Abstract

The recent discovery of high-transition temperature (Tc) superconductivity in pressurized La3Ni2O7 bulk crystals has attracted keen attention for its characteristic energy diagram of eg orbitals containing nearly half-filled \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) and quarter-filled \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals. This finding provides valuable insights into the orbital contributions and interlayer interactions in double NiO6 octahedrons that further provides a chance to control the electronic structure via varying ligand field. Here, we demonstrate that strain-tuning of the Tc over a range of 50 K with La3Ni2O7 films on different oxide substrates under 20 GPa. As the c/a ratio increases, the onset Tc systematically increases from 10 K in the tensile-strained film on SrTiO3 to the highest value about 60 K in the compressively strained film on LaAlO3. These systematic variations suggest that strain-engineering is a promising approach for expanding the superconductivity in bilayer nickelates with tuning the energy diagram for achieving high-Tc superconductivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent discovery of high-Tc superconductivity near 80 K in pressurized La3Ni2O7 crystals1 has sparked renewed interest in the broader family of nickelate compounds2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. This nickelate belongs to the Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) series (REn+1NinO3n+1, RE = rare-earth element), consisting of bilayer NiO6 octahedra separated by a RE rock-salt layer, with one example being La3Ni2O7 shown in Fig. 1a. Surprisingly, signatures of superconductivity at ambient pressure have been also reported in strained thin films13,14. In a simplified picture of the electronic band structure, Ni 3d orbital adopts a d7.5 electron configuration. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations suggest that the \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbital facilitates significant out-of-plane hopping t⊥ via apical oxygens of the NiO6 octahedra15,16,17. This interlayer interaction causes the \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) bands to split into anti-bonding and bonding states, with the centroid of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) band placed in between (Fig. 1a). In this bilayer Hubbard model, the \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals are nearly half-filled and quarter-filled, respectively, and the strong coupling between the layers through the \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbital is believed to play a critical role for the emergence of high-Tc superconductivity. This bilayer and multi-orbital nature provide a distinct perspective from the high-Tc cuprates, where the single-layer and single-orbital model with nearly half-filled \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital becomes a good description18.

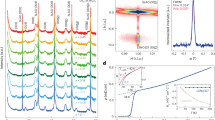

a Crystal structure of bilayer nickelates La3Ni2O7 and the energy diagram of Ni eg orbitals. b Lattice constants of SrTiO3, NdGaO3, and LaAlO3 substrates. c HAADF-STEM cross-sectional image of a La3Ni2O7 thin film grown on NdGaO3 taken along the La3Ni2O7 [110] axis (scale bar 5 nm). Arrow represents the interface. d Reciprocal space maps of La3Ni2O7 (1117)/ LaAlO3 (103) (left) and La3Ni2O7 (1117)/NdGaO3 (103)pc (right). e Experimentally obtained lattice constants of La3Ni2O7 films grown on SrTiO3, NdGaO3, and LaAlO3 substrates. Bulk values are shown in open diamonds1. f Calculations of a-axis length of La3Ni2O7 films on NdGaO3 and LaAlO3 by assumption of bulk compression ratio. Bulk values are plotted with open diamonds1.

In the studies based on bulk crystals, it has been discussed that structural phase transition triggers the superconducting transition at roughly 10–14 GPa (refs. 4,5); an orthorhombic Amam phase at ambient pressure transforms to a tetragonal Fmmm or I4/mmm phase1,5,19, which enhances interlayer coupling essential for the electronic structure preferred for high-Tc superconductivity. Another structural factor is the possible involvement of monolayer and trilayer structural units in contributing to superconductivity20,21,22. Such structural stability or uniformity is largely tied to oxygen deficiencies and the coexistence of competing RP phases (n = 1 and 3), which can hinder the optimization of superconducting properties. Specifically, oxygen vacancies, especially at inner apical oxygen sites, disrupt \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbital hybridization that is crucial for facilitating superconductivity, often inducing insulating behavior instead23,24. To address these issues, concerted efforts in advancement in material synthesis are essential for achieving robust high-Tc superconductivity in this emerging class of nickelates. In this study, we applied a combination of thin-film fabrication technique based on coherent epitaxy and measurement under hydrostatic pressure for strain-tuning of the lattice and electronic structure. Strain tuning of oxide thin films offers large possibility to control the symmetry of octahedron in perovskite structures, resulting in the emergence of fascinating phenomena, for example variation of superconducting properties of cuprates25,26, emergence of ferroelectricity in SrTiO3 (ref. 27) and metal-insulator transition in manganites28. In the structural point of view, the ligand field of octahedra is directly linked to the lattice distortion, which likely provides an opportunity to control the energy diagram of the bilayer nickelates. The intuitive scenario under a compressive situation, with a large c/a ratio elongating the NiO6 octahedra along c-axis, is as follows: the energy separation (ΔE) between \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbitals in the energy diagram shown in Fig. 1a is expected to increase, due to ascending the energy level of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital and lowering the \({d}_{{3}{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbital. Such modifications in the ligand field could effectively tune the electronic band structure and orbital filling, offering a promising route to maximize the superconducting properties in bilayer nickelates.

Results

Epitaxial thin film

We fabricated La3Ni2O7 thin films on three substrates using pulsed-laser deposition (see Methods for details). To tune the strain, we selected SrTiO3 (001) with (aSTO = 3.905 Å), NdGaO3 (001)pc (aNGO = 3.855 Å) and LaAlO3 (001) (aLAO = 3.787 Å) as substrates. While NdGaO3 adopts an orthorhombic Pbnm structure, here we employ a pseudocubic perovskite unit cell for the following discussion. Under ambient pressure, bulk La3Ni2O7 adopts an orthorhombic Amam structure with lattice parameters a = 5.412 Å, b = 5.456 Å, and c = 20.45 Å. This structure can be approximated as a pseudo-tetragonal unit cell with apt = bpt ~ 3.833 Å and c = 20.45 Å. Accordingly, the applicable strain in films is summarized in Fig. 1b. The film on SrTiO3 imposes a tensile strain of +1.9%, NdGaO3 close to the bulk lattice but still introduces a slight tensile strain of +0.6%, and that on LaAlO3 is a compressive strain of –1.2%. Figure 1c shows the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) cross-sectional image of La3Ni2O7 film on NdGaO3 substrate, which exhibits high-quality film with abrupt interface. While additional NiO6 layers were sparsely detected as 3-NiO6 layers, corresponding to approximately 6% off-stoichiometry, the bilayer structural units were predominantly observed, separated by LaO rock-salt layers, corresponding to the 2222-structure (see also Supplementary Information Fig. S1 for an overview and interface).

The crystalline structure was characterized using x-ray diffraction techniques. Judging from no additional peak except for La3Ni2O7 and substrate materials in 2theta-omega scans for three films, a single phase of La3Ni2O7 is fabricated on the substrates (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2). Crucially, we conducted phi-scans around the La3Ni2O7 (2 0 6) peaks to investigate the crystal rotation symmetry. The phi-scans revealed clear four-fold symmetry of the (2 0 6) peaks with 45-degree rotation from the substrate (1 0 1) peaks (see Supplementary Information Fig. S3). This rotation symmetry and appearance of a single peak in reciprocal space mapping (RSM) discussed below strongly suggests that the La3Ni2O7 thin films are stabilized in the tetragonal symmetry owing to epitaxial strain. RSMs were measured around the substrate (1 0 3) peak, as shown in Fig. 1d for LaAlO3 (left) and NdGaO3 (right) (A cross-point of two red broken lines indicates bulk values of La3Ni2O7). In both RSMs, a peak corresponding to La3Ni2O7 (1 1 17) was aligned at substrate along a-axis direction, indicating that the films are almost strained to the in-plane lattice of substrates. The in-plane lattice constant was evaluated to be 3.815 ± 0.014 Å for La3Ni2O7 on LaAlO3 and 3.855 Å for that on NdGaO3, corresponding to –0.5% and +0.6% strains, respectively. Compared with the perfect matching of the film lattice to that of NdGaO3, the strain of the film on LaAlO3 is partially relaxed. The experimentally obtained lattice constants are summarized in Fig. 1e, compared with reported bulk values (open diamonds: La3Ni2O7 bulk crystal under ambient pressure and after structural phase transition at 14 GPa (ref. 1)). The out-of-plane lattice constant correspondingly exhibits elongation on LaAlO3 (c = 20.58 Å) and contraction on NdGaO3 (c = 20.41 Å). Please note that the a-axis value for the film on SrTiO3 is plotted to top axis due to difficulty of experimental evaluation with weak diffraction intensity in RSM measurement. Considering the Poisson’s ratio (ν = 0.5), both films are well-strained in-plane with small variation in the out-of-plane lattices, exhibiting minimal oxygen deficiency.

Based on this lattice condition at ambient pressure, we estimate the lattice distortion under hydrostatic pressure. The compression ratio of tetragonal phase of La3Ni2O7 bulk single crystal around hydrostatic pressure P = 20–40 GPa is approximately –3.22 × 10–3 Å/GPa in pseudo-tetragonal estimation for averaged a,b-axis and –16.6 × 10–3 Å/GPa for c-axis1. Considering the tetragonal lattice unit, hydrostatic pressure compresses the lattice of the La3Ni2O7 crystal almost isotropically. As shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S4, the compression ratio of substrate materials with perovskite structure that was calculated using DFT-based methods (see Methods and Supplementary Information for details) is close values in –(5 ~ 6.5) × 10–3 Å/GPa. By applying –3.22 × 10−3 Å/GPa, we roughly estimate the compressed a-axis length of La3Ni2O7 films as shown in Fig. 1f. When assuming the critical lattice constant for a structural phase transition or the appearance of superconductivity, a higher critical pressure is required to reach it in tensile-strained films with a larger a-axis length. It is also an intriguing viewpoint to compare the critical lattice constant with that for the strained film exhibiting superconductivity at ambient pressure13. In the future, direct measurement of the lattice constant of the films under applied pressure using X-ray diffraction with a diamond anvil cell may become feasible.

Superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 films under hydrostatic pressure

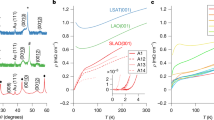

We measured the electrical resistivity of three films under applying hydrostatic pressure up to 20 GPa using a cubic anvil cell with a liquid pressure-transmitting medium. In Fig. 2a, the superconducting transition was clearly observed at P = 20 GPa for the films on three substrates. The onset Tc and the temperature at resistivity reaching zero (Tczero) for the film on LaAlO3 are approximately 60 and 48 K, respectively. The value of Tczero is comparable to the reported bulk values of 40 K (ref. 4) and 41 K (ref. 6). It should be noted that the resistivity of the film on NdGaO3 and LaAlO3 at normal state shows a linear-in-temperature, indicating a strange metal phase. In addition, the onset Tc of the films on NdGaO3 and SrTiO3 decreases to 40 and 10 K, respectively, which is in accord with the increase of the residual resistance. Figure 2b–f exhibit temperature dependent resistivity ρxx (T) of La3Ni2O7 films on SrTiO3 (Fig. 2b), NdGaO3 (Fig. 2c, d), and LaAlO3 (Fig. 2e, f). At P = 0 GPa, while the film on SrTiO3 shows metallic behavior (Fig. 2b), the other two are insulating (Fig. 2c, e). Metallic behavior has been also observed in bulk samples1,5. At low pressure regions roughly below 12 GPa, the insulating behavior is pronounced in all films, which is possibly related to the formation of spin or charge density wave phase as suggested by previous studies on bulk samples23,29,30,31. We also note that local variations of oxygen content in thin film might be close situation as recently reported in bulk samples exhibiting such insulating phases under pressure. We focus on the clear kink of resistivity that correspond to the characteristic temperature for the formation of the density wave phase as TDW, at P = 1 GPa, appears at 170 K for the film on SrTiO3, 175 K for that on NdGaO3, and 150 K for that on LaAlO3. The kink at TDW decreases and becomes broader with increasing pressure, indicating suppression of the density wave phase formation. By further increasing the pressure, all films exhibited metallic ρxx–T curves, resulting in superconducting phase (Fig. 2b, d, f). Current–voltage characteristics were carried out within the current upper limit of 10–4 A. Although finite voltage generation was observed with approximately 10−5 A in low-Tc film on NdGaO3 (see Supplementary Information Fig. S5), the high-Tc film on LaAlO3 would require higher currents than our measurement setup. The large c/a with elongated c-axis and compressed a-axis, that is La3Ni2O7/LaAlO3, stabilizes superconductivity, highlighting the critical role of strain engineering in maximizing superconducting properties.

a Substrate dependence of normalized resistivities as a function of temperature under P = 20 GPa. Resistivities are normalized by values at 280 K. b Resistivities as a function of temperature under various pressure for La3Ni2O7 films on SrTiO3. c Resistivities as a function of temperature under P = 0–8 GPa and d those under P = 12–20 GPa for La3Ni2O7 films on NdGaO3. e Resistivities as a function of temperature under P = 0–12 GPa and f those under P = 16–20 GPa for La3Ni2O7 films on LaAlO3.

Phase diagram

Figure 3a–c presents the temperature–pressure (T–P) phase diagrams of La3Ni2O7 films on three substrates, which was based on the temperature dependence of resistivity shown in Fig. 2. Yellow, purple, and blue represent the metallic, insulating, and superconducting regions, respectively. First, the insulating density wave phase is strongly suppressed in the film on SrTiO3. However, weak insulating behavior appears at below approximately 50 K (purple), resulting in narrow region of superconductivity in the T–P diagram. Second, the superconducting phase appears in close proximity to insulating state, indicating that the suppression of density wave phase is a key to the phase transition. This behavior is reminiscent of features associated with high-Tc superconductivity in cuprates18,32, suggesting a correlation between the insulating and superconducting phases. Third, the superconducting region with the resistance reaching zero appears in the films on NdGaO3 and LaAlO3. The rich phases in the T–P diagrams of three films indicate that the stain effect effectively induces variations in phase stability.

Temperature–Pressure phase diagrams for La3Ni2O7 films on a, SrTiO3, b NdGaO3, and c LaAlO3 substates. TDW (closed triangles) is defined by temperatures that resistivity changes discontinuously. Tczero (close squares) and Tconset (open circles) are defined by temperatures of onset of resistivity drops and zero-resistance.

Strain effect

The strain effect for the electrical properties in three films are discussed with the critical pressure (Pc) for appearance of superconductivity (Fig. 4a), TDW (Fig. 4b), and Tc (Fig. 4c) as a function of c/a. It has been discussed that hydrostatic pressure plays two roles in the appearance of superconductivity in bulk studies1,4,5: one is inducing the structural phase transition, and the other is increasing the hybridization of electronic bands. The strain effect in thin films is significantly different from the isotropic compression under applying hydrostatic pressure, because the increase in the c/a in the film corresponds to the compression of the a-axis length and elongation of the c-axis length, or vice versa. Although the c/a ratio varies in range of approximately 6% in three films, the Pc seems almost constant about 12–16 GPa, being reasonable in comparison with that of bulk values. This result indicates that the structural phase transition is not a major trigger to induce the superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. The degree of hybridization may be a dominant factor in the films. Since no structural phase transition is observed in thin films under strain, while maintaining the tetragonal symmetry, it is plausible that hydrostatic pressure enhances hybridization via compression. Although we did not directly measure the structural evolution or hybridization under hydrostatic pressure in this study, the correlation between strain- and pressure-induced changes and the superconducting phase diagram suggests that hybridization plays an important role. Spectroscopic studies with a diamond anvil cell will provide further physical insight to directly clarify the orbital evolution under pressure.

Two characteristic temperatures TDW at P = 1 GPa and Tc at 20 GPa are summarized in Fig. 4b, c. Comparing the values of the films on NdGaO3 and LaAlO3, a decrease in TDW and an increase in Tc are observed with an increasing the c/a ratio. This suggests that the change in the ligand field and the increase of ΔE is closely related to the stabilization of superconductivity. In contrast, the TDW for SrTiO3 is not on the trend probably due to metallic background conduction. The electron conduction in La3Ni2O7−δ bulks has been reported to undergo a spin-order phase at around 150 K and a charge-order phase at approximately 115 K (refs. 23,24,29,30,31,33,34,35,36). In particular, the role of oxygen deficiencies was discussed on the formation of these density wave phases in previous bulk studies23,29,30,31. Although it is generally difficult to quantitatively analyze oxygen deficiencies in thin films, the effectiveness of ozone annealing to induce metallic behavior and superconductivity have been reported in thin-film samples13,14. Considering the suppression of insulating behavior in the La3Ni2O7 film on LaAlO3 (see Supplementary Information Fig. S7) after ozone annealing, the observed TDW in the as-grown films with tetragonal structure is likely linked to the oxygen deficiencies, which may be as comparable to the reported conditions in both thin films13 and bulk samples19. Based on the good quality of the film, it should be pronounced that the film with large c/a on LaAlO3 show superior superconducting properties with the highest Tczero around 50 K. The systematic increase of Tc demonstrates that the strain tuning enables us to effectively control the ΔE in energy diagram for the emergence of superconductivity.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated the systematic strain tuning of the superconducting transition temperature in La3Ni2O7 thin films based on the coherent epitaxy technique. By applying this approach, we successfully achieved the highest Tczero = 48 K in the compressively strained film on LaAlO3. We found that the critical pressure for superconductivity remains unchanged within this lattice tuning regime. Our results about the lattice engineering in terms of c/a will contribute to construct a unified picture of the superconductivity in bilayer nickelates under isotropic compression by hydrostatic pressure and anisotropic variation by epitaxial strain. Further investigations into strain tuning of RP nickelates are warranted37,38,39,40, particularly for suppressing competing phases, tuning the electronic band structure, and optimizing the superconducting gap, all of which are critical for achieving high-Tc superconductivity.

Methods

Sample preparation

La3Ni2O7 films were fabricated on single-crystalline SrTiO3 (001), NdGaO3 (001)pc, and LaAlO3 (001) substrates using pulsed-laser deposition. La3Ni2O7 polycrystalline targets were ablated by a KrF excimer laser (wavelength 248 nm). Substrates were pre-annealed at 750 °C in an oxygen partial pressure of 1 × 10−6 Torr to obtain an atomically flat surface. During growth, the substrate temperature was fixed at 650°C and the oxygen partial pressure was 200 mTorr. The laser fluence was ~1.0 J/cm2 and a repetition rate was 4 Hz. The film thickness was in a range of 10–20 nm by adjusting the laser pulse counts. The films were characterized using x-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques with Cu Kα source (λ = 1.5406 Å). The interface quality of La3Ni2O7/NdGaO3 (001)pc was examined using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). Crystal structures were visualized using the VESTA software41.

Device for high-pressure measurement

The thin-film samples were cut into dimensions of 500–1000 μm in lateral size, and the substrates were mechanically polished to reduce their thickness to 0.3 mm (see Supplementary Information Fig. S6 for details). Gold wires were bonded to the samples in a van der Pauw geometry using silver paste to ensure reliable electrical contacts. The ρxx-T curves at P = 0 GPa were observed in physical properties measurement system (PPMS) (Quantum Design, Inc.).

High-pressure electric resistivity measurement

The measurements of the temperature dependent resistivity ρxx under high-pressure was performed under various hydrostatic pressure of 1–20 GPa using a cubic anvil cell with a liquid pressure-transmitting medium (see Supplementary Information Fig. S7 for resistivity variation under applied pressure at T = 300 K). The temperature dependence of resistance was measured using Keithley 2182 A nanovoltmeters and Keithley 6221 source meters in delta mode. Measurements were conducted over a temperature range from 292 K to 4.2 K.

Theoretical calculations based on density functional theory

The first-principles DFT calculations for structural optimization are performed using Quantum Espresso42 with a pressure convergence threshold of ±10–3 GPa. The calculations adopt the scalar-relativistic PAW (projector augmented wave) pseudopotentials43 generated by the PSLibrary package44, for which the exchange-correlation potential is treated within the GGA-PBEsol approximation45. The computational parameters are detailed in Supplementary Table S1 where the lattice constants were converged within an error of ±0.002 angstrom for all target materials.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493–498 (2023).

Shilenko, D. A. & Leonov, I. V. Correlated electronic structure, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic correlations in double-layer La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 125105 (2023).

Hou, J. et al. Emergence of high-temperature superconducting phase in pressurized La3Ni2O7 crystals. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 117302 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-temperature superconductivity with zero resistance and strange-metal behaviour in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 20, 1269–1273 (2024).

Wang, N. et al. Bulk high-temperature superconductivity in pressurized tetragonal La2PrNi2O7. Nature 634, 579–584 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in polycrystalline La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. X. 14, 011040 (2024).

Abadi, S. N. et al. Electronic Structure of the Alternating Monolayer-Trilayer Phase of La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 126001 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Electronic and magnetic excitations in La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 9597 (2024).

Cui, T. et al. Strain-mediated phase crossover in Ruddlesden–Popper nickelates. Commun. Mater. 5, 32 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Growth and characterization of the La3Ni2O7−δ thin films: Dominant contribution of the dx2−y2 orbital at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 124801 (2024).

Sakakibara, H. et al. Theoretical analysis on the possibility of superconductivity in the trilayer Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate La4Ni3O10 under pressure and its experimental examination: Comparison with La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144511 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Superconductivity in pressurized trilayer La4Ni3O10−δ single crystals. Nature 631, 531–536 (2024).

Ko, E. K. et al. Signatures of ambient pressure superconductivity in thin film La3Ni2O7. Nature 638, 935–940 (2025).

Zhou, G. et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity onset above 40 K in (La,Pr)3Ni2O7 films. Nature 640, 641–646 (2025).

Nakata, M., Ogura, D., Usui, H. & Kuroki, K. Finite-energy spin fluctuations as a pairing glue in systems with coexisting electron and hole bands. Phys. Rev. B 95, 214509 (2017).

Maier, T. A., Mishra, V., Balduzzi, G. & Scalapino, D. J. Effective pairing interaction in a system with an incipient band. Phys. Rev. B 99, 140504 (2019).

Sakakibara, H., Kitamine, N., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Possible high Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure through manifestation of a nearly half-filled bilayer Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 106002 (2024).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179 (2015).

Dong, Z. et al. Visualization of oxygen vacancies and self-doped ligand holes in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nature 634, 579–584 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Polymorphism in the Ruddlesden–Popper nickelate La3Ni2O7: discovery of a hidden phase with distinctive layer stacking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3640–3645 (2024).

Wang, H., Chen, L., Rutherford, A., Zhou, H. & Xie, W. Long-range structural order in a hidden phase of Ruddlesden-Popper bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Inorg. Chem. 63, 5020–5026 (2024).

Puphal, P. et al. Unconventional crystal structure of the high-pressure superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 146002 (2024).

Taniguchi, S. et al. Transport, magnetic and thermal properties La3Ni2O7−δ. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 64, 1644–1650 (1995).

Sasaki, H. et al. Structural studies on the phase transition of La3Ni2O6.92 at about 550. K. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 66, 1693–1697 (1997).

Takeshita, N., Sasagawa, T., Sugioka, T., Tokura, Y. & Takagi, H. Giantic anisotropic uniaxial pressure effect on superconductivity within the CuO2 Plane of La1.64Eu0.2Sr0.16CuO4: strain control of stripe criticality. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 73, 1123–1126 (2004).

Butko, V. Y. et al. Madelung strain in cuprate superconductors–a route to enhancement of the critical temperature. Adv. Mater. 21, 3644–3648 (2009).

Haeni, J. H. et al. Room-temperature ferroelectricity in strained SrTiO3. Nature 430, 758–768 (2004).

Konishi, Y. et al. Orbital-state-mediated phase-control of manganites. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 68, 3790–3793 (1999).

Dan, Z. et al. Pressure-enhanced spin-density-wave transition in double-layer nickelate La3Ni2O7−δ. Science Bulletin 70, 1239–1245 (2025).

Chen, K. et al. Evidence of spin density waves in La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 256503 (2024).

Meng, Y. et al. Density-wave-like gap evolution in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure revealed by ultrafast optical spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 15, 10408 (2024).

Lee, P. A., Nagaosa, N. & Wen, X. G. Doping a Mott insulator: physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17 (2006).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Transport and magnetic properties La3Ni2O7−δ and La4Ni3O10−δ. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 65, 3978–3982 (1996).

Fukumachi, T., Oda, K., Kobayashi, Y., Miyashita, T. & Sato, M. Studies on successive electronic state changes in systems with NiO2 planes –139La-NMR/NQR–. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 70, 2757–2764 (2001).

Zhang, Z., Greenblatt, M. & Goodenough, J. B. Synthesis, structure, and properties of the layered perovskite La3Ni2O7-δ. J. Solid State Chem. 108, 402–409 (1994).

Xie, T. et al. Strong interlayer magnetic exchange coupling in La3Ni2O7−δ revealed by inelastic neutron scattering. Science Bulletin 69, 3221–3227 (2024).

Wang, M., Wen, H.-H., Wu, T., Yao, D.-X. & Xiang, T. Normal and Superconducting Properties of La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 077402 (2024).

Zhao, Y.-F. & Botana, A. S. Electronic structure of Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates: Strain to mimic the effects of pressure. Phys. Rev. B 111, 115154 (2025).

Huo, Z. et al. Modulation of the octahedral structure and potential superconductivity of La3Ni2O7 through strain engineering. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 68, 237411(2025).

Geisler, B., Hamlin, J. J., Stewart, G. R., Hennig, R. G. & Hirschfeld, P. J. Fermi surface reconstruction in strained La3Ni2O7 on LaAlO3(001) and SrTiO3(001). Preprint at https://arxiv.org/html/2411.14600v1 (2024).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. Vesta 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Dal Corso, A. Pseudopotentials periodic table: from H to Pu. Comput. Mater. Sci. 95, 337 (2014).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Kawasaki with fruitful discussion. STEM observations were made with the cooperation of Y. Kodama and T. Konno of Analytical Research Core for Advanced Materials, Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University. A part of this work was supported by Tohoku University in MEXT Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan (Grant No. JPMXP1224TU0193), Basic Science Research Projects by The Sumitomo Foundation, Toyota Riken Scholar Program by Toyota Physical and Chemical Research Institute, and The Kazuchika Okura Memorial Foundation. Y.N. acknowledges support from MEXT as “Program for Promoting Researches on the Supercomputer Fugaku” (Grant No. JPMXP1020230411), JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. JP23H04869, JP23H04519, and JP23K03307), and JST (Grant No. JPMJPF2221).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O. and A.T. conceived the project. M.O. fabricated and characterized nickelate films. M.O., C.T., A.K., M.N., Y.T., and A.T. performed the high-pressure measurement and analysis. H.-Y.C. and Y.N. conducted theoretical calculation. M.O. and A.T. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osada, M., Terakura, C., Kikkawa, A. et al. Strain-tuning for superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 thin films. Commun Phys 8, 251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02154-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02154-6

This article is cited by

-

Strain-engineered electronic structure and superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 thin films

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2026)

-

Suppression of intertwined density waves in La4Ni3-xCuxO10+δ

npj Quantum Materials (2025)