Abstract

Cancers are commonly characterized by a complex pathology encompassing genetic, microscopic and macroscopic features, which can be probed individually using imaging and omics technologies. Integrating these data to obtain a full understanding of pathology remains challenging. We introduce a method called deep latent variable path modelling, which combines the representational power of deep learning with the capacity of path modelling to identify relationships between interacting elements in a complex system. To evaluate the capabilities of deep latent variable path modelling, we initially trained a model to map dependencies between single-nucleotide variant, methylation profiles, microRNA sequencing, RNA sequencing and histological data using breast cancer data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. This method exhibited superior performance in mapping associations between data types compared with classical path modelling. We additionally performed successful applications of the model to stratify single-cell data, identify synthetic lethal interactions using CRISPR–Cas9 screens derived from cell lines and detect histologic–transcriptional associations using spatial transcriptomic data. Results from each of these data types can then be understood with reference to the same holistic model of illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Many common illnesses such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases and neurological disorders result from complex pathologies that possess genetic, microscopic and macroscopic components1,2,3,4. Over recent decades, the invention and widespread use of diverse omics and imaging technologies has provided important insights into the mechanisms that underpin these diseases5. However, analysed individually, these technologies may illuminate only a single aspect of pathology. A comprehensive understanding of complex disease necessitates the integration of these disparate data types6. There is a pressing need for new methods designed for this purpose.

Cancers are characterized by intricate pathological mechanisms. Cellular functions are dictated via multiple layers of biological information and processing. In cancer, this information is corrupted, and normal processes are subverted, giving cancer cells the ability to survive, proliferate and metastasize1. Recent studies have revealed a diversity of somatic mutation classes, widespread epigenetic changes and substantial alterations in gene expression, all of which exhibit high heterogeneity across tumours, even within the same tissue7. Despite its molecular genesis, cancer is still primarily diagnosed and understood clinically through histological imaging; this process involves extracting, sectioning, staining and imaging tumour biopsies to identify aberrations in tissue microstructure linked to specific clinical phenotypes8. Efficient, integrative approaches that systematically combine multiomic and imaging modalities could lead to deeper insights into cancer biology.

Deep learning methods excel at processing unstructured data, such as imaging, by identifying complex patterns without explicit programming9. In recent years, numerous hypothesis-driven studies have been conducted with a focus on predicting the presence of genetic characteristics of cancer, such as driver mutations and clinical status, using histological data10,11. Deep learning methods have also proved highly effective in modelling the complex interdependencies between genes in multiomic datasets12,13. Other research efforts have aimed to integrate histological and genetic data to predict clinically important outcomes, including patient survival times14,15,16,17,18 and drug response profiles19. Despite these advancements, exploratory research that seeks to map the complex interactions between various layers of genetic information and histological data is still in its infancy, presenting a largely uncharted frontier in oncology. All-encompassing methods are required to comprehensively map the causal and statistical dependencies between different data types relevant in cancer biology.

Path modelling (also called structural equation modelling) is a powerful and widely used class of techniques used primarily in epidemiology20, social sciences21 and econometrics22. Intuitively, a path model can be thought of as a map, specifying connections between different data types. Path-modelling methods are ideally suited for multimodal data integration in biology as they allow the simultaneous estimation of multiple relationships, enabling the detailed examination of both direct and indirect effects between different data modalities. Furthermore, the visual representation of results in path diagrams aids in intuitively communicating complex inter-relations. Path-modelling methods are self-supervised in the sense that they are not trained for a specific task, but rather to learn the underlying structure of a multimodal dataset. Once the model is trained, it can be applied to a variety of downstream tasks, such as prediction, classification and even causal inference23,24. Despite these strengths, path-modelling methods currently struggle with representing and capturing the complexity of unstructured data types, such as images. Consequently, they share similar constraints with classical techniques used for classification and regression, which are inadequate for the evaluation of unstructured data, and the handling of complex, nonlinear patterns frequently encountered in biological research12,13.

In this study, we introduce a deep-learning-based method for path modelling called deep latent variable path modelling (DLVPM). This method combines the representational power of deep learning, with the ability of path modelling to map complex dependencies between data types. In the cancer context, this allows us to model the genetic and epigenetic interactions with gene expression, which, in turn, result in the microscopically visible aberrations in tissue structure that are a characteristic of cancer. A crucial strength of the method is its modular nature, which allows submodels trained for each individual modality to be characterized further on new datasets.

We trained a full DLVPM path model on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) breast cancer dataset25, one of the most comprehensive and well-annotated datasets combining imaging and multiomics data modalities. However, before initiating full path modelling, we pretrained a histological model, again using DLVPM, which was benchmarked against other state-of-the-art methods and histological models. This model served as a foundation for the integration of histological data into the full path-modelling framework. The DLVPM method proved superior to classical path modelling in identifying inter-relations among genetic, epigenetic and histological data. In secondary analyses, we used this model to identify hundreds of genetic loci showing an individually significant association with histology. The molecular subcomponent of the full DLVPM model, initially trained on the TCGA patient data, was then successfully replicated on independent patient and cell-line data, and used to explore the differential sensitivity of breast cancer cell lines to CRISPR–Cas9 knockouts, revealing significant associations between the model and many gene dependencies. Spatial transcriptomic data were then used to further characterize these genes in the context of the DLVPM model. This approach offers a holistic view of cancer, illustrating the power of DLVPM as a singular, comprehensive method for multilayered data integration.

Results

DLVPM

DLVPM is a framework that unites the flexibility of deep neural networks9 with the interpretability and structure of path modelling23,26,27. By leveraging powerful representations learned through neural architectures, DLVPM extends classical path modelling beyond linear relationships and latent variables to rich, nonlinear embeddings.

Path-modelling/structural-equation-modelling methods are a family of procedures used for mapping dependencies between different data types23,26,27. These methods are able to model arbitrarily many data types simultaneously, providing a holistic view of a system of interacting elements. Path-modelling analyses begin with the user specifying the path model itself. This model encodes hypotheses about the relationships between data types included in an analysis. These models are usually represented visually as a network graph (Fig. 1a), and mathematically as an adjacency matrix.

a, Constituent parts of a DLVPM model. The path model defines the data types that are connected to one another. The measurement models for each data type are used to construct the DLVs that are optimized to be strongly correlated between data types. The overall model combines both path model and measurement models. This image represents DLVPM in a situation where four data types are available. b, Use of DLVPM in a Siamese/twin network configuration. Here augmented versions of the same input are fed to a network, and the network is trained to learn DLVs that are invariant to these augmentations.

The adjacency matrix is a square matrix, where elements cij represent connections between data types i and j and K is the total number of data types under analysis. Each element in the matrix indicates the presence (value of one) or absence (zero value) of a direct influence from one data type to another.

In classical path modelling, techniques like partial least squares path modelling (PLS-PM) are used to derive latent variables that exhibit optimal correlation among datasets linked by the path model. However, such techniques are limited to modelling linear effects23.

Deep neural networks excel in their ability to model nonlinear effects, and to process structured and unstructured data. Most neural networks can be written in the general form \(\bar{Y}(X,U)\), where \(\bar{Y}\) is the network output, X is some data input and U is the set of network parameters (including weights, biases and other network parameters).

In DLVPM, we define a collection of submodels, one for each data type, indexed here by the subscript i:

where \({\bar{Y}}_{i}\) is the network output, a set of deep latent variables (DLVs), Ui is the set of parameters up to the penultimate network layer and Wi corresponds to the network weights on the last layer of the neural network. This weight is displayed separately as it represents a linear projection and is critical to the way DLVPM is trained. These submodels are called measurement models23.

The DLVPM algorithm is then trained to construct DLVs from each measurement model, which are optimized to be maximally associated with DLVs from other measurement models, connected by the path model. These optimization criteria can be written as

where cij represents the association matrix input from data type i to data type j, and tr denotes the matrix trace. DLVs derived from each data type are constrained to be orthogonal to one another:

where I is the identity matrix. These DLVs are then optimized to be strongly correlated across data types connected by the path model, while maintaining orthogonality within each data type, thereby capturing the essence of each data type’s contribution to the system and minimizing information redundancy within the model. Following model training, the DLVPM algorithm results in a set of orthogonal path models representing associations between DLVs constructed from each data type. In deep learning parlance, these DLVs can be considered to represent a joint embedding.

DLVPM’s training process is both iterative and end to end, enabling the model to learn directly from the raw data to the final output without the requirement for manual feature engineering.

The DLVPM method is extremely versatile. The measurement model formula, \({\bar{Y}}_{i}({X}_{i},\,{U}_{i},{W}_{i})\), hides a high level of generality and complexity. In practice, almost any kind of neural network can be used here. This means that the method can be used to create embeddings shared by feed-forward networks, convolutional networks and transformers and so on, where architectural choices will depend on the data under analysis.

We introduce two different formulations of DLVPM, using different orthogonalization procedures. During training, the orthogonalization constraint is achieved via whitening or iterative orthogonalization. Whitening is a widely used approach in deep learning. Iterative orthogonalization has the advantage that it prioritizes DLVs by their importance—a feature of considerable importance in the biological application presented here.

DLVPM-Twins

Although DLVPM is primarily designed to uncover associations between multiple data types, it also excels at discovering useful representations of a single data type. In this context, DLVPM mirrors the objectives of confirmatory factor analysis28 within classical path modelling—each serves to distill complex data into simpler, interpretable structures. However, although confirmatory factor analysis confines itself to linear relationships, DLVPM extends this capacity into the nonlinear domain by enabling the use of deep neural network architectures. When used in this manner, DLVPM falls into the class of methods called Siamese or twin networks29. This class of methods has become popular across a wide range of fields in recent years30,31. Using this type of method, two augmented (distorted) versions of the same input are passed to a network. The model is then trained to learn features invariant to the applied augmentations, thereby promoting the development of robust and generalizable features (Fig. 1b). The optimization criteria for this method can be written as

subject to the constraint

where \({\bar{Y}}_{A}\) and \({\bar{Y}}_{B}\) are outputs of the neural network with weights U and W. Here XA and XB are different augmentations of the same input X. As was the case for the full DLVPM path-modelling procedure, both whitening and iterative orthogonalization schemes were used to impose orthogonality.

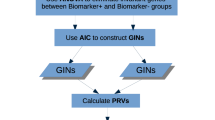

A full and robust mathematical formulation of DLVPM is given in the Methods. The algorithm is illustrated further in Extended Data Fig. 1.

Confounding effects

Previous research has highlighted how factors such as the acquisition site can undermine the replicability and generalizability of studies on molecular and histological data32. To address these issues, we implemented an approach for controlling the effect of confounders within a custom neural network layer. This layer uses the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse of a matrix of nuisance covariates to remove the effect of confounding variables. We used this method to remove confounding effects of site in all the DLVPM analyses. In particular, this versatile layer represents a separate contribution from the main DLVPM method, and can be used in any neural network model. The mechanics of this approach are thoroughly detailed in the Methods and are illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 2.

Benchmarking DLVPM-Twins

In the past couple of years, a number of large-scale ‘foundation models’ have been trained on histological images from cancer33,34. Foundation models are trained in a self-supervised manner to learn meaningful representations of the histological input data, which can then be leveraged for various applications. Although DLVPM is primarily designed to learn dependencies between different data types, DLVPM-Twins can be used to pretrain a histological model, which can be used in downstream tasks. DLVPM-Twins is trained by passing a network augmented versions of the same input (Fig. 2a). In the present context, this means flipping, rotating and altering the colour of images passed to the network. The model is then trained to learn orthogonal DLVs that are invariant to these distortions. This encourages the network to learn meaningful representations of data.

a, Illustration of DLVPM in a Siamese/twin network configuration. b, Plots comparing the performance of DLVPM-Twins against VicReg, Barlow twins and several pretrained foundation models (n = 152). The error bars represent the mean-centred 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. c, Illustration of the DLVPM method showing a graph representation of the path model, and the associated adjacency matrix. d, Comparison of the mean Pearson’s correlation across dimensions and data modalities for DLVPM and PLS-PM (n = 152). The error bars represent the mean-centred 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. e, Plots show the mean Pearson’s correlation of each DLV, with DLVs from the data types connected by the path model. The error bars represent the mean-centred 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (n = 152). f, Association matrices for all the five DLVs. The entries in the top triangular part of the matrix indicate the Pearson’s correlation values between the different data types. The entries in the bottom part of the matrix are significance values for these correlations, obtained using permutation testing (n = 152). g, Path model linking the omics and imaging data types included in this analysis. This graph represents the first orthogonal mode of variation between DLVs. The edges connecting the network nodes are labelled with Pearson’s pairwise correlation coefficient (n = 152). h, Results of mediation analyses carried out using the first DLV. The numbers on the network graph are beta values. The significance of the mediated effect is shown on the right of the graph (n = 152). i, Results of additional analyses to localize effects to particular genetic loci. The plot shows the Pearson’s correlation values between the genetic loci and DLVs connected to the data view under analysis by the path model. The plots on the left show the ten most positively and negatively associated genetic loci for each data type. The error bars represent the mean-centred 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. The bar plots show the Pearson’s correlation values for all the loci under analysis, along with the family-wise error-corrected (FWER) significance threshold (n = 152). Panels a and c created with BioRender.com.

The performance of self-supervised methods/foundation models is typically compared on outcome-driven tasks. We compared the performance of a model trained using DLVPM-Twins with models trained using VicReg and Barlow twins, two commonly used Siamese/twin network approaches. We also compared performance with several recently published histological foundation models33,34,35. We benchmarked the performance of different models/methods on several classification tasks: prediction of histological and molecular status, and the presence/absence of TP53 mutations. This was achieved by training a single-layer classification head on top of embeddings generated by these different procedures. We used 80% of the TCGA breast cancer dataset for training, with the remaining 20% used for testing (n = 606 training and n = 152 testing; Fig. 2a). Population characteristics of this sample can be found in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. This train/test split was also used for the full DLVPM path-modelling analysis described in the next section. We trained Siamese models based on the EfficientNetB0 convolutional architecture using DLVPM-Twins, VicReg and Barlow twins (Methods).

We found that the performance of DLVPM-Twins equalled both large-scale foundation models and Barlow twins and VicReg procedures (Fig. 2b). Our method has the advantage over VicReg and Barlow twins methods in that its loss does not require any hyperparameters other than the size of the final embedding. Fewer hyperparameters simplify the training process and increase the model robustness by reducing the need for extensive tuning. Among the two DLVPM variants, the version using iterative orthogonalization has the major advantage that it ranks the DLVs according to the strength of their associations across data types, in a manner akin to the ranking of principal components on the basis of the variance they account for within a dataset. Barlow twins is limited to learning a representation of a single data type; VicReg can learn representations of two data types but it is unclear how the method can be generalized further than this. By contrast, DLVPM can be used to integrate data from arbitrarily many data types.

Our model matches the performance of UNI, Vichrow and Conch, notable foundation models in histology, while maintaining a substantially lower parameter count. Both UNI and Vichrow are trained using the DinoV2 algorithm, which requires the use of a vision transformer. By contrast, our DLVPM-Twins algorithm is more versatile, supporting a variety of neural network models beyond vision transformers. For example, we have effectively trained an EfficientNetB0, a convolutional neural network, using this method. This flexibility allows DLVPM-Twins to adapt to different network architectures, providing a strong advantage for applications across a diverse range of datasets and computational constraints.

Full DLVPM

Next, we trained DLVPM for the purposes of full path modelling. We applied DLVPM to data from 758 breast cancer samples from TCGA. Our initial goal was to uncover relationships across five data types: histological images, single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), methylation profiles, microRNA (miRNA) sequencing (miRNA-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) expression data. We positioned the transcriptomic data at the centre of the path-modelling analysis, recognizing its pivotal role in mediating the effects of genomic and epigenomic changes on histological tissues through gene expression modulation. Using this path model, all other data types are linked to one another indirectly through the RNA-seq data (Fig. 2c). Training and testing were carried out using the same 80%–20% train–test split as for the DLVPM-Twins analysis.

We must also specify the measurement models for each data type; these models define the manner in which data are processed and connected. For the histology data, we specified a neural network that aggregates effects arising at different magnifications. Here it takes DLVPM-Twins models trained at ×5, ×10 and ×20 magnifications, each utilizing the EfficientNetB0 convolutional architecture36. For the genetic data, we used a residual network with an attentional mechanism. This allows the neural network to aggregate the linear effects from individual genes, with interaction effects between genes. The full neural network encompassing the path model and individual measurement models is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3.

Following model training, we compared the performance of DLVPM with PLS-PM23. PLS-PM has an identical objective to DLVPM, but is only able to model linear effects. In this comparison, both iterative orthogonalization and whitening versions of DLVPM demonstrated greatly superior performance compared with PLS-PM (Fig. 2d). Comparing performance with other deep learning methods for multimodal data integration is not feasible in this manner, as fundamentally different purposes are encoded by distinct loss functions unique to each method. As previously noted, the DLVPM variant utilizing iterative orthogonalization has the advantage that it ranks DLVs by their importance. For this reason, we used the results from this approach in all subsequent analyses. This ranking of DLVs by their mean association is shown in Fig. 2e for the model as a whole and for each data type individually.

Next, we evaluated the specific associations the method uncovers between data types. These associations and their permutation family-wise error-corrected significance levels are shown in Fig. 2f. This analysis uncovers multiple orthogonal paths that connect molecular and histological data. A network graph illustrating the DLVPM path model for the first set of DLVs is illustrated in Fig. 2g.

To ensure the robustness of the out-of-sample results, we also carried out a fivefold cross-validation analysis, in place of the single train–test split used here. Correlations were of a similar magnitude to the main results, confirming robustness (Supplementary Fig. 1). We further replicated our main results on 105 independent patient samples from the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) project37,38. The CPTAC data allowed us to validate the robustness of DLVPM across datasets, demonstrating similar patterns of associations between different data modalities (Extended Data Fig. 4).

A major strength of DLVPM is its ability to uncover and analyse indirect effects, such as mediation relationships among variables, opening up the possibility of investigating the intricate dynamics that define complex systems. We examined how RNA-seq DLVs mediate the interaction between various genetic and epigenetic variables (specifically methylation, miRNA-seq and SNVs, which are treated as independent variables) and histological outcomes, which are treated as dependent variables. Path diagrams (Fig. 2h) visually depict these mediation processes, highlighting both direct effects and those mediated via the RNA-seq DLV. These analyses highlight the crucial role of gene expression in linking genetic and epigenetic changes to cellular and tissue-level phenotypes, offering insights into the complex interactions that drive histological changes (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5).

Consistent with DLVPM’s path model, which links all data types through the RNA-seq data, we observed that all DLVs—even those originating from the histology data—demonstrated a stronger association with established clinical molecular subtypes than with histological types. For instance, the first DLV distinctly stratified basal and luminal molecular subtypes across all data modalities (Extended Data Fig. 6a).

We used Cox proportional hazards regression to predict the progression-free interval from all the DLVs for both DLVPM-Iterative (concordance index (CI) = 0.65, P = 0.26, n = 152) and DLVPM-Whiten (CI = 0.64, P = 0.27, n = 152). Neither results were significant. However, the utility of TCGA for survival analysis is limited by its short follow-up period (mean follow-up, 3.4 years), which constrains the study of long-term outcomes. Additionally, the analysis is underpowered as full generality requires that we only use the test set (152 patient samples) for outcome prediction. To overcome these limitations, we recalculated the SNV and RNA-seq DLVs using data from the METABRIC study (Methods), which features a much longer follow-up; the longer follow-up period (mean follow-up, 9.29 years) in METABRIC confirmed that both DLVPM-Iterative (CI = 0.61, P = 1.4 × 10−14, n = 1,980) and DLVPM-Whiten (CI = 0.61, P = 5.4 × 10−14, n = 1,980) are strongly predictive of clinical outcomes (Extended Data Fig. 6b). We benchmarked the performance of DLVPM against other widely used methods for multimodal data integration, including PLS-PM23, MOFA+39,40 and a multimodal autoencoder41 (Methods). DLVPM demonstrated superior predictive performance to PLS-PM and the multimodal autoencoder, and similar predictive capabilities to MOFA+ (Supplementary Table 3).

DLVPM operates fundamentally as a multivariate approach, designed to uncover factors exhibiting high correlation across diverse data types, including genetic and imaging datasets. The multiomic DLVs constructed by the model represent complex polygenic factors. Owing to its multivariate nature, the method initially precludes the direct attribution of significance to specific genetic loci within the model. To bridge this gap, we ran additional analyses to isolate genetic/epigenetic loci that demonstrate significant correlations individually with DLVs (Methods). Each DLV produces a stratification of imaging/multiomic subtypes, with loci exhibiting either positive or negative associations. Hundreds of loci made individually significant contributions to the DLVPM model (Fig. 2i, Extended Data Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 4). Permutation testing using the distribution of the maximal statistic was used to control for multiple comparisons and provide strong control over the family-wise error rate.

The first DLV shows the strongest associative mode linking the omics and imaging data, and effects on histology are mediated via gene expression, quantified by RNA-seq. This prompted us to focus our initial interpretation of individually significant loci on RNA-seq data from DLV 1. First, we investigate negatively associated loci: this path model stratifies genes important in luminal–basal transcriptional differentiation program. ESR1, whose protein defines the luminal subtype, is used for the clinical diagnosis of breast cancer, and is a target in hormone therapy42. Furthermore, GATA3 encodes a transcription factor that regulates luminal cell differentiation and exhibits a shift from a tumour-suppressing role to a tumour-promoting role in breast cancer via the deregulation of THSD4 (ref. 43), which also shows a strong negative association. PGR, which encodes the progesterone receptor and is crucial for prognosticating hormone treatment outcomes in breast cancer, is also significant here and is closely linked to luminal breast cancer44. By contrast, genes showing a strong positive association with DLV 1 have been primarily linked to the basal breast cancer subtype. STMN1 encodes a protein that has been implicated in cell cycle progression and mitosis and has been investigated as a therapeutic target in breast cancer45. YBX1 encodes a protein strongly implicated in breast cancer, and is particularly noted for its role in cell migration and invasion46, as well as drug resistance47. TPX2 overexpression has also been linked to more aggressive forms of breast cancer48. MYBL2 encodes a protein that has been shown to drive cell cycle progression in breast cancer49. A luminal–basal stratification on the first DLV was supported by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) carried out between DLVs and gene expression scores (Methods); other DLVs were associated with different cancer-related processes (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We again benchmarked the performance of DLVPM against other widely used methods for multimodal data integration (Methods), in the task of identifying individually significant genetic loci. We found that DLVPM outperformed these methods in this task, with DLVPM identifying the most genetic loci associated with the multimodal data integration model (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

Characterization of histological data

A number of important previous studies have leveraged histological data to predict clinical molecular status, detect the presence or absence of known oncogenic mutations, and delineate bulk transcriptomic profiles of tumours using deep neural networks11,50. Although these studies are hugely important, they largely operate within the confines of pre-existing hypotheses. The DLVPM methodology stands out for its capacity to unearth previously unrecognized relationships across diverse data modalities.

We ran further analyses focused on pinpointing multiomic loci that show individually significant correlations with histological DLVs, which represent an outcome phenotype. Our investigations not only corroborated existing knowledge by identifying histological–genetic associations with well-documented oncogenes such as TP53 but also uncovered significant links between histological features and hundreds of previously uncharted multiomic loci (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8a and Supplementary Table 5).

a, Results of additional analyses to localize effects to identify omics loci showing an individually significant association with the histological data. The plot shows Pearson’s correlation values between genetic loci, and the first histological DLV. The plots on the left show the ten most positively and negatively associated genetic loci for each data type (n = 152). The error bars represent the mean-centred 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. The bar plots show Pearson’s correlation values for all the loci under analysis, along with the family-wise error-corrected significance threshold. Owing to space limitations, we only show the analyses for the first DLV here. b, Normalized heat maps for a tumour, on the first DLV, at ×5, ×10 and ×20 magnifications.

The first histological DLV exhibited by far the largest number of individually significant associations with multiomic loci (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8a and Supplementary Table 5). Many of the genes making the strongest individual contribution to the overall model were also amongst those showing the most pronounced correlations with the histology data: PGR showed a strong negative association with DLV 1; the expression of this gene has been reported as exhibiting pronounced inverse correlations with histological grade, mitotic rate and nuclear pleomorphism in hypothesis-driven studies involving expert pathological assessment51. The ABAT gene, which has been previously linked to ER-positive breast cancers52, shows the strongest negative association with DLV 1. Genes showing a strong positive association with histology are primarily associated with the more aggressive basal type. The products of the genes TPX2, ANP32B, PFKP, CHI3L1, S1009A, FOXM1, STMN1 and MYBL2 are crucially involved in cellular proliferation45,49,53,54,55,56,57,58. This is particularly noteworthy in this context where increased cellular proliferation will result in visible changes in tumour grade and mitotic rate.

We benchmarked the performance of DLVPM against other widely used methods for multimodal data integration, in the task of identifying individually significant genetic loci associated with histology data. We found that DLVPM outperformed these methods in this task (Extended Data Fig. 8b).

As was previously noted, we trained our model on small tissue sections known as image tiles (Methods). Once the DLVPM model is trained, we can deconvolve tile-wide effects back into the image space. We used a neural network model that takes tiles at ×5, ×10 and ×20 magnifications (Extended Data Fig. 3). Figure 3b shows heat maps at each of these magnifications, for DLV 1. Histological effects and their molecular concomitants are explored in greater detail later in the Article.

Single-cell characterization

DLVPM acts to simultaneously integrate multiomic and imaging data, and reduce their dimensionality. This results in a compressed representation of important genetic and physiologic processes in cancer into a small number of DLVs. Once the overall model is trained, the individual measurement submodels can be used to help further characterize the model, and obtain deeper biological insights. For this purpose, we applied the trained DLVPM model to single-cell, cell-line and spatial transcriptomic data.

Cancer cells are the fundamental units of neoplastic disease. Tumours are composed of a diverse array of cancer and stromal cells, with distinct genetic and phenotypic properties. We applied the RNA-seq component of the full DLVPM model, trained on TCGA, to data from the single-cell breast cancer encyclopaedia, which contains RNA-seq data from 100,064 single cells59. This allows us to determine individual cell types that contribute significantly to each DLV, providing increased phenotypic resolution and potential insight into heterotypic interactions between cells that are typical of tumours scoring highly on different DLVs.

In concordance with earlier results, the first DLV exhibits strong negative enrichment for luminal cells types; this DLV also shows strong positive enrichment for basal and cycling cancer cells, which indicate a more aggressive molecular type (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, DLV 3 shows extremely strong positive enrichment for myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblasts (myCAFs), a subtype of CAFs identified by their expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin, which contributes to their effect on the tumour microenvironment, affecting tissue stiffness, cancer cell invasion and immune suppression, making them an important marker for aggressive cancer types60. Results from this secondary analysis highlight the capability of the DLVPM model to elucidate complex cellular interactions within tumours, enhancing our understanding of cancer cell dynamics and tumour heterogeneity.

a, Stratification of single cells based on the DLVPM model, applied to their transcriptomic profiles. The error bars show the mean-centred 99.9% bootstrapped confidence intervals. DCs, dendritic cells; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; NK, natural killer; NKT, natural killer T; PVL, perivascular‐like. b, Conceptual illustration showing the general principle of synthetic lethality. The up and down arrows associated with the genes represent different states, for example, mutated/non-mutated. Genetic features are synthetically lethal if the cell viability is affected when they both take on a particular state in the cell. Here, this is represented by the up arrows. The right part of the panel shows how DLVPM can be used to uncover new genetic vulnerabilities using this principle. DLVs are constructed from the sequencing data, and are used to predict susceptibility to gene knockout. c, For each data type, these plots show the mean Pearson’s correlation of each DLV, with DLVs from data types connected by the path model. The error bars on the plot denote the mean-centred 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (n = 61 for RNA-seq, n = 67 for SNVs, n = 50 for miRNA-seq). d, Association matrices for all the five DLVs. The entries in the top triangular part of the matrix indicate the Pearson’s correlation values between the different data types. The entries in the bottom part of the matrix are significance values for these correlations, obtained using permutation testing (n = 61 for RNA-seq, n = 67 for SNVs, n = 50 for miRNA-seq). e, Magnitude of associations between DLVs and CRISPR–Cas9 gene dependency scores, against their family-wise error-corrected significance levels. The labelled genes are those with significance levels under P = 0.05. We only show the volcano plots in which there was a significant association between the DLVPM variable and the CRISPR–Cas9 data (n = 42 for RNA-seq, n = 45 for SNVs, n = 34 for miRNA-seq). f, Associations between the first RNA-seq DLV and first miRNA-seq DLV, and the histone modification H3K4me1 (n = 49 for RNA-seq, n = 49 for miRNA-seq). Data are presented as linear regression lines (centre) with 95% confidence intervals (error bands). Panel b created with BioRender.com.

Cancer-cell-line characterization

To further evaluate the utility of the DLVPM model, we applied it—having been trained on TCGA patient data—to multiomic cell-line data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). Our objective was to explore if breast cancer cell lines, stratified on the basis of DLV profiles, exhibited differential sensitivity to genome-wide knockouts, facilitated by CRISPR–Cas9 loss-of-function screens. This approach not only promises to enhance our understanding of the biological importance of each DLV but also identifies potential therapeutic targets by pinpointing gene knockouts that exhibit synthetic lethal interactions in specific cancer contexts. This analysis utilizes data from the cancer dependency map61. A schematic of the analysis is shown in Fig. 4b.

We first tested if associations between omics DLVs specified by the DLVPM model trained on the TCGA patient data replicated in the cell-line data from the CCLE. We found that the first four DLVs retained significant associations (Fig. 4c), with correlations between RNA-seq and miRNA-seq DLVs exhibiting a particularly large effect (Fig. 4d).

We then conducted analyses to identify synthetic lethal interactions between DLVs and genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 dependency scores. Without using any biologically informed priors, and using a model trained on patient rather than cell-line data, we identified several genes that are already targets of frontline therapies in breast cancer (Fig. 4e). These associations were linked to DLV 1: as previously noted, ESR1 encodes an oestrogen receptor and ligand-activated transcription factor. The protein encoded by this gene regulates the transcription of many oestrogen-inducible genes involved in growth, metabolism, gestation and sexual development. Endocrine therapy to inhibit oestrogen is an extremely important therapy for oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancers42. The first RNA-Seq DLV also shows a dependence on both the cyclin-dependent kinase-encoding gene CDK4 and its regulator CCND1. Higher CCND1 expression has been linked to an increased risk of death in ER+ breast cancer62. Drugs designed to inhibit the action of CDK4 protein products have recently been shown to improve prognosis in hormone-dependent cancers, beyond the use of endocrine therapy alone63. GATA3 showed a very high synthetic lethal dependency with DLV 1 in this cell-line data. As previously noted, the GATA3 protein has been shown to be crucial in the development of the mammary gland, and is critical to the luminal cell program in the breast64,65. GATA3 encodes a protein that acts as a pioneer factor, a special type of transcription factor that can bind directly to chromatin. Pioneer factors have been called the master regulators of the epigenome and of cell fate66, which operate by opening previously inaccessible regulatory elements. These factors have the largest effect on transcription via histone modification and chromatin remodelling66. We calculated the association between the first RNA-seq and miRNA-seq DLVs and the global chromatin profile, which showed a strong link to the histone modification H3K4me1. For RNA-seq, this association was r = –0.49 (P = 1.74 × 10−4, n = 49); for miRNA-seq, r = −0.40 (P = 0.0063, n = 49; Fig. 4f).

Cells with low scores on DLV 1 were susceptible to the knockout of a wholly different set of genes (Fig. 4e). The strongest dependency relation was with CDC16; this gene is part of the APC/C (anaphase-promoting complex, also known as the cyclosome), which governs exit from mitosis67. PPWD1 is thought to be involved in protein folding68, but its role in cancer is less well studied.

Cells scoring low on the miRNA-seq component of DLV 3 were susceptible to the knockout of EXOSC2. The overexpression of EXOSC2 has been previously shown to promote breast cancer cell growth, migration, angiogenesis and tumour formation, whereas its knockdown reduces these effects69.

We repeated these analyses using an RNAi loss-of-function screen and obtained largely similar results (Extended Data Fig. 9). Following multiple comparisons correction, no significant dependency relations were uncovered using individual genetic features, highlighting the benefit of our polygenic, compared with monogenic approaches. In summary, our cancer dependency map analysis underscores that it is possible to identify genes essential to the cellular functioning of certain molecular subtypes of breast cancer using a DLVPM model trained on patient data. Our findings suggest that DLVs can serve as biomarkers for identifying cell lines that are particularly susceptible or resistant to specific genetic interventions, underscoring the potential for DLVPM-guided targeted therapies in oncology.

Spatial transcriptomics

Our analyses using the DLVPM model identifies histological concomitants of polygenic modes of variation in cancer, and their synthetic lethal genetic dependencies. Spatial transcriptomic data offer a more spatially resolved view of the genetic basis of aberrant changes in tissue structure. We found the genes ESR1, GATA3 and CCND1 to be highly dependent on DLV1 based on gene dependency scores from CRISPR–Cas9 screens. Each of these genes showed an individually significant association with histology (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 5), and are also included as part of the Xenium spatial transcriptomic gene panel70. We used the Xenium spatial transcriptomic data to investigate the association between the expressions of these genes, and the histological concomitants of DLV 1 across individual tumours. We assessed tile-wise effects at ×20 magnification, as this resolution is closest to the subcellular Xenium resolution.

We found significant associations between the spatial distribution of each of these genes and the histological component of DLV 1 (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 10) in both invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma—the two most common histological types of breast cancer. The strong association between these genes is indicative of their close functional relationship in breast cancer. Each of these genes is the most highly expressed in relatively well-differentiated tumoural regions. This is where the histological component of DLV 1 also scores the lowest. This is consistent with the suggested role of these genes in the early stages of tumour growth and progression.

a, Tile-wise heat maps generated from the DLVPM model, trained on the TCGA data, and applied to histological and associated spatial transcriptomic data. The colour map is flipped for the normalized histology heat map as this DLV shows a negative association with the genes of interest. We applied this analysis to invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma. The association/significance matrices on the right show correlations between the genes of interest and the first histological DLV for both tumours. The top triangular part of each matrix is denoted with the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between each gene and the histology data. The bottom triangular part of each matrix denotes the significance level between genes and histology data. b, Left, a cancerous breast duct, which scored highly on DLV 1. Middle, a feature attribution map, generated using integrated gradients, illustrating the regions of the tumour that contributed most to the DLVPM model. Right, spatially mapped GATA3 transcripts.

To pinpoint the histological features that have a pivotal role in linking genetic profiles with histological patterns at a more granular, subtile resolution, we applied the integrated gradients method for feature attribution71 (Fig. 5b). This attribution technique assigns importance scores to specific image regions, thereby identifying those that have a pronounced influence on the predictions made by DLV 1. Of particular interest, well-differentiated ductal regions received increased scores, highlighting their marked importance in the model’s determination. Furthermore, these regions show a high concentration of key genetic markers, including GATA3, CCND1 and ESR1. The DLVPM analyses carried out on Xenium data forge a connection between the functional essentiality of genes (as assessed by CRISPR–Cas9 loss-of-function screens) and their spatial expression patterns, framing an integrated model of disease pathology.

Discussion

DLVPM is a method for modelling dependencies between different data types. This method stands out for its ability to uncover complex, nonlinear interactions among both structured and unstructured data types, overcoming the limitations of traditional path-modelling techniques23. Initially trained on the extensive TCGA dataset, the modular nature of the method allows for flexible adaptation and further refinement with additional analyses using single-cell, cell-line and spatial transcriptomic data. By applying DLVPM to cancer dependency map data, it unveils critical insights into multiomic dependencies. Furthermore, DLVPM bridges microscopic tissue structure changes with genetic vulnerabilities identified by the same model, illustrating its ability to construct holistic models of illness pathology. This method’s comprehensive data integration capability marks an important step forward, promising applicability beyond cancer to a broad spectrum of diseases.

DLVPM is superior to classical approaches to path modelling in terms of the magnitude of associations the method is able to establish between different data types. This is likely because, in contrast to classical approaches, this method is able to model the complex breakdown in molecular machinery that underpins carcinogenesis. Typically, cancer initiation requires mutations or epigenetic changes in several driver genes. These alterations can affect gene expression at thousands of loci. Many of these genes will be transcription factors, whose purpose is to control the expression of other genes. Classical methods are unable to parse this complexity as they are only able to model linear effects. By contrast, deep learning methods have already been shown to be capable of modelling complex interactions between loci across the genome12,13.

Historically, researchers have developed drugs that target oncogenes and block their function. However, not all cancers have oncogenes, which limits the number of possible drug targets. To overcome this challenge, researchers have utilized the principle of synthetic lethality72. Synthetic lethal interactions in cancer can be probed using functional genetic experiments such as CRISPR–Cas9 loss-of-function screens. Associations between cells’ molecular features and susceptibility to knockout of a particular gene represent a synthetic lethal interaction. This results in an enormous multiple comparison problem. This approach also fails to respect the intrinsically polygenic nature of cancer as an illness. DLVPM simultaneously integrates the multiomic data it is applied to, and reduces its dimensionality, resulting in a small number of polygenic, multiomic DLVs, avoiding both major pitfalls associated with taking a single-gene approach.

Despite the versatility and power of DLVPM, several limitations warrant careful consideration. First, like other deep-learning-based methods applied in biology, without further analysis or experimental work, results can be difficult to interpret due to the black-box nature of neural networks, which often lack transparency in linking learned features to specific biological processes73. This inherent opacity also necessitates special care in validating the results on external datasets. Another weakness of the method is that it requires a full complement of multimodal data. In classical partial least squares (PLS), sophisticated methods for the imputation of missing data have been developed; this is an area for future research74. Another technical issue is that the method requires reasonably large batch sizes, an issue common to correlation-based deep learning methods75.

DLVPM is implemented in the flexible and user-friendly TensorFlow/Keras ecosystem, enabling the modular construction of complex models tailored to a wide array of data analysis tasks. Using predefined Keras layers, users can define new DLVPM models in just a few lines of code. This modular design not only simplifies the development and testing of sophisticated models but also enhances their extensibility, ensuring that our method can be seamlessly applied across diverse research fields and data types. This toolbox also contains a submodule for confound removal, which can also be used in classification and regression problems, and we anticipate it as being generally useful to the deep learning field.

Many illnesses arise as a result of complex interactions between multiple biological and environmental factors. Several, large, open-access databases, such as the UK Biobank76, the European Genome-phenome Archive77 and the Cancer Imaging Archive78 have been created to help understand these factors, and contain large amounts of multiomics and imaging data. Furthermore, new technologies such as single-cell79 and spatial multiomics80 produce enormous quantities of data that need to be integrated and reduced to be understood. DLVPM is ideally suited for this task, as it is able to link arbitrarily many data modalities, including both structured and unstructured data. In this investigation, we showed how DLVPM can be used to construct a global model of breast cancer as an illness. Using this method, wholly different but connected manifestations of the same underlying illness can be understood with reference to the same neural network model.

Methods

DLVPM

Here, we give a general introduction and a full technical treatment of the DLVPM method. DLVPM can be thought of as a generalization of PLS-PM23. PLS-PM can be considered, in turn, to be a generalization of canonical correlation81. It is therefore natural to build an understanding of DLVPM with reference to these simpler methods. It is worth noting that we could have called our method Deep PLS-PM. However, we felt that DLVPM was more descriptive. We also wished to avoid confusion with the more popular PLS regression procedure.

The description of the DLVPM method we present here is broken into three basic parts:

-

1.

a description of shallow (that is, non-deep-learning-based) methods for establishing correlations between different data types;

-

2.

deep neural networks and notation;

-

3.

a description of DLVPM, and how deep learning can be used to identify complex, nonlinear associations between different data types.

Canonical correlation analysis

Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) is a statistical method used to identify linear relationships between two or more sets of variables81. This method can be thought of as a generalization of linear least squares regression. The objective of CCA is to identify a relationship between two (or more) sets of variables, where there is no distinction between which variables are considered dependent and which are considered independent. This method identifies weights for each variable, such that the weighted sum of variables in each set is maximally correlated with the weighted sum of variables from the opposite set, assuming a linear relationship81.

Consider two matrices X1 and X2, where each row denotes one of N observations, and each column denotes p1 or p2 features for X1 and X2, respectively. CCA is optimized to find weight vectors w1 and w2 that maximize the association

We assume that the columns of X1 and X2 have been standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Using the equation used to find Pearson’s correlation coefficient, we get

Notice that the denominator is simply a normalization term. Therefore, the canonical correlation objective can also be written as

subject to the constraints

Here the vectors X1w1 and X2w2 are referred to as canonical variates.

In the original formulation, the canonical weights that maximize the association between the two data views are normally found using eigenvalue decomposition. It is possible to find multiple modes of variation using this method. Here the correlation between subsequent canonical variates is maximized subject to their being uncorrelated with other canonical variates. A total of ndims = min(p1, p2) canonical variates can be extracted in this way. This can be written as

subject to the orthogonalization constraints

and

where W1 and W2 are p1 × ndims and p2 × ndims matrices, respectively; and I is an ndims × ndims identity matrix.

Generalizing CCA

Hotelling’s original formulation of CCA was designed to identify associations between two data views. Researchers have generalized CCA to more than two data views82. There are a number of different ways in which this can be done. One way to generalize the CCA approach is to optimize the sum of correlations between different data views. This involves maximizing the following criteria:

where K is the total number of data views under analysis, and i and j index different data views, subject to the orthogonalization constraints

PLS-PM

The canonical correlation procedures described in the text above can be used to identify latent variables that are highly correlated between multiple data types. In some cases, we may wish to identify associations between some—but not all—data types. For example, a particular disease phenotype may have both genetic and environmental causes. It does not make much sense to try to link these genetic and environmental causes as they should be independent. Any model that attempts to link these data types may end up highlighting spurious effects.

The mathematical framework above, described with relation to generalized CCA, can be used to formulate a kind of structural-equation-modelling procedure called PLS-PM83,84. Using PLS-PM, it is possible to identify associations between prespecified data types. Utilizing this method, we specify which data types are connected with one another using a predefined adjacency matrix C. The adjacency matrix is a square matrix in which the elements cij represent connections between views i and j:

where K is again the total number of data types under analysis.

The optimization criteria can then be written as

subject to the constraints

where cij represents the binary indexed elements of C.

Using PLS-PM, the full modelling process is normally referred to in two parts: the structural model and the measurement model. The structural model is the part of the model that defines which inter-relations are to be optimized between the data types; this information is stored in C. The measurement model is the part of each model (denoted by XiWi ∀ i) that links individual features to latent variables in the path model23.

Deep neural networks and notation

Neural networks are computational models composed of layers of interconnected ‘neurons’ that perform calculations. During training, these networks adjust neuron connection weights via backpropagation, where they compute the gradient of a loss function (the difference between predicted and actual data) and iteratively update the network weights. The outputs of most neural networks can be written in the very general form:

where \(\overline{Y}\) is the network output and F(X, U) is some function that takes an input X and passes it though sets of weights and biases U. This could be many kinds of neural network, for example, a feed-forward neural network, a convolutional network or a transformer. The network output can be written more simply still as \(\overline{Y}(X,U\;)\).

Each of the methods described in the text below relies on the last layer of the neural network having a linear projection weight. Treating this weight differently in the notation is crucial to understand the mechanisms by which DLVPM functions. Therefore, neural networks processing individual data types in DLVPM are written as \(\overline{Y}(X,U,W\;)\), where U represents all weights and biases in the network up to the penultimate layer and W represents the weights on the last layer of the network. We use this very simple notation to denote neural networks in the rest of the text.

Deep canonical correlation

Andrew et al. developed a two-view form of CCA, which they termed deep CCA85. Deep CCA creates highly correlated representations of two data types by passing them through deep neural networks. The goal of the algorithm is to learn weights and biases of both data views such that we seek to maximize

subject to the orthogonalization constraint

where ndims is the total number of canonical variates we wish to extract.

This optimization problem can be written in the matrix form as

subject to the orthogonalization constraint

where \({\bar{Y}}_{i}\) is a column-wise concatenation of \({\bar{Y}}_{i}={\bar{y}}_{i}^{1}\leftrightarrow {\bar{y}}_{i}^{2}\leftrightarrow \ldots \leftrightarrow {\bar{y}}_{i}^{{n}_{\rm{dims}}}\) (↔ signifies the column-wise concatenation of CCA factors) and I is the identity matrix. Here W1 and W2 represent the set of all weights \({w}_{1}^{1},{w}_{1}^{2},\ldots ,{w}_{1}^{{n}_{\rm{dims}}}\) and \({w}_{2}^{1},{w}_{2}^{2},\ldots ,{w}_{2}^{{n}_{\rm{dims}}}\), respectively.

Andrew et al.’s formulation of this procedure operates by taking the derivative of the cross-covariance matrix between the data views. However, this approach is difficult to generalize to more than two data views. Wang et al.86 formulated an iterative least squares approach to this method. This involves minimizing the loss

subject to the orthogonalization constraint given above. We use a similar iterative least squares regression approach in the present investigation.

DLVPM

The goal of the DLVPM algorithm is to identify orthogonal modes of association between data views connected by the user-defined adjacency matrix C. As before, the adjacency matrix is a square matrix in which the elements cij represent connections between views i and j. This method is essentially a deep analogue of PLS path modelling. This adjacency matrix is often referred to as the structural or path model.

We therefore seek to maximize

subject to the orthogonalization constraint

Taking the iterative regression approach followed by Wang et al. and described with reference to classical canonical correlation and PLS-PM earlier in the text, we can maximize the association between network outputs by minimizing the loss

Orthogonalization

The DLVPM algorithm can be split into two fundamental parts: an optimization step aimed at finding factors that are strongly correlated between data views, and a constraint that ensures DLVPM factors are orthogonal to one another. It is possible to identify a single factor of shared variance between sets without the orthogonalization step. The loss associated with finding a single DLVPM factor can be written as

In cases where we wish to identify more than a single factor of shared variance between data views, an orthogonalization step is required to decorrelate factors. We used two different approaches to orthogonalization in the present investigation. We first introduce an orthogonalization procedure inspired by classical PLS, which is used in the main part of this investigation. We also compared this approach to a whitening procedure, similar to the approach used in Wang et al.86.

Iterative orthogonalization

In the present investigation, we use a matrix deflation approach inspired by classical PLS-PM. This approach has the advantage that it maintains the proper ordering of DLVPM factors. During the forward pass through the network, data are orthogonalized with respect to previous DLVPM factors. Individual DLVPM factors are written as follows

The set of all DLVPM factors in a data view can be written as

where \({\bar{Y}}_{i}\) is an N × ndims matrix of DLVPM factors and Wi is a matrix of DLVPM weights. \({\bar{Y}}_{i}\) is a column-wise concatenation of \({\bar{Y}}_{i}={\bar{y}}_{i}^{1}\leftrightarrow {\bar{y}}_{i}^{2}\leftrightarrow {\ldots}\leftrightarrow {\bar{y}}_{i}^{{n}_{\rm{dims}}}\). Similarly, we define the matrix \({{\bar{Y}}_{i}}^{n}\) as the concatenation of all vectors from the first to the nth.

We denote the penultimate layer of the neural network with the notation Fi(Xi, Ui). It is a well-known property of regression that the residual features, denoted by \({F}_{i}({X}_{i},{U}_{i}|{{\overline{Y}}_{i}}^{n})\), found in the regression

are orthogonal to \({\bar{Y}}_{i}^{\;n}\) (utilizing the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse). We use this mechanism to identify orthogonal modes of variation using DLVPM.

We can then write the loss for the nth extracted latent factor, for the ith data view as

given that \(\,{L}_{i}^{n}\) is a sum of regression problems. We can then write the total loss for the ith data view as follows

Li is, therefore, written as a sum of the mean squared error losses across latent factors.

Similarly, the total loss can be calculated as the sum of losses across all data views

Owing to the orthogonalization process introduced in the text above, this formulation meets the following constraints

It is worth noting at this point that due to these constraints,

where I is the identity matrix. This means that the orthogonalization procedure

simplifies to

DLVPM minimizes this loss in an iterative fashion by calculating the gradients associated with each data view and updating the weights of these data views.

So far, the analysis of the DLVPM algorithm has preceded assuming that training is carried out on the entire dataset simultaneously. However, neural networks are usually trained on subsets or batches of data whereas orthogonality is a property of the full dataset. Orthogonalization requires estimating a covariance matrix.

We calculate the covariance matrices above during model training, by making an initial estimate of the covariance matrices using the first batch and then updating this estimate using parameter re-estimation with momentum for each batch. The batch-level covariance matrices for the first batch are written as follows

The global covariance matrices for the first batch are then initially estimated as

where N is the total number of samples and b0 is the size of the first batch. In subsequent batch updates, covariance matrices are calculated as

where ρ is the momentum of the update, N is the total number of samples under analysis and bt is the size of the current batch and ρ is a hyperparameter that defines how quickly the covariance matrices are updated using the current batch. In the present investigation, we used a value of ρ = 0.95, which represents a trade-off between maintaining stable, smooth updates and allowing sufficient responsiveness to changes in newer data.

This algorithm allows us to learn global matrices for orthogonalization, which can then be used during inference. Nevertheless, we found that using these covariance matrices during training were ineffective at enforcing orthogonality. This is likely because using global covariance matrices does not enforce orthogonality at the batch-wise level. This means that gradient updates can also be non-orthogonal. However, if we use batch-wise orthogonalization, this condition is strongly enforced.

Consider the subloss for a particular data view, for a particular dimension of shared variance:

Taking the gradient of \({L}_{i}^{n}\) with respect to the weight \({w}_{i}^{n}\) gives

Using batch-wise covariance matrices, we get

and

Therefore, the gradients are orthogonal.

For these reasons, the algorithm we used functions differently in training and testing. During model training, we implement orthogonalization using batch-wise covariance matrices. Global covariance matrices are used during testing. This different behaviour during training and testing, using batch-wise and global parameters, respectively, is similar in purpose and implementation to the batch normalization layer. The full algorithm specifying this method is shown in Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1. Pseudo-code illustrating how this algorithm works is shown below:

DLVPM with iterative orthogonalization

Input: data matrices \({{{X}}}_{{{i}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{{N}}\times {{p}}}_{{i}}}\) for i = 1, 2…K. Initialization of the weights Wi, Ui for each data view, momentum ρ and learning rate η. Randomly choose a mini-batch and extract data for each data view as \({{{{X}}}_{{{i}}}}_{{{{b}}}_{0}}\).

During training

For t = 0, 1, 2,…,T, do:

Forward propagate through the network:

For i = 1, 2,…,K, do:

For i = 1, 2,…,K, do:

Compute the batch mean and variance:

For n = 1, 2…ndims, do:

If n = 1:

Else

If t = 0

Define global variables, moving mean and moving variance:

Covariance matrix (for orthogonalization):

Else

For subsequent batches, update the batch moving mean and moving variance:

Update the moving covariance matrices:

Update the weights:

During inference

For i = 1, 2…K, do:

Forward propagate through the network:

If n = 1:

Else

Whitening

Whitening offers a different way of orthogonalizing DLVs. This method of orthogonalization was used by Wang et al. in their formulation of deep CCA86.

Using the definitions of Yi and Wi outlined earlier in the text, we can write the objective as

subject to

We note that if we multiply Yi by the matrix square root of its inverse, we get the following.

Then, the columns of Yi, representing different modes of variation, are uncorrelated. In other words, the orthogonality condition is met.

We introduce another algorithm, which again minimizes the global loss by iteratively minimizing the sum of the squared loss between each data view and connected data views. Using the whitening approach, we iteratively minimize the loss as follows

As was the case when minimizing the loss using the iterative orthogonalization approach specified above, when trained at the batch-wise level, we must estimate a global covariance matrix. We do this in a similar manner to the way in which we estimated global covariance matrices using the iterative orthogonalization approach. As noted in the explanation of the iterative orthogonalization algorithm, training using deep learning is generally carried out at the batch-wise level.

For the first batch, in each data view, the covariance matrix is initially estimated as follows.

Subsequent batches are then estimated as follows.

The full pseudo-code for estimating a DLVPM model using the whitening orthogonalization approach is given below. Note that finding the matrix inverse can be computationally intensive for large embedding sizes. Using the Cholesky decomposition can be substantially quicker in finding \({({\bar{Y}_{j}}^{\rm{T}}\bar{Y}_{j})}^{-1/2}\bar{Y}_{j}\). Therefore, this is offered as an option in the DLVPM toolbox.

DLVPM with whitening

Input: data matrices \({{{X}}}_{{{i}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{{N}}\times {{p}}}_{{i}}}\) for i = 1, 2…K. Initialization of the weights Wi, Ui for each data view, momentum ρ and learning rate η. Randomly choose a mini-batch and extract data for each data view as \({{X}_{i}}_{{\rm{b}}_{0}}\).

During training

For t = 0, 1, 2…T, do:

Forward propagate through the network:

For i = 1, 2…K, do:

For i = 1, 2…K, do:

Compute the batch mean and variance:

If t = 0:

Define global variables, moving mean and moving variance:

Covariance matrices (for orthogonalization):

Else

For subsequent batches, update the batch moving mean and moving variance:

Update the moving covariance matrices:

Update the weights:

During inference

For i = 1, 2…K, do:

Forward propagate through the network:

DLVPM-Twins

Although DLVPM is primarily designed to identify associations between multiple data views, it can also be used to find useful representations of a single data view, which can then be used for downstream tasks. When used in this manner, DLVPM falls into the class of methods called Siamese or twin networks. This class of methods has become popular across a wide range of fields in recent years. Twin architectures are trained by feeding a neural network with distorted versions of the same input. By using some kind of correlative loss on the output features (as is the case with DLVPM), the network is encouraged to learn representations that are invariant to these distortions, which can be useful in downstream analyses.

When using DLVPM in this way, the loss can be written as

subject to the orthogonalization constraint

Here XA and XB are augmented/distorted versions of the same input X. Note here that the weights and biases associated with the networks are the same for the entities we are seeking to maximize associations between. The network is then optimized to learn model outputs that are invariant to user-specified changes in the input.

DLVPM-Twins can be used with both iterative orthogonalization and whitening approaches. The algorithms defining these approaches are very similar to the full path-modelling algorithms. Therefore, they are not given here to avoid repetition.

Removing confounds

Data are often subject to unwanted confounds that can affect the validity and generalizability of inferences made on these data. When assessing linear effects, these confounds can be removed by including them as covariates of no interest in a general linear model, or preregressing these unwanted effects from data before the analysis. We took a similar approach to removing confounding effects in neural networks. The last layer of a DLVPM model is linear. Therefore, removing confounding contributions before this layer will remove them entirely.

Here a set of confounds is denoted by an N × Dc matrix C, where N is the number of samples, and Dc is the number of confounds. F(X, U) has the same definition, given earlier in the text.

We implement the operation

The matrix (CTC)−1CT is known as the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse. It is a well-known result that columns of the resulting matrix (F(X, U)|C) are orthogonal to the columns of the matrix C.

When using DLVPM, we can use this approach to orthogonalize neuronal outputs with respect to a set of confounds in the penultimate layer. As projection layers are linear, the outputs of the measurement model will be orthogonal to these confounds. As with the DLV orthogonalization described earlier in the documentation, we must adapt this orthogonalization so that it is possible to train models using this approach at the batch-wise level.

The matrix

can be split into two covariance matrices, namely,

and

Batch-wise estimates of these matrices can be used to estimate full sample matrices. Batch-wise covariance matrices are written as

and

We can then carry out orthogonalization at the batch-wise level using

As in the case of carrying out orthogonalization between DLVs, we must also estimate full-sample covariance matrices so that we can carry out orthogonalization with respect to these parameters in unseen test data.

Global covariance matrices for the first batch are estimated as

and

In subsequent batches, these covariance matrices are updated with momentum:

and

where ρ denotes the momentum.

At the model test time, these covariance matrices are then used to orthogonalize the signal that is forward propagated through the network, with respect to the confounding variables.

Full pseudo-code illustrating this process is given below.

Confound removal

Input: Data matrices \({{{X}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{{N}}\times {{p}}}}\) and confound matrices \(C\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{N}}\times {{{D}}}_{{\rm{c}}}}\).

During training

For t = 0, 1, 2…T, do:

Compute the batch mean and variance:

\({\mu }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}=\frac{1}{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{n=1}^{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}{F}({X}_{{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}},{U})\quad{{\sigma }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}}^{2}=\frac{1}{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{n=1}^{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}{({F}({X}_{{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}},{U})-{\mu }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}})}^{2}\)

\(F({X}_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}},\,U\,){\rm{\leftarrow }}(F({X}_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}},\,U\,)\,-{\mu }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}})/{\sigma }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}\)

If t = 0:

Define global variables, moving mean and moving variance:

\({\sigma }^{2}={{\sigma }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}}^{2},\mu ={\mu }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}\)

Covariance matrices (for orthogonalization):

\({{\sum }}_{CC}=\frac{N}{{\rm{b}}_{0}}{{C}_{{\rm{b}}_{0}}}^{\rm{T}}{C}_{{\rm{b}}_{0}}\) and

\({{\sum }}_{CF}=\frac{N}{{\rm{b}}_{0}}{{C}_{{\rm{b}}_{0}}}^{\rm{T}}F({X}_{{\rm{b}}_{0}},U\,)\)

Else

For subsequent batches, update the batch moving mean and moving variance:

\(\sigma ={\rho}\times \sigma +(1-{\rho})\times {\sigma }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}\)

\(\mu ={\rho}\times \mu +(1-{\rho})\times {\mu }_{{\rm{b}}_{\rm{t}}}\)

Update the moving covariance matrices:

and

Use these covariance matrices to remove the confounding effects:

During inference

Forward propagate through the network:

TCGA data

We initially applied DLVPM to data from the TCGA study (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Here we only used breast cancer patients with a full complement of data including histological images, RNA-seq, miRNA-seq, methylation and SNVs. To ensure we only used the highest-quality data, we subjected it to several selection steps before its use. We only used samples with a tumour purity above 60%. This threshold was chosen to minimize contamination from non-cancerous cells, thereby reducing background noise and increasing the precision of genetic and epigenetic profiling. By focusing on samples with higher tumour purity, we aimed to obtain clearer insights into tumour-specific molecular pathways and genetic alterations. The acquisition site can have a strong effect on both omics and imaging data32. We introduced a method to remove the effect of acquisition site (see the ‘Removing confounds’ section). However, when a small number of samples is associated with a covariate, it is not possible to disentangle biological effects and effects driven by this nuisance covariate. Therefore, we only used data from acquisition sites that contributed at least ten samples to the TCGA study. We only used female participants. 758 patient samples had a full set of SNV, methylation, miRNA-Seq, RNA-Seq and histological data available for the full path-modelling analysis.

Both DLVPM-Twins and full DLVPM path-modelling analysis require the sampling of subsections of each whole slide image (WSI) called image tiles. The first step in that process was to identify which parts of the overall image contain histological tissue. We did this by calculating Sobel’s image gradient across the whole slide. We then split the tissue into 224 × 224-pixel sections, subsequently referred to as image tiles. This tile size is the input size required by the EfficientNetB0 architecture36 used throughout this study. This process was used at ×5, ×10 and ×20 magnifications. Tiles in which the average Sobel’s image gradient was over 15 for over 50% of the image were considered to contain enough tissue to be used in further analyses.

Omics data are very high dimensional. First, we reduced the data dimensionality for each omics modality. In the case of methylation and RNA-seq data, we did this by finding the genes with the top 10% highest variance. miRNA-seq data have much lower dimensionality; therefore, we used the top 50% here. Omics data such as RNA-seq are often heavily skewed. We subjected all omics data to a rank-based inverse Gaussian transform to remove this data skew. TCGA data are typically of very high quality. However, a very small fraction of the methylation data (0.054%) was missing and coded as NaNs. As all omics data are centred on zero after z normalization, we simply replaced these values with zeros, representing the mean, after normalization. This is common practice in multimodal data integration analyses87.

DLVPM-Twins model specification and training