Abstract

Ultra-high power lasers are becoming important tools for advancing high-field physics and fusion research. However, their development is constrained by the damage thresholds of conventional optical components; it is challenging to design optical elements capable of withstanding high powers without them becoming impractically large. Here we show that transient plasma photonic structures, formed by the interaction of intercepting laser pulses in gas, can act as compact and robust reflective elements. Because these structures evolve in space and time, and rely on many interdependent parameters, designing optical components using traditional trial-and-error design methods is challenging. We show that machine learning can efficiently explore this complex parameter space to rapidly design robust, high reflectivity plasma mirrors. Moreover, this design process unexpectedly discovers a regime where unchirped laser pulses are compressed. This work demonstrates machine learning as a powerful tool for design, discovery and development of ultra-compact optical components for next-generation lasers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The size and cost of current and next-generation high-power lasers at facilities such as the Extreme Light Infrastructure (ELI)1 and APOLLON2, are predominantly determined by the dimensions of their optical components. Large, expensive optics are necessary to withstand high laser powers3. Plasma, in contrast, can tolerate orders of magnitude higher intensities ( ≈ 1 J cm−2)4, and is easily formed and replenished, which makes it an ideal medium for beam delivery and manipulation in high-power laser systems5. Beyond well-established mirrors based on overdense plasma, underdense plasma can be structured into volumetric dielectric Bragg gratings that act as effective optical elements.

These structures, known as transient plasma photonic structures (TPPS)6,7,8, are spatially periodic volumetric Bragg gratings, created by the beat waves of two or more intense “pump” laser pulses overlapping in plasma or gas9. TPPSs can function as ultra-compact, diffractive optical elements for manipulating ultrashort, high-intensity laser pulses, including mirrors10,11,12, compressors13 and waveplates. Their compactness and robustness make them promising candidates for scalable, cost-effective optical systems for future high-power lasers.

However, due to their inherently nonlinear dynamics, the formation and properties of TPPSs depend on a large number of laser and plasma parameters. Traditional design methods based on numerical simulations typically rely on extensive scans over multi-dimensional parameter spaces that often fail to capture parameter couplings. Varying one parameter can shift the optimal values, which makes exhaustive multi-dimensional scans prohibitively time-consuming except for very limited parameter sets and ranges.

More efficient and guided design approaches are therefore required, particularly for nonlinear spatio-temporal coupled systems, such as TPPS media. Machine learning (ML) optimisation algorithms14,15,16, and in particular Bayesian optimisation (BO)17,18, are well-suited to finding sample-efficient solutions of multivariate functions that require lengthy computations on each evaluation cycle. Recent advances have enabled BO to scale efficiently to large numbers of input parameters19.

In this work, we employ deep kernel Bayesian optimisation (DKBO)20,21,22,23, coupled to particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations, to design TPPSs for near-infrared wavelength high-power lasers. DKBO combines the representation-learning properties of neural networks (NNs)24 and the reliable uncertainty estimates of Gaussian processes (GP)25,26, enabling accurate surrogate modelling of complex, nonlinear parameter spaces. We demonstrate that DKBO can simultaneously optimise multiple parameters for different tasks, such as the reflectance, or the peak intensity of the backscattered probe, and that the improved surrogate model accuracy requires fewer iterations to find an optimum. The generality of the approach enables the number of optimisable parameters and objective functions to be readily extended to the design of other optical elements, such as waveplates, polarisers or focussing elements. Moreover, it can easily be adapted to an experimental setting where objective functions are determined from empirical measurements and detected signals, on every cycle.

Results

Transient plasma photonic structure formation

Plasma gratings can be formed by two mechanisms, both of which involve spatially modulated fields associated with the beat wave of one or more pairs of intercepting or counter-propagating pump laser pulses. In the first mechanism, layers of neutral plasma interspersed by layers of gas are created when the fields of the quasi-stationary beat wave exceed the photo-ionisation threshold of neutral gas.

The second mechanism, and the one used throughout this work, dominates when pump intensities are high. Here, the ponderomotive force associated with the beat wave displaces electrons, as illustrated in Fig. 1g–i, which, through their Coulomb fields, impart momentum to ions (see Fig. 1d–f) and cause them to inertially or ballistically evolve into a layered quasi-neutral plasma structure with a peak density that can exceed the critical density \({n}_{c}={\omega }_{0}^{2}{m}_{e}{\epsilon }_{0}/{e}^{2}\) (where ω0 is the pump frequency, ϵ0 is the vacuum permittivity, and me and − e are the electron mass and charge, respectively), as shown in Fig. 1c,l. The ponderomotive force of the beat wave of two identical pump pulses with frequency ω0 is given by \({F}_{p}=-{m}_{e}{c}^{2}\nabla ({a}_{0}^{2})/2\), where c is the speed of light in vacuum, and the normalised vector potential a0 of the pump pulses is related to their electric field strength, E0, by a0 = eE0/(meω0c). The ponderomotive force drives plasma electrons from high-intensity anti-nodes of the field, resulting in modulation of the electron density and momentum, while ions remain quasi-stationary. The resulting space-charge field imparts phase-correlated momenta to ions.

The vertically aligned panels represent the simulation at times t = 0.52 ps (a, d, g, j), 0.77 ps (b, e, h, k), and 1.08 ps (c, f, i, l). a Incident pump pulses (green) propagating towards the plasma slab located at ≈ 160 μm. b Quasi-stationary beat wave of the pump pulses (green profile) and start of plasma photonic structure formation (blue and red). The inset panel shows the density of electrons (blue) and ions (red) c Transmitted pump pulses (green) propagating towards their respective boundaries. d–f Two-dimensional histogram of ion momentum distribution. g–i Two-dimensional histogram of electron momentum distribution. j–l Number density of electrons (blue) and ions (red).

Electrons respond to the ponderomotive force in a time \({\tau }_{e}={\left({\omega }_{0}{a}_{0}\right)}^{-1}\approx\) 20–30 fs, while ions respond to the space charge-field of the electrons by gaining momentum and inertially form a grating after a time τi ≈ ωpi/(ωpea0ω0) ≈ ps, where ωpe and ωpi are the respective electron and ion plasma frequencies. The ion grating is partially neutralised by the more mobile electrons. Beyond the optimum bunching time, τi, the plasma photonic structure develops into a more complex periodic structure due to phase space evolution, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a–c, which strongly influences the permittivity and scattering efficiency of each layer in the TPPS.

Simulations and optimisation

A framework where numerical simulations are integrated with deep kernel Bayesian optimisation is employed to design plasma-based optical elements, while providing insight into the underlying physical system, which is achieved by exploring the parameter space through the most up-to-date surrogate model, trained at the final optimisation iteration (see Supplementary Figs. 5–7). In the first stage of the design cycle considered here, DKBO optimises simulations in one spatial dimension (1D) to gain an initial understanding of the system behaviour under various conditions and constraints. The optimised results are then extended to more realistic cases using two dimensional (2D) simulations, where further optimisation can be used to refine the solution, while providing further insight into phenomena observed in the initial 1D stage. With additional computational resources, simulations can be generalised to three dimensions (3D). This step-by-step approach leverages the strengths of optimising simulations using DKBO, while enabling efficient exploration of the design space, the identification of optimal solutions, and the discovery of new phenomena, as will be shown below.

Simulation setup

The first step of design optimisation is undertaken using 1D PIC simulations, as described above and in Methods. It should be emphasised that most of the laser and plasma simulation parameters are subject to optimisation, and the specific values chosen to describe the setup here result from this process. The model system comprises a homogeneous slab of under-dense plasma created by fully ionising hydrogen gas. The plasma slab, placed at the centre of the simulation box, has an initial density n0 = αdensitync, where nc is the critical plasma density. The factor αdensity is one of the seven optimisable parameters. This initial plasma slab is chosen to have ramps with a density varying as \({n}_{0}{\sin }^{2}(\pi x/(2{L}_{R}))\), at both ends, where LR = 2λ0 is the ramp length and λ0 = 800 nm ( = 2πc/ω0) is the pump wavelength. A second optimisable parameter is αplateau = Lplateau/λ0, where Lplateau is the length of the plasma plateau. 150 μ m vacuum regions in front of and behind the plasma slab ensure that the longest probe, with τ1 = 100 fs full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of intensity, can be diagnosed unambiguously. This plasma density distribution is an idealised, and perhaps unrealistic, density profile (see dash-dotted red line in Fig. 2a). A simple ramped plateau profile is used to demonstrate the DKBO algorithm, as it facilitates easier control of the size of the plasma target. However, more realistic 1D and 2D Gaussian initial plasma distributions, as described in Section 2, have also been used.

a Ion density at t = 0 ps (dash-dotted red) and at t = 1.12 ps (solid blue). b, c A 2λ0 section of the ion density profile at ≈ 190x/λ0 (b) and at ≈ 200x/λ0 (c) of the plasma photonic structure at t = 1.12 ps. d Evolution of the peak ion (solid orange) and electron (solid green) densities in the plasma slab. Vertical lines indicate the pump time T0 = 0.786 ps (dotted purple) and the snapshot time of the plasma photonic structure density profile at the probe-time T1 = 1.12 ps (dashed blue), respectively.

Following the creation of the plasma slab, two identical linearly polarised Gaussian-shaped pump pulses with τ0 = 100 fs FWHM of intensity, corresponding to an RMS duration of their field envelopes \({\tau }_{{\rm{RMS}}}={\tau }_{0}/\sqrt{2ln2}\), and peak intensity I0 = 1.52 × 1016 W cm−2 are launched towards the slab from the opposite boundaries of the vacuum regions, such that their front edges, 3 τRMS ahead of their respective centres, cross at t = 0. The parameters τ0 and I0 are chosen as free parameters for optimisation. The pump pulses counter-propagate along x and intercept within the plasma slab, where they initiate the formation of the TPPS density grating. Their centres cross the middle of the simulation box, \({x}_{{\rm{centre}}}\), at the pump time, \({T}_{0}=3\,{\tau }_{{\rm{RMS}}}+{x}_{{\rm{centre}}}/c\). For the optimised pump duration, T0 = 0.786 ps, is shown by the vertical dotted purple line in Fig. 2d.

As the pump pulses propagate towards the boundaries, a Gaussian probe pulse with wavelength λ1 = 800 nm is launched from the left boundary (x-minimum) and propagates towards the evolving TPPS density grating. Its polarisation is chosen to be orthogonal to that of the pump pulses, to enable the respective fields to be distinguished and, thus, the reflected and transmitted pulses to be unambiguously characterised, following interaction with the TPPS. The probe pulse is chosen to have an initial peak intensity I1 = 1.2 × 1017 W cm−2 and an initial duration τ1 = 55 fs FWHM of intensity, where I1 and τ1 are free parameters that are varied during optimisation.

The probe time, which is defined as the time at which the middle of the probe pulse crosses the centre of the simulation box, optimises for T1 = 1.12 ps. This is indicated by the vertical dashed blue line in Fig. 2d, and solid blue line in Fig. 2a-c, which show the ion density at t = 0 and t = T1 = 1.12 ps, respectively. The reflected probe propagates into the vacuum region towards the x-minimum boundary, where it is diagnosed, while the rest is transmitted through the TPPS, apart from small residual fields that are trapped in the plasma slab, and are either absorbed or radiate later.

Deep kernel Bayesian optimisation

Standard Bayesian optimisation is a sample-efficient method of optimising multivariate functions that are noisy or expensive to evaluate27. As the method is task-agnostic, it can be applied to a wide range of applications28. It has been successfully used to discover drugs29 and design materials30. It is also of interest for developing laser-plasma and conventional accelerators18,31.

A flow diagram depicting Bayesian optimisation and its application to an example test function are shown in Fig. 3. The goal of the algorithm is to evaluate the global maximum of an objective function ftrue(x) that depends on the input parameters \({\bf{x}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\). BO comprises two main components: a Bayesian statistical surrogate model of ftrue, and an acquisition function, which decides on the next sample point and encodes the propensity of the BO algorithm to balance exploration of the parameter space of x with exploiting regions of known good values of ftrue32.

a Conceptual flow diagram of Bayesian optimisation. In the deep kernel variant, the update to the surrogate model involves the joint training of the neural network and kernel parameters. b-d Optimisation iterations i = [1, 8, 11], respectively. The dashed red line represents ftrue. The surrogate model (mean) is represented by the dark solid blue line and the blue shaded areas represent the model’s confidence (standard deviation). The thin solid blue lines show functions sampled from the model’s posterior distribution. The purple dots indicate where measurements of ftrue have been made and the dash-dotted green line represents the acquisition function, the maximum of which (vertical dotted purple line) dictates the next sample point at iteration i + 1.

The first step involves evaluating the objective function ftrue at a number of points sampled using Sobol33,34 sequences that are drawn uniformly in linear space over the parameter bounds defined in Table 1.

The surrogate model, which is most often realised as a Gaussian process25,35,36, creates a Bayesian prior probability distribution of all possible values of the objective function. The model is then updated with each new observation of ftrue, yielding a new and more accurate posterior distribution.

The second step involves evaluating the acquisition function, using the posterior distribution over ftrue for the current optimisation iteration i, to determine the value that would result from sampling the objective function at a new point xi+1. Examples of popular acquisition functions used in BO are Expected Improvement (EI)37,38 and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB)39,40.

The use of Gaussian processes as surrogate models enables the integration of neural architectures into Bayesian optimisation. While standard GPs can model nonlinear functions through the choice of kernels, their expressiveness is often constrained by manually specified similarity measures. Deep Kernel Learning (DKL)26 addresses this limitation by combining the representation-learning capabilities of deep neural networks with the principled uncertainty estimation of GPs, yielding a powerful surrogate model for complex discovery and optimisation tasks such as design of TPPS optical elements.

In DKL, a deep neural network g maps the input matrix \({\bf{X}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n\times d}\) into a learned feature space \(\widetilde{{\bf{X}}}=g({\bf{X}},{\bf{w}})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n\times q}\), where n denotes the number of data points, d is the input dimensionality (matching the number of optimisable parameters), q is the dimensionality of the feature space and w denotes the network parameters. In our case, we use a fully-connected network architecture [d − 300 − 150 − q], where we empirically choose q > d, enabling the feature extractor to learn a richer, more expressive representation of the input space. This is particularly relevant in a Bayesian optimisation setting, where evaluations of the true objective function are expensive and data is scarce (i.e., n ≪ 1000). The GP in DKL provides a Bayesian regularisation effect that constrains the neural feature extractor. This coupling allows DKL to leverage the representational flexibility of deep networks without overfitting, and the higher-dimensional feature space can improve the model’s capacity to capture nonlinear dependencies.

A Gaussian process \({\mathcal{GP}}(m,k)\) is defined by a mean function m(X) and a covariance (or kernel) function k(X, X). Further information on GPs is provided in Supplementary Note 4. In DKL, the base kernel k is applied to the feature-space representation of the inputs:

This produces the covariance matrix \({\bf{K}}=k(\widetilde{{\bf{X}}},\widetilde{{\bf{X}}})\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{n\times n}\), with \({{\bf{K}}}_{ij}=k({\widetilde{{\bf{x}}}}_{i},{\widetilde{{\bf{x}}}}_{j})\).

We employ a constant mean function μ(x) = C, where C is a learned scalar parameter, and a Matérn kernel41 with smoothness parameter ν = 2.5, using automatic relevance determination (ARD). The base kernel k therefore includes hyperparameters \({\boldsymbol{\theta }}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{q}\), where q matches the dimensionality of the feature space vector \(\widetilde{{\bf{x}}}\).

At each Bayesian optimisation iteration, the parameters of the deep kernel \({\boldsymbol{\gamma }}=\{{\bf{w}},{\boldsymbol{\theta }},{\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2},C\}\) are trained jointly by maximising the log marginal likelihood (LML) of the GP:

where \({\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2}\) denotes the observation noise variance and I is an identity matrix. The first term penalizes model complexity by measuring the determinant of the covariance matrix, the second “data fit” term ensures that the model fits the observed data well.

This enables the model to adaptively learn task-specific representations of the input space, improving surrogate accuracy and optimisation performance in multi-dimensional design spaces. Deep kernel surrogate models can serve as drop-in replacements for standard GPs. The specific value of q is a tunable optimisation-level hyperparameter, where we observed that very low (q = 2) or very high (q = 150) feature space dimensionalities adversely affect optimisation performance. The full modified deep kernel Bayesian optimisation algorithm is described in Alg. 1; further details on the surrogate model and training are provided in Sec. The Deep Kernel Surrogate Model and Sec. Fitting, respectively. Lastly, a comparative analysis of DKBO versus standard BO, using PIC simulations, is given in Sec. Comparative Analysis, with a more comprehensive analysis available in Supplementary Note 5.

Optimising tasks

Here we demonstrate how a modified BO algorithm can efficiently optimise a deceptively simple task: the design of a TPPS mirror. Despite its apparent simplicity, the optimisation is complicated by the underlying nonlinear, spatio-temporal physics model, which exhibits complex interdependencies among input parameters.

In Bayesian optimisation, the objective function, accuracy of the surrogate model, and choice of acquisition function have equal importance. Multiple optimisation objectives represent tasks in this work, which can be used to minimise TPPS formation time, or maximising its persistence. Tasks in single-objective optimisation are expressed as metric functions, which may combine multiple goals into a weighted sum, or include penalty terms to discourage undesired outcomes. For example, reflectivity can be optimised while penalising an increase in the full-width-at-half-maximum of the reflected pulse. The weights act as optimisation hyper-parameters, which often require manual tuning, involving trial-and-error campaigns.

More versatile approaches such as multi-objective optimisation42 directly model and explore the trade-off between objectives. Rather than combining separate objectives into a single scalar value, these methods identify the Pareto front, which is the set of non-dominated solutions where improving one objective necessarily degrades another. However, in the work considered here, we explore the use of constrained and unconstrained single-objective optimisation, deferring the application of multi-objective techniques to future studies.

The first optimisation task considered here is maximising the total energy reflected, which is chosen as an objective function. Clearly identifying the objective function is important for ensuring that the results are meaningful. For example, maximising the energy reflected aims to determine the global maximum. Alternatively, constraining the objective function to a fixed value enables the design of a beam splitter of arbitrary reflectance and transmittance.

The adaptability/flexibility of TPPS media is exemplified by the plasma mirror model. While it is expected that the reflected energy should not exceed the incident energy, the peak intensity can be higher than the intensity of the incident pulse. This shows that the choice of the objective function is very important in task optimisation and can result in surprising “solutions” e.g., by defining an objective function that maximises the peak intensity of the reflected pulse, the algorithm “discovers” a method of highly-efficient pulse compression resulting from the TPPS acting as a time-boundary43. This shows that reflecting the maximum probe energy off a TPPS does not only create a mirror, but also allows for changes in the pulse duration and wavefront, which underscores the importance of selecting objective functions for discovery. New phenomena can emerge through optimisation of well-chosen tasks, as will be discussed in Section 2. In these cases there is no a priori knowledge of the new phenomena being discovered.

Optimising the reflected energy

The efficiency of reflecting the probe energy is optimised by maximising the unconstrained objective function

where Ip and Ir are the intensities of the incident and reflected probe, respectively, given by I = ∣E∣2cϵ0η/2, where E is the electric field and η is the refractive index. All “measurements” are made in the vacuum region between x-minimum and the plasma block where η = 1, at an appropriate time defined as \({T}_{1}\pm ({x}_{{\rm{centre}}}/2)/c\) for the incident and reflected probe, respectively.

The optimisation algorithm maximises ftrue by simultaneously varying the seven input parameters defined in Table 1. The seven-dimensional optimisation process is initiated by drawing and evaluating eight Sobol samples, which are followed by up to a further 50 optimisation-guided evaluations. The modified BO algorithm consistently converges on an optimal reflectance above 99% in ≈ 20 iterations, while the remaining iterations explore the parameter space in the vicinity of the optimal value. Figure 4a presents a 1D PIC simulation, which is the outcome of DKBO, showing the intensity envelopes of the incident and reflected probe pulses, and a snapshot of the TPPS ion density profile at probe time T1.

Optimised incident (dashed red) and reflected/transmitted (dot-dashed blue) pulses and the plasma photonic structure (solid green). The colour-coded arrows indicate the propagation direction of the pulses and the plasma grating is shown at the time of reflection. a Plasma photonic structure resulting in > 99% total energy reflected. b Plasma photonic structure resulting in 173% peak intensity of the reflected pulse, due to pulse compression. c Plasma photonic structure acting as a beam-splitter, resulting in ≈ 50% total energy reflected and transmitted.

The dash-dotted red line in Fig. 2a shows that the initial density n0 converges to an initial value close to 0.3 nc8. Note that densities above nc/4 suppress the Raman instability. Moreover, the algorithm determines the optimal timing, T1, of the probe pulse, as indicated by the vertical blue dashed line in Fig. 2d, to coincide with the time when the ion and electron densities reach their peak values.

The TPPS comprises counter-propagating peaked density substructures with a periodicity of ≈ λ0/2. At the centre of the plasma slab, their velocities are opposite and equal, averaging to zero (see Supplementary Fig. 8a, b), and they overlap simultaneously to form high-density peaks, as shown in Fig. 2c, creating an ideal Bragg structure for most efficient reflection. However, reflection takes place near the incident boundary (see Supplementary Fig. 8d), where the substructures “concertina” due to the ponderomotive force associated with the beat of the incident and the reflected probe. We conjecture that the resulting net velocities of the high-reflectivity peaks in the direction of the incident probe lead to the Doppler downshift on reflection shown in Fig. 5a.

Three-column figure showing spectrum (a–c) and spectral phase (d–f) for simulations with 99% energy (a, d), ≈ 50% energy (b, e) and 173% increase of peak intensity (c, f) reflected. a–c Spectral power density of the incident (solid red) and reflected (dot-dashed blue) pulses, showing spectral broadening and a downshift in central frequency (green dashed line indicates ω). The spectral downshift results from Doppler shifts on reflection inside the plasma photonic structure, whereas the difference in height of the incident pulses is attributed to their optimised amplitudes. d–f Unwrapped spectral phase difference (solid purple) of the incident and reflected probe pulses. The arbitrary phase offset due to the delay between the incident and reflected pulses has been removed by subtracting the phase at the spectral peak frequency for each pulse.

Examining the parameter choices made by the algorithm, we see from Fig. 2a and column “99% [E]” in Table 1 that the algorithm maximised the length of the plasma plateau by setting αplateau = 20.0. We conducted optimisations where we doubled the upper bound for αplateau to 40, with the aim of confirming whether the parameter previously converged to its optimum within ≈ 20 iterations. Upon examining the αplateau evaluations, we confirmed that values between 20 and 23 are most frequently chosen by DKBO (in ≈ 50% of evaluations). However, the algorithm can reach an optimum reflectance with αplateau values chosen at either end of the parameter range, by varying the values of the other six parameters. For example, an alternative 99% configuration with a shorter plateau length (αplateau = 7) is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

To demonstrate a more challenging optimisation scenario, we have used DKBO to design a 50% beam-splitter by constraining Eq. (4) not to exceed 50%, while keeping the same parameter ranges and simulation set up as previously used. The constrained objective function is expressed as:

The algorithm finds an optimal configuration of ≈ 50% reflection efficiency in ≈ 20 iterations. Fig. 4c shows the intensity envelopes of the incident, reflected and transmitted pulses for this optimisation study. An optimum is produced by advancing the time at which the probe pulse enters the plasma slab, i.e. T1 = 0.85 ps. Again, the algorithm converges on an optimum initial plasma density close to 0.3 nc, as shown in column “50% [E]” of Table 1.

During the reflectance optimisations, we observe that with exploitative configurations (β = 0.1) of the Upper Confidence Bound acquisition function, expressed as \(\,{\rm{UCB}}\,(x)=\mu (x)+\sqrt{\beta }\sigma (x)\), the algorithm does not deviate from an optimum value when it has been discovered. However, this is not always desirable, as a local maximum may have been found. On the other hand, we find that the Expected Improvement acquisition function tends to explore the parameter space more in areas of high uncertainty, even after it has found an optimal value. Obtaining similar performance from UCB is possible, but requires careful task-specific fine-tuning of the hyper-parameter β, responsible for the trade-off between exploration and exploitation.

Optimising the peak intensity of the reflected pulse

Plasma photonic media can be customised to many different roles simply by devising new objective functions. Another example is maximising the peak intensity of the reflected pulse using the objective function

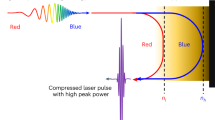

where Ip and Ir are the intensities of the incident and reflected probe pulses, respectively. As discussed in Section 2, choosing an appropriate objective function without a constraint leads to a peak intensity of the reflected pulse that is higher than the incident pulse. This may come as a surprise, but on further examination it can be shown to be due to pulse compression.

The seven parameters are varied within the ranges given in Table 1. Following the eight Sobol initialisation points, the algorithm performs a further 50 evaluations of the objective function. In this case, an optimal peak reflected pulse intensity of 173% of the incident pulse is found, with an intensity FWHM of ≈ 41 fs (reduced from the incident 83 fs), which is illustrated in Fig. 4b. Even in this case, the plasma photonic structure is a very efficient scatterer and reflects ≈ 99% of the incident energy. This example demonstrates the discovery of properties that can lead to transformational technological advances. A simulation giving a slightly lower peak of 165% reflected pulse intensity and ≈ 40 fs FWHM (reduced from the incident 70 fs), using parameters from a prior optimisation, is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

When the peak intensity is optimised, the timing of the incident probe pulse relative to the pump pulses is delayed until well after the electron and ion densities have peaked, but the permittivity continues to vary spatially and temporally, which results in compression, as will be discussed below. Unlike compression of a chirped probe pulse5,13, here the incident pulse is not chirped. The temporal compression of the incident Fourier transform-limited pulse implies an increase in spectral bandwidth, as shown in Fig. 5c. This is attributed to Doppler shifts during the distributed reflection of the probe pulse at moving plasma layers and the spatio-temporal evolution of the permittivity, which constitutes a time-boundary.

Like in the case described in subsection 2, the probe pulse is reflected in the incident boundary region, see Fig. 6d, but during the longer period before its arrival, here the TPPS evolves into a more complex structure, where the crossings of the counter-propagating density peaks at different positions no longer occur simultaneously and have different net velocities, see Fig. 6b. We conjecture that this, together with ponderomotively driven “concertinaing”, leads to partial reflections of the probe with different Doppler downshifts. The “concertinaed” layers seen in Fig. 6a,b,d are similar to those in chirped mirrors, which can introduce group delay dispersion. This results in the spectral broadening of the reflected probe that is required for the observed compression.

a Full spatio-temporal evolution of the plasma photonic structure electron density, with pump and probe arrival times (T0 = 0.66 ps and T1 = 1.30 ps) indicated by gold dotted and white dashed lines, respectively. b Magnified region (between ≈ 187 and 195 μm) of the plasma photonic structure, showing the evolution of the electron density (ne/nc) around the probe arrival time (T1 = 1.30 ps; white dashed line). c Temporal evolution of the probe spectrum, calculated over the full spatial range of the plasma photonic structure, and centred around the incident probe’s vacuum frequency, indicated by the dot-dashed red line. d Probe energy density (ϵ0cE2/2) in the same region as panel b (between ≈ 187 and 195 μm), overlaid with the plasma photonic structure electron density profile at T1 = 1.30 ps.

Having obtained the optimal configuration for compression, we manually varied selected parameters, whilst keeping the others fixed, to analyse their effect on the objective function. E.g., two important optimisation parameters are αplateau = Lplateau/λ0 and the density factor αdensity. Optimising the peak reflected intensity yields αplateau ≈ 13 and αdensity = 0.47; the latter is close to the parameter limit of 0.5. However, an increase in intensity is not observed for simulations with either n0 = 0.3nc or αplateau = 26, without changing any other parameters.

A further sensitivity analysis of the results from Table 1 is provided in Supplementary Note 3, which shows that the TPPS does not reflect short (10 fs) pulses effectively because of its limited bandwidth. This bandwidth constraint applies to most of the designs presented here, but could potentially be overcome with optimisations using a wider range of parameters, such as pump and probe laser pulse chirps, plasma profile shapes etc.

1D and 2D studies including ionisation and realistic plasma profiles

The design of the TPPS optical elements described in Section 2 are validated using more experimentally realistic plasma/gas density profiles, which are approximated by a Gaussian distribution in 1D, with an integral along the longitudinal (x) direction equal to that of the ramped plateau profile. The same optimal laser and plasma density values have been used from column “99% [E]” in Table 1 with the modified initial plasma distribution, which give a reflectance greater than 98% (see Supplementary Fig 4). Further ML optimisation in 2D to refine the design were not carried in our study because of limited computer resources.

2D simulations were, however, undertaken using the optimal parameter sets defined in Table 1 to compare with the 1D studies. More realistic 2D simulations require additional parameters to describe the initial wavefront and focussing of the pulses. They include diffraction and refractive changes to the wavefronts during propagation, and ionisation.

The counter-propagating pump pulses are launched from the boundaries focussing to a common 10 μ m spot at the centre of the gas slab. Following ionisation and formation of the TPPS by inertial bunching, the probe pulse is launched and focused to a 5 μ m spot coinciding with the pump foci.

The TPPS can also be tailored into a spherical mirror comprising spherical layers. This is achieved by displacing the co-located focal positions of the pump pulses to create curved (spherical) fronts of the pump beat wave in the plasma medium, which results in a spherical mirror with a focal length determined by the pump laser focal lengths and position of the pump foci. Indeed, even in the case of the pumps focussed at the centre of the gas slab the plasma layers formed are curved at the entrance and exit of the TPPS, giving rise to focussing or defocussing as shown in Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figs. 9–11.

The parameters of the plasma photonic structure were optimised in 1D, with αplateau = 20.0 in x and 3αplateau in y. The arrows in panels a and c indicate the propagation direction of the pulse. a Incident probe pulse, orthogonally polarised with respect to the pump pulses, propagating towards the plasma photonic structure, as it is still forming. b Reflection off of the plasma photonic structure. The inset panel shows the layers of the plasma grating and the pulse. c Reflected pulse propagating towards the boundary and the plasma photonic structure after reflection.

To investigate the role of ionisation in the formation of the TPPS optical elements, simulations were run applying the EPOCH PIC code’s44 simple ionisation model to an initial hydrogen gas density distribution, comprising a ramped plateau with a longitudinal (x) size identical to those described in Table 1 and transverse (y) width triple the size in x. Simulations utilise the two previously optimised plateau sizes of αplateau = 20.0 and αplateau = 7.0, and probe spot sizes of 5–10 μ m. The values of αplateau and the 2λ0 ramp lengths are obtained from previous unconstrained 1D total reflected energy optimisations, as described in Section 2.

In all 2D cases, the TPPS reflects the probe pulse with an efficiency of over 99%. Moreover, the probe pulse is observed to be weakly focused following reflection, as can be seen by comparing Fig. 7a with Fig. 7c. This arises from the spatio-temporal distribution of the pump pulses, which introduce a small radial dependence in the phase. Further 2D generalisations of the results from Sections 2 and 2 are shown in the Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10, respectively. Finally, we investigated a 2D radial Gaussian distribution for the optimised 99% reflectivity parameters. Again, the reflected energy exceeds 98%. As in the 1D Gaussian distribution simulation, we observe a distortion of the pulse on reflection, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11e. Eliminating this distortion would be a valid goal for future 2D optimisations involving Gaussian density distributions with the reflected pulse shape or FWHM metric given as a penalty factor in the optimisation.

Comparative analysis

We compare the performance of the Deep Kernel Bayesian Optimisation algorithm with standard Bayesian optimisation omitting the [d − 300 − 150 − q] neural network feature extractor. In both cases, the Gaussian process surrogate uses a Matérn kernel (see Eq. (7)) with ν = 2.5, automatic relevance determination, and a constant mean function.

The comparison considers three aspects: (i) the optimum value found during optimisation, (ii) the number of iterations required to reach it, and (iii) the computational cost per iteration.

To quantify optimisation performance, we use the simple regret at iteration i, defined as

where x* is the location of the global optimum of the objective function, and xj are the input locations queried up to iteration i. This metric measures the gap between the true global maximum and the best value observed so far, with ri = 0 indicating convergence. As the global maximum for the three metric functions is unknown, for each matched pair of runs we calculate regret relative to the better of the two observed maxima, so that curves are directly comparable within each subplot. In addition, we record the surrogate training time at each iteration to evaluate the computational overhead introduced by the neural network feature extractor, as well as the time taken by the simulations.

This study was conducted for all three metric functions and parameter ranges described in Table 1. Each optimisation was initialised with eight randomly sampled points, followed by an additional 20 Bayesian optimisation iterations (see Fig. 8). An additional, more comprehensive, study can be found in Supplementary Note 5, where we compare BO with DKBO for a variety of standard benchmark functions with varying parameter space landscapes.

a–c Log-scale runtime comparison between standard surrogate model fits (dashed red) and simulations (dashed orange), and deep kernel surrogate model fits (solid blue) and simulations (solid green). The difference in line length is due to the lack of surrogate model training during the eight initialisation simulations. d–f Symmetric log-scale simple regret progression for each matched pair, computed relative to the better of the two observed maxima in that pair. Results are shown for the beam splitter (a, d), total energy reflected (b, e), and peak intensity (c, f) objective functions.

Reviewing the simple regret plots in Fig. 8d–f, we observe that the DKBO algorithm avoids being trapped in a local minimum, and is able to improve upon the best result by a large factor in a few tens of iterations.

In the 50/50 beam-split task (Fig. 8d), both methods initially reduce regret, but the vanilla BO surrogate becomes trapped in a local optimum, while DKBO continues to improve, ultimately converging to the global optimum by the ≈ 20th iteration.

Examining the energy-reflection task in Fig. 8e, both methods reach an optimum of ≳ 99% during the initialisation stage; DKBO yields a small additional improvement by the ≈ 20-th iteration. We attribute this early optimum discovery to the metric-function landscape for this task, which exhibits broad regions of near-optimality over much of the parameter space (see Supplementary Fig. 5).

In contrast, for the peak-intensity task (Fig. 8f), DKBO shows better performance. As seen in Supplementary Fig. 7, the landscape here contains localised optima, due to the complex spatio-temporal plasma-mirror dynamics, making optimisation more difficult. The improved performance of DKBO is consistent with the upstream feature extraction to q = 50, which, together with ARD in the Matérn kernel, can yield a more expressive covariance in the transformed space.

Lastly, we examine the effect that the neural-network feature extractor has on the training time of surrogate model at each optimisation iteration. As seen by the blue line in Fig. 8a-c, training times increase by ≈ 5 − 10 seconds. However, we still observe that the main computational bottleneck, across all three metrics, is the runtime of the PIC simulations, which are orders of magnitude longer.

Conclusions

In this work, we have applied a new deep kernel ML approach for optimising a TPPS to design optical elements such as mirrors. Neural networks that are part of the Bayesian surrogate model enable rapid optimisation of the reflectivity of TPPS optical elements. We demonstrate how the reflected energy or the peak intensity of the reflected probe pulses can be optimised. This can be extended to laboratory experiments, where real-time optimisation is achieved using suitable objective functions derived from real-time measurements. Examining the choices that the algorithm makes to achieve convergence, as well as the surrogate model posterior, enables insight to be gained into the role of parameters (such as laser intensity and plasma density) relevant to a particular optical element.

We show that it is straightforward to extend optimisation to focussing optical elements using 2D simulations. This demonstrates that designs can be efficiently optimised in 1D prior to being transferred to 2D, where they can be further refined or modified to the design a variety of optical elements, e.g., a focussing element, beam splitter or a plasma mirror for improving contrast. The method paves the way for future applications of DKBO in the area of laser-matter interactions and can be applied to other physical models and real-time experimental optimisation.

A very powerful use of the optimisation tool is for “discovery”, which has been demonstrated by judicious choice of an objective function to create a TPPS compressor of unchirped incident pulses. This is due to the spatio-temporal evolution of the TPPS and complex structures that act as time boundaries and introduce Doppler frequency shifts and spatially chirped layers. Finally, incorporating multi-objective and multi-fidelity optimisation, through adaptive variation in simulation resolution and domain size, promises to enhance efficiency, scalability, and convergence rates across simulation dimensionalities, while also yielding optimal solutions and their trade-offs across multiple objectives.

Methods

Particle-in-cell simulations

Simulation configurations

1D simulations were initially configured to run with 32 particles-per-cell (PPC) and 40 cells-per-laser-wavelength (CPW) to enable rapid prototyping of 1D reflectivity mirrors and their optimisation. It was observed that optimisation of total energy reflected and peak intensity hardly changed with an increase in PPC and CPW.

However, optimisations of the 50-50 beam splitter required an increase in PPC and CPW because the initial, locally optimised result using 32 PPC and 40 CPW shifted from 50-50 reflectivity-transmission split to an approximately 60-40 split for higher PPC/CPW counts on the ARCHER2 UK National Supercomputing Service45. Increasing the PPC/CPW values to 500 cells-per-laser-wavelength and 2048 particles-per-cell modelled the TPPS dynamics more accurately.

Another optimisation was undertaken using these higher PPC/CPW values and the 50-50 reflectivity metric on ARCHER2 converged upon the results presented in Table 1 (column 50%[E]). Furthermore, to ensure that all 1D results were optimal, regardless of the objective function, we tested all results from Table 1 using the increased PPC/CPW values. This further emphasises how multi-fidelity optimisation techniques would be useful to mitigate the uncertainties of results from low PPC/CPW simulations, whilst also reducing the time required for a full optimisation run.

To avoid excessive computation, simulations are configured to finish \({x}_{{\rm{centre}}}/c\) after the probe time T1, whilst still enabling the probe to be fully analysed, following reflection. The initial temperature of the plasma is set to Te = 5eV and Ti = Te/10 for electrons and ions, respectively.

Simulation output and objective function calculations

Each simulation input deck contains two output blocks: One generates frames for creating videos to follow the time evolutions of laser and plasma. Simulations are split into snapshots to give sufficient temporal resolution to monitor the evolution structure and the interaction of the probe pulse with the TPPS. The second output block generates data for objective function calculations. This results in data dumps at regular intervals before and after the probe time T1. Sample 2D snapshots are shown in Fig. 7a-c. Timing the snapshots enables integration of the incident, reflected, and transmitted probe fields to determine their respective energies in the vacuum region away from the plasma. The simulation analysis is performed using the SciPy46 and NumPy47 Python modules. They provide the necessary tools for manipulating simulation data and enabling calculations of the objective functions.

Technical details, computational resources and runtimes

The simulations used in this work have been performed using versions v4.17 and v4.19 of the EPOCH PIC code, which have slight differences in the way ionisation is handled and the “species” blocks describing the initial conditions.

PIC simulations represent plasma by macro-particles and calculate the electromagnetic fields from their charges and currents on a grid (in one, two, or three dimensions). To compute the motion and, where applicable, ionisation of macro-particles, interpolated fields are used. A limitation of the PIC method is that collisions between macro-particles are not well modelled.

Locally, we conducted prototyping of small-scale optimisations and simulations using a 12-core Apple M2 Pro processor (eight performance, four efficiency), operating at 3.5 GHz and with 32 GB of RAM. Employing the (PPC = 32, CPW = 40) configuration, EPOCH1D simulations took approximately 40 seconds when executed using the eight performance cores. Subsequently, a comprehensive optimisation was completed, averaging less than an hour. The primary computational bottleneck, even for the most basic configuration, is attributed to the PIC simulations. The GP fitting, despite not benefiting from GPU acceleration and incorporating the additional parameters w of the feature-extractor g, still concluded more quickly than the simulations (in approximately 15 s), as shown in Fig. 8a–c.

This disparity between GP-fit and simulation execution times was further amplified when transferring the optimisation to HPC systems, such as the previously mentioned ARCHER2 UK National Supercomputing Service. ARCHER2 is equipped with 5860 compute nodes, each with two AMD EPYC 7742 processors, operating at 2.25 GHz, with 64 cores, and 256 GB of RAM. Utilising the higher (PPC = 2048, CPW = 500) resolution parameters, on eight compute nodes, the EPOCH1D simulations concluded, on average, within approximately 50 min. ARCHER2 lacks NVIDIA GPUs, necessitating CPU-based training of γ. We observed a reduction in training speed, which we attribute to the lower single-core performance of the AMD EPYC chip.

We introduced additional compute nodes for the simulations, which resulted in diminishing returns in terms of runtime at the expense of increased budget allocation. Furthermore, for the high CPW/PPC values, when employing more than 10 compute nodes, the optimisation runtime was adversely impacted. We attribute this slowdown to inter-process communication required between nodes, which can introduce an overhead. Similar behaviour was also observed locally, when running simulations on 12 cores of the M2 Pro, where the inclusion of the 4 efficiency cores into the combination of performance cores resulted in a doubling of the simulation time, due to the difference in clock-speed.

The deep kernel Bayesian optimisation algorithm

The optimisation algorithm, described in Alg. 1, the surrogate model, and the analysis functions are all written in Python.

Algorithm 1

Deep-kernel Bayesian optimisation

Require: Search space \({\mathcal{X}}\), objective function \({f}_{{\rm{true}}}:{\mathcal{X}}\to {\mathbb{R}}\), feature extractor g, Gaussian process \({\mathcal{GP}}(k,m)\), acquisition function α, initialisation budget η, evaluation budget N

Ensure: Best observed x* and y*, and trained surrogate

1: function DKBO\(({\mathcal{X}},\,\eta ,\,N)\)

2: Generate initial samples X ← SOBOL\(({\mathcal{X}},\,\eta )\)

3: Evaluate samples \({\bf{y}}\leftarrow {\{{f}_{{\rm{true}}}({{\bf{x}}}_{i})\}}_{i=1}^{\eta },\,{{\bf{x}}}_{i}\in {\bf{X}}\)

4: Initialise best values \({{\bf{x}}}^{* }\leftarrow {{\bf{X}}}_{\arg \max ({\bf{y}})},\,{y}^{* }\leftarrow \max ({\bf{y}})\)

5: for j ← η + 1 toN do ⊳ Main optimisation loop

6: \(\widehat{{\bf{X}}}\leftarrow\) NORMALISE(X)

7: \(\widetilde{{\bf{y}}}\leftarrow\) STANDARDISE(y)

8: \({{\mathcal{GP}}}_{{\rm{DK}}}\leftarrow\) CREATEANDFIT(\(\widehat{{\bf{X}}},\widetilde{{\bf{y}}},g\)) ⊳ Joint training of \({\boldsymbol{\gamma }}=\{{\bf{w}},{\boldsymbol{\theta }},{\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2},C\}\), see Sec. Fitting

9: Next query point \({{\bf{x}}}_{j}\leftarrow \arg \mathop{\max }\limits_{{\bf{x}}\in {\mathcal{X}}}\alpha ({{\mathcal{GP}}}_{{\rm{DK}}})\)

10: Evaluate parameters yj ← ftrue(xj)

11: Update data X ← X ∪ {xj}, 7D1y ← y ∪ {yj}

12: Update best values \({{\bf{x}}}^{* }\leftarrow {{\bf{X}}}_{\arg \max ({\bf{y}})},\,{y}^{* }\leftarrow \max ({\bf{y}})\)

13: end for

14: return \({{\bf{x}}}^{* },{y}^{* },{{\mathcal{GP}}}_{{\rm{DK}}}\)

15: end function

The deep kernel surrogate model

We implement the surrogate model using the “SingleTaskGP” module from BoTorch28, which is built on top of GPyTorch48 and PyTorch49. The model combines a Gaussian process with a learnable neural-network-based feature extractor g. The neural network g is a fully connected feed-forward network with Rectified Linear Unit (\(\,{\rm{ReLU}}\,(x)=\max (0,x)\)) activations after each hidden layer, except for the final output layer. Dropout regularisation is not applied, in order to retain determinism and simplify the training of the surrogate in the low-data regime.

Our architecture differs from that used in the original DKL paper, which utilised deep networks of the form [d − 1000 − 500 − 50 − 2] for regression tasks with datasets of n < 6000 and larger a [d − 1000 − 1000 − 500 − 50 − 2] architecture for n > 6000. In contrast, Bayesian optimisation is explicitly designed for sample efficiency, and, in our application, the number of function evaluations is typically in the range n = [30, 100]. To reduce the risk of over-fitting and the time taken to train, whilst still allowing for sufficient feature extraction, we employ a more compact architecture than the one used for n < 6000. As such, our network comprises just two hidden layers of sizes 300 and 150, respectively, leading to a final output dimensionality of q = 50, resulting in the architecture [d − 300 − 150 − 50] with d = 7.

The choice of q = 50 was guided by both empirical validation and recent work in the literature such as in “Deep Kernel Bayesian Optimisation”20, Bowden et al. who argue that a larger feature-space dimensionality allows for more expressive representations to be passed to the base GP kernel. Furthermore, due to the small number of data points usually available for training, the authors hypothesise that relevant information may be lost when mapping the inputs into a lower-dimensional space (q < d), but that also a much larger feature space dimensionality might adversely affect performance (q ≫ d). We explored a range of values q ∈ {2, 10, 25, 32, 50, 100, 150} and observed that moderate expansion (d < q ≲ 50) consistently resulted in faster convergence during optimisation. In contrast, very small q tended to overly compress the representation, while excessively large q increased training time and introduced instabilities.

The effects of the feature extractor architectures are directly observable in the simple regret plots in Supplementary Figs. 12–14. These plots compare our proposed architecture against a similar but smaller network with layer sizes of \(\left[d-128-64-{q}^{{\prime} }\right.\), where \({q}^{{\prime} }=32\). The larger network sizes and feature-space dimensionality consistently outperform the DKBO approach that utilised the smaller network architecture.

The base kernel chosen is the Matérn kernel

where Γ is the gamma function, Kν is the modified Bessel function of the second kind, ∥xi − xj∥, representing the Euclidean distance, scaled by the learnable length scale parameter l. The symbol ν ∈ [0.5, 1.5, 2.5] denotes a smoothness parameter. In our approach, we chose the value ν = 2.5.

We also employ Automatic Relevance Determination, which assigns a separate length-scale to each input dimension of the kernel. In our case, this results in the Matérn kernel learning q = 50 individual length-scales (one per feature extracted by the neural network). This richer representation enhances the model’s flexibility, allowing it to assign relevance differently across a wide range of learned features, compared to using a compressed feature space, such as the originally proposed q = 2.

Fitting

Following data initialisation, at each optimisation iteration, the first step involves min–max normalisation of X with respect to its bounds:

followed by standardisation of the target values y to zero mean and unit variance.

The complete set of trainable parameters in the DKL surrogate is denoted by \({\boldsymbol{\gamma }}=\{{\bf{w}},{\boldsymbol{\theta }},{\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2},C\}\), where w are the parameters of the neural network g, θ are the hyperparameters of the Gaussian process kernel, \({\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2}\) is the observation noise variance, and C is a learned constant mean parameter. Training proceeds by maximising the log marginal likelihood (see Eq. (2)) of the GP with respect to all parameters, jointly. This enables the model to learn feature representations \(\widetilde{{\bf{X}}}=g(\widehat{{\bf{X}}},{\bf{w}})\) that are most useful for constructing an accurate and well-calibrated surrogate model in the feature space.

The gradient of the log marginal likelihood \({\mathcal{L}}\) with respect to γ is computed via the chain rule:

For each Bayesian optimisation iteration, we initialise a new surrogate model. That is, we do not warm-start the GP or neural network from previous iterations. While this incurs a higher per-iteration computational penalty, it prevents potential bias accumulation and allows the surrogate to adapt more flexibly as the dataset for the i-th BO iteration, \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{i}={\{{{\bf{x}}}_{j},{y}_{j}\}}_{j=1}^{i-1}\), grows. This training procedure is repeated at every BO step as part of the acquisition optimisation loop. The optimiser used for this is Adam50, with a learning rate of 1 × 10−3 and no weight decay for all parameters in γ. An exponential moving average stopping criterion with a window size of 10 and tolerance of 1.0 × 10−5 is used when fitting the surrogate model to further avoid over-fitting.

Data availability

Data associated with the paper can be found at https://doi.org/10.15129/d177195e-8119-42a5-aaca-2c33d922b01d.

Code availability

The code used to generate data is available from the authors upon request.

References

Le Garrec, B. et al. Eli-beamlines: Extreme light infrastructure science and technology with ultra-intense lasers. Proc.of SPIE - The International Society for Optical Engineering 8962 (2014).

Apollon research infrastructure. https://apollonlaserfacility.cnrs.fr/.

Tien, A.-C., Backus, S., Kapteyn, H., Murnane, M. & Mourou, G. Short-pulse laser damage in transparent materials as a function of pulse duration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3883–3886 (1999).

Mirza, I. et al. Ultrashort pulse laser ablation of dielectrics: Thresholds, mechanisms, role of breakdown. Sci. Rep. 6, 39133 (2016).

Hur, M. S. et al. Laser pulse compression by a density gradient plasma for exawatt to zettawatt lasers. Nat. Photonics 17, 1074–1079 (2023).

Vieux, G. et al. The role of transient plasma photonic structures in plasma-based amplifiers. Commun. Phys. 6, 9 (2023).

Lehmann, G. & Spatschek, K. H. Plasma photonic crystal growth in the trapping regime. Phys. Plasmas 26, 013106 (2019).

Lehmann, G. & Spatschek, K. H. Transient plasma photonic crystals for high-power lasers. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Plasma Science (ICOPS) 1–1 (2016).

Sheng, Z., Zhang, J. & Umstadter, D. Plasma density gratings induced by intersecting laser pulses in underdense plasmas. Appl. Phys. B 77, 673–680 (2003).

Monchocé, S. et al. Optically controlled solid-density transient plasma gratings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 145008 (2014).

Lehmann, G. & Spatschek, K. H. Laser-driven plasma photonic crystals for high-power lasers. Phys. Plasmas 24, 056701 (2017).

Lehmann, G. & Spatschek, K. H. Reflection and transmission properties of a finite-length electron plasma grating. Matter Radiation at Extremes 7, 054402 (2022).

Lehmann, G. & Spatschek, K. H. Plasma-grating-based laser pulse compressor. Phys. Rev. E 110, 015209 (2024).

Radovic, A. et al. Machine learning at the energy and intensity frontiers of particle physics. Nature 560, 41 – 48 (2018).

Emma, C. et al. Machine learning-based longitudinal phase space prediction of particle accelerators. Phys. Rev. Accelerators Beams 21, 112802 (2018).

Feehan, J. S., Yoffe, S. R., Brunetti, E., Ryser, M. & Jaroszynski, D. A. Computer-automated design of mode-locked fiber lasers. Opt. Express 30, 3455–3473 (2022).

Duris, J. et al. Bayesian optimization of a free-electron laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124 12, 124801 (2019).

Shalloo, R. J. et al. Automation and control of laser wakefield accelerators using bayesian optimization. Nat. Commun. 11, 6355 (2020).

Hvarfner, C., Hellsten, E. O. & Nardi, L. Vanilla Bayesian optimization performs great in high dimensions. Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning, 235, 20793–20817, (PMLR, 2024).

Bowden, J., Song, J., Chen, Y., Yue, Y. & Desautels, T. Deep kernel bayesian optimization. Tech. Rep., Lawrence Livermore National Lab.(LLNL), Livermore, CA (United States) (2021).

Gayon-Lombardo, A., del Rio-Chanona, E. A., Pino-Muñoz, C. A. & Brandon, N. P. Deep kernel Bayesian optimisation for closed-loop electrode microstructure design with user-defined properties. Energy and AI 22, 100608 (2025).

Kiyohara, S. & Kumagai, Y. Bayesian optimization with gaussian processes assisted by deep learning for material designs. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 16, 5244–5251 (2025).

Wang, X., Hong, X., Pang, Q. & Jiang, B. Deep kernel learning-based bayesian optimization with adaptive kernel functions. IFAC-PapersOnLine 56, 5531–5535 (2023).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Williams, C. K. & Rasmussen, C. E.Gaussian processes for machine learning, vol. 2 (MIT press Cambridge, MA, 2006).

Wilson, A. G., Hu, Z., Salakhutdinov, R. & Xing, E. P. Deep kernel learning. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (2015).

Mockus, J. The bayesian approach to global optimization. In System Modeling and Optimization: Proceedings of the 10th IFIP Conference New York City, USA, August 31–September 4, 1981, 473–481 (Springer, 2005).

Balandat, M. et al. BoTorch: A Framework for Efficient Monte-Carlo Bayesian Optimization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems33 (2020).

Boitreaud, J., Mallet, V., Oliver, C. G. & Waldispühl, J. Optimol : Optimization of binding affinities in chemical space for drug discovery. bioRxiv (2020).

Nguyen, T. V. et al. Nano-material configuration design with deep surrogate langevin dynamics. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Roussel, R. et al. Bayesian optimization algorithms for accelerator physics. Phys. Rev.Accelerators Beams 27, 084801 (2024).

Shahriari, B., Swersky, K., Wang, Z., Adams, R. P. & De Freitas, N. Taking the human out of the loop: A review of bayesian optimization. Proc. IEEE 104, 148–175 (2015).

Sobol’, I. M. On the distribution of points in a cube and the approximate evaluation of integrals. Zh. Vychislitel’noi Matematiki i Matematicheskoi Fiz. 7,784–802 (1967).

Owen, A. B. Scrambling sobol’and niederreiter–xing points. J. Complex. 14, 466–489 (1998).

Williams, C. K. Prediction with gaussian processes: From linear regression to linear prediction and beyond. In Learning in graphical models, 599–621 (Springer, 1998).

MacKay, D. J. Gaussian processes-a replacement for supervised neural networks? Lecture notes for a tutorial at NIPS (1997).

Jones, D. R., Schonlau, M. & Welch, W. J. Efficient global optimization of expensive black-box functions. J. Glob. Optim. 13, 455–492 (1998).

Bull, A. D. Convergence rates of efficient global optimization algorithms. J. Machine Learning Res. 12, 2879−2904 (2011).

Srinivas, N., Krause, A., Kakade, S., Seeger, M.: Gaussian Process Optimization in the Bandit Setting: No Regret and Experimental Design, pp. 1015–1022. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10) (2010).

Srinivas, N., Krause, A., Kakade, S. M. & Seeger, M. W. Information-theoretic regret bounds for gaussian process optimization in the bandit setting. IEEE Trans. Inf. theory 58, 3250–3265 (2012).

Genton, M. G. Classes of kernels for machine learning: a statistics perspective. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2, 299–312 (2001).

Irshad, F., Karsch, S. & Döpp, A. Multi-objective and multi-fidelity bayesian optimization of laser-plasma acceleration. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013063 (2023).

Gratus, J., Seviour, R., Kinsler, P. & Jaroszynski, D. A. Temporal boundaries in electromagnetic materials. N. J. Phys. 23, 083032 (2021).

Arber et al. Contemporary particle-in-cell approach to laser-plasma modelling. Plasma Phys.Controlled Fusion 57, 113001 (2015).

Beckett, G. et al. ARCHER2 Service Description. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.14507040 (2024).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Gardner, J. R., Pleiss, G., Bindel, D. S., Weinberger, K. Q. & Wilson, A. G. Gpytorch: Blackbox matrix-matrix gaussian process inference with gpu acceleration. ArXiv abs/1809.11165 (2018).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. ArXiv abs/1912.01703 (2019).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback. Their thoughtful comments greatly helped in refining the structure and depth of arguments in this paper. D.A.J. and B.E. acknowledge support from the U.K. EPSRC (grant number EP/N028694/1) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 871124 Laserlab-Europe. Results were obtained using the ARCHIE-WeSt High Performance Computer (www.archie-west.ac.uk) based at the University of Strathclyde. This work also used the ARCHER2 UK National Supercomputing Service (https://www.archer2.ac.uk). The EPOCH code was partly funded by the grants EP/G054950/1, EP/G056803/1, EP/G055165/1, EP/ M022463/1 and EP/P02212X/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.A.J. conceived the study, S.I. and F.D. developed the D.K.B.O. algorithms and S.I. undertook all the simulations and optimisations. S.I., D.A.J., B.E. undertook the analysis of the physics models and the interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Christopher Arran and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ivanov, S., Ersfeld, B., Dong, F. et al. Design of transient plasma photonic structure mirrors for high-power lasers using deep kernel Bayesian optimisation. Commun Phys 9, 34 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-026-02505-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-026-02505-x