Abstract

Understanding microscopic thin-film stability is key to macroscopic stability in foams, emulsions, lung surfactants, wetting/dewetting, and microfluidics. However, the interplay of stresses in thin films remains unclear. Here, we experimentally investigate the evolution of Marangoni stresses and disjoining pressure in surfactant-stabilized air/liquid films. Using a thin-film balance and comparing charged and uncharged fluorescent lipids, we directly observe surfactant concentration gradients at the film interface, revealing pronounced asymmetry and highly localized convective flows. The results suggest an interplay between Marangoni stresses and local disjoining pressure. Specifically, a local decrease in surfactant concentration not only induces lateral stresses but also weakens the local increase in disjoining pressure as film thickness decreases. This interplay redistributes stresses, with more stable regions reinforcing weaker ones. Localized unstable flows ultimately prolong film lifetimes by dissipating stresses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Foams and emulsions are high interface materials of industrial relevance, with applications spanning food technology1, energy2, and healthcare3. These materials are biphasic systems composed of bubbles or droplets separated by thin liquid films (TLFs). The macroscopic material behavior is related to these thin film lifetimes, and often drainage is the rate-limiting step, before the TLFs rupture4,5,6,7,8,9. These films are high aspect ratio structures where a complex balance between hydrodynamics, capillarity, and molecular forces, is convoluted by surfactant transport, and interfacial rheology10,11,12,13. Their complex motions induce thickness variations that, through thin-film interference, produce the striking colors observed in soap films.

Among the forces influencing thin film stability, the equilibrium disjoining pressure acting normal to the two interfaces, being the effect of molecular forces, is the most studied and arguably the best understood14,15,16. These forces typically strongly increase as the film thickness decreases. Van der Waals attraction17,18,19 generally destabilizes the film, while electrostatic repulsion charges are present at the interface-increases stability and extends the film’s lifetime20,21.

The hydrodynamic drainage of TLFs however, alters pressure distribution, driving an intricate dynamic interplay between viscous stresses and surface tension forces. As the film thins, thickness and velocity gradients generate pressure variations that feed back into the governing Stokes’ equations. A common dimensionless parameter to quantify the relative importance of viscous forces to surface tension is the Capillary number, defined as:

Where η is the viscosity of the thin film, U is a characteristic velocity (e.g., the drainage velocity), and γ is the interfacial tension. Under high capillary number dimpling of the thin film arises because viscous forces dominate over surface tension forces, causing the center region of the film to drain more slowly. This leads to a localized thickening, or “dimple,” in the thinning liquid film. An increase in the Capillary number (Ca) tends to amplify and sustain the dimple in a draining liquid film due to surface tension. However, in the presence of bulk or interfacial species, interfacial velocity can generate lateral concentration gradients through advection, leading to tangential stresses. For soluble polymers, these gradients can also induce bulk osmotic forces that can stabilize instabilities22. In surfactant-stabilized systems, such gradients give rather rise to interfacial solutal Marangoni stresses, particularly when interfacial viscosity is negligible and surfactant coverage is intermediate11,23,24,25,26.

These stresses stabilize the film through a feedback mechanism: as flow depletes surfactants from the film center, the resulting interfacial tension gradient induces a counter flow that opposes hydrodynamic drainage. Although numerical simulations provided insights into how Marangoni stresses stabilize thin liquid films27, experimental validation of the detailed mechanism has been challenging. One primary difficulty lies in accurately measuring how surfactants are distributed within the film, as well as in disentangling the complex interplay between tangential Marangoni forces and normal disjoining pressures. Moreover, many experiments reveal pronounced instabilities in films under Marangoni-driven flows - an observation that seemingly departs from or contradicts the stabilizing predictions and underscores the need for further investigation into the mechanisms. But it is clear that Marangoni stresses affect film lifetime, induce local film deformations28, and can drive symmetry breaking and instabilities29. Both numerical and experimental studies have shown that the Marangoni effect changes local boundary conditions, though the nature of this change remains debated. Some propose a transition from mobile to immobile boundary conditions, either within the film30,31,32 or in the plateau border33, others argue that Marangoni stresses are compatible with mobile interfaces but should be interpreted in terms of stress distributions25,34,35. Experimental efforts have been made to quantify these stresses through the Marangoni number (Ma)36. However, considering interfacial convection, the Marangoni times the surface Péclet number (Ma ⋅ PeS) has been proposed to be the more relevant metric for quantifying Marangoni stresses37.

In this study, we use the Dynamic Thin Film Balance (DTFB) apparatus along with charged and uncharged fluorescent surface-active lipids in a liquid-expanded state to furthermore directly visualize in-plane surfactant concentrations during dynamic film drainage and simultaneously investigate their effect on disjoining pressure, through spatially resolved thickness profiles. To this end, we introduce a method to separate the interfacial fluorescence signal from optical interference effects. Using the local measurement in surfactant concentration during drainage, we assess the difference between measured disjoining pressure at equilibrium and the apparent lower disjoining pressure during drainage due to lowering of interfacial concentration. In the present work we experimentally quantify the increase of local Marangoni stresses with increasing Capillary number (Ca). We propose a simple scaling relation for the surface velocity to rationalize this trend and reflect on the coupling of tangential Marangoni stresses to normal disjoining pressure. This enables a 2D visualization of the disjoining pressure and estimate the vector field of Marangoni stresses in the draining film, which suggests an interplay between normal and tangential forces. The different dependencies of the tangential and normal forces on local concentration and thickness seem to lead to unstable flow patterns, which are known to be a signature of Marangoni flows in thin films7. Despite the local unstable nature these interfacial flows dissipate energy and lead to a macroscopic stabilization of the thin film, enhancing the lifetime. In the low Ma ⋅ PeS regime, the thin film lifetime is mainly determined by the disjoining pressure and is independent of the applied pressure. In contrast, at higher Ma ⋅ PeS numbers, Marangoni stresses and the resulting local interfacial flows stabilize the film during drainage, prolonging its overall lifetime. Maps of the normal and tangential interfacial stresses show how coupling between lateral and normal stresses shapes the local flow profiles, ultimately influencing the film’s evolution. These maps could motivate further computational studies of the role of local instabilities in determining the macroscopic stability of such thin-film system.

Results and Discussion

Separating the different contributions

The draining films exhibit variations in both thickness and surface concentration. To analyze the magnitudes of forces in the horizontal and vertical directions, it is essential to relate surface concentration variations to the stresses that develop: Marangoni stresses in the horizontal direction and variations in disjoining pressure in the vertical direction. To achieve a quantitative understanding, we must first decouple thickness and concentration measurements, then quantify the Marangoni stresses, and finally establish a framework to connect these stresses with the observed film dynamics.

Decoupling fluorescence interference from the thickness variations

Figure 1 provides a comparative visualization of two typical stages in a drainage experiment. The top row represents the early stages of drainage in the thin film regime, immediately after dimple wash-out. The bottom row shows a snapshot during the development of Common Black Films (CBF). The first two columns display Bright Field (BF) and fluorescence images. The BF images reflect the thickness profile38,39,40,41,42, while the fluorescence images contain information about concentration distribution. In the raw fluorescence images, patterns similar to those in the BF interference images are visible. However, a discontinuity between the developing CBF and the surrounding thicker film indicates interference that must be corrected to accurately determine the surfactant concentration gradient at the interface. A simple linear subtraction will not work43,44,45. To deconvolute the interference effects we developed a procedure described fully in the Supplementary Notes 1 and 2, with the final resulting correction formula:

With, Irec the raw recorded fluorescence (from Fig. 1a.2, b.2), Ifluo the corrected fluorescence intensity for a single interface, IBF the bright field interference image (from Fig. 1a.1, b.1), IBF-Max and IBF-Min the maximum and minimum bright field intensity. The result of the reconstruction procedure is shown in Fig. 1a.3 and Fig. 1b.3. After correction, fluorescence interference is no longer apparent in the thicker film (Fig. 1b.3). Because small intensity mismatches can occur at the moving boundary between the thick film and the CBF during expansion, we quantify NBD-PC concentrations and gradients only once the CBF is fully developed. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, and owing to a slight mismatch between λBF and λem, we are confident in the accuracy of this method for first-order bright-field interference only (for NBD-PG). Therefore, higher-order regions of the TLF will be excluded from further analysis, as their thickness reconstruction would require more advanced numerical analysis.

a, b Set of representative images during the final stage of film thinning for an imposed pressure jump of ΔP = 250 Pa with NBD-PC surfactant with a) being typical for the stages, right after dimple wash-out and (b) in the regime of Common Black Film (CBF) formation. Columns correspond to: (a.1, b.1) Bright-field images, (a.2, b.2) recorded fluorescence intensity, and (a.3, b.3) corrected fluorescence intensity using Eq. (2) and scale directly with the in plane concentration in surfactants. Gray scale indicates normalized pixel intensity Ī. The interface equilibrium concentration is approximately Γeq = 1.32 ± 0.17 molecules.nm−2. The scale bar is defined in (a.1n) and is consistent throughout the figure.

Local disjoining pressure

Disjoining pressure (Πdisj) is a force in thin liquid films arising from interactions such as molecular, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces between the two surfaces. It governs the film’s stability and thickness, balancing external pressures like capillary and hydrodynamic forces. Disjoining pressure varies with changes in film thickness and surface concentration, as well as their combined effects. To evaluate these effects in the present systems we define:

Where ΠVdW and Πelec are respectively the attractive Van der Waals force17,18,46 and the repulsive electrostatic contribution20,46. In the present study, the minimum film thickness is observed to be never below 10 nm, indicating that the lipid molecules and films remain hydrated and do not reach a pure bilayer thickness (hBL) of approximately 4.21 nm (value for POPC, a lipid analogous to NBD-PC47). This is consistent with earlier results (also in the absence of salt)48. Consequently, steric repulsion forces in the CBF49,50,51 can be neglected. Hereafter, we refer to the thinnest state of the film as the Common Black Film (CBF). ΠVdW can be express as:

where AH is the non-modified Hamaker constant defined in Supplementary Note 4.

Here, for Πelec, we introduce a concentration-dependent model inspired by the treatment in Israelachvili46, where two analytical limits exist: (i) the Langmuir, high-potential regime where Πelec no longer depends on surface coverage, Γ, and (ii) the Debye-Hückel, low-potential regime where Πelec ∝ Γ2, as derived by Philipse and coworkers52,53. Moreover in this regime the exponential decay, can be approximated by an algebraic form for the dependency on thickness Πelec ∝ h−2, and the resulting equation reads

Where, ϵ0 and ϵb represent the dielectric constants of vacuum and the bulk phase, respectively, e is the elementary charge, and kBT is the thermal energy. Ceq is a dimensionless charge factor, determined here as a fitting parameter from disjoining pressure experiments at equilibrium, where the interfacial concentration is homogeneous (Γ = Γeq). Physically, Ceq reflects the effective charge per surfactant, influenced by counter-ion dissociation and the surfactant’s nominal charge. We checked the quadratic dependency of the disjoining pressure on concentration experimentally in Supplementary Fig. 4 and the quality of the fits with the algebraic form was found to be sufficient (see below).

Experimental data and model fits are shown in Fig. 2a for NBD-PC and Fig. 2b for NBD-PG, with further details in Supplementary Fig. 3 on raw data. These disjoining pressure effects are illustrated in Fig. 3a. Fitting Eq. (3) to our disjoining pressure data, we find Ceq = 0.699 ± 0.001 (R2 = 0.90) for NBD-PC and Ceq = 1.290 ± 0.004 (R2 = 0.87) for NBD-PG. From the disjoining pressure experiments, the CBF thickness is estimated to be hCBF = 10 nm for NBD-PC and hCBF = 16 nm for NBD-PG. As expected from refs. 54,55, even zwitterionic lipids (NBD-PC) exhibit a low, but non-zero, effective charge at the interface, explaining the repulsive component of their disjoining pressure. The higher charge factor, measured disjoining pressure, and greater CBF thickness for NBD-PG are consistent with its expected higher charge compared to zwitterionic lipids. However, the charge factors differ by only a factor of two, indicating low charge dissociation for net-charged surfactants. In our experiments this implies that variations in disjoining pressure arise primarily from differences in interfacial concentration.

Results for NBD-PC and NBD-PG under equilibrium and dynamic conditions are presented in panels (a, b), respectively. Πdisj denote the disjoining pressure and h is the thickness of the film. Experimental equilibrium data fall within the light blue regions (95% confidence interval) the solid blue line being the average data. The purple line represent the predicted equilibrium curve from Eq. (3), Γeq = 1.32 ± 0.17 molecules.nm−2 for NBD-PC and Γeq = 1.42 ± 0.13 molecules.nm−2 for NBD-PG. The disjoining pressure during drainage for the dynamically diluted interface, estimated from Eq. (3), is shown in red. The solid line represents the estimate based on the average local concentration, ΓMax-Ma = 0.90 ± 0.1 molecules.nm−2 for NBD-PC and ΓMax-Ma = 0.79 ± 0.04 molecules.nm-2 for NBD-PG, while the shaded area’s bounds correspond to the lowest and highest estimates of the local concentration, respectively.

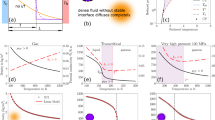

a Schematic of Van der Waals (ΠVdW) and electrostatic (Πelec) normal disjoining pressures, and Marangoni tangential stresses (σMa) acting on a draining thin liquid film. Blue arrows indicate the drainage flow of the bulk fluid (light blue), while surfactants are shown at the air-liquid interface. b Schematic of the parameters used in the Marangoni local stress relation Eq. (13), in the CBF limit. The surface velocity is denoted as us. c Maximum Marangoni stress (σMax-Ma) as a function of the Capillary number for the NBD-PC (red) and NBD-PG (blue). d Non-dimensionalized values versus Ca. e, f Experimental data (red) and analytical relation predictions based on the right term of Eq. (13) (green) for NBD-PC (e) and NBD-PG f), respectively. In (e, f), the results are rescaled relative to the value at ΔP = 50 Pa, using σMax-Ma(ΔP) − σMax-Ma(ΔP = 50 Pa). Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval, calculated using Student’s t-distribution and appropriate error propagation for combined data sets. The shaded areas in (e, f) connect consecutive error-bar extrema and serve as a visual guide for comparing experimental data with the analytical relationship.

Equilibrium disjoining pressure measurements are conducted under conditions of homogeneous surface concentration. Therefore, the purple curves correspond to the classical disjoining pressure experiments’ model fitting. However, as shown in Fig. 1b.3, significant variations in surface concentration can occur during drainage. We define ΓMax-Ma as the interfacial concentration at the location of maximum Marangoni stresses σMax-Ma during drainage experiments, while Γeq is measured from the average concentration during disjoining pressure experiments. The measured average concentrations are Γeq = 1.32 ± 0.17 molecules.nm−2 and ΓMax-Ma = 0.90 ± 0.1 molecules.nm−2 for NBD-PC, and Γeq = 1.42 ± 0.13 molecules.nm−2 and ΓMax-Ma = 0.79 ± 0.04 molecules.nm-2 for NBD-PG. The lower surfactant concentrations result from surfactant exchange with the plateau border. In Fig. 2, the estimated disjoining pressure during drainage (which we can understand as being “dynamically diluted”) is plotted in red. In both cases, as the film thickness decreases, a significant deviation in disjoining pressure can be observed compared to the equilibrium estimate. This clearly demonstrates that assuming dynamic drainage and equilibrium disjoining pressures to be equivalent-a common approach-substantially overestimates the local disjoining pressure in the film, by a maximum factor of 3.5. The assumption of negligible bleaching to come to this conclusion is discussed in the Supplementary Note 6 while all numerical parameters used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Quantitative analysis of spatial Marangoni stresses

Marangoni stresses result from spatial gradients in surface tension quantified here by dγ/dr and act tangentially along the TLF interface, as shown in Fig. 3a. These stresses can be directly determined from the spatial gradient in fluorescence intensity, which reflects the surfactant distribution, using calibration procedures detailed in Supplementary Note 5. It is important to note that, in this section, the non-dimensional form of the Marangoni stresses is independent of the absolute surface tension values, assuming a linear relationship between surface tension and interfacial concentration, as justified by the calibration procedure. Only the norms of the Marangoni stresses depend on the surface tension itself. These values may represent a lower bound, as we use the equilibrium surface tension rather than the dynamic surface tension, which is more difficult to estimate but may be more relevant in the context of dynamic drainage. Raw data for fluorescence intensity and intensity gradients, during drainage experiments, are provided in Supplementary Figs. 8 and 11.

Results are expressed in terms of the Capillary number, now written in terms of the experimental control parameters, i.e., Ca = ΔP/PLap-eq, where ΔP is the applied TFB pressure and PLap-eq is the initial equilibrium Laplace pressure before drainage. PLap-eq is calculated as: PLap-eq = 2γeq/RCi, where γeq = γ(Γeq) is the measured equilibrium surface tension, and \({R}_{{{{\rm{Ci}}}}}=({R}_{{{{\rm{TFB}}}}}^{2}+{H}_{{{{\rm{TFB}}}}}^{2})/2{H}_{{{{\rm{TFB}}}}}\) = 0.725 mm is the initial radius of curvature of the interface at equilibrium before drainage begins. For NBD-PC γeq = 61.8 ± 0.9 mN.m−1 and for NBD-PG γeq = 65.7 ± 0.3 mN.m−1. In this section, we focus on the maximum value of the Marangoni stresses (σMax-Ma) measured in the TLFs. The results are shown in Fig. 3c. Since Marangoni stress should be absent when no stress is applied, we subtract a constant baseline noise estimated at the CBF opening below 50 Pa drainage pressure, where observed concentration gradients are negligible (SNR < 3) as shown in Supplementary Note 7. This correction ensures that the maximum stress values in Fig. 3c remain physically consistent. The Marangoni stresses for both charged (NBD-PG) and uncharged (NBD-PC) surfactants increase with the Capillary number (Ca). Within the studied Ca range, stresses rise from 0 Pa to 12 Pa for NBD-PG and from 3 Pa to 38 Pa for NBD-PC. To facilitate comparisons between the two surfactants, we non-dimensionalize the maximum Marangoni stresses using:

where γclean is the surface tensions of a clean interface (γclean = 68.77 mN.m−1), without surfactant. At equal concentration, this scale depends on the surfactant type but not on drainage, providing a rough estimate of the maximum surface tension gradient possible in our system.

Non-dimensionalized results, shown in Fig. 3d, indicate no significant difference in the evolution of Marangoni stresses between the two surfactants. This is observed despite variations in disjoining pressure and TLF thickness, which are approximately 10 nm for NBD-PC and range from 56 to 71 nm for NBD-PG, as detailed in as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. In this section, we propose an analytical relation to explain these experimental trends.

In the classical lubrication limit the pressure should be uniform and the flow field should be stationary. However the experiments reveal very strong local symmetry breaking disturbance flows, as seen e.g. in Supplementary Movies 1 and 2. The surfactant redistribution, driven by Marangoni stresses, generates interfacial shear stresses that in turn drive a local disturbance surface velocity us. We propose a scaling argument for us so we can evaluate the Marangoni stress scale:

Here, η is the viscosity of the bulk liquid in the film, and PH is the hydrodynamic pressure5. The disjoining pressure during drainage under an applied pressure ΔP is given by Πdisj(ΔP) = Πdisj(h(ΔP), Γ(ΔP)). While RTFB, η, and PH are well defined, the relevant length scale H/2, representing the effective thickness over which interfacial flows dominate and shear stresses dissipate is less clear. From visualizations of strong asymmetric surfactant-driven flows in Fig. 4, Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 2 which show strong Marangoni flows, we observe no clear difference in the magnitude or nature of interfacial flows between films of constant thickness (e.g., CBF with NBD-PC) and those of varying thickness (e.g., NBD-PG). This apparent independence from the overall film thickness suggests that the velocity scale should be based on a characteristic interfacial layer thickness. As we still observe these velocities in the Common Black Film regime56,57, we propose this characteristic thickness as a suitable length scale i.e., H = hCBF − hBL, where hCBF is the CBF thickness measured from Fig. 2 (hCBF = 10 nm for NBD-PC and hCBF = 16 nm for NBD-PG) and hBL = 4.21 nm is the dehydrated lipid bi-layer thickness. These parameters are defined in Fig. 3b for the specific case of the CBF (i.e., NBD-PC). Given the weak dependence of the interfacial flow on the total film thickness we postulate that the interfacial flow is primarily correlated with this hydrated layer movement beneath the interface. The scaling in Eq. (7) is therefore consistent with observed thin-film dynamics: higher pressure increases interfacial velocity, whereas higher viscosity or larger spatial extension reduces mobility.

a–c For an NBD-PG stabilized film under an applied pressure of ΔP = 1000 Pa. a In-plane thickness maps at two different times (gray color scale). b In-plane disjoining pressure (gray color scale) and Marangoni stress maps at the same two times, with arrows indicating the orientation of Marangoni stresses; arrow lengths are proportional to stress magnitude, as indicated by the blue-to-purple color scale. c Profile view showing the thickness (blue), the interface surfactant concentration (purple), the disjoining pressure (green), and the absolute Marangoni stresses (red), corresponding to the blue line profiles marked in (a). All three scale bars are consistent across the time points shown in (a, b), the continuous line and dash line are respectively for data at t = 334 s and t=734 s. d Maps of the Marangoni stresses and disjoining pressure during drainage at ΔP = 1000 Pa at three different times for film stabilized by NBD-PC. Color scales and arrows are defined as in (b). Red arrows indicate the direction of surfactant recirculation flows within the film.

At the interface (z = 0), the steady 1-D species balance reads

where Ds is the interfacial diffusion coefficient. Substituting the expression for us, Eq. (7), into Eq. (9) provides the working relation between the measured surfactant gradient and the local hydrodynamic pressure, yielding:

Assuming that the interfacial tension γ can be rewritten, in our concentration range, as a linear function of the interfacial concentration Γ as described in Supplementary Note 5:

It follows that:

With σMax-Ma = dγ/dr the maximum Marangoni stresses amplitude. This leads to the expression:

The left-hand term of Eq. (13) is obtained directly from the time-averaged concentration gradients measured during the drainage, the procedure is detailed in Supplementary Note 7. Experimental values for this term are represented in Fig. 3d. Ca is imposed by the experimental conditions (ΔP). The average local disjoining pressure at the location of maximum Marangoni stresses (Πdisj) is estimated for each pressure investigated, based on the local surfactant concentration (Γ) and Eq. (3). The disjoining pressure can contribute a constant hysteresis, particularly in the case of black film formation58. Therefore, we rescale the Marangoni stresses relative to the measurement at ΔP = 50 Pa. Thus, in Eq. (13), the terms on the left side (Fig. 3e, f, red data) depend on the measured spatial gradient of surfactant concentration, while the terms on the right side (Fig. 3e, f, green data) depend on the net local surfactant concentration. All numerical parameters used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Results of the Eq. (13), using the proposed scaling relation, are shown in Fig. 3e for the NBD-PC and Fig. 3f for the NBD-PG. Eq. (13) seems to capture the experimental data in both cases within the error-bar uncertainty. The magnitude of the error bars on the right-hand side of Eq. (13) representation (green data), primarily arises from uncertainties in the disjoining pressure measurements. We also note that the relation appears to become less accurate as the Capillary number increases, particularly for the NBD-PG system. Since this discrepancy pertains more to the trend than to the order of magnitude, it may arise from non-linear terms in Eq. (3) -such as errors in estimating the disjoining pressure or the presence of local curvature in the film, which can lead to an additional thin-film Laplace pressure. This effect is especially relevant for NBD-PG, where the film is not completely flat, see Fig. 4a. Eq. (13) provides insight into how tangential Marangoni stresses and normal disjoining pressure are consistently coupled.

Understanding the synergies between Marangoni stresses and disjoining pressure variations

The previous section introduced tools to measure the in-plane concentration in surfactant and, from it, derive the local Marangoni stresses and disjoining pressure. In this section, we will focus more on the influence of tangential Marangoni stresses on the thin film stability in time and clearly show its synergy with normal disjoining pressure.

Normal and Tangential stress (Re)-distribution

To investigate the interplay between different forces, we analyze time-resolved thickness and concentration maps during the drainage, where fluorescence interference decoupling is feasible (first order only). This limitation is not a major issue, as only in the final stages of film thinning the disjoining pressure starts to play a significant role. The deconvolution of thickness and concentration profiles allows us to calculate and visualize the spatial distributions of both Marangoni stresses and disjoining pressures.

In Fig. 4a–d, we present time evolution results for a draining film under ΔP = 1000 Pa, respectively stabilized by NBD-PG and NBD-PC. Figure 4a shows the time-resolved evolution of thickness. In Fig. 4b, using the disjoining pressure model (Eq. (3)) and the procedure introduced earlier for calculating local Marangoni stresses, we derive the directional vectorial Marangoni stresses (colored vector field) and scalar disjoining pressure stresses (gray scale). The corresponding analysis for NBD-PC is shown in Fig. 4d. In-plane surfactant flows are observed in films stabilized by NBD-PG and, unexpectedly, in NBD-PC flat CBF despite the low thickness scale. Red arrows in Fig. 4a, d qualitatively indicate these flow directions. For NBD-PG, the flow pattern forms two recirculating regions separated by a central channel. A similar pattern emerges in the final stage of drainage for NBD-PC, after complex gradient-driven flows and interactions dissipate as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Selected cross-sections of the film, indicated as blue lines in Fig. 4a, are analyzed in Fig. 4c. The lower part of Fig. 4c displays the corresponding thickness (blue) and interfacial surfactant concentration (purple), while the upper part shows the disjoining pressure (green) and Marangoni stress magnitudes (red). The lower-magnitude spatial fluctuations in Marangoni stresses observed in Fig. 4c are attributed to residuals that persist after denoising the images (Fig. 4c, purple solid lines), rather than to a meaningful physical signal. This issue is further discussed in Supplementary Note 7, and the corresponding noise estimate has been taken into account for average values in the Fig. 3 analysis.

From Fig. 4a, c, we observe an increase in thickness in the two recirculating regions of the film, adjacent to the surfactant-rich central channel (Fig. 4c blue lines). Figure 4b confirms that Marangoni stresses, as expected, are directed from surfactant-rich to surfactant-poor areas. This interfacial flow, coupled with bulk flow, pushes liquid from the central channel into the side regions, leading to localized thickening.

As shown in Fig. 2b, this thickness increase ( ~55 nm in NBD-PG stabilized films) corresponds to a reduction in disjoining pressure, also observed in Fig. 4c. Additionally, the overall surfactant depletion due to drainage contributes to this effect. Thus, for relatively thick films, Fig. 4c highlights a stabilization mechanism: Marangoni stresses sustain macroscopic flow within the film and facilitate liquid transfer from the Plateau Border to the thinnest, weakest regions. This in-plane fluid redistribution cannot be explained solely by normal disjoining pressure; instead, maintaining local concentration gradients enhances film stability.

In contrast, for NBD-PC stabilized films (Fig. 4d), where disjoining pressure is much lower, the film remains at a nearly constant thickness (CBF), and no thickness increase is observed. Here, disjoining pressure variations are solely driven by surfactant concentration. The directional nature of Marangoni flow explains the macroscopic reorganization of instabilities-from two curved, surfactant-rich regions to a single straight, concentrated line. Again, Marangoni stresses temporarily stabilize the film by redistributing surfactant from high to low concentration areas, increasing disjoining pressure, and slowing down thinning.

However, as surfactant depletion continues due to hydrodynamic drainage into the Plateau Border, the disjoining pressure eventually becomes negative, leading to final film collapse. This delay in rupture, influenced by high recirculation (PeS) and Marangoni stresses (Ma), is also observed in Fig. 5. In both high and low disjoining pressure cases, the interplay between tangential Marangoni stresses and normal disjoining pressure highlights the combined role of surfactant concentration and spatial flow redistribution in film stability.

Green points are related to data presented in Fig. 3, while red points are additional measurements at drainage pressure of 625 Pa and 875 Pa to confirm observed trends as described further in Supplementary Note 8. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval, calculated using Student’s t-distribution and appropriate error propagation for combined data sets.

Film lifetime: Marangoni stabilizing effect

The interplay between Marangoni stress and disjoining pressure will be revealed most easily by looking at the evolution of the film rupture time with the applied pressure. The present section focuses on NBD-PC, as no film rupture was observed for NBD-PG due to its higher stabilization from disjoining pressure.

Since the film rupture time (tr) may depend on the film’s thinning rate characterized by the drainage time td, we use the non-dimensionalized film rupture time, τr:

This approach normalizes the effects of drainage on the overall film lifetime, allowing us to isolate and assess the true impact of local physical phenomena-specifically, the interplay between Marangoni stresses developing in thinner regions and the increase in disjoining pressure- on delaying rupture.

Furthermore we introduce the Marangoni number as:

The surface Péclet number as:

The product of Marangoni number and surface Péclet number (Ma ⋅ PeS) governs the importance of concentration gradients.

The non-dimensional film rupture time plotted against the product Ma ⋅ PeS is shown in Fig. 5. We can see two regimes: A first regime at low Ma ⋅ PeS, and low Ca, where the film rupture time is independent of the Ma ⋅ PeS. This regime can be put in parallel with the mechanisms proposed by Vrij and Scheludko, as shown by Chatzigiannakis and Vermant59 on polymer stabilized TLFs, and associated with a stochastic rupture regime, where fluctuation drives the rupture. For Ma ⋅ PeS > 5, the film rupture time increases significantly-by up to a factor of four-indicating that Marangoni stresses indeed stabilize the film and help prevent rupture. These findings are in agreement with the experimental observations of Hudson et al.37 of the constant coalescence efficiency at low Ma ⋅ PeS and the decreasing coalescence efficiency at higher Ma ⋅ PeS. This dependency appears nonlinear, with a sharp transition between the two regimes. A detailed analysis of trend explanations is beyond the scope of this article. Notably, in our experiments, the transition between these two regimes occurs around Ma ⋅ PeS = 5, which is close to the value of Ma ⋅ PeS = 10 reported by Hudson et al.37. This confirms that in the high Ma ⋅ PeS regime, tangential Marangoni stresses take over the stabilizing process of the normal disjoining pressure that predominate at low Ma ⋅ PeS.

Conclusions

Using a dynamic thin film balance apparatus with films containing fluorescent surfactants, we investigated the influence of tangential solutal Marangoni stresses and normal disjoining pressure on the stability of surfactant-stabilized air/liquid thin films. Combining bright field and fluorescence microscopy with an analytic method to decouple fluorescent interference, we accessed the spatial distribution of surfactants at the interface of a draining thin liquid film. By considering the variation of interfacial concentration during drainage experiments, we proposed a simple model for the disjoining pressure during thin film drainage. This model is general and valid for interfaces with low apparent charge (zwitterionic lipids) to higher charge (net-charged lipids) contributions to disjoining pressure.

Beside our experimental measurement of Marangoni stresses, we proposed a scaling relation for the magnitude of a local surface velocity to rationalize the coupling between tangential Marangoni stresses and normal disjoining pressure stresses. These observations show that the magnitude of tangential Marangoni stresses increases with normal disjoining pressure, and remain valid across the studied range of disjoining pressures. As symmetry breaking and instabilities tend to develop over large areas, this coupling provides a plausible explanation for these phenomena during thin liquid film drainage.

We show that both thicker films made of charged surfactants as well as so called Common Black Films made of zwiterionic surfactants, are surprisingly far from being static and uniform. They exhibit significant asymmetry in surfactant coverage, complex interfacial species flows, and flow instabilities in the form of convective patterns. Thus, Marangoni stresses have both local and macroscopic effects.

We showed that the lifetime of thin liquid films is independent of Marangoni stresses at low Marangoni-Peclet (Ma ⋅ PeS) numbers, but increases with Marangoni stresses at higher Ma ⋅ PeS, with the transition occurring around Ma ⋅ PeS ≈ 5. Thus, high Marangoni stresses enhance the temporal stability of thin liquid films.

Future studies could extend this work to different surfactants, more rheologically complex interfaces, and vary bulk properties such as viscosity. Moreover, the exact nature of in-plane convective flow in thin films with high interfacial mobility should be a topic for further theoretical work. It will also be interesting to see the effects of the interplay discussed here on capillary waves and fluctuations in the stages leading to film rupture. Additionally, the findings regarding black film stabilization could be valuable for understanding the stability of high aspect ratio bilayers, particularly in biological systems.

Methods

Materials

The thin film bulk phase was prepared using a 2:1 volumetric ratio mixture of milliQ water and glycerol. The mixture phase was filtered with a hydrophilic filter (TPP 0.22 μ L PES). Lipids tagged on their hydrophobic tails with NBD (Nitrobenzofurazan) where purchased as powders from Avanti Polar: zwiterionic lipids NBD-PC (1-Oleoyl-2-[12-[(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]dodecanoyl]-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine) and negatively charged NBD-PG (1-oleoyl-2-12-[(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)amino]dodecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac(1-glycerol)] (ammonium salt)). Both lipids where used as received and suspended in ethanol (pro analysis, Supelco) up to a concentration of 0.1 mg.mL−1. The lipid suspensions were stored at −20 °C and used within one week of preparation to ensure sample integrity.

Thin-film balance experiments

The Dynamic Thin Film Balance (DTFB) apparatus used has been described in Chatzigiannakis et al.5. It comprises an upright fixed-stage Nikon Eclipse FN1 microscope, an Elveflow MK3+ piezoelectric pressure control system which has a resolution of 1 Pa and a maximum pressure of 20 kPa, an in-house fabricated aluminium pressure chamber containing a customized bike-wheel microfluidic device. The bike-wheel chip is a microfluidic device based on an initial design of Cascão-Pereira et al.60, optimized to ensure homogeneous drainage from the film. The bike-wheel chip is custom manufactured by Micronit Microfluidics with a modified architecture compared to the one reported in Chatzigiannakis et al.5, two reservoirs were added around the thin film balance hole to facilitate surfactant spreading, and the holes were added using laser ablation to ensure better defined edges compared to earlier work. The hole dimensions remain RTFB = 0.5 mm in radius, with a half-thickness of HTFB = 200 μ m, and it includes 25 isotropically distributed channels, each with a width of 45 μ m and a depth of 20 μ m. To ensure that the contact line between the liquid and the glass is pinned, the bike-wheel’s outer surface is hydrophilised by immersing it in a saturated NaOH ethanol solution and leaving it under sonication for 20 min.

A quad-band filter from Chroma and a LED Lumencore SpectraX light source allows simultaneous imaging at λBF = 510 nm for Bright Field (BF) reflection and λexc = 470 nm for fluorescence excitation with an emission centered around 525 nm. Data are recorded with a Hamamatsu ORCA-Flash4.0 CMOS camera with respectively 10 ms and 80 ms exposure time for the Bright field and fluorescence image. The BF interference image allows tracking the film thickness h, via the Scheludko equation4:

With \(Q={(({n}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}-{n}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}})/({n}_{{{{\rm{f}}}}}+{n}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}))}^{2}\), na and nf being the refractive index of the air and liquid phase, Δ = (IBF − IBF-Min)/(IBF-Max + IBF-Min) with IBF, IBF-Min and IBF-Max the BF and the minimum and maximum BF intensity. m is the order of interference.

To begin the experiment, the outer surface of the chip is washed with ethanol and rinsed with the water-glycerol mixture, a process repeated twice. The chip is then filled with the mixture. The surfactant solution is sonicated in an ice-cooled water bath for at least 15 minutes, and 2.5 μ L is applied to each side. Care is taken to avoid excess liquid outside of the reservoirs to ensure reproducibility of the initial concentration in surfactants. The chip is secured in the chamber, which is partially filled with water before sealing to prevent evaporation in the thin film. In both experiments, the equilibrium pressure is determined when interference fringes first occur, without film expansion or thickening, indicating mechanical balance of the film wetting the holder. This method follows Chatzigiannakis et al.5. All experiments are performed at room temperature:

-

Disjoining pressure experiments: A logarithmic pressure profile is applied, with pressure steps increasing from 1.5 Pa to 140 Pa, up to the point of film rupture. At each step, the equilibrium between disjoining, Laplace, and applied pressures is ensured by waiting for the film thickness to stabilize. For disjoining pressure determination, at least three measurements are performed with an adaptive image acquisition rate of one image every 1 s, 5 s, or 10 s.

-

Drainage experiments: From the equilibrium state, we apply a single pressure step ΔP of either 50 Pa, 150 Pa, 250 Pa, 500 Pa, 750 Pa or 1000 Pa. Images are acquired at a frequency of one every 240 ms. At least eight experiments are conducted per data point, and films are observed for up to 30 minutes if they remain intact.

Additional measurements for NBD-PC drainage experiments at 625 Pa and 875 Pa were conducted to refine the film lifetime transition from low to high Ma ⋅ PeS (Fig. 5), and confirm the trend of higher lifetime at high Ma ⋅ PeS. Their Ma ⋅ PeS value and characteristic drainage time scale τc were estimated as detailed in the Supplementary Note 8.

Concentration and surface tension

Interfacial tension measurements of lipids at the air/water-glycerol interface are performed using a platinum Wilhelmy plate (19.62 mm width, 0.1 mm thickness) mounted on a KSV Nima balance. The spreading area is 33.1 mm × 19.7 mm, with the plate oriented along the long axis. The volume of the bulk phase and the interfacial area are kept constant throughout the experiment. To prevent contamination, all tools are cleaned three times with MilliQ water and ethanol, and the Wilhelmy plate is flame-burned before use. The bulk phase volume and interfacial area are kept constant. The same surfactant solution used in DTFB experiments is applied drop-wise at the interface using a 5 μ L Hamilton syringe until the target surface concentration is reached. In this study, we consider the equilibrium surface tension values corresponding to the plateau region of the surface tension curve, observed after complete solvent evaporation and surfactant equilibration at the interface. At least three measurements were conducted for each concentrations for both surfactants. Fluorescence intensity measurements are performed on a same area and volume than the surface tension measurements using the identical acquisition and exposure times than for the drainage experiments. For calibration, both surfactants are tested at concentrations of 0.26, 0.52, 0.78, 1.04, 1.56 molecules.nm−2, with data fitted to a linear function of interface concentration. Lipid interfaces are assumed to be liquid-like, with negligible interfacial rheology compared to the surface tension component of the stress tensor. Details on the surface tension calibration are provided in Supplementary Note 5, with the raw data shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 and the fitted data in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed in Matlab. Due to the low intensity of the fluorescence signal, the data present some noise. To mitigate this, we applied the Matlab smoothdata2 function with a Gaussian filter and a window size of 25 pixels. The maximum gradient in the film is extracted from the maximum norm of the 2D gradient function of Matlab. The residual noise in the maximum fluorescence gradient data is subtracted from the measured maximum gradient. This noise level is estimated as the mean value of the initial maximum fluorescence gradient at ΔP = 50 Pa, when the fluorescence profiles are nearly flat and the gradient has not yet developed. The effectiveness of this denoising method is detailed in Supplementary Note 7 and illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10. Local intensity and gradient data are extracted at regular interval of 9.7 seconds to avoid too numerically heavy analysis. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Fig. 11. The film rupture time, tr, is defined as tr = tL − td, where tL is the film lifetime and td is the film drainage time. The film lifetime extracted from the NBD-PC drainage data is the time elapsed from the formation of the TLFs till its rupture, while the drainage time refers to the duration from the formation of the TLFs until the appearance of the CBF. Notably, since experiments were limited to a maximum duration of 30 minutes due to data storage constraints, films that did not rupture within this time-frame were assigned the maximum lifetime of 30 minutes as detailed in Supplementary Note 8 and Supplementary Table 2. Rupture time data are presented in Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13. All error bars represent the 95% confidence interval based on Student’s t-distribution, and errors for combined data sets are calculated using standard error propagation methods.

Data availability

All of the analyzed experimental data are provided in the Supplementary Information and available at https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000723851. The initial raw unprocessed data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code is available at https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000723851.

References

Janssen, F., Wouters, A. G. B., Chatzigiannakis, E., Delcour, J. A. & Vermant, J. Thin film drainage dynamics of wheat and rye dough liquors and oat batter liquor. Food Hydrocoll. 116, 106624 (2021).

Park, S. et al. Solutal Marangoni effect determines bubble dynamics during electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nat. Chem. 15, 1532–1540 (2023).

Hermans, E., Saad Bhamla, M., Kao, P., Fuller, G. G. & Vermant, J. Lung surfactants and different contributions to thin film stability. Soft Matter 11, 8048–8057 (2015).

Sheludko, A. Thin liquid films. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1, 391–464 (1967).

Chatzigiannakis, E., Veenstra, P., ten Bosch, D. & Vermant, J. Mimicking coalescence using a pressure-controlled dynamic thin film balance. Soft Matter 16, 9410–9422 (2020).

Mikhailovskaya, A., Chatzigiannakis, E., Renggli, D., Vermant, J. & Monteux, C. From individual liquid films to macroscopic foam dynamics: A comparison between polymers and a nonionic surfactant. Langmuir 38, 10768–10780 (2022).

Chatzigiannakis, E., Chen, Y., Bachnak, R., Dutcher, C. S. & Vermant, J. Studying coalescence at different lengthscales: from films to droplets. Rheol. Acta 61, 745–759 (2022).

Guidolin, C., Mac Intyre, J., Rio, E., Puisto, A. & Salonen, A. Viscoelastic coarsening of quasi-2D foam. Nat. Commun. 14, 1125 (2023).

Bird, J. C., de Ruiter, R., Courbin, L. & Stone, H. A. Daughter bubble cascades produced by folding of ruptured thin films. Nature 465, 759–762 (2010).

Ivanov, I. B. Effect of surface mobility on the dynamic behavior of thin liquid films. Pure Appl. Chem. 52, 1241–1262 (1980).

Ozan, S. C. & Jakobsen, H. A. On the role of the surface rheology in film drainage between fluid particles. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 120, 103103 (2019).

Chatzigiannakis, E., Jaensson, N. & Vermant, J. Thin liquid films: Where hydrodynamics, capillarity, surface stresses and intermolecular forces meet. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 53, 101441 (2021).

Bartlett, C., Oratis, A. T., Santin, M. & Bird, J. C. Universal non-monotonic drainage in large bare viscous bubbles. Nat. Commun. 14, 877 (2023).

Claesson, P. M., Ederth, T., Bergeron, V. & Rutland, M. W. Techniques for measuring surface forces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 67, 119–183 (1996).

Teletzke, G. F., Davis, H. T. & Scriven, L. E. Wetting hydrodynamics. Rev. Phys. Appl. 23, 989–1007 (1988).

Derjaguin, B. V. & Churaev, N. V. The current state of the theory of long-range surface forces. Colloids Surf. 41, 223–237 (1989).

Casimir, H. B. G. & Polder, D. Influence of retardation on the London–van der Waals forces. Nature 158, 787–788 (1946).

Lifshitz, E. M. The theory of molecular attractive forces between solids. Sov. Phys. JETP 2, 73–83 (1956).

Dai, B., Leal, L. G. & Redondo, A. Disjoining pressure for nonuniform thin films. Phys. Rev. E 78, 061602 (2008).

Derjaguin, B. & Landau, L. Theory of the stability of strongly charged lyophobic sols and of the adhesion of strongly charged particles in solutions of electrolytes. Prog. Surf. Sci. 43, 30–59 (1993).

Karakashev, S. I. & Ivanova, D. S. Thin liquid film drainage: Ionic vs. non-ionic surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 343, 584–593 (2010).

Chatzigiannakis, E. & Vermant, J. Dynamic stabilisation during the drainage of thin film polymer solutions. Soft Matter 17, 4790–4803 (2021).

Karakashev, S. I. et al. Comparative validation of the analytical models for the Marangoni effect on foam film drainage. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 365, 122–136 (2010).

Yang, S., Kumar, S. & Dutcher, C. S. Instability and rupture of surfactant-laden bilayer thin liquid films. Soft Matter 19, 5737–5748 (2023).

Narayan, S., Metaxas, A. E., Bachnak, R., Neumiller, T. & Dutcher, C. S. Zooming in on the role of surfactants in droplet coalescence at the macroscale and microscale. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 50, 101385 (2020).

Chatzigiannakis, E. & Vermant, J. Perspective: Interfacial stresses in thin film drainage: Subtle yet significantant. J. Rheol. 68, 655–663 (2024).

Janssen, P. J. A. & Anderson, P. D. Modeling film drainage and coalescence of drops in a viscous fluid. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 296, 238–248 (2011).

Yeo, L. Y., Matar, O. K., de Ortiz, E. S. P. & Hewitt, G. F. The dynamics of Marangoni-driven local film drainage between two drops. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 241, 233–247 (2001).

Shen, L., Denner, F., Morgan, N., van Wachem, B. & Dini, D. Transient structures in rupturing thin films: Marangoni-induced symmetry-breaking pattern formation in viscous fluids. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0597 (2020).

Chesters, A. K. & Bazhlekov, I. B. Effect of insoluble surfactants on drainage and rupture of a film between drops interacting under a constant force. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 230, 229–243 (2000).

Liu, B. et al. Coalescence of bubbles with mobile interfaces in water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 194501 (2019).

Tsekov, R. et al. Streaming potential effect on the drainage of thin liquid films stabilized by ionic surfactants. Langmuir 26, 4703–4708 (2010).

Dai, B. & Leal, L. G. The mechanism of surfactant effects on drop coalescence. Phys. Fluids 20, 040802 (2008).

Bhamla, M. S., Chai, C., Àlvarez-Valenzuela, M. A., Tajuelo, J. & Fuller, G. G. Interfacial mechanisms for stability of surfactant-laden films. PLoS ONE 12, e0175753 (2017).

Karakashev, S. I. & Tsekov, R. Electro-marangoni effect in thin liquid films. Langmuir 27, 2265–2270 (2011).

Rodríguez-Hakim, M., Barakat, J. M., Shi, X., Shaqfeh, E. S. G. & Fuller, G. G. Evaporation-driven solutocapillary flow of thin liquid films over curved substrates. Phys. Rev. Fluids 4, 034002 (2019).

Hudson, S. D., Jamieson, A. M. & Burkhart, B. E. The effect of surfactant on the efficiency of shear-induced drop coalescence. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 265, 409–421 (2003).

Gingell, D. & Todd, I. Interference reflection microscopy. a quantitative theory for image interpretation and its application to cell-substratum separation measurement. Biophys. J. 26, 507–526 (1979).

Wiegand, G., Neumaier, K. R. & Sackmann, E. Microinterferometry: three-dimensional reconstruction of surface microtopography for thin-film and wetting studies by reflection interference contrast microscopy (ricm). Appl. Opt. 37, 6892–6905 (1998).

Parthasarathy, R. & Groves, J. T. Optical techniques for imaging membrane topography. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 41, 391–414 (2004).

Schilling, J., Sengupta, K., Goennenwein, S., Bausch, A. R. & Sackmann, E. Absolute interfacial distance measurements by dual-wavelength reflection interference contrast microscopy. Phys. Rev. E 69, 021901 (2004).

Limozin, L. & Sengupta, K. Quantitative reflection interference contrast microscopy (ricm) in soft matter and cell adhesion. ChemPhysChem 10, 2752–2768 (2009).

Lambacher, A. & Fromherz, P. Fluorescence interference-contrast microscopy on oxidized silicon using a monomolecular dye layer. Appl. Phys. A 63, 207–216 (1996).

Lambacher, A. & Fromherz, P. Luminescence of dye molecules on oxidized silicon and fluorescence interference contrast microscopy of biomembranes. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 19, 1435–1453 (2002).

Crane, J. M., Kiessling, V. & Tamm, L. K. Measuring lipid asymmetry in planar supported bilayers by fluorescence interference contrast microscopy. Langmuir 21, 1377–1388 (2005).

Israelachvili, J. N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces (Academic Press, 2011), 3 edn.

Pinisetty, D., Moldovan, D. & Devireddy, R. The effect of methanol on lipid bilayers: An atomistic investigation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 34, 1442–1451 (2006).

Todorov, R. Thin liquid films in biomedical studies. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 20, 130–138 (2015).

Kolarov, T., Cohen, R. & Exerowa, D. Direct measurement of disjoining pressure in black foam films II. Films from nonionic surfactants. Colloids Surf. 42, 49–57 (1989).

Stubenrauch, C. & von Klitzing, R. Disjoining pressure in thin liquid foam and emulsion films-new concepts and perspectives. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 15, R1197–R1232 (2003).

Ruckenstein, E. & Manciu, M. On the stability of the common and Newton black films. Langmuir 18, 2727–2736 (2002).

Stojimirovifa, B., Vis, M., Tuinier, R., Philipse, A. P. & Trefalt, G. Experimental evidence for algebraic double-layer forces. Langmuir 36, 47–54 (2020).

Philipse, A. P., Kuipers, B. W. M. & Vrij, A. Algebraic repulsions between charged planes with strongly overlapping electrical double layers. Langmuir 29, 2859–2870 (2013).

Klausen, L. H., Fuhs, T. & Dong, M. Mapping surface charge density of lipid bilayers by quantitative surface conductivity microscopy. Nat. Commun. 7, 12447 (2016).

Dreier, L. B. et al. Unraveling the origin of the apparent charge of zwitterionic lipid layers. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 6355–6359 (2019).

Mysels, K. J. Soap films and some problems in surface and colloid chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. 68, 3441–3448 (1964).

Exerowa, D. & Kruglyakov, P. M. Foam and Foam Films: Theory, Experiment, Application, vol. 5 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1997), 1 edn.

Casteletto, V. et al. Stability of soap films: Hysteresis and nucleation of black films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 048302 (2003).

Chatzigiannakis, E. & Vermant, J. Breakup of thin liquid films: From stochastic to deterministic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 158001 (2020).

Cascão Pereira, L. G., Johansson, C., Blanch, H. W. & Radke, C. J. A bike-wheel microcell for measurement of thin-film forces. Colloids Surf. A 186, 103–111 (2001).

Acknowledgements

J.V. and L.B. gratefully acknowledge financial support from Shell Global Solutions International and thank Dr. Peter Veenstra for stimulating discussions. We also appreciate Prof. Manolis Chatzigiannakis (TU Eindhoven) and Maria Clara Novaes (ETH Zurich) for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B. was involved in the conceptualization, performed experiments, wrote the initial draft and J.V. supervised, acquired funding, was involved in the conceptualization and writing, editing, and review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Steven Hudson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bidoire, L., Vermant, J. Mapping out the interplay between surfactant induced forces in thin liquid films. Commun Phys 8, 455 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02410-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02410-9