Abstract

Magnetic nodal-line semiconductors, characterized by colossal magnetoresistance due to the lifting of spin orientation-dependent topological band degeneracy, hold great potential for advanced spintronic applications. However, a key challenge for the practical use of such topological magnets is their low magnetic transition temperature (TC). Through first-principles calculations, we identify the self-intercalated van der Waals ferrimagnet Tc3Si2Te6 as a high-TC (~268 K) magnetic nodal-line semiconductor. Furthermore, we find that magnetic nodal-line semiconductors can exist in dually doped Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 (Y = Ge and Sn; Z = S and Se) over a broad range of α and β. Particularly, Tc3(Si0.05Ge0.95)2(Te0.70Se0.30)6 is shown to be a near room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductor with a sizable band gap. Our findings suggest Tc-based self-intercalated van der Waals ferrimagnets are promising magnetic nodal-line semiconductors for practical applications in spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological magnets, which combine magnetism and nontrivial band topology, provide excellent platforms for the development of low-energy consumption spintronics and dissipationless topological electronics1,2. One prominent example is the Chern insulator, characterized by one-dimensional chiral edge states that carry current without dissipation3. Chern insulators can be realized in various materials, such as thin films of magnetically doped topological insulators4, odd-layer thin films of MnBi2Te45, ferromagnetic (FM) van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures6,7, and two-dimensional metal-organic frameworks8. Other functional categories of topological magnets include axion insulators9,10,11,12,13 featuring a quantized magnetoelectric effect; FM nodal-line semimetals14,15,16, known for their large anomalous Hall current; and magnetic Weyl semimetals17,18,19, also exhibiting giant anomalous Nernst effect. Despite the numerous reported topological magnetic materials2, topological magnets with efficient magnetic control of their electronic conduction are still needed to advance spintronic functionalities20.

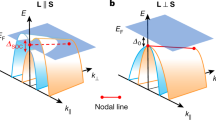

Very recently, a kind of topological magnets, dubbed magnetic nodal-line semiconductors, was theoretically proposed and experimentally confirmed in a self-intercalated vdW ferrimagnet, Mn3Si2Te621. Magnetic nodal-line semiconductors have topological nodal-line band degeneracy protected by their crystal symmetry. When the direction of their magnetization is rotated, their band topology changes, leading to a metal-insulator transition (MIT) and resulting in colossal magnetoresistance (CMR)21. This efficient control of their electronic conduction makes magnetic nodal-line semiconductors highly promising for designing advanced spintronic devices15,21,22,23,24. Furthermore, the anomalous Nernst effect, closely related to the nodal-line band topology, has been suggested by electrical and thermoelectric transport measurements in Mn3Si2Te625. Current-sensitive Hall effect and switchable in-plane anomalous Hall effect have also been reported in the bulk and monolayer of Mn3Si2Te626,27. Despite of these merits, the low magnetic transition temperature (TC) of 78 K in Mn3Si2Te628,29,30 is an obvious bottleneck for practical applications. Although its TC can be increased by applying high pressure, this approach significantly suppresses and eventually eliminates its CMR along with the onset of metallization31,32,33. Therefore, discovering magnetic nodal-line semiconductors with high TC under atmospheric pressure is of great importance for advancing their practical applications.

In this work, we systematically study the electronic and magnetic properties of self-intercalated vdW magnet X3Y2Z6 (X = Mn and Tc; Y = Si, Ge and Sn; Z = S, Se and Te) through first-principles calculations. We first demonstrate that the low TC of Mn-based ferrimagnets originate from their weak Heisenberg exchanges and magnetic frustration. Considering that delocalized 4 d orbitals are beneficial for strong magnetic interactions and that high magnetic transition temperatures have been experimentally reported in SrTcO3 and CaTcO334,35, we focus on Tc-based ferrimagnets and find that Tc3Si2Te6 is a magnetic nodal-line semiconductor with a high TC of 268 K. Moreover, we explore dually doped Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 (Y = Ge and Sn; Z = S and Se) and show that Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 can be magnetic nodal-line semiconductor in a very broad range of α and β. In particular, Tc3(Si0.05Ge0.95)2(Te0.70Se0.30)6 is a room-temperature (TC ~ 298 K) magnetic nodal-line semiconductor with a sizable band gap of 18.8 meV. Our work reveals that Tc-based self-intercalated vdW ferrimagnets offer great opportunities for designing innovative magnetic nodal-line semiconductors for applications.

Results

Crystal and magnetic properties of Tc3Si2Te6

We first examine the crystal structure and magnetic interactions of Mn3Si2Te6 to understand the cause of its low TC. As shown in Fig. 1a, Mn3Si2Te2 is a self-intercalated vdW ferrimagnet with a trigonal space group \(P\bar{3}1c\) (No. 163), in which Mn atoms occupy two different lattice sites30. In the ab plane, Mn1 atoms form honeycomb layers while Mn2 atom form triangular layers (Fig. 1b, c). Along the c-axis, Mn1-honeycomb and Mn2-triangular layers are alternatively stacked. Consistent with previous results30,36,37, our calculations show that the nearest neighbor (NN) J1, second NN J2 and third-NN J3 Heisenberg exchanges are all antiferromagnetic (AFM) couplings, with J1 being dominate (Table S1 of Supplementary Note 3). Due to the AFM J1 and the competition between the AFM J2 and J336, the magnetic ground state of Mn3Si2Te6 is a FiM order (Fig. 1a). The Mn1-honeycomb layer has ferromagnetic (FM) order while J2 between the second-NN Mn1-Mn1 pairs in this layer is AFM. This indicates that the FiM order of Mn3Si2Te6 has a strong magnetic frustration. Overall, the magnetic frustration and relatively weak Heisenberg exchanges are the main driving forces for the low TC of Mn3Si2Te6.

a Side view of the crystal structure. The black rectangle shows the unit cell. The Heisenberg exchange paths are indicated by J1, J2, and J3. The red and blue arrows represent the magnetic moments of magnetic atoms X1 and X2. b Honeycomb layer of X1 atoms. c Triangular layer of X2 atoms. d The first Brillouin zone and its high-symmetry k points and paths.

Obviously, it is vital to relieve the magnetic frustration and enhance Heisenberg exchanges to raise TC. Since Mn1 ions are in a 2+ valence with a 3d5 electronic configuration and paired with edge-sharing MnTe6 octahedra, their Heisenberg exchanges (i.e., J2) are normally AFM, according to the Goodenough-Kanamori rule38. Thus, relieving spin frustration seems unachievable in this system. To find ways of enhancing Heisenberg exchanges, we substitute Si by Ge and Sn, or Te by S and Se. Our calculations show that Mn3Ge2Z6 (Z = Se and Te) and Mn3Sn2Z6 (Z = S, Se and Te) have the desired FiM magnetic ground state (Table S1 of Supplementary Note 3). However, their TCs range from 64 K to 85 K, which is comparable to that of Mn3Si2Te6 and still much lower than room temperature. Therefore, changing the transition metal appears necessary for finding high-TC magnetic nodal-line semiconductors.

Considering that Tc atoms have similar valence and more delocalized 4 d orbitals compared with Mn atoms, we perceive that substituting Mn atoms with Tc atoms could raise the magnetic transition temperature TC, because large wave function overlaps are usually beneficial to enhancing Heisenberg exchanges. In particular, we note that remarkable high AFM transition temperatures (TN) are experimentally reported in Tc-based perovskites SrTcO3 (TN ~ 1023 K)34 and CaTcO3 (TN ~ 800 K)35. Guided by this, we first study the structural and magnetic properties of Tc3Si2Te6 with the same space group as Mn3Si2Te6. The structural details of Tc3Si2Te6 which contains lattice constant and ionic positions is given in Supplementary Note 1. The relaxed lattice constants of Tc3Si2Te6 are a = b = 7.21 Å and c = 14.47 Å, which are larger than those of Mn3Si2Te6 (a = b = 7.04 Å, c = 14.26 Å) since Tc atoms have a bigger radius than Mn atoms. To examine the thermodynamic stability of Tc3Si2Te6, we calculate its phonon spectrum and conduct ab initio molecular dynamics simulations at 300 K. As shown in Fig. 2a, there is no imaginary frequency in the phonon spectrum of Tc3Si2Te6, indicating that it is dynamical stable. In addition, the evolutions of the total energy and temperature in ab initio molecular dynamics simulations suggest the thermal stability of Tc3Si2Te6 (see Fig. S4 in Supplementary Note 5). Consistent with the high-spin state of the Tc 4d5 configuration in a Te-formed octahedron field, our calculations show that the magnetic moments of Tc1 and Tc2 are 4.2 and 4.0 μB, respectively. By comparing total energies of the four representative magnetic orders (i.e., FiM, AFM1, AFM2, and FM)36, it turns out that the magnetic ground state of Tc3Si2Te6 is FiM order (see Fig. S5 in Supplementary Note 5), confirming that Tc3Si2Te6 is a thermodynamically stable ferrimagnet.

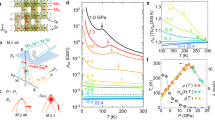

a Phonon spectrum. b Electronic band structure without spin-orbit coupling (SOC), with energies referenced to the Fermi level (EF). Spin-up and spin-down states are indicated by blue and red colors, respectively. c Projected density of state (DOS) for Tc1, Tc2, Te and Si atoms. d Electronic band structure with SOC when the magnetization (M) is aligned along the a-axis. e same as (d) but for magnetization is aligned along the c-axis. f Evolution of the band gap of the FiM order as a function of angle \(\theta\) away from the a-axis.

To determine the magnetic transition temperature TC of Tc3Si2Te6, we employ a spin Hamiltonian

in which Jij is the Heisenberg exchange interactions parameter and K is a single ion anisotropy constant. A negative (positive) Jij means a FM (AFM) interaction. To obtain reliable results for TC, we consider Heisenberg exchanges up to the ninth near neighbor (see Fig. S1 in Supplementary Note 2). As a benchmark, our calculations based on this approach show that the TC of Mn3Si2Te6 is 87 K, consistent with the experimental data (78 K)21,30. From the magnetic parameters listed in Table S2 of Supplementary Note 6, we see that the Heisenberg exchange interactions and single ion anisotropy of Tc3Si2Te6 are noticeably larger than those of Mn3Si2Te6. As discussed in Fig. S6 of Supplementary Note 6, the enhanced Heisenberg exchange interactions and single ion anisotropy of Tc3Si2Te6 originate mainly from the more extended wavefunction overlap of Tc-4d orbitals compared with the localized Mn-3d orbitals in Mn3Si2Te6. Similar to Mn3Si2Te6, the dominant Heisenberg exchange interactions are J1, J2, and J3, all of which are AFM. Based on these parameters, our Monte Carlo simulations show that the magnetic ground state of Tc3Si2Te6 is the desired FiM order and its TC as high as 268 K. This significant increase in TC brings it much closer to the room temperature range compared to Mn3Si2Te6. Note that due to its three-dimensional nature, the large magnetic anisotropy in Tc3Si2Te6 bulk plays a weak role in determining its high TC (see Fig. S7 in Supplementary Note 6).

Electronic and topological properties of Tc3Si2Te6

We now investigate the electronic properties of Tc3Si2Te6. Fig. 2b, c show its band structure and density of states (DOSs) when spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is not considered. Our calculations show that the band gaps of spin-up and spin-down bands are 507.2 and 185.0 meV, respectively. Taking spin-up and spin-down states together, Tc3Si2Te6 has an indirect band gap (~25.3 meV). It is worth noting that there is a two-fold degenerate nodal line along the ΓA line that is protected by the C3v point group symmetry of Tc3Si2Te6 (see Fig. 2b and Fig. S8a). From the projected DOSs as shown in Fig. 2c, we see that the valence band maximum at the Γ point mainly originates from the states of Te atoms while the conduction band minimum at the K point is mainly from the states of Tc atoms.

Given the strong SOC of Te atoms and the narrow band gap, it is crucial to explore how SOC influence the electronic properties of Tc3Si2Te6. Figure 2d, e show the band structures of Tc3Si2Te6, considering SOC in DFT calculations, with its magnetization orientated along different axes. With magnetization along the a-axis, Tc3Si2Te6 is insulating with a band gap of 18.2 meV. In contrast, Tc3Si2Te6 transitions to a metallic state when its magnetization is aligned along the c-axis. This metal-insulator transition is also unambiguously demonstrated by our HSE06 hybrid functional calculations (see Fig. S3a, b in Supplementary Note 4). The previously two-fold degenerate nodal line along the ΓA line splits into two non-degenerate bands which exhibit sizable Berry curvatures (see Fig. S8b, e in Supplementary Note 6). Following ref. 21, the splitting of the nodal line at the Γ point is defined as the SOC gap, \({\it{\varDelta }}_{{{{\rm{SOC}}}}}\). As shown in Fig. 2e, the value of \({\it{\varDelta }}_{{{{\rm{SOC}}}}}\) is as large as 351.3 meV, which is compared to that (i.e., 332.9 meV) obtained from HSE06 hybrid functional calculations. These findings highlight several unique properties of the material: I) a MIT takes place in Tc3Si2Te6 when its magnetization is rotated from the a-axis to the c-axis; II) the MIT is caused by the SOC-induced band splitting of the two-fold degenerate nodal line. Hence, Tc3Si2Te6 is identified as a high-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductor.

To gain deeper insight into the magnetization rotation-induced MIT of Tc3Si2Te6, we study the evolution of its band gap as a function of magnetization rotation angle, θ, away from the a-axis to the c-axis (see the inset in Fig. 2f). As shown in Fig. 2f, the band gap first decreases linearly and then remains zero as θ increases from 0° to 90°. Especially, Tc3Si2Te6 enters into the metallic phase at a critical \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) = 7°. This small critical \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) for magnetization rotation, which induces a MIT, indicates that it is very feasible to achieve a sensitive CMR effect in Tc3Si2Te6 by applying a small external magnetic field.

Near room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors in dually doped Tc3(Si1-α Y α)2(Te1-β Z β)6

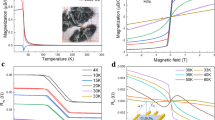

To further increase the TC of Tc3Si2Te6 while retaining its characteristics as a magnetic nodal-line semiconductor, we explore a series of Tc3Y2Z6 (Y = Si, Ge and Sn; Z = S, Se, and Te). Our calculations indicate that Tc3Sn2Se6, Tc3Sn2Te6 and Tc3Ge2Te6 are ferrimagnets with TC values of 207, 277, and 341 K (Fig. 3a), respectively. The non-monotonic trend of TCs across the Si/Ge/Sn arises from the competition between the lattice-expansion induced weakening of the short-range AFM interactions and the emergence of long-range Ruderman-Kittel-Kasuya-Yosida FM couplings in metallic magnets39,40,41 (Table S2 of Supplementary Note 6). Phonon and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations indicate their thermodynamic stability (see Fig. S4 in Supplementary Note 5). By examining their band structures with their magnetizations along the a and c axes (Fig. S9 of Supplementary Note 6), we find that Tc3Sn2Te6 and Tc3Ge2Te6 are metallic, while Tc3Sn2Se6 is a semiconductor (Fig. 3b). However, no MIT occurs in these three ferrimagnets. The band gaps of Tc3Sn2Se6 are 191 meV to 134 meV when its magnetization is along the a and c axes, respectively. As this decrease in the band gap is related to a large \({\it{\varDelta }}_{{\rm{SOC}}}\) (~130 meV) (Fig. 3c), the magnetoresistance effect should be observable in Tc3Sn2Se6.

We observe that Tc3Si2Te6 is a magnetic nodal-line semiconductor with TC below room temperature while Tc3Ge2Te6 is a FiM metal with a TC above room temperature. Therefore, doping Ge into Tc3Si2Te6 may increase TC. However, this doping may also decrease its band gap and, potentially leading to the disappearance of its MIT. Besides, \({\it{\varDelta }}_{{\rm{SOC}}}\) of Tc-based self-intercalated vdW ferrimagnets increases when their chalcogen atoms change from S to Se and to Te (see Fig. 3c and Fig. S10). Given that the MIT of Tc3Si2Te6 is closely related to \({\it{\varDelta }}_{{\rm{SOC}}}\), doping other chalcogen atoms into it may also significantly affect its band gap. We thus propose dual doping of Tc3Si2Te6 with Ge (or Sn) and S (or Se) to achieve room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors. For convenience, we denote the dually doped Tc3Si2Te6 as Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 (Y = Ge and Sn; Z = S and Se). Note that dual doping has been widely used to enhance the performance of various materials, such as transition metal oxide42, nickel selenide43 and hollow carbon spheres44.

We investigate the effect of dual doping on the lattice geometry of Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 to demonstrate the applicability of virtual crystal approximation. As expected, the relaxed Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 has a similar structure and the same space group as Tc3Si2Te6. As shown in Fig. S11 of Supplementary Note 7, as the atomic radius of S (or Se) atom is obviously smaller than Te atom, the in-plane lattice constant (i.e., a or b) decreases significantly with the increment of doping level of S (or Se). On the contrary, in the case of doping Ge (or Sn) into Si site, the in-plane lattice constant shows opposite behavior with a slow increasing trend. Especially, our calculations show that the in-plane lattice constant basically displays a linear relationship with doping components, which is consistent with the Vegard’s law45. Therefore, it is reliable to use virtual crystal approximation to study dual doping in Tc3Si2Te6.

To efficiently screen the FiM nodal-line semiconductor phase in Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6, we first calculate the energies of FiM, AFM1, AFM2, and FM orders. As shown in Fig. S12b, d of Supplementary Note 7, the FiM order has the lowest energy when both α and β are in the range of 0 to 1 in Tc3(Si1-αGeα)2(Te1-βSeβ)6 and Tc3(Si1-αSnα)2(Te1-βSeβ)6. In contrast, Tc3(Si1-αGeα)2(Te1-βSβ)6 and Tc3(Si1-αSnα)2(Te1-βSβ)6 have magnetic ground states of FiM orders depending on the combination of α and β (see Fig. S12a, c in Supplementary Note 7). Because magnetization rotation induced MIT is the essential feature of magnetic nodal-line semiconductors, we study the band structures of the FiM orders in Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 to identify this characteristic. Our calculations demonstrate that the magnetization rotation-induced MIT appears when Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 has a suitable combination of α and β (see the colorful areas in Fig. 4a, c, e, g). It is worth noting that the combination range of α and β for the magnetic nodal-line semiconductor phase in Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 is quite wide, providing excellent tunability for achieving desired magnetic nodal-line semiconductors. When α and β are outside this combination range, Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 is either a FiM insulator or FiM metal, regardless of its magnetization being along the a- or c-axes.

a The white, colorful and black areas show the Ferrimagnetic (FiM) insulator, magnetic nodal-line semiconductor (MNLS) and FiM metal phases of the FiM Tc3(Si1-αGeα)2(Te1-βSβ)6 in the α-β plane, respectively. The color bar indicates band gaps of the insulating phase of the magnetic nodal-line semiconductors. b The correlation between TC and band gaps when the magnetizations of selected FiM Tc3(Si1-αGeα)2(Te1-βSβ)6 are long the a-axis. The red stars highlight near room-temperature magnetic semiconductors with reasonably large band gaps. c–h same as (a, b) but for Tc3(Si1-αGeα)2(Te1-βSeβ)6, Tc3(Si1-αSnα)2(Te1-βSβ)6, and Tc3(Si1-αSnα)2(Te1-βSeβ)6, respectively.

Finally, it is important to examine if Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 with the optimal combinations of α and β has a TC above room-temperature. As shown in Fig. 4a, c, e, g, as the TC of Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 increases from 210 K to room temperature, the band gap in its insulating phase decreases from more than 100 meV to less than 26 meV. For instance, Tc3(Si0.05Ge0.95)2(Te0.70Se0.30)6 is a magnetic nodal-line semiconductor, with a TC of 298 K and a band gap of 18.8 meV, both of which are suitable for applications. Several other combinations are also highlighted by the red stars in Fig. 4b, d, f, h as potential high temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors, and their TC values and band gaps are shown in Fig. S13 and Table S3 of Supplementary Note 8. The wide tunability of dual doping in Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 makes it highly feasible to realize room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors, and these potential warrants future experimental exploration.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we systematically studied the magnetic and electronic properties of the self-intercalated vdW magnet X3Y2Z6 (X = Mn and Tc; Y = Si, Ge, and Sn; Z = S, Se, and Te) through first-principles calculations. We showed that the weak Heisenberg exchange interactions and magnetic frustration in Mn-based ferrimagnets are the main causes for their TC. We found that Tc3Si2Te6 is magnetic nodal-line semiconductor with a high TC of 268 K and a large gap of 18.2 meV, with its MIT potentially controllable by a small external magnetic field in experiments. As a further step, we shown that near room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors with sizable band gaps can be realized in dually doped Tc3(Si1-αYα)2(Te1-βZβ)6 (Y = Ge and Sn; Z = S and Se). Our work provides a feasible strategy to achieve room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors in Tc-based self-intercalated vdW ferrimagnets and opens possibilities for the practical applications of magnetic nodal-line semiconductors in spintronics.

Methods

Density functional theory computations

Our first-principles calculations based on the density-functional theory (DFT) are carried out with the Vienna ab initio simulation package46. Projector augmented wave method and the generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof potential47 are used in our calculations. We utilize an energy cutoff of 350 eV for the plane-wave expansion and fully relax the lattice constants and atomic positions until the force acting on each atom is smaller than 0.01 eV/Å. To describe the strong correlation effect among d electrons, Ueff = 2.0 eV and Ueff = 3.2 eV are adopted for Mn and Tc atoms48, respectively. The magnetic properties of Tc3Si2Te6 are investigated using different Ueff values, and it is found that its high-temperature FiM order is robust when Ueff is in the reasonable and widely used range from 2.0 to 4.0 eV49,50,51,52 (see Fig. S2 in Supplementary Note 4). Furthermore, the band structure obtained from HSE06 hybrid functional calculations53 is consistent with the one obtained by DFT + Ueff (Ueff = 3.2 eV), demonstrating the validity of Ueff = 3.2 eV for Tc-based systems (see Fig. S3 in Supplementary Note 4). Phonon spectra are calculated with the finite displacement method54. The ab initio molecular dynamics simulations with a temperature of 300 K are performed for 5 ps. Based on the magnetic parameters obtained from DFT calculations, we perform Monte Carlo (MC) simulations55,56 using the Metropolis algorithm to explore magnetic ground states and critical temperatures. To simulate the dual doping effect on the electronic and magnetic properties of Si3Tc2Te6, we employ the widely used virtual crystal approximation57. Here, in order to correctly describe the mixing of pseudopotentials with homo-valent atoms in virtual crystal approximation, the valance electronic configurations are adopted as Si3s23p2, Ge4s24p2, Sn5s25p2 and S3s23p4, Se4s24p4, Te5s25p4.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tokura, Y., Yasuda, K. & Tsukazaki, A. Magnetic topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 126–143 (2019).

Bernevig, B. A., Felser, C. & Beidenkopf, H. Progress and prospects in magnetic topological materials. Nature 603, 41–51 (2022).

Chang, C.-Z., Liu, C.-X. & MacDonald, A. H. Colloquium: quantum anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 011002 (2023).

Chang, C.-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Deng, Y. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Science 367, 895–900 (2020).

Hou, Y., Kim, J. & Wu, R. Magnetizing topological surface states of Bi2Se3 with a CrI3 monolayer. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw1874 (2019).

Xue, F. et al. Tunable quantum anomalous hall effects in ferromagnetic van der Waals heterostructures. Natl. Sci. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwad151 (2023).

Chen, C.-Q., Ni, X.-S., Yao, D.-X. & Hou, Y. Chern insulators and high Curie temperature Dirac half-metal in two-dimensional metal-organic frameworks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0122120 (2022).

Qi, X.-L., Hughes, T. L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological field theory of time-reversal invariant insulators. Phys. Rev. B 78, 195424 (2008).

Hou, Y. & Wu, R. Axion insulator state in a ferromagnet/topological insulator/antiferromagnet heterostructure. Nano Lett. 19, 2472–2477 (2019).

Hou, Y. S., Kim, J. W. & Wu, R. Q. Axion insulator state in ferromagnetically ordered CrI3/Bi2Se3/MnBi2Se4 heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 101, 121401 (2020).

Xiao, D. et al. Realization of the axion insulator state in quantum anomalous Hall sandwich heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 056801 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Robust axion insulator and Chern insulator phases in a two-dimensional antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nat. Mater. 19, 522–527 (2020).

Kim, K. et al. Large anomalous Hall current induced by topological nodal lines in a ferromagnetic van der Waals semimetal. Nat. Mater. 17, 794–799 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Control of chiral orbital currents in a colossal magnetoresistance material. Nature 611, 467–472 (2022).

Singh, S. et al. Anisotropic nodal‐line‐derived large anomalous Hall conductivity in ZrMnP and HfMnP. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104126 (2021).

Sakai, A. et al. Giant anomalous Nernst effect and quantum-critical scaling in a ferromagnetic semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1119–1124 (2018).

Roychowdhury, S. et al. Anomalous Hall conductivity and Nernst effect of the ideal Weyl semimetallic ferromagnet EuCd2As2. Adv. Sci. 10, 2207121 (2023).

Noguchi, S. et al. Bipolarity of large anomalous Nernst effect in Weyl magnet-based alloy films. Nat. Phys. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02293-z (2024).

Žutić, I., Fabian, J. & Das Sarma, S. Spintronics: fundamentals and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 323–410 (2004).

Seo, J. et al. Colossal angular magnetoresistance in ferrimagnetic nodal-line semiconductors. Nature 599, 576–581 (2021).

Ni, Y. et al. Colossal magnetoresistance via avoiding fully polarized magnetization in the ferrimagnetic insulator Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 103, L161105 (2021).

Tan, C. et al. Electrically tunable, rapid spin–orbit torque induced modulation of colossal magnetoresistance in Mn3Si2Te6 nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 24, 4158–4164 (2024).

Ye, F. et al. Magnetic structure and spin fluctuations in the colossal magnetoresistance ferrimagnet Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 106, L180402 (2022).

Ran, C. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect and topological Nernst effect in the ferrimagnetic nodal-line semiconductor Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 108, 125103 (2023).

Li, D., Wang, M., Li, D. & Zhou, J. Switchable in-plane anomalous Hall effect by magnetization orientation in monolayer Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 109, 155153 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Current-sensitive Hall effect in a chiral-orbital-current state. Nat. Commun. 15, 3579 (2024).

Rimet, R., Schlenker, C. & Vincent, H. A new semiconducting ferrimagnet: a silicon manganese telluride. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 25, 7–10 (1981).

Vincent, H., Leroux, D., Bijaoui, D., Rimet, R. & Schlenker, C. Crystal structure of Mn3Si2Te6. J. Solid State Chem. 63, 349–352 (1986).

May, A. F. et al. Magnetic order and interactions in ferrimagnetic Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 95, 174440 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Pressure engineering of colossal magnetoresistance in the ferrimagnetic nodal-line semiconductor Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 106, 045106 (2022).

Susilo, R. A. et al. High-temperature concomitant metal-insulator and spin-reorientation transitions in a compressed nodal-line ferrimagnet Mn3Si2Te6. Nat. Commun. 15, 3998 (2024).

Huang, C. et al. Tuning the colossal magnetoresistance in (Mn1-x Mgx)3Si2Te6 by engineering the gap and magnetic properties via doping and pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 205145 (2024).

Rodriguez, E. E. et al. High temperature magnetic ordering in the 4d perovskite SrTcO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 067201 (2011).

Avdeev, M. et al. Antiferromagnetism in a technetium oxide. Structure of CaTcO3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1654–1657 (2011).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, magnetic properties, spin orientation, and doping effect in Mn3Si2Te6. Phys. Rev. B 107, 054430 (2023).

Kwon, C. I. et al. Raman signatures of spin-phonon coupling in a self-intercalated van der Waals magnet Mn3Si2Te6. Curr. Appl Phys. 53, 51–55 (2023).

Goodenough, J. B. Goodenough-Kanamori rule. Scholarpedia 3, 7382 (2008).

Ruderman, M. A. & Kittel, C. Indirect exchange coupling of nuclear magnetic moments by conduction electrons. Phys. Rev. 96, 99–102 (1954).

Kasuya, T. A theory of metallic ferro- and antiferromagnetism on Zener’s model. Prog. Theor. Phys. 16, 45–57 (1956).

Yosida, K. Magnetic properties of Cu-Mn alloys. Phys. Rev. 106, 893–898 (1957).

Ling, T. et al. Well-dispersed nickel-and zinc-tailored electronic structure of a transition metal oxide for highly active alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807771 (2019).

Chang, J. et al. Dual‐doping and synergism toward high‐performance seawater electrolysis. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101425 (2021).

Gao, J. et al. Engineering electronic transfer dynamics and ion adsorption capability in dual-doped carbon for high-energy potassium ion hybrid capacitors. ACS Nano 16, 6255–6265 (2022).

Denton, A. R. & Ashcroft, N. W. Vegard’s law. Phys. Rev. A 43, 3161–3164 (1991).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Mravlje, J., Aichhorn, M. & Georges, A. Origin of the high Néel temperature in SrTcO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 197202 (2012).

Siska, E. et al. β-technetium: an allotrope with a nonstandard volume-pressure relationship. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 063603 (2021).

Siska, E. et al. Synthesis and chemical stability of technetium nitrides. Chem. Commun. 57, 8079–8082 (2021).

Tesch, R. & Kowalski, P. M. Hubbard U parameters for transition metals from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 105, 195153 (2022).

Krukau, A. V., Vydrov, O. A., Izmaylov, A. F. & Scuseria, G. E. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 125. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2404663 (2006).

Kresse, G., Furthmüller, J. & Hafner, J. Ab initio force constant approach to phonon dispersion relations of diamond and graphite. Europhys. Lett. 32, 729 (1995).

Hukushima, K. & Nemoto, K. Exchange Monte Carlo method and application to spin glass simulations. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 65, 1604–1608 (1996).

Lou, F. et al. PASP: property analysis and simulation package for materials. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 114103 (2021).

Bellaiche, L. & Vanderbilt, D. Virtual crystal approximation revisited: application to dielectric and piezoelectric properties of perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 61, 7877–7882 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFA1408303, 2022YFA1403301, 2022YFA1402802, 2018YFA0306001) and the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (Grants No. 12474247, 92165204) and Shenzhen International Quantum Academy. DFT calculations are performed on Tianhe-II. Ruqian Wu acknowledges support from the USA-DOE, Office of Basic Energy Science (Grant No. DE-FG02-05ER46237). Yusheng Hou acknowledgments the support from Research Center for Magnetoelectric Physics of Guangdong Province (Grants 2024B0303390001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. H. conceived the idea and supervised the project. J. L. performed DFT calculations. J. L. analyzed the data with the help of X. N., D. Y., and R. W. J. L., L. Z., D. Y., R. W., and Y. H. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Panchapakesan Ganesh and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Jw., Ni, XS., Zhuang, L. et al. Near room-temperature magnetic nodal-line semiconductors in technetium-based self-intercalated van der Waals ferrimagnets. Commun Phys 8, 382 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02185-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02185-z