Abstract

Periodic potentials have been widely used to control the phase behavior of colloidal suspensions in equilibrium, particularly to induce freezing and melting phase transitions. Recently, much progress has also been made in controlling the phases of active colloids that can self-propel and are far from equilibrium. While some recent studies have explored controlling active colloids using periodic potentials, the majority of research has focused on spatially uniform fields. Here we transfer the concept of lattice-induced freezing and melting to active systems and show that imposing a spatially periodic potential on active colloids not only triggers freezing and melting transitions but additionally leads to the emergence of a so-far unknown active matter phase. This phase, which we term “active adaptolates”, adopts the geometry of the underlying lattice like a frozen phase, forms an interconnected percolated structure, and maintains the ballistic dynamics of the molten phase. These results demonstrate the potential to use external patterned fields to design the internal structure of active systems without disrupting their intrinsic dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phase transitions that are induced by external potentials play an important role in physics. For example, in atomic and condensed matter physics, the superfluid-Mott-insulator transition occurs when changing the depth of a standing light wave (optical lattice), which serves as a periodic potential for (ultracold) atoms1,2,3. This phase transition is controlled by the competition between the optical lattice and quantum fluctuations and occurs even at zero temperature. It separates a superfluid phase, where atoms are delocalized, from an insulating phase of localized atoms. In soft matter physics, where thermal fluctuations are important and quantum fluctuations are negligible, the phenomenon of laser-induced freezing and melting uses a similar optical lattice to control a phase transition in colloidal suspensions4,5,6. Here, a disordered (gas-like) phase occurs for shallow lattices where colloidal particles diffuse freely, whereas, for steep lattices, we find a solid-like phase in which the particles are confined to the minima of the lattice and adopt the structure of the latter7,8.

Unlike these equilibrium transitions, substrate- or lattice-induced phase transitions have not yet been extensively explored in far-from-equilibrium systems. While some recent works have demonstrated the potential of periodic substrates9,10 and external fields11 to control the collective dynamics of active particles, a comprehensive understanding of lattice-induced effects remains limited. In the present work, we transfer the concept of lattice-induced freezing and melting to active matter systems12,13,14,15,16,17, comprising self-propelled particles such as synthetic active colloids18,19,20,21,22, droplet swimmers23,24,25,26,27, granular microflyers28,29,30,31, or bacteria32,33,34. For shallow lattices, perhaps unsurprisingly, we find that the active particles self-organize into clusters featuring a liquid-like local hexagonal packing structure. These clusters grow over time and eventually result in motility-induced phase separation (MIPS)35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. For steep lattices, similar to passive colloids, we observe that the active particles are trapped in the lattice minima, showing localized on-site motion. Strikingly, however, for intermediate lattice heights, we find a so-far unknown dynamic percolated state that is induced by activity. In this phase, the particles aggregate locally, similarly as in the early stage of MIPS, but do not show a hexagonal structure. Instead, the aggregates adopt the structure of the underlying square lattice while continuously being in motion, which is reflected by a non-saturating mean-squared displacement. In addition, shortly after emerging, the aggregates merge into a highly dynamic and interconnected percolated structure, distinct from both the trapped and molten phases in terms of large-scale structure. Following their intrinsic active dynamics, local structural adaptation to the substrate lattice, and their percolated large-scale structure, we introduce the portmanteau “active adaptolates" phase for later convenience. Note that their adaptivity to the substrate and associated local structures clearly distinguishes them from other percolating structures in active matter43,44,45. Notably, the phase of active adaptolates (AA) is separated from the trapped phase by a distinct peak in the susceptibility, and a finite-size scaling analysis suggests that it emerges through a proper phase transition. Overall, the present work shows that the idea of laser-induced freezing and melting of colloidal systems can not only be transferred to active matter but also leads to an intriguing intermediate phase, which unifies the dynamic properties of an active liquid with the structural properties of the trapped phase. This can be used in the future to create active fluids with a structure that can be controlled by an external potential.

Results

Model

We consider a two-dimensional (2D) system of N interacting overdamped active Brownian particles (ABPs). We denote the position and orientation of the ith colloid by \({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }\) and θi, respectively. Each particle has a diameter σ, self-propels with velocity v0, and has a translational diffusion coefficient Dt. We also fix the rotational diffusion coefficient to Dr = 3Dt/σ2 satisfying the fluctuation-dissipation theorem in Newtonian equilibrium solvents. The interaction between the particles is modeled by the Weeks-Chandler-Andersen potential characterized by the potential depth \({\epsilon }^{{\prime} }\) and (soft) particle diameter σ46. Additionally, we impose an external periodic potential landscape with a spatial periodicity \({L}^{{\prime} }\) in both directions and potential height \({V}^{{\prime} }\). Choosing the units of length and time as ru = σ and tu = σ2/Dt (three times the persistence time 1/Dr of the ABPs), respectively, the dimensionless position ri and orientation θi of the ith ABP evolve according to

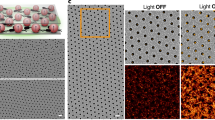

(primed and unprimed symbols refer to dimensional and dimensionless quantities, respectively; see the “Methods” section for the equations of motion with dimensions). Here \({{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}=(\cos {\theta }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}},\sin {\theta }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\) is the orientation vector of the ith ABP and Pe = v0σ/Dt is the Péclet number. The reduced force on the ABPs due to the external lattice is given by \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{{{\rm{lat}}}}}=-{\nabla }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}U({x}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}},{y}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\) with \(U(x,y)=V[{\cos }^{2}(\pi x/L)+{\cos }^{2}(\pi y/L)]\); where \(V={V}^{{\prime} }/({k}_{B}T)\) and \(L={L}^{{\prime} }/\sigma\) denote the dimensionless lattice height and spatial periodicity, respectively. ξi(t) and ηi(t) denote fluctuations modeled by Gaussian white noise with zero mean and unit variance. The reduced interaction force is denoted by \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{{{\rm{int}}}}}=-{\sum }_{j = 1,j\ne i}^{N}{\nabla }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}{U}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}\) with \({U}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}=4\epsilon ({(1/{r}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}})}^{12}-{(1/{r}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}})}^{6})+\epsilon\), if rij < rc and zero otherwise, where \(\epsilon ={\epsilon }^{{\prime} }/({k}_{B}T)\), rc = 21/6 (a dimensionless number) and rij = ∣ri−rj∣. Experimentally, this model could be realized, for e.g., using micron-sized active colloids that are exposed to a 2D optical lattice4,47,48,49 created with a CO2 laser. An alternative realization could be to use granular particles on a 3D-printed periodic substrate mounted on a vibrating plate28,31. Eqs. (1) and (2) are numerically solved using the LAMMPS open source package50,51 (see “Methods” section for details). Our system is characterized by four dimensionless parameters Pe, V, L, ϵ, and the packing fraction of the particles \(\phi =N\pi /4{L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{2}\). To be in the regime where the system shows MIPS, we fix Pe = 300rc and ϕ = 0.5, and to avoid significant particle overlap, we fix \(\epsilon =300{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\). Lastly, to explore the competition between the lattice potential and the inherent tendency of ABPs towards hexagonal packing, we set L = rc and investigate the collective dynamics of ABPs for different values of V.

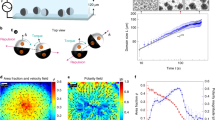

Active adaptolates

In the absence of a periodic potential, the ABPs undergo MIPS and self-organize into hexagonally-packed clusters, defined as collections of particles where each particle has an inter-particle distance ≤rc to some other particle (Fig. 1a). These clusters grow with time, ultimately coarsening towards a phase-separated state of a co-existing dilute gas-like phase and a dense liquid-like phase21,35,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. As long as the effective force due to the external potential is weaker compared to the effective self-propulsion (Vπ/L ≲ 2Pe/3, or \(V \, \lesssim \, 65{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\)), we observe a similar phase separation of the ABPs into a dilute phase and a dense phase possessing a local hexagonal structure (Fig. 1b). In contrast, a steep barrier height (Vπ/L ≳ Pe or \(V \, \gtrsim \, 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\)) completely suppresses particle aggregation and freezes the particle dynamics similarly as in passive colloids4,5. The ABPs are then localized within potential minima, with each particle occupying a single site, thus yielding a trapped phase similar to passive colloids7,8 (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, however, at intermediate barrier heights (\(65{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2} \, \lesssim \, V \, \lesssim \, 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\)), we observe an additional phase that has no counterpart in classical laser-induced freezing and melting scenarios. In particular, we find that the ABPs rapidly aggregate in large porous network-like structures that span the entire system (Fig. 1c, d and Supplementary Movie 1). Locally, unlike MIPS, they do not show hexagonal packing but adopt the structure of the underlying periodic potential such that the clusters exhibit a dominant square ordering (Figs. 1d and 2b). Interestingly, these square-ordered percolating structures are still continuously in motion (Supplementary Movie 2) and exhibit active diffusion at late times (as we show later). Hence, we call these structures “active adaptolates”.

Row (i): Steady-state snapshots for a–e increasing values of the dimensionless barrier height V. Each colored disc denotes an active Brownian particle (ABP) with the color indicating their cluster-ID, i.e., the index of the cluster they belong to. Row (ii): Zoomed snapshots (indicated by the black squares in row (i)) show the local packing geometry. Row (iii): Zoomed snapshots showing the particle speed, averaged over 100 frames in the steady-state. Parameters: Péclet number Pe = 300rc, packing fraction ϕ = 0.5, spatial periodicity of the potential landscape L = rc and WCA potential strength \(\epsilon =300{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), where rc is the WCA potential distance cutoff.

Structural characterization of different phases

To characterize the observed phases, we examine the distribution of the local density ρ of the ABPs for different lattice heights (Fig. 2a). We partition the system into Voronoi cells, each cell containing a single ABP, and compute the local density by determining the ratio of the ABP’s occupied area to its corresponding Voronoi cell area. In the absence of the lattice and for low lattice height (\(V=60{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\)), we observe a bimodal local density distribution, signifying MIPS42,59. These peaks at ρ ~ 0.05 and ρ ~ 0.72 correspond to the co-existing low-density gas-like and high-density liquid-like (hexagonal packing) phases, respectively. The local structure of these phases can be characterized using the global hexatic ψ6 and quartic ψ4 bond order parameters (see Supplementary Note 1) whose values are 1 for perfect hexatic and square crystals, respectively36,42. For \(V \, \lesssim \, 60{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), ψ6 > 0.8 (Fig. 2b), which indicates that the ABPs are hexagonally packed within the dense clusters.

a Distribution P(ρ) of the local density ρ of ABPs for different barrier heights V. b Global bond order parameters ψ4 (orange triangles) and ψ6 (blue circles) as a function of V, averaged over different snapshots in the stationary state. The boundaries between MIPS, active adaptolates (AA), and the trapped phase correspond to the peaks of the susceptibility. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean and are smaller than the data markers.

At intermediate barrier heights (\(65{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2} \, \lesssim \, V \, \lesssim \, 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\)), the distinct peak at ρ ~ 0.05 vanishes (Fig. 2a), indicating that the active adaptolates are not phase separated. Instead, the density distribution for \(V=70{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) features a single broad maximum at ρ ~ 0.62, which corresponds to the square packing density (\(=\pi /4{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\)) of the ABPs in the square lattice. As V is increased further to \(V=87{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), the peak becomes narrower, indicating that most of the ABPs are now arranged in a square packing structure. This is consistent with the behavior of the bond order parameters in Fig. 2b, where we see that ψ6 decreases sharply as V is increased beyond \(60{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) accompanied by a simultaneous increase of ψ4. Overall, we have a lattice-induced transition from a phase-separated state with a hexagonal packing structure to a phase that adopts the structure of the underlying lattice while still requiring the interplay of activity and collision to exist. When V increases further, beyond \(120{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), the peak height at ρ ~ 0.62 decreases (Fig. 2a) because the square-ordered aggregates are gradually destroyed. Then, the ABPs are randomly and uniformly pinned to different lattice minima because they do not self-propel fast enough to cross the potential barriers. As a result, the local density of the ABPs decreases, and we observe multiple peaks emerging near ρ ~ ϕ = 0.5 (which is the mean density of the ABPs) corresponding to ABPs with less than four nearest neighbors at the adjacent minima. Since the square packing of the ABPs weakens due to the random filling of the square lattice, ψ4 also decreases (Fig. 2b).

Fluctuations and phase boundaries

To characterize the transition from the MIPS and trapped phase to the active adaptolate phase, we determine the (normalized) mean largest cluster size nl, the (normalized) mean largest cluster extension dl and the susceptibility χ measuring the size fluctuations of the largest cluster (see Supplementary Note 2)43,44,60. dl quantifies the compactness of the largest cluster; the larger the value of dl, the less compact a cluster is. In the MIPS regime, nl ≈ 1 and dl ≈ 0.8 (Fig. 3a, inset) indicate that the ABPs form a large dense cluster. At intermediate lattice heights, where the AA phase is formed, nl slightly decreases to ≈0.8, whereas dl increases to its maximum value ≈1. This shows that the MIPS phase undergoes a qualitative structural change at intermediate lattice heights to form a less compact porous percolated space-filling cluster in which the local packing of the particles adopts the square geometry of the underlying lattice. For \(V \, \gtrsim \, 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), the percolated cluster breaks up into many smaller clusters (see Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2), leading to a drastic decrease in the values of nl and dl. The distinct peaks in susceptibility χ at \(V\approx 65{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) and \(\approx 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) indicate that the active adaptolate phase is separated from both the MIPS and the trapped phase by a phase transition, rather than emerging gradually in the form of a crossover.

a Susceptibility as a function of the reduced lattice height \(V/{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) showing the three different nonequilibrium phases in the background. The peaks in the susceptibility χ at \(V\approx 65{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) and \(\approx 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) denote the separation of the active adaptolate phase from the MIPS and the trapped phase, respectively. Inset: Normalized mean largest cluster size nl (blue circles) and normalized mean largest cluster extension dl (orange checks). b, e Binder cumulant U4 as a function of \(V/{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) and Pe/rc, respectively, for four different system sizes Ld. c, d Finite-size scaling of nl and χ for different Ld. The collapse occurs for the critical exponents β ≈ 0.16, γ ≈ 2.38, ν ≈ 1.3 and critical lattice height \({V}_{c}\approx 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), indicating that the transition between the AA and trapped phase is a proper phase transition that belongs to the 2D percolation universality class. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean and are smaller than the data markers.

To verify this, we perform a finite-size scaling analysis for different system sizes Ld = 16rc, 32rc, 64rc, and 128rc with V as the control parameter. For a percolation phase transition, the order parameter nl and susceptibility χ are expected to scale as \({n}_{{{{\rm{l}}}}}({L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}})={L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{-\beta /\nu }f(| V-{V}_{c}| {L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{1/\nu })\) and \(\chi ({L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}})={L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{\gamma /\nu }g(| V-{V}_{c}| {L}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{1/\nu })\) for different Ld43,61,62. Here, Vc is the critical lattice potential height at the transition point, f and g are the scaling functions, and β, γ, and ν are the critical exponents. We calculate the fourth-order Binder cumulant \({U}_{4}=1-\langle {d}_{{{{\rm{l}}}}}^{4}\rangle /3{\langle {d}_{{{{\rm{l}}}}}^{2}\rangle }^{2}\) of the order parameter dl for different Ld (Fig. 3b). The crossing point of these curves gives the critical parameter Vc63,64, which we estimate to be \(\approx 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\pm 4\). We estimate the critical exponents to be β ≈ 0.16 ± 0.03, γ ≈ 2.38 ± 0.37, and ν ≈ 1.3 ± 0.2 (see Supplementary Note 3), which are close to the known universal exponents for the 2D percolation transition (β ≈ 0.14, γ ≈ 2.38, ν ≈ 1.33)61. Using these values and \({V}_{c}\approx 96{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), we find a collapse of nl and χ (Fig. 3c, d) at the critical point Vc for different system sizes Ld, suggesting that the transition from the adaptolate to the trapped phase is indeed a phase transition that likely belongs to the (static) percolation universality class. We also verified that the cluster size distribution exhibits a power-law decay and the clusters have a fractal dimension of 1.895 ± 0.006 at the critical point, both of which are expected for a percolation transition60 (see Supplementary Fig. S3). In addition, we stress that the adaptolate phase features significant, ongoing intrinsic dynamics (active diffusion at late times); see Fig. 4.

Mean-squared displacement \(\overline{\delta {r}^{2}(t)}\) of the ABPs as a function of time t for different barrier height V. Inset: Late-time diffusion coefficient D of the ABPs, normalized by the diffusion coefficient D0 of passive particles for V = 0, as a function of V. Notice that D decays much slower and smoother than the hexatic order parameter ψ6 (Fig. 2b). The figure indicates that the particles in the active adaptolate phase move one to two orders of magnitude faster than free passive Brownian particles.

To show that the active adaptolate phase is activity-induced, we also performed a finite-size scaling analysis with the Péclet number Pe as the control parameter (and fixing V = Vc) and observed that the AA phase only emerges when the activity surpasses a critical threshold, Pec ≈ 302rc (Fig. 3e), showing that activity is crucial to realize such percolating dynamic clusters that adopt the structure of the underlying potential landscape (see Supplementary Fig. S4 for finite-size scaling of nl and χ for different Pe). We verified that the AA phase forms at higher packing fractions, too (see Supplementary Fig. S5). To distinguish the AA phase from equilibrium systems, we have explored the effect of a lattice potential on phase-separating passive Lennard-Jones particles. Here, we also observe percolating structures that adopt lattice geometry (see Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. S6). However, these structures are not dynamic and exhibit a late-time diffusion coefficient of three to four orders of magnitude lower than active adaptolates (see Supplementary Fig. S7). Additionally, the gas microbubbles65,66,67 within the AA phase (identified using AMEP68) show arrested coarsening over time as in MIPS microbubbles67 with a converged bubble size distribution consistent with predictions for active bubble phases65. In contrast, those in the passive percolating phase show long-term coarsening (see Supplementary Figs. S8 and S9).

Dynamical characterization of different phases

We characterize the dynamical properties of the different phases based on the mean-squared displacement (MSD) \(\overline{\delta {r}^{2}(t)}=\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }_{i = 1}^{N}{\left({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}(t)-{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}(0)\right)}^{2}\) of the ABPs. For \(V \, \lesssim \, 65{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) (MIPS phase), the ABPs exhibit a super-diffusive behavior at intermediate times with \(\overline{\delta {r}^{2}(t)} \sim {t}^{2}\), followed by a diffusive behavior with \(\overline{\delta {r}^{2}(t)} \sim t\) at longer times (Fig. 4). Even at intermediate barrier heights of \(V=70{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) and \(V=87{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\), where square-ordered AA phase is formed, the ABPs move diffusively with \(\overline{\delta {r}^{2}(t)} \sim t\) at late times with a late-time diffusion coefficient \(D={\lim }_{t\to \infty }\frac{1}{4}\frac{d\,\overline{\delta {r}^{2}(t)}}{dt}\)69 (Fig. 4, inset) that is about 10–102 times larger than for passive particles. This shows that although the percolating aggregates adopt the underlying structure of the lattice, they are highly dynamic and exhibit dynamical properties similar to active particles in the absence of the lattice. A steeper barrier height decreases the long-time MSD of the ABPs and for \(V=150{r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{2}\) their dynamics is almost frozen on the timescale of our simulations, leading to the trapped phase.

Conclusions

This work shows that the concept of laser-induced freezing and melting is not limited to passive systems, but can be extended to active colloids, where it results in a so-far unknown phase of active matter. This phase requires activity to emerge and is separated from the trapped and molten phases by distinct peaks in the susceptibility, i.e., by sharp transitions. As its defining feature, this phase is characterized by a system-spanning percolated large-scale structure with a local packing geometry that adopts the structure of an underlying periodic potential and persistent active diffusive dynamics. Overall, the present work opens a route towards controlling intrinsic properties of active matter with structured external fields. While our current study focuses on 2D systems, extending this framework to 3D setups (e.g., active colloid suspensions in 3D optical lattices) would likely yield even more intricate adaptolate structures with complex connectivity. Additionally, a quantitative theoretical analysis of the emergence of the active adaptolates phase in terms of escape rate problems in an effective potential landscape70,71 could be a topic for future investigation. However, to quantitatively predict the value of the potential barrier for which the adaptolates occur, one would need to generalize the framework of refs. 70,71 to higher persistence times and probably also to account for many-body effects. This work also invites future studies to explore additional properties of the AA phase, such as the (possibly negative) surface tension of the non-coarsening microbubbles.

Methods

The non-dimensional equations of motion presented in the main text are derived from the following physical model for overdamped Active Brownian Particles (ABPs). The position \({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }\) and orientation θi of the ith particle evolve according to the following dimensional Langevin equations:

Each particle has a diameter σ and self-propels with a constant speed v0 in the direction of its orientation vector \({{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}=(\cos {\theta }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}},\sin {\theta }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\). The particle’s translational dissipation coefficient is given by γt = kBT/Dt, where Dt is the translational diffusion coefficient, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the temperature. The rotational diffusion coefficient is Dr.

The forces on the particle are:

-

\({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} {{{\rm{lat}}}}}=-{\nabla }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }{U}^{{\prime} }({x}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} },{y}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} })\) is the force due to the external periodic potential, where \({U}^{{\prime} }({x}^{{\prime} },{y}^{{\prime} })={V}^{{\prime} }[{\cos }^{2}(\pi {x}^{{\prime} }/{L}^{{\prime} })+{\cos }^{2}(\pi {y}^{{\prime} }/{L}^{{\prime} })]\). \({V}^{{\prime} }\) is the potential height in units of energy and \({L}^{{\prime} }\) is the spatial periodicity in units of length.

-

\({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} {{{\rm{int}}}}}=-\mathop{\sum }_{j = 1,j\ne i}^{N}{\nabla }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }{U}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}^{{\prime} }\) is the total interaction force from other particles, derived from the Weeks-Chandler-Andersen potential \({U}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}^{{\prime} }=4{\epsilon }^{{\prime} }[{(\sigma /{r}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}^{{\prime} })}^{12}-{(\sigma /{r}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}^{{\prime} })}^{6}]+{\epsilon }^{{\prime} }\), for inter-particle distances \({r}_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}^{{\prime} } < {r}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}^{{\prime} }={2}^{1/6}\sigma\) and zero otherwise. The interaction energy is set by \({\epsilon }^{{\prime} }\).

The stochastic terms \({{\boldsymbol{\xi}} }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }({t}^{{\prime} })\) and \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }({t}^{{\prime} })\) are uncorrelated Gaussian white noises with zero mean and correlations given by \(\langle {{\boldsymbol{\xi}} }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}\alpha }^{{\prime} }({t}^{{\prime} }){{\boldsymbol{\xi}} }_{{{{\rm{j}}}}\beta }^{{\prime} }({s}^{{\prime} })\rangle ={\delta }_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}{\delta }_{\alpha \beta }\delta ({t}^{{\prime} }-{s}^{{\prime} })\) (where \(\alpha ,\beta \in \left\{{x}^{{\prime} },{y}^{{\prime} }\right\}\)) and \(\langle {\eta }_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{{\prime} }({t}^{{\prime} }){\eta }_{{{{\rm{j}}}}}^{{\prime} }({s}^{{\prime} })\rangle ={\delta }_{{{{\rm{ij}}}}}\delta ({t}^{{\prime} }-{s}^{{\prime} })\). The non-dimensional model in the main text is recovered by choosing the characteristic length and time scales as ru = σ and tu = σ2/Dt, respectively, and setting Dr = 3Dt/σ2.

The Eqs. (1) and (2) are numerically integrated using a forward Euler-Maruyama scheme with the LAMMPS open source package50,51 for about 1.25 × 104 particles using a timestep dt = 10−6 for a total time of ttot = 2 × 103 in a square domain of size Ld × Ld with periodic boundary conditions and Ld = 125rc.

Data availability

The data from numerical simulations are available under reasonable requests.

Code availability

The code to generate data, by using numerical simulations, is available under reasonable requests.

References

Jaksch, D., Bruder, C., Cirac, J. I., Gardiner, C. W. & Zoller, P. Cold bosonic atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3108–3111 (1998).

Greiner, M., Mandel, O., Esslinger, T., Hänsch, T. W. & Bloch, I. Quantum phase transition from a superfluid to a Mott insulator in a gas of ultracold atoms. Nature 415, 39–44 (2002).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Zwerger, W. Many-body physics with ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885–964 (2008).

Chowdhury, A., Ackerson, B. J. & Clark, N. A. Laser-induced freezing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 833–836 (1985).

Das, C., Chaudhuri, P., Sood, A. K. & Krishnamurthy, H. R. Laser-induced freezing in 2-D colloids. Curr. Sci. 80, 959–971 (2001).

Wei, Q.-H., Bechinger, C., Rudhardt, D. & Leiderer, P. Experimental study of laser-induced melting in two-dimensional colloids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2606–2609 (1998).

Reichhardt, C. & Olson, C. J. Novel colloidal crystalline states on two-dimensional periodic substrates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 248301 (2002).

Brunner, M. & Bechinger, C. Phase behavior of colloidal molecular crystals on triangular light lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 248302 (2002).

Han, K., Sokolov, A., Glatz, A. & Snezhko, A. Manipulation of self-organized multi-vortical states in active magnetic roller suspensions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 589, 171625 (2024).

Han, K., Glatz, A. & Snezhko, A. Globally correlated states and control of vortex lattices in active roller fluids. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023040 (2023).

Fernandez-Rodriguez, M. A. et al. Feedback-controlled active Brownian colloids with space-dependent rotational dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 4223 (2020).

Bechinger, C. et al. Active particles in complex and crowded environments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 045006 (2016).

De Magistris, G. & Marenduzzo, D. An introduction to the physics of active matter. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 418, 65–77 (2015).

Ramaswamy, S. The mechanics and statistics of active matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 1, 323–345 (2010).

Zöttl, A. & Stark, H. Modeling active colloids: from active Brownian particles to hydrodynamic and chemical fields. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 14, null (2023).

Zöttl, A. & Stark, H. Emergent behavior in active colloids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 253001 (2016).

Liebchen, B. & Mukhopadhyay, A. K. Interactions in active colloids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 083002 (2021).

Howse, J. R. et al. Self-motile colloidal particles: from directed propulsion to random walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 048102 (2007).

Wang, W., Lv, X., Moran, J. L., Duan, S. & Zhou, C. A practical guide to active colloids: choosing synthetic model systems for soft matter physics research. Soft Matter 16, 3846–3868 (2020).

Ginot, F., Theurkauff, I., Detcheverry, F., Ybert, C. & Cottin-Bizonne, C. Aggregation-fragmentation and individual dynamics of active clusters. Nat. Commun. 9, 696 (2018).

Buttinoni, I. et al. Dynamical clustering and phase separation in suspensions of self-propelled colloidal particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 238301 (2013).

Palacci, J., Sacanna, S., Steinberg, A. P., Pine, D. J. & Chaikin, P. M. Living crystals of light-activated colloidal surfers. Science 339, 936–940 (2013).

Hokmabad, B. V. et al. Emergence of bimodal motility in active droplets. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011043 (2021).

Izzet, A. et al. Tunable persistent random walk in swimming droplets. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021035 (2020).

Maass, C. C., Krüger, C., Herminghaus, S. & Bahr, C. Swimming droplets. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 7, 171–193 (2016).

Michelin, S. Self-propulsion of chemically active droplets. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 55, 77–101 (2023).

Feng, K. et al. Self-solidifying active droplets showing memory-induced chirality. Adv. Sci. 10, 2300866 (2023).

Scholz, C., D’Silva, S. & Pöschel, T. Ratcheting and tumbling motion of vibrots. New J. Phys. 18, 123001 (2016).

Kudrolli, A., Lumay, G., Volfson, D. & Tsimring, L. S. Swarming and swirling in self-propelled polar granular rods. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 058001 (2008).

Dauchot, O. & Démery, V. Dynamics of a self-propelled particle in a harmonic trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 068002 (2019).

Walsh, L. et al. Noise and diffusion of a vibrated self-propelled granular particle. Soft Matter 13, 8964–8968 (2017).

Aranson, I. S. Bacterial active matter. Rep. Prog. Phys. 85, 076601 (2022).

Elgeti, J., Winkler, R. G. & Gompper, G. Physics of microswimmers—single particle motion and collective behavior: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 056601 (2015).

Koch, D. L. & Subramanian, G. Collective hydrodynamics of swimming microorganisms: living fluids. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 43, 637–659 (2011).

Cates, M. E. & Tailleur, J. Motility-induced phase separation. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 219–244 (2015).

Digregorio, P. et al. Full phase diagram of active Brownian disks: from melting to motility-induced phase separation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 098003 (2018).

Stenhammar, J., Tiribocchi, A., Allen, R. J., Marenduzzo, D. & Cates, M. E. Continuum theory of phase separation kinetics for active brownian particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 145702 (2013).

Turci, F. & Wilding, N. B. Phase separation and multibody effects in three-dimensional active Brownian particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 038002 (2021).

Anderson, C. & Fernandez-Nieves, A. Social interactions lead to motility-induced phase separation in fire ants. Nat. Commun. 13, 6710 (2022).

Mandal, S., Liebchen, B. & Löwen, H. Motility-induced temperature difference in coexisting phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 228001 (2019).

Caprini, L., Marini Bettolo Marconi, U. & Puglisi, A. Spontaneous velocity alignment in motility-induced phase separation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 078001 (2020).

Klamser, J. U., Kapfer, S. C. & Krauth, W. Thermodynamic phases in two-dimensional active matter. Nat. Commun. 9, 5045 (2018).

Kyriakopoulos, N., Chaté, H. & Ginelli, F. Clustering and anisotropic correlated percolation in polar flocks. Phys. Rev. E 100, 022606 (2019).

Sanoria, M., Chelakkot, R. & Nandi, A. Percolation transition in phase-separating active fluid. Phys. Rev. E 106, 034605 (2022).

Evans, D., Martín-Roca, J., Harmer, N. J., Valeriani, C. & Miller, M. A. Re-entrant percolation in active Brownian hard disks. Soft Matter 20, 7484–7492 (2024).

Weeks, J. D., Chandler, D. & Andersen, H. C. Role of repulsive forces in determining the equilibrium structure of simple liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 54, 5237–5247 (1971).

Loudiyi, K. & Ackerson, B. J. Direct observation of laser induced freezing. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 184, 1–25 (1992).

Zemanek, P., Siler, M., Karasek, V. & Cizmar, T. Behavior of submicron colloids in two-dimensional optical lattice. In Proc. Optical Trapping and Optical Micromanipulation II Vol. 5930, 432–438 (SPIE, 2005).

Buttinoni, I., Caprini, L., Alvarez, L., Schwarzendahl, F. J. & Löwen, H. Active colloids in harmonic optical potentials(a). EPL 140, 27001 (2022).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Thompson, A. P. et al. Lammps—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Tailleur, J. & Cates, M. E. Statistical mechanics of interacting run-and-tumble bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 218103 (2008).

Cates, M. E. & Tailleur, J. When are active Brownian particles and run-and-tumble particles equivalent? consequences for motility-induced phase separation. EPL 101, 20010 (2013).

Speck, T., Bialké, J., Menzel, A. M. & Löwen, H. Effective Cahn-Hilliard equation for the phase separation of active Brownian particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 218304 (2014).

Hecht, L., Mandal, S., Löwen, H. & Liebchen, B. Active refrigerators powered by inertia. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 178001 (2022).

Maloney, R. C., Liao, G.-J., Klapp, S. H. L. & Hall, C. K. Clustering and phase separation in mixtures of dipolar and active particles. Soft Matter 16, 3779–3791 (2020).

Ma, Z. & Ni, R. Dynamical clustering interrupts motility-induced phase separation in chiral active Brownian particles. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 021102 (2022).

Paoluzzi, M., Levis, D. & Pagonabarraga, I. From motility-induced phase-separation to glassiness in dense active matter. Commun. Phys. 5, 1–10 (2022).

Stenhammar, J., Marenduzzo, D., Allen, R. J. & Cates, M. E. Phase behaviour of active brownian particles: the role of dimensionality. Soft Matter 10, 1489–1499 (2014).

Levis, D. & Berthier, L. Clustering and heterogeneous dynamics in a kinetic Monte Carlo model of self-propelled hard disks. Phys. Rev. E 89, 062301 (2014).

Gawlinski, E. T. & Stanley, H. E. Continuum percolation in two dimensions: Monte Carlo tests of scaling and universality for non-interacting discs. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 14, L291 (1981).

Heermann, D. W. & Stauffer, D. Influence of boundary conditions on square bond percolation near pc. Z. Phys. B Condens. Matter 40, 133–136 (1980).

Binder, K. Critical properties from Monte Carlo coarse graining and renormalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 693–696 (1981).

Binder, K. & Heermann, D. W. Monte Carlo Simulation in Statistical Physics: An Introduction. Graduate Texts in Physics (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Tjhung, E., Nardini, C. & Cates, M. E. Cluster phases and bubbly phase separation in active fluids: reversal of the Ostwald process. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031080 (2018).

Shi, X.-q, Fausti, G., Chaté, H., Nardini, C. & Solon, A. Self-organized critical coexistence phase in repulsive active particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 168001 (2020).

Caporusso, C. B., Digregorio, P., Levis, D., Cugliandolo, L. F. & Gonnella, G. Motility-induced microphase and macrophase separation in a two-dimensional active Brownian particle system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 178004 (2020).

Hecht, L. et al. AMEP: the active matter evaluation package for Python. Comput. Phys. Commun. 309, 109483 (2025).

Zeitz, M., Wolff, K. & Stark, H. Active Brownian particles moving in a random Lorentz gas. Eur. Phys. J. E 40, 23 (2017).

Sharma, A., Wittmann, R. & Brader, J. M. Escape rate of active particles in the effective equilibrium approach. Phys. Rev. E 95, 012115 (2017).

Scacchi, A. & Sharma, A. Mean first passage time of active Brownian particle in one dimension. Mol. Phys. 116, 460–464 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) through project number 233630050 (TRR-146).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.M. conducted the research, performed numerical simulations, and analyzed the data. A.K.M. and B.L. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. A.K.M., B.L. and P.S. contributed to the project planning, data interpretation, and manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mukhopadhyay, A.K., Schmelcher, P. & Liebchen, B. Active adaptolates featuring motility-induced percolating structures with an adaptive packing geometry. Commun Phys 8, 343 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02265-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02265-0