Abstract

Spin-triplet superconductivity is a key platform for topological quantum computing, yet its experimental realization and control in solid-state materials remain a significant challenge. For this purpose, we propose an ultrafast optical strategy to manipulate spin-triplet superconductivity by leveraging p-wave pairing instabilities in the extended Hubbard model, a framework applicable to transition-metal oxides. Utilizing Floquet engineering, we demonstrate that transient flipping of the effective spin-exchange interaction can enhance p-wave pairing correlations under linearly polarized optical pulses. Furthermore, we reveal that this emergent spin-triplet pairing in strongly correlated systems can be selectively switched by an orthogonal optical pulse. This work provides a pathway for stabilizing and controlling spin-triplet superconductivity in correlated materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin-triplet superconductivity is widely recognized as a promising avenue for topological quantum computing1,2, offering a robust platform for hosting non-Abelian excitations3,4,5. However, despite its theoretical appeal, experimental realization remains an ongoing challenge. Sr2RuO4 was long considered the leading candidate, particularly for a chiral p + ip pairing state6,7,8,9,10,11, but recent experimental findings have cast significant doubt on its pairing symmetry12,13,14. Other materials, such as UTe215,16, UPt317, and K2Cr3As318 have been proposed as potential candidates for spin-triplet superconductors, yet unambiguous experimental validation of spin-triplet pairing remain elusive.

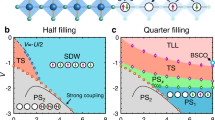

Beyond specific materials, theoretical and numerical studies have revealed that spin-triplet pairing can naturally emerge in strongly correlated models with mixed-sign interactions. In particular, the one-dimensional (1D) extended Hubbard model (EHM), where a repulsive on-site interaction U coexists with an attractive nearest-neighbor interaction V, has been shown to support nodal pairing symmetry. Under appropriate doping and parameter regimes, this model exhibits spin-triplet superconductivity19,20,21,22,23,24. Its extension to two dimensions (2D) further reveals robust spin-triplet pairing instability near quarter filling25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Although once treated as an artificial toy model, mixed-sign interactions have been experimentally identified in strongly correlated cuprates in quasi-1D thin films and single crystals32,33,34,35. In these systems, phonons are believed to mediate attractive interactions between nearest-neighbor electrons while preserving dominant on-site repulsion, leading to a scenario effectively described by the EHM36,37,38,39,40. Although further experimental validation is needed to quantify these interactions, such mechanisms may be broadly realized in Ruddlesden–Popper transition-metal oxides due to structural similarities, providing a promising route toward stabilizing spin-triplet pairing beyond quasi-1D materials.

Another challenge in harnessing spin-triplet superconductivity is achieving efficient and selective control over its order parameter. Recent time-dependent mean-field studies have proposed sophisticated strategies for manipulating multiple p-wave order parameters41, and inducing transitions between spin-singlet and triplet states42. In mean-field approximations, where quantum fluctuations are neglected, these approaches typically require carefully timed sequences of pump pulses with varying polarizations. In strongly correlated systems, light-induced superconductivity may be more directly accessible due to the interplay of competing orders and quantum fluctuations. Experimental evidences from cuprates and molecular crystals suggest that nonequilibrium optical excitation can dynamically alter superconducting states in correlated materials43,44,45,46,47,48.

Building on these developments, we propose a dynamical strategy to engineer spin-triplet pairing in strongly correlated systems with mixed-sign interactions. Specifically, we leverage the Floquet engineering of magnetic exchange interactions49,50 to analysis how a transient sign reversal of the exchange interaction along the pump polarization, when the pump laser is tuned near resonance [see Fig. 1]. Using time-dependent exact diagonalization simulations on a extended Hubbard model, we demonstrate the feasibility of selectively enhancing existing spin-triplet pairing correlations on ultrafast timescales. A subsequent pulse with an orthogonal polarization can further manipulate the order parameter, enabling controlled switching between pairing symmetries. This approach paves the way for designing and dynamically controlling spin-triplet superconductivity in strongly correlated materials.

a Correlated electrons on a 2D lattice, characterized by hopping t, on-site Coulomb interaction U, and nearest-neighbor interaction V. An external pump pulse transiently induces a ferromagnetic spin-exchange interaction along the pump polarization direction. b Bloch sphere representation of pairing correlations. c Schematic illustrating the redistribution of the pairing correlations across the Bloch sphere, following an optical pump and a subsequent second pump.

Results

Light-enhanced spin-triplet pairing correlations

To investigate spin-triplet pairing instabilities in strongly correlated systems, we focus on a quarter-filled (i.e., 50% hole-doped) EHM on a square lattice, which serves as a prototypical model for transition-metal oxides. Following Eq. (6) in “Methods”, the EHM incorporates a repulsive on-site interaction U and an attractive nearest-neighbor interaction V. Previous studies have demonstrated that such a model supports strong spin-triplet pairing instabilities19,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,28, confirmed through many-body numerical simulations24,29,30,31. Here, we adopt U = 8th and V = −th as model parameters in Eq. (6), consistent with experimental estimates for cuprates32,33,34.

The spin-triplet pairing instabilities are characterized by the three-fold pairing operators for each spatial symmetry. For example, the px-wave pairing operator is:

where ci,σ represents the annihilation operator for an electron with spin σ at site i. Analogous operators for the py, px ± py, and px ± ipy pairing channels are defined in the Supplementary Note 1. For any many-body state \(\left\vert \psi \right\rangle\), the p-wave pairing correlations are computed as:

where α labels the pairing symmetry and the pairing operator is averaged over the triplet states \({\Delta }_{{{\bf{i}}}}^{{p}_{\alpha }}=({\Delta }_{{{\bf{i}}},1}^{{p}_{\alpha }}+{\Delta }_{{{\bf{i}}},0}^{{p}_{\alpha }}+{\Delta }_{{{\bf{i}}},-1}^{{p}_{\alpha }})/\sqrt{3}\). These pairing correlations can be represented as vectors on the Bloch sphere (see Fig. 1b), providing a geometric perspective on the interplay between different pairing symmetries. In this work, we focus on analyzing short-range pairing correlations within finite clusters rather than long-range order, the latter of which remains challenging to establish in 2D systems due to strong quantum fluctuations.

At equilibrium, the p-wave pairing correlations, which are isotropic across all six orientations, exhibit a pronounced hump for the interaction parameters adopted in this study (U = 8th and V = −th), signaling strong spin-triplet pairing instabilities29. Starting from this equilibrium state, we investigate the nonequilibrium dynamics of p-wave pairing correlations induced by an external optical excitation. The time-dependent wavefunction \(\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle\) is obtained by evolving the system under a time-dependent Hamiltonian, where the external vector potential A(t) is incorporated via the Peierls substitution (see “Methods”). The instantaneous pairing correlation Φα(t) is then calculated by substituting \(\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle\) into Eq. (2). For the single-pump setup considered in this section, the external light pulse is usually modeled as a Gaussian envelope:

where A0, Ω, and \({\hat{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{{{\rm{pol}}}}\) represent the pump amplitude, frequency, and polarization, respectively.

Without loss of generality, we focus on a single x-polarized laser pulse, \({\hat{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{{{\rm{pol}}}}=\hat{x}\), to explore the anisotropic response of pairing correlations [Because the cluster preserves the C4 symmetry, the direction of linear pump polarization does not introduce any directional bias in the analysis. In other words, switching the pump polarization from x to y leads to a straightforward interchange of the Φx and Φy outcomes.]. In typical pump-probe experiments, phase coherence between the pump and probe lasers is often not strictly maintained, leading to phase-averaged measurements that suppress phase-locked oscillations. To account for this, we evaluate the phase-averaged pairing correlation as ∑nΦα(t; ϕ = ϕn)/n, with a detailed analysis provided in the Supplementary Note 2. For clarity, all figures in the main text present results with ϕ = 0, as the phase slightly influences the amplitude of Φα(t) without qualitatively altering its overall temporal evolution.

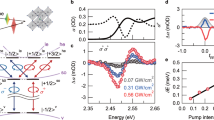

The dynamics of spin-triplet pairing correlations under an x-polarized laser pulse with Ω = 9.2th are presented in Fig. 2a–c. A prominent feature of this response is the pronounced oscillatory behavior observed in Φx(t) and Φy(t), which exhibit a striking anti-phase relationship both during and after the pump pulse. This anti-phase behavior reflects an intrinsic competition between these orthogonal pairing channels. While increasing the pump strength enhances the oscillation amplitude, the underlying anti-phase structure remains unchanged, indicating the robustness of this dynamical competition. As a result, the pairing channel aligned with the pump field (e.g., px) is transiently enhanced at specific oscillation phases, such as near \(t=10{t}_{h}^{-1}\), at the cost of significantly suppressing its orthogonal counterpart (e.g., py).

Dynamics of pairing correlations in the a px, b py, and c px + py channels, in response to a Ω = 9.2th pump pulse with amplitudes A0 = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8, respectively. The top inset displays the time-dependent vector potential of the pump field. d Distribution of pairing correlations projected onto the equatorial plane of the Bloch sphere at four representative time points (marked by gray dashed lines in the inset of (a)). Colors from light to dark indicate increasing pump strengths from A0 = 0.2–0.8. The arrows at the center indicate the magnitude of Φx−Φy for each pump strength.

In contrast, other orthogonal pairs of pairing channels, such as Φx ± y(t), exhibit a different dynamical response [see Fig. 2c]. These channels undergo an abrupt suppression during the pump pulse and show minimal oscillatory behavior. Instead, their post-pump evolution reflects an averaged behavior of Φx(t) and Φy(t), suggesting a net suppression of pairing correlations, likely driven by photo-induced carrier screening effects51. The maximum enhancement of Φx(t) follows a non-monotonic dependence on pump strength, dictated by the competing effects of light-enhanced px pairing and the overall suppression of pairing correlations.

To further elucidate the anisotropic response of laser-induced p-wave pairing correlations, we map the pairing correlations onto the Bloch sphere at four representative time points: \(t=-8{t}_{h}^{-1}\), \(-2{t}_{h}^{-1}\), 0 and \(7{t}_{h}^{-1}\) [see Fig. 2d]. At equilibrium, pairing correlations are isotropic without any symmetry breaking. However, once a linearly polarized pump is applied, this symmetry is broken, causing the Bloch sphere to shift preferentially toward the px direction while suppressing the py component. This asymmetry becomes more pronounced with higher pump fluence, indicating a stronger laser-induced anisotropy. After the pump, the Bloch sphere undergoes continuous oscillations along the horizontal axis, yet Φx(t) consistently dominates over Φy(t). Notably, the center of the Bloch sphere does not cross the origin, as shown by the directional arrows in Fig. 2d, reflecting sustained px channel dominance triggered by the pump. The first maximal imbalance occurs near \(t \sim \sigma =2.5{t}_{h}^{-1}\), with slight variations depending on the pump amplitude. Since the correlated system is closed and lacks dissipation, the undamped laser energy drives continuous Bloch sphere oscillations over extended timescales lie within the pre-thermal plateau52,53, ensuring the persistence of the px dominance and enhancement of spin-triplet pairing after the pump pulse ends54,55.

Floquet engineering of anisotropic spin interactions

The selective enhancement of spin-triplet pairing correlations reflects an underlying control mechanism mediated by anisotropic spin interactions. To examine this mechanism, we simulate the nonequilibrium dynamics of Φx(t) and Φy(t) across a broad range of pump amplitudes and frequencies. To isolate light-induced modifications, we focus on the differential pairing correlation as ΔΦα(t) = Φα(t) − Φα(t = −∞) by offsetting with their equilibrium values. Figure 3a presents ΔΦx and ΔΦy at the pump pulse center (t = 0). Although increasing the pump amplitude generally suppresses the pairing correlations across all channels due to photocarrier screening, a pronounced enhancement of Φx emerges near Ω ≈ U = 8th, persisting across all fluences. We further investigate light-induced changes in ΔΦx(t) and ΔΦy(t) at \(t=10{t}_{h}^{-1}\) (see Fig. 3b), corresponding to the first anti-phase oscillation peak observed in Fig. 2. In both time points, two distinct frequency regimes emerge: a primary enhancement peak near Ω ~ 9th = U − V, consistent with our earlier findings in Fig. 2, and a secondary, narrower peak around Ω ~ 5 th. In contrast, ΔΦy(t) is suppressed in all pump conditions.

a Pump-induced changes in px (upper) and py (lower) pairing correlations at t = 0 (center of the pump field), relative to their equilibrium values, plotted as a function of pump frequency and amplitude. The two distinct regimes of px enhancement correspond to the single- and two-photon resonances. b Same as (a) but evaluated at \(t=10{t}_{h}^{-1}\).

The observed frequency-dependent enhancement of spin-triplet pairing correlations in the dynamical simulation of the EHM model can be attributed to Floquet engineering of effective spin-exchange interactions. In the presence of a periodic pump field, the transient system can be approximated by an effective Floquet Hamiltonian, treating the laser field as periodic53,56,57. Within this framework, the monochromatic light field couples to the electronic states, creating a series of photon-dressed states with energy levels spaced by multiples of the pump frequency Ω58. In strongly correlated systems, such photon dressing significantly modifies the intermediate states involved in spin superexchange process49,50. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, an intermediate state with double occupancy transforms into photon-dressed states under periodic driving, effectively renormalizing the spin superexchange interactions. Consequently, the Floquet-engineered spin exchange interaction becomes49,50:

where \({{{\mathcal{J}}}}_{m}(x)\) is the mth-order Bessel function of the first kind, describing contributions from processes involving m photons with energy Ω. Here, Eint represents the energy cost of creating a doubly occupied intermediate state relative to the singlet ground state. Crucially, the effective exchange interaction \({J}_{\alpha }^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) depends on the projection \({A}_{0}\cdot {\hat{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{\alpha }\) of the pump field along the exchange pathway, allowing dynamic control over both the magnitude and the sign of the interaction by tuning the pump polarization, amplitude, and frequency59.

a Schematic depiction of the spin exchange process in a Floquet system. The effective superexchange interaction J originates from second-order virtual hopping processes that involve multiple intermediate states, with their energies set by the equilibrium intermediate-state energy Eint and integer multiples of the pump frequency Ω. b Effective spin exchange interaction \({J}_{\alpha }^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) at a transient state, calculated using the Floquet theory, as a function of the pump frequency Ω. The red and blue regions indicate ferromagnetism (FM) and antiferromagnetism (AFM) exchange interactions, respectively. The solid lines correspond to calculations assuming homogeneous electron occupations, while the translucent extended \({J}_{\alpha }^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) resonance area due to occupation imbalances, as illustrated in c. The single- and two-photon resonances are determined by the variation of FM regions. c Schematic illustration of various intermediate state configurations with distinct electron occupations and their corresponding intermediate-state energies Eint.

In contrast to the Hubbard model, where the intermediate-state energy is determined by U alone49,50, the EHM with on-site U and nearest-neighbor V results in an intermediate-state energy Eint ≈ U − V, setting the single-photon resonance at Ω ≈ 9th in Eq. (4). Figure 4b presents the simulated spin exchange for A0 = 0.4 with m truncated to ±50, where \({J}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) exhibits strong pump frequency dependence. Away from resonance, the Floquet-engineered effective \({J}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) recovers its equilibrium antiferromagnetic (AFM) exchange interaction \(J \sim 4{t}_{h}^{2}/{E}_{{{\rm{int}}}} \sim 0.5{t}_{h}\). However, as Ω approaches resonance with Eint, \({J}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) undergoes significant renormalization. Notably, when Ω slightly exceeds Eint, the exchange interaction undergoes a sign reversal, transitioning from AFM to ferromagnetic (FM) (red-shaded region). This sign flip is crucial because AFM exchange favors spin-singlet pairing, while FM exchange supports spin-triplet pairing, thereby explaining the enhancement of Φx for Ω ≳ Eint. Moreover, the Floquet effect is polarization-selective: the exchange interaction along the y direction (\({J}_{y}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\)) remains largely unaffected due to its orthogonality with the pump polarization, leading to the observed anisotropic pairing correlations.

The resonance condition for Floquet-induced FM exchange is not confined to the narrow frequency window denoted by the red-shaded regime in Fig. 4b, but extends across a broader range of pump frequencies. This broadening arises from two primary effects. First, the above simplified Floquet analysis, which is based on atomic models, requires adjustments to incorporate band dispersion and quantum fluctuations in many-body systems. Second, the intermediate-state energy Eint, which determines \({J}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) in Eq. (4), is not a fixed quantity in the doped EHM but varies across lattice sites in a given Fock state, depending on the local occupation configurations. As illustrated in the upper panels of Fig. 4c, configurations with isolated spin pairs or uniform neighbor densities yield Eint = U − V, corresponding to a strong resonance near Ω ~ U − V = 9th (solid lines in Fig. 4b). However, non-uniform occupations introduce a distribution of Eint values spanning from U − 4V to U + 2V. At an average filling of 〈n〉 = 0.5, this variation extends the resonance window from U + 0.5V = 7.5th to U − 2.5V = 10.5th, as indicated by translucence red and blue area in Fig. 4b. This asymmetric broadened resonance range around the center Ω = U − V aligns with the observed light-enhanced px pairing instabilities in Fig. 3, reflecting the role of Floquet engineering in tuning pairing correlations.

Beyond the dominant single-photon resonance, Floquet theory also predicts a two-photon resonance condition, occurring when the driving frequency satisfies Ω ≈ Eint/2 = 4.5 th. Variations in local occupations further modulate Eint, yielding a relatively narrower yet finite resonant window for the two-photon process, spanning from 3.75th to 5.25th. The frequency dependence observed in the simulated Φx(t) (Fig. 3) also aligns well with this prediction, further corroborating the role of Floquet engineering in modulating pairing correlations. Additional details on the pairing correlation dynamics at Ω = 5.2th are provided in Supplementary Note 3.

Beyond the Floquet-engineered spin exchange \({J}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\), the laser field also modifies the electronic hopping amplitude as \({t}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}} \sim t{{{\mathcal{J}}}}_{0}({A}_{0}\cdot {\hat{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{\alpha })\), thereby inducing anisotropy between the x and y directions. Although this anisotropy resembles the effect of uniaxial strain and does contribute to the spin-triplet pairing,42, it does not generate the mixed AFM-FM exchange interactions responsible for the resonances observed in Fig. 3, and thus does not serve as the primary mechanism behind the light-induced superconductivity in the EHM. Nevertheless, the suppression of \({t}_{x}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) constrains the strength of light-enhanced pairing, which explains the observed saturation and eventual decline of Φx around A0 ~ 1 in Fig. 3a, b.

Ultrafast switching between different channels

The ability to selectively enhance p-wave superconductivity along a given direction raises a compelling question: can optical excitation be used to switch the dominant pairing channel to an orthogonal one? Within a mean-field framework, transitions between different pairing channels like px and py (or between chiral states px + ipy and px − ipy) are inherently challenging due to the strict orthogonality of their order parameters. Typically, such a switch requires a carefully designed sequence of linear and circular pulses to navigate a path on the Bloch sphere that connects the two poles41,60. However, in strongly correlated many-body systems, quantum fluctuations naturally broaden the distribution of pairing correlations across the Bloch sphere rather than confining them to discrete symmetry-breaking points. This broader distribution may allow for more flexible control pathways, enabling direct switching between orthogonal p-wave channels without requiring finely tuned orchestrated pulse sequences.

To test this hypothesis, we simulate the response of spin-triplet pairing correlations to two sequential linear pulses with orthogonal polarizations. The first x-polarized pulse serves to establish light-induced px pairing correlations, as previously discussed, while the second pulse is designed specifically to validate the switching mechanism. Thus, the vector potential from Eq. (3) is modified as follows:

where Δt denotes the time delay between the two pump pulses and the relative phase \({\phi }^{{\prime} }-\phi\) controls their coherence. Here, we set both ϕ and \({\phi }^{{\prime} }\) to zero, while the impact of phase-averaging is discussed later.

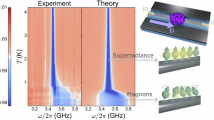

Figure 5a presents the evolution of spin-triplet pairing correlations under the influence of two sequential laser pulses. The first laser pulse, x-polarized with an amplitude A0 = 0.4 and frequency Ω = 9.2 th (same as Fig. 2), triggers the symmetry breaking and enhances the px pairing correlations. After several oscillation cycles, significantly exceeding the pulse duration, a second y-polarized laser pulse is applied at a time delay \(\Delta t=25\,{t}_{h}^{-1}\), maintaining the same pump frequency and phase. To ensure an active switching of the dominant pairing channel, rather than merely canceling the pre-established correlations (see Supplementary Note 4 for detailed discussions), the second pulse amplitude is set to \({A}_{0}^{{\prime} }=2{A}_{0}\) (see Fig. 5a). Remarkably, this second pulse rapidly reverses the dominance between Φx and Φy. The px pairing correlation experiences a substantial suppression, with its average intensity reduced by roughly 43%, while the py pairing correlation remains relatively less affected, due to the interplay between light-enhanced pairing effects and additional photo-induced carriers.

a Dynamics of the px, py, and px + py pairing correlations induced by two sequential pulses with x and y polarizations. Solid lines represent the phase-averaged pairing correlation \({\overline{\Phi }}_{\alpha }\), while the translucent lines correspond to results with a fixed phase ϕ = 0. The upper inset shows the vector potential of the pump field. b Redistribution of pairing correlations on the equatorial plane of the Bloch sphere at the three selected time points (marked in a). The central arrows indicate the relative magnitude of Φx − Φy at the corresponding time.

The dynamics underlying this ultrafast switching are best visualized through the Bloch sphere representation. In contrast to mean-field dynamics, where the order parameter is represented as a single point on the Bloch sphere, many-body pairing correlations Φα are distributed over the sphere. As shown in Fig. 5b, the y-polarized pulse triggers a redistribution of these correlations, effectively shifting the spectral weight towards the Φy direction while depleting the previously dominant Φx component stabilized by the initial pulse. This collective motion results in a persistent enhancement of Φy relative to Φx, with the centroid of the distribution clearly shifting towards the Φy along the Φx − Φy axis. For the chosen pulse strength \({A}_{0}^{{\prime} }=2{A}_{0}\), Φy consistently dominates after the second pulse (see the arrows in Fig. 5b), confirming the ultrafast switching mechanism driven solely by a single orthogonal pulse.

By varying the phases ϕ and \({\phi }^{{\prime} }\), we further explore the influence of coherence on the ultrafast switch. In Fig. 5a, the thick lines show the phase-averaged values of \({\overline{\Phi }}_{x}\), \({\overline{\Phi }}_{y}\), and \({\overline{\Phi }}_{x+y}\), computed by averaging over 20 different phases while keeping all other parameters fixed. Our results indicate that while minor high-frequency oscillations exhibit phase sensitivity, the overall envelope closely follows the previously discussed phase-locked behavior. This insensitivity arises from the pairing correlation in Eq. (2), which effectively eliminates the gauge degrees of freedom. As a result, both the light-induced enhancement of spin-triplet pairing and the ultrafast switching between pairing channels remain robust against variations in pump pulse coherence.

Discussion

Because of the need to preserve C4 symmetry and the inherent numerical difficulties of simulating nonequilibrium dynamics, our analysis is based on exact diagonalization of correlated electrons within a finite cluster, where spontaneous symmetry breaking cannot occur. Accordingly, we focus on short-range pairing correlations rather than off-diagonal long-range order, whose identification would require extrapolation to the 2D thermodynamic limit—a task currently beyond the reach of existing many-body computational techniques. Despite this limitation, short-range quantum fluctuations are a ubiquitous feature of strongly correlated systems. At equilibrium, fluctuation-driven non-symmetry-breaking gaps have been experimentally observed in unconventional superconductors, such as cuprates61,62 and FeSe63,64, as well as in other phase transitions65,66,67. These fluctuations become even more pronounced in low-dimensional or nanoscale materials. More importantly, light-induced superconductivity exhibits even stronger quantum fluctuations with shorter-range correlations51,68,69. These short-range correlations manifest as superconducting gaps with limited coherence, making them effectively indistinguishable from long-range orders in pump-probe spectroscopic measurements.

In strongly correlated systems, the inherent flexibility of pairing correlations offers significant advantages for laser-based control compared, beyond the constraints of mean-field order parameters. As demonstrated above, spin-triplet pairing correlations can be effectively engineered through Floquet manipulation of spin-exchange interactions J along the pump polarization. Furthermore, the distributed nature of these correlations across the Bloch sphere enables a straightforward single-pulse strategy to switch between orthogonal pairing channels, which would otherwise necessitate more sophisticated control protocols in a mean-field framework41,60, or rely on static uniaxial strain or Jahn-Teller distortions42. These fundamental differences suggest that many-body quantum fluctuations, rather than acting as a limiting factor, can instead serve as a powerful resource for the dynamic control of spin-triplet superconducting states. Such a distinction may also account for the fact that light-induced superconductivity has been frequently observed in correlated materials43,44,45,46,47,48.

Our study focuses on the ultrafast regime soon after the pump finishes. Based on estimated hopping parameters typical of cuprates (see Methods), the time interval shown in Figs. 2 and 5 spans approximately ~100 fs. This short interval lies within the prethermal regime, as identified in related systems52,53. If the simulation time were extended substantially, it would be necessary to account for additional effects such as heating, decoherence, and the retarded response of phonons.

Methods

Extended Hubbard model

The extended Hubbard model (EHM) and its variants effectively describe correlated electrons in transition-metal oxides. The Hamiltonian is defined as

where \({c}_{i\sigma }({c}_{i\sigma }^{{\dagger} })\) annihilates (creates) an electron at site i with spin σ = ↑, ↓ and \({n}_{i\sigma }={c}_{i\sigma }^{{\dagger} }{c}_{i\sigma }({n}_{i}={n}_{i\uparrow }+{n}_{i\downarrow })\) represents the electron density operator. The model incorporates three key parameters: the nearest-neighbor hopping amplitude th, the on-site Coulomb repulsion U, and the nearest-neighbor interaction V. In this study, the on-site U is always repulsive, accounting for the double-occupation energy, while the nearest-neighbor interaction V is attractive, representing an effective phonon-mediated interaction. We adopt model parameters U = 8th and V = −th, based on prior experimental estimates for 1D cuprate chains32,36, while the conclusion broadly applies to a variety of model parameters (see Supplementary Note 5). The simulation is performed within a canonical ensemble framework, where the total particle number is fixed to ensure quarter filling, and the temperature is set to absolute zero. For th = 300–400 meV, a 400-nm laser resides in the single-photon resonance and an 800-nm laser resides in the two-photon resonance. Simulations are conducted on a 4 × 4 cluster with periodic boundary conditions.

Peierls substitution and the Krylov–subspace method

To describe the light-driven dynamics, we incorporate the Peierls substitution \({t}_{h}{c}_{i\sigma }^{{\dagger} }{c}_{j\sigma }{{\rightarrow }}{t}_{h}{e}^{i\int_{{r}_{i}}^{{r}_{j}}{{\bf{A}}}(t)d{{\bf{r}}}}{c}_{i\sigma }^{{\dagger} }{c}_{j\sigma }\), which serves as an effective approximation of the light-matter interaction within the second-quantization framework. The specific pump vector potential A(t) is provided by Eqs. (3) and (5) of the main text. We employ the SLEPc library to solve the ground state70, which yields a three-fold degenerate ground state due to the hidden hypercubic symmetry of the 4 × 4 cluster. The expectation value of pairing correlations Φα is taken as an average over all degenerate states and all triplet Sz states at the instantaneous wavefunction \(\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle\). The time evolution of the ensemble-averaged density matrix is computed using the Krylov subspace method71.

Data availability

The numerical data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The relevant scripts to reproduce all figures are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Sarma, S. D., Freedman, M. & Nayak, C. Majorana zero modes and topological quantum computation. npj Quantum Inf. 1, 15001 (2015).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Sarma, S. D. Non-abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083 (2008).

Read, N. & Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267 (2000).

Ivanov, D. A. Non-Abelian statistics of half-quantum vortices in p-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 268 (2001).

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. -Usp. 44, 131 (2001).

Maeno, Y. et al. Superconductivity in a layered perovskite without copper. Nature 372, 532 (1994).

Rice, T. M. & Sigrist, M. Sr2RuO4: an electronic analogue of 3He? J. Phys. Condens. Matter 7, L643 (1995).

Baskaran, G. Why is Sr2RuO4 not a high Tc superconductor? Electron correlation, Hund’s coupling and p-wave instability. Phys. B Condens. Matter 223, 490 (1996).

Mackenzie, A. P. & Maeno, Y. The superconductivity of Sr2RuO4 and the physics of spin-triplet pairing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 657 (2003).

Maeno, Y., Kittaka, S., Nomura, T., Yonezawa, S. & Ishida, K. Evaluation of spin-triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 011009 (2011).

Nelson, K. D., Mao, Z. Q., Maeno, Y. & Liu, Y. Odd-parity superconductivity of Sr2RuO4. Science 306, 1151 (2004).

Pustogow, A. et al. Constraints on the superconducting order parameter in Sr2RuO4 from oxygen-17 nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature 574, 72 (2019).

Ishida, K., Manago, M., Kinjo, K. & Maeno, Y. Reduction of the 17O Knight shift in the superconducting state and the heat-up effect by NMR pulses on Sr2RuO4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 89, 034712 (2020).

Chronister, A. et al. Evidence for even parity unconventional superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Prod. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025313118 (2021).

Ran, S. et al. Nearly ferromagnetic spin-triplet superconductivity. Science 365, 684 (2019).

Ran, S. et al. Enhancement and reentrance of spin triplet superconductivity in UTe2 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 101, 140503(R) (2020).

Tou, H. et al. Odd-parity superconductivity with parallel spin pairing in UPt3: evidence from 195Pt knight shift study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1374 (1996).

Yang, J. et al. Spin-triplet superconductivity in K2Cr3As3. Sci. Adv. 7, eabl4432 (2021).

Lin, H. Q. & Hirsch, J. E. Condensation transition in the one-dimensional extended Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 33, 8155 (1986).

Penc, K. & Mila, F. Phase diagram of the one-dimensional extended Hubbard model with attractive and/or repulsive interactions at quarter filling. Phys. Rev. B 49, 9670 (1994).

Lin, H. Q., Gagliano, E. R., Campbell, D. K., Fradkin, E. H. & Gubernatis, J. E. The phase diagram of the one-dimensional extended Hubbard model. (Springer, 1995).

Xiang, Y.-Y., Liu, X.-J., Yuan, Y.-H., Cao, J. & Tang, C.-M. Doping dependence of the phase diagram in one-dimensional extended Hubbard model: a functional renormalization group study. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 31, 125601 (2019).

Shinjo, K. et al. Machine learning phase diagram in the half-filled one-dimensional extended Hubbard model. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 065001 (2019).

Qu, D.-W., Chen, B.-B., Jiang, H.-C., Wang, Y. & Li, W. Spin-triplet pairing induced by near-neighbor attraction in the extended Hubbard model for cuprate chain. Commun. Phys. 5, 257 (2022).

Onari, S., Arita, R., Kuroki, K. & Aoki, H. Phase diagram of the two-dimensional extended Hubbard model: phase transitions between different pairing symmetries when charge and spin fluctuations coexist. Phys. Rev. B 70, 094523 (2004).

Huang, W.-M., Lai, C.-Y., Shi, C. & Tsai, S.-W. Unconventional superconducting phases for the two-dimensional extended Hubbard model on a square lattice. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054504 (2013).

Nayak, S. & Kumar, S. Exotic superconducting states in the extended attractive Hubbard model. J. Phys: Condens. Matter 30, 135601 (2018).

van Loon, E. G. C. P. & Katsnelson, M. I. The extended Hubbard model with attractive interactions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1136, 012006 (2018).

Chen, W.-C., Wang, Y. & Chen, C.-C. Superconducting phases of the square-lattice extended Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 108, 064514 (2023).

Cao, Z., Li, J., Su, J., Ying, T. & Tang, H.-K. Dominant p-wave pairing induced by nearest-neighbor attraction in the square-lattice extended Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 111, 024509 (2025).

Farid, R., Gazizova, D., McNiven, B. D. E. & LeBlanc J. P. F. Lifshitz transition and triplet p-wave pairing from the induced ferromagnetic plaquette via spin differentiated nonlocal interaction. Phys. Rev. B 111, 125118 (2025).

Chen, Z. et al. Anomalously strong near-neighbor attraction in doped 1D cuprate chains. Science 373, 1235 (2021).

Padma, H. et al. Beyond-Hubbard pairing in a cuprate ladder. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021049 (2025).

Scheie, A. et al. Cooper-pair localization in the magnetic dynamics of a cuprate ladder. arXiv:2501.10296 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Doping dependence of 2-spinon excitations in the doped 1D cuprate Ba2CuO3+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 146501 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Phonon-mediated long-range attractive interaction in one-dimensional Cuprates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 197003 (2021).

Tang, T., Moritz, B., Peng, C., Shen, Z.-X. & Devereaux, T. P. Traces of electron-phonon coupling in one-dimensional cuprates. Nat. Commun. 14, 3129 (2023).

Feiguin, A. E., Helman, C. & Aligia, A. A. Effective one-band models for the one-dimensional cuprate Ba2−xSrxCuO3+δ. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075125 (2023).

Shen, Z., Liu, J., Wang, H.-X. & Wang, Y. Signatures of the attractive interaction in spin spectra of one-dimensional cuprate chains. Phys. Rev. Research 6, L032068 (2024).

Tang, T., Jost, D., Moritz, B. & Devereaux, T. P. Influence of extended interactions on spin dynamics in one-dimensional cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 110, 165118 (2024).

Claassen, M., Kennes, D. M., Zingl, M., Sentef, M. A. & Rubio, A. Universal optical control of chiral superconductors and Majorana modes. Nat. Phys. 15, 766 (2019).

Gassner, S., Weber, C. S. & Claassen, M. Light-induced switching between singlet and triplet superconducting states. Nat. Commun. 15, 1776 (2024).

Fausti, D. et al. Light-induced superconductivity in a stripe-ordered cuprate. Science 331, 189 (2011).

Nicoletti, D. et al. Optically induced superconductivity in striped La2−xBaxCuO4 by polarization-selective excitation in the near infrared. Phys. Rev. B 90, 100503 (2014).

Hu, W. et al. Optically enhanced coherent transport in YBa2Cu3O6.5 by ultrafast redistribution of interlayer coupling. Nat. Mater. 13, 705 (2014).

Mankowsky, R. et al. Nonlinear lattice dynamics as a basis for enhanced superconductivity in YBa2Cu3O6.5. Nature 516, 71 (2014).

Buzzi, M. et al. Photomolecular high-temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031028 (2020).

Buzzi, M. et al. Phase diagram for light-induced superconductivity in κ − (ET)2 − X. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 197002 (2021).

Mentink, J. H. & Eckstein, M. Ultrafast quenching of the exchange interaction in a Mott Insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 057201 (2014).

Mentink, J. H., Balzer, K. & Eckstein, M. Ultrafast and reversible control of the exchange interaction in Mott insulators. Nat. Commun. 6, 6708 (2015).

Wang, Y., Shi, T. & Chen, C.-C. Fluctuating nature of light-enhanced d-wave superconductivity: a time-dependent variational non-gaussian exact diagonalization study. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041028 (2021).

Aoki, H. et al. Nonequilibrium dynamical mean-field theory and its applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 779 (2014).

de la Torre, A. et al. Colloquium: nonthermal pathways to ultrafast control in quantum materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 041002 (2021).

Kalthoff, M. H., Kennes, D. M. & Sentef, M. A. Floquet-engineered light-cone spreading of correlations in a driven quantum chain. Phys. Rev. B 100, 165125 (2019).

Sentef, M. A., Li, J., Künzel, F. & Eckstein, M. Quantum to classical crossover of Floquet engineering in correlated quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Research 2, 033033 (2020).

Oka, T. & Kitamura, S. Floquet engineering of quantum materials. Ann. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 387 (2019).

Rudner, M. S. & Lindner, N. H. Band structure engineering and non-equilibrium dynamics in Floquet topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 229 (2020).

Eckardt, A. & Anisimovas, E. High-frequency approximation for periodically driven quantum systems from a Floquet-space perspective. N. J. Phys. 17, 093039 (2015).

Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Devereaux, T. P., Moritz, B. & Mitrano, M. X-ray scattering from light-driven spin fluctuations in a doped Mott insulator. Commun. Phys. 4, 212 (2021).

Yu, T., Claassen, M., Kennes, D. M. & Sentef, M. A. Optical manipulation of domains in chiral topological superconductors. Phys. Rev. Research 3, 013253 (2021).

Kondo, T. et al. Point nodes persisting far beyond Tc in Bi2212. Nat. Commun. 6, 1 (2015).

He, Y. et al. Superconducting fluctuations in overdoped Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031068 (2021).

Faeth, B. D. et al. Incoherent Cooper pairing and pseudogap behavior in single-layer FeSe/SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. X 11, 021054 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Spectroscopic evidence of superconductivity pairing at 83 K in single-layer FeSe/SrTiO3 films. Nat. Commun. 12, 2840 (2021).

Schäfer, J. et al. High-temperature symmetry breaking in the electronic band structure of the quasi-one-dimensional solid NbSe3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 196403 (2001).

Chatterjee, U. et al. Emergence of coherence in the charge-density wave state of 2H−NbSe2. Nat. Commun. 6, 6313 (2015).

Chen, C. et al. Role of electron-phonon coupling in excitonic insulator candidate Ta2NiSe5. Phys. Rev. Research 5, 043089 (2023).

Boschini, F. et al. Collapse of superconductivity in cuprates via ultrafast quenching of phase coherence. Nat. Mater. 17, 416 (2018).

Sun, Z. & Millis, A. J. Transient trapping into metastable states in systems with competing orders. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021028 (2020).

Hernandez, V., Roman, J. E. & Vidal, V. SLEPc: a scalable and flexible toolkit for the solution of eigenvalue problems. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 31, 351 (2005).

Manmana, S. R., Wessel, S., Noack, R. M. & Muramatsu, A. Strongly correlated fermions after a quantum quench. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 210405 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge insightful discussions from Cheng-Chien Chen, Martin Claassen and Matteo Mitrano. This work is supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Young Investigator Program under grant FA9550-23-1-0153. The simulations presented in this paper were performed on the Frontera computation system at Texas Advanced Computing Center, operated under NSF Award No.OAC-1818253.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. conceived the project. Z.S. and W.-C.C. performed the calculations and data analysis. Z.S., C.X. and Y.W. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Z., Xie, C., Chen, WC. et al. Light control of triplet pairing in correlated electrons with mixed-sign interactions. Commun Phys 8, 475 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02371-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02371-z