Abstract

The presence of a quantum-critical point (QCP) at which a nearby ordered phase is suppressed to zero temperature is often invoked to explain emergent quantum phases, e.g. superconductivity. Yet, identifying a QCP and establishing its correlation with superconductivity remains challenging. Materials featuring charge-density-wave (CDW) order and superconductivity offer a clear scenario as both states can be associated with electron-phonon coupling. Here, we uncover a CDW-QCP and demonstrate its interrelation with superconductivity in the prototypical transition-metal dichalcogenide 2H-TaSe2. We determine the evolution of the CDW state up to and beyond its suppression at the critical pressure pc = 19.9(1) GPa by means of X-ray diffraction and inelastic X-ray scattering measurements providing a full crystallographic refinement of the commensurate CDW superstructure. The pressure-induced CDW-QCP in close vicinity to the maximum superconducting transition temperature. Ab-initio lattice dynamical calculations corroborate that 2H-TaSe2 features order-parameter fluctuation enhanced superconductivity and can serve as a paradigm to investigate superconductivity near a CDW-QCP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continuous suppression of an ordered state to zero temperature at a quantum critical point (QCP) is often linked to emerging superconductivity. Indeed, a correlation between the suppression of an ordered state, e.g., by chemical- and/or physical pressure, and a maximum of the superconducting transition temperature Tsc is known in various materials1,2,3,4. Critical fluctuations of the suppressed ordered state are assumed to play a central role for emergent superconductivity and a dome-shaped superconducting state, e.g., upon doping or pressure, is considered a hallmark for unconventional superconductivity2,5,6,7. Among others, charge-density-wave (CDW) order, a periodic modulation of the charge carrier density accompanied by a periodic lattice distortion, often coexists or competes with superconductivity, e.g., in copper-oxide superconductors2,8,9,10 and transition-metal-based kagome metals11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

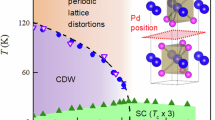

In metallic transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), CDW order stabilized by electron–phonon coupling (EPC) is widespread18,19,20 and it is now evident that many TMDs feature an emergent superconducting state once CDW is sufficiently suppressed21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 following the generic phase diagram shown in Fig. 1. Applying the above described picture to metallic TMDs, electron-phonon coupling carried by a soft phonon mode simultaneously drives the CDW phase transition at finite temperatures and mediates superconductivity once the CDW is suppressed to its QCP. Yet, prototypical CDW-hosting TMDs like 2H-NbSe2 do not reflect this scenario34,35,36,37,38 or feature more complex underlying microscopic mechanisms such as 1T-TiSe228,31.

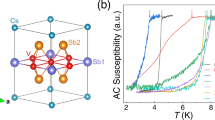

Here, we identify the prototypical TMD 2H-TaSe2 as a paradigm for the above discussed interrelation between a CDW QCP and emergent superconductivity. Employing high-pressure X-ray diffraction (XRD) and inelastic X-ray scattering (IXS), we study the evolution of the crystal structure, CDW order and its associated soft phonon mode under pressure up to 30 GPa and down to 4 K in 2H-TaSe2. 2H-TaSe2 is a classic CDW compound featuring a large periodic lattice distortion39 and a momentum-dependent energy gap in the electronic band structure in its low-temperature state40,41. It is a layered material [Fig. 2a] for which CDW order with a transition temperature TICDW = 122.3 K was reported in the 1970s42. On cooling through TICDW, 2H-TaSe2 first enters a CDW state with an incommensurate ordering wave vector qICDW = (0.323,0,0) [all wave vectors are given in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.); see “Methods”], which evolves on cooling and reaches the commensurate value qCCDW = (1/3,0,0) at TCCDW ≈ 90 K43. The evolution of CDW order with pressure was previously investigated by lab-based single-crystal XRD up to 5 GPa44 and resistivity23,45 but the CDW QCP has not been explored so far. On the other hand, the superconducting transition temperature of 2H-TaSe2 increases smoothly from Tsc = 0.1 K at ambient pressure to Tsc,max = 8.2 K at 23–27 GPa before it starts to decrease again23. Our combined XRD-IXS study supported by ab initio lattice dynamical calculations demonstrates that 2H-TaSe2 features a CDW QCP at pc = 19.9(1) GPa in vicinity of Tsc,max and, thus, represents a clear example for order-suppressed enhanced superconductivity near a CDW QCP.

a Hexagonal high-temperature structure of 2H-TaSe2 (P63/mmc, #194). Lines indicate the unit cell (a = b = 3.425 Å, c = 12.57 Å). b Schematics of a diamond anvil cell and scattering geometry used for the HP-LT XRD experiments. c Observed x-ray diffraction patterns for a 2H-TaSe2 single crystal at T = 40 K and p = 0.3 GPa shown for a (HK0) plane. The blue rectangle highlights the section for which results of a more detailed analysis are shown in Fig. 4. The blue arrow indicates spurious Bragg scattering from the diamond single crystals.

Results

Our focus is on the structural evolution and, in particular, that of CDW order in 2H-TaSe2 under pressure, addressing the question whether a CDW QCP exists close to Tsc,max. We performed synchrotron XRD at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, see Methods for more details) at pressures up to 30 GPa and temperatures down to 10 K. The setup of the high-pressure diamond-anvil cell (DAC) is sketched in Fig. 2b where helium gas was used as pressure medium in a steel gasket. A typical 2D slice of the data set taken at T = 40 K and p = 0.3 GPa [Fig. 2c] reveals the main Bragg reflections of the hexagonal lattice (large dark spots) accompanied by commensurate CDW peaks along the equivalent high-symmetry directions <100>, <010> and <−110>. The CDW peaks divide the line between two hexagonal reciprocal lattice points in three equally large sections [inset in Fig. 2c]. Thus, in agreement with previous works39,42,43,44, we find a commensurate CDW ordering wave vector, qCCDW = (1/3,0,0), at low temperatures and low pressures.

In total we measured more than 120 different temperature-pressure points (see Supplementary Fig. 1) and found that the observed Bragg reflections can always be best indexed using the high-temperature hexagonal unit cell and the structure described in space group P63/mmc [Fig. 2a]. The corresponding refined structural parameters (not considering the CDW superlattice peaks) are detailed in Table 1 for selected temperatures at low and high pressures. Results for all data points are available46 along with raw data and crystallographic information files of the measurements shown in Table 1.

Furthermore, we present a full refinement of the commensurate CDW structure at T = 40 K and p = 0.3 GPa. The commensurate CDW unit cell represents a 3×3×1 supercell of the high temperature structure maintaining its P63/mmc space group (see Table 1). Figure 3 shows the commensurate CDW hexagonal supercell with the atomic Wyckoff positions and site symmetries of the undistorted high-temperature structure. Deviations of the atomic coordinates in the commensurate CDW state are indicated by arrows for each atomic Wyckoff position. The Ta displacements are strictly in the a-b plane whereas some Se atoms show deviations from their position in the high-temperature hexagonal unit cell also along the c axis. The refined distortion validates previous qualitative predictions about the structure in the commensurate CDW phase based on neutron diffraction39 resolving a long-standing debate in 2H-TaSe247,48,49,50.

a Blue and red spheres indicate the positions of Ta and Se ions, respectively, in an undistorted 3 × 3 × 1 supercell of the high-temperature structure for a view along the a axis. The arrows indicate the displacement of each ion in the supercell as determined by our refinement. The Ta displacements were upscaled by a factor of 10 with regard to those of Se for visibility. b View along c axis for upper TaSe2 sandwich layer. c View along c axis for lower TaSe2 sandwich layer.

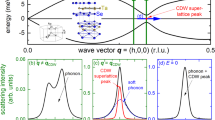

Having established the general structural properties of 2H-TaSe2, we turn to a detailed analysis of the CDW superlattice peak. We exemplify this analysis on data taken along Q = (1,0,0)–(2,0,0) and T = 40 K for pressures up to 20 GPa [Fig. 4a]. The pressure evolution of the superlattice peak at Q ≈ (1.33,0,0) illustrates an intriguing behavior [Fig. 4b]: starting with the commensurate value at low pressures (blue), the CDW wave vector qCDW = (1/3-δ,0,0) acquires a finite incommensuration δ ≈ 0.0015 r.l.u. above 1 GPa (orange) and becomes commensurate again for pressures above 5 GPa (green) up to 8.6 GPa. At pressures p > 10 GPa we find a strongly incommensurate CDW order with δmax = 0.023 (red). Whereas the intensity of the CDW superlattice peak is fairly constant a lower pressures, it reduces strongly in the high-pressure incommensurate state indicating a strong decrease of the atomic displacements associated with CDW order. At 18.2 GPa and T = 40 K (purple), we only find a broad hump of scattered intensity near Q = (1.31,0,0) with a weak intensity reduced by more than two orders of magnitude. The full pressure dependence of the CDW incommensuration δ and the peak width along with refined structural parameters of the high-temperature crystal structure are shown in Fig. 4c–f. The evolution of the CDW peak linewidth reveals a critical pressure at T = 40 K of around 18 GPa (vertical dashed line). We do not find a response in the structural parameters [Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3] to the suppression of CDW order nor to the onset of the strong incommensuration. XRD measurements at T = 10 K were done for pressures up to 15 GPa and near 23 GPa where we found that the CDW order is already suppressed. We complemented our results near 20 GPa by elastic momentum scans at T = 10 K performed on the ID28 IXS spectrometer located at ESRF, France. Here, scans with zero energy transfer across the CDW superlattice peak at Q = (2.64,0,1) (see Supplementary Fig. 4) define the critical pressure of the CDW order in 2H-TaSe2 at this temperature to be between 19.7 GPa and 20 GPa, i.e., pc = 19.9(1) GPa.

a Line scan extracted for Q = (1,0,0)–(2,0,0) [blue box in Fig. 2b, wave vectors Q/q are given in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.)]. Note that intensities are shown on a logarithmic scale. b Line scans through the charge-density-wave (CDW) superlattice peak at Q ≈ (1.33,0,0) for T = 40 K and various pressures p = 0.3–18.2 GPa. A constant background was subtracted. Data for 18.2 GPa was multiplied by a factor of 240 for visibility. The vertical dashed line denotes the position of the commensurate CDW, qCCDW = (1/3,0,0). Data at p = 18.2 GPa were taken with a higher flux than those at lower pressures (see text for details). Error bars in (a, b) represent one standard deviation and are smaller than the symbol size except for the scaled data in (b) taken at p = 18.2 GPa (purple symbols). c Lattice parameters (P63/mmc), d z parameter (of Se atomic position in high-temperature unit cell), e incommensurability δ [defined by the superlattice peak position at qCDW = (1/3-δ,0,0)] and f linewidth of the superlattice peak ΓFWHM shown as a function of pressure for T = 40 K. The horizontal red dashed line in (f) denotes the measured widths of the nearby fundamental reflection, QBragg = (1,0,0) and, thus, represents the resolution limit. Error bars in (c, d) are uncertainties derived within the CrysAlis-PRO software77. Error bars in (e, f) represent uncertainties from the peak fitting process shown in (b). The vertical dashed line denotes the critical pressure at T = 40 K, pc,T=40K ≈ 18 GPa, defined by the increase of ΓFWHM to above the resolution limit.

Summarizing the above described results, we show the temperature-pressure CDW phase diagram of 2H-TaSe2 in Fig. 5a complemented by pressure-dependent superconducting transition temperatures taken from ref. 23. Here, the absence or presence of long-range CDW order and whether it is commensurate or incommensurate has been determined for each investigated point of the phase diagram [blue/red dots in Fig. 5a] in analogy to the analysis of the pressure dependence at T = 40 K presented in detail in Fig. 4 and discussed above. The presence of resolution-limited CDW superlattice peaks has been taken as the main criterion for CDW order [see Fig. 4f]. A vanishing or finite value of the incommensuration δ [see Fig. 4e] was taken as evidence for a commensurate or incommensurate CDW order, respectively. The incommensurate CDW state is suppressed continuously from 122 K at ambient pressure to zero just below 20 GPa near the maximum of Tsc23. We assign the discrepancy of about 5 GPa between pc and the reported pressure range of Tsc,max to the use of a different pressure medium where the different pressure values can also be compared in the derived CDW transition temperatures. Freitas et al.23 report TCDW ≈ 80 K at p = 20 GPa. In our experiments using helium as the most hydrostatic pressure medium, TCDW ≈ 80 K is observed at 15 GPa, i.e., 5 GPa below the corresponding critical pressure, pc = 19.9(1) GPa [Fig. 5a]. Thus, our results for pressures of 15–20 GPa correspond to results published by Freitas et al.23 at pressures from 20 to 25 GPa. Therefore, we conclude that the CDW QCP of 2H-TaSe2 is close to the pressure of Tsc,max.

a Temperature–pressure phase diagram of 2H-TaSe2 derived from x-ray diffraction experiments. Blue (red) dots indicate the (T,p) points at which XRD (elastic IXS) measurements were performed. The blue/gray solid lines are guides to the eye for the pressure dependence of the TICDW/TCCDW crossover and pass between investigated temperature–pressure points (blue/red dots) for which we do or do not observe a superlattice peak (blue line) or do observe a commensurate or incommensurate CDW ordering wave vector qCDW (gray line). In regions of the phase diagram, where ICDW-CCDW crossover is not precisely known due to the limited number of points we could investigate with XRD, we show the evolution of TCCDW as gray-dashed line. The color-code reflects the deduced values of the incommensurability δ of the CDW ordering wave vector qCDW = (1/3-δ,0,0) [wave vectors Q/q and δ are given in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.)]. Open circles represent the superconducting transition temperature Tsc reported in ref. 23. b Energy of the CDW soft phonon mode deduced from our high-pressure IXS measurements at T = 4 K (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for details). Error bars are deduced from the peak fitting procedure outlined in Supplementary Fig. 5. c Calculated square phonon energy of the soft phonon mode in 2H-TaSe2 based on density-functional-perturbation theory (DFPT, black symbols, left-hand scale). Pressure effects were included using the experimental lattice parameters observed in XRD at T = 40 K. The vertical dashed (blue) line indicates the pressure pc,DFPT = 18.8 GPa, for which a linear fit of the square phonon energy (dashed line) crosses zero. Calculations including electron–phonon coupling for p > pc,DFPT predict a superconducting Tsc,DFPT = 11.8 K just above pc,DFPT, which decreases for higher pressures (green symbols, right-hand scale).

The low-temperature commensurate CDW order is gradually suppressed at low-pressures though CDW order at T = 10 K stays commensurate at all investigated pressures up to 5 GPa (solid gray line, in agreement with previous reports45). At T = 40 K, CDW superlattice peaks are found at commensurate positions again for pressures 5 GPa ≤ p ≤ 8.6 GPa. The presence of the reentrant commensurate CDW state is in qualitative agreement with previous reports, though quantitatively we find the onset at higher pressure than reported in 198044. Again, the use of a different pressure medium, i.e., methanol-ethanol mix, and pressure calibration only at room temperature44 can explain such discrepancies. In regions where we did not perform a dense set of XRD measurements, we indicate the evolution of TCCDW at the mid-points between measurements featuring commensurate and incommensurate CDW order (gray dashed lines). Our results for pressures above 5–6 GPa qualitatively differ from a tentative phase diagram proposed by Freitas et al.23. Here it is important to note that the electrical transport data presented in ref. 23 do not include information about the interplay of the commensurate and incommensurate CDW order in 2H-TaSe2 but only generally determine the suppression of TCDW from 122 K at ambient pressure to 80 K at 20 GPa. The presented sketch of the phase diagram regarding commensurate and incommensurate CDW order is based on previous work reporting results from electrical transport45 and XRD44 but only up to pressures up to 1.8 and 4.5 GPa, respectively. Thus, the detailed phase diagram regarding the interplay of commensurate and incommensurate CDW order at pressures p ≥ 5 GPa was so far unknown for 2H-TaSe2 and represents an important part of our study.

One requirement for a quantum critical point is that the suppressed phase transition is continuous, i.e., of second order. The presence of a soft phonon mode indicates a second-order phase transition and, therefore, we employed IXS to check the evolution of the CDW soft phonon (previously investigated at ambient pressure38) at high pressures and low temperatures. A full report of the inelastic scattering experiments will be published elsewhere. The low-temperature pressure-dependent phonon energy of the same mode studied at ambient pressure38 confirms its soft-mode character in the vicinity of pc [Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5] and is evidence that the suppressed phase transition remains continuous. Thus, we conclude that 2H-TaSe2 features a CDW QCP at pc = 19.9(1) GPa.

Detailed lattice dynamical calculations can assess not only the phonon dispersions in a material but also the strength of EPC and provide an estimate of the corresponding superconducting transition temperature. In a recent publication38, we have shown that calculations using the hexagonal high-temperature structure confirm the suppression of the CDW phonon instability at a pressure of 23 GPa. The calculated EPC, which is mostly confined to the original CDW soft phonon mode in 2H-TaSe2, can explain superconducting transition temperatures of about 10 K. Here, we present a more detailed set of calculations, where pressure is included by using the refined crystal structure deduced from our XRD measurements. Figure 5c shows the calculated square of the CDW soft mode energy as function of pressure (gray symbols). Negative values at lower pressures indicate an imaginary frequency of the CDW soft phonon mode and, thus, the formation of a CDW superstructure. On the other hand, the positive values of the calculated square phonon energies of the CDW soft mode show that the ambient-pressure high-temperature structure [see illustration in Fig. 2a] is stable at low-temperature for pressures larger than pc,DFPT = 18.8 GPa [gray symbols in Fig. 5c]. Thus, the calculated critical pressure of the CDW state is quite close to the observed value of pc = 19.9 GPa.

We computed the full phonon dispersion spectrum and the corresponding EPC for stable structures above pc,DFPT (see Fig. 6 in ref. 38 for p = 23 GPa). To estimate Tsc at high pressures, we solved the linearized gap equation of the Eliashberg theory on the imaginary axis51. This equation takes as input the Eliashberg function \({\alpha }^{2}F\left(\omega \right)\). The contribution of a phonon mode with energy \({\omega }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}{{{\rm{\lambda }}}}}\) and a linewidth due to EPC of \({\gamma }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}{{{\rm{\lambda }}}}}\) to \({\alpha }^{2}F\left(\omega \right)\) is given by the ratio \({\gamma }_{{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}\lambda }/{\omega }_{{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}\lambda }\). For the CDW soft mode this ratio is largest at the CDW QCP since \({\omega }_{{{{\bf{q}}}}{{{\rm{\lambda }}}}}\) is practically zero [see gray symbols in Fig. 5c]. At larger pressures, the energy of the soft mode will harden, its contribution to \({\alpha }^{2}F\left(\omega \right)\) will decrease and, thus, we expect a decreasing superconducting transition temperature if the EPC is mainly mediated by the soft mode. The only other parameter in estimating Tsc is \({\mu }^{* }\), which represents an effective Coulomb repulsion52. Using a typical value of \({\mu }^{* }=0.1\), we get a maximum Tsc.max = 11.9 K at pc,DFPT = 18.8 GPa [green symbols in Fig. 5c]. The low-energy modes including the soft branch contribute 73% to the total coupling constant \({{{{\rm{\lambda }}}}}_{{{{\rm{EPC}}}}}=1.03\). When ignoring this contribution, Tsc,DFPT is zero. Including the full strength of EPC for pressures p ≥ 18.8 GPa, the pressure dependence of Tsc,DFPT is negative though the reduction is small, i.e., ΔTsc = 1.7 K for Δp = 5 GPa [green symbols in Fig. 5c], in reasonable agreement with the published results23. Thus, the opposite trends in the pressure dependences of the soft-mode energy and Tsc [see Fig. 5c] agree with the above outlined scenario and our calculations support the scenario that order-parameter fluctuations represented by the CDW soft phonon mode mediate emergent superconductivity in 2H-TaSe2.

Discussion

Emergent superconductivity in the vicinity of an ordered state is a central topic of research in many quantum materials such as the cuprates, iron-based superconductors and kagome metals. Particularly, the role of order-parameter fluctuations of the suppressed state is intensely investigated. The question remains whether these fluctuations promote the superconducting pairing. The answer is “yes” for 2H-TaSe2. The phase diagram shows that, in contrast to previous suggestions23, the incommensurate CDW state is continuously suppressed and reaches zero temperature in close vicinity to Tsc,max [see Fig. 5a]. The observed soft-mode behavior confirms that the transition stays second order [see Fig. 5b] and, therefore, a CDW QCP in 2H-TaSe2 exists at high pressure. The estimated Tsc,DFPT crucially depends on the low-energy EPC. Moreover, our calculations explain the broad pressure dependence of Tsc and show that Tsc,max is tied to the CDW QCP [see Fig. 5c]. Our results for 2H-TaSe2 are similar to results of electrical transport experiments in intercalated 2H-Pd0.05TaSe2 reporting the pressure dependence of CDW order and superconductivity33. Yet, only our measurements provide detailed insights about the CDW order like its incommensuration. Furthermore, we observed the CDW transition down to just above the superconducting transition temperature whereas the pressure dependence of TCDW in 2H-Pd0.05TaSe2 was established from 120 K at ambient pressure down to only 45 K at 20.5 GPa. The CDW critical pressure was then extrapolated to be close to 21.5 GPa for which Tsc,max ≈ 8 K is reported.

The straightforwardness of EPC by which Tsc,max is linked to the CDW QCP in 2H-TaSe2, and likely in 2H-Pd0.05TaSe2 as well, contrasts with other CDW-hosting TMDs behaving differently. For instance, incommensurate CDW order in isostructural 2H-NbSe2 is suppressed near 4.4 GPa31 but Tsc,max occurs close to 10 GPa28. Moreover, harmonic calculations overestimate the CDW critical pressure by about a factor of three36. Differences between 2H-NbSe2 and 2H-TaSe2 with respect to the lattice dynamical properties are a strong lattice anharmonicity in the former compound which causes the relatively low CDW ordering transition temperature of TCDW,NbSe2 = 33 K35,36. Furthermore, EPC calculations reveal that the CDW soft phonon mode contributes less than 10% to the overall EPC strength in 2H-NbSe236. Thus, a softening of the CDW soft phonon mode at the CDW critical pressure would have only a small impact on the overall evolution of Tsc and other pressure induced changes of the electronic structure might be more important. In fact, the presence of a CDW QCP in 2H-NbSe2 at 4.4 GPa has been questioned recently based on a very sharp drop of TCDW near the critical pressure interpreted as signature for a first-order transition31 though other reports consider it to be second order53.

Similarly, 1T-TiSe2 has been intensively studied under pressure30,32,54,55,56. The most recent work32 points towards the presence of a CDW QCP in that a superconducting dome was reported around the CDW critical pressure near 5 GPa32. Yet, the same study also reports on significant and sudden changes in the electronic band structure at 2 GPa, just before superconductivity sets in. Thus, superconductivity might be mediated by the pressure-induced electronic bands of the Fermi surface not related to the CDW order at ambient pressure. Whether and how the CDW and superconducting states in 1T-TiSe2 interact needs further investigation.

Researchers have investigated thin films of TMDs down to the single-(sandwich-)layer limit. Interestingly, Tsc is reduced in thin NbSe221,22,23,24,25,26 whereas it increases in TaSe2 by a factor of up to ten57,58. Recent theoretical work50 proposes that the CDW structure in single-layer TaSe2 may be different from the one originally proposed39. Here, our definitive structural refinement of the bulk commensurate CDW state in agreement with the original proposal provides an important starting point to understand these contrasting properties59,60,61 and benchmark calculations in the bulk limit.

Thus, 2H-TaSe2 under pressure is a clear example of order-parameter-fluctuation enhanced superconductivity at a QCP and can serve as starting point to improve our understanding of more complex CDW materials such as kagome metals17,62, nickel-based 122-pnictides63,64 or high-TC cuprates8,9,65.

For instance, the kagome system CsV3Sb5 shows a roughly similar temperature-pressure phase diagram featuring CDW and superconducting states with similar maximum transition temperatures of 90 K (p = 0) and 8 K (p ≈ 2 GPa), respectively66, as 2H-TaSe2. A crossover between two differently ordered CDW states on increasing pressure is discussed as origin of a peculiar double-peak structure in Tsc(p) with explicit reference to the commensurate and incommensurate CDW phases in 2H-TaSe266,67. According to our results, the low-temperature state of 2H-TaSe2 is commensurate up to a pressure of about 8.6 GPa [see Figs. 4e and 5a]. At higher pressures, a strong incommensurability develops accompanied by a large drop of the CDW superlattice peak intensity [see Fig. 4b]. However, Tsc was not measured near this commensurate to incommensurate CDW crossover. It will be interesting to re-examine Tsc(p) more closely to investigate how sensitively superconductivity responds to changes of the charge order in a model material such as 2H-TaSe2. We note that experiments in CsV3Sb5 so far did not observe a CDW soft phonon mode16,68,69. Theory emphasizes anharmonic phonon properties70, yet predicts that EPC is large enough to mediate the observed superconducting transition temperatures71.

Discussions on the interplay of CDW order and superconductivity have been revived by the discovery of CDW states in cuprates8,9,10,65, in which CDW peak intensities are suppressed upon entering the superconducting state, regardless of whether it is a medium8 or long-range ordered CDW65,72. In 2H-NbSe2, the CDW peak intensity is not or only slightly reduced below Tsc73, reflecting a rather independent coexistence of the two states. 2H-TaSe2 under pressure provides the possibility to investigate the CDW-superconductivity phase competition in a clean system where both states are strongly linked to the soft-phonon mode. Conventional superconductivity can only be mediated by EPC, not gapped out by CDW order. A decrease of TCDW with pressure indicates that the CDW gap is decreasing, too, and, thus, more electronic states with strong EPC are available for superconductivity. However, whether the CDW order parameter, measured by the intensity of its superlattice peaks, is reduced for T < Tsc in 2H-TaSe2 remains an interesting question for future experiments.

Methods

X-ray diffraction

XRD experiments at high-pressure and low-temperature were performed at the ESRF (beamline ID15B74) in a membrane-type DAC using the ruby fluorescence method for the pressure calibration75. For the experiments at the ESRF an ESRF-made Le Toullec–type CuBe-alloy DAC with diamonds with cullet diameters of 500 μm was used. A stainless-steel gasket was indented down to a thickness of about 100 μm. A 2H-TaSe2 single crystal and one ruby were placed inside the gasket hole, and helium was used as the pressure-transmitting medium. The 2H-TaSe2 sample was a small piece cut from the same single crystal as the samples for IXS and grown at Kiel University (see ref. 38). A sketch of the DAC setup are shown in Fig. 2b. For XRD a monochromatic beam with an energy of 30.17 keV (≈0.411 Å) was focused down to 4 × 4 μm2, and the diffracted beam was detected with an EIGER2 X 9M CdTe flat panel detector. For each dataset images within an angular range of ±32◦ were recorded. Each image was integrated for 0.2 s and over a 0.5° rotation. The detector position and distance (180 mm) were calibrated with silicon powder and an enstatite single-crystal standard using the DIOPTAS76 and CrysAlis-PRO softwares77. CrysAlis-PRO77 was used for cell refinement, data reduction, and the analysis of the diffraction precession images for all datasets. SHELLXS9778 and SHELLXL97 2014/779 as well as JANA200680 were used to solve the crystal structure and refinements. Crystal data and structural refinement details for selected measurements are summarized in Table 1. An extended table is available electronically46. The single crystal X-ray crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2415237-2415239. Atomic coordinates and site labels were standardized using the VESTA81 crystal structure visualization software.

Inelastic x-ray scattering

IXS experiments at high-pressure and low-temperature were carried out at the beamline ID2882 at the ESRF (France). The sample was a small piece cut from the same single crystal as the samples for XRD and grown at Kiel University (see ref. 38). The high-pressure low-temperature setup was the same as used on high-pressure XRD on beamline ID15b at ESRF (see above). Phonon excitations measured in constant-momentum scans were approximated by damped harmonic oscillator (DHO) functions83 convoluted with a pseudo-Voigt resolution function [full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) = 1.4 meV, Lorentz ratio = 0.74]. The resolution function was further used to approximate resolution-limited elastic scattering at zero energy transfer. Measurements were done at scattering wave vectors Q = τ − q, where τ is a reciprocal lattice vector and q is the reduced wave vector in the first Brillouin zone. Wave vectors are expressed in reciprocal lattice units (r.l.u.) \((2\pi /a,\,2\pi /b,\,2\pi /c)\) with the lattice parameters \(a=b\approx 3.44\,{{{\text{\AA }}}}\) and \(c\approx 12.7\,{{{\text{\AA }}}}\) of the high-temperature hexagonal unit cell [#194, Fig. 2a]. All IXS measurements were done in the Brillouin zone adjacent to \({{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}}=(3,0,1)\).

Ab initio lattice dynamical calculations

Ab initio lattice dynamical calculations based on density-functional-perturbation-theory (DFPT) were performed in the framework of the mixed basis pseudopotential method42. The exchange-correlation functional was treated in the local-density approximation (LDA). Spin-orbit interaction was taken into account consistently. More details are given in Supplementary Note 4 of ref. 38. Pressure dependent properties were calculated by using corresponding lattice parameters deduced from XRD at T = 40 K. The internal parameter z was relaxed.

Code availability

Information on the ab initio calculations are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Fernandes, R. M. et al. Iron pnictides and chalcogenides: a new paradigm for superconductivity. Nature 601, 35–44 (2022).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179–186 (2015).

Schuberth, E. et al. Emergence of superconductivity in the canonical heavy-electron metal YbRh2Si2. Science 351, 485–488 (2016).

Frank, S. & Steffen, W. Foundations of heavy-fermion superconductivity: lattice Kondo effect and Mott physics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 084502 (2016).

Fernandes, R. M., Chubukov, A. V. & Schmalian, J. What drives nematic order in iron-based superconductors? Nat. Phys. 10, 97–104 (2014).

Damascelli, A., Hussain, Z. & Shen, Z.-X. Angle-resolved photoemission studies of the cuprate superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 473–541 (2003).

Mathur, N. D. et al. Magnetically mediated superconductivity in heavy fermion compounds. Nature 394, 39 (1998).

Ghiringhelli, G. et al. Long-range incommensurate charge fluctuations in (Y,Nd)Ba2Cu3O6+x. Science 337, 821–825 (2012).

Le Tacon, M. et al. Inelastic X-ray scattering in YBa2Cu3O6.6 reveals giant phonon anomalies and elastic central peak due to charge-density-wave formation. Nat. Phys. 10, 52–58 (2014).

Blackburn, E. et al. Inelastic x-ray study of phonon broadening and charge-density wave formation in ortho-II-ordered YBa2Cu3O6.54. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054506 (2013).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. New kagome prototype materials: discovery of KV3Sb5, RbV3Sb5, and CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 094407 (2019).

Jiang, Y.-X. et al. Unconventional chiral charge order in kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat. Mater. 20, 1353–1357 (2021).

Liang, Z. et al. Three-dimensional charge density wave and surface-dependent vortex-core states in a kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031026 (2021).

Xie, Y. et al. Electron-phonon coupling in the charge density wave state of CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 105, L140501 (2022).

Subires, D. et al. Order-disorder charge density wave instability in the kagome metal (Cs,Rb)V3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 14, 1015 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Observation of unconventional charge density wave without acoustic phonon anomaly in kagome superconductors AV3Sb5 (A=Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. X 11, 031050 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity under pressure in a chromium-based kagome metal. Nature 632, 1032–1037 (2024).

Rossnagel, K. On the origin of charge-density-waves in select layered transition-metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 213001 (2011).

Johannes, M. D. & Mazin, I. I. Fermi surface nesting and the origin of charge density waves in metals. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165135 (2008).

Hwang, J. et al. Charge density waves in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Rep. Prog. Phys. 87, 044502 (2024).

Kogar, A. et al. Observation of a charge density wave incommensuration near the superconducting dome in CuxTiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 027002 (2017).

Morosan, E. et al. Superconductivity in CuxTiSe2. Nat. Phys. 2, 544–550 (2006).

Freitas, D. C. et al. Strong enhancement of superconductivity at high pressures within the charge-density-wave states of 2H-TaS2 and 2H-TaSe2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 184512 (2016).

Berthier, C., Molinié, P. & Jérome, D. Evidence for a connection between charge density waves and the pressure enhancement of superconductivity in 2H-NbSe2. Solid State Commun. 18, 1393–1395 (1976).

Liu, X., Chong, Y. X., Sharma, R. & Davis, J. C. S. Discovery of a Cooper-pair density wave state in a transition-metal dichalcogenide. Science 372, 1447–1452 (2021).

Sanna, A. et al. Real-space anisotropy of the superconducting gap in the charge-density wave material 2H-NbSe2. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 6 (2022).

Lee, H. N. S., McKinzie, H., Tannhauser, D. S. & Wold, A. The low-temperature transport properties of NbSe2. J. Appl. Phys. 40, 602–604 (1969).

Suderow, H., Tissen, V. G., Brison, J. P., Maartinez, J. L. & Vieira, S. Pressure induced effects on the Fermi surface of superconducting 2H-NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 117006 (2005).

Sipos, B. et al. From Mott state to superconductivity in 1T-TaS2. Nat. Mater. 7, 960–965 (2008).

Kusmartseva, A., Sipos, B., Berger, H., Forró, L. & Tutiš, E. Pressure induced superconductivity in pristine 1T-TiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 236401 (2009).

Moulding, O., Osmond, I., Flicker, F., Muramatsu, T. & Friedemann, S. Absence of superconducting dome at the charge-density-wave quantum phase transition in 2H-NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043392 (2020).

Hinlopen, R. D. H. et al. Lifshitz transition enabling superconducting dome around a charge-order critical point. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl3921 (2024).

Sur, Y. et al. Enhanced superconductivity near a pressure-induced quantum critical point of strongly coupled charge density wave order in 2H-Pd0.05TaSe2. NPG Asia Mater. 17, 8 (2025).

Weber, F. et al. Extended phonon collapse and the origin of the charge-density wave in 2H-NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 107403 (2011).

Flicker, F. & van Wezel, J. Charge order from orbital-dependent coupling evidenced by NbSe2. Nat. Commun. 6, 7034 (2015).

Leroux, M. et al. Strong anharmonicity induces quantum melting of charge density wave in 2H-NbSe2 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 92, 140303 (2015).

Diego, J. et al. van der Waals driven anharmonic melting of the 3D charge density wave in VSe2. Nat. Commun. 12, 598 (2021).

Shen, X. et al. Precursor region with full phonon softening above the charge-density-wave phase transition in 2H-TaSe2. Nat. Commun. 14, 7282 (2023).

Moncton, D. E., Axe, J. D. & DiSalvo, F. J. Neutron scattering study of the charge-density wave transitions in 2H-TaSe2 and 2H-NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 16, 801–819 (1977).

Rossnagel, K., Rotenberg, E., Koh, H., Smith, N. V. & Kipp, L. Fermi surface, charge-density-wave gap, and kinks in 2H-TaSe2. Phys. Rev. B 72, 121103 (2005).

Borisenko, S. et al. Pseudogap and charge density waves in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 196402 (2008).

Moncton, D. E., Axe, J. D. & DiSalvo, F. J. Study of superlattice formation in 2H-NbSe2 and 2H-TaSe2 by neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 734–737 (1975).

Leininger, P., Chernyshov, D., Bosak, A., Berger, H. & Inosov, D. S. Competing charge density waves and temperature-dependent nesting in 2H-TaSe2. Phys. Rev. B 83, 233101 (2011).

McWhan, D. B., Fleming, R. M., Moncton, D. E. & DiSalvo, F. J. Reentrant lock-in transition of the charge-density wave in 2H-TaSe2 at high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 269–272 (1980).

Chu, C. W., Testardi, L. R., Di Salvo, F. J. & Moncton, D. E. Pressure effects on the charge-density-wave phases in 2HTaSe2. Phys. Rev. B 14, 464–467 (1976).

Tymoshenko, Y. et al. CDW quantum critical point under pressure in 2H-TaSe2. KITopen data repository. https://doi.org/10.35097/crad209kjcxvvnkc (2025).

Fung, K. K., McKernan, S., Steeds, J. W. & Wilson, J. A. Broken hexagonal symmetry in the locked-in state of 2Ha-TaSe2 and the discommensurate microstructure of its incommensurate CDW states. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 14, 5417 (1981).

Littlewood, P. & Rice, T. Theory of the splitting of discommensurations in the charge-density-wave state of 2H-TaSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 27–30 (1982).

Doran, N. J. & Wooley, A. M. The structure of the commensurate charge density wave in 2H-TaSe2 from bandstructure energy calculations. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 16, L675 (1983).

Lian, C.-S. et al. Coexistence of superconductivity with enhanced charge density wave order in the two-dimensional limit of TaSe2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 4076–4081 (2019).

Bergmann, G. & Rainer, D. The sensitivity of the transition temperature to changes in α2F(ω). Z. Phys. 263, 59–68 (1973).

Heid, R., Bohnen, K.-P. & Renker, B. Electron-phonon coupling and superconductivity in MgB2 and related diborides. Adv. Solid State Phys. 42, 293–305 (2002).

Feng, Y. et al. Itinerant density wave instabilities at classical and quantum critical points. Nat. Phys. 11, 865–871 (2015).

Joe, Y. I. et al. Emergence of charge density wave domain walls above the superconducting dome in 1T-TiSe2. Nat. Phys. 10, 421–425 (2014).

Maschek, M. et al. Superconductivity and hybrid soft modes in 1T-TiSe2. Phys. Rev. B 94, 214507 (2016).

Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Charge-density wave and superconducting dome in TiSe2 from electron-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 196406 (2011).

Galvis, J. A. et al. Scanning tunneling measurements of layers of superconducting 2H-TaSe2: evidence for a zero-bias anomaly in single layers. Phys. Rev. B 87, 094502 (2013).

Wu, Y. et al. Dimensional reduction and ionic gating induced enhancement of superconductivity in atomically thin crystals of 2H-TaSe2. Nanotechnology 30, 035702 (2019).

Lin, D. et al. Patterns and driving forces of dimensionality-dependent charge density waves in 2H-type transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 11, 2406 (2020).

Wickramaratne, D., Khmelevskyi, S., Agterberg, D. F. & Mazin, I. I. Ising superconductivity and magnetism in NbSe2. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041003 (2020).

Das, S., Paudyal, H., Margine, E. R., Agterberg, D. F. & Mazin, I. I. Electron-phonon coupling and spin fluctuations in the Ising superconductor NbSe2. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 66 (2023).

Jiang, K. et al. Kagome superconductors AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwac199 (2022).

Yao, Y. et al. An electronic nematic liquid in BaNi2As2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4535 (2022).

Souliou, S. M. et al. Soft-phonon and charge-density-wave formation in nematic BaNi2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 247602 (2022).

Kim, H.-H. et al. Uniaxial pressure control of competing orders in a high-temperature superconductor. Science 362, 1040–1044 (2018).

Yu, F. H. et al. Unusual competition of superconductivity and charge-density-wave state in a compressed topological kagome metal. Nat. Commun. 12, 3645 (2021).

Stier, F. et al. Pressure-dependent electronic superlattice in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 236503 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Observation of anomalous amplitude modes in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 13, 3461 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Absence of phonon softening across a charge density wave transition due to quantum fluctuations. Proc. Acad. Natl. Sci. USA 122, e2507135122 (2025).

Gutierrez-Amigo, M. et al. Phonon collapse and anharmonic melting of the 3D charge-density wave in kagome metals. Commun. Mater. 5, 234 (2024).

Zhong, Y. et al. Testing electron–phonon coupling for the superconductivity in kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 14, 1945 (2023).

Gerber, S. et al. Three-dimensional charge density wave order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at high magnetic fields. Science 350, 949–952 (2015).

Du, C. H. et al. X-ray scattering studies of 2H-NbSe2, a superconductor and charge density wave material, under high external magnetic fields. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 12, 5361–5370 (2000).

Garbarino, G. et al. Extreme conditions X-ray diffraction and imaging beamline ID15B on the ESRF extremely brilliant source. High Press. Res. 44, 199–216 (2024).

Syassen, K. Ruby under pressure. High Press. Res. 28, 75–126 (2008).

Prescher, C. & Prakapenka, V. B. DIOPTAS: a program for reduction of two-dimensional X-ray diffraction data and data exploration. High Press. Res. 35, 223–230 (2015).

CrysAlis PRO. https://www.agilent.com (Agilent Technologies Ltd, Yarnton, Oxfordshire, England, 2014).

Sheldrick, G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 64, 112–122 (2008).

Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 71, 3–8 (2015).

Petříček, V., Dušek, M. & Palatinus, L. Crystallographic computing system JANA2006: general features. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 229, 345 (2014).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 653–658 (2008).

Said, A. H. et al. High-energy-resolution inelastic X-ray scattering spectrometer at beamline 30-ID of the Advanced Photon Source. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 27, 827–835 (2020).

Fåk, B. & Dorner, B. Phonon line shapes and excitation energies. Phys. B Condens. Matter 234-236, 1107–1108 (1997).

Shen, X. et al. Suppression of charge-density wave order in 2H-TaSe2 by pressure. ESRF. https://doi.org/10.15151/ESRF-ES-902987807 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Y.T. was supported within the consortium DAPHNE4NFDI in association with the German National Research Data Infrastructure (NFDI) e.V. NFDI is financed by the Federal Republic of Germany and the 16 federal states and the consortium is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project number 460248799. T.L.L. was supported through the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under project 422213477 (TRR 288 project B03). R.H. acknowledges support by the state of Baden-Württemberg through bwHPC. A.M. was supported by BMBF under contract 05K22VK1 in the framework of ErUM-PRO. X.S. was supported by the Helmholtz-OCPC Postdoc Program. S.R. was supported by the Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. A.H.S. was supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DEAC02-06CH11357. The authors gratefully acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) for time on beamlines ID15b (proposal HC-5083)84 and ID28 (proposal HC-5554).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X-ray diffraction: Y.T., A.-A.H., T.L.L., G.G., M.M., X.S., F.W.; inelastic x-ray scattering: Y.T., A.M., A.I., L.P., A.B., S.R., A.H.S., F.W.; data analysis: Y.T., A.-A.H., F.W.; theory: R.H.; sample growth: K.R., F.K.D.; manuscript: Y.T., A.-A.H., F.W. with comments from all authors; project coordination: F.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tymoshenko, Y., Haghighirad, AA., Heid, R. et al. Charge-density-wave quantum critical point under pressure in 2H-TaSe2. Commun Phys 8, 352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02254-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02254-3