Abstract

Quantum simulation represents a cornerstone application for quantum computers, offering the potential to solve classically intractable problems in physics, chemistry, and materials science. Despite being one of the most accessible simulation methods, the product formula encounters challenges due to the pessimistic gate count estimation. In this work, we elucidate how observable knowledge can accelerate quantum simulations. By focusing on specific knowledge of observables, we reduce product-formula simulation errors and gate counts in both short-time and arbitrary-time scenarios. For short-time simulations, we deliberately design and tailor product formulas to achieve size-independent errors for local and certain global observables. In arbitrary-time simulations, we reveal that Pauli-summation structured observables generally reduce average errors with a typically quadratic error reduction. Our advanced error analyses, supported by numerical studies, indicate improved gate count estimation. We anticipate that the explored speed-ups can pave the way for efficiently realizing quantum simulations and demonstrating advantages on near-term quantum devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum simulation, aimed at mimicking the temporal evolution of quantum systems, stands as one of the most promising applications of quantum computers1. It serves as a reliable tool for investigating quantum many-body physics2,3,4,5,6,7 and quantum field theory8,9. Moreover, it holds profound implications in various fields that seek to uncover the dynamics of systems, including materials science and quantum chemistry10,11,12.

Since Lloyd’s pioneering proposal for digital quantum simulation13, significant efforts have been devoted to developing more efficient simulation algorithms, including families of product formulas14,15,16,17,18, linear combination of unitaries (LCU)19,20,21,22,23, and quantum signal processing (QSP)24,25. Both LCU and QSP approaches achieve linear gate counts in terms of simulation time, scaling optimally as inferred in ref. 16. However, these methods demand numerous ancillary qubits for controlling or block encoding, requiring high-quality multi-qubit gates, which are challenging in near-term quantum computing. In contrast, product-formula simulation involves only short-range quantum gates and empirically requires fewer resources26, making it an accessible choice for realizing simulations in experiments27,28,29,30,31 and achieving quantum advantages in the future.

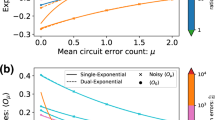

While existing product-formula methods are nearly optimal for certain Hamiltonians32,33, the associated error bounds typically emphasize the worst-case scenarios for states and measurements. This pessimism leads to the resource requirements that far surpass current experimental capabilities26. However, practical settings, especially measurements, are often chosen deliberately, enabling further improvements in error analyses and resource estimations as shown in Fig. 1a. Specific measurement structures are prevalently adopted in simulation due to their simplicity or direct relevance to the underlying physics, such as local observables in studying system scramblings34,35,36,37, and summation observables in magnetization and correlation functions30,31,38,39,40. Recent work7,33,41,42 has depicted these observable-driven advantages in product-formula simulation for some special cases. Nevertheless, there is a missing of a thorough exploration of quantum simulation speed-ups by utilizing specific knowledge of observables.

a Schematic illustrating the benefits of utilizing observable knowledge to analyze simulation errors. The operator-norm distance between unitaries captures the largest error from the worst-case scenario among states and observables (red bracket). Using observable knowledge can significantly reduce simulation errors (orange bracket). b Schematic of advantages at different simulation times within Heisenberg’s picture. In this work, short-time advantages, previously analyzed in ref. 33 for local observables are extended to more general observables. Infinite-time advantages of local observables were observed in ref. 7. Beyond these two special cases, we also explore the observable-driven advantages in the general arbitrary-time simulation by examining average performances with random-input states.

In this work, we comprehensively analyze product-formula simulations by leveraging observable knowledge, uncovering its advantages for both short- and arbitrary-time simulations. Our short-time simulation analyses reveal that the locality of observables generally provides a speed-up. For a single local observable, we delineate its support expansion in a generic product-formula circuit within Heisenberg’s picture. This allows us to design specific product formulas for local observables by removing all irrelevant gates. This method achieves a typical size-independent error and gate count, which surpasses the standard and worst-case analysis in ref. 33. Moreover, locality from global observables, consisting of a sum of local observables, also leads to short-time advantages. To view this, we design a product formula that simultaneously suppresses the expanding supports of all local summand observables, ensuring size-independent errors through a similar support analysis. Given our short-time analyses and the previous infinite-time results7, a natural question arises as in Fig. 1b: do observable advantages persist for arbitrary-time simulations? Although a general analysis remains challenging, we shift our focus to random-input simulations to isolate state effects and identify speed-ups from observable knowledge. Using observable knowledge, our random-input error bound generally guarantees error reductions for observables consisting of a sum of multiple Pauli operators (Pauli-summation observables), significantly improving upon previous analyses that relied on the operator norm43. Specifically, we prove quadratic reductions in average errors proportional to the number of summands for observables with evenly distributed Pauli coefficients.

These improved error analyses suggest more efficient simulation, benefiting practical applications such as observing dynamical quantum phase transitions44,45,46,47, preparing entangled states48,49, and studying qubit-encoded molecular systems11,50,51. We have also exhibited these advantages in specific application studies and numerical evaluations.

Results

Observable advantages for short-time simulations

In this section, we investigate the advantages of short-time product-formula simulation on specific observables. We denote the support of an arbitrary operator A as S(A). Throughout the remainder of the paper, “local operator” refers to the operators acting nontrivially on only a constant number of qubits, i.e., \(| S(A)| ={{\mathcal{O}}}(1)\). For both a local observable and a global observable composed of a sum of local operators, we introduce optimal product formulas that suppress the expansion of observable supports, known as the light cone, resulting in size-independent simulation errors. In this sense, our findings indicate that the locality of observables generally endows better errors for short-time simulation.

To illustrate, we present the general form of a product formula for simulating a generic H,

with decomposition \(H={\sum }_{\gamma = 1}^{\Gamma }{H}_{\gamma }\), and permutation πυ, collectively denoted by configuration. Here, ϒ denotes the stage number, and {a(υ, γ)} are some real coefficients. To simulate a system for a long time t, we conventionally divide the time into r small steps and use \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}^{r}(t/r)\) to approximate the ideal evolution.

Local observables

To explore the advantage of a local observable O, we need a proper configuration to decide the product formula. Given the Pauli decomposition \(H={\sum }_{\alpha \in {{\mathsf{P}}}^{n}}{s}_{\alpha }{P}_{\alpha }\), we introduce the corresponding interactive decomposition and edge sets regarding a support S (shorthand for S(O) due to its frequent use):

where \({P}_{\alpha }\notin {H}_{k-1}^{S}\) indicates that Pα is not included in \({H}_{k-1}^{S}\). Figure 2a exhibits a schematic of \(\{{H}_{k}^{S}\}\) and \(\{{E}_{k}^{S}\}\).

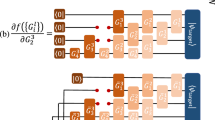

a A general depiction of the edge-set partition and the corresponding interactive decomposition regarding S. Layers signify edge sets \({\{{E}_{k}^{S}\}}_{k}\), with the line between \({E}_{k-1}^{S}\) and \({E}_{k}^{S}\) representing sub-Hamiltonian interactions \({H}_{k}^{S}\) for integer k ≥ 1. b Visualizing the support expansion of the operator O(t) in the second-order Trotter formula circuit. Here, we adopt the interactive decomposition and even-odd permutation. Each colored block represents the matrix exponential, with blue denoting sub-Hamiltonians with even subscripts and red denoting odd ones. Shaded blocks indicate unitaries outside the expanding support of O(t). We only need to implement the effective (bright) blocks, as outlined in Alg. 1. c Illustration of the regrouping and coloring procedure for a two-dimensional nearest-neighbor lattice Hamiltonian. The regrouping preserves nearest-neighbor interactions, with graph edges corresponding to lattice edges. Edges are colored based on their parities along the vertical and horizontal axes.

We find that edge sets determine lower bounds for the expanding support of O(t) evolved under product formulas. This lower bound can be attained by employing the formula with the interactive decomposition \({\{{H}_{k}^{S}\}}_{k}\) and an even-odd permutation defined as:

To elucidate this claim, we define an operation ⊎ between a unitary U and the support S of O as follows:

This operation estimates the largest possible support of UOU†. We then introduce a lemma regarding the expanding support of an evolved operator, with the proof sketched in Methods and formally presented in Supplementary Note 2.

Lemma 1

(Optimal Configuration) Consider an operator O with support S, an n-qubit Hamiltonian operator H, and a ϒ-stage product formula as in Eq. (1) with an arbitrary decomposition and permutation. The expansion of support estimation is lower-bounded as

where equality holds with the decomposition in Eq. (2) and permutation in Eq. (3).

Coincidentally, this optimal configuration satisfies the back-and-forth permutation constraint of the celebrated Suzuki-Trotter formula. Adopting {a(υ, γ)} and ϒ from ref. 52, we construct a standard pth-order Suzuki-Trotter formula from this configuration with p being a positive even integer. This formula includes some unitaries disjoint from the light cone of O(t), which are irrelevant to the simulation since they commute with the evolved observable. Removing these irrelevant unitaries preserves the simulation but simplifies it. Figure 2b depicts the light cone and the corresponding reduced product formula, implying a smaller gate count. We summarize this reduced circuit in Alg. 1. In addition to the gate reduction, erroneous terms outside the light cone are irrelevant to the simulation. Consequently, the advanced error bound is linear with the “width” of the light cone and independent of the system size n, as stated in Thm. 1.

Theorem 1

(Local-Observable Error) Consider a local observable O with support S. Suppose the n-qubit H is constantly local and has bounded interaction per qubit. With light-cone width \({w}_{r}:={\sum}_{k = 0}^{r\Upsilon +1}\|{H}_{k}^{S}\|_{1}\), the simulation error of O, when using the r-step pth-order U from Alg. 1, is bounded by

We sketch the proof in Methods and defer the detailed proof to Supplementary Note 2. Interaction per qubit denotes the strength of all interactions overlapping with a fixed qubit. The 1-norm ∥ ⋅ ∥1 sums the absolute values of all Pauli coefficients of an operator. These constraints are formally defined in Supplementary Note 1. The width wr must be smaller than the norm of the entire Hamiltonian ∥H∥1 to ensure the advantage of this error bound over the worst-case analysis \({{\mathcal{O}}}(\|O\| \| H\|_{1}{t}^{p+1}{r}^{-p})\) in ref. 33. Therefore, a short simulation time is necessary. To clarify the scope of “short time”, consider one-dimensional lattice models where t = o(n) suffices. More broadly, we expect the advantages to happen given the time to be short but still polynomial with system sizes. Even though several classical tools emerged for simulating quantum dynamics for typical tasks53,54,55, Hamiltonian simulation problems generally remain classically intractable for polynomial depths56. Consequently, our short-term advantages apply to a meaningful scope.

Algorithm 1

Reduced product formula

For clarity, we utilized matrix exponentials of sub-Hamiltonians \(\{{H}_{k}^{S}\}\) in Alg. 1. However, in practice, we can replace these gates with exponentials of Pauli components of \(\{{H}_{k}^{S}\}\) to simplify realization while keeping the error scaling the same as Thm. 1 since these Pauli decompositions have already been used in our proof.

Global observables

In practical applications of Hamiltonian simulation, measuring global observables is essential for uncovering the overall properties of quantum systems50,57,58,59. However, the light-cone analysis cannot be simply applied to the global observable, as its light cone has already saturated the system. Even though we can consider each local summand of the observable separately, the previous light-cone suppress technique is not effective, which is specifically tailored for a fixed observable. Therefore, a more advanced framework is required to simultaneously control the light-cone expansion from every local term.

To this end, we derive this configuration from the interaction hypergraph of the Hamiltonian H, which reveals the underlying structure of the interactions.

Definition 1

Regarding the Pauli decomposition \(H={\sum }_{\alpha \in {{\mathsf{P}}}^{n}}{s}_{\alpha }{P}_{\alpha }\), the sets \({\{{S}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{L}\) are defined such that every nonzero Pauli term belongs to some Si, with no Si belonging to any other Sj. Additionally, at least one Pauli term has support equal to every Si. The interaction hypergraph G consists of the set of n qubits and \({\{{S}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{L}\) as its vertex and hyperedge sets, respectively.

We regroup H into \({\sum }_{i = 1}^{L}{H}_{{S}_{i}}\) so that every \({H}_{{S}_{i}}\) comprises Pauli terms supported within Si. This regrouping forms a decomposition of H. The permutation arises from the edge-coloring of G with an assignment \(\varphi :{\{{S}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{L}\to [\chi ]\) and a total of χ colors, ensuring disjoint hyperedges of the same color. Sub-Hamiltonians with supports (hyperedges) of the same color commute with each other. Consequently, we can permute sub-Hamiltonians of the same color consecutively and adopt a back-and-forth manner among different stages. This decomposition and permutation complete our chromatic configuration. Since the permutation satisfies the symmetric constraint from52, we next employ {a(υ, γ)} and ϒ to construct a standard pth-order Suzuki-Trotter formula with our chromatic configuration, as summarized in Alg. 2. A concrete example of regrouping and coloring of a nearest-neighbor model is illustrated in Fig. 2c.

Algorithm 2

Chromatic product formula

This chromatic configuration offers advantages by simultaneously suppressing the expansion of each individual summand observable. Therefore, we achieve a mildly expanding light cone for each summand, as detailed in the following lemma. We sketched its proof in Methods and deferred the formal one in Supplementary Note 3.

Lemma 2

(Chromatic Optimality) For an arbitrary set of observables {Om} and a Hamiltonian H, an r-step product formula U from Alg. 2 simultaneously enlarges the support of every UOmU† to at most \(\mathop{\bigcup }_{k = 0}^{(\chi -1)r\Upsilon +1}{E}_{k}^{S({O}_{m})}\). Given that χ is a constant, the support expansion of all observables is optimally slow.

Unlike the single-observable case, the light cones cannot facilitate circuit reductions, as each exponential gets involved in different light cones. Despite needing to implement all exponentials as in Alg. 2, we can reduce the error bound by only considering each summand’s light cone separately. Similarly, the error bound in Thm. 2 is linear with the sum of light-cone widths, independent of the system size. This also suggests an advantage compared to the worst-case error analysis in ref. 33, especially when the simulation time is short (but still polynomial in most cases).

Theorem 2

(Global-Observable Error) Consider the observable \(O=\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) where every Om is a local observable with support S(Om). Suppose the n-qubit H is constantly local and has bounded interaction per qubit. With light-cone widths \({w}_{r,m}:=\mathop{\sum }_{k = 0}^{(\chi -1)r\Upsilon +3}\|{H}_{k}^{S({O}_{m})}\|_{1}\), the simulation error using the r-step pth-order U from Alg. 2 is bounded by

This global analysis and error indicate a linear gate count for the simulations. It is noteworthy that this gate count is much better than trivially implementing Alg. 1 for each local summand, as detailed in the “Applications” section. The idea comes from the fact that the chromatic configuration allows for the reuse of the circuit for all local observables simultaneously. These advantages imply that our method is not a trivial application of Alg. 1.

Similarly, we can decompose the regrouped sub-Hamiltonians used in Alg. 2 into Pauli operators, as we have included the Pauli-level analysis in the proof in Supplementary Note 3.

Observable advantages for arbitrary-time simulations

In our preceding analyses, we primarily focused on short-time simulations with specific knowledge of observables. The question arises naturally to explore the observable-driven advantages in arbitrary-time simulations. To address this, we turn our attention to the average error of random-input simulations, isolating the effects of states. In this section, we analyze the observable-driven reductions in average errors, revealing that the advantage generally exists for observables composed of a sum of Pauli operators. It is noteworthy that this structure does not require a further locality assumption and is mostly relevant in quantum simulation tasks with qubit-encoded molecular systems11,50,51.

To quantify the distance between arbitrary pairs of unitaries U and U0 for a given observable O and an input ensemble μ = {pi, ψi}, we employ the average distance between measurements as a metric:

This metric is experimentally motivated since quantum circuits always end with measurements. By averaging over the ensemble, this distance exhibits the average performance of the simulation in this ensemble.

In the simulation context, algorithms often consist of a sequence of r short steps of unitaries. Therefore, our focus turns to the distance between the r steps of the ideal evolution \({{{\mathscr{U}}}}_{0}={{{\rm{e}}}}^{{{\mbox{i}}}Ht/r}\) and its approximation \({{\mathscr{U}}}={{\mathscr{S}}}(t/r)\). To investigate the average simulation error across the entire state space, we examine the input ensemble of Haar-random states, which can be intuitively understood as uniform randomness in the state space60. While Haar-random sampling is technically demanding, we can use t-design ensembles as a feasible alternative, which are indistinguishable from the Haar measure given t copies of states. In the following, we show that sampling states from a 1-design ensemble μ1, the lowest level of randomness, suffices to exhibit error reductions with observable knowledge.

Theorem 3

(Average Distance and Variance) For a 1-design ensemble μ1 of quantum states and an observable O, we can bound the average distance of simulation:

where \({{\mathscr{A}}}:={{{\mathscr{U}}}}_{0}-{{\mathscr{U}}}\) represents the additive error for each small step, d = 2n is the dimension of the n-qubit Hilbert space, and \(\parallel A{\parallel }_{p}={[{{\rm{Tr}}}(| A{| }^{p})]}^{1/p}\) denotes the Schatten p-norm. The variance of errors can also be bounded by

The proof is outlined in Methods, with a formal version provided in Supplementary Note 4. Based on the variance bound, we can show the concentration of our error analysis through Chebyshev’s inequality. We obtain the following corollary with the nested-commutator analysis by further narrowing the simulation approximation to the standard Suzuki formula methods.

Corollary 1

(Product-Formula Average Error) Adopting \({{{\mathscr{U}}}}^{r}={{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{p}{(t/r)}^{r}\) a standard r-step pth-order Suzuki product formula with the decomposition \(H=\mathop{\sum }_{\gamma = 1}^{\Gamma }{H}_{\gamma }\), the \(D{({{{\mathscr{U}}}}_{0}^{r},{{{\mathscr{U}}}}^{r})}_{O,{\mu }_{1}}\) from Thm. 3 is bounded by \({{\mathcal{O}}}({T}_{2} \Vert O\Vert_{2}{t}^{p+1}{d}^{-1/2}{r}^{-p})\) with

In comparison, the random-input analysis without observable knowledge only ensures a simulation error based on the operator norm of observables43:

Given that \(\|O\|_{2}/\sqrt{d}\le \|O\|\), the error reductions generally exist for any observables. The key insight behind our improvement stems from the dual application of randomness. While ref. 43 only addressed worst-case scenarios in unitary approximation, our approach simultaneously eliminates worst-case bounds in both unitary approximation and observable measurement. For a typical Pauli-summation observable \(O={\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) with evenly distributed coefficients ∥Om∥ = Θ(1), we obtain a quadratic error reduction since \(\parallel O{\parallel }_{2}/\sqrt{d}={{\mathcal{O}}}(\sqrt{M})\), while the operator norm is \(\|O\| ={{\mathcal{O}}}(M)\).

Applications

In this section, we investigate simulations in several common models with observable knowledge. We exhibit the observable-driven advantages in both short-time and arbitrary-time simulations compared to analyses without observable knowledge. We provide a summary of the improved error scalings in Table 1. The detailed derivations of these results are presented in the Supplementary Note 5.

Nearest-neighbor interactions

For an n-qubit D-dimensional lattice Λ with nearest-neighbor interactions, the Hamiltonian is given by H = ∑(i, j)∈ΛHi,j, normalized to ∥Hi,j∥1 ≤ 1.

In short-time simulations, we consider a local observable O with constant-size support S and ∥O∥ = 1. The corresponding edge set \({E}_{k}^{S}\) comprises \({{\mathcal{O}}}({k}^{D-1})\) qubits, leading to the norms of sub-Hamiltonians, \(\|{H}_{k}^{S}\|_{1}={{\mathcal{O}}}({k}^{D-1})\). The simulation error of a r-step pth-order reduced formula from Alg. 1 is bounded by

To exceed the worst-case bound of \({{\mathcal{O}}}(n{t}^{p+1}{r}^{-p})\) from ref. 32, we require rD = o(n). Therefore, the gate count of the simulation is \({{\mathcal{O}}}({r}^{D+1})\), independent of system size.

For a global observable \(O=\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) with \(\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}\|{O}_{m}\| =1\), the 1-norm \(\|{H}_{k}^{S({O}_{m})}\|_{1}\) for any m similarly scales as \({{\mathcal{O}}}({k}^{D-1})\). By coloring hyperedges using χ = 2D colors, the simulation error of an r-step pth-order Trotter formula from Alg. 2 is bounded by

We need rD = o(n) to outperform the worst-case bound. The overall gate count is \({{\mathcal{O}}}(rn)\), more efficient than trivially implementing Alg. 1 for each summand solely, as shown in Supplementary Note 5.

In arbitrary-time simulations, we focus on the average error with random inputs. Specifically, we find that the nested-commutator scales as \({T}_{2}={{\mathcal{O}}}(\sqrt{n})\). Given a Pauli-summation observable \(O=\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) such that all norms of Pauli operators are evenly distributed, i.e., \(\|{O}_{m}\| ={{\mathcal{O}}}({M}^{-1})\), the average simulation error by a r-step pth-order Trotter formula is bounded by

In contrast, the analysis without specific observable knowledge only offers a bound of \({{\mathcal{O}}}({n}^{1/2}{t}^{p+1}{r}^{-p})\) in ref. 43. For example, the magnetization \(\mathop{\sum }_{j = 1}^{n}{Z}_{j}/n\) has a normalized Schatten 2-norm \({{\mathcal{O}}}(1/\sqrt{n})\), generating a size-independent error of \({{\mathcal{O}}}({t}^{p+1}{r}^{-p})\). Our analysis thus provides an additional \({{\mathcal{O}}}(\sqrt{n})\) speed-up compared to the analysis without observable knowledge.

Power-law interactions

For an n-qubit D-dimensional lattice Λ, we also consider the power-law decaying interactions HP = ∑i≠jHi,j with \(\|{H}_{i,j}\| ={{\mathcal{O}}}(\,{{\mbox{d}}}\,{(i,j)}^{-\alpha })\), where d( ⋅ , ⋅ ) represents some proper distance for lattices and α > 2D.

We first identify the short-time advantage for a local observable O with ∥O∥ = 1 and a constant-size support S. By fixing a d0 > 0, we divide the lattice into two parts: Λin: = {j ∈ Λ ∣ d(j, S) ≤ (rϒ + 1)d0} and Λout = Λ\Λin. We truncate HP to Hlc by removing interactions that are longer than d0 and involved in Λin. The truncation error is bounded by \({{\mathcal{O}}}({r}^{D}{d}_{0}^{2D-\alpha }t)\) as calculated in6. This truncation prevents the instant saturation of light cones. Therefore, we can combine Thm. 1 to bound the error of an r-step pth-order reduced formula by

Choosing \({d}_{0}={{\mathcal{O}}}({(r/t)}^{p/(\alpha -D)})\), we get the exhibited error, aligning with the local analysis in ref. 33.

As for the global observable \(O=\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) with \(\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}\|{O}_{m}\|_{1}=1\), we adopt a more general truncation as \({H}_{{{\rm{trc}}}}={\sum }_{i,j\in \Lambda ,{\mbox{d}}(i,j)\le {d}_{0}}{H}_{i,j}\). Taking the observable O into account, we get a nearly size-independent truncation error, \(\tilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\left({t}^{D+1}{d}_{0}^{2D-\alpha }\right)\), with \(\tilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}\) omitting the logarithmic terms. By further considering the interaction hypergraph of Htrc with its edge-coloring, the simulation error of an r-step pth-order formula is bounded by

with its minimizer \({d}_{0}=\tilde{{{\mathcal{O}}}}({(r/t)}^{(p-D)/(\alpha -D)})\). This generates a nearly size-independent simulation error.

We also investigate the advantage of arbitrary-time simulations with random inputs for this model. The nested-commutator term scales as \({T}_{2}={{\mathcal{O}}}(n)\). For a Pauli-summation observable \(O=\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) such that all norms of Pauli operators are evenly distributed, i.e., \(\| {O}_{m}\| ={{\mathcal{O}}}({M}^{-1})\), the average error bound using an r-step pth-order Trotter product formula is

As a comparison, average-error analysis without observable knowledge only retains the worst-case result, \({{\mathcal{O}}}(n{t}^{p+1}{r}^{-p})\), for this model43.

Numerical results

In this section, we present numerical results that demonstrate the benefits of incorporating observable knowledge in quantum simulation. Our results illustrate observable-driven advantages in both short-time and arbitrary-time simulations, utilizing our support and random-input analyses, respectively. Detailed numerical settings are deferred to Methods and Supplementary Note 6.

First, we examine the short-time simulation advantages as shown in Fig. 3. In subplot (a), we focus on the gate counts for simulating an n-qubit one-dimensional mixed-field Ising (MFI) Hamiltonian,

Specifically, we consider the number of exponentials as the gate count required to implement second-order product formulas for simulating the local observable O = Z1 and the global observable \(O=\frac{1}{n-1}{\sum }_{j = 1}^{n-1}{Z}_{j}{Z}_{j+1}\) with a fixed precision ∥eiHtOe−iHt − UOU†∥ ≤ ϵ. The theoretical lines are estimated based on error analyses from our Thms. 1 and 2, and the worst-case bound in ref. 33. These results highlight the observable-driven speed-ups of short-time simulation. Empirical gate counts from both Algs. 1 and 2 closely align with our theoretical results, suggesting the tightness of our theoretical bounds.

a Number of exponentials needed to achieve simulation precision ϵ = 10−3 at t = 0.1 under an MFI Hamiltonian with J = 1, h = 0.5, g = 1.2 as in Eq. (11). The gate counts for local (green) and global (yellow) obs (short for observables), Z1 and \(\frac{1}{n-1}\mathop{\sum }_{j = 1}^{n-1}{Z}_{j}{Z}_{j+1}\) are obtained from different theoretical and empirical error estimations. b Simulation of dynamical quantum phase transition with k = 3 local observable as in Eq. (12). We use a 12-qubit TFI Hamiltonian with J = 0.2 and h = 1 as in Eq. (13). By fixing the precision ϵ = 0.05 and a gate budget of 500, the guaranteed simulation times are t = 1.80 from Thm. 1 and \({t}^{{\prime} }=1.15\) from worst-case analysis in ref. 33, with step lengths δt = 0.12 and \(\delta {t}^{{\prime} }=0.08\). In the inset, we validate the local approximation of the rate function λn(t) by λk(t).

In Fig. 3b, we demonstrate short-time advantages in the practical task of exploring the local dynamical quantum phase transition (DQPT), which approximates the original DQPT using local observables as introduced in ref. 47. Specifically, we rehearse the full procedures to estimate the local rate function \({\lambda }_{k}(t):=-\log ({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{k}(t))/k\) using different product formulas with

where k = 3, \(| \psi (0)\left.\right\rangle ={| 0\left.\right\rangle }^{\otimes n}\), and \({P}_{j}:={| 0\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.0| }_{j}\) is the projector on the j-th qubit. We adopt a one-dimensional transverse-field Ising (TFI) Hamiltonian

with n = 12. Fixing the precision ϵ and a gate budget, our bound from Thm. 1 and the worst-case analysis from ref. 33 reports the number of steps used and guaranteed simulation times, exceeding which the simulation error cannot be bounded by ϵ. Using these parameters, we implement the second-order Alg. 1 and standard product formula to estimate the rate functions and get empirical results. Our bound offers a longer guaranteed simulation time, increasing by 50% compared to the worst-case bound. This gap widens with increasing system size. Clearly, the worst-case analysis fails to capture the critical point with the given constraints.

For the random-input result in Fig. 4, we first estimate the (average) simulation distances for different analyses of a one-dimensional power-law decaying Hamiltonian,

We focus on the observable \(O={\sum }_{j = 1}^{n}{Z}_{j}\). The theoretical lines are based on the worst-case analysis33, the previous random-input analysis without observable knowledge from ref. 43, and our Cor. 1. As shown in Fig. 4a, our analysis is significantly tighter than the previous random-input analysis, improved by \({{\mathcal{O}}}(\sqrt{n})\).

a Errors for simulating ∑jZj under a power-law Hamiltonian with α = 4, J = 1, and h = 0.5 as in Eq. (14). We simulate dynamics with increasing sizes, setting t = n with a fixed step number r = 10,000. Error bars indicate standard deviations of simulation errors across 500 independent Haar-random states per empirical point. We fit the errors to get powers of their scaling as shown in dashed lines. b Errors for simulating the dynamics of a 6-qubit Hydrogen chain H3 with bond length 2 Å as in Eq. (15), with the observable being another H3 Hamiltonian at bond length 1 Å. We fix the step length t/r = 0.1. Error bars represent standard deviations estimated by 500 independent Haar-random states. c The number of exponentials required to ensure average errors smaller than ϵ = 10−3 in different theoretical and empirical analyses at t = 15. We choose the same dynamics and observables as (b). Two empirical bars represent the mean value obtained from 50 rounds of sampling for 50 random states. The error bars, denoting standard deviations, are negligibly small. d, e Insets of (b) depicting empirical error distributions at t = 15 from 500 random states for cases with and without observable knowledge, respectively.

We exhibit the random-input advantage in a more practical setting in subplots (b)-(e) by simulating the Hamiltonian of a three-atom Hydrogen chain H3

targeting the observable of another H3 Hamiltonian with a different bond length. Although the molecular Hamiltonian is complicated after the Jordan-Wigner transformation, we can efficiently estimate the Schatten 2-norm to bound the error tightly using Cor. 1 even for a large n. As shown in (b), incorporating observable knowledge significantly reduces both theoretical and empirical errors. Subplot (c) shows the number of exponentials required to implement second-order product formulas within a precision of ϵ = 10−3 in different cases. Violins in subplots (d) and (e) illustrate the empirical distributions of simulation errors from Haar-random-input states.

Discussion

Our study comprehensively analyzes the advantages of incorporating observable knowledge in both short-time and arbitrary-time simulation scenarios. For short-time simulations, we design specific product formulas for different observables. Our methods and analyses extend the advantage beyond local observables in ref. 33 to certain global-observable simulations. For specific Hamiltonians, our analyses suggest size-independent simulation errors for both local and global observables. For arbitrary simulation times, we evaluate the state-independent observable-driven speed-ups by averaging over random-input states. We show that observables consisting of a sum of Pauli operators generally reduce average errors compared to previous analyses without observable knowledge43,61, resulting in the typical quadratic reductions with the number of summands. In both scenarios, improved error analyses imply better gate counts than previously expected, which we anticipate will facilitate the practical advantages of quantum simulations. We validate these theoretical results and demonstrate speed-ups in practical applications through our numerical studies.

Detecting further speed-ups from observable knowledge for simulating general times presents an interesting future direction. While we focus on average simulation accuracy in this work, a more thorough analysis of observable-driven advantages in other input settings could generate valuable insights. Additionally, our previous numerical results indicate that the empirical average simulation accuracy can vastly exceed theoretical predictions, suggesting room for future improvements, as shown in Fig. 4.

Experimental implementations of the proposed simulation algorithms also hold promise for better performance in practice. As shown in our study, theoretical bounds, including short-time and arbitrary-time simulation errors, can be easily calculated in advance. These results could lead to more accurate and resource-efficient gate count estimation in some complicated tasks related to quantum chemistry and high-energy physics. Such progress could narrow the gap between realizing quantum advantages and near-term experimental capabilities.

Methods

Sketch proofs for short-time local observables

In the case of a single local observable within a short-time evolution, we adopt the interactive decomposition and even-odd permutation to implement the product formula. Under this product formula, the support of the observable slowly expands along with time steps, which is optimal from Lemma 1. Therefore, those unitary terms outside the support never get involved in the evolution of the observable. Simply removing them reduces the complexity of this product formula, as stated in Alg. 1. According to Thm 1, this reduced formula offers both a better error bound and a better gate count.

We first start the sketch proof of Lemma 1 from the first stage of the product formula. By definition, each qubit in \({E}_{1}^{S}\) must be within the support of some certain Pauli term Pα in H such that \(S({P}_{\alpha })\cap S\ne {{\emptyset}}\). Thus, the lower bound holds for ϒ = 1,

The proof extends inductively for larger ϒ according to the definition of edge sets. The optimality of the product formula with interactive decomposition and even-odd permutation is also proven inductively. Starting with ϒ = 1, we show that \(S({H}_{j}^{S})\cap S({H}_{k}^{S})\ne {{\emptyset}}\) only for ∣j − k∣ = 1. Therefore, we have \({ \biguplus }_{\gamma = 1}^{\Gamma }{{{\rm{e}}}}^{{{\mbox{i}}}t{a}_{(1,\gamma )}{H}_{{\pi }_{1}^{{{\rm{eo}}}}(\gamma )}^{S}}\uplus S={E}_{1}^{S}\cup S\). This equality can be easily proved inductively for larger ϒ, which completes the proof.

Alg. 1 is implemented by removing all exponentials disjoint with the support as suggested by Lemma 1. Unlike the standard Suzuki-Trotter formula, we cannot directly employ the nested-commutator bound in ref. 33 for this algorithm. To prove Thm. 1, we can fill exponentials in Alg. 1 to align each step with a standard formula of H. We denote this filled method the virtual product formula

For example, by the end of step j, sub-Hamiltonians \(\{{H}_{1}^{S},\cdots \,,{H}_{j\Upsilon }^{S}\}\) would intersect with the light cone. Hence, we fill the step j’s formula to \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{j}(\tau )\) with even-odd permutation and decomposition

Therefore, we can use the triangle inequality to bound the error between eiHt and U by the following two parts: the error between U and \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{V}(t)\), and the error from \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{V}(t)\) to the ideal eiHt. It is easy to check that the support of evolved O under the virtual formula is still optimally expanding. In this sense, the exponential of Hothers,j, is outside the support in each step j and does not affect the evolved O, which means the first error is zero. The second error can be bounded by the nested-commutator bound, which is linear with \(\mathop{\sum }_{k = 0}^{r\Upsilon +1}\| {H}_{k}^{S}\|_{1}\). Combining these two parts, we get the error bound linear with the “width” of the light cone.

Sketch proofs for short-time global observables

In this section, we focus on the proofs in simulating global observables consisting of a summation of local observables. For simplicity, we assume all summand observables are commuted. Otherwise, we can always divide the summation into different stabilizer groups and estimate them independently. This analysis hinges on a clever design of the configuration such that all observables are expanding slowly. To this end, we introduce the interaction hypergraph in Def. 1 and the edge coloring thereof, which suggest the regrouping decomposition and coloring permutation, respectively. The corresponding product formula is summarized in Alg. 2.

Lemma 2 asserts that a ϒ-stage Alg. 2 with χ colors expands an arbitrary support S(O) to its first (χ − 1)ϒ + 1 edge sets. Note that the sub-Hamiltonians within a single color are mutually disjoint, allowing us to consider the collection of exponentials of the same color as a unified entity in the implementation. Starting from the first color, exponentials contribute to the expansion of S(O) only if sub-Hamiltonians overlap with S(O), so

The same illustration applies to subsequent colors and stages, so each color and stage of the product formula enlarges the support by at most one layer. Alg. 2 recruits the back-and-forth permutation, ensuring continuity of colors between stages. Therefore, there are altogether (χ − 1)rϒ + 1 effective colors, which completes the proof.

As for the error bound for simulating \(O=\mathop{\sum }_{m = 1}^{M}{O}_{m}\) in Thm. 2, we analyze the error for every single summand observable and combine them by the triangle inequality. For each summand Om, we introduce the corresponding virtual product formula according to its own edge sets,

For example, since by the end of step j, the support of Om at most reaches \(\mathop{\bigcup }_{i = 0}^{(\chi -1)j\Upsilon +1}{E}_{i}^{S({O}_{m})}\), the virtual formula uses the coloring decomposition for interactions intersecting the light cone and absorbs all other terms in the tail. Considering the commutation relationships regarding the evolved Om, all unitaries outside the light cone are ineffective in both \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{{{\rm{V}}},m}(t)\) and Alg. 2. The simulations for Om from \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{{{\rm{V}}},m}(t)\) and U are equivalent. We then analyze simulation error between \({{{\mathscr{S}}}}_{{{\rm{V}}},m}(t)\) and eiHt. The nested commutator of the jth virtual product for Om scales as \({{\mathcal{O}}}(\mathop{\sum }_{i = 0}^{j\chi \Upsilon +2}{h}_{m,i})\). Combining simulation errors for all j and Om according to the triangle inequality, we complete the analysis of overall simulation errors.

Sketch proofs for random-input simulation

We also sketch the proof for Thm. 3. To this end, we first divide the distance \(D{({{{\mathscr{U}}}}_{0}^{r},{{{\mathscr{U}}}}^{r})}_{O,{\mu }_{1}}\) based on the triangle inequality so that each term in the summation represents a single-step error in the following form

where \({U}_{1}={{{\mathscr{U}}}}^{i-1}\) and \({U}_{2}={{{\mathscr{U}}}}_{0}^{r-i}\) for step i ∈ [1, r]. Recalling that the state \(| \psi \left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.\psi |\) is sampled from a 1-design ensemble, the integral over the 1-design ensemble leads to the Schatten 1-norm distance. Due to the unitary invariance of the Schatten norms, we can discard these two unitaries, U1 and U2. Using the Hölder inequality, we can decompose this distance into the product of two Schatten 2-norms,

By further summing over all errors from various steps, we can get the claimed error scaling.

The variance proof follows a similar approach. We first employ the triangle inequality to decompose the overall error. Then, according to the Hölder and Cauchy-Schwarz inequalities, we can further derive the variance to identify the state alone. Using the 1-design properties of the state ensemble, we can get the desired result.

As for Cor. 1, we propose a more specific bound for the standard Trotter-Suzuki simulation. We recruit a similar result from ref. 43 to bound \(\|{{\mathscr{A}}}\|_{2}\) by the nested commutator over sub-Hamiltonian terms and further generate the second-order error bound. Refer to Supplementary Note 4 for full details.

Numerical settings

In Fig. 3, we evaluate the gate complexities in short-time simulation for different tasks. In subplot (a), we estimate the gate count to simulate observables under an MFI Hamiltonian within the 10−3 precision. We estimate the worst-case theoretical error of the second-order Suzuki-Trotter formula using the explicit version of the nested-commutator bound, Prop. 10, in ref. 33. This proposition is also used to derive explicit versions of Thms. 1 and 2 as substitutes for the asymptotic version of the nested-commutator bounds. To efficiently compute the error estimation for large n, we adapt operator norms in all bounds to the 1-norms (summation of Pauli coefficients) according to the triangle inequality. Empirical errors are faithfully calculated from ∥eiHtOe−iHt − UOU†∥ with U adopted from Alg. 1 or 2. With these error analyses, we perform a binary search for the desired number of steps. In subplot (b), we explore the DQPT using the local observable. With the fixed precision and gate budget, we estimated guaranteed simulation times from the explicit versions of Thm. 1 and the worst-case bound. Refer to Supplementary Note 6 for detailed bounds.

In Fig. 4, we focus on the random-input results of various models. In (a), we exhibit average-case errors with or without observables and the worst-case errors along system sizes. The average errors are calculated from Cor. 1 and Thm. 3 from43, respectively. The empirical average errors are estimated from 500 Haar-random states, with blue circles denoting the random errors without observable knowledge ∥e−iHtρeiHt − U†ρU∥1∥O∥, and orange circles denoting our observable-induced case \({{\rm{Tr}}}[({{{\rm{e}}}}^{-{{\mbox{i}}}Ht}\rho {{{\rm{e}}}}^{{{\mbox{i}}}Ht}-{U}^{{\dagger} }\rho U)O]\). For subplot (b), we simulate the Hydrogen chain Hamiltonian H3 with a bond length of 2 Å and measure on another H3 at 1 Å. Hydrogen chain Hamiltonians from Eq. (15) with specific bond length and the sto-3g basis are generated by ref. 62. It is noteworthy that since the observable consists of anti-commutative Pauli operators, they cannot be simultaneously measured by a projective measurement. To simplify the product formula and realize measurements, we decompose both the Hamiltonian and observable (two H3 Hamiltonians) into multiple mutually commutative subsets (stabilizer sets) by a simple greedy algorithm. The figure depicts overall errors for all subsets with a fixed t/r. In (c), we similarly use the binary search to find the same r for all subsets to calculate the total number of exponentials. Error analyses are the same as (b).

Data availability

The data is generated from the numerical simulation to demonstrate the advanced Hamiltonian simulation analyses. The data can be accessed through GitHub at https://github.com/Jue-Xu/Trotter-Error-with-Observable.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available on GitHub at https://github.com/Jue-Xu/Trotter-Error-with-Observable.

References

Feynman, R. P. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theoret. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Noh, C. & Angelakis, D. G. Quantum simulations and many-body physics with light. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 016401 (2016).

Schreiber, M. et al. Observation of many-body localization of interacting fermions in a quasirandom optical lattice. Science 349, 842 (2015).

Randall, J. et al. Many-body–localized discrete time crystal with a programmable spin-based quantum simulator. Science 374, 1474 (2021).

Su, G.-X. et al. Observation of many-body scarring in a Bose-Hubbard quantum simulator. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023010 (2023).

Tran, M. C. et al. Locality and digital quantum simulation of power-law interactions. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031006 (2019).

Heyl, M., Hauke, P. & Zoller, P. Quantum localization bounds Trotter errors in digital quantum simulation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau8342 (2019).

Jordan, S. P., Lee, K. S. M. & Preskill, J. Quantum algorithms for quantum field theories. Science 336, 1130 (2012).

Jordan, S. P., Krovi, H., Lee, K. S. M. & Preskill, J. BQP-completeness of scattering in scalar quantum field theory. Quantum 2, 44 (2018).

Babbush, R. et al. Low-depth quantum simulation of materials. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011044 (2018).

McArdle, S., Endo, S., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Benjamin, S. C. & Yuan, X. Quantum computational chemistry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 015003 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Evaluating the evidence for exponential quantum advantage in ground-state quantum chemistry. Nat. Commun. 14, 1952 (2023).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073 (1996).

Aharonov, D. & Ta-Shma, A. Adiabatic quantum state generation and statistical zero knowledge. in Proceedings of the Thirty-fifth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. 20–29 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2003).

Childs, A. M., Quantum Information Processing in Continuous Time. Ph.D. thesis (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004)

Berry, D. W., Ahokas, G., Cleve, R. & Sanders, B. C. Efficient quantum algorithms for simulating sparse Hamiltonians. Commun. Math. Phys. 270, 359 (2007).

Somma, R. D. A Trotter-Suzuki approximation for lie groups with applications to Hamiltonian simulation. J. Math. Phys. 57, 062202 (2016)

Mc Keever, C. & Lubasch, M. Classically optimized Hamiltonian simulation. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023146 (2023).

Childs, A. M. & Wiebe, N. Hamiltonian simulation using linear combinations of unitary operations. Quant. Inf. Comput. 12, https://doi.org/10.26421/QIC12.11-12 (2012).

Berry, D. W., Childs, A. M., Cleve, R., Kothari, R. & Somma, R. D. Exponential improvement in precision for simulating sparse Hamiltonians. in Proceedings of the Forty-sixth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. 283–292 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2014).

Berry, D. W., Childs, A. M., Cleve, R., Kothari, R. & Somma, R. D. Simulating Hamiltonian dynamics with a truncated Taylor series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 090502 (2015).

Berry, D. W., Childs, A. M. & Kothari, R. Hamiltonian simulation with nearly optimal dependence on all parameters. in 2015 IEEE 56th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. 792–809 (IEEE, 2015).

Haah, J., Hastings, M. B., Kothari, R. & Low, G. H. Quantum algorithm for simulating real time evolution of lattice Hamiltonians. SIAM J. Comput. 52, FOCS18 (2021).

Low, G. H. & Chuang, I. L. Optimal Hamiltonian simulation by quantum signal processing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 010501 (2017).

Low, G. H. & Chuang, I. L. Hamiltonian simulation by qubitization. Quantum 3, 163 (2019).

Childs, A. M., Maslov, D., Nam, Y., Ross, N. J. & Su, Y. Toward the first quantum simulation with quantum speedup. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9456 (2018).

Brown, K. R., Clark, R. J. & Chuang, I. L. Limitations of quantum simulation examined by simulating a pairing Hamiltonian using nuclear magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 050504 (2006).

Lanyon, B. P. et al. Universal digital quantum simulation with trapped ions. Science 334, 57 (2011).

Lv, D. et al. Quantum simulation of the quantum Rabi model in a trapped ion. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021027 (2018).

Jafferis, D. et al. Traversable wormhole dynamics on a quantum processor. Nature 612, 51 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500 (2023).

Childs, A. M. & Su, Y. Nearly optimal lattice simulation by product formulas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 050503 (2019).

Childs, A. M., Su, Y., Tran, M. C., Wiebe, N. & Zhu, S. Theory of Trotter error with commutator scaling. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011020 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Measuring out-of-time-order correlators on a nuclear magnetic resonance quantum simulator. Phys. Rev. X 7, 031011 (2017).

Gärttner, M. et al. Measuring out-of-time-order correlations and multiple quantum spectra in a trapped-ion quantum magnet. Nat. Phys. 13, 781 (2017).

Landsman, K. A. et al. Verified quantum information scrambling. Nature 567, 61 (2019).

Green, A. M. et al. Experimental measurement of out-of-time-ordered correlators at finite temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 140601 (2022).

Simon, J. et al. Quantum simulation of antiferromagnetic spin chains in an optical lattice. Nature 472, 307 (2011).

Martinez, E. A. et al. Real-time dynamics of lattice gauge theories with a few-qubit quantum computer. Nature 534, 516 (2016).

Monroe, C. et al. Programmable quantum simulations of spin systems with trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025001 (2021).

Borns-Weil, Y. & Fang, D. Uniform observable error bounds of Trotter formulae for the semiclassical Schrodinger equation. Multiscale Model. Simul. 23, 255–277 (2025).

Huang, H.-Y., Tong, Y., Fang, D. & Su, Y. Learning many-body Hamiltonians with Heisenberg-limited scaling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 200403 (2023).

Zhao, Q., Zhou, Y., Shaw, A. F., Li, T. & Childs, A. M. Hamiltonian simulation with random inputs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 270502 (2022).

Heyl, M., Polkovnikov, A. & Kehrein, S. Dynamical quantum phase transitions in the transverse field Ising model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 135704 (2013).

Heyl, M. Dynamical quantum phase transitions: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 054001 (2018).

De Nicola, S., Michailidis, A. A. & Serbyn, M. Entanglement view of dynamical quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 040602 (2021).

Halimeh, J. C., Trapin, D., Van Damme, M. & Heyl, M. Local measures of dynamical quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 104, 075130 (2021).

Friis, N. et al. Observation of entangled states of a fully controlled 20-qubit system. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021012 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. A scheme to create and verify scalable entanglement in optical lattice. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 99 (2022).

Huggins, W. J. et al. Unbiasing Fermionic quantum Monte Carlo with a quantum computer. Nature 603, 416 (2022).

Guo, S. et al. Experimental quantum computational chemistry with optimized unitary coupled cluster ansatz. Nat. Phys. 20, 1240–1246 (2024).

Suzuki, M. General theory of fractal path integrals with applications to many-body theories and statistical physics. J. Math. Phys. 32, 400 (1991).

Wild, D. S. & Alhambra, Á. M. Classical simulation of short-time quantum dynamics. PRX Quant. 4, 020340 (2023).

Bravyi, S., Gosset, D. & Liu, Y. Classical simulation of peaked shallow quantum circuits. in Proceedings of the 56th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. 561–572 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2024)

Bravyi, S., Gosset, D. & Movassagh, R. Classical algorithms for quantum mean values. Nat. Phys. 17, 337 (2021).

Bremner, M. J., Montanaro, A. & Shepherd, D. J. Average-case complexity versus approximate simulation of commuting quantum computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 080501 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. Observation of a many-body dynamical phase transition with a 53-qubit quantum simulator. Nature 551, 601 (2017).

Jurcevic, P. et al. Direct observation of dynamical quantum phase transitions in an interacting many-body system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 080501 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Realization of fractional quantum Hall state with interacting photons. Science 384, 579 (2024).

Mele, A. A. Introduction to Haar measure tools in quantum information: a beginner’s tutorial. Quantum 8, 1340 (2024).

Chen, C.-F. & Brandão, F. G. Average-case speedup for product formulas. Commun. Math. Phys. 405, 32 (2024).

McClean, J. R. et al. OpenFermion: the electronic structure package for quantum computers. Quant. Sci. Technol. 5, 034014 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiao Yuan, You Zhou, and Pei Zeng for helpful discussions. Q.Z. acknowledges funding from Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology via Project 2024ZD0301900, National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) via Project No. 12347104 and No. 12305030, Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation via Project 2023A1515012185, Hong Kong Research Grant Council (RGC) via No. 27300823, N_HKU718/23, and R6010-23, Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative No. GDZX2303007, HKU Seed Fund for Basic Research for New Staff via Project 2201100596.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y., J.X., and Q.Z. collaboratively initialized the research ideas, derived the mathematical proofs, and wrote the manuscript. J.X. performed the numerical simulations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another Nature Portfolio journal. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Physics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, W., Xu, J. & Zhao, Q. Observable-driven speed-ups in quantum simulations. Commun Phys 8, 340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02260-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02260-5