang, J., Xu, X. et al. Probing floquet topological phase transition in room-temperature superradiance lattices. Commun Phys 8, 176 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02092-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02092-3