Abstract

Understanding optical properties in the extreme ultraviolet (XUV) region requires access to the dynamical electronic wave functions across a broad energy range. However, time-resolved spectroscopic tools to probe the real and imaginary parts of electric susceptibility in a wide portion of the XUV region remain limited. Here, we demonstrate transient complex refraction spectroscopy using double isolated attosecond pulses (DAPs) to investigate dynamical autoionization in argon. By combining DAPs-based spectral interferometry with complex Fourier analysis, we characterized the relative amplitude and phase of electronic dipoles excited from inner subshells to autoionizing states, which are modified by a few-cycle near-infrared femtosecond pulse. By precisely tuning the temporal gate width between DAPs, we could unveil the temporal behavior of the complex refractive index. Our spectroscopic scheme with DAPs will thus help to reveal the phase-resolved ultrafast electron dynamics and paves the way for attosecond coherent control in a broad XUV spectral range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent progress on attosecond pulse generation technology has provided researchers with a means to study excitations from inner-subshell and core excited states to valence states over a wide spectroscopic range from the extreme ultraviolet (XUV) region to the soft x-ray region. In particular, element-specific core-level probing at individual energy levels has been studied using ultrashort light sources and the gathered information has been widely utilized in the compositional analysis of materials1,2. Recently, the realization of isolated attosecond pulse (IAP) generation has enabled inner-core electron dynamics such as Auger processes3,4 and autoionization5 processes to be measured with extremely high temporal resolution.

Since various physical quantities, such as refractive index, permittivity, and atomic scattering factor, are described as frequency-dependent complex parameters6, the observation of the complex response, i.e. the amplitude and dipole phase of the core electron for each energy state, is of great importance. Recently, the amplitude and phase of electron dipole oscillations in various processes have been investigated by using a combination of transient absorption and reflection spectroscopy involving phase-locked IAPs and near-infrared (NIR) femtosecond pulses of several periods7,8 and theoretical calculations9 or iterative reconstruction methods10,11 or by using interferometric optical schemes on two phase-locked attosecond pulse trains (APTs)12,13,14,15,16. These interferometric optical schemes can reconstruct the phase and amplitude even with single-shot detection through a simple Fourier analysis. In particular, transient measurements of the complex refractive index have recently been achieved by combining APTs and near-infrared pulses interfering in the spatial domain17. However, the APTs could not be used to reveal the dynamics of the complex refractive index because it has a NIR pulse width of approximately 50 fs. In addition, APTs have a discrete energy spectrum derived from the optical period of the driving laser field, making it difficult to determine the complex response across multiple exciting electron levels lying in a broad XUV region.

On the other hand, IAPs have a huge advantage for observing multiple core-electron dynamics because they have continuous and broadband spectra, allowing detection of the complex response over a wide continuous spectral region18,19,20. Previously, we developed an interference spectroscopy system with two IAPs21. Here, we have further developed an attosecond transient refraction spectroscopy with three optical pulses: double attosecond pulses (DAPs) composed of two IAPs and a few-cycle NIR femtosecond pulse. The advantage of this method is its ability to tune the temporal gate width between DAPs, which enables the intervals of the interference fringes to be changed to match the timescale of the dynamics of interest. By harnessing this spectroscopic scheme, we have revealed the complex dynamics in argon (Ar) atomic core electrons in the XUV region. The spectrally resolved transient refraction traces, reflecting the temporal behavior of the complex refractive index across a wide range of the XUV region, revealed the dynamics of the core electrons. The results show that our spectroscopic scheme can be used for exploring individual inner-shell properties of materials over a broad range of the XUV region.

Results and discussion

Transient complex refraction spectroscopy with double attosecond pulses

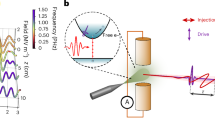

To interrogate the complex dynamics of argon atomic core electrons in the XUV region, we utilized attosecond transient refraction spectroscopy as illustrated in Fig. 1a. An IAP was generated using a double optical gating (DOG) technique with Ar gas22, while a carrier-envelope-phase stabilized few-cycle NIR pulse was directly used to modulate XUV polarizations for transient complex refraction spectroscopy. The IAP was split into two pulses by using a reflection beam-splitting mirror (BSM) equipped with a piezoelectric transducer to produce DAPs with a proper delay time21. The DAPs were then sent to a molybdenum silicon (Mo/Si) multilayer-coated spherical focusing mirror. The NIR pulse was focused on the target Ar gas together with the DAPs. After passing through the target, the DAPs were sent to a second Mo/Si focusing mirror and were then refocused and spatially overlapped on an entrance slit of an XUV spectrometer combined with an X-ray charge coupled device (XCCD) camera to measure the spectral interferogram constructed by the DAPs (see the Methods section for details).

a Schematic illustration of transient refraction spectroscopy with DAPs. BSM: beam-splitting mirror. Mo/Si: Mo/Si multilayer-coated spherical mirror. Grating: diffraction grating. XCCD: X-ray CCD camera. b The energy level diagram of an Ar atom. Blue arrows represent excitations via DAPs from the 3s23p6 ground state to the 3s3p64p, 3s3p65p, and 3s3p66p autoionizing states. Red arrows show the excitations via the near-infrared (NIR) pulse to the 3s3p6 state. Γ is the decay time of each autoionization state6. c The spectral interferogram with/without Ar gas using only DAPs. The dashed lines represent the transitions from the ground state to the autoionizing states of Ar. The inset shows the isolated attosecond pulse (IAP) spectrum, which was obtained by integrating the spatially resolved spectral interference waveforms over the entire spatial range. d Optical density spectrum of Ar gas. This spectrum is obtained from (c). These waveforms were obtained by averaging 30 measurements. The error bars indicate the root mean square error.

Figure 1b shows the energy level diagram of an Ar atom. Blue arrows represent the excitations from the 3s23p6 ground state to the 3s3p64p (26.6 eV), 3s3p65p (28.0 eV), and 3s3p66p (28.5 eV) autoionizing states, which corresponds to the transitions from the 3s inner-subshell to the np unoccupied valence states23,24. The excited electrons in each state induced by the DAPs were autoionized to the 3s23p5 state (Ar+) with decay times of 8.2 fs, 23.3 fs, and 52.2 fs, respectively24. Red arrows show the excitation by the NIR pulse to the 3s3p6 (Ar*+) state. Figure 1c shows the spectral interferograms with/without Ar atoms when using only DAPs with a 5-fs delay time. A periodic modulation (0.83 eV) accompanied with a temporal delay between DAPs appears on the spectral interferograms which were absent in the spectrum of IAP as shown in the inset. The blue line shows a typical interferogram transmitted through the target Ar gas. Three absorption peaks, which correspond to the autoionizing states of the 3s3p64p, 3s3p65p and 3s3p66p states, are clearly visible in the absorbance spectrum obtained from the two interferograms (Fig. 1d).

Dynamical characterization of phase differences in DAP due to Ar autoionizing states

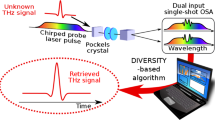

Here, we will explain the concept of transient complex refraction spectroscopy using DAP for characterizing the dynamical changes in the complex refractive index due to autoionization states of Ar. When an attosecond pulse is incident on a sample Ar atom, electron excitation occurs at a resonance energy of a specific transition to the autoionization state (excitations from the 3s23p6 state to the 3s3p6np (n = 4, 5, 6) states), inducing dipole oscillation due to electron polarization. This polarization can be measured as the transmission spectrum and can be analyzed as the changes in the complex refractive index of the sample. When DAPs are incident on the sample, dipole oscillations induced by two attosecond pulses will interfere with each other, resulting in the spectral interferences imposed on the transmission spectrum as shown in Fig. 1c. The dipole oscillation is schematically depicted as the dashed blue lines in the lower part of Fig. 2a, b.

a, b Schematic diagram of the transient complex refraction spectroscopy with double attosecond pulses (DAPs) having different \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}\) delays of 5 and 10 fs to characterize nonlinear complex dipole phase in autoionizing states of Ar. The blue solid and dotted lines represent the dipole oscillations due to resonant excitation of autoionization states by DAPs. Near-infrared (NIR) induced changes due to re-excitation to the Ar*+ state is also shown by the red solid line. c, d Measured transient spectrograms with \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\) 5 fs and \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\)10 fs. e, f Reconstructed relative amplitudes with τDAPs = 5 fs and τDAPs = 10 fs. g, h Reconstructed relative phase with \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\) 5 fs and \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\)10 fs.

When NIR is irradiated, the dipole oscillations are modulated as depicted by the red solid lines in Fig. 2a, b because of additional excitations from the 3s3p6np states to the Ar*+ state and/or from the 3s3p64p state to the 3s3p64d state. Since the superposition of dipole decay oscillations can be measured as spectral interference fringes, the modulation by NIR irradiation can be detected as a change in the spectral interference fringes. The changes in the amplitude of interference fringes have information on the imaginary part of refractive index change, and that in the phase have information on the real part. This is the information that our transient complex refraction spectroscopy using DAPs is trying to capture in the experiment.

Here, we define several parameters of our experiment as shown in Fig. 2a, b. τDAPs corresponds to the effective temporal gate width for detecting the complex dipole phase induced by the excitation from an inner-subshell to autoionizing states in the region of 25−29 eV, while τNIR-DAPs represents the time delay between the NIR pulse and the first attosecond pulse. The time origin is defined as the time at which the NIR pulse and the first attosecond pulse have maximum overlap. Hereafter, the transitions from the 3s23p6 ground state to the 3 s3p64p, 3 s3p65p, and 3s3p66p autoionizing states will simply be denoted as 3s-4p, 3s-5p, and 3s-6p, respectively. By monitoring the spectral interferogram constructed by the transmitted DAPs, the differential amplitude and phase of the dipole phase transiently modified with the NIR pulse can be determined via a simple Fourier transformation. After that, by scanning the τNIR-DAPs delay, real-time monitoring of the complex dipole phase of Ar autoionizing states can be achieved through the determination of the transient relative amplitude and the phase. Details of the Fourier analysis are described in the Methods section.

Figure 2c, d show the transient spectrograms measured in a wide spectral region (25–29 eV) with τDAPs = 5 fs and τDAPs = 10 fs delays between DAPs, respectively. These spectrograms were generated by arranging NIR-irradiated spectral interferograms in order of the delay time τNIR-DAPs. The detailed procedure is described in the Methods section. The NIR pulse reaches the target earlier than the first attosecond pulse for the negative τNIR-DAPs delay, while vice versa for the positive delay. As can be seen in Fig. 2c, d, the spectral intensities at the 3s-4p and 3s-5p transitions are reduced by the NIR pulse at around zero τNIR-DAPs delay, intuitively indicating a modification of the dipole moment. Note that a similar modulation was reported in a pioneering work based on the conventional transient absorption spectroscopy using IAP5.

To analyze the transient spectrograms shown in Fig. 2c, d, we performed Fourier analysis on the component of the spectral interference fringe in the transient spectrograms and extracted the amplitude and phase information. The details of Fourier analysis are described in the Methods section. Figure 2e, f, g, h show temporal evolution of the relative amplitude and phase between the data with and without NIR irradiation for τDAPs = 5 fs and 10 fs, respectively. The relative amplitude and phase correspond to the real and imaginary parts of the NIR-induced change in transmittance at each time delay of τNIR-DAPs. In the figures, more pronounced transient changes in both relative amplitude and phase are visible at resonances of the autoionization states of the 3s-4p and 3s-5p states during about 30 fs around the time origin. We could clearly observe that the spectral width of the amplitude was broadened by the NIR pump with an amount of a few hundred meV with slight splitting (Fig. 2e, f), and that the NIR-induced phase change flips sign around the 3s-4p state (Fig. 2g, h).

According to the pioneering work5, two possible origins can be considered for the broadening and splitting of the 3s-4p and 3s-5p autoionization peaks when the DAPs and NIR pulses overlap in the time domain. One is the acceleration of the decay process due to two-photon excitation coupling between the autoionization level and the Ar*+ (3s3p6εl) continuum. This was observed as a dominant factor when a peak intensity NIR pulse is 5 × 1011 W/cm2. The other one is AC Stark shift and splitting of 100–200 meV due to a strong coupling between the 3s3p64p and 3s3p64d autoionizing states, which were observed under NIR pulse irradiation with a peak intensity above 1012 W/cm2 5,25. The asymmetric shape of the splitting recognized in Fig. 2c, e might originate from the Rabi oscillation between the 3s3p64p and 3s3p64d autoionizing states, which show an asymmetric Fano shape5.

Interestingly, the relative amplitude data exhibited a different appearance for τDAPs = 5fs (Fig. 2e) and 10 fs (Fig. 2f). One possible origin of the difference is that the resonant two-photon coupling between the 3s3p64p and 3s3p64d autoionizing states because the NIR with 6.5 fs duration and IAP efficiently induce the resonant transition when they overlap (see Fig. 1b). Since the decay time of the 4p state is 8.2 fs, both dipole oscillations induced by the DAPs with τDAPs = 5 fs can be strongly coupled with the 4 d state by the NIR before they fully decay. In contrast, one of the DAPs is less affected by the resonance in the case with τDAPs = 10 fs because the decay is faster than the pulse interval.

The time variation of the differential phase in Fig. 2g, h shows a phase flip around the 3s-4p and 3s-5p transitions both for the τDAPs = 5 fs and 10 fs data. The phase shift of π in the phase image across the excitation energy might originate from the NIR-induced change in the real part of the refractive index, resulting in the sign-inverted behavior around the resonance frequency. Note that phase inversion at τDAPs = 10 fs is clearer than that at τDAPs = 5 fs in spite of the longer temporal gate. This is probably because the narrower spectral interference fringe generated with the longer gate width of the DAPs enhances the sensitivity to the phase change. Namely, for τDAPs = 5 fs, the NIR pulse affects the two EUV-excited electron dipoles simultaneously. On the other hand, for τDAPs = 10 fs, the NIR pulse may affect one dipole and not the other. Therefore, a larger phase difference between these two dipoles would be induced by the NIR pulse. Moreover, the narrower spectral interference fringe, which corresponds to a higher spectral frequency, is inherently advantageous to the Fourier filtering of the AC interference component from the background corresponding to the DC component, because the interference component was sufficiently far apart from the DC background component in the Fourier domain. Thus, the arbitrary tunability of the temporal gate width between DAPs afforded by our method enables us to not only control the dynamical behavior of the IAP-induced dipole oscillation but optimize the trade-off relation between the temporal resolution and the phase sensitivity.

To analyze further the spectral changes, we derive the equations to relate the observed spectral amplitude and phase to the complex refractive index. The transmittance change calculated by taking the ratio between the spectra with and without NIR irradiation can be expressed as

where d is the sample thickness. In this equation, we could obtain the relation \(\Delta n=n\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}\,}\right)-n\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}+{\tau }_{{DAPs}}\right)\) and \(\triangle \kappa =\kappa \left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)+\kappa \left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}+{\tau }_{{DAPs}}\right)-2{\kappa }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) as shown in the Methods section. Therefore, Δn corresponds to the change in refractive index due to the gate width of DAPs, and ∆κ corresponds to the change in absorption due to NIR. Note that physical meaning of Δn and ∆κ are slightly different. Δn represents the difference between the DAPs, whereas ∆κ represents that between the data with and without the NIR irradiation.

Figure 3 shows the results of this calculation. Figures 3a, c plot ∆κ and ∆n as functions of photon energy with different τNIR-DAPs delays at τDAPs = 5 fs, and Figs. 3b, d are those at τDAPs = 10 fs. When τNIR-DAPs reaches 0, a rapid increase in ∆κ occurs around the peak position of the 3s-np (n = 4, 5, 6) transitions and ∆κ recovers to the original value after a few tens of fs. On the other hand, you can clearly observe that at the peak position of the 3s-4p transition of 26.6 eV, there is a positive change in differential refractive index ∆n on the lower-energy side and a negative ∆n change on the higher-energy side at τNIR-DAPs = 0 fs. A small, but similar ∆n changes are observed at around the 3s-5p transition in Fig. 3d and the 3s-4p transition in Fig. 3c. As we pointed out that the phase change for τDAPs = 10 fs is clearer than τDAPs = 5 fs, as shown in Fig. 2g, h, Fig. 3c, d also show that the change in refractive index for τDAPs = 5 fs is less pronounced than that for τDAPs = 10 fs. This is probably due to the enhancement of the sensitivity of relative phase change and the improvement of the signal-to-noise ratio in Fourier analysis. The observed differential values of the transient complex refractive index are on the order of 10-6−10-5, which is significantly smaller than the typical order of the refractive index 10−4 of Ar6. Thus, this result confirms that our method is sensitive enough to detect slight changes in the complex refractive index that are one or two orders of magnitude smaller than the nonperturbed value.

a, b Imaginary part of the relative complex refractive index changes with τDAPs = 5 fs and \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\)10 fs calculated from the relative amplitude shown in Fig. 2. These profiles are extracted and calculated from different \({\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\) delays of −20, 0 and 30 fs. c, d Real part of the relative complex refractive index changes with \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\) 5 fs and \({\tau }_{{DAPs}}=\)10 fs calculated from the relative phase shown in Fig. 2. The dashed lines indicate the 3s-4p, 3s-5p, and 3s-6p transitions. The shaded areas represent the error bars of complex refractive index, which were estimated from standard deviation of five consecutive measurements.

Figure 4 shows the temporal changes in ∆κ and ∆n at each autoionization state for τDAPs = 5 fs and τDAPs = 10 fs, i.e., (a) and (b) for 3s-4p and (c) and (d) for 3s-5p. Here, ∆κ is estimated by extracting the values around the energy of each autoionization state from the differential amplitude (Fig. 2e, f) for each τNIR-DAPs delay. On the other hand, ∆n is estimated by extracting the values around the negative phase peak of the differential phase (Fig. 2g, h) for each τNIR-DAPs delay (please also refer to the Methods section). In these procedures, the values were evaluated after averaging over several pixels around the center of each autoionization state. The decay profiles at each state were assumed to be exponential decays convolved with a Gaussian function of 6.5 fs, the pulse width of the NIR, occurring in the delay between DAPs. From the results of the global fitting, we estimated the decay times as 7.5 ± 0.8 fs and 8.6 ± 0.9 fs for 3s-4p, and 27.6 ± 4.5 fs and 22.5 ± 5.6 fs for 3s-5p, as shown by the solid curves in Fig. 4. These decay times represent the decay of the dipole oscillations that originate from the polarization of electrons excited to the autoionization states induced by the attosecond pulses. Because of the small change in ∆κ and ∆n, we could not estimate the decay time of 3s-6p. However, the obtained autoionization decay times for 3s-4p and 3s-5p, both for the real and imaginary part of the complex refractive index, are in close agreement with those obtained in a previous report5. This result suggests that our method of DAPs-based transient complex refraction spectroscopy is extremely valuable for measuring the phase-resolved dynamics of states with very short lifetimes, such as multiple inner-shell levels in a wide energy range corresponding to the XUV and soft X-ray regions.

a, b Decay profiles of the imaginary and real part of the relative complex refractive index changes at the 3s-4p transition, c, d those at the 3s-5p transition with τDAPs = 5fs and τDAPs = 10 fs. The red and blue symbols and lines correspond to\(\,\triangle \kappa\) and \(\triangle n\), respectively. Each dot represents the measured data, while each solid line shows a best-fit with a double exponential decay convolved with a pulse having a width of 6.5 fs. The decay time \(\tau\) was estimated as a global fitting variable for \(\triangle \kappa\) and \(\triangle n\).

Conclusion

We have demonstrated a scheme of transient complex refraction spectroscopy based on a combination of DAPs-based spectral interferometry and complex Fourier analysis with DAPs. By applying this scheme to electronic dipoles induced by a strong excitation from the inner-subshell to unoccupied autoionization states in atomic Ar, we found that the differential amplitude and phase of the electronic dipole were strongly modified by a few-cycle near-infrared femtosecond pulse in a wide range of the XUV region. Considering the recent technological advances in attosecond pulse generation, our scheme will be of use for measuring and even manipulating the dynamical amplitude and phase information of the electronic wave function on the attosecond timescale in a wide energy range from the XUV to soft x-ray regions.

Methods

Experimental setup

For the transient complex refraction spectroscopic experiments, we used a carrier-envelope-phase and beam-pointing stabilized few-cycle NIR driving pulse with 1.57-eV center photon energy, 6-fs duration, 500-µJ pulse energy and 3-kHz repetition rate. The few-cycle pulse was generated by compressing a 20-fs output from a Ti:sapphire amplifier system (Spectra Physics, FEMTOPPWER HE/HR CEP4) with the hollow core fiber compression technique. The IAP was generated using a DOG technique with Ar gas21. The DOG was composed of two quartz plates (270- and 480-μm-thick) and a β-BaB2O4 (BBO) crystal (140-μm-thick), making a temporal gate width that corresponded to a half cycle (1.3 fs) of the NIR pulse. The NIR driving pulse that was 9 mm in diameter was focused by a spherical mirror with a radius of curvature of 800 mm into a gas cell (3-mm interaction length) filled with Ar gas. The estimated spot size and Rayleigh length were 22 µm and 1.9 mm, respectively. The backing gas pressure was 9 mbar and the gas cell was set to approximately 2 mm after the geometrical focus position of the NIR pulse, whose values satisfied the optimal phase matching condition for high flux. The estimated peak intensity at the Ar gas was 1.6 × 1015 W/cm2.

To construct a spectroscopic scheme for transient complex refraction spectroscopy applicable to the XUV region, the generated IAP was divided into two pulses by using a reflection BSM equipped with a piezoelectric transducer with 1-nm distance resolution, which enabled DAPs to be generated with a proper delay time21. The DAPs were then sent to a Mo/Si mirror. The NIR pulse was focused on the target Ar gas jet together with DAPs, and the delay between NIR pulse and DAPs was tuned by a piezo stage with a temporal resolution of 6.7 as placed outside the vacuum chamber. The intensity of the NIR pulse at the target position was approximately 2 × 1012 W/cm2. The beamline of the NIR pulse was blocked by a mechanical shutter to perform the measurements with/without NIR pulses. The target Ar gas jet with an interaction length of 100 µm was installed at the focus position. Note that the three pulses (NIR pulse and DAPs) passing through the target precisely overlapped during the experiments. After passing through the target, the DAPs were sent to a second Mo/Si focusing mirror (400-mm radius of curvature) and then were refocused and spatially overlapping them on an entrance slit of the XUV spectrometer combined with an XCCD camera (Newton SO DO940P, Andor Oxford Instruments Inc.) to implement the transient complex refraction spectroscopic experiments. The spectrometer resolution was calibrated to be 100 meV by using the transition from the 3s23p6 ground state to the 3s3p64p (26.6 eV) state of Ar with an 80-meV linewidth. The effective target pressure and the atomic density during the experiments were estimated from ref. 6 as 100 Torr and 5.26 × 10−6 g/cm3, respectively.

Fourier analysis of transient changes in the spectrograms from the raw experimental images

Here, we provide a detailed description of the procedure used to generate the transient spectrograms as shown in Fig. 1c, Fig. 2c, d from raw XCCD images of the spatial-spectral interferograms and the subsequent Fourier analysis applied to the transient spectrograms. Each measured XCCD image shows a spatial-spectral interferogram with spatially tilted stripes as shown in our previous work21. This is due to the effect of the wavefronts of the DAPs beams, which result from spatially splitting a single IAP beam using BSM, being tilted in opposite directions. To obtain a spectral interferogram as shown in Fig. 1c, we spatially averaged over several rows of pixels in the central region of the spatial-spectral interferogram image. The transient spectrograms shown in Fig. 2c, d were generated by arranging each NIR-irradiated spectral interferogram in order of the delay time τNIR-DAPs, which corresponds to the Eq. (3) in the next sub section. Note that the spectral interference fringe disappears when spatially averaging over the whole region of the spatial-spectral interferogram image due to the wavefronts tilting in opposite directions of DAPs. The inset in Fig. 1c was obtained by this full spatial averaging procedure.

To extract the Fourier component of the interference, we first Fourier transform the extracted interferogram, and filtering out the direct current component21. By making complex inverse Fourier transformation, we could obtain the complex amplitude of the Fourier component of the interference. We then took the ratio between the complex amplitudes with and without the NIR pulses and plotted the amplitude and the phase as shown in Fig. 2e–h. The same procedure is applied to all the data with different τNIR-DAPs.

Transient changes in the interferograms and complex refractive indices

In this section, we calculate the relation between the experimental data and the complex refractive indices. The spectral interferogram by DAPs with delay (gate width) of τDAPs can be expressed as

where ω is frequency and A(ω) is the complex amplitude of each IAP. Assuming that \(\widetilde{t}\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)\) is the complex transmittance of a sample with a time delay τNIR-DAPs between the first IAP and NIR pulse, the spectral interferogram transmitting through the sample with NIR irradiation, which was plotted as a function of τNIR-DAPs in Fig. 2c, d, is given by

The term,

in Eq. (3) appears as an AC component in the Fourier spectrum, given that the ω dependence of \(\widetilde{t}\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)\) is sufficiently smoother than that of \({e}^{i\omega {\cdot \tau }_{{DAPs}}}\) in Eq. (4). Here, we define the complex transmittance as,

where \(n\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)\) and \(\kappa \left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)\) represent the real and imaginary parts of the transient complex refractive index at a time delay of τNIR-DAPs, respectively. The sample thickness and the wavelength of DAPs are represented by d and λ. On the other hand, the spectral interferogram transmitting through the sample without NIR irradiation is expressed as

where \({\widetilde{t}}_{0}\left(\omega \right)\) is the complex transmittance of the sample without NIR irradiation. According to the definition (5), the complex transmittance without NIR irradiation is expressed as

where n0(ω) and κ0(ω) represent the real and imaginary parts of the complex refractive index of the sample without NIR irradiation, respectively. The term,

in Eq. (6) appears as an AC component in the Fourier spectrum.

By calculating the ratio between Eq. (4) and eq. (8) with the real and imaginary parts of the complex refractive index, we could obtain the experimental value of the NIR-induced change in transmittance represented by the Eq. (1) as,

These real and imaginary parts of the exponent of exponential in the Eq. (9) correspond to the measured relative amplitude and phase, which are plotted in Fig. 2e, f, g, h, respectively. By comparing the real and imaginary parts of the experimental transmittance with this equation, we could obtain the relative complex refractive index changes, \(\triangle n\equiv n\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)-n\left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}+{\tau }_{{DAPs}}\right)\) and \(\triangle \kappa \equiv \kappa \left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}\right)+\kappa \left(\omega ,\,{\tau }_{{NIR}-{DAPs}}+{\tau }_{{DAPs}}\right)-2{\kappa }_{0}\left(\omega \right)\), which are plotted in Figs. 3 and 4.

Data availability

All relevant data that support the findings in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data from Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 are available within Supplementary Data.

References

Geneaux, R., Marroux, H. J. B., Guggenmos, A., Neumark, D. M. & Leone, S. R. Transient absorption spectroscopy using high harmonic generation: a review of ultrafast X-ray dynamics in molecules and solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 377, 20170463 (2019).

Maiuri, M., Garavelli, M. & Cerullo, G. Ultrafast spectroscopy: state of the art and open challenges. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3–15 (2019).

Drescher, M. et al. Time-resolved atomic inner-shell spectroscopy. Nature 419, 803–807 (2002).

Kobayashi, Y., Timmers, H., Sabbar, M., Leone, S. R. & Neumark, D. M. Attosecond transient-absorption dynamics of xenon core-excited states in a strong driving field. Phys. Rev. A 95, 031401(R) (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Attosecond time-resolved autoionization of argon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 143002 (2010).

Henke, B. L., Gullikson, E. M. & Davis, J. C. X-ray interactions: photoabsorption, scattering, transmission, and reflection at E = 50-30,000 eV, Z = 1-92. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 54, 181–342 (1993).

Lucchini, M. et al. Attosecond dynamical Franz-Keldysh effect in polycrystalline diamond. Science 353, 916–919 (2016).

Lucchini, M. et al. Unravelling the intertwined atomic and bulk nature of localised excitons by attosecond spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 12, 1021 (2021).

Pabst, S. et al. Theory of attosecond transient-absorption spectroscopy of krypton for overlapping pump and probe pulses. Phys. Rev. A 86, 063411 (2012).

Borrego-Varillas, R. & Lucchini, M. Reconstruction of atomic resonances with attosecond streaking. Opt. Express 29, 9711 (2021).

Haessler, S. et al. Phase-resolved attosecond near-threshold photoionization of molecular nitrogen. Phys. Rev. A 80, 011404(R) (2009): Erratum Phys. Rev. A 106, 029901 (2022).

Bertrand, J. B., Wörner, H. J., Salières, P., Villeneuve, D. M. & Corkum, P. B. Linked attosecond phase interferometry for molecular frame measurements. Nat. Phys. 9, 174–178 (2013).

Wituschek, A. et al. Tracking attosecond electronic coherences using phase-manipulated extreme ultraviolet pulses. Nat. Commun. 11, 883 (2020).

Corsi, C., Pirri, A., Sali, E., Tortora, A. & Bellini, M. Direct interferometric measurement of the atomic dipole phase in high-order harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 153904 (2006).

Kanai, T., Takahashi, E. J., Nabekawa, Y. & Midorikawa, K. Destructive interference during high harmonic generation in mixed gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 153904 (2007).

Azoury, D. et al. Electronic wavefunctions probed by all-optical attosecond interferometry. Nat. Photonics 13, 54–59 (2018).

Leshchenko, V. et al. Kramers-Kronig relation in attosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Optica 10, 142–146 (2023).

Mashiko, H. et al. Multi-petahertz electron interference in Cr:Al2O3 solid-state material. Nat. Commun. 9, 1468 (2018).

Bernhardt, B. et al. High-spectral-resolution attosecond absorption spectroscopy of autoionization in xenon. Phys. Rev. A 89, 023408 (2014).

Chen, S., Wu, M., Gaarde, M. B. & Schafer, K. J. Quantum interference in attosecond transient absorption of laser-dressed helium atoms. Phys. Rev. A 87, 033408 (2013).

Mashiko, H. et al. Spatially resolved spectral phase interferometry with an isolated attosecond pulse. Opt. Express 28, 21025 (2020).

Mashiko, H. et al. Double optical gating of high-order harmonic generation with carrier-envelope phase stabilized lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 103906 (2008).

McConkey, J. W. & Preston, J. A. Autoionizing states in argon (electron scattering). J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Phys. 6, L138–L141 (1973).

Madden, R. P., Ederer, D. L. & Codling, K. Resonances in the photo-ionization continuum of Ar i (20-150 eV). Phys. Rev. 177, 136–151 (1969).

Chini, M. et al. Subcycle ac stark shift of helium excited states probed with isolated attosecond pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 073601 (2012).

Acknowledgements

K.O., H.M., I.K., and J.T. acknowledge support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (Grant Nos. 20H05670, 19H02637, and 20H05662). M.-C.C. acknowledges support by Taiwan National Science and Technology Council grants 112-2628-M-007-002- and 112-2112-M-007-052.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. and K.O. conceived and coordinated this project. A.O. and H.M. performed all measurements and analyzed all experimental data in cooperation with I.K., J.T. and K.O.. H.M. and M.-C.C. built the transient complex refraction spectroscopy with double attosecond pulses. A.O., H.M., I.K. and J.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Marcus Ossiander and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oshima, A., Mashiko, H., Chen, MC. et al. Spectral interferometric transient complex refraction spectroscopy with extreme ultraviolet double attosecond pulses. Commun Phys 8, 353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02269-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02269-w