Abstract

Two-dimensional non-Hermitian photonic lattices with asymmetric couplings offer rich possibilities for controlling wave localization, through the emergence of the non-Hermitian skin effect at lattice corners or sides. Yet, how optical nonlinearity modifies these boundary-localization characteristics remains largely unexplored. Here we show that in a two-dimensional Hatano-Nelson lattice with Kerr nonlinearity, the interplay between self-trapping and directional propagation leads to position-dependent amplitude thresholds. Single-site excitations having above a critical amplitude become confined to their initial position, with lower thresholds near the position where the linear eigenmodes are localized and higher thresholds within the lattice’s bulk. Additionally, we study the differences of this dynamical interplay, for wider initial excitations, between the focusing and defocusing Kerr-nonlinearity regimes. Lastly, we identify skin soliton solutions in a variety of two-dimensional lattice geometries featuring coupling asymmetry. This work paves the way for future investigations regarding transport and soliton formation in higher-dimensional nonlinear non-Hermitian lattices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, photonics has emerged as a versatile platform for exploring non-Hermitian physics, enabling the precise engineering of gain and loss distributions in optical systems1. Unlike quantum or condensed-matter settings, where the experimental control of non-Hermiticity remains challenging, photonic systems offer a practical and accessible setup2. This has fueled rapid progress in the study of non-Hermitian wave dynamics and the demonstration of distinct phenomena, such as exceptional points3,4, parity-time \(({{{\mathcal{PT}}}})\) symmetry5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, and the Non-Hermitian Skin Effect (NHSE)15,16,17,18, among others19,20,21,22,23, all of which are now of crucial importance and relevance to the fields of topological and integrated photonics.

Among the plethora of systems studied in non-Hermitian physics, the Hatano–Nelson (HN) model offers a prototypical lattice where non-Hermiticity is realized through asymmetric nearest-neighbor couplings24,25. An intriguing feature of this model is the NHSE, i.e., the exponential localization of eigenmodes at one edge of the lattice under open boundary conditions (OBC). Initially proposed to describe localization-delocalization transitions in solid-state systems, the HN model remained for years a purely theoretical concept in mathematical physics26. However, recent advances in optics have enabled its experimental realization27,28, opening new possibilities for practical applications in photonic cavities and lasers29,30,31,32,33 as well as ultracold atoms34. The extension of the NHSE to two-dimensional (2D) lattices reveals even richer localization features that depend on the direction and strength of coupling asymmetry35,36,37,38,39. When the coupling asymmetry is along a single direction, the NHSE manifests as side-localized modes; however, when asymmetric couplings are present in both directions, the eigenmodes exhibit significant spatial asymmetry as they become localized at specific lattice corners37. However, most studies related to higher-dimensional lattices have focused on the topological nature of the NHSE, exploring bulk-boundary correspondence and redefining topological invariants40,41,42,43,44,45,46, while much less attention has been devoted to transport features38.

On the other hand, nonlinearity, an inherent property of optical systems, gives rise to a wide range of intriguing phenomena, including self-trapping, modulational instability, and soliton formation47. When combined with non-Hermiticity, the nonlinear phenomena are significantly modified, leading to distinct effects and the emergence of localized states48,49,50. In one-dimensional (1D) HN systems, nonlinearity has primarily been explored in the context of topological edge states and single-mode lasing51,52,53,54. Recent studies have also examined the effect of Kerr nonlinearity in 1D HN lattices, focusing on soliton formation55,56,57,58,59,60. Notably, it was recently shown, both theoretically and experimentally, that the interplay between Kerr nonlinearity and asymmetric couplings can lead to the formation of nonlinear skin solitons55,56,61, characterized by position-dependent power thresholds and highly asymmetric spatial profiles. Nevertheless, the interplay of nonlinearity and non-Hermiticity in higher-dimensional settings, such as 2D HN lattices, remains largely unexplored.

In this work, we study the dynamics in 2D HN lattices with Kerr nonlinearity, focusing on the antagonism between self-trapping and propagation due to asymmetric couplings. In the extensively studied Hermitian case, where the evolution is described by the discrete nonlinear Schrödinger equation (DNLSE), self-trapping of a localized excitation to its initial position occurs when the excitation’s amplitude exceeds a critical threshold, thus suppressing discrete diffraction. This phenomenon has been widely explored in both 1D and 2D systems within the framework of lattice solitons62,63,64,65,66,67,68. In particular, here we examine how the degree of non-Hermiticity and the location of the initial single-site excitation influence the amplitude thresholds for self-trapping. Our study reveals that these thresholds are highly position-dependent, with relatively low thresholds near the lattice corners toward which the couplings are stronger, and significantly higher thresholds, or even impossible self-trapping, in the bulk of the system under strong non-Hermiticity. Furthermore, we consider wider Gaussian initial excitations and investigate how the interplay between Kerr nonlinearity and non-Hermiticity depends on whether the nonlinearity is focusing or defocusing. Additionally, we identify 2D skin soliton solutions and characterize their properties through their corresponding power-eigenvalue diagrams. Our results show that these skin solitons exhibit spatial asymmetry, and their power thresholds increase monotonically as the coupling asymmetry becomes stronger. Finally, we report the existence of skin solitons in a variety of more complex 2D nonlinear non-Hermitian lattices, beyond the 2D HN lattice.

Results

Two-dimensional nonlinear Hatano–Nelson lattice

Coupled-mode equations and conservation laws

We begin our study with a generalized two-dimensional nonlinear Hatano–Nelson (2D NLHN) lattice consisting of N × N coupled waveguides, indexed by (nx, ny) ∈ {1, 2, …, N}, and characterized by asymmetric couplings. The discrete paraxial equation describing the wave evolution in this lattice, in normalized units, is

where \({h}_{x},{h}_{y}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{+}\) are the non-Hermiticity parameters, in the horizontal (nx) and vertical (ny) directions, respectively. The quantity \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)\) denotes the complex amplitude of the electric field’s envelope at site (nx, ny) at propagation distance z. For simplicity, we will refer to this quantity as the wavefunction. The parameter g determines whether the lattice is linear (g = 0) or exhibits Kerr-type nonlinearity (∣g∣ = 1). Throughout this work, we consistently consider OBC in both lattice directions, i.e., \({\psi }_{0,{n}_{y}}={\psi }_{N+1,{n}_{y}}={\psi }_{{n}_{x},0}={\psi }_{{n}_{x},N+1}=0\).

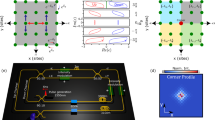

The geometry of a 2D HN lattice, schematically depicted in Fig. 1, implies the existence of four geometrically distinct corners. These corners are labeled as follows: corner (A), located in the direction of stronger coupling along both nx and ny, where the linear skin modes are localized; corner (C), located in the direction of weaker coupling along both nx and ny; and corners (Bx)/(By), located in the directions of stronger coupling along nx/ny but weaker coupling along ny/nx. In the special case where hx = hy, corners Bx and By are equivalent by symmetry, and we refer to them in this particular case as corners (B). We consistently follow this notation throughout this work.

The arrows represent the asymmetric couplings: \({e}^{{h}_{x}}\) and \({e}^{-{h}_{x}}\) along the nx-direction, and \({e}^{{h}_{y}}\) and \({e}^{-{h}_{y}}\) along the ny-direction. The figure identifies the four geometrically distinct corners of the lattice, labeled as (A), (Bx), (By), and (C). The spatial distribution of four indicative linear eigenmodes, for a case with hx = hy, is included as an inset.

Although the 2D NLHN lattice is non-Hermitian and thus corresponds to non-conservative dynamics, it can be mapped via the imaginary gauge transformation \({\alpha }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\equiv {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}{e}^{-({h}_{x}{n}_{x}+{h}_{y}{n}_{y})}\), to a Hermitian tight-binding model, which, in the nonlinear case (∣g∣ = 1), is characterized by site-dependent nonlinearity. As we will see, this allows us to derive conservation laws for the system under discussion.

Specifically, the evolution of the complex amplitude \({\alpha }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)\) in such a lattice is governed by the discrete nonlinear Schrödinger (DNLSE)-type equation:

As detailed in the Supplementary Note 1, the quantity

which represents the optical power and is known to be conserved in the standard DNLSE, remains conserved even under this particular site-dependent nonlinearity. This contrasts with the HN system of Eq. (1), in which the optical power \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{HN}}}}}(z)={\sum }_{{n}_{x} = 1}^{N}{\sum }_{{n}_{y} = 1}^{N}| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z){| }^{2}\) is not conserved along propagation. Nonetheless, the connection between the systems described by Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) through the transformation \({\alpha }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\equiv {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}{e}^{-({h}_{x}{n}_{x}+{h}_{y}{n}_{y})},\) along with the power conservation of the latter system, implies that in the 2D NLHN lattice [Eq. (1)], the quantity

which we refer to as the pseudopower, is constant during the dynamics. Moreover, another invariant quantity of the system described by Eq.(2) is the Hamiltonian,

as shown in the Supplementary Note 1. Consequently, a second conserved quantity for the 2D NLHN lattice is the pseudohamiltonian

Within the context of our discussion, the existence of these two conservation laws provides a direct means of validating the accuracy of our numerical results, which will be presented in the following subsections. This is very important, given the high degree of non-normality and numerical instability due to coupling asymmetry, which are inherent in HN lattices69.

Impact of nonlinearity on propagation dynamics

In this subsection, we investigate how Kerr nonlinearity affects the dynamics in the 2D NLHN lattice. Unless stated otherwise, in the numerical results presented in this study, we consider a lattice consisting of N × N = 25 × 25 waveguides and equal non-Hermiticity parameters for the two directions, i.e., hx = hy ≡ h. Complementary results for the case of hx ≠ 0 and hy = 0 are discussed in the Supplementary Note 2. In particular, we will consider the scenario of a localized, single-site initial excitation. As analytically proven in the Supplementary Note 3, for such an initial condition, the dynamics of the magnitude of the wavefunction \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)|\) remain identical regardless of whether the Kerr nonlinearity is focusing (g = 1) or defocusing (g = −1). Relevant examples of propagation dynamics with initial excitations occupying multiple channels are discussed in a separate subsequent section.

First, as shown in the top row of Fig. 2, in the absence of Kerr nonlinearity (g = 0), the NHSE dictates the dynamics. Specifically, for a non-Hermiticity parameter h = 0.2 and an initial condition \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=0)=A \, {\delta }_{{n}_{x},13}{\delta }_{{n}_{y},13}\), where A is the excitation amplitude, the wavefunction propagates toward the corner (A) of the lattice, as physically expected. As clearly demonstrated in Fig. 2d, while the wavefunction shifts toward the corner (A), the total optical power \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{HN}}}}}=\mathop{\sum }_{{n}_{x} = 1}^{N}\mathop{\sum }_{{n}_{y} = 1}^{N}| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z){| }^{2}\) increases, consistent with the conservation of the pseudopower \(\tilde{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}=\mathop{\sum }_{{n}_{x} = 1}^{N}\mathop{\sum }_{{n}_{y} = 1}^{N}| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z){| }^{2}{e}^{-2({h}_{x}{n}_{x}+{h}_{y}{n}_{y})}\), since the wavefunction is on average distributed on lattice sites with larger nx, ny. Additionally, the optical intensity at the initially excited site, ∣ψ13,13∣2, vanishes for z > 1. Of course, in the linear regime, diffraction is independent of the excitation amplitude A, unlike the nonlinear case (∣g∣ = 1), where its value plays a crucial role. In particular, as illustrated in the bottom row of Fig. 2, for the same initial condition, with amplitude A = 4, the wavefunction remains self-trapped at the initial-excitation site for short propagation distances (z < 2). For z ≳ 2, it splits into two distinct parts: one remains localized at the initial position, while the other propagates toward the corner (A). This occurs because, in the Kerr-nonlinear case, the optical intensity ∣ψ13,13∣2 exhibits oscillations for z < 2 [Fig. 2h] and eventually stabilizes at a slightly reduced value compared to its initial one. The separated part of optical power propagates toward the preferential corner and becomes amplified due to the conservation of pseudopower \(\tilde{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}\), as in the linear regime. This process results in wavefunction splitting: part of the initial power, slightly less than the original, remains localized near the initial-excitation site, while the rest is amplified as it propagates toward the preferential corner. This behavior clearly indicates an antagonism between self-trapping caused by nonlinearity and the NHSE, induced by the asymmetric couplings.

For all panels, the non-Hermiticity parameter is h = 0.2 and the initial condition is \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=0)=A\,{\delta }_{{n}_{x},13}{\delta }_{{n}_{y},13}\). a–c Normalized amplitude \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)|\) (color map) for the linear case at propagation distances z = 1, z = 3.5, and z = 6, respectively. e–g Normalized amplitude \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)|\) (color map) for the nonlinear case with input amplitude A = 4 at the same propagation distances. In all color maps, the wavefunctions are normalized such that their maximum amplitude equals unity. d, h Evolution of the total optical power \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{HN}}}}}\) (red) and the on-site intensity at the initially excited site ∣ψ13,13∣2 (blue) for the linear and nonlinear cases, respectively; insets provide zoom-in views of the curves.

In order to better understand this interplay, we study the evolution of the wavefunction’s mean positions and uncertainties along the nx and ny directions. These are defined by the following general expressions:

where

In the above expressions, the notation nx/y denotes either nx or ny.

Our corresponding results, for the same configuration as in Fig. 2, are presented in Fig. 3. In particular, in Fig. 3a, we show that, in the linear regime, the wavefunction’s mean positions, 〈nx〉 = 〈ny〉, increase almost linearly with the propagation distance z, after an initial acceleration45, and finally the wavepacket reaches the corner (A). On the contrary, when Kerr nonlinearity is introduced, propagation is significantly hindered. Specifically, as the excitation amplitude A increases, the mean positions 〈nx〉 = 〈ny〉 have a progressively delayed increase and their value never reaches the corresponding value for the linear regime, indicating a higher tendency for self-trapping. Moreover, the nonlinear regime is characterized by increased position uncertainties Δnx = Δny, as depicted in Fig. 3b. This increase reflects the previously discussed splitting of the wavefunction into two parts (bottom row of Fig. 2). Such behavior emerges due to the interplay between Kerr nonlinearity and the NHSE, which will be studied more systematically in the following section.

The non-Hermiticity parameter is h = 0.2, and the initial condition is \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=0)=A\,{\delta }_{{n}_{x},13}{\delta }_{{n}_{y},13}\). a Mean positions 〈nx〉 and 〈ny〉. b Position uncertainties Δnx and Δny for the linear case (gray line) and for nonlinear cases with excitation amplitudes A = 1 (red), A = 4 (blue), and A = 6 (green).

Antagonism between skin effect and self-trapping

As it was discussed in the previous section, Kerr-nonlinearity and the skin effect have opposite tendencies regarding the localization of an initially localized wavepacket, which leads to a dynamic interplay. Therefore, our goal in this section is to demonstrate, through pertinent examples, that the dynamics in a 2D NLHN lattice, as described by Eq. (1) with ∣g∣ = 1, depend highly on the position of the initial single-site excitation, due to the system’s non-Hermiticity. Specifically, we will consider the single-site initial condition:

for different cases of \({n}_{{x}_{0}}\) and \({n}_{{y}_{0}}\) and for various values of the excitation amplitude A.

First, we focus on the case of initial excitation at the center of the lattice, i.e., \({n}_{{x}_{0}}={n}_{{y}_{0}}=13\) for Hermitian and non-Hermitian lattices and our results are shown in Fig. 4. In particular, in Fig. 4a for the Hermitian case (h = 0), the wavefunction at a fixed propagation distance z = 5, \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=5)|\), is extended for low values of the excitation amplitude A. When A exceeds a particular value, the effect of Kerr nonlinearity becomes significant, leading to self-trapping of the wavefunction, almost entirely, at the position of initial excitation. The transition between delocalization and self-trapping can be quantified by the increase in the output (i.e., at z = 5) value of the inverse participation ratio (IPR). This metric is widely used to indicate localization and, for a given 2D wavefunction \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\), is defined as:

ranging from 1/N2 for a fully extended state \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\propto 1/N\), to 1 for a state localized to a single site, \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\propto {\delta }_{{n}_{x},{m}_{x}}{\delta }_{{n}_{y},{m}_{y}}\). This behavior changes dramatically when coupling asymmetry is introduced through non-zero values of h. For the case of h = 0.2, as shown in Fig. 4b, it is evident that diffraction dominates over self-trapping for a much higher range of excitation amplitudes A, compared to the Hermitian lattice.

a A Hermitian lattice (h = 0) and b a non-Hermitian lattice with non-Hermiticity parameter h = 0.2, for single-site excitation at the center, i.e., \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=0)=A\,{\delta }_{{n}_{x},13}{\delta }_{{n}_{y},13}\), where A is the excitation amplitude. The normalized amplitudes \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=5)|\) (color map) are plotted for pertinent values of A (left panels), and the inverse participation ratio (IPR) for z = 5 is shown as a function of A (right panels). Red dots correspond to the values of A used in the left panels. In all color maps, the wavefunctions are normalized such that their maximum amplitude equals unity.

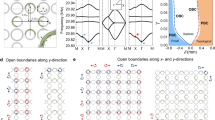

Our results regarding higher values of the non-Hermiticity parameter h, and different locations of the single-channel excitation are presented in Fig. 5. More specifically, for h = 0.4, Kerr nonlinearity can no longer induce self-trapping up to z = 5 for single-site excitation at the center of the lattice, as shown in Fig. 5a. Instead, the NHSE dominates, forcing the wavefunction to delocalize toward the corner (A) of the lattice. This behavior persists even as the excitation amplitude A increases, within a reasonable range of physically relevant values, as indicated by the consistently low values of the IPR(z = 5). Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 5b, the competition between nonlinearity and coupling asymmetry leads to different propagation characteristics when the initial excitation is near the corner (A) of the lattice, i.e., \({n}_{{x}_{0}}={n}_{{y}_{0}}=23\). Since the linear eigenmodes of the system are localized near this location, self-trapping to the initial excitation site becomes possible above an amplitude threshold, contrary to the case of Fig. 5a. It should be noted that the pronounced peaks of IPR (z = 5) for A ≲ 4 correspond to cases, where, after the wavefunction gets delocalized from the site of initial excitation due to coupling asymmetry, it becomes trapped in lattice sites closer to the corner (A) (\({n}_{{x}_{0}}={n}_{{y}_{0}}=25\)) of the lattice, for finite propagation intervals. At this point, we also consider the case of an initial excitation near the corner (B), i.e., at \({n}_{{x}_{0}}=23\) and \({n}_{{y}_{0}}=3\). There, delocalization of the wavefunction is promoted only along the spatial dimension ny, since the wavefunction is already on the side of the lattice towards which the couplings along the nx direction are stronger. As shown in Fig. 5c, although self-trapping is possible, it requires considerably higher excitation amplitude. This represents an intermediate case between those discussed in Fig. 5a, b.

For all panels, the non-Hermiticity parameter is h = 0.4. a Normalized amplitudes \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=5)|\) (color map) for excitation amplitudes A = 2, 8, 14, under single-site excitation at the center, \({n}_{{x}_{0}}={n}_{{y}_{0}}=13\); in the bottom panel, the inverse participation ratio (IPR) for z = 5 is shown as a function of A. Red dots indicate the values of IPR for the aforementioned values of A. b Similar to (a), with single-site excitation near the corner (A), \({n}_{{x}_{0}}={n}_{{y}_{0}}=23\), and A = 1.1, 2.6, 4.1. c Similar to (a), with single-site excitation near corner (B), \({n}_{{x}_{0}}=23\) and \({n}_{{y}_{0}}=3\), and A = 2, 8, 14. In all color maps, the wavefunctions are normalized such that their maximum amplitude equals unity.

To conclude, the aforementioned examples highlight the intricate interplay between Kerr nonlinearity, which induces self-trapping of an initially localized wavepacket, and non-Hermiticity, which promotes wavefunction delocalization. Up to this point, it is clear that the antagonism between those two effects depends on three different factors: the non-Hermiticity parameter h, the location of the initial excitation \(({n}_{{x}_{0}},{n}_{{y}_{0}})\), and its amplitude A. A natural and physically relevant question arising from our discussion is how to quantify such amplitude thresholds required to induce self-trapping at a single lattice site, for a given non-Hermiticity parameter h.

Amplitude thresholds for self-trapping

In order to investigate this systematically, we study the dynamics in a 2D NLHN lattice, for single-site excitation at each site \(({n}_{{x}_{0}},{n}_{{y}_{0}})\), gradually increasing the excitation amplitude A. For each value of A, we compute the output IPR (z = 5) of the wavefunction, \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=5)|\), similarly to the previous subsection. We define the threshold Ath for self-trapping as the lowest value of A for which IPR (z = 5) > 0.8. Such a criterion is meaningful as it signifies near-perfect self-trapping at a single site, and although the threshold choice is arbitrary, it does not compromise the generality of our results since any alternative criterion would lead to similar conclusions. Furthermore, to ensure that the high value of IPR (z = 5) arises from self-trapping to the site of initial excitation rather than localization to other sites toward the corner (A) of the lattice, we impose an additional constraint: the shift of the mean position of the wavefunction at z = 5, \(r\equiv \sqrt{{(\langle {n}_{x}\rangle -{n}_{{x}_{0}})}^{2}+{(\langle {n}_{y}\rangle -{n}_{{y}_{0}})}^{2}}\), must satisfy r < 1. For reference, we mention that in the Hermitian case (h = 0), the two aforementioned constraints yield an amplitude threshold of A~3.

At first, we follow the previously described procedure for a lattice with h = 0.2, and present our results in Fig. 6a as a comprehensive map. As evident from this figure, self-trapping occurs at relatively low excitation amplitudes, around Ath ~ 3, for lattice sites adjacent to the corner (A). However, the threshold increases to approximately Ath ~ 4 for lattice sites near corners (B) and rises dramatically to Ath ~ 9.5 for the bulk of the lattice. This dependence of Ath on the excitation site stems from the position-dependent tendency for delocalization in the 2D HN lattice. Initial single-channel excitations at sites adjacent to the corner (A), where couplings are stronger in both transverse directions, exhibit minimal delocalization even in the linear regime and therefore require the lowest amplitudes for self-trapping when nonlinearity is present. Excitations at sites near the corner (B), where couplings are stronger along only one direction, exhibit important diffraction only along one direction and thus require higher thresholds, while excitations at bulk sites or near the corner (C), which rapidly delocalize in both directions, require even larger amplitudes for self-trapping.

When the non-Hermiticity parameter is increased to h = 0.4 [Fig. 6b], the previously observed asymmetry in amplitude thresholds becomes significantly more profound. While sites near corner (A) still require an excitation amplitude of Ath ~ 3 for self-trapping, the threshold exceeds Ath = 10 for sites near corner (B) and becomes impossible for the rest of the lattice. For this latter observation, we examined excitation amplitudes up to A = 20. At this point, we note that when asymmetric couplings only occur along one transverse direction, i.e., hx = 0.4, hy = 0, then self-trapping becomes feasible for all lattice sites, as presented in the Supplementary Note 2.

In conclusion, in this section, we have examined how Kerr nonlinearity induces self-trapping in a single site when the excitation amplitude A exceeds a specific threshold, depending on the location of the initially localized excitation and the degree of non-Hermiticity, in a 2D NLHN lattice.

Self-focusing and defocusing dynamics

Up to this point, we have examined the propagation dynamics in 2D NLHN lattices specifically for an initially localized single-channel excitation, uncovering a rich competition between self-trapping and the lattice’s non-Hermiticity. As previously mentioned, for this type of excitation, the amplitude dynamics remain identical irrespective of the nature (focusing or defocusing) of the Kerr nonlinearity. Therefore, it is intriguing to investigate the dynamics under wider excitations to qualitatively explore the differences arising from the interplay of coupling asymmetry and Kerr nonlinearity, between the focusing (g = 1) and defocusing (g = −1) cases.

Specifically, we consider an initial Gaussian excitation centered at the lattice site (xc, yc):

where A is the amplitude and w is the Gaussian width parameter. In Fig. 7, we present an illustrative comparison between the propagation dynamics in the focusing (top row) and defocusing (bottom row) Kerr-nonlinear regimes for a non-Hermiticity parameter h = 0.2. The initial excitation parameters are set to w = 2, (xc, yc) = (13, 13), with the amplitude A chosen to yield a total optical power of \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{HN}}}}}(z=0)=20\) [Fig. 7a, d]. Additionally, in Fig. 8, we plot the evolution of the wavefunction’s mean positions, 〈nx〉 = 〈ny〉, and their uncertainties, Δnx = Δny, comparing the focusing and defocusing nonlinear-regime propagation dynamics, with the corresponding linear case.

For all panels, the non-Hermiticity parameter is h = 0.2 and the initial condition is \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=0)=A{e}^{-[{({n}_{x}-{x}_{c})}^{2}+{({n}_{y}-{y}_{c})}^{2}]}/2{w}^{2}\), with xc = yc = 13, w = 2, where the excitation amplitude A is such that the optical power is \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{HN}}}}}(z=0)=20\). Normalized amplitude \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)|\) (color map) for the focusing case at propagation distances a z = 0, b z = 1.5, c z = 3, and d z = 6. e–h Normalized amplitude \(| {\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)|\) for the defocusing case at the same propagation distances. In all color maps, the wavefunctions are normalized such that their maximum amplitude equals unity.

The non-Hermiticity parameter is h = 0.2, and the initial condition is \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z=0)=A{e}^{-[{({n}_{x}-{x}_{c})}^{2}+{({n}_{y}-{y}_{c})}^{2}]}/2{w}^{2}\), with xc = yc = 13, w = 2, and A such that \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}_{{{{\rm{HN}}}}}(z=0)=20\). a Mean positions 〈nx〉 and 〈ny〉 and b position uncertainties Δnx and Δny for the linear case (gray lines), focusing Kerr-nonlinear (red lines), and defocusing Kerr-nonlinear cases (blue lines).

In the focusing nonlinear case, the wavefunction initially undergoes self-focusing toward the lattice center, as shown in Fig. 7b, also evidenced by the decrease in the position uncertainties [Fig. 8b]. Subsequently, however, the wavefunction begins to spread [Fig. 7c], and the mean positions begin to rise, though remaining consistently lower than in the linear scenario [Fig. 8a]. Notably, after a certain propagation distance, the wavefunction separates into two distinct parts, similarly to what was discussed in the first section for single-site excitations: one fraction remains localized near the initial excitation location, while another part propagates toward corner (A) of the lattice [Fig. 7d], as reflected in the increased position uncertainties for z ≳ 5, compared to the linear case [Fig. 8b].

In contrast to the single-site excitation scenario, the Gaussian initial condition [Eq. (12)] exhibits significantly different dynamics under defocusing Kerr nonlinearity. As illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8, the wavefunction shifts away from its initial position markedly faster compared to the linear or focusing nonlinear cases, propagating preferentially toward the corner (A) of the lattice, as reflected in the increased mean positions. Importantly, it simultaneously exhibits stronger diffraction compared to the linear regime, as indicated by its higher position uncertainties. Thus, although the wavefunction mean position shifts toward the lattice’s preferred corner, the presence of coupling asymmetry does not prevent a significant fraction of the wavefunction from spreading broadly across the lattice.

Here, we note that the dynamics remain qualitatively similar to what was described above for Gaussian excitations centered at different (xc, yc) across the lattice. It is also noteworthy that, as w decreases, the differences between the focusing and defocusing cases become less pronounced, and for w ≲ 0.3, the propagation dynamics of the two regimes are almost indistinguishable, converging to the single-site excitation scenario.

Two-dimensional skin solitons

In previous sections, we systematically discussed how Kerr nonlinearity induces self-trapping of the wavefunction to its initial position, for single-channel excitation, when the excitation amplitude A exceeds a threshold, which depends on the location of the initial excitation and the degree of coupling asymmetry. This analysis naturally leads to the question of whether this lattice also supports soliton solutions, analogous to the skin solitons recently predicted theoretically55 and observed experimentally56 in 1D NLHN systems. In this section, we identify stationary soliton solutions within the 2D NLHN lattice, particularly for focusing Kerr-nonlinearity (g = 1). Specifically, we consider solutions of Eq. (1) of the form \({\psi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)={\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}{e}^{i\mu z}\), where by \({\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\) and μ we denote the soliton profile and the soliton eigenvalue, respectively. Substituting this ansatz into Eq. (1) results in a system of nonlinear algebraic equations,

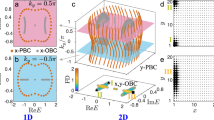

Using iterative numerical techniques63,64,65,70, we obtain lattice soliton solutions, and thus we can relate their corresponding power (\(P\equiv \mathop{\sum }_{{n}_{x} = 1}^{N}\mathop{\sum }_{{n}_{y} = 1}^{N}| {\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}{| }^{2}\)) to the soliton eigenvalue (μ). Such power-eigenvalue diagrams are shown in Fig. 9 for various values of h. Specifically, we analyze solitons positioned near the corner (A) [Fig. 9a] and near the center of the lattice [Fig. 9b]. In both cases, it is evident that the solitons exhibit power thresholds. We have also identified soliton solutions located near corners (B) and (C) of the lattice, having power-eigenvalue diagrams very similar to the solitons located near the center of the lattice. For a given value of h, the power thresholds for solitons near corners (B) and (C) differ by less than 10−2 from those of the solitons near the center. However, the difference of the eigenvalues at these thresholds is higher, reflecting variations in the spatial distributions of the soliton profiles.

a Power (P)-eigenvalue (μ) diagrams for solitons near the corner (A) and b in the bulk of the lattice. Colored lines correspond to different values of the non-Hermiticity parameter h. c Power thresholds Pth as a function of h, for solitons near the corner (A) (purple line) and in the bulk of the lattice (green line). Black, blue, and red dots correspond to the dots of (a, b), indicating the value of h.

Additionally, for both soliton locations, we investigate the dependence of the power thresholds Pth on the non-Hermiticity parameter h. As illustrated in Fig. 9c, the power thresholds for solitons located near the corner (A) and near the center of the lattice increase monotonically with h. Specifically, we confirm that this dependence is well approximated by a parabolic form, Pth ≈ ah2 + bh + c. In Fig. 10a, we present a pertinent example of a soliton profile \(| {\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}|\) located near the corner (A), for h = 0.4. In this case, as well as for solitons at other locations in the lattice, the solutions exhibit spatial asymmetry toward corner (A) due to the asymmetric couplings. As expected, we further verified that the degree of asymmetry of the soliton solutions increases with h. Also, we investigated the stability of the soliton solutions by computing the deviation parameter defined as \(\delta {\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)\equiv \max \left(\left\vert \right.| {\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(z)| -| {\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}(0)| \left\vert \right.\right)\), at propagation distance z = 25. This parameter quantifies the deviation of the evolved soliton profile from its initial distribution. For a non-Hermiticity parameter h = 0.2, solitons at all lattice locations remain stable, exhibiting very small deviations, with δϕ ~ 10−7. However, at a higher non-Hermiticity value of \(h = 0.4\), soliton stability becomes strongly position-dependent: deviations are minimal near corner (A) and increase steadily as the soliton is shifted across the lattice, reaching their maximum near corner (C) (\(\sim\!10^{-3}\)).

a 2D Hatano–Nelson lattice, with N × N = 25 × 25 sites and non-Hermiticity parameter h = 0.4. b–d Alternative lattices with asymmetric couplings, composed of Hatano–Nelson sublattices with different coupling asymmetry direction. In all left panels, the directions of strong (weak) couplings are indicated by thick (thin) colored arrows. Each sublattice is depicted with a different background color for visualization clarity, while the opacity of each color increases in the regions towards which the couplings are stronger. At all boundaries between sublattices, the intra-sublattice couplings are reciprocal and set to c = 1 (gray arrows). The right panels show representative soliton profiles \(\left\vert \right.{\phi }_{{n}_{x},{n}_{y}}\left\vert \right.\) for the corresponding geometries, calculated for lattices with N × N = 24 × 24 sites composed of 2D Hatano–Nelson sublattices with h = 0.4. In each right panel, an inset displays a cross-section along the red dashed line. In all color maps, the soliton profiles are normalized such that their maximum amplitude equals unity.

Finally, we examined the formation of skin solitons in other 2D lattices with asymmetric couplings under focusing Kerr nonlinearity, beyond the prototypical 2D NLHN lattice. As shown in Fig. 10, skin solitons also exist in alternative non-Hermitian lattices composed of properly engineered sublattices, where the global coupling asymmetry is directed, for example, toward a line, the lattice center, or other targeted regions33. These geometries are schematically illustrated in the left panels of Fig. 10b–d. For each geometry, the right panels of Fig. 10b–d display a representative skin soliton localized near the region toward which the couplings are stronger, where the spatial asymmetry is clearly evident. For simplicity, all examples use 2D HN sublattices with non-Hermiticity parameter h = 0.4. We numerically confirmed that skin solitons in these complex lattices also exhibit power thresholds. Consequently, the 2D geometry offers a broad range of possibilities for supporting distinct asymmetric skin soliton solutions in complex non-Hermitian lattices, extending well beyond the 2D NLHN lattice61.

Conclusions

In this work, we have investigated the propagation dynamics of a generalized 2D NLHN lattice, focusing on the intricate antagonism between the skin effect and self-trapping induced by Kerr nonlinearity. In the linear regime, wavefunctions are driven toward a lattice’s preferred corner by the NHSE, whereas the presence of nonlinearity substantially suppresses this delocalization tendency. In particular, for single-site excitation, we have shown that the self-trapping behavior strongly depends on the amplitude of the initial excitation, its position, and the degree of coupling asymmetry. Specifically, excitations near the corner where the linear modes are localized exhibit self-trapping above relatively low amplitude thresholds. By contrast, in the lattice bulk, asymmetric couplings effectively oppose self-trapping, leading to delocalization even at higher excitation amplitudes; for very strong non-Hermiticity, self-trapping in these bulk regions becomes practically impossible. Furthermore, to highlight the differences in this antagonism between focusing and defocusing Kerr-nonlinear regimes, we examined the propagation dynamics of broader initial excitations, revealing a stronger tendency for delocalization in the defocusing case, associated with enhanced diffraction.

Additionally, we have identified and characterized 2D stationary bright soliton solutions in various lattice locations by calculating their associated power-eigenvalue diagrams. These solutions, which extend the concept of skin solitons in two dimensions, consistently display spatial asymmetry biased toward the lattice corner favored by asymmetric couplings. Our study revealed that the soliton power thresholds increase parabolically with the non-Hermiticity parameter h. We have shown that such skin soliton solutions also exist for a plethora of asymmetric lattices with more complicated geometries, apart from the HN lattice. Consequently, our results set the stage for further exploration of skin soliton formation in non-Hermitian lattices61.

Importantly, recent advances in non-Hermitian photonics have enabled the experimental realization of nonlinear non-Hermitian systems in synthetic-mesh lattices38,56. In this platform, Kerr nonlinearity has been implemented through an opto-electronic feedforward loop, enabling the observation of skin solitons in 1D HN lattices56. Moreover, the same synthetic-mesh architecture has been employed to realize linear 2D non-Hermitian lattices, where both spatial dimensions are synthesized by mapping fast and slow time bins of coupled fiber loops onto a 2D lattice38. Given these developments, we believe that extending such schemes to implement Kerr nonlinear effects in 2D non-Hermitian lattices is within reach of current experimental capabilities. In conclusion, our results may provide useful insights into transport and soliton formation in higher-dimensional nonlinear non-Hermitian lattices, which are highly relevant to the emerging field of nonlinear non-Hermitian optics and photonics.

Methods

All numerical simulations of the propagation dynamics were performed using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta (RK4) integration scheme applied to the DNLSEs governing the 2D non-Hermitian lattice. The step size and propagation range were chosen to ensure numerical stability and convergence of the results. Stationary soliton solutions were obtained independently through a Newton-Raphson iterative procedure. Convergence of the Newton-Raphson iterations was verified by monitoring both the residual norm of the nonlinear equations and the stability of the obtained field profiles under direct propagation.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The MATLAB codes used to perform the numerical analyses reported in this work are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

El-Ganainy, R. et al. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 14, 11–19 (2018).

Rüter, C. E. et al. Observation of parity-time symmetry in optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 192 (2010).

Berry, M. V. Physics of non-Hermitian degeneracies. Czechoslovak J. Phys 54, 1039 (2004).

Heiss, W. D. Exceptional points of non-Hermitian operators. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 37, 2455 (2004).

Makris, K. G., El-Ganainy, R., Christodoulides, D. N. & Musslimani, Z. H. Beam dynamics in \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\) symmetric optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 103904 (2008).

El-Ganainy, R., Makris, K. G., Christodoulides, D. N. & Musslimani, Z. H. Theory of coupled optical \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\)-symmetric structures. Opt. Lett. 32, 2632 (2007).

Musslimani, Z. H., Makris, K. G., El-Ganainy, R. & Christodoulides, D. N. Optical solitons in \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\) periodic potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 030402 (2008).

Guo, A. et al. Observation of PT-symmetry breaking in complex optical potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 093902 (2009).

Regensburger, A. et al. Parity-time synthetic photonic lattices. Nature 488, 167 (2012).

Hodaei, H., Miri, M. A., Heinrich, M., Christodoulides, D. N. & Khajavikhan, M. Parity-time-symmetric microring lasers. Science 346, 975 (2014).

Konotop, V. V., Yang, J. & Zezyulin, D. A. Nonlinear waves in \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\)-symmetric systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 035002 (2016).

Feng, L., El-Ganainy, R. & Ge, L. Non-Hermitian photonics based on parity-time symmetry. Nat. Photonics 11, 752 (2017).

Özdemir, S. K., Rotter, S., Nori, F. & Yang, L. Parity-time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat. Mater. 18, 783 (2019).

Komis, I. & Makris, K. G. Angular excitation of exceptional points and pseudospectra of photonic lattices. J. Phys. Photonics 6, 045011 (2024).

Lee, T. E. Anomalous edge state in a non-Hermitian lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 133903 (2016).

Yao, S. & Wang, Z. Edge states and topological invariants of non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086803 (2018).

Longhi, S. Spectral deformations in non-Hermitian lattices with disorder and skin effect: a solvable model. Phys. Rev. B 103, 144202 (2021).

Kokkinakis, E. T., Makris, K. G. & Economou, E. N. Anderson localization versus hopping asymmetry in a disordered lattice. Phys. Rev. A 110, 053517 (2024).

Leventis, A., Makris, K. G. & Economou, E. N. Non-Hermitian jumps in disordered lattices. Phys. Rev. B 106, 064205 (2022).

Kokkinakis, E. T., Makris, K. G. & Economou, E. N. Dephasing-induced jumps in non-Hermitian disordered lattices. Phys. Rev. B 111, 214204 (2025).

Molignini, P., Arandes, O. & Bergholtz, E. J. Anomalous skin effects in disordered systems with a single non-Hermitian impurity. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 033058 (2023).

Delgado-Quesada, J. et al. Analytic solution to degenerate biphoton states generated in arrays of nonlinear waveguides. Phys. Rev. A 111, 013507 (2025).

Hu, S.-X., Fu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Non-Hermitian delocalization induced by residue imaginary velocity. Commun. Phys. 8, 214 (2025).

Hatano, N. & Nelson, D. R. Localization transitions in non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 570 (1996).

Hatano, N. & Nelson, D. R. Vortex pinning and non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. B 56, 8651 (1997).

Feinberg, J. & Zee, A. Non-Hermitian random matrix theory: method of Hermitian reduction. Nucl. Phys. B 504, 579 (1997).

Liu, Y. G. et al. Complex skin modes in non-Hermitian coupled laser arrays. Light Sci.Appl. 11, 336 (2022).

Gao, Z. et al. Two-dimensional reconfigurable non-Hermitian gauged laser array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 263801 (2023).

Ke, S., Wen, W., Zhao, D. & Wang, Y. Floquet engineering of the non-Hermitian skin effect in photonic waveguide arrays. Phys. Rev. A 107, 053508 (2023).

Jiang, C., Liu, Y., Li, X., Song, Y. & Ke, S. Twist-induced non-Hermitian skin effect in optical waveguide arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 151101 (2023).

Li, Y., Lu, C., Zhang, S. & Liu, Y.-C. Loss-induced Floquet non-Hermitian skin effect. Phys. Rev. B 108, L220301 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Observation of dynamic non-Hermitian skin effects. Nat Commun. 15, 6544 (2024).

Weidemann, S. et al. Topological funneling of light. Science 368, 311 (2020).

Zhao, E. et al. Two-dimensional non-Hermitian skin effect in an ultracold Fermi gas. Nature 637, 565 (2025).

Lee, C. H., Li, L. & Gong, J. Hybrid higher-order skin-topological modes in nonreciprocal systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 016805 (2019).

Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Fang, C. Universal non-Hermitian skin effect in two and higher dimensions. Nat. Commun. 13, 2496 (2022).

Zhang, X., Zhang, T., Lu, M. H. & Chen, Y. F. A review on non-Hermitian skin effect. Adv. Phys. X 7, 2109431 (2022).

Zheng, X. et al. Dynamic control of 2D non-Hermitian photonic corner skin modes in synthetic dimensions. Nat. Commun. 15, 10881 (2024).

Chalabi, H. et al. Synthetic gauge field for two-dimensional time-multiplexed quantum random walks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 150503 (2019).

Gong, Z. et al. Topological phases of non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031079 (2018).

Martinez Alvarez, V. M., Barrios Vargas, J. E. & Foa Torres, L. E. F. Non-Hermitian robust edge states in one-dimension: anomalous localization and eigenspace condensation at exceptional points. Phys. Rev. B. 97, 121401 (2018).

Longhi, S. Probing non-Hermitian skin effect and non-Bloch phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 023013 (2019).

Okuma, N., Kawabata, K., Shiozaki, K. & Sato, M. Topological origin of non-Hermitian skin effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 086801 (2020).

Li, L., Lee, C. H., Mu, S. & Gong, J. Critical non-Hermitian skin effect. Nat. Commun. 11, 5491 (2020).

Longhi, S. Non-Hermitian skin effect and self-acceleration. Phys. Rev. B 105, 245143 (2022).

Faugno, W. N. & Ozawa, T. Interaction-induced non-Hermitian topological phases from a dynamical gauge field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 180401 (2022).

Christodoulides, D. N., Lederer, F. & Silberberg, Y. Discretizing light behaviour in linear and nonlinear waveguide lattices. Nature 424, 817 (2003).

Musslimani, Z. H., Makris, K. G., El-Ganainy, R. & Christodoulides, D. N. Analytical solutions to a class of nonlinear Schrödinger equations with-like potentials. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 41, 244019 (2008).

Komis, I., Sardelis, S., Musslimani, Z. H. & Makris, K. G. Equal-intensity waves in non-Hermitian media. Phys. Rev. E 102, 032203 (2020).

Xia, S. et al. Nonlinear tuning of PT symmetry and non-Hermitian topological states. Science 372, 72 (2021).

Dobrykh, D. A., Yulin, A. V., Slobozhanyuk, A. P., Poddubny, A. N. & Kivshar, Y. S. Nonlinear control of electromagnetic topological edge states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 163901 (2018).

Hang, C., Zezyulin, D. A., Huang, G. & Konotop, V. V. Nonlinear topological edge states in a non-Hermitian array of optical waveguides embedded in an atomic gas. Phys. Rev. A 103, L040202 (2021).

Ezawa, M. Dynamical nonlinear higher-order non-Hermitian skin effects and topological trap-skin phase. Phys. Rev. B 105, 125421 (2022).

Zhu, B. et al. Anomalous single-mode lasing induced by nonlinearity and the non-Hermitian skin effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 013903 (2022).

Komis, I., Musslimani, Z. H. & Makris, K. G. Skin solitons. Opt. Lett. 48, 6525 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Nonlinear non-Hermitian skin effect and skin solitons in temporal photonic feedforward lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 243805 (2025).

Manda, B. M. & Achilleos, V. Insensitive edge solitons in a non-Hermitian topological lattice. Phys. Rev. B 110, L180302 (2024).

Longhi, S. Modulational instability and dynamical growth blockade in the nonlinear Hatano-Nelson model. Adv. Phys. Res. 4, 2400154 (2025).

Yuce, C. Nonlinear skin modes and fixed points. Phys. Rev. B 111, 054201 (2025).

Ghaemi-Dizicheh, H. A class of stable nonlinear non-Hermitian skin modes. Phys. Scr. 99, 125411 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Soliton transitions mediated by skin-mode localization and band nonreciprocity. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2508.02311 (2025).

Stegeman, G. I. & Segev, M. Optical spatial solitons and their interactions: universality and diversity. Science 286, 1518 (1999).

Fleischer, J. W., Segev, M., Efremidis, N. K. & Christodoulides, D. N. Observation of two-dimensional discrete solitons in optically induced nonlinear photonic lattices. Nature 422, 147 (2003).

Suntsov, S. et al. Observation of one- and two-dimensional discrete surface spatial solitons. J. Nonlinear Optic. Phys. Mat. 16, 401 (2007).

Lederer, F. et al. Discrete solitons in optics. Phys. Rep. 463, 1 (2008).

Wimmer, M. et al. Observation of optical solitons in PT-symmetric lattices. Nat Commun. 6, 7782 (2015).

Aleahmad, P., Khajavikhan, M., Christodoulides, D. & LiKamWa, P. Integrated multi-port circulators for unidirectional optical information transport. Sci. Rep. 7, 2129 (2017).

Suntsov, S. et al. Power thresholds of families of discrete surface solitons. Opt. Lett. 32, 3098 (2007).

Feng, X., Liu, S., Zhang, S.-X. & Chen, S. Numerical instability of non-Hermitian Hamiltonian evolution. Phys. Rev. B 112, 224310 (2025).

Ablowitz, M. J. & Musslimani, Z. H. Spectral renormalization method for computing self-localized solutions to nonlinear systems. Opt. Lett. 30, 2140 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) and the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) under the 5th Call of the “Science and Society” Action, titled “Always strive for excellence - Theodoros Papazoglou” (Project No. 11496, “PSEUDOTOPPOS”). Computations for this paper were partially conducted on the Metropolis cluster, supported by the Institute of Theoretical and Computational Physics, Department of Physics, University of Crete.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.T.K. and I.K. performed the numerical simulations and analyzed the results. K.G.M. conceived the idea and supervised the project. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Chengzhi Qin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kokkinakis, E.T., Komis, I. & Makris, K.G. Self-trapping and skin solitons in two-dimensional non-Hermitian lattices. Commun Phys 9, 22 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02418-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02418-1