Abstract

Precise control of phonon-polaritons (PhPs) in planar media is a central challenge for advancing mid-infrared nanophotonics. Here, we demonstrate cavity-driven excitation and shaping of in-plane PhPs in hBN using subwavelength resonators lithographically defined at the Au/SiO2 interface. These cavities efficiently couple far-field light into propagating PhPs and act as planar polaritonic lenses, with their shape governing the wavefront geometry and depth of field. We show that triangular and curved cavities generate “convex” and “concave” focusing behavior, enabling arbitrary spatial shaping of PhP fields. We achieve in-plane spatial confinement down to λ/70 and observe well-defined focal points. Our approach is fully compatible with standard fabrication techniques and decouples the light coupling and focusing functions-light couples at the cavity edge, while the cavity geometry governs the polariton wavefront. Unlike prior demonstrations in strongly in-plane-anisotropic media such as MoO3, our work establishes arbitrary focusing and deep-subwavelength confinement in hBN without relying on anisotropic substrates or exotic heterostructures. This cavity-driven scheme provides a distinct route for realizing polaritonic elements, including lenses, wavefront shapers, and metasurfaces operating in the mid-infrared.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strong light-matter interactions play a crucial role in well-established photonic devices, such as lasers, integrated photonic circuits, sensors, and hold promise for advancing future photonic quantum technologies, single-photon sources, entangled spin-photon interfaces, and quantum memories1. In particular, strong light-matter interactions can be achieved in propagating and localized phonon-polaritons (PhPs), which result from coupling between photons and phonons, quantized vibrations of a crystal lattice. PhP resonances occur in various polar crystals within the Reststrahlen band—the spectral region between the transverse (TO) and longitudinal (LO) optical phonons, where the real part of the dielectric function becomes negative. PhPs have garnered significant attention as they confine light substantially below the diffraction limit2,3,4. This enables PhP waveguides and cavities with exceptional electromagnetic confinement in the mid-infrared range (mid-IR) and with low propagation loss compared to plasmon-polaritons5. The mid-IR range of the spectrum is highly sought after due to its potential applications in medical diagnostics6,7, bio- and gas sensing8,9,10, LiDaRs for spacecraft11,12,13, optomechanics14, and optical trapping15. To achieve micrometer-scale integration of devices in the mid-IR range, the strong confinement provided by hyperbolic materials is likely the only viable solution.

Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) is one of the most promising and technologically accessible materials that provides a hyperbolic optical response in the mid-IR region of the spectrum. hBN is a uniaxial hyperbolic material that exhibits two types of hyperbolic optically active transitions – Type I - 760–820 cm−1 (εxx = εyy > 0; εzz < 0) and Type II - 1360–1600 cm−1 (εxx = εyy < 0; εzz > 0)3,16, where εij is the permittivity tensor components. Recent studies have reported on the reliable growth of large-scale high-quality crystals with the possibility to control their isotopic purity17,18,19. Currently, antennas are widely used to couple the far-field component of light with polaritonic systems, facilitating the selective launch of PhPs20,21,22,23. However, this approach suffers from two critical limitations: the lack of control over the wavefront and low in-plane spatial confinement of the launched PhPs. While hBN nanocavities exhibit strong mid-IR light confinement down to λ/500, where λ is the incident wavelength, an extraordinary Purcell factor (up to 1012), and a high quality factor (Q > 400), the resonant modes in these cavities remain trapped within the resonators24,25,26,27. Up to our best knowledge, there has been no demonstration of utilizing these localized modes to focus propagating PhPs. As for PhP focusing, impressive results with confinement up to λ/50 have been achieved in biaxial hyperbolic materials, such as MoO328,29,30, where the focusing occurs strictly along the optical axis. This fundamental constraint imposed by crystallographic directions makes such materials unsuitable for arbitrary-lens applications. This poses a significant limitation on the advancement of PhP-based technologies and leaves the effective control over spatially confined propagation and focusing in uniaxial hyperbolic materials unresolved. In contrast, hBN is in-plane isotropic and thus lacks crystallographic anisotropy as a natural focusing mechanism. In hBN, several demonstrations have been reported using exotic substrates possessing in-plane anisotropy, such as black phosphorus31 or tellurium32, or phase-change functionality, such as GST33, IST34, or VO235. While phase-change substrates are attractive for in-situ lens tuning, their influence remains inherently limited because PhP modes are strongly confined within the hBN layer itself. As a result, these substrate-assisted approaches fail to achieve high confinement factors of propagating polaritons, typically below λ/50.

Here, we demonstrate that cavity-driven excitation alone enables arbitrary wavefront shaping and deep focusing in hBN without resorting to anisotropic substrates or exotic heterostructures, thereby establishing a distinct and substrate-agnostic route to polaritonic optics. We obtain focused, spatially-confined, and long-lived PhPs that are launched by carefully engineered subwavelenght cavities. We fabricate sub-wavelength hBN cavities at the edges between Au and Si++/SiO2 (285 nm) substrates (see Fig. 1a). The Au edge acts as a scatterer, compensating for the momentum mismatch between incident light and PhPs. The Au/SiO2 interface enables the coupling of PhPs with the out-of-plane far-field component of the incident light and serves as an in-plane partially transparent mirror for PhPs. On the SiO2 side, it localizes a mode within the cavity, while on the Au side, it facilitates the launch of propagating and focused PhPs into the hBN bulk. Using scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy (s-SNOM), we visualize the real-space optical contrast and distinguish between cavity-launched (λp) and tip-launched (λp/2) modes. The cavity-launched PhPs result from coupling of the incident mid-IR light to the cavity modes and exhibit significant shape-dependent focusing. This approach for launching PhPs contrasts with s-SNOM tip-mediated excitation, which is employed in previous demonstrations of focused PhPs33. We propose a distinct method for launching and focusing spatially confined in-plane PhPs, fully compatible with standard lithographic procedures. By fabricating cavities with various shapes, that determine the focal points and wavefronts of the PhPs, we demonstrate “concave lens”-like and “convex lens”-like focusing. Concave lens”-like cavities achieve confinement down to λ/70 at the focal point, setting a record-high confinement compared to previous studies on in-plane-focused PhPs28,36,37,38.

a Schematics of the setup for the s-SNOM measurements of PhPs in hBN sub-wavelength resonators. A quantum cascade laser (QCL) emits a mid-IR beam toward a beam splitter, which divides it into a reference path and a sampling path. The reference path contains an interferometer with a mirror driven by a piezoelectric actuator at frequency M. The sampling path includes several mirrors and a parabolic mirror that focuses the beam onto the AFM tip. The light reflected from the sample is then combined with the reference beam and directed to a detector connected to a digital lock-in amplifier, enabling phase-amplitude separation and background-free detection. Note that the far-field light covers the majority of the sample’s area (spot radius ≥ 10 μm). b Optical amplitude (S4) image of the 42 nm-thick hBN flake placed on the pre-patterned Si/SiO2 substrate with Au stripes. Colored dotted lines indicate line-cuts of various propogating PhP waves. c S4 profiles taken across corresponding propagating PhP waves. d S-SNOM image of the cavity and propagating PhPs at various excitation wavelengths. e S4 profiles taken across the Au stripe and the cavity at ω = 1410 cm−1.

Results

In this work, we study two types of samples: (i) mechanically cleaved hBN crystals (of 30–45 nm thickness) transferred on the pre-patterned Au on Si++/SiO2 (285 nm) substrates as is (see Methods) and (ii) cavities fabricated at the interfaces between SiO2 and Au using electron-beam lithography and plasma etching (see the schematics in Fig. 1). Figure 1a shows the measurement scheme for s-SNOM accompanied by the schematics of the fabricated sample. Here, we use a commercially available s-SNOM equipped with PtIr-coated (23 nm thick) AFM tips with the curvature radii less than 25 nm. A tunable (λ = 5.5–11.5 μm) mid-infrared QCL allows us to cover Type II hyperbolic transition - 1360–1600 cm−1 (ϵxx = ϵyy < 0; ϵzz > 0) (see Methods section for details).

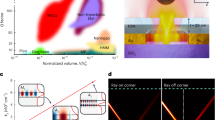

Figure 1 b shows optical amplitude (S4) versus tip position on a 42 nm-thick hBN flake placed on top of a 50 nm-thick Au stripe at ω = 1452 cm−1 (see topography and optical phase data in Supplementary Information Fig. S1). We focus on three specific regions: i) to the left of the Au stripe, ii) on top of the Au stripe, and iii) to the right of the Au stripe. The first region comprises a triangular hBN piece, where we observe distinct maxima and minima of the optical amplitude (related to the electric field amplitude \({({{{{{\rm{Re \space E}}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{z}}}}}})}^{2}\)), characteristic of localized resonant PhP modes27. In the second region, we identify two types of the PhP waves. The first type appears near the edges of the hBN flake (highlighted by the orange dotted line). The second wave emanates from the cavity (magenta dotted line). In the third region, additional two PhP waves are visible. The first wave is positioned near the edges of the hBN flake (blue dotted line). The second wave extends from the edge of the Au stripe to the right across the entire hBN bulk (purple dotted line).

The waves, which are localized close to the edge and propagate perpendicularly to it, are the tip-launched PhPs (we do not observe hBN edge-launched fringes in our geometry)39. These waves originate from the mid-IR light scattered on the AFM tip. The observed fringes represent only a half-wavelength of the corresponding PhP (λPhP/2) since the detection moves along with the excitation40,41. Based on this, we attribute the orange and the blue PhP waves to the tip-launched modes on Au and SiO2, respectively. Figure 1c shows linecuts taken along the dotted lines in the Fig. 1b. As expected, the magenta and the purple curves exhibit doubled wavelengths λPhP (compared to the tip-launched waves on Au and SiO2, respectively). They also demonstrate longer propagation lengths. We attribute these PhPs to the cavity-launched waves41. In the case of the purple curves, the right edge of the Au stripe launches the corresponding PhP in the hBN on SiO2. For the magenta curves, we assume that the left Au edge launches the PhPs inside the cavity where they localize and enhance, and then it leaks back through the semi-transparent interface into the hBN bulk on Au. We emphasize that the tip-launched PhPs (orange and blue curves) only exist when the AFM tip is present in the measurement setup, while the PhPs, indicated by the magenta and purple lines, couple to the far-field light and exist as long as there is far-field light excitation. Figure 1d shows a set of zoomed-in maps of the cavity-launched wave at various excitation wavelengths. The launched PhP (white arrow) moves and shrinks along with the resonant maximum position inside the cavity (see the detailed investigation of the dispersion in Supplementary Information Fig. S2). Figure 1e shows optical amplitude profiles taken along the magenta and the orange lines in Fig. 1d at ω = 1410 cm−1. We find that the electric field is significantly enhanced inside the cavity exhibiting a two-fold larger reflectivity compared to the bare gold signal (and seven-fold larger compared to hBN/SiO2 signal). This observation establishes our subwavelength cavities as effective PhP resonators.

To investigate PhP waves’ dependence on their shapes and sizes, we utilize a standard electron beam lithography and plasma etching (see Methods). We fabricate cavities of the desired shapes at the edges of gold patterns. Fig. 2a shows a topography of one of our samples. Attributed to an exceptional alignment (within ~10 nm) between the e-beam lithography steps, we create the matching edges between the patterned hBN and the Au substrates. This allows us to avoid unwanted leakages of the PhP modes away from our cavities. On the left hand side of the magenta dashed line, a 45 nm thick hBN flake covers a 50 nm thick Au stripe. On the right hand side, the patterned hBN triangles hang from the Au edge and lie down on the SiO2 substrate (note a smooth hBN topography height transition across the Au/SiO2 edge). Respectively, Fig. 2b shows an experimental s-SNOM amplitude (S3) taken at ω = 1450 cm−1 (see its dispersion and the analogous set of data for a 31 nm thick hBN in Supplementary Information Fig. S3 and S4, respectively). Inside the cavities, the scattered signal maxima confirm the field localization and enhancement.

a AFM topography of the Au edge with the resonators of triangular shapes. The hBN flake thickness is 45 nm. Magenta dashed line shows the edge between Au and SiO2. b Experimental s-SNOM amplitude (S3) map vs. the tip position recorded at ω = 1450 cm−1. Orange dashed lines indicate the edges of the cavity-launched resonator modes. c s-SNOM amplitude (S3) profiles taken across cavity-lanched waves (magenta, blue, and black lines) and the hBN flake edge on Au (purple line). Dashed lines show exponential decay fit for each curve.

Similar to the case in Fig. 1b, two different PhP types can be observed. The one that exhibits a λPhP/2 distance between intensity maxima is a tip-launched PhP (indicated by a purple arrow). This wave results from mid-IR light scattered by the s-SNOM tip, which excites PhPs propagating toward the edge of the sample, reflecting back, and interfering with themselves40,42,43,44,45. The cavity-launched PhPs show the distance between the intensity maxima of λPhP, which contrasts them with the tip-launched PhPs. λPhP/2 fringes are completely suppressed in front of the cavities, and only λPhP fringes are observed, which implies a suppressed back-reflection of the tip-launched PhPs at the cavity interface.

We find that the cavity-launched PhPs acquire well-defined focal points. For cavity 1 (see Fig. 2a, b), the PhP shrinks before and expands after the focal point (marked by the magenta arrow). The lateral size of the focal point corresponds to a confinement of λ/25. For cavity 2 and cavity 3, PhPs a focused at focal points outside of the detectable regions. The orange dashed lines serve as guides to the eye, indicating the boundaries of the cavity-launched PhPs. At the focal point, we identify a “hot spot” that corresponds to the electric field node. This shows that the PhP’s width and the focal point location can be effectively tuned by changing the size of a cavity. Figure 2c shows linecuts taken across the dashed lines in Fig. 2b (solid lines) and their exponential decay fits (dashed lines). Tip-launched PhPs exhibit rapid amplitude decay because they originate from the interference between tip-launched waves and those reflected from the edge, meaning they must complete a round-trip distance before detection. In contrast, cavity-launched PhPs exhibit oscillations with considerably slower amplitude decay. As a result, the cavity-launched PhPs propagate more than three times farther than those of tip-launched PhPs.

To characterize the decay rate quantitatively, we fit the amplitude of oscillations using an exponentially decaying function A = A0e−κx + Af, where A0 and Af are the fitting parameters related to the initial and the final amplitude values, x is the coordinate of the tip position, and κ is the attenuation constant. The larger the value of κ, the faster the damping. For the tip-launched PhPs in hBN/Au, we obtain Im k ~3.1 × 103 cm−1. For the all cavity-launched PhPs, Im k acquires several times smaller values Im k ~1.0 × 103 cm−1. Thus, the fitting demonstrates that the cavity-launched PhP quenches considerably slower than the ordinary tip-launched PhP.

Numerical model

We build a theoretical model that predicts optical properties of PhPs and effectively describes the PhP dynamics in the triangular cavities observed in the experiment. Figure 3a shows the dispersion of the propagation constant (Re k) of the PhP guided modes at the hBN/SiO2 and hBN/Au interfaces. The thickness of the hBN flake is 45 nm. The numerically calculated dispersions appear to be in good agreement with the data extracted from the experiment. The dispersions take into account the waviness of the hBN flake as a 5 nm gap formed due to the hBN transfer technique. Figure 3b shows the dispersion of the attenuation constant Im k and compares it with the decay rate κ = 2 × Im k obtained from the experiment. The numerical and experimental attenuation constants well-agree with each other between 1400 cm−1 and 1460 cm−1 but diverge at the frequencies above 1460 cm−1. We attribute this divergence to the absorption of residual polymers, specifically PMMA 950 A4 (polymethyl methacrylate, an e-beam lithography resist) and PC (polycarbonate, the top surface of a dry-transfer stamp), remaining on the sample surface after the fabrication process. These materials exhibit high absorption in this spectral range due to the presence of various carbon bonds46,47,48,49. The dispersion, refractive index and the attenuation constant for the 31- and 42-nm thick hBN can be found in Supplementary Information Fig. S5 and S6. We use the complex effective refractive index of PhPs extracted from the dispersions in Fig. 3a,b to construct a 2D model that captures the PhP wave dynamics in the cavities and waveguides formed at the hBN/SiO2 and hBN/Au interfaces, correspondingly. As can be seen from the insets in Fig. 3a, the simulated field distributions showcase a reasonable agreement with the experimental optical amplitude maps. The discrepancies between the simulated and experimental distributions, that are observed at the edges of the cavities, are due to the interactions of the s-SNOM probe and edges, while the probe is next to the edge of the cavity50. This interaction is wavelength dependent. However, in the experiment, the optical amplitude along the Au and hBN edges is noticeably higher, which is attributed to 3D effects at the edges of the heterostructure and buckling of the hBN at the Au edge which cannot be described within our 2D model. Figure 3c demonstrates the spatial distributions of the PhPs localized in the triangular hBN/SiO2 cavities and propagating in the hBN/Au waveguide. The distributions show that the triangular cavities can support localized PhP modes that leak into the hBN/Au environment and that the PhP waves are focused at a distance from the triangle base depending on the triangle size, which is also observed in the experiment (see Fig. 2b).

a Numerically calculated dispersion of propagating PhP modes generated at the hBN/SiO2 and hBN/Au interfaces (solid lines) compared to the experiment (symbols). Insets show the experimental s-SNOM optical amplitude (S4) maps and the theoretical spatial distributions of \({({{{{{\rm{Re\space E}}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{z}}}}}})}^{2}\) in triangular cavities, for the wavelength indicated by the gray dashed lines. b Numerically and experimentally obtained dispersion of the attenuation constant (Im k) for hBN/SiO2 and hBN/Au interfaces. The error bars indicate the spread of Im k in the experimental data. c \({({{{{{\rm{Re \space E}}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{z}}}}}})}^{2}\) in triangular cavities which we experimentally probe in Fig. 2. The distributions are taken at the cavity’s resonant frequencies. All calculations are done for hBN thickness of 45 nm.

The schematic analysis of the triangular and rectangular cavities (see Supplementary Information Fig. S7) shows that the shape of the PhP’s wavefront is closely related to the geometry of the cavity. For example, the size of the triangular cavity determines the focal point, while cavity-launched PhPs of rectangular cavities do not shrink and, as a result, do not obtain a focal point. Conclusively, due to a strong confinement, polaritons obey the laws of the wave optics, which brings up and opportunity to realize “concave lens”-like and “convex lens”-like focusing.

PhP lensing

Figure 4a–c show the AFM topography, the numerically calculated electric field \({({{{{{\rm{Re\space E}}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{z}}}}}})}^{2}\), and the experimental near-field optical amplitude (S3) of a 2.35-μm “convex lens”-like cavity, respectively. This patterned shape exhibits focused PhPs at a point beyond the cavity, similar to triangular cavities. A focal point can be observed where the curvature of the wavefront changes from positive to negative. Figure 4d illustrates a schematic of the “convex lens”-like focusing. The PhP waves launched by the Au edge propagate perpendicular to the Au edge inside the cavity and reflect back from the convex cavity edge. Upon reaching the cavity’s edge, they reflect normally to the curvature of the reflecting plane. The positive curvature of the reflecting plane results in a positive curvature of the PhP wavefront.

a AFM topography of a 2.35 μm cavity. The light yellow dashed line shows the edge between Au and SiO2. The thickness of hBN is 55 nm. b Numerical modeling of the cavity. \({({{{{{\rm{Re \space E}}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{z}}}}}})}^{2}\) in the 55 nm-thick convex-type cavity presented in (Fig. 4a). The distribution is taken at ω = 1410 cm−1. Magenta dashed lines are a guide for eyes indicating boundaries of cavity-launched polaritons. c Experimental s-SNOM optical amplitude (S3) map recorded at ω = 1410 cm−1. Magenta dashed lines are a guide for eyes indicating boundaries of cavity-launched polaritons. Dotted lines highlight maxima of optical amplitude for cavity-launched and tip-launched PhPs. Purple lines demonstrate tip-launched PhP waves. d Schematic of the “convex lens''-like cavity operation. e Experimental s-SNOM optical amplitude (S4) map of three small-diameter cavities (0.55 μm, 0.9 μm, and 1.1 μm, respectively) recorded at ω = 1405 cm−1. f Dependence of the focal point distance on cavity size at ω = 1410 cm−1, as well as the confinement factor for each point. g Dependence of the distance to the focal point on the excitation wavelength for small-diameter cavities (Fig. 4e). The depth of field (DoF) was determined for each cavity based on the distance oscillations. h Dependence of a full width at half maximum (FWHM) (purple lines) and confinement factor (magenta lines) on the excitation wavelength for small-diameter cavities.

Figure 4e shows the s-SNOM optical amplitude (S4) map of three cavities with different diameters: 0.55 μm, 0.9 μm, and 1.1 μm. The focal points are located at varying distances from the cavity/Au interfaces which is determined by its diameter. The focal distance as a function of the cavity diameter for ω = 1410 cm−1 is shown in Fig. 4f. As can be seen, the focal distance linearly depends on the cavity diameter (i.e., on the curvature of the reflective plane). Figure 4g demonstrates the distance to the focal point as a function of the frequency of the incident light for three cavities illustrated in Fig. 4e. The focal distance oscillates with a period specific to each cavity. Based on this, we determine the depth of field (DoF) for these cavities. DoF for classical lenses is the range of distances over which an object remains in focus, given by DoF = nλ/(NA)2, where n is the refractive index, λ is the wavelength, and NA is the numerical aperture. Each PhP lens has a specific focal length that depends on the geometry of the cavities, but at the same time, DoF for these lenses is finite and depends on the geometry of the cavities as well. By changing the excitation wavelength, we change the real-space PhP field distribution. Therefore, for some wavelengths, the maximum of the PhP field is located exactly in the middle of the focal point, while for other wavelengths, it is shifted to the edge of field (see the detailed investigation in Supplementary Information Fig. S8). Figure 4h demonstrates the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the focal point as well as the confinement factor calculated as λ/FWHM for cavities 1, 2, and 3 at different wavelengths. The FWHM decreases and the confinement increases with the increasing frequency, which is in agreement with the effective refractive index of hBN that grows with frequency (see Supplementary Information Fig. S6). A confinement factor as high as 70 can be achieved for the 0.9 μm cavity at ω = 1420 cm−1, placing it among the highest reported values.

Using the same approach, we developed a “concave lens”-like cavity (see Supplementary Information Fig. S9). The negative curvature of the reflecting plane produces a divergent PhP wavefront and defocusing. Furthermore, multiple cavities launching crisscrossing PhPs can be used for the formation of interference patterns (see Supplementary Information Fig. S10), forming a lattice of \({({{{{{\rm{Re \space E}}}}}}_{{{{{\rm{z}}}}}})}^{2}\) minima and maxima with a period equal to the PhP wavelength at the intersection. Thus, using the interference of cavity-launched PhP with adjusted wavefronts, it is possible to engineer polaritonic lattices for structured light-matter interaction.

Discussion

To accelerate the technological application of spatially defined PhP modes, it is crucial to develop a method for precisely controlling their spatial distribution and focusing them at specific real-space locations. Significant progress has been made in tuning and focusing PhPs using in-plane-anisotropic hyperbolic materials, such as MoO336,51,52. In the case of uniaxial hyperbolic hBN crystals, most efforts have relied on substrates with in-plane anisotropy in the relevant spectral ranges31,32,53 or substrate engineering as demonstrated by an elegant solution in Chaudhary et al.33, employing a phase-change material (Ge3Sb2Te6 on a CaF2 substrate) to locally modify dielectric constants and focus tip-launched PhPs.

One of the most widely adopted methods for focusing PhPs and coupling them to the far-field component of light is the use of metallic scatterers, typically made of gold54. This approach is essential because the tip must not be present in operational devices. By employing scatterers with curved surfaces, PhPs can be focused via wave interference. However, this approach has a fundamental limitation: the strength of light coupling to PhP modes depends heavily on the angle between light polarization and the normal to the scatterer surface at the launch point (see Supplementary Information Fig. S11). Consequently, curved scatterers can only efficiently focus PhP modes within a narrow angular range54, making them unsuitable for achieving arbitrary PhP lensing in isotropic materials like hBN.

Our approach overcomes these limitations by utilizing standard, technologically accessible materials (Si/SiO2, Ti/Au) as a platform for PhP engineering. We introduce hBN subwavelength cavities at the Au/SiO2 interface, which enable the generation of strongly focused (down to λ/70) and spatially confined PhPs. Crucially, our approach resolves the “scatterer” issue mentioned earlier: the Au/SiO2 interface facilitates coupling to far-field light but does not actively participate in the focusing process itself. Instead, the focusing mechanism is governed by the selection of PhPs with specific k-vector distributions inside the cavity. As a result, for a fixed Au/SiO2 interface orientation, cavities of varying shapes and sizes can produce different focusing effects (e.g., convex, concave, or straight wavefronts) and different angular ranges of collection. Thus, we believe our approach addresses several persistent challenges in PhP photonics and paves the way for numerous future discoveries.

We emphasize that our demonstration of arbitrary focusing in hBN is fundamentally different from prior lensing approaches in anisotropic van der Waals crystals, such as MoO3 or in substrate-engineered heterostructures. In those cases, the in-plane anisotropy or substrate modification inherently dictates the available polariton trajectories, restricting the optical response to crystallographic axes or substrate-induced symmetry breaking. In contrast, hBN is in-plane isotropic, and thus does not permit such an isotropy-driven focusing. Our results show that cavity-driven excitation alone can generate and shape polariton wavefronts in isotropic hBN, enabling convex- and concave-type focusing with subwavelength resolution. A comprehensive theoretical framework linking cavity geometry to k-space distributions of launched polaritons would be valuable for systematic design of polaritonic optics. Developing such a model lies beyond the scope of this experimental study, but our results provide the experimental foundation and clear motivation for such theoretical advances.

In conclusion, we have developed hBN sub-wavelength cavities that are compatible with standard lithographic techniques, enabling the launch of focused, long-lived PhPs. We have fabricated the subwavelength hBN cavities at the interfaces between Au and SiO2 partially transparent for PhPs. The localized modes exhibit a significant enhancement of the electric field inside the cavities, launching PhPs that remain spatially confined, with their confinement determined by the shape and size of the cavities. Using s-SNOM, we have studied the real-space optical contrast of the cavity-launched PhPs. Based on the PhP’s wavelength, we demonstrate coupling to the far-field component of the mid-IR light. The far-field component, which is resonantly enhanced in the cavities, acquires sufficient momentum to launch polaritons into the bulk of the hBN/Au heterostructures through the scattering process at the SiO2/Au interfaces. The shape of our resonators determines both the focal point location and the wavefront geometry. By creating different forms of cavities, we showe a focusing effect similar to a “concave lens” and a “convex lens.” In particular, the “convex lens”-like cavities enable field confinement down to λ/70 at the focal point. By this, we realize a promising technique for generating and focusing spatially confined in-plane PhPs compatible with the standard fabrication approaches.

Methods

Device fabrication

Si++/SiO2 substrates were pre-patterned using standard photolithography and metal deposition procedures. For photolithography, SUSS MicroTec MJB4 mask aligner and SPR-700 photoresist were used. After the photoresist development, we deposited metal (Ti/Au, 10/50 nm) using the Oerlikon 450B electron beam vacuum deposition system.

hBN flakes were prepared via mechanical exfoliation using PDMS adhesive tapes and were transferred on Si/SiO2 substrates for selection. Relying on optical contrast, we selected flakes of suitable thicknesses and transferred them on the pre-patterned Si++/SiO2 substrates using the PMDS/PC dry transfer method55,56.

For the cavity fabrication, we used the Raith EBPG5200 electron beam lithographer and PMMA 950 A4 e-beam resist. After the resist development, exposed hBN was etched out using Oxford ICP-RIE plasma etcher with CHF3 plasma source (40 sscm, 90 mTorr, 60 W).

Near-field optical measurements

We used a commercially available scattering-type scanning near-field microscope (s-SNOM) developed by Neaspec/Attocube (cryo-neaSCOPE) with a pseudo-heterodyne mode to a detect a background-free optical response (Ω ± NM) using the decoupled optical amplitude and phase57,58,59. PtIr-coated AFM tips (Nanoworld, 23 nm coating) with a resonant frequency ≈250 kHz were used to obtain the topography and the optical maps. AFM tips were illuminated by a tunable commercially available mid-infrared quantum cascade laser (QCL) using 1–2 mW of power (MIRcat, λ = 5.5–11.5 μm from the DRS Daylight Solutions Inc.) All optical measurements presented in the manuscript were obtained on the 3rd or the 4th harmonics (i.e., S3 and S4, respectively) to ensure the background-free detection.

Numerical model

To describe the optical phenomena in PhPs at the hBN/SiO2 and hBN/Au interfaces, we employ numerical calculations in COMSOL Multiphysics, Wave Optics module. The dispersions of the propagation and attenuation constants of the PhP modes alongside the complex effective refractive indices of these modes are calculated in a 4-layer structure, where the top layer is presented by air, the second layer is presented by hBN which is an anisotropic (along the hard axis) material with permittivity tensor taken from60 and optical axis directed perpendicular to the layers, the third layer is a narrow air gap, and the fourth layer is either SiO2 or Au with refractive indices taken from61,62. The obtained effective refractive indices are used as refractive indices for hBN/SiO2 and hBN/Au domains in the 2D model, and the surrounding space is treated as a dielectric with a refractive index of 1. As a source for the 2D model, we specify the surface current density at the edges of the hBN/SiO2, hBN/Au domains, and the surrounding space.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Rivera, N. & Kaminer, I. Light–matter interactions with photonic quasiparticles. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 538–561 (2020).

Henry, C. & Hopfield, J. Raman scattering by polaritons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 964 (1965).

Caldwell, J. D. et al. Sub-diffractional volume-confined polaritons in the natural hyperbolic material hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 5, 5221 (2014).

Li, N. et al. Direct observation of highly confined phonon polaritons in suspended monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 20, 43–48 (2021).

Giles, A. J. et al. Ultralow-loss polaritons in isotopically pure boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 17, 134–139 (2018).

Waynant, R. W., Ilev, I. K. & Gannot, I. Mid–infrared laser applications in medicine and biology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 359, 635–644 (2001).

Petrich, W. Mid-infrared and raman spectroscopy for medical diagnostics. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 36, 181–237 (2001).

De Bruyne, S., Speeckaert, M. M. & Delanghe, J. R. Applications of mid-infrared spectroscopy in the clinical laboratory setting. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 55, 1–20 (2018).

Popa, D. & Udrea, F. Towards integrated mid-infrared gas sensors. Sensors 19, 2076 (2019).

Lambert-Girard, S., Allard, M., Piché, M. & Babin, F. Differential optical absorption spectroscopy lidar for mid-infrared gaseous measurements. Appl. Opt. 54, 1647–1656 (2015).

Degtiarev, E. A compact frequency agile mid-infrared airborne lidar. (DTIC Document, 2006).

Groussin, O. et al. Thermap: a mid-infrared spectro-imager for space missions to small bodies in the inner solar system. Exp. Astron. 41, 95–115 (2016).

Olsen, K. S. et al. First detection of ozone in the mid-infrared at mars: Implications for methane detection. Astron. Astrophys. 639, A141 (2020).

Chen, W. et al. Continuous-wave frequency upconversion with a molecular optomechanical nanocavity. Science 374, 1264–1267 (2021).

Zhang, J., Liu, W., Zhu, Z., Yuan, X. & Qin, S. Towards nano-optical tweezers with graphene plasmons: numerical investigation of trapping 10-nm particles with mid-infrared light. Sci. Rep. 6, 38086 (2016).

Duan, J. et al. Launching phonon polaritons by natural boron nitride wrinkles with modifiable dispersion by dielectric environments. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702494 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Epitaxial growth of a 100-square-centimetre single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayer on copper. Nature 570, 91–95 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Single crystal growth of millimeter-sized monoisotopic hexagonal boron nitride. Chem. Mater. 30, 6222–6225 (2018).

Kubota, Y., Watanabe, K., Tsuda, O. & Taniguchi, T. Deep ultraviolet light-emitting hexagonal boron nitride synthesized at atmospheric pressure. Science 317, 932–934 (2007).

Ni, G. et al. Long-lived phonon polaritons in hyperbolic materials. Nano Lett. 21, 5767–5773 (2021).

Pons-Valencia, P. et al. Launching of hyperbolic phonon-polaritons in h-bn slabs by resonant metal plasmonic antennas. Nat. Commun. 10, 3242 (2019).

Li, P. et al. Hyperbolic phonon-polaritons in boron nitride for near-field optical imaging and focusing. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–9 (2015).

Dai, S. et al. Subdiffractional focusing and guiding of polaritonic rays in a natural hyperbolic material. Nat. Commun. 6, 6963 (2015).

Guo, X. et al. Hyperbolic whispering-gallery phonon polaritons in boron nitride nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 529–534 (2023).

Tamagnone, M. et al. Ultra-confined mid-infrared resonant phonon polaritons in van der waals nanostructures. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat7189 (2018).

Alfaro-Mozaz, F. et al. Nanoimaging of resonating hyperbolic polaritons in linear boron nitride antennas. Nat. Commun. 8, 15624 (2017).

Herzig Sheinfux, H. et al. High-quality nanocavities through multimodal confinement of hyperbolic polaritons in hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 23, 499–505 (2024).

Zheng, Z. et al. Controlling and focusing in-plane hyperbolic phonon polaritons in α-moo3 with a curved plasmonic antenna. Adv. Mater. 34, 2104164 (2022).

Martín-Sánchez, J. et al. Focusing of in-plane hyperbolic polaritons in van der waals crystals with tailored infrared nanoantennas. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj0127 (2021).

Duan, J. et al. Planar refraction and lensing of highly confined polaritons in anisotropic media. Nat. Commun. 12, 4325 (2021).

Chaudhary, K. et al. Engineering phonon polaritons in van der waals heterostructures to enhance in-plane optical anisotropy. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau7171 (2019).

Gong, Y. et al. Dispersion engineering of in-plane anisotropic phonon polaritons in HBN/TE van der waals heterostructures. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2302804 (2024).

Chaudhary, K. et al. Polariton nanophotonics using phase-change materials. Nat. Commun. 10, 4487 (2019).

Jäckering, L. et al. Tailoring phonon polaritons in hBN with the plasmonic phase-change material In₃SbTe₂. Nano Lett. 25, 15809–15816 (2025).

Folland, T. G. et al. Reconfigurable infrared hyperbolic metasurfaces using phase change materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 4371 (2018).

Qu, Y. et al. Tunable planar focusing based on hyperbolic phonon polaritons in α-moo3. Adv. Mater. 34, 2105590 (2022).

Ma, Y., Zhong, G., Dai, Z. & Ou, Q. In-plane hyperbolic phonon polaritons: materials, properties, and nanophotonic devices. npj Nanophotonics 1, 25 (2024).

Liang, J. et al. Manipulation of in-plane hyperbolic phonon polaritons for configurable focusing. ACS Photonics 11, 5031–5038 (2024).

Hu, G., Shen, J., Qiu, C.-W., Alù, A. & Dai, S. Phonon polaritons and hyperbolic response in van der waals materials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1901393 (2020).

Dai, S. et al. Efficiency of launching highly confined polaritons by infrared light incident on a hyperbolic material. Nano Lett. 17, 5285–5290 (2017).

Menabde, S. G., Heiden, J. T., Cox, J. D., Mortensen, N. A. & Jang, M. S. Image polaritons in van der waals crystals. Nanophotonics 11, 2433–2452 (2022).

Dai, S. et al. Tunable phonon polaritons in atomically thin van der waals crystals of boron nitride. Science 343, 1125–1129 (2014).

Basov, D., Fogler, M. & García de Abajo, F. Polaritons in van der waals materials. Science 354, aag1992 (2016).

Yoxall, E. et al. Direct observation of ultraslow hyperbolic polariton propagation with negative phase velocity. Nat. Photonics 9, 674–678 (2015).

Woo, H. J. et al. Selective mapping of tip-launched near-field scattering of surface plasmon polaritons for retrieving dispersion relation in silver nanoflakes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 2560–2568 (2023).

Petibois, C., Piccinini, M., CestelliGuidi, M., Déléris, G. & Marcelli, A. Infrared synchrotron sources-a boon for biology. Nat. Photonics 3, 177 (2009).

Guo, Z. et al. Effects of dispersion techniques on the emulsion polymerization of methyl methacrylate. Colloid Polym. Sci. 299, 1147–1159 (2021).

Tsuda, S., Yamaguchi, S., Kanamori, Y. & Yugami, H. Spectral and angular shaping of infrared radiation in a polymer resonator with molecular vibrational modes. Opt. Express 26, 6899–6915 (2018).

Tanaka, Y. & Gale, L. Protection from near-infrared to prevent skin damage. Opt. Photonics J. 5, 113–118 (2015).

Babicheva, V. E., Gamage, S., Stockman, M. I. & Abate, Y. Near-field edge fringes at sharp material boundaries. Opt. Express 25, 23935–23944 (2017).

Ma, W. et al. Ghost hyperbolic surface polaritons in bulk anisotropic crystals. Nature 596, 362–366 (2021).

Chen, M. et al. Configurable phonon polaritons in twisted α-moo3. Nat. Mater. 19, 1307–1311 (2020).

Hajian, H. et al. Tunable plasmon-phonon polaritons in anisotropic 2D materials on hexagonal boron nitride. Nanophotonics 9, 3909–3920 (2020).

Huber, A., Deutsch, B., Novotny, L. & Hillenbrand, R. Focusing of surface phonon polaritons. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 203104 (2008).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Purdie, D. G. et al. Cleaning interfaces in layered materials heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 9, 5387 (2018).

Ocelic, N., Huber, A. & Hillenbrand, R. Pseudoheterodyne detection for background-free near-field spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 101124 (2006).

Moreno, C., Alda, J., Kinzel, E. & Boreman, G. Phase imaging and detection in pseudo-heterodyne scattering scanning near-field optical microscopy measurements. Appl. Opt. 56, 1037–1045 (2017).

Keilmann, F. & Hillenbrand, R. Near-field microscopy by elastic light scattering from a tip. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 362, 787–805 (2004).

Kumar, A., Low, T., Fung, K. H., Avouris, P. & Fang, N. X. Tunable light–matter interaction and the role of hyperbolicity in graphene–HBN system. Nano Lett. 15, 3172–3180 (2015).

Kischkat, J. et al. Mid-infrared optical properties of thin films of aluminum oxide, titanium dioxide, silicon dioxide, aluminum nitride, and silicon nitride. Appl. Opt. 51, 6789–6798 (2012).

Babar, S. & Weaver, J. Optical constants of CU, AG, and AU revisited. Appl. Opt. 54, 477–481 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrey Bogdanov, Lorenzo Orsini, Frank H. L. Koppens and Hanan Herzig Sheinfux for helpful discussions. The authors thank Morten R. Eskildsen for his assistance in setting up the experiment. P.S. acknowledges support from the start-up fund provided by the University of Notre Dame (#373837). S. L. acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council (Grant No. 101045396 - SPOTLIGHT) and Danish National Research Foundation (Grant No. DNRF147 NanoPhoton). K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 21H05233 and 23H02052) and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S. and B.B conceived and designed the experiment. B.B. fabricated samples and performed the measurements. The data were analyzed and interpreted by B.B., S.L., and P.S. The hBN crystals were provided by K.W. and T.T. S.L performed the numerical calculations. B.B, S.L., and P.S. wrote the manuscript. P.S. supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borodin, B., Lepeshov, S., Watanabe, K. et al. Cavity-driven arbitrary in-plane focusing of phonon polaritons in hBN with deep-subwavelength confinement. Commun Phys 9, 18 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02451-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02451-0