Abstract

Laser wakefield acceleration (LWFA) holds great potential in the exploration of the next-generation accelerators and future colliders, in which the injection mechanism plays a crucial role as it directly affects the characteristics of electron acceleration. Ionization injection is a continuous injection mechanism that enables producing high-charge electron beams via LWFA, at the cost of broad spectrum of the accelerated electrons. Recently, an improvement to the ionization injection mechanism has been theoretically proposed. The so-called scissor-cross ionization injection enables short injection lengths and quasi-simultaneous injection of the electrons. In this work, we experimentally demonstrate such injection mechanism, which uses an additional intense laser pulse intersecting the wakefield accelerator at an acute angle to trigger the scissor-cross ionization injection. When the time delay between the laser pulses is finely varied within the pulse duration, the method enables precise tuning of the injection process, of the charge and of the energy spread of the electron beam. Our successful demonstration of the scissor-cross ionization injection leads to a high-charge 224 MeV electron beam with energy spread below 5%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent rapid progress in ultra-intense short-pulse lasers1 have opened up high-field physics such as particle acceleration via laser-plasma interactions2,3,4,5 and electron-driven light sources6,7,8. The considerably stronger accelerating gradients in laser plasma wakefield acceleration (LWFA) reduce the size of accelerators to a standard laboratory footprint, significantly enabling access to universities and smaller research centers.

In the past few decades, LWFA has achieved many milestone breakthroughs9,10,11,12,13,14,15. In the process, the injection mechanism affects the dynamic behavior of electrons in the wakefield and directly influences the quality of the resulting electron beam16,17,18,19,20,21. Ionization injection is a stable mechanism that utilizes the higher ionization energy of K-shell electrons compared to L-shell electrons, allowing the release of K-shell electrons in the pseudo-potential well of the wakefield22,23,24,25. Ionization injection has been experimentally demonstrated24,26,27, and exhibits injection repeatability28, with diverse applications29,30. As a simple and efficient mechanism, ionization injection is a promising injection method for compact accelerators and future colliders.

However, when the laser evolution process reaches the ionization threshold, the electrons are injected continuously, leading to a large energy spread. Researchers are dedicated to truncating this continuous injection and controlling beam quality. Approaches include the density shock fronts31, initially unmatched laser pulses used for self-truncation32,33,34, and schemes that separate the injection stage from the acceleration stage, such as dual nozzles35, dual gas cells36,37, and structured plasma sources38.

The concept of introducing an additional laser beam to regulate the LWFA, known as optical injection, was proposed39,40,41 and subsequently demonstrated experimentally42,43. Consequently, the dual-laser scheme for tuning the ionization injection process has also been proposed through theoretical analysis and particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations44,45,46. With the continuous advancements in laser facilities47 and spatiotemporal synchronization technology48, dual-beam experiments have made significant progress in foundational scientific research, including Thomson scattering49,50 and plasma physics51. The dual-beam approach is applied across various domains, including LWFA52,53, beam-driven plasma wakefield acceleration54,55, ion acceleration56, attosecond X-ray pulse generation57, and terahertz radiation58,59.

In 2022, Wang et al. proposed the scissor-cross ionization injection21, which uses an oblique auxiliary laser to trigger ionization injection. In this scheme, the superimposed electric field of the two laser pulses plays a dominant role, with ionization occurring only when this field reaches the ionization threshold. The ionization injection is shut down once the trigger laser leaves the collision point.

In this work, we demonstrate the scissor-cross ionization injection by using an intense trigger pulse intersecting with a wakefield accelerator at an acute angle, and illustrate the enhancement it brings for the electron quality. By comparing of different injection cases, we found that the scissor-cross ionization injection can conveniently and reliably control the electron injection. When the trigger laser was turned on, the superimposed electric field at an acute angle initiated early ionization injection in a confined region. The resulting short injection length ensured that the electrons were injected nearly simultaneously in the same specific acceleration phase, ultimately yielding a quasi-monoenergetic electron beam. The controllability and reproducibility provided by this injection mechanism offer a option for producing high-quality electron beams in laser-plasma accelerators.

Results

The experimental setup

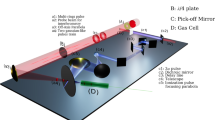

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1a. The driver laser (DL) propagated along the nozzle axis on the horizontal plane, while the trigger laser (TL) was incident on the nozzle at 30° with respect to the DL. The focal points of the dual laser beams coincided at 500 µm downstream from the nozzle edge with femtosecond-scale spatiotemporal synchronization48,60. The overlap and synchronization processes of the two lasers are provided in the Supplementary Note 1. In the experiment, nitrogen and helium were respectively used as gas targets in different shots to distinguish between the injection mechanisms. In the nitrogen atom, L-shell electrons are ionized by the prepulse of the DL to form the background plasma, and the main pulse of the DL excites the plasma wakefield, but is insufficient to ionize the K-shell electrons. The superimposed electric field of the dual lasers is capable of ionizing the K-shell electrons of nitrogen, thus inducing electron injection, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

a The driver laser and trigger laser focused at the same point 1.5 mm above the nozzle (along the central axis of the nozzle, 500 µm from the nozzle front edge). Topview shows the fluorescence captured from the plasma channel. b Illustration of pre-ionization and ionization injection processes of the scissor-cross ionization injection. The driving laser ionizes the outer-shell electrons of atoms, forming wakefield. When temporally and spatially synchronized with the trigger laser, the superimposed electric field ionizes the inner-shell electrons, leading to localized injection.

Guided by the PIC study of Wang et al.21, we adopt a 30° scissor-cross geometry, which was identified as a compromise between capture efficiency and spectral quality. Larger (more obtuse) angles favor ponderomotive injection, whereas very small angles extend the overlap region, leading to nearly continuous ionization and a broader energy spread. At around 30°, ionization occurs in a localized space-time volume, which promotes efficient trapping while keeping the energy spread under control. In our high-power setup, a systematic angle scan is technically demanding (it requires re-arranging off-axis parabolic mirrors and re-optimizing the sub-10-fs spatiotemporal overlap); therefore, we fixed the configuration at 30° and verified the mechanism under this condition. A dedicated angle-scan study will be pursued in future work.

Experimental results and analysis

A series of experiments have been conducted using different gas types, and the TL has been turned on or off in different cases. When nitrogen was used as a target with TL turned on, the scissor-cross ionization injection occurred, which leads to the production of quasi-monoenergetic electron beams as shown in Fig. 2a. By contrast, when helium was used as the target with the TL turned on, the collision injection mechanism dominated, and broad energy spread electron beams were generated, as shown in Fig. 2b. With the TL turned off, as shown in Fig. 2c, unstable electron beams were generated. When helium was used with the TL turned off, the injection mechanism was self-injection with unstable electron injection, as shown in Fig. 2d. In the case of a single DL pulse interacting with the plasma, only about 20% of the shots in nitrogen and 40% of those in helium yielded high-energy electrons (>100 MeV). This is a consequence of our experimental design, where the DL intensity is deliberately set close to, but slightly below, the ionization injection threshold. We only display those shots where electron production was observed.

The signal from the spectrometer in four cases: a nitrogen with DL and TL, b helium with DL and TL, c nitrogen with DL only, d helium with DL only. e The spectrum exhibiting the smallest energy spread in each of the four cases, which corresponds to each of the first shots in (a–d). f The averaged charge and energy of the four cases, with error bars representing the standard deviation of the 10 shots in each case. It should be noted that the shots were not acquired in sequential order, and the shots with no signal due to the laser instability were removed.

We select the results with the best energy spread in each of the four cases described above and show the corresponding electron energy spectra in Fig. 2e. In the case of nitrogen with both DL and TL, the electron energy spectrum exhibited an energy spread of 4% in full-width-half-maximum (FWHM) and the beam quality was markedly superior to those of the other cases. For comparison, the electron energy spread was no less than 27% in FWHM in the case of helium with DL and TL, 9% in FWHM in the case of nitrogen with DL only, and no less than 11% in FWHM in the case of helium with DL only. Statistical results are shown in Fig. 2f, which also confirm that the electron beam generated by scissor-cross ionization injection exhibits both higher charge and energy.

The collision point in Fig. 2a was located 500 μm downstream of the nozzle entry. As shown in Fig. 2a, due to the consistent injection region, the electron beam exhibited a distinct monoenergetic peak and low energy spread (with an energy spread of approximately 4%). When nitrogen was replaced by helium, an electron beam with a long-tailed energy distribution was generated from collision pulse injection, as shown in Fig. 2b. In addition, when a single laser pulse (DL) interacts with nitrogen, its dynamic evolution and the self-focusing effect lead to uncontrollable electron injection, as shown in Fig. 2c. Based on the electron energy results shown in Fig. 2d, the self-injection process in the case of helium with DL only remains uncontrollable. While the TL does not alter the injection threshold, in our parameter window, secondary injection of background plasma electrons by DL only is weak and unstable (even for the case of helium with 0.4 MPa backing pressure), and the superimposed field opens a short, localized window where ionization injection dominates, with no statistically significant secondary injection observed, as shown in Fig. 2a. By triggering ionization injection within a confined region of the superimposed electric field, the injected electrons are nearly injected at the same acceleration phase, leading to a reduced energy spread. The final experimental results reveal the unique advantages of the scissor-cross ionization injection mechanism.

Analysis of the electron sources reveals that nearly all electrons originate from the ionization injection rather than from colliding-pulse injection. The experimental results above were performed under a condition of 0 fs delay between the two laser pulses. Only if the TL precedes the DL by several nanoseconds, may the TL sufficiently modulate the plasma density to induce density downramp injection30,61. However, in our experiment, this delay between the two pulses is precisely controlled on the femtosecond scale. Thus, the density downramp injection is unlikely to occur.

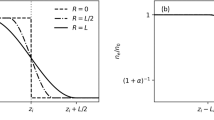

To precisely control the occurrence of scissor-cross ionization injection, the delay between the DL and the TL was scanned and the variations in electron peak energy and charge were assessed. The results, as shown in Fig. 3a, align with the previous theoretical work21. The energy of the accelerated electrons is maximized when the collision occurs at the spatiotemporal synchronization point of the dual beams. However, advancing or delaying the TL results in an enlarged region where inner-shell electrons are ionized, facilitating more electron capture, leading to a significant increase in electron charge. However, under these delay conditions, the captured electrons are predominantly situated in regions with a lower accelerating field. This leads to a reduction in electron energy and a broader energy distribution due to electrons occupying different acceleration phases, resulting in a larger energy spread.

a The statistical results of electron beam energy and charge under various delays between the two laser beams, with 5 shots for each case. Positive means the TL is before the DL. And the error bars represent the standard deviation of the 5 shots. b Evolution of energy spectrum as the pulse width and energy of the TL changes, while the delay is set to 0. The results show the transition from conventional ionization injection to scissor-cross ionization injection.

The detailed quantitative transition from the injection mechanism induced by DL self-focusing to the scissor-cross ionization injection is shown in Fig. 3b. By adjusting the energy and pulse width of the TL, the corresponding beam charge and energy spectrum of electrons were obtained. As shown in Fig. 3b, altering the pulse width and energy of the trigger laser significantly modifies the laser intensity, thereby changing the superimposed electric field produced by the DL and the TL. As the superimposed electric field exceeded the ionization threshold, the ionization region expanded with enhanced ionization injection and the emergence of a monoenergetic peak. The transition process and the appearance of a monoenergetic peak indicate the controllability of the injection process. Compared to previous density modulation methods with a shock31, the lower energy spread achieved by localized injection with the TL provides greater tunability. As the pulse width increases, the duration above the injection threshold is lengthened, which increases the electron charge.

Accordingly, the femtosecond delay between the DL and TL sets the injection phase and effective injection length, thereby controlling the injected charge and the energy spread; the TL pick-up energy and pulse duration set the local ionization rate and the width of the injection window, enabling further tuning of charge and energy spread. In future experiments, the final energy can also be tuned by translating the DL–TL collision point along the plasma.

Discussion

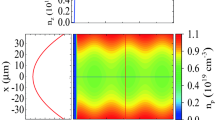

We carried out simulations with mostly the same parameters, except that the gas type was switched between nitrogen and helium. Figure 4a–c shows the central slices of the drive laser and the density of the plasma electrons at different time steps in the case of nitrogen. The moment when the lasers collide is shown in Fig.4a, while Fig. 4b, c shows the subsequent moments of acceleration. When the two lasers overlap, the superimposed electric field reaches the ionization threshold of the nitrogen atom’s K-shell and the electrons are ionized, realizing the local ionization injection. The longitudinal size of the injected electrons is small (~2 μm), so the electrons experience a nearly uniform longitudinal accelerating field, as shown in Fig.4b–c. In the case of helium, the overlap of two lasers triggers the collision injection, instead of the ionization injection. Figure 4d–f shows the plots with helium gas. Only an electron charge of 0.13 pC is injected into the wakefield with a broad energy spectrum in this case, which is ~2 orders of magnitude smaller than that in “nitrogen with DL + TL”. The simulated energy spectra based on the four cases are shown in Fig. 4g, all at the same plasma density of 1.5 × 1018 cm−3, corresponding to the density used in the nitrogen cases in the experiment. Due to limited experimental time, no helium shots were performed at this density. In the experiment, the helium cases employed a plasma density of 3.5 × 1018 cm−3. One additional PIC simulation for the helium with TL + DL case and the plasma density 3.5 × 1018 cm−3 shows that the injected charge increases to 12.79 pC, which is consistent with the experiment (See Supplementary Note 3).

a–c Nitrogen target: snapshots when the two lasers collide at z = 500 μm and at later times during acceleration. Electrons originating from the scissor-cross ionization injection are shown in green, while background plasma electrons are displayed in gray. The contribution from the scissor-cross ionization injection accounts for 88% of the total injected charge. d–f Same plots for helium. The red-blue colormap shows the electric field of the laser. The quantities ρe and ρe,ion denote, respectively, the charge density of the pre-ionized electrons and the charge density of the newly ionized (inner-shell) electrons; both are normalized to enp, where e is the elementary charge and np is the unperturbed background plasma density. The oblique trigger-laser field is not displayed because it is not defined on the simulation grid. Instead, it is realized by analytically defining the external electromagnetic field68. All the colorbars refer to panels (a–f). g Simulated electron-energy spectra under different gas/laser conditions; the spectra for “helium with DL + TL” and “nitrogen with DL” are multiplied by 20 for visibility due to the very small injected amount.

In the case of nitrogen with TL and DL, the maximum electron energy and charge are higher than those observed for helium. More importantly, the electron spectrum produced by the scissor-cross ionization injection mechanism exhibits a quasi-monoenergetic peak. Moreover, the simulation results show that when a single laser pulse interacts with nitrogen plasmas, only a small number of electrons are injected and accelerated above 100 MeV. Under the same plasma density, replacing nitrogen with helium results in no electron injection. Although we occasionally observed unstable electron spectra in the experiments, the simulations indicate that high-energy electrons are not generated under single DL conditions with these laser and plasma parameters. The simulation results are consistent with the experimental observations and highlight the advantages of the scissor-cross ionization injection mechanism.

The simulation results show that the superimposed electric field exceeds the ionization threshold only within a confined region for a short period. This short injection window allows the electrons to be injected nearly simultaneously and to remain in the same acceleration phase during acceleration, thereby producing a quasi-monoenergetic electron beam. The superimposed field produces a localized ionization injection that dominates the measured spectra, while the secondary injection due to other injection mechanisms (such as conventional ionization injection and self-injection of background electrons) is unstable and contributes only marginally. Since most accelerated electrons come from the inner-shell electrons of nitrogen atoms, they are generated by scissor-cross ionization rather than by colliding pulse injection. This allows better control over electron energy and charge.

In conclusion, the scissor-cross ionization injection mechanism has been demonstrated experimentally, which achieves localized ionization injection and addresses the challenge of continuous injection. Various properties of the trigger laser are used to modulate the quality of the electron beam. This mechanism enables reproducible and controllable high-quality electron generation, which is critical for accelerators and advanced photon sources.

Methods

Laser system

The experiment was performed using the 200 TW Ti:sapphire (λ = 800 nm) laser facility at the Laboratory for Laser Plasma in Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The 1.58J p-polarized laser pulse with a duration of \(\tau =30{\mbox{fs}}\) (full width at half maximum, FWHM) is delivered as a driver laser in the experiment. The laser pulse is focused by an f /20 off-axis parabolic (OAP) mirror to a Gaussian-like spot size, containing 30% energy with an FWHM diameter of 28 μm. Thus, the focused laser intensity can reach 2.6 × 1018 W cm−2, corresponding to a normalized vector potential of \({a}_{0}=e{{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\bf{0}}}}}/{m}_{e}{c}^{2}{\mbox{=}}1.25\), where \({{{{\bf{A}}}}}_{{{{\bf{0}}}}}\) is the amplitude of the laser vector potential, e is the elementary charge, me is the classical electron mass, and c is the speed of light in vacuum. A laser pulse with an energy of 0.34 J, tightly focused through an f/2 OAP, serves as the trigger laser. The spot size of the trigger laser is 4 µm in FWHM, resulting in a laser intensity of 2.7 × 1019 W cm−2 and a0 = 3.5.

Readers may note that although Wang et al.21 used a frequency-doubled TL to reduce the ponderomotive disturbance of the TL, the basic requirement of this scheme is that the superimposed electric field exceeds the ionization threshold. In the present work, we achieve this requirement by tightly focusing the TL without frequency-doubling. This choice simplifies the experiment while maintaining the injection mechanism.

Gas target

The supersonic nozzle, with a width of 1.1 mm and a length of 4 mm, can provide well-defined uniform plasma density profiles in the range of 3 × 1017 to 2 × 1019 cm−3. In the experiments, the gas pressure is 0.05 MPa for nitrogen, providing a plasma density of 1.5 × 1018 cm−3, based on the hydrodynamic calculations. For helium, the gas pressure is 0.4 MPa, providing a plasma density of 3.5 × 1018 cm−3 (See Supplementary Note 4).

Diagnostics

The top-view setup, consisting of a 14-bit charge-coupled device (CCD) and a bandpass filter, was used to reveal the interaction position and the time-integrated plasma channel length by monitoring Thomson scattering of the laser beams62. As shown in Fig. 1b, the main laser propagated through the center of the nozzle, while the TL was incident at an angle of 30°.

The electron beam accelerated by LWFA passed through a rectangular dipole magnet of 2 cm × 8 cm × 16 cm, with a central magnetic flux density of 1.1 T63. The two-dimensional distribution in the incident plane of the magnetic field strength was obtained by performing a seven-order polynomial fit of the measured data. Subsequently, the electron bunch bombarded the phosphor screen (Gd₂O₂S:Tb), causing it to emit fluorescence, which was detected by a 16-bit Electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EM-CCD) camera to obtain an electron beam spot image (the phosphor screen was covered with a 14 μm thickness Al film to block stray light). The screen was placed 23.8 cm away from the exit of the magnet to record the deflected electron beam64, and the imaging plate was calibrated for charge calculation65. The basic calibration process of electron charge can be referred in the Supplementary Note 2.

Visualization of electron spectra

We applied a fixed 3 × 3 median filter to remove isolated single-pixel spikes (‘salt-and-pepper’ noise) prior to visualization. In Fig. 2, the colormap was fixed to show the signal value from 0 to 240. For better showing the information, we have set the opacity of 0 (absolutely transparent) for the signal value smaller than 15, and the opacity of 1 (absolutely not transparent) for the signal value larger than 105. The opacity has a linear transition from 0 to 1 for the signal value between 0 and 105.

Particle-in-cell simulations

To simulate the experiment, we have performed Particle-in-Cell simulations using the code WarpX with the quasi-cylindrical coordinate system66,67. The field expression of the TL has been added as the external field, so that the TL can be properly modeled in the quasi-cylindrical geometry. The DL is launched by the regular laser launching mechanism, while the oblique laser is predefined by mathematical expressions of the electromagnetic field. We have verified our method in a series of tests, including: electron ionization, electron injection and electron scattering68. These test results show that the simulation using quasi-cylindrical geometry is consistent with the results of the 3D simulation.

The transverse cell size is dr = 0.215 μm, the longitudinal cell size is dz = 0.0244 μm, and the time step is dt = dz/c, where c is the speed of light in vacuum. The number of azimuthal modes is 4, and the macroparticle number in the azimuthal direction per cell is 8. The DL has a wavelength λ = 800 nm, a normalized amplitude a0 = 1.3, a focal waist radius (where the laser intensity decreases to exp(-2) of the central intensity) w0 = 17 μm and a pulse duration in full-width-half-maximum τFWHM = 30 fs, and the oblique laser has λ = 800 nm, a0 = 3.5, w0 = 2.4 μm and τFWHM = 30 fs. Both the propagation and polarization directions of the two lasers are in the x-z plane, and the two lasers collide at z = 500 μm. The plasma density profile is similar to the gas target used in the experiments, with a plateau region of 3600 µm and linear up and down ramps of 200 µm at both ends. The plasma is pre-ionized with a plateau density of np = 1.5 × 1018 cm−3. In our model, L-shell electrons are pre-ionized and form the background plasma electrons, while K-shell electrons are not pre-ionized. And in helium cases, the electrons are directly set to the ionized state. This is because the helium electrons and the L-shells electrons of nitrogen are pre-ionized by the pre-pulses of the lasers, which have the intensity of the order of 1015 W cm−2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17542489.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this work is available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Strickland, D. & Mourou, G. Compression of amplified chirped optical pulses. Opt. Commun. 56, 219–221 (1985).

Tajima, T. & Dawson, J. M. Laser Electron Accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 43, 267–270 (1979).

Faure, J. et al. A laser–plasma accelerator producing monoenergetic electron beams. Nature 431, 541–544 (2004).

Geddes, C. G. R. et al. High-quality electron beams from a laser wakefield accelerator using plasma-channel guiding. Nature 431, 538–541 (2004).

Mangles, S. P. D. et al. Monoenergetic beams of relativistic electrons from intense laser–plasma interactions. Nature 431, 535–538 (2004).

Rousse, A. et al. Production of a keV X-Ray Beam from Synchrotron Radiation in Relativistic Laser-Plasma Interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 135005 (2004).

Schwoerer, H., Liesfeld, B., Schlenvoigt, H.-P., Amthor, K.-U. & Sauerbrey, R. Thomson-Backscattered X Rays From Laser-Accelerated Electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 014802 (2006).

Wang, W. et al. Free-electron lasing at 27 nanometres based on a laser wakefield accelerator. Nature 595, 516–520 (2021).

Gonsalves, A. J. et al. Petawatt Laser Guiding and Electron Beam Acceleration to 8 GeV in a Laser-Heated Capillary Discharge Waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 084801 (2019).

Aniculaesei, C. et al. The acceleration of a high-charge electron bunch to 10 GeV in a 10-cm nanoparticle-assisted wakefield accelerator. Matter and Radiat. Extremes 9, 014001 (2024).

Picksley, A. et al. Matched Guiding and Controlled Injection in Dark-Current-Free, 10-GeV-Class, Channel-Guided Laser-Plasma Accelerators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 255001 (2024).

Li, Y. F. et al. Generation of 20 kA electron beam from a laser wakefield accelerator. Phys. Plasmas 24, 023108 (2017).

Ke, L. T. et al. Near-GeV Electron Beams at a Few Per-Mille Level from a Laser Wakefield Accelerator via Density-Tailored Plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 214801 (2021).

Zhu, X. et al. Experimental Demonstration of Laser Guiding and Wakefield Acceleration in a Curved Plasma Channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 215001 (2023).

Winkler, P. et al. Active energy compression of a laser-plasma electron beam. Nature 640, 907–910 (2025).

Davoine, X., Lefebvre, E., Rechatin, C., Faure, J. & Malka, V. Erratum: Cold Optical Injection Producing Monoenergetic, Multi-GeV Electron Bunches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 065001 (2009).

Geddes, C. G. R. et al. Plasma-Density-Gradient Injection of Low Absolute-Momentum-Spread Electron Bunches. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 215004 (2008).

Zeng, M., de la Ossa, A. M. & Osterhoff, J. Ponderomotively assisted ionization injection in plasma wakefield accelerators. N. J. Phys. 22, 123003 (2020).

Vieira, J. et al. Magnetic Control of Particle Injection in Plasma Based Accelerators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 225001 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Injection induced by coaxial laser interference in laser wakefield accelerators. Matter Radiat. Extremes 7, 054001 (2022).

Wang, J., Zeng, M., Wang, X., Li, D. & Gao, J. Scissor-cross ionization injection in laser wakefield accelerators. Plasma Phys. Controll. Fusion 64, 045012 (2022).

Chen, M., Sheng, Z.-M., Ma, Y.-Y. & Zhang, J. Electron injection and trapping in a laser wakefield by field ionization to high-charge states of gases. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 056109 (2006).

Oz, E. et al. Ionization-Induced Electron Trapping in Ultrarelativistic Plasma Wakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 084801 (2007).

McGuffey, C. et al. Ionization Induced Trapping in a Laser Wakefield Accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 025004 (2010).

Chen, M., Esarey, E., Schroeder, C. B., Geddes, C. G. R. & Leemans, W. P. Theory of ionization-induced trapping in laser-plasma accelerators. Phys. Plasmas 19, 033101 (2012).

Clayton, C. E. et al. Self-Guided Laser Wakefield Acceleration beyond 1 GeV Using Ionization-Induced Injection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 105003 (2010).

Pak, A. et al. Injection and Trapping of Tunnel-Ionized Electrons into Laser-Produced Wakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 025003 (2010).

Döpp, A. et al. Stable femtosecond X-rays with tunable polarization from a laser-driven accelerator. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e17086 (2017).

Guo, B. et al. High-resolution phase-contrast imaging of biological specimens using a stable betatron X-ray source in the multiple-exposure mode. Sci. Rep. 9, 7796 (2019).

Guo, B. et al. Enhancement of laser-driven betatron x-rays by a density-depressed plasma structure. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 61, 035003 (2019).

Thaury, C. et al. Shock assisted ionization injection in laser-plasma accelerators. Sci. Rep. 5, 16310 (2015).

Zeng, M., Chen, M., Sheng, Z.-M., Mori, W. B. & Zhang, J. Self-truncated ionization injection and consequent monoenergetic electron bunches in laser wakefield acceleration. Phys. Plasmas 21, 030701 (2014).

Mirzaie, M. et al. Demonstration of self-truncated ionization injection for GeV electron beams. Sci. Rep. 5, 14659–14659 (2015).

Couperus, J. P. et al. Demonstration of a beam loaded nanocoulomb-class laser wakefield accelerator. Nat. Commun. 8, 487 (2017).

Golovin, G. et al. Tunable monoenergetic electron beams from independently controllable laser-wakefield acceleration and injection. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 18, 011301 (2015).

Pollock, B. B. et al. Demonstration of a Narrow Energy Spread, ∼0.5 GeV Electron Beam from a Two-Stage Laser Wakefield Accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 045001 (2011).

Liu, J. S. et al. All-Optical Cascaded Laser Wakefield Accelerator Using Ionization-Induced Injection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 035001 (2011).

Kirchen, M. et al. Optimal Beam Loading in a Laser-Plasma Accelerator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 174801 (2021).

Umstadter, D., Kim, J. K. & Dodd, E. Laser Injection of Ultrashort Electron Pulses into Wakefield Plasma Waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 2073–2076 (1996).

Esarey, E., Hubbard, R. F., Leemans, W. P., Ting, A. & Sprangle, P. Electron Injection into Plasma Wakefields by Colliding Laser Pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 2682–2685 (1997).

Sheng, Z.-M. et al. Stochastic Heating and Acceleration of Electrons in Colliding Laser Fields in Plasma. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 055004 (2002).

Faure, J. et al. Controlled injection and acceleration of electrons in plasma wakefields by colliding laser pulses. Nature 444, 737–739 (2006).

Kotaki, H. et al. Electron Optical Injection with Head-On and Countercrossing Colliding Laser Pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 194803 (2009).

Bourgeois, N., Cowley, J. & Hooker, S. M. Two-Pulse Ionization Injection into Quasilinear Laser Wakefields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 103510 (2013).

Yu, L.-L. et al. Two-Color Laser-Ionization Injection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 125001 (2014).

Zeng, M. et al. Multichromatic Narrow-Energy-Spread Electron Bunches from Laser-Wakefield Acceleration with Dual-Color Lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 084801 (2015).

Li, Z., Leng, Y. & Li, R. Further Development of the Short-Pulse Petawatt Laser: Trends, Technologies, and Bottlenecks. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2100705 (2023).

Kim, D. Y. et al. Optical synchronization technique for all-optical Compton scattering. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 93, 113001 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. MeV-Energy X Rays from Inverse Compton Scattering with Laser-Wakefield Accelerated Electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 155003 (2013).

Yan, W. et al. High-order multiphoton Thomson scattering. Nat. Photonics 11, 514–520 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Transient Relativistic Plasma Grating to Tailor High-Power Laser Fields, Wakefield Plasma Waves, and Electron Injection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 164801 (2022).

Golovin, G. et al. Electron Trapping from Interactions between Laser-Driven Relativistic Plasma Waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 104801 (2018).

Von der Leyen, M. W. et al. Observation of Monoenergetic Electrons from Two-Pulse Ionization Injection in Quasilinear Laser Wakefields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 105002 (2023).

Hidding, B. et al. Progress in Hybrid Plasma Wakefield Acceleration. Photonics 10, 99 (2023).

Deng, A. et al. Generation and acceleration of electron bunches from a plasma photocathode. Nat. Phys. 15, 1156–1160 (2019).

Yang, L., Deng, Z. G., Yu, M. Y. & Wang, X. G. High-charge energetic ions generated by intersecting laser pulses. Phys. Plasmas 23, 083106 (2016).

Zhang, Y. X. et al. Giant Isolated Attosecond Pulses from Two-Color Laser-Plasma Interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 114802 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Controllable Terahertz Radiation from a Linear-Dipole Array Formed by a Two-Color Laser Filament in Air. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 243901 (2016).

Zhang, L.-L. et al. Observation of Terahertz Radiation via the Two-Color Laser Scheme with Uncommon Frequency Ratios. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 235001 (2017).

Chen, S. et al. A platform for all-optical Thomson/Compton scattering with versatile parameters. High. Pow. Laser Sci. Eng. 13, e56 (2025).

Grafenstein, K. V. et al. Laser-accelerated electron beams at 1 GeV using optically-induced shock injection. Sci. Rep. 13, 11680 (2023).

Hussein, A. E. et al. Stimulated Raman backscattering from a laser wakefield accelerator. N. J. Phys. 20, 073039 (2018).

Lu, G.-W. et al. Divergence angle consideration in energy spread measurement for high-quality relativistic electron beam in laser wakefield acceleration. Chin. Phys. B 33, 064101 (2024).

Rabhi, N. et al. Calibration of imaging plate detectors to mono-energetic protons in the range 1-200 MeV. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 113301 (2017).

Williams, G. J., Maddox, B. R., Chen, H., Kojima, S. & Millecchia, M. Calibration and equivalency analysis of image plate scanners. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85, 11E604 (2014).

Lehe, R., Kirchen, M., Andriyash, I. A., Godfrey, B. B. & Vay, J.-L. A spectral, quasi-cylindrical and dispersion-free Particle-In-Cell algorithm. Comput. Phys. Commun. 203, 66–82 (2016).

Vay, J.-L. et al. Modeling of a chain of three plasma accelerator stages with the WarpX electromagnetic PIC code on GPUs. Phys. Plasmas 28, 023105 (2021).

Ma, M. et al. Particle-in-cell simulation of laser wakefield accelerators with oblique lasers in quasicylindrical geometry. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 28, 021301 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Project supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFA1601700), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB0530000, Grants No. XDA25010500 and No. XDA25010100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12074251, 11991073, 12225505, 12475159), Al for Science Program, Shanghai Municipal Commission of Economy and Informatization (Grand No. 2025-GZL-RGZN-BTBX-02029). We thank the sponsorship from Yangyang Development Fund, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C., W.Y., X.H., M.Zh., M.Z., H.X., J.J., Z.Y., H.M., Z.Z. and R.L. planed and designed the overall experiment. G.L., W.Y., M.Z., D.L., M.M., S.C. and X.H. performed the numerical simulations. G.L., W.Y., M.Z., D.L., J.W., S.C., M.W., M.M. and X.H. discussed all experimental and numerical results. F.L. and B.L. operated and maintained the laser system. W.Y., M.C. and M.Z. provided funding for the experiment and simulation. G.L., S.C., M.Z., W.Y. and B.L. drafted and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Lu, G., Hu, X. et al. Demonstration of scissor-cross ionization injection in laser wakefield accelerators. Commun Phys 9, 9 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02440-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02440-3