Abstract

Energy harvesting is a technique that generates useful work from waste heat. Conventional energy harvesters acting on local thermal equilibrium states are constrained by thermodynamic limits, such as the Carnot efficiency. Quantum heat engines with non-thermal reservoirs are expected to exceed such limits. Here, we demonstrate energy harvesting from a non-thermal Tomonaga-Luttinger (TL) liquid in quantum Hall edge channels, where the non-thermal state is naturally formed due to the absence of thermalization. The scheme is tested with a quantum-dot energy harvester working on a non-thermal TL liquid supplied with waste heat from a quantum-point-contact transistor. Compared to the quasi-thermalized TL liquid, the non-thermal state prepared under the same heat is capable of a larger electromotive force and higher conversion efficiency. These characteristics can be understood by considering a binary Fermi distribution function of the non-thermal state induced by entropy-conserving equilibration. TL liquids are attractive non-thermal carriers for excellent energy harvesting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum heat engines, in which the work is generated by quantum mechanical processes, are attractive for outstanding performances1,2. Particularly, non-thermal states are recognized as useful energy sources to produce higher output power, as compared to thermalized states. Examples include a specific coherent state in a three-level system3, squeezed thermal reservoir4,5, coherent atom ensemble showing superradiance6, nonequilibrium cold atoms prepared by laser cooling7, and so on. These non-thermal states are intentionally produced with specific techniques, which may not be convenient for energy-harvesting applications. Instead, one can consider an integrable system as a working fluid, where the system never relaxes to thermalized states8,9. Even in the presence of small non-integrable perturbation, long-lived non-thermal states (prethermalized states) can appear10,11,12. Non-thermal states can be generated simply by supplying waste heat to an integrable system, and the non-thermal heat can be recycled into useful work by an energy harvester. Among experimentally accessible integrable systems, Tomonaga-Luttinger (TL) liquids in quantum Hall edge channels are attractive for this purpose13. First, the non-thermal states prepared with a heat source can be investigated using an energy spectrometer14,15,16,17. Second, unidirectional heat transport with quantized heat conductance efficiently delivers heat to the engine with minimal energy loss18,19,20. Such heat transport has been discussed with heat Coulomb blockade, anyonic heat flow, and so on21,22,23. However, the advantage of non-thermal TL liquids on thermoelectricity has not been elucidated.

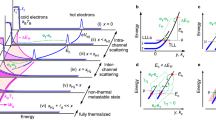

Here, we propose and demonstrate a prototypical energy harvesting scheme with a non-thermal TL liquid, as shown in Fig. 1a. Waste heat generated from an active device is drawn into the TL liquid, and a fraction of the waste heat is converted into electrical power using a heat engine. We shall show below that the performance for a non-thermal (NT) state is superior, as compared to that for an experimentally available quasi-thermalized (QT) state. The NT state provides a larger electromotive force and higher maximum conversion efficiency in the zero power limit. Higher conversion efficiency at maximum power generation is attractive for energy harvesting applications. A strategy for a higher energy recovery ratio is also shown. The results encourage us to utilize a TL liquid as a non-thermal energy resource.

a Schematic heat flow from an active device through a Tomonaga-Luttinger (TL) liquid to a heat engine. The heat power JT generated from the device is converted to electric power P through a non-thermal TL liquid. b Schematic device structure with emitter (E), source (S), and drain (D) regions. Electrons and heat travel unidirectionally in the edge channels Cr,↑ and Cr,↓ of \(r\in \left\{{{\rm{E}}},{{\rm{S}}},{{\rm{D}}}\right\}\). The quantum point contact (QPC) with bias voltage VS and transmission coefficient g generates total heat current JT in the channels (magenta lines). The quantum dot (QD) with an effective bias voltage, Veff, works as a heat engine. Thermoelectricity for non-thermal (NT) and quasi-thermal (QT) states is evaluated by measuring the drain current ID. c Schematic energy diagram of the QD heat engine for NT and QT distribution functions fNT and fQT, respectively, in the source. As compared to the QT state, the NT state under the same JT provides higher electromotive force and higher thermoelectric efficiency. d Scanning electron micrograph of a control device with false color for setup I. The distance between the QPC and the QD is L = 2 μm. e Conductance G of the QPC. The NT and QT states are prepared at G ~ 0.03 e2/h and ~ 0.5 e2/h, respectively. f Coulomb diamond characteristics of the QD. The QD current ID is plotted as a function of the gate voltage VGD for various effective bias voltage Veff. Each trace is offset for clarity. Current steps are associated with transport through the ground state (GS) and excited states (ES, ES', and ES'') of the QD.

Results and discussion

Integrated heat circuit

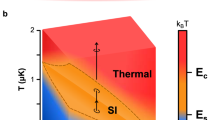

We employ an integrated heat circuit shown in Fig. 1b consisting of a quantum point contact (QPC) as an active device and a quantum dot (QD) as a heat engine in the quantum Hall regime at Landau-level filling factor ν = 2. Two chiral edge channels for spin-up and -down, labeled Cr,↑ and Cr,↓, respectively, are formed along the edge of each quantum Hall region (r = E for emitter, S for source, and D for drain)20. The interaction between the copropagating channels constitutes a TL liquid on each edge. The channels emanating from ohmic contacts (crossed boxes) are in thermal equilibrium at base electron temperature TB, as represented by the blue lines. The QPC conductance G = ge2/h is tuned by the gate voltage VGP. In the tunneling regime at 0 < g < 1 relevant to the present experiment, the total heat power \({J}_{{{\rm{T}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{h}g(1-g){V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}^{2}\) for the effective bias voltage VS is distributed firstly into the channels CE,↑ and CS,↑ by the stochastic partition process, and then fractionalized into the four channels CE,↑, CE,↓, CS,↑, and CS,↓, represented by the thick magenta lines, due to the spin-charge separation characteristic of TL liquids24,25,26,27. As the spin-charge separation is deterministic, the electronic states in the channels remain non-thermal28,29,30,31,32.

By choosing small \(g\ll \frac{1}{2}\), the energy distribution function fS,↑(E) in the source channel CS,↑ can deviate significantly from the thermalized Fermi distribution function fth(E). This study aims to evaluate the NT state, prepared in this manner and described by the distribution function fNT(E), as a heat source. Since a thermalized state is unavailable, we use a QT state prepared at \(g\simeq \frac{1}{2}\) as a reference, which has a distribution function fQT(E) close to fth(E). Namely, we compare the performances for the NT and QT states generated by the same JT by tuning g and VS. The NT state contains an excess of high-energy electrons well above the chemical potential μ and low-energy holes well below μ, as schematically shown in Fig. 1c with fNT(E), while the heat current remains identical to that for fQT(E). It should be noted that this NT state is not a trivial non-thermal state that can be prepared, for example, by mixing two thermal baths at a point contact33. The NT state in the TL liquid is a stationary and equilibrated state that theoretically never relaxes to a thermalized state. This comes from the integrable model of the TL liquids13,14,15 and is attractive for energy harvesting.

We use a QD heat engine to evaluate the NT and QT states as a heat source.34,35. For example, suppose that electrons at energy ε in the source (CS,↑) with chemical potential μS,↑ are transferred to the drain (CD,↑) with chemical potential μD,↑ (>μS,↑). This transport induces a negative current ID (<0) against a positive effective voltage \({V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}=({\mu }_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow })/e\) (>0) in the setup of Fig. 1b to generate net electric power P = − IDVeff (>0). The high-energy electrons in the NT state are expected to provide large electromotive force Vemf defined as maximum Veff to produce finite P > 0.

Significantly, the heat conversion efficiency for the NT state can exceed that for the thermalized or QT state. For simplicity, we consider an idealized QD with a single energy level ε, described by a delta-function-type energy transmission function, neglecting lifetime broadening and excited states36. As single-electron transport extracts heat energy ε − μS,↑ from the source to produce electric energy eVeff = μD,↑ − μS,↑ while discarding the remaining heat ε − μD,↑ to the drain, the conversion efficiency of the idealized engine is given by \(\bar{\eta }=e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}/(\varepsilon -{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow })\). We evaluate this \(\bar{\eta }\) for the NT and QT states in the following experiments.

One can evaluate efficiency for a realistic QD. However, this is not convenient for comparing NT and QT states experimentally because the characteristics depend on the detail (level broadening and excited states) of the QD in different ways for NT and QT states. We believe the idealized efficiency \(\bar{\eta }\) is suitable for evaluating the non-thermal heat source. Nevertheless, we use a realistic QD to reveal the power-generation conditions (eVeff, ε, and μS,↑) for each state, from which we estimate \(\bar{\eta }\).

Measurements

We experimentally demonstrate the energy harvesting scheme using a device fabricated in a standard AlGaAs/GaAs heterostructure with an electron density of 3.1 × 1011 cm−2 (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for the gate pattern). We present data from two measurement setups (setup I in Fig. 1b and setup II in Supplementary Fig. 2a), in which the QD exhibited different characteristics. All measurements were performed at magnetic field B = 6 T (ν = 2) and TB ≃ 150 mK (kBTB ≃ 13 μeV). As shown in Fig. 1d for setup I, we formed a QPC transistor and a QD heat engine with appropriate gate voltages on the gates (yellow regions). The QPC conductance G = IS/VS in Fig. 1e (Supplementary Fig. 2c for setup II) shows clear quantized conductances G = ge2/h at g = 1 and 2. Here, we choose the tunneling regime at g ≃ 0.03 and 0.5 to prepare NT and QT states, respectively. We adjusted the supply voltage \({V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}^{{\prime} }\) under the series resistance RS + RE to maintain the same generated heat power JT for both. The applied voltage \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\right\vert =\) 30–800 μV is sufficiently smaller than the upper limit (a few mV) where the characteristic non-thermal excitation remains37.

The QD is attached to the source channel with tunnel rate ΓS and drain channel with tunnel rate ΓD, which are characterized by the overall tunnel rate \(\Gamma ={\Gamma }_{{{\rm{S}}}}{\Gamma }_{{{\rm{D}}}}/\left({\Gamma }_{{{\rm{S}}}}+{\Gamma }_{{{\rm{D}}}}\right)\) and the resonant width \(w=\hslash \left({\Gamma }_{{{\rm{S}}}}+{\Gamma }_{{{\rm{D}}}}\right)/2\). Figure 1f shows the Coulomb diamond characteristics of the QD in setup I with ΓS ≃ 0.16 GHz and ΓD ≃ 5.7 GHz (Γ ≃ 0.16 GHz and w ≃ 2 μeV) under no heat injection (JT = 0 and g = 0). The current steps associated with the ground state (GS) and excited states (ES, \({{{\rm{ES}}}}^{{\prime} }\), and ES″) of N- and \(\left(N+1\right)\)-electron QD indicate level spacing Δ1 ≃ 400 μeV between GS and ES of N-electron QD, \({\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\simeq\) 80 μeV between GS and \({{{\rm{ES}}}}^{{\prime} }\), and \({\Delta }_{2}^{{\prime} }\simeq\) 400 μeV between GS and ES″ of \(\left(N+1\right)\)-electron QD. The QD in setup II shows ΓS ≃ ΓD ≃ 1 GHz (Γ ≃ 0.5 GHz and w = 0.6 μeV) and \({\Delta }_{1}\simeq {\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\simeq\) 400 μeV (see Supplementary Fig. 2d). For both setups, w is sufficiently narrow (< kBTB ≃ 13 μeV), and thus the level broadening can be neglected for simplicity. The excited states in our QDs can be neglected in the evaluation of Vemf and \(\bar{\eta }\) but modify P, as we discuss later.

The distance L = 2 μm (2.1 μm in setup II) between the QD and the QPC is sufficiently long compared to the length lSC (≲0.1 μm) required for the electronic system to reach the non-thermal steady state, meaning that the electron-electron interaction is significantly strong. The system would be thermalized, if it were a conventional Fermi liquid38. The distance is well below the dissipation length of about 20 μm to the environment (other than the two copropagating channels), where JT is distributed in the four channels almost equally15.

As an example of energy harvesting experiments, we plot the drain current ID as a function of the QD gate voltage VGD in Fig. 2a for an NT state (g = 0.028, VS = 600 μV) and in Fig. 2b for a QT state (g = 0.45, VS = 210 μV), both obtained under comparable JT ≃ 400 fW. Power generation with P > 0 (ID < 0 at Veff > 0 and ID > 0 at Veff < 0, highlighted by red) is seen in the vicinity of the Coulomb blockade peak. Power generation is observed across the wide range of ε and eVeff for the NT state. While power generation ceases at \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right\vert \gtrsim\) 60 μV for the QT state, it persists up to a much larger \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right\vert > \) 100 μV for the NT state.

a, b, Drain current ID as a function of the gate voltage VGD at various effective energy bias eVeff. Positive power generation is highlighted by red. The upper-right and lower-left insets in a show the energy diagrams for positive power generation at eVeff > 0 (ε > μD,↑ > μS,↑) and eVeff < 0 (ε < μD,↑ < μS,↑), respectively, where ε is the electrochemical potential of the quantum dot (QD), and μD,↑ and μS,↑ are the chemical potentials of the drain and source spin-up channels, respectively. c, d Color plot of electric power P = − IDVeff as a function of eVeff and \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\), where \(\bar{\mu }=({\mu }_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }+{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow })/2\) is the average chemical potential. Comparable heat power JT ≃ 400 fW was used in a and c for the NT state, and b and d for the QT state. The NT state provides high electromotive force Vemf ≃ 130 μV and high efficiencies \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\simeq\) 0.65 in the zero power limit and \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\simeq\) 0.45 at maximum power in c, as compared to the QT state (Vemf ≃ 50 μV, \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\simeq\) 0.58 and \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\simeq\) 0.35) in (d). e, f Color plot of P calculated for an idealized QD by using the binary Fermi distribution function fbin with the fraction p = 0.12, the high thermal energy kBTS = 116 μeV, the low thermal energy kBTL = 5.2 μeV, and the heat transfer factor κ = 0.2 for the NT state in e and the thermalized Fermi distribution function fth with the thermal energies kBTth = 42.3 μeV in the source and \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} }=\) 23.2 μeV in the drain for the thermalized state in f. The conditions for ε = μD,↑ and ε = μS,↑, and the idealized efficiency \(\bar{\eta }=\) 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 are shown by the dashed and solid lines, respectively, in (c–f). The estimated \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) and \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) are shown by red and blue dashed lines in (c–f), while those in f coincide with the Carnot efficiency ηC and the Curzon-Ahlborn efficiency ηCA, respectively.

Data was analyzed by considering the non-thermal heat flow, as summarized in Fig. 3a. The total heat current JT ≃ JS,↑ + JS,↓ + JE,↑ + JE,↓ is distributed in the four channels, and the fraction \({J}_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow }\simeq \frac{1}{4}{J}_{{{\rm{T}}}}\) in channel CS,↑ constitutes non-thermal distribution function fS,↑ in the heat source attached to the QD. We are aware that the drain channel CD,↑ is also heated up to the heat current JD,↑ with a heat transfer factor κ due to the long-range interaction14,39. Therefore, fS,↑, fD,↑, and μS,↑, as well as ε, have to be determined to analyze the thermoelectricity.

a Schematic diagram of the analysis. The total heat power JT generated at the quantum point contact (QPC) is divided into non-thermal heat currents JS,↑, JS,↓, JE,↑, and JE,↓. The long-range interaction with heat transfer factor κ induces heat current JD,↑ in the drain channel. The quantum dot (QD) heat engine is attached to the heat source with a distribution function fS,↑ and a chemical potential μS,↑, and the heat drain with fD,↑ and μD↑. The net power P generated by the QD is estimated from the effective bias Veff and the measured current ID. b, c Distribution functions fS,↑ and fD,↑. The current \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}=-e\Gamma [{f}_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}\left(\varepsilon \right)-{f}_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}\left(\varepsilon \right)]\) measures the difference at QD level ε, where Γ is the overall tunnel rate. The difference in ID between b and c with the same ε − μD,↑ but different Veff [(\(=({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}})/e\))] is used to estimate the derivative \(\frac{d}{dE}{f}_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}\). The integrated current KI = ∫IDdε measures the area enclosed by fS,↑ and fD,↑. d KI as a function of μD,↑ (=−eVD), from which μS,↑ is obtained. e The integrated heat currents \({K}_{J,\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }}=\int\left(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\right){I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d\varepsilon\) (the red dashed line) and \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}=\int{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d\varepsilon\) (the red solid line) as a function of μD,↑. \({K}_{J,\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }}\) provides the difference of the heat currents ΔJ (=JS,↑ − JD,↑) independent of μD,↑, and \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) provides ΔJ only at μD,↑ = μS,↑, from which \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) can be determined.

Because of the negligible level broadening (w < kBTB), \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\simeq -e\Gamma [{f}_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow }\left(\varepsilon \right)-{f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }\left(\varepsilon \right)]\) measures the difference of the distribution functions at QD energy ε, as shown in Fig. 3b. The role of fD,↑ can be removed by differentiating ID’s taken with the same \({f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }\left(\varepsilon \right)\) at the same ε − μD condition (compare Fig. 3b, c), from which we estimate \(\frac{d}{dE}{f}_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow }\) and fS,↑. Similarly, fD,↑ can be estimated. We used the following procedure to do this.

The integrated current KI = ∫IDdε over the current peak should measure \({K}_{I}=e\Gamma ({\mu }_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow })\), as shown in Fig. 3d. Therefore, μS,↑ can be determined from the condition for KI = 0. We also consider the integrated heat current \({K}_{J,\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }}=\int(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }){I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d\varepsilon\) over the current peak, where \(\bar{\mu }=({\mu }_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }+{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow })/2\) is the average chemical potential. This \({K}_{J,\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }}\) measures the difference of the heat current ΔJ = JS,↑ − JD,↑ independent of μD,↑, as shown by the red dashed line in Fig. 3e. However, we do not know \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) yet, because ε (\(={\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}+\tilde{\varepsilon }\)) deviates from the gate tunable part εG = αVGD with the lever-arm factor α by unknown shift \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\), which comes from electrostatic shift due to the change of μD,↑ and background charge fractionations. Instead, we calculate \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}=\int{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d\varepsilon\), which depends on μD,↑ and provides ΔJ at μD,↑ = μS,↑ (the red solid line). This \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) is used to estimate \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) for each data point at \(({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}})\) (see Methods).

This allows us to convert an original data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}})\), i.e., ID taken as a function of VGD and VD, to an energy-dependent data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\). As an example, \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}})\) in Fig. 4a is converted to \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\) in Fig. 4e by evaluating KI in Fig. 4b, \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) in Fig. 4c, and \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }\) in Fig. 4d (see Methods). The generated power P = −IDVeff is plotted as a function of \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) and eVeff in the color scale of Fig. 2c for the NT state and Fig. 2d for the QT state. With this conversion, the Coulomb diamond (dashed lines ε = μD,↑ and ε = μS,↑) is symmetrized.

a The original data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} })\) taken as a function of the gate voltage VGD and the nominal drain potential \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) providing the actual drain potential \(e{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}}={\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }+{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,0}}}}\) with predicted offset μD,0 ≃ 30 μeV in setup I. b The integrated current KI as a function of \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\). The overall tunnel rate Γ and the nominal source potential \({\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) is obtained from the fit (the red line) with the relation \({K}_{I}=e\Gamma ({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} })\). The inset shows the magnified plot around KI = 0 (the arrow). c The energy current \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) as a function of \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\). The heat-current difference ΔJ is obtained from \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) value at \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }={\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) (the vertical dashed line). d The fluctuating quantum-dot level \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\) measured from \(\bar{\mu }=({\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}+{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}})/2\), \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }\), as a function of \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\). The black trace is obtained by using the relation \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }=eh\Gamma ({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}-\Delta J)/{K}_{I}\) with the data KI and Γ in b and \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) and ΔJ in (c). The conversion from εG (=− αVGD with the lever-arm factor α) to \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) (\(={\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}+\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }\)) is performed by the red trace of \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }\), which was obtained from the correction of switching events at the vertical bars and linear fitting between them. The red trace is shifted vertically for clarity. The converted plot of \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\). The initial drift X and jump Y in (a) are removed in (e).

By using the converted data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon ,e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\), we obtain the derivative \({\left.\frac{\partial }{\partial E}{f}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\right\vert }_{E = \varepsilon }\simeq \frac{-1}{e\Gamma \epsilon }[{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon +\frac{\epsilon }{4},e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}+\frac{\epsilon }{2})-{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\frac{\epsilon }{4},e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}-\frac{\epsilon }{2})]\) for small ϵ (≲kBTB), and fS(E) is calculated by integrating \(\frac{\partial }{\partial E}{f}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\). fD(E) can be obtained similarly. With this scheme, fS,↑(E) and fD,↑(E) in Fig. 5a for the NT state and Fig. 5b for the QT state are obtained with ϵ ≃ 18 μeV (comparable to kBTB ≃ 15 μeV).

a, b Distribution functions fS,↑(E) of the source spin-up channel CS,↑ and fD,↑(E) of the drain spin-up channel CD,↑ extracted from the data obtained with a NT state (the transmission coefficient g = 0.058, the total heat power JT = 71 fW, and the source voltage VS = 183 μV) in a and a QT state (g = 0.5, JT = 61 fW, and VS = 79 μV) in (b). The empirical binary Fermi distribution function fbin(E) with the fraction p = 0.21, the high thermal energy kBTS = 36 μeV, and the low thermal energy kBTL = 15.5 μeV in (a), the thermalized distribution function fth(E) with thermal energy kBTth = 22 μeV in a and 22 μeV in b, and the Fermi distribution function fB at thermal energy kBTB = 15 μeV for the base temperature TB = 175 mK in a are also shown. c Comparison of initial double-step distribution functions fstp(E), the binary Fermi function fbin(E), and the thermalized function fth(E) for g = 0.03, JT = 410 fW, and VS = 600 μV. d Comparison of initial entropy Sstp for fstp, the non-thermal entropy Sbin for fbin, and the thermalized entropy Sth for fth as a function of normalized conductance g of the QPC. Sbin ≃ Sstp suggests entropy-conserving equilibration. The dashed line indicates the condition g = 0.03 for (c).

Thermoelectricity

We evaluate fundamental thermoelectric characteristics from Figs. 2c, d. First, electromotive force Vemf can be defined as maximum Veff to produce finite P > 0. Data shows higher electromotive force Vemf ≃ 130 μV for the NT state than Vemf ≃ 50 μV for the QT state.

Second, the idealized efficiency \(\bar{\eta }=e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}/(\varepsilon -{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow })\) can be read from the plots \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\). We draw in Figs. 2c and d the solid lines with slopes indicating \(\bar{\eta }=\) 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6. As these lines indicate, power generation under conditions closer to the ε = μD,↑ line implies a higher \(\bar{\eta }\). Although we do not measure efficiency directly, the \(\bar{\eta }\) values in the P > 0 region represent the idealized efficiency that would be achieved if the QD were replaced with an idealized one. This \(\bar{\eta }\) can be used to evaluate the non-thermal heat source. Defining \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) as the maximum \(\bar{\eta }\) in the zero power limit (P = +0), \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) is well beyond 0.6 at large \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right\vert \simeq\) 100 μV and \(\left\vert \varepsilon \right\vert \simeq\) 100 μV for the NT state, while \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) is at most 0.6 for the QT state (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4c for systematic error in \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\)). This confirms the superior efficiency with the NT state.

The white circles in Figs. 2c and d indicate the conditions that yield the maximum power PM. While PM is comparable for the NT and QT states, the corresponding \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) is greater than 0.4 for the NT state, but \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}} < 0.4\) for the QT state. The greater \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) at the maximum power is attractive for energy harvesting applications.

We repeated similar experiments at various JT, and the results from setups I and II are shown by open and filled symbols, respectively, in Fig. 6. Overall, as compared to the QT states (blue symbols), the NT state (red symbols) shows larger Vemf in Fig. 6a, larger \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) in Fig. 6b, and larger \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) in Fig. 6d. The advantage of non-thermal states is confirmed in both setups.

a Electromotive force Vemf. b Maximum idealized efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) in the zero power limit. c Maximum normalized energy-recovery rate R = PM/JTΓ, where electric power PM is generated from total waste heat JT by a quantum-dot (QD) heat engine with overall tunnel rate Γ. d Idealized efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) at the condition of R. Data were taken at transmission coefficient g = 0.03–0.05 (red circles) for NT states and g = 0.3–0.5 (blue squares) for QT states obtained with setup I (open symbols) and II (filled symbols). Error bars represent typical uncertainty in the determination of drain current ID, effective bias Veff, and QD level ε for each data (see Methods). Simulations with the binary Fermi distribution function fbin for the NT state (red lines) and the thermalized Fermi distribution function fth for the QT state (blue lines) are obtained for single- (solid lines) and multiple-level (dashed lines) QD models. e Schematic energy diagram of the QD heat engine in the presence of excited states with level spacings Δ1 and \({\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\). Transport through the level \(\varepsilon +{\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\) increases the thermoelectric current, but that through ε − Δ1 decreases the current.

We also evaluate the heat recovery efficiency PM/JT, which measures how much fraction of waste heat JT can be reconverted to electric power PM. Since PM depends linearly on Γ in the small w limit, the normalized value R = PM/JTΓ is plotted in Fig. 6c to compare the data taken with different Γ. Because the heat of the NT state is distributed over a wide energy range, NT states should provide smaller R, as seen in the experimental data of setup II (filled symbols). In setup I (open symbols), however, NT states show larger R, possibly with the help of the excited state, as we discuss in the simulation.

Non-thermal state

The above characteristics should be attributed to the non-thermal distribution function fNT(E). Because theoretical derivation of fNT(E) is cumbersome32,40,41, we adopt empirical binary Fermi distribution function \({f}_{{{\rm{bin}}}}(E;p,{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}},{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}})=p{f}_{{{\rm{FD}}}}(E;{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow },{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}})+(1-p){f}_{{{\rm{FD}}}}(E;{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow },{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}})\). Here, fFD(E; μ, T) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function with chemical potential μ and temperature T. This fbin reproduces most of the experiments in the literature14,15,37,42. We reconfirmed this fbin by using the same QD at large Veff = 200 μV, as shown in Fig. 7a. The bottom trace obtained without heat injection (g = 0) shows normal exponential tails on both sides of the current peak, from which the base electron temperature TB≃150 mK is estimated. Under heat injection (g > 0), the peak exhibits non-exponential tails on both sides. The right tail measures the hole excitation of the source, as illustrated in the right inset. The data can be fitted nicely by \({f}_{{{\rm{bin}}}}(E;p,{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}},{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}})\), as shown by the red line. The fitted parameters (p, kBTS, and kBTL) are plotted as a function of g in Figs. 7b, c. One can see that p increases with g, kBTS is independent of g, and kBTL gradually increases with g. Figure 7d shows that kBTS increases linearly with VS, where the values extracted from the literature are also plotted.

a Current (ID) spectra taken at various transmission coefficient g and a source bias voltage VS = 400 μV in setup I. The current measures the energy distribution function 1 − fS,↑ of the source channel CS,↑ on the right side, and fD,↑ of the drain channel CD,↑ on the left side of the peak. The insets show corresponding energy diagrams. The red lines show 1 − fbin fitted to the data. b, c g dependence of the fitting parameters (the fraction p, the high thermal energy kBTS, the low thermal energy kBTL) for the data at VS = 400 μV. d VS dependence of kBTS obtained in the present device (the solid circles) and analyzed from the data in the literature (△ for ref. 42, □ for ref. 14, ♢ for ref. 15, and ○ for ref. 37). The dashed lines in b–d show the proposed parameters, p = 4g(1 − g), \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}}=\sqrt{\frac{3}{8{\pi }^{2}}}e{V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\), and \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}}={k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{B}}}}/\sqrt{1-p}\) for thermal energy kBTB = 15 μeV at base temperature TB.

These experimental data suggest us to use p = 4g(1 − g), \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}}=\sqrt{\frac{3}{8{\pi }^{2}}}e{V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\), and \({T}_{{{\rm{L}}}}={T}_{{{\rm{B}}}}/\sqrt{1-p}\) for small \(g\ll \frac{1}{2}\), as shown by the dashed lines in Figs. 7b–d. Namely, p depends only on g, and TS depends only on VS. TL is adjusted to yield heat current \({J}_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow }=\frac{1}{4}{J}_{{{\rm{T}}}}+{J}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\) by assuming the equal heat distribution among the four channels (CE,↑, CE,↓, CS,↑, and CS,↓) on the original heat current \({J}_{{{\rm{B}}}}=\frac{{\pi }^{2}}{6h}{({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{B}}}})}^{2}\) at TB. fbin is determined from the heat injection (g and VS) without any free parameters and is used in the following simulations. The binary Fermi distribution function becomes unclear at g ≃ 0.5, as seen in the topmost trace of Fig. 7a, where the channel can be regarded as in the QT state.

We have extracted the distribution functions fS,↑(E) and fD,↑(E) in Fig. 5a for the NT state and Fig. 5b for the QT state. As compared to the QT state with a single exponential decay in fS,↑(E) at E − μ ≳ 0 of Fig. 5b, the NT state in Fig. 5a shows an additional gentle decay in fS,↑(E) at E − μ ≳ 100 μeV. This fS,↑(E) is close to the above fbin shown by the dotted line. If the electrons were fully thermalized, the Fermi distribution function \({f}_{{{\rm{th}}}}\left(E\right)={f}_{{{\rm{FD}}}}(E;{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow },{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}})\) would appear with the thermalized temperature \({T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}=\sqrt{\frac{3h}{2{\pi }^{2}{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}^{2}}{J}_{{{\rm{T}}}}+{T}_{{{\rm{B}}}}^{2}}\). This \({f}_{{{\rm{th}}}}\left(E\right)\) is closer to the extracted fS,↑(E) for the QT state in Fig. 5b, indicating that the QT state can be regarded as a thermalized reference state.

The drain channel is also heated, though only slightly, as indicated by the smaller magnitude of the gently decaying component of fD,↑(E) in Fig. 5a, possibly due to the long-range interaction between CS,↑ and CD,↑14,39,43. In the following simulations, we assume that a fraction κ ≃ 0.2 of heat in CS,↑ is transferred to CD,↑ to induce non-thermal distribution function \({f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }(E)={f}_{{{\rm{bin}}}}(E;\kappa p,{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}},{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}})\) for the NT state and thermal one \({f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }(E)={f}_{{{\rm{FD}}}}(E;{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow },{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} })\) with \({T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} }=\sqrt{\frac{3h}{2{\pi }^{2}{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}^{2}}\kappa {J}_{{{\rm{T}}}}+{T}_{{{\rm{B}}}}^{2}}\) for the QT state.

Importantly, the binary Fermi distribution function is consistent with the entropy argument. Because spin and charge quasi-particles in TL liquids are non-interacting, the entropy should not change from the initial state. When electrons are partitioned at the QPC with energy-independent g, the initial distribution function in CS,↑ should be a double-step function fstp(E) = (1 − g)fFD(E; μS,↑ − geVS, TB) + gfFD(E; μS,↑ + (1 − g)eVS, TB) with the base temperature TB. This fstp(E) is short-lived due to the electron-electron interaction, and the system results in a long-lived non-thermal state14,15. The system remains in the NT state with fbin for a long distance, rather than relaxing into the thermalized state with fth. Distribution functions fstp(E), \({f}_{{{\rm{bin}}}}\left(E\right)\), and \({f}_{{{\rm{th}}}}\left(E\right)\) for g = 0.03 and VS = 600 μV are shown in Fig. 5c. Corresponding entropies Sstp for fstp, Sbin for fbin, and Sth for fth are plotted as a function of g in Fig. 5d, where the entropy \(S=-\frac{{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}}{hv}\int[f\ln f+(1-f)\ln (1-f)]dE\) is obtained from the distribution function f for a constant velocity v of electrons in the channels. The non-thermalizing nature of the TL liquid is evident from Sstp and Sbin being comparable to each other and smaller than Sth, particularly in the range of 0.005 < g < 0.05, where the experiments were conducted. The empirical function fbin captures the isentropic process of spin-charge separation.

Simulations

The heat-engine characteristics are qualitatively reproduced in the simulation based on the idealized single-level QD. This is justified for setup II (w < kBTB and \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}} < {\Delta }_{1},{\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\)) even at largest JT ≃ 250 fW (kBTS ≃ 70 μeV smaller than \({\Delta }_{1}\simeq {\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\simeq\) 400 μeV). Excited states in setup I play minor roles in the estimate of Vemf and \(\bar{\eta }\)’s, as discussed below. For distribution functions, we use \({f}_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow }(E)={f}_{{{\rm{bin}}}}(E;p,{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}},{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}})\) and \({f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }(E)={f}_{{{\rm{bin}}}}(E;\kappa p,{T}_{{{\rm{S}}}},{T}_{{{\rm{L}}}})\) for NT states and fS,↑(E) = fFD(E; μ, Tth) and \({f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }(E)={f}_{{{\rm{FD}}}}(E;\mu ,{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} })\) for QT states. All parameters (p, TS, TL, Tth, and \({T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} }\)) are determined from the above formulas with kBTB = 15 μeV and κ = 0.2 for each heating condition (g and JT). The current \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}=e\Gamma [{f}_{{{\rm{D}}},\uparrow }(\varepsilon )-{f}_{{{\rm{S}}},\uparrow }(\varepsilon )]\) and the power P = −IDVeff are calculated as a function of \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) and Veff, as shown in Figs. 2e for the NT state and 2f for the thermalized state under equal JT = 400 fW.

For the thermalized state in Fig. 2f, the maximum \(\bar{\eta }\) in the zero power limit is nothing but the Carnot efficiency \({\eta }_{{{\rm{C}}}}=1-{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} }/{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}\), and the \(\bar{\eta }\) at the maximum power (the white circle) is the Curzon–Ahlborn efficiency \({\eta }_{{{\rm{CA}}}}=1-\sqrt{{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{\prime} }/{T}_{{{\rm{th}}}}}\) in the thermodynamic limit34. The non-thermal state in Fig. 2e shows larger \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) (>ηC) and larger \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) (>ηCA). The simulation reproduces the experimental features (larger \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) and \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) in Fig. 2c than those in Fig. 2d). In addition, the calculated Vemf ≃ 150 μV in Fig. 2e is similar to the experimental Vemf ≃ 130 μV in Fig. 2c. Whereas the Vemf calculated for thermalized states in Fig. 2f is infinite, the experimental Vemf ≃ 50 μV in Fig. 2d is practically determined by some unwanted currents. Nevertheless, the idealized single-level model qualitatively reproduces Vemf, \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\), \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\), and R, as also shown by the solid lines in Figs. 6a–d.

Excited states in the QD induce non-ideal current that can degrade or enhance the thermoelectric characteristics. For example, consider the energy diagram (ε > μD,↑ > μS,↑) in Fig. 6e, where the transport through the ground state ε primarily induces thermoelectric effect. Transport through the excited state (electrochemical potential \(\varepsilon +{\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\)) of \(\left(N+1\right)\)-electron QD increases P, and that (ε − Δ1) of N-electron QD decreases P. Because \({\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\simeq\) 80 μeV is smaller than Δ1 ≃ 400 μeV in setup I, the \(\left(N+1\right)\)-electron excited state might contribute dominantly to increase P. We employed the standard master equation to calculate the thermoelectricity in the presence of excited states (see Methods). As shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 6c, the multi-level simulation indicates that R = PM/JTΓ for NT states surpasses R for thermalized states at larger JT. The simulation also suggests that PM can be maximized by tailoring the energy transmission function of the heat engine44. Namely, energy harvesting with N = 0 QDs should be advantageous for maximizing PM. While the excited states modify P, the simulation suggests that the power-generation condition (P > 0) in the \(\left(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right)\) plane does not change significantly, as it is primarily determined by the ground-state transport. Therefore, we use the single-level model to simulate Vemf and \(\bar{\eta }\)’s even for setup I.

Conclusions

In summary, non-thermal TL liquid is an attractive working fluid for heat-energy conversion in energy harvesting. The experiment and simulation show that non-thermal states yield higher electromotive force Vemf, higher conversion efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) in the zero power limit, and higher conversion efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) at maximum power, as compared to the thermalized state. Moreover, non-thermal states can yield higher heat recovery efficiency R by tailoring the energy filtering function to collect high-energy electrons44. The binary Fermi distribution function with the proposed parameters is useful for estimating the performance of the non-thermal states. The scheme and the idea can be applied to more general non-equilibrium states33, other TL systems13,45,46,47,48, and potentially other integrable systems49.

Methods

Device

The device was fabricated in a standard AlGaAs/GaAs heterostructure with a two-dimensional electron system (2DES) located at depth d = 100 nm below the surface. The as-grown 2DES has an electron density of ne = 3.1 × 1011 cm−2 and low-temperature mobility of μe ≳ 106 cm2/Vs. The mesoscopic quantum Hall device has several gate electrodes to selectively activate quantum dots (QDs) and quantum point contacts (QPCs). The fine gate pattern for electron-beam lithography is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The measurements with setups I and II were performed in different cooldowns with different QPCs and different characteristics of the same QD. All measurements were performed at magnetic field B = 6 T (ν = 2) and TB ≃ 150 mK.

The details of setup I are shown in Fig. 1. Those of setup II are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 with the schematic in 2a, scanning electron micrograph of a control device with false color in 2b, quantized conductance of the QPC in 2c, and Coulomb diamond characteristics of the QD in 2d. The lithographic distance between the QD and the QPC is L = 2 μm for setup I and L = 2.1 μm for setup II.

The QPC conductance G = IS/VS is obtained by measuring current IS for the effective bias voltage \({V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}={V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}^{{\prime} }-\left({R}_{{{\rm{S}}}}+{R}_{{{\rm{E}}}}\right){I}_{{{\rm{S}}}}\) under the supply voltage \({V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}^{{\prime} }\) and the series resistance RS + RE ≃ 33 kΩ in setup I and 12 kΩ in II. Clear quantized conductance G = ge2/h, particularly at g = 1, is observed for both setups. The experiments were performed in the tunneling regime at g = 0.03–0.05 and ≃0.5 to prepare NT and QT states, respectively, to generate the total heat power \({J}_{{{\rm{T}}}}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{h}g(1-g){V}_{{{\rm{S}}}}^{2}\). The heat-engine characteristics for NT and QT states are compared with comparable JT by adjusting VS.

The charging energy of the QD is about 1.2 meV for both setups. The tunneling rates ΓS and ΓD on the source and drain side, respectively, for the ground state (GS) transport are made asymmetric with ΓS ≃ 0.16 GHz and ΓD ≃ 5.7 GHz for setup I, and symmetric with ΓS ≃ ΓD ≃ 1 GHz for setup II. The main difference between the two QDs appears in the characteristics of excited states. The QD in setup II shows large \({\Delta }_{1}\,\simeq \,{\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\,\simeq\) 400 μeV as compared to \({\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }\,\simeq\) 80 μeV in setup I. However, Supplementary Fig. 2d for setup II shows vague current steps (the solid line labeled “ES”) at Veff < 0, which suggest large tunneling rate (large lifetime broadening) that depends strongly on Veff. This large broadening might be the reason why the heat-energy conversion is not efficient at Veff < 0 in setup II (Supplementary Fig. 3). Otherwise, the conversion characteristics at Veff > 0 are similar for both setups, as summarized in Fig. 6.

Representative data for setup II

We present heat-engine characteristics obtained with setup II in Supplementary Fig. 3 with line plots of ID in 3a for the NT state prepared at g = 0.058 and JT = 71 fW and 3b for the QT state prepared at g = 0.50 and JT = 61 fW. Positive power generation (ID < 0 at Veff > 0) is highlighted by red. Under these comparable total powers, positive power generation is seen even at large eVeff > 40 μeV for the NT state, but is limited to eVeff < 25 μeV for the QT state. This comparison confirms that larger electromotive force can be achieved with the NT state.

We evaluate the heat-engine performances by converting the gate voltage VGD to \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\), based on the procedure described in the main text. The power P > 0) is plotted in the color scale as a function of eVeff and \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) in Supplementary Fig. 3c for the NT state and Fig. 3d for the QT state. The conditions for the idealized efficiency \(\bar{\eta }=\) 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 are shown by the solid lines with the relation \(\bar{\eta }=e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}/\left(\varepsilon -{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}}}\right)\). Positive power generation (P > 0) can be obtained with a large \(\bar{\eta }\) beyond 0.2 for the NT state but with \(\bar{\eta }\lesssim 0.2\) for the QT state. In this way, more efficient heat-energy conversion can be achieved with the NT state.

Conversion from \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}})\) to \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\)

The QD current \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\left({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\right)\), which was measured by sweeping VGD at various VD values, is converted to the energy-dependent current \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\left(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right)\) in the following way. While μD,↑ = eVD (e > 0) is given by the drain voltage −VD shown in Fig. 1b, we need to precisely determine the chemical potential μS,↑ of the source and the QD level ε, where ε (\(=\,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}+\tilde{\varepsilon }\)) can be shifted by unknown offset \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\) from the gate-tunable part εG = −αVGD.

For simplicity, we assume that \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\) is fixed during each sweep of VGD, while \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\) may change for different VD values. In addition, single-level transport with negligible level broadening is assumed to provide the relation \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}=e\Gamma [{f}_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}(\varepsilon )-{f}_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}\left(\varepsilon \right)]\) with unknown Γ. First, we evaluate integrated current \({K}_{I}({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}})=\int{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) at various μD,↑, which measures \({K}_{I}=e\Gamma ({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}})\). Therefore, Γ and μS,↑ are obtained from the linear fit to the plot of \({K}_{I}({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}})\). The error δVeff in the estimate of \({V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}=({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}})/e\) is obtained from the residuals of the fit.

Second, we evaluate energy current \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}=\frac{-1}{eh\Gamma }\int{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) at various μD,↑, which measures \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}=\Delta J-\frac{1}{eh\Gamma }(\bar{\mu }-\tilde{\varepsilon }){K}_{I}\). Here, ΔJ = JS,↑ − JD,↑ is the difference of the heat current \({J}_{r}=\frac{1}{h}\int(E-{\mu }_{r})[{f}_{r}(E-{\mu }_{r})-\theta ({\mu }_{r}-E)]dE\) between the source (r = S, ↑) and the drain (r = D, ↑). ΔJ can be estimated from the \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) value for the εG scan at Veff = 0 (KI = 0). Therefore, \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }=eh\Gamma ({K}_{J}-\Delta J)/{K}_{I}\) can be estimated for other scans at Veff ≠ 0 (KI ≠ 0).

In principle, charge fluctuations as well as the level shifts in \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\) can be included to obtain \(\varepsilon =\,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}+\tilde{\varepsilon }\). However, this correction does not work precisely at small \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right\vert\) where both \(({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}-\Delta J)\) and KI are small quantities as compared to the experimental noise. Therefore, we correct large and rare switching events seen as jumps in \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) at large \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right\vert\) by using the above formula, and other fluctuations in \(\tilde{\varepsilon }\) are ignored by the linear fit to \(\tilde{\varepsilon }({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}})\) in between the switching events. The error δε in the estimate of ε is obtained from the residuals of the fit at large \(\left\vert {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right\vert\).

The above conversion scheme works well for our data. Here, we present a representative data conversion for Fig. 4a. Because we know finite μS,↑ appears in our setup, the drain chemical potential \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}={\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }+{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,0}}}}\) is varied by \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) (\(=e{V}_{{{\rm{D}}}}^{{\prime} }\)) from a temporary chosen offset μD,0 (= eVD,0) near the expected μS,↑. The original data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}({V}_{{{\rm{GD}}}},{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} })\) obtained by sweeping VGD at various \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) is shown in Fig. 4a, where the highly conductive regions (pink for ID > 5 pA and cyan for ID < −5 pA) roughly determine the transport window (μS,↑ < ε < μD,↑ and μD,↑ < ε < μS,↑). Taking a closer look at the boundaries of the highly conductive regions, one can see an initial drift (marked by X) induced by the previous QD condition just before starting this measurement from \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }=\) 150 μeV, a large jump (marked by Y) associated with switching of nearby impurity states, and the continuous electrostatic shift (not visible as it is tiny) due to the variation of \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\). Since positive and negative ID regions show a complicated pattern, we should rely on the conversion scheme to determine the conditions for Veff = 0 and \(\varepsilon =\bar{\mu }\).

The integrated current KI = ∫IDdεG is numerically obtained with α = 0.036, as shown in Fig. 4b. KI increases almost linearly with \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D}}}}^{{\prime} }\), which can be fitted with the form \({K}_{I}=e\Gamma ({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} })\) by defining \({\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) measured from the temporal offset (\({\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}={\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }+{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,0}}}}\)), as shown by the red line. The fitting suggests eΓ = 20 pA and \({\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }=\) −2.2 μeV, from which \(e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}={\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) is obtained for this data set. The data points scattered around the fit imply the error δVeff ≃ 1 μeV (see the inset at around \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }=0\)).

Next, the energy current \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}=\frac{-1}{eh\Gamma }\int{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}{I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}d{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}\) is numerically obtained, as shown in Fig. 4c. The \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) value at \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }={\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) (the vertical dashed line) provides ΔJ = 190 fW. The initial drift and the large jump are detected in the \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) dependence of \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\), as marked by X and Y, respectively. Then, \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }=eh\Gamma ({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}-\Delta J)/{K}_{I}\) is obtained, as shown by the black line in Fig. 4d. The large fluctuation around \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }={\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) comes from finite noise in the small numerator \(({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}-\Delta J)\) and denominator KI, where \((\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu })\) values are unreliable. Otherwise, the \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\) dependence shows the initial drift (marked by X), the large jump (marked by Y), and the continuous electrostatic shift with the averaged slope of \(\beta =d(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu })/d{\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\simeq\) −0.15 due to the electrostatic shift from varying \({\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\). This β value is consistent with the asymmetry of the Coulomb diamond obtained for a wide range of Veff in the absence of heat injection. For this data, jumps greater than 12 fW in \({K}_{J,{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{G}}}}}\) [marked by the vertical bars in Fig. 4d] are corrected by the above formula, while other fluctuations are ignored, as shown by the red line. We use this \(\tilde{\varepsilon }-\bar{\mu }\) (the red line) to obtain \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\). The ignored fluctuations at large \(\left\vert {\mu }_{{{\rm{D,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}}^{{\prime} }\right\vert\) are considered as the error δε ≃ 5 μeV in the estimate of ε. With eVeff and \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) obtained by the above scheme, ID is replotted as a function of eVeff and \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) in Fig. 4e. The initial drift and the large jump are removed in \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\) plot. The boundary between the positive and negative current regions is now smoothly connected. The boundary is not linear, i.e., its slope \(d(e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})/d(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu })\) is gentle at \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\simeq 0\) and steep at large \(\left\vert \varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\right\vert \gtrsim {k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{T}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\). The scheme determines the conditions for eVeff = 0 and \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }=0\), from which we draw the idealized efficiency \(\bar{\eta }=e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}/(\varepsilon -{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}})\) for \(\bar{\eta }=\) 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 in Fig. 2c. The same conversion scheme is applied to all data obtained for NT and QT states in setups I and II. The error bars in \(\bar{\eta }\) of Figs. 6b and d show the range from \(e({V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}-\delta {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})/(\varepsilon +\delta \varepsilon -{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}})\) to \(e({V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}+\delta {V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})/(\varepsilon -\delta \varepsilon -{\mu }_{{{\rm{S,\uparrow }}}})\) for each data point by considering the errors δε and δVeff.

Energy-harvesting performances

The performances of the energy harvesting in Fig. 6 are evaluated in the following way. We show the representative analysis in Supplementary Fig. 4 by using the converted data in Fig. 2a (the NT state at g = 0.028 and JT = 380 fW) and Fig. 2b (the QT state at g = 0.45 and JT = 420 fW) taken in setup I.

Maximum power PM: For each data [\({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu },e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}})\) as a function of \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) at various eVeff], we record the constrained minimum \({I}_{{{\rm{D,min}}}}\) (<0) among all \(\varepsilon -\bar{\mu }\) values at each eVeff and plot the constrained maximum power \({P}_{{{\rm{m}}}}=-{I}_{{{\rm{D,min}}}}{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) as a function of eVeff in Supplementary Fig. 4a. Here, Pm is normalized by Γ, because Pm should change linearly with Γ which is different for the NT (eΓ ≃ 20 pA) and QT data (≃56 pA). The length of each bar shows the error associated with the current noise δID ≃ 50 fA and δVeff ≃ 1 μeV. The maximum power generation PM/Γ (marked by “max”) and the electromotive force Vemf (the arrows) are determined from this plot for each data set. This Vemf is plotted in Fig. 6a, and R = PM/JTΓ is plotted in Fig. 6c.

Efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) at maximum power: The condition \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{m}}}}-\bar{\mu }\) at the constrained minimum \({I}_{{{\rm{D,min}}}}\) is also recorded to plot the corresponding efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{m}}}}=e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}/\left({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{m}}}}-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}}}\right)\) in Supplementary Fig. 4b. The length of each bar shows the error associated with δVeff ≃ 1 μeV and δε ≃ 5 μeV. The \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\) value at the maximum power generation PM (connected by the vertical dashed lines) represents the efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) at maximum power. This \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) is plotted in Fig. 6d.

The maximum efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) in the zero power limit: The condition \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{z}}}}-\bar{\mu }\) at the boundary between positive and negative ID regions is recorded at each eVeff, and the corresponding efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{z}}}}=e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}/\left({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{z}}}}-{\mu }_{{{\rm{S}}}}\right)\) is plotted in Supplementary Fig. 4c. The length of each bar shows the error associated with δVeff ≃ 1 μeV and δε ≃ 5 μeV. \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{z}}}}\) increases with increasing eVeff for the NT data but decreases for the QT data. The maximum efficiency \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) in the zero power limit is determined from the maximum \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{z}}}}\) in this plot. The \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) value for the QT state involves large uncertainty, as it appears at small eVeff. Nevertheless, the \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) value for the NT state is greater than the averaged \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) value for the QT state. This \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) is plotted in Fig. 6b.

The above scheme is applied to the simulated data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\left(\varepsilon ,e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right)\) for the NT and thermalized states under the same JT = 420 fW, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 4d–f. The calculated Pm/Γ, \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\), and \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{z}}}}\) reproduce the experimental features quite well. Particularly, large \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\) for the NT state exceeds the Curzon–Ahlborn efficiency ηCA in Supplementary Fig. 4e, and large \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\) for the NT state exceeds the Carnot efficiency ηC in Supplementary Fig. 4f. The simulated Vemf, \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{Z}}}}\), \({\bar{\eta }}_{{{\rm{M}}}}\), ηC, and ηCA are shown by solid lines in Fig. 6a–d.

Multi-level simulation

We employed the standard master equation for occupation probability pN,n of n-th level (n = 0 for the ground state and n ≥ 1 for the n-th excited states) of N-electron QD15. Tunneling transition between n-th level Δn of N-electron QD and m-th level \({\Delta }_{m}^{{\prime} }\) of \(\left(N+1\right)\)-electron QD, where the energy levels Δn and \({\Delta }_{m}^{{\prime} }\) are measured from the respective ground state, is characterized by the corresponding chemical potential \({\mu }_{nm}=\varepsilon +{\Delta }_{m}^{{\prime} }-{\Delta }_{n}\) and tunneling rates \({\Gamma }_{nm}^{\left({{\rm{S}}}\right)}\) on the source side and \({\Gamma }_{nm}^{\left({{\rm{D}}}\right)}\) on the drain side. The lifetime broadening is neglected for simplicity. By solving the steady state condition (\(\frac{d}{dt}{p}_{N,n}=0\)) of the master equation, the current ID is calculated as a function of ε and eVeff. In the same manner as the single-level model, we extract PM/JTΓ from the simulated data \({I}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\left(\varepsilon ,e{V}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\right)\) and plot it as a function of JT, as shown by the dashed lines in Fig. 6c. Here, we used the parameters Δ1 = 400 μeV, \({\Delta }_{1}^{{\prime} }=\) 80 μeV, \({\Delta }_{2}^{{\prime} }=\) 400 μeV, \({\Gamma }_{nm}^{\left({{\rm{S}}}\right)}/{\Gamma }_{nm}^{\left({{\rm{D}}}\right)}=\) 0.1, \({\Gamma }_{10}^{\left({{\rm{S/D}}}\right)}/{\Gamma }_{00}^{\left({{\rm{S/D}}}\right)}=\) 6, \({\Gamma }_{01}^{\left({{\rm{S/D}}}\right)}/{\Gamma }_{00}^{\left({{\rm{S/D}}}\right)}=\) 1, and \({\Gamma }_{02}^{\left({{\rm{S/D}}}\right)}/{\Gamma }_{00}^{\left({{\rm{S/D}}}\right)}=\) 10. Compared to the simulation with the single-level model, PM/JTΓ becomes larger particularly for the NT state, because high-energy electrons can pass through the excited states.

Data availability

The data and analysis used in this work are available in the main text, Supplementary Figs., and Supplementary Data 1. Any other relevant data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Myers, N. M., Abah, O. & Deffner, S. Quantum thermodynamic devices: from theoretical proposals to experimental reality. AVS Quantum Sci. 4, 027101 (2022).

Deffner, S. and Campbell, S. Quantum Thermodynamics (Morgan & Claypool, 2019).

Scully, M. O., Zubairy, M. S., Agarwal, G. S. & Walther, H. Extracting work from a single heat bath via vanishing quantum coherence. Science 299, 862 (2003).

Roßnagel, J., Abah, O., Schmidt-Kaler, F., Singer, K. & Lutz, E. Nanoscale heat engine beyond the carnot limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 030602 (2014).

Klaers, J., Faelt, S., Imamoglu, A. & Togan, E. Squeezed thermal reservoirs as a resource for a nanomechanical engine beyond the carnot limit. Phy. Rev. X 7, 031044 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. A photonic quantum engine driven by superradiance. Nat. Photonics 16, 707 (2022).

Mayer, D., Lutz, E. & Widera, A. Generalized Clausius inequalities in a nonequilibrium cold-atom system. Communications Physics 6, 61 (2023).

Kennes, D. M. Adiabatically deformed ensemble: engineering nonthermal states of matter. Phys. Rev. B 96, 024302 (2017).

Chen, Y.-Y., Watanabe, G., Yu, Y.-C., Guan, X.-W. & del Campo, A. An interaction-driven many-particle quantum heat engine and its universal behavior. npj Quantum Inform. 5, 88 (2019).

Kinoshita, T., Wenger, T. & Weiss, D. S. A quantum Newton’s cradle. Nature 440, 900 (2006).

Bloch, I., Dalibard, J. & Zwerger, W. Many-body physics with ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885 (2008).

Kollar, M., Wolf, F. A. & Eckstein, M. Generalized Gibbs ensemble prediction of prethermalization plateaus and their relation to nonthermal steady states in integrable systems. Phys. Rev. B 84, 054304 (2011).

Giamarchi, T. Quantum Physics in One Dimension (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Washio, K. et al. Long-lived binary tunneling spectrum in the quantum Hall Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid. Phys. Rev. B 93, 075304 (2016).

Itoh, K. et al. Signatures of a nonthermal metastable state in copropagating quantum Hall edge channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 197701 (2018).

Altimiras, C. et al. Non-equilibrium edge-channel spectroscopy in the integer quantum Hall regime. Nat. Phys. 6, 34 (2010).

le Sueur, H. et al. Energy relaxation in the integer quantum hall regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 056803 (2010).

Jezouin, S. et al. Quantum limit of heat flow across a single electronic channel. Science 342, 601 (2013).

Sivre, E. et al. Electronic heat flow and thermal shot noise in quantum circuits. Nat. Commun. 10, 5638 (2019).

Konuma, R. et al. Nonuniform heat redistribution among multiple channels in the integer quantum Hall regime. Phys. Rev. B 105, 235302 (2022).

Sivre, E. et al. Heat Coulomb blockade of one ballistic channel. Nat. Phys. 14, 145 (2018).

Rosenblatt, A. et al. Transmission of heat modes across a potential barrier. Nat. Commun. 8, 2251 (2017).

Roura-Bas, P., Arrachea, L. & Fradkin, E. Enhanced thermoelectric response in the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 97, 081104 (2018).

Freulon, V. et al. Hong-Ou-Mandel experiment for temporal investigation of single-electron fractionalization. Nat. Commun. 6, 6854 (2015).

Bocquillon, E. et al. Separation of neutral and charge modes in one-dimensional chiral edge channels. Nat. Commun. 4, 1839 (2013).

Inoue, H. et al. Charge fractionalization in the integer quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 166801 (2014).

Hashisaka, M., Hiyama, N., Akiho, T., Muraki, K. & Fujisawa, T. Waveform measurement of charge- and spin-density wavepackets in a chiral Tomonaga–Luttinger liquid. Nat. Phys. 13, 559 (2017).

Gutman, D. B., Gefen, Y. & Mirlin, A. D. Nonequilibrium Luttinger liquid: zero-bias anomaly and dephasing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 126802 (2008).

Iucci, A. & Cazalilla, M. A. Quantum quench dynamics of the Luttinger model. Phys. Rev. A 80, 063619 (2009).

Gutman, D. B., Gefen, Y. & Mirlin, A. D. Bosonization of one-dimensional fermions out of equilibrium. Phys. Rev. B 81, 085436 (2010).

Kovrizhin, D. L. & Chalker, J. T. Equilibration of integer quantum Hall edge states. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085105 (2011).

Levkivskyi, I. P. & Sukhorukov, E. V. Energy relaxation at quantum Hall edge. Phys. Rev. B 85, 075309 (2012).

Sánchez, R., Splettstoesser, J. & Whitney, R. S. Nonequilibrium system as a demon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 216801 (2019).

Esposito, M., Lindenberg, K. & Van den Broeck, C. Thermoelectric efficiency at maximum power in a quantum dot. Europhys. Lett. 85, 60010 (2009).

Josefsson, M. et al. A quantum-dot heat engine operating close to the thermodynamic efficiency limits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 920 (2018).

Humphrey, T. E., Newbury, R., Taylor, R. P. & Linke, H. Reversible quantum Brownian heat engines for electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 116801 (2002).

Suzuki, K. et al. Non-thermal Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid eventually emerging from hot electrons in the quantum Hall regime. Commun. Phys. 6, 103 (2023).

Pothier, H., Guéron, S., Birge, N. O., Esteve, D. & Devoret, M. H. Energy distribution function of quasiparticles in mesoscopic wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3490–3493 (1997).

Prokudina, M. G. et al. Tunable nonequilibrium Luttinger liquid based on counterpropagating edge channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 216402 (2014).

von Delft, J. & Schoeller, H. Bosonization for beginners — refermionization for experts. Ann. Phys. 7, 225 (1998).

Fujisawa, T. Nonequilibrium charge dynamics of Tomonaga–Luttinger liquids in quantum Hall edge channels. Ann. Phys. 534, 2100354 (2022).

Rodriguez, R. H. et al. Relaxation and revival of quasiparticles injected in an interacting quantum Hall liquid. Nat. Commun. 11, 2426 (2020).

Hashisaka, M., Washio, K., Kamata, H., Muraki, K. & Fujisawa, T. Distributed electrochemical capacitance evidenced in high-frequency admittance measurements on a quantum Hall device. Phys. Rev. B 85, 155424 (2012).

Whitney, R. S. Most efficient quantum thermoelectric at finite power output. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 130601 (2014).

Tarucha, S., Honda, T. & Saku, T. Reduction of quantized conductance at low temperatures observed in 2 to 10 μm-long quantum wires. Solid State Commun. 94, 413 (1995).

Bockrath, M. et al. Luttinger-liquid behaviour in carbon nanotubes. Nature 397, 598 (1999).

Chang, A. M. Chiral Luttinger liquids at the fractional quantum Hall edge. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 1449 (2003).

Auslaender, O. M. et al. Spin-charge separation and localization in one dimension. Science 308, 88 (2005).

Ueda, M. Quantum equilibration, thermalization and prethermalization in ultracold atoms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 669 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Shunya Akiyama and Ryota Konuma for preliminary measurements in the early stage of the study and Haruki Minami, Yasuhiro Tokura, and Keiji Saito for fruitful discussions. This study was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI JP19H05603 and JP23K17302) and “Advanced Research Infrastructure for Materials and Nanotechnology in Japan (ARIM)” program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.F. conceived and supervised the project. T.A. and K.M. grew the heterostructure, and C.L. fabricated the device. H.Y. and M.U. performed the measurements with help from H.T., T.H., and T.F. H.Y., M.U., and T.F. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Olivier Maillet and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamazaki, H., Uemura, M., Tanaka, H. et al. Efficient heat-energy conversion from a non-thermal Tomonaga-Luttinger liquid. Commun Phys 8, 387 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02297-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02297-6