Abstract

The anomalous Hall effect (AHE), conventionally associated with time-reversal symmetry breaking in ferromagnetic materials, has recently been observed in nonmagnetic topological materials, raising questions about its origin. We unravel the unconventional Hall response in the nonmagnetic Dirac material ZrTe5, known for its massive Dirac bands and unique electronic and transport properties. Using the Kubo-Streda formula within the Landau level framework, we explore the interplay of quantum effects induced by the magnetic field (B) and disorder across the semiclassical and quantum regimes. In the semiclassical regime, the Hall resistivity remains linear in the magnetic field, but the Hall coefficient will be renormalized by the quantum geometric effects and electron-hole coherence, especially at low carrier densities where the disorder scattering dominates. In quantum limit, the Hall conductivity exhibits an unsaturating 1/B scaling. As a result, the transverse conductivity dominates transport in the ultra-quantum limit, and the Hall resistivity crosses over from B to B−1 dependence as the system transitions from the semiclassical regime to the quantum limit. This work elucidates the mechanisms underlying the unconventional Hall effect in ZrTe5 and provides insights into the AHE in other nonmagnetic Dirac materials as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The anomalous Hall effect (AHE) is a key electrical transport phenomenon with significant implications for both fundamental physics and applications1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. First observed in ferromagnetic iron11, the microscopic mechanisms of AHE have been debated for nearly a century12,13,14,15. Typically, AHE requires time-reversal symmetry breaking via magnetism with Hall resistivity as ρxy = R0B + RAHM, where R0B represents the magnetic field (B) linear ordinary Hall effect and RAHM corresponds to the magnetization induced AHE.

ZrTe5 is a nonmagnetic topological material characterized by massive Dirac bands, situated at the boundary between strong and weak topological insulators16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. It exhibits a paramagnetic response at low magnetic fields and no signatures of magnetic interactions24,25. A variety of intriguing phenomena have been observed in this material, including log-periodic quantum oscillations26, 3D quantum Hall effects23,27,28, resistivity anomaly29,30,31,32,33,34,35, and negative magnetoresistance20,36. Recently, an unconventional Hall signal has been reported in ZrTe5: the Hall resistivity ρxy exhibits an unconventional behavior in the high-field regime37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. This behavior, reminiscent of the AHE, is frequently attributed to the Berry curvature of the electronic bands, potentially arising from Zeeman splitting or the formation of Weyl nodes41,42,49. However, most studies rely on a semiclassical approximation and often neglect the orbital effects of the magnetic field. This oversight is particularly significant in systems with a narrow band gap and low carrier density, where the influence of the orbital effect of the magnetic field and disorder scattering becomes pronounced. The origin of the unconventional Hall effect in paramagnetic topological materials like ZrTe5 remains under debate, necessitating a quantitative investigation to clarify underlying mechanisms.

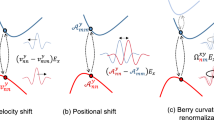

In this work, we investigate the mechanism of the unconventional Hall effect in paramagnetic Dirac materials by employing the Kubo-Streda formula within the framework of Landau levels, which deals with the quantum effect of magnetic fields and disorder on an equal footing. As shown in Fig. 1a, b, our calculations in the semiclassical regime reveal that quantum geometry effects—such as the Berry curvature (red/blue arrows) and quantum metric contributions (brown arrows)—introduce significant quantum corrections to the classical Lorentz-force-driven Hall conductivity (yellow arrows). These effects renormalize the Hall coefficient, particularly at low carrier densities where disorder scattering plays a significant role. Owing to their distinct symmetry properties under particle-hole transformation, the quantum geometry effects exhibit characteristically different behavior for electron- and hole-type carriers. In the quantum oscillation regime, the Fermi-surface contribution of the Zeeman-induced Berry curvature is suppressed by magnetic orbital effects and exhibits oscillations due to Landau level quantization, while the Fermi-sea contribution remains robust. In the quantum limit where the quasiclassical picture is entirely invalid, although the Zeeman splitting drives the formation of Weyl nodes, the Hall conductivity scales as ~en/B without saturation, where n is the carrier density. Consequently, the transverse conductivity dominates transport in the ultra-quantum limit, causing the Hall resistivity to be inversely proportional to B. The crossover from the semiclassical regime to the quantum limit results in unconventional Hall resistivity, and we identify the critical magnetic field at which the Hall resistivity transitions from positive to negative. This study presents a unified framework to elucidate the intricate interplay of quantum geometry, magnetic fields, and disorder in paramagnetic Dirac materials, while also shedding light on the mechanisms behind anomalous transport phenomena in numerous nonmagnetic Dirac systems.

The Hall effect in Dirac materials arises from distinct contributions for a electron-type and b hole-type carries, where a longitudinal current I under a perpendicular magnetic field B generates a transverse voltage V. Arrows indicate carrier motion directions: yellow for the classical Lorentz force and brown for quantum geometric effects (e.g., quantum metric and orbital magnetization). Under a fixed I, the Lorentz and quantum geometric terms produce transverse velocities that are invariant under carrier sign reversal, leading to an inverted Hall voltage. Red and blue arrows denote the Berry curvature contributions from Zeeman-split majority (s = +) and minority s = − states, respectively. The Berry curvature induces opposite anomalous velocities for s = ±, creating a transverse carrier imbalance and a finite voltage. Unlike the classical and geometric terms, this contribution reverses under carrier sign change, leaving the Hall voltage unchanged. c Evolution of electronic states with magnetic field. The system progresses through three regimes: (i) semiclassical (B < χ−1) (ii) quantum oscillations, and (iii) quantum limit (B > (μ2 − Δ2)/(2ℏv2e)). In the semiclassical regime, disorder broadening smears out the Landau levels. In the quantum limit, all carriers occupy only the lowest Landau level. Disorder broadening (red shading) and chemical potential μ (black dashed line) are shown for reference. d Quantum geometric effect-induced Hall effect. The black arrows depict the Bloch wavefunctions at adjacent k-points, with their directional difference representing the quantum metric (state distance). The red shading indicates the emergent curvature from interband coupling.

Results

Model and Zeeman effects

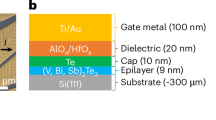

The anisotropic Hamiltonian for ZrTe5 in a finite perpendicular magnetic field B, can be written as19

with \(v=\sqrt{{v}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{v}_{{{\rm{y}}}}}\) and \(\Delta ({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})=\Delta +2C(1-\cos {k}_{{{\rm{z}}}}a)\). Π = k + eA represents the kinematic momentum, A denotes the vector potential components, and a is the lattice constant along z-direction. The Zeeman effect is encoded by m = gzμBB/2 with gz = 21.3 the g-factor42,50,51 and μB = 5.788 × 10−2 meV T−1 the Bohr magneton. The parameters in our model (listed in the caption of Fig. 2) are derived from first-principles calculations23, and are consistent with magneto-infrared spectroscopy measurements19. The magnetic field has two primary effects: the orbital effect (A), which drives the formation of Landau levels, and the Zeeman effect (m), which induces spin-dependent energy splitting. In the presence of a magnetic field, the eigenstates and eigenenergies can still be solved analytically, as demonstrated in Supplementary Note 1, where we also derive the corresponding Green’s function.

Band structure εsζ(k) at ∣k⊥∣ = 0 and the Zeeman-splitting-induced Hall effect for two magnetic field strengths: a B = 4 T and b B = 12 T, below and above the field BΔ = 2Δ/(gzμB) ≈ 8.11 T required for Weyl nodes formation. The electronic structure is color-coded (red to blue) to represent the logarithmic Berry curvature, sign(Ωz)ln∣Ωz∣. In b kc denotes the momentum-space separation between the Weyl nodes. The right panels of each subfigure show the Hall conductivity components: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\) (blue dashed), \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\) (red dashed), and their sum \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\)(black solid) versus energy E. Model parameters: vx = 9.11 × 105 m .s−1, vy = 1.97 × 104 m .s−1, tz = 20 meV, Δ = 5 meV, C = 100 meV, a = 1 nm, gz = 21.3, μB = 5.788 × 10−2 meV. T−1.

For m = 0 and A = 0, the Hamiltonian possesses time-reversal symmetry, resulting in a vanishing Hall conductivity. For m ≠ 0 and A = 0, the energy spectrum takes the form: \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{s}}}\zeta }({{\bf{k}}})=\zeta \sqrt{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{2}+{\hslash }^{2}{v}^{2}{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\perp }^{2}}\) where k⊥ = (kx, ky), \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})={\Delta }_{\parallel }({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})+sm\), and \({\Delta }_{\parallel }({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})=\sqrt{{\Delta }^{2}({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})+{t}_{{{\rm{z}}}}^{2}{\sin }^{2}{k}_{{{\rm{z}}}}a}\). Here, s = ± represents spin index, and ζ = ± denotes the conduction and valence bands, respectively. The energy spectra for ∣k⊥∣ = 0 are shown in Fig. 2. Zeeman splitting breaks the degeneracy of the energy levels. The Hall conductivity can be understood in terms of the nonzero Berry curvature of the occupied states, expressed as: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{V\hslash }{\sum }_{{{\bf{k}}},\zeta ,{{\rm{s}}}}f({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{s}}}\zeta }-\mu ){\Omega }_{{{\rm{z}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}\zeta }\), where the Berry curvature is given by \({\Omega }_{{{\rm{z}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}\zeta }=-\frac{s{\hslash }^{2}{v}^{2}{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}}{2{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{s}}}\zeta }^{3}}\) and f is the Fermi-Dirac distribution. The momentum-space distribution of Berry curvature is visualized through color mapping of Ωz on the electronic band structure. The superscript S indicates that this contribution arises from quantum geometry effects due to spin (S)-splitting induced by the magnetic field. When ∣m∣ increases beyond the band gap ∣Δ∣, a band crossing occurs, resulting in the creation of a pair of Weyl nodes. Particularly when μ = 0, the Hall conductivity is given by \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}{k}_{{{\rm{c}}}}}{2\pi h}\), with kc representing the distance between the two Weyl nodes4. For higher Zeeman fields ∣m∣ > ∣Δ + 4C∣, two Weyl points annihilate at the Brillouin zone boundary, causing the system to become insulating again. In this situation, the Hall conductivity becomes a constant at \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{ha}\) with a as the lattice constant in z-direction52. The Hall conductivity can also be calculated by using Kubo–Streda formula53,54, which separates Hall conductivity into two distinct contributions, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}+{\sigma }_{xy}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\) where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\) describes the response at the Fermi surface, and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\) represents a nondissipative contribution from states below the Fermi energy55,56,57. At zero temperature, these two components of the Hall conductivity can be obtained as

and

where \({{\rm{sgn}}}\) denotes the sign function, Θ is the Heaviside step function, and μ is the chemical potential. The Hall conductivity can be interpreted as a summation over each kz slice of a two-dimensional system. We plot the chemical potential dependence of \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\), \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\), and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) in Fig. 2. Figure 2a demonstrates that before Weyl point formation, all three components vanish identically within the band gap. After the Weyl points emerge (Fig. 2b), \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) generally receives contributions from both Fermi surface and Fermi sea terms. At charge neutrality, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) is solely determined by the Fermi sea contribution. For small magnetic field, both \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\) exhibit a linear dependence on B through the Zeeman term m. To first order in the magnetic field expansion, the total Hall conductivity can be obtained as \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{2\pi h}\frac{{k}_{0}}{| \mu | }{g}_{{{\rm{z}}}}{\mu }_{B}B\), where k0 is the Fermi wavevector along the z-direction in the absence of the Zeeman field, determined by Δ∥(k0) = ∣μ∣.

Orbital magnetic effects across semiclassical and quantum oscillation regimes

We will now address the orbital effect (m ≠ 0 and A ≠ 0). The momentum perpendicular to the magnetic field is quantized as \({{{\bf{k}}}}_{\perp }^{2}\to 2N/{l}_{B}^{2}\), where \({l}_{B}=\sqrt{\hslash /eB}\) is the magnetic length, and N = 0, 1, 2,... labels the Landau levels. The eigenenergies become \({\varepsilon }_{0{{\rm{s}}}}=s{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{-{{\rm{s}}}}\) for the lowest Landau levels (LLLs) with N = 0 and \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{Ns\zeta }}}}=\zeta \sqrt{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{2}+N{\eta }^{2}}\) for higher Landau levels with N ≥ 1 (gray lines in Fig. 3a), where \(\eta =\sqrt{2}v\hslash /{l}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\) represents the cyclotron energy. Due to the presence of Zeeman field m, the LLLs are no longer symmetric under electron-hole transformation, while the higher Landau levels remain symmetric, although with broken degeneracy. As demonstrated in the Supplementary Note 2, we rigorously derive the Hall magnetoconductivity (σxy) and transverse magnetoconductivity (σxx) at arbitrary magnetic fields using the Kubo formula within the Landau level representation, neglecting vertex corrections. Disorder effects are incorporated by modeling the Landau levels as Lorentzians with a constant broadening width Γ, corresponding to a relaxation time τ = ℏ/(2Γ). These conductivities can be decomposed into antisymmetric (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{anti}}}}\)) and the symmetric (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\)) terms: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{anti}}}}+{\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\) based on symmetry considerations. The antisymmetric Hall conductivity changes sign under carrier type reversal (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{anti}}}}(\mu )=-{\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{anti}}}}(-\mu )\)), while the symmetric conductivity retains its sign (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}(\mu )={\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}(-\mu )\)), where a, b = x, y. Furthermore, the system exhibits three distinct regimes based on magnetic field strength as illustrated in Fig. 1c: (i) Semiclassical regime (B ≤ χ−1 with \(\chi =\frac{e{v}^{2}\tau }{\mu }\) represents the mobility): The magnetic field is weak enough and disorder broadening smears the Landau levels. (ii) Quantum oscillations regimes: At higher magnetic fields, the system enters a regime characterized by quantum oscillations. (iii) Quantum limit (\(B\ge \frac{{\mu }^{2}-{\Delta }^{2}}{2\hslash {v}^{2}e}\)): In this regime, the magnetic field is strong enough that only the LLL is partially filled.

a Landau level spectrum with orbital effects. The two lowest Landau levels ε0s align precisely with the spin-down states in the energy spectrum of Fig. 2. kc denotes the Fermi wavevector of the lowest Landau level at charge neutrality μ = 0. b Magnetic field dependence of the symmetric Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}-{\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\) at fixed chemical potential μ = 50 meV for different Γ. c Quantum oscillations in the symmetric Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{osi,sym}}}}\) : comparison between numerical calculations and analytical results for μ = 50 meV and Γ = 6 meV. The oscillation frequency field Bf ≈ 10.74 T corresponds to the extremal Fermi surface cross-section via the Onsager relation. d The Hall conductivity σxy as a function of B for μ = 0. The blue line marks the value e2kc/(2πh), corresponding to the separation of the Weyl nodes. The black squares denote the numerical results for disorder broadening Γ = 0.1 meV. The red triangles represent the result for en/B with n as the carrier density. e Antisymmetric component of σxy: numerical results compared with analytical expressions for different μ values with Γ = 3 meV. f Comparison between numerical calculations and the analytical model for the orbital quantum correction \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{O}\) at μ = 50 meV and Γ = 3 meV. g Analytical results for the Hall conductivity at low magnetic fields (B = 0.05 T): \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{LF}}}}\) (red dashed), \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\)(blue dashed), and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) (green dashed) as a function of Γ/μ. The purple line represents the summation of these contributions. The yellow line with squares corresponds to the numerical results. The chemical potential is μ = 20 meV in the simulations.

Using a small magnetic field expansion of the orbital magnetic effects and fully incorporating the Zeeman-induced band splitting, we derive the magnetoconductivities in the semiclassical regime while simultaneously capturing the background contributions that persist into the quantum oscillation regime at higher fields. The symmetric Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\) is given by:

The symmetric Hall conductivity arises from the Zeeman splitting-induced Berry curvature effect, though it is modified by orbital effects. This analytic expression is numerically validated in Supplementary Note 3. For sufficient weak fields (χB ≪ 1), where orbital effects become negligible, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\simeq {\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) exhibits linear field dependence. At stronger fields, orbital effects suppress Fermi surface contribution \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\), while preserving Fermi sea contribution \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\)—the topological component representing nondissipative contributions from states below the Fermi energy. Figure 3b shows the difference between the symmetric Hall conductivity and the Fermi sea contribution, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}-{\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\), plotted as a function of B for various scattering rates Γ. The difference initially increases linearly before decreasing with magnetic field, in excellent agreement with Eq. (4). At small Γ (purple line), orbital effects completely suppress \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{I}}}}\), causing \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\) to converge with \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\). By subtracting the background contribution, we isolate the quantum oscillations in the symmetric Hall conductivity:

where \({S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{(0)}\) and \({S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{(2)}\) are the zeroth and second order coefficients in the kz expansion of \({S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}=\pi ({\mu }^{2}-{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{2})/({\hslash }^{2}{v}^{2})\approx {S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{(0)}+\frac{1}{2}{S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{(2)}{k}_{{{\rm{z}}}}^{2}\). The quantum oscillation fully comes from the Fermi surface contribution. The two bands s = ± produce two distinct Fermi surfaces as a result of Zeeman splitting, giving rise to a beating pattern in quantum oscillations due to their slightly different frequencies. At small magnetic fields, the splitting is minimal, and the symmetric component of the oscillatory Hall conductivity follows the form \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}},{{\rm{osc}}}} \sim \cos (2\pi {B}_{{{\rm{f}}}}/B)\) with Bf ≈ (μ2 − Δ2)/(2eℏv2) ≈ 10.47 T. As shown in Fig.3c, our numerical results show good agreement with the analytical expression in Eq. (5). The relation \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\simeq {\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}\) remains valid even in the quantum limit. This is demonstrated in Fig. 3d for the case μ = 0, where an infinitesimal magnetic field drives the system into the quantum limit. Here, the Hall conductivity exhibits perfect particle-hole symmetry (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{sym}}}}\)) and becomes nonzero for B > BΔ, coinciding with the crossing of the zeroth Landau level through μ = 0 (Fig.3a). In this regime, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{II}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}{k}_{{{\rm{c}}}}}{2\pi h}\), as shown by the blue line.

The antisymmetric Hall conductivity can be expressed as the sum of two main contributions:

where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{LF}}}}\) corresponds to the classical Lorentz force response, and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\) incorporates the correction from the quantum metric, orbital magnetization, and other orbital (O) field-induced effects. Figure 3e compares numerical calculations with analytical results for the antisymmetric Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{anti}}}}\) as a function of magnetic field B at different chemical potential μ. The analytical expressions not only match the numerical results in the classical regime but also correctly reproduce the background behavior that persists into the quantum oscillation regime at higher fields. As shown in Fig. 3f, after subtracting the classical Lorentz force contribution, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\) exhibits a linear field dependence, clearly revealing the quantum corrections arising from orbital magnetic effects. By retaining terms to linear order in the magnetic field, the explicit contributions of different mechanisms to σxy are listed in Table 1. We emphasize that our analytical expressions are derived in the weak scattering limit Γ → 0. When Γ is not small, this decomposition breaks down, but the full Kubo-Streda formula—evaluated using the complete Green’s function without expansion—remains rigorously valid. Fig. 3g shows the contributions to the Hall conductivity as a function of Γ/μ for a small magnetic field. \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) (green dashed line) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\) (blue dashed line) from quantum geometric effects are independent of τ while the classical contribution \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{LF}}}}\) (red dashed line) varies as τ−2. As Γ/∣μ∣ approaches 1, the quantum geometric correction grows comparable to the classical Lorentz force contribution, driving a crossover in the total response from τ−2 to τ0 scaling. The analytical results (purple line) accurately describe this crossover behavior, as confirmed by precise numerical results (yellow line with squares).

To analyze the magnetoresistance, we need to obtain the transverse magnetoconductivity σxx. The transverse magnetoconductivity is given by: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}=\frac{{\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}^{0}}{1+{\chi }^{2}{B}^{2}},\) where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}^{0}\) includes both electron-hole incoherent (\({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}},{{\rm{in}}}}^{0}\)) and coherent (σxx, co0) contributions (See Supplementary Note 4 for the explicit forms of these terms). The incoherent contribution arises from the retarded-advanced channel in Kubo formula, while the coherent contribution originates from the retarded-retarded channel. As \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}},{{\rm{co}}}}^{0}/{\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}},{{\rm{in}}}}^{0} \sim \Gamma /\mu \), electron-hole coherence plays an important role near the band bottom (Γ ~ ∣μ∣).

In the semiclassical regime, the Hall resistivity ρxy ≃ σxy/(σxxσyy) = RHB remains linear in B, with the Hall coefficient RH = ∂ρxy/∂B given by:

When Γ/∣μ∣ ≪ 1, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}},{{\rm{in}}}}^{0}\simeq {\sigma }_{0}\gg {\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}},{{\rm{co}}}}^{0}\) and Lorentz force contribution \({\sigma}_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{LF}}}}\simeq \chi B{\sigma }_{0}\) dominates σxy, then RH ≃ 1/en reduces to the classical result. When Γ ~ ∣μ∣, the contribution from quantum geometric effects and electron-hole coherence can no longer be neglected. Consequently, the Hall coefficient must be modified after accounting for these effects. As shown in Fig. 4a, we plot RH as a function of Γ/μ for a fixed carrier density n, considering both electron- and hole-type carriers. As Γ increases, RH gradually deviates from the classical result 1/en. The analytical solution (red lines) from Table 1, derived through a Γ expansion, agrees well with numerical calculations for Γ/μ < 1. However, in the Γ/μ > 1 regime, higher-order quantum geometric corrections ( ∝ Γ2... ) become significant and must be included to accurate description. The conductivity components exhibit distinct symmetry properties: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{LF}}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\) are antisymmetric under carrier-type reversal (μ → −μ), while \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) is symmetric. This leads to markedly different behavior for two carrier types-with increasing Γ, the hole-type RH can vanish or even change sign when \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{S}}}}\) compensates or dominates the \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{LF}}}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\), whereas the electron-type RH maintains its original sign throughout. By analyzing the frequency of the Shubnikov–de Haas (SdH) oscillations, which is directly proportional to the cross-sectional area of the Fermi surface, the carrier density of the system can be determined58. By comparing the Hall coefficients obtained from Hall resistivity measurements with the carrier density extracted from SdH oscillations, one can identify the field-induced unconventional Hall effect in experiments. This approach provides a robust method to distinguish between conventional Hall effects and anomalous contributions arising from quantum geometry in the out-of-plane magnetic field configuration.

a Hall coefficient RH versus Γ for a fixed carrier density n = ±8 × 1016 cm−3 in the semiclassical regime, for both electron- and hole-type carriers. The blue dashed lines represent the classical result 1/en. The red lines show the analytical results derived from Eq. (7), while the gray squares correspond to numerical solutions obtained from the full expression. b Comparison between experimental data (black dashed line with squares) from ref. 38 and theoretical simulations (red line) based on our model. The simulations use fitting parameters n = 3 × 1016cm−3, Γ = 6.5 meV, Δ = 5 meV, with other model parameters consistent with previous simulations. The blue and red shaded regions indicate the semiclassical regime and quantum limit, respectively. Dashed lines serve as eye guides for ~B and en/(σxxσyy)B−1. Bc ≃ 3.8 T indicates the critical field.

From a semiclassical perspective, the magnetic field modifies the conductivity through corrections to both the Berry curvature and band energy of electronic states59,60,61,62. Using a weak magnetic field expansion of the Green’s function (See the “Methods” section and Supplementary Note 6 for details), we derive τ-independent Hall conductivity \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{(0)}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{O}+{\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{S}\) in terms of quantum geometric quantities. We find \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(0)}={\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(0),{{\rm{wp}}}}+{\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(0){\prime} }\), where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(0),{{\rm{wp}}}}\) represents the previously known contribution derived from semiclassical wavepacket theory59,60,61,62, given by \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(0),{{\rm{wp}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{\hslash }\,\int[d{{\bf{p}}}]\,[(-\frac{\partial f}{\partial \varepsilon })\left({B}_{{{\rm{c}}}}{F}_{{{\rm{cb}}}}{V}_{{{\rm{a}}}}+\frac{1}{2}{\epsilon }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}{\Omega }_{c}\right.({{\bf{m}}}\cdot {{\bf{B}}})-(a\leftrightarrow b)]\). Here, a, b, c denote Cartesian components (with Einstein summation convention), ϵabc is the Levi-Civita symbol, Fcb is the anomalous orbital polarizability (AOP), Ωc the Berry curvature, and m the intraband orbital magnetic moment. The additional term \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(0){\prime} }\) is a new correction obtained through Green’s function techniques, which contains higher-order energy derivatives of the Fermi–Dirac distribution:

where gac is the quantum metric tensor, and \({n}_{{{\rm{ab}}}}={{\rm{Re}}}\langle {\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{a}}}}}{u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}| ({\varepsilon}_{\alpha }-{\hat{H}}_{0})| {\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{b}}}}}{u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\rangle \) with ϵα and \(\left\vert {u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\right\rangle \) as the eigenenergies and eigenstates for the band intersecting the Fermi surface. These terms are non-vanishing and essential for recovering the complete expression for \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{{{\rm{O}}}}\).

Nonlinear Hall resistivity in quantum limit

In the quantum limit, disorder has minimal impact on σxy, allowing us to neglect impurity effects when evaluating σxy. As shown in Supplementary Note 5, the total Hall conductivity can be rigorously shown to satisfy \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}=\frac{en}{B}\), where n is the carrier density, with the charge neutrality point defined as the midpoint between the two LLLs (see Supplementary Note 7). As demonstrated in Fig. 3d, we validate this relation by examining the case where μ = 0. Here, an infinitesimal magnetic field is sufficient to drive the system into the quantum limit. The Hall conductivity exhibits perfect particle-hole symmetry and develops a nonzero value for B > BΔ. Our numerical results for the Hall conductivity (black squares) show excellent agreement with the analytical expression (red triangles), even when Weyl nodes form without orbital effects. This agreement persists because the carrier density can be expressed as n = eBkc/(2πh). If the carrier density is fixed at the charge neutrality point (n = 0), the Hall conductivity vanishes identically (black dashed line). As illustrated by Fig. 1c, the leading-order conductivity σxx arises from the inter-band velocity and the scatterings between the 0th bands with the bands of 1, which are higher-order perturbation effects63. After calculation, we find: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{2\pi ha}\frac{\Gamma }{{t}_{{{\rm{z}}}}}{{\mathcal{F}}}\) where \({{\mathcal{F}}}\) is a dimensionless integral of order unity, weakly dependent on m/Γ and μ/Γ. For estimating ρxy, \({{\mathcal{F}}}\) can be approximated as a constant. σxx is proportional to Γ, while σxy is inversely proportional to B. This leads to a field-driven competition between these two conductivity components. At small field, where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{2}\gg {\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{yy}}}}\), ρxy exhibits a classical linear dependence: ρxy ≃ B/en. Conversely, at larger fields, where \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}^{2}\ll {\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{yy}}}}\), ρxy becomes inversely proportional to B: \({\rho }_{{{\rm{xy}}}}\simeq \frac{en}{{\sigma }_{{{\rm{xx}}}}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{yy}}}}}{B}^{-1}\). The transition between these two regimes occurs at a critical magnetic field:

For larger values of Γ and smaller carrier density n, Bc decreases, making the transition easier to observe. We apply our theory to explain the experimental data from ref. 38. As shown in Fig. 4b, for a low carrier density n = 3 × 1016cm−3, the system enters the quantum limit at around BQL ≈ 1T, indicated by the red shaded region. Quantum oscillations emerge in the regime where χ−1 < B < BQL = (μ2 − Δ2)/(2ℏv2e), as illustrated in Fig. 1. However, when the mobility is relatively low and the carrier density is small, the quantum oscillations in the intermediate field range become difficult to observe. Using \({{\mathcal{F}}}=0.6\) and the band gap and broadening parameters provided in ref. 38, the critical magnetic field is estimated to be Bc ≈ 3.8 T. Our theory accurately explains the experimental results. Additionally, it self-consistently reproduces the longitudinal conductivity, as demonstrated in Supplementary Note 8.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we propose a quantum theory for the unconventional Hall effect in paramagnetic Dirac materials, combining intrinsic band topology with field-induced quantum effects of LLs. By systematically separating the total Hall conductivity contributions based on symmetry and physical origin, we clarify how each component evolves under an applied magnetic field. In the semiclassical regime, quantum geometry effects modify the Hall coefficient, while in the quantum limit, a competition between transverse and Hall conductivities leads to the nonmonotonic field dependence of the Hall effect. This work provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate interplay between quantum geometry, magnetic field, and disorder in Dirac materials, and also offers valuable insights into the origin of anomalous transport phenomena observed in other nonmagnetic Dirac materials, such as Cd3As264,65.

At last, we emphasize the fundamental distinction between our proposed mechanism and conventional multiband models. The origin of the unconventional Hall effect in our framework stems from quantum geometric effects that persist regardless of Fermi surface topology or temperature, whereas multiband models require specific band structure conditions and thermally activated carriers. If angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) reveals a single Fermi surface (exclusively electron- or hole-like) without additional bands crossing the Fermi level, this would rule out multiband contributions to the unconventional Hall effect. In such a scenario, the unconventional Hall response observed at low temperatures (kBT ≪ Δ) must arise from intrinsic quantum geometric effects, as thermally excited minority carriers are exponentially suppressed. This distinction is particularly crucial in systems like ZrTe5, where the bandgap and Fermi level positioning are sensitive to sample stoichiometry and external perturbations. Transport measurements under controlled doping or strain could thus serve as additional tests to isolate the geometric contribution.

Methods

Eigensolutions and Green’s function for the Dirac Hamiltonian in a finite magnetic field

We perform a unitary transformation to Hamiltonian [Eq. (1)], \(U={e}^{i{\tau }_{{{\rm{y}}}}{\sigma }_{z}\frac{\theta }{2}}\) with \(\theta =\arctan \frac{{t}_{{{\rm{z}}}}\sin {k}_{{{\rm{z}}}}}{\Delta ({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})}\), leading to

where the ladder operators are defined as \(a=\frac{v}{\eta }{\Pi }_{{{\rm{x}}}}-i\frac{v}{\eta }{\Pi }_{{{\rm{y}}}}\) and \({a}^{{\dagger} }=\frac{v}{\eta }{\Pi }_{{{\rm{x}}}}+i\frac{v}{\eta }{\Pi }_{{{\rm{y}}}}\), and \({\Delta }_{\parallel }({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})=\sqrt{\Delta {({k}_{z})}^{2}+{({t}_{{{\rm{z}}}}\sin {k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})}^{2}}\). The Hamiltonian \({H}^{{\prime} }\) separates into two subblocks: \({H}^{{\prime} }={H}_{+}\oplus {H}_{-}\) with \({H}_{+}={{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{+}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{z}}}}+\eta a{\sigma }_{+}+\eta {a}^{{\dagger} }{\sigma }_{-},{H}_{-}={{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{-}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{z}}}}+\eta {a}^{{\dagger} }{\sigma }_{+}+\eta a{\sigma }_{-}\) and \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{\pm }({k}_{{{\rm{z}}}})={\Delta }_{\parallel }\pm m\). The current operator is obtained from ja = eiℏ−1[H, ra] with a = x, y denoting the coordinates in the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field. In the subspace s with s = ± , the current operators are \({j}_{{{\rm{x}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}=e{v}_{{{\rm{x}}}}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{x}}}}\) and \({j}_{{{\rm{y}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}=se{v}_{{{\rm{y}}}}{\sigma }_{{{\rm{y}}}}\). The eigenfunctions of the 2 × 2 Hamiltonian are given by

with ξ = y/l + kxl, \(\cos {\varphi }_{{{\rm{ns\zeta }}}}=\zeta {{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}/{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{ns}}}}\), and \(\sin {\varphi }_{{{\rm{s}}}\zeta {{\rm{n}}}}=\sqrt{n}\eta /{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{ns}}}}\). \({\phi }_{{{\rm{n}}}}(\xi )=\frac{{e}^{-{\xi }^{2}/2}}{{2}^{n/2}{\pi }^{1/4}\sqrt{n!{l}_{{{\rm{B}}}}}}{H}_{{{\rm{n}}}}(\xi )\) where Hn denotes the nth Hermite polynomial. The corresponding eigenenergies are \(\zeta {\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{ns}}}}=\zeta \sqrt{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{2}+n{\eta }^{2}}\). The wavefunctions for the LLLs are

with the corresponding eigenenergies given by \({\varepsilon }_{0s}=-s{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{s}\). Then, we can derive the retarded (R) and advanced (A) Green’s functions

with ωR,A = ω ± iΓ. By substituting Eqs. (10) and (11), we can obtain

where the Schwinger phase as \({{\Phi }}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{\perp },{{{\bf{r}}}}_{\perp }^{{\prime} })=\int_{{{{\bf{r}}}}_{\perp }}^{{{{\bf{r}}}}_{\perp }^{{\prime} }}d{{{\bf{r}}}}_{\perp }\cdot {{\bf{A}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{\perp })=-\frac{(x-{x}^{{\prime} })(y+{y}^{{\prime} })}{2{l}_{{{\rm{B}}}}^{2}}\) with r⊥ = (x, y) which breaks the translational invariance explicitly and the translational invariant part is66,67

with \({L}_{n}^{\alpha }(x)\) as the generalized Laguerre polynomials. The Fourier transform of the translational invariant part \(\widetilde{G}(\omega ;{{\bf{r}}}-{{{\bf{r}}}}^{{\prime} })\) can be obtained as

with

where \(x=2| {{{\bf{k}}}}_{\perp }{| }^{2}{l}_{B}^{2}\) with k⊥ = (kx, ky) and the projection operator is Ps = (1 + sσz)/2.

Kubo formula for Dirac materials in a finite magnetic field

The frequency-dependent electrical conductivity tensor is calculated using the Kubo formula: \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}(\Omega )=\frac{{{\rm{Im}}}{\Pi }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{R}(\Omega +i0)}{\Omega }\) where \({\Pi }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{{{\rm{R}}}}\) is the retarded current-current correlation function obtained by analytically continuing the imaginary time expression:

where \({\hat{V}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}=\frac{1}{\hslash }\partial {H}_{{{\rm{s}}}}/\partial {k}_{{{\rm{a}}}}\) is the current operator for subblock s. By substituting Eq. (12) and performing the analytical continuation iΩm → Ω + i0, the magnetoconductivity can be evaluated as66

where fF represents the Fermi-Dirac distribution, \({\omega }^{{\prime} }=\omega +\Omega \), and ωR,A = ω ± iΓ.By performing the trace while integrating out k⊥, we can derive a more manageable form of σab.

Small magnetic field expansion of the Kubo–Streda formula

In the Kubo–Streda formalism, small field corrections to conductivity can be derived from the expansion of the Green’s function in Eq. (12). To linear order in the background electromagnetic fields, the Green’s function takes the form:

Due to translational invariance in the absence of background fields, the zeroth-order Green’s function depends solely on the difference \({{\bf{r}}}-{{{\bf{r}}}}^{{\prime} }\), which is not true for the first-order part of the Green’s function. The Fourier transform of G0 can be derived from the model Hamiltonian: \({G}_{0}^{{{\rm{R}}}/{{\rm{A}}}}(\mu ,{{\bf{k}}})={(\mu \pm i\Gamma -{H}_{0})}^{-1}\). The first-order correction to the Green’s function arising from the magnetic field can be expressed as68:

where the interaction Hamiltonian Hint = J⋅A accounts for the orbital effect of the magnetic field. The spin effect of the magnetic field is fully incorporated in H0 without any approximations. Here, we are considering only the translationally invariant part of the Green’s function, which can be obtained by

Thus, the first-order correction to the conductivity due to the orbital effect of the magnetic field is given by:

with \(\int[d{{\bf{p}}}]=\int\frac{{d}^{3}{{\bf{p}}}}{{(2\pi )}^{3}}\). Here, a, b, c, d,... denote the Cartesian components, and we adopt the Einstein summation convention for repeated indices. The trace can be evaluated by expressing the Green’s function in terms of the eigenenergy basis \({G}_{0}^{{{\rm{R}}}/{{\rm{A}}}}({{\bf{p}}})={\sum }_{\alpha }\left\vert {u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\right\rangle {G}_{0,\alpha }^{{{\rm{R}}}/{{\rm{A}}}}({{\bf{p}}})\left\langle {u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\right\vert \) where \({H}_{0}\left\vert {u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\right\rangle ={\varepsilon }_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\left\vert {u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}\right\rangle \) and \({G}_{0,\alpha }^{{{\rm{R}}}/{{\rm{A}}}}({{\bf{p}}})={(\mu \pm i\Gamma -{\varepsilon }_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}})}^{-1}\). In the analysis of a two-band model, the first-order correction to the conductivity tensor, \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(1)}\), can be divided into two distinct contributions:

1. Two of the band indices of the Green’s functions are identical \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{(1,{{\rm{i}}})}\):

2. Three of the band indices of the Green’s functions are identical \({\sigma }_{ab}^{(1,{{\rm{ii}}})}\) :

In the weak scattering limit (Γ → 0), the product of the four Green’s functions provides the leading contribution at μ ~ εα or εβ, and can be approximated using Dirac delta functions:

and

where \({\delta }^{{\prime} }(\mu -\varepsilon )=\frac{\partial \delta (\mu -\varepsilon )}{\partial \varepsilon }\), \({\delta }^{{\prime\prime} }(\mu -\varepsilon )=\frac{{\partial }^{2}\delta (\mu -\varepsilon )}{\partial {\varepsilon }^{2}}\) and εαβ ≡ εα − εβ.

By substituting Eqs. (16) and (17) into Eqs. (14) and (15), we can obtain the current ja = χabcEbBc in the order O(EB), where the response tensor is given by \({\chi }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}={\chi }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}^{(2)}+{\chi }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}^{(1)}+{\chi }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}^{(0)}\), which are proportional to ∝ τ2, τ1, τ0, respectively. The magnetoconductivity for different orders of relaxation time can be expressed as \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{({{\rm{i}}})}={\chi }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}^{({{\rm{i}}})}{B}_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) with i = 2, 1, 0.

The explicit expressions for magnetoconductivity \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{ab}}}}^{({{\rm{i}}})}\) are given by:

Here, ϵabc represents the Levi-Civita symbol. For a particular band with index β, the AOP is defined as \({F}_{{{\rm{ba}}}}=2{{\rm{Re}}}\frac{{{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{b}}}}^{\beta \alpha }{{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}^{\alpha \beta }}{{\varepsilon }_{\beta \alpha }}+\frac{1}{2}{\epsilon }_{{{\rm{bcd}}}}{\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{c}}}}}{g}_{{{\rm{ad}}}}\) where \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}^{\alpha \beta }=\langle {u}_{\alpha {{\bf{p}}}}| i{\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{a}}}}}| {u}_{\beta {{\bf{p}}}}\rangle \) is the unperturbated interband Berry connection, \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}^{\alpha \beta }=\frac{1}{2}{\epsilon }_{abc}({V}_{{{\rm{b}}}}^{\alpha \alpha }+{V}_{{{\rm{b}}}}^{\beta \beta }){{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}^{\alpha \beta }\) is the interband orbital magnetic moments, with \({V}_{{{\rm{b}}}}^{\alpha \beta }\) being the matrix elements of velocity operator, \({g}_{{{\rm{ab}}}}={{\rm{Re}}}({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}^{\alpha \beta }{{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{b}}}}^{\beta \alpha })\) as the quantum metric tensor, and εβα = εβ − εα. The intraband orbital magnetic moment \({m}_{{{\rm{c}}}}=-\frac{1}{2}{\epsilon }_{{{\rm{abc}}}}{{\rm{Im}}}\langle {\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{a}}}}}{u}_{\beta {{\bf{p}}}}| ({\varepsilon }_{\beta }-{\hat{H}}_{0})| {\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{b}}}}}{u}_{\beta {{\bf{p}}}}\rangle \) and the real part of the quantity \({n}_{{{\rm{ab}}}}={{\rm{Re}}}\langle {\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{a}}}}}{u}_{\beta {{\bf{p}}}}| ({\varepsilon }_{\beta }-{\hat{H}}_{0})| {\partial }_{{p}_{{{\rm{b}}}}}{u}_{\beta {{\bf{p}}}}\rangle \).

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a quantum Hall effect without Landau levels: condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015–2018 (1988).

Nagaosa, N., Sinova, J., Onoda, S., MacDonald, A. H. & Ong, N. P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539–1592 (2010).

Chang, C.-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Burkov, A. Anomalous Hall effect in Weyl metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 187202 (2014).

Checkelsky, J. G. et al. Trajectory of the anomalous Hall effect towards the quantized state in a ferromagnetic topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 10, 731–736 (2014).

Burkov, A. A. Weyl metals. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 9, 359–378 (2018).

Deng, Y. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Science 367, 895–900 (2020).

Bernevig, B. A., Felser, C. & Beidenkopf, H. Progress and prospects in magnetic topological materials. Nature 603, 41–45 (2022).

Zhang, X.-X. & Nagaosa, N. Nonmonotonic Hall effect of Weyl semimetals under a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 166301 (2024).

Belopolski, I. et al. Synthesis of a semimetallic Weyl ferromagnet with point Fermi surface. Nature 637, 1078 (2025).

Hall, E. On the possibility of transvers currents in ferromagnets. Philos. Mag. 12, 157–172 (1881).

Karplus, R. & Luttinger, J. Hall effect in ferromagnetics. Phys. Rev. 95, 1154 (1954).

Sinitsyn, N., MacDonald, A., Jungwirth, T., Dugaev, V. & Sinova, J. Anomalous Hall effect in a two-dimensional Dirac band: the link between the Kubo-Streda formula and the semiclassical Boltzmann equation approach. Phys. Rev. B 75, 045315 (2007).

Onoda, S., Sugimoto, N. & Nagaosa, N. Intrinsic versus extrinsic anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 126602 (2006).

Xiao, D., Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1959–2007 (2010).

Weng, H., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Transition-metal pentatelluride ZrTe5 and HfTe5: a paradigm for large-gap quantum spin Hall insulators. Phys. Rev. X 4, 011002 (2014).

Zhang, J. et al. Anomalous thermoelectric effects of ZrTe5 in and beyond the quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 196602 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Unraveling the topological phase of ZrTe5 via magnetoinfrared spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 046403 (2020).

Chen, R. et al. Magnetoinfrared spectroscopy of Landau levels and Zeeman splitting of three-dimensional massless Dirac fermions in ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 176404 (2015).

Li, Q. et al. Chiral magnetic effect in ZrTe5. Nat. Phys. 12, 550–554 (2016).

Mutch, J. et al. Evidence for a strain-tuned topological phase transition in ZrTe5. Sci. Adv. 5, 9771 (2019).

Zhang, P. et al. Observation and control of the weak topological insulator state in ZrTe5. Nat. Commun. 12, 406 (2021).

Tang, F. et al. Three-dimensional quantum Hall effect and metal–insulator transition in ZrTe5. Nature 569, 537–541 (2019).

Nair, N. L. et al. Thermodynamic signature of Dirac electrons across a possible topological transition in ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. B 97, 041111 (2018).

Ji, S., Lee, S.-E. & Jung, M.-H. Berry paramagnetism in the Dirac semimetal ZrTe5. Commun. Phys. 4, 265 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Discovery of log-periodic oscillations in ultraquantum topological materials. Sci. Adv. 4, 5096 (2018).

Qin, F. et al. Theory for the charge-density-wave mechanism of 3D quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 206601 (2020).

Galeski, S. et al. Origin of the quasi-quantized Hall effect in ZrTe5. Nat. Commun. 12, 3197 (2021).

Okada, S., Sambongi, T. & Ido, M. Giant resistivity anomaly in ZrTe5. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 49, 839–840 (1980).

Izumi, M., Uchinokura, K. & Matsuura, E. Anomalous electrical resistivity in HfTe5. Solid State Commun. 37, 641–642 (1981).

Tritt, T. M. et al. Large enhancement of the resistive anomaly in the pentatelluride materials HfTe5 and ZrTe5 with applied magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 60, 7816 (1999).

Rubinstein, M. HfTe5 and ZrTe5: possible polaronic conductors. Phys. Rev. B 60, 1627 (1999).

Shahi, P. et al. Bipolar conduction as the possible origin of the electronic transition in pentatellurides: metallic vs semiconducting behavior. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021055 (2018).

Wang, C. Thermodynamically induced transport anomaly in dilute metals ZrTe5 and HfTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 126601 (2021).

Fu, B., Wang, H.-W. & Shen, S.-Q. Dirac polarons and resistivity anomaly in ZrTe5 and HfTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 256601 (2020).

Wang, H.-W., Fu, B. & Shen, S.-Q. Helical symmetry breaking and quantum anomaly in massive Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. B 104, 241111 (2021).

Liang, T. et al. Anomalous Hall effect in ZrTe5. Nat. Phys. 14, 451–455 (2018).

Gourgout, A. et al. Magnetic freeze-out and anomalous Hall effect in ZrTe5. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 71 (2022).

Choi, Y., Villanova, J. W. & Park, K. Zeeman-splitting-induced topological nodal structure and anomalous Hall conductivity in ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. B 101, 035105 (2020).

Mutch, J. et al. Abrupt switching of the anomalous Hall effect by field-rotation in nonmagnetic ZrTe5. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2101.02681 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Induced anomalous Hall effect of massive Dirac fermions in ZrTe5 and HfTe5 thin flakes. Phys. Rev. B 103, 201110 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Large Zeeman splitting induced anomalous Hall effect in ZrTe5. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 36 (2020).

Wang, H.-W., Fu, B. & Shen, S.-Q. Theory of the anomalous Hall effect in the transition metal pentatellurides ZrTe5 and HfTe5. Phys. Rev. B 108, 045141 (2023).

Wang, Y.-X. & Cai, Z. Quantum oscillations and three-dimensional quantum Hall effect in ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. B 107, 125203 (2023).

Pi, H. et al. First principles methodology for studying magnetotransport in narrow gap semiconductors with ZrTe5 example. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 276 (2024).

Wu, W. et al. Topological Lifshitz transition and one-dimensional Weyl mode in HfTe5. Nat. Mater. 22, 84–91 (2023).

Galeski, S. et al. Signatures of a magnetic-field-induced Lifshitz transition in the ultra-quantum limit of the topological semimetal ZrTe5. Nat. Commun. 13, 7418 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Possible spin-triplet excitonic insulator in the ultraquantum limit of HfTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 046601 (2025).

Zhao, J. et al. Magnetotransport induced by anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 107, 060408 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Zeeman splitting and dynamical mass generation in Dirac semimetal ZrTe5. Nat. Commun. 7, 12516 (2016).

Jiang, Y. et al. Landau-level spectroscopy of massive Dirac fermions in single-crystalline ZrTe5 thin flakes. Phys. Rev. B 96, 041101 (2017).

Bernevig, B. A., Hughes, T. L., Raghu, S. & Arovas, D. P. Theory of the three-dimensional quantum Hall effect in graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 146804 (2007).

Streda, P. Theory of quantised Hall conductivity in two dimensions. J. Phys. C 15, 717 (1982).

Mahan, G.D. Nonzero Temperatures. in Many-Particle Physics. Physics of Solids and Liquids. 109–185 (Springer, 2000).

Bastin, A., Lewiner, C., Betbeder-Matibet, O. & Nozieres, P. Quantum oscillations of the Hall effect of a fermion gas with random impurity scattering. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 32, 1811–1824 (1971).

Streda, P. & Smrcka, L. Galvanomagnetic effects in alloys in quantizing magnetic fields. Phys. Status Solidi 70, 537–548 (1975).

Smrcka, L. & Streda, P. Transport coefficients in strong magnetic fields. J. Phys. C 10, 2153 (1977).

Pippard, A.B. Magnetoresistance in Metals, Vol. 2 (Cambridge University Press,1989).

Gao, Y., Yang, S. A. & Niu, Q. Field induced positional shift of Bloch electrons and its dynamical implications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 166601 (2014).

Gao, Y. Semiclassical dynamics and nonlinear charge current. Front. Phys. 14, 33404 (2019).

Xiao, C., Liu, H., Zhao, J., Yang, S. A. & Niu, Q. Thermoelectric generation of orbital magnetization in metals. Phys. Rev. B 103, 045401 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Orbital origin of the intrinsic planar Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 056301 (2024).

Zhang, S.-B., Lu, H.-Z. & Shen, S.-Q. Linear magnetoconductivity in an intrinsic topological Weyl semimetal. N. J. Phys. 18, 053039 (2016).

Liang, T. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect in the Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 136601 (2017).

Nishihaya, S. et al. Anomalous Hall effect in Dirac semimetal probed by in-plane magnetic field. Phys.Rev.Lett. 135, 106603 (2025).

Gusynin, V. & Sharapov, S. Transport of Dirac quasiparticles in graphene: Hall and optical conductivities. Phys. Rev. B 73, 245411 (2006).

Tsaran, V. Y. & Sharapov, S. Magnetic oscillations of the anomalous Hall conductivity. Phys. Rev. B 93, 075430 (2016).

Gorbar, E., Miransky, V., Shovkovy, I. & Sukhachov, P. Origin of Bardeen-Zumino current in lattice models of Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 96, 085130 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12304192, No. 11904062, No. 12504049, and No. 12374175), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFA0308603), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grants No. 2024A1515010430, No. 2024A1515012689, and No. 2023A1515140008), Guangdong Province Introduced Innovative R&D Team Program (Grant No. 2023QN10X136), the Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, Hong Kong (Grants No. C7012-21G and No. 17301823), Quantum Science Center of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (Grant No. GDZX2301005). H.W.W. was also supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2024NSFSC1376), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023M740525), and the International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship Program (Grant No. YJ20220059).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W.W., W.S., and S.-Q.S. conceived the project. B.F. and H.X. performed the theoretical analysis and simulation. B.F. and H.X. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huimin, X., Bo, F., Huan-Wen, W. et al. Quantum geometric renormalization of the Hall coefficient and unconventional Hall resistivity in ZrTe5. Commun Phys 8, 390 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02294-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02294-9