Abstract

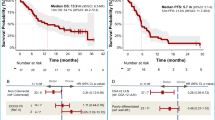

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) are heterogeneous tumors with limited treatment options. This phase 2 Bayesian study evaluated the combination of regorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, and avelumab, a programmed death 1 (PD1) ligand 1 inhibitor, in advanced grade 2–grade 3 well-differentiated GEP neuroendocrine tumors or grade 3 GEP neuroendocrine carcinomas after progression on prior therapies. A total of 47 participants were enrolled and 42 were evaluable for efficacy. Participants received regorafenib (160 mg per day) and avelumab (10 mg kg−1 biweekly) in 28-day cycles. The primary endpoint, 6-month objective response rate per the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors version 1.1, was 18% (95% confidence interval (CI): 8–31%), with a median progression-free survival of 5.5 months (95% CI: 3.6–8). Durable responses were noted (16.6 months; 95% CI: 3.7–no response). Treatment-related adverse events were manageable, with fatigue, diarrhea and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia being most common. Exploratory biomarker analysis identified PD1 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 expression and activity as potential resistance markers. These findings highlight the clinical potential of regorafenib and avelumab in GEP-NENs, emphasizing the need for predictive biomarkers and validation in future randomized trials. Clinical Trial registration: NCT03475953.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets that support the findings of this study are not publicly available because of regulations protecting participant privacy and consent under French and European laws. Access to the data requires prior approval from the ethics committee ‘Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est II’. Requests for data can be directed to the corresponding author (A.I.). Proposals will be reviewed by the committee and access may be granted following approval of the proposal. The estimated timeframe for approval is approximately 4–6 weeks. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Modlin, I. M. et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol. 9, 61–72 (2008).

Pavel, M. et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 31, 844–860 (2020).

Strosberg, J. et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 125–135 (2017).

Raymond, E. et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 501–513 (2011).

Yao, J. C. et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 514–523 (2011).

Yao, J. C. et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, nonfunctional neuroendocrine tumors of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 387, 968–977 (2016).

Mitry, E. et al. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with progressive advanced well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the gastro-intestinal (GI-NETs) tract (BETTER trial)—a phase II non-randomised trial. Eur. J. Cancer 50, 3107–3115 (2014).

Capdevila, J. et al. Lenvatinib in patients with advanced grade 1/2 pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: results of the phase II TALENT trial (GETNE1509). J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 2304–2312 (2021).

Mitry, E. et al. Treatment of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumours with etoposide and cisplatin. Br. J. Cancer 81, 1351–1355 (1999).

Fazio, N. et al. Chemotherapy in gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC): a critical view. Cancer Treat. Rev. 39, 270–274 (2013).

Garcia-Carbonero, R. et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Neuroendocrinology 103, 186–194 (2016).

Strosberg, J. et al. Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab in previously treated advanced neuroendocrine tumors: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 2124–2130 (2020).

Mehnert, J. M. et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of programmed death-ligand 1-positive advanced carcinoid or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: results from the KEYNOTE-028 study. Cancer 126, 3021–3030 (2020).

Yao, J. et al. Activity & safety of spartalizumab (PDR001) in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors of pancreatic, gastrointestinal, or thoracic origin, & gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma (GEP NEC) who have progressed on prior treatment. Ann. Oncol. 29, VIII467 (2018).

Chan, D. L. et al. Avelumab in unresectable/metastatic, progressive, grade 2–3 neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs): combined results from NET-001 and NET-002 trials. Eur. J. Cancer 169, 74–81 (2022).

Lu, M. et al. Efficacy, safety, and biomarkers of toripalimab in patients with recurrent or metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a multiple-center phase Ib trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 2337–2345 (2020).

Huang, Y. et al. Improving immune-vascular crosstalk for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 195–203 (2018).

De Palma, M., Biziato, D. & Petrova, T. V. Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 457–474 (2017).

Allen, E. et al. Combined antiangiogenic and anti-PD-L1 therapy stimulates tumor immunity through HEV formation. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaak9679 (2017).

Milosavljevic, T. et al. Effect of regorafenib on angiogenesis in neuroendocrine tumors in vitro. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, abstr. 232 (2016).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Spranger, S. et al. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and Tregs in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8+ T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 200ra116 (2013).

Herbst, R. S. et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 515, 563–567 (2014).

Larroquette, M. et al. Spatial transcriptomics of macrophage infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer reveals determinants of sensitivity and resistance to anti-PD1/PD-L1 antibodies. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e003890 (2022).

Platten, M. et al. Tryptophan metabolism as a common therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegeneration and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 379–401 (2019).

Bongiovanni, A. et al. Activity and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in neuroendocrine neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 14, 476 (2021).

Castillon, J. C. et al. Cabozantinib plus atezolizumab in advanced and progressive neoplasms of the endocrine system: a multi-cohort basket phase II trial (CABATEN/GETNE-T1914). Ann. Oncol. 34, S498–S502 (2023).

Weber, M. et al. Activity and safety of avelumab alone or in combination with cabozantinib in patients with advanced high grade neuroendocrine neoplasias (NEN G3) progressing after chemotherapy. The phase II, open-label, multicenter AVENEC and CABOAVENEC trials. Ann. Oncol. 34, S701–S710 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. Surufatinib plus toripalimab in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumours and neuroendocrine carcinomas: an open-label, single-arm, multi-cohort phase II trial. Eur. J. Cancer 199, 113539 (2024).

da Silva, A. et al. Characterization of the neuroendocrine tumor immune microenvironment. Pancreas 47, 1123–1129 (2018).

Hiltunen, N. et al. CD3+, CD8+, CD4+ and FOXP3+ T cells in the immune microenvironment of small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Diseases 9, 42 (2021).

Donini, C. et al. PD-1 receptor outside the main paradigm: tumour-intrinsic role and clinical implications for checkpoint blockade. Br. J. Cancer 129, 1409–1416 (2023).

Roberts, J. A. et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 in poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas of the digestive system: a potential target for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. Hum. Pathol. 70, 49–54 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Tumor cell-intrinsic PD-1 receptor is a tumor suppressor and mediates resistance to PD-1 blockade therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 6640–6650 (2020).

Shimizu, T. et al. Soluble PD-L1 changes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1308381 (2023).

Heo, S. K. et al. The presence of high level soluble herpes virus entry mediator in sera of gastric cancer patients. Exp. Mol. Med. 44, 149–158 (2012).

Oaks, M. K. et al. A native soluble form of CTLA-4. Cell. Immunol. 201, 144–153 (2000).

Gu, D. et al. Soluble immune checkpoints in cancer: production, function and biological significance. J. Immunother. Cancer 6, 132 (2018).

Bessede, A. et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of a disease tolerance defence pathway. Nature 511, 184–190 (2014).

de Hosson, L. D. et al. Neuroendocrine tumours and their microenvironment. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 69, 1449–1459 (2020).

La Salvia, A. et al. Metabolomic profile of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) identifies methionine, porphyrin and tryptophan metabolism as key dysregulated pathways associated with patient survival. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 30, lvad160 (2023).

Hato, T., Zhu, A. X. & Duda, D. G. Rationally combining anti-VEGF therapy with checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunotherapy 8, 299–313 (2016).

Huang, Y. et al. Vascular normalizing doses of antiangiogenic treatment reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhance immunotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17561–17566 (2012).

Johansson, A., Hamzah, J., Payne, C. J. & Ganss, R. Tumor-targeted TNFα stabilizes tumor vessels and enhances active immunotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7841–7846 (2012).

Bekaii-Saab, T. S. et al. Regorafenib dose-optimisation in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (ReDOS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 20, 1070–1082 (2019).

Cousin, S. et al. Regorafenib–avelumab combination in patients with biliary tract cancer (REGOMUNE): a single-arm, open-label, phase II trial. Eur. J. Cancer 162, 161–169 (2022).

Cousin, S. et al. Regorafenib–avelumab combination in patients with microsatellite stable colorectal cancer (REGOMUNE): a single-arm, open-label, phase II trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 2139–2147 (2021).

Von Hoff, D. D. There are no bad anticancer agents, only bad clinical trial designs—twenty-first Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation Award Lecture. Clin. Cancer Res. 4, 1079–1086 (1998).

Zohar, S. et al. Bayesian design and conduct of phase II single-arm clinical trials with binary outcomes: a tutorial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 29, 608–616 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Institut Bergonié. Funding was provided by Bayer, the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer and the French NCI (INCA). Nonfinancial support was provided by Merck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.I., A.B. and C.B. conceptualized and designed the study. I.S. and L.V. performed the histologic analyses. S.C., L.J.P., S.P., J.P.M., E.A., I.K., P.A.C., A.H., M.K., H.S. and A.I. provided study material or treated participants. All authors collected and assembled the data. A.I., A.B., C.C. and J.P.G. developed the tables and figures. A.I., A.B. and J.P.G. conducted the literature search and wrote the manuscript. All authors were involved in critical review of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.B. and J.P.G. are employees of Explicyte. A.I. received research grants from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Chugai, Merck, MSD, Pharmamar, Novartis and Roche and personal fees from Epizyme, Bayer, Lilly, Roche and Springworks. W.H.F. received a research grant from AstraZeneca and personal fees from Anaveon, AstraZeneca, Catalym, Elsalys, Novartis, OSE Immunotherapeutics and Parthenon. J.Y.B. received research grants from Bayer, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Pharmamar and Roche and personal fees from Bayer, GSK, Lilly, Novartis, Pharmamar and Roche. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cancer thanks Junki Mizusawa, Rachel Riechelmann and Thomas Walter for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Flow chart of the REGOMUNE study.

Forty-seven patients were enrolled in the study, of whom 46 were evaluated for safety and 42 for efficacy.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Growth modulation index.

Waterfall plot depicting the growth modulation index (GMI) in patients (n = 42) with advanced gastro-enteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms receiving regorafenib and avelumab.

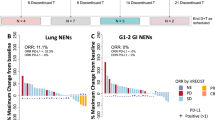

Extended Data Fig. 3 CD8+ and CD163+ cell infiltration are not associated with response to regorafenib and avelumab in GEP-NEN patients.

(A) Illustration of 7-plex immunohistofluorescence panel. (B-C) Boxplot representation (median ± interquartile range) of CD8+ (B) and CD163+ (C) cell density in patients with progressive disease (PD – n = 9 patients), stable disease (SD – n = 15 patients) and partial response (PR – n = 6 patients). P values were calculated using two-sided Wilcoxon tests.

Extended Data Fig. 4 IDO1 activity according to GEP-NEN histotypes.

Boxplot representations (median ± interquartile range) of the density of PanCK + /IDO+ (A) and the ratio of plasma Kyn/Trp levels (peripheral IDO1 activity) (B) in GEP-NEN patients according to histotypes (n = 30 patients for A and n = 37 for B). P values were calculated using two-sided Wilcoxon tests. (C) Heatmap representation of plasma levels of immune-related proteins dosed using Olink Target96 panels according to histotypes (n = 35 patients).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Study protocol.

Supplementary Information

Statistical analysis plan.

Supplementary Information

REMARK checklist.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cousin, S., Guégan, JP., Palmieri, L.J. et al. Regorafenib plus avelumab in advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: a phase 2 trial and correlative analysis. Nat Cancer 6, 584–594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-025-00916-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-025-00916-3

This article is cited by

-

Reshaping the tumor microenvironment of cold soft-tissue sarcomas with anti-angiogenics: a phase 2 trial of regorafenib combined with avelumab

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2025)