Abstract

Hyperbolic lattices, a compelling platform for exploring matter in non-Euclidean space, challenge conventional band theory by invalidating Bloch’s theorem, necessitating the reexamination of fundamental concepts such as determining spectra in the thermodynamic limit for non-Hermitian systems. Here, we generalize non-Hermitian spectral topology to hyperbolic lattices by developing a reciprocal-space approach to determining such spectra under open boundary conditions, including spectral ranges and gaps. This method introduces supercells that encompass states allowed by non-Abelian translations and performs analytic continuation to leverage point-gap topology. Applying this method to a nonreciprocal model predicts spectral ranges under open boundary conditions that differ from those under periodic ones, revealing higher-dimensional skin effects supported by eigenstate and Green’s function analyses. We further employ a reciprocal semimetal model, uncovering states enabled by non-Abelian translations and topological phase transitions unique to non-Hermitian hyperbolic lattices. Our approach, robust and broadly applicable, offers a valuable framework for investigating spectral topology, non-Hermitian phases, and emergent phenomena in hyperbolic lattices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed a booming development of non-Hermitian physics1,2,3,4,5, with myriad applications spanning classical waves6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, ultracold atoms14, and open quantum systems15. The breakdown of Hermiticity introduces complex eigenenergies, resulting in spectral topology5. Unique to non-Hermitian systems, point gaps, characterized by eigenvalue winding numbers, spontaneously emerge2,16,17, while Hermitian systems only allow line gaps. Nontrivial point gaps underpin the non-Hermitian skin effect (NHSE)2,12,17,18,19,20,21, where bulk eigenstates localize at boundaries under open boundary conditions (OBCs) instead of extending as in Hermitian systems. Viewing NHSE from spectra shows eigenenergies under periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) constitute point gaps and vary remarkably under OBCs17. This discrepancy necessitates the calculation of OBC spectra in the thermodynamic limit at the unit-cell level, breeding the celebrated non-Bloch band theory2,22,23. To date, determining OBC spectral properties remains an active area of investigation and is still ongoing for higher-dimensional Euclidean lattices24,25,26(HDELs), which is a crucial issue for understanding phases of matter in real-world open systems. Although the spectral density of states (DOS) is sensitive to details such as geometry and impurities21,27,28, the universal OBC spectral range in arbitrary dimensions, denoted as \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\), is central to spectral topology and crucial because it is rooted in the inherent point-gap topology24,25,26. Both amoeba theory24 and uniform spectra formulation26 confirm \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\), underscoring the central role of point gaps and the analytic continuation of Bloch wavenumbers in non-Hermitian physics.

However, the point-gap topology is fundamentally broader than that of Bloch wavenumbers, as point gaps require only the existence of spectra, whereas Bloch wavenumbers rely on the translational group having one-dimensional irreducible representations—a condition not always satisfied. Hyperbolic lattices, constructed on a two-dimensional hyperbolic plane with constant negative curvature, exemplify such cases, differing from Euclidean lattices. Recent experimental achievements have positioned hyperbolic lattices as a brilliant platform to investigate quantum matter in non-Euclidean geometries29,30. Hyperbolic counterparts of phenomena like topological insulators31,32,33,34, Hofstadter states31,35, strong-correlated states36, Anderson localization37,38, and linear response theory39 have been proposed, with some realized experimentally29,30,32,34. Exploring physics and phenomena unique to hyperbolic lattices or lacking Euclidean analogs remains particularly compelling.

Unlike Euclidean lattices, hyperbolic lattices stand out due to negative curvature, and ensuingly, their translational groups, which are cornerstones in analyzing lattices, have been fundamentally altered40. Hyperbolic translation groups, known as Fuchsian groups, are non-Abelian and admit higher-dimensional irreducible representations, necessitating a generalization of the Bloch theorem41,42,43. This demand makes hyperbolic band theory (HBT) take shape, which incorporates Abelian [U(1)] and non-Abelian [U(d) for dimensions \(d > 1\)] components, corresponding to Abelian Bloch states (ABSs) and non-Abelian Bloch states (NABSs)41,42,43,44,45,46,47. In this manuscript, referring to a state as Abelian or non-Abelian signifies that the state possesses translational operations that either give rise to a Bloch phase or do not. Determining the spectra in the thermodynamic limit becomes first and foremost because the presence of NABSs invalidates standard approaches for Euclidean lattices. So far, several methods have been successfully established for forecasting Hermitian DOS in the thermodynamic limit, which reveals the criticality of NABSs44,45,46. Recently, researchers have begun investigating the interplay between non-Hermiticity and hyperbolic geometry48,49,50,51,52. On the one hand, non-Hermitian phenomena known in Euclidean space have been investigated in hyperbolic settings, such as the exceptional properties of U(1) band structures49 and the hybrid higher-order skin effect51. On the other hand, unique effects arising from the interplay of non-Hermiticity and hyperbolic geometry have been explored, for example, by using the hyperbolic plane to understand non-Hermitian physics in flat-space contexts50 or by employing geodesics to analyze the NHSE52. However, the general determination of the OBC spectra \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) with NABSs included remains an open and critical challenge, which is the focus of our work.

In this work, we present a systematic and efficient approach to determining \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\)—which encompasses both OBC spectral ranges and gaps—for non‐Hermitian hyperbolic lattices in the thermodynamic limit. Our method utilizes incremental supercells to incorporate more NABSs and further employs analytic continuation to obtain \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\). To illustrate, we first analyze a single-band model to contrast the PBC spectra and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\), thereby demonstrating the NHSE. We then delve into a celebrated non-Abelian semimetal model and reveal that NABSs exhibit distinct non-Hermitian phases compared with ABSs.

Results

Determination of uniform spectra

To detail the conundrum of acquiring \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) in hyperbolic lattices, we commence from lattice tessellation to translation groups. Infinite lattices are typically tessellated into unit cells related by translational operations. Beyond using the primitive cell, one can adopt specific groupings of \(n\) (\( > 1\)) primitive cells, dubbed n-supercell (\(n=1\) being the primitive cell), to tile the lattice45. Figure 1a, b depict the primitive cell, the 2-supercell, and translational operators \({\gamma }_{i}\) of a Euclidean {4,4} and hyperbolic {8,8} lattice (see Sec. I in Supplementary Information). PBCs compactify these cells into closed manifolds (bottom in Fig. 1a, b), referred to as PBC clusters43. For a Euclidean lattice, any unit cell, regardless of n, is compactified to a torus (Fig. 1a). However, for a hyperbolic lattice, the genus \({g}^{(n)}\) (\(=n({g}^{(1)}-1)+1\)) of an n-supercell increases linearly with n, meaning different supercells are compactified onto manifolds with different genera. For instance, the primitive cell (2-supercell) in Fig. 1b is compactified onto surfaces with \({g}^{(1)}=2\) (\({g}^{(2)}=3\)). This distinction reflects inherent differences in translation groups of hyperbolic lattices and Euclidean lattices.

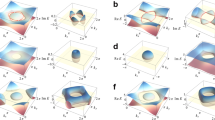

Symmetrized construction of n-supercells in a the Euclidean {4,4} and b hyperbolic {8,8} lattice. Translational operators \(\left\{{\gamma }_{i}\right\}\) for each lattice are labeled herein. The corresponding translation groups are \({\Gamma }_{\left\{{\mathrm{4,4}}\right\}}^{(1)}=\left\langle {\gamma }_{1},{\gamma }_{2}| {\gamma }_{1}{\gamma }_{2}^{-1}{\gamma }_{1}^{-1}{\gamma }_{2}=1\right\rangle \) and \({\Gamma }_{\left\{{\mathrm{8,8}}\right\}}^{(1)}=\left\langle {\gamma }_{1},{\gamma }_{2},{\gamma }_{3},{\gamma }_{4}| {\gamma }_{1}{\gamma }_{2}^{-1}{\gamma }_{3}{\gamma }_{4}^{-1}{\gamma }_{1}^{-1}{\gamma }_{2}{\gamma }_{3}^{-1}{\gamma }_{4}=1\right\rangle \). The region enclosed by the magenta (blue) line at the top is the primitive cell (2-supercell), with its corresponding compactification sketched at the bottom. c Schematic illustration of our approach to calculate \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\). \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{1}^{(n)}\), \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{2}^{(n)}\), and \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{3}^{(n)}\) are depicted to represent all \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{(n)}\), with their intersection (red hatched area) corresponding to \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\). \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(n)}\) (gray areas) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) (red areas) for different supercells in d the {4,4} and e, f {8,8} lattice. Here, \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{(n)}\) denotes a particular rescaled spectrum of the n-supercell; \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(n)}\) represent the uniform spectra and the PBC spectrum of the n-supercell, respectively. The dark and light colors stand for the \(n=1\) and \(n=2\) cases, respectively. The orange areas in e, f display typical patterns of \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{(n)}\) for \(|{\beta }_{j}|=\{{\mathrm{0.7,0.7,0.7,0.7}}\}\) and \(|{\beta }_{j}|=\left\{{\mathrm{1.1,1.2,0.9,1.2,1.1,0.8}}\right\}\), respectively, where \({\beta }_{j}={e}^{i{k}_{j}+{\mu }_{j}}\). The Euclidean lattice model used is \(H\left({\beta }_{1},{\beta }_{2}\right)={\beta }_{1}+\frac{1}{2}{\beta }_{1}^{-1}+{\beta }_{2}+\frac{1}{2}{\beta }_{2}^{-1}\), while the hyperbolic lattice model of the primitive cell is \({H}^{(1)}\left({\beta }_{1},{\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},{\beta }_{4}\right)={2\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{1}^{-1}+{\beta }_{2}+{\beta }_{2}^{-1}+{\beta }_{3}+{\beta }_{3}^{-1}+{\beta }_{4}+{\beta }_{4}^{-1}\).

Translational operations associated with primitive cells build the maximal translation group \({\Gamma }^{(1)}=\Gamma\), while those on n-supercells form subgroups Γ(n) ⊲ Γ(1). The commutativity of \({\gamma }_{i}\in {\Gamma }^{(1)}\) in Euclidean lattices ensures Abelian translation groups with only one-dimensional irreducible representations, forming the basis of the conventional Bloch theorem. The n-supercells merely reduce the Brillouin zone size, resulting in band folding without new physics, making primitive cell calculations sufficient in the thermodynamic limit. In contrast, \({\gamma }_{i}\in {\Gamma }^{(1)}\) in hyperbolic lattices generally do not commute, and translation groups allow higher-dimensional irreducible representations43. These characterize states that cannot simply be modeled by a Bloch phase under translation, even with analytic continuations, thus defining NABSs. Applying PBCs to the primitive cell only captures ABSs within the U(1)-HBT, which is insufficient for forecasting the OBC spectra. Employing n-supercells as PBC clusters enables the identification of NABSs because investigating \({\Gamma }^{(n)}\) can voluntarily invoke higher-dimensional irreducible representations of \(\Gamma\)45. Hence, constructing a sequence of such PBC clusters to approach the thermodynamic limit is then feasible and has shown a rapid convergence in the DOS for Hermitian systems as n increases, consistent with real-space calculations44.

We now turn to the non-Hermitian scenario, where calculating \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) is central. Since the essence of n-supercells lies in the necessity of examining \({\Gamma }^{(n)}\) as n increases, together with the fact that \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) is based on the analytic continuation of Bloch wavenumbers, we next generalize the supercell method45 to accommodate non-Hermitian hyperbolic lattices. Wrapping the n-supercell into a PBC cluster requires implementing \({d}_{\{p,q\}}^{(n)}\) (\(=2{g}^{(n)}\)) numbers of \({e}^{i{k}_{j}}\) (\(j=1,\ldots ,{d}_{\{p,q\}}^{(n)}\)) to specific pairs of boundaries (see “Methods” for details), and we perform \({k}_{j}\to {k}_{j}-i{\mu }_{j}\) for each \({k}_{j}\), leading to the n-supercell Hamiltonian \({H}^{(n)}\left({\beta }_{j}={e}^{i{k}_{j}+{\mu }_{j}}\right)\). The eigenvalue winding numbers are defined for each \({k}_{\alpha }\) (\(\alpha =1,\ldots ,\,{d}_{\{p,q\}}^{(n)}\)) and now depend on n as follows16,17:

where \(E{\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{C}}\) is the base energy, \({f}^{(n)}\left(E,{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(n)}\right)=\det \left[{H}^{\left(n\right)}\left({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(n)}\right)-E\right]\) is the characteristic polynomial for the n-supercell, and \({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(n)}=\left\{{\beta }_{j}{;j}=1,\ldots ,\,{d}_{\{p,q\}}^{(n)}\right\}\). Since nonzero eigenvalue winding numbers forecast the occurrence of point gaps, we introduce the rescaled spectrum of n-supercells as17,26:

where each \({\ell}\) corresponds to a specific configuration of \(\left|{\beta }_{j}\right|\) values. Physically, \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{(n)}\left(\left|{\beta }_{j}\right|\right)\) identifies the spectral range with nonzero total eigenvalue winding numbers for a given set of \(\left|{\beta }_{j}\right|\) values26. The energy residing in \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) requires that the total eigenvalue winding numbers do not vanish for all \(\left|{\beta }_{j}\right|\), or equivalently, point gaps are nontrivially open17. Hence, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) is obtained by taking the intersection of all \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{(n)}\left(\left|{\beta }_{j}\right|\right)\) as

The results of \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) are precisely the same as \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{A}}}}^{(n)}\) calculated by amoeba theory as demonstrated in ref. 26, but we choose to utilize the uniform spectra approach because it is not straightforward to visualize the amoeba pattern here26. Figure 1c sketches this intersection process, where three \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{\left(n\right)}\) are shown as representatives of all \({{{\rm{Sp}}}}_{{\ell}}^{\left(n\right)}\). The red hatched area, representing the intersection, corresponds to \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{\left(n\right)}\). Incrementing n then determine \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) in non-Hermitian hyperbolic lattices.

To demonstrate this approach, we first deploy the single-band nonreciprocal models in the Euclidean {4,4} and hyperbolic {8,8} lattice. Figure 1d–f display the spectral ranges obtained from various n-supercells for the Euclidean lattice and hyperbolic lattice, respectively. Here, the hyperbolic lattice model for the primitive cell is \({H}^{(1)}\left({\beta }_{1},{\beta }_{2},{\beta }_{3},{\beta }_{4}\right)={2\beta }_{1}+{\beta }_{1}^{-1}+{\beta }_{2}+{\beta }_{2}^{-1}+{\beta }_{3}+{\beta }_{3}^{-1}+{\beta }_{4}+{\beta }_{4}^{-1}\). The n-supercell PBC spectra \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(n)}\) (gray areas) are calculated from the PBC cluster approach45, while \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) (red areas) are obtained by our method. A common feature across Fig. 1d–f is \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\subset {\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(n)}\) for all n, a hallmark of NHSEs. As expected, the values of n do not alter \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(n)}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) in the Euclidean lattices (Fig. 1d), which aligns with the Abelian nature of \({\Gamma }^{(1)}\). Comparing Fig. 1e, f shows that \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(n)}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n)}\) do not vary significantly with n, which is a consequence of the symmetry and nonreciprocity used in this concrete model (see Sec. II in Supplementary Information). We will later demonstrate the non-Abelian characteristic, where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}/{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\ne {\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}/{{\rm{U}}}}^{(n\ne 1)}\), highlighting the non-Abelian nature of \({\Gamma }^{(1)}\). This result shows that the fundamental distinctions between non-Hermitian and Hermitian systems in Euclidean space also persist in hyperbolic space, underscoring that our method provides a systematic framework for investigating the spectral topology of hyperbolic lattices, particularly point-gap topology and phase transitions, which we discuss next.

Higher-dimensional skin effects

We first scrutinize the NHSE, a renowned manifestation of point-gap topology, to validate our recipe. Here, we employ a specific graph with the primitive cell unchanged and meticulous connections, which can be compactified into a torus with genus \({g}^{(1)}\equiv g\)34. This graph supports only ABSs, is regarded as the counterpart of a \(2g\)-dimensional Euclidean lattice, and therefore the U(1)-HBT holds exactly for it. Consequently, the primitive cell suffices to reflect the essential properties, and we term them HDELs34.

We detail the process for constructing an HDEL. For a \(2g\)-dimensional Euclidean lattice, any site can be exclusively determined by the \({N}_{c}\) site(s) in the primitive cell and the Bravais lattice vectors \({{\boldsymbol{h}}}=({h}_{1},\ldots ,{h}_{2g})\in {{\mathbb{N}}}^{2g}\). The Abelian translational group assures that, for example, the position vectors \({{\boldsymbol{h}}}{{\boldsymbol{+}}}\hat{1}{{\boldsymbol{+}}}\hat{2}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{h}}}{{\boldsymbol{+}}}\hat{2}{{\boldsymbol{+}}}\hat{1}\) point to the same site, and both \({{\boldsymbol{h}}}{{\boldsymbol{+}}}\hat{1}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{h}}}{{\boldsymbol{+}}}\hat{2}\) sites are its nearest neighbors [\(\hat{1}\), \(\hat{2}\), and similarly \(\hat{j}\) \((j=1,\ldots ,2g)\) are the basis vectors for each direction]. However, this property does not hold for a hyperbolic lattice due to its non-Abelian translational group, but we can still construct an HDEL by leveraging the \(2g\)-dimensional Euclidean lattice. We first construct an N-site (\(N={N}_{c}{L}_{1}{L}_{2}\cdots {L}_{j}\)) PBC cluster in the \(2g\)-dimensional Euclidean lattice, where \({L}_{j}\) is the number of unit cells in each direction. The PBCs ensure that the site at \({h}_{j}+{L}_{j}\) is equivalent to the site at the \({h}_{j}\) cell (\({h}_{j}\in \left\{1,\cdots ,{L}_{j}\right\}\)). All sites, uniquely labeled, along with their nearest-neighbor connections, can be embedded in an \(N\times N\) adjacency matrix. Next, we deploy \(N\) sites on the hyperbolic lattice and connect them according to the above adjacency matrix, which is precisely the HDEL with \(N\) sites.

As a result, the eigenvalues of an HDEL are identical to those of the Bloch Hamiltonian \({H}^{(1)}({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\) with known quantized momenta \({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}_{\eta }=\left({k}_{1},\ldots ,{k}_{2g}\right)\) (\(\eta =1,\ldots ,N\)), given by

For the single-band nonreciprocal model used in Fig. 1e, f, \({H}^{\left(1\right)}\left({{\boldsymbol{k}}}\right)=2[\cos \left({k}_{2}\right)+\cos \left({k}_{3}\right)+\cos \left({k}_{4}\right)]+{2e}^{i{k}_{1}}+{e}^{-i{k}_{1}}\). We choose \({L}_{j}=6\) for each direction. As shown in Fig. 2a, the blue circles represent the spectrum of HDEL with \(N={6}^{4}=1296\) sites calculated by diagonalization of the \(1296\times 1296\) adjacency matrix, while the magenta asterisks are obtained by substituting \(1296\) quantized 4-dimensional momenta into \({H}^{\left(1\right)}\left({{\boldsymbol{k}}}\right)\), consistent perfectly with each other. The HDEL is undoubtedly distinct from the supercell, which automatically includes higher-dimensional irreducible representations. By comparison, the HDEL spectrum always resides within \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(1)}\), which confirms \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(1)}\) suffices for modeling HDELs and suggests that the HDEL serves as an alternative platform for exploring non-Hermitian phenomena in high-dimensional Euclidean systems. The white and green lines in Fig. 2a represent the PBC spectra of the primitive cell by varying \({k}_{1}\) while fixing other \({k}_{j}\). Nontrivial point gaps are evident, and NHSE is forecasted.

Spectra (blue circles) of a a higher-dimensional Euclidean lattice (HDEL) and b the corresponding OBC configuration. Regions \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(1)}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) are plotted in gray and red, respectively. Magenta asterisks in (a) are obtained by substituting quantized momenta into \({H}^{(1)}({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\). The values of \(\left\{{k}_{2},{k}_{3},{k}_{4}\right\}\) for the white and green lines in (a) are \(\left\{\pi /7,\pi /7,\pi /7\right\}\) and \(\left\{\pi /{\mathrm{4,2}}\pi /3,\pi /2\right\}\), respectively. All results in a are obtained under PBC settings. The histograms in b display the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the right and left eigenvectors for states within the range highlighted by the white arrow. Distribution of Green’s functions (blue circles in top panels) and spectral sums of eigenstates (red spheres in bottom panels) along c \({\gamma }_{1}\) and d \({\gamma }_{2}\) directions, with marker sizes proportional to their magnitudes. The numbers denote the source and probe positions. Excitation energy is \(E=2.5\). The HDEL contains 1296 sites with explicit geometry defined in the second paragraph of the “Higher-dimensional skin effects” subsection of the main text.

To construct the HDEL under OBC, we remove the PBC connections in the original adjacency matrix, and the blue circles in Fig. 2b depict the calculated OBC spectra. For comparison, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) from Fig. 1e, defining the spectral range where Abelian states can exist, is also shown (red line in Fig. 2b). The OBC spectra lie within \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) and are noticeably distinct from the PBC spectra, suggesting NHSE. A hallmark of the nonreciprocal NHSE is the skewness of right and left eigenvectors5; namely, they always localize on opposite sides of the lattice. We use the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence, a non-negative measure quantifying the difference between two distributions, equaling 0 when identical and increasing with disparity53. The inset of Fig. 2b presents the percentage distribution of KL divergence between the right and left eigenvectors for states within the range highlighted by the white arrow, indicating the presence of NHSE.

Besides features in the eigenstates, NHSEs also manifest as directional amplifications during transport54,55. To showcase the NHSE, we choose to employ the Green’s function \(G\left(E\right)={(E-{H}_{{{\rm{OBC}}}})}^{-1}\), where \({H}_{{{\rm{OBC}}}}\) is the OBC Hamiltonian, and \(E\) is an arbitrary energy. We use \(s\) and \(p\) to denote the positions of the source and the probe, respectively. The upper panel of Fig. 2c illustrates the distribution of \(|\left\langle p\left|G\left(E=2.5\right)\right|s\right\rangle |\) as functions of s and p, both placed along the \({\gamma }_{1}\) direction, with marker sizes linearly proportional to their magnitudes. A clear tendency toward the negative \({\gamma }_{1}\) direction is seen, aligning with the spectral sum of eigenstates within the same range, as shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2c. This tendency, together with the eigenstates, confirms the occurrence of NHSE, consistent with the nonreciprocal coupling direction (see Sec. II in Supplementary Information). For comparison, Fig. 2d exhibits the distribution of \(|\left\langle p\left|G\left(E=2.5\right)\right|s\right\rangle |\) and the spectral sum of eigenstates along the \({\gamma }_{2}\) direction. No directional tendency is seen, corroborating the absence of NHSE in the eigenstates. The contrast between the \({\gamma }_{1}\) and \({\gamma }_{2}\) directions attests to the NHSE and the point-gap topology, verifying the implication of uniform spectra obtained by our method in hyperbolic lattices.

Non-Abelian semimetals

Line gaps, though also present in Hermitian systems, are as crucial as point gaps for understanding eigenstate behaviors in non-Hermitian systems, as their spectral range closely relates to topological phase transitions in the eigenstates. Recently, it has been revealed in Hermitian hyperbolic lattices that the emergence of NABSs can be even dominant over ABSs during such transitions47. To illustrate this, we employ the celebrated non-Abelian semimetal model on the {8,8} lattice, defined as (see Sec. III in Supplementary Information):

where the spinor \({\psi }_{r}\) has four components at each site \(r\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}^{4}\), \(j\) (\(=1,\ldots ,4\)) corresponds to four translational directions,

with \({\sigma }_{\upsilon }\) being the Pauli matrices, and \(m\) denotes the onsite potential. When \(m{\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{R}}\), this model can be treated as the hyperbolic counterpart of the four-dimensional quantum Hall insulator in Euclidean lattices, but the presence of NABSs spoils the line gaps with nonzero second Chern numbers (\({C}_{2}\ne 0\)) from ABSs and makes it become semimetal. Concisely, at \({m}_{r}=4\), the primitive cell (2-supercell) displays a topological phase transition from \({C}_{2}\ne 0\) (semimetal) to a trivial insulator47.

with \({\sigma }_{\upsilon }\) being the Pauli matrices, and \(m\) denotes the onsite potential. When \(m{\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{R}}\), this model can be treated as the hyperbolic counterpart of the four-dimensional quantum Hall insulator in Euclidean lattices, but the presence of NABSs spoils the line gaps with nonzero second Chern numbers (\({C}_{2}\ne 0\)) from ABSs and makes it become semimetal. Concisely, at \({m}_{r}=4\), the primitive cell (2-supercell) displays a topological phase transition from \({C}_{2}\ne 0\) (semimetal) to a trivial insulator47.

We now delve into phase diagrams when \(m{\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{C}}\) (\(={m}_{r}+{{im}}_{i}\)), indicating that the non-Hermiticity is introduced due to the onsite gain and loss. To this end, we need to determine \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) with NABSs included to show how \({m}_{i}\) alters the phase transitions. Since the Bloch Hamiltonians for the primitive cell and the 2-supercell are expressed as:

and

respectively, in which  , \({a}_{1}=1\), \({a}_{2}={\beta }_{2}^{-1}\), \({a}_{3}={\beta }_{2}^{-1}{\beta }_{4}\), \({a}_{4}={\beta }_{2}^{-1}{\beta }_{4}{\beta }_{6}^{-1}\), \({b}_{1}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}{\beta }_{2}^{-1}{\beta }_{5}^{-1}{\beta }_{6}^{-1}\otimes\), \({b}_{2}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}{\beta }_{3}{\beta }_{5}^{-1}\), \({b}_{3}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}{\beta }_{3}\), and \({b}_{4}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}\), we are capable to calculate \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\). By random sampling \({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(1,2)}\) (see “Methods” for details) and diagonalizing \({H}^{\left(1,2\right)}\) for each pair of \(({m}_{r},\,{m}_{i})\), we record the gap size \(\Delta\), defined by the spectral distance between the smallest absolute eigenenergy in the upper branch and that in the lower branch, to identify gapped and gapless states. For illustration, we plot \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) for \(m=3.7+0.4i\) (Fig. 3a) and \(m=3.9+0.6i\) (Fig. 3b), with \(\Delta\) in Fig. 3a indicated by a black arrow. Figure 3c depicts \(\Delta\) for the primitive cell. We also plot \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\) for the same values of \(m\) in Fig. 3d, e, and Fig. 3f shows \(\Delta\) for the 2-supercell. From the distributions of \(\Delta\), it is unambiguous to see a topological phase transition from \({C}_{2}\ne 0\) (semimetal) to a trivial insulator through the primitive cell (2-supercell) calculation. Although for all values of \(m\), the existing gaps are line gaps, the result of the primitive cell in Fig. 3a exhibits only a real-line gap, whereas in Fig. 3b, e, both the primitive cell and the 2-supercell show a clear imaginary-line gap16. As illustrated, a real-line gap—where no eigenvalues cross a chosen vertical line in the complex-energy plane (Fig. 3a)—and an imaginary-line gap—where no eigenvalues cross a chosen horizontal line (Fig. 3b, e)—are distinct gap types in non-Hermitian physics. The fact that an imaginary-line gap can lead to distinct topological boundary-state behaviors compared to a real-line gap56,57 indicates that the gap transitions in Fig. 3 differ from Hermitian ones and highlights the role of NABSs in shaping the nature of spectral gaps.

, \({a}_{1}=1\), \({a}_{2}={\beta }_{2}^{-1}\), \({a}_{3}={\beta }_{2}^{-1}{\beta }_{4}\), \({a}_{4}={\beta }_{2}^{-1}{\beta }_{4}{\beta }_{6}^{-1}\), \({b}_{1}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}{\beta }_{2}^{-1}{\beta }_{5}^{-1}{\beta }_{6}^{-1}\otimes\), \({b}_{2}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}{\beta }_{3}{\beta }_{5}^{-1}\), \({b}_{3}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}{\beta }_{3}\), and \({b}_{4}={\beta }_{1}^{-1}\), we are capable to calculate \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\). By random sampling \({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(1,2)}\) (see “Methods” for details) and diagonalizing \({H}^{\left(1,2\right)}\) for each pair of \(({m}_{r},\,{m}_{i})\), we record the gap size \(\Delta\), defined by the spectral distance between the smallest absolute eigenenergy in the upper branch and that in the lower branch, to identify gapped and gapless states. For illustration, we plot \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) for \(m=3.7+0.4i\) (Fig. 3a) and \(m=3.9+0.6i\) (Fig. 3b), with \(\Delta\) in Fig. 3a indicated by a black arrow. Figure 3c depicts \(\Delta\) for the primitive cell. We also plot \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\) for the same values of \(m\) in Fig. 3d, e, and Fig. 3f shows \(\Delta\) for the 2-supercell. From the distributions of \(\Delta\), it is unambiguous to see a topological phase transition from \({C}_{2}\ne 0\) (semimetal) to a trivial insulator through the primitive cell (2-supercell) calculation. Although for all values of \(m\), the existing gaps are line gaps, the result of the primitive cell in Fig. 3a exhibits only a real-line gap, whereas in Fig. 3b, e, both the primitive cell and the 2-supercell show a clear imaginary-line gap16. As illustrated, a real-line gap—where no eigenvalues cross a chosen vertical line in the complex-energy plane (Fig. 3a)—and an imaginary-line gap—where no eigenvalues cross a chosen horizontal line (Fig. 3b, e)—are distinct gap types in non-Hermitian physics. The fact that an imaginary-line gap can lead to distinct topological boundary-state behaviors compared to a real-line gap56,57 indicates that the gap transitions in Fig. 3 differ from Hermitian ones and highlights the role of NABSs in shaping the nature of spectral gaps.

a, b \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) and d, e \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\) for a, d \(m=3.7+0.4i\) and b, e \(m=3.9+0.6i\). Olive vertical line in (a) and brown horizontal lines in (b, e) indicate the real-line and imaginary-line gaps, respectively. c, f Gap size \(\Delta\) calculated for c the primitive cell and f the 2-supercell, which is obtained with a resolution \(\Delta {m}_{r}=0.025\) and \(\Delta {m}_{i}=0.01\). In c, f black asterisks emphasize the values of \(m\) in (a, b, d, e), and black dashed lines mark the positions of the phase transition points.

We then repeat the sampling and diagonalization process several times, recording \(\Delta\), which turns out to be quite similar. Therefore, we successfully identify the phase transition points, as plotted by the blue and red squares in Fig. 4a. The left and right panels depict the different topological phases for the primitive cell and the 2-supercell, respectively. We can see that both transition points in \({m}_{r}\) decrease when \({m}_{i}\) climbs up, and thus, it can be expected that for a given \(m\), \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\) must show distinct behaviors compared with \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\), a remarkable feature of NABSs.

a Phase diagram of the primitive cell (left) and the 2-supercell (right) in the complex m plane. Light orange and pink regions highlight the \({C}_{2}\ne 0\) phase and semimetal phase, while light cyan regions denote the trivial insulator phase. Blue and red squares represent the calculated phase transition points for the primitive cell and the 2-supercell, respectively. Errors are obtained by standard deviations of phase transition points from all samples, with these small values being covered by the data points. b \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) (red) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\) (light red) when \(m=3+0.3i\). Filled circles show spectra from U(2) hyperbolic band theory [U(2)-HBT], and the dark solid line highlights their spectral boundary. c \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) (red) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(4)}\) (light red) when \(m=5+0.5i\). The inset shows the lower branch of the spectra with the blue and green markers depicting the OBC spectra for two configurations of 1601 and 1142 sites.

We first choose \(m=3+0.3i\) to investigate, which lies in the primitive cell gapped (2-supercell gapless) phase. The calculated \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(2)}\)) in Fig. 4b confirms that the line gap is open (closed) when non-Abelian states are absent (present). To further verify the origin of line gap closing, we call U(2)-HBT45,58 and show its spectra by gray dots in Fig. 4b (see “Methods” and Sec. III in Supplementary Information for details). Good agreement in the gap closing validates our method of \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\) and confirms that the spectral behaviors of non-Abelian states are from NABSs for reciprocal non-Hermitian systems (see Sec. III in Supplementary Information). We now turn to the trivial phase for both the primitive cell and the 2-supercell. Setting \(m=5+0.5i\), we clearly see a gap in \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) (Fig. 4c). We also depict \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(4)}\) in Fig. 4c, which showcases that the line gap remains intact in the thermodynamic limit. However, the non-emptiness of \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(4)}-{\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) hints at the appearance of non-Abelian states under OBCs. Thus, we compute the OBC spectra for two configurations, represented by the filled circles and stars in the inset of Fig. 4c. Both OBC spectra lying in \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(4)}\) validate our method of acquiring \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\), and degenerate states within \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(4)}-{\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1)}\) affirm the existence of non-Abelian states. The distinction between the primitive cell and the n-supercell highlights the critical role of non-Abelian states in forming line gaps and determining the OBC spectral range, further emphasizing the criticality of accurately calculating \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}\).

Conclusions

In summary, we implement incremental supercells to encompass non-Abelian states and perform analytic continuation to determine the OBC spectra in the thermodynamic limit, including spectral ranges and gaps, in hyperbolic lattices based on the connotation of point gaps. Applying it to a single-band nonreciprocal model, we demonstrate higher-dimensional skin effects in an HDEL, showcasing the point-gap topology. Furthermore, through a non-Abelian semimetal model, our method successfully forecasts topological phase transition points in both Abelian and non-Abelian states. Therefore, our approach offers a feasible way to investigate spectral topology and non-Hermitian phase transitions associated with gaps in hyperbolic lattices. While our focus is on acquiring OBC spectra in the thermodynamic limit, the underlying principles of our method, based on subgroups and induced representations, can be generalized to other non-periodic lattices with well-defined generation groups, such as Cayley tree59, Bethe lattice60, and fractals61. Given recent advances in non-Hermitian topological invariants of higher-dimensional systems, whether using non-Bloch24 or real-space approaches62, our method is a valuable tool for investigating topological phase transitions and quantum phenomena in non-Hermitian hyperbolic lattices.

Methods

Periodic boundary conditions for the supercells

One can construct a sequence of increasingly large PBC clusters, which are finite-sized hyperbolic lattices with PBCs, to estimate the spectra in the thermodynamic limit. A PBC cluster with n primitive cells is defined by a specific normal subgroup ΓPBC ⊲ Γ corresponding to a set of translations under which the wave function is invariant and thus can be computed by the quotient group \(\Gamma /{\Gamma }_{{{\rm{PBC}}}}\)43.

The supercell method is an effective and systematic approach for constructing a set of PBC clusters that rapidly converge to the thermodynamic limit45. The elegance of this method lies in its ability to obtain NABSs using only U(1)-HBT without requiring U(d)-HBT, making it both convenient and efficient. Specifically, by applying U(1)-HBT to sequences of PBC clusters with an increasing number n of primitive cells in a symmetric fashion, dubbed supercells, more and more NABSs are generated, and convergence is attained for \(n\to \infty\). The sequence of translation groups of supercells should respect the normal subgroup relations: Γ(1)⊳ Γ(2)⊳⋯⊳Γ(m)⊳\(\cdots\), which can be obtained from the factor groups given in ref. 63 using the HyperCells package64,65. Note that the superscript \(\left(m\right)\) indicates the position of the subgroup in the sequence, not the supercell index n. The supercell method does not explicitly enforce the assumption \({\cap }_{m\ge 1}{\Gamma }^{(m)}=\{1\}\), but it is required in ref. 46, where an algorithmic procedure is developed to impose PBCs on finite hyperbolic crystals of increasing size, thereby capturing spectral properties in the thermodynamic limit. However, ref. 45 shows that the supercell sequences used, though non-unique, converge to the same limit, as also confirmed numerically by the continued-fraction method (see Sections III and IV in the Supplementary Information for details).

Since the genus \({g}^{\left(n\right)}\) [\(=n\left({g}^{\left(1\right)}-1\right)+1\)] of an n-supercell increases linearly with n, one needs \(2{g}^{\left(n\right)}\) momentum components to construct an U(1) Bloch Hamiltonian \({H}^{\left(n\right)}\) for an n-supercell. As an example, for the {8, 8} lattice, \({g}^{\left(1\right)}\equiv g=2\) and the U(1) Brillouin zones for the primitive cell and the 2-supercell are 4-dimensional and 6-dimensional, respectively. Based on the subgroup relation, one can write down the n-supercell translation generators in terms of \(\{{\gamma }_{1},{\gamma }_{2},\,{\gamma }_{3},\,{\gamma }_{4}\}\). For the 2-supercell, the six generators are: \(\widetilde{{\gamma }_{1}}={\gamma }_{4}^{-1}{\gamma }_{1}^{-1}\), \(\widetilde{{\gamma }_{2}}={\gamma }_{1}^{-1}{\gamma }_{2}\), \(\widetilde{{\gamma }_{3}}={\gamma }_{3}{\gamma }_{4}^{-1}\), \(\widetilde{{\gamma }_{4}}={{\gamma }_{2}\gamma }_{3}^{-1}\), \(\widetilde{{\gamma }_{5}}={{\gamma }_{3}\gamma }_{2}^{-1}\), and \(\widetilde{{\gamma }_{6}}={\gamma }_{3}^{-1}{\gamma }_{4}\), which indicates the following immersion from the 4-dimensional Brillouin zone to the 6-dimensional Brillouin zone: \(({k}_{1},{k}_{2},{k}_{3},{k}_{4})\mapsto ({-k}_{4}-{k}_{1},{-k}_{1}+ {k}_{2},{k}_{3}-{k}_{4},{k}_{2}-{k}_{3},\,{k}_{3}-{k}_{2},{k}_{4}-{k}_{3})\). Note that the immersion is not the one-to-one mapping of \({k}_{j}\), and thus, the numbers of wavenumbers increase with n. Other immersion of the original 4-dimensional Brillouin zone into a higher-dimensional Brillouin zone for an n-supercell (n = 4, 8, 16, 32) can be found using a similar procedure45,65.

Determination of gap size \(\Delta\) for the primitive cell and the 2-supercell

When the characteristic equation of a non‐Hermitian Hamiltonian \(H\) satisfies:

with \({\beta }_{j}={e}^{i{k}_{j}+{\mu }_{j}}\) for any energy \(E\), one finds that \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}\) due to the resulting \({C}_{2}\)-symmetry of the convex Ronkin function24,66, i.e., \({R}_{f}\left({{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}\right)={R}_{f}\left(-{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}\right)\). Concretely, for the Bloch Hamiltonians \({H}^{\left(1\right)}\left({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(1)}\right)\) of the primitive cell [Eq. (6)] and \({H}^{\left(2\right)}\left({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(2)}\right)\) of the 2-supercell [Eq. (7)], their characteristic equations \(\det \left[{H}^{\left(n\right)}\left({{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{(n)}\right)-E\right]=\det \left[{H}^{\left(n\right)}\left({{{{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}}^{-1}}^{(n)}\right)-E\right]=0\) are always true for an arbitrary energy, ensuring \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{U}}}}^{(1/2)}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(1/2)}\). As a consequence, we alternatively compute \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{P}}}}^{(1/2)}\) instead of searching for the intersection of the rescaled spectra to identify the phase transitions, which greatly simplifies our calculations. By randomly sampling the Brillouin zone with \(5\times {10}^{5}\) (\(2.5\times {10}^{6}\)) k-points and diagonalizing \({H}^{\left(1\right)}\) [\({H}^{\left(2\right)}\)] for each pair of \(({m}_{r},\,{m}_{i})\), we record the gap size \(\Delta\) and plot Fig. 3c, f.

U(2) spectra by U(2)-HBT

When considering two-dimensional irreducible representations, the Bloch states should transform into representations \({D}_{\lambda }\left({\gamma }_{j}\right)={U}_{j}{e}^{i{k}_{j}}\), where \({U}_{j}\in {{\rm{SU}}}(2)\) (\(j={\mathrm{1,2,3,4}}\)) is a certain unitary \(2\times 2\) matrix and \(\lambda\) denotes an irreducible representation. The ensuing Hamiltonian can then be formally expressed by using  45. Hence, the key point is to find these special \({{\boldsymbol{U}}}={\{{U}_{j}\}}_{j=1}^{4}\). An SU(2) matrix can be expressed as:

45. Hence, the key point is to find these special \({{\boldsymbol{U}}}={\{{U}_{j}\}}_{j=1}^{4}\). An SU(2) matrix can be expressed as:

where \({e}_{j},\,{f}_{j}\,{\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{C}}\) and \({|{e}_{j}|}^{2}+{|{f}_{j}|}^{2}=1\). To ensure a valid representation of the Fuchsian group \(\Gamma\), the choice of the four matrices should satisfy the condition:

Here, we briefly introduce the procedure to find \({{\boldsymbol{U}}}\). First, we randomly select \({U}_{{\mathrm{1,2}}}\) from the circular unitary ensemble, ensuring a uniform distribution over the unitary \(2\times 2\) matrices. Then, we randomly choose the initial \({U}_{{\mathrm{3,4}}}\) using the same distribution, decompose them into \({e}_{{\mathrm{3,4}}}\) and \({f}_{{\mathrm{3,4}}}\) as Eq. (9), and minimize the Frobenius norm in Eq. (10). In cases where the algorithm converges to a local minimum that does not satisfy Eq. (10), the matrices are discarded. By repeating the above sampling process to obtain distinct \({{\boldsymbol{U}}}\), and then randomly sample \({\{{e}^{i{k}_{j}}\}}_{j=1}^{4}\), we can calculate the U(2) spectra. Details of our calculation process for the U(2) spectra in Fig. 4b are provided in Supplementary Information Sec. III, where the gapless feature confirms the semimetal property.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

El-Ganainy, R. et al. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 14, 11–19 (2018).

Yao, S. & Wang, Z. Edge states and topological invariants of Non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086803 (2018).

Ashida, Y., Gong, Z. & Ueda, M. Non-Hermitian physics. Adv. Phys. 69, 249–435 (2020).

Bergholtz, E. J., Budich, J. C. & Kunst, F. K. Exceptional topology of non-Hermitian systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 015005 (2021).

Ding, K., Fang, C. & Ma, G. Non-Hermitian topology and exceptional-point geometries. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 745–760 (2022).

Feng, L., El-Ganainy, R. & Ge, L. Non-Hermitian photonics based on parity–time symmetry. Nat. Photonics 11, 752–762 (2017).

Zhou, H. et al. Observation of bulk Fermi arc and polarization half charge from paired exceptional points. Science 359, 1009–1012 (2018).

Bandres, M. A. et al. Topological insulator laser: experiments. Science 359, eaar4005 (2018).

Tang, W. et al. Exceptional nexus with a hybrid topological invariant. Science 370, 1077–1080 (2020).

Xue, H. et al. Non-Hermitian Dirac cones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 236403 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Acoustic non-Hermitian skin effect from twisted winding topology. Nat. Commun. 12, 6297 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. A review on non-Hermitian skin effect. Adv. Phys. X 7, 2109431 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. Non-Hermitian topological phononic metamaterials. Adv. Mater. 2023, 2307998 (2023).

Zhao, E. et al. Two-dimensional non-Hermitian skin effect in an ultracold Fermi gas. Nature 637, 565–573 (2025).

Pan, L., Chen, X., Chen, Y. & Zhai, H. Non-Hermitian linear response theory. Nat. Phys. 16, 767–771 (2020).

Kawabata, K., Shiozaki, K., Ueda, M. & Sato, M. Symmetry and topology in Non-Hermitian physics. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041015 (2019).

Okuma, N., Kawabata, K., Shiozaki, K. & Sato, M. Topological origin of non-Hermitian skin effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 086801 (2020).

Ghatak, A., Brandenbourger, M., van Wezel, J. & Coulais, C. Observation of non-Hermitian topology and its bulk-edge correspondence in an active mechanical metamaterial. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29561–29568 (2020).

Helbig, T. et al. Generalized bulk–boundary correspondence in non-Hermitian topolectrical circuits. Nat. Phys. 16, 747–750 (2020).

Xiao, L. et al. Non-Hermitian bulk–boundary correspondence in quantum dynamics. Nat. Phys. 16, 761–766 (2020).

Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Fang, C. Universal non-Hermitian skin effect in two and higher dimensions. Nat. Commun. 13, 2496 (2022).

Yokomizo, K. & Murakami, S. Non-Bloch band theory of Non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 066404 (2019).

Yang, Z., Zhang, K., Fang, C. & Hu, J. Non-Hermitian bulk-boundary correspondence and auxiliary generalized Brillouin zone theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 226402 (2020).

Wang, H. Y., Song, F. & Wang, Z. Amoeba formulation of non-Bloch band theory in arbitrary dimensions. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021011 (2024).

Nakamura, D., Bessho, T. & Sato, M. Bulk-boundary correspondence in point-gap topological Phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 136401 (2024).

Hu, H. Topological origin of non-Hermitian skin effect in higher dimensions and uniform spectra. Sci. Bull. 70, 51–55 (2025).

Wang, W., Hu, M., Wang, X., Ma, G. & Ding, K. Experimental realization of geometry-dependent skin effect in a reciprocal two-dimensional lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 207201 (2023).

Shu, C., Zhang, K. & Sun, K. Ultra spectral sensitivity and non-local bi-impurity bound states from quasi-long-range non-Hermitian skin modes. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.13623 (2024).

Kollár, A. J., Fitzpatrick, M. & Houck, A. A. Hyperbolic lattices in circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 571, 45 (2019).

Lenggenhager, P. M. et al. Simulating hyperbolic space on a circuit board. Nat. Commun. 13, 4373 (2022).

Yu, S., Piao, X. & Park, N. Topological hyperbolic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 053901 (2020).

Zhang, W., Yuan, H., Sun, N., Sun, H. & Zhang, X. Observation of novel topological states in hyperbolic lattices. Nat. Commun. 13, 2937 (2022).

Liu, Z., Hua, C., Peng, T. & Zhou, B. Chern insulator in a hyperbolic lattice. Phys. Rev. B 105, 245301 (2022).

Chen, A. et al. Hyperbolic matter in electrical circuits with tunable complex phases. Nat. Commun. 14, 622 (2023).

Stegmaier, A., Upreti, L. K., Thomale, R. & Boettcher, I. Universality of Hofstadter butterflies on hyperbolic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 166402 (2022).

Bienias, P., Boettcher, I., Belyansky, R., Kollár, A. J. & Gorshkov, A. V. Circuit quantum electrodynamics in hyperbolic space: from photon bound states to frustrated spin models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 013601 (2022).

Chen, A., Maciejko, J. & Boettcher, I. Anderson localization transition in disordered hyperbolic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 066101 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Anderson transition and mobility edges on hyperbolic lattices with randomly connected boundaries. Commun. Phys. 7, 371 (2024).

Sun, C., Chen, A., Bzdušek, T. & Maciejko, J. Topological linear response of hyperbolic Chern insulators. SciPost Phys. 17, 124 (2024).

Boettcher, I. et al. Crystallography of hyperbolic lattices. Phys. Rev. B 105, 125118 (2022).

Maciejko, J. & Rayan, S. Hyperbolic band theory. Sci. Adv. 7, abe9170 (2021).

Cheng, N. et al. Band theory and boundary modes of high-dimensional representations of infinite hyperbolic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 088002 (2022).

Maciejko, J. & Rayan, S. Automorphic Bloch theorems for hyperbolic lattices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116869119 (2022).

Mosseri, R. & Vidal, J. Density of states of tight-binding models in the hyperbolic plane. Phys. Rev. B 108, 035154 (2023).

Lenggenhager, P. M., Maciejko, J. & Bzdušek, T. Non-abelian hyperbolic band theory from supercells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 226401 (2023).

Lux, F. R. & Prodan, E. Converging periodic boundary conditions and detection of topological gaps on regular hyperbolic tessellations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 176603 (2023).

Tummuru, T. et al. Hyperbolic non-abelian semimetal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 206601 (2024).

Zhang, R., Lv, C., Yan, Y. & Zhou, Q. Efimov-like states and quantum funneling effects on synthetic hyperbolic surfaces. Sci. Bull. 66, 1967–1972 (2021).

Chadha, N. & Narayan, A. Uncovering exceptional contours in non-Hermitian hyperbolic lattices. J. Phys. A 57, 115203 (2024).

Lv, C., Zhang, R., Zhai, Z. & Zhou, Q. Curving the space by non-Hermiticity. Nat. Commun. 13, 2184 (2022).

Sun, J., Li, C., Feng, S. & Guo, H. Hybrid higher-order skin-topological effect in hyperbolic lattices. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075122 (2023).

Shen, R., Chan, W. & Lee, C. H. Non-Hermitian skin effect along hyperbolic geodesics. Phys. Rev. B 111, 045420 (2025).

Csiszar, I. Geometry of probability distributions and minimization problems. Ann. Probab. 3, 146 (1975).

McDonald, A. & Clerk, A. A. Exponentially-enhanced quantum sensing with non-Hermitian lattice dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5382 (2020).

Xiao, L. et al. Observation of non-Hermitian edge burst in quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 070801 (2024).

Nakamura, D. et al. Non-Hermitian origin of detachable boundary states in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 096601 (2025).

Nakamura, D. & Kawabata, K. Non-Hermitian Hopf insulators. Phys. Rev. B 112, 075134 (2025).

Shankar, G. & Maciejko, J. Hyperbolic lattices and two-dimensional Yang-Mills theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 226401 (2024).

Hamanaka, S. et al. Multifractal statistics of non-Hermitian skin effect on the Cayley tree. Phys. Rev. B 111, 075162 (2025).

Sun, J., Li, C., Li, P. & Guo, H. Inner non-Hermitian skin effect on the Bethe lattice. Phys. Rev. B 111, 075120 (2025).

Manna, S. & Roy, B. Inner skin effects on non-Hermitian topological fractals. Commun. Phys. 6, 10 (2023).

Dixon, K. Y., Loring, T. A. & Cerjan, A. Classifying topology in photonic heterostructures with gapless environments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 213801 (2023).

Conder, M. Quotients of triangle groups acting on surfaces of genus 2 to 101, (2007), https://www.math.auckland.ac.nz/~conder/TriangleGroupQuotients101.txt (accessed 02 2015).

GAP, GAP–Groups, Algorithms, and Programming, Version 4.11.1, The GAP Group (2021).

Lenggenhager, P. M., Maciejko, J. & Bzdušek, T. HYPER-CELLS package for GAP. https://github.com/patrick-lenggenhager/HyperCells (2023).

Zheng, R. et al. Experimental probe of point gap topology from non-Hermitian Fermi-arcs. Commun. Phys. 7, 298 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. C. T. Chan and Mr. Nan Cheng for the helpful discussions. This work is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFA1404500, No. 2022YFA1404701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12174072, No. 2021hwyq05, No. 12347144), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M730705).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and K.D. conceived the research. M.H. carried out the research and performed the theoretical and numerical calculations. M.H. and K.D. co-wrote the paper. M.H., J.L., and K.D. contributed to the discussion of results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, M., Lin, J. & Ding, K. Generalization of non-Hermitian spectral topology to hyperbolic lattices. Commun Phys 8, 377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02285-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02285-w