Abstract

Microorganisms such as bacteria and algae navigate complex fluids, where their dynamics are vital for medical and industrial applications. However, the influence of the Reynolds number (Re) on the transport and rotational behavior of microswimmers in viscoelastic media remains poorly understood. Here, we investigate these effects for a model squirmer in flexible polymer solutions across a range of Re using Lattice Boltzmann simulations. The interaction between swimmer activity and polymer heterogeneity strongly affects behavior, with rotational enhancement up to 1400-fold and reduced self-propulsion and diffusivity for squirmers. These effects result from hydrodynamic and mechanical interactions: polymers wrap ahead of pushers and accumulate behind pullers, enhancing rotation while hindering translation through forces and torques from direct contacts or asymmetric flows. The influence of Re and squirmer-polymer boundary conditions (no-slip vs. repulsive) is also examined. Notably, no-slip conditions intensify effects above a critical Reynolds number (\({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}=0.2\)). Below this value, stronger viscous drag minimizes differences. Our findings emphasize the crucial role of polymer-swimmer interactions in shaping microswimmer behavior in viscoelastic media, informing microrobotic design in complex environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compared to simple viscous fluids, the natural habitats of microorganisms and the operational environments of artificial microswimmers are generally complex. These environments are typically viscoelastic and span various Reynolds number regimes. As a dimensionless quantity, the Reynolds number (Re) predicts fluid flow patterns in different circumstances by measuring the ratio between inertia and viscous forces1,2. In general, microswimmers typically reside in the regime of extremely low Reynolds numbers (\({{{\rm{Re}}}}\ll 1\)), displaying a rich array of behaviors. For instance, Bacillus subtilis and Chlamydomonas swim at Reynolds numbers of approximately 10−4 3 and 10−3 4, respectively, while Paramecium swims at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\approx 0.1\)5. In the low Reynolds number range (\({{{\rm{Re}}}}=1{0}^{-5}\) to 10−3), densely suspended bacteria display collective behaviors6 such as large-scale flow patterns and vortices7, locally synchronized movements8, uneven spatial distribution of swimmers, and increased diffusion and mixing9. William et al. first reported a microscale, biohybrid swimmer propelled by contractile cells, operating at a low \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\approx 1{0}^{-2}\). By using the standard lithographic techniques and mass-scale cell plating, these swimmers are amenable to batch fabrication10. At \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=2.5\times 1{0}^{-4}\), the swimming motion of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii experiences greater viscous resistance during the forward stroke than during the backward stroke, breaking time-reversal symmetry and ensuring propulsion11. A study on low Reynolds number propulsion (1.4 × 10−4 ~ 3 × 10−3) of a scallop indicates that differences in the opening and closing rates result in varying shear rates and, consequently, different viscosities in non-Newtonian fluids12. In addition, the average velocity of the micro-scallop in the shear thickening fluid is faster than in a shear-thinning fluid12. Another study on a flagellated swimmer \(({{{\rm{Re}}}} < 0.3)\) in unbounded space driven by Quincke rotation reveals that the Quincke swimmer exhibits three forms of motion-roll, pitch, and self-oscillatory rotation by varying the electric field and the angle between the two filaments13.

In contrast to the low Reynolds number regime where viscous forces are dominant, the influence of inertia on the behavior of microswimmers has gained increasing attention. Investigations at finite Reynolds numbers not only shed light on predator-prey interactions, sexual reproduction, and encounter rates of marine organisms but also aid in the design and fabrication of efficient artificial swimmers14,15. Squirmers with different swimming schemes exhibit significant differences in locomotion across Reynolds number \((0.01 < {{{\rm{Re}}}} < 1000)\), i.e., pushers display a monotonic increase in swimming speed with raising Re, whereas pullers exhibit a non-monotonic behavior16. By using the squirmer model in the regime of \({{{\rm{Re}}}} \sim {{{\rm{O}}}}(0.1-100)\), Li revealed that inertial effects alter the contact time and dispersion dynamics of a pair of pusher swimmers, while triggering hydrodynamic attraction between two pullers6. A study on a self-propelled slender swimmer in a chaotic flow field with a flow Reynolds number up to 10 illustrated that pushers exhibit more efficient locomotion than pullers due to the different distribution of vorticity within the wake17. Suspensions of slender pusher and puller swimmers present nontrivial flow motions as the Reynolds number \((1 < {{{\rm{Re}}}} < 50)\) changes along with complex swimmer dynamics18. The pairwise hydrodynamic interactions for simple two-dimensional dimer model swimmers19,20,21 over a range of finite Re were investigated numerically. Based on the Reynolds number \((0.1 < {{{\rm{Re}}}} < 40)\) and initial positions, two swimmers can either repel and move away from each other or form one of four stable pairs: in-line and in tandem22. An experimental and numerical study on self-assembled ferromagnetic spinners at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\approx 30\) showed that spinner suspensions induce vigorous vortical flows at the interface, exhibiting properties of well-developed 2D hydrodynamic turbulence23.

The natural habitats of microorganisms and spermatozoa predominantly consist of polymeric environments24. For instance, sperm exhibit motility in the cervix and along the fallopian tubes25,26,27,28,29,30,31, while bacteria swarms within biofilms composed of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium associated with ulcers, adapts to the acidic conditions of the stomach by altering the rheological properties of the mucus lining40,41. Additionally, synthetic micromotors employed in drug delivery42, microsurgery43, and disease detection44 operate within complex environments. As a consequence, comprehending the locomotion of swimmers in non-Newtonian fluids is imperative for potential biomedical and industrial applications. Intuitively, the existence of macromolecules will hinder the translational motion of swimmers due to increased viscosity45,46,47,48. However, abundant variations in swimming speed have been reported49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. By using finite element methods, Zhu et al.46,59 revealed that both translational motion and power consumption of squirmers are reduced in a polymeric fluid. In the case of two-dimensional undulatory kicker swimmers, the high polymer stress at the tail enhances the swimming velocity60. The rotating flagella of bacteria generate a depletion zone of long polymers, resulting in an apparent slip velocity between the fluid and the swimmer. Consequently, the swimming speed has been increased up to 60%58. Notably, recent experiments have reported significant enhancements in the rotational motion of active Brownian colloidal particles embedded in viscoelastic fluids61. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the enhanced diffusions turn into persistent circular rotations above a critical Deborah number62. Meanwhile, hydrodynamic simulations via multiparticle collision dynamics indicated that a decrease of adsorbed polymers by active motion and asymmetric squirmer-polymer encounters can result in large rotational enhancements for a neutral squirmer63. In addition, the interplay between geometrical confinement and fluid viscoelasticity gives rise to intriguing phenomena. Recent experiments unraveled that E. coli immersed in a DNA solution and under spherical confinement can self-organize into a millimeter-scale rotating vortex. The giant vortex switches its global chirality periodically with tunable frequency64. Experiments involving active particles in viscoelastic fluids under various geometrical constraints, such as flat walls, spherical obstacles, and cylindrical cavities, revealed that confined viscoelastic fluids can induce an effective repulsion on particles when approaching a rigid surface. The repulsion strength has a dependence on the incident angle, surface curvature, and particle activity65. In the case of swimmer suspensions, viscoelasticity exerts profound influences on collective behavior66,67,68,69. For example, Bovine spermatozoa exhibit disordered individual swimming in Newtonian fluids, but cell-cell alignments and dynamic cluster formations in viscoelastic fluids70. Additionally, simulations of multiple rodlike microswimmers in 2D continuum viscoelastic fluids demonstrated that the cluster aggregation for pushers is evidently enhanced by viscoelasticity, while the effect on pullers is subtle69. However, the interplay between viscoelasticity and Reynolds number on the dynamics of microswimmers has not been thoroughly explored.

In this study, we aim to reveal the translational and rotational mechanisms of generic spherical squirmers immersed in viscoelastic fluids across a range of Reynolds numbers by employing the Lattice–Boltzmann method. Viscoelasticity is incorporated by explicitly including linear flexible polymers. Both no-slip and repulsive boundary conditions between the squirmers and polymers are examined. Our results clearly demonstrate how hydrodynamic and steric interactions between deformed polymers and squirmers influence rotational motion, which in turn affects swimming speed and translational diffusion. In general, stronger rotational enhancement reduces a swimmer’s ability to maintain persistent forward motion, leading to decreases in swimming speed and translational diffusivity. These mechanisms depend on the type of active stress: polymer wrapping occurs in front of a pusher, while numerous polymers are absorbed at the rear of a puller. These interactions generate heterogeneous forces and torques or induce asymmetric local flows that amplify the squirmer’s rotation. In comparison, the source dipole flow field of a neutral swimmer allows polymers to skim quickly over its surface, resulting in no substantial enhancement. Due to these mechanisms, significant rotational enhancements of up to 1400 have been observed. Interestingly, we identify a critical Reynolds number, \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}=0.2\), above which the differences between the no-slip and repulsive boundary conditions in swimmers’ transport and rotational properties become significant, but remain minor in the low-Re regime. The influences of temperature, Reynolds number, polymer concentration, chain length, and polymer-squirmer size ratio on these properties are also investigated. Our findings highlight the critical role of system heterogeneity resulting from dispersed polymers in determining the behavior of squirmers in viscoelastic fluids.

Results

Transport and rotational properties at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\)

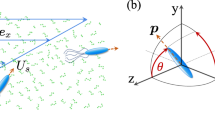

As shown in Fig. 1, our system consists of a spherical squirmer embedded in a flexible polymer solution. Viscoelasticity is introduced by dispersing Np = 96 flexible polymers, each composed of Nm = 240 monomers, within a cubic simulation box of length L = 72a. The resulting monomer packing fraction is ϕ = NmNp/L3 = 0.06 a−3. In this work, all quantities are expressed in lattice units, with the characteristic length, time, and mass defined as a = τ = m = 1. The swimming strategy is characterized by the active stress β, where β > 0 corresponds to a pusher, β < 0 to a puller, and β = 0 to a neutral swimmer63,71,72. The swimming speed is given by \({U}_{0}=\frac{2}{3}{B}_{1}\), determined by the strength of the first squirming mode B173,74. Unless otherwise specified, B1 = 0.005 is used in the main part of this work. The influence of two boundary conditions—no-slip and repulsive—is examined independently. Details of the model are provided in the Methods section.

Sketch of a spherical squirmer with radius R immersed in a viscoelastic fluid. The squirmer self-propels along the polar direction e, with er and eθ denoting the radial and tangential unit vectors, respectively. The fluid’s one-particle distribution function fi(x, t) propagates only along the discrete lattice directions. Viscoelasticity is incorporated by embedding flexible polymers (yellow bead–spring chains) into the fluid.

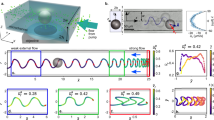

The rotational behavior of squirmers with different swimming strategies in complex fluids is first investigated at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\). It should be noted that the Reynolds number is varied by changing the fluid viscosity in this work (see Methods for details). The rotational dynamics are characterized by the orientation correlation function

where Dr is the activity-dependent rotational diffusion coefficient and e refers to the polar direction of squirmer. For clarity, \({D}_{r}^{a}\) and \({D}_{r}^{p}\) are used in the following text to distinguish the rotational diffusion coefficients of the active swimmer and the passive colloid. Figure 2(a) shows the orientation correlation functions for pullers and colloids at various temperatures. The no-slip boundary condition between squirmers and monomers is employed in these simulations. As shown in Fig. 2(a), the rotational diffusion coefficients for passive colloids follow the Stokes-Einstein-Debye relation and are only minimally affected by the presence of polymers. They change coherently by about two orders of magnitude as the temperature increases. However, activity significantly enhances the rotational diffusion of pullers at low temperatures. For example, \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\approx 26\) at kBT/ε = 0.0005. Contrarily, at the higher temperature of kBT/ε = 0.05, thermal effects dominate and the enhancement due to activity is negligible. Here, ε = 0.002 ma2/τ2 is the polymer bond strength.

a Orientation correlation functions C(t) for pullers (β = 5) and passive colloids at different temperatures. Here, t refers to the simulation time. A no-slip boundary condition is enforced between squirmers and monomers. The decrease in the redness (for the puller, active stress β = 5) or purpleness (for the passive colloid) of the C(t) curves indicates a reduction in temperature. Solid lines show simulation results, while dashed lines represent fitted curves obtained using the fitted rotational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{a}=1.2,1.8,6.8\times 1{0}^{-6}\,{\tau }^{-1}\) for pullers and \({D}_{r}^{p}=4.7\times 1{0}^{-8},4.3\times 1{0}^{-7},4.8\times 1{0}^{-6}\,{\tau }^{-1}\) for passive colloids at kBT/ε = 0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, respectively. Vertical lines indicate error bars, which become larger in the long-time regime due to limited statistics. Time is normalized by the characteristic time scale τ0 = 3R/B1 = 1800 τ, which corresponds to the time required for a swimmer to traverse one body length. (b) Rotational diffusion enhancements \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) for swimmers with the no-slip (ns, dashed line) and repulsive (rp, solid line) boundary conditions. Here, β denotes active stress. Blue, red, and green lines correspond to pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively. The rotational diffusion coefficients for passive colloids with the no-slip boundary condition are \({D}_{r}^{p}=4.7\times 1{0}^{-8}\), 4.3 × 10−7, and 4.8 × 10−6 τ−1 at temperatures kBT/ε = 0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, respectively. For the repulsive boundary condition, the values are \({D}_{r}^{p}=4.9\times 1{0}^{-8}\), 4.5 × 10−7, and 4.2 × 10−6 τ−1. The snapshots show representative configurations of squirmers with the no-slip boundary condition at kBT/ε = 0.0005. The dotted line represents the reference curve.

The rotational enhancements of different types of swimmers are examined. As shown in Fig. 2(b), the enhancements generally exhibit a monotonic decay proportional to the temperature as \({({k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T/\varepsilon )}^{-1}\). This dependence primarily arises from the increased rotational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{p}\) of passive colloids due to the Stokes-Einstein-Debye relation (Supplementary Fig. 3(c)), whereas the relatively small variations in the swimmers’ diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{a}\) lead to deviations from the reference curve in Fig. 2(b) (Supplementary Fig. 3(a)). The rotational diffusion coefficient of a pusher with the no-slip boundary condition is enhanced by more than 50 times at kBT/ε = 0.0005. At \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\), where fluid inertia becomes significant, polymers are rapidly advected by the flow (with a monomer velocity vm ≈ 0.0035 a/τ, as shown in Fig. 3(b)) to the vicinity of the squirmer, resulting in a high monomer concentration on its surface. In particular, a distinct narrow ring with a monomer density of ρm = 0.09 a−3 is observed in front of the no-slip pusher in Fig. 3(a). This high density originates from the polymer wrapping effect during swimming. These polymers are stabilized on the squirmer’s surface by the advective flow from the side. Consequently, substantial momentum and angular momentum exchanges occur, greatly enhancing the rotational motion of the pusher (Supplementary Movie 1 and Fig. 2(b) sketch). This mechanism is the primary contributor to its rotational enhancement. Although a high monomer concentration is also observed at θ ≈ π/2, frequent collisions on both sides of the squirmer compensate each other, producing zero net torque and thus no significant contribution to rotational enhancement. When the repulsive boundary condition is applied, direct encounters between polymers and the squirmer are prevented, weakening the wrapping effect (Supplementary Movie 2). As a result, the monomer density in front of the pusher decreases to ρm = 0.04 a−3. Nevertheless, heterogeneously distributed polymers induce asymmetric flows that indirectly mediate interactions between the pusher and polymers through the fluid-squirmer no-slip boundary condition. Therefore, a rotational diffusion enhancement of over 10 times is observed for the repulsive pusher at kBT/ε = 0.05. Naturally, this enhancement is 4.2 times weaker compared to the no-slip boundary condition due to the absence of direct polymer-squirmer encounters.

a, b refer to monomer density ρm and velocity vm distributions, respectively. Colorbars indicate the magnitude of the corresponding distributions. The green sphere refers to the squirmer with its orientation denoted by a red arrow. The no-slip and repulsive boundary conditions are applied, respectively. The contour plots of monomer number density and velocity are generated by time-averaging the local monomer density and velocity fields in the vicinity of the squirmer, in the cylindrical center-of-mass frame of the swimmer, across multiple time frames.

The rotational enhancement for a puller (β = 5) is also significant. Under the no-slip boundary condition, the enhancement reaches 26 times. As shown in Supplementary Movie 3, this enhancement primarily arises from the heterogeneous distribution of polymers absorbed at the rear of the puller. These polymers are advected near the puller by backward suction flows (Supplementary Movie 3 and Fig. 2(b) sketch). Their presence induces asymmetric flows, which enhance the squirmer’s rotation through the fluid-squirmer no-slip boundary condition. Additionally, collisions between the squirmer and polymers generate extra asymmetric forces and torques, further promoting the puller’s rotational motion. In Fig. 3(a), a broadly distributed monomer density of ρ = 0.15 a−3 is observed at the rear of the puller. Meanwhile, numerous polymers are also present at the front but exert only weak influence on rotation. This is because, on one hand, the frequent polymer-squirmer collisions there are fairly homogeneous, resulting in negligible net momentum or angular momentum transfer. On the other hand, these polymers are rapidly advected to the sides of the puller, limiting their impact on rotation (Supplementary Movie 3). For the puller with the repulsive boundary condition, the mechanism is similar (Supplementary Movie 4). However, due to the absence of direct contacts, only asymmetric flows induced by the heterogeneous polymer distribution contribute to the rotational enhancement, resulting in approximately half the strength of the no-slip case. Notably, the monomer density at the front, ρm = 0.18 a−3, is higher than in the no-slip case because repulsion acts as a long-range interaction, slowing and causing polymers to accumulate near the squirmer. Consequently, polymers at the rear are decelerated before reaching the puller, lowering the monomer density there to ρ = 0.06 a−3, which further reduces the rotational enhancement caused by induced asymmetric flows.

Unlike pushers and pullers, neutral swimmers do not exhibit profound rotational enhancement, as shown in Fig. 2(b). This is because the source dipole flow field75 generated by a neutral swimmer has limited influence on the collective motion of polymers, as clearly demonstrated in Fig. 3(b). Additionally, polymers near the neutral swimmer are advected by the flow and rapidly skim over its surface (Supplementary Movie 5 and 6 and the sketch in Fig. 2(b)). Consequently, no significant momentum or angular momentum exchange occurs, and the induced asymmetric flows remain weak.

The mean swimming velocities 〈U ⋅ e〉 for various swimmers are shown in Fig. 4(a). The combination of finite Reynolds number effects and different self-propulsion mechanisms results in distinct behavior among the swimmers. For neutral swimmers with the repulsive boundary condition, the mean swimming velocities in the polymer solution are close to those in the Newtonian case. This is because the source dipole flow field generated by a neutral swimmer can quickly advect nearby polymers to the rear, minimizing their impact on translation. The reduction in velocity becomes more evident at kBT/ε = 0.05 due to the stronger influence of thermal fluctuations, with a decrease of about 3.5% observed. In the case of pullers, the influence of polymers is more pronounced. The force dipole flow field generated by a puller causes frequent monomer-squirmer collisions at the front, which impede translation. Additionally, rear-side suction of polymers further slows down the swimmer. When the repulsive boundary condition is applied, this slowing effect is approximately 4%. In contrast, it reaches about 10% with the no-slip boundary condition due to closer contact between polymers and pullers at low temperatures. However, this difference diminishes at kBT/ε = 0.05. This trend is consistent with the change in the rotational enhancements of pullers shown in Fig. 2(b), where thermal effects eliminate the boundary-condition-induced difference at higher temperatures. For pushers, the difference between the two boundary conditions is subtle: the no-slip boundary condition results in only an additional 1.5% reduction in 〈U ⋅ e〉 compared to the repulsive case. Moreover, thermal effects are more significant for pushers. Consistent decreases in the mean swimming velocity from 3% to 13% are observed as the temperature increases.

a, b refer to the mean swimming velocities 〈U ⋅ e〉 and the translational diffusion enhancements \({D}_{t}^{a}/{D}_{t}^{p}\) of squirmers, respectively. Here, β denotes the active stress. Blue, red, and green lines indicate pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively, while solid and dashed lines denote repulsive and no-slip boundary conditions. Mean swimming velocities are normalized by their Newtonian fluid counterparts, 〈U⋅e〉N, while translational diffusion coefficients are normalized by the translational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{t}^{p}=7.07\times 1{0}^{-7},7.07\times 1{0}^{-6},7.07\times 1{0}^{-5}{a}^{2}/\tau\) for a colloid of radius R = 3a at temperature kBT/ε = 0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, respectively. The dotted line represents the reference curve.

As shown in Fig. 4(b), the enhancement of the translational diffusivities of squirmers in polymer solutions are systematically analyzed. For all types of active stress, the enhancement exhibits a monotonic decrease proportional to the temperature as \({({k}_{B}T/\varepsilon )}^{-1}\). The translational diffusivity of a swimmer follows the relation \({D}_{t}^{a} \sim {D}_{t}^{p}+{U}^{2}/{D}_{r}^{a}\), where \({D}_{t}^{a}\) and \({D}_{r}^{a}\) are the translational and rotational diffusion coefficients of the swimmer, \({D}_{t}^{p}\) is the translational diffusion coefficient for a passive colloid, and U denotes the swimming speed. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 and 4, since the contribution from the passive translational diffusion term is negligible, the active term \({U}^{2}/{D}_{r}^{a}\) predominantly determines \({D}_{t}^{a}\). The temperature dependence of the translational enhancement is therefore attributed to the translational diffusion coefficient of the passive colloid due to the Stokes-Einstein relation (Supplementary Fig. 4(c)), while the deviations arise from the relatively small variations in the swimmers’ translational diffusion coefficients (Supplementary Fig. 4(a)). Furthermore, the no-slip boundary condition induces stronger rotational motion for both pushers and pullers, resulting in less pronounced decay in their translational motion compared to their counterparts with repulsive boundary conditions. Contrarily, boundary condition effects are negligible for neutral squirmers. Additionally, neutral swimmers and pushers exhibit higher translational mobility than pullers, which is consistent with their comparatively weaker rotational dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Transport and rotational properties at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\)

As shown in Fig. 5, similar to the previous case, the rotational enhancements of swimmers at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\) also exhibit a clear \({({k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T/\varepsilon )}^{-1}\) temperature dependence, which is mainly attributed to the increased rotational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{p}\) of passive colloids (Supplementary Fig. 3(d)). On the other hand, the relatively small variations in the swimmers’ diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{a}\) (Supplementary Fig. 3(b)) lead to deviations from the reference curve in Fig. 5. The interplay of activity and system heterogeneity governs the enhancements at low temperatures, but thermal effects quickly become dominant at kBT/ε = 0.05. Notably, the enhancements at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\) are more pronounced than those at finite Reynolds numbers. In particular, reminiscent of experiments where a Janus particle is immersed in viscoelastic solutions61, the enhancement for a puller with the no-slip boundary condition exceeds two orders of magnitude. However, in our case, this strong enhancement is mainly attributed to the significant reduction of the rotational diffusion coefficient of a passive colloid in the high-viscosity solution (η = 0.5 m/aτ), i.e., \({D}_{r}^{p}=4\times 1{0}^{-9}\,{\tau }^{-1}\) at kBT/ε = 0.0005. The interplay of activity and system heterogeneity in our fluid-like polymer solutions cannot induce the persistent circular motion seen in experiments, which arises from the memory effect of viscoelastic fluids62. This memory effect originates from the misalignment between the instantaneous particle orientation and the internal forces generated by deformed polymers during self-propulsion. However, because our polymer solutions are more fluid-like, the observed enhancements in rotational diffusion are primarily due to squirmer-polymer mechanical couplings. Different from the \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\) case, the no-slip boundary condition does not provide a strong additional contribution to the enhancement (Fig. 5) because viscous drag dominates at low Reynolds numbers, leading to reduced fluid motility (Supplementary Fig. 5). As a result, polymers advected by the flow become less motile, making it more difficult for them to reach the squirmers and thus reducing momentum and angular momentum exchange. This phenomenon is evident in Fig. 6(a), where the monomer densities in the vicinity of squirmers are generally lower than those shown in Fig. 3(a).

Here, β denotes active stress. Blue, red, and green lines correspond to pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively, while solid and dashed lines denote repulsive and no-slip boundary conditions. The rotational diffusion coefficients for passive colloids with the no-slip boundary condition are \({D}_{r}^{p}=4.1\times 1{0}^{-9}\), 3.5 × 10−8, and 3.8 × 10−7 τ−1 at temperatures kBT/ε = 0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, respectively. For the repulsive boundary condition, the values are \({D}_{r}^{p}=4.0\times 1{0}^{-9}\), 3.9 × 10−8, and 4.0 × 10−7 τ−1. The snapshots show representative configurations of squirmers with the no-slip boundary condition at kBT/ε = 0.0005. The dotted line represents the reference curve.

a, b refer to monomer density ρm and velocity vm distributions, respectively. Colorbars indicate the magnitude of the corresponding distributions. The green sphere refers to the squirmer with its orientation denoted by a red arrow. The no-slip and repulsive boundary conditions are applied, respectively. The contour plots of monomer number density and velocity are generated by time-averaging the local monomer density and velocity fields in the vicinity of the squirmer, in the cylindrical center-of-mass frame of the swimmer, across multiple time frames.

As shown in Fig. 6, the reduction in polymer motility leads to a clear decrease in monomer density near a pusher, especially in front of the squirmer where it nearly drops to zero. Consequently, the polymer wrapping effect is strongly suppressed. However, as demonstrated in Supplementary Movie 7, where a no-slip boundary condition is applied between the polymers and the pusher, a notable amount of polymer wrapping still occurs. This generates additional momentum and angular momentum exchange, which promotes the squirmer’s rotation, though its influence is less pronounced than at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\). Compared with the repulsive case where the wrapping effect is weaker (Supplementary Movie 8), the relative enhancement in Fig. 5 is only 1.2, even though the absolute enhancement reaches 66.

The influence of decreased polymer motility is less severe for pullers. This is because the mechanism involving heterogeneously suctioned polymers at the rear of the puller remains effective (Supplementary Movie 9, 10, Fig. 5 sketch, and Fig. 6(a)). Consequently, in Fig. 5, a significant net enhancement of over 110 times is observed for the no-slip boundary condition at kBT/ε = 0.0005, which is about 1.3 times stronger than in the repulsive case. This occurs because the reduced motility inhibits polymers from reaching the squirmer, thereby suppressing momentum and angular momentum exchanges under the no-slip boundary condition. This effect is shown in Fig.6(a), where the monomer concentration at the rear of the squirmer becomes lower and narrower with the no-slip condition. It is worth noting that the breadth of the monomer density distribution is important, since polymers located farther from the centerline generate stronger torques through asymmetric flows. In the repulsive boundary condition case, the distribution appears brighter but narrower compared to the case at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\). Here, polymers stay closer to the centerline, and their influence on the rotational enhancement of the puller is consequently less pronounced (Supplementary Movie 4 and 10).

Similar to the case at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\), neutral swimmers also do not exhibit significant rotational enhancements due to the rapid polymer advection process (Supplementary Movie 11 and 12, Fig. 5 sketch). A sixfold enhancement is found at kBT/ε = 0.0005 in Fig. 5.

It is noteworthy that the enhanced rotational motion of squirmers is entirely attributed to the intrinsic properties of the polymers. For comparison, the rotational diffusion of squirmers in monomer fluids is also investigated, with the monomer concentration kept consistent with the previous study. The rotational diffusion coefficients for the pusher, puller, and neutral swimmer are \({D}_{r}^{m}=2.4,6.7,8.0\times 1{0}^{-9}\,{\tau }^{-1}\), respectively, which are close to the theoretical estimation of 3.0 × 10−9 τ−1 for a spherical squirmer in a Newtonian fluid.

The transport properties of swimmers at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\) are presented in Fig. 7(a). Consistent with previous studies46,76, fluid viscoelasticity leads to reductions in the mean swimming velocities for all squirmers compared to their Newtonian counterparts. For neutral swimmers, due to the rapid polymer advection effect, the reduction is only about 1% with the no-slip boundary condition and 2% when the repulsion is applied. Front monomer-squirmer collisions and rear-side polymer suction cause stronger reductions for pullers, with decreases of approximately 3.5% and 5% for the repulsive and no-slip cases, respectively. The larger reduction for the no-slip condition is due to closer polymer-puller interactions. Consistent decreases from 2% to 6% in the mean swimming velocities of pushers are also observed at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\). Similarly, the differences between the two boundary conditions diminish due to reduced polymer motility, resulting in fewer monomer-squirmer collisions.

a, b refer to the mean swimming velocities 〈U ⋅ e〉 and the translational diffusion enhancements \({D}_{t}^{a}/{D}_{t}^{p}\) of squirmers, respectively. Here, β denotes the active stress. Blue, red, and green lines indicate pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively, while solid and dashed lines denote repulsive and no-slip boundary conditions. Mean swimming velocities are normalized by their Newtonian fluid counterparts, 〈U⋅e〉N, while translational diffusion coefficients are normalized by the translational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{t}^{p}=3.54\times 1{0}^{-8},3.54\times 1{0}^{-7},3.54\times 1{0}^{-6}{a}^{2}/\tau\) for a colloid of radius R = 3a at temperature kBT/ε = 0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, respectively. The dotted line represents the reference curve.

The translational diffusivity of squirmers with different types of active stress is investigated and presented in Fig. 7(b). Similar to the case at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\), the translational enhancements exhibit a monotonic decay proportional to the temperature as \({({k}_{B}T/\varepsilon )}^{-1}\). This decay is primarily attributed to the temperature dependence of the translational diffusion coefficient of the passive colloid (Supplementary Fig. 4). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 and 4, the rotational diffusion coefficients of pushers and pullers are substantially elevated due to front-side polymer wrapping and rear-side polymer suction effects. These mechanisms reduce their translational mobility compared to neutral swimmers, whose rotational dynamics remain largely unaffected by the presence of polymers. For pullers, comparing to the repulsive boundary condition, the no-slip boundary condition permits closer polymer approach, which intensifies heterogeneous flows in the vicinity of the swimmer. This in general amplifies rotational motion and results in a more pronounced suppression of translational diffusion.

Effects of Reynolds number

As shown in Fig. 8(a), the dependence of rotational diffusion enhancement on the Reynolds number is presented. In general, a decay approximately proportional to \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}^{-1}\) is observed in most cases as \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\) increases. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, since the Reynolds number is increased by reducing the fluid viscosity in our simulations, these decays are mainly attributed to the increase in the rotational diffusion coefficient \({D}_{r}^{p}\) of the passive colloid with increasing \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\). This correlation is evidently illustrated by the reference curve in Supplementary Fig. 6. The deviation of reference curve in Fig. 8(a) stems from variations in the swimmers’ rotational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{a}\), which are attributed to heterogeneous hydrodynamic and steric interactions between squirmers and polymers. In addition, the enhancements show a clear dependence on the active stress. Due to the front-side polymer wrapping and rear-side polymer suction effects, the enhancements for pushers and pullers are about an order of magnitude stronger than those for neutral swimmers. Since the no-slip boundary condition allows polymers to approach squirmers more closely, the enhancements under this boundary condition are in principle stronger than in the cases with a purely repulsive boundary condition. However, the difference between these two boundary conditions is only pronounced above the critical Reynolds number \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}=0.2\), because the weaker viscous drag results in stronger fluid motility and thus more effective advection of polymers. Conversely, the discrepancy is small in the low-Re regime. Moreover, the influence of the boundary condition is less evident for pullers, because the rear-side polymer suction effect is less sensitive to changes in fluid viscosity. Specifically, pullers under the repulsive boundary condition exhibit more pronounced enhancement than pushers, while a crossover is observed between the pusher and puller \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) curves under the no-slip boundary condition. This is because the front-side polymer wrapping effect, which is dominant for pushers, is more sensitive to the distance between the squirmer and the polymers, whereas the rear-side polymer suction effect for pullers is more stable and less affected. As a result, when the repulsive boundary condition is applied, pushers are more strongly influenced. In the no-slip case, the reduction in fluid motility as \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\) decreases also leads to a decay of \({D}_{r}^{a}\) (Supplementary Fig. 6), which, together with the decrease of \({D}_{r}^{p}\), produces the characteristic boat-shaped trend of \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) for the pusher.

a Dependence of the rotational diffusion enhancement \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) for swimmers with no-slip (ns, dashed line) and repulsive (rp, solid line) boundary conditions on the Reynolds number at a temperature kBT/ϵ = 0.0005. Corresponding dependences of (b) the mean swimming velocity 〈U ⋅ e〉 and (c) translational diffusion enhancement \({D}_{t}^{a}/{D}_{t}^{p}\). Mean swimming velocities are normalized by their Newtonian fluid counterparts, 〈U⋅e〉N. Here, β denotes active stress. Blue, red, and green lines correspond to pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively. The dotted line represents the reference curve.

The influence of the Reynolds number on the swimming velocities is illustrated in Fig. 8(b), where decreases in swimming velocities are observed at all Reynolds numbers. Similarly, a critical Reynolds number is identified at \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}=0.2\), above which the no-slip boundary condition results in evidently lower swimming velocities compared to the repulsive case. This effect is attributed to the fact that the no-slip boundary condition allows polymers to approach squirmers more closely at finite \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\), where polymer motility is high. However, this difference becomes small for \({{{\rm{Re}}}} < {{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}\).

The dependence of translational diffusion enhancement on the Reynolds number is shown in Fig. 8(c). Monotonic decays are observed for all active stresses. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, since the variation of \({D}_{t}^{a}\) is small when increasing \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\), these decays are mainly attributed to the increase in the translational diffusivity of the passive colloid, leading to the \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}^{-1}\) dependence of \({D}_{t}^{a}/{D}_{t}^{p}\). The discrepancy between the no-slip and repulsive boundary conditions is evident above \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}\) for pusher and puller for pushers and pullers, but becomes subtle in the low-Re regime. In particular, the neutral swimmer and the pusher exhibit stronger translational diffusion compared to the puller. This difference stems from the puller’s more pronounced rotational motion, which results from the rear-side polymer suction effect. However, pusher with the no-slip boundary condition shows a similar enhancement to that of the puller in the finite-Re regime. This phenomenon originates from the strong front-side polymer wrapping effect at finite \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\), where the motility of the polymer remains high. This also leads to a reduction in the translational diffusivity of the pusher with the no-slip boundary condition compared to the repulsive case at finite \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\).

Other effects

The influences of the monomer packing fraction and the squirmer-polymer size ratio on the rotational and translational behavior of squirmers at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\) are discussed below. Given that the additional contributions from the no-slip boundary condition are minor in this regime, only the repulsive case is considered.

The dependence of rotational enhancements for squirmers with different active stresses on the monomer packing fraction are shown in Fig. 9. In the absence of polymers, the system remains homogeneous, resulting in squirmers with various active stresses exhibiting rotational diffusion coefficients nearly identical to that of a passive colloid. Accordingly, the corresponding rotational enhancements are nearly unity. However, these enhancements increase rapidly to 33 for a pusher and 56 for a puller when the packing fraction reaches ϕ/ϕ0 = 0.6. A 2.5-fold enhancement is observed for a neutral swimmer. Here, \({\phi }_{0}=3{N}_{m}/4\pi {R}_{g}^{3}=0.053\,{a}^{-3}\) is the overlap concentration for a flexible polymer of length Nm = 240 with an estimated radius of gyration Rg = 10.3 a at temperature kBT/ε = 0.0005. These enhancements arise from the increased system heterogeneity due to the embedded polymers63, which induce asymmetric flows around the swimmers and thus promote rotational diffusion. The enhancements become even more significant at ϕ/ϕ0 = 3.58, reaching 122 for the pusher, 148 for the puller, and 16 for the neutral swimmer. Beyond this point, \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) reaches a plateau for the pusher but starts to decrease for the puller, indicating a weakening of the asymmetric flows induced by the polymers and a transition of the system toward a more homogeneous phase63. For ϕ/ϕ0 > 4.7, the enhancement for a pusher would likely begin to decrease, and a maximum would be observed for a neutral swimmer. However, ϕ/ϕ0 alone does not determine the rotational enhancement of the squirmer. In a very dilute solution, although the system is more heterogeneous, the average time between two squirmer-polymer encounters is relatively long, so the accumulated effect remains weak. On the other hand, in a pure monomer solution, because monomers are homogeneously distributed, they encounter the squirmer uniformly during swimming, leading to no net force or torque and thus no rotational enhancement. Therefore, the globular structure of the polymer as a whole is essential for this effect. The influence of monomer packing fraction on the mean swimming velocity and translational diffusion coefficient is discussed in the Supplementary Fig. 8. In short, higher packing fractions lead to a sharp reduction in transport parameters due to enhanced rotational diffusion.

Here, β denotes active stress. Blue, red, and green lines correspond to pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively. The rotational motion of a passive colloid remains essentially unchanged with increasing ϕ, with a corresponding rotational diffusion coefficient \({D}_{r}^{p}=3.0\times 1{0}^{-9}\,{\tau }^{-1}\).

The dependence of rotational enhancements on the squirmer-polymer size ratio is investigated in Fig. 10. Swimmers with radii R = 3−6 a are considered. To prevent excessively strong flows that could break polymer bonds, a smaller swimming strength B1 = 0.003 is used. Consequently, the corresponding Reynolds numbers are \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.024\)-0.048, ensuring that the mechanisms governing transport and rotational properties remain intact. As shown in Fig. 10, the rotational diffusion coefficient of a passive colloid follows the Stokes-Einstein-Debye relation and decreases by about an order of magnitude as particle size increases. However, activity can compensate for this intrinsic decrease in Dr. The rotational diffusion coefficients of a pusher and a neutral swimmer decrease only by factors of 2 and 3, respectively, resulting in rotational motions that are up to 5 and 3 times stronger. Remarkably, the puller’s \({D}_{r}^{a}\) increases by a factor of 4 at R = 6 a, leading to a significant enhancement with \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}=1400\). This is attributed to the fact that a larger puller generates stronger and more stable rear flows that efficiently advect polymers to its vicinity. As a result, a noticeable increase in monomer density can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 9. These polymers induce intense asymmetric flows, thereby greatly enhancing the rotational motion of the puller (Supplementary Movie 13). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, the significant enhancement of puller rotation with increasing \(R/{\ell }_{0}^{n}\) leads to a sharp decay in the corresponding mean swimming velocity. In comparison, translational diffusion is less affected due to the compensating effects of \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) and 〈U ⋅ e〉/〈U⋅e〉N. For pushers and neutral swimmers, the mean swimming velocities are only weakly dependent on the size ratio and are accompanied by evident increases in translational diffusivity.

Dependence of (dashed lines) normalized rotational diffusion coefficients \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{0}\) and (solid lines) rotational enhancements \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) on particle radius. Here, β denotes active stress. Blue, red, and green lines correspond to pushers, pullers, and neutral swimmers, respectively. The monomer packing fraction is fixed at ϕ/ϕ0 = 1.13. Particle radii R are normalized by the polymer’s natural bond length \({\ell }_{0}^{n}=1a\). The theoretical rotational diffusion coefficient for a colloid of radius R = 3a at temperature kBT/ε = 0.0005 is \({D}_{r}^{0}=3.0\times 1{0}^{-9}\,{\tau }^{-1}\).

In addition, the effect of polymer length on the hydrodynamic behavior of squirmers is discussed in the supplemental materials. Specifically, for a puller with \(R/{l}_{0}^{n}=3\), the rotational enhancement increases by approximately 35% when shorter polymers (Nm = 60) are used. This moderate increase is primarily attributed to a reduction in the rotational diffusion of the passive colloid. However, this result should not be overemphasized, as the rotational enhancement \(\gamma ={D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) is highly sensitive to the values of the rotational diffusion coefficients, i.e., small variations in these parameters can lead to noticeable changes in γ. In contrast, the transport properties of squirmers are largely unaffected by changes in polymer length.

Discussion

Our previous work63 performed hydrodynamic simulations of a squirmer immersed in a polymer solution using multiparticle collision dynamics (MPC) at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=1.1\). That study focused on revealing the rotational enhancement of a neutral swimmer with surface attraction in a viscoelastic fluid. The amplification is a consequence of two effects, a decrease of the amount of adsorbed polymers by active motion and an asymmetric encounter with polymers on the squirmer surface. In comparison, the present work focuses on elucidating the influence of the Reynolds number on both the translational and rotational behavior of squirmers with various active stresses. Here, no surface attraction is employed. Instead, the influence of two boundary conditions, i.e., no-slip and purely repulsive, are examined. The hydrodynamic interactions due to active stress are sufficiently strong to induce profound effective attraction to the polymers. The observed rotational enhancements of pushers and pullers arise from distinct mechanisms driven by active stress. Specifically, polymer wrapping occurs in front of a pusher, while numerous polymers are absorbed in the rear of a puller. Both mechanisms enhance the rotational motion while simultaneously suppressing the swimming speed through forces and torques arising from direct contacts or asymmetric local flows induced by the polymers. One key result is the identification of a critical Reynolds number, \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}=0.2\). Above \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}\), the dominant inertial effects of the fluid efficiently advect polymers into the vicinity of the squirmer, leading to more pronounced rotational enhancement for swimmers under the no-slip boundary condition. However, in the low-Re regime, this effect diminishes because the strong viscous drag of the fluid impedes polymer advection toward the squirmer, resulting in similar rotational enhancements under both boundary conditions.

In experiments with Janus particles suspended in PAAm polymer solutions, rotational diffusion was found to increase by more than 400 times due to the fluid’s viscoelastic memory effect, where internal forces generated by deformed polymers lag behind the particle’s instantaneous motion61. At higher activity levels, this memory effect can even induce circular trajectories62. For comparison, using a water-PnP mixture with fluid density ρ ≈ 0.95 × 103 kg/m3, particle diameter 2R = 7.75 μm, swimming speed U0 = 0.25 μm/s, and viscosity η = 0.15 Pa ⋅ s, the Reynolds number is estimated as \({{{\rm{Re}}}}\approx 1.3\times 1{0}^{-8}\). The fluid stress-relaxation time is τ = 1.65 s, giving a Deborah number De = U0τ/2R = 0.05, which indicates predominantly viscous behavior. By contrast, our system reaches a much larger De = 20944 at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\). However, this does not imply strong elasticity, because the polymer relaxation is so slow that squirmers do not experience any noticeable elastic response. Instead, the pronounced enhancements in rotational diffusion observed in our simulations arise from direct mechanical and hydrodynamic interactions, such as front-side polymer wrapping for pushers and rear-side polymer suction for pullers.

On the other hand, Corato77 proposed that polar active particles can spontaneously develop chirality when a transient perturbation breaks the symmetry of the surrounding solute, generating a torque that spins the particle if solute diffusion is slower than advection. This mechanism can significantly enhance the rotational diffusion coefficient77. The key parameters are the solute concentration ϕ and the Péclet number, Pep = U0R/Dt. In our system (kBT/ε = 0.05, R3ϕ = 1.67), the solute diffusion coefficient Dt = 3.9 × 10−5, 4.5 × 10−6a2τ−1 yields Pep values of 256 (finite Reynolds number) and 2222 (low Reynolds number), or even higher at lower temperatures due to suppressed diffusion. According to Corato’s phase diagram, our systems remain in the polar regime, indicating that spontaneous chiralization is not the dominant mechanism governing the rotational behavior here.

A recent simulation using multiparticle collision dynamics (MPC) at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.1\) reported large reductions in swimming speeds up to 40% in flexible and 90% in semiflexible polymer solutions78. Whereas, our results show only about a 10% reduction. This discrepancy likely arises because MPC polymers can absorb significant kinetic energy directly from the squirmers, while in our inertialess polymer model, energy transfer occurs mainly through fluid-mediated interactions. Moreover, the MPC study found no clear increase in rotational diffusion, which may be attributed to their relatively high thermal energy (kBT/Et = 0.43). Here, \({E}_{t}=2/3\pi {R}^{3}\rho {U}_{0}^{2}=6.3\times 1{0}^{-4}m{a}^{2}/{\tau }^{2}\) is the reference translational kinetic energy of the squirmer. In comparison, our system features a much lower thermal energy (kBT/Et = 0.0016), allowing strong rotational diffusion enhancements to manifest. This comparison highlights that excessive thermal fluctuations can obscure the polymer-induced flow heterogeneity that influence squirmer rotation.

Ouyang79 recently investigated the swimming of spherical squirmers and squirmer dumbbells in an athermal viscoelastic fluid using the Giesekus model, focusing on how fluid inertia and elasticity affect swimmer motion. At \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=5\), all swimmers swam faster as the Weissenberg number (Wi) increased (analogous to our Deborah number), reaching a plateau for Wi > 8. Specifically, the swimming speed increased by 10% for neutral swimmers, 140% for pushers (β = − 5), and decreased slightly by 3% for pullers (β = 5). This behavior likely results from how fluid stresses are generated behind the squirmer, with higher Wi enhancing vorticity convection and thus boosting the swimming speeds of pushers and pullers. Differenly, our study at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.8\) showed a speed reduction of up to 10% for all swimmers at kBT/ε = 0.0005. This reduction occurs because the increased rotational motion of the swimmers hinders their forward propulsion. Ouyang’s work at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.01\) also showed decreased speeds with increasing Wi, plateauing for Wi > 14 (about 5% for neutral swimmers and pullers, 12.5% for pushers). Similarly, our system at \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0.04\) and kBT/ε = 0.0005 showed modest reductions: about 2% for neutral swimmers and pushers, and 5% for pullers. These differences likely arise because our model does not include elastic memory effects, and the additional rotational enhancement stems mainly from the interplay between swimmer-generated flow fields and polymer deformation.

Conclusions

In our study, we conducted comprehensive investigations into the transport and rotational properties of squirmers with different active stresses in polymer solutions using the Lattice-Boltzmann approach. To thoroughly elucidate the role of fluid viscoelasticity, we examined the swimming behavior of squirmers across a range of Reynolds numbers. The interplay among active stress, Reynolds number, and squirmer-polymer boundary conditions reveals rich dynamics. In particular, we identified a critical Reynolds number, \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{c}=0.2\), above which pronounced differences between the no-slip and repulsive boundary conditions emerge for both transport and rotational properties, whereas these differences become negligible in the low-Re regime. This transition is attributed to the competition between viscous and inertial forces: for \({{{\rm{Re}}}} > 0.2\), inertial forces dominate, resulting in strong fluid and polymer motility that enables closer contact between polymers and squirmers under the no-slip boundary condition. Consequently, compared to the repulsive case, additional momentum and angular momentum exchanges enhance the swimmers’ dynamics. In contrast, in the low-Re regime, the dominant viscous drag suppresses polymer motility, diminishing the additional contributions from the close-contact effect under the no-slip boundary condition.

Regarding the rotational diffusion, significant enhancements up to a factor of 1400 have been observed. These enhancements arise from the unique dynamics induced by active stress: specifically, polymer wrapping occurs in front of a pusher, while numerous polymers are absorbed at the rear of a puller. These interactions generate heterogeneous forces and torques or induce asymmetric local flows that amplify the squirmer’s rotational motion. However, the source dipole flow field of a neutral swimmer allows polymers to skim rapidly over its surface, resulting in no substantial enhancement. Furthermore, due to the minimal variations in the rotational diffusion coefficient (\({D}_{r}^{a}\)) for active swimmers and the sharp increases in \({D}_{r}^{p}\) for passive colloids, clear decreases in the ratio \({D}_{r}^{a}/{D}_{r}^{p}\) are evident with increasing Reynolds number.

In terms of transport properties, the presence of polymers increases the viscosity and, together with the enhanced rotational motion, results in swimming speed reductions of up to 10% for all types of squirmers compared to their Newtonian counterparts. Monotonic decreases in the translational diffusion enhancements are observed as the Re increases. Similar to the rotational diffusion, this trend primarily stems from the sharp increase in the translational diffusion coefficients of passive colloids (\({D}_{t}^{p}\)) and the relatively small variations in \({D}_{t}^{a}\) of the swimmers. In addition, pullers exhibit more pronounced decreases compared to pushers and neutral swimmers, attributed to their stronger rotational enhancement.

Our work highlights the crucial role of mechanical and hydrodynamic interactions between swimmers and polymers in shaping the behavior of squirmers in viscoelastic fluids. In particular, the system heterogeneity induced by dispersed polymers plays an essential role. To validate our results, a systematic comparison between real swimmers and squirmers was performed by matching the dimensionless Péclet number and Reynolds number (details in section 2.11 of Supplementary Discusssions). The consistency between experiments and simulations supports the validity of our results. However, the large Deborah numbers obtained in our simulations indicate that the relaxation process of locally deformed polymers is too slow to exhibit any significant elastic effect. Therefore, further investigation is demanded to determine whether the entangled polymer solution as a whole possesses substantial viscoelasticity. A limitation of our model arises when studying systems with multiple squirmers, as it does not allow for simulations at very high packing fractions. It is necessary to ensure sufficient spacing between squirmers to avoid discretization artifacts and issues related to unresolved lubrication forces. Adequate fluid nodes must be maintained between squirmers to preserve accurate hydrodynamic interactions and to prevent the formation of artificial vacuum regions.

Methods

The mesoscopic fluid environment is modeled using Lattice-Boltzmann (LB) simulations80,81,82,83 with the D3Q19 lattice scheme84. Unlike fully resolved hard-sphere models with stick boundary conditions, which have been successfully applied to colloidal systems85,86,87, flexible polymers in this study are represented by a bead-spring model (Fig. 1, 1.2 Flexbile polymer model in Supplementary Methods). Monomers are treated as point particles acting as force monopoles81, known as Stokeslets, which exert forces on the fluid. In contrast to previous works88,89, monomer inertia is not included, as it does not play a significant role in determining the dynamics-particularly the rotational motion-of swimmers in such complex environments. However, the inertia of the fluid itself is retained in the simulations. As shown in Fig. 1, a spherical squirmer73,74, modeled as a buoyant hard sphere with a prescribed tangential surface slip velocity

is employed to represent the microswimmer in this study. Here, B1 is the first surface velocity mode, θ is the polar angle with respect to the squirmer’s orientation e, and eθ denotes the local tangent vector. The self-propulsion mechanism is characterized by the active stress β, i.e., β > 0 corresponds to a puller, β = 0 to a neutral swimmer, and β < 0 to a pusher63,71,72. At \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=0\) in a Newtonian fluid, the swimming speed U0 = 2/3B1 is determined by the strength of the first surface mode B1. A slight deviation from the theoretical estimate occurs in the low Reynolds number regime. In this work, B1 = 0.005 is utilized. To prevent fluid from penetrating the squirmer, the no-slip boundary condition is enforced87. We investigate the influence of two types of polymer-squirmer boundary conditions on the squirmer’s dynamics. Similar to the fluid-squirmer interaction, a no-slip boundary condition between a squirmer and a monomer is first implemented. For comparison, the effect of a purely repulsive boundary condition on the squirmer’s behavior is also examined. Although no net torque is directly generated during these interactions, the presence of polymers near the squirmer can induce asymmetric flows, thereby indirectly affecting its translational and rotational properties. Further details of the simulation methods and models are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

The rotational and translational properties of various squirmers immersed in polymer solutions are investigated. The influence of fluid inertia and viscous forces is examined across a range of Reynolds numbers, \({{{\rm{Re}}}}=2R\rho {U}_{0}/\eta =0.04-0.8\), where the fluid viscosities vary between η = 0.025 − 0.5 m/(a τ). The squirmer radius is R = 3a and the fluid density is ρ = 1 m/a3. To characterize the viscoelasticity of the fluids, the corresponding Deborah numbers, De = U0τp/2R = 2789, 20944, are estimated at a temperature of kBT = 10−4 ma2/τ2. Here, the longest polymer relaxation times, τp ≈ 5 × 106, 3.8 × 107 τ, are determined by calculating the end-to-end vector correlation functions, which exhibit exponential decay90. In general, the fluid shows elastic behavior if De ≫ 1, whereas viscous forces dominate when De ≪ 1. However, the very large Deborah numbers in this study do not necessarily imply strong fluid elasticity. In fact, the relaxation of locally deformed polymers during squirmer self-propulsion is too slow for elastic forces to significantly influence the swimmer dynamics. Therefore, the notable enhancements in rotational motion and the reduction in swimming speeds are primarily attributed to the mechanical and hydrodynamic interactions between squirmers and polymers.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The complete code of this study is openly accessible via GitHub repository [https://github.com/ludwig-cf/ludwig].

References

Reynolds, O. Xxix. an experimental investigation of the circumstances which determine whether the motion of water shall be direct or sinuous, and of the law of resistance in parallel channels. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 174, 935–982 (1883).

Rott, N. Note on the history of the reynolds number. Annu. Rev. fluid Mech. 22, 1–12 (1990).

Wolgemuth, C. W. Collective swimming and the dynamics of bacterial turbulence. Biophys. J. 95, 1564–1574 (2008).

Bennett, R. R. & Golestanian, R. A steering mechanism for phototaxis in chlamydomonas. J. R. Soc. Interface 12, 20141164 (2015).

Brette, R. Integrative neuroscience of paramecium, a “swimming neuron”. Eneuro 8, ENEURO.0018-21.2021 (2021).

Li, G., Ostace, A. & Ardekani, A. M. Hydrodynamic interaction of swimming organisms in an inertial regime. Phys. Rev. E 94, 053104 (2016).

Dombrowski, C., Cisneros, L., Chatkaew, S., Goldstein, R. E. & Kessler, J. O. Self-concentration and large-scale coherence in bacterial dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 098103 (2004).

Sokolov, A., Aranson, I. S., Kessler, J. O. & Goldstein, R. E. Concentration dependence of the collective dynamics of swimming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 158102 (2007).

Wu, X.-L. & Libchaber, A. Particle diffusion in a quasi-two-dimensional bacterial bath. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3017 (2000).

Williams, B., Anand, S., Rajagopalan, J. & Saif, M. A self-propelled biohybrid swimmer at low reynolds number. Nat. Commun. 5, 3081 (2014).

Garcia, M., Berti, S., Peyla, P. & Rafaï, S. Random walk of a swimmer in a low-reynolds-number medium. Phys. Rev. E 83, 035301 (2011).

Qiu, T. et al. Swimming by reciprocal motion at low reynolds number. Nat. Commun. 5, 5119 (2014).

Han, E., Zhu, L., Shaevitz, J. W. & Stone, H. A. Low-reynolds-number, biflagellated quincke swimmers with multiple forms of motion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2022000118 (2021).

Park, S.-J. et al. Phototactic guidance of a tissue-engineered soft-robotic ray. Science 353, 158–162 (2016).

Feldmann, D., Das, R. & Pinchasik, B.-E. How can interfacial phenomena in nature inspire smaller robots. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2001300 (2021).

Chisholm, N. G., Legendre, D., Lauga, E. & Khair, A. S. A squirmer across reynolds numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 796, 233–256 (2016).

Cavaiola, M. & Mazzino, A. Self-propelled slender objects can measure flow signals net of self-motion. Phys. Fluids 33, 053603 (2021).

Cavaiola, M. Swarm of slender pusher and puller swimmers at finite reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids 34, 027113 (2022).

Dombrowski, T. & Klotsa, D. Kinematics of a simple reciprocal model swimmer at intermediate reynolds numbers. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5, 063103 (2020).

Dombrowski, T. et al. Transition in swimming direction in a model self-propelled inertial swimmer. Phys. Rev. Fluids 4, 021101 (2019).

Derr, N. J., Dombrowski, T., Rycroft, C. H. & Klotsa, D. Reciprocal swimming at intermediate reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 952, A8 (2022).

Dombrowski, T., Nguyen, H. & Klotsa, D. Pairwise interactions between model swimmers at intermediate reynolds numbers. Phys. Rev. Fluids 7, 074401 (2022).

Kokot, G. et al. Active turbulence in a gas of self-assembled spinners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12870–12875 (2017).

Li, G., Lauga, E. & Ardekani, A. M. Microswimming in viscoelastic fluids. J. Non Newton. Fluid Mech. 297, 104655 (2021).

Katz, D., Mills, R. & Pritchett, T. The movement of human spermatozoa in cervical mucus. Reproduction 53, 259–265 (1978).

Katz, D. & Berger, S. Flagellar propulsion of human sperm in cervical mucus. Biorheology 17, 169–175 (1980).

Katz, D., Bloom, T. & Bondurant, R. Movement of bull spermatozoa in cervical mucus. Biol. Reprod. 25, 931–937 (1981).

Suarez, S. S. & Dai, X. Hyperactivation enhances mouse sperm capacity for penetrating viscoelastic media. Biol. Reprod. 46, 686–691 (1992).

Suarez, S. S. & Pacey, A. Sperm transport in the female reproductive tract. Hum. Reprod. update 12, 23–37 (2006).

Fauci, L. J. & Dillon, R. Biofluidmechanics of reproduction. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 38, 371–394 (2006).

Hyakutake, T., Suzuki, H. & Yamamoto, S. Effect of non-newtonian fluid properties on bovine sperm motility. J. Biomech. 48, 2941–2947 (2015).

O’Toole, G., Kaplan, H. B. & Kolter, R. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 49–79 (2000).

Donlan, R. M. Biofilms: microbial life on surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 881 (2002).

Costerton, J. W. et al. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41, 435–464 (1987).

Costerton, J. W., Lewandowski, Z., Caldwell, D. E., Korber, D. R. & Lappin-Scott, H. M. Microbial biofilms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49, 711–745 (1995).

Wilking, J. N., Angelini, T. E., Seminara, A., Brenner, M. P. & Weitz, D. A. Biofilms as complex fluids. MRS Bull. 36, 385–391 (2011).

Yazdi, S. & Ardekani, A. M. Bacterial aggregation and biofilm formation in a vortical flow. Biomicrofluidics 6, 044114 (2012).

Bar-Zeev, E., Berman-Frank, I., Girshevitz, O. & Berman, T. Revised paradigm of aquatic biofilm formation facilitated by microgel transparent exopolymer particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9119–9124 (2012).

Karimi, A., Karig, D., Kumar, A. & Ardekani, A. Interplay of physical mechanisms and biofilm processes: review of microfluidic methods. Lab Chip 15, 23–42 (2015).

Montecucco, C. & Rappuoli, R. Living dangerously: how helicobacter pylori survives in the human stomach. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 457–466 (2001).

Celli, J. P. et al. Helicobacter pylori moves through mucus by reducing mucin viscoelasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14321–14326 (2009).

Luo, M., Feng, Y., Wang, T. & Guan, J. Micro-/nanorobots at work in active drug delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706100 (2018).

Ullrich, F. et al. Mobility experiments with microrobots for minimally invasive intraocular surgery. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 2853–2863 (2013).

Wang, J., Dong, R., Wu, H., Cai, Y. & Ren, B. A review on artificial micro/nanomotors for cancer-targeted delivery, diagnosis, and therapy. Nano Micro Lett. 12, 1–19 (2020).

Shen, X. & Arratia, P. E. Undulatory swimming in viscoelastic fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 208101 (2011).

Zhu, L., Lauga, E. & Brandt, L. Self-propulsion in viscoelastic fluids: pushers vs. pullers. Phys. fluids 24, 051902 (2012).

Qin, B., Gopinath, A., Yang, J., Gollub, J. P. & Arratia, P. E. Flagellar kinematics and swimming of algal cells in viscoelastic fluids. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–7 (2015).

Datt, C., Natale, G., Hatzikiriakos, S. G. & Elfring, G. J. An active particle in a complex fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 823, 675–688 (2017).

Patteson, A., Gopinath, A., Goulian, M. & Arratia, P. Running and tumbling with e. coli in polymeric solutions. Sci. Rep. 5, 15761 (2015).

Berg, H. C. & Turner, L. Movement of microorganisms in viscous environments. Nature 278, 349–351 (1979).

Teran, J., Fauci, L. & Shelley, M. Viscoelastic fluid response can increase the speed and efficiency of a free swimmer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 038101 (2010).

Espinosa-Garcia, J., Lauga, E. & Zenit, R. Fluid elasticity increases the locomotion of flexible swimmers. Phys. Fluids 25, 031701 (2013).

Martinez, V. A. et al. Flagellated bacterial motility in polymer solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17771–17776 (2014).

Jung, S. Caenorhabditis elegans swimming in a saturated particulate system. Phys. Fluids 22, 031903 (2010).

Leshansky, A. Enhanced low-reynolds-number propulsion in heterogeneous viscous environments. Phys. Rev. E 80, 051911 (2009).

Gómez, S., Godínez, F. A., Lauga, E. & Zenit, R. Helical propulsion in shear-thinning fluids. J. Fluid Mech. 812, R3 (2017).

Magariyama, Y. & Kudo, S. A mathematical explanation of an increase in bacterial swimming speed with viscosity in linear-polymer solutions. Biophys. J. 83, 733–739 (2002).

Zöttl, A. & Yeomans, J. M. Enhanced bacterial swimming speeds in macromolecular polymer solutions. Nat. Phys. 15, 554–558 (2019).

Zhu, L., Do-Quang, M., Lauga, E. & Brandt, L. Locomotion by tangential deformation in a polymeric fluid. Phys. Rev. E 83, 011901 (2011).

Thomases, B. & Guy, R. D. Mechanisms of elastic enhancement and hindrance for finite-length undulatory swimmers in viscoelastic fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 098102 (2014).

Gomez-Solano, J. R., Blokhuis, A. & Bechinger, C. Dynamics of self-propelled janus particles in viscoelastic fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 138301 (2016).

Narinder, N., Bechinger, C. & Gomez-Solano, J. R. Memory-induced transition from a persistent random walk to circular motion for achiral microswimmers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 078003 (2018).

Qi, K., Westphal, E., Gompper, G. & Winkler, R. G. Enhanced rotational motion of spherical squirmer in polymer solutions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 068001 (2020).

Liu, S., Shankar, S., Marchetti, M. C. & Wu, Y. Viscoelastic control of spatiotemporal order in bacterial active matter. Nature 590, 80–84 (2021).

Narinder, N., Gomez-Solano, J. R. & Bechinger, C. Active particles in geometrically confined viscoelastic fluids. N. J. Phys. 21, 093058 (2019).

Bozorgi, Y. & Underhill, P. T. Effect of viscoelasticity on the collective behavior of swimming microorganisms. Phys. Rev. E 84, 061901 (2011).

Bozorgi, Y. & Underhill, P. T. Role of linear viscoelasticity and rotational diffusivity on the collective behavior of active particles. J. Rheol. 57, 511–533 (2013).

Bozorgi, Y. & Underhill, P. T. Effects of elasticity on the nonlinear collective dynamics of self-propelled particles. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 214, 69–77 (2014).

Li, G. & Ardekani, A. M. Collective motion of microorganisms in a viscoelastic fluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 118001 (2016).

Tung, C.-k et al. Fluid viscoelasticity promotes collective swimming of sperm. Sci. Rep. 7, 3152 (2017).

Alarcón, F. & Pagonabarraga, I. Spontaneous aggregation and global polar ordering in squirmer suspensions. J. Mol. Liq. 185, 56–61 (2013).

Kuron, M., Stärk, P., Burkard, C., De Graaf, J. & Holm, C. A lattice boltzmann model for squirmers. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 144110 (2019).

Lighthill, M. On the squirming motion of nearly spherical deformable bodies through liquids at very small reynolds numbers. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 5, 109–118 (1952).

Blake, J. R. A spherical envelope approach to ciliary propulsion. J. Fluid Mech. 46, 199–208 (1971).

Theers, M., Westphal, E., Gompper, G. & Winkler, R. G. Modeling a spheroidal microswimmer and cooperative swimming in a narrow slit. Soft Matter 12, 7372–7385 (2016).

Binagia, J. P., Phoa, A., Housiadas, K. D. & Shaqfeh, E. S. Swimming with swirl in a viscoelastic fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 900, A4 (2020).

De Corato, M., Pagonabarraga, I. & Natale, G. Spontaneous chiralization of polar active particles. Phys. Rev. E 104, 044607 (2021).

Zöttl, A. Dynamics of squirmers in explicitly modeled polymeric fluids (a). Europhys. Lett. 143, 17003 (2023).

Ouyang, Z., Lin, Z., Lin, J., Phan-Thien, N. & Zhu, J. Swimming of an inertial squirmer and squirmer dumbbell through a viscoelastic fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 969, A34 (2023).

Dünweg, B. & Ladd, A. J. Lattice boltzmann simulations of soft matter systems. In Advanced Computer Simulation Approaches for Soft Matter Sciences III. Advances in Polymer Science, (eds. Holm, C., Kremer, K.) 221 (Springer, 2009).

Nash, R. W., Adhikari, R. & Cates, M. E. Singular forces and pointlike colloids in lattice boltzmann hydrodynamics. Phys. Rev. E 77, 026709 (2008).

Pozrikidis, C. et al. Boundary Integral and Singularity Methods for Linearized Viscous Flow 1st edn, Vol. 272 (Cambridge university press, 1992).

Peskin, C. S. The immersed boundary method. Acta Numerica 11, 479–517 (2002).

Stratford, K. & Pagonabarraga, I. Parallel simulation of particle suspensions with the lattice boltzmann method. Comput. Math. Appl. 55, 1585–1593 (2008).

Ladd, A. J. Numerical simulations of particulate suspensions via a discretized boltzmann equation. part 1. theoretical foundation. J. Fluid Mech. 271, 285–309 (1994).

Ladd, A. J. Numerical simulations of particulate suspensions via a discretized boltzmann equation. part 2. numerical results. J. Fluid Mech. 271, 311–339 (1994).

Nguyen, N.-Q. & Ladd, A. Lubrication corrections for lattice-boltzmann simulations of particle suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 66, 046708 (2002).

Ahlrichs, P. & Dünweg, B. Simulation of a single polymer chain in solution by combining lattice boltzmann and molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 8225–8239 (1999).

Berk Usta, O., Ladd, A. J. & Butler, J. E. Lattice-boltzmann simulations of the dynamics of polymer solutions in periodic and confined geometries. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 094902 (2005).

Huang, C.-C., Winkler, R. G., Sutmann, G. & Gompper, G. Semidilute polymer solutions at equilibrium and under shear flow. Macromolecules 43, 10107–10116 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support from the Swiss National Science Foundation program “Computational modeling at CECAM. Challenges in the foundations and modeling of systems far away from equilibrium (200021_175719)” and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12304257 and 12574237). The authors gratefully acknowledge the computing time granted on the supercomputer Piz Daint at Centro Svizzero di Calcolo Scientifico CSCS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and K.Q. performed simulations, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. K.Q. and K.S. developed the code. M.D.C. joined the discussions. I.P. supervised the study. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Zhaowu Lin, Nicholas Chisholm and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, K., Zhou, Y., De Corato, M. et al. Unravel the rotational and translational behavior of a single squirmer in flexible polymer solutions at different Reynolds numbers. Commun Phys 8, 487 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02391-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02391-9