Abstract

Localized small-scale events can influence the global behavior of physical systems in unexpected ways. In partially magnetized plasmas, how localized wave interactions drive large-scale oscillations remains unclear. Here we present experimental evidence that intermittent three-wave coupling between rotating structures leads to a low-frequency breathing oscillation. This oscillation emerges from nonlinear interactions between two coherent spokes with distinct mode numbers. Frequency spectrograms from fast imaging and discharge current signals reveal that these interactions push the system into a nonlinear regime, where both small- and large-amplitude spokes dynamically appear and vanish. During this regime, global light emission decreases as large spokes grow. We also observe energy transfer between local spokes and the global breathing mode, suggesting that the oscillating azimuthal electric field contributes to additional ionization. These findings reveal a coupling between local and global plasma dynamics and may guide future efforts to improve stability and confinement in plasma sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In complex physical systems, small-scale local phenomena can propagate and trigger significant unpredictable large-scale consequences, a concept popularly exemplified by the butterfly effect. This phenomenon holds true across a diverse array of scientific disciplines, including plasma physics, where localized instabilities and their subsequent evolution have profound and far-reaching impacts on the entire system. These instabilities, present in both natural and engineered plasmas, span environments as vast as astrophysical plasmas and as controlled as laboratory experiments1,2,3,4. They are especially important in fields such as fusion energy5,6, space propulsion7,8, and semiconductor processing9,10, where sudden transitions in plasma states present formidable challenges. Managing these challenges involves controlling excessive heat flux in fusion reactor walls, mitigating orbital deviations during space missions, and safeguarding against wafer damage in semiconductor manufacturing. Understanding these dynamic instabilities has become increasingly vital owing to the advancement of technical innovation. The complex mechanisms underlying plasma generation lead to the emergence of various free energy sources, including plasma density and temperature gradients11,12, velocity shear13,14, and beam components15,16. This complexity emphasizes the need to gain a comprehensive understanding of nonlinear coupling phenomena among different instabilities. Consequently, theoretical17,18,19,20 and experimental21,22,23,24 investigations in this area have expanded to explore the captivating realm of nonlinear wave coupling phenomena.

While the understanding of instability physics and its extension to nonlinear phenomena has predominantly focused on fully magnetized plasmas, a growing interest exists in exploring these phenomena in partially magnetized plasmas, as applied in space thrusters and semiconductor processes25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. For partially magnetized plasmas in crossed fields, the instabilities deviate from those observed in large linear devices or nuclear fusion contexts25,26,27,28,29,34,35,36,37,38. These plasmas exhibit distinct attributes, including magnetization and temperature disparities between electrons and ions, and electric fields substantially influenced by boundary conditions. Notably, in long-wavelength-dominated scenarios, the instability is characterized by the rotation of a region (i.e., a rotating spoke) with enhanced light emission, moving at velocities below the E×B velocity and displaying a frequency range of 30–60 kHz30,38,39,40,41. Additionally, the presence of a partially ionized state with a low degree of ionization enables gas dynamics to directly contribute to the phenomenon of breathing oscillations, observed as discharge current fluctuations in the few kHz range. This breathing oscillation is commonly interpreted using a predator-prey framework, in which plasma ionization depletes neutrals and subsequently reduces ionization, allowing neutral recovery in a self-regulating cycle42,43,44. These oscillations are crucial for determining device stability45. Various theories have been proposed to explain these phenomena46,47,48,49,50,51, often discussing them in the context of intense ionization at the source or linking them to plasma energy and transport46.

Contemporary theoretical models underscore the intricate nonlinear behavior inherent in these instabilities. Key findings within these models spotlight phenomena such as intensified electron heating30, amplified ionization via electron vortex formation31, turbulence energy cascades32, and the progression from a linear gradient-drift-driven instability to its nonlinear ionization wave counterpart33. While the theoretical interpretations concerning the nonlinear behavior of the instabilities are inconsistent, experimental evidence regarding the precise nature of these mechanisms is limited. In particular, rotating spokes and breathing oscillations have traditionally been treated as independent research topics. This distinction has overlooked the potential nonlinear coupling between these two instabilities, posing a significant limitation to understanding the mechanisms of instabilities in partially magnetized plasmas. We argue that this lack of theoretical agreement stems from a deficiency in experimental evidence detailing the nonlinear characteristics and coupling between instabilities in partially magnetized plasmas.

This paper presents the three-wave coupling between sporadic spokes and breathing oscillation in partially magnetized cross-field plasmas and their causal relationship for the first time, to the best of our knowledge. Leveraging advanced experimental capabilities, our study created an optimal environment for observing three-wave coupling using a cylindrical hot cathode Penning source to identify eigenmodes with distinct azimuthal mode numbers, notably free from MHz range interferences52,53. We also measured radially propagating breathing oscillations54. Using these well-measured data, the distinct patterns between interacting local azimuthal modes and the emergence of global breathing are experimentally confirmed in the Penning source(see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Results

Observation of local and global plasma oscillations using fast camera diagnostics

Initially, we analyzed the measurement results from the fast camera results to gain insights into the internal structure of the plasma over time (see “Methods”). A short video clip is provided as Supplementary Video 1. By eliminating the mean intensity of each pixel, we processed the images to represent fluctuating light emission. The original fluctuating image was processed into three separate images. The original fluctuating images without digital filtering are located on the left side (marked as 1) in Fig. 1b. From the digital band pass filtering of the original images, further images showing internal modes were obtained; column 2 to capture the fluctuations with frequencies less than 20 kHz, column 3 for 30\(-\)40 kHz, and column 4 for 60\(-\)70 kHz. These frequency components of 30\(-\)40 kHz and 60\(-\)70 kHz have been identified previously as rotating spokes driven by collisionless Simon-Hoh instability55. This is further supported by kinetic simulations that reproduce spoke formation as a nonlinear outcome of the collisionless Simon–Hoh instability, even in the absence of ionization56. In this experiment, we denote rotating spokes with a large amplitude at 30\(-\)40 kHz as the large spoke (LS) and rotating spokes with a small amplitude at approximately 60\(-\)70 kHz as the small spoke (SS). Our recent studies have demonstrated the radial propagation characteristics of low-frequency oscillations (less than 20 kHz)53,57. Accordingly, breathing oscillations (BO) is defined in this work as the low-frequency component below 20 kHz. Please note that the frequency values of each component vary with the magnetic field (see Supplementary Fig. 2). In the following section, each component will be more precisely identified and denoted under specific magnetic field conditions.

Four filtered images of plasma light emission during the (a) pre-breathing and b breathing phases. The color bar represents fluctuating light emission values obtained after subtracting the average intensity from the total signal. c Spectrogram of \({\widetilde{\gamma }}_{55}\) with the color bar representing the normalized FFT amplitude. The black line indicates the raw signal of \({\widetilde{\gamma }}_{55}\). d Spectrogram of the discharge current \({I}_{{dis}}\) with the color bar representing the normalized FFT amplitude. The black line indicates the raw \({I}_{{dis}}\) signal. (Supplementary Data 1).

We defined the sudden decrease in brightness at frequencies below 20 kHz as the onset of breathing, and the period immediately preceding this event as the pre-breathing phase, as shown in column 2 of Fig. 1a, b. We select one of the pixels in images \({\widetilde{\gamma }}_{55}\) indicated by a small black dot in column 1 of Fig. 1a to clarify its temporal behavior. The spectrogram of \({\widetilde{\gamma }}_{55}\) is shown at Fig. 1c; the pre-breathing and breathing phases are outlined by blue and magenta dashed boxes, respectively. From this spectrogram, we can observe the sporadic nature of each mode. The breathing phase coincides with the sudden decrease in \({I}_{{dis}}\), as shown in Fig. 1 d. Notably, in contrast to the breathing mode commonly observed in Hall thrusters, which tends to exhibit periodic behavior, the BO identified in this study is distinctly sporadic pattern of formation and dissipation. The sporadic dynamics of modes indicate the absence of a specific, predictable cycle. This sporadic nature has led to the hypothesis that nonlinear wave coupling is actively occurring within the source.

Time-averaged electrical measurement of local and global plasma oscillations

We verified the existence of the spokes and breathing oscillations by electrical probes (see Methods). In Fig. 2a, the radial profile of the FFT results of floating voltage signal \({V}_{f}\) is presented at \({B}_{{\rm{z}}}\) of 128 G. First, as analyzed from the camera data, three distinct frequency peaks—BO, LS, and SS—were clearly observed in the frequency spectra. Dominant fluctuation frequencies of 3 kHz, 30 kHz, and 60 kHz remain nearly consistent across the radial direction, emphasizing the characteristic eigenmode of the system (Fig. 2b). Figure 2c illustrates the radial variation of the fluctuation levels for each mode, with the peak magnitude of the fluctuation at around 9 mm, and all modes displaying a similar profile. Using the Beall technique52,58 on \({V}_{f}\) with a two-tip Langmuir probe, azimuthal mode numbers corresponding to frequencies 3 kHz, 30 kHz, and 60 kHz were identified as 0, 2, and 3, respectively (small figure in Fig. 2a). The spokes and breathing oscillations measured through the fast camera were consistent with the results obtained from electric probes.

a Frequency spectra of the floating potential \({V}_{f}\) measured with a Langmuir probe at axial magnetic field \({B}_{z}\) of 128 G. The small inset shows the Beall plot at radial position \(r\) = 14 mm, where the x-axis is the azimuthal mode number and the color bar indicates the normalized power spectral density. b Frequency \(f\) of each azimuthal mode. c Amplitude spectra \(\left|P\left(f\right)\right|\) of each mode. Here, \(r\) denotes the radial distance from the center of the plasma source and \(\left|P\left(f\right)\right|\) is the single-sided amplitude spectrum at frequency \(f\). “Mode #” labels indicate the azimuthal mode number corresponding to each frequency component. (Supplementary Data 2).

However, an additional spoke structure that was not observed in the camera data was identified through probe measurements. As shown in Fig. 2c, the amplitude of this spoke is very small (approximately at the 0.1 level), and due to its weak signal, it was not possible to extract a distinct mode number using Beall analysis. It is presumed that this component was undetectable in the camera measurements due to its low optical emission and short lifetime. This newly emerged spoke structure at 90 kHz is hereafter referred to as the Mode-Coupled Spoke (MCS). As will be discussed in the following section, the MCS is a result of three-wave coupling between the LS and SS modes. Notably, these two spokes can readily couple due to their harmonic frequency relationship (30 kHz + 60 kHz = 90 kHz) at the peak location (Fig. 2c).

Bicoherence of electric field fluctuation and their nonlinear energy transfer

A high order spectral analysis was performed to validate the hypothesis made in Fig. 1. The degree of nonlinear coupling among three different waves was assessed via auto-bicoherence analysis of the oscillating azimuthal electric field \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) (see “Methods” for a detailed description of the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) measurement). In the experiment, the mean \({E}_{{field}}\) was measured as 460 V/m. For the analysis of \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\), the mean value of \({E}_{{field}}\) were removed. This analysis explores the phase relationship between two arbitrary waves (\({f}_{1}\) and \({f}_{2}\)) and their corresponding summed frequency wave (\({f}_{1}+{f}_{2}\)). The results of a bicoherence analysis range from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no coupling between frequencies and 1 signifies strong coupling59,60. This analysis involved ensemble averaging across numerous statistically analogous instances, totaling 359 cases for the pre-breathing and breathing phases, effectively eliminating arbitrary or coincidental phase matching. The formula for calculating the bicoherence \({b}^{2}({f}_{1},{f}_{2})\) can be found elsewhere59,60. In the pre-breathing phase (before the breathing event), nonlinear interactions were predominantly observed among spokes (e.g., \({f}_{1}\,\)~ 30 and 60 kHz and \(\left|{f}_{2}\right|\) ~ 30 and 60 kHz in Fig. 3a). In contrast, the bicoherence spectrum during the onset of the breathing oscillation shows enhanced nonlinear interactions between low-frequency BO components (3 kHz) and a broad range of higher-frequency modes, including the dominant spokes at 30 and 60 kHz. This is indicated by increased bicoherence in black-dashed box in Fig. 3b. Note that the lower triangular region mathematically represents interactions with the complex conjugate of the signal, and the negative sign on \({f}_{2}\) does not correspond to the actual physical rotation direction of the plasma.

Bicoherence \({b}^{2}({f}_{1},{f}_{2})\) in arbitrary units during the (a) pre-breathing and b breathing phases. c Summed bicoherence \(\sum {b}^{2}(\, {f}_{1},{f}_{2})\) corresponding to (a) and (b). The black dashed line indicates the statistical significance threshold obtained from surrogate testing. d Total nonlinear spectral power transfer \(\sum {T}_{f}\) as a function of frequency during the dissipation of spokes and the onset of the breathing oscillation. The \(\sum {T}_{f}\) and error bars are obtained from measurements at six radial positions (\(r=9\) to 14 mm with 1 mm interval). Black arrows indicate the directions of power flow into and out of specific frequencies \(f\). (Supplementary Data 3).

The significance of this coupling phenomenon was further validated by the summed wavelet bicoherence \(\sum {b}^{2}(\, {f}_{1},{f}_{2})\)59,60(see “Methods”). This result demonstrates the nonlinear interaction of the breathing oscillation of 3 kHz and the LS and SS. Such a coupling pattern exceeds the statistical significance level, affirming the physical validity of the nonlinear coupling (Fig. 3c). The notable findings from this analysis include the emergence of MCS at 90 kHz and its amplification during the breathing phase (Fig. 3c), indicating the mode coupling and nonlinear effects, as the frequency of the new wave matches the sum of the frequencies of the existing two modes (\(30\,{\rm{kHz}}+\,60\,{\rm{kHz}}=90\,{\rm{kHz}}\)). Note that the 90 kHz component is observed directly in diagnostics and emerges through nonlinear three-wave coupling, as revealed in the bicoherence maps.

Moreover, having confirmed the nonlinear coupling through bi-coherency analysis, we were prompted to closely analyze the nonlinear power transfer across different frequencies, a phenomenon frequently observed during mode coupling. This can be calculated using the Ritz method61. The formula for calculating the total nonlinear spectral power transfer \(\sum {T}_{f}\) is detailed in elsewhere61,62. For this study, frequency is utilized as a substitute for wavelength. Taylor’s hypothesis is verifiably satisfied (i.e., the lifetime \({\tau }_{L}\) of the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) must exceed the transit time \({\tau }_{P}\) of the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) between the two points), as \({\tau }_{L}\) and \({\tau }_{P}\) are approximately 2.0 \(\mu s\) and 0.4 \({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{s}}\), respectively. The result is shown in Fig. 3 d. The \(\sum {T}_{f}\) increase in the regions around 3 kHz and 90 kHz, along with the decrease in the 30 and 60 kHz regions, is particularly notable. This indicates that the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy in LS and SS is released while the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy in frequencies at 3 kHz and in the new MCS at 90 kHz is absorbed. Noting that the outflow direction of \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy in the spokes does not mean that the energy is completely depleted; rather, it is continuously produced and consumed during the discharge. Given the sporadic nature of various modes in the source, nonlinear power transfers occur intermittently during the mode coupling between pre-breathing and breathing intervals. This result raises a critical question about the role of the released \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy in the source. As a substantial \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy outflow is observed, we anticipate that the released \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy acts as free energy, contributing to changes in internal parameters.

Time evolution of gas and plasma parameters

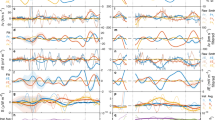

The sporadic light emission of the internal mode, as shown in Fig. 1a, b, along with the intermittently released \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) energy in Fig. 3 d, prompted us to estimate internal parameters, including temporal changes in neutral gas and plasma density, as well as local \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\). One of the novel characteristics of the Penning source is that \({I}_{{dis}}\) is proportional to the neutral pressure, allowing it to be used as a pressure gauge63,64. In our Penning source, the linear relation between neutral pressure \({P}_{{source}}\) and \({I}_{{dis}}\) is guaranteed under our experimental conditions (\({P}_{{source}}=166{I}_{{dis}}-215\)). To acquire statistically significant data of \({P}_{{source}},\) total of 57 breathing cases were obtained and ensemble-averaged. The time evolution of \({P}_{{source}}\) was then tracked, as shown in Fig. 4a. In the breathing phase, a sharp decrease in neutral pressure is measured, which corresponds to a sudden drop in light intensity, as shown in Fig. 1b. By using the ensembled ion saturation current \({I}_{{isat}}\) of the same breathing cases, the time-varying density of electrons \({n}_{e}(t)\) was obtained (see Methods for a detailed description of the measurement). Subsequently, the density of each mode (namely, \({n}_{e,{\rm{BO}}}\), \({n}_{e,{\rm{LS}}}\) and \({n}_{e,{\rm{SS}}}\)) was derived by digitally filtering \({n}_{e}(t)\), as shown in Fig. 4b–d. Specifically, \({n}_{e,\,{\rm{BO}}}\) is band-filtered below 20 kHz, while \({n}_{e,\,{\rm{LS}}}\) and \({n}_{e,\,{\rm{SS}}}\) are band-filtered within the 30\(-\)40 kHz and 60\(-\)70 kHz ranges, respectively.

a Neutral pressure \({P}_{{source}}\), b electron density \({n}_{e}\) (black) and the breathing-oscillation component \({n}_{e,{BO}}\) (red). c Large-spoke component of the electron density \({n}_{e,{LS}}\). d Small-spoke component of the electron density \({n}_{e,{SS}}\). e Total fluctuating electric field \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) and the breathing-oscillation component \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field},{\rm{BO}}}\). f Large-spoke component of the electric field \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field},{\rm{LS}}}\). g Small-spoke component of the electric field \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field},{\rm{SS}}}\). In b–d, f, g, the blue lines indicate the amplitude envelope of each waveform. The probe is located at \(r\) = 10 mm. All data are ensemble-averaged, with 57 breathing cases for (a–d) and 74 breathing cases for (b–d). (Supplementary Data 4).

One noticeable feature is that during the breathing phase, an increase in \({n}_{e,{\rm{LS}}}\) is observed, eventually leading to an overall increase in \({n}_{e}\). Assuming that changes in the neutral pressure \(\triangle {P}_{{source}}\) during the breathing phase (12.9 mPa, indicated by an arrow in Fig. 4a) are caused by electron-neutral impact ionization, the corresponding increase in the electron density \({n}_{e,{add}}\) is calculated as \(4.06\times {10}^{17}\,{{\rm{m}}}^{-3}\) using the simple relation \(\triangle {P}_{{source}}={n}_{e,{add}}{k}_{B}{T}_{{gas}}.\) The gas temperature \({T}_{{gas}}\) is assumed to be 0.2 eV, estimated by ion temperature measurement results in a similar set-up and conditions65. The changes in electron density \(\triangle {n}_{e}\) during the breathing phase are obtained by calculating the difference between the initial density \({n}_{e,{initial}}\) and the maximum density \({n}_{e,\max }\), as shown in Fig. 4b. Notably, \(\triangle {n}_{e}\) is measured as \(2.65\times {10}^{17}\,{{\rm{m}}}^{-3}\), which is comparable to the expected change in \({n}_{e,{add}}\). This indicates that the ionization process is actively ongoing during the breathing phase while instantaneously consuming neutral gas. While the additional ionization could be contributed to LS as well as other components, precise partitioning among them was not confirmed in this study. Then, as \({P}_{{source}}\) recovers to its next pre-breathing phase, \({n}_{e}\) and \({n}_{e,{\rm{LS}}}\) decreased. These tendencies of increased ionization are only observed during the breathing phase.

We analyzed the time evolution of \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}},\) used for nonlinear coupling analysis. Data from 74 breathing events were ensemble averaged, and the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{\rm{BO}}}\) (filtered below 20 kHz), \({\widetilde{E}}_{{\rm{LS}}}\,\)(band-filtered within the 30\(-\)40 kHz) and \({\widetilde{E}}_{{\rm{SS}}}\) (band-filtered within the 60\(-\)70 kHz) are depicted in Fig. 4e–g. Contrary to the increase in \({n}_{e}\) observed during the phase transition from pre-breathing to breathing, shown in Fig. 4b–d, there is a decrease in local \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\), as illustrated in Fig. 4e. Notably, reductions in the intensities of both \({\widetilde{E}}_{{\rm{LS}}}\) and \({\widetilde{E}}_{{\rm{SS}}}\) are measured during the phase transition, which correspond to the trends of nonlinear power transfer in the LS and SS frequency bins shown in Fig. 3 d. To the best of our knowledge, the observed time lag between the azimuthal electric field and plasma density variations has not been reported in other theoretical and experimental studies. After the breathing phase, the recovery of neutral pressure to its original levels and the subsequent decrease in density indicate that this ionization was driven by a transient supply of energy, as no additional external power was supplied during the Penning discharge. A drop in the \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) after the breathing phase is also observed. We expect that this phase marks the beginning of the next wave-related events, though this is beyond the scope our current study.

One notable observation from the measurements is that, despite the constant external power is supplied during the discharge of plasma, there were intermittent and transient occurrences of additional ionization and reductions in light intensity. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the source of the additional energy that enables these changes. Eventually, we find a possible energy source facilitating the breathing oscillation mechanism by highlighting the intermittent strengthening of azimuthal \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) in the spokes led to the breathing oscillation. Given the investigated nonlinear mode coupling and resultant changes in plasma parameters, we emphasize that a significant outflow of \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) power from the spokes’ bins during the breathing phase does not simply vanish; rather, it can be transformed into free energy. This free energy is not constrained to maintaining the oscillations of specific electric field modes and thus can be redirected to other processes, redistributing energy within the plasma, which in turn can enhance ionization rates. In addition, during the breathing phase, the super-positioned electric field oscillation \({\widetilde{E}}_{{coupled}}\) during coupling can accelerate the plasmas. The combined electric fields from both modes (LS and SS) can induce instantaneous acceleration of electrons leading to ionization. This is likely because the real-time evolution of the electric field is highly spiky for both modes (data not shown here as all are ensemble averaged). Moreover, the intensities of \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field},{\rm{LS}}}\) and \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field},{\rm{SS}}}\) increase reciprocally during the breathing phase, indicating dynamic changes in the local electric field. The nonlinear coupling and energy exchange between the local, internal waves and global wave are the key of phenomenological, causal mechanism as follows: (1) two sporadic spokes are created in the Penning source; (2) the spokes undergo mode coupling as they are in harmonic relation, resulting in nonlinear coupling and energy transfer; (3) as the field energy in the spokes is transferred to other domain, it causes additional ionization; and (4) in the lab frame, the reduced light emission caused by the instantaneously decreased neutral pressure appears as ‘breathing’.

Our findings not only provide pioneering insights into the nonlinear interplay between coherent spokes and breathing oscillations in partially magnetized cross-field plasmas but also enhance our understanding of inherent instabilities in cross-field sources, thereby offering clear directives for future research and technological applications. Moreover, as mode coupling and the resulting phenomena observed in this study are actively researched in various plasma conditions including high-temperature plasmas66, they enable detailed and accessible research on nonlinear coupling phenomena in small devices, which are challenging to study in larger devices such as Tokamaks. Additionally, more detailed experiments and research are required to address further questions, such as why only the \({n}_{e,{\rm{LS}}}\) increases during the breathing phase and what the threshold conditions are for the breathing phase in a given mode coupling.

Methods

The penning source

The Penning source used in our study is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1 and described elsewhere52,53,54,55,57. The Penning apparatus comprises two main sections: a relatively hot plasma column (spanning \(0-8\) mm from the radial center) and an extraction region. The plasma column defines a cylindrical area between two axial boundaries: a negatively biased hot cathode with an outer shield (right side) and an anti-cathode (left side). The cylindrical source wall is grounded, establishing the reference potential for the entire plasma source system. Throughout the experiments, the conditions were maintained at an average discharge current \({I}_{{dis}}\) of 1.7 A, a discharge voltage of 45 V, and an argon pressure of 66 mPa in the source. Fast camera measurements were performed at an axial magnetic field strength of 159 G, while electrical probe measurements were conducted at 128 G. Note that the small difference in magnetic field does not lead to significant changes in the phenomenology of the two-spoke structure and breathing oscillation, as confirmed in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Fast camera measurement

The fast camera (Phantom V711) was installed to capture visible light changes in the plasma with a spatial resolution of \(-\)18 to 18 mm via a vertical slit with 128 × 34 pixels. It operated with a temporal resolution of 4.76 μs (210 kframe/s) and a shutter time of 4.3 μs, providing sufficient resolution to cover the instability dynamics. We conducted measurements facing the slit to avoid significant losses of magnetic field-aligned electron. The sporadic dynamics of breathing oscillations and rotating spokes were verified using a fast camera and simultaneous measurement of \({I}_{{dis}}\), without installing a Langmuir probe.

Discharge current measurement

Discharge current \({I}_{{dis}}\,\) oscillations were measured with a differential probe through a 0.5 Ω non-inductive resistor connected between the ground and anode of the discharge circuit. Measurements over 200 ms captured non-stationary behaviors in frequency spectrograms. The setup detected up to 11,764 oscillation cycles, with a maximum observable period of approximately 17 μs.

Bicoherence and summed bicoherence analysis

To quantify nonlinear three-wave coupling between plasma modes, we performed a frequency-domain (Fourier-based) bicoherence analysis on the azimuthal electric field \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\). The bicoherence \({b}^{2}({f}_{1},{f}_{2})\) measures the normalized phase coherence between two frequency components \({f}_{1}\), \({f}_{2}\), and their nonlinear interaction product \({f}_{1}+{f}_{2}\). It ranges from 0 (no coupling) to 1 (perfect phase locking), and is defined as:

Here, \(X\left(f\right)\) denotes the Fourier transform of each windowed segment, and \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle\) denotes ensemble averaging over multiple segments. The analysis was implemented using a custom MATLAB script developed in-house, following the standard formalism introduced by Kim and Powers59. Each signal was divided into overlapping segments (50% overlap), windowed using a Hanning function, and transformed with a 256-point FFT. The sampling frequency was 500 kHz, yielding a frequency resolution of 1.953 kHz. The resulting bicoherence maps were symmetrized and FFT-shifted to center zero frequency.

The analysis was ensemble-averaged over 359 statistically similar events, which were automatically aligned by the onset of breathing oscillations. Statistical significance of bicoherence values was assessed using surrogate testing: surrogate signals were generated by phase-randomizing the original time series, and the 95th percentile of their bicoherence distribution was used as a significance threshold. This ensures that the reported coupling arises from true nonlinear interactions rather than coincidental spectral overlaps.

To further identify the dominant frequencies receiving energy via nonlinear interactions, we computed the summed bicoherence, defined as:

This projection compresses the 2D bicoherence map onto a 1D frequency axis by summing along all frequency pairs\(({f}_{1},{f}_{2})\) that satisfy the resonance condition \(f={f}_{1}+{f}_{2}\). This method highlights output frequency channels most actively involved in nonlinear coupling and is widely used in the study of wave turbulence and plasma instabilities. All computations were performed in MATLAB R2023b.

Measurement of time-averaged frequency spectra and azimuthal mode number

We utilized a radially movable two-tip probe with a tip spacing \({d}_{{tip}}\) of 1.4 mm (each tip has a radius of 0.15 mm and a length of 1.4 mm). The floating voltage \({V}_{f}\) signal from one tip of the two-tip probe was used to obtain the radial profile of the time-averaged frequency spectra. The floating voltage \({V}_{f}\) signal from the two-tip was used to measure the azimuthal mode number. Floating voltages were detected by the two-tip Langmuir probe connected to an oscilloscope via a 1 MΩ resistor. Frequency spectra were obtained using fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) on the complete signals from a floating probe over a duration of 200 ms.

Measurement of oscillating azimuthal electric field and plasma density

The oscillating azimuthal electric field \({\widetilde{E}}_{{field}}\) was measured using a two-tip probe configuration, where the probe tips were aligned in the azimuthal direction. The field calculated as \({E}_{{field}}=({V}_{f,1}-{{V}}_{f,2})/{d}_{{tip}}\), where \({{V}}_{f,1}\) and \({{V}}_{f,2}\) are the floating potentials recorded at the two probe tips separated by \({d}_{{tip}}\) of 1.4 mm.

To capture the temporal evolution of plasma density, the ion saturation current (\({I}_{{isat}}\)) was measured using one of the probe tips biased to −80 V via an isolated battery. The relation \({I}_{{isat}}=0.61{n}_{i}{A}_{{tip}}{u}_{B}\) provides a fundamental diagnostic expression that enables the estimation of ion density from the measured ion saturation current, where \({n}_{i}\) is the ion density, \({A}_{{tip}}\) is the probe tip area, \({u}_{B}\) is the Bohm velocity. This formula is widely used in experimental plasma physics, particularly in low-temperature plasmas, as it directly relates measurable current to plasma parameters under well-defined sheath conditions. It assumes a collisionless sheath, singly charged ions, and Maxwellian electrons, with quasi-neutrality \({n}_{e}\approx {n}_{i}\). These assumptions are valid for our experimental regime, where the mean free path is much larger than the sheath scale, and the probe bias ensures ion saturation. Therefore, the time evolution of the electron density \({n}_{e}(t)\) is inferred using this relation and an electron temperature of 5 eV. In addition, the total discharge current (\({I}_{{dis}}\)) was simultaneously monitored to analyze the onset of BM (Fig. 1 d) and neutral pressure (Fig. 4a).

Due to the mutually exclusive biasing requirements, the \({E}_{{field}}\) and \({I}_{{isat}}\) could not be measured in the same discharge. While \({I}_{{isat}}\) measurements required probe biasing, electric field measurements relied on floating potential detection. As a result, two distinct sets of discharges were used: 57 events for plasma density and pressure analysis, and 74 events for electric field measurements, as indicated in Fig. 4. Despite the separation, each dataset includes a sufficient number of events to enable statistically robust ensemble averaging.

Threshold-based detection of breathing events and ensemble averaging

To extract breathing oscillation (BO) events for ensemble analysis, a detection method was developed based on the spectrogram of the discharge current \({I}_{{dis}}\), which reliably reflects the onset of BO-related light emission collapses. A short-time Fourier transform (STFT) was applied to \({I}_{{dis}}\) to reveal the time-varying power spectrum (Fig.1 d). A threshold detection scheme was then used to identify bursts in the low-frequency range (< 20 kHz), which characterize the onset of breathing behavior. This method is similar to techniques used in fusion plasma diagnostics for identifying bursty instabilities67.

Each detected event was centered around the collapse point and a ± 0.2 ms time window (0.4 ms total) was extracted. Ensemble-averaged profiles of plasma density, pressure, and electric field were computed within this window across 57 and 74 discharges, respectively. This approach improves the signal-to-noise ratio while mitigating the impact of event-to-event variability. The consistency of \({I}_{{dis}}\) amplitude changes ensure minimal alignment error across events, as confirmed by the well-separated spectral bursts shown in Fig. 1 d.

Code availability

No custom code was developed or used specifically for the simulations described in this study.

References

Larson, R. B. Turbulence and star formation in molecular clouds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 194, 809–826 (1981).

White, T. et al. Supersonic plasma turbulence in the laboratory. Nat. Commun. 10, 1758 (2019).

Fiuza, F. et al. Electron acceleration in laboratory-produced turbulent collisionless shocks. Nat. Phys. 16, 916–920 (2020).

Park, S. et al. Stabilization of liquid instabilities with ionized gas jets. Nature 592, 49–53 (2021).

Kirk, A. et al. Evolution of filament structures during edge-localized modes in the MAST tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 185001 (2006).

Yun, G. et al. Two-dimensional visualization of growth and burst of the edge-localized filaments < ? format?> in KSTAR H-mode plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 045004 (2011).

Zuin, M. et al. Kink instability in applied-field magneto-plasma-dynamic thrusters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 225003 (2004).

Brown, Z. A. & Jorns, B. A. Growth and saturation of the electron drift instability in a crossed field plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 115101 (2023).

Tsikata, S. & Minea, T. Modulated electron cyclotron drift instability in a high-power pulsed magnetron discharge. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 185001 (2015).

Hecimovic, A., Schulz-von Der Gathen, V., Böke, M., Von Keudell, A. & Winter, J. Spoke transitions in HiPIMS discharges. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 24, 045005 (2015).

Hatakeyama, R., Moon, C., Tamura, S. & Kaneko, T. Collisionless drift waves ranging from current-driven, shear-modified, and electron-temperature-gradient modes. Contrib. Plasma Phys. 51, 537–545 (2011).

Kaneko, T., Tsunoyama, H. & Hatakeyama, R. Drift-wave instability excited by field-aligned ion flow velocity Shear < ? format?> in the absence of electron current. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 125001 (2003).

Becker, L. E. & Shelley, M. J. Instability of elastic filaments in shear flow yields first-normal-stress differences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 198301 (2001).

Sibillo, V., Pasquariello, G., Simeone, M., Cristini, V. & Guido, S. Drop deformation in microconfined shear flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 054502 (2006).

Muschietti, L., Roth, I., Carlson, C. & Ergun, R. Transverse instability of magnetized electron holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 94 (2000).

Lu, Q., Lembege, B., Tao, J. & Wang, S. Perpendicular electric field in two-dimensional electron phase-holes: A parameter study. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 113, A11219 (2008).

Hasegawa, A. Stimulated modulational instabilities of plasma waves. Phys. Rev. A 1, 1746 (1970).

Claude, C., Latifi, A. & Leon, J. Nonlinear resonant scattering and plasma instability: an integrable model. J. Math. Phys. 32, 3321–3330 (1991).

Hasegawa, A. Plasma instabilities and nonlinear effects. Vol. 8 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Sun, H., Chen, J., Kaganovich, I. D., Khrabrov, A. & Sydorenko, D. Electron modulational instability in the strong turbulent regime for an electron beam propagating in a background plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 125001 (2022).

Lesur, M. et al. Nonlinear excitation of subcritical instabilities in a toroidal plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 015003 (2016).

Mink, A. et al. Nonlinear coupling induced toroidal structure of edge localized modes. Nucl. Fusion 58, 026011 (2017).

Marquès, J.-R. et al. Laser-plasma interaction experiment for solar burst studies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 135001 (2020).

Moon, C., Kaneko, T. & Hatakeyama, R. Dynamics of nonlinear coupling between electron-temperature-gradient mode and drift-wave mode in linear magnetized plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 115001 (2013).

Smolyakov, A. et al. Fluid theory and simulations of instabilities, turbulent transport and coherent structures in partially-magnetized plasmas of e × b discharges. Plasma Phys. Controlled Fusion 59, 014041 (2016).

Frias, W., Smolyakov, A. I., Kaganovich, I. D. & Raitses, Y. Long wavelength gradient drift instability in Hall plasma devices. I. Fluid theory. Phys. Plasmas 19, 1–9 (2012).

Frias, W., Smolyakov, A. I., Kaganovich, I. D. & Raitses, Y. Long wavelength gradient drift instability in Hall plasma devices. II. Applications. Phys. Plasmas 20, 1–14 (2013).

Fridman, A. In Soviet Physics Doklady. 75.

Morin, V. & Smolyakov, A. I. Modification of the Simon-Hoh Instability by the sheath effects in partially magnetized E× B plasmas. Phys. Plasmas 25, 1–5 (2018).

Boeuf, J.-P. & Chaudhury, B. Rotating instability in low-temperature magnetized plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 155005 (2013).

Boeuf, J.-P. & Takahashi, M. Rotating spokes, ionization instability, and electron vortices in partially magnetized E× B plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 185005 (2020).

Koshkarov, O., Smolyakov, A., Raitses, Y. & Kaganovich, I. Self-organization, structures, and anomalous transport in turbulent partially magnetized plasmas with crossed electric and magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 185001 (2019).

Boeuf, J.-P. Spoke formation in low temperature E× B plasmas: Transition from gradient-drift instability to ionization wave. Phys. Plasmas 30, 1–12 (2023).

Simon, A. Instability of a partially ionized plasma in crossed electric and magnetic fields. Phys. fluids 6, 382–388 (1963).

Hoh, F. Instability of Penning-type discharges. Phys. fluids 6, 1184–1191 (1963).

Sakawa, Y. et al. Nonlinear evolution of the modified Simon-Hoh instability via a cascade of sideband instabilities in a weak beam plasma system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 85 (1992).

Sakawa, Y., Joshi, C., Kaw, P., Chen, F. & Jain, V. Excitation of the modified Simon–Hoh instability in an electron beam produced plasma. Phys. Fluids B: Plasma Phys. 5, 1681–1694 (1993).

Carlsson, J. A. et al. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Plasma Sciences (ICOPS). 1-1 (IEEE).

Ellison, C., Raitses, Y. & Fisch, N. J. Cross-field electron transport induced by a rotating spoke in a cylindrical Hall thruster. Phys. Plasmas 19 (2012).

Anders, A. & Yang, Y. Direct observation of spoke evolution in magnetron sputtering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 1–5 (2017).

Hecimovic, A. & Von Keudell, A. Spokes in high power impulse magnetron sputtering plasmas. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 51, 453001 (2018).

Fife, J. et al. In 33rd joint propulsion conference and exhibit. 3052.

Boeuf, J. & Garrigues, L. Low frequency oscillations in a stationary plasma thruster. J. Appl. Phys. 84, 3541–3554 (1998).

Petronio, F., Alvarez Laguna, A., Bourdon, A. & Chabert, P. Study of the breathing mode development in Hall thrusters using hybrid simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 1–22 (2024).

Choueiri, E. Y. Plasma oscillations in Hall thrusters. Phys. Plasmas 8, 1411–1426 (2001).

Hara, K., Sekerak, M. J., Boyd, I. D. & Gallimore, A. D. Mode transition of a Hall thruster discharge plasma. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 1–10 (2014).

Sekerak, M. J., Gallimore, A. D., Brown, D. L., Hofer, R. R. & Polk, J. E. Mode transitions in Hall-effect thrusters induced by variable magnetic field strength. J. Propuls. Power 32, 903–917 (2016).

Young, C., Fabris, A. L., MacDonald-Tenenbaum, N., Hargus, W. & Cappelli, M. Time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence diagnostics for electric propulsion and their application to breathing mode dynamics. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 27, 094004 (2018).

Giannetti, V., Saravia, M. & Andreussi, T. Measurement of the breathing mode oscillations in Hall thruster plasmas with a fast-diving triple Langmuir probe. Phys. Plasmas 27, 1–14 (2020).

Lafleur, T., Chabert, P. & Bourdon, A. The origin of the breathing mode in Hall thrusters and its stabilization. J. Appl. Phys. 130, 1–14 (2021).

Chapurin, O., Smolyakov, A., Hagelaar, G. & Raitses, Y. On the mechanism of ionization oscillations in Hall thrusters. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 1–14 (2021).

Cheon, C., Choi, J., Koo, J. B.-W. & Kim, J. Y. Experimental evidence of various mode numbers of azimuthal waves in an E × B Penning source for semiconductor processing. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 32, 07LT01 (2023).

Lee, M. et al. Azimuthal and axial dispersion relations of low-frequency oscillations in partially magnetized plasma with crossed electric and magnetic fields. Phys. Plasmas 30 (2023).

Minkeun, L., Chung, K.-J., Hara, K. & Kim, J. Y. In APS Annual Gaseous Electronics Meeting Abstracts. IT4. 043.

Kim, J. Y. et al. Magnetic confinement and instability in partially magnetized plasma. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 30, 025011 (2021).

Powis, A. T., Carlsson, J. A., Kaganovich, I. D., Raitses, Y. & Smolyakov, A. Scaling of spoke rotation frequency within a Penning discharge. Phys. Plasmas 25 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5038733 (2018).

Lee, M., Chung, K.-J., Hara, K. & Kim, J. Y. Discharge mode transition in partially magnetized E× B Penning discharge. Phys. Plasmas 31, 1–10 (2024).

Beall, J., Kim, Y. & Powers, E. Estimation of wavenumber and frequency spectra using fixed probe pairs. J. Appl. Phys. 53, 3933–3940 (1982).

Kim, Y. C. & Powers, E. J. Digital bispectral analysis and its applications to nonlinear wave interactions. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 7, 120–131 (1979).

Nagashima, Y. et al. Observation of nonlinear coupling between small-poloidal wave-number potential fluctuations and turbulent potential fluctuations in ohmically heated plasmas < ? format?> in the JFT-2M Tokamak. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 095002 (2005).

Ritz, C. P., Powers, E., Miksad, R. & Solis, R. Nonlinear spectral dynamics of a transitioning flow. Phys. Fluids 31, 3577–3588 (1988).

Kim, J. et al. Measurements of nonlinear energy transfer in turbulence in the tokamak fusion test reactor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 841 (1997).

Schuurman, W. Investigation of a low pressure Penning discharge. Physica 36, 136–160 (1967).

Jeong, W. I. et al. Development of Penning ion gauge for in-situ measurement of neutral pressure in VEST. Fusion Eng. Des. 197, 114034 (2023).

Romadanov, I., Raitses, Y. & Smolyakov, A. Wavelength modulation laser-induced fluorescence for plasma characterization. Rev. Sci. Instruments 95, 1–13 (2024).

Diallo, A. et al. Direct observation of nonlinear coupling between pedestal modes leading to the onset of edge localized modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 235001 (2018).

Kawachi, Y. et al. Fast-sampling fast-ion D-alpha measurement using multi-anode photomultiplier tube in large helical device. Rev. Sci. Instruments 94 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0159175 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00208968, NRF-2019R1A2C2089457, NRF-2021M3F7A1084418).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiment was designed and carried by J.Y.P. and J.Y.K. The data analysis was carried out by J.Y.P. and J.Y.K. The manuscript was written by J.Y.P. and J.Y.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J.Y., Kim, J.Y. Dynamic three-wave coupling between local sporadic spokes and emergence of global breathing oscillation in partially magnetized cross-field plasmas. Commun Phys 8, 380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02304-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02304-w