Abstract

Understanding entanglement percolation across quantum networks (QNs) has been a persistent challenge. Concurrence percolation theory (ConPT) provides a statistical-physics framework for this, drawing parallels between entanglement measure (concurrence) and classical percolation measure (probability). However, ConPT’s reach has been confined to idealized, pure-state entanglement resources, overlooking realistic mixed states “contaminated” by stochastic noise. This work extends into this realistic domain, introducing a mixed-state ConPT that reveals a percolation threshold lower than the pure-state counterpart. This paradoxical finding seemingly suggests that stochastic contamination is less detrimental than purity-preserving unitary noise, a notion that challenges conventional belief. We resolve this finding by highlighting an operational detail: implementing mixed-state ConPT effectively requires quantum memory to buffer the probabilistic nature of mixed-state protocols. We find evidence that without quantum memory, mixed-state ConPT consistently underperforms pure-state ConPT. This reinforces our understanding that stochastic noise poses a more significant impediment, a critical consideration for QN design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum networks (QNs) hold the promise of connecting remote nodes using quantum resources1,2, enabling revolutionary applications such as secure communication3, distributed quantum computing4, and enhanced sensing5, which are beyond the capabilities of classical systems. Central to realizing large-scale QNs is the generation and sustained distribution of quantum correlations—particularly entanglement—across distant nodes6,7. The ability to “weave” entanglement throughout a QN is based on local operations and classical communication (LOCC)8, as specified by quantum resource theory9. Yet, realistic LOCC between distant nodes is severely hampered by photon loss and decoherence. To model these limitations and understand the connectivity of QNs, researchers have successfully adapted concepts from statistical physics, specifically the theory of bond percolation10. A seminal approach in this area is classical entanglement percolation (CEP)11. The CEP framework predicts the existence of a critical entanglement threshold, above which the QN can form long-distance entanglement through quantum protocols. More recently, concurrence percolation theory (ConPT) was introduced as an alternative to CEP12. While CEP employs probability as the key measure13, in ConPT the key measure becomes concurrence—an entanglement monotone14, which has the nice property of remaining scalable under deterministic protocols15. This deterministic nature eventually shows higher efficiency for distributing entanglement than traditional probabilistic protocols as used in CEP, consequently leading to a lower, more favorable entanglement threshold than what CEP predicts.

While the superiority of ConPT over CEP seems promising, it relies on a critical assumption that the network’s resources are pure states. In practice, imperfections in quantum devices mean that mixed states are unavoidable resources16,17,18. Extending entanglement percolation to networks of mixed states thus emerges as a practical, if not more significant, challenge. To address this, an early attempt by Broadfoot et al. developed a CEP-based strategy for mixed states arising from amplitude damping noise17,18. Their method, however, imposes stringent conditions: it requires that any connected pair of nodes share in parallel at least two copies of a specially structured mixed state: \({\rho }_{s}=\lambda \left|\alpha ,\gamma \right\rangle \left\langle \alpha ,\gamma \right|+(1-\lambda )\left|01\right\rangle \left\langle 01\right|\), where \(\left|\alpha ,\gamma \right\rangle =\sqrt{\alpha }\left|00\right\rangle +\sqrt{1-\alpha -\gamma }\left|11\right\rangle +\sqrt{\gamma }\left|01\right\rangle\) and 0 < λ ≤1. This requirement restricts not only the type of noise but also the network’s topology, limiting its general applicability.

To address this gap, our work investigates entanglement percolation in the presence of another important type of noise: bit-flip errors, which commonly arise from imperfect gate operations and environmental disturbances19,20,21,22,23. We demonstrate that a ConPT framework can be generalized to these resulting mixed states. We find that concurrence remains scalable under our use of protocols, allowing us to construct a mixed-state concurrence percolation model at arbitrary scale.

This generalization leads to the following initial finding: the mixed-state ConPT appears to have a lower percolation threshold than its pure-state counterpart for the same initial link concurrence. This counter-intuitive result would imply that the stochastic (bit-flip) noise we investigate is somehow less disruptive than the unitary noise that merely reduces the entanglement (but not the purity) of states. This seems to contradict the general principle in quantum information that stochastic noise is typically more detrimental than unitary noise.

We resolve this paradoxical finding by identifying a conceptual gap in our generalization: the protocols used in the mixed-state ConPT are no longer deterministic but probabilistic. Practically, this necessitates some mechanism to ensure the success of the protocols (for example, through the use of quantum memories to buffer successful events24,25,26). Otherwise, our concurrence percolation framework would be incomplete, as it must also consider the failure of protocols fundamentally rooted in this probabilistic nature. Accounting for this subtlety, we successfully show that the mixed-state ConPT threshold is no longer lower than its pure-state counterpart. This finding reinforces the understanding of the detrimental impact of stochastic noise.

Further, from a statistical physics perspective, we notice that the phase transition undergoes a qualitative shift from continuous for pure states to discontinuous for mixed states. We propose this is a consequence of our self-averaging treatment of the probabilistic protocols. This finding could pave the way for uncovering novel critical characteristics in noisy QNs.

Methods

Quantum network under bit-flip error

We consider a QN model where each link (edge) represents a bipartite entangled state shared between adjacent nodes (vertices). This entangled state is subject to bit-flip error, resulting in a mixed state:

where 1/2 < F≤1 denotes the fidelity of the state, and \(\left|{\phi }^{+}\right\rangle =(\left|00\right\rangle +\left|11\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) and \(\left|{\psi }^{+}\right\rangle =(\left|01\right\rangle +\left|10\right\rangle )/\sqrt{2}\) represent the Bell states. It is straightforward to show that the mixed state ρ(F) forms a special class of the X states27,28. We denote a QN comprising n nodes by \({{\mathcal{G}}}(n)\); or by \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}_{F}(n)\) when all links in \({{\mathcal{G}}}(n)\) are characterized by an identical F.

Concurrence percolation theory

ConPT uses the entanglement measure concurrence, instead of probability, to construct a theory analogous to classical percolation theory for QNs. For pure bipartite states, the concurrence is defined as \(c=\sqrt{2(1-\,{{\rm{Tr}}}\,{\rho }_{r}^{2})}\), where ρr is the reduced density matrix of the bipartite state29. The concurrence of the mixed state in Eq. (1) is found to be27,28

ConPT employs sponge-crossing concurrence CSC as an order parameter to quantify the establishment of entanglement between boundaries of a QN12,15,30,31,32. The quantity CSC represents a weighted summation of all open paths that connect the distant boundaries, where each link’s contribution is weighted by its concurrence. In this framework, the boundaries are treated as two “mega nodes” (denoted S for source and T for target) that collectively represent all boundary nodes, and CSC measures the concurrence of the resulting entangled state established between S and T. When n → ∞, a threshold emerges:

such that cth is the minimum value of the weight c below which CSC becomes zero. Consequently, for any \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}_{F}(n)\) where the concurrence c exceeds the threshold value cth, long-distance entanglement transmission between the boundary nodes S and T can be achieved.

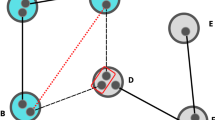

In a series-parallel network33 such as the Bethe lattice (Fig. 1a), CSC can be computed using only series and parallel rules. However, when the network includes non-series-parallel “loops”33—such as in the 2D square lattice and 2D honeycomb lattice (Fig. 1b, c), additional higher-order connectivity rules become necessary12 (Supplementary Note 3). It can be effectively approximated by employing only the series and parallel rules, similar to a local renormalization group process34.

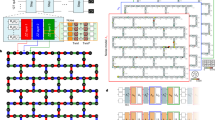

We define and apply mixed-state concurrence percolation to three network topologies, treating the boundaries as two “mega nodes"-the source (S) and target (T): (a) the Bethe lattice (S: the root; T: the outermost layer nodes); (b) the 2D square lattice (S: left boundary; T: right boundary); and (c) the 2D honeycomb lattice (S: left boundary; T: right boundary). In the framework of concurrence percolation, the distribution of entangled mixed states ρ(F) employs a combination of (d) series, (e) parallel, and (f) higher-order connectivity rules to systematically compute the distributable entanglement (concurrence) “sponge-crossing” between S and T. The series and parallel rules can be achieved by quantum operations, specifically (d) entanglement swapping and (e) purification protocols. The two rules can also be used to (f) effectively approximate higher-order connectivity rules which represent unknown quantum operations12.

Series and parallel rules

The series rule is implemented by entanglement swapping. We first consider the scenario in which two links ρAR, ρRB are connected in series between three nodes (S–R–T), as shown in Fig. 1d, where S and R share a mixed state ρ(F1), and R and T share another mixed state ρ(F2). Performing a swapping operation on R, four probabilistic outcomes between S and T are realized via projection35,36. When a particular measurement basis is chosen for projection6,37, the link between S and T is projected onto one of the four outcome states \({\rho }_{{{\rm{ST}}}}^{{\phi }^{\pm }}\) and \({\rho }_{{{\rm{ST}}}}^{{\psi }^{\pm }}\) with the probabilities of \({p}_{{\phi }^{\pm }}=1/4\) and \({p}_{{\psi }^{\pm }}=1/4\), respectively. The final concurrences of each outcome are identical, equal to cSRcRT. Hence, the final average concurrence is \(c={\sum }_{i=1}^{4}{p}_{i}{c}_{i}={c}_{{{\rm{SR}}}}{c}_{{{\rm{RT}}}}\). Moreover, the four outcomes are locally unitary-equivalent. Hence, the swapping operation is an example of deterministic LOCC because it only yields one possible outcome, up to local unitary transform12. If the concurrence of each link is cj for j = 1, 2, …, n, and these links are connected in series by a chain, then after performing swapping at the n − 1 intermediate nodes in succession, the final concurrence is given by the formula (Supplementary Note 1):

The parallel rule is implemented by entanglement purification. For two parallel links between S and T (Fig. 1e), the two links ρST(F1) and ρST(F2) form a tensor-product state, ρST = ρST(F1) ⊗ ρST(F2). Utilizing the purification protocol38, we can obtain a new mixed state \({\rho }_{{{\rm{AB}}}}({F}^{{\prime} })\) with \({F}^{{\prime} }=\frac{{F}_{1}{F}_{2}}{{F}_{1}{F}_{2}+(1-{F}_{1})(1-{F}_{2})}\). Since F1 > 1/2 and F2 > 1/2, we see that \({F}^{{\prime} } > {F}_{1}\) and \({F}^{{\prime} } > {F}_{2}\). If the concurrences of ρST(F1) and ρST(F2) are c1 and c2, respectively, the concurrence of the successfully purified state \({\rho }_{{{\rm{ST}}}}({F}^{{\prime} })\) is \({{\rm{Para}}}({c}_{1},{c}_{2})=\frac{{c}_{1}+{c}_{2}}{1+{c}_{1}{c}_{2}}\). One approach to implement this purification protocol is to encode the two entangled states ρST(F1), ρST(F2) into distinct modes (e.g., polarization and spatial) of one photon pair—known as the hyperentanglement mechanism—which can achieve higher efficiency than the usual two-copy entanglement purification protocols39,40,41. This hyperentanglement mechanism may also be effectively extended to other degrees of freedom in terms of photon modes, such as time bin42, frequency43, and orbital angular momentum44, which enables multi-step purification that further enhances the fidelity of entanglement. Given n links between node S and node T with concurrences c1, c2, …, cn, the parallel sum, assuming every purification operation succeeds, is given by (Supplementary Note 2):

Table 1 summarizes the series and parallel rules for the pure-state ConPT12 and our mixed-state ConPT. Both sets of the rules are inherently scalable, as the series rule satisfies

and the parallel rule satisfies

This scalability is critical for large-scale, versatile QN design, making QNs potentially more adaptable to experimental and technological constraints.

Results

A counter-intuitive low threshold

We investigate the sponge-crossing concurrence CSC and percolation threshold cth for three network topologies, including the Bethe lattice, the square lattice, and the honeycomb lattice:

Bethe lattice

The Bethe lattice represents a typical series-parallel network where each node has the same degree k. Further, it serves as an approximation for many real-world networks, as long as loops in such networks may be effectively ignored. When the number of nodes n → ∞, we can select any node as the root and subsequently establish an exact recurrence relation between the root and the subroots12,45. The behavior of CSC in Bethe lattices with k = 3 is shown in Fig. 2a. We find that the percolation threshold for mixed-state ConPT, \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}=1/2\), is lower than that for pure-state ConPT, given by \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}=1/\sqrt{2}\). For a general degree k, we derive the threshold \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}=1/\left(k-1\right)\) (Supplementary Note 4), which also yields \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}} < {c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\) where \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}=1/\sqrt{k-1}\)12.

The concurrence of each link, c, and the sponge-crossing concurrence, CSC, are plotted on the x-axis and y-axis, respectively. The gray solid and dashed vertical lines mark the thresholds for mixed-state and pure-state concurrence percolation, respectively. a Bethe lattice with degree k = 3. The blue and orange curves represent the mixed-state and pure-state sponge-crossing concurrences CSC. The dashed orange line is unphysical. b, c 2D square and honeycomb lattices. The solid line connecting the circles represents the mixed-state CSC, while the dashed line connecting the triangles represents the pure-state CSC. Here L denotes the side length of the 2D lattices.

Finite-size scaling analysis further shows that CSC exhibits an exponential cutoff: \({C}_{{{\rm{SC}}}} \sim {e}^{-l/{l}^{* }}\) with respect to the shortest path length l between S and T when the Bethe lattice (k = 3) has finite l layers. The characteristic length l* quantifying the cutoff diverges as a power law upon approaching the percolation threshold cth12. For both pure- and mixed-state ConPT, we identify the same critical behavior l* ~ ∣c − cth∣−1 in the Bethe lattice (Supplementary Note 5).

2D lattices

In 2D square and honeycomb lattices, all nodes on the left boundary are connected to a common “mega node” S, while all nodes on the right boundary are connected to a common “mega node” T, with these connecting links assigned a unit weight (c = 1). The value of CSC is determined not only through series and parallel rules but also by employing the SM transform. In 2D square and honeycomb lattices, where an analytical threshold cannot be derived as in the Bethe lattice case, we predict the percolation threshold in the thermodynamic limit (n → ∞) by employing finite-size scaling: the threshold is identified as the intersection point of the CSC curves across different lattice sizes. The behaviors of CSC for different lattice sizes L are presented in Fig. 2b, c. The vertical solid and dashed lines represent the thresholds predicted by mixed-state and pure-state ConPT, respectively. We again find \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}} < {c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\) for both 2D lattices.

General topologies

Our results show that all mixed-state thresholds for the three different network topologies are lower than those of their pure-state counterparts (Table 2). It is straightforward to see that this observation must be rooted in the difference between the pure-state and mixed-state parallel rules (Table 1). This prompts us to define \(\delta ({c}_{1},{c}_{2},\ldots ,{c}_{n})={{\rm{Para}}}{({c}_{1},{c}_{2},\ldots ,{c}_{n})}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}-{{\rm{Para}}}{({c}_{1},{c}_{2},\ldots ,{c}_{n})}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}.\) If δ(c1, c2, …, cn)≥0, we can demonstrate that \({C}_{{{\rm{SC}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}\ge {C}_{{{\rm{SC}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\) for any network topology \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}_{F}(n)\), which further leads to the conclusion that \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}\le {c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\) in the n → ∞ limit.

Given the scalability of the parallel rule [Eq. (7)], it is sufficient to show δ(c1, c2)≥0. We derive:

where \(g=\left({c}_{1}+{c}_{2}\right)/\left(1+{c}_{1}{c}_{2}\right)\) and \(f=\frac{1+\sqrt{1-{c}_{1}^{2}}}{2}\frac{1+\sqrt{1-{c}_{2}^{2}}}{2}.\) We find that the minimum value of δ(c1, c2) is equal to zero and the maximum value is close to 0.142. Thus, δ (c1, c2)≥0 holds.

Non-deterministic mixed-state concurrence percolation

The inequality \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}\le {c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\) yields the following result: it suggests that stochastic noise is less detrimental than unitary noise. The underlying reason for this is subtle: the parallel rule for our mixed-state ConPT is not deterministic LOCC. Therefore, it has a finite probability of failure—an additional complication for our mixed-state ConPT. This stands in contrast to pure-state ConPT, which implements the parallel rule via the entanglement concentration protocol46, a process that, according to Nielsen’s theorem, can be made deterministic8.

In principle, the parallel rule for mixed-state ConPT could still be rendered deterministic by using quantum memories to selectively store only successful purification outcomes. This approach would require k − 1 pairs of memories for each layer of the Bethe lattice to store the k − 1 successfully purified entangled states. However, the stringent memory capacity this demands makes the strategy experimentally challenging. In the following, we no longer assume that the purification protocol is always successful and explicitly account for the probabilistic nature of the parallel rule.

Bethe lattice

We reconsider the mixed-state ConPT for the Bethe lattice. The consideration of success probability could be effectively regarded as a “dilution” of the degree k (or more precisely, the excess degree k − 147,48) of the Bethe lattice. Specifically, we need to make the change

where

is the success probability of purifying all k − 1 links of concurrences c1, c2, …, ck−1 (Supplementary Note 2). We then calculate the sponge-crossing concurrence CSC on the diluted Bethe lattice. By exploiting the lattice’s self-similar structure, we obtain an exact solution for CSC as a function of c for various k (Fig. 3a). The physical branch of this solution reveals a discontinuous phase transition49 (Fig. 3b). This result contrasts with continuous transitions typically observed in pure-state ConPT or classical percolation. We hypothesize that the reason for this result lies in the nature of Eq. (9). This equation offers a self-averaged solution, which assumes every layer of the diluted Bethe lattice produces an identical (non-integer) number of branches. In reality, the probabilistic process of Eq. (10) implies a heterogeneous dilution, where some layers successfully generate many branches while others produce few or none. We speculate that properly accounting for this heterogeneity could restore the continuous nature of the phase transition, or even smear it out entirely50. A full analysis of such heterogeneous effects is nevertheless beyond the scope of the present work.

The concurrence of each link, c, and the sponge-crossing concurrence, CSC, are plotted on the x-axis and y-axis, respectively. The degree of the Bethe lattice is denoted by k. a The sponge-crossing concurrence CSC with respect to c in Bethe lattices for k = 3 to k = 11. The dashed lines represent solutions that are not physical. b The physical part of CSC. The thresholds are marked by vertical dotted lines. The inset displays a magnified view of the physical part of CSC for c values in the range of 0.719 to 0.745.

Accepting the self-averaging treatment [Eq. (9)], we can determine the percolation threshold cth precisely; the results are given in Table 3. While an exact analytical solution for the threshold as a function of k is unavailable, our numerical analysis yields an effective approximate solution (Supplementary Note 6):

where \(m=(k-1)\left({5}^{k-1}+1\right)/{6}^{k-1}\). This nontrivial threshold demonstrates that long-distance entanglement distribution remains achievable in QNs affected by bit-flip error, even when accounting for the probabilistic nature of the parallel rule. Interestingly, the threshold shows a nonmonotonic dependence on k, in stark contrast to the strictly decreasing behavior previously observed. We find that the threshold value decreases from k = 3 until k = 6, reaching a minimum of cth ≈ 0.72 at k = 6, and then increases from k = 6 to k = 11. Most importantly, the thresholds in the diluted Bethe lattice significantly exceed those of the pure-state case, particularly for large k. This key finding reverses the previously counterintuitive inequality, yielding \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}\ge {c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\), confirming the expectation that stochastic noise is indeed more detrimental than unitary noise.

2D square lattice

Unlike the Bethe lattice, the 2D square lattice contains loops that place it outside the category of series-parallel networks. Although they are self-similar, we cannot apply the same method of “diluting" node degrees. Instead, we incorporate probabilistic effects by calculating the expected value of the parallel rule, replacing the deterministic version with its probabilistic expectation:

The obtained threshold of 0.92(7) is higher than that of the pure-state scenario (Fig. 4). This again hints that stochastic noise is indeed more detrimental than unitary noise. Furthermore, we observe that the phase transition changes from continuous to seemingly discontinuous with increasing L, consistent with the observation for the Bethe lattices.

The concurrence of each link, c, and the sponge-crossing concurrence, CSC, are plotted on the x-axis and y-axis, respectively. L denotes the side length of the 2D square lattices. The vertical line represents the threshold predicted by probabilistic mixed-state ConPT when L → ∞. The new threshold cth = 0.92(7) is higher than the pure-state cth = 0.62(3) (Table 2).

Discussion

In this paper, we establish a mixed-state ConPT for QNs subject to bit-flip noise, providing a direct and efficient framework for analyzing realistic systems. Our approach simplifies practical implementation by using scalable operations on a wide class of mixed states. The analysis reveals complex physics centered on the system’s concurrence percolation threshold, informing the comparison between stochastic (bit-flip) noise versus unitary (purity-preserving) noise, which provides the first quantitative insight into the impact of different kinds of noise on entanglement percolation.

Two limitations in the current work warrant discussion. First, our final result relies on the self-averaging treatment of Eq. (9). A more complete treatment is necessary to determine if the relationship \({c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{mixed}}}}\ge {c}_{{{\rm{th}}}}^{{{\rm{pure}}}}\) is truly ubiquitous. We hypothesize that a more rigorous model must go beyond the ConPT framework to incorporate the success probability of the underlying protocols, exploring the interdependence between these two quantities—namely classical probability versus quantum entanglement. Furthermore, our analysis is specific to the class of mixed states generated by bit-flip noise. It remains an open question whether our conclusions generalize to QNs experiencing other forms of decoherence. Exploring QNs with alternative types of mixed states may present a significant challenge.

We hope that our work lays the groundwork for several critical future directions. For example, it is unknown whether scalable purification protocols that are more efficient could be found, leading to further lower thresholds. Also, we note that the probabilistic nature of purification induces a classical percolation process on the network through link removal. This insight is particularly promising because it opens the possibility of applying preprocessing strategies to the QN11. By optimizing the network’s topology before the main entanglement percolation process, such strategies could lead to different and potentially enhanced percolation thresholds.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the tables, figures, and Supplementary Information. Additional raw data used to generate the plots can be made available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The code is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Cirac, J. I., Zoller, P., Kimble, H. J. & Mabuchi, H. Quantum state transfer and entanglement distribution among distant nodes in a quantum network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3221–3224 (1997).

Boozer, A. D., Boca, A., Miller, R., Northup, T. E. & Kimble, H. J. Reversible state transfer between light and a single trapped atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 193601 (2007).

Simon, C. Towards a global quantum network. Nat. Photon. 11, 678–680 (2017).

Campbell, E. T., Terhal, B. M. & Vuillot, C. Roads towards fault-tolerant universal quantum computation. Nature 549, 172–179 (2017).

Zhang, Z. & Zhuang, Q. Distributed quantum sensing. Quant. Sci. Technol. 6, 043001 (2021).

Perseguers, S., Cirac, J. I., Acín, A., Lewenstein, M. & Wehr, J. Entanglement distribution in pure-state quantum networks. Phys. Rev. A 77, 022308 (2008).

Kimble, H. J. The quantum internet. Nature 453, 1023–1030 (2008).

Nielsen, M. A. Conditions for a class of entanglement transformations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 436–439 (1999).

Chitambar, E. & Gour, G. Quantum resource theories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 025001 (2019).

Grimmett, G. Percolation. (Springer, Berlin, 1999).

Acín, A., Cirac, J. I. & Lewenstein, M. Entanglement percolation in quantum networks. Nat. Phys. 3, 256 (2007).

Meng, X., Gao, J. & Havlin, S. Concurrence percolation in quantum networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 170501 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Hou, J., He, K., Lo Piparo, N. & Meng, X. Nonconvex entanglement monotone determining the characteristic length of entanglement distribution in continuous-variable quantum networks. Phys. Rev. A 111, 042429 (2025).

Hill, S. & Wootters, W. K. Entanglement of a pair of quantum bits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 5022–5025 (1997).

Meng, X., Cui, Y., Gao, J., Havlin, S. & Ruckenstein, A. E. Deterministic entanglement distribution on series-parallel quantum networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013225 (2023).

Yu, N. The Quantum Repeater Network saturates the Entanglement Distribution asymptotically. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theor. 71, 6155 (2025).

Broadfoot, S., Dorner, U. & Jaksch, D. Entanglement percolation with bipartite mixed states. Europhys. Lett. 88, 50002 (2009).

Broadfoot, S., Dorner, U. & Jaksch, D. Singlet generation in mixed-state quantum networks. Phys. Rev. A 81, 042316 (2010).

Perseguers, S. One-shot entanglement generation over long distances in noisy quantum networks. Phys. Rev. A 78, 062324 (2008).

Nielsen, M. A., Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010.

Chang, X. et al. Hybrid entanglement and bit-flip error correction in a scalable quantum network node. Nat. Phys. 22, 583–589 (2025).

Caleffi, M. & Cacciapuoti, A. S. Quantum switch for the quantum internet: Noiseless communications through noisy channels. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 38, 575–588 (2020).

Chen, L. & Jia, Z. On optimum entanglement purification scheduling in quantum networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 42, 1779–1792 (2024).

Yu, Y. et al. Entanglement of two quantum memories via fibres over dozens of kilometres. Nature 578, 240–245 (2020).

Wang, Y., Craddock, A. N., Sekelsky, R., Flament, M. & Namazi, M. Field-deployable quantum memory for quantum networking. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 044058 (2022).

Meng, X., Lo Piparo, N., Nemoto, K. & Kovács, I. A. Quantum communication networks enhanced by distributed quantum memories. Quantum 9, 1948 (2025).

Yu, T. & Eberly, J. H. Evolution from entanglement to decoherence of bipartite mixed “X” states. Quantum Inf. Comput. 7, 459–469 (2007).

Roa, L., Muñoz, A. & Grüning, G. Entanglement swapping for X states demands threshold values. Phys. Rev. A 89, 064301 (2014).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

Kesten, H. The critical probability of bond percolation on the square lattice equals 1/2. Commun. Math. Phys. 74, 41–59 (1980).

Wierman, J. C. Bond percolation on honeycomb and triangular lattices. Adv. Appl. Probab. 13, 298–313 (1981).

Malik, O. et al. Concurrence percolation threshold of large-scale quantum networks. Commun. Phys. 5, 193 (2022).

Duffin, R. J. Topology of series-parallel networks. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 10, 303–318 (1965).

Versfeld, L. Remarks on star-mesh transformation of electrical networks. Electron. Lett. 6, 597–599 (1970).

Zukowski, M., Zeilinger, A., Horne, M. A. & Ekert, A. K. “Event-ready-detector” Bell experiment via entanglement swapping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 4287–4290 (1993).

Bose, S., Vedral, V. & Knight, P. L. Purification via entanglement swapping and conserved entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 60, 194–197 (1999).

Kirby, B., Santra, S., Malinovsky, V. & Brodsky, M. Entanglement swapping of two arbitrarily degraded entangled states. Phys. Rev. A 94, 012336 (2016).

Hu, X. et al. Long-distance entanglement purification for quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 010503 (2021).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Purification of noisy entanglement and faithful teleportation via noisy channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 722–725 (1996).

Pan, J., Simon, C., Brukner, C. & Zeilinger, A. Entanglement purification for quantum communication. Nature 410, 1067–1070 (2001).

Pan, J., Gasparoni, S., Ursin, R., Weihs, G. & Zeilinger, A. Experimental entanglement purification of arbitrary unknown states. Nature 423, 417–422 (2003).

Martin, A. et al. Quantifying photonic high-dimensional entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 110501 (2017).

Kues, M. et al. On-chip generation of high-dimensional entangled quantum states and their coherent control. Nature 546, 622 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Quantum teleportation of multiple degrees of freedom of a single photon. Nature 518, 516–519 (2015).

Essam, J. W. Percolation theory. Rep. Prog. Phys. 43, 833–912 (1980).

Morikoshi, F. & Koashi, M. Deterministic entanglement concentration. Phys. Rev. A 64, 022316 (2001).

Newman, M. Networks: An Introduction. (Oxford University Press, New York, 2010).

Ma, J., Meng, X. & Braunstein, L. A. Peak fraction of infected in epidemic spreading for multi-community networks. J. Complex Netw. 10, cnac021 (2022).

Bar, A. & Mukamel, D. Mixed-order phase transition in a one-dimensional model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 015701 (2014).

Hébert-Dufresne, L. & Allard, A. Smeared phase transitions in percolation on real complex networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 013009 (2019).

Acknowledgements

H.W., J.H., and K.H. were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants No. 12271394, 12071336).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the research and discussions. H.W., J.H., and K.H. conceived the original idea of mixed-state concurrence percolation. H.W. and X.M. developed the mixed-state concurrence percolation theory. H.W. performed all numerical computations. H.W., O.M., and X.M. conducted the theoretical analysis. H.W. drafted the manuscript. X.M., O.M., Y.Z., K.H., and J.H. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

42005_2025_2459_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary information for “A Counter-Intuitive Low Entanglement Percolation Threshold in Mixed-State Quantum Networks”

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Malik, O., Hou, J. et al. A counter-intuitive low entanglement percolation threshold in mixed-state quantum networks. Commun Phys 9, 28 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02459-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02459-6