Abstract

Early diagnosis of colorectal cancer substantially improves survival. However, over half of cases are diagnosed late due to the demand for colonoscopy—the ‘gold standard’ for screening—exceeding capacity. Colonoscopy is limited by the outdated design of conventional endoscopes, which are associated with high complexity of use, cost and pain. Magnetic endoscopes are a promising alternative and overcome the drawbacks of pain and cost, but they struggle to reach the translational stage as magnetic manipulation is complex and unintuitive. In this work, we use machine vision to develop intelligent and autonomous control of a magnetic endoscope, enabling non-expert users to effectively perform magnetic colonoscopy in vivo. We combine the use of robotics, computer vision and advanced control to offer an intuitive and effective endoscopic system. Moreover, we define the characteristics required to achieve autonomy in robotic endoscopy. The paradigm described here can be adopted in a variety of applications where navigation in unstructured environments is required, such as catheters, pancreatic endoscopy, bronchoscopy and gastroscopy. This work brings alternative endoscopic technologies closer to the translational stage, increasing the availability of early-stage cancer treatments.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information files.

Code availability

All the algorithms and mathematical methods used in this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information. The computer code is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Joseph, D. A. et al. Colorectal cancer screening: estimated future colonoscopy need and current volume and capacity. Cancer 122, 2479–2486 (2016).

Comas, M., Mendivil, J., Andreu, M., Hernandez, C. & Castells, X. Long-term prediction of the demand of colonoscopies generated by a population-based colorectal cancer screening program. PLoS ONE 11, e0164666 (2016).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424 (2018).

Chen, C., Hoffmeister, M. & Brenner, H. The toll of not screening for colorectal cancer. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 1–3 (2017).

Chan, A. O. et al. Colonoscopy demand and practice in a regional hospital over 9 years in Hong Kong: resource implication for cancer screening. Digestion 73, 84–88 (2006).

Williams, C. & Teague, R. Colonoscopy. Gut 14, 990–1003 (1973).

Kassim, I. et al. Locomotion techniques for robotic colonoscopy. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 25, 49–56 (2006).

Larsen, S., Kalloo, A. & Hutfless, S. The hidden cost of colonoscopy including cost of reprocessing and infection rate: the implications for disposable colonoscopes. Gut 69, 197–200 (2020).

Spier, B. J. et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest. Endosc. 71, 319–324 (2010).

Lee, S.-H., Park, Y.-K., Lee, D.-J. & Kim, K.-M. Colonoscopy procedural skills and training for new beginners. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 16984–16995 (2014).

Reilink, R., Stramigioli, S. & Misra, S. Image-based flexible endoscope steering. In 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems 2339–2344 (IEEE, 2010).

Kuperij, N. et al. Design of a user interface for intuitive colonoscope control. In 2011 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems 937–942 (IEEE, 2011).

Schoofs, N., Deviere, J. & Van Gossum, A. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy compared with colonoscopy for colorectal tumor diagnosis: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy 38, 971–977 (2006).

Glass, P., Cheung, E. & Sitti, M. A legged anchoring mechanism for capsule endoscopes using micropatterned adhesives. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 55, 2759–2767 (2008).

Kim, H. M. et al. Active locomotion of a paddling-based capsule endoscope in an in vitro and in vivo experiment (with videos). Gastrointest. Endosc. 72, 381–387 (2010).

Shamsudhin, N. et al. Magnetically guided capsule endoscopy. Med. Phys. 44, e91–e111 (2017).

Valdastri, P. et al. Magnetic air capsule robotic system: proof of concept of a novel approach for painless colonoscopy. Surg. Endosc. 26, 1238–1246 (2012).

Mahoney, A. W. & Abbott, J. J. Generating rotating magnetic fields with a single permanent magnet for propulsion of untethered magnetic devices in a lumen. IEEE Trans. Robot. 30, 411–420 (2013).

Abbott, J. J., Diller, E. & Petruska, A. J. Magnetic methods in robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst 3, 57–90 (2015).

Xu, T., Zhang, J., Salehizadeh, M., Onaizah, O. & Diller, E. Millimeter-scale flexible robots with programmable three-dimensional magnetization and motions. Sci. Robot. 4, eaav4494 (2019).

Norton, J. C. et al. Intelligent magnetic manipulation for gastrointestinal ultrasound.Sci. Robot. 4, eaav7725 (2019).

Sikorski, J., Heunis, C. M., Franco, F. & Misra, S. The ARMM system: an optimized mobile electromagnetic coil for non-linear actuation of flexible surgical instruments. IEEE Trans. Magn. 55, 1–9 (2019).

Ryan, P. & Diller, E. Magnetic actuation for full dexterity microrobotic control using rotating permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Robot. 33, 1398–1409 (2017).

Arezzo, A. et al. Experimental assessment of a novel robotically-driven endoscopic capsule compared to traditional colonoscopy. Dig. Liver Dis. 45, 657–662 (2013).

Son, D., Gilbert, H. & Sitti, M. Magnetically actuated soft capsule endoscope for fine-needle biopsy. Soft Robot 7, 10–21 (2019).

Sikorski, J., Denasi, A., Bucchi, G., Scheggi, S. & Misra, S. Vision-based 3-D control of magnetically actuated catheter using BigMag—an array of mobile electromagnetic coils. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 24, 505–516 (2019).

Edelmann, J., Petruska, A. J. & Nelson, B. J. Estimation-based control of a magnetic endoscope without device localization. J. Med. Robot. Res. 3, 1850002 (2018).

Taddese, A. Z., Slawinski, P. R., Obstein, K. L. & Valdastri, P. Nonholonomic closed-loop velocity control of a soft-tethered magnetic capsule endoscope. In 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 1139–1144 (IEEE, 2016).

Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to On-road Motor Vehicle Automated Driving Systems (Society of Automotive Engineers, 2014).

Yang, G.-Z. et al. Medical robotics-regulatory, ethical and legal considerations for increasing levels of autonomy. Sci. Robot. 2, eaam8638 (2017).

Haidegger, T. Autonomy for surgical robots: concepts and paradigms. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics 1, 65–76 (2019).

Jamjoom, A. A., Jamjoom, A. M. & Marcus, H. J. Exploring public opinion about liability and responsibility in surgical robotics. Nat. Mach. Intell 2, 194–196 (2020).

Slawinski, P. R., Taddese, A. Z., Musto, K. B., Obstein, K. L. & Valdastri, P. Autonomous retroflexion of a magnetic flexible endoscope. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2, 1352–1359 (2017).

Taddese, A. Z. et al. Enhanced real-time pose estimation for closed-loop robotic manipulation of magnetically actuated capsule endoscopes. Int. J. Robot. Res. 37, 890–911 (2018).

Park, H.-J. et al. Predictive factors affecting cecal intubation failure in colonoscopy trainees. BMC Med. Educ. 13, 5 (2013).

Plooy, A. M. et al. The efficacy of training insertion skill on a physical model colonoscopy simulator. Endosc. Int. Open 4, E1252–E1260 (2016).

Hart, S. G. & Staveland, L. E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): results of empirical and theoretical research. Adv. Psychol 52, 139–183 (1988).

Turan, M., Shabbir, J., Araujo, H., Konukoglu, E. & Sitti, M. A deep learning based fusion of RGB camera information and magnetic localization information for endoscopic capsule robots. Int. J. Intell. Robot. Appl. 1, 442–450 (2017).

Son, D., Dong, X. & Sitti, M. A simultaneous calibration method for magnetic robot localization and actuation systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. 35, 343–352 (2018).

Diller, E., Giltinan, J., Lum, G. Z., Ye, Z. & Sitti, M. Six-degree-of-freedom magnetic actuation for wireless microrobotics. Int. J. Robot. Res. 35, 114–128 (2016).

Popek, K. M., Schmid, T. & Abbott, J. J. Six-degree-of-freedom localization of an untethered magnetic capsule using a single rotating magnetic dipole. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2, 305–312 (2016).

Slawinski, P. R., Obstein, K. L. & Valdastri, P. Emerging issues and future developments in capsule endoscopy. Tech. Gastrointest. Endosc. 17, 40–46 (2015).

Turan, M. et al. Endo-VMFuseNet: a deep visual-magnetic sensor fusion approach for endoscopic capsule robots. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 1–7 (IEEE, 2018).

Ciuti, G. et al. Robotic versus manual control in magnetic steering of an endoscopic capsule. Endoscopy 42, 148–152 (2010).

Pittiglio, G. et al. Magnetic levitation for soft-tethered capsule colonoscopy actuated with a single permanent magnet: a dynamic control approach. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 4, 1224–1231 (2019).

Scaglioni, B. et al. Explicit model predictive control of a magnetic flexible endoscope. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 4, 716–723 (2019).

Carpi, F., Kastelein, N., Talcott, M. & Pappone, C. Magnetically controllable gastrointestinal steering of video capsules. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 58, 231–234 (2010).

Graetzel, C. F., Sheehy, A. & Noonan, D. P. Robotic bronchoscopy drive mode of the Auris Monarch platform. In 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 3895–3901 (IEEE, 2019).

Mamunes, A. et al. Su1351 The magnetic flexible endoscope (MFE): a learning curve analysis. Gastroenterology 158, S561 (2020).

Lisi, G., Campanelli, M., Spoletini, D. & Carlini, M. The possible impact of COVID-19 on colorectal surgery in Italy. Colorectal Dis. 22, 641–642 (2020).

Flacco, F., De Luca, A. & Khatib, O. Control of redundant robots under hard joint constraints: saturation in the null space. IEEE Trans. Robot. 31, 637–654 (2015).

Chen, Z. Bayesian filtering: from Kalman filters to particle filters, and beyond. Statistics 182, 1–69 (2003).

Mahoney, A. W. & Abbott, J. J. Five-degree-of-freedom manipulation of an untethered magnetic device in fluid using a single permanent magnet with application in stomach capsule endoscopy. Int. J. Robot. Res. 35, 129–147 (2016).

Wang, D., Xie, X., Li, G., Yin, Z. & Wang, Z. A lumen detection-based intestinal direction vector acquisition method for wireless endoscopy systems. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 807–819 (2014).

Prendergast, J. M., Formosa, G. A., Heckman, C. R. & Rentschler, M. E. In 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 783–790 (IEEE, 2018).

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this Article was supported by the Royal Society, Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Early Detection and Diagnosis Research Committee (award no. 27744), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging, Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; award no. R01EB018992), by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 818045) and the Italian Ministry of Health funding programme ‘Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata 2013—Giovani Ricercatori’ project no. PE-2013-02359172. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this Article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Royal Society, CRUK, NIH, ERC or the Italian Ministry of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.M. and B.S. worked together throughout the project and co-authored the paper. In the following, an asterisk indicates (co-)leadership on a task. J.W.M.*, B.S.*, P.V.* and A.A. worked on conceptualization. J.W.M. worked on data curation and formal analysis. P.V.*, K.L.O.*, A.A.* and V.S.* worked on funding acquisition. B.S.*, J.W.M.* and J.C.N.* worked on investigation. B.S.*, J.W.M.*, J.C.N.*, K.L.O., A.A. and V.S. worked on methodology. B.S.* and P.V.* worked on project administration. P.V.* and J.C.N.* worked on resources. J.W.M.* and B.S.* worked on software. P.V. worked on supervision. B.S.*, J.W.M.*, P.V.* and J.C.N.* worked on validation. J.W.M.* and B.S.* worked on visualization. J.W.M.* and B.S.* worked on writing the initial draft. B.S.*, J.W.M.*, P.V., J.C.N., K.L.O., A.A. and V.S. worked on writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

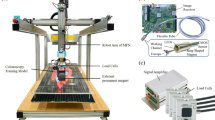

Extended Data Fig. 1 Validation of the magnetic manipulation algorithm.

The first experiment sort to verify that the closed-loop controller could manipulate the EPM in such a way that the magnetic torque imparted on the MFE would accurately and precisely control the direction of the MFE camera frame. The experiment was carried out on a testing rig consisting of a straight tract of latex colon model (M40, Kyoto Kagaku Co., Ltd) with a LED reference point mounted at one end of the tract. The MFE was then positioned so that its camera could observe the LED (10cm separation distance). A simple image-thresholding algorithm was then used to detect the LED in the MFE image. The robot closed-loop controller, based on a proportional-derivative control approach, thoroughly described in Intelligent Control and Autonomous Navigation, autonomously steered the MFE to trace two predefined motions in the image plane, arranged in either a sinusoidal or circular trajectory with the tracked LED point used as a positional reference. Upon the LED aligning to the first pixel point of the trajectory, the target was updated to the next point along the trajectory and repeated until complete (Supplementary Video 2). Each trajectory was repeated 5 times with the circular path having an average pixel position error of 6.54 ± 0.94, and the sinusoidal path having an average pixel position error of 7.73 ± 1.45. Given a pixel-to-millimetre-conversion described in Supplementary Fig. 2, this experiment shows that the orientation controller can steer the MFE image plane towards a target, with a positional accuracy of about 5mm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Example of lumen detection algorithm.

where (a) is the original MFE image and (b) is the segmented centre of the colon and (c) is the centre mass point of the lumen (xl,yl) which will be steered to the centre of image (xC,yC) and (d) represents the change in linear velocity of the MFE, given the distance between the estimated lumen (xl,yl) and centre of image (xc,yc).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Feature detector for autonomous navigation.

The action of the autonomous controller is dependent on the absence, or presence of a lumen. When no clear lumen is present in the MFE image (Extended data Fig. 3–a), the FAST feature detector will return a low number of features, with a feature defined as a discernible edge in the image. Features are shown here as green circles. When a clear lumen is present in the MFE image (Extended data Fig. 3–b), the FAST feature detector will instead return a high number of features.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5, algorithms 1–3, equations (1) and (2), Videos 1–3 and Datasets 1 and 2.

Supplementary Video 1

Concept overview.

Supplementary Video 2

Closed-loop controller validation.

Supplementary Video 3

Results.

Supplementary Data 1

Data—benchtop.

Supplementary Data 2

Data—in vivo.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, J.W., Scaglioni, B., Norton, J.C. et al. Enabling the future of colonoscopy with intelligent and autonomous magnetic manipulation. Nat Mach Intell 2, 595–606 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-00231-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-00231-9

This article is cited by

-

Superelastic Tellurium Thermoelectric Coatings for Advanced Trimodal Microsensing

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Hard-magnetic soft continuum robots: Modeling, design and applications

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2026)

-

A soft robotic “Add-on” for colonoscopy: increasing safety and comfort through force monitoring

npj Robotics (2025)

-

Innovative design and comprehensive ergonomic assessment of an auxiliary colonoscopy handle device

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

An electromagnetic robot for navigating medical devices

Nature Reviews Bioengineering (2024)