Abstract

Precise control of near-field coupling is essential for advancing technologies such as antenna arrays, waveguide systems, and optical networks, as well as for studying physical phenomena like mode hybridization and energy transfer. However, achieving exceptional coupling (EC)—defined as effective zero coupling—remains difficult because strong near-field interactions arise at short distances, limiting the ability to suppress crosstalk in integrated systems. Here we show that EC can be realized in a multi-resonator system by introducing a detuned relay resonator that cancels both direct and indirect coupling pathways. This hybrid near-field strategy also enables the formation of a flat band with staggered on-site potentials in periodic structures, offering a route to electromagnetic shielding without relying on conventional blocking materials. Our theoretical analysis and experiments confirm the effectiveness of this method, which is scalable and applicable to integrated antenna and optical waveguide arrays, providing unique opportunities for compact and efficient electromagnetic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the rapidly advancing fields of integrated applications, the miniaturization of devices with stable performance has become a key challenge1. As the size of devices decreases, achieving precisely tunable near-field coupling between resonators becomes essential for minimizing mutual interference and optimizing system performance2,3. Particularly, exceptional coupling (EC)—defined as effective zero coupling—has emerged as a crucial technique for reducing crosstalk in densely integrated systems4, such as antenna arrays5,6, optical networks7,8, and high frequency communication systems9,10. At present, several approaches for EC have been proposed, such as modifying the shape of the crossing region to complex shapes11,12 or introducing auxiliary grating structures13,14. On the other hand, leveraging novel physical concepts and machine learning, researchers have investigated approaches such as inverse design15 and transformation optics16,17 to achieve EC. Notably, anisotropic metamaterials have been shown to enable significant EC by canceling the overlap integral of mode functions in horizontal and vertical directions4. However, while above mentioned several methods for achieving EC, these techniques often encounter significant limitations. For example, traditional approaches such as using photonic bandgap materials or creating artificial dielectric structures to control coupling are constrained by rigid material requirements and geometric configurations, making them impractical for densely packed or miniaturized systems.

Recently, significant progress has been made in the study of non-Hermitian physics, where the introduction of parity-time- (PT-) and anti-PT-symmetry has opened up interest possibilities for controlling coupling between resonators. In particular, researchers have proposed that the anti-PT-symmetry of non-Hermitian systems via indirect channel with imaginary coupling can be achieved by introducing additional detuned delay resonators (DDRs)18,19,20. Essentially, these DDRs effectively modulate the interaction and provide an additional energy exchange channel, which provides a unique non-Hermitian indirect coupling pathway21, enabling precise control over the overall coupling dynamics. This DDR scheme not only enriches the theoretical framework of coupling manipulation but also provides a versatile and tunable mechanism for engineering EC.

In this work, inspired by the DDR coupling scheme associated with non-Hermitian physics18 and the anti-Hermitian hybrid coupling combining the near-field and far-field components22, we propose and demonstrate the EC in multi-resonator systems combining the direct and indirect couplings simultaneously under pure near-field mechanism. Without the loss of generality, we explore the EC in a simple two-resonator coupled system, where an indirect coupling pathway cancels out the direct coupling. Moreover, we extend this approach to multi-resonator systems, where the interplay between different coupling channels leads to unique band structures, including the emergence of flat bands with staggered on-site potentials. These flat bands, characterized by highly localized states23,24, provide a unique platform for exploring and harnessing EC in complex systems. Importantly, to demonstrate the effectiveness of the DDR coupling empowered EC, we conduct principal verification experiments using coupled resonant coils, which serve as a practical realization of the theoretical DDR coupling model. In these experiments, we observe crosstalk suppression and EC at specific operating frequencies, confirming that our method can effectively mitigate coupling between closely spaced resonators. Notably, our approach allows for the crosstalk suppression without the need for complex shielding materials25, providing a more universal and scalable solution for the design of compact electromagnetic (EM) wave functional devices.

Results

Hybrid near-field coupling for achieving exceptional coupling

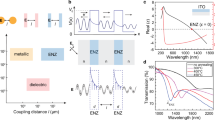

Consider basic direct coupling (\({\kappa }_{0}\)) between two resonators (A and B) under tight-binding mechanism in Fig. 1a, where mode splitting occurs due to energy level repulsion. Here, we propose a hybrid coupling method to eliminate this unnecessary energy exchange in Fig. 1b. Specifically, we introduce an additional indirect coupling channel between two adjacent resonators A and B (angular frequency \({\omega }_{0}\)) via a DDR: resonator C (angular frequency \({\omega }_{{{{\rm{r}}}}}={\omega }_{0}+\Delta\), where \(\Delta\) means the detuning factor), which together with the basic direct coupling channel forms a hybrid coupling system. The coupling between the A (B) and C is \(\kappa\). When the coupling effects of the indirect and direct coupling channels compete and cancel each other out, EC is achieved22, which is equivalent to zero coupling.

a Scheme of conventional direct near-field coupling (\({\kappa }_{0}\)) between two adjacent resonators with same resonance angular frequency (ω0). b Scheme of the hybrid near-field coupling between two adjacent resonators, where in addition to the direct coupling channel (\({\kappa }_{0}\)) between resonators A and B, there is also an indirect coupling channel provided by an additional DDR C (ωr = ω0 + Δ, where \(\Delta\) denotes the frequency detuning factor). The coupling strength between A and C, as well as between B and C, is κ. c The normalized eigenvalues (\(\delta =\omega -{\omega }_{0}\)) spectra of hybrid coupling case with respect to detuning. Blue, green and purple points represent reflectance dips in (d) with Δ = 6, 8, and 10, respectively. d Reflectance spectrum of the hybrid coupling system as a function of \(\omega -{\omega }_{0}\) for different detuning factors: \(\Delta =6\) (left), \(\Delta =8\) (middle), and \(\Delta =10\) (right). The reflection dips corresponding to normalized eigenvalues are marked by the hollow circles. e The eigenvalues (left panel) and the corresponding wavefunctions (right panel) of the splitting modes excited at resonator A, which is marked by the dashed rectangle. The patterns of symmetry of high-frequency ω2 and anti-symmetry of low-frequency ω1 when κ0 are shown by the pink (upper) and blue (lower) arrows, respectively. f Same as (e), but for the case of hybrid coupling. The wave functions of an isolated mode (ω3) and two degenerate modes (ω1 and ω2) are represented in pink, blue, and yellow, respectively. g Resonance amplitudes ratio \(\left|{A}_{i}/{A}_{A}\right|\) (\(i=B,\,C\)) for the EC condition with \(\Delta =8\), which are marked by yellow solid line and purple dashed line, respectively. Exact coordinates of the small peak for the \(\left|{A}_{C}/{A}_{A}\right|\) are labeled as (−1, 0.3).

The hybrid resonance coupled system in Fig. 1b can described by temporal coupled mode theory (CMT) as26:

And the associated dynamic equation can be represented as \({{{\boldsymbol{H}}}}\psi =\omega \psi\), where \(\psi ={\left({a}_{A},{a}_{C},{a}_{B}\right)}^{T}\). Then the effective Hamiltonian be expressed as:

Thus, the corresponding eigenvalue equation of the hybrid system is expressed by \(\left(\delta +{\kappa }_{0}\right)\left[2{\kappa }^{2}+({\kappa }_{0}-\delta )(\delta -\Delta )\right]=0\), where \(\delta =\omega -{\omega }_{0}\). To determine the EC condition, we can resolve Eq. (1) into a second-order form through the method of element transformation (see Supplementary Note 2 for detailed derivation), and the effective dynamic equation is

As a result, the Hamiltonian of the effective second-order system under hybrid coupling can be written as follows

where the \({\kappa }_{{{{\rm{E}}}}}={\kappa }^{2}/(\delta -\Delta )\). According to Eq. (4), we can find that the indirect channel provided by the DDR (i.e., resonator C) not only changes the frequency of the on-site resonators, but also provides an equivalent indirect coupling \({\kappa }_{E}\). Especially, the EC condition corresponds to \({\kappa }_{0}+{\kappa }_{{{{\rm{E}}}}}=0\), thus the eigenvalues of the effective second-order system become \({\omega }_{1}={\omega }_{2}={\omega }_{0}-{\kappa }_{0}\).

By taking \(\kappa =3\) and \({\kappa }_{0}=1\), the relation between normalized eigenvalue (\(\delta =\omega -{\omega }_{0}\)) spectra and \(\Delta\) is illustrated in Fig. 1c. To maintain generality, all parameters here have been normalized to \({\kappa }_{0}=1\). In particular, the intersection point between \({\delta }_{1}\) and \({\delta }_{2}\) implying EC (\(\Delta =8\), \(\delta =-1\)) is also shown in Fig. 1c with green dot. The EC phenomenon can also be verified from the reflectance spectra. Considering the appropriate radiation loss (\(\gamma =0.01\)) in open systems, the reflectance spectra with different \(\Delta\) is illustrated in Fig. 1d, in which the reflectance is consistent with the eigenvalues (i.e., \({\delta }_{1}\) and \({\delta }_{2}\)) in Fig. 1c.

Specifically, for the splitting eigenmode with \({\kappa }_{0} > 0\), the high and low frequencies exhibit symmetric and antisymmetric states, respectively, but the energy intensity of each resonator is equal, which is shown in Fig. 1e. In other words, when the left resonator A is externally excited, the right resonator B will be excited correspondingly, which is a fundamental limitation of strong near-field coupling for densely packed and integrated systems. Considering this EC condition, in addition to above degenerate \({\omega }_{1}\) and \({\omega }_{2}\), the eigenvalues of practical third-order system described by Eq. (1) also have an isolated eigenvalue \({\omega }_{3}={\omega }_{0}+2{\kappa }_{0}+\Delta\). The corresponding wave functions of three eigenvalues under special external excitation is shown in Fig. 1f. More details about the excitation and related dynamic equation are shown in Supplementary Note 1. The EC is clearly presented for the degenerate \({\omega }_{1}\) and \({\omega }_{2}\). It should be emphasized that the coupling manipulation via indirect channel is of high flexibility. Then, we study the EC dependent on the detuning factor \(\Delta\). Moreover, considering the resonator A is subjected to external excitation (marked by the dashed rectangle) under this EC condition, the normalized magnitudes of resonance amplitudes \(\left|{A}_{i}/{A}_{A}\right|\) (\(i=\) B and \(C\)) are shown by solid yellow line and dashed purple line in Fig. 1g, respectively. It can be clearly seen that detuning resonator C has a small amplitude \(\left|{A}_{C}/{A}_{A}\right|=\left|-{\kappa }_{0}/\kappa \right|\approx 0.3\) as soon as possible, but on-site resonator B’s amplitude remains zero \(\left|{A}_{B}/{A}_{A}\right|=0\).

Experimental demonstration of exceptional coupling in resonance coil system

Then, we observe the hybrid near-field enabled EC in an effective second-order coupled resonance-coil system in Fig. 2. Resonance frequency of the coils used in experiment is \({f}_{0}=1.405\) MHz (the distributed inductance and lumped capacitance are \({L}_{0}=\)16 μH and \({C}_{0}=\)0.8 μF, respectively). More details about the experimental setup can be found in Supplementary Note 2. The frequency detuning \(\Delta\) is realized by altering the capacitance (\(C\)) loaded on relay coil C, and the relation can be expressed as \(\Delta ={\omega }_{0}\left(\sqrt{{C}_{0}/C}-1\right)\). In addition, considering the distance between on-site resonators is \({d}_{0}=14.2\) cm, the distance between on-site resonator and detuning resonator is \(d=10.8\) cm, and the diameter of each coil is 19.6 cm, the related CMT parameters are \({\kappa }_{0}/2\pi =16\) kHz, \(\kappa /2\pi =50\) kHz, \(\gamma /2\pi =9.7\) kHz. And considering the inevitable intrinsic losses (i.e., Ohmic loss) in practical systems \(\Gamma /2\pi =7.8\) kHz, the calculated eigenvalues and measured reflectance dips as a function of the lumped capacitor of DDR (resonator C) are illustrated in Fig. 2a with solid and dashed lines, respectively. We can see that two of the measured reflectance dips merge in the vicinity of detuning \(\Delta /2\pi =0.101\) MHz (i.e., \(C=0.7\)μF) at 1.39 MHz. On the other hand, the theoretically calculated detuning and corresponding capacitance for EC are \(\Delta /2{{{\rm{\pi }}}}=0.139\) MHz and \({{{\rm{C}}}}=0.67\) μF, with the EC frequency being 1.389 MHz. Detailed analysis for discrepancies between experimental and theoretical results caused by intrinsic losses are clarified in supplementary material Supplementary Note 3.

a Comparison of the measured (solid lines) reflectance dips and calculated (dashed lines) 3 eigenvalues with varied capacitance \({{{\rm{C}}}}\). Here the red/blue background represents capacitance of DDR is smaller/bigger than theoretically calculated critical capacitance for EC, which is exactly \({{{\rm{C}}}}=0.67\) μF. b Normalized eigenvalue spectra (\({{{\rm{\delta }}}}={{{\rm{\omega }}}}-{{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{0}\)) dependent on \(\kappa\) and \(\varDelta\) with \({\kappa }_{0}/2\pi =16\) kHz. The EC condition is marked by the black curve. Red star represents parameters for realizing EC in experiment. c Measured magnetic field \(\left|H\right|\) intensities of three coils for the hybrid coupling case with \(C=0.67\mu F\). Purple dashed line represents the working frequency of EC: \({f}_{1}=\) 1.39 MHz and \({f}_{2}=1.58\) MHz. d Similar to (c), but for the case of direct coupling without additional DDR.

When \({\kappa }_{0}\) is fixed at \(16\) kHz, EC as a function of \(\kappa\) and \(\Delta\) is shown in Fig. 2b. The EC line is marked by the black line and the experimental parameters corresponds to the red star. Figure 2c shows the measured field intensity at the center of each coil to verify EC. We can see that there are two locals maximum of field intensity. The field intensity in coil A is the largest and the one in coil B is nearly a tenth of field strength in coil A. Especially, the effective wavelength of the working frequency is \({\lambda }_{0}=c/{f}_{0}=214\) m, which is much greater than the coupling distance (\({\lambda }_{0}/{d}_{0}\approx 1528\)). Therefore, we can find that the hybrid near-field combining the direct and indirect channels can well realize the photonic EC. In addition, \({{{{\rm{f}}}}}_{2}=1.576\) MHz, the field intensity in coil C grows larger because this frequency corresponds to \({{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{3}={{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{0}+2{{{{\rm{\kappa }}}}}_{0}+\Delta\). It should be noted that measured non-zero field in coil B is a result of intrinsic loss. The experimental result implies that there is almost no coupling between coil A and coil B although they are placed close enough to each other. In Fig. 2d, measured field intensities of conventional two-coil system without DDR (coil C) are also shown as a comparison. It can be seen that field in coil B is 7/10 of the field in coil A, implying strong coupling in two-coil system, which is consistent with the proposed theoretical model in Fig. 1.

Extension to higher-order coupling systems

Furthermore, hybrid near-field enabled EC has also been demonstrated for the higher-order coupled systems. Considering three on-site resonators (i.e., coils A-C) coupled each other with \({\kappa }_{0}\) and all of them are coupled with a DDR: coil D (coupling strength is \(\kappa\)), as shown in Fig. 3a. Similar to Eqs. (1) and (2), the Hamiltonian of the three on-site resonators coupling system with indirect coupling channel can be written as:

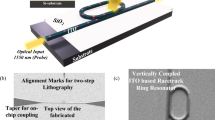

a Scheme of the unique hybrid coupling between three adjacent on-site resonators, where the direct coupling between three on-site resonators (i.e., resonators A-C) is \({\kappa }_{0}\) while the indirect coupling between the DDR (i.e., resonator D) and three on-site resonators is \(\kappa\). b The eigenvalues (left panel) and the corresponding wavefunctions (right panel) of the splitting modes excited at different resonators, which is marked by the dashed rectangle. The wave functions of an isolated mode (\({{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{4}\)) and three degenerate modes (\({{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{1}\), \({\omega }_{2}\) and \({{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{3}\)) are represented from top to bottom, respectively. c Photograph of the experimental setup, where the distances are \({d}_{0}=14.2\) cm and \(d=8.2\) cm. The diameter of the coil resonator is 19.6 cm. d Calculated magnetic field \(\left|H\right|\) intensities when the resonance coil A is excited. e, f Experimental measured magnetic field \(\left|H\right|\) intensities when the resonance coils A and B are excited, respectively. The working frequency for the EC is 1.61 MHz, which is marked by the black dashed line.

For the EC condition, the four eigenvalues are found to be \({\omega }_{1}={\omega }_{2}={\omega }_{3}={\omega }_{0}-{\kappa }_{0}\) and \({\omega }_{4}={\omega }_{0}+3{\kappa }_{0}+\Delta\). According to the analysis above and the symmetry of the system, the eigenvectors of the degenerate eigenvalues under single excitation can be

Figure 3b presents that when system is working at \({{{\rm{\omega }}}}={{{{\rm{\omega }}}}}_{0}-{{{{\rm{\kappa }}}}}_{0}\), the total coupling among on-site resonators A, B and C is always zero. The EC in the effective third-order coupled system is verified by experiments based on a multi-coil system shown in Fig. 3c. Here, resonance frequency of the coils used in experiment is \({f}_{0}=1.632\) MHz (the corresponding wavelength is \({\lambda }_{0}=184\) m). Here, DDR (coil D) is placed at the center of the equilateral triangle composed of resonance on-site coils A, B and C. The distance between resonance coils and the distance between detuning coil and resonance coil are \({d}_{0}=14.2\) cm and \(d=8.2\) cm, which correspond to the coupling strength \({\kappa }_{0}/2\pi =18\) kHz and \(\kappa /2\pi =56\) kHz, respectively. Here, the deep subwavelength under near-field is also defined as \({\lambda }_{0}/{d}_{0}\approx 1296\). The frequency detuning \(\Delta /2\pi =0.156\) MHz is realized by altering the capacitance loaded on DDR (coil D). Especially, the proper capacitance \(C=333\) pF satisfied the EC condition. Same as three-coil system in Fig. 2, the field intensity in each coil is also measured by a homemade probing coil placed at the center of coil. Take coil A (externally excited) as an example, the calculated and measured normalized magnetic field \(\left|H\right|\) distributions are shown in Fig. 3d, e, respectively. Moreover, for clear comparison, the normalized field with coil B excited is also presented in Fig. 3f. At EC frequency \(f=({\omega }_{0}-{\kappa }_{0})/2\pi\), most of the energy remains in the excited coil, with a small fraction (\(\left|{H}_{{{{\rm{D}}}}}/{H}_{{{{\rm{excited\; coil}}}}}\right|\approx 0.27\)) transferred to DDR (coil D). Field intensity in the other two resonance coils is always 1/10 of the one in the excited coil, implying that coupling among these three on-site coils is greatly suppressed. Experimental results are consistent with theoretical analysis based on CMT. It should be pointed out that the hybrid near-field framework of combining the direct and indirect coupling channels with detuning resonator for realizing EC is a universal method which can be fulfilled in various resonance systems. Besides multi-coil systems, EC is also numerically demonstrated in optical multi-dielectric- antenna system, see the details in the Supplementary Notes 4 and 5.

Exceptional coupling associated flat band phenomena in periodic structures

At last, we study the flat band stemming from EC in periodic systems with staggered on-site potentials. A periodic chain composed of on-site resonator A and DDR B is shown in Fig. 4a. As a result, the structure corresponds to a photonic chain with interlaced angular frequency (or potential) \({\omega }_{0}\) and \({\omega }_{0}+\Delta\). Same as above definition, the intra-coupling between resonator A and B in one unit cell is defined as \(\kappa\), while the inter-coupling between resonator A in two adjacent unit cells is \({\kappa }_{0}\). With the introduction of Bloch theorem, the field at site A and B can be expressed as \({a}_{n}=A{e}^{i(n\varphi +\omega t)}\) and \({b}_{n}=B{e}^{i(n\varphi +\omega t)}\). Here \(\varphi \in \left[-\pi ,\pi \right]\) is the Bloch phase from the first Brillouin zone. The dynamic equations for two sites A and B can be expressed as:

a Schematic of periodic chain composed of on-site resonator A (\({\omega }_{0}\)) and detuning coupled resonator B (\({\omega }_{r}\)). b Experimental design of ring-like coupled resonance system with four on-site resonators (i.e., resonators A, C, E, and G) and four detuning coupled resonators (i.e., resonators B, D, F, and H). c The corresponding band structure of the ring-like system for different coupling strength: \(\kappa /2\pi =18\) kHz (\(\kappa < {\kappa }_{c}\)), 46 kHz (\(\kappa ={\kappa }_{c}\)), 60 kHz (\(\kappa > {\kappa }_{c}\)), which are marked by blue, black and red lines, respectively. d Measured DOS of system with \(\kappa /2\pi =18\) kHz (blue), 46 (black), and 60 (red). Red and blue area represents band in (c), and they overlap from 1.618 MHz to 1.628 MHz. e Measured field intensity of coils in ring-like system with coil A excited. Solid lines and dotted lines represent site A and site B separately. The green dashed line represents flat band with \(f=1.454\) MHz.

The dispersion relationship between \(\varphi\) and \(\omega\) can be decided by the eigenvalue equation

Therefore, the flat band condition at \(\omega ={\omega }_{0}-2{\kappa }_{0}\) can be determined as

Here, \({\kappa }_{E}={\kappa }^{2}/({\delta }_{E}-\Delta )\) implying the indirect coupling channel is same as the condition given by Eq. (4) for the effective second-order system, but \({\delta }_{E}=-2{\kappa }_{0}\). In the experiment, we construct an equivalent ring-like structure with periodic potential regulation using four on-site resonators (i.e., A, C, E, and G, whose resonance frequency is \({f}_{0}=\)1.478 MHz) and four DDRs (i.e., B, D, F, and H, whose resonance frequency is \({f}_{0}+\Delta /2\pi =\)1.628 MHz) with the help of periodic boundary conditions, as shown in Fig. 4b. Here, the two coupling coefficients are selected as \({\kappa }_{0}/2\pi =12\) kHz, \(\kappa /2\pi =46\) kHz, respectively. The band structure of the ring-like structure is shown in Fig. 4c. For the critical EC condition \(\kappa /2\pi =46\,{{{\rm{kHz}}}}\) (\(\kappa ={\kappa }_{c}\)), the flat band occurs at frequency \(f={f}_{0}-{\kappa }_{0}/\pi =1.454\) MHz, which is shown by the black lines. For comparison, considering the coupling deviating from the flat band condition (i.e, \(\kappa\, \ne \,{\kappa }_{c}\)), two types of dispersion with opposite slope are shown by the blue and red lines for \(\kappa /2\pi =18{{{\rm{MHz}}}}(\kappa < {\kappa }_{c})\) and \(\kappa /2\pi =60{{{\rm{MHz}}}}(\kappa > {\kappa }_{c})\) in Fig. 4c, respectively. The corresponding density of states (DOS) spectra are measured in Fig. 4d27 (Experimental details can be found in the Supplementary Note 6). We can see red shift of lower band and blue shift of upper band for \(\kappa < {\kappa }_{c}\), along with blue shift of lower band and red shift of upper band for \(\kappa > {\kappa }_{c}\). This EC enabled flat band and the related localization phenomenon is also be well demonstrated from the measured field intensity of coils when the coil A is excited, as shown in Fig. 4f. The measured results are agreed well with the theoretical ones.

Conclusion

As a summary, we present a unique scheme leveraging DDRs to construct multiple coupling pathways, enabling EC between closely spaced resonators at specific operating frequencies. This approach demonstrates the effective cancellation of both direct and indirect coupling channels under hybrid near-field interactions, providing a robust framework for achieving EC. Importantly, our theoretical model is scalable and can be extended to higher-order systems, offering broad applicability across various resonator configurations. Beyond the demonstrated resonance coil networks, the general applicability of the proposed EC mechanism makes it a versatile strategy across diverse physical systems, including artificial structures with long-range interactions28,29, and on-chip integrated photonics platforms30,31,32. The core principle—precise balancing of hybrid coupling channels—is inherently platform-independent and can be engineered through system-specific detuning or geometry modifications.

Additionally, we experimentally observe the formation of a flat band with staggered on-site potentials, directly linked to the realization of EC. This phenomenon highlights the potential of EC-enabled flat bands in facilitating the localization of EM waves and mitigating crosstalk in densely integrated systems. The proposed method not only eliminates the need for traditional EM wave blocking materials but also introduces a versatile and scalable strategy for controlling near-field coupling. This advancement holds significant promise for applications in compact waveguide systems, antenna arrays, and other EM devices, particularly in scenarios requiring precise coupling manipulation within confined spaces.

Methods

Experimental setup and details of measurement

The experimental setup consists of magnetically coupled resonant coils, which were constructed using 2 mm diameter Litz wire. Litz wire was chosen for its ability to reduce skin effect losses at high frequencies, ensuring efficient near-field coupling within the coils. Each on-site resonance coil is loaded with a capacitance \({C}_{0}=400{{{\rm{pF}}}}\), which determines the resonant frequency of the system. The detuning of the system, which represents the shift from resonance due to variations in capacitance, can be quantitatively described by the equation:

where \({f}_{0}\) is the resonant frequency of the unloaded coil, and \(C\) represents the capacitance that varies during the experiment, which leads to detuning. This relationship captures how variations in capacitance alter the system’s resonance and frequency response. The coupling between the two coils is characterized by their mutual inductance, which is determined solely by the physical distance between them, independent of the detuning of each individual coil. This design allows the coupling strength to be controlled by positioning the coils relative to one another, providing a consistent measure of coupling across different experimental setups. To facilitate the measurement process, a non-resonant coil is placed above one of the resonant coils. This non-resonant coil serves as the source coil and is connected to port 1 of the vector network analyzer (VNA, Keysight E5071C), which is used for the measurement of the system’s scattering parameters. The VNA provides high precision and allows for the characterization of frequency-dependent behaviors such as scattering loss and resonance shifts. The introduced scattering loss in the system is measured and quantified by the VNA, with a determined loss value of \({\gamma }_{1}/2\pi =5{{{\rm{kHz}}}}\). This loss value represents the energy dissipated or absorbed due to imperfections or intrinsic resistance in the coils and surrounding environment.

For further analysis, the local DOS spectrum is used to explore the EM field distribution within the ring-like system. The local DOS spectrum is obtained by placing a probe at the center of the resonance coil to measure the reflected signal33,34. The probe, connected to the VNA, captures the reflection coefficients from the system. These reflections are then averaged over all sites to generate the DOS spectrum, which provides insights into the energy distribution across the system. The averaging process accounts for any spatial variations in the field strength, ensuring that the DOS spectrum reflects the overall behavior of the coupled system. This setup enables the study of resonant coupling, detuning effects, and the distribution of EM energy within the coupled resonator system, with applications ranging from wireless communication systems35 to sensing36,37 and power transfer38,39,40.

Data availability

All the data necessary for reproducing our results are publicly available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29978251.

Code availability

All the codes that support the findings of this study are available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29978779.

References

Ullah, M. A. et al. A review on antenna technologies for ambient RF energy harvesting and wireless power transfer: Designs, challenges and applications. IEEE Access 10, 17231–17267 (2022).

DeVault, C. T. et al. Suppression of near-field coupling in plasmonic antennas on epsilon-near-zero substrates. Optica 5, 1557–1563 (2018).

Lalbakhsh, A., Afzal, M. U., Esselle, K. P. & Smith, S. L. Wideband near-field correction of a Fabry–Pérot resonator antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 67, 1975–1980 (2019).

Mia, M. B. et al. Exceptional coupling in photonic anisotropic metamaterials for extremely low waveguide crosstalk. Optica 7, 881–887 (2020).

Palanisamy, S. et al. A novel approach of design and analysis of a hexagonal fractal antenna array (HFAA) for next-generation wireless communication. Energies 14, 6204 (2021).

Wang, X., Aboutanios, E., Trinkle, M. & Amin, G. Reconfigurable adaptive array beamforming by antenna selection. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 62, 2385–2396 (2014).

Vlasov, Y., Green, W. M. J. & Xia, F. High-throughput silicon nanophotonic wavelength-insensitive switch for on-chip optical networks. Nat. Photon. 2, 242–246 (2008).

Xue, Z. et al. Integrated photonic networks for efficient communication. Nature 632, 280–286 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. High-speed 0.22 THz communication system with 84 Gbps for real-time uncompressed 8K video transmission of live events. Nat. Commun. 15, 8037 (2024).

He, X., Wang, R., Wu, J. & Li, W. Nature of power electronics and integration of power conversion with communication for talkative power. Nat. Commun. 11, 2479 (2020).

Bogaerts, W., Dumon, P., Thourhout, D. V. & Baets, R. Low-loss, low-exceptional coupling crossings for silicon-on-insulator nanophotonic waveguides. Opt. Lett. 32, 2801–2803 (2007).

Sanchis, P. et al. Highly efficient crossing structure for silicon-on-insulator waveguides. Opt. Lett. 34, 2760–2762 (2009).

Bock, P. J. et al. Subwavelength grating crossings for silicon wire waveguides. Opt. Express 18, 16146–16155 (2010).

Song, W. et al. High-density waveguide superlattices with low crosstalk. Nat. Commun. 6, 7027 (2015).

Shen, B., Polson, R. & Menon, R. Metamaterial-waveguide bends with effective bend radius λ₀/2. Opt. Lett. 40, 5750–5753 (2015).

Gabrielli, L. H., Liu, D., Johnson, S. G. & Lipson, M. On-chip transformation optics for multimode waveguide bends. Nat. Commun. 3, 1217 (2012).

Shen, B., Polson, R. & Menon, R. Increasing the density of passive photonic-integrated circuits via nanophotonic cloaking. Nat. Commun. 7, 13126 (2016).

Yang, F., Liu, Y. C. & You, L. Anti-PT symmetry in dissipatively coupled optical systems. Phys. Rev. A 96, 053845 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Dynamically encircling an exceptional point in anti-parity-time symmetric systems: asymmetric mode switching for symmetry-broken modes. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 88 (2019).

Ke, S. et al. Topological bound modes in anti-PT-symmetric optical waveguide arrays. Opt. Express 27, 13858 (2019).

Keil, R. et al. Universal sign control of coupling in tight-binding lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 213901 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. Anti-Hermitian plasmon coupling of an array of gold thin-film antennas for controlling light at the nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 193902 (2012).

Leykam, D., Flach, S. & Chong, Y. D. Flat bands in lattices with non-Hermitian coupling. Phys. Rev. B 96, 064305 (2017).

Leykam, D. & Flach, S. Perspective: photonic flatbands. APL Photon 3, 070901 (2018).

Chen, X., Guo, Z., Jiang, J., Jiang, H. & Chen, H. Ultra-broadband near-field magnetic shielding realized by the Halbach-like structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 192201 (2022).

Sun, Y., Tan, W., Li, H. Q., Li, J. & Chen, H. Experimental demonstration of a coherent perfect absorber with PT phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 143903 (2014).

Poli, C., Bellec, M., Kuhl, U., Mortessagne, F. & Schomerus, H. Selective enhancement of topologically induced interface states in a dielectric resonator chain. Nat. Commun. 6, 6710 (2015).

Li, M. et al. Higher-order topological states in photonic kagome crystals with long-range interactions. Nat. Photon. 14, 89–94 (2020).

Guo, Z., Jiang, H., Li, Y., Chen, H. & Agarwal, G. S. Enhancement of electromagnetically induced transparency in metamaterials using long range coupling mediated by a hyperbolic material. Opt. Express 26, 627–641 (2018).

Song, W. et al. Fast topological pumps via quantum metric engineering on photonic chips. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn5028 (2024).

Song, W. et al. Shortcuts to adiabatic non-Abelian braiding on silicon photonic chips. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt7224 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Topological singularities and edge-state coupling enable robust on-chip slow light. Adv. Sci 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202507226 (2025).

Jiang, J. et al. Seeing topological winding number and band inversion in photonic dimer chain of split-ring resonators. Phys. Rev. B 101, 165427 (2020).

Guo, Z. et al. 1D photonic topological insulators composed of split ring resonators: a mini review. Adv. Phys. Res. 3, 2300125 (2024).

Olenik, S., Lee, H. S. & Güder, F. The future of near-field communication-based wireless sensing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 286–288 (2021).

Guo, Z., Zhang, T., Song, J., Jiang, H. & Chen, H. Sensitivity of topological edge states in a non-Hermitian dimer chain. Photon. Res. 9, 574–582 (2021).

Lin, R. et al. Wireless battery-free body sensor networks using near-field-enabled clothing. Nat. Commun. 11, 444 (2020).

Assawaworrarit, S., Yu, X. F. & Fan, S. H. Robust wireless power transfer using a nonlinear parity–time-symmetric circuit. Nature 546, 387 (2017).

Guo, Z. et al. Level pinning of anti-PT-symmetric circuits for efficient wireless power transfer. Natl. Sci. Rev. 11, nwad172 (2024).

Song, M. et al. Wireless power transfer based on novel physical concepts. Nat. Electron. 4, 707–716 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2021YFA1400602 and 2023YFA1407600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 12474316, 12274325, and 12374294), and the Chenguang Program of Shanghai (No. 21CGA22).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. G., H. J., H. C. and Y. S. conceived the idea, supervised the project, and wrote the manuscript. J. Z. proposed the model, performed the numerical simulations and theoretical analyses. J. Z. and Y. W. prepared the sample and conducted experimental measurements. All authors contributed to discussions of the results and the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Wange Song, Shota Kita and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Wang, Y., Guo, Z. et al. Exceptional coupling via multiple channels for crosstalk suppression and flat band with staggered on-site potentials. Commun Phys 8, 402 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02313-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02313-9