Abstract

High-order phenomena are pervasive across complex systems, yet their formal characterisation remains a formidable challenge. The literature provides various information-theoretic quantities that capture high-order interdependencies, but their conceptual foundations and mutual relationships are not well understood. The lack of unifying principles underpinning these quantities impedes a principled selection of appropriate analytical tools for guiding applications. Here we introduce entropic conjugation as a formal principle to investigate the space of possible high-order measures, which clarifies the nature of the existent high-order measures while revealing gaps in the literature. Additionally, entropic conjugation leads to notions of symmetry and skew-symmetry which serve as key indicators ensuring a balanced account of high-order interdependencies. Our analyses highlight the O-information as the unique skew-symmetric measure whose estimation cost scales linearly with system size, which spontaneously emerges as a natural axis of variation among high-order quantities in real-world and simulated systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physical and biological systems often exhibit relationships between their parts that cannot be reduced to dependencies in subsets of them1. The study of these high-order interdependencies has led to new insights in a wide range of physical systems2,3,4, as well as in studies involving genetics5,6 and neural systems (both biological7,8,9,10,11 and artificial12,13,14), to name a few. Overall, qualitatively different types of interdependence have been found to play complementary roles balancing needs for robustness and flexibility15,16.

There are different approaches to quantify high-order phenomena17, among which we focus on information-theoretic quantities based on Shannon entropy. While there is a rich literature offering various high-order information measures, their interpretation is highly non-trivial—being unclear whether these quantities are capturing the same effects or instead provide complementary perspectives. This lack of clarity makes it challenging for researchers to choose the right tools to carry out specific types of analyses, severely hindering the potential of these measures for practical analyses. Here we address this issue by introducing entropic conjugation as a theoretically grounded principle for exploring the space of possible high-order information measures. Entropic conjugation allows us to show that the existent high-order measures have a closer relationship than previously thought, while revealing gaps in the literature related to high-order interdependencies involving more than five variables. Moreover, our results show how the notions of symmetry and skew-symmetry with respect to entropic conjugation serve as critical indicators ensuring a balanced characterisation of high-order interdependence, which is key to provide a faithful delineation of the high-order profile of physical systems of interest. Our results establish that the O-information occupies a privileged position as the unique skew-symmetric measure whose computational complexity scales linearly with system size. Numerical investigations further reveal that the O-information provides a natural axis of variation among high-order quantities, highlighting its fundamental role in the information-theoretic characterisation of complex systems. The proofs of our results are included in the Methods section.

Results

Measures of multivariate interdependence

Consider a system whose state is specified by the random vector X = (X1, …, Xn) following a joint distribution pX and marginal distributions \({p}_{{X}_{i}}\). The literature presents various approaches to assess the dependencies between parts of X; here we focus on linear combinations of entropies of the form

where In = {1, …, n}, Xa is the vector of variables whose indices are in a ⊆ In, H(Xa) is the Shannon entropy of Xa, and λa are scalars. In order to focus on metrics of interdependence, we further require these quantities to satisfy two key properties:

-

(i)

Labelling-symmetry: ϕ(X) should be invariant to permutations among X1, …, Xn.

-

(ii)

Dependency: ϕ(X) = 0 if the variables are jointly independent (i.e., if \({p}_{{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}={\prod }_{k = 1}^{n}{p}_{{X}_{k}}\)).

In this way, property (i) guarantees that ϕ does not depend on how variables are named, and (ii) that it only captures effects of interactions between variables. There are multiple ‘directed’ high-order quantities that distinguish between predictor and target variables, which don’t satisfy labelling-symmetry18,19,20. These quantities will be studied in a follow-up work using a formalism that extends the one presented here.

There are several well-known quantities that satisfy these properties. The oldest of these is the interaction information21, which is defined as

Other metrics of interdependence are the total correlation (TC)22 and the dual total correlation (DTC)23, which are given by

where H(Xj∣X−a) is the conditional entropy and − a denotes the set of indices of X that are not in a. Another such metric, well-known in computational neuroscience, is the Tononi-Sporns-Edelman complexity24, which is defined as

where I(Xa; X−a) is Shannon’s mutual information. Finally, we also consider the more recently introduced O-information and S-information25:

Of these, TC, DTC, TSE, and Σ are non-negative, while II and Ω can take positive and negative values. In the following we show how these seemingly unrelated metrics can be parsimoniously unified under the concept of entropic conjugation.

Characterising high-order interdependencies

We introduce two complementary approaches to assess high-order interdependencies.

The first approach comes from harnessing algebraic properties of linear combinations of entropies, as introduced in ref. 26. To explain this, let us first note that the quantities ϕ described by Eq. (1) form a vector space. Within this space, the condition of labelling-symmetry is satisfied only on an n-dimensional subspace spanned by the quantities

Informally, rk describes the average amount of information in groups of k variables, with rn = H(X), \({r}_{1}=1/n{\sum }_{j = 1}^{n}H({X}_{j})\), and r0 = 0. Further imposing the condition of dependency adds one linear constraint, reducing this subspace by one dimension. The resulting (n − 1)-dimensional subspace of metrics satisfying both labelling-symmetry and dependency can be shown to be spanned by the negative discrete Laplacian of the above quantities26:

which can also be expressed as averages of conditional mutual informations of the form

Moreover, it can be seen that each uk captures a specific order of interdependencies. To see this, let’s define

so that \(p({{{\boldsymbol{x}}}})\in {C}_{{X}_{i},{X}_{j},{{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}}\) if and only if I(Xi; Xj∣Xa) = 0. Furthermore, define

which corresponds to distributions without interdependencies of order k. Then, it is direct to see that

This implies, for instance, that if uk(X) = 0 for k = 1, …, j, then all subsets of j variables or less are statistically independent. Following this rationale, it can be shown that the set {u1, …, un−1} is the unique basis of the space of linear combinations of entropies satisfying labelling-symmetry and dependency that guarantees that, if \(\phi ={\sum }_{k = 1}^{n-1}{c}_{k}{u}_{k}\), then ϕ is non-negative if and only if ck ≥ 0 for k = 1, …, n − 126. In this sense, the resulting coefficient ck can be interpreted as capturing the relevance of (k + 1)-th order dependencies on ϕ.

A complementary and more fine-grained way of investigating high-order interdependence is enabled by partial information decomposition (PID)27, which addresses how information about a variable Y provided by X may be decomposed into the contributions of its different components28,29. PID reveals that while pairwise interdependence is quantified by its strength (measured e.g. by the mutual information), higher-order relationships can be of qualitatively different kinds—most notably redundant (multiple variables sharing the same information) or synergistic (a set of variables holding some information that cannot be seen from any subset). Moreover, PID recognises that synergy and redundancy can be mixed in non-trivial ways, and explores this thoroughly via a formal construction that leads to the decomposition

where \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{n}\) is a collection of elements α that cover all possible combinations of redundancy and synergy (see subsection PID conjugation in Methods). For example, if n = 2 then \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{2}\) has four elements: α1 = {{1}{2}} corresponding to the redundancy between X1 and X2, α2 = {{1, 2}} corresponding to the synergy between them, and α3 = {{1}} and α4 = {{2}} corresponding to unique information in one but not the other. While outlining the relations between the different modes of interdependency, the PID framework itself does not prescribe a specific functional form to calculate these quantities — which has given rise to numerous proposals of how to best define these measures (see e.g. refs. 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40). More technical details about PID can be found in the subsection PID conjugation in Methods.

A conjugation for Shannon quantities

The notion of ‘conjugation’ is pervasive in mathematics, with examples including the conjugate of a complex number turning z = a + ib into z* = a − ib, and the conjugation of matrices turning a matrix A with entries aij into its Hermitian transpose A* with entries \({a}_{ji}^{* }\). Formally, these examples of conjugation are linear involutions — i.e., linear operations that bring back the original element when applied twice. We now introduce one such conjugation for linear combinations of entropies.

Definition 1

The entropic conjugation is defined as

with the conjugation of a linear combination of entropies \(\phi ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})={\sum}_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}\subseteq {I}_{n}}{\lambda }_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}})\) being given by

It can be seen that * is linear (by definition) and an involution, as \({({(H)}^{* })}^{* }=H\). Among the possible linear involutions (see the subsection Linear involutions of entropies in Methods), entropy conjugation has special properties related to high-order interdependencies which are outlined by our next results.

Lemma 1

Entropic conjugation acts on the mutual information as

where a, b, c are disjoint subsets of indices. Furthermore, Eq. (16) is equivalent to Def. 1.

The way in which entropic conjugation acts on the mutual information suggests that this operation turns low- into high-order interdependencies: for example, if a = {i}, b = {j}, and \({{{\boldsymbol{c}}}}=\varnothing\), then Lemma 1 states that \({(I({X}_{i};{X}_{j}))}^{* }=I({X}_{i};{X}_{j}| {{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{-\{i,j\}})\), turning a quantity that depends on the pairwise marginal p(xi, xj) into one that depends on the full distribution p(x). This observation can be generalised, setting the foundations for our analysis of high-order quantities in the next section.

Proposition 1

Entropic conjugation exchanges high- for low-order interdependencies in the following way:

A deeper insight on the effect of entropic conjugation can be attained by looking at it via the PID framework. Our next result shows that entropic conjugation is the unique operation that arises from applying the duality principle from order theory41 and category theory42 to PID, which results in a natural conjugation of atoms † that exchanges redundancies for synergies and vice-versa. For example, if α = {{1, 2}} then α† = {{1}, {2}}. For technical details about the conjugation of PID atoms, see the subsection PID conjugation in Methods.

Theorem 1

The natural conjugation of PID atoms † arising from the duality principle satisfies

where \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}}\) is a collection of atoms such that \(I({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}}| {{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}})={\sum}_{{{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}}\in {{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}}}{I}_{\partial }^{{{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) (see Lemma 3).

Crucially, this result holds for any operationalisation of synergy and redundancy that is consistent with the PID formalism. This has an important implication: entropic conjugation lets us exchange synergies and redundancies without having to specify a functional form for them.

Let’s illustrate this point with a basic example. Using the fact that the O-information is equal to redundancy minus synergy25, Th. 1 implies that

However, note that the same result could have been obtained by simply expressing Ω(X1; X2; Y) in terms of entropies using Eq. (6) and applying Def. 1. The fact that applying entropic conjugation to Ω(X1; X2; Y) gives a minus sign implies that this quantity displays a balanced number of synergy and redundancy terms with opposite signs. This observation leads to a general principle to analyse high-order measures that will be developed in the next section.

Symmetric and skew-symmetric quantities

One of the useful implications of conjugations is that they naturally define symmetric and skew-symmetric objects — e.g., Hermitian transposition defines symmetric and skew-symmetric matrices, and complex conjugation establishes purely real and imaginary numbers. We now use the same principle to introduce the notions of symmetric and skew-symmetric metrics of interdependence.

Definition 2

A linear combination of entropies \(\phi ={\sum }_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}\subseteq {I}_{n}}{\lambda }_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}})\) is symmetric if (ϕ)* = ϕ and skew-symmetric if (ϕ)* = − ϕ.

This definition, combined with Prop. 1 and Th. 1, implies that symmetric and skew-symmetric quantities provide balanced accounts of low- and high-order interdependencies (alternatively, redundancies and synergies): symmetric quantities weight these equally, while skew-symmetric quantities weight them equally but with opposite signs. A practical way to recognise symmetric and skew-symmetric high-order metrics is via their weights in terms of the basis uk, as shown next.

Lemma 2

If \(\phi ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})={{\sum }_{k=1}^{c}{k}}{u}_{k}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})\), then

-

ϕ is symmetric ⇔ ck = cn−k.

-

ϕ is skew-symmetric ⇔ ck = − cn−k.

With these tools at hand, we now study the existent high-order quantities under the lens of conjugation.

Proposition 2

The mentioned multivariate measures can be decomposed as follows:

Therefore, the following relationships hold:

These results show that the S-information and TSE complexity are balanced metrics of overall interdependence strength, while the O-information provides a balanced opposition between high- and low-order interdependencies. In contrast, the interaction information alternates between being symmetric or skew-symmetric in a way that will be better understood in the next subsection. Additionally, this result also shows that the TC and DTC are not balanced, being duals to each other: the TC provides more weight to low-order effects while the DTC to high-order ones.

These results also reveal that this collection of measures is not as arbitrary as it may seem: when seen from their coefficients ck, they cover the constant (S-information), linear (TC, DTC, and O-information), quadratic (TSE), and binomial (interaction information) cases.

Spanning the possible metrics

Another useful implication of conjugations is that they define a natural decomposition of objects in terms of symmetric and skew-symmetric components. For instance, complex conjugation reveals that every complex number is a sum of a real and an imaginary part, and Hermitian transposition that every matrix is a sum of a symmetric and skew-symmetric components. Building on this rationale, we now show that entropic conjugation induces a decomposition of high-order quantities into symmetric and skew-symmetric components.

Theorem 2

Every information-theoretic metric of interdependence \(\phi ={\sum }_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}\subseteq {I}_{n}}{\lambda }_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}})\) can be decomposed into unique symmetric and skew-symmetric components given by

Moreover, symmetric and skew-symmetric components are orthogonal under the inner product induced by \(\langle {u}_{k},{u}_{j}\rangle ={\delta }_{j}^{k}\).

For example, by taking ϕ = TC, Th. 2 states that the total correlation can be expressed as

where \(\frac{1}{2}\Sigma =\frac{1}{2}({{{\rm{TC}}}}+{{{{\rm{TC}}}}}^{* })\) is its symmetric component and \(\frac{1}{2}\Omega =\frac{1}{2}({{{\rm{TC}}}}-{{{{\rm{TC}}}}}^{* })\) its skew-symmetric component. Similarly, the dual total correlation can be expressed as

More generally, this result provides a guide to investigate the geometry of the (n − 1)-dimensional space of high-order quantities ϕ satisfying labelling-symmetry and dependency, which we denote by \({{{{\mathscr{I}}}}}_{n}\).

Corollary 1

If X has n variables, then the (n − 1) dimensions of \({{{\mathscr{I}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})\) are divided in the following way:

These results have the following consequences:- For n = 2 variables, Shannon’s mutual information is the only symmetric functional (up to scaling), as there are no skew-symmetric functionals.- For n = 3 variables, the S-information is the only symmetric functional and the O-information (equivalently, the interaction information) is the only skew-symmetric one (up to scaling). Therefore, if \(\phi \in {{{{\mathscr{I}}}}}_{3}\) then ϕ(X) = αΣ(X) + βΩ(X).- For n = 4 variables, the S-information and the interaction information span the subspace of symmetric quantities, while the O-information is the only skew-symmetric one (up to scaling). Therefore, if \(\phi \in {{{{\mathscr{I}}}}}_{4}\) then \(\phi ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})=\alpha \Sigma ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})+\alpha ^{\prime} {{{\rm{II}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})+\beta \Omega ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})\).- For n = 5 variables, the space of symmetric quantities is spanned by the S-information and the TSE-complexity, and the space of skew-symmetric quantities is spanned by the O-information and the interaction information. Therefore, if \(\phi \in {{{{\mathscr{I}}}}}_{5}\) then \(\phi ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})=\alpha \Sigma ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})+\alpha ^{\prime} {{{\rm{TSE}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})+\beta \Omega ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})+\beta ^{\prime} {{{\rm{II}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})\). Larger systems can be analysed in a similar fashion, but the existing measures of high-order information do not cover all the dimensions.

Computational tractability

Most uk (and, therefore, most high-order measures) require estimating a large number of information-theoretic terms, and hence their computation becomes unfeasible when n grows. Our next result narrows down the space of computationally efficient symmetric and skew-symmetric metrics of high-order interdependence.

Proposition 3

The S-information and O-information are the only symmetric and skew-symmetric metrics of interdependence that can be computed via a linear number of entropy terms.

This result may explain, at least in part, the suitability of the O-information for practical analyses of high-order effects — as demonstrated by various empirical investigations43,44,45,46,47. Note that the TC and DTC also require a linear number of terms, but they are neither symmetric or skew-symmetric.

Empirical results

To illustrate the proposed framework, we showcase three examples of increasing complexity: simple multivariate distributions, spin systems, and empirical data from polyphonic music scores. All of these involve estimating multivariate discrete distributions and calculating the values of uk(X) according to Eq. (10). The details of the methods and datasets are described in subsection Numerical analyses in Methods.

We begin analysing a simple multivariate system whose distribution has one degree of freedom, which allows it to display different interdependencies ranging from highly redundant to highly synergistic. Taking inspiration in previous work25,48, we implement this via the so-called W-distribution:

with x ∈ {0, 1}n being a binary vector of n components and 0 ≤ w ≤ 1 a mixture coefficient. Above, pcopy(x) is a distribution in which all binary components are copies of each other, and pcopy(x) encodes an n-th order XOR (see Numerical analyses in Methods). Based on previous work, it is expected that pw(x) for w ≈ 0 corresponds to a system dominated by redundant information, while for w ≈ 1 it corresponds to a system dominated by synergistic information.

To investigate the interdependencies elicited by the W-distribution by calculating the values of uk(X) (see Fig. 1). Results show that the effect of changes in the mixture coefficient are tracked by the terms corresponding to the lowest- and highest-order interactions, u1(X) and un−1(X), while the other uk(X) for intermediate values of k remain comparatively small. Furthermore, as expected, u1(X) (resp. un−1(X)) is highest when the system is close to a copy (resp. XOR) distribution. This confirms that the quantities uk effectively capture our intuitive notions of low- and high-order statistical structure in these simple systems.

Description of the interdependencies within n = 7 binary variables considering a mixture of n identical bits (COPY) and an n-th order exclusive-or (XOR) given by the uk quantities. As expected, the effects of the mixture are tracked by the terms corresponding to the lowest- and highest-order interactions. In the figure, continuous and dotted lines are used for enhancing visual clarity.

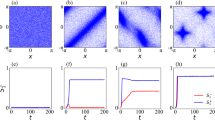

Next, we build on previous work49,50 and investigate the interdependencies exhibited by small spin systems under weak, ferromagnetic (positive), and frustrated (negative) types of interactions. We implemented these systems by considering Boltzmann distributions with fully-connected random Hamiltonians, and varying the sign of their average coupling (for details, see subsection Numerical analyses in Methods). The frustrated condition makes it impossible to simultaneously satisfy the tendency of all spins to be different from their neighbours, which is known to induce high-order interdependencies17,51.

We again calculated the values of uk, and this time investigated their principal axes of variability via principal component analysis (see Numerical analyses in Methods). Results show that two components explain almost all the variability: a first component of symmetric character similar to the S-information, and a second component of skew-symmetric character similar to the O-information (Fig. 2). This shows that an optimal information-theoretic analysis to characterise the high-order interdependence of these systems reduces to two key aspects: (i) their strength given by the symmetric component, and (ii) the balance between high- and low-order components given by the skew-symmetric component.

a When calculating uk, each type of interactions exhibit distinct profiles of interdependence. b The variability among uk is captured by two principal components: one of symmetric character which accounts for the overall strength of the interdependence (PC1), and one of skew-symmetric character that accounts for the balance between high- and low-order interdependence (PC2). c The values of uk projected onto these PCs provide a simple characterisation of these three types of systems in terms of their overall interdependence strength (PC1) and the balance between high- and low-order effects (PC2).

To further explore the applicability of this framework, we perform similar analyses to empirical data corresponding to polyphonic music scores. We leveraged a rich open dataset and selected a corpus consisting of 522 pieces of choral music from the early Renaissance employing n = 3, 4, or 5 simultaneous voices in a polyphonic manner (for details, see Numerical analyses in Methods). These datasets consider simultaneous singing voices that take discrete values (12 notes plus silence), leading to statistical relationships that often include complex high-order interdependencies25,52.

By repeating the analysis on the principal axes of variability of the values of uk(X), result shows that—similarly to the case of spin systems—most of the variability is captured by the first two components (Fig. 3a). These are again a symmetric and a skew-symmetric component, with the latter one closely resembling the O-information. This suggests that, despite the stark differences between spins and singing voices, an optimal information-theoretic analysis of these systems remains similar to previous case, including an assessment of the strength of interdependencies and a balance between high- and low-order components.

a Resembling the results presented in Fig. 2, the variability among uk is captured mainly by two principal components: one of skew-symmetric character that accounts for the balance between high- and low-order interdependence (PC1), and one of symmetric character that accounts for the overall strength of the interdependence (PC2). b Relationship between O-information, S-information, and interaction information. Results reveal a substantial correlation (∣ρ∣ > 0.5) between symmetric or skew-symmetric high-order measures, which is consistent with the switching nature of the interaction information.

As a final analysis, we also calculated the O-information, S-information, and interaction information for each of these music pieces (Fig. 3b). Results show that while the O-information and S-information are largely uncorrelated, there exists a substantial correlation (∣ρ∣ > 0.5) between the interaction information and the S-information when the number of voices is n = 4 (ρ = − 0.52), and the interaction information and the O-information when the number of voices is n = 5 (ρ = − 0.87). Please note that the identity between the interaction information and O-information when n = 3 is expected, given that in that scenario their definitions coincide. These perhaps unexpected correlations can be elegantly explained by our theory, particularly by the fact that the interaction information is symmetric for even values of n and skew-symmetric for odd values of n (see Prop. 2).

Discussion

Here we investigated the space of possible metrics of high-order interdependence taking the form of linear combinations of Shannon entropies. We introduced the notion of entropic conjugation, the effect of which can be understood in two complementary ways: as exchanging how metrics account for high- and low-order interdependencies, or alternatively, how they account for redundancies and synergies. Crucially, while various alternative definitions of synergy and redundancy exist28, the properties of entropy conjugation hold for all approaches that are consistent with the PID formalism irrespective of the specific functional forms used to operationalise these notions.

When studying high-order quantities, non-negative measures such as the S-information and TSE complexity were found to be invariant (i.e. symmetric) under entropic conjugation, confirming that they provide a balanced account of overall interdependence strength. Similarly, applying entropic conjugation to a signed quantities such as the O-information results in a minus sign (i.e. skew-symmetric), guaranteeing that it provides a fair balance of the relative strength of redundancies and synergies. The interaction information was found to be either symmetric or skew-symmetric depending on the number of variables, providing a principled explanation to the observation (first made in Ref. 27) that interpreting this quantity from a high-order perspective requires nuance. This property was found to provide an elegant explanation to otherwise paradoxical empirical associations of the interaction information with other quantities that switched depending on the system’s size.

This framework also let us prove that the well-known high-order information measures cover all possibilities when considering systems of up to n = 5 variables. A similar analysis revealed that, in contrast, the space of possible high-order information measures for capturing interactions involving more than five variables remains largely unexplored. Additionally, the S-information and O-information were found to be the unique symmetric and skew-symmetric quantities whose estimation involves a number of terms that grow linearly with system size, making them ideally suited for practical analyses. Furthermore, numerical studies showed how symmetric and skew-symmetric quantities provide natural axes of variation among high-order quantities. In particular, the O-information was found to naturally arise in the analysis of high-order properties of multivariate systems as dissimilar as Ising spin models and Renaissance choral music. Together, these findings establish the O-information on a privileged position for empirical analyses due to its favourable analytical and phenomenological properties.

Overall, the framework put forward in this work establishes a solid foundation for a formal understanding of high-order information measures, while opening numerous directions for future work along theoretical and practical avenues. For example, while this study focuses on the analysis and interpretation of existent high-order measures, our ongoing work is exploring the potential of this framework to build new quantities tailored via specific desiderata. Additionally, future work may go beyond symmetric quantities to investigate the applicability of entropy conjugation to study directed high-order measures such as the redundancy-synergy index20,53, the dynamic O-information44, or the gradients of O-information50. Also, future work may explore the potential of entropy conjugation to unify pointwise high-order information theoretic quantities54, although in this case the requirement of non-negativity should be treated differently. Furthermore, an interesting challenge would be to extend entropy conjugation to non-Shannon entropies55,56,57 or even to topological notions of high-order phenomena58.

Methods

Numerical analyses

All numerical analyses were done using the Python package dit59. Code for calculating uk(X) for multivariate distributions p(x) is provided (see Data availability).

W-distribution

The W-distribution is a linear mixture of a copy and an xor distribution over a vector X = (X1, …, Xn) of n binary random variables, so that x ∈ {0, 1}n. To formally define it, let us first define the n-bit copy distribution as

Correspondingly, the n-bit XOR distribution is defined as

With these, the W-distribution can be directly defined as the following mixture:

Spin systems

Our experiments considered systems of n spins X = (X1, …, Xn) ∈ {−1, 1}n following a Boltzmann distribution pX(x) = e−βH(x)/Z with a Hamiltonian of the form

where the coupling coefficients Ji,k are i.i.d. sampled from a Gaussian distribution with mean μ and variance σ2. The results reported in Fig. 1 corresponds to systems of n = 8 spins with β = 1, σ2 = 2, and either μ = 5 (ferromagnetic), μ = 0 (weak), or μ = − 5 (frustrated). We first computed the joint distribution of 10 systems of each type, each with randomly sampled Jik, and calculated the value of uk for each of them.

Music scores

Our analysis is based on the electronic scores publicly available at http://kern.ccarh.org. The analyses focuses on choral repertoire from the early Renassaice (late XV and early XVI centuries). These pieces are characterised by an elaborate counterpoint between melodic lines, resulting in rich textures of balanced richness involving all voices — contrasting with the latter Classic (1730-1820) and Romantic (1780−1910) periods, where higher voices tend to take the lead.

We focused on scores with n = 3, n = 4, or n = 5 melodic lines from four contemporain composes: Josquin des Prez (1450−1521), Johannes Martini (1440−1498), Johannes Ockeghem (1410−1497), and Pierre la Rue (1452−1518). This let us obtain a total of 106 (n = 3), 344 (n = 4), and 72 (n = 5) pieces. The scores were pre-processed in Python using the Music21 package (http://web.mit.edu/music21). The melodic lines were transformed into time series of 13 possible discrete values (one for each note plus one for the silence), using the smallest rhythmic duration as time unit. In order to focus on polyphonic harmony, chords with 40% or more silent voices were dropped. With these data, the joint distribution of the values for the chords was estimated using their empirical frequency. We estimated a joint distribution for each piece, and then calculated the value of uk.

Principal component analysis

Our analysis pipeline for both the spin system and the music scores was structured as follows. In both cases, the resulting uk values were then used to perform a principal component analysis. From this, we obtained the loadings of the two first principal components, denoted as ξk and νj, respectively. For the analysis of spin systems, these loadings were then used to construct two high-order quantities: \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PC}}}}1}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}):= {\sum }_{k = 1}^{n-1}{\xi }_{k}{u}_{k}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})\) and \({\phi }_{{{{\rm{PC}}}}2}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}):= {\sum }_{j = 1}^{n-1}{\nu }_{j}{u}_{j}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})\), which corresponds to projecting the value of the uk’s onto the directions given by the principal components. These two resulting metrics were used to characterise the systems of interest.

Short proofs

In the following, we present the proofs of our theoretical results.

Proof

(Proof of Lemma. 1) Let us first prove Eq. (16). For this, consider a, b, c to be disjoint subsets of indices. Then,

where the last equality uses the fact that I(A; B∣C) = H(A, C) + H(B, C) − H(C) − H(A, B, C) with A = Xa, B = Xb, and C = X−a∪b∪c.

Let us now show that Eq. (16) is equivalent to Definition 1. For this, let’s assume that * is a linear operation defined on the mutual information as in Eq. (16). Then, using \({{{\boldsymbol{c}}}}=\varnothing\) one can find that

which by expanding both sides in terms of entropies yields

Then, by fixing a and varying b one can note that this implies that

where C is a quantity that does not depend on a or b. Moreover, it is needed that C = H(X), proving the equivalence.

Proof

(Proof of Prop. 1) To prove Eq. (17), we first focus on rk as defined in Eq. (8) and note that

Then, using the definition in Eq. (9), one can find that

Proof

(Proof of Lemma 2) The proof follows directly from Definitions 1 and 2.

Proof

(Proof of Prop. 2) The expressions for each metric can be directly verified by applying the definition of uk in terms of rk from Eq. (9), and expressing rk in terms of entropies using Eq. (8). The second part of the proposition follows by using Lemma 2.

Proof

(Proof of Th. 2) Let’s denote as S = (ϕ + ϕ*)/2 and T = (ϕ − ϕ*)/2 the components proposed in the proposition, which can be directly shown to be symmetric and skew-symmetric and satisfying ϕ = S + T. Let’s assume there is another decomposition \(\phi ={S}^{{\prime} }+{T}^{{\prime} }\) where \({({S}^{{\prime} })}^{* }={S}^{{\prime} }\) and \({({T}^{{\prime} })}^{* }=-{T}^{* }\). However this would imply that \(\phi +{\phi }^{* }=2{S}^{{\prime} }\) and \(\phi -{\phi }^{* }=-2{T}^{{\prime} }\), which leads to \(S={S}^{{\prime} }\) and \(T={T}^{{\prime} }\), showing that the decomposition is unique. The orthogonality of these subspaces follows directly from Lemma 2.

Proof

(Proof of Prop. 3) Consider \(\phi ={\sum }_{k = 1}^{n-1}{c}_{k}{u}_{k}\). Using Eq. (9) one can re-write ϕ in terms of rk. Since every entropy term appears only in exactly one of the rk, there cannot be any term cancellations. Therefore, ϕ involves a linear number of (unconditional) entropy terms if and only if the resulting coefficients are non-zero only for r1, rn−1, and rn.

Let us first consider the case in which ck = αk + β is linear on k. Then, one can show that

By using the fact that Δ2rk = Δrk+1 − Δrk where Δrk ≔ rk − rk−1, one can use discrete calculus to find that

This calculation leads to \(\phi =\beta {r}_{1}^{n}+(\alpha n+\beta ){r}_{n-1}^{n}-(\alpha (n-1)+\beta ){r}_{n}^{n}\), showing that ϕ only includes a linear number of entropies.

To prove the converse statement, let’s consider a quantity ϕ = ∑kckuk, and let’s denote its coefficients under rk and Δrk as ak and bk respectively, so that ϕ = ∑iairi = ∑jbjΔrj hold. As the rk are linearly independent, one can see that the above equations imply that the following conditions hold for all k = 1, …, n − 2:

Now, note that ak = 0 with k ∈ {2, …, n − 2} requires that bk = bk+1, and hence the above condition forces b1 = … = bn−1. Then, applying the same reasoning shows that ck − ck+1 has to be constant, which proves that ck depends linearly on k.

The above shows that the space of quantities that can be computed with a linear number of terms is two-dimensional, being spanned by DTC (α = 1, β = 0) and the S-information (α = 0, β = n). This space is also spanned by the S-information and the O-information, concluding the proof.

PID conjugation

Here we provide a more detailed introduction to PID, and then introduce the natural conjugation that takes place at the level of PID atoms.

Following Eq. (13), PID introduces a decomposition of the mutual information I(X; Y) in terms of information atoms of the form \({I}_{\partial }^{{{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\), where α = {α1, …, αl} with αj ⊆ In being sets of indices of the source variables X1, …, Xn such that no αj contains another αk — making α an ‘anti-chain’ of sets of sources. Conceptually, \({I}_{\partial }^{{{{\boldsymbol{\alpha }}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) quantifies the information about the target variable Y that is accessible via each collection of source variables α1, …, αl, while not being accessible via subsets of those collections or any other collections that do not include them. For example, if n = 2 then \({I}_{\partial }^{\{\{1,2\}\}}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) corresponds to the information accessible in (X1, X2) but not accessible from X1 or X2 by themselves.

The accessibility relations denoted by PID antichains can be made explicit by ‘re-representing’ them in terms of Boolean functions \(f:{{{{\mathscr{P}}}}}_{n}\mapsto \{0,1\}\), where \({{{{\mathscr{P}}}}}_{n}\) is the powerset of {1, …, n}, taking a set of source indices as an input and returning 0 or 1 depending on whether the associated atom \({I}_{\partial }^{f}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) is or isn’t accessible via the set of sources. For example, the atom α = {{1, 2}} corresponds to the Boolean function that gives \(f(\varnothing )=f(\{1\})=f(\{2\})=0\) and f({1, 2}) = 1. Crucially, it has been shown that there is a natural isomorphism between PID antichains and monotonic Boolean functions60,61, which implies that PID can be re-defined as follows.

Definition 3

A PID of the information provided by X = (X1, …, Xn) about Y is a set of quantities \({I}_{\partial }^{f}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) that satisfy for all a ⊆ {1, …, n}

where \({{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{n}\) is the set of all non-constant monotonic Boolean functions \(f:{{{{\mathscr{P}}}}}_{n}\mapsto \{0,1\}\).

Note that Eq. (43) is equivalent to Eq. (13), with the only difference being the way in which PID atoms are labelled (either as antichains or Boolean functions). That said, viewing PID in terms of Boolean functions lets us conveniently handle various expressions, as shown below.

Lemma 3

Given two disjoint sets of source variables a and b, we have

where \({{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}}=\{f\in {{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{n}:f({{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}\cup {{{\boldsymbol{b}}}})=1,f({{{\boldsymbol{b}}}})=0\}\).

Note that the set \({{{{\mathscr{A}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}}\) used in Th. 1 corresponds to the same atoms in \({{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{b}}}}}\) but represented in antichain form instead of as Boolean functions.

Proof

The information atoms have a natural order in terms of their accessibility: an atom \({I}_{\partial }^{f}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) can be said to be ‘more accessible’ than an atom \({I}_{\partial }^{g}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) if any set via which the latter is accessible is also a set via which the former is accessible. This property is elegantly captured by the Boolean function representation of atoms via the following partial ordering:

Note that this partial ordering gives rise to a lattice of PID atoms denoted by \(({{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{n}, \sqsubseteq )\), which is isomorphic to the original PID lattice of antichains61.

Let us now introduce the notion of PID conjugation. For this, let us first note that, according to the order-theoretic principle of duality41, every lattice has a dual lattice in which all arrows are reverted. If we think of Boolean functions as bitstrings (with subsets ordered lexicographically), the dual of the PID lattice can be found by simply inverting the digits and reading the bitstring backwards, as shown by our next result.

Proposition 4

The mapping f ↦ f†, where f† is the Boolean function satisfying

is an order-reversing involution on \(({{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{n}, \sqsubseteq )\).

Proof

Involution: f††(a) = 1 if and only if \(f({({{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}^{C})}^{C})=f({{{\boldsymbol{a}}}})=1\). Hence, f †† = f. Order-reversing: Suppose first that f ⊑ g, meaning that g(a) = 1 → f(a) = 1. Then, if f †(a) = 1 we must have f(ac) = 0 and so g(ac);= 0 and hence g†(a) = 1. Therefore we have g† ⊑ f†. Conversely, if g† ⊑ f†, then f †(a) = 1 → g†(a) = 1. Hence, if g(a) = 1 it follows that g†(ac) = 0 and thus f †(ac) = 0 and thus f(a) = 1. Therefore, f ⊑ g.

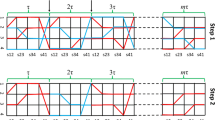

The effect of † on the PID lattice can be understood as follows (see Fig. 4). Following Ref. 62, each atom can be expressed as concatenations of meet and join operations corresponding to redundancies and synergies. For example, the atom α = {{1, 2}, {1, 3}} can be constructed as (1 ∨ 2) ∧ (2 ∨ 3), where the join operation ( ∨ ) can be thought of as denoting the union between sources (i.e., synergy), and the meet operation ( ∧ ) as the intersection between them (i.e., redundancy). Then, the involution introduced in Proposition 4 can be understood as switching meets for joins and vice-versa. For example

where equality (a) uses the distributivity between meets and joins62. This shows that the natural PID involution switches redundancy (i.e. easily accessible information, since it is contained in multiple sources) and synergy (i.e. difficult to access information, since one needs to observe multiple sources). Thus, the more easily an atom can be accessed, the more difficult it is to access its conjugate.

This PID involution leads to a natural conjugation between PID atoms, which we define next.

Definition 4

The conjugate of a PID atom is given by

where f† is as defined in Prop. 4. Additionally, the conjugate of a linear combination of PID atoms \(\psi ({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})={\sum}_{f\in {{{{\mathscr{B}}}}}_{n}}{c}_{f}{I}_{\partial }^{f}({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}})\) is defined as

We now prove Theorem 1, which states that applying PID conjugation on a conditional mutual information I(Xa; Y∣Xb) leads to the same outcome as entropic conjugation does — namely, \(I({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}};{{{\boldsymbol{Y}}}}| {{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{({{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}\cup {{{\boldsymbol{b}}}})}^{C}})\), where the complement is taken within the set of source variables.

Proof

(Proof of Th. 1) For a, b disjoint subsets of In, then

where the second to last equality follows because a ∪ (a∪b)C = bC if a and b are disjoint.

Please note that the proof uses no properties specific to particular instantiations of synergy or redundancy, and hence the result holds for any operationalisation of these quantities that are consistent with the PID framework.

Linear involutions of entropies

When considering all linear combinations of entropies of the form of Eq. (1) as a vector space spanned by the functions H(Xa), linear involutions can be characterised as linear operators T with the property T2 = I, with I being the identity operator. This implies that there are many linear involutions — for example, any operation exchanging between basis elements reciprocally is one such operation (e.g. \({(H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}))}^{{\prime} }=H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{-{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}})\)). Other linear involutions include \({(H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}))}^{{\prime\prime} }=H({{{\boldsymbol{X}}}})-H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{-{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}})\), and also the negentropy (\({(H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}}))}^{{\prime\prime} {\prime} }=\mathop{\sum }_{i = 1}^{n}\log | {{{{\mathscr{X}}}}}_{i}| -H({{{{\boldsymbol{X}}}}}^{-{{{\boldsymbol{a}}}}})\), defined for variables over finite alphabets \({{{{\mathscr{X}}}}}_{i}\) with i = 1, …, n) provides a linear involution.

Crucially, just as there are many linear involutions over complex numbers but complex conjugation is highlighted for its special properties, in this paper we focus on the proposed entropy conjugation for its unique properties pertaining high order effects. In particular, as outlined by Lemma 1, Prop. 1, and Th. 1, entropic conjugation is the only linear involution that yields a simple exchange between the quantities uk of different orders as in Eq. (17) (other variants would make the relationship more complicated, e.g. introducing a minus sign, etc) and also an exchange between redundancies and synergies in PID atoms.

Code availability

The code associated with the results presented in this paper are available in the repository https://github.com/Imperial-MIND-lab/entropic-conjugation.

Data availability

The data associated with the results presented in this paper are available in the repository https://github.com/Imperial-MIND-lab/entropic-conjugation.

References

Battiston, F. & Petri, G. Higher-Order Systems (Springer, 2022).

Battiston, F. et al. Networks beyond pairwise interactions: structure and dynamics. Phys. Rep. 874, 1–92 (2020).

Battiston, F. et al. The physics of higher-order interactions in complex systems. Nat. Phys. 17, 1093–1098 (2021).

Santoro, A., Battiston, F., Petri, G. & Amico, E. Higher-order organization of multivariate time series. Nat. Phys. 19, 221–229 (2023).

Cang, Z. & Nie, Q. Inferring spatial and signaling relationships between cells from single cell transcriptomic data. Nat. Commun. 11, 2084 (2020).

Park, S., Supek, F. & Lehner, B. Higher order genetic interactions switch cancer genes from two-hit to one-hit drivers. Nat. Commun. 12, 7051 (2021).

Gatica, M. et al. High-order interdependencies in the aging brain. Brain Connect. 11, 734–744 (2021).

Luppi, A. I. et al. A synergistic core for human brain evolution and cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 771–782 (2022).

Herzog, R. et al. Genuine high-order interactions in brain networks and neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 175, 105918 (2022).

Varley, T. F., Sporns, O., Schaffelhofer, S., Scherberger, H. & Dann, B. Information-processing dynamics in neural networks of macaque cerebral cortex reflect cognitive state and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2207677120 (2023).

Varley, T. F., Pope, M., Faskowitz, J. & Sporns, O. Multivariate information theory uncovers synergistic subsystems of the human cerebral cortex. Commun. Biol. 6, 451 (2023).

Tax, T. M., Mediano, P. A. & Shanahan, M. The partial information decomposition of generative neural network models. Entropy 19, 474 (2017).

Proca, A. M. et al. ynergistic information supports modality integration and flexible learning in neural networks solving multiple tasks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 20, e1012178 (2024).

Kaplanis, C., Mediano, P. & Rosas, F. Learning causally emergent representations. In NeurIPS 2023 workshop: Information-Theoretic Principles in Cognitive Systems (2023).

Varley, T. F. & Bongard, J. Evolving higher-order synergies reveals a trade-off between stability and information-integration capacity in complex systems. J. Nonlinear Sci. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.14347 (2024).

Luppi, A. I., Rosas, F. E., Mediano, P. A., Menon, D. K. & Stamatakis, E. A. Information decomposition and the informational architecture of the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28, 352−368 (2024).

Rosas, F. E. et al. Disentangling high-order mechanisms and high-order behaviours in complex systems. Nat. Phys. 18, 476–477 (2022).

Balduzzi, D. & Tononi, G. Integrated information in discrete dynamical systems: motivation and theoretical framework. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000091 (2008).

Timme, N., Alford, W., Flecker, B. & Beggs, J. M. Synergy, redundancy, and multivariate information measures: an experimentalist’s perspective. J. Comput. Neurosci. 36, 119–140 (2014).

Rosas, F. E., Mediano, P. A. & Gastpar, M. Characterising directed and undirected metrics of high-order interdependence. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory Workshops (ISIT-W), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

McGill, W. Multivariate information transmission. Trans. IRE Professional Group Inf. Theory 4, 93–111 (1954).

Watanabe, S. Information theoretical analysis of multivariate correlation. IBM J. Res. Dev. 4, 66–82 (1960).

Sun, T. Linear dependence structure of the entropy space. Inf. Control 29, 337–368 (1975).

Tononi, G., Sporns, O. & Edelman, G. M. A measure for brain complexity: relating functional segregation and integration in the nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 5033–5037 (1994).

Rosas, F. E., Mediano, P. A., Gastpar, M. & Jensen, H. J. Quantifying high-order interdependencies via multivariate extensions of the mutual information. Phys. Rev. E 100, 032305 (2019).

Han, T. S. Nonnegative entropy measures of multivariate symmetric correlations. Inf. Control 36, 133–156 (1978).

Williams, P. L. & Beer, R. D. Nonnegative decomposition of multivariate information. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1004.2515 (2010).

Wibral, M., Priesemann, V., Kay, J. W., Lizier, J. T. & Phillips, W. A. Partial information decomposition as a unified approach to the specification of neural goal functions. Brain Cogn. 112, 25–38 (2017).

Mediano, P. A. et al. Towards an extended taxonomy of information dynamics via integrated information decomposition. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2109.13186 (2021). In press.

Bertschinger, N., Rauh, J., Olbrich, E. & Jost, J. Shared information-new insights and problems in decomposing information in complex systems. In Proceedings of the European conference on complex systems 2012, 251–269 (Springer, 2013).

Griffith, V. Quantifying Synergistic Information. (California Institute of Technology, 2014).

Harder, M., Salge, C. & Polani, D. Bivariate measure of redundant information. Phys. Rev. E 87, 012130 (2013).

Barrett, A. B. Exploration of synergistic and redundant information sharing in static and dynamical gaussian systems. Phys. Rev. E 91, 052802 (2015).

Ince, R. A. Measuring multivariate redundant information with pointwise common change in surprisal. Entropy 19, 318 (2017).

James, R. G., Emenheiser, J. & Crutchfield, J. P. Unique information via dependency constraints. J. Phys. A. Math. Theor. 52, 014002 (2018).

Griffith, V., Chong, E. K., James, R. G., Ellison, C. J. & Crutchfield, J. P. Intersection information based on common randomness. Entropy 16, 1985–2000 (2014).

Griffith, V. & Ho, T. Quantifying redundant information in predicting a target random variable. Entropy 17, 4644–4653 (2015).

Quax, R., Har-Shemesh, O. & Sloot, P. M. Quantifying synergistic information using intermediate stochastic variables. Entropy 19, 85 (2017).

Rosas, F. E., Mediano, P. A., Rassouli, B. & Barrett, A. B. An operational information decomposition via synergistic disclosure. J. Phys. A. Math. Theor. 53, 485001 (2020).

Makkeh, A., Gutknecht, A. J. & Wibral, M. Introducing a differentiable measure of pointwise shared information. Phys. Rev. E 103, 032149 (2021).

Davey, B. Introduction to Lattices and Order. (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Spivak, D. I. Category Theory for the Sciences, Vol. 609 (MIT press, 2014).

Medina-Mardones, A. M., Rosas, F. E., Rodríguez, S. E. & Cofré, R. Hyperharmonic analysis for the study of high-order information-theoretic signals. J. Phys. Complex. 2, 035009 (2021).

Stramaglia, S., Scagliarini, T., Daniels, B. C. & Marinazzo, D. Quantifying dynamical high-order interdependencies from the o-information: an application to neural spiking dynamics. Front. Physiol. 11, 595736 (2021).

Varley, T. F., Pope, M., Grazia, M., Joshua, J. & Sporns, O. Partial entropy decomposition reveals higher-order information structures in human brain activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2300888120 (2023).

Herzog, R. et al. High-order brain interactions in ketamine during rest and task: a double-blinded cross-over design using portable EEG on male participants. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 310 (2024).

Sparacino, L., Antonacci, Y., Mijatovic, G. & Faes, L. Measuring hierarchically-organized interactions in dynamic networks through spectral entropy rates: theory, estimation, and illustrative application to physiological networks. Neurocomputing 630, 129675 (2025).

Varley, T. F. A scalable synergy-first backbone decomposition of higher-order structures in complex systems. NPJ Complex. 1, 9 (2024).

Vijayaraghavan, V. S., James, R. G. & Crutchfield, J. P. Anatomy of a spin: the information-theoretic structure of classical spin systems. Entropy 19, 214 (2017).

Scagliarini, T. et al. Gradients of o-information: low-order descriptors of high-order dependencies. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013025 (2023).

Matsuda, H. Physical nature of higher-order mutual information: Intrinsic correlations and frustration. Phys. Rev. E 62, 3096 (2000).

Scagliarini, T., Marinazzo, D., Guo, Y., Stramaglia, S. & Rosas, F. E. Quantifying high-order interdependencies on individual patterns via the local o-information: theory and applications to music analysis. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013184 (2022).

Chechik, G. et al. Group redundancy measures reveal redundancy reduction in the auditory pathway. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 14 (NIPS, 2001).

Lizier, J. T. The Local Information Dynamics of Distributed Computation in Complex Systems 1st edn, Vol. 236 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Hanel, R., Thurner, S. & Gell-Mann, M. Generalized entropies and logarithms and their duality relations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 19151–19154 (2012).

Morales, P. A. & Rosas, F. E. Generalization of the maximum entropy principle for curved statistical manifolds. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033216 (2021).

Jensen, H. J. & Tempesta, P. Group structure as a foundation for entropies. Entropy 26, 266 (2024).

Millán, A. P. et al. Topology shapes dynamics of higher-order networks. Nat. Phys. 21, 353–361 (2025).

James, R. G., Ellison, C. J. & Crutchfield, J. P. "dit": a python package for discrete information theory. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 738 (2018).

Gutknecht, A. J., Wibral, M. & Makkeh, A. Bits and pieces: Understanding information decomposition from part-whole relationships and formal logic. Proc. R. Soc. A 477, 20210110 (2021).

Gutknecht, A. J., Makkeh, A. & Wibral, M. From babel to boole: the logical organization of information decompositions. Proc. R. Soc. 481, 20240174 (2025).

Jansma, A., Mediano, P. A. & Rosas, F. E. The fast möbius transform: an algebraic approach to information decomposition. Phys. Rev. Res. 7, 033049 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The work of F.R. has been supported by the UK ARIA Safeguarded AI programme and by the PIBBSS affiliateship programme. The work of M.G. has been supported in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation under Grant 200364.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.R., A.G., P.M., and M.G. contributed to the conception and design of the work, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. F.R. and P.M. carried out the numerical analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosas, F.E., Gutknecht, A.J., Mediano, P.A.M. et al. Characterising high-order interdependence via entropic conjugation. Commun Phys 8, 347 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02250-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02250-7

This article is cited by

-

Towards an informational account of interpersonal coordination

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2025)