Abstract

When light and matter interact strongly, the resulting hybrid system inherits properties from both constituents, allowing one to modify the material behavior by engineering the surrounding electromagnetic environment. This concept underlies the emerging paradigm of cavity materials engineering, which aims at the control of material properties via tailored vacuum fluctuations of dark photonic environments. The theoretical description of such systems is challenging due to the combined complexity of extended electronic states and quantum electromagnetic fields. Here, we derive an effective, non-perturbative theory for low-dimensional crystals embedded in a Fabry-Perot resonator. Starting from the full Pauli-Fierz Hamiltonian, we reduce the cavity field to an effective single-mode description within the long-wavelength limit, while retrieving the correct scaling of the light-matter interaction when the system size is scaled up to the extended system limit. This scaling is akin to the case where all the full continuum of cavity states are included in the light-matter interaction Hamiltonian. By explicitly accounting for the finite reflectivity of cavity mirrors, our theory also avoids double counting the contribution from free-space light-matter coupling. Our method provides a fully ab-initio framework to simplify the description of cavity-matter interactions for extended systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

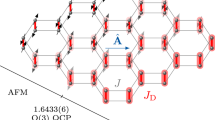

Historically, the physics of strong light-matter interactions has primarily drawn interest in the field of quantum optics1. However, in recent years, the possibility of exploiting strong-light matter coupling for material design and tuning of chemical properties has sparked growing interest in the condensed-matter community. When matter interacts strongly with light, hybrid light-matter states, called polaritons, emerge. Because these polaritonic states inherit properties from both constituents, it is possible to alter the properties of the coupled system by changing either of the two2,3,4. Strong light-matter coupling5 has for example, been exploited to alter the optical properties in semi-conductors and in quantum Hall systems6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. More recently, the appealing scenario of modifying equilibrium material properties via the coupling to the electromagnetic fluctations of a dark dielectric environment has led to the proposal of light-mediated superconductivity originating from cavity-induced electron-pairing22 or from polariton condensation23. Tunable superconductive temperature has also been proposed for both a FeSe/SrTiO324 system and MgB225 bulk crystal, as a result of the polaritonic enhancement of the electron-phonon coupling, and in the case of MgB2 the critical superconductive temperature is increased. In a recent work26, the idea of using circularly polarized cavities to alter the topology of a crystal has been put forward and theoretically demonstrated by the appearance of a quantized Hall conductance associated with an integer Chern number in graphene27,28. Strong coupling of Tera-Hertz (THz) cavities to the ferroelectric soft phonon mode of SrTiO3 has been proposed to aid the paraelectric-to-ferroelectric phase transition29 and generate a ferroelectric photo-groundstate30. In general, it is worth mentioning that different point of view have been proposed in the literature on the possibility of mediating quantum phase transitions through cavities, and the reader should consult further literature31,32,33. There is, however, agreement on the fact that in the presence of material non-linearities and/or multiple photonic modes such transitions cannot be excluded3,4,34,35. For instance, a recent experiment reported a 50 K reduction in the transition temperature for the metal-to-insulator phase transition in 1T-TaS2 when the TaS2 crystal is embedded in a Giga-Hertz (GHz) cavity36. Similar temperature effects have been proposed in the context of strong light-matter coupling of molecular systems37,38,39. Several other interesting predictions and effects are discussed in recent reviews40,41,42.

The set of methods employed in theoretical work on cavity-matter systems has been scattered and often developed from a different underlying theory. For molecular systems, efforts have been devoted to generalizing quantum chemistry methods, such as configuration interaction and coupled cluster, to quantum electrodynamics (QED) to provide a numerical approach for accurate calculations of molecular properties in idealized electromagnetic environments43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. The density functional theory generalization to QED has initially been made practical for the prediction of ground-state properties and the linear response of molecular systems in idealized cavities53,54,55,56,57,58,59, but has been recently extended to crystalline systems with the development of a local functional60. Notably, the combination of density functional theory with Macroscopic QED has demonstrated the potential to treat realistic cavity setups accounting for excited state properties of materials in realistic lossy electromagnetic fields61,62,63,64,65. Finally, exact diagonalization of ab-initio-based Hamiltonians represented in a reduced space has been used to predict the formation of composite quasi-particles of light66,67 and hybrid light-matter groundstates30.

With the idea of cavity-material engineering gaining momentum, the ab initio theoretical treatment of a cavity coupled to an extended solid-state system needs to be formalized on common grounds, building on existing work1,3,35,68. For extended systems, it is crucial to account for the infinite amount of photonic degrees of freedom, inherent to the multi-mode nature of the electromagnetic field69, in order to avoid an artificial decoupling between light and matter when the bulk limit of the system is considered22,70,71,72. Discarding such a multi-mode nature would fail to capture light-matter interactions in bulk setups, contradicting recent experimental results36,73. The focus of this work is to demonstrate that it is possible to derive an effective ab initio theory of interacting light and matter in the ground state based on a Hamiltonian consisting of a few effective photonic degrees of freedom. Our method is hence distinct from existing effective approaches based on decoupled light-matter Green’s function theory or that rely on external baths74,75,76. An ab-initio approach for interacting light-matter systems can provide theoretical predictions with a minimal set of modeling assumptions, and hence can be helpful to reconcile the different point of view in existing literature3,35. More specifically, allowing for basis set convergence, an ab initio approach gives the opportunity to resolve potential issues with gauge ambiguities77,78,79 arising from the fact that the matter system is described in a restricted basis set (such as in the case of a tight-binding approximation).

In our effective ab-initio approach, we provide key conceptual advancements: (i) We show that even when neglecting the momentum carried by the light and considering an extended cavity, the characteristic size of the confined effective electromagnetic radiation, and consequently the light-matter coupling, remains finite. (ii) We provide an Hamiltonian description grounded on QED free from the double counting of the coupling to the free-space electromagnetic background. (iii) We present an Hamiltonian-based justification for the use of a few effective modes treatment of the cavity-matter problem at equilibrium.

In practice, we show how the modes of a Fabry-Pérot cavity with non perfectly reflective mirrors, described via a purely real dispersive refractive index, interact with an extended solid in the long-wavelength approximation employing the following steps: (a) We build the photonic modes as a linear combination of isotropic free-space basis states, solving Maxwell’s equations for a finite reflectivity cavity (rather than introducing the cavity via idealized perfect boundary conditions). (b) We remove the spurious free-space light-matter coupling double-counting by subtracting the contribution of the cavity in the limit of mirrors with zero reflectivity. (c) From the cavity mirrors properties and by employing the long wavelength approximation, we determine the relevant interaction length scales that define the strength of the light-matter coupling in the single effective mode treatment. Our scheme leads to an Hamiltonian which maintains the correct scaling properties with system size up to the limit of extended materials, while featuring the simplicity of a few-photonic modes theory. Such an approach can be the starting point for numerically exact non-perturbative methods for simple systems38 as well as for more elaborate many-body approaches80, as discussed in the “Conclusions” section. We note that for a fully realistic cavity modeling, the imaginary part of the refractive index of the mirrors, which are usually associated with losses in excited systems, should be taken into account as well. Although a coupled light-matter ground-state theory, as the one presented here, is inherently lossless81, the imaginary part of the mirror susceptibility can affect the calculation of the light-matter coupling strength. The extension to a such more general case would require the reformulation of the quantization scheme for the electromagnetic field, as for example prescribed by Macroscopic QED64,65,82. Nevertheless, our approach is still necessary to define the effective Hamiltonian, which avoids free-space double counting and leads to a finite light-matter coupling for extended cavity systems in the few-mode approximation.

This work represents a step towards the realistic theoretical modeling of cavity-material engineering by providing an approach to determine an effective ab-initio based few-mode Hamiltonian, where the light-matter coupling strength can be calculated by connecting cavity-mirror and embedded-material properties.

Methods

Light-matter coupling in QED

Coupled light-matter Hamiltonian in free space

The coupling between quantized matter and quantized light is formally described by the theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED). In order to allow for considerations on the scaling of light-matter interaction on system size83, we keep the dependence on the latter explicit. Furthermore, we note that under the constraints of homogeneity and isotropy of space, the quantization volume for the electromagnetic field has to be chosen as a cube with edge length L and periodic boundary conditions39. It is important to emphasize that L is a completely arbitrary length scale and therefore we should expect no physical dependence on its choice in the final theory.

In the Coulomb gauge, we can restrict the explicit quantization of the electromagnetic field to the two transverse polarizations. The mode functions are the free-space plane wave solutions to Maxwell’s equations and the related transverse vector potential reads84 (we use SI-based atomic units throughout this work)

where V = L3 is the quantization volume, ωq = c∣q∣ the frequency of the mode with momentum q, ϵqλ the polarization function, and λ is an index that runs over the two transverse polarizations. The longitudinal part of the electromagnetic field leads instead to the well-known matter-matter Coulomb interaction84.

We introduce the light-matter coupling via the minimal-coupling prescription \(\hat{{{\bf{p}}}}\to \hat{{{\bf{p}}}}+\hat{{{\bf{A}}}}\) by imposing local gauge invariance. This ensures local charge conservation and in principle, provides us with a fully relativistic description of QED. Here we use the low-energy approximation of QED as encoded in the Pauli-Fierz (PF) Hamiltonian81,

where v(rl, rm) and ϕ(rl) are the Coulomb interaction and the external potential acting on the electrons, respectively. Note that the ab initio PF Hamiltonian can be extended to include the nuclei/ions as effective quantum particles39,85 and to the (semi-)relativistic limit81. A key feature of the PF Hamiltonian is that it guarantees the existence of a groundstate and hence provides unambiguous access to equilibrium properties of coupled light-matter systems86. It thus allows for extensions of various known first-principles methods from quantum mechanics to QED39.

Quantization of the electromagnetic field in the presence of mirrors: the Fabry-Pérot cavity

The relatively featureless electromagnetic modes of free space can be modified by introducing tailored electromagnetically active material structures in the environment. We will refer to such structures as cavities, the presence of which serve to alter the electromagnetic environment by selectively enhancing certain modes while suppressing others. In simple terms, the role of the cavity is to redistribute the electromagnetic states both spatially and spectrally. The resonances of a given cavity setup will depend on its material composition, size, and structural morphology87,88,89,90. There consequently exists a wide range of cavity designs, ranging from a simple planar geometry, to bow-tie shaped arrays, metasurfaces and photonic crystals with more complex topology and all this is in turn paired with the possibility of using both metallic and dielectric material constituents88,91,92,93,94,95,96,97. Considering the vast degrees of freedom in cavity fabrication, both in the choice of the geometry and the constituting materials, and the fact that light-matter interaction is a joint light and matter property, the design space of cavity-matter systems is immense.

In this work, we consider a paradigmatic example of an optical cavity consisting of two parallel thin mirrors separated by a distance Lc, which can host a 2D extended material, as sketched in Fig. 1. This setup is referred to as a Fabry-Pérot cavity. The presence of the mirrors promotes the modes which are (near) compatible with the standing wave conditions, i.e. \({q}_{z}=n\frac{\pi }{{L}_{{{\rm{c}}}}},\,n\in {\mathbb{N}}\) and suppresses the rest. Such a setup is particularly amenable to asses the scaling of the light-matter coupling with system size as both the host material and the electromagnetic environment can be easily scaled in the planar dimensions. Unlike often done in the literature, we introduce the cavity in the electromagnetic environment not by imposing perfect boundary conditions but rather by considering mirrors whose reflectivity and transmission are characterized by purely real Fresnel coefficients, r, t. We assume that the cavity has no effect on the longitudinal part, i.e., that in the cavity the longitudinal Coulomb interaction is not affected (see Supplementary note 7 for a more detailed discussion). This approximation is reasonable for a material that is placed far enough from the cavity mirror, as the effect of longitudinal fields decay as a power law with the mirror distance98. We also specialize in a cavity with identical top and bottom mirrors while emphasizing that this choice has no qualitative impact on the results. We can therefore directly expand the quantized vector potential in the cavity in terms of the original free-space photonic modes in Eq. (1) provided that the mode functions are modified accordingly.

a Illustration of a non-perfectly reflecting Fabry-Pérot cavity hosting a 2D crystal. b For the mathematical description, the cavity-matter system is contained in an isotropic, cubic quantization box with sides of length L. In the out-of-plane (z)-direction the cavity and material have a fixed length scale, i.e., the mirrors are at a distance Lc and the material has a thickness d and it is placed in the center of the cavity. To make the quantization procedure simple we choose a cavity, where the in-plane length scale coincides with the quantization length, i.e., L∥ = L. Panel (b) also shows a sketch of the out-of-plane dependence for the relevant fundamental mode function M(z) of the photonic field and for the matter momentum matrix element p(z).

In the following we fix the two thin mirrors at z = ± Lc/2 respectively. The presence of the mirrors breaks translation invariance in the out-of-plane direction and couples modes propagating upwards and downwards. It is therefore convenient to separate the sum over the photonic modes in Eq. (1) into in-plane and out-of-plane momenta sums and further split the latter into top propagating and bottom propagating momenta. A proper analytical expression for the cavity modified vector potential can be derived using standard transfer matrix techniques as shown in Supplementary note 1 and reads,

The above expansion is rather intuitive, as the effect of the Fabry-Pérot cavity is simply encoded in the \({{{\bf{M}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }(z)\) mode functions, with λ either the s or p polarization99 and α top and bottom propagation index. We emphasize that each mode is normalized over the full quantization volume V = L3. Introducing the mirrors in the original quantization box breaks isotropicity, potentially challenging the possibility of recovering the isotropic free-space limit. We stress, however, that since we have control over the Fresnel coefficients of the mirror, we can recover the correct free space limit by making the mirrors completely transparent. It is important to mention that the quantization procedure here is equivalent to existing procedure used in the context of Macroscopic QED in the absence of losses74.

Coupled light-matter Hamiltonian with a Fabry Pérot cavity

Next we consider the Fabry-Pérot cavity coupled to a 2D crystal, as sketched in Fig. 1. The discussion can be readily adapted to any type of lossless cavity. For notational convenience, we first translate the PF Hamiltonian into the language of second quantization for the electrons. It is important to stress that for any calculation employing the PF Hamiltonian in second quantization, without further care, one should restrict to a specific particle-number subspace of the full Fock space to have physically meaningful results (see Supplementary note 6 for further details). For extended 2D crystalline systems, the in-plane periodicity of the crystal potential ϕ(r) = ϕ(r + R∥) makes it convenient to represent the fermionic annihilation and creation operators in terms of in-plane periodic Bloch’s functions,

with \(\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}\) restricted to the unit cell, R∥ the lattice vector of the n-th unit cell, \({u}_{i{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }}(\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}\sigma )={u}_{i{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }}((\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}+{{{\bf{R}}}}_{\parallel })\sigma )\) is the periodic part of the Bloch wave function, SM the in-plane area covered by the full matter system, and \({\hat{c}}_{i{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }\sigma }\) the annihilation operator of an electron in a Bloch state with index ik∥ in the first Brillouin zone (BZ) of the crystal. In general, the periodicity of the crystal might not be consistent with the cubic symmetry implied by the quantized electromagnetic field. In such cases there is no direct mapping between matter and photon momenta. A discussion on this and related issues is presented in Supplementary note 2. Crucially, the long-wavelength approximation (LWA) will allow us to avoid this problem. Under the assumptions mentioned above, and as shown in Supplementary note 3 and similar to ref. 69, the Bloch form of the PF Hamiltonian for the coupled Fabry-Pérot cavity matter system becomes,

where we have grouped the electronic single-particle and interaction terms into \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{el}}}}\), defined Ωz as the matter unit cell dimension in the z-direction (note that since here we consider no momentum dispersion for the matter in the z-direction, the unit cell should contain all the potential layers of the material) and we have defined the momentum and overlap matrix elements, \({{{\bf{p}}}}_{ij\sigma {{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }{q}_{z}}(z)\) and \({s}_{ij\sigma {{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }^{{\prime} }}(z)\) respectively, in Supplementary note 3. Eq. (5) explicitly contains all the possible momentum-conserving electron-photon interactions separated into a paramagnetic (coupling to the matter momenta) and a diamagnetic (coupling to the matter density) term. It is interesting to notice how the diamagnetic term written in this general multi-mode framework explicitly couples otherwise non-interacting photonic modes because of the presence of matter.

The long-wavelength approximation for the coupled light-matter system

In its full form, the PF Hamiltonian contains a potentially infinite amount of cavity modes, and these modes are mutually coupled via the diamagnetic term. This makes working with the full PF Hamiltonian highly impractical. In the following we will therefore seek a suitable simplification which will allow us to consider the effect of the cavity on a material in its bulk limit by applying the long wavelength approximation.

Operational definitions

Because the field of interacting light-matter systems is approached by experts with diverse backgrounds, e.g. condensed matter physics, quantum optics and quantum chemistry, we find it essential to provide a working definition of the nomenclature used throughout this work. Whenever referring to the long wavelength approximation (LWA), we assume that the momentum carried by the modes of the electromagnetic field can be neglected from the point of view of the matter. The validity of this assumption is guaranteed as long as the photon momenta are below some momentum cut-offs for the in-plane-, and out-of-plane components, denoted by \({{{\bf{q}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},\parallel }^{{{\rm{lw}}}}\) and \({q}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{z}}}}^{{{\rm{lw}}}}\), respectively. The LWA has much in common with the widely used dipole approximation of atomic and molecular physics. However, while they are the same for finite systems like atoms and molecules, the two have important differences when considering extended systems. Within the dipole approximation, it is assumed that the spatial extent of the matter is much smaller than the characteristic length scale of the field variations. Any mode with \(| {{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }| > \frac{2\pi }{{S}_{M}^{1/2}}\) should therefore be discarded. As we increase the size of the system, we thus have to discard more and more modes from our theory to fulfil the dipole approximation, effectively leading to a light-matter decoupling in the limit of a bulk material. Within this definition of dipole approximation a number of recent works33,100, have argued that in the limit where the cavity-matter size goes to infinity, the effect of the virtual fluctuations of the cavity electromagnetic field on the material properties vanishes. However, we stress that this decoupling reflects the stringent conditions enforced by the dipole approximation, which ignores the multi-mode nature of the electromagnetic field. Especially in the case of extended systems, the LWA is instead less stringent69,70. Disregarding surface modes such as surface plasmon polaritons, which are beyond the direct applicability of the approach in this work, the momentum carried by any mode in a Fabry-Pérot cavity is negligible compared to the momentum scales over which the electronic matrix elements vary. For the momentum transfers that actually enter into the sums in Eq. (5), we are justified in applying the LWA even though \(| {{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }| > \frac{2\pi }{{S}_{M}^{1/2}}\) for some of the modes up to the cut-offs defined above.

In view of the analysis on the scaling of the light-matter coupling with system size it is relevant to discuss the definition of the thermodynamic limit. Given a system of volume VM, the thermodynamic limit (often referred to as macroscopic limit) is defined as VM → ∞. While taking this limit is formally justified when treating the uncoupled light or the uncoupled matter systems alone, the same is not automatically true for hybrid-light matter systems as discussed in more details in “the bulk limit of the light-matter coupling” subsection in the “Results” section. In short, for the strict dipole approximation, if we take the volume to infinity we decouple light and matter; on the contrary, within the LWA, if the amount of matter included in the coupling is not restricted (by the physical length scales set by the cavity as shown later in this work) the light-matter coupling diverges to infinity. Therefore, in this work, we consider instead the bulk limit which is defined as the limit where the material properties are the ones of its bulk form, yet not limited by the characteristic lengths set by the cavity, as explained in “The bulk limit of the light-matter coupling” subsection. Note that since in this work we consider 2D crystals, the bulk limit should be interpreted as the limit of a 2D bulk.

PF Hamiltonian in the LWA

To make the effective LWA of Eq. (5), we can neglect the variation of the electromagnetic field across the vertical width d of the 2D material and define the q∥ = 0 component of \({\bar{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{ij\sigma {{\bf{k}}}{{\bf{q}}}}(z)\) integrated in the z-direction as \({\bar{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{ij\sigma {{\bf{k}}}{{\boldsymbol{0}}}}\) (see Supplementary note 3). We note that for thicker materials with widths comparable to the wavelength of the cavity mode, it is important to consider the variation of the field across the width of the material. However, that should not qualitatively impact the conclusions in the following. This allows us to evaluate the polarization functions of the cavity directly at its center, and it is therefore convenient to define \({\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }={{{\bf{M}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }(z=0)\). We can then rewrite the photon mode functions as \({\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }={\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }^{\parallel }+{\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }^{z}\), where ∥(z) refers to the part of \({\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }\) which is parallel(perpendicular) to the mirrors. Under the approximation of vanishing out-of-plane polarization of the matter, we can thus write,

By inspection of the polarization vectors in Eqs. S1.4-6 we see that the s-polarization is unaffected by the approximation since \({\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },s,{q}_{z}\alpha }={\bar{{{\bf{M}}}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },s,{q}_{z}\alpha }^{\parallel }\) already holds, unlike the case of the p-polarization. As shown in Supplementary note 1, for both polarizations, we can define a new set of photonic operators,

and new effective vector-potential amplitudes for the two polarizations,

where \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },p,{q}_{z}\alpha }\) are the new mode functions as derived in Supplementary note 1. Notice that the prefactor \(\frac{{q}_{z}}{\sqrt{{q}_{z}^{2}+{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }^{2}}}\) takes care of the in-plane projection of the p-polarization mode function (see Supplementary note 1). If we assume that the polarization of the electronic system is isotropic in-plane, the product \({\bar{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{ij\sigma {{\bf{k}}}{{\boldsymbol{0}}}}\cdot {{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}}\) is the same for all directions. We can therefore define \({\bar{{{\bf{p}}}}}_{ij\sigma {{\bf{k}}}{{\boldsymbol{0}}}}\cdot {{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}}\equiv {\bar{p}}_{ij\sigma {{\bf{k}}}{{\boldsymbol{0}}}}\) and recast Eq. (5) as,

To obtain the equations above we have also used the fact that the matrix elements \({s}_{ij\sigma {{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }{{\boldsymbol{00}}}}={\delta }_{ij}\) due to the orthonormality of the \({u}_{i{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }}(\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}\sigma )\) on the unit cell. We therefore observe that the effect of the cavity is to “dress” the free-space modes of the electromagnetic field by changing the prominence of different wave vectors in the cavity. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 2(b), from the dependence of \(\left\vert {\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },p,{q}_{z}\alpha }\right\vert\) on qz, we observe that the cavity enhances qz which are close to the standing wave condition in the limit of the perfectly reflective Fabry-Pérot cavity \({q}_{c,n}=n\frac{\pi }{{L}_{c}}\) for \(n\in {\mathbb{N}}\), and suppresses the rest. We only observe the odd modes in Fig. 2b because the material is placed in the center of the cavity and thus overlaps with a node of the even modes and an anti-node of the odd modes. This is consistent with what we expect from the real- and reciprocal space characteristics of a Fabry-Pérot cavity.

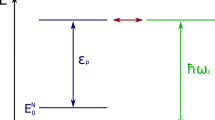

a Mode dispersion of the fundamental mode in the ideal Fabry-Pérot cavity, and (b) the mode function of the ideal Fabry-Pérot cavity in qz-space. The effect of the cavity is to pin qz to a narrow range, and the result is that the relevant frequencies to count, in the effective mode construction, are the ones shown by the shaded area in (a). The width of this area depends on the width γ which in turn is related to the mirror reflectivity as discussed in “The effective-mode description” subsection in the “Results” section. The inset in (a) shows different reflectivity profiles used to generate the curves in (b). Modes above the reflectivity cut-off quickly approach the free-space case. This is also clear when looking at the spatial mode functions in the inset of (b) which shows the first and third mode for a reflectivity r = 0.95. Since the first mode lives in the frequency region where the mirrors are highly reflective and the third lives above the plasma frequency of the mirror, ωp, the confinement of the first mode is significantly larger than for the third mode, and it is consequently closer to a standing wave and significantly more enhanced.

A remaining question is what cut-offs to apply for the in-plane and out-of-plane directions. We will return to this point in “The in-plane cut-off” and “The out-of-plane cut-off” subsections, respectively.

Removing free-space contributions from the light-matter coupling

A final issue for any calculation involving light-matter coupling from QED is the comparison to the free-space limit. Physically, one needs to make sure that coupling of matter to the fluctuating photons present in free space, which is already encoded in the observable masses of the particles, is not double-counted in the theory. For this purpose our formulation of the light-matter problem is very convenient, indeed (i) it quantizes the electromagnetic field isotropically, which is the underlying assumption used in QED to derive the mass of the particles, (ii) it allows to recover the isotropic free-space limit of quantum mechanics by setting the reflectivity of the cavity to zero. Without such construction one would have to rewrite the PF Hamiltonian using bare particle masses, which can become cumbersome. Our approach, instead, allows us to work with standard effective masses for the matter particles, provided that we subtract the terms that are already present in the free-space coupling.

In order to accomplish this, we need to distinguish between the vacuum and reflected contributions to the photonic field. Looking at Eqs. (7)-(10), we observe that the effect of the cavity enters via \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },p,{q}_{z}\alpha }\). Noting that \(\frac{1}{1-x}={\sum }_{n = 0}^{\infty }{x}^{n}\) for ∣x∣≤1 we can write,

We approach free space by making the mirrors more transparent (t → 1 and r → 0). The first term contains no reflections and thus represents the remaining free space contribution while the last two terms are exclusively cavity contributions. In free space \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }=1\) and we can thus remove the free space double counting by using,

instead of the bare mode functions. In this way, we arrive at an effective mode construction which vanishes as we approach free space (t → 1 and r → 0) and the sole effect is to modify the effective mode function as in Fig. 3c. In the following, our definitions will therefore be in terms of \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }^{{{\rm{NF}}}}\) and not \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }\).

a The effective coupling strength (solid light blue) and the fundamental cavity frequency (dashed purple) as a function of mirror seperation, Lc for a fixed reflectivity of 0.99. The inset shows a visualization of the part of q-space which contributes to the single effective mode. b The effective coupling strength aeff,s/ωc as a function of the mirror reflectivity for a symmetric Fabry-Pérot cavity with (purple) and without (light blue) the removal of the free space mode contribution. The ratio aeff,s/ωc is independent of the frequency, and it therefore provides a scale-invariant representation of the cavity single effective mode coupling strength in the Fabry-Pérot cavity. c The cavity mode functions, \(| {\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },s,{q}_{z},F}|\), with (purple) and without (light blue) the free space contribution.

Results

The effective-mode description

While significantly simpler than Eq. (5), the multi-mode nature of Eq. (11), which for the arbitrary length scale L → ∞ would turn into a continuum, is still impractical for most calculations. In this section we devise an effective-mode description that keeps the appropriate size scaling of the light-matter problem while simplifying computations. The overarching idea is that within the LWA, the effect of the photonic modes can be encoded into a single re-scaled photonic mode for each polarization consisting of collectively oscillating photons. Here we highlight the main points leading to the effective-mode Hamiltonian and we refer to Supplementary note 4 for a step-by-step derivation.

Collective Canonical transformation

We first notice that if, in the LWA, we neglect the angular (q∥) dependence of the mirror’s Fresnel coefficients, \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }\) is independent of q∥. For cavity mirrors with high reflectivity and a material placed in the center of the cavity, the functions \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },{q}_{z}\alpha }\) are peaked around the odd standing wave conditions of the perfectly reflecting Fabry-Pérot cavity. Furthermore, for a real mirror, the frequency dependence of the reflectivity can be engineered to give a decreased confinement for modes with n > 1 (see inset of Fig. 2a) so that \({\bar{A}}_{{{\boldsymbol{0}}},{q}_{z}\alpha }\) can be approximated to a single peak function centered around qz,1 (like in Fig. 2b). We stress that the latter is a convenience choice and that it would be possible to perform a similar procedure, separately for each of the modes (allowed by the cavity and the LWA) with n > 1 and eventually arriving at an effective few modes Hamiltonian. In Fig. 2b the out-of-plane mode profile associated with the visible peaks at qz,1 and qz,3 are illustrated in the insets to highlight how the non-perfect reflectivity of the mirrors allows “leakage” outside the cavity. The “leakage” is exactly what allows to couple a cavity with radiation from the outside. We note in passing that for any Fabry-Pérot cavity, \({q}_{z,1} < {q}_{{{\rm{c}}},z}^{{{\rm{lw}}}}\) due to the atomic thickness of 2D materials guarantees consistency with the LWA for the modes included in our theory.

While \({\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }\) does not depend on the in-plane momentum, the functions in Eqs. (9) and (10) do, via \({\omega }_{{q}_{\parallel }{q}_{z}}=\sqrt{{q}_{\parallel }^{2}+{q}_{z}^{2}}\). The behaviour of \({\omega }_{{q}_{\parallel },{q}_{z}}\) when qz is pinned to the first cavity resonance is shown in Fig. 2a. We note that this dispersion, while critical when considering resonant phenomena, such as in the case of polariton relaxation101 and transport102,103,104, is not expected to play an important role when considering equilibrium changes to the material due to the off-resonant nature of the coupling between light and matter in this case.

With all the above consideration we define an effective coefficient Aeff,λ by setting \({\omega }_{{q}_{\parallel }{q}_{z}}={\omega }_{{{\rm{c}}}}\) and average the functions \({\bar{A}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }\) in the qz variable within a region of width γ centered around qz,1, in formulas

where we further note that \({\bar{A}}_{{q}_{\parallel }\lambda ,{q}_{z}\alpha }\) is independent of the propagation direction α because the crystal is centered at z = 0. Note that lz here is the number of modes within the averaging region and together with γ are formally defined in relation to the cut-offs as given in “The out-of-plane cut-off” subsection below.

Now that all modes share the same coefficient Aeff,λ, it is natural to define the total displacement operator for each of the two polarizations,

which is the photonic operator that directly appears in the paramagnetic term in Eq. (11). As shown in Supplementary note 4, this total operator paired with the respective relative operators, can be used as a starting point for a canonical transformation and allows us to simplify the LWA PF Hamiltonian to,

where we have introduced a new set of creation and annihilation photonic operators \({\hat{B}}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}^{{\dagger} }\) and \({\hat{B}}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) associated with the operator \({\hat{Q}}_{{{\rm{eff}}},\lambda }\), defined the total electron momentum operator as \({\hat{P}}_{{{\rm{el}}}}\equiv {\sum }_{ij\sigma {{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }}{\hat{c}}_{i{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }\sigma }^{{\dagger} }{\hat{c}}_{j{{{\bf{k}}}}_{\parallel }\sigma }{\bar{p}}_{ij\sigma {{\bf{k}}}{{\boldsymbol{0}}}}\), the electronic number operator, and l∥ is defined in “The in-plane cut-off” subsection. We note that the total momentum and number of particles operators are not bound to the effective-mode construction, but they already appear in Eq. (11) due to the LWA. Further note that we have grouped the decoupled terms related to the relative photonic coordinates into \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{EM}}},{{\rm{rel}}}}\).

Eq. (16) directly highlights a fundamental feature of our effective theory: the collective photon modes acquire the weight of all the original photonic modes up to the cut-offs \({{{\bf{q}}}}_{{{\rm{c,\parallel }}}}^{{{\rm{lw}}}}\) and \({{{\bf{q}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{z}}}}^{{{\rm{lw}}}}\). To determine how the light-matter coupling scales with quantization volume, it is therefore necessary to determine how many modes contribute to the effective mode construction. As we shall see, this indeed leads to a light-matter coupling which is independent of the quantization volume.

In-Plane cut-off

If we neglect coupling to any surface modes that might exist near the mirrors, the largest momentum of any mode modified by the Fabry-Pérot cavity is \({q}_{p}=\frac{{\omega }_{{{\rm{p}}}}}{c}\) where ωp is the frequency where the mirrors reflectivity drops (which in the case of metallic mirrors would roughly be the plasma frequency). Within the strict dipole approximation, we therefore wrongly discard all modes with 2π/LM ≤ q∥ ≤ qp from the light-matter coupling. Discarding these modes means that for an extended system the coupling to the majority of the modes in the cavity is not described and one there cannot expect the theory to yield physically correct results.

To formally define the cut-off in the in-plane direction, we note that while the cavity modifies the prominence of different qz, it has no direct impact on q∥. We can therefore uniformly sum the contribution of all the q∥ in the cavity such that q∥ ≤ qp. Because fixing the frequency means that \({q}_{\parallel }=\sqrt{{\left(\frac{\omega }{c}\right)}^{2}-{q}_{z}^{2}}\) and the cavity pins qz to qz,1, we can define the in-plane momentum cut-off as \({q}_{c,\parallel }^{{{\rm{lw}}}}=\sqrt{{\left(\frac{{\omega }_{p}}{c}\right)}^{2}-{q}_{z,1}^{2}}\). Note that for our cavity to only host a single mode, we should choose ωp = 2ω1 where \({\omega }_{1}=\frac{{q}_{z,1}}{c}\). This way, it appears that all modes with \(| {q}_{\parallel }| \in [0,\sqrt{3}{q}_{z,1}]\) have to be counted in the coupling. Taking into account that the spacing between photon modes is set by the quantization-box size L, we get that the number of photon modes l∥ is given by

where Δq = (2π)2/A2 is the area of each momentum grid element. Inserting into Eq. (16), we see that the quantization-box size L does not change the strength of the in-plane cavity coupling. Instead, by increasing L we merely find more and more modes carrying less and less individual weight such that we have a well-defined continuum limit. The same holds true also for the out-of-plane modes.

The Out-of-Plane cut-off

As discussed in the “collective canonical transformation” subsection above, the sum over modes in the out-of-plane direction is set by the width of the mode function with respect to qz, i.e., γ. In the Fabry-Pérot cavity description used in this work, this can be calculated once the reflectivity of the mirror is defined. This is thus a cavity specific quantity. Specifically, for relatively large mirror reflectivity where the individual modes of the Fabry-Pérot cavity can be resolved, we can meaningfully approximate γ as99,

where the cavity finesse is \({{\mathcal{F}}}=-\frac{2\pi }{\ln (| r{| }^{4})}\). The value of γ is in turn, related to the number of modes lz by

With the last relation we have fully connected the light-matter coupling parameters in the effective-mode theory to the specific characteristics of the cavity device. Together with the in-plane coupling we find that in Eq. (16) the coupling becomes independent of the quantization volume V = L3. We note that Eq. (19) suggests that the light-matter coupling formally vanishes when r → 1 and in turn \({{\mathcal{F}}}\to \infty\). However, at r → 1, Aeff,λ is also divergent and so one needs to take this limit carefully.

The results obtained above are specific to the Fabry-Pérot cavity, however, they highlight the importance of light and matter length scales and mirror characteristics when defining the problem for the coupled system.

The bulk limit of the light-matter coupling

While already hinted at in the previous section, it is worth explicitly discussing what the size scaling of the effective Hamiltonian is, and its consequences on how the bulk limit for a coupled cavity-matter system should be understood. In particular, we see from Eqs. (17)-(19) that both in the paramagnetic and the diamagnetic term the dependence on the quantization box volume disappears since l∥lz ~ V. Inserting the expressions for lz and l∥ we find an effective cavity field strength,

We thus arrive at an expression for the coupling strength of the effective single mode in the Fabry-Perot cavity which has no dependence on the volume of the quantization box. The only dependence on the system size left is in number of matter particles which is encoded in the operators \({\hat{P}}_{{{\rm{el}}}}\) and \({\hat{N}}_{{{\rm{el}}}}\). These operators scale with the size of the electronic system, and the importance of these terms scale in the same fashion as the Hel term when the size of the matter is increased (as explicitly shown in Supplementary note 5). This implies that the effect of the light-matter coupling will not vanish for the matter side of the problem. On the other hand, from the point of view of the light, it becomes clear that if the size of the matter does not grow with the isotropic quantization box, the effect of the matter on the electromagnetic modes might become negligible over the full space and can only be relevant locally, where the cavity is placed. This should not come as surprise since in our setup the matter system is a “defect” from the point of view of the free space.

Eq. (20) further tells us that the cavity sets an effective, finite mode volume which is independent of the quantization volume,

This is noteworthy because it shows that even an open, unbounded cavity like the Fabry-Perot setup naturally sets a finite mode volume. This again emphasizes that the size of the quantization box is an arbitrary length scale that does not affect the nature of the light-matter interaction. We can thus ultimately write,

Where the mode volume is the volume set by the cavity within which to consider the coupled extended light-matter system. The limit where the matter fills the entire in-plane mode-extension is thus the correct “bulk limit” for the coupled cavity-matter system. The practical consequences of such consideration are elaborated in the “Note on k-point convergence in ab initio simulations” subsection below.

As discussed in Supplementary note 1, the emergence of a finite mode volume can be qualitatively understood from classical arguments in terms of the longest in-plane length over which the cavity can be expected to mediate a meaningful interaction between two points. Although it is a subject of future investigations, we expect that for a cavity with intrinsic material losses at equilibrium (for which photons cannot actually be dissipated) that the amount of modes counted in the collective canonical transformation should be reduced. Thus, intrinsic losses of the cavity should renormalize the above effective volume and lower the effective light-matter coupling strength.

That the effective in-plane area appearing in the coupling of the 2D material and cavity is finite is critical, because QED in general, and in the LWA in particular, is known to exhibit Landau poles. A Landau pole is the largest energy for which a particular version of QED (here PF theory in the LWA) makes sense and it reflects the fact that QED cannot represent all scales simultaneously105,106,107,108. The Landau pole can be reached in one of two ways: Either by including arbitrarily high photon frequencies, or by increasing the number of particles in the system. It is therefore critical that the theory itself sets a finite length scale within which the light-matter coupling should be considered.

We finally note that our theory becomes ambiguous when r → 1. Here, lz → 0 and Aeff,λ becomes divergent. This problem reflects that we cannot unambiguously connect isotropic (all directions are the same) and homogeneous (all points are equivalent) free space to the anisotropic and inhomogeneous perfectly reflecting Fabry-Pérot case.

Strength of the effective mode parameter

Following the definitions derived so far, we can explicitly evaluate the value of the aeff parameters that should be used when setting up the effective few-mode Hamiltonian for the light-matter coupled system. The light blue line in Fig. 3a shows the effective coupling strength for the s-polarized mode, and the dashed purple line shows the fundamental cavity frequency, as a function of Lc for a fixed mirror reflectivity of 0.99. It can be seen that aeff,λ ∝ ωc. This connection is fixed by the geometrically determined resonance condition of the Fabry-Pérot cavity. It is in agreement with the fact that the enhancement of the electromagnetic density of states in the Fabry-Pérot cavity is scale invariant if the frequency dependence of the mirror properties, in the range of the resonance, can be neglected109. Because the effective coupling strength scales linearly with ωc, the ratio aeffλ/ωc will be scale invariant. In Fig. 3(b), we therefore provide aeffλ/ωc as a function of mirror reflectivity. From this plot, one can derive the effective single-mode coupling strength for any Fabry-Pérot cavity setup after specifying its mirror reflectivity and fundamental cavity frequency.

In Fig. 3(b), we provide aeff,s/ωc both with and without the removal of the free-space contribution, as defined in “The long wavelength approximation for the coupled light-matter system” subsection in the “Methods” section. We observe that the scaling of the coupling strength with the mirror reflectivity is qualitatively different in the two cases. We attribute this difference to the fact that as r → 0, the mode width γ diverges. When free space is removed, this is not a problem because \(| {\bar{R}}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },s,{q}_{z},F}|\) vanishes for r → 0. However, with the free-space contribution included, \(| {R}_{{{{\bf{q}}}}_{\parallel },s,{q}_{z},F}|\) goes to 1, and this means that we are averaging over a wider and wider region of qz. Since all contributions have a finite weight we obtain a divergence. We further note that for r → 1, both cases meet. At this point, the cavity becomes completely sealed off from its surroundings and the remaining free-space contribution becomes negligibly small relative to the cavity-enhanced contribution. The removal of free space in the perfectly reflecting cavity limit therefore interestingly does not significantly affect the effective coupling strength. The above discussion highlights the importance of properly removing the contribution from the free-space modes in general (not perfectly reflecting) cavity setups.

Note on k-point convergence in ab initio simulations

The existence of a maximum effective interaction volume/area has practical implications for electronic k-point sampling in numerical calculations. The density of k-points is a key convergence metric in ab initio simulations110,111 Intuitively, decreasing Δk, i.e., the k-spacing, is equivalent to increasing the number of unit cells in the crystal and hence the extension of the material coupled coherently to the cavity. As the discussion above shows, this should only be done until the area of the material is equal to the effective mode area. In other words, the k-point density can be freely increased as long as \(\Delta k \, \gg \, \frac{2\pi }{{S}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}^{1/2}}\).

We note that for an optical cavity with resonances in the visible and near infrared regions, Lc ~ 300 nm − 2.5 μm, \(\sqrt{{{\mathcal{F}}}}\simeq 1\) for even modest reflectivities of around r = 0.2 and this tells us that the characteristic cavity coupling length is at least on the order of Lc (see Supplementary Fig. S.4 in the Supplementary note 1). In practice, very few ab initio calculations use such a dense k-point sampling before convergence is reached, and \(\Delta k \, \gg \, \frac{2\pi }{{S}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}^{1/2}}\) is thus naturally fulfilled in most practical simulations. Despite this, it is worth briefly discussing what happens when \(\Delta k \, \lesssim \, \frac{2\pi }{{S}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}^{1/2}}\). In this case, the extension of the material becomes bigger than the characteristic cavity length \({S}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}^{1/2}\) which defines the maximal length between two points that can be coupled by cavity photons. The “extra” matter should hence not contribute to increasing the coupling, which is not apparent in Eq. (16). The key observation to recover the appropriate physical behavior is that in Eq. (16) the number of photonic modes l∥ has to be redistributed among different electronic k-points. More specifically \({l}_{\parallel }\to {l}_{\parallel }\frac{{S}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}^{1/2}\Delta k}{2\pi }\). This redistribution of coupling weight is essentially in place to guarantee that the non-physical infinite-range interaction of the LWA is naturally cut-off by the characteristic cavity coupling length.

Conclusions

In this work, we have shown that even in an extended, unbounded electromagnetic environment, such as a Fabry-Pérot cavity, the volume over which the interaction of light and matter mediated by the cavity should be considered is finite. This finite interaction volume is large enough to treat matter in its bulk limit. We show that this is the limit that should be considered instead of the standard thermodynamic limit of photon-free solid-state physics, when assessing the scaling of the light-matter coupling with system size within QED. While such a limit is naturally described by the explicit inclusion of the multi-mode nature of the electromagnetic field in the coupled light-matter problem, here we have derived an effective few-mode description of the paradigmatic Fabry-Pérot-2D material system featuring the correct size scaling in the bulk limit and the simplicity of a few-mode theory. Our effective approach is non-perturbative and free from the double counting of the interaction of matter with the vacuum fluctuations of light already present in free space. We have derived our effective schemes according to the following steps: (i) The photonic modes of the Fabry-Pérot cavity were quantized in an isotropic space in order to be consistent with the standard quantum-electrodynamical description of free space. (ii) We removed the spurious free-space double-counting by identifying and subtracting the contribution of the cavity in the limit of mirrors with zero reflectivity. (iii) From the reflectivity of the cavity mirrors and by employing the long wavelength approximation, we determined the relevant interaction length scales to define the full Hamiltonian of the effective few-mode theory.

With light-matter coupling remaining finite in the bulk limit, it is possible to expect the cavity to have an effect on the ground state properties of an extended system. Our effective Hamiltonian can be used as a computationally convenient starting point for refined many-body methods. On the one hand, quantum-electrodynamical density-functional theory (QEDFT)53,85,112,113,114, and its recently developed functionals54,55,57,58,59, can be augmented with a realistic few-mode description of the quantum electromagnetic environment without an increase in its computational cost. On the other hand, within many-body perturbation theory, the effective Hamiltonian introduces a simplified starting point to build an effective perturbation theory by eliminating the explicit consideration of photon momentum degrees of freedom. It will be the subject of future work to show how starting a perturbation theory from the original multi-mode Pauli-Fierz Hamiltonian and following the same approximations motivated by the long wavelength assumption could lead to an equivalent simplified effective perturbation theory. Further effort should then be devoted to delineating the span of correlation functions that can be calculated with such a theory.

To conclude, our work represents a step towards the first principles simulation of realistic cavity-material engineering while providing an intuitive description of the degrees-of-freedom at play in interacting extended light-matter systems.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used to generate the results of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Carusotto, I. & Ciuti, C. Quantum fluids of light. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 299–366 (2013).

Basov, D. N., Asenjo-Garcia, A., Schuck, P. J., Zhu, X. & Rubio, A. Polariton panorama. Nanophotonics 10, 549–577 (2020).

Bloch, J., Cavalleri, A., Galitski, V., Hafezi, M. & Rubio, A. Strongly correlated electron–photon systems. Nature 606, 41–48 (2022).

Hübener, H., Boström, E. V., Claassen, M., Latini, S. & Rubio, A. Quantum materials engineering by structured cavity vacuum fluctuations. Mater. Quantum Technol. 4, 023002 (2024).

Forn-Díaz, P., Lamata, L., Rico, E., Kono, J. & Solano, E. Ultrastrong coupling regimes of light-matter interaction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 025005 (2019).

Hagenmüller, D., De Liberato, S. & Ciuti, C. Ultrastrong coupling between a cavity resonator and the cyclotron transition of a two-dimensional electron gas in the case of an integer filling factor. Phys. Rev. B 81, 235303 (2010).

Smolka, S. et al. Cavity quantum electrodynamics with many-body states of a two-dimensional electron gas. Science 346, 332–335 (2014).

Todorov, Y. Dipolar quantum electrodynamics of the two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125409 (2015).

Paravicini-Bagliani, G. L. et al. Magneto-transport controlled by Landau polariton states. Nat. Phys. 15, 186–190 (2018).

Ravets, S. et al. Polaron Polaritons in the Integer and Fractional Quantum Hall Regimes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 057401 (2018).

Knüppel, P. et al. Nonlinear optics in the fractional quantum hall regime. Nature 572, 91–94 (2019).

Rokaj, V., Penz, M., Sentef, M. A., Ruggenthaler, M. & Rubio, A. Quantum electrodynamical bloch theory with homogeneous magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 047202 (2019).

Cortese, E., Carusotto, I., Colombelli, R. & Liberato, S. D. Strong coupling of ionizing transitions. Optica 6, 354–361 (2019).

Cortese, E. et al. Excitons bound by photon exchange. Nat. Phys. 17, 31–35 (2021).

Rokaj, V., Ruggenthaler, M., Eich, F. G. & Rubio, A. Free electron gas in cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Res 4, 013012 (2022).

Keller, J. et al. Landau polaritons in highly nonparabolic two-dimensional gases in the ultrastrong coupling regime. Phys. Rev. B 101, 075301 (2020).

Rokaj, V., Penz, M., Sentef, M. A., Ruggenthaler, M. & Rubio, A. Polaritonic hofstadter butterfly and cavity control of the quantized hall conductance. Phys. Rev. B 105, 205424 (2022).

Appugliese, F. et al. Breakdown of topological protection by cavity vacuum fields in the integer quantum hall effect. Science 375, 1030–1034 (2022).

Enkner, J. et al. Tunable vacuum-field control of fractional and integer quantum hall phases. Nature 641, 884–889 (2025).

De Bernardis, D. et al. Magnetic-field-induced cavity protection for intersubband polaritons. Phys. Rev. B 106, 224206 (2022).

Arwas, G. & Ciuti, C. Quantum electron transport controlled by cavity vacuum fields. Phys. Rev. B 107, 045425 (2023).

Schlawin, F., Cavalleri, A. & Jaksch, D. Cavity-Mediated Electron-Photon Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 133602 (2019).

Cotleţ, O., Zeytinoglu, S., Sigrist, M., Demler, E. & Imamoglu, A. Superconductivity and other collective phenomena in a hybrid bose-fermi mixture formed by a polariton condensate and an electron system in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054510 (2016).

Sentef, M. A., Ruggenthaler, M. & Rubio, A. Cavity quantum-electrodynamical polaritonically enhanced electron-phonon coupling and its influence on superconductivity. Sci. Adv. 4, 11 (2018).

Lu, I.-T. et al. Cavity-enhanced superconductivity in mgb2 from first-principles quantum electrodynamics (qedft). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2415061121 (2024).

Hübener, H. et al. Engineering quantum materials with chiral optical cavities. Nat. Mater. 20, 438–442 (2021).

Wang, X., Ronca, E. & Sentef, M. A. Cavity quantum electrodynamical Chern insulator: Towards light-induced quantized anomalous hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 99, 235156 (2019).

Dag, C. B. & Rokaj, V. Engineering topology in graphene with chiral cavities. Phys. Rev. B 110, L121101 (2024).

Ashida, Y. et al. Quantum electrodynamic control of matter: cavity-enhanced ferroelectric phase transition. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041027 (2020).

Latini, S. et al. The ferroelectric photo-groundstate of SrTiO3: Cavity materials engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2105618118 (2021).

Andolina, G. M. et al. Amperean superconductivity cannot be induced by deep subwavelength cavities in a two-dimensional material. Phys. Rev. B 109, 104513 (2024).

Mazza, G. & Georges, A. Superradiant Quantum Materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 017401 (2019).

Andolina, G. M., Pellegrino, F. M., Giovannetti, V., Macdonald, A. H. & Polini, M. Cavity quantum electrodynamics of strongly correlated electron systems: A no-go theorem for photon condensation. Phys. Rev. B 100, 121109 (2019).

Andolina, G. M., Pellegrino, F. M., Giovannetti, V., Macdonald, A. H. & Polini, M. Theory of photon condensation in a spatially varying electromagnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 102, 125137 (2020).

Garcia-Vidal, F. J., Ciuti, C. & Ebbesen, T. W. Manipulating matter by strong coupling to vacuum fields. Science 373, eabd0336 (2021).

Jarc, G. et al. Cavity-mediated thermal control of metal-to-insulator transition in 1t-tas2. Nature 622, 487–492 (2023).

Sidler, D., Ruggenthaler, M., Schäfer, C., Ronca, E. & Rubio, A. A perspective on ab initio modeling of polaritonic chemistry: The role of non-equilibrium effects and quantum collectivity. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 230901 (2022).

Sidler, D., Ruggenthaler, M. & Rubio, A. Numerically exact solution for a real polaritonic system under vibrational strong coupling in thermodynamic equilibrium: loss of light-matter entanglement and enhanced fluctuations. J. Chem. Theo. Comp. 19, 8801–8814 (2023).

Ruggenthaler, M., Sidler, D. & Rubio, A. Understanding polaritonic chemistry from ab initio quantum electrodynamics. Chemical Reviews 123, 11191–11229 (2023).

Schlawin, F., Kennes, D. M. & Sentef, M. A. Cavity quantum materials. Appl Phys. Rev. 9, 011312 (2022).

Ebbesen, T. W., Rubio, A. & Scholes, G. D. Introduction: polaritonic chemistry (2023).

Lu, I.-T. et al. Cavity engineering of solid-state materials without external driving. Advances in Optics and Photonics 17, 441–525 (2025).

Haugland, T. S., Ronca, E., Kjønstad, E. F., Rubio, A. & Koch, H. Coupled Cluster Theory for Molecular Polaritons: Changing Ground and Excited States. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041043 (2020).

Mordovina, U. et al. Polaritonic coupled-cluster theory. Phys. Rev. Res 2, 023262 (2020).

Haugland, T. S., Schäfer, C., Ronca, E., Rubio, A. & Koch, H. Intermolecular interactions in optical cavities: An ab initio QED study. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 094113 (2021).

Liebenthal, M. D., Vu, N. & DePrince, A. E. Equation-of-motion cavity quantum electrodynamics coupled-cluster theory for electron attachment. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 054105 (2022).

Foley, J. J., McTague, J. F. & DePrince, A. E. Ab initio methods for polariton chemistry. Chem. Phys. Rev. 4, 041301 (2023).

Riso, R. R., Grazioli, L., Ronca, E., Giovannini, T. & Koch, H. Strong coupling in chiral cavities: nonperturbative framework for enantiomer discrimination. Phys. Rev. X 13, 031002 (2023).

Romanelli, M. et al. Effective single-mode methodology for strongly coupled multimode molecular-plasmon nanosystems. Nano Lett. 23, 4938–4946 (2023).

Pavosevic, F., Smith, R. L. & Rubio, A. Cavity click chemistry: Cavity-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 10184–10188 (2023).

Datta, S. N. Coupled cluster theory based on quantum electrodynamics: Physical aspects of closed shell and multi-reference open shell methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.06392 (2024).

Vu, N. et al. Cavity quantum electrodynamics complete active space configuration interaction theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput 20, 1214–1227 (2024).

Ruggenthaler, M. et al. Quantum-electrodynamical density-functional theory: Bridging quantum optics and electronic-structure theory. Phys. Rev. A 90, 012508 (2014).

Pellegrini, C., Flick, J., Tokatly, I. V., Appel, H. & Rubio, A. Optimized effective potential for quantum electrodynamical time-dependent density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 093001 (2015).

Flick, J., Schäfer, C., Ruggenthaler, M., Appel, H. & Rubio, A. Ab initio optimized effective potentials for real molecules in optical cavities: Photon contributions to the molecular ground state. ACS photonics 5, 992–1005 (2018).

Ruggenthaler, M., Tancogne-Dejean, N., Flick, J., Appel, H. & Rubio, A. From a quantum-electrodynamical light–matter description to novel spectroscopies. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 1–16 (2018).

Flick, J., Welakuh, D. M., Ruggenthaler, M., Appel, H. & Rubio, A. Light–matter response in nonrelativistic quantum electrodynamics. ACS photonics 6, 2757–2778 (2019).

Schäfer, C., Buchholz, F., Penz, M., Ruggenthaler, M. & Rubio, A. Making ab initio qed functional (s): Nonperturbative and photon-free effective frameworks for strong light–matter coupling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2110464118 (2021).

Flick, J. Simple exchange-correlation energy functionals for strongly coupled light-matter systems based on the fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 143201 (2022).

Lu, I.-T. et al. Electron-photon exchange-correlation approximation for quantum-electrodynamical density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. A 109, 052823 (2024).

Svendsen, M. K., Thygesen, K. S., Rubio, A. & Flick, J. Ab initio calculations of quantum light–matter interactions in general electromagnetic environments. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 926–936 (2024).

Svendsen, M. K. et al. Combining density functional theory with macroscopic QED for quantum light-matter interactions in 2D materials. Nat. Commun. 12, 2778 (2021).

Scheel, S. & Buhmann, S. Y. Macroscopic qed-concepts and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:0902.3586 (2009).

Buhmann, S. Y., Butcher, D. T. & Scheel, S. Macroscopic quantum electrodynamics in nonlocal and nonreciprocal media. N. J. Phys. 14, 083034 (2012).

Buhmann, S. Y. Dispersion Forces I: Macroscopic quantum electrodynamics and ground-state Casimir, Casimir–Polder and van der Waals forces, 247 (Springer, 2013).

Latini, S., Ronca, E., Giovannini, U. D., Hübener, H. & Rubio, A. Cavity Control of Excitons in Two-Dimensional Materials. Nano Lett. 19, 3473–3479 (2019).

Latini, S. et al. Phonoritons as Hybridized Exciton-Photon-Phonon Excitations in a Monolayer h-BN Optical Cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 227401 (2021).

Todorov, Y. & Sirtori, C. Intersubband polaritons in the electrical dipole gauge. Phys. Rev. B—Condens Matter Mater. Phys. 85, 045304 (2012).

Amelio, I., Korosec, L., Carusotto, I. & Mazza, G. Optical dressing of the electronic response of two-dimensional semiconductors in quantum and classical descriptions of cavity electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. B 104, 235120 (2021).

Lenk, K., Li, J., Werner, P. & Eckstein, M. Dynamical mean-field study of a photon-mediated ferroelectric phase transition. Phys. Rev. B 106, 245124 (2022).

Mandal, A. et al. Microscopic theory of multimode polariton dispersion in multilayered materials. Nano Lett. 23, 4082–4089 (2023).

Taylor, M. A., Weight, B. M. & Huo, P. Reciprocal asymptotically decoupled hamiltonian for cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. B 109, 104305 (2024).

Thomas, A. et al. Exploring superconductivity under strong coupling with the vacuum electromagnetic field. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.01459 (2019).

Glauber, R. J. & Lewenstein, M. Quantum optics of dielectric media. Phys. Rev. A 43, 467–491 (1991).

Hughes, K. H., Christ, C. D. & Burghardt, I. Effective-mode representation of non-markovian dynamics: A hierarchical approximation of the spectral density. i. application to single surface dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 024109 (2009).

Tamascelli, D., Smirne, A., Huelga, S. F. & Plenio, M. B. Nonperturbative treatment of non-markovian dynamics of open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 030402 (2018).

De Bernardis, D., Pilar, P., Jaako, T., De Liberato, S. & Rabl, P. Breakdown of gauge invariance in ultrastrong-coupling cavity qed. Phys. Rev. A 98, 053819 (2018).

Di Stefano, O. et al. Resolution of gauge ambiguities in ultrastrong-coupling cavity quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Phys. 15, 803–808 (2019).

Dmytruk, O. & Schiró, M. Gauge fixing for strongly correlated electrons coupled to quantum light. Phys. Rev. B 103, 075131 (2021).

Schäfer, C., Flick, J., Ronca, E., Narang, P. & Rubio, A. Shining light on the microscopic resonant mechanism responsible for cavity-mediated chemical reactivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–9 (2022).

Spohn, H.Dynamics of charged particles and their radiation field (Cambridge university press, 2004).

Buhmann, S. Y. & Welsch, D.-G. Dispersion forces in macroscopic quantum electrodynamics. Prog. quantum Electron 31, 51–130 (2007).

Thirring, W.Quantum mathematical physics: atoms, molecules and large systems (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Greiner, W. et al. Field quantization (Springer Science & Business Media, 1996).

Jestädt, R., Ruggenthaler, M., Oliveira, M. J. T., Rubio, A. & Appel, H. Light-matter interactions within the ehrenfest-maxwell-pauli-kohn-sham framework: fundamentals, implementation, and nano-optical applications. Adv. Phys. 68, 225–333 (2019).

Schäfer, C., Ruggenthaler, M., Rokaj, V. & Rubio, A. Relevance of the quadratic diamagnetic and self-polarization terms in cavity quantum electrodynamics. ACS photonics 7, 975–990 (2020).

Stockman, M. I. Nanoplasmonics: past, present, and glimpse into future. Opt. express 19, 22029–22106 (2011).

Kuznetsov, A. I., Miroshnichenko, A. E., Brongersma, M. L., Kivshar, Y. S. & Luk’yanchuk, B. Optically resonant dielectric nanostructures. Science 354, aag2472 (2016).

Mortensen, N. A., Raza, S., Wubs, M., Søndergaard, T. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. A generalized non-local optical response theory for plasmonic nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 5, 3809 (2014).

Svendsen, M., Wolff, C., Jauho, A.-P., Mortensen, N. A. & Tserkezis, C. Role of diffusive surface scattering in nonlocal plasmonics. J. Phys: Condens Matter 32, 395702 (2020).

Al-Ani, I. A. M. et al. Recent advances on strong light-matter coupling in atomically thin TMDC semiconductor materials. J. Opt. 24, 053001 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Strong exciton-plasmon coupling in mos2 coupled with plasmonic lattice. Nano Lett. 16, 1262–1269 (2016).

Zhang, L., Gogna, R., Burg, W., Tutuc, E. & Deng, H. Photonic-crystal exciton-polaritons in monolayer semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 9, 713 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Hybrid exciton-plasmon-polaritons in van der waals semiconductor gratings. Nat. Commun. 11, 3552 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Metasurface integrated monolayer exciton polariton. Nano Lett. 20, 5292–5300 (2020).

Baranov, D. G. et al. All-dielectric nanophotonics: the quest for better materials and fabrication techniques. Optica 4, 814–825 (2017).

Svendsen, M. K. et al. Computational discovery and experimental demonstration of boron phosphide ultraviolet nanoresonators. Adv. Optical Mater. 10, 2200422 (2022).

Sáez-Blázquez, R., De Bernardis, D., Feist, J. & Rabl, P. Can we observe nonperturbative vacuum shifts in cavity qed? Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 013602 (2023).

Saleh, B. E. & Teich, M. C. Fundamentals of photonics (John Wiley & sons, 2019).

Eckhardt, C. J. et al. Quantum floquet engineering with an exactly solvable tight-binding chain in a cavity. Commun. Phys. 5, 1–12 (2022).

Tichauer, R. H., Feist, J. & Groenhof, G. Multi-scale dynamics simulations of molecular polaritons: The effect of multiple cavity modes on polariton relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 154 (2021).

Berghuis, A. M. et al. Controlling exciton propagation in organic crystals through strong coupling to plasmonic nanoparticle arrays. ACS photonics 9, 2263–2272 (2022).

Xu, D. et al. Ultrafast imaging of polariton propagation and interactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 3881 (2023).

Balasubrahmaniyam, M. et al. From enhanced diffusion to ultrafast ballistic motion of hybrid light–matter excitations. Nat. Mater. 22, 338–344 (2023).

Berestetskii, V. B., Lifshitz, E. M. & Pitaevskii, L. P.Quantum Electrodynamics: Volume 4, 4 (Butterworth-Heinemann, 1982).

Göckeler, M. et al. Is there a landau pole problem in qed? Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4119–4122 (1998).

Gies, H. & Jaeckel, J. Renormalization flow of qed. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 110405 (2004).

Hainzl, C. & Seiringer, R. Mass renormalization and energy level shift in non-relativistic qed. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 6, 847–871 (2002).

Dutra, S. & Knight, P. Spontaneous emission in a planar fabry-pérot microcavity. Phys. Rev. A 53, 3587 (1996).

Martin, R. M. Electronic structure: basic theory and practical methods (Cambridge university press, 2020).

Enkovaara, J. et al. Electronic structure calculations with gpaw: a real-space implementation of the projector augmented-wave method. J. Phys: Condens matter 22, 253202 (2010).

Ruggenthaler, M. Ground-state quantum-electrodynamical density-functional theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:1509.01417 (2015).

Dreizler, R. M. & Gross, E. K.Density functional theory: an approach to the quantum many-body problem (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Ullrich, C. A.Time-Dependent Density-Functional Theory: Concepts and Applications https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199563029.001.0001 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Acknowledgements

C.S. acknowledges funding from the Horizon Europe research and innovation program of the European Union under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 101065117 and the Swedish Research Council (VR) through Grant No. 2016-06059. The Flatiron Institute is a division of the Simons Foundation. We acknowledge support from the Max Planck-New York City Center for Non-Equilibrium Quantum Phenomena. This work was supported by the Cluster of Excellence Advanced Imaging of Matter (AIM), Grupos Consolidados (IT1249-19), and SFB925. This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC-2024-SyG- 101167294; UnMySt We acknowledge support from the European Union Marie Sklodowska-Curie Doctoral Network SPARKLE grant No. 101169225.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K.S., M.R., A.R. and S.L. came up with the effective mode idea at the core of the manuscript. H.H., C.S. and M.E. actively participated in the development of the physics and scope of the manuscript. M.K.S. implemented the code and generated the results. S.L. generated the figures. S.L., M.R. and M.K.S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors participated in the refinement of the text.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Dominik Lentrodt and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Svendsen, M.K., Ruggenthaler, M., Hübener, H. et al. Effective equilibrium theory of quantum light-matter interaction in cavities for extended systems and the long wavelength approximation. Commun Phys 8, 425 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02365-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02365-x

This article is cited by

-

Cavity-QED-controlled two-dimensional Moiré excitons without twisting

Nature Communications (2025)