Abstract

Data-driven modeling of collective dynamics is a challenging problem because emergent phenomena in multi-agent systems are often shaped by short- and long-range interactions among individuals. For example, in bird flocks and fish schools, flow coupling plays a crucial role in emergent collective behavior. Such collective motion can be modeled using graph neural networks (GNNs), but GNNs struggle when graphs become large and often fail to capture long-range interactions. Here, we construct hierarchical and equivariant GNNs, and show that these GNNs accurately predict local and global behavior in systems with collective motion. As representative examples, we apply this approach to simulations of clusters of point vortices and populations of microswimmers. In these systems, our approach is more accurate and faster than a fully-connected GNN. Specifically, only our approach conserves the Hamiltonian for the point vortices and only our approach predicts the transition from aggregation to swirling for the microswimmers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A wide range of non-living and living systems exhibit collective motion in which emergent behavior appears from simple interaction laws1. Examples include shaken metallic rods2, micromotors3, bacteria colonies4, birds flocking5, and pedestrian dynamics6. Often, the interaction laws dictating these systems are unknown, making them an ideal candidate for data-driven modeling. However, although many data-driven methods exist for forecasting dynamics, including recurrent neural networks7, neural ODEs8, and reservoir computing9, which have proven effective in chaotic systems10,11,12,13, turbulent fluid flows14,15, and weather forecasting16,17, these methods are not suited for learning the interaction laws that lead to emergent collective phenomena in multi-agent systems. Here, to overcome these challenges, we propose the use of graph neural networks (GNN) that account for the hierarchical and equivariant nature of many collective dynamics systems.

GNNs are popular in modeling multi-agent systems and simulations on unstructured grids because the number of agents in the graph can vary, and the spatial relationship between agents can be incorporated into the graph. For example, GNNs have been used in particle-based physics simulations18,19 of Lagrangian fluid simulations20 and granular flows21. Xiong et al.22 extended these ideas to vortex datasets by using a detection network to identify vortices and then forecasting the detected vortices using a GNN similar to Battaglia et al.23. Another use of GNNs for fluid simulations is for mesh-based models24, by treating each grid point as a node in a graph. Peng et al.25 applied GNNs for reduced-order modeling of convex channel flow and expansion flows.

Standard GNNs are purely data-driven and must learn physical properties from that data, which presents a challenge if these properties must be exactly satisfied. One such property in many physical systems is symmetry. For example, the dynamics of fluid in a straight pipe are equivariant to rotations and reflections and invariant to translations down the pipe26. A function is equivariant when an action on the input of the function has a corresponding action on the output that makes the two equivalent. Exactly satisfying these properties in data-driven tools presents a major challenge. Many GNN methods present specific architectures to guarantee types of equivariance such as E(3) equivariance27,28, E(n) equivariance29, steerable E(3)-equivariant30,31, and SE(3)-equivariance32. These types of methods have also been combined with other popular methods like neural ODEs33 and transformers34,35 for multi-agent problems. Furthermore, equivariant GNNs have been applied to irregular meshes for fluid simulations36,37.

Most of these methods account for equivariance by using specific choices of the GNN architecture. Alternatively, equivariance can be enforced by mapping the data to an invariant space and mapping the resulting output back. This has the advantage of enforcing that any GNN structure guarantees equivariance. We will perform this mapping by modifying a method based on principal component analysis (PCA)38 to address the sign ambiguity problem discussed in ref. 39.

Although the GNN approaches have been used in many problems, less effort has been put toward data-driven modeling of collective motion problems where long-range order appears. Wang et al.40 used GNNs to predict an order parameter in the Vicsek model41, but did not perform time forecasting. Heras et al.42 used deep attention networks and videos of zebrafish to predict the likelihood of a zebrafish turning right after some time. They further used these results to infer interaction rules between fish. For predicting the time-evolution of collective dynamics problems, Ha and Jeong43 developed a method called AgentNet, similar to graph attention networks44, which they used to predict the dynamics of cellular automata, the Vicsek model, active Ornstein–Uhlenbeck particles, and bird flocking.

In what follows, we show the importance of using a hierarchy of local and global graphs and of enforcing equivariance when forecasting collective motion problems that exhibit long-range order. We focus on collective motion examples where long-range interactions play an important role. This differs from systems, like the Viscek model, where long-range order emerges from only local interactions. Importantly, our framework is agnostic to the details of the GNN, making it widely applicable. We test this method on two problems that show the breadth of applicability of our approach: clusters of point vortices and microswimmers. The first represents an example of a large-scale conservative system, the second represents an example of an out-of-equilibrium, non-conservative, active system. In the first one, interactions decay as 1/r, in the second, interactions decay as 1/r2. The latter exhibits a bifurcation as a function of the control parameter. We find that our approach outperforms a fully-connected GNN at predicting short-time tracking and long-time statistical quantities. For the point vortices, our approach more closely conserves the Hamiltonian, and, for the microswimmers, our approach correctly predicts the aggregation to swirling transition.

Results

Graph neural networks for collective motion

Many systems that exhibit collective motion can be modeled with a system of ordinary differential equations (ODE)

where \({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}(t)\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) are the properties of agent i of N agents. As mentioned in the introduction, Eq. (1) may not always be known. Thus, we aim to approximate Eq. (1) directly from data. In particular, we aim to approximate Eq. (1) by training a method that predicts the right-hand side of the ODE

where \(\tilde{\cdot }\) indicates an approximation, to minimize the loss given by

In Eq. (2), θ corresponds to the training parameters of the data-driven model that are updated to minimize the loss over a batch of M data points. Here, we construct Eq. (2) using graph neural networks. GNNs are a class of data-driven methods that apply neural networks to graph data. A graph G = (V, E) consists of a set of nodes (vertices) V = {v1, v2, …, vN} connected by edges E = {e1,1, e1,2, …, eN,N}45. On this graph, we define node weights (i.e., signals) \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}:V\to {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) and edge weights \({W}_{i,j}:E\to {\mathbb{R}}\). These edge weights are also known as the weighted adjacency matrix. They are used to construct the normalized graph Laplacian L = I−D−1/2WD−1/2, where Di,i = ∑jWi,j is the diagonal degree matrix and I is the identity. Here, we consider undirected graphs, which results in a symmetric adjacency matrix, allowing us to write the graph Laplacian in this form. The eigenvectors of the normalized graph Laplacian are known as graph Fourier modes, which enable us to perform graph convolutions46.

Our objective is to perform a series of GNN operations to map from a set of initial graphs whose nodal values contain information on properties of the agents ri to a final graph whose nodal values output the estimated dynamics \({\rm {d}}{\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}/{\rm {d}}t\). Similar to deep convolutional neural networks, we perform this mapping through graph convolutions in which we expand the nodal values of the graph from \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) to graphs with nodal values \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{(j)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{j}}\). We repeat this process for multiple layers, and end by mapping the Kth graph \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{(K)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{K}}\) to the output \({{{\bf{o}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{o}}\) which predicts \({\rm {d}}{\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}/{\rm {d}}t\). In this process, we introduce nonlinearity after each graph convolution operation through an activation function, and we compute edge weights based on the distance between nodes. In the “Graph convolutions” subsection of the “Methods” section, we describe these operations in more detail.

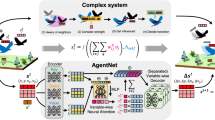

A key factor in the performance of the GNN is how the graphs are constructed. Figure 1 presents three styles of graph construction. One approach is to generate a fully connected graph with the agents’ properties ni = ri. Unfortunately, this graph construction results in an expensive forward pass of the GNN because the network is dense, and hinders training as the GNN must learn which connections are more or less important. Another approach is to generate a graph in which only local connections within some radius R (or k-nearest neighbors) are retained. This approach reduces the computational cost by removing unimportant connections, but could omit the importance of many weak long-range interactions. Instead of adopting these approaches, we construct a hierarchy of local Gl (short-range interactions) and global Gg (long-range interactions) graphs. The advantage of this approach is that it accounts for long-range interactions while decreasing computational costs and improving training performance. While here we only consider constructing a hierarchy of graphs at two scales, the approach easily extends to graphs at more scales by performing the graph convolutions at each scale.

a The fully-connected graph connects every node to every other node. b The hierarchical graph connects all nearby edges in a local graph (solid lines) and aggregates long-range properties in a global graph (dashed lines). Squares denote aggregated long-range properties. c The equivariant graph contains the same connections as either of the two graphs, but maps the nodes to a rotation-invariant reference frame (light colors) based on the angle θe. Nodes of the same color interact locally.

Enforcing equivariance

Consistent with the physical properties of the collective dynamics, the GNNs should retain invariance to translations and equivariance to rotations. For our GNN to satisfy these properties for some abstract group \(g\in {{\mathcal{G}}}\), then for some group action Tg on the input, there exists a group action on the output Sg that satisfies

For illustrative purposes, consider the case where the agents’ properties correspond to the agents’ location in two dimensions (i.e., \({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}={[{x}_{i},{y}_{i}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\)). In this case, the translation operation on the input is \({T}_{{{\rm{g}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i})={[{x}_{i}+{g}_{x},{y}_{i}+{g}_{y}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\), and the translation operation on the output Sg is the identity (this is also known as invariance). When all the agents translate by some fixed amount, there is no change in the vector field. We can also write out the rotation operation on the input as

which is equivalent to rotating the vector field, instead of the input, with \({S}_{{{\rm{g}}}}({\tilde{{{\bf{f}}}}}_{i}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i};\theta ))=R({\theta }_{{{\rm{g}}}}){\tilde{{{\bf{f}}}}}_{i}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i};\theta )\).

To enforce equivariance to rotations and invariance to translations, we must either design a GNN that satisfies Eq. (4) by construction or we must map the input to an invariant subspace \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}\), and then apply the appropriate actions to the output. We take the latter approach as it enforces equivariance with any GNN structure. This approach is often taken to map the solutions of partial differential equations, with continuous spatial symmetry, to an invariant subspace using the method-of-slices47,48.

The objective when defining a translation and rotation invariant state representation \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}={{\mathcal{I}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i})\) is to find a mapping such that \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}\) does not change for any Tg. This can be achieved by defining \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}=R(-{\theta }_{{{\rm{e}}}})({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}-{{{\bf{r}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}})\), where rc is a point in space that we center the data about, and θe is a unique phase. Both rc and θe depend on [r1, …, rN]. Then, if we approximate the dynamics with

we guarantee that \({\tilde{{{\bf{f}}}}}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) will automatically satisfy Eq. (4) regardless of the GNN we use for \({\tilde{{{\bf{f}}}}}_{i}\). We discuss the specific methods for computing rc and θe when describing our test cases.

We summarize the steps for our hierarchical equivariant GNN (HE-GNN) in Fig. 2: (a) construct a hierarchy of local and global graphs (Gl and Gg), (b) map the graph to a rotational and translational invariant subspace by centering the data and rotating by θe, (c) input the rotational and translational invariant graphs into a GNN, and (d) rotate the output of the GNN back (to the original orientation for forecasting). We perform the same GNN operations on the local and global graphs. In what follows, we demonstrate the capability of the HE-GNN method to predict the collective dynamics of point vortices and microswimmers. All results shown are on test datasets not used during the GNN training.

Illustrates the four steps a–d in the method using the point vortex problem. Solid lines are local edges for the local graph (Gl), dashed lines are global edges for the global graph (Gg), and the angle for enforcing equivariance to rotations is θe. The three colors correspond to different local graphs, where circular nodes contain agent properties and square nodes contain aggregated properties. Dark colors lie in the original space, and light colors lie in the invariant subspace.

We consider these two example problems because they are important problems for fluid mechanics and biological collective motion, and the characteristics of both problems encompass a wide range of other collective motion problems. Both of these systems exhibit macroscale dynamics that necessitate our approach, but there are key differences in defining the hierarchy of graphs and in enforcing equivariance. The graphs are defined differently because the point vortices are clustered and the clusters are time-invariant, whereas the microswimmers do not necessarily contain well-defined clusters. Equivariance is enforced differently because the point vortices do not have an azimuthal orientation, whereas each of the microswimmers has an orientation.

Point vortices

First, we test our model on predicting the dynamics of clusters of point vortices. This is an important application for fluid dynamics problems because many complex flow phenomena can be modeled using vortex methods, including separated flows49, the flow around wind turbines50, and free jet flows51. A review of these methods can be found in refs. 52,53. In these flows, large-scale structures can be well-represented by the interactions of many point vortices; thus, we test our model on predicting the dynamics of clusters of vortices that are governed by the Biot–Savart law54. We investigate the interactions of vortex clusters (clouds) by generating two to five clusters, each with 10–20 vortices randomly placed within a cluster, for both training and testing. Each vortex has a randomly chosen positive strength (circulation) and position within a cluster. Due to one-sided strength and the initial cluster spacing, the clusters stay coherent for long periods of time. We chose these settings to parallel the sparse network methods used in refs. 55,56 on these datasets. Furthermore, it is common to see coherent vortices for extended periods of time in many fluid flows, such as homogeneous isotropic turbulence, flow over a bluff body, and two-dimensional mixing layers. Figure 3d shows example trajectories of this system with five clusters.

We predict the evolution of each vortex cluster using the same GNN. The nodal values ni of the local graph Gl correspond to the vortex position and strength (γi), such that \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}={[{x}_{i},{y}_{i},{\gamma }_{i}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\). In this dataset, we do not vary γi over time, so the GNN only forecasts the dynamics of the vortex position (i.e., \({[d{\tilde{x}}_{i}/{\rm {d}}t,{\rm {d}}{\tilde{y}}_{i}/{\rm {d}}t]}^{T}={\tilde{{{\bf{f}}}}}_{i}({G}_{{{\rm{l}}}},{G}_{{{\rm{g}}}};\theta )\)). The method can account for γi that varies in time, but we consider a dataset where this is not the case for consistency with55,56.

The nodal values of the global graph Gg are \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}={[{x}_{i},{y}_{i},{\gamma }_{i}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\) inside the local cluster and the average position and sum of strength outside of the local cluster \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}={[{\left\langle x\right\rangle }_{{C}_{i}},{\left\langle y\right\rangle }_{{C}_{i}},{\sum }_{k\in {C}_{i}}{\gamma }_{k}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\), where Ci is the set of indices for one of the clusters outside of the local cluster and \({\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle }_{{C}_{i}}\) is the average value within cluster Ci. Figure 2 shows the local graph with solid lines and the global graph with dotted lines. In the local graph, we connect all nodes, and in the global graph, we connect all the local nodes to the global nodes. This is a simple way of defining edges in the graphs, but many other approaches work. For example, if the clusters are large, connections in the local graph could be determined by a radius or k-nearest neighbors. Additionally, we define the adjacency matrix to consist of weights Wi,j = 1/∣∣xi−xj∣∣2. We also tested Wi,j = 1/∣∣xi−xj∣∣, which had around two times greater error. To map to the rotation-translation invariant subspace, we center about the mean \({{{\bf{r}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}=(1/{N}_{{{\rm{c}}}}){\sum }_{i\in {C}_{{{\rm{l}}}}}{{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}\), where Nc is the number of points in the local cluster and Cl are the indices of points in the local cluster. We then define the angle θe based on the angle of the principal components of the local cluster, similar to Xiao et al.38. We describe how we compute this angle in more detail in the “Determining the rotation angle” subsection of the “Methods” section.

With these graphs, we use standard neural network optimization procedures to update the weights of the GNN to minimize the loss in Eq. (3). All models use the same training data, which consists of multiple time series of two to five clusters of 10–20 vortices. We detail the GNN architecture and dataset in the “Point vortices” subsection of the “Methods” section. Following model training, we compute trajectories of the model by evolving an initial condition forward using the GNN ODE with the same ODE solver used in generating test data. We then compare the model trajectories with unseen test data.

We first validate the model performance by comparing the model trajectories to an example trajectory in Fig. 3. The example trajectory appears in Fig. 3d, the HE-GNN model trajectory appears in Fig. 3e, and the fully connected GNN (F-GNN) trajectory appears in Fig. 3f. The F-GNN is a single GNN that uses all edge weights between vortices. This graph is centered by the mean of all the centroids, but does not account for rotational equivariance. The HE-GNN accurately tracks the centroid locations of the test data, whereas the F-GNN dramatically diverges from the test data. Although in theory, the fully connected model should be able to track the test data, the training performance of the fully connected model is much worse because the hierarchical and equivariant properties of the system must be learned during training, whereas these properties are directly enforced in the HE-GNN model.

Now that we have shown in Fig. 3 that qualitatively the vortex clusters appear to align with one another, we next show how accurate this centroid tracking is as we vary the GNN model and the number of clusters. We examine the centroid tracking because we are interested in the collective dynamics of the vortices, but not necessarily how accurately we track each and every vortex. Figure 4 shows the efficacy of different GNN models in tracking the centroid location for two, three, four, and five clusters. The three models we compare include a fully-connected GNN, a hierarchical GNN (H-GNN), and a HE-GNN. The H-GNN does not account for rotational equivariance, but is centered, and otherwise matches the setup of the HE-GNN. In Fig. 4, the hierarchical models do not diverge, whereas the F-GNN diverges with two and five clusters. Furthermore, the hierarchical models show similar errors as the number of clusters varies, despite the additional complexity and network size with more clusters. However, Fig. 4 shows a clear improvement in performance when accounting for equivariance, highlighting the advantage of our HE-GNN approach.

We further validate the efficacy of the HE-GNN model by considering the tracking performance ensemble averaged over 50 different test initial conditions. These initial conditions vary the cluster count, the centroid locations, the vortex locations, and the vortex strength. To perform this averaging, we need a proper notion of time. When vortex clusters are close together, or there are many vortex clusters, the clusters move faster than when the clusters are far apart, or there are fewer clusters. To account for this, we compute the timescale t* = D/Uavg, where D is the cluster diameter and Uavg is the average centroid velocity. This timescale indicates the average time required for a cluster to travel one diameter. We evolved each initial condition forward to t = 200, which results in t/t* ranging from 7.4 to 39.5, depending on the initial condition.

The ensemble-averaged centroid tracking, vortex tracking, and Hamiltonian conservation are shown in Fig. 5. The centroid tracking error supports the results shown in Fig. 4. The HE-GNN substantially outperforms both the F-GNN and the H-GNN. At short times, the models differ in the rate at which the error increases in the three models, and, at long times, the solutions from the F-GNN diverge, while the H-GNN exhibits a larger variance than the HE-GNN. Although the centroid tracking is improved by the HE-GNN (Fig. 5b), the tracking of individual agents is similar between all three models. This error plateaus for the HE-GNN and grows for the other two models. These two results highlight that the HE-GNN accurately captures the collective motion of the centroids, but all models perform similarly in the instantaneous tracking of vortices.

Another crucial quantity in correctly capturing the physics of this problem is the Hamiltonian

This quantity is conserved and depends on all interactions, making it an important test for validating the models. Failure to conserve the Hamiltonian indicates that energy is being injected or dissipated from the system. Figure 5c shows the normalized error in the Hamiltonian. The F-GNN quickly diverges, which also causes the Hamiltonian to diverge because the vortex distances become large. The addition of hierarchy successfully avoids this divergence and leads to much less error in the Hamiltonian. Again, the H-GNN improves upon the F-GNN, and the HE-GNN model shows the best results. The HE-GNN model, on average, only has ~1% error in the Hamiltonian after moving an average distance of over six diameters away, which confirms the importance of embedding equivarience in the GNN formulation.

Next, we show how frequently models fail at long times. In Fig. 5d we plot the fraction of trials at t = 200 where the agent-averaged error is >ϵ given by

where \({\mathbb{I}}\) is the indicator function. We end this plot at ϵ = 6 because the F-GNN line plateaus until ϵ > 400. This shows that more than 60% of the F-GNN models diverge, whereas none of the hierarchical models diverge in this time window. The HE-GNN also outperforms all models once again.

Microswimmers

Next, we test the HE-GNN setup on the dynamics of microswimmers in a doubly periodic domain. These microswimmers move due to a combination of self-propulsion and hydrodynamic interactions. Hydrodynamic interaction plays a dominant role in the collective behaviors of microswimmers and has been considered with Stokesian dynamics57,58, potential flow models59,60,61,62, and lubrication theory63. One common property of these models is the superposition of the flow field generated by each swimmer. Here, we considered a potential dipole model, which we describe in detail in the “Microswimmers” subsection of the “Methods” section. Predicting the far-field all-to-all interaction is challenging because there is no inherent graph structure in the model. This differs from how we could approach local behavior models like the Vicsek model or the 3A model41,64,65, where we could restrict our model to local networks. Furthermore, the inclusion of periodic boundary conditions is both more realistic in that it approximates a large number of microswimmers, and more challenging because of the infinitely far long-range interactions. Thus, this microswimmer model allows us to test whether aggregating long-range interactions with our hierarchical approach can capture these far-field effects.

For the microswimmers, our macroscopic property of interest is the phase transition from aggregation to swirling motion as we vary the microswimmers rotational mobility coefficient ν. There is no rotation of microswimmers at ν = 0. Above ν = 0 the system exhibits swirling, and below ν = 0 the system exhibits aggregation61. The microswimmers have clearly defined orientation angles, but do not have a clearly defined hierarchical structure because the swimmers do not always lie within a distinct cluster. We address this issue by defining a local and global graph for every microswimmer.

The local graph consists of connections between the microswimmer whose dynamics we want to predict and all other microswimmers within a radius R1. We also tested fully connecting all microswimmers inside the circle of radius R1, which increased computation time and did not improve predictive capabilities. Outside of this region, we aggregate the effect of many microswimmers to create a global graph. Here, we define a second region between R1 and R2 and split this region into S = 12 slices. Within these slices, we average the microswimmer properties for the global graph. Figure 6a shows an example of the connectivity of the local and global graphs. We will show the benefits of incorporating a hierarchical structure into the model. We will not show all of the possible ways one could construct a global graph. However, one alternative could be to perform K-means clustering to identify relevant regions instead of segmenting the domain into predefined regions. We will consider fixing the radii (R1 and R2) first, and then vary them at the end of this section.

a Construction of the local (solid line) and global graphs (dotted line) for microswimmers. Blue nodes are in the local graph, red nodes are in the global graph, and black nodes are the agents that were aggregated. b–d show examples of the long-time dynamics (t = 100) for the test data with rotational mobility coefficient ν = −1.0, the HE-GNN model, and the F-GNN model, respectively. The microswimmer’s colors in b–d are for consistency with other figures.

The microswimmers have orientations αi that vary with time. As such, we define agent properties \({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}={[{x}_{i},{y}_{i},{\alpha }_{i}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\). We do not include ν as an agent property because we fix this parameter for each case. For the local graph Gl, the nodal values are \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}={[{x}_{i},{y}_{i},\cos ({\alpha }_{i}),\sin ({\alpha }_{i})]}^{{\rm {T}}}\). We use \(\cos (\alpha )\) and \(\sin (\alpha )\) so that the GNN output changes continuously. Otherwise, the GNN output would be discontinuous as α varies outside 0 to 2π. For the global graph Gg, we use nodal properties \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}={[{\left\langle x\right\rangle }_{{S}_{i}},{\left\langle y\right\rangle }_{{S}_{i}},{\left\langle \cos ({\alpha }_{i})\right\rangle }_{{S}_{i}},{\left\langle \sin ({\alpha }_{i})\right\rangle }_{{S}_{i}},{\left\langle U\right\rangle }_{{S}_{i}}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\), where \({\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle }_{{S}_{i}}\) is the average of all agents in slice Si and \(\left\langle U\right\rangle\) is the magnitude of the vector assuming all agents have a magnitude of 1. We define the adjacency matrix based on the distance between the central agent (i) and the other j agents Wi,j = 1/∣∣xi−xj∣∣2 for the local graph, and between the central agent and the mean locations \({W}_{i,j}=1/| | {{{\bf{x}}}}_{i}-{\left\langle {{\bf{x}}}\right\rangle }_{{S}_{j}}| {| }^{2}\) for the global graph. Finally, we enforce equivariance by centering both the local and global graphs about the central (i) microswimmer (rc = ri) and rotating the graphs such that this microswimmer has an angle of 0 (θe = −αi).

As all microswimmers have the same value of ν, we incorporate ν into the GNN by appending it onto \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{{\prime} (K)}={[\nu ,{{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{(K)}]}^{{\rm {T}}}\), and then predicting \({\rm {d}}{\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}/{\rm {d}}t\) by inputting \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{{\prime} (K)}\) through a dense neural network. We train the GNN models using a dataset that contains 21 trajectories, each with 400 microswimmers initialized randomly. Each trajectory has a different mobility coefficient ν evenly sampled between −1 and 1, so the training contains the transition to aggregation and swirling. Our objective is to construct a GNN that captures both of these behaviors. We again use standard neural network optimization procedures to train GNNs (architectures described in the “Microswimmers” subsection of the “Methods” section) to minimize the loss in Eq. (3).

First, we investigate the efficacy of the HE-GNN model in comparison to a fully-connected GNN model. In the F-GNN, we connect all swimmers in the periodic box and use their shortest distance across all boundaries for computing the edge weights. We perform the same graph convolutions as in the local portion of the HE-GNN model and append ν in the same fashion. Figure 6 compares the state of the microswimmers after evolving from a random initial condition for 100 time units, for the case of strong aggregation. The HE-GNN model correctly predicts the strong aggregation behavior, while the F-GNN fails to aggregate.

Next, we test the ability of the HE-GNN model to capture the phase change and the sensitivity of the HE-GNN model to new initial conditions. Figure 7a and b compare time series of microswimmers from the test data and the HE-GNN model at ν = −0.5 and ν = 0.5, respectively. This HE-GNN model uses R1 = 20 and R2 = 30. At short times, the model closely tracks the location and orientation of the microswimmers, and, at long times, the model captures the aggregation (ν = −0.5) and swirling (ν = 0.5) of the microswimmers. Furthermore, the HE-GNN model is insensitive to the initial condition. Figure 7c shows trajectories starting from the final condition of Fig. 7a with ν = 0.5. Here, the aggregation structures begin to disassemble and transition towards swirling dynamics. This type of dynamics does not exist in the training dataset. Despite this, the model accurately captures the rate at which microswimmers expand out of the clusters at short times and the swirling motion at long times.

Snapshots of microswimmers at various rotational mobility coefficients (ν). Test data is in black and HE-GNN prediction is in blue. a and b begin from the same random initial condition discussed in the “Microswimmers” subsection of “Methods” section. c Is a time series starting from the end condition of a with a different rotational mobility coefficient.

These results show that the HE-GNN model successfully captures the transient dynamics of the microswimmers and predicts the correct phase behavior. We can quantify these results by comparing the microswimmer velocity vi = ∣∣[dxi/dt, dyi/dt]∣∣ and of the rotational activity parameter \(\kappa =(1/N){\sum }_{i = 1}^{N}| {\rm {d}}{\alpha }_{i}/{\rm {d}}t| /{v}_{i}\) between test and HE-GNN predicted time series. Figure 8 shows the probability density function F( ⋅ ) (PDF) of the microswimmer velocity and of the rotational activity parameter for test data covering the first 100 time units (the PDF includes transient data). Capturing the transient dynamics is more challenging than initializing the HE-GNN model with trajectories that have already converged to the long-time dynamics. We consider these statistics because the aggregation and swirling clearly separate with these PDFs—which will not be the case for other order parameters we consider. When ν is negative, the microswimmers aggregate, hindering motion and resulting in low values of vi. When ν is positive, the microswimmers take on a wider range of vi values, which is dictated by repeated hydrodynamic and steric interactions. Both the test data and the HE-GNN model give PDFs with averages v > 1 when ν is large. The hydrodynamic interactions in the swirling motion assist microswimmers to move faster than without microswimmers (where v = 1), which the HE-GNN model accurately captures. The PDF of κ is more difficult to capture because this quantity is averaged over all microswimmers at a given time. Moreover, the set of PDFs ranges multiple orders of magnitude, as illustrated by the logscale. Again, the κ PDF of the HE-GNN model is in good quantitative agreement with the κ PDF of the test data. Here, we have shown that the HE-GNN model accurately captures the phase transition,

Next, we investigate the importance of hierarchy and equivariance by testing a local GNN and a hierarchical GNN. We set the radius to R1 = 20 and R2 = 30. The local GNN (L-GNN) is centered and uses a local graph in radius R1. The hierarchical GNN (H-GNN) differs from the HE-GNN in that it does not account for rotational equivariance. Figure 9a–c shows snapshots of these three approaches at long times for ν = 0.2. While the HE-GNN model retains the correct swirling dynamics (the only dynamics that appear for ν = 0.2), the H-GNN and L-GNN models cause the microswimmers to align. This shows that, when we evolve trajectories for time horizons longer than those used in training, the physical insight enforced in the HE-GNN is important to avoid the incorrect collective behavior. Furthermore, although the alignment exhibited by the H-GNN and L-GNN is inaccurate in this parameter regime, it indicates that the GNN models are capable of exhibiting other forms of collective motion, which is desirable for systems with more than the two phases shown here.

Snapshots of microswimmers predicted using the a HE-GNN, b H-GNN, and c L-GNN at the markers shown in (f). The microswimmers' colors correspond to the colors in (d–f). Time series of the polar order parameter (\(\left\langle P\right\rangle\)) are shown for the rotational mobility coefficients d ν = 0, e ν = 0.2, and f ν = 0.5 using the different GNN models. Each model type has three trajectories from three separately trained models.

This alignment can be identified by computing the polar order parameter

When \(\left\langle P\right\rangle =1\) swimmers are aligned and when \(\left\langle P\right\rangle =0\) swimmers are oriented randomly. In Fig. 9d–f, we show the time evolution of the polar order parameter for each style of model as ν varies. We consider this parameter over 1000 time units, which is 10 times longer than the training data, to examine if model statistics diverge at long times. As shown in Tsang and Kanso61, aggregation happens over short time scales, and the polar order parameter is statistically stationary for more than 3000 time units, so longer simulations are unlikely to exhibit a phase change. It is important that we make this comparison using the polar order parameter because the unphysical alignment exhibited by the H-GNN and L-GNN models cannot be identified when considering the velocity or the rotational activity parameter.

For ν < 0 (not shown), the microswimmers exhibit aggregation in all models, and all models predict low values of \(\left\langle P\right\rangle\). Adding hierarchical and equivariant information is less important during aggregation. Aggregated microswimmers are largely influenced by the local interactions within a cluster, which makes accounting for long-range interactions less important. Also, the clusters that do form are circular, making them approximately rotation invariant. Thus, accounting for equivariance is also less important.

Significant differences appear between the models for ν ≥ 0 because long-range interactions influence the swirling motion exhibited by the microswimmers. When ν = 0, the microswimmers do not rotate (i.e., the polar order stays constant). All three HE-GNN models maintain a nearly constant polar order, whereas the other models develop a small bias, leading to an increase in the polar order at long times. The best hierarchical model maintains a nearly constant polar order, while the local models all diverge substantially.

For higher values of ν, the deviations from the test data become larger. We show ν = 0.2 because the models deviate the most at this value, and we show ν = 0.5 for consistency with Fig. 7. The results are similar in both the ν = 0.2 and 0.5 cases. Only the HE-GNN model maintains low polar order for all the models (with slightly higher values for ν = 0.2). All other models align sometime after 100 time units. The long-time behavior is inconsistent among the other models (i.e., not HE-GNN) because once the alignment increases, the trajectory moves outside of states similar to the training data, making the model predictions poor. Notably, the best H-GNN models track longer than the local models, indicating that the hierarchy of graphs can improve results, and all models output reasonable polar order for the first 100 time units, indicating that the strong alignment happens at longer time ranges than seen in the training data.

We end this section by investigating the importance of the radii (R1 and R2) on model performance. Here, we fix the radius of the global graph to be R2 = R1 + 10. In all the comparisons, we train three models at each value of R1. In Fig. 10a, we show the mean-squared error of predicting dr/dt (Eq. (3)). All models tend to improve as the radius increases to R1 = 20. However, once we increase the radius of the local model further, the error increases, likely due to the additional complexity of training with these larger graphs. In most cases, we see a decrease in model error at a given radius when we increase model complexity, indicating that both the hierarchical and equivariant portions of the HE-GNN model play an important role in model performance.

Performance of models when varying the local radius (R1). a The test mean-squared error in predicting the ODE, b the ensemble-averaged prediction time (Tp), c the average earth mover’s distance between polar order PDFs (\(\left\langle {{\rm{EMD}}}\right\rangle\)), and d the relative compute time (relative to L-GNN R1 = 5). Each model type shows results for three separately trained models at each R1.

To investigate the effect that this error has on tracking performance, we compute the ensemble-averaged prediction time

This corresponds to when the average distance between the true and predicted swimmer increases past some distance ϵ for the first time. Here, we denote the microswimmer position as \({{{\bf{x}}}}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) instead of xi due to how we account for the periodic boundaries. If we used the microswimmer position between −L and L, there could be a large jump in \({{{\bf{x}}}}_{i}(t)-{\tilde{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{i}(t)\) if the swimmer crosses the boundary with the true ODE, but not with the model. To address this, \({{{\bf{x}}}}_{i}^{{\prime} }\) corresponds to the position if we did not map the location back across the periodic boundary. Figure 10b shows the ensemble-averaged prediction time for ϵ = 1. For this plot, we sample 10 initial conditions (every 50 time units) from the test trajectories for all values of ν ≥ 0. We omit ν < 0 because the aggregation leads to long tracking times that skew the results. The prediction time increases as we increase the radius and the model complexity. At R1 = 20, the HE-GNN model performs the best and can track for 10 time units. Once the radius becomes too large, the tracking time starts to decrease for the local model. Bacterial swarming is known to be chaotic and is often referred to as active turbulence66. The chaotic nature of these systems means that trajectories diverge exponentially fast. This prevents long-time tracking and partially explains why the improvement in MSE of a GNN does not directly reflect in the ensemble-averaged prediction time. For example, the MSE of the L-GNN at R1 = 30 is ~4 times larger than the HE-GNN at R1 = 20, yet the HE-GNN only has ~1.5 time units improvement in Tp.

The previous two statistics evaluated instantaneous and short-time tracking of the models. To evaluate the long-time predictive capabilities, we compute the earth mover’s distance (EMD)67 between the PDFs of the polar order parameter of the test data \(F(\left\langle P\right\rangle )\) and the model \(F(\tilde{\left\langle P\right\rangle })\) and average over all values of ν for \(\left\langle {{\rm{EMD}}}\right\rangle\). We perform this calculation for the first 500 time units of data. This concisely evaluates the accuracy of the polar order time series we showed in Fig. 9. The EMD is insensitive to binning and small shifts in the PDFs (unlike the Kullback–Leibler divergence), making it appropriate for this comparison. We compute the EMD by solving a transportation problem in which we find the flow that minimizes the work required to move some “supply” to some “demand”. In this case, the supply corresponds to the true PDF and the demand corresponds to the model PDF, and the work is the flow multiplied by the Euclidean distance between bins in the PDFs. We computed the PDFs with 200 evenly spaced bins between 0 and 1.

Figure 10 c shows the EMD for the various models. The HE-GNN models at R1 = 20 achieve the lowest EMD, which corresponds to the trajectories shown in Fig. 9. As R1 decreases, the EMD increases for all models, and, again, the trend is typically that increased model complexity leads to better results. At R > 20 the local models start to perform better despite the worse short-time model performance. This suggests that although a small radius is better for short-time tracking, a large radius is important to capture long-time statistics that may depend upon long-range interactions. The HE-GNN model performs well because it splits these two effects into the local and global graphs, and the equivariance helps by reducing the amount of training data needed for good model performance. Furthermore, although the EMD is close between the HE-GNN model at R1 = 20 and the L-GNN model at R1 = 30 when averaged over all values of ν, there are specific values where there is a larger discrepancy. Noteably, at ν = 0 the average EMD is 0.4, 3.0, and 4.2 for the HE-GNN at R1 = 20, the H-GNN at R1 = 20, and the L-GNN at R1 = 30, respectively. At ν = 0 there should be no rotation, and these EMD results highlight that only the HE-GNN approach avoids rotation.

Finally, Fig. 10d shows the relative compute time required for each of the models. We compute 20 steps of the ODE solver and normalize by the computation time of the local model with a radius of R1 = 5—the fastest model. When the radius of the local graph is small, adding the global graph slows down the computation; however, as we enlarge the radius, the computation time increases in a quadratic manner due to the enlarged area of the circle and the main computational cost coming from forward passes of the local graph. For example, if we compare the two models that capture the polar order PDFs, the HE-GNN model at R1 = 20 (recall R2 = 30 here) and the local model at R1 = 30, we see that the local model takes more than twice as long to run, even though both models use information from the same number of swimmers. When comparing these two models, the HE-GNN model has better instantaneous performance, better short-time tracking, and slightly increased accuracy in the polar order parameter while taking less than half the time to run. This highlights the clear benefit of our HE-GNN approach.

Discussion

Collective dynamics in which groups of agents interact with one another often display long-range, macroscopic properties. Predicting these macroscopic properties can be difficult in part because the underlying dynamics of these systems may be unknown. This makes these systems a natural choice for data-driven modeling. However, as we have shown, care must be taken in constructing these data-driven models; otherwise, they fail to capture these macroscopic properties. In particular, we showed the importance of constructing a hierarchy of local and global graphs, and the importance of enforcing equivariance to system symmetries (i.e., rotation and translation). By incorporating these properties into a GNN framework, we built accurate data-driven models to predict the dynamics of vortex clusters and a group of microswimmers.

In the case of vortex clusters, we constructed a local graph connecting all vortices within a cluster, and a global graph connecting all vortices within a cluster to the mean values of neighboring clusters. We then mapped the vortices to a rotation-translation invariant subspace, which the GNN used to predict the velocity of the vortices. These HE-GNNs accurately tracked the vortex centroids and conserved the Hamiltonian for extended periods of time. We compared the HE-GNN model to a fully connected graph that did not account for equivariance to rotations. Ideally, the F-GNN should be able to perfectly reconstruct the dynamics because it contains all of the connections from the full simulation. However, when hierarchy and equivariance are not enforced by construction, the model must learn these properties during training. Learning these properties presents a challenge for GNN training because it requires more data and deeper GNNs. This is a problem for GNN training because the dataset needs to be sufficiently rich in sampling all of the different orientations, and GNNs with more weights may be required to learn the hierarchical and equivariant nature of the data.

Next, we applied our approach to predict the dynamics of microswimmers. A few key differences between this problem and the vortex dynamics include: the microswimmers are not in clear clusters, the microswimmers have orientation, and the microswimmers undergo a phase transition as the rotational mobility coefficient changes. We constructed a hierarchy of graphs around each microswimmer in which short-range interactions were directly accounted for, and long-range interactions were combined. We then mapped to a rotation-translation invariant subspace by centering on a microswimmer and rotating by the orientation of that microswimmer. This graph structure maintained the proper polar order parameter, whereas the removal of the hierarchy or the equivariance caused the microswimmers to spontaneously align. Furthermore, this HE-GNN model was also able to capture the transition from an initially aggregated system to a swirling system, which never appeared in the training data. Even in this microswimmer simulation, where there does not exist a clear hierarchical structure, separating short- and long-range interactions substantially improves the tracking capabilities of GNN models. A key insight from our work is that incorporating physical properties in the form of equivariance and separating the influence of short- and long-range interactions dramatically improves the ability of GNN models to capture long-time dynamics in a computationally efficient manner.

We also discovered that, even though the underlying data was simulated with infinitely repeated periodic boundary conditions, we did not need to account for this in the HE-GNN to accurately capture the phase transition. Instead, by introducing additional model parameters, we were able to identify an appropriate radius of local and global interactions. An important consideration for the application of the HE-GNN approach for three-dimensional flows is how to handle the difference between pushers and pullers. This could be achieved by either inputting this information as a nodal property with ni, or by defining separate GNNs for the different types of microswimmers.

In these systems, the flexibility of GNNs was important. The local and global graphs both contained a variable number of nodes in training and testing. For the swimmers, the node count even changed when considering a single test trajectory. Standard data-driven methods, such as dense neural networks, do not typically handle variable input sizes. Furthermore, treating this problem in terms of a graph was useful because it allowed us to incorporate spatial relationships directly into the graph Laplacian.

In the future, we plan to apply this HE-GNN to collective motion with increased complexity, such as those with leaders and followers and those with a wider range of ordered structures. For example, Couzin et al.68 showed that simply adding a weighted preferred direction to a small subset of individuals dramatically influenced group behavior. The HE-GNN approach could easily account for this by including a nodal property that accounts for how informed the individual is in ni. Additionally, the HE-GNN approach should be applied to systems with a greater number of ordered structures. Adding confinement to fish schools or simply increasing individual numbers, for example, can add dynamically changing behavior in addition to emergent behaviors such as schooling, milling, and turning65,69,70. We are also interested in exploring the effectiveness of the HE-GNN approach on experimental data. The HE-GNN could be used to predict when a phase transition should happen using only sparse experimental data.

Outside of applications, we also plan to explore systematic ways of constructing the hierarchy of graphs. For example, tree structures, like those used in the fast multipole method71, could be used to form the hierarchy of graphs; more than two levels of hierarchy could be used, and different distance measurements could be used in connecting the graphs.

Methods

In this section, we provide details on how we perform graph convolutions, account for equivariance, and generate the training for the point vortex and microswimmer problems.

Graph convolutions

One method of performing this graph convolution is with a first-order approximation of a spectral graph convolution72 given by

Here, \({H}^{(1)}=[{{{\bf{h}}}}_{1},\ldots ,{{{\bf{h}}}}_{N}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times {d}_{{{\rm{h}}}}}\), \(X=[{{{\bf{x}}}}_{1},\ldots ,{{{\bf{x}}}}_{N}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times d}\), \(\tilde{L}\) is the renormalized Laplacian, \({\Theta }^{(1)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times {d}_{{{\rm{h}}}}}\) are the learnable parameters, and σ is an elementwise activation function. Our GNNs will consist of repeating K graph convolutions ending in a linear graph convolution (or a standard dense neural network) to map \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{(K)}\) to \({\rm {d}}{\tilde{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}/{\rm {d}}t\). We train the parameters in the filters of these graph convolutions Θ(i) to minimize Eq. (3). For more details on the graph convolution in Eq. (11), we refer readers to Kipf and Welling72. We use a slight variation of this method called Chebyshev graph convolutions46. Although we select a specific GNN architecture for our problems of interest, the methodology we outline is agnostic to this choice.

Determining the rotation angle

Mapping the agents to a rotation-invariant subspace requires a unique phase angle. When this angle is not given by the agent, we can determine this angle using the principal component analysis-based method used in Xiao et al.38. This method involves computing the singular value decomposition of the snapshot matrix

and mapping the data to an invariant subspace using the left singular vectors \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}={U}^{{\rm {T}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}-\left\langle {{\bf{r}}}\right\rangle )\). Unfortunately, due to the sign ambiguity of singular vectors, this transformation is nonunique. In Xiao et al.38, this problem was addressed by considering every possible sign, concatenating all of the resulting orientations, and using a self-attention module. This type of approach accounts for all rotations and improper rotations (i.e., rotation and reflection), as pointed out in ref. 39. Orthogonal matrices with a determinant of 1 apply rotation, and orthogonal matrices with a determinant of −1 apply an improper rotation.

Instead of accounting for all orientations, we directly address this sign ambiguity by modifying the method in Bro et al.73. We also choose not to include improper rotations, although equivariance to reflections may be a desirable property for some problems. The algorithm described in Bro et al.73 chooses the sign of the singular vectors, such that they point in the same direction as a majority of the data points. This is achieved by computing the sign of the singular vectors that maximize

for each singular vector. With this sign, we compute the new left singular vector as \({U}_{k}^{{\prime} }={{\rm{sign}}}({s}_{k}){U}_{k}\). For our purposes, this computation is sufficient to compute a unique left singular matrix that maps all rotations and reflections to the same invariant subspace. The algorithm presented in Bro et al.73 also includes steps to compute the sign of the right singular vectors. However, those steps are unnecessary for our objective of disambiguating the sign of the left singular vectors.

Lastly, we avoid improper rotations by multiplying the final singular vector by the determinant (\({U}_{{\rm {d}}}^{{\prime} }={{\rm{det}}}({U}^{{\prime} }){U}_{{\rm {d}}}^{{\prime} }\)). If the inclusion of improper rotations is desirable, this step can be skipped. We chose to not account for reflections so that both the vortices and the microswimmers only account for the continuous symmetry. However, in the case of microswimmers in two dimensions, reflections could be accounted for by replacing Uk in Eq. (13) with the vector normal to the microswimmer direction, and determining the reflection based on the sign of sk.

With this new left singular matrix, we map to the rotation invariant subspace with \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}={U}^{{\prime} {\rm {T}}}({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}-\left\langle {{\bf{r}}}\right\rangle )\). By performing the rotation with the left singular matrix, we can map to a rotation-invariant subspace for data that lies in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) for any d ≥ 2. In two dimensions, this matrix multiplication is equivalent to performing a rotation with the angle given by \({\theta }_{{{\rm{e}}}}={{\rm{atan}}}2({U}_{1,2}^{{\prime} },{U}_{1,1}^{{\prime} })\), such that \({\hat{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}=R(-{\theta }_{{{\rm{e}}}})({{{\bf{r}}}}_{i}-\left\langle {{\bf{r}}}\right\rangle )\).

Point vortices

We generated the point vortex data by numerically solving the Biot–Savart equation

where \(\hat{{{\bf{k}}}}\) is the out-of-plane unit normal vector. To enforce the conservation of the Hamiltonian, we evolve this ODE forward in time using the explicit extended phase space method described in Tao74. We opted for second-order accuracy (Eq. (2) in Tao74) instead of fourth-order accuracy because it conserved the Hamiltonian and reduced the computational cost. Each initial condition was evolved for T = 50 time units with a step size of Δt = 0.001.

The GNN training data consisted of 200 initial conditions, which we shuffled and performed an 80/20 split for training and validation. Each initial condition consisted of two to five vortex clusters with 10–20 vortices per cluster. The vortex strength of each vortex was randomly chosen with a mean \(\left\langle \gamma \right\rangle =0.1\) and a standard deviation σγ = 0.01 to match the example considered in Nair and Taira55. Each vortex cluster consists of randomly placed vortices within a circle of diameter D0 = 1. The center of each vortex cluster was randomly placed within a circular region with a diameter of 10D0. We resampled the vortex cluster if it fell within a distance of 2.5D0 from another cluster. This selection was motivated by results in Eldredge52, where he showed that a pair of circular co-rotating patches (clusters) does not mix when separated by a distance of 2D0. We chose to increase this cutoff due to randomly chosen positions and strengths of our point vortices within a cluster. Empirically, we found that a separation distance of 2.5D0 did not lead to mixing over the time horizons we considered.

We performed a sweep of GNN parameters to determine appropriate graph convolutions, layer count, width, and activation functions. The GNN structure that provided the best performance was 5 Chebyshev convolution layers with 3 polynomials46. After each layer, we applied a rectified linear unit activation, and then on the final layer, we performed a Chebyshev convolution with 1 polynomial (a linear operation). The nodal inputs are \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), the hidden nodal values are \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{(k)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{64}\), and the outputs are \({{\bf{o}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2}\). The hierarchical and HE-GNN model used the same architecture for both the local and global graphs (with different weights), and the fully connected model used this architecture for the full graph. We trained these models for 50 epochs using an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 10−3 that dropped to 10−4 at 25 epochs, and a batch size of 50. We used PyTorch Geometric75 for training all GNNs. Following training, we tested the model on 50 new initial conditions. We evolved these initial conditions forward T = 200 time units (four times longer than the training data).

Microswimmers

We generated the microswimmer data by considering self-propelled agents that interact with one another through far-field hydrodynamic interactions and near-field steric interactions. Typically, microswimmers are categorized into pushers (e.g., E. coli) and pullers (e.g., Chlamydomonas) because they exhibit different hydrodynamic interactions in three dimensions via force dipoles in different directions76,77. Here, we consider microswimmers under strong confinement (two-dimensional)61,62,78, which results in a flow signature described by vortex dipoles. Note that this differs from the force dipole typically considered for three-dimensional microswimmers76.

The properties rn(t) of swimmer n consist of its location xn and orientation αn. To model hydrodynamic interactions, we treated each microswimmer as a potential dipole that generates the complex flow field

where ux and uy are the velocities in the x and y directions, σn is the dipole strength, and z = x + iy is the position in the complex plane. These agents are propelled with velocity U and are repelled from each other via near-field Leonard-Jones potential Vn. We considered microswimmers in a doubly-periodic domain of length L, resulting in the equations of motion

where \(\bar{w}={u}_{x}-{\rm {i}}{u}_{y}\) is the complex velocity, given by

Note that \(\bar{w}\) is the complex velocity of N swimmers with periodic boundary conditions, not the complex conjugate of the potential for a single microswimmer w. Here, the function ρ(z) is the Weierstrass elliptic function, defined as \(\rho (z;L)=\frac{1}{{z}^{2}}+{\sum }_{k,l}(\frac{1}{{(z-{\Omega }_{kl})}^{2}}-\frac{1}{{\Omega }_{kl}^{2}})\), with Ωkl = kL + lL, \(k,l\in {\mathbb{Z}}-\{0\}\). The translational and rotational mobility of the swimmer are μ and ν. We fix μ = 0.9, U = 1, and σn = 1, and vary ν ∈ [−1, 1]61.

Next, let us discuss the physical significance of ν. In deriving Eq. (16), we approximate flagellated swimmers by a head-tail dumbbell swimmer model76. With this approximation, the rotational mobility is the difference between the mobility coefficients of the head and the tail ν = (μhead−μtail)/l, where l is the distance between the head and the tail. A positive ν corresponds to a microswimmer with strong flagellar activity that rotates into the local flow, whereas a negative ν corresponds to a microswimmer with weak flagellar activity that rotates opposite to the local flow.

The equations of motion (16) and (17) are integrated numerically using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta integrator. The adaptive timestep is chosen to ensure both relative error and absolute error are <1 × 10−9. The initial positions of the swimmers are chosen as an equally spaced mesh with random perturbations of half the mesh size. The initial orientations of the swimmers are chosen uniformly randomly from 0 to 2π. The collective behavior of this model strongly depends on the parameter ν. As illustrated in Fig. 7, negative ν leads to aggregation, while positive ν leads to swirling.

Here, our training data consists of 21 trajectories of 400 microswimmers, all starting from the same initial condition. In each trajectory, all microswimmers have the same value of ν (sample from [−1, 1]), and we evolve each trajectory forward to T = 100. Time is normalized so that a microswimmer without hydrodynamic interactions would move 1 unit length in 1 unit time. The domain size is chosen as 60 unit length. From the data evolved using an adaptive timestep, we sampled our trajectories on average every 1.0 × 10−2 time units with a standard deviation of 1.6 × 10−3.

From these trajectories, we shuffle and sample 2.5 × 105 graphs that we split into a 75/25 split for training and validation. Each GNN architecture consists of 5 Chebyshev convolution layers with 3 polynomials and a rectified linear unit activation after each layer. These convolutions map the graph inputs \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{4}\) (local) or \({{{\bf{n}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{5}\) (global) to graphs with hidden nodal values \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{i}^{(k)}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{64}\). We then sample the node associated with the central microswimmer \({{{\bf{h}}}}_{0}^{(5)}\), append ν to this vector, and pass this through three dense neural network layers to output \({\rm {d}}{{\bf{r}}}/{\rm {d}}t\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\). Each hidden layer of the dense neural network is in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{64}\), we used rectified linear units and a linear layer on the output. We trained these models for 150 epochs using an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 10−3 that dropped to 10−4 at 70 epochs and 10−5 at 140 epochs, and a batch size of 50. Following training, we tested the model on a new initial condition for each value of ν evolved forward for T = 500 (five times longer than the training data). At specific values of ν, shown in Fig. 9, we evolve trajectories forward to T = 1000 to test the stability of the models.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code is available on Code Ocean at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.5921825.v1.

References

Vicsek, T. & Zafeiris, A. Collective motion. Phys. Rep. 517, 71–140 (2012).

Kudrolli, A. Concentration dependent diffusion of self-propelled rods. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 088001 (2010).

Ibele, M., Mallouk, T. E. & Sen, A. Schooling behavior of light-powered autonomous micromotors in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3308–3312 (2009).

Wu, X.-L. & Libchaber, A. Particle diffusion in a quasi-two-dimensional bacterial bath. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3017–3020 (2000).

Ballerini, M. et al. Empirical investigation of starling flocks: a benchmark study in collective animal behaviour. Anim. Behav. 76, 201–215 (2008).

Moussaïd, M., Helbing, D. & Theraulaz, G. How simple rules determine pedestrian behavior and crowd disasters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6884 – 6888 (2011).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Chen, R. T., Rubanova, Y., Bettencourt, J. & Duvenaud, D. K. Neural ordinary differential equations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 31, 6572–6583 (2018).

Lukoševičius, M. & Jaeger, H. Reservoir computing approaches to recurrent neural network training. Comput. Sci. Rev. 3, 127–149 (2009).

Vlachas, P. et al. Backpropagation algorithms and reservoir computing in recurrent neural networks for the forecasting of complex spatiotemporal dynamics. Neural Netw. 126, 191–217 (2020).

Pathak, J., Hunt, B., Girvan, M., Lu, Z. & Ott, E. Model-free prediction of large spatiotemporally chaotic systems from data: a reservoir computing approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 24102 (2018).

Linot, A. J. & Graham, M. D. Deep learning to discover and predict dynamics on an inertial manifold. Phys. Rev. E 101, 062209 (2020).

Linot, A. J. & Graham, M. D. Data-driven reduced-order modeling of spatiotemporal chaos with neural ordinary differential equations. Chaos 32, 073110 (2022).

Borrelli, G., Guastoni, L., Eivazi, H., Schlatter, P. & Vinuesa, R. Predicting the temporal dynamics of turbulent channels through deep learning. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 96, 109010 (2022).

Linot, A. J. & Graham, M. D. Dynamics of a data-driven low-dimensional model of turbulent minimal Couette flow. J. Fluid Mech. 973, A42 (2023).

Maulik, R., Egele, R., Lusch, B. & Balaprakash, P. Recurrent neural network architecture search for geophysical emulation. In Proc. International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, SC ’20 (IEEE Press, 2020).

Arcomano, T. et al. A hybrid approach to atmospheric modeling that combines machine learning with a physics-based numerical model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002712 (2022).

Sanchez-Gonzalez, A. et al. Learning to simulate complex physics with graph networks. In Proc. 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (JMLR.org, 2020).

Bhattoo, R., Ranu, S. & Krishnan, N. M. A. Learning the dynamics of particle-based systems with Lagrangian graph neural networks. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 4, 015003 (2023).

Li, Z. & Farimani, A. B. Graph neural network-accelerated Lagrangian fluid simulation. Comput. Graph. 103, 201–211 (2022).

Choi, Y. & Kumar, K. Graph neural network-based surrogate model for granular flows. Comput. Geotech. 166, 106015 (2024).

Xiong, S., He, X., Tong, Y., Deng, Y. & Zhu, B. Neural vortex method: From finite Lagrangian particles to infinite dimensional Eulerian dynamics. Comput. Fluids 258, 105811 (2023).

Battaglia, P., Pascanu, R., Lai, M., Rezende, D. J. & Kavukcuoglu, K. Interaction networks for learning about objects, relations and physics. In Proc. 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4509–4517 (Curran Associates Inc., 2016).

Pfaff, T., Fortunato, M., Sanchez-Gonzalez, A. & Battaglia, P. W. Learning mesh-based simulation with graph networks. In 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3–7, 2021 (OpenReview.net, 2021).

Peng, J.-Z. et al. Grid adaptive reduced-order model of fluid flow based on graph convolutional neural network. Phys. Fluids 34, 087121 (2022).

Willis, A. P., Cvitanović, P. & Avila, M. Revealing the state space of turbulent pipe flow by symmetry reduction. J. Fluid Mech. 721, 514–540 (2013).

Thomas, N. et al. Tensor field networks: rotation- and translation-equivariant neural networks for 3D point clouds. Preprint at CoRR abs/1802.08219 http://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/journals/corr/corr1802.html#abs-1802-08219 (2018).

Fuchs, F. B., Worrall, D. E., Fischer, V. & Welling, M. SE(3)-transformers: 3D roto-translation equivariant attention networks. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (Curran Associates Inc., 2020).

Satorras, V. G., Hoogeboom, E. & Welling, M. E(n) equivariant graph neural networks. In Proc. 38th International Conference on Machine Learning Research, Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 9323–9332 (PMLR, 2021).

Brandstetter, J., Hesselink, R., van der Pol, E., Bekkers, E. J. & Welling, M. Geometric and physical quantities improve E(3) equivariant message passing. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Toshev, A. P., Galletti, G., Brandstetter, J., Adami, S. & Adams, N. A. E(3) equivariant graph neural networks for particle-based fluid mechanics. ICLR 2023 Workshop on Physics for Machine Learning https://openreview.net/forum?id=5ByoWjLmUa (2023).

Xu, M. et al. Equivariant Graph Neural Operator for Modeling 3D Dynamics https://openreview.net/forum?id=2UlfvGU6rL (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. SEGNO: generalizing equivariant graph neural networks with physical inductive biases. In Proc. of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (2024).

Liao, Y.-L. & Smidt, T. Equiformer: equivariant graph attention transformer for 3D atomistic graphs. In Proc. of the 11th International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Liao, Y.-L., Wood, B. M., Das, A. & Smidt, T. Equiformerv2: improved equivariant transformer for scaling to higher-degree representations. In Proc. of the 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (2024).

Lino, M., Fotiadis, S., Bharath, A. A. & Cantwell, C. D. Multi-scale rotation-equivariant graph neural networks for unsteady Eulerian fluid dynamics. Phys. Fluids 34, 087110 (2022).

Shankar, V., Barwey, S., Kolter, Z., Maulik, R. & Viswanathan, V. Importance of equivariant and invariant symmetries for fluid flow modeling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.05486 (2023).

Xiao, Z., Lin, H., Li, R., Chao, H. & Ding, S. Endowing deep 3D models with rotation invariance based on principal component analysis. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME) 1–6 (2019).

Li, F., Fujiwara, K., Okura, F. & Matsushita, Y. A closer look at rotation-invariant deep point cloud analysis. In 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 16198–16207 (2021).

Wang, R., Fang, F., Cui, J. & Zheng, W. Learning self-driven collective dynamics with graph networks. Sci. Rep. 12, 500 (2022).

Vicsek, T., Czirók, A., Ben-Jacob, E., Cohen, I. & Shochet, O. Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1226–1229 (1995).

Heras, F. J. H., Romero-Ferrero, F., Hinz, R. C. & de Polavieja, G. G. Deep attention networks reveal the rules of collective motion in zebrafish. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, 1–23 (2019).

Ha, S. & Jeong, H. Unraveling hidden interactions in complex systems with deep learning. Sci. Rep. 11, 12804 (2021).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2018).

Diestel, R. Graph Theory, Vol. 173 of Graduate Texts in Mathematics 5th edn (Springer, 2017).

Defferrard, M., Bresson, X. & Vandergheynst, P. Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering. In Proc. 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 3844–3852 (Curran Associates Inc., 2016).

Froehlich, S. & Cvitanović, P. Reduction of continuous symmetries of chaotic flows by the method of slices. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 17, 2074–2084 (2012). (Special Issue: Mathematical Structure of Fluids and Plasmas).

Budanur, N. B., Cvitanović, P., Davidchack, R. L. & Siminos, E. Reduction of SO(2) symmetry for spatially extended dynamical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 084102 (2015).

Cortelezzi, L. & Leonard, A. Point vortex model of the unsteady separated flow past a semi-infinite plate with transverse motion. Fluid Dyn. Res. 11, 263–295 (1993).

Chatelain, P., Duponcheel, M., Caprace, D.-G., Marichal, Y. & Winckelmans, G. Vortex particle-mesh simulations of vertical axis wind turbine flows: from the airfoil performance to the very far wake. Wind Energy Sci. 2, 317–328 (2017).

Samarbakhsh, S. & Kornev, N. Simulation of a free circular jet using the vortex particle intensified les (vπles). Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 80, 108489 (2019).

Eldredge, J. D. Examples of Two-Dimensional Flow Modeling 341–367 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Mimeau, C. & Mortazavi, I. A review of vortex methods and their applications: from creation to recent advances. Fluids 6, (2021) https://www.mdpi.com/2311-5521/6/2/68.

Saffman, P. G. Singular Distributions of Vorticity, 20–45. Cambridge Monographs on Mechanics (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Nair, A. G. & Taira, K. Network-theoretic approach to sparsified discrete vortex dynamics. J. Fluid Mech. 768, 549–571 (2015).

Gopalakrishnan Meena, M., Nair, A. G. & Taira, K. Network community-based model reduction for vortical flows. Phys. Rev. E 97, 063103 (2018).

Brady, J. F. & Bossis, G. et al. Stokesian dynamics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 20, 111–157 (1988).

Elfring, G. J. & Brady, J. F. Active Stokesian dynamics. J. Fluid Mech. 952, A19 (2022).

Oza, A. U., Ristroph, L. & Shelley, M. J. Lattices of hydrodynamically interacting flapping swimmers. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041024 (2019).

Heydari, S., Hang, H. & Kanso, E. Mapping spatial patterns to energetic benefits in groups of flow-coupled swimmers. Elife 13, RP96129 (2024).

Tsang, A. C. H. & Kanso, E. Flagella-induced transitions in the collective behavior of confined microswimmers. Phys. Rev. E 90, 021001 (2014).

Tsang, A. C. H. & Kanso, E. Density shock waves in confined microswimmers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 048101 (2016).

Takagi, D., Palacci, J., Braunschweig, A. B., Shelley, M. J. & Zhang, J. Hydrodynamic capture of microswimmers into sphere-bound orbits. Soft Matter 10, 1784–1789 (2014).

Couzin, I. D. & Krause, J. et al. Self-organization and collective behavior in vertebrates. Adv. Study Behav. 32, 10–1016 (2003).

Filella, A., Nadal, F., Sire, C., Kanso, E. & Eloy, C. Model of collective fish behavior with hydrodynamic interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 198101 (2018).

Qi, K., Westphal, E., Gompper, G. & Winkler, R. G. Emergence of active turbulence in microswimmer suspensions due to active hydrodynamic stress and volume exclusion. Commun. Phys. 5, 49 (2022).

Rubner, Y., Tomasi, C. & Guibas, L. A metric for distributions with applications to image databases. In Sixth International Conference on Computer Vision (IEEE Cat. No. 98CH36271), 59–66 (1998).

Couzin, I. D., Krause, J., Franks, N. R. & Levin, S. A. Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move. Nature 433, 513–516 (2005).

Huang, C., Ling, F. & Kanso, E. Collective phase transitions in confined fish schools. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2406293121 (2024).

Hang, H., Huang, C., Barnett, A. & Kanso, E. Self-reorganization and information transfer in massive schools of fish. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.05822 (2025).

Greengard, L. & Rokhlin, V. A fast algorithm for particle simulations. J. Comput. Phys. 73, 325–348 (1987).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2017).

Bro, R., Acar, E. & Kolda, T. G. Resolving the sign ambiguity in the singular value decomposition. J. Chemometr. 22, 135–140 (2008).

Tao, M. Explicit symplectic approximation of nonseparable hamiltonians: algorithm and long time performance. Phys. Rev. E 94, 043303 (2016).

Fey, M. & Lenssen, J. E. Fast graph representation learning with PyTorch Geometric. In ICLR Workshop on Representation Learning on Graphs and Manifolds (2019).

Brotto, T., Caussin, J.-B., Lauga, E. & Bartolo, D. Hydrodynamics of confined active fluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 038101 (2013).

Saintillan, D. & Shelley, M. J. Instabilities, pattern formation, and mixing in active suspensions. Phys. Fluids 20, 123304 (2008).

Kanso, E. & Tsang, A. C. H. Pursuit and synchronization in hydrodynamic dipoles. J. Nonlinear Sci. 25, 1141–1152 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jeff Eldredge for insightful discussions. This work was supported by the US Department of Defense Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship (grant no. N00014-22-1-2798).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and developed the GNN code and the point vortex code. A.J.L. and K.T. conceived the GNN method. H.H. and E.K. developed the microswimmers code, and H.H. ran the microswimmers code. A.J.L., H.H., E.K., and K.T. contributed to the discussion and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another journal. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Physics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Linot, A.J., Hang, H., Kanso, E. et al. Hierarchical equivariant graph neural networks for forecasting collective motion in vortex clusters and microswimmers. Commun Phys 8, 515 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02417-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published: