Abstract

Creating a structured transverse-intensity distribution that undergoes axial rotation during propagation while preserving its overall shape remains a major challenge, as achieving a stable, continuous, and substantial rotation across the entire beam cross-section has thus far proven elusive. Here, we introduce a class of intensity-rotating structured beams generated by diffracting a plane wave through a purely amplitude-based spiral-like structure composed of curved radial spokes, periodic in both radial and azimuthal directions. The diffraction patterns form concentric rings with petal-like intensity spots, whose number and spacing are set by the spoke count. Spoke curvature, L, induces relative azimuthal shifts between rings, producing a global rotation around the optical axis during propagation. Increasing L by an order of magnitude yields measurable rotations over 10−2 of the initial propagation length, enabling faster rotations at shorter distances. Simultaneously, the beam divergence decreases, evolving toward a quasi-non-diffractive regime. The spots trace spiral trajectories reminiscent of galactic arms, inspiring the term galactic-form spinning beams. Phase analysis shows vortex-like azimuthal variations with topological charge equal to the spoke number. Numerical and experimental results confirm these dynamics, offering opportunities for structured-light applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical beams are light waves characterized by well-defined spatial and temporal coherence, propagating through free space or various media in forms such as directed, focused, or collimated beams. As foundational tools in modern optics, coherent beams including lasers have enabled diverse applications spanning communications1,2, medical imaging3,4, and material processing5. In recent decades, variety of classes of structured beams-exhibiting engineered intensity, phase, and polarization distributions-have drawn considerable interest in the optics and laser communities. These complex field distributions enable a variety of propagation behaviors, such as beam acceleration, self-healing, diffraction resistance, and localized amplification. For example, in radial carpet beams (RCBs), self-amplification occurs in the core region by redistributing power from the pattern-less central zone into the surrounding structured area during propagation6,7.

Structured beams are essential in advanced microscopy methods, such as confocal, light-sheet, and super-resolution imaging8,9,10,11,12,13. Additionally, Bessel beams and RCBs play key roles in optical trapping, enabling the manipulation of microscopic particles and biological cells14,15.

The generation and application of optical beams have been central topics in photonics and laser physics. As solutions to the wave equation, beam behavior varies with boundary conditions. Bessel, Laguerre-Gaussian, and Hermite-Gaussian beams (whose fundamental mode reduces to a Gaussian beam) each differ in their intensity, phase, and propagation characteristics and can be generated within laser cavities determined by cavity geometry16.

Recent advances in optical engineering have enabled the generation of complex beams via diffraction techniques17,18. In these approaches, diffractive elements impose specific boundary conditions on simple sources, such as Gaussian or plane waves, to produce structured fields. For example, high-order Laguerre-Gaussian beams are generated by diffracting Gaussian beams through multi-circle phase-shifted amplitude fork gratings19, and Bessel beams via axicons or ring-shaped apertures20,21. Similarly, RCBs are produced by passing a plane wave through radial amplitude/phase structures, creating intricate diffraction patterns that merge near-field and far-field behaviors6,22,23. These methods have led to recently developed beam types, such as half-integer Bessel-like beams24.

Among the various families of structured beams, those whose intensity profiles rotate during propagation have attracted considerable research attention. Such rotational dynamics might provide additional functional capabilities, potentially enabling advanced optical manipulation14,15, such as trapping with controllable displacement of particles along the propagation axis accompanied by rotation, as well as applications in free-space optical communication25 and high-resolution imaging10,11.

Several works have explored the concept of intensity-rotating beams. However, many of these either remain theoretical-with negligible observed rotation-or display unstable intensity profiles during propagation. In ref. 26, rotating beams were proposed using on-axis interference between Laguerre-Gaussian and vortex Bessel beams with frequency shifts. A rotating Hermite-Gaussian beam was obtained by superposing frequency-shifted modes LG0,1 and LG0,−1, while rotating Bessel beams arose from similar superpositions of vortex Bessel modes. Likewise,27 introduced a configuration combining two vortex beams with opposite azimuthal indices, primarily for analyzing particle dynamics. However, such approaches lack experimental realization.

The rotation of Hermite-Gaussian beam patterns depends on the beam waist and wavelength, rather than a fixed distance, and is best described using normalized propagation distance z/zR, where zR is the Rayleigh range26. Rotation is observed in the far field (z/zR ≳1); for instance, a 180° rotation may appear at z ≈ 6 × 105 cm for a beam waist of b = 0.3 mm. Higher topological charges reduce rotational displacement for the same distance. While the effect exists, it is minimal over practical propagation ranges. Moreover, generating such beams requires precise alignment of optical elements, such as fork gratings, spiral zone plates (SZPs), or spatial light modulators. Even slight misalignment can result in mode mismatch and power loss. These beams also suffer from structural expansion and divergence during propagation, limiting their utility.

Although Bessel vortex beams are diffraction-free, their rotational intensity profile exhibits only marginal evolution during propagation, much like Hermite-Gaussian beams. Many theoretical and experimental studies have investigated rotating beams formed through superposition with tailored phase differences28,29,30,31,32. However, these methods typically produce rotation over limited distances and require careful mode selection to maintain beam integrity. Moreover, the superposition approach demands complex optical setups, increasing system cost and reducing efficiency.

In other approaches, rotation emerges from vortex phase structures, but typically remains limited to within 180°, as shown in simulations of vortex beams reflecting in free space33. Larger rotations are possible with asymmetric Laguerre-Gaussian mode combinations34, and even more complex behaviors, such as combined rotation and revolution-have been demonstrated using spatiotemporal beam shaping with frequency combs and orbital angular momentum engineering35. Yet, these methods depend heavily on frequency manipulation and multi-beam interference.

In a recent study36, a combined diffractive optical element was employed to generate rotating diffraction patterns with triangular distributions. These patterns exhibited a progressive change in their apex angle, increasing from nearly zero to 30 degrees over a propagation distance of 1.5 m. The diffraction pattern rotated around the optical axis by an angular amount of 90 degrees over the same distance. Despite the rotation, the diffraction pattern did not maintain a beam shape. Due to the considerable expansion of its apex angle, the pattern underwent substantial transformation over further propagation, with its form changing noticeably as the apex angle increased.

Despite the progress achieved in earlier approaches26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, most reported rotating beams either suffer from negligible rotation26,33,36, require complex superposition of multiple modes28,29,30,31,32 that demand delicate interferometric alignments prone to instability, or remain purely theoretical without practical implementation26,27. Even when experimentally attempted, these beams often diverge during propagation and exhibit unstable or weakly rotating intensity profiles28,29,30,36, as elaborated in the preceding discussion. Such limitations severely restrict their practical applicability in optical manipulation, imaging, and free-space communication.

In contrast, this study presents a simple approach based on diffraction of a plane wave from a pure amplitude diffractive element having spiral-like structure (SLS) composed of curved spokes with dual radial and azimuthal periodicity. Unlike radial gratings having straight spokes, the SLS lines curve systematically outward, forming spiral paths. This curvature introduces a structural phase twist, generating beams with rotating, localized high-intensity spots-main intensity spots (MISs)-without relying on multi-mode interference. These beam-like patterns (BLPs) exhibit vortex phase characteristics and carpet-like radial intensity distributions, combining structural complexity with propagation stability.

Our analysis and experiments reveal that the vortex phase originates from the spoke curvature, while the radial carpet-like intensity results from periodicity in both radial and azimuthal directions-a property absent in SZPs. Thus, SLSs can produce rotating vortex radial carpet-like beams. The resulting beams exhibit reduced divergence and even local amplification. Particles trapped in MISs may undergo axial motion, orbital rotation, and orbital angular momentum transfer, potentially enabling inter-spot hopping-a behavior not reported before.

The diffraction patterns consist of concentric rings populated with petal-like spots, whose number and rotation dynamics are governed by the SLS curvature rate. The rotating spots trace helical paths around a dark central region, forming a three-dimensional structure reminiscent of a spiral galaxy-thus inspiring the term “galactic-form spinning beams.”

The proposed SLS method offers a simple, low-cost, single-element, pure-amplitude solution that is easy to implement experimentally, while at the same time enabling robust rotational dynamics, reduced divergence, and localized amplification over practical propagation distances. Furthermore, by tuning the structural parameters of the SLS, the degree of rotation can be precisely controlled and tailored to specific applications, with the rotational behavior preserved over considerable propagation ranges.

Results and Discussion

Transmission function of SLSs

We define the pure-amplitude transmission functions of SLSs exhibiting dual periodicity in both radial and azimuthal directions. These functions are modeled using sinusoidal and binary profiles, as described below:

where m denotes the number of spokes in the structure, r and θ are the radial and azimuthal polar coordinates, respectively, sgn is the signum function, and L is a curvature parameter that governs the azimuthal advancement of the spokes per unit radial distance. This parameter has units of inverse length and is expressed in mm−1, consistent with the centimeter-scale dimensions of the fabricated SLS samples.

By tuning the value of L, the curvature of the spokes can be precisely controlled. It is noteworthy that Eqs. (1) and (2) are periodic in θ for fixed r, and periodic in r for fixed θ, thus exhibiting a dual-periodic nature in both coordinates.

To illustrate this property, Fig. 1a, d display the spatial amplitude patterns of the sinusoidal and binary SLSs, respectively, for the parameters m = 30 and L = 5 mm−1. The corresponding one-dimensional (1D) profiles along the radial and azimuthal directions are presented in Fig. 1b, c for the sinusoidal SLS, and in Fig. 1e, f for the binary SLS.

In Fig. 2, we present various examples of SLSs with m = 10 and m = 30, featuring sinusoidal profiles. As evident from the figures, increasing the value of L results in greater curvature of the spokes in the structure. When L = 0 mm−1, the structure reduces to the radial grating as described in refs. 6,22. Additional examples, including binary profiles and further variations of L, are shown in Fig. S1 and detailed in Supplementary Note 1.

a Sinusoidal amplitude radial grating and SLSs with m = 10, b sinusoidal amplitude structures with m = 30, for various values of L. i corresponds to radial gratings, while ii–iv correspond to SLSs. Additional examples, including binary profiles and further variations of L, are provided in Fig. S1.

In Fig. 3, we compare different SLSs and radial gratings to highlight the curvature degree of the SLSs’ lines. i displays the radial gratings with a binary profile for m = 10 and m = 30. ii show the SLSs using Eq. (2) for L = 1 mm−1 and L = 2 mm−1. iii illustrate the superimposition of thinned dark spokes/lines from the structures in panels (i) and (ii). Intersection points between the radial grating spokes and SLS lines are highlighted with dashed-line circles.

a m = 10, L = 1 mm−1; b m = 10, L = 2 mm−1; c m = 30, L = 1 mm−1. The superimposition of thinned dark spokes/lines from the structures in i and ii is shown in (iii). Intersection points between the radial grating spokes and SLS lines are highlighted with dashed-line circles. An SLS with m = 30, L = 2 mm−1 is presented in Fig. S2.

As illustrated in Panel (iii) of Fig. 3a, each line of the SLS intersects the adjacent spoke of the radial grating on the first circle at radius r1 = 1 cm, reaches the next spoke on the second circle at radius r2 = 2 cm, and superimposes on the third spoke on the third circle at radius r3 = 3 cm, and so on. In Fig. 3b, as L increases from 1 to 2, the curvature of the lines also increases. Here, each line of the SLS intersects the adjacent radial grating spoke on the first, second, and third circles at radii of r1 = 0.5 cm, r2 = 1 cm, and r3 = 1.5 cm, respectively, which are half of the values for L = 1 mm−1. As L increases to values of 3, 4, 5, … , the radii r1, r2, and r3 decrease proportionally to 1/3, 1/4, 1/5 of the corresponding values for L = 1 mm−1.

Furthermore, as the number of spokes in the radial grating, m, increases from 10 to 30, Fig. 3(c) for L = 1 mm−1 and Fig. S2(d) for L = 2 mm−1 illustrate the corresponding changes in r1, r2, and r3. For L = 1 mm−1, the values are r1 = 3 cm, r2 = 6 cm, and r3 = 9 cm; for L = 2 mm−1, the values are r1 = 1.5 cm, r2 = 3 cm, and r3 = 4.5 cm. Therefore, the radii of the intersection circles can be expressed by the following simple relation:

where n denotes the index of the intersection circle, m is the number of spokes, and L is the curvature parameter that governs the angular variation of the SLS lines per unit radial distance. The parameter L has units of inverse length.

Diffraction of a Plane Wave by an SLS

As a reference case, Fig. 4a shows the diffraction pattern generated by an amplitude sinusoidal radial grating with parameters m = 10, L = 0 mm−1, which corresponds to an RCB, numerically obtained using the angular spectrum method (angular spectrum method is presented in Methods). Subsequently, Fig. 4b–d illustrate the diffraction patterns produced by SLSs with parameters m = 10, L = 5, 10 mm−1 and m = 30, L = 5 mm−1, respectively. Additional details for the case m = 10, L = 1 mm−1 are provided in Fig. S3 and discussed in Supplementary Note 2.

a A radial grating and the resulting RCB under propagation. b–d three SLSs with different m and L, along with the corresponding beam-like patterns (BLPs) during propagation. b, c display diffraction patterns of concentric rings populated with petal-like spots whose number and rotation are governed by the curvature of the SLS. Dynamic visualizations of b, c are provided in Supplementary Movie 1. Diffraction patterns through the SLS with m = 10 and L = 1 mm−1 is presented in Fig. S4. These spots follow helical paths around a central dark core, forming a Three-dimensional (3D) structure akin to a spiral galaxy-hence the term galactic-form spinning beams. One of the main intensity spots (MISs) in panels (b), (c), and (d) is highlighted with a light blue circle to track the rotation. e–h 3D trajectories of MISs resembling the grooves of a mechanical drill, referred to here as optical drills. h, i show y-z cross-sections of the intensity distributions corresponding to (b, c), respectively. (See also Supplementary Movies 1-3).

To track the rotation of the diffraction patterns, one of the MISs in (b–d) is highlighted with a light blue circle. The figure clearly demonstrates that the MISs’ positions shift both azimuthally and radially as the wave propagates, leading to an expansion of the diffraction pattern accompanied by rotation around the optical axis.

The results indicate that, increasing the curvature of the lines (larger L) and reducing the number of spokes (m) results in greater rotation. Additionally, these changes reduce the radial expansion of the central pattern-less region, which is proportional to the radial position of the MISs. Our analysis shows that diffraction from SLSs generates rotating BLPs that closely resemble RCBs. Over varying propagation distances, the core region of the BLPs rotates around the optical axis, with the central spots maintaining an almost shape-invariant structure during rotation. These distinctive rotational properties have led us to refer to the MISs as ’optical drills.’ The degree of rotation varies with the curvature of the spokes in the SLS structure. For further insight, see Supplementary Movie 1.

In Fig. 4f, g, we present 3D visualizations of the MIS trajectories, which resemble optical drills, to highlight the rotational dynamics of BLPs during propagation. These trajectories are derived from diffraction patterns with m = 10, L = 5 mm−1 and m = 10, L = 10 mm−1, as shown in Fig. 4b, c. For comparison, Fig. 4e shows the propagation trajectory of the MISs for the RCB, which demonstrates no rotational behavior along the propagation axis. The analysis spans a propagation distance from z = 1 m to z = 25 m.

As illustrated in Fig. 4b–d, f, g the parameter L significantly influences the rotation of BLPs. Higher values of L enhance rotational dynamics while reducing divergence during propagation. Specifically, in Fig. 4b, f, and Supplementary Movie 2 (see part (a)), the MISs complete approximately one full turn around the propagation axis over a distance of 25 m. Conversely, in Fig. 4c, f, and Supplementary Movie 2 (see part (b)), the MISs complete approximately three full turns over the same propagation distance. Additionally, in Supplementary Movie 3, more pronounced rotational features are observed for smaller values of m, analyzed for two different values of L. For instance, for m = 2 and L = 3 mm−1, the MISs complete approximately seven full turns over a 6 m propagation distance. To provide a clearer view of the beam evolution and divergence characteristics during propagation, longitudinal cross-sections (in the y-z plane) of the intensity distributions corresponding to Fig. 4b, c are shown in Fig. 4h, i, respectively. These slices complement the 3D and transverse intensity profiles, offering additional insight into the beam’s propagation dynamics.

To further elucidate the characteristics of the BLPs, detailed transverse intensity and phase distribution-along with their corresponding wrapped and unwrapped representations of phase profiles around a circular trajectory of MISs-are illustrated in Fig. 5 and Fig. S4. Figure 5a shows the intensity and phase structure of the RCB at z = 25 m, serving as a baseline for comparison with the vortex phase structures observed in the rotating BLPs, and providing further insight into the underlying cause of their rotational behavior. Specifically, the transverse intensity distribution of the RCB generated by amplitude sinusoidal radial grating with the parameters m = 10 and L = 0 mm−1, is shown in Fig. 5a1, while Fig. 5a2 provides an enlarged view of one of the MISs and its surrounding region. The corresponding phase distributions related to these intensity patterns are displayed in Fig. 5a3, a4, respectively. The internal phase structure of the MISs is highlighted in Fig. 5a5. Finally, Fig. S4(a6) presents both the wrapped and unwrapped phase profiles along a circular trajectory surrounding the MIS, further clarifying the phase characteristics associated with the non-rotating beam.

a Simulated intensity and phase distributions of an RCB at z = 25 m, generated by a sinusoidal radial grating with m = 10. a1 Intensity distribution; a2 enlarged view of one of the main intensity spots (MISs) and its surrounding region; a3, a4 simulated phase distributions corresponding to the intensity patterns in (a1) and (a2), respectively; a5 phase distribution of the MISs. b Intensity and phase distributions of BLPs generated by an SLS with m = 10 and L = 5 mm−1 under propagation. b1 Intensity distribution; b2 enlarged view of an MIS and its surroundings; b3, b4 corresponding phase distributions; b5 phase distribution of the MISs. i–v illustrate the evolution of these patterns during propagation. c same as (b), but for an SLS with m = 10 and L = 10 mm−1, evaluated at z = 25 m. For dynamic visualizations of phase evolution in the cases with m = 10 and L = 10 mm−1, see Supplementary Movie 4. Wrapped and unwrapped phase profiles along a circular path across the MISs for all cases in (a)-(c), as well as a comparison with an SLS defined by m = 20 and L = 10 mm−1, are provided in Fig. S4.

Figure 5b provides an overview of the intensity and phase structure of the BLPs generated by an SLS with m = 10 and L = 5 mm−1, illustrating the complex vortex features associated with their rotational propagation dynamics. In detail, Fig. 5b1 show BLPs resulting from SLS with m = 10 and L = 5 mm−1 during a propagation distance of z = 25 m. Enlarged view of one of MISs and its surrounding area are provided in Fig. 5b2, phase distributions corresponding to the intensity patterns in Fig. 5b1, b2 shown in Fig. 5b3, b4, respectively. Corresponding phase distribution and wrapped and unwrapped phase profile of MISs over circular trajectory are plotted in Fig. 5b5 and Fig. S4(b6). Figure 5b5 and Fig. S4(b6) show that the phase structure of the MISs in the inner ring, covering the range from − π to π, is fully established after a propagation distance of z = 1 m. The corresponding phase analysis for the diffraction of a plane wave through an SLS with m = 10 and L = 10 mm−1 is shown in Fig. 5c, specifically in panels (c1) to (c5), at a propagation distance of z = 25 m, while the wrapped and unwrapped phase profiles are provided in Fig. S4(a6). The unwrapped phase profile in this case is compared with that obtained for an SLS with the same L = 10 mm−1 but a higher spoke number m = 20, illustrated in Figs. S4(d) and S4(e) at different propagation distances. As seen, the phase analyzes of rotating BLPs reveal that each concentric MISs ring carries an azimuthal varying phase profile with a topological charge equal to the number of spokes. These visualizations, shown for various SLS configurations and propagation distances, provide deeper insight into the vortex phase structure of the MISs and their evolution along the optical axis. For dynamic visualization of the phase evolution during propagation, readers are referred to Supplementary Movie 4.

As shown in Fig. 4b, c, the central diffraction pattern exhibits a propagation-invariant intensity profile with a distinct rotational behavior. This stationary intensity region initially forms around the MISs and progressively extends to larger radii as the beam propagates. For instance, after a propagation distance of 5 meters in Fig. 4c, the entire displayed window maintains a nearly invariant structure.

Further illustrated in panels (b) and (c) of Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, these diffraction patterns feature concentric rings filled with petal-like intensity spots. The number and rotational dynamics of these spots are directly governed by the curvature rate of the SLS spokes. As the beam advances, the spots first appear in the inner rings and gradually populate the outer ones, while the entire structure rotates uniformly around the optical axis-resembling the coherent motion of galactic matter.

During propagation, the intensity spots trace helical paths around a central dark core, collectively forming a 3D structure reminiscent of spiral galaxy arms. This feature motivates the designation of these beams as ’galactic-form spinning beams’ (see Supplementary Movies 1 and 4).

This rotational behavior can be physically understood from the geometry of the SLS. The spiral curvature of its spokes introduces a structural phase twist into the diffracted wavefront, analogous to the effect observed in SZPs, and this twist drives the rotation of the intensity spots during propagation. In contrast, RCBs generated by diffraction from radial gratings with straight spokes exhibit no such rotation, since their geometry lacks curvature. The rotating carpet-like intensity distribution produced by SLSs arises from the combination of radial and azimuthal periodicity-a geometric feature absent in conventional SZPs. This interplay between phase twisting and radial periodicity leads to the stable rotation of localized high-intensity spots without the need for multi-mode interference, as demonstrated by the simulated intensity and phase distributions in Fig. 5.

Comparison of Diffraction Patterns of SLSs and SZPs

A Fresnel zone plate (FZP) is a diffractive optical element that mimics the focusing behavior of a conventional lens. Unlike traditional lenses that rely on refraction, the FZP focuses light through the constructive interference of diffracted waves1. It consists of a series of concentric zones specifically designed so that the transmitted waves converge coherently at a desired focal point. By incorporating a helical phase singularity into the FZP’s transmission function, a generalized form known as the spiral zone plate (SZP) is realized37.

The transmission functions of pure amplitude SZPs-whether sinusoidal or binary-can be described using the same equations as those for SLSs, namely Eqs. (1) and (2), with the exception that the argument \(\left(m\theta +\frac{2\pi rL}{m}\right)\) is replaced by \(\left(\ell \theta +\frac{\pi {r}^{2}}{\lambda f}\right)\), where ℓ denotes the topological charge and f is the focal length.

It is important to note that while the SZP in ref. 37 employs a pure phase transmission function, the SZP considered here-illustrated in Fig. 6a-is based on amplitude modulation.

a Transmittance of an SZP with topological charge ℓ = 3. b, c present one-dimensional cross-sectional profiles of the SZP in the radial and azimuthal directions, plotted at θ = π/4 rad and r = 3 mm, respectively. d Simulated diffraction pattern resulting from a plane wave diffraction through the SZP shown in (a). See also Supplementary Movie 5 for the full propagation dynamics.

Furthermore, unlike the SZP’s phase or amplitude transmission function, which exhibits a quadratic dependence on the radial coordinate (r2), the transmission function of SLSs given by Eqs. (1) and (2) is linearly dependent on r. This fundamental difference leads to distinct spatial modulations on the incident beam and results in markedly different diffraction patterns and beam dynamics.

The azimuthal phase term ℓθ in the SZP’s transmittance imparts orbital angular momentum (OAM) to the transmitted beam, with the beam acquiring a topological charge equal to ℓ. A representative SZP designed for ℓ = 3 is shown in Fig. 6a, with its radial and azimuthal profiles depicted in Fig. 6b, c. The resulting diffraction pattern, calculated using the same method as in the previous section, is shown in Fig. 6d. As evident, diffraction from the SZP maintains the focusing behavior of a conventional zone plate while also generating an optical vortex, characterized by a central phase singularity and an annular intensity distribution (see also Supplementary Movie 5).

In contrast, the SLS structure features uniformly spaced radial lines and periodicity in both radial and azimuthal directions. This dual-directional periodicity enables the formation of vortex rotating RCBs-referred to here as ’galactic-form spinning beams’-which the SZP cannot replicate due to its lack of such structural double-periodicity.

Moreover, the diffraction pattern generated by the SLS remains structurally stable during propagation, exhibiting a rotating intensity distribution accompanied by a twisted phase profile. In contrast, the diffraction pattern from the SZP undergoes rapid structural changes as it propagates, eventually forming a ring-shaped intensity distribution at the focal plane. Despite these distinct behaviors, both diffraction patterns share a common attribute: a helical phase structure that imparts rotational characteristics to the transmitted beam.

Experimental Results and Comparison with Simulations

In Fig. 7, both experimental and simulation results are presented for the diffraction of a plane wave through pure amplitude SLSs with a sinusoidal profile for m = 10 and varying values of L. By tracking the position of one of the MISs of the BLPs during propagation from z = 1 m to z = 5 m, we observe that increasing L results in greater rotation of the BLPs. For further illustration, refer to Supplementary Movies 6-7.

a, d show Transmittance of two different SLSs with sinusoidal amplitude profiles and parameters m = 10 and L = 5, 10 mm−1. An inset in panel (d) shows a zoomed-in view to better illustrate the curvature details. b, c show the simulated and experimentally recorded diffraction patterns under propagation when a plane wave passes through the structure in (a). e, f present the corresponding patterns for the structure in (d). One of the main intensity spots (MISs) in (b), (c), (e), and (f) is highlighted with a white circle to track the rotation. Refer to Supplementary Movies 6 and 7 for further details.

The same analysis is applied to sinusoidal and binary amplitude SLSs with m = 30 and m = 20 in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. These configurations exhibit less beam rotation compared to m = 10. However, as in the previous case, increasing L consistently leads to a more pronounced rotation of the BLPs. Additional Supplementary Movies 8-9 are provided to enhance comprehension.

a and d show the transmittance maps of two SLSs designed with sinusoidal amplitude profiles and curvature parameters L = 5, 10 mm−1. d includes a magnified view to resolve fine structural details. b, c present the corresponding simulated and experimental diffraction patterns under plane wave illumination for the structure in (a), while e, f display the patterns for the structure in (d). A main intensity spot (MIS), marked by a white circle, is tracked in each case to illustrate the rotation dynamics. Further visualization of these effects is available in Supplementary Movie 8.

In Figs. 7-9, the experimental measurements consistently confirm the simulated rotational dynamics of the MISs. By tracking the position of one of the MISs during propagation from z = 1 m to z = 5 m, the recorded rotations for L = 5 mm−1 are approximately 67° for m = 10, 22.5° for m = 20 (binary structure), and 13° for m = 30. For L = 10 mm−1, the rotations increase to 173° for m = 10, 45.5° for m = 20, and 23.5° for m = 30, with simulations reproducing these values with high accuracy. This clearly illustrates that the angular rotation of the BLPs decreases with increasing m and increases with larger L.

a, d present the transmittance of two binary SLSs with curvature parameters L = 5, 10 mm−1. An enlarged view in (d) reveals detailed structural features. The simulated and experimental diffraction patterns under a plane wave illumination are shown in panels (b) and (c) for the structure in panel (a), while e, f show the corresponding patterns for the structure in (d). The rotational evolution of a selected main intensity spot (MIS) is indicated by a white circle. The complete propagation dynamics are provided in Supplementary Movie 9.

For further illustration and comparison, Supplementary Movie 10 presents the experimental propagation of BLPs generated by sinusoidal and binary SLSs with m = 10 and L = 5 mm−1. The results clearly show that both configurations exhibit the same angular rotation of the central MIS over the same propagation distance.

A detailed analysis of the rotational dynamics and divergence characteristics is provided in Supplementary Note 3 (Rotational Dynamics and Minimal Divergence of the Generated Beams). As shown in Figs. S5(a) and S5(b), for the same number of lines (m = 10) and different curvatures (L), the divergence of the BLP decreases as the curvature increases, while the rotation becomes more pronounced during propagation. In contrast, Figs. S5(c) and S5(d) illustrate that for a fixed curvature (L), increasing m leads to greater divergence and reduced rotation. Furthermore, as demonstrated in panels (b), (c), (h), and (i) of Fig. 4, the beams generated by SLSs with small m and large L preserve their rotating carpet-like structures with negligible divergence even after 25 m of free-space propagation, confirming their quasi-non-diffractive behavior. These results indicate that, the extent of the quasi-non-diffractive regime is determined by the interplay between the structural parameters m and L. Additional visualization of these dynamics is provided in Supplementary Movies 11-12, where Supplementary Movie 11 corresponds to SLSs with m = 10 and varying L = 5, 10, 15, 20 mm−1, and Supplementary Movie 12 corresponds to SLSs with L = 10 mm−1 and varying m.

The quantitative dependence of rotation on these parameters is summarized in Table S1, which lists the rotation values for the BLPs corresponding to m = 2, 3, 4, 5 and L = 1, 3, 5 mm−1. As observed, the rotation increases with larger curvature L for a fixed m, while higher m values lead to reduced angular rotation. Among the examined cases in Table S1 with m = 2, 3, 4, 5 and L = 1, 3, 5 mm−1, the SLS with m = 2 and L = 5 mm−1 yields the largest total rotation-approximately 18, 110° over a propagation distance of 15m. As further clarified in the Discussion section, this rotation can be increased by using larger values of L. To further illustrate these trends, a–c of Fig. S6 shows the evolution of the angular rotation as a function of propagation distance for the cases listed in Table S1. The results clearly indicate that, increasing L enhances the rotation rate, producing faster angular evolution over the same distance. The corresponding mean angular rotation values, plotted in Fig. S6d, confirm a monotonic increase with L and an inverse dependence on m. Together, these findings demonstrate that both the rotation and the number of MISs can be effectively tuned by adjusting the structural parameters m and L. For further details on the rotational dynamics and minimal divergence of the generated beams, see Supplementary Note 3 (Rotational Dynamics and Minimal Divergence of the Generated Beams).

Discussion

The results demonstrate that the rotating BLPs generated by SLSs exhibit distinctive propagation characteristics governed by the structural parameters m and L. Increasing the curvature of the SLS lines enhances the rotation of the BLPs while reducing their divergence, leading to a quasi-non-diffractive propagation regime.

Further investigations in Supplementary Note 3 provide detailed analyses of the wavelength-dependent behavior and the localized self-amplification phenomena observed in the patterned zones of the generated beams. The results show that the rotational dynamics of BLPs are strongly influenced by the incident wavelength-an increase from 400 to 800 nm enhances the angular rotation of the MISs over the same propagation distance, as illustrated in Fig. S7 and Supplementary Movie 13.

The spinning area-referred to as the galactic-form spinning beam-represents the extended rotating field surrounding the core and is highlighted by the green dot-dashed circles in panels (a–c) of Fig. S8, where the diffraction patterns of three different SLSs with m = 10 and L = 1, 3, and 5 mm−1 are shown at a propagation distance of 15 m. The corresponding rotational dynamics of these beams are presented in Supplementary Movie 14. The relative power contained within this galactic-form spinning area, as indicated by the green dot-dashed lines in panels (d–f) of Fig. S8, increases during propagation and reaches approximately 20, 15, and 10% of the total transmitted power at a distance of 25 m, in the same order. For further details and the power percentage of the MISs and the surrounding core area, which includes the MISs and the pattern-less region, the reader is referred to Supplementary Note 3 (See Self-Amplification in the Patterned Zones of the Generated Beams).

To enable rotational dynamics at smaller scales suitable for particle manipulation, the geometry of the SLS can be tailored by adjusting the spoke curvature (L) while keeping the number of spokes (m) constant. For example, as illustrated in panels (a–c) of Fig. S9 and Supplementary Movie 15, two SLSs with m = 10 and spoke curvatures of L = 5 mm−1 and L = 500 mm−1 produce beams with identical angular rotations. However, the beam generated by the SLS with L = 500 mm−1 completes the rotation over only 2.5 mm of propagation-10,000 times shorter than the propagation distance required for L = 5 mm−1. This demonstrates that, increasing L by roughly two orders of magnitude allows the same rotational effect to occur over only 0.0001 of the original propagation distance, making this structure particularly suitable for laboratory-scale particle manipulation. For further details and a comparison of the radial and azimuthal positions of an MIS resulting from diffraction through the different SLSs, the reader is referred to Supplementary Note 3 (See Self-Amplification in the Patterned Zones of the Generated Beams), and panels (d–g) of Fig. S9.

Conclusion

In this work, we introduced a class of structured beams-termed galactic-form intensity-twisted vortex beams-generated by diffracting plane waves through SLSs with dual radial-azimuthal periodicity. These beams exhibit rich rotational and propagation dynamics, with the entire intensity pattern rotating around the optical axis during free-space propagation. The angular velocity of this rotation scales with the curvature of the radial spokes, while the overall divergence remains significantly lower than that of conventional RCBs, indicating a quasi-diffraction-resistant behavior.

The central region of the beam becomes dark, while the first intensity ring features high-intensity spots tracing helical paths. Due to their drill-like spatial structure and dynamic rotation, we refer to this inner ring configuration as an optical drill. As the curvature parameter L increases, both the rotational speed and power modulation frequency of the MISs increase; for lower L, the modulation becomes less frequent and occurs over longer distances. This self-organizing behavior results in a gradual, quasi-periodic amplification of power along the propagation axis, with the transfer of power from the pattern-less central region to the surrounding MISs becoming increasingly uniform with distance. It is observed that, the rate of power gain saturates over long propagation ranges.

Our results also confirm that the beams exhibit localized self-amplifying power properties, akin to those seen in RCBs, yet with enhanced directional control and confinement. These features make them well-suited for applications requiring efficient and stable beam propagation.

Particles placed along the trajectories of the MISs could potentially experience both rotational and axial optical forces, leading to simultaneous spinning and forward translation. This combined motion presents exciting prospects for advanced optical manipulation techniques, such as non-contact microfluidic transport, optical trapping of asymmetric or anisotropic particles, and the actuation of optically driven microrotors. These theoretical capabilities may pave the way for future applications requiring precise light-matter interaction, including biological cell manipulation, targeted drug delivery, and high-resolution control in micro- and nano-scale systems.

Additionally, we assessed the robustness of these beams under alignment imperfections, including slight off-axis displacements and non-normal illumination. Our findings indicate that the generated beam structure remains stable under such minor perturbations. Preliminary simulations also suggest that even structural imperfections, such as the removal of a single spiral line-do not significantly affect the rotation dynamics, emphasizing the inherent resilience of the beam design. Ongoing investigations are exploring the self-healing capabilities of these beams under environmental disturbances, such as atmospheric turbulence, with results to be reported in a forthcoming publication. These particular characteristics also suggest potential applications beyond optical manipulation, including enhanced imaging and robust long-range free-space optical communication.

Overall, the distinct structural and dynamic properties of galactic-form twisted vortex beams provide opportunities in light-matter interaction and beam engineering, with strong potential across both fundamental and applied photonics.

Methods

Numerical Simulation Method

When a plane wave with a complex amplitude ψ0 illuminates a structure defined by the transmission function t(x, y), the resulting distribution of the complex amplitude immediately after the structure, at the z = 0 plane, can be expressed as follows:

where (x, y) represents the Cartesian coordinates and z = 0 indicates the plane immediately after the structure. The complex amplitude of the field at a propagation distance z from the structure can be determined using the angular spectrum technique as follows1:

where, FT and FT−1 represent the Fourier transform and inverse Fourier transform, respectively, while H(x, y, z) denotes the free space transfer function under the Fresnel approximation, expressed as1

where \({h}_{0}=\exp (ikz)\), λ is the wavelength of the light beam, fx and fy are angular frequencies in the x and y direction, respectively. Unless otherwise specified, all simulations and experiments throughout this work are performed using a wavelength of λ = 532 nm, consistent with the experimental laser source.

By applying Eq. (1) in Eq. (4) and using Eq. (5), the diffraction patterns of a plane wave passing through various SLSs were numerically simulated based on the angular spectrum propagation method.

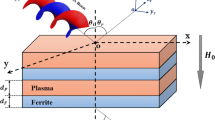

Experimental Setup

The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 10. A second-harmonic beam at 532 nm, generated by an Nd:YAG diode-pumped laser, was used. To achieve a uniform and expanded intensity profile, the beam first passed through a spatial filter. It was then collimated using a 4-inch diameter lens with a 65 cm focal length, ensuring that the SLSs were illuminated over a large area. Diffraction patterns were captured at various distances from the grating using a Nikon D100 camera; For this purpose, the camera’s built-in imaging lens was removed so that the diffraction patterns were recorded directly onto its sensor without any magnification. The SLSs were fabricated on transparent substrates using lithographic techniques with a spatial resolution of 600 dpi. Each SLS measures 3 × 3 cm2 and is fully illuminated by a uniform, expanded laser beam at the SLS plane. The beam size was adjusted to cover the entire SLS area, ensuring uniform illumination and maximizing diffraction efficiency.

A 532 nm second-harmonic beam from a diode-pumped Nd:YAG laser is first passed through a spatial filter to produce a clean, expanded profile, and then collimated by a 4 inch, 65 cm focal-length lens to uniformly illuminate the SLS. The diffraction patterns at different propagation distances are captured using a lensless Nikon D100 camera.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study comprise diffraction images recorded at 10 cm intervals along the propagation axis. Given the large number and substantial volume of these images, they are not publicly accessible. The complete dataset, including all recorded diffraction patterns, is available from the corresponding author for research purposes upon request.

Code availability

The MATLAB codes used to generate and analyze the data supporting the results of this study are publicly accessible in the online repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30208651.

References

Saleh, B. E. A. & Teich, M. C. Fundamentals of Photonics, Wiley, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471213748 (Wiley, 2019).

Nielsen, M. A. and Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976667 (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Kauranen, M. & Zayats, A. V. Nonlinear plasmonics. Nat. Photonics 6, 737–748 (2012).

Niemz, M. H. Laser-Tissue Interactions: Fundamentals and Applications, Springer Nature, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11917-1 (Springer, 2020).

Hecht, J. Optics: Light for a New Age, Jeff Hecht, (Scribner, 1987).

Rasouli, S., Khazaei, A. M. & Hebri, D. Radial carpet beams: a class of nondiffracting, accelerating, and self-healing beams. Phys. Rev. A 97, 033844 (2018).

Rasouli, S. & Fathollazade, S. Power amplification in the core area of radial carpet beams. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 41, 728–737 (2024).

Hell, S. & Stelzer, E. H. K. Properties of a 4Pi confocal fluorescence microscope. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 9, 2159–2166 (1992).

Corsetti, S., Gunn-Moore, F. & Dholakia, K. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy for neuroscience. J. Neurosci. Methods 319, 16–27 (2019).

Kafian, H. et al. Light-sheet fluorescence microscopy with scanning non-diffracting beams. Sci. Rep. 10, 8501 (2020).

Stelzer, E. H. K. et al. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 73 (2021).

Milanfar, P. Super-Resolution Imaging, (CRC Press, 2017).

Liu, M. et al. Super-resolution optical microscopy using cylindrical vector beams. Nanophotonics 11, 3395–3420 (2022).

Ashok, P. C. & Dholakia, K. Optical trapping for analytical biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 16–21 (2012).

Bayat, J. et al. Gear-like rotatable optical trapping with radial carpet beams. Sci. Rep. 10, 11721 (2020).

Verdeyen, J. T. Laser Electronics, (Prentice Hall, 1989).

Forbes, A. et al. Creation and detection of optical modes with spatial light modulators. Adv. Opt. Photonics 8, 200–227 (2016).

Forbes, A. et al. Structured light. Nat. Photonics 15, 253–262 (2021).

Amiri, P. et al. Talbot-effect-based multiplication of Laguerre-Gaussian beams with non-zero radial indices: from theory to experimental realization. Opt. Commun. 531, 131203 (2024).

Kowalczyk, J. et al. Generation of Bessel beams using a 4-f spatial filtering system. Am. J. Phys. 77, 229–236 (2009).

Arlt, J. & Dholakia, K. Generation of high-order Bessel beams by use of an axicon. Opt. Commun. 177, 297–301 (2000).

Rasouli, S. et al. Talbot carpet at the transverse plane produced in the diffraction of plane wave from amplitude radial gratings. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 35, 55–64 (2018).

Rasouli, S. et al. Colorful radial Talbot carpet at the transverse plane. Opt. Express 27, 17435–17448 (2019).

Hebri, D. & Rasouli, S. Combined half-integer Bessel-like beams: a set of solutions of the wave equation. Phys. Rev. A 98, 043826 (2018).

Kaushal, H., Jain, V. K. & Kar, S. Free-Space Optical Communication, Springer, Vol. 60, (Springer, 2017).

Bekshaev, A. Y. et al. Angular momentum of a rotating light beam. Opt. Commun. 249, 367–378 (2005).

Yu, H. & She, W. Rotation dynamics of particles trapped in a rotating beam. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 32, 90–100 (2015).

Khonina, S. N. et al. Generation of rotating Gauss–Laguerre modes with binary-phase diffractive optics. J. Mod. Opt. 46, 227–238 (1999).

Kotlyar, V. V., Khonina, S. N., Skidanov, R. V. & Soifer, V. A. Rotation of laser beams with zero of the orbital angular momentum. Opt. Commun. 274, 8–14 (2007).

Khonina, S. N. et al. Generating a couple of rotating nondiffracting beams using a binary-phase DOE. Optik 110, 137–144 (1999).

Pääkkönen, P. et al. Rotating optical fields: experimental demonstration with diffractive optics. J. Mod. Opt. 45, 2355–2369 (1998).

Chen, L. & Wang, L.-G. Experimental observation and manipulation of optical tornado waves. Opt. Lett. 47, 2109–2112 (2022).

Petrov, N. V., Pavlov, P. V. & Malov, A. N. Numerical simulation of optical vortex propagation and reflection by the methods of scalar diffraction theory. Quantum Electron. 43, 582 (2013).

Kotlyar, V. V., Soifer, V. A. & Khonina, S. N. Rotation of multimodal Gauss–Laguerre light beams in free space and in a fiber. Opt. Laser Eng. 29, 343–350 (1998).

Zhao, Z. et al. Dynamic spatiotemporal beams that combine two independent and controllable orbital-angular-momenta using multiple optical-frequency-comb lines. Nat. Commun. 11, 4099 (2020).

Niu, K., Zhao, S., Liu, Y., Tao, S. & Wang, F. Self-rotating beam in the free space propagation. Opt. Express 30, 5465–5472 (2022).

Sabatyan, A. & Behjat, Z. Radial phase modulated spiral zone plate for generation and manipulation of optical perfect vortex. Opt. Quantum Electron. 49, 1–10 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is based upon research funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF) under project No.4037534. The author Saifollah Rasouli would like to acknowledge the Abdus Salam International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), Trieste, Italy, for the Senior Associate Fellowship (No. 2018-2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R.: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Supplementary Movies, Software, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. H.M.: Supplementary Movies, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. L.-G.W.: Writing - review & editing, Validation, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Greg Gbur, Jing Du and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasouli, S., Mohammadi, H. & Wang, LG. Galactic-form spinning beams. Commun Phys 9, 20 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02450-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02450-1