Abstract

The recent discovery of superconductivity with a transition temperature Tc exceeding 40 K in La3Ni2O7 and (La, Pr)3Ni2O7 thin films at ambient pressure marks a significant breakthrough in the field of nickelate superconductors. Using density functional theory (DFT), we propose a double-stacked two-orbital effective model for La3Ni2O7 thin film based on the Ni − eg orbitals. Our analysis of the Fermi surface reveals three electron pockets (\(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{{\prime} },\beta\)) and two hole pockets (\(\gamma ,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }\)), where the additional \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) pockets arise from inter-stack interactions. Furthermore, we introduce a high-energy model that incorporates O−p orbitals to facilitate future studies. Calculations of spin susceptibility within the random phase approximation (RPA) indicate that magnetic correlations are enhanced by nesting of the γ pocket, which is predominantly derived from the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital. Our results provide a theoretical foundation for understanding the electronic and magnetic properties of La3Ni2O7 thin films.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of superconductivity in the Ruddlesden-Popper (RP) bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7 at a transition temperature Tc near 80 K under high pressure (~14 Gpa) has generated significant interest in the field of unconventional superconductivity1. The subsequent observation of superconductivity in the trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10 under similar conditions further underscores the universality of superconductivity in nickelates2. These discoveries have motivated extensive theoretical3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 and experimental39,40,41,42,43,44,44,45,46 investigations into the microscopic mechanisms of unconventional superconductivity. However, the requirement of high pressure for superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 and La4Ni3O10 presents significant experimental challenges, which limit in-depth investigations. This has driven efforts to stabilize superconductivity under ambient pressure, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of its underlying mechanisms.

Recent studies have reported superconductivity with Tc exceeding 40 K in La3Ni2O747, (La, Pr)3Ni2O748,49 thin films at ambient pressure, marking a significant breakthrough in nickelate superconductors. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) reveals that the Ni ions in La3Ni2O7 thin film retain a mixed valence state similar to that of the bulk form47. Furthermore, scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) confirms that their microscopic structure closely resembles that of the bulk phase of high pressure, adopting a tetragonal crystal structure48. In particular, the Tc in the thin film is tunable via the in-plane lattice constant but remains relatively insensitive to the out-of-plane parameter. DFT calculation and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) measurement50,51 suggest that Ni-\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals contribute states near the Fermi level, highlighting the similarity between the thin film and the bulk system in terms of electronic structure and superconducting properties. Despite these advances, most theoretical studies have relied on simplified half-unit-cell (Half-UC) slab model52,53, which may not fully capture the effects of dimensionality on the electronic structure. A more comprehensive approach incorporating the full-unit-cell slab model is therefore needed to provide a more accurate description of this system.

In this paper, we employ slab models of La3Ni2O7 thin films to investigate their electronic structures in various thicknesses, including three-unit-cell (Three-UC), one-unit-cell (One-UC), and Half-UC configurations. Except for the Half-UC case, each slab model retains a complete unit cell (UC), with the two bilayers denoted as Stack 1 and Stack 2, enabling a systematic exploration of the relationship between dimensionality and electronic properties. Using first-principles calculations, we propose a double-stacked two-orbital effective model for the One-UC slab structure, based on Ni −eg orbitals. Our analysis reveals the presence of three electron pockets (\(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{{\prime} },\beta\)) and two hole pockets (\(\gamma ,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }\)) on the Fermi surface, where inter-stack interactions give rise to the additional \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) pockets. Furthermore, we extend our model by incorporating O−p orbitals into a high-energy framework to facilitate future studies. Spin susceptibility calculations within the RPA indicate pronounced magnetic correlations, primarily driven by nesting effects of the γ pocket, which is predominantly derived from the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital. Our results provide a theoretical framework for understanding the interplay among the dimensionality, magnetism, and superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 thin films, offering key insights for future theoretical and experimental investigations.

Results

Slab structures

We begin our investigation of the La3Ni2O7 thin films by modeling the slab structures using DFT calculations. Bulk La3Ni2O7 belongs to the n = 2 Ruddlesden-Popper phase, characterized by a UC comprising two corner-sharing NiO6 octahedra bilayers stacking along the c axis1. In its thin-film form, La3Ni2O7 adopts a tetragonal structure similar to the high-pressure bulk phase, distinguished by an apical Ni-O-Ni bond angle approaching 180∘47,54. To systematically explore the structural and electronic properties of La3Ni2O7 thin films, we consider slab structures of varying thicknesses along the out-of-plane direction, including Three-UC, One-UC, and Half-UC slabs. To minimize interactions between periodic images, a vacuum spacing exceeding 16 Å is introduced along the c axis.

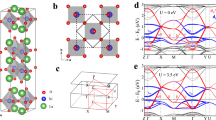

The One-UC slab consists of two stacked NiO6 octahedra bilayers, which can adopt two distinct stacking configurations, Stack 1 and Stack 2, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). In all slab models, we consider a free-standing geometry with a vacuum layer to eliminate inter-slab interactions. The effect of epitaxial strain from the substrate is incorporated by fixing the in-plane lattice constant to the experimentally measured value of a = 3.77Å47. Although this approach does not capture all aspects of the experimental system—particularly in thicker films, where subtle differences between the top and bottom layers may occur—it provides a reasonable and reliable approximation for the few-layer systems considered in this study. The Ni-O bond lengths, labeled as d1, d2, d3, d4, and d5 in Fig. 1(a), are summarized in Table 1 for different slab structures and effective Hubbard parameters (Ueff = 0 eV and Ueff = 2 eV). For clarity, only the bond distances of the middle UC are reported for the Three-UC slab structure.

a The free-standing One-UC slab structure of La3Ni2O7, where the two bilayers are labeled as Stack 1 and Stack 2. Green, gray, and red spheres denote La, Ni, and O atoms, respectively. The outer-apical (d1 and d4), inner-apical (d2 and d3), and in-plane (d5) Ni-O bond lengths are indicated by black, red, and blue arrows, respectively. b Schematic illustration of the hopping parameters in the La3Ni2O7 thin films, highlighting the Ni\(-{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) (orange) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) (blue) orbitals. Only nearest-neighbor hopping terms are shown.

For Ueff = 0 eV, the in-plane Ni-O bond (d5) is the shortest, while the outer-apical Ni-O bonds (d1 and d4) are the longest, consistent with the high-pressure phase of La3Ni2O7. Different slab structures yield nearly identical results in terms of bond lengths. In the Three-UC and One-UC slabs, d1 and d4 vary across stacking configurations, while d2 and d3 also exhibit stack-dependent variations, indicating symmetry breaking between different stacks. The Ni-O bond lengths in these slabs follow a specific symmetry relation: in Stack 1, d1, d2, d3, d4 correspond to d4, d3, d2, d1 in Stack 2. In contrast, the Half-UC slab exhibits a distinct structural behavior, characterized by Ni-O bond lengths that are symmetric about the central oxygen atom, differing from the asymmetric distortions observed in the other slab structures. This difference arises from the underlying structural symmetry. In Half-UC, the slab posesses mz symmetry, with the mirror plane located between the two NiO layers. This symmetry enforces bond length equivalence with respect to the mirror plane, resulting in two nonequivalent vertical bond lengths. However, the One-UC and Three-UC slabs exhibit a different symmetry operation, \(\{{m}_{z}| \frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2}\}\), where the mirror plane lies between two stacks. This symmetry allows for bond length variations within each individual stack, leading to distinct vertical bond lengths across the three stacks in the Three-UC slab, whereas only one stack exhibits such variations in the One-UC slab. This symmetry distinction is further reflected in the hopping parameters, influencing the electronic properties of the system.

For Ueff = 2 eV, electron correlation significantly influences the outer-apical Ni-O bond lengths (d1 and d4) in the Three-UC and One-UC slabs, whereas its effect is negligible in the Half-UC slab. Meanwhile, the in-plane Ni-O bond length (d5) remains relatively stable in all configurations. These structural modifications are expected to have a pronounced impact on the electronic structures, which will be examined in detail in the following subsection. These findings highlight the critical role of interlayer interactions in determining the structural properties, which cannot be adequately captured by the Half-UC slab.

Electronic structures

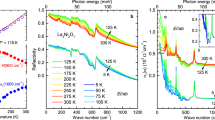

We now investigate the electronic structures of La3Ni2O7 thin films based on DFT calculations. For Ueff = 0 eV, the band structure and projected density of states (PDOS) of the One-UC slab exhibit a clear metallic character, as shown in Fig. 2a. The electronic states near the Fermi level (EF) are primarily composed of Ni\(-{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals, which are well separated from the lower-energy Ni-t2g orbitals. Moreover, these Ni−d orbitals exhibit hybridization with O−p orbitals within the energy range of −2 eV to 2 eV. Due to interlayer hybridization, the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) electronic states form bonding and antibonding bands, located below and above EF, respectively. Additionally, the La-derived states make minimal contributions to the electronic states at EF. The electronic structures of the Three-UC slab exhibit a similar behavior to that of the One-UC slab, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1(a). Notably, the reduced structural symmetry in thin films induces a splitting of Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands along the M − Γ direction, leading to the formation of distinct electronic pockets near the M point [See Fig. 3(a)]. In contrast, the Half-UC slab, which retains higher structural symmetry, does not exhibit such splitting in the Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands [see Fig. 2b].

a and b correspond to calculations with Ueff = 0 eV, and c and d correspond to Ueff = 2 eV. The contributions from the Ni\(-{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals are highlighted in blue and red, respectively, while Ni − t2g, O-p, and La states are represented in orange, green, and cyan, respectively. The Fermi level (EF) is set to 0 eV. Here, Ueff denotes the effective hubbard parameter, and UC represents unit cell.

For Ueff = 2 eV, the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands shift downward and approach EF. Consequently, the density of states of Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) attains a maximum at EF in the One-UC slab, as shown in Fig. 2c. A similar downward shift is observed in the electronic structure of the Three-UC slab, where the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands move closer to EF, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 1b. This behavior corresponds to the metallization of the lower σ bonds in the high-presure phase of bulk La3Ni2O7. These results indicate that the electronic structure of La3Ni2O7 thin films closely resembles that of the high-pressure phase of the bulk material, which may provide insight into the emergence of high-temperature superconductivity in thin films. In contrast, the EF in the Half-UC slab exhibits only a slight downward shift, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. Previous studies on bulk La3Ni2O7 have reported that DFT calculations with Ueff = 3.5 eV yield results that are in good agreement with experimental observations39. To further explore this, we also consider the case of Ueff = 3.5 eV. Under this condition, the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands in the Three-UC and One-UC slabs shift further downward, moving below EF, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 1c and 2a. However, in the Half-UC slab, EF still crosses the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b.

Figure 3 presents the evolution of the Fermi surface in La3Ni2O7 thin films under different slab configurations and Hubbard Ueff. Panels (a) and (c) correspond to Ueff = 0 eV, while panels (b) and (d) correspond to Ueff = 2 eV. For Ueff = 0 eV, the Fermi surface of the One-UC slab consists of three electron pockets (\(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{{\prime} },\beta\)) and two hole pockets (\(\gamma ,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }\)), as shown in Fig. 3a. Notably, the γ and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) pockets are primarily derived from the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital. The splitting of the Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) and Ni\(-{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) states along the M − Γ and X − Γ directions gives rise to the additional \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) pockets. This splitting originates from inter-stack interactions induced by the reduced structural symmetry in thin films. In contrast, there are two electron pockets (α, β) and one hole pocket (γ) on the Fermi surface in the Half-UC slab, as shown in Fig. 3(b).

For Ueff = 2 eV, as the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands in the One-UC slab shift downward and approach EF, there is a significant reduction in the spatial extent of the hole pockets γ and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) around the M point in the Brillouin zone, as shown in Fig. 3c. In contrast, the Fermi surface geometry in the Half-UC slab exhibits minimal changes, as depicted in Fig. 3d.

Two-orbital models

Based on the previous subsections, the thickness of the slab model significantly influences the Ni-O bond lengths, which in turn affect the electronic structure. Experimental samples typically have a thickness of One-UC–Three-UC, and calculations for the Three-UC slab are expected to more closely reflect the experimental conditions. However, due to the complexity of the Three-UC slab model, we have chosen to construct the tight-binding (TB) model using the One-UC slab, which captures the main features of the electronic band structure observed in the Three-UC slab. The Half-UC slab is also considered for comparison.

Building on the electronic structures obtained from our DFT calculations, we first focus on the double-stacked two-orbital model for the One-UC slab. This model incorporates the Ni\(-{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals within the framework of the maximally localized Wannier functions Hamiltonian. The total Hamiltonian is given by

Here \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\) denotes the TB Hamiltonian derived from the Wannier downfolding procedure, while \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{U}\) represents the Coulomb interaction term55.

The basis of the model is defined as \({\Psi }_{\sigma }={\left({d}_{1Ax\sigma },{d}_{1Az\sigma },{d}_{1Bx\sigma },{d}_{1Bz\sigma },{d}_{2Ax\sigma },{d}_{2Az\sigma },{d}_{2Bx\sigma },{d}_{2Bz\sigma }\right)}^{T}\), where the field operator dsσ annihilates an electron in the state s with spin σ. The indices are assigned as follows: 1/2 label the stacked layers, A/B correspond to the bilayer sublattices, and x/z denote the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals, respectively. The labeling convention is illustrated in Fig. 1(b).

The TB Hamiltonian H(k) takes the form

The matrix elements are defined as follows:

Here \({H}_{A/B}^{1/2,x/z}({{{\rm{k}}}})\) and \({H}_{AB}^{1/2,x/z}({{{\rm{k}}}})\) describe intralayer and interlayer hopping within the same orbitals (\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) or \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\)), respectively, while \({H}_{A/B}^{1/2,xz}({{{\rm{k}}}})\) and \({H}_{AB}^{1/2,xz}({{{\rm{k}}}})\) represent intralayer and interlayer hybridization between \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals. Additionally, \({H}_{AB}^{12,z}({{{\rm{k}}}})=4{t}_{AB}^{12,z}\cos ({k}_{x}/2)\cos ({k}_{y}/2)\) describes inter-stack hopping within the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital, with a corresponding hopping parameter \({t}_{AB}^{12,z}=-0.025\). Hopping parameters for the One-UC slab model of La3Ni2O7 thin film are summarized in Table 2.

For the single-stacked two-orbital model of the Half-UC slab, the system exhibits layer symmetry and the absence of inter-stack coupling, as characterized by the conditions H1(k) = H2(k), H12(k) = 0, and \({H}_{A}^{1}({{{\rm{k}}}})={H}_{B}^{1}({{{\rm{k}}}})\). These conditions indicate that the Hamiltonians of the individual layers are identical, there is no direct coupling between the stacks, and the interfacial hopping parameters are equivalent for both sublattices. The corresponding hopping parameters for the Half-UC slab model of La3Ni2O7 thin film are provided in Table 3.

Using the TB parameters listed in Tables 2 and 3, we present the resulting band structure and Fermi surface for both One-UC and Half-UC slabs. As shown in Fig. 4a, the model for the One-UC slab accurately reproduces the DFT band structure near the EF. Notably, we observe a splitting of the Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands along the M − Γ direction, which originates from inter-stack interaction, specifically \({t}_{AB}^{12,z}\). Regarding the Fermi surface, we identify three electron pockets \(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{{\prime} },\beta\) and two hole pockets \(\gamma ,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }\), as illustrated in Fig. 4c. The \(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{{\prime} },\beta -{{{\rm{pocket}}}}\) exhibit mixed orbital character, while the \(\gamma ,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }-{{{\rm{pockets}}}}\) are primarily dominated by the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital state. Our results indicate that the electronic structure of La3Ni2O7 thin film at ambient pressure closely resembles that of the high-pressure bulk phase. A key structural aspect is the in-plane lattice constant of the thin film, which is 3.77Å–large than the pseudo-tetragonal bulk value of 3.715Å. This lattice expansion may account for the lower Tc of the thin film compared to the bulk, suggesting that strain engineering could be a viable approach to enhancing Tc by further compressing the in-plane lattice constant. Furthermore, we note that the interlayer hopping amplitude \({t}_{AB,[00]}^{z}=-0.550\) is 1.19 times larger than the intralayer nearest-neighbor hopping \({t}_{1}^{x}=-0.462\). However, it remains 13.4% smaller than its bulk counterpart (\({t}_{AB,[00]}^{z}=-0.635\)). This reduction in interlayer coupling suggests a possible weakening of unconventional pairing in the thin film compared to the bulk.

a and c correspond to the double-stacked two-orbital model for the One-UC slab, while b and d correspond to the single-stacked two-orbital model for the Half-UC slab. The color bar indicates the orbital weights, with red and blue represent \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\), respectively. In a and b, the gray lines represent the DFT-calculated band structures with Ueff = 0 eV. The EF is set to 0 eV. Here, Ueff denotes the effective Hubbard parameter, and UC represents the unit cell.

For the Half-UC slab model, no splitting in the Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) bonding bands (See Fig. 4b). Consequently, the Fermi surface consists of two electron pockets α, β and one hole pocket γ, as illustrated in Fig. 4d. Additionally, the interlayer hopping amplitude \({t}_{AB,[00]}^{z}=-0.503\) is 1.13 times larger than the intralayer nearest-neighbor hopping \({t}_{1}^{x}=-0.445\), yet it remains 21% smaller than its bulk counterpart. Notably, when we set \({t}_{AB}^{12,z}=0\), no splitting is observed in the band structure or the Fermi surface of the One-UC slab, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

High-energy d p models

To incorporate the effects of O−p orbitals, we introduce high-energy dp models: a double-stacked eleven-orbital model for the One-UC slab (referred to as twenty-two-orbital model) and a single-stacked eleven-orbital model for the Half-UC slab (referred to as the eleven-orbital model). In both models, the basis for Stack 1 is given by \(\Psi ={({d}_{Az},{d}_{Bz},{d}_{Ax},{d}_{Bx},{d}_{A{p}_{x}},{d}_{B{p}_{x}},{d}_{A{p}_{y}},{d}_{B{p}_{y}},{d}_{{p}_{z}},{d}_{{p}_{{z}^{{\prime} }}},{d}_{{p}_{{z}^{{\prime\prime} }}})}^{T}\), which includes four in-plane orbitals (pAx, pAy, pBx, pBy) and three apical orbitals (\({p}_{z},{p}_{{z}^{{\prime} }},{p}_{{z}^{{\prime\prime} }}\)), as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4. Here, A and B denote the bilayer sublattices.

The TB parameters of the twenty-two-orbital model are listed in Table 4, while those of the eleven-orbital model are provided in Table 5. Due to the symmetry between Stack 1 and Stack 2, only the parameters for Stack 1 are presented, and inter-stack hopping terms are not considered. Both models incorporate hopping interactions arising from pd, pp orbital overlaps. Based on the TB parameters, we present the resulting band structure and Fermi surface for both the One-UC and Half-UC slabs, as shown in Fig. 5. The resulting band structure in Fig. 5 covers an energy range akin to that of Fig. 4 and can also reproduce the main features at EF. Furthermore, we find a hopping of 1.296 for the eleven-orbital model and of 1.304/1.105 for the twenty-two-orbital model between \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital and two apical \({p}_{{z}^{{\prime} }},{p}_{{z}^{{\prime\prime} }}\) orbitals, which are crucial in estimating effective interlayer \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) spin exchange coupling. The high-energy models would provide a foundation for further investigations of magnetic exchange coupling and electronic correlations.

a and c correspond to the eleven-orbital model for the Half-UC slab, while b and d correspond to the twenty-two-orbital model for the One-UC slab. The color bar indicates the orbital weights, with red and blue representing \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\), respectively. In a and b, the gray lines represent the DFT-calculated band structures with Ueff = 0 eV. The EF is set to 0 eV. Here, Ueff denotes the effective Hubbard parameter, and UC represents unit cell.

Spin susceptibility for two-orbital models

With the multi-orbital Hubbard model defined above, we investigate the magnetic response and Fermi surface nesting by calculating the spin susceptibility at the RPA level. Given that inter-stack hoppings are weak, we neglect them in our analysis. The resulting Fermi surface and energy bands in the absence of inter-stack hopping are provided in the Supplementary Fig. 3.

To better demonstrate the Fermi surface nesting relations associated with the bilayer structure, we define the even and odd magnetic susceptibilities as: χe/o = χ∣∣ ± χ⊥, with χ∣∣ and χ⊥ representing intralayer and interlayer contributions, respectively. The definitions and computational details are available in the Methods section. Physically, it is easily proved that the χe originates from nestings within the bonding (α, γ) and within the antibonding (β) bands, while χo originates solely from nestings between the bonding and antibonding bands56.

Figure 6 presents the static RPA spin susceptibility χe/o(q, ω = 0) for the double-stacked two-orbital model, computed with U = 0.7 eV, JH = 0.2 eV, and temperature T = 0.1K. In the even channel, we observe a strong response near the X point, indicating nesting within the γ pocket, along with additional nesting within the β pocket. In the odd channel, nesting is evident between the β and γ pockets, as well as between the α and β pockets.

a and b show the even channel (χe) and odd channel (χo) susceptibilities for the double-stacked two-orbital model, respectively, calculated with intraorbital Coulomb interaction U = 0.7 eV and Hund’s coupling JH = 0.2 eV at a temperature T = 0.1K. c and d depict the Fermi surfaces, where red arrows indicating the nesting vectors.

Figure 7 presents the spin susceptibility for the single-stacked two-orbital model, calculated using U = 0.8 eV, JH = 0.2 eV and T = 0.1K. The Fermi surface nesting patterns in the odd channel closely resemble those of the double-stacked model. In the even channel, nesting primarily occurs within the γ and β pockets, whereas in the odd channel, significant nesting is observed between the γ and β pockets, as well as between the α and β pockets. The observed differences in χe/o between the double-stacked and single-stacked models can be attributed to their distinct Fermi surface geometries.

a and b show the even channel (χe) and odd channel (χo) susceptibilities for the single-stacked two-orbital model, respectively, calculated with intraorbital Coulomb interaction U = 0.8 eV and Hund’s coupling JH = 0.2 eV at a temperature T = 0.1K. c and d present the Fermi surfaces, where red arrows indicate the nesting vectors.

Methods

First-principles calculations

Our first-principles calculations are performed using the DFT as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)57,58. The exchange-correlation interactions are treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional59. The projector augmented-wave (PAW) method60 is employed with a plane-wave cutoff energy of 600 eV. Structural relaxation and electronic self-consistent calculations are conducted on a Γ-centered 12 × 12 × 1 k − points mesh using the Monkhorst-Pack scheme, while a denser k − points grid of 27 × 27 × 1 is used for Fermi surface calculations. The atomic positions are fully relaxed until the residual forces on each atom are less than 0.005 eV/Å, and the electronic self-consistency convergence criterion is set to 10−6 eV. The optimized atomic coordinates are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and 2 for the Half-UC structure with Ueff = 0 and 2 eV, respectively, and in Supplementary Data 3 and 4 for One-UC structure with Ueff = 0 and 2 eV, respectively.

To construct effective models, maximally localized Wannier functions are obtained using the Wannier90 code61,62,63. For DFT + U calculations64, an effective Hubbard Ueff is applied to the Ni 3d orbitals.

Hamiltonian of high-energy d p models

For the twenty-two-orbital model, we do not consider the hoppings between orbitals in different stacks. So the Hamiltonian of the twenty-two-orbital model takes the same form as the one for the eleven-orbital model. Here we show the TB Hamiltonian for high-energy dp models3. The basis here is \((A{d}_{z},B{d}_{z},A{d}_{x},B{d}_{x},A{p}_{x},B{p}_{x},A{p}_{y},B{p}_{y},{p}_{z},{p}_{{z}^{{\prime} }},{p}_{{z}^{{\prime\prime} }})\). The position of these orbitals can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 4. Her,e we show the elements of Hamiltonian H(α, β)

The elements H(β, α) can be obtained by H(β, α) = H(α, β)*. The diagonal elements are site energies which can be found in Tables 4 and 5.

Calculation of spin susceptibility

Upon determining the hopping parameters of the TB models and incorporating electron interactions, we construct a multi-orbital Hubbard model as Eq. (1) without considering hoppings between two stacks.

The TB Hamiltonian \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\) is expressed with the basis Ψσ = (dAxσ, dAzσ, dBxσ, dBzσ), where dsσ is the annihilation operator for an electron in the state s = (Ax, Az, Bx, Bz) with spin σ. The interaction parameters include U (intraorbital Coulomb interaction), \({U}^{{\prime} }\) (interorbital Coulomb interaction) and JH (Hund’s coupling). Kanamori relation is applied here, given by \({U}^{{\prime} }=U-2{J}_{H}\)55.

In general, the bare (non-interaction) susceptibility is defined as

with the band indices m, n and the Fermi-Dirac distribution function \({f}_{F}({\varepsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}})=1/({{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{\varepsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}/T}+1)\). The matrix element Uδm(k) represents the eigenvector connecting orbital δ and band m at wave vector k. At the RPA level, the spin channel interaction vertex is defined as

Here pair hopping \({J}^{{\prime} }\) satisfies \({J}^{{\prime} }={J}_{H}\). The RPA spin susceptibility is then computed in a matrix-product form as

Considering the bilayer structure of La3Ni2O7, the interlayer hopping terms in the Hamiltonian acquire a phase factor of \({{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{k}_{z}}\) due to the kz − dependence. Here, kz can take values of either 0 or π. When contracting the orbital indices to compute the spin susceptibility, we define the in-plane and interlayer susceptibilities as χ∣∣ = ∑αβ(χAαAβ + χBαBβ) and χ⊥ = ∑αβ(χAαBβ + χBαAβ), where χαβ = χααββ with orbital indices contracted. For kz = 0, the phase factor ei0 = 1, and the spin susceptibility is given by χe = χ∣∣ + χ⊥. Conversely, for kz = π, the phase factor eiπ = − 1, leading to a spin susceptibility of χo = χ∣∣ − χ⊥. In the even channel χe, Fermi surface nesting which occurs within the bonding/antibonding bands is evident, including the α−α, α−γ, γ−γ and β−β nesting features. In the odd channel χo, nesting between bonding and antibonding bands can be observed clearly, such as γ−β, α−β56.

Discussion

Our DFT calculations of the thin-film bilayer nickelate superconductors have overall predicted that the electronic structure closely resembles the bulk one under pressure, which strongly suggests that they are all within the same superconducting mechanism. We note another key aspect to validate this idea, which is the superexchange strength. For the bulk samples, the vertical superexchange between two half-filling \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals \({J}_{\perp }^{z}\) is widely believed to be the origin of the superconducting condensation6,7. Here, our TB models for the La3Ni2O7 thin-film also allow an estimation of the corresponding strengths, which are decreased by ~36% and ~24% for single-stacked and double-stacked bilayer nickelates with respect to the pressurized bulk3, assuming \({J}_{\perp }^{z} \sim {({t}^{z})}^{2}\). The asymptotic decrease of \({J}_{\perp }^{z}\) with slab number from our estimation is in line with the notable decrease of Tc from bulk to film as observed in experiments47,48, which again reinforces the above general understanding. More profoundly, the consistency indicates an expansion of the available experimental techniques for reaching the core of the superconducting mechanism in RP nickelates. This is particularly helpful as the exploration of bulk is largely constrained by the exerted pressure. Regarding the role of pressure, on the other hand, the existing evidence on thin-film is also prone to the idea that pressure can help suppress the spin density wave, after which the superconducting order is thus exposed. Whereas for the thin-film, due to the higher stability and sniffiness of the SrLaAlO4 substrates, \({{{{\rm{L{a}}}_{3}N{i}_{2}O}}}_{{{{\rm{7}}}}}\) the lattice is strongly confined to the I4/mmm symmetry without in-plane distortion, which can further prevent the occurrence of density waves47,48.

On the other hand, it is worth noting that the structural differences between the One-UC and Half-UC slab models–particularly the presence of inter-stack geometry in the One-UC case–lead to more three-dimensional electronic characteristics. In particular, the enhanced interlayer coupling in the One-UC structure gives rise to noticeable out-of-plane (kz) direction. This suggests that such kz-dependent features may be experimentally observable in future high-resolution ARPES measurements, providing an additional means to probe the dimensionality and electronic reconstruction in La3Ni2O7 thin films.

We note that both experimental and theoretical studies have reported differing results regarding the Fermi surface topology. While Ref. 65 reports a lowering of the \({{{\rm{Ni}}}}-{{{{\rm{d}}}}}_{{z}^{2}}\) states under compressive strain, an independent group has observed a \({{{{\rm{d}}}}}_{{z}^{2}}\)-derived γ-pocket at the Fermi level in La2PrNi2O7 thin films, accompanied by a measurable superconducting gap on this pocket50,51. These contrasting observations suggest that the presence or absence of the γ-pocket may be sample-dependent, potentially influenced by factors such as oxygen stoichiometry or subtle strain variations. On the theoretical side, previous studies66,67 examined the effect of biaxial strain on bulk nickelates and found that compressive strain tends to increase the apical Ni-O-Ni bond angle toward 180∘, consistent with structural features of the high-pressure phase. Other works68,69, adopting the lower-pressure Amam phase as a reference and employing DFT + U methods, reported the emergence of \({{{{\rm{d}}}}}_{{z}^{2}}\)-derived pockets at the Fermi surface under tensile strain. It is well established that the calculated electronic structure of La3Ni2O7 is highly sensitive to the choice of the Hubbard Ueff parameter (see Supplementary Fig. 1). We anticipate that future experimental studies will help resolve these discrepancies and clarify the microscopic origin of the observed differences.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we employ slab models for La3Ni2O7 thin films that simulate the electronic structure for various thicknesses, including Three-UC, One-UC, and Half-UC. Each slab model incorporates a full unit cell, with the two bilayers referred to as Stack 1 and Stack 2, enabling a detailed examination of the interplay between dimensionality and electronic behaviors. Using density functional theory, we propose a double-stacked two-orbital effective model of La3Ni2O7 thin films, based on the Ni−eg orbitals. Our analysis reveals the presence of three electron pockets \(\alpha ,{\alpha }^{{\prime} },\beta\) and two hole pockets \(\gamma ,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) on the Fermi surface, where the additional pockets \({\alpha }^{{\prime} }\) and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) emerge due to inter-stack interactions. Furthermore, we introduce high-energy models incorporating O−p orbitals to facilitate future studies. Spin susceptibility calculations within the RPA indicate pronounced magnetic correlations primarily driven by nesting effects of the γ pocket, which is predominantly contributed by the Ni\(-{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbital state. Our results provide theoretical framework for understanding the interplay among dimensionality, magnetism, and superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 thin films, offering key insights for future theoretical and experimental research.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493–498 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Superconductivity in pressurized trilayer La4Ni3O10−δ single crystals. Nature 631, 531–536 (2024).

Luo, Z., Hu, X., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. Bilayer two-orbital model of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 126001 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, dimer physics, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic tendencies in the bilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 180510 (2023).

Lechermann, F., Gondolf, J., Bötzel, S. & Eremin, I. M. Electronic correlations and superconducting instability in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 201121 (2023).

Luo, Z., Lv, B., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. High-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 based on the bilayer two-orbital t-J model. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 1–7 (2024).

Wú, W., Luo, Z., Yao, D.-X. & Wang, M. Superexchange and charge transfer in the nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 117402 (2024).

Wang, M., Wen, H.-H., Wu, T., Yao, D.-X. & Xiang, T. Normal and superconducting properties of La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41(7) https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/41/7/077402 (2024)

Shilenko, D. A. & Leonov, I. V. Correlated electronic structure, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic correlations in double-layer La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 125105 (2023).

Yang, Y.-f, Zhang, G.-M. & Zhang, F.-C. Interlayer valence bonds and two-component theory for high-Tc superconductivity of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, 201108 (2023).

Huang, J., Wang, Z. D. & Zhou, T. Impurity and vortex states in the bilayer high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174501 (2023).

Christiansson, V., Petocchi, F. & Werner, P. Correlated electronic structure of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 206501 (2023).

Shen, Y., Qin, M. & Zhang, G.-M. Effective bi-layer model hamiltonian and density-matrix renormalization group study for the high-tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 127401 (2023).

Oh, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Type-II t−J model and shared superexchange coupling from hund’s rule in superconducting La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174511 (2023).

Liu, Y.-B., Mei, J.-W., Ye, F., Chen, W.-Q. & Yang, F. s±-wave pairing and the destructive role of apical-oxygen deficiencies in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 236002 (2023).

Liao, Z. et al. Electron correlations and superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure tuning. Phys. Rev. B 108, 214522 (2023).

Yang, Q.-G., Wang, D. & Wang, Q.-H. Possible s±-wave superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 140505 (2023).

Chen, C.-Q., Luo, Z., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. Trilayer multiorbital models of La4Ni3O10. Phys. Rev. B 110, 014503 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Origin of the density wave instability in trilayer nickelate La4Ni3O10 revealed by optical and ultrafast spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 111, 075140 (2025).

Yang, J.-J., Yao, D.-X. & Wu, H.-Q. Correlation effects in a simplified bilayer two-orbital Hubbard model at half filling. Phys. Rev. B 110, 235155 (2024).

Kaneko, T., Sakakibara, H., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Pair correlations in the two-orbital Hubbard ladder: Implications for superconductivity in the bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045154 (2024).

Ouyang, Z., Gao, M. & Lu, Z.-Y. Absence of electron-phonon coupling superconductivity in the bilayer phase of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 1–6 (2024).

Sakakibara, H. et al. Theoretical analysis on the possibility of superconductivity in the trilayer Ruddlesden-Popper nickelate La4Ni3O10 under pressure and its experimental examination: Comparison with La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144511 (2024).

Heier, G., Park, K. & Savrasov, S. Y. Competing dxy and s± pairing symmetries in superconducting La3Ni2O7:LDA+FLEX calculations. Phys. Rev. B 109, 104508 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Structural phase transition, s±-wave pairing, and magnetic stripe order in bilayered superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Nat. Commun. 15, 2470 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, magnetic correlations, and superconducting pairing in the reduced Ruddlesden-Popper bilayer La3Ni2O6 under pressure: Different role of \({d}_{3{z}^{2}-{r}^{2}}\) orbital compared with La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045151 (2024).

Tian, Y.-H., Chen, Y., Wang, J.-M., He, R.-Q. & Lu, Z.-Y. Correlation effects and concomitant two-orbital s±-wave superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 165154 (2024).

Ryee, S., Witt, N. & Wehling, T. O. Quenched pair breaking by interlayer correlations as a key to superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 096002 (2024).

Zhang, J.-X., Zhang, H.-K., You, Y.-Z. & Weng, Z.-Y. Strong pairing originated from an emergent Z2 berry phase in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 126501 (2024).

Ni, X.-S. et al. Spin density wave in the bilayered nickelate La3Ni2O7−δ at ambient pressure. npj Quantum Mater. 10, 1–9 (2025).

Lu, C., Pan, Z., Yang, F. & Wu, C. Interlayer-coupling-driven high-temperature superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 146002 (2024).

Qu, X.-Z. et al. Bilayer t−J−J⊥ model and magnetically mediated pairing in the pressurized nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036502 (2024).

Yang, H., Oh, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Strong pairing from a small Fermi surface beyond weak coupling: Application to La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, 104517 (2024).

Fan, Z. et al. Superconductivity in nickelate and cuprate superconductors with strong bilayer coupling. Phys. Rev. B 110, 024514 (2024).

Sakakibara, H., Kitamine, N., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Possible high Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure through manifestation of a nearly half-filled bilayer Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 106002 (2024).

Cao, Y. & Yang, Y.-f. Flat bands promoted by Hund’s rule coupling in the candidate double-layer high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 081105 (2024).

Jiang, R., Hou, J., Fan, Z., Lang, Z.-J. & Ku, W. Pressure driven fractionalization of ionic spins results in cupratelike high-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 126503 (2024).

Chen, X., Jiang, P., Li, J., Zhong, Z. & Lu, Y. Charge and spin instabilities in superconducting La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 111, 014515 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Orbital-dependent electron correlation in double-layer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 4373 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-temperature superconductivity with zero resistance and strange-metal behaviour in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 20, 1269–1273 (2024).

Hou, J. et al. Emergence of high-temperature superconducting phase in pressurized La3Ni2O7 crystals. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 117302 (2023).

Fan, S. et al. Tunneling spectra with gaplike features observed in nickelate La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. B 110, 134520 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Pressure-Induced Superconductivity In Polycrystalline La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011040 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Electronic correlations and partial gap in the bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 7570 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Signature oF Superconductivity In Pressurized La4Ni3O10. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 017401 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Identification of the superconductivity in bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7 upon 100 GPa. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.11369 (2025).

Ko, E. K. et al. Signatures of ambient pressure superconductivity in thin film La3Ni2O7. Nature 638, 935–940 (2025).

Zhou, G.et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity onset above 40 K in (La, Pr)3Ni2O7 films. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08755-z (2025)

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state transport in compressively strained La2PrNi2O7 thin films https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.08022 (2025).

Li, P. et al. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy of superconducting La2.85Pr0.15Ni2O7/SrLaAlO4 heterostructures. National Science Review, 205 https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaf205 (2025)

Shen, J. et al. Nodeless superconducting gap and electron-boson coupling in (La, Pr, Sm)3Ni2O7 films https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.17831 (2025).

Yue, C. et al. Correlated electronic structures and unconventional superconductivity in bilayer nickelate heterostructures https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.06875 (2025).

Shao, Z.-Y., Liu, Y.-B., Liu, M. & Yang, F. Band Structure and Pairing Nature of La3Ni2O7 Thin Film at Ambient Pressure https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.10409 (2025).

Bhatt, L. et al. Resolving Structural Origins for Superconductivity in Strain-Engineered La3Ni2O7 Thin Films https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.08204 (2025).

Georges, A., Medici, L. D. & Mravlje, J. Strong correlations from Hund's coupling. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 137–178 (2013).

Bötzel, S., Lechermann, F., Gondolf, J. & Eremin, I. M. Theory of magnetic excitations in the multilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 180502 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Böchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847–12865 (1997).

Souza, I., Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Wang, B.Y. et al. Electronic structure of compressively strained thin film La2PrNi2O7. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.16372 (2025).

Zhao, Y.-F. & Botana, A. S. Electronic structure of Ruddlesden-Popper nickelates: Strain to mimic the effects of pressure. Phys. Rev. B 111, 115154 (2025).

Bhatta, H.C.R.B., Zhang, X., Zhong, Y. & Jia, C. Structural and Electronic Evolution of Bilayer Nickelates Under Biaxial Strain. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.01624 (2025).

Geisler, B., Hamlin, J.J., Stewart, G.R., Hennig, R.G. & Hirschfeld, P.J. Fermi surface reconstruction and enhanced spin fluctuations in strained La3Ni2O7 on LaAlO3(001) and SrTiO3(001). https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.14600 (2025).

Geisler, B., Hamlin, J.J., Stewart, G.R., Hennig, R.G. & Hirschfeld, P.J. Electronic reconstruction and interface engineering of emergent spin fluctuations in compressively strained La3Ni2O7 on SrLaAlO4(001). https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.10902 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Wéi Wú and Xiao-Hong Pan for useful discussions. Work at Sun Yat-Sen University was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12494591, No. 92165204), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1402802), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Magnetoelectric Physics and Devices (Grant No. 2022B1212010008), Research Center for Magnetoelectric Physics of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2024B0303390001), Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative (Grant No. GDZX2401010), and Leading Talent Program of Guangdong Special Projects (201626003), and National Supercomputer Center in Guangzhou.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.X.Y. and X.H. proposed and designed the project. X.H. and C.Q.C. contributed to DFT calculations. X.H. and D.X.Y. contributed to two-orbital models. W.Q. and D.X.Y. contributed to high-energy models. W.Q. and Z.L. contributed to spin susceptibility and discussion under the supervision of D.X.Y. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Qiu, W., Chen, CQ. et al. Electronic structures and multi-orbital models of La3Ni2O7 thin films at ambient pressure. Commun Phys 8, 506 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02411-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02411-8