Abstract

Quantum random number generators allow for access of a truly unpredictable random sequence. A popular scheme is based on the laser phase noise, which, however, is generally limited in speed and implementation complexity, especially for chip integration. In this work, a general physical model based on the Wiener process for such schemes is introduced, through which the limitation on generation speed is clearly explained and comprehensive optimization is achieved. We present an insight to exploit the potential frequency band of a quantum entropy source with a simple filtering method and experimentally boost the bandwidth to 20 GHz, where an ultra-fast generation rate of 156 Gbps is demonstrated. Our proposal significantly enhances the ceiling speed of such schemes without requiring extra complex hardware, thus effectively benefiting the corresponding chip integration with high performance and low implementation cost, paving the way for its large-scale applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Random numbers are an essential resource in a wide range of applications, such as statistical sampling, numerical simulations and cryptography. Pseudo random number generators based on computational algorithms provide an easy access to acquiring binary bit sequence that appears random and have been extensively employed in modern information systems. However, due to the deterministic and periodic nature, pseudo random number generators are not suitable for applications where true randomness is required, for instance, the cryptography1 and quantum key distribution system2,3. In contrast, quantum random number generators (QRNGs) extract randomness from quantum processes that can provide truly unpredictable and irreproducible random numbers4,5. Based on the security assumptions for the system setup, existing QRNG schemes can be generally divided into three subcategories4, i.e., the device-independent6,7,8,9,10,11, semi-device-independent12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 and device dependent QRNG22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. Device dependent QRNGs extract randomness from the implementation where physical devices for both the quantum state preparation and measurement are fully characterized and trusted, which to some extent comprises the security but makes it much more advantageous for practical applications4,5. Over the past two decades, huge progress has been made in developing device dependent QRNGs with the generation rate enhanced from 1 Mbps to 100 Gbps.

To further improve the performance and practicality of device dependent QRNGs, it is desirable to exploit schemes beneficial for photonic chip integration, among which the laser phase noise (LPN) based QRNG schemes have attracted considerable attentions40,41,42,43,44,45,50. The laser phase noise is a well understood quantum random phenomenon resulted from the inevitable spontaneous emission during lasing process which can be effectively distilled to generate random numbers. Till now, various such QRNG schemes have been proposed and demonstrated with off-the-shelf components or with photonic integrated unit31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,48,49,50, as shown in Table 1. However, schemes by detecting the phase noise from a single laser requires unbalanced interferometer with long delay line and real-time feedback control, which increases the implementation complexity. As a comparison, schemes by detecting the phase noise between two independent lasers are preferred for chip integration, which removes the requirement for unbalanced interferometer and feedback control to effectively simplify the setup. Nevertheless, to achieve high performance on photonic chip, at least one laser needs to be operated in gain-switched mode, which requires extra hardware or equipment to generate high-speed driving pulses and the system performance is thus directly limited by the pulse generation speed40,43. Therefore, how to realize high performance LPN based QRNG without need of high-speed driving pulses is of significant importance for practical application. Furthermore, in previous works, the randomness quantification and extraction are mainly based on the temporal and statistical analysis of the detection results, where detailed analysis in frequency domain is incomplete, which is crucial for optimizing the bandwidth (BW) of quantum entropy source (QES) and improving the system performance.

In this paper, a general physical model applicable to QRNG schemes by detecting the laser phase noise is established and validated. The model is based on analytically illustrating the laser phase noise with a Wiener process and is effective for accurately predicting and analyzing the detection results both temporally and spectrally, which provides an approach to clearly explain the limitation on the generation rate and comprehensively optimize the system performance. Practically, a simple spectral filtering method is proposed based on detailed frequency domain analysis and is verified experimentally through detecting the phase noise between two independent lasers operating in continuous-wave mode, which is significantly effective for optimizing and extracting the broad BW of the QES to boost the generation rate with no requirements for any extra high-speed driving pulses. Both the analog and digital filtering methods are designed and validated, based on which a real-time generation rate of 10 Gbps and an ultra-fast generation rate of 156 Gbps with off-line post-processing are experimentally demonstrated, respectively, as shown in Table 1. It should be noted that with digital filtering, the passband can be flexibly designed to match the spectrum of the practical detection result with a higher tolerance for environmental fluctuation. Compared with state-of-art for such QRNG schemes, our proposal provides an insight to exploit the potential bandwidth of the corresponding QES that contains plentiful quantum randomness and significantly enhances the ceiling speed of such schemes without requiring extra complex hardware, and thus benefits the corresponding chip integration with low implementation cost and high generation rate, as shown in Table 1.

Results

Physical model

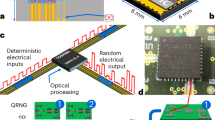

Typical experimental setups for QRNG schemes based on detecting the laser phase noise are shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1a, the random phase shift of the optical signal from a single laser at two different times is distilled via an unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometer. The detection result at the photodiode with active feedback control of phase delay33,36 is generally given by \(v(t)=A\sin \Delta \theta \left(t,{T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\right)\), where Td is the path delay between two arms, \(\Delta \theta \left(t,{T}_{{{\rm{}}}d}\right)=\theta \left(t+{T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\right)-\theta (t)\) is the random phase shift, and A is a conversion factor that includes the amplitude of the optical signal, the attenuation of the optical path and the response of the photodiode, etc. In Fig. 1b, the optical signals from two independent lasers interfere at a 50:50 beam-splitter (BS) to distill the phase noise and the detection result at the photodiode is generally given by \(v(t)=A\cos (\Delta \omega t+\Delta \theta (t))\) where \(\Delta \omega =2\pi \left({f}_{1}-{f}_{2}\right)=2\pi \Delta f\) and Δθ(t) = θ1(t) − θ2(t) are the difference of the angular frequencies and the phase noise fluctuations between the two lasers, respectively.

For the scheme in Fig. 1a, in previous works, \(\Delta \theta \left(t,{T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\right)\) is directly modeled as a Gaussian random variable with variance \({\langle \Delta \theta \left(t,{T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\right)^{2}\rangle }=2{T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}/{\tau }_{{{\rm{c}}}}\)51, where τc = 1/πΔv is the coherence time of the laser with linewidth Δv. Here, we present another physical model from the perspective of a random process on how the phase fluctuation θ(t) evolves. With a sampling period Ts, the sampling results of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) can be expressed in a discretized form as

where \(\theta \left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}+{T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}\right)\) is essentially a delayed term of \(\theta \left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) with n = 0, 1, 2, … Therefore, once the random process \(\theta \left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) is correctly modeled, the detection results \({v}_{1}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) can be obtained. Similarly, for the scheme in Fig. 1b, the sampling results of ADC can be expressed as

Therefore, as long as two independent random processes \({\theta }_{1}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) and \({\theta }_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) are properly modeled, the detection result \({v}_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) can be also obtained.

The phase fluctuation θ physically executes Brownian motion52,53,54, which indicated that θ is a Wiener process in mathematical description, and the variance of phase fluctuation over an interval of time t can be linearly approximated by

where Rsp is the spontaneous emission rate, s is the average number of photons in the cavity, and α is the linewidth enhancement factor, which can be related to the laser linewidth by Δν = Rsp(1 + α2)/(4πs)52. Specifically, for an accurate modeling of the laser phase fluctuation, the parameters Rsp, s, α, etc. can be experimentally measured and verified by employing the stochastic rate equations35,48. Meanwhile, alternatively, for a stable laser with a general Lorentzian spectrum, the phase fluctuation θ(t) can be directly modeled as a Wiener process characterized by the linewidth with \(\theta \left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)-\theta \left((n-1){T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right) \sim N\left(0,2\pi \Delta v{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\)51,55. This approach can effectively simplify the modeling and analysis for optimization of LPN-based QRNG with respect to engineering implementation.

Simulation analysis and system performance optimization

As a result, one can theoretically simulate the detection results \({v}_{1}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) and \({v}_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) in both the time and frequency domains as shown in Table 2.

Based on the proposed model and the corresponding simulation, both the temporal and spectral characteristics for the raw data of QRNG can be accurately predicted, which provides a numerical approach to evaluate the system performance quantitatively under various experimental parameters (e.g., τc, Td, Ts) and therefore a comprehensive optimization can be achieved. For example, for the QRNG scheme in Fig. 1a, it is always advantageous to choose a laser with a larger linewidth as shown in Supplementary Note 1, and one only needs to optimize Td and Ts given τc. The simulation results for different Td with fixed τc are performed in Fig. 2. When Td increases from 200 ps to 1 ns, the distribution uniformity of raw data increases which will enhance the extractable quantum randomness per sample \({H}_{\min }\left({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E\right)\) as explained specifically in Methods25,38, meanwhile the flatness of spectrum that directly determines the BW of QES is significantly compromised which in turn will limit the sampling rate fs. Therefore, optimal Td and fs should be chosen to maximize \({H}_{\min }\left({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E\right)\times BW\), which can be numerically realized with our model. In previous works, one can only qualitatively conclude that one should increase the path delay and decrease the laser coherence time to enhance the distribution uniformity for better performance31,39, where various experimental tests need to be conducted to posteriorly verify the better experimental parameters. While the proposed model in this work in essence poses a more accurate illustration for the evolution of the random phase fluctuation, based on which the numerical optimization can be quantitatively realized in priori.

Though QRNG schemes based on detecting the phase noise from a single laser in Fig. 1a have been extensively demonstrated, an unbalanced interferometer with a delay line and an extra real-time feedback control is generally required, which increases the implementation complexity and is not suitable for chip integration36. To overcome this drawback, QRNG schemes by detecting the phase noise between two independent lasers are further proposed and studied38, where the system setup is simplified effectively. But in previous works38,39, when both lasers are operating in continuous-wave mode, the sampling rate is severely restricted and the generation rate is significantly limited. Thus, to achieve an even higher generation rate, at least one laser is to be operated in gain-switched mode to emit high-speed optical pulse trains, which requires extra complex hardware or equipment to generate high-speed driving pulses34,35,40,42,43. Therefore, how to realize high-performance LPN-based QRNG without the need of high-speed laser pulses is of great importance for practical applications. In the following, the detection of the phase noise between two independent lasers operating in continuous-wave mode, as shown in Fig. 1b, is analyzed based on the proposed model, through which the restrictions on the generation rate are clearly explained, and the corresponding solution is introduced.

The simulation for different laser linewidths Δv1 and Δv2 with beating frequency Δf = 1.9 GHz is performed in Fig. 3. From Fig. 3a, c, e, the detection result follows an arcsine distribution. Note that here the phase noise is the difference between two independent Wiener processes and thus naturally approximates a uniform distribution, which is a significant advantage over the scheme based on a single laser, where the phase noise essentially obeys a Gaussian distribution. The very interesting phenomena are revealed through the spectrum characteristics. From Fig. 3b, d, f, it is shown that when the linewidth is 100 kHz and 1 MHz, an obvious peak power can be observed in both spectrums, and the −3 dB BW of the corresponding QES are 0.14 MHz and 1.73 MHz, respectively. When the linewidth is increased to 100 MHz, the peak power becomes much less significant, and the −3 dB BW of QES increases to 200.43 MHz, which allows for a much higher sampling rate. Note that the sampling rate for a specific QRNG is directly limited by the BW of QES to avoid oversampling that might lead to correlations between ADC samples of raw data, which is further explained in detail in Supplementary Note 2 based on our model. Thus, the performance of the QRNG scheme in Fig. 1b is mainly limited by the BW of QES38,39. To lift the restriction, one may employ lasers with even larger linewidths, which, however, cannot be fulfilled with the most commonly used and cost-effective DFB laser. Moreover, it should be noticed that increasing the laser linewidth or employing more unstable sources might result in the drifts of the laser beating39, which enhances the difficulty to achieve experimental stability. Hence, how to enhance the BW of QES for such a QRNG scheme with narrow linewidth DFB lasers is an interesting question.

a, b Δν1 = Δν2 = 100 kHz, c, d Δν1 = Δν2 = 1 MHz and e, f Δν1 = Δν2 = 100 MHz. The flat area indicates that the power spectrum remains almost constant, while the dominate area represents the beating frequency area. BW bandwith. The beating frequency is fixed at Δf = 1.9 GHz, the sampling frequency is set as fs = 5 GSa s−1(Ts = 200 ps), the conversion factor is set as A = 1 V and the results are calculated from 107 samples.

To solve the problem, through further analysis of the signal spectrum, a simple and practical spectral filtering method is proposed, based on which general continuous-wave lasers with narrow linewidth can be employed to realize high-speed quantum random number generation with high stability and thus the trade-off between the system performance and realization difficulty is achieved. Take the scenario with linewidth 100 kHz in Fig. 3b for instance, the spectrum can be approximately divided into the dominant area, which is 1.5~2.5 GHz, and the flat area, which is 0~1.5GHz. In the dominate area, a significantly broadened peak of about −53 dBm Hz−1 in power centered at 1.9 GHz can be observed, which theoretically dominates the power of the signal. While in the flat area, the power level drastically decreases to about −125 dBm Hz−1 but with flatness. This spectrum shape can be in principle explained as follows. On one hand, the signal \({v}_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) in Eq. (2) is essentially the cosine function of the sum of two terms. The first term is 2πΔf × nTs, which is periodic with the beating frequency Δf and theoretically corresponds to a peak at Δf in the frequency domain. The second term is \({\theta }_{1}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)-{\theta }_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\), which is a random variable similar to white noise and theoretically spreads uniformly over the whole frequency domain. On the other hand, \({\theta }_{1}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)-{\theta }_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) can be treated as a random phase jitter38 that does not change the cosine feature of \({v}_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\), which indicates that the corresponding spectrum is in principle dominated by the term 2πΔf ⋅ nTs. Therefore, the power spectrum of \({v}_{2}\left(n{T}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\right)\) should be a peak at frequency Δf and gradually decay to a stable level in other range with flatness, which is in accordance with our simulation results.

Based on the above analysis in frequency domain, it is theoretically feasible to eliminate the periodicity of the sampled data by spectrally filtering the dominate area that contains the broadened peak and thus the flat area that contains the quantum randomness can be effectively extracted, where, to our best knowledge, for the first time the division of the spectral areas in such QRNG scheme is introduced, inspiring the significant boost of the available bandwidth of QES to explore the potential randomness. As a result, the sampling rate and the generation rate can be significantly enhanced. Take the scenario under a linewidth of 100 kHz, shown in Fig. 3b for instance, it is inferred that by employing a low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 1.5 GHz, the flat area of 0 ~ 1.5 GHz can be distilled and the bandwidth of QES is drastically boosted by over 104 times compared with the original BW of 0.14 MHz. Notably, with proper design of the beating frequency and adequately fast detection and acquisition, the bandwidth of the QES is potentially to reach even over 100 GHz.

As for the entropy estimation, considering a practical scenario, in this paper, we refer to the analysis framework proposed previously25,38 to calculate the conditional min-entropy \({H}_{\min }({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E)\), where Mdis is the discretized result of detection output M and E is the classical noise. The conditional min-entropy \({H}_{\min }({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E)\) quantifies the amount of secure randomness extractable from M under the worst-case scenario where an eavesdropper has complete knowledge of E and thus defends the potential attacks resulted from classical side-information. Specifically, the classical noise E should comprise both the intensity noise introduced by the laser and the overall electrical noise in the circuits for detection and sampling33. As explained in the following, we experimentally measured the laser intensity noise33, and it is validated that the intensity noise is very low and can be neglected, a finding that is consistent with prior results33,37. Thus, we consider that the classical noise E is primarily the electrical noise. Therefore, by turning on and off the laser sources, M and E can be respectively acquired and analyzed in the experiment and \({H}_{\min }({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E)\) can be efficiently estimated, which is described in detail in Methods.

Experimental demonstration

The experiments to verify the proposed model with the setup shown in Fig. 1a and b are both performed. Firstly, for the QRNG scheme in Fig. 1a, a DFB laser with a coherence time of τc ≈ 20 ns (Δv ≈ 16 MHz) is continuously driven as the optical source. Different Td of 500 ps, 1 ns and 2 ns are respectively employed to construct the unbalanced interferometer with feedback control utilized for stability. The interference output is detected by a photodiode with bandwidth 1.6 GHz and a high-performance digital oscilloscope (DSO, Agilent DSAZ254A, 25 GHz bandwidth, 8-bit resolution ADC) is employed as the ADC to acquire the raw data. The corresponding simulations for different Td with fixed τc are also performed for comparison. The result is shown in Fig. 4.

From Fig. 4, it is observed that the experimental data fit well with simulation results under different Td for both the histogram and the power spectrum, which effectively verifies the validity of the proposed model. Especially, it is convincingly demonstrated that our model is of feasibility and flexibility for accurately predicting the variations of the distribution uniformity and spectrum flatness of the experimental raw data, which can be applied to achieve the comprehensive optimization for the QRNG scheme based on detecting phase noise from a single laser.

Secondly, for the QRNG scheme in Fig. 1b, two DFB lasers with central wavelengths of 1550 nm and typical linewidths of 100 kHz in continuous-wave mode are employed as the optical source. The threshold of the laser is 50 mA, and in the experiment both lasers are driven at a current of 100 mA. Optical powers from both lasers at the photodiode are fixed at P = 0.15 mW by controlling the VOAs. Especially, two temperature controllers with an accuracy of 0.01∘C are employed to precisely shift the beating frequency, which is set around Δf = 1.9 GHz in the experiment. The output of the BS is detected by a photodiode with bandwidth 2 GHz and acquired by the DSO to obtain experimental data. To effectively restore the signal feature and verify the proposed model, the sampling rate is set to fs = 20 GSa s−1. By turning on and off the laser sources, the raw data and the electrical noise can be acquired and analyzed, respectively. Meanwhile, by directly connecting the laser output to the PD, the intensity noise of both lasers can be experimentally measured. As a comparison, the corresponding simulations based on the proposed model for the same setup is performed, where the conversion factor is experimentally measured to be A = 0.87V. The result is shown in Fig. 5.

It is observed in Fig. 5 that significant agreements between the simulation results based on our model and the experimental data are achieved with respect to the temporal waveform, the histogram and the power spectrum, which sufficiently verifies the validity of the proposed model. Especially, from Fig. 5c, it is observed that the actual intensity noise of both lasers poses very little contribution to the total measured noise compared with the electrical noise, which indicates that the laser intensity noise can be reasonably neglected33,37. Meanwhile, a clearance of about 15 dB between the raw data and the electrical noise is observed within the flat area, indicating that the quantum signal dominates the power in the corresponding frequency range and the random number generation based on the spectral filtering method should be feasible. Similar experiment results have also been achieved under other system parameters where consistent agreements are still obtained. Moreover, to verify the stability of our QRNG system based on phase noise between two independent lasers, a 12-hour continuous measurement with exactly the same operation conditions is conducted, which can be referred to Supplementary Note 3 for detail.

To extract the frequency band of the flat area with high quantum to classical noise ratio, both the analog and digital filtering methods are designed and implemented, as shown in Fig. 6a and b respectively, where one can either directly employ the off-the-shelf products to realize the analog filtering or integrate the digital filtering in the field programmable gate array (FPGA) as part of the post-processing, thus no extra hardware are required.

a analog filtering method and b digital filtering method. TC Temperature controller, VOA variable optical attenuator, BS beam splitter, PD photodiode, LPF low pass filter, AMP amplifier, ADC analog-to-digital converter, RE randomness extractor, DSO digital storage oscilloscope, DSP digital signal processing, DF digital filter, DS down sampling.

In the experiment of the analog filtering method in Fig. 6a, the output signal of the BS is detected by a photodiode with bandwidth 2 GHz and the beating frequency is set around Δf = 1.9 GHz. Then an analog low pass filter (LPF) with a cut-off frequency of 1.5 GHz is employed to extract the frequency band of the flat area and an amplifier with a gain of 20 dB over the frequency band of 500 kHz to 4 GHz is employed to amplify the signal, which is processed by an ADC and a randomness extractor (RE) to generate the final random bits in real time. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 7.

From Fig. 7a, it is shown that by employing the analog LPF, the frequency band of 0~1.5 GHz is successfully extracted, where the raw data and the electrical noise both show a flat spectrum with a clearance of about 10 dB. Especially, the histograms of the raw data and the electrical noise acquired by the ADC are illustrated in Fig. 7b and c, respectively, which both indicate a Gaussian distribution and fit well with theoretical distribution curves and the conditional min-entropy is calculated to be 11.0407. With the real-time randomness extraction presented in Methods, a real-time generation rate of 10 Gbps is achieved.

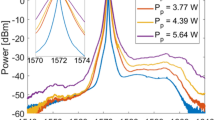

In the experiment of the digital filtering method in Fig. 6b, a high-speed photodiode with bandwidth 50 GHz is employed to optimize the system performance, allowing for an ultra-fast generation rate. The beating frequency is set around Δf = 1.9 GHz. The output of the photodiode is digitized via the DSO at a sampling rate of fs = 80 GSa s−1, after which the sampled data is processed in the digital signal processing (DSP) stage. Notably, although the signal amplitude is relatively small since no amplifier is employed, the DSO sampling range can be appropriately adjusted to match the signal dynamics, which enables high-precision sampling for the measured signal to obtain its accurate amplitude and guarantees the effectiveness of the DSP28,36. In the DSP stage, based on the spectrum of the raw data, the frequency band of 4~24 GHz is determined as the flat area as shown in Fig. 8a. Then, a 10-th order elliptic band-pass digital filter is designed and applied to extract the frequency band of flat area, achieving a QES bandwidth of 20 GHz as shown in Fig. 8b. After the digital filter, to lower the autocorrelation between samples, the filtered raw data is down sampled to 40 GSa s−1 or 20 GSa s−1, respectively, and autocorrelations of the filtered raw data with different sampling rates are calculated, as shown in Fig. 8c. For the balance of the generation rate and randomness, the filtered raw data is down sampled to 40 GSa s−1, which is exactly twice the bandwidth of filtered QES28. The histograms of the data after DSP are depicted in Fig. 8d and e, where the raw data and electrical noise both obey Gaussian distribution with a conditional min-entropy of 3.962. Finally, the randomness extraction is implemented and an ultra-fast generation rate of 156 Gbps is achieved. Detailed analysis results of the DSP stage and randomness extraction are shown in Methods.

a Power spectrum of the raw data (blue curve) and the electrical noise (red curve) before DF. b Power spectrum of the raw data (blue curve) and the electrical noise (red curve) after DF. c Autocorrelation of the raw data after DF for sampling rate of 80 GSa s−1 (solid blue curve), 40 GSa s−1 (dashed red curve), and 20 GSa s−1 (dash-dotted yellow curve), respectively. d and e Histograms of the raw data (blue bar) and the electrical noise (red bar) after DF and DS. DF digital filter. DS down-sampling.

Based on the experimental results, it is expected that by employing detection and acquisition with even higher speed, the BW of QES can be further enhanced and effectively extracted with the digital filtering method to realize the even higher generation rate. Especially, in practical experiments, the shift of the beating frequency is inevitable due to environmental fluctuation, which results in the variation of the target flat area. In this scenario, by flexibly designing the passband of the digital filter to match the practical spectrum of the raw data, the flat area can also be extracted, and the random number generation is guaranteed. Thus, compared with the analog filtering method, where the pass band is fixed with the employed analog filter, the digital filtering method allows for a higher tolerance of the environmental fluctuation and is feasible for other QRNG schemes28.

Discussion

In this work, we have proposed a general physical model based on the Wiener process for LPN-based QRNG schemes to clearly explain the limitation on the generation rate and comprehensively optimize the system performance through detailed temporal and spectral analysis. Especially, to the best of our knowledge, the division of the spectrum in such QRNG schemes is introduced and explained, based on which the available bandwidth of QES is boosted up to 20 GHz, and an ultra-fast generation rate of 156 Gbps is realized experimentally with a practical spectral filtering method. In particular, with our proposal, it is expected to achieve a QES bandwidth of over 100 GHz with adequately fast detection, which might not be the upper bound, and leaves further exploration.

It should be noted that, for the scheme where a laser operating in gain-switched mode is employed35, the phase fluctuation is more efficiently accelerated for random number generation and accurately verified using stochastic rate equations35,48, where a higher min-entropy per sample is realized. While for the scheme where stable lasers in CW mode are employed, as presented in this paper, the hardware design is simpler with an effective spectral filtering method employed to achieve a higher QES bandwidth and hence sampling rate, where an ultra-fast random number generation is finally realized.

For future study, three research directions are concluded. First, it is expected to improve the security analysis framework for our proposal, such as to develop a theoretical model that accounts for the non i.i.d. feature of raw data and the quantum side information27. Second, it is valuable to perform a more accurate modeling and verification of the laser dynamics based on the stochastic rate equations. Third, it is feasible to optimize our proposal for miniaturization and chip-scale design with the application of photonic integrated circuits (PICs) to allow for the integration of interferometric and detection modules, etc.

Our work significantly enhances the ceiling speed of LPN-based QRNG schemes without requirements for long optical delay lines or extra complex hardware, which particularly benefits the forthcoming chip integration with low implementation cost and high generation rate. Furthermore, our proposal is expected to be suitable for practical applications that require huge amounts of random numbers with a fast generation rate and compact design. For instance, one promising application is the integrated photonic QKD systems44,56,57, where our proposal can be employed to generate random numbers for the quantum state preparation, detection, and postprocessing, based on which we believe our proposal effectively contributes to the maturation and miniaturization of the QKD system and poses part of the solution for the deployment of the future global quantum secure communication network. Besides, our work can also be applied in commercial fields to achieve high performance and security, such as the large-scale cloud platform, the next generation internet of things, etc.

Methods

Conditional min-entropy

Since the classical electrical noise in practical experiments might be known or even controlled by an adversary, we calculate the conditional min-entropy25 for each ADC sample to distill secure quantum randomness from the raw measurement data, as follows.

In our experiments, the measured total signal M can be modeled as M = Q + E. Here Q and E respectively represent the quantum noise signal with probability density function (PDF) PQ and the classical noise signal with PDF PE, which are generally assumed to be statistically independent. As observed in the experiments, Q and E both obey the Gaussian distribution with zero mean and variance \({\sigma }_{Q}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{E}^{2}\), thus the PDF of M can be expressed as

for m ∈ M where the measurement variance \({\sigma }_{M}^{2}={\sigma }_{Q}^{2}+{\sigma }_{E}^{2}\). Therefore, the conditional PDF between the measured signal M and the classical noise E is given by

Then the sampling is performed through an n-bit ADC with dynamic range [ − R + δ/2, R − 3δ/2], where δ = R/2n−1 represents the sampling bin width. Correspondingly, the discretized conditional probability distribution is

where mi = δ × i and i is a integer \(\in \left\{-{2}^{n-1},\ldots ,{2}^{n-1}-1\right\}\) with \({i}_{\min }\) and \({i}_{\max }\) represent the first and last bin to account for the saturation, respectively.

Therefore, the worst-case min-entropy conditioned on the classical noise E for the discretized measured signal is given by25

By performing integration on Eq. (6), the maximization for Eq. (7) can be conducted

where \({{\mathrm{erf}}}\,(x)=2/\sqrt{\pi }\int_{0}^{x}{e}^{-{t}^{2}}dt\) is the error function, and the classical noise is bounded in \([{e}_{\min },{e}_{\max }]\) with generally \({e}_{\min /\max }=\pm 5{\sigma }_{E}\) or \({e}_{\min /\max }=\pm 10{\sigma }_{E}\) for a practical scenario. With Eq. (8), the secure randomness of each sample conditioned on the classical noise is fully known with arbitrary precision to the eavesdropper can be calculated.

Real-time randomness extraction for the analog filtering

In the experiment of the analog filtering method in Fig. 6a, with the ADC sampled data, it is calculated that the variance of raw data and electrical noise are \({\sigma }_{M}^{2}=1.792\times 1{0}^{-3}\,{{{V}}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{E}^{2}=1.075\times 1{0}^{-4}{V}^{2}\), respectively, which infers that the quantum noise signal theoretically obeys Gaussian distribution with variance \({\sigma }_{Q}^{2}={\sigma }_{M}^{2}-{\sigma }_{E}^{2}=1.684\times 1{0}^{-3}{V}^{2}\). The ADC employed is with a sampling range of 2R = 0.8 V, a digitization resolution of n = 14 and a sampling rate of 1 GSa s−1. Thus, one can estimate the conditional min-entropy of the raw data \({H}_{\min }\left({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E\right)=11.0407\)25. Correspondingly, a Toeplitz hash matrix with the dimension 7168 × 5120 integrated in FPGA is developed as the RE to generate the final random bits, achieving a real-time generation rate of 10 Gbps, which is significantly boosted compared with previous similar works38,39. The final random bit sequences have passed all the NIST-STS statistical tests, which is presented in detail in Supplementary Note 4.

Detailed analysis of the DSP stage and randomness extraction for the digital filtering method

Detailed analysis for the DSP stage in the experiment of the digital filtering method in Fig. 6b is as follows. Firstly, power spectrum of the acquired data is calculated, as illustrated in Fig. 8a. Benefiting from the high-speed PD and DSO, it is shown that the effective range of the spectrum reaches up to 25 GHz and thus much more frequency band that contains plentiful quantum randomness can be potentially exploited, which provides precious resources for random number generation. For the spectrum of the raw data, a peak near 1.9 GHz that corresponds to the beating frequency is observed, which is unwanted and should be filtered. Especially, from Fig. 8a, it is shown that within the range of 4~24 GHz, the power levels of the raw data and the electrical noise are stably around -145 dBm Hz−1 and -157 dBm Hz−1, respectively, which indicates that a clearance over 10 dB with flatness can be achieved in this range and therefore the frequency band of 4~24 GHz is thus determined as the flat area.

Then a 10th-order elliptic band-pass digital filter (DF) is designed and applied to the acquired data to extract the frequency band of the flat area. Correspondingly, the power spectrum of the data after DF is also calculated, as shown in Fig. 8b. On one hand, it is observed that the original spike has been attenuated to the power level which approximates that of the electrical noise and thus the periodicity should be in principle, be eliminated. On the other hand, the frequency band of the flat area has been successfully extracted with the clearance and flatness reserved significantly. Thus, as a result, a bandwidth of the QES up to 20 GHz has been achieved.

After the DF, to lower the autocorrelation between samples, the filtered raw data is down-sampled to 40 GSa s−1 or 20 GSa s−1, respectively, and then autocorrelations of the filtered raw data with different sampling rates are calculated, as shown in Fig. 8c. It is observed that, when the sampling rate is 80 GSa s−1 (i.e., without down-sampling), the filtered raw data shows the highest autocorrelation. When the filtered raw data is down-sampled to 40 GSa s−1, the autocorrelation is comparable but slightly higher than that when down-sampled to 20 GSa s−1, which are both obviously lower than that without down-sampling. Thus, for the balance of the generation rate and randomness, the filtered raw data is down-sampled to 40 GSa s−1, which is exactly twice the bandwidth of filtered QES28.

Finally, with the data after the DF, given a sampling range of 2R = 0.06V and digitization resolution n = 8, which are consistent with that for data acquisition through the DSO, it is calculated that the raw data and electrical noise obey a Gaussian distribution with variance \({\sigma }_{M}^{2}=2.277\times 1{0}^{-6}\,{{{V}}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{E}^{2}=1.557\times 1{0}^{-7}\,{{{V}}}^{2}\), and one eventually obtains \({H}_{\min }({M}_{{{\rm{dis}}}}| E)=3.962\). Correspondingly, a Toeplitz hash matrix with the dimension 4096 × 2000 is employed as the RE to generate the final random bits, achieving an ultra-fast generation rate of 156 Gbps. The final random bit sequences have passed all the NIST-STS statistical tests, which is presented in detail in Supplementary Note 4.

Data availability

The data that support the results of this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code generated for the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Schneier, B. Applied Cryptography (Wiley, New York, 1996).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145–195 (2002).

Scarani, V. et al. The security of practical quantum key distribution. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1301–1350 (2009).

Ma, X., Yuan, X., Cao, Z., Qi, B. & Zhang, Z. Quantum random number generation. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 16021 (2016).

Herrero-Collantes, M. & Garcia-Escartin, J. C. Quantum random number generators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015004 (2017).

Pironio, S. et al. Random numbers certified by Bell’s theorem. Nature 464, 1021–1024 (2010).

Liu, Y. et al. Device-independent quantum random-number generation. Nature 562, 548–551 (2018).

Bierhorst, P. et al. Experimentally generated randomness certified by the impossibility of superluminal signals. Nature 556, 223–226 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Experimental low-latency device-independent quantum randomness. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 010505 (2020).

Liu, W.-Z. et al. Device-independent randomness expansion against quantum side information. Nat. Phys. 17, 448–451 (2021).

Li, M.-H. et al. Experimental realization of device-independent quantum randomness expansion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 050503 (2021).

Cao, Z., Zhou, H., Yuan, X. & Ma, X. Source-independent quantum random number generation. Phys. Rev. X 6, 011020 (2016).

Marangon, D. G., Vallone, G. & Villoresi, P. Source-device-independent ultrafast quantum random number generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 060503 (2017).

Avesani, M., Marangon, D. G., Vallone, G. & Villoresi, P. Source-device-independent heterodyne-based quantum random number generator at 17 Gbps. Nat. Commun. 9, 5365 (2018).

Xu, B. et al. High speed continuous variable source-independent quantum random number generation. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4, 025013 (2019).

Nie, Y.-Q. et al. Experimental measurement-device-independent quantum random-number generation. Phys. Rev. A 94, 060301 (2016).

Lunghi, T. et al. Self-testing quantum random number generator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 150501 (2015).

Brask, J. B. et al. Megahertz-rate semi-device-independent quantum random number generators based on unambiguous state discrimination. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 054018 (2017).

Avesani, M., Tebyanian, H., Villoresi, P. & Vallone, G. Semi-device-independent heterodyne-based quantum random-number generator. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 034034 (2021).

Tebyanian, H. et al. Semi-device independent randomness generation based on the quantum state’s indistinguishability. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 045026 (2021).

Lin, X. et al. Certified randomness from untrusted sources and uncharacterized measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 050506 (2022).

Jennewein, T., Achleitner, U., Weihs, G., Weinfurter, H. & Zeilinger, A. A fast and compact quantum random number generator. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 71, 1675–1680 (2000).

Sanguinetti, B., Martin, A., Zbinden, H. & Gisin, N. Quantum random number generation on a mobile phone. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031056 (2014).

Gabriel, C. et al. A generator for unique quantum random numbers based on vacuum states. Nat. Photonics 4, 711–715 (2010).

Haw, J.-Y. et al. Maximization of extractable randomness in a quantum random-number generator. Phys. Rev. Appl. 3, 054004 (2015).

Raffaelli, F. et al. A homodyne detector integrated onto a photonic chip for measuring quantum states and generating random numbers. Quantum Sci. Technol. 3, 025003 (2018).

Gehring, T. et al. Homodyne-based quantum random number generator at 2.9 Gbps secure against quantum side-information. Nat. Commun. 12, 605 (2021).

Bruynsteen, C., Gehring, T., Lupo, C., Bauwelinck, J. & Yin, X. 100-Gbit/s integrated quantum random number generator based on vacuum fluctuations. PRX Quantum 4, 010330 (2023).

Bruynsteen, C., Vanhoecke, M., Bauwelinck, J. & Yin, X. Integrated balanced homodyne photonic-electronic detector for beyond 20 GHz shot-noise-limited measurements. Optica 8, 1146–1152 (2021).

Bai, B. et al. 18.8 Gbps real-time quantum random number generator with a photonic integrated chip. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 264001 (2021).

Qi, B., Chi, Y.-M., Lo, H.-K. & Qian, L. High-speed quantum random number generation by measuring phase noise of a single-mode laser. Opt. Lett. 35, 312–314 (2010).

Guo, H., Tang, W., Liu, Y. & Wei, W. Truly random number generation based on measurement of phase noise of a laser. Phys. Rev. E 81, 051137 (2010).

Xu, F. et al. Ultrafast quantum random number generation based on quantum phase fluctuations. Opt. Express 20, 12366–12377 (2012).

Yuan, Z. L. et al. Robust random number generation using steady-state emission of gain-switched laser diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 261112 (2014).

Abellán, C. et al. Ultra-fast quantum randomness generation by accelerated phase diffusion in a pulsed laser diode. Opt. Express 22, 1645–1654 (2014).

Nie, Y.-Q. et al. The generation of 68 Gbps quantum random number by measuring laser phase fluctuations. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86, 063105 (2015).

Yang, J. et al. 5.4 Gbps real-time quantum random number generator with simple implementation. Opt. Express 24, 27475–27481 (2016).

Sun, S.-H. & Xu, F. Experimental study of a quantum random-number generator based on two independent lasers. Phys. Rev. A 96, 062314 (2017).

Álvarez, J.-R., Sarmiento, S., Lázaro, J. A. & Torres, J. P. Random number generation by coherent detection of quantum phase noise. Opt. Express 28, 5538–5547 (2020).

Abellán, C. et al. Quantum entropy source on an InP photonic integrated circuit for random number generation. Optica 3, 989–994 (2016).

Raffaelli, F. et al. Generation of random numbers by measuring phase fluctuations from a laser diode with a silicon-on-insulator chip. Opt. Express 26, 19730–19741 (2018).

Imran, M. et al. On-chip tunable SOI interferometer for quantum random number generation based on phase diffusion in lasers. Opt. Commun. 485, 126736 (2021).

Roger, T. et al. Real-time interferometric quantum random number generation on chip. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 36, B137–B142 (2019).

Paraiso, T. K. et al. A photonic integrated quantum secure communication system. Nat. Photonics 15, 850–856 (2021).

Chrysostomidis, T. et al. Long term experimental verification of a single chip quantum random number generator fabricated on the InP platform. EPJ Quantum Technol. 10, 5 (2023).

Williams, C. R. S., Salevan, J. C., Li, X., Roy, R. & Murphy, T. E. Fast physical random number generator using amplified spontaneous emission. Opt. Express 18, 23584–23597 (2010).

Yang, J. et al. Randomness quantification for quantum random number generation based on detection of amplified spontaneous emission noise. Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 015002 (2020).

Lovic, V., Marangon, D. G., Lucamarini, M., Yuan, Z. & Shields, A. J. Characterizing phase noise in a gain-switched laser diode for quantum random-number generation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 054012 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Quantum random number generation based on phase reconstruction. Opt. Express 32, 5056–5071 (2024).

Marangon, D. G. et al. A fast and robust quantum random number generator with a self-contained integrated photonic randomness core. Nat. Electron. 7, 396–404 (2024).

Yariv, A. & Yeh, P.Photonics: Optical Electronics in Modern Communications (Oxford University Press, New York, 2007).

Henry, C. Theory of the linewidth of semiconductor lasers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 18, 259–264 (1982).

Henry, C. Theory of the phase noise and power spectrum of a single mode injection laser. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 19, 1391–1397 (1983).

Henry, C. Phase noise in semiconductor lasers. J. Lightwave Technol. 4, 298–311 (1986).

Lax, M. Classical noise. V. Noise in self-sustained oscillators. Phys. Rev. 160, 290–307 (1967).

Zhang, G. et al. An integrated silicon photonic chip platform for continuous-variable quantum key distribution. Nat. Photonics 13, 839–842 (2019).

Wang, J., Sciarrino, F., Laing, A. & Thompson, M. G. Integrated photonic quantum technologies. Nat. Photonics 14, 273–284 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Cryptologic Science Fund of China (Grant no. 2025NCSF02053), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants nos. 62171418, 62201530, 62471446, 62301517 and U24B20135), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grants nos. 2022ZDZX0009, 2023JDRC0017, 2024JDDQ0008, 2024NSFSC0470, 2024NSFSC0454 and 2025ZNSFSC1473), the National Key Laboratory of Security Communication Foundation (Grant no. 6142103042301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y., B.J.X., B.L., and H.G. conceived the idea. B.J.X., B.L., and H.G. supervised the work. J.Y., B.J.X., B.L., and H.G. performed the theoretical analysis and simulation for the physical model. J.Y., M.W., and Y.L. conceived and implemented the experiment. J.Y., Y.M.B. and Y.C.Z. acquired the experimental data and performed the data analysis. H.W. and Y.P. implemented the randomness extraction integrated in the FPGA under the supervision of Q.S., W.H., and S.Y. M.W. and H.Y.J. validated the NIST randomness tests. J.Y., Y.C.Z., and B.J.X. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Wu, M., Zhang, Y. et al. An ultra-fast quantum random number generation scheme based on laser phase noise. Commun Phys 9, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02436-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02436-z