Abstract

Solar-driven interfacial water evaporation shows great potential to address the global water crisis, but its efficient implementation in the presence of organic wastewater remains challenging. Here, we achieved integrated water evaporation and organic compound degradation by designing a multifunctional MoS2 membrane. Under 1.0 sun irradiation, the membrane exhibits an evaporation rate of 2.07 kg m−2 h−1 and 82% degradation efficiency of organic pollutants, with negligible organic pollutant residues in the condensate. The high performance is attributed to the thermal energy generated by the evaporation process of MoS2 membrane. This promotes an increase in the rate constant of interfacial electron transfer during the photocatalytic reaction, accelerating the generation of free radicals and facilitating the removal of organic pollutants. The study demonstrated that fresh water can be collected from high-salinity wastewater at a rate of 1.56 kg m−2 h−1. The MoS2 membrane provides a sustainable approach to addressing the water crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Freshwater scarcity is a significant global issue, and the demand for potable water from unconventional sources, such as wastewater and seawater, is increasing1,2. Various water treatment strategies, including ion exchange3, distillation4, reverse osmosis5 and nanofiltration6, have been shown to be effective in producing freshwater. However, these methods have certain drawbacks, most notably high energy consumption and operating costs7. Therefore, there is an urgent need to use sustainable energy sources to increase water supplies through seawater desalination and wastewater treatment. Recently, solar-driven interfacial water evaporation technology has received much attention as a promising environmentally friendly water treatment technology8,9,10. By harnessing solar energy, the technology not only minimizes environmental impact, but also establishes a critical link between water and energy resources11.

To improve the photothermal conversion efficiency, solar evaporators are supposed to have efficient heat utilization12, optical enhancement13, and adequate water supply14,15. However, current solar water evaporation technologies face critical challenges, particularly the ingress of organic matter into the condensate and the accumulation of high salinity16. During the evaporation process, organic contaminants accumulate in the condensate, causing secondary contamination and requiring additional treatment steps13. Additionally, the rapid water evaporation process causes salt to accumulate or crystallize on the evaporator surface17, which reduces the evaporation rate. Another concern is the accumulation of organic pollutants in the water resource, resulting in a complex water treatment process18. Photocatalysis is another solar-driven interfacial process that can be naturally combined with photothermal processes to degrade organic pollutants13,19,20. Currently, a series of sustainable water purification processes integrating solar-driven water evaporation and photodegradation have been developed13,16,18,21,22,23, which are crucial for efficient freshwater production and pollution remediation24. However, the existing works are lacking in exploring the synergistic effect of light and heat generated during interfacial evaporation on photocatalytic activity.

Researchers have investigated several photothermal materials, such as carbon-based materials25,26,27, plasmonic metals28,29, semiconductors30,31, and polymers18,32 that have excellent photothermal conversion properties in the whole solar wavelength. Semiconductors, in particular, have received significant attention due to their excellent solar-to-vapor conversion efficiency, favorable chemical durability, and wide availability 33. In particular, metal sulfides are a notable class of semiconductors with narrow band gaps, which allows them to effectively convert a wide range of sunlight into thermal energy 34. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) has been widely used in photothermal evaporation and water purification due to its narrow band gap (1.89 eV) and broad absorption range35. Additionally, MoS2 is an environmentally friendly, chemically and photostable semiconductor photocatalyst that shows promise in pollutant degradation for water purification processes36. Various MoS2-based photothermal conversion materials have been developed by researchers to improve solar-to-vapor conversion efficiencies2,30. However, there is still a lack of research on the use of MoS2 for simultaneous water evaporation and water purification in wastewater containing organic pollutants.

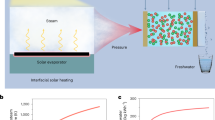

Herein, we present a multifunctional MoS2 membrane that has been fabricated on a carbon cloth substrate (MoS2/CF) using hydrothermal synthesis. The membrane enables integrated photothermal water evaporation and organic pollutant degradation. The solar evaporator consists of carbon fiber cloth (CF) as a water transport channel, MoS2 (MS) loaded on CF as a photothermal conversion membrane, and expandable polyethylene (EPE) foam as a thermal insulating layer (Fig. 1a). Specifically, the EPE foam insulates the photothermal evaporation interface and large volumes of water, solving the heat loss problem. Under 1.0 solar illumination, the membrane exhibited high interfacial energy localization and achieved an impressive water vapor generation rate of 2.07 kg m−2 h−1. In addition, the membrane contains numerous pores and is capable of generating thermal energy through solar-driven interfacial evaporation of MS/CF. This enhances water transport and light absorption, ultimately leading to an improvement in overall efficiency. The condensate had negligible residual organic compounds and the photocatalytic efficiency for organic pollutant degradation reached 82%. Molecular frontier orbital theory and Fukui function based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been used to investigate the reactive sites of RhB degradation. In addition, the study confirms the possibility of recovering freshwater from highly saline wastewater at a rate of 1.56 kg m−2 h−1, demonstrating the potential of MoS2/CF in addressing the challenge of water scarcity. This research has significant implications for water resource management and introduces a sustainable method for freshwater production.

Results and discussion

Fabrication of MS/CF membrane

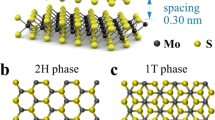

MoS2 (MS) nanosheets were synthesized on active CF using a solvothermal approach. The MS arrays were formed in a mixed solvent of water and N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), with Na2MoO4·2H2O as the Mo source and L-cysteine as the S source (Fig. 1b). As shown in the SEM images of MS/CF (Fig. 1c, d), the surface of CF was completely covered with a layer of MS nanosheet arrays, and some flower-like spheres were grown on the arrays. The MS nanosheets were interconnected by a large number of nanoscale gaps, which could facilitate vapor escape and water transportation. In addition, the abundance of pores also enhances the adsorption efficiency by reflecting incident light30. Furthermore, energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) analysis confirms the uniform distribution of S and Mo elements (see Supplementary Fig. 1). The crystalline structure of MS was further investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis. The XRD spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 2) of CF exhibited a clear broad diffraction peak at 25.6°, corresponding to the (002) crystal plane. The MS/CF sample exhibited three diffraction peaks at 2θ = 13.6°, 32.9° and 43.6°, corresponding to the (002), (100) and (006) crystal planes of the MS, respectively. Additionally, a low-angle diffraction peak at 2θ = 9.6° could be indexed to the (002) crystal plane of the MS, possibly due to a larger interlayer spacing37,38. HRTEM images (Fig. 1e, f) confirmed that the lattice spacing of 0.98 nm was consistent with the (002) crystal planes of MS, which corroborated the XRD results. The enlarged interlayer spacing can be attributed to the insertion of DMF and the lower growth temperature (200 °C)39,40,41.

Supplementary Fig. 2 presents the results of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) surface analysis, confirming the surface elemental composition and chemical states of Mo, S, C and O. The Mo 3d peaks can be divided into four peaks (Fig. 1g), with the peaks at 228.2 eV and 231.5 eV corresponding to Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2, respectively, which can be attributed to characteristic features of Mo4+ in MS. The peak at 234.8 eV is attributed to Mo 3d3/2 of Mo6+ and is related to typical Mo-O bonds42. A minor peak at 225.3 eV corresponds to S 2 s. In Fig. 1h, the binding energy of the S 2p spectrum at 161.2 eV and 162.4 eV is assigned to S2−, while the peaks at 167.4 eV and 168.7 eV are assigned to \({{\rm{SO}}}_{4^{-2}}\)43.

Water transport and thermal management of MS

Subsequently, the hydrophilicity of the MS/CF surface was investigated, and it was discovered that the loading of MS on pristine CF transformed the membrane from hydrophobic to superhydrophilic (Fig. 2a). Water diffused immediately upon contact with the membrane surface, mainly due to the interconnected porous structure of MS. This allows the MS/CF evaporator to maintain a sufficient water supply throughout the evaporation process. To evaluate the photothermal conversion performance of CF and MS/CF, the surface temperatures of the membranes were monitored under simulated solar irradiation of 1 kW m−2 (i.e., 1 sun). As shown in Fig. 2b, c, the surface temperatures of the membranes increased significantly under simulated solar irradiation, with the temperature differences before and after irradiation of MS/CF and CF being about 78.8 °C and 63.7 °C, respectively. The “hot and cold” cycling of the membranes reflected the photothermal stability, with the maximum surface temperature remaining relatively constant with changes in on/off times. To investigate the light absorption capabilities of the MS/CF and CF membranes, UV–Vis-NIR absorption spectra were measured (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 4). As clearly shown in Fig. 2d, MS/CF exhibits significantly enhanced light absorption in the 250–2500 nm range compared to pure CF. The light absorption of CF and MS/CF was calculated using Eq. (1)30:

where \(A\) is the light absorption, \(R\) is the reflection of the samples, \(T\) is the transmission of the samples, \(S\) is the solar irradiance, \(\lambda\) is the wavelength (nm). Therefore, the absorbance of the MS/CF in the range of 250 to 2500 nm was 91.51%, while the absorbance of the CF was only 81.82%. The calculation results show that MS/CF has good light absorption properties, which is of great importance for its photothermal conversion under solar irradiation. Overall, MS/CF achieved efficient light absorption, good hydrophilicity and heat management, which is a potential multifunctional solar evaporator.

Photothermal enabled solar evaporation and photodegradation

Conventional single-function solar-driven evaporators are not efficient in producing pure water due to the presence of numerous organic compounds in industrial wastewater. This is because the organic compounds evaporate and condense simultaneously with water vapor during the evaporation process. To evaluate the integrated evaporation and photodegradation performance of MS/CF, a Rhodamine B (RhB) solution was used as a representative dye contaminant (Supplementary Fig. 23). After 60 min in the dark, the concentration of RhB decreased by about 20% due to the adsorption capacity of the MS/CF membrane (Supplementary Fig. 5). Subsequently, the removal performance of the well-designed catalytic/photothermal integrated solar evaporation system for organic pollutants was investigated under simulated sunlight (1 sun, 1 kW m−2). As depicted in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 6, RhB was degraded by 82% within 60 min with MS/CF under solar irradiation, while the degradation rate for pure CF was only 11%. The degradation rate constant of RhB by MS/CF (0.032 min−1) was 16 times higher than that of CF (0.002 min−1) (Fig. 3b), indicating the excellent photodegradation performance of MS/CF.

a The RhB degradation curves and b the kinetic curves over the different systems. c Time-dependent mass changes and d evaporation rates under 1 sun illumination. e Temperature changes of pure RhB, CF and MS/CF under 1 sun irradiation for 60 min. f Simulation of the thermal distribution of the system under 1 sun illumination.

Simultaneously, tests were conducted to evaluate the water evaporation performance of MS/CF under 1 sun illumination. The weight changes of the system were recorded using an electronic balance, and the evaporation rate was calculated from the results, as shown in Fig. 3c, d. A control using pure RhB solution evaporation showed a significantly lower evaporation rate. The results demonstrate that the use of MS/CF evaporator resulted in a significantly higher evaporation rate. The evaporation rate of MS/CF was calculated to be 2.07 kg m−2 h−1 and the solar evaporation efficiency was calculated to be 88.7% (Supplementary Note 4) under 1 sun irradiation. To further investigate the energy transfer processes during the evaporation process, an infrared camera was used to monitor the temperature changes on the surface of the evaporation system, as shown in Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 7. The surface temperature of MS/CF was about 59.9 °C, which was about 3.1 °C higher than that of pure CF. The MS/CF membrane was supported by foam floating on top of the beaker and filled with water (simulated method and modeling geometry as shown in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 8). The overall simulation results (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 9) were in good agreement with experimental observations, indicating that MS/CF efficiently localized the heat near the evaporation surface, thereby achieving high-efficiency solar-vapor generation. Simulation of the temperature distribution throughout the device showed that the MS/CF evaporation system effectively managed thermal energy. Due to the light absorption of MS/CF and the insulation of the foam, most of the energy was concentrated on the surface of the membrane, preventing heat loss. Good thermal localization under 1 sun irradiation verified its feasibility for solar water evaporation.

In addition, it can be seen from Fig. 4a, b that the evaporator maintained good evaporation performance even under 0.5 sun irradiation, indicating that the MS/CF evaporator has utility in real environments. As the light intensity increased to 3 suns, the evaporation rate significantly improved. The differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Supplementary Note 3) curves in Fig. 4c indicate that the signal value for MS/CF was lower than that of pure water. It was also observed that the trend of the heat flow signal of MS/CF gradually slowed down with increasing temperature, and the peak was much broader than that of pure water, indicating that the evaporation of water in MS/CF was different from that in bulk water. Moreover, the equivalent evaporation enthalpy44 of MS was further calculated using the evaporation data under dark conditions, which showed that the equivalent evaporation enthalpy of MS/CF (2.11 kJ g−1, Supplementary Fig. 10) was much lower than that of pure water (2.44 kJ g−1). This indicates that MS/CF has excellent evaporation performance due to the reduced evaporation enthalpy of water in MS/CF, which effectively lowers the energy required for water evaporation. The reason for the reduction in vaporization enthalpy can be explained by the water cluster theory 2. Water can be evaporated as either a single molecule or in small clusters consisting of a few to tens of molecules. When water molecules are confined in the molecular mesh, they are more likely to escape as small clusters rather than individual molecules. As such, the water is evaporated to a state with a lower enthalpy change than conventional latent heat. In addition, the influence of RhB concentration on the photodegradation and evaporation performance was investigated (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). Furthermore, the MS/CF evaporator exhibits degradation effects on different types of organic pollutants, demonstrating its versatility in pollutant degradation (Supplementary Fig. 13). Subsequently, it was further verified that MS/CF has excellent evaporation performance even for different types of organic pollutants (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). From Supplementary Fig. 24, the MS/CF membrane exhibited a degradation rate of 85% with 120 min and an evaporation rate reaching 1.4 kg m−2 h−1 under natural sunlight irradiation.

a Mass change and b evaporation rate of MS/CF evaporator under different sunlight illumination. c DSC curves of MS/CF and pure water. d The RhB degradation curves and e the kinetic curves under different light intensities. f Cycles of water evaporation rates and degradation kinetics in MS/CF evaporators under different light intensities. g Effect of scavengers on the removal efficiency of RhB. ESR spectra of h DMPO-‧O2− and i ‧OH.

The impact of light intensity on the degradation of RhB is evident from Fig. 4d, e. This can be attributed to the increase in temperature at the air-water interface with increasing light intensity, which enhances the thermodynamic driving force for interfacial carrier transfer and improves the catalytic degradation performance14. Control experiments were conducted to verify the effect of temperature and light on the RhB photodegradation process (Supplementary Fig. 16). The results showed that the degradation of RhB was facilitated under light irradiation compared to RhB at room temperature in the absence of light. In addition, it was observed that as the reaction temperature increased from 25 °C to 60 °C in the presence of the light source, the rate constant for RhB degradation significantly increased from 0.019 min−1 to 0.032 min−1. This phenomenon demonstrates that the thermal energy generated by solar-driven interfacial evaporation facilitates the removal of RhB. In general, the effect of photothermal on photodegradation activity depends on both kinetics and thermodynamics14. The influence of temperature on the photocatalytic activity can be illustrated by Eq. (2)45.

Where \({k}_{{IT}}\) and \(Q\) are the interfacial transfer rate constant and the apparent activation energy of interfacial transfer, respectively, \({v}_{0}\) and \(k\) are the finger-forward factor Boltzmann’s constant, respectively, and \(T\) is the thermal temperature. The elevated temperature in solar evaporation process promotes an increase in the rate constant of interfacial electron transfer during the photocatalytic reaction, which accelerates the generation of free radicals during the degradation process46. Therefore, the MS/CF evaporator enhances photocatalytic activity through interfacial photothermal effects. This is achieved by increasing the light intensity, which in turn raises the temperature at the air-water interface. The higher temperature enhances the thermodynamic driving force for interfacial carrier transfer, thereby improving catalytic degradation performance. Control experiments show that the thermal energy generated by solar-driven interfacial evaporation facilitates the removal of organic pollutants. Additionally, the effect of temperature on photocatalytic activity is characterized by an increase in the rate constant of interfacial electron transfer, accelerating the generation of free radicals essential for degradation. Figure 4f and Supplementary Fig. 17 further confirm the excellent cycling stability of the MS/CF system.

To fully identify the major active species involved in the photodegradation of RhB, radical quenching experiments were performed by adding scavengers. Isopropanol (IPA), p-benzoquinone (BQ), and triethanolamine (TEOA) were employed as scavengers for ‧OH, ‧O2− and h+, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 18, the photodegradation efficiencies and reaction rate constants were significantly decreased after the addition of TEOA and BQ, indicating that h+ and ‧O2− were the main active species. Furthermore, the addition of IPA exhibited a slight inhibitory effect, indicating that the involvement of ·OH in the RhB degradation process played an assisted role. To further identify the possible active species of the system, electron spin resonance (ESR) analysis was performed under 1 kW m−2 illumination. As shown in Fig. 4h, i, no obvious ESR signals were observed under dark conditions, but characteristic peak signals were captured after light illumination. All these results supported the radical scavenging experiments.

The reactive sites of organic molecules are crucial for a comprehensive analysis of photodegradation processes, so molecular frontier orbital theory and Fukui function based on DFT calculations (Supplementary Note 2) were used to predict the reactive sites of RhB. The molecular structure of RhB and the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the optimized RhB are shown in Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20, respectively. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 20a, the HOMO orbital of RhB was mainly concentrated on the benzene ring, N43 and N44 atoms, while the LUMO orbitals were mainly concentrated on the benzene ring, O59 and C62. However, frontier molecular orbitals do not accurately predict the site of radical attack, so Hirshfeld charges and Fukui functions were investigated. In the analysis of the modes of attack on the RhB molecule, f −, f + and f 0 were used to denote electrophilic attack, nucleophilic attack and free radical attack, respectively. It was found that the maximum values of the f 0 function were located at N43 and N44 (Supplementary Fig. 20e), indicating that these sites are the most active sites for free radical attack. Typically, the atoms with the most positive and negative values of CDD are most susceptible to nucleophilic and electrophilic substances, respectively47. From Supplementary Fig. 20f and Supplementary Fig. 21, it was clear that C62 was nucleophilic, while N43 and N44 exhibited electrophilicity. Therefore, N43 and N44 in RhB were highly susceptible to free radical attack in the system. Overall, this bifunctional evaporation system is capable of effectively degrading organic pollutants and simultaneously producing clean water during water evaporation. Therefore, a mechanism for efficient and continuous solar-driven interfacial evaporation of MS/CF can be included as follows: (1) The efficient photothermal conversion was enhanced by loading MS onto CF, resulting in high interfacial energy localization and achieved an impressive water vapor generation rate. (2) The MS nanosheets were interconnected by a large number of nanoscale gaps, which could facilitate vapor escape and water transport. (3) The foam’s low thermal conductivity concentrates most of the energy on the surface of the MS/CF, preventing heat loss. (4) Compared to pure water, MS/CF has a lower evaporation enthalpy, which reduces the energy required for water evaporation. (5) The higher temperature in solar evaporation process of MS/CF promotes an increase in the rate constant of interfacial electron transfer during the photocatalytic reaction, which accelerates the generation of free radicals during the RhB degradation process.

Solar water purification performance of the MS/CF

Subsequently, the water treatment capability of the MS/CF evaporator was further evaluated by collecting condensed water during the solar-driven interfacial evaporation simultaneous photodegradation process. As shown in Fig. 5a, no obvious absorption peaks corresponding to RhB were detected in the condensate, indicating that MS/CF has excellent water purification performance. In addition, the feasibility of using the MS/CF evaporation system for the desalination of high-salinity wastewater was evaluated. The experimental data showed that the evaporation rates of the prepared evaporator were −1.98, −1.87, −1.71, and −1.59 kg m−2 h−1 at salt concentrations of 0.8, 4, 10, and 20 wt%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 22). The reason for the gradual decrease in evaporation rate with increasing salinity is the decrease in saturated vapor pressure at high salinity. Impressively, the evaporator system was also able to achieve an evaporation rate of 1.56 kg m−2 h−1 for saturated brine (25% salinity) (Fig. 5b). The evaporation performance of the MS/CF remains stable even in high salinity solutions. In summary, the condensate collection and high salinity wastewater treatment experiments effectively verified the feasibility and effectiveness of MS/CF, while achieving organic degradation and freshwater collection.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a multifunctional integrated system (MS/CF) was rationally designed to simultaneously facilitate solar-driven water evaporation and water purification. The MS/CF evaporator system exhibited high solar absorption, making it an efficient platform for light-to-heat conversion. The unique structural features of the evaporator were found to be advantageous in terms of enhancing thermal localization and promoting the degradation of organic compounds. Experimental results demonstrated a water evaporation rate of 2.07 kg m−2 h−1 under 1 sun irradiation, while the evaporation rate for saturated brine water reached 1.56 kg m−2 h−1. Meanwhile, the MS/CF evaporator enhanced photocatalytic activity through the synergistic effect of interfacial light and heat. This study not only provides the potential for efficient and sustainable solar-driven water evaporation, but also highlights the integrated water purification capabilities of the MS/CF evaporator system.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade without further purification. Sodium molybdate dihydrate (Na2MoO4·2H2O), L-cysteine and N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Aladdin Co., China. Carbon fiber cloth (CF, WOS1009) was supplied by CeTech.

Synthesis of MS/CF evaporator

The CF was first cut to the desired size and then cleaned ultrasonically with acetone, ethanol and deionized water. The MS/CF composites were prepared using a hydrothermal method. In a typical synthesis, a solution containing Na2MoO4·2H2O (0.3 g), L-cysteine (0.6 g), DMF (36 mL) and deionized water (24 mL) was prepared, the CF was immersed in the solution and grown at 200 °C for 12 h, and cooled to room temperature. The sample was washed with deionized water and ethanol, and finally dried at 60 °C under vacuum overnight.

Due to its flexibility and strength, CF can be easily bent. To transport enough water to the evaporator surface, place the CF on an EPE foam with a diameter of 2 cm and dip its four legs into the solution below, taking advantage of the strong capillary force of the CF. Subsequently, carry out the evaporation performance test.

Characterization

The compositions of the samples were recorded using X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Rigaku diffractometer. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S4800, Hitachi) and transmission electron microscope (TEM, Tecnai G2 F30 S-TWIN) with energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) were used to observe the microstructure of the products. The sunlight absorption spectra of the membrane were characterized using a UV–Vis–NIR spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) equipped with an integrating sphere. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed using a Thermo ESCALAB 250XI spectrometer. The contact angle of water was measured with a contact angle meter (JY-82B Kruss DSA). The evaporation enthalpy of water in the film was calculated based on differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) data obtained with a NETZSCH DSC 200F3 in a nitrogen environment. The vapor generation of the system was simulated by irradiating the beaker by a xenon lamp (CEL-HXF300) with a standard AM 1.5 G optical filter. The light intensity was calibrated by a CEL-NP2000-2(10)A optical power meter. An infrared camera (FLIR E6xt) was used to measure the temperature distribution and changes on the film surface.

Measurement of water evaporation performance

The solar evaporation simulation experiment was performed under laboratory conditions. RhB solution (5 mg L−1) and different concentrations of saline solution were treated. Prior to testing, the membrane was fully wetted in the dark to achieve adsorption-desorption equilibrium. An electronic balance (0.01 g) was used to monitor and record weight changes in real time. The surface temperature of the system was recorded using an infrared camera.

Measurement of water purification performance

During photothermal evaporation in situ water purification, RhB was selected as the model pollutant and tested in a beaker under laboratory conditions (Supplementary Fig. 22). During the duration, a xenon lamp was used as the light source and the light intensity was adjusted with an optical power meter. Before illumination, the system was placed in the dark for a period of time until adsorption-desorption equilibrium was reached. 2 mL of the mixture was taken every 10 min to analyze residual RhB concentration. The concentration of RhB in collected solution was determined using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer at 553 nm.

Clean condensed water production

The RhB solution was introduced into a lab-made evaporation device. The device was then placed in a sealed quartz reactor and clean condensed water was collected through the MS/CF evaporator. After 1 h of irradiation of the MS/CF evaporator, condensed water was collected from the side of the quartz reactor. Finally, the concentration of MS in the collected condensed water was characterized using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer at 553 nm.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files. They are also available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, Z. et al. MXene-reduced graphene oxide sponge-based solar evaporators with integrated water-thermal management by anisotropic design. Commun. Mater. 4, 70 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Reclaimable MoS2 sponge absorbent for drinking water purification driven by solar energy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11718–11728 (2022).

Fonseca, A. D., Crespo, J. G., Almeida, J. S. & Reis, M. A. Drinking water denitrification using a novel ion-exchange membrane bioreactor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 1557–1562 (2000).

Borsani, R. & Rebagliati, S. Fundamentals and costing of MSF desalination plants and comparison with other technologies. Desalination 182, 29–37 (2005).

Atia, A. A., Allen, J., Young, E., Knueven, B. & Bartholomew, T. Cost optimization of low-salt-rejection reverse osmosis. Desalination 551, 116407 (2023).

Yu, D. et al. Recent advances in stimuli‐responsive smart membranes for nanofiltration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2211983 (2023).

Khawaji, A. D., Kutubkhanah, I. K. & Wie, J.-M. Advances in seawater desalination technologies. Desalination 221, 47–69 (2008).

Cui, L. et al. Rationally constructing a 3D bifunctional solar evaporator for high-performance water evaporation coupled with pollutants degradation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 337, 122988, (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhancing solar steam generation using a highly thermally conductive evaporator support. Sci. Bull. 66, 2479–2488 (2021).

Zhu, L., Gao, M., Peh, C. K. N. & Ho, G. W. Recent progress in solar-driven interfacial water evaporation: Advanced designs and applications. Nano Energy 57, 507–518 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. All-cold evaporation under one sun with zero energy loss by using a heatsink inspired solar evaporator. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002501 (2021).

Zhou, L. et al. 3D self-assembly of aluminium nanoparticles for plasmon-enhanced solar desalination. Nat. Photonics 10, 393–398 (2016).

Ma, J. X. et al. A light-permeable solar evaporator with three-dimensional photocatalytic sites to boost volatile-organic-compound rejection for water purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9797–9805 (2022).

Xia, Q. et al. A floating integrated solar micro‐evaporator for self‐cleaning desalination and organic degradation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214769 (2023).

Zhu, L., Gao, M., Peh, C. K. N., Wang, X. & Ho, G. W. Self‐contained monolithic carbon sponges for solar‐driven interfacial water evaporation distillation and electricity generation. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702149 (2018).

Cui, L. et al. Environmental energy enhanced solar-driven evaporator with spontaneous internal convection for highly efficient water purification. Water Res. 244, 120514 (2023).

Zhao, F., Guo, Y., Zhou, X., Shi, W. & Yu, G. Materials for solar-powered water evaporation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 388–401 (2020).

Zhang, B. P., Wong, P. W. & An, A. K. Photothermally enabled MXene hydrogel membrane with integrated solar-driven evaporation and photodegradation for efficient water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 133054 (2022).

Wu, Y., Che, H., Liu, B. & Ao, Y. Promising materials for photocatalysis‐self‐Fenton system: properties, modifications, and applications. Small Structures, 4, 2200371 (2023).

Yan, S. W. et al. Integrated reduced graphene oxide/polypyrrole hybrid aerogels for simultaneous photocatalytic decontamination and water evaporation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 301, 120820 (2022).

Song, C. et al. Volatile-organic-compound-intercepting solar distillation enabled by a photothermal/photocatalytic nanofibrous membrane with dual-scale pores. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 9025–9033 (2020).

Mo, H. & Wang, Y. A bionic solar-driven interfacial evaporation system with a photothermal-photocatalytic hydrogel for VOC removal during solar distillation. Water Res 226, 119276 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Omnidirectionally irradiated three-dimensional molybdenum disulfide decorated hydrothermal pinecone evaporator for solar-thermal evaporation and photocatalytic degradation of wastewaters. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 637, 477–488 (2023).

Cui, L. et al. Co nanoparticles modified N-doped carbon nanosheets array as a novel bifunctional photothermal membrane for simultaneous solar-driven interfacial water evaporation and persulfate mediating water purification. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 330, 122556 (2023).

Ghasemi, H. et al. Solar steam generation by heat localization. Nat. Commun. 5, 4449 (2014).

Li, J. L. et al. Over 10 kg m−2 h−1 evaporation rate enabled by a 3D interconnected porous carbon foam. Joule 4, 928–937 (2020).

Xue, G. et al. Water-evaporation-induced electricity with nanostructured carbon materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 317–321 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Yu, B., Yin, K. & Zhang, Z. Hierarchically structured black gold film with ultrahigh porosity for solar steam generation. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200108 (2022).

Saad, A. G., Gebreil, A., Kospa, D. A., El-Hakam, S. & Ibrahim, A. A. Integrated solar seawater desalination and power generation via plasmonic sawdust-derived biochar: Waste to wealth. Desalination 535, 115824 (2022).

Liu, P. et al. Enhanced solar evaporation using a scalable MoS2‐based hydrogel for highly efficient solar desalination. Angew. Chem. 134, e202208587 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. Atomic-scale engineering of cation vacancies in two-dimensional unilamellar metal oxide nanosheets for electricity generation from water evaporation. Nano Energy 110, 108348 (2023).

Zhao, F. et al. Highly efficient solar vapour generation via hierarchically nanostructured gels. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 489–495 (2018).

Ibrahim, I., Seo, D. H., McDonagh, A. M., Shon, H. K. & Tijing, L. Semiconductor photothermal materials enabling efficient solar steam generation toward desalination and wastewater treatment. Desalination 500, 114853 (2021).

Liu, P. et al. Recent progress in interfacial photo-vapor conversion technology using metal sulfide-based semiconductor materials. Desalination 527, 115532 (2022).

Xiao, J. et al. A scalable, cost-effective and salt-rejecting MoS2/SA@melamine foam for continuous solar steam generation. Nano Energy 87, 106213 (2021).

Khan, B. et al. Electronic and nanostructure engineering of bifunctional MoS2 towards exceptional visible-light photocatalytic CO2 reduction and pollutant degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 381, 120972 (2020).

Lu, Q., Shi, W., Yang, H. & Wang, X. Nanoconfined water-molecule channels for high-yield solar vapor generation under weaker sunlight. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001544 (2020).

Guo, Z. et al. PEGylated self-growth MoS2 on a cotton cloth substrate for high-efficiency solar energy utilization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 24583–24589 (2018).

Xie, J. et al. Controllable disorder engineering in oxygen-incorporated MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets for efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17881–17888 (2013).

Wu, M. et al. Metallic 1T MoS2 nanosheet arrays vertically grown on activated carbon fiber cloth for enhanced Li-ion storage performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 14061–14069 (2017).

Rasamani, K. D., Alimohammadi, F. & Sun, Y. Interlayer-expanded MoS2. Mater. Today 20, 83–91 (2017).

Teng, Y. et al. MoS2 nanosheets vertically grown on graphene sheets for lithium-ion battery anodes. ACS Nano 10, 8526–8535 (2016).

Wang, X., Chen, Y., Li, T., Liang, J. & Zhou, L. High-efficient elimination of roxarsone by MoS2@Schwertmannite via heterogeneous photo-Fenton oxidation and simultaneous arsenic immobilization. Chem. Eng. J. 405, 126952 (2021).

Shen, H., Zheng, Z., Liu, H. & Wang, X. A solar-powered interfacial evaporation system based on MoS2-decorated magnetic phase-change microcapsules for sustainable seawater desalination. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 25509–25526 (2022).

Meng, F. et al. Temperature dependent photocatalysis of g-C3N4, TiO2 and ZnO: Differences in photoactive mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 532, 321–330 (2018).

Ramírez-Sánchez, I. M., Tuberty, S., Hambourger, M. & Bandala, E. R. Resource efficiency analysis for photocatalytic degradation and mineralization of estriol using TiO2 nanoparticles. Chemosphere 184, 1270–1285 (2017).

Gao, X., Chen, J., Che, H. N., Ao, Y. H. & Wang, P. F. Rationally constructing of a novel composite photocatalyst with multi charge transfer channels for highly efficient sulfamethoxazole elimination: Mechanism, degradation pathway and DFT calculation. Chem. Eng. J. 426, 131585 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3202402), Natural Science Foundation of China (52100179), and PAPD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lingfang Cui and Yanhui Ao designed the whole experiments. Huinan Che contributed to the theoretical calculations. Lingfang Cui wrote the manuscript. Yanhui Ao and Bin Liu provided constructive suggestions and improved the paper quality by discussions. All authors analyzed the experimental results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Xiaodong Wang and Xianbao Wang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, L., Che, H., Liu, B. et al. Multifunctional MoS2 membrane for integrated solar-driven water evaporation and water purification. Commun Mater 5, 94 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00532-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00532-1