Abstract

The Josephson diode effect describes the property of a Josephson junction to have different values of the critical current for different directions of applied bias current and it is the focus of intense research thanks to the potential technological applications. The ubiquity of the experimentally reported phenomenology calls for a study of the impact that disorder can have in the appearance of the effect. We study the Fraunhofer pattern of planar Josephson junctions in presence of different kinds of disorder and imperfections and we find that a junction that is mirror symmetric at zero-field forbids the diode effect and that the diode effect is typically magnified at the nodal points of the Fraunhofer pattern. The work presents a comprehensive treatment of the role of pure spatial inhomogeneity in the emergence of a diode effect in planar junctions, with an extension to the multi-terminal case and to systems of Josephson junctions connected in parallel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-reciprocal effects in superconductors manifest with the magnitude of the critical current acquiring a dependence on the direction of the applied current. Such a feature results in the so-called Superconducting Diode Effect (SDE), and ultimately yields supercurrent rectification. Motivated both by fundamental questions about the underlying generating mechanisms and by potential technological applications in dissipationless nanoelectronics1, a large amount of scientific work has recently focused on the diode effect2,3,4,5,6,7. The latter has been observed in the critical current of two classes of systems: i) in bulk materials, where it is a thermodynamic property of the superconducting state, in which case the term SDE is more appropriate, and ii) in Josephson junctions, where the switching to a dissipative state involves mostly the junction and the bulky terminals maintain their superconducting properties. In this case, we refer to the Josephson Diode Effect (JDE).

Nonreciprocal critical supercurrents have been measured in noncentrosymmetric systems with Rashba spin-orbit coupling and in-plane magnetic field2,8,9, in the fluctuation state of polar superconductors10, in nanopatterned devices11, non-centrosymmetric superconductor/ferromagnet multilayers12, and in trilayer twisted graphene in zero magnetic fields, where it points to a time-reversal symmetry breaking state13. SDE has been proposed and measured for finite-momentum Cooper pairs13,14,15,16, and it has been measured in twisted high Tc superconductors junctions17,18.

In Josephson systems, JDE has been proposed and measured in a number of different devices, such as junctions with conventional superconductors and central regions with spin-orbit interactions3,6,19, Dayem bridges20,21,22, and interferometric setups featuring a high-harmonic content23,24. JDE has been observed in junctions hosting screening currents25,26, self-field effects induced by supercurrents27,28, and phase reconfiguration induced by Josephson current and kinetic inductance29. It has also been observed in multi-terminal devices30,31 gate-tunable junctions30,32, and through the back-action mechanism33,34.

It is widely accepted that the crucial conditions for the emergence of the diode effect are time-reversal and spatial-inversion symmetry breaking, together with high transparency in Josephson junction realizations. However, whether inversion and time-reversal symmetries are broken in a global intrinsic way or at a local extrinsic level and how this impacts the experimental phenomenology remains unclear. In particular, the role of disorder in the junction, either via short-range impurities, or through geometric asymmetries and applied gate voltages, is not yet evident. Within this context, an analysis of the symmetries and their impact on the diode effect motivates the present work, especially concerning the role of spatially dependent phase patterns in determining a reciprocity symmetry breaking. To this end, interferometry is a powerful investigation tool.

In this work, we investigate the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern in planar Josephson junctions focusing on the role of spatial inhomogeneity in the emergence of a diode effect at finite flux. In a planar Josephson junction, schematically shown in Fig. 1a, two superconducting terminals are coupled via a central normal region threaded by a magnetic flux that acts as a diffraction center for Cooper pairs. In traversing the junction in the direction of the phase bias φ, Cooper pairs acquire a phase that spatially depends on the transverse direction,

with Φ(x) the flux of the field through the area to the left of x and Φ0 = h/2e the quantum superconducting flux, which yields the typical interferometric pattern in the critical current. It becomes clear that such a device is susceptible to spatial inhomogeneity, which locally affects the phase acquired by the Cooper pairs and the resulting interferometric pattern. As one of the most important results, we find that, in junctions that in absence of magnetic field are symmetric under a specific mirror symmetry, a JDE can be ruled out. In turn, in all the devices considered in which the relevant mirror symmetry is broken a JDE always occurs.

By means of the rectification coefficient as a figure of merit, we analyze the Fraunhofer pattern of different specific configurations that break mirror symmetry, such as smoothly varying profiles, structures with short-range disorder, and geometrically asymmetric devices. We report qualitatively similar results, with spikes in correspondence of the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern, where JDE is magnified due to destructive interference, that suppresses the current in one direction more than in the opposite direction. A statistical analysis of the rectification coefficient in disordered systems shows a common trend of its root mean square, that can be ascribed to mesoscopic critical current fluctuations and that suggests further investigation. The analysis is extended to arrays of Josephson junctions connected in parallel and to multiterminal junctions, where the phase at different terminals can be used as a knob to modulate the Fraunhofer pattern and tune the diode effect at finite magnetic flux, thus extending the results on multiterminal JDE30,31,35 to the case of the Fraunhofer interference pattern.

The present work offers a comprehensive analysis of the role of mirror symmetry and of disorder in the emergence of the Josephson diode effect in realistic devices.

Results

The Josephson diode effect in a junction is studied by assessing the equilibrium current I(φ) as a function of phase bias φ. The latter can be expressed using the free energy of the system F(φ) at temperature T as I(φ) = (2π/Φ0)∂F(φ)/∂φ36. The critical currents for positive- and negative-bias currents are defined as

and a JDE occurs when \({I}_{c}^{+}\ne | {I}_{c}^{-}|\). The efficiency of the diode effect is quantified by the rectification coefficient

We are interested in the dependence of the critical currents on the external flux Φ produced by an orbital magnetic field that threads the junction. From the Onsager reciprocity relations, it follows that, in general, we have \({I}_{c}^{+}(\Phi )=-{I}_{c}^{-}(-\Phi )\). In particular, we now demonstrate that for a system that is mirror-symmetric in zero field we have \({I}_{c}^{+}(\Phi )=-{I}_{c}^{-}(\Phi )\).

Absence of JDE in mirror-symmetric junctions

We formalize this concept by focusing on the role of spatial mirror symmetry in the junction using a scattering matrix approach37,38,39,40. The latter is particularly suited to study mesoscopic coherent systems, allowing us to make general statements, independently of the particular realization. By knowing the scattering matrix s(ϵ) describing the central normal region and assuming its dependence on energy ϵ can be neglected on the scale of the gap Δ, we can obtain the Andreev spectrum by the singular values of the complex matrix40 (Supplementary Material: Sec. I - Scattering Matrix Formulation)

with \({r}_{A}={{{\rm{diag}}}}({e}^{-i\varphi /2}{{\mathbb{1}}}_{L},{e}^{i\varphi /2}{{\mathbb{1}}}_{R})\) and \({{\mathbb{1}}}_{L(R)}\) are identity matrices with the dimension of the number of open transport channels in the L(R) lead.

We consider a specific mirror symmetry of the junction. With reference to Fig. 1a, this is given by Mx, such that \({M}_{x}x{M}_{x}^{-1}=-x\). For a general scattering matrix s that is mirror-symmetric in the absence of the external field, we can write

with Φ the total flux through the junction. Furthermore, by the Onsager reciprocity relations we know that sT(Φ) = s(−Φ), from which it follows that the matrix A transforms under mirror Mx as

This results from the fact that the phase difference φ is unaltered by the mirror symmetry Mx. Since the singular values of A give the Andreev spectrum, a similarity between A(φ, Φ) and A( − φ, Φ) guarantees that the free energy satisfies F(φ, Φ) = F( − φ, Φ), from which it follows that the current satisfies

and from the Onsager reciprocity relations a diode effect cannot occur. Without zero-field mirror symmetry, a diode effect cannot be ruled out, and its features depend on the system microscopic or macroscopic spatial details.

It is crucial to appreciate how other choices of zero-field mirror symmetry cannot yield conclusive statements about the absence of JDE. For example, for a system whose scattering matrix satisfies \({M}_{y}s(\Phi ){M}_{y}^{-1}=s(-\Phi )\), we obtain \({M}_{y}A(\varphi ,\Phi ){M}_{y}^{-1}={r}_{A}^{* }A(\varphi ,\Phi ){r}_{A}^{* }\), so that we cannot conclude anything regarding the presence or absence of JDE. Furthermore, it is interesting to consider the inversion symmetry, or parity, \(\hat{P}\), which maps r → − r. Inversion symmetry can be decomposed as the product of three orthogonal mirror symmetries, \(\hat{P}={M}_{x}{M}_{y}{M}_{z}\). Assuming that My is broken implies breaking of the inversion symmetry. At the same time, a zero-field mirror symmetry about Mx rules out the JDE, showing that, generally, inversion symmetry breaking is only a necessary condition.

Introducing n as the vector normal to the plane defining a given mirror transformation Mn, we have that JDE appears when the system breaks the mirror for which n is parallel to the cross product between the applied external field B and the direction of the current bias j yielding the junction phase difference φ,

already in absence of the magnetic field. With reference to Fig. 1a, we have \({{{\bf{n}}}}=\hat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}\). This result is general and, in particular, it can be extended to the case of SDE and JDE in systems with Rashba spin-orbit interaction and in-plane Zeeman field3,6,7: in that case the magnetic field is in the plane of the junction, orthogonal to the current bias, and the Rashba spin-orbit term appears due to the breaking of the mirror symmetry about the plane of the junction. We point out that a magnetic field alone is a source of mirror symmetry breaking for any mirror plane containing the field, as can be seen by choosing a gauge for the vector potential A(r) = (0, Bx, 0). At the same time, if the magnetic field is the only source of mirror symmetry breaking and the field is uniform, the junction spatial symmetry dictates how the scattering matrix transforms under mirror symmetry.

Although a symmetry analysis cannot guarantee the onset of JDE, an important point is that junctions that at zero-field break the Mx symmetry always show JDE. In the next sections, an analysis of several different kinds of structures that break the mirror symmetry Mx in the zero field will corroborate such a statement.

Planar Josephson junctions

Wide Josephson junctions comprise an extended normal central region connected to two wide superconducting leads, schematically depicted in Fig. 1a. Here, we focus on two-terminal planar systems and consider three instances of spatial inhomogeneity: i) a geometrically inversion symmetric ballistic junction with a spatial potential in the central area that varies on a long length scale, on order of the junction lateral sizes, ii) a clean ballistic system with a trapezoidal geometric shape, iii) a geometrically inversion symmetric, ballistic junction with a spatially varying potential that varies on a short length scale, on order of the interatomic distances. The case i) is compatible with the charge profile induced by the back and side gates, and the case iii) is compatible with local disorder.

We model the central region using a generic tight-binding model on a square lattice, as the one schematized in Fig. 2f of the main text, described by the Hamiltonian

where ciσ describes electrons with spin σ = ↑, ↓ at position ri, and the index i runs over all the lattice points of the central region. The square lattice has a sublattice symmetry that yields a particle-hole symmetry in the spectrum. Electrons have onsite energy Ui = 4t − μ + δUi, comprising a chemical potential contribution μ and an additional onsite potential δUi ≡ δU(ri), and can hop among nearest-neighboring sites with amplitude \(-t{e}^{i{\theta }_{i,j}}\), where the Peierls phase \({\theta }_{i,j}=\frac{e}{\hslash }\int_{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}}^{{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{j}}{{{\bf{A}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\cdot d{{{\bf{s}}}}\) is due to the external magnetic field B = ∇ × A. The central region is attached to the superconducting leads, and potential barriers that shift local energy are added to the contact interface. We consider transport at zero energy in the limit in which the energy dependence of the scattering matrix can be neglected, which corresponds to a system length L < ξ, with ξ the coherence length of the superconducting leads, and numerically simulate several systems employing the KWANT package41 (Supplementary Material: Sec. II–Comparison with realistic systems).

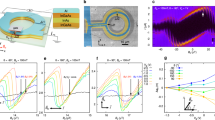

The junction is schematically depicted in (f), in which two superconducting terminals kept at phase different φ are contacted to a normal region of width W, length L, and pierced by a magnetic field B that induces a flux Φ = BA, with A = WL the area of the central normal region. a Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ resulting from the local onsite potential \(\delta {U}_{i}={V}_{g}(\tanh (({x}_{i}-W/2)/{W}_{c})+1)/2\), for Vg = 0.1 t, μ = 0.3 t, and Wc = 20 a, shown in the top-left of the figure. b Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (a). c Dependence of the rectification coefficient η of b on the gate potential Vg, for different values of Vg. d Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ resulting from the local onsite potential \(\delta {U}_{i}=V(\tanh (({y}_{i}-L/2)/{W}_{c})+1)/2\), shown in the top-right of the figure. e Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (d). The residual value arises due to the discretization of the grid. f Schematics of the wide Josephson junction and square lattice of lateral dimensions W = 100 a and L = 20 a, in terms of a microscopic unit length a, employed in the tight-binding model to calculate the scattering matrix. Semi-infinite leads are attached to the scattering region’s top and bottom. A potential barrier of strength Upot = 0.2 t is added at the interface with the leads.

As a general trend, we find that when the zero-field mirror symmetry of the junction is broken, a JDE appears, which is highly enhanced at the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern, where the critical currents do not go to zero simultaneously.

Smooth potentials

We first consider a central rectangular region of width W = 100 a and length L = 20 a, in terms of a microscopic discretization length a, schematized in Fig. 2f. We set the chemical potential at μ = 0.3 t in both the central region and in the leads and apply a non-uniform potential \(\delta U(x,y)={V}_{g}(\tanh ((x-W/2)/{L}_{s})+1)/2\). The potential, which also comprises a shift of the chemical potential, is not symmetric under Mx, such that \({M}_{x}\delta U(x,y){M}_{x}^{-1}\ne \delta U(-x,y)\), and it is shown in the upper right inset of Fig. 2a for a value of Vg = 0.1 t, producing a smooth profile that changes on a length Ls = 20 a. Potential barriers, that shift the local energy by 0.2 t, are added at the interface with the contacts. In Fig. 2a, we show the associated Fraunhofer interference pattern for the critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\). We see that the presence of a smooth potential breaking the mirror symmetry Mx produces a diode effect, as quantified by the rectification coefficient η shown in Fig. 2b, reaching rectification 30%.

The fact that a smooth, long-wavelength potential can yield a diode effect suggests that the latter can be tuned by applying a gate. The potential shown in the inset of Fig. 2a well approximates the one produced by a back gate that occupies the right side of the junction. In Fig. 2c, we plot the rectification efficiency for few values of the gate potential, Vg/t = 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08. In the first lobe, we clearly see a trend for which the rectification increases with the gate potential. In turn, we see no clear systematic evolution of the curves for increasing gate strength. The rectifications show spikes in correspondence with the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern, which are due to destructive interference acting in different ways for trajectories that go from one lead to the other and vice versa.

We then consider a potential that is even under Mx but that is not symmetric under My, thus breaking the inversion symmetry \(\hat{P}\). Specifically, we choose \(\delta U(x,y)=V\tanh ((y-L/2)/{L}_{s})\). The potential satisfies \({M}_{x}\delta U(x,y){M}_{x}^{-1}=\delta U(-x,y)\), \({M}_{y}\delta U(x,y){M}_{y}^{-1}\ne \delta U(x,-y)\), and it is shown in the top-right inset of Fig. 2d for a value of Vg = 0.1 t, yielding a smooth profile that changes on a length Ls = 20 a. As clearly shown in Fig. 2d, the two curves \({I}_{c}^{\pm }(\Phi )\) cannot be distinguished and the rectification coefficients are less than 0.4%, as shown in Fig. 2e. This result is significant, as it corroborates the finding that breaking of inversion symmetry cannot guarantee a JDE and that the presence of a symmetric profile under Mx guarantees no JDE.

Geometric asymmetry

In Fig. 3, we consider the case ii) of a clean system with a trapezoidal shape. We consider two possible cases, one in which the distance between the two leads varies with the lateral position, shown in the upper left panel of Fig. 3a, and one in which the size of the leads is different, shown in the upper right panel in Fig. 3c. We see that the shape of the central region is sufficient to break the Mx mirror symmetry of the junction, producing a diode effect, as quantified by the rectification coefficient η shown in Fig. 3b, d, reaching up to 40%. In Fig. 3a, we see that the position-dependent distance between the leads for the entire structure yields a phase average that suppresses destructive interference. In contrast, in Fig. 3c, the phase averaging arises from additional trajectories on the system’s right side. In the present case, the system is fully ballistic and coherent, and the averaging effect is solely due to the geometry that introduces paths with different lengths that add up to build the interference pattern.

a Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ for the trapezoidal junction shown in the top-right inset, with width W = 100 a and left and right lengths Ll = 25 a, Lr = 15 a. b Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (a). c Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ for the trapezoidal junction shown in the top-right inset, with bottom and top width Wb = 120 a, Wt = 80 a, and length L = 20 a. d Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (c). For all panels, we set μ = 0.3 t, barrier 0.2 t, and δUi = 0.

Short-wavelength disorder

We then consider the case iii) of a potential that varies on a shortlength scale, with local impurities of strength δUi randomly distributed between − U0/2 < δUi < U0/2, as shown in the upper left panel of Fig. 4 for U0 = 0.1 t. This is a relatively weak short-wavelength disorder of the Anderson type, that yields a long mean-free path ℓmf, much larger than the Fermi wavelength. The resulting Fraunhofer interference pattern for the critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) is shown in Fig. 4a, together with the rectification coefficient in Fig. 4b. Analogously to the previous case, the broken mirror symmetry Mx is sufficient to give a diode effect in the Fraunhofer interference pattern, which is qualitatively very similar to the case of a smooth uniform potential of Fig. 2a, b. In particular, spikes appear in the rectification in correspondence of the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern that are accompanied by sign changes of the rectification. In addition, we check that by imposing symmetry under Mx the JDE disappears. To this end, we first generate a configuration with δUi randomly distributed between −U0/2 < δUi < U0/2, and then symmetrize it such that \(\delta {U}_{i}\to (\delta {U}_{i}+{M}_{x}\delta {U}_{i}{M}_{x}^{-1})/2\). The resulting potential is shown in the upper right panel of Fig. 4c and the associated currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) shown in Fig. 3c are not distinguishable with the naked eye, as can be checked in Fig. 4d, where a maximal rectification of 0.4% appears.

The junction structure is as in Fig. 2. a Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ resulting from the local onsite potential δUi, with − U0/2 < δUi < U0/2 randomly distributed for U0 = 0.1 t, shown in the top-right inset. b Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (a). c Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ resulting from a local onsite potential δUi, with − U0/2 < δUi < U0/2 randomly distributed for U0 = 0.1 t and symmetrized \(\delta {U}_{i}\to (\delta {U}_{i}+{M}_{x}\delta {U}_{i}{M}_{x}^{-1})/2\), shown in the top-right inset. d Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (c). The chemical potential is set to μ = 0.3 t.

Disorder and fluctuations

A clear result that appears in all the simulations is the strong fluctuation in the rectification coefficient as we vary the magnetic field. By construction, the rectification coefficient is sensitive to variation of the critical currents and fluctuations in the latter are clearly amplified in the JDE. In Refs. 37,38,39, fluctuations in the critical current have been assessed in Josephson junctions characterized by a central disordered normal region, in analogy to universal conductance fluctuations42,43,44. There, it was shown that for systems in the regime ℓmf, L < ξ, in which neglecting the energy dependence of the scattering matrix is justified, fluctuations from sample to sample give a rms Ic = I0, with I0 = eΔ/ℏ. This result follows from the fact that the current is a linear statistics44,45,46, so that \({{{\rm{rms}}}}\,{I}_{c}/{I}_{0}={{{\mathscr{O}}}}(1)\) regardless of the number N of open channels38, as long as ℓmf ≪ L ≪ Nℓmf, and the lateral size is not much larger than the longitudinal one. If the junction is much wider than longer, as in the present case of a planar junction, we have \({{{\rm{rms}}}}\,I/{I}_{0}\propto \sqrt{W/L}\).

We assessed the fluctuations in the rectification coefficient by simulating random configurations of disorder of different strengths and as a function of the magnetic field. We assume no barrier, so that in absence of disorder the system responds with a given number of perfectly open channels. In Fig. 5a, we show the magneto-fingerprint of 50 different disorder configurations for a disorder strength U0 = 0.12 t, together with the statistical average over the 50 configurations in black. The latter gives a negligible rectification, as it is clearly understood considering that the rectification strongly varies with the disorder configurations, from positive to negative values. In addition, we clearly see a fishbone structure in the fluctuations, with a central bone with fluctuations of a given size and spikes at values of the field corresponding to the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern, with a period that slightly increases with the flux, in agreement with the clean case (not shown). In Fig. 5b, we plot the root mean square of η averaged over different disorder configurations. We clearly see that rms η starts from zero at zero field, as expected, and then saturates to a value that depends on the strength of disorder. In addition, well-defined spikes appear at multiples of the flux quantum. After the first spike, corresponding to the first node of the Fraunhofer pattern, rms η shows a field-independent value, that increases with the disorder strength. In Fig. 5c, we show rms η rescaled by the impurity strength, rms η × (t/U0), and we see that the curves tend to fall on top of each other in the lobes of the Fraunhofer pattern but not on the nodes, although we point out that the number of configurations is very small for a meaningful statistics. In addition, we notice that the fluctuations in rms η for low value of U0 also present regular jumps, as appreciated at low field, that originate from the activation/deactivation of the channels with the field.

a Rectification coefficient η for 50 disorder configurations and a given value of the strength U0 = 1.2 t. In black is the average rectification of the 50 random disorder configurations. b Root mean square of the rectification coefficient, \({{{\rm{rms}}}}\,\eta \equiv \sqrt{\langle {\eta }^{2}\rangle -{\langle \eta \rangle }^{2}}\), averaged over 50 different pseudorandom disorder configurations, versus the applied flux for different values of U0. The curve corresponding to U0 = 1.2 t is the square root of the average of the square of the curves in (a). In a, b μ = 0.3 t, L = 20, W = 100 and there is no barrier. c rms η × (t/U0) providing a scaling of the curves in (b) with the impurity strength.

These signatures are clear manifestations of the fluctuations of the critical current due to disorder and magnetic field. At the same time, we recall that at finite magnetic field, the current cannot be expressed as a linear statistics in the transmission eigenvalues. A common trend emerges in Fig. 5c, which points to a qualitatively universal behavior that requires further study. We further notice that the spikes at the node of the Fraunhofer pattern are a clear manifestation of the mirror symmetry breaking and can help in distinguishing other intrinsic sources of JDE.

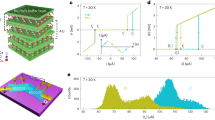

Multiple-loop SQUID

It is instructive at this point to consider a system that is expected to yield similar results, but that presents peculiar differences. This is the case of a system of N Josephson junctions connected in parallel, as shown in the inset of Fig. 6(a), each described by a single Energy-Phase Relations (EPR) of the form Eq. (S9) (Supplementary Material: Sec. III - Fraunhofer pattern of a multi-loop SQUID) and enclosing N − 1 loops threaded by a magnetic flux, that yields a Fraunhofer interference pattern. In ref. 21, this system was engineered to give rise to a very high rectification diode effect by properly choosing the transmissions of the junctions and the phases in the loops. Here, we are interested in describing the system as a discretized version of the wide planar Josephson junction so far discussed and to study the effect of spatial inhomogeneity as a source of JDE. The total Josephson EPR describing the system reads

where Φj is the total magnetic flux enclosed in the loops before the j-th junction, and we choose the gauge in which the phase φ drops at the first junction on the left side. When expressed in terms of Fourier components (see Supplementary Material: Sec. III - Fraunhofer pattern of a multi-loop SQUID), the current reads

where ϵn,j are the Foruier component of the EPR of the j-th junction, I0 = 2πΔ/Φ0 and φj = 2πBAj/Φ0 is the flux through the area Aj of the loop between junctions j − 1 and j, in units of Φ0/2π. The expression Eq. (11) meets two fundamental conditions at the same time: i) it breaks time-reversal symmetry, and ii) it generally breaks mirror symmetry j → N + 1 − j, thus allowing, in general, the appearance of a diode effect. This can be accomplished in two ways, i) by considering different transparencies τj and same areas of the loops, for which φj = 2π(j − 1)Φ/NΦ0, or ii) by keeping the same transparency τ for the junctions and considering different areas Aj of the loops, such that φj = 2π∑i≤jAjB/Φ0. In addition, the transmissions τj need to be sizable.

Interference pattern of the critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }(\Phi )\) of a multi-loop SQUID composed by N = 20 junctions as a function of the total flux Φ through the junction, as arising from the energy-phase relation Eq. (10). a Equal area junctions with random transparencies (shown in the inset). b Associated rectification coefficient. c Equal transmission τ = 0.9 junctions with random areas (shown in the inset). d Associated rectification coefficient.

i). An example of a Fraunhofer interference pattern for a parallel of 20 junctions with the transmission randomly distributed between 0.85 < τj < 0.95 is shown in Fig. 6a (the inset shows the particular configuration of transmissions). A nonreciprocal Fraunhofer interference pattern appears, with rectifications up to 40% close to the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern, as shown in Fig. 6b and in agreement with the planar junction case.

ii). The results for the case of slightly random fluxes φj is shown in Fig. 6c, for the case of equal transparencies τ = 0.9. We assume that Aj = Atot(1 − ϵ)/(N − 1) + δAj, with \(\mathop{\sum }_{j = 1}^{N-1}\delta {A}_{j}=\epsilon {A}_{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}\), in a way that we can study different disorder configurations with the same total area Atot, and choose ϵ = 0.1. In Fig. 6d, we see that the rectification can reach 20% and, as in the case of random transparencies, the most significant rectification values are observed at the nodes of the Fraunhofer pattern.

Multi-terminal case

The analysis presented for a two-terminal wide Josephson junction can be straightforwardly extended to the multiterminal case composed by j = 1, …, Nl leads, each with phase φj (Supplementary Material: Sec. I–Scattering Matrix Formulation). This configuration has been recently realized in ref. 47, where two of the three phase-differences of a four-terminal junction have been fixed and controlled by external fluxes in a two-loop configuration. Assuming a geometry of the scattering region and lead arrangements that yields a zero-field mirror symmetric multiterminal scattering matrix s, such that \({M}_{x}s(\Phi ){M}_{x}^{-1}=s(-\Phi )\), together with the Onsager reciprocity relations sT(Φ) = s( − Φ), it follows that the current in lead j satisfies

where \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{\varphi }}}}\) is a permutation of the phases φj that results from the mirror transformation. It then follows that a diode effect can appear already at zero field for values of the phases that are not invariant under mirror symmetry. In addition, a finite field yields a difference between the positive and negative critical current and a resulting diode effect in the Fraunhofer pattern for values of the phases that are not invariant under mirror symmetry.

To observe a Fraunhofer pattern, we consider a four-terminal symmetric structure, schematized in Fig. 7d, with a wide bottom contact kept at phase zero for reference, a top contact kept at phase φ with respect to the bottom terminal, and the lateral terminals kept at phase difference ±θ with respect to the reference terminal. In a mirror-symmetric setup, the critical currents between the top and bottom terminals satisfy

where the mirror symmetry transformation maps θ → −θ. This is seen in Fig. 7a, where we show the critical currents for the entire range 0≤θ < 2π. In addition, in Fig. 7b we plot the critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) four selected phase values θ = 0, ± π/2, π. As expected, for θ = 0 the two critical currents perfectly overlap. Care has to be taken in choosing a symmetric gauge for the vector potential, in that the lateral superconducting contacts are sensitive to an overall constant shift of the vector potential. For θ = π we see that \({I}_{c}^{+}(\pi ,-\pi ,\Phi )=-{I}_{c}^{-}(-\pi ,\pi ,-\Phi )\) and more generally we observe the behavior dictated by Eq. (13), as can be checked also in the entire (θ, Φ)-dependence of the rectification coefficient shown in Fig. 7c. This setup shows how the phases of the lateral superconducting contacts can be used as knobs to control the diode effect also in a mirror-symmetric system.

a Critical currents \({I}_{c}^{\pm }\) as a function of the external flux Φ for the entire (θ, Φ)- dependence and b for four selected values of the phase θ = 0, ±π/2, π. c Rectification coefficient η for the critical currents shown in (a). d Schematics of the junction, in which the bottom terminal serves as phase reference, and the top, left, and right terminals are kept at phase φ, θ, −θ, respectively. The central normal region has width W, length L, pierced by a magnetic field B that induces a flux Φ = BLW.

Discussion

The presented analysis sheds light on the ubiquity of the diode effect in wide planar Josephson junctions, showing how seemingly different spatially nonuniform junctions yield qualitatively similar JDE. The spatial dependence of the phase that Cooper pairs acquire in an orbital magnetic field fully emerges in the Fraunhofer interference pattern in planar Josephson junctions, which turn out to be particularly suitable to highlight the relevant symmetries enabling the onset of JDE. In particular, the conditions of time-reversal and inversion symmetry breaking are known to be necessary conditions that do not guarantee the onset of a diode effect. In turn, casting the analysis in terms of mirror symmetry breaking is more stringent. Although it is only possible to demonstrate that junctions that do not break the relevant mirror symmetry cannot show JDE, all the cases studied do indeed show JDE.

The relevant mirror plane is defined by the cross product between the orbital magnetic field and the direction of the phase bias (see Fig. 1). Interestingly, the same occurs in junctions with Rashba spin-orbit interactions and the Zeeman field in the plane3,6,7. Indeed, the cross product between the direction of the phase bias and the Zeeman field defines the plane of the junction as the relevant one for the mirror symmetry. The latter is necessarily broken when a Rashba spin-orbit interaction is present in the system.

We consider several cases of junctions that break the relevant mirror symmetry already in absence of magnetic field, either through smooth potentials compatible with back or side gates, or asymmetric junction shape, or through short-range scattering centers, such as those describing disorder at the atomic scale. All these conditions generally apply to physical devices, making the present analysis highly relevant to experiments.

Our symmetry-based results can be compared with other systems where JDE has been proposed, such as interacting quantum dots48,49, systems hosting helical phases50,51,52,53, multiband superconductors54, vortex-phase textures55, and through magnetization gradients56. In all these systems, the relevant mirror symmetry is broken.

The study of disorder averaging highlights interesting features of the rectification coefficient that can be ascribed to mesoscopic critical current fluctuations. In particular, the root mean square of the rectification appears to scale with the impurity strength, apart from the nodal points of the Fraunhofer pattern, where a strong magnification of the rectification occurs. The analysis presented points to the JDE as an interesting tool for studying mesoscopic critical current fluctuations, that calls for further study.

Finally, we extend the result to a four-terminal device, showing how a phase difference on the control leads yields rectification for finite external magnetic fields, providing an additional knob for tuning the diode effect.

References

Upadhyay, R. et al. Microwave quantum diode. Nat. Commun. 15, 630 (2024).

Ando, F. et al. Observation of superconducting diode effect. Nature 584, 373–376 (2020).

Baumgartner, C. et al. Supercurrent rectification and magnetochiral effects in symmetric josephson junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 39–44 (2022).

Bauriedl, L. et al. Supercurrent diode effect and magnetochiral anisotropy in few-layer nbse2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4266 (2022).

Strambini, E. et al. Superconducting spintronic tunnel diode. Nat. Commun. 13, 2431 (2022).

Costa, A. et al. Sign reversal of the josephson inductance magnetochiral anisotropy and 0–π-like transitions in supercurrent diodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1266–1272 (2023).

Nadeem, M., Fuhrer, M. S. & Wang, X. The superconducting diode effect. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 558–577 (2023).

Wakatsuki, R. et al. Nonreciprocal charge transport in noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602390 (2017).

Zhang, E. et al. Nonreciprocal superconducting nbse2 antenna. Nat. Commun. 11, 5634 (2020).

Itahashi, Y. M. et al. Nonreciprocal transport in gate-induced polar superconductor srtio<sub>3</sub>. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9120 (2020).

Lyu, Y.-Y. et al. Superconducting diode effect via conformal-mapped nanoholes. Nat. Commun. 12, 2703 (2021).

Narita, H. et al. Field-free superconducting diode effect in noncentrosymmetric superconductor/ferromagnet multilayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 823–828 (2022).

Lin, J.-X. et al. Zero-field superconducting diode effect in small-twist-angle trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 1221–1227 (2022).

Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Supercurrent diode effect and finite-momentum superconductors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2119548119 (2022).

Pal, B. et al. Josephson diode effect from cooper pair momentum in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 18, 1228–1233 (2022).

Fu, P.-H., Xu, Y., Liu, J.-F., Lee, C. H. & Ang, Y. S. Implementation of a transverse cooper-pair rectifier using an n-s junction. Phys. Rev. B 111, L020507 (2025).

Zhao, S. Y. F. et al. Time-reversal symmetry breaking superconductivity between twisted cuprate superconductors. Science 382, 1422–1427 (2023).

Ghosh, S. et al. High-temperature Josephson diode. Nat. Mater. 23, 612–618 (2024).

Lotfizadeh, N. et al. Superconducting diode effect sign change in epitaxial al-inas josephson junctions. Commun. Phys. 7, 120 (2024).

Souto, R. S., Leijnse, M. & Schrade, C. Josephson diode effect in supercurrent interferometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 267702 (2022).

Bozkurt, A. M., Brookman, J., Fatemi, V. & Akhmerov, A. R. Double-Fourier engineering of Josephson energy-phase relationships applied to diodes. SciPost Phys. 15, 204 (2023).

Margineda, D. et al. Sign reversal diode effect in superconducting dayem nanobridges. Commun. Phys. 6, 343 (2023).

Greco, A., Pichard, Q. & Giazotto, F. Josephson diode effect in monolithic dc-SQUIDs based on 3D Dayem nanobridges. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 092601 (2023).

Greco, A., Pichard, Q., Strambini, E. & Giazotto, F. Double loop dc-SQUID as a tunable Josephson diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 072601 (2024).

Hou, Y. et al. Ubiquitous superconducting diode effect in superconductor thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 027001 (2023).

Sundaresh, A., Väyrynen, J. I., Lyanda-Geller, Y. & Rokhinson, L. P. Diamagnetic mechanism of critical current non-reciprocity in multilayered superconductors. Nat. Commun. 14, 1628 (2023).

Krasnov, V. M., Oboznov, V. A. & Pedersen, N. F. Fluxon dynamics in long josephson junctions in the presence of a temperature gradient or spatial nonuniformity. Phys. Rev. B 55, 14486–14498 (1997).

Golod, T. & Krasnov, V. M. Demonstration of a superconducting diode-with-memory, operational at zero magnetic field with switchable nonreciprocity. Nat. Commun. 13, 3658 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Current induced hidden states in josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 15, 8059 (2024).

Gupta, M. et al. Gate-tunable superconducting diode effect in a three-terminal Josephson device. Nat. Commun. 14, 3078 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. Magnetic-field-free nonreciprocal transport in graphene multiterminal Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 034011 (2024).

Ciaccia, C. et al. Gate-tunable josephson diode in proximitized inas supercurrent interferometers. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 033131 (2023).

Margineda, D. et al. Back-action supercurrent rectifiers. Commun. Phys. 8, 1–7 (2025).

De Simoni, G. & Giazotto, F. Quasi-ideal feedback-loop supercurrent diode. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 064058 (2024).

Correa, J. H. & Nowak, M. P. Theory of universal diode effect in three-terminal Josephson junctions. SciPost Phys. 17, 037 (2024).

Bardeen, J., Kümmel, R., Jacobs, A. E. & Tewordt, L. Structure of vortex lines in pure superconductors. Phys. Rev. 187, 556–569 (1969).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Universal limit of critical-current fluctuations in mesoscopic josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 3836–3839 (1991).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Three “universal” mesoscopic josephson effects. In Transport Phenomena in Mesoscopic Systems (eds Fukuyama, H. & Ando, T.) 235–253 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1992).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Random-matrix theory of quantum transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 731–808 (1997).

van Heck, B., Mi, S. & Akhmerov, A. R. Single fermion manipulation via superconducting phase differences in multiterminal josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 90, 155450 (2014).

Groth, C. W., Wimmer, M., Akhmerov, A. R. & Waintal, X. Kwant: a software package for quantum transport. N. J. Phys. 16, 063065 (2014).

Altshuler, B. L. Fluctuations in the extrinsic conductivity of disordered conductors. Pis. ’ma Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 41, 530 (1985).

Lee, P. A. & Stone, A. D. Universal conductance fluctuations in metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1622–1625 (1985).

Imry, Y. Active transmission channels and universal conductance fluctuations. Europhys. Lett. 1, 249 (1986).

A. D. Stone, K. A. M. J.-L. P., P. A. Mello. Chapter 9 - random matrix theory and maximum entropy models for disordered conductors. In ALTSHULER, B., LEE, P. & WEBB, R. (eds.) Mesoscopic Phenomena in Solids, vol. 30 of Modern Problems in Condensed Matter Sciences, 369–448. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444884541500152 (Elsevier, 1991).

Altshuler, B. L., Lee, P. A. & Webb, W. R. Mesoscopic phenomena in solids https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9780444600417_A25076395/preview-9780444600417_A25076395.pdf (Elsevier, 2012).

Coraiola, M. et al. Flux-tunable josephson diode effect in a hybrid four-terminal josephson junction. ACS Nano 18, 9221–9231 (2024).

Debnath, D. & Dutta, P. Gate-tunable josephson diode effect in rashba spin-orbit coupled quantum dot junctions. Phys. Rev. B 109, 174511 (2024).

Debnath, D. & Dutta, P. Field-free Josephson diode effect in interacting chiral quantum dot junctions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 37, 175301 (2025).

He, J. J., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. A phenomenological theory of superconductor diodes. N. J. Phys. 24, 053014 (2022).

Daido, A. & Yanase, Y. Superconducting diode effect and nonreciprocal transition lines. Phys. Rev. B 106, 205206 (2022).

Ilić, S. & Bergeret, F. S. Theory of the supercurrent diode effect in rashba superconductors with arbitrary disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 177001 (2022).

Fu, P.-H. et al. Field-effect josephson diode via asymmetric spin-momentum locking states. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 054057 (2024).

Yerin, Y., Drechsler, S.-L., Varlamov, A. A., Cuoco, M. & Giazotto, F. Supercurrent rectification with time-reversal symmetry broken multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 110, 054501 (2024).

Fukaya, Y. et al. Design of supercurrent diode by vortex phase texture. arXiv https://arxiv.org/html/2403.04421v2 (2024).

Roig, M., Kotetes, P. & Andersen, B. M. Superconducting diodes from magnetization gradients. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144503 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge S. Heun for valuable discussions and for carefully reading the manuscript. L.C. acknowledges the Fondazione Cariplo under the grant 2023-2594. M.C. and F.G. acknowledge the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Framework Programme under Grants No. 964398 (SUPERGATE) and the PNRR MUR project PE0000023-NQSTI for partial financial support. F.G. acknowledges partial financial support under Grant No. 101057977 (SPECTRUM). E.S. acknowledges the project HelicS, project number DFM.AD002.206. We acknowledge NextGenerationEU PRIN project 2022A8CJP3 (GAMESQUAD) for partial financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. entirely performed the theoretical analysis, from conceiving the problem to the numerical simulations, A.C., E.S. and M.C. contributed to the discussions, the theoretical analysis, the experimental contextualization, and the writing of the paper, A.G., L.A. and F.G. contributed to the discussions and the reading of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chirolli, L., Greco, A., Crippa, A. et al. Diode effect in the Fraunhofer pattern of disordered planar Josephson junctions. Commun Phys 8, 483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02364-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02364-y