Abstract

With extraordinarily high efficiency, low cost, and excellent stability, 2D perovskite has demonstrated a great potential to revolutionize photovoltaics technology. However, inefficient material structure representations have significantly hindered artificial intelligence (AI)-based perovskite design and discovery. Here we propose geometric data analysis (GDA)-based perovskite structure representation and featurization and combine them with learning models for 2D perovskite design. Both geometric properties and periodicity information of the material unit cell, are fully characterized by a series of 1D functions, i.e., density fingerprints (DFs), which are mathematically guaranteed to be invariant under different unit cell representations and stable to structure perturbations. Element-specific DFs, which are based on different site combinations and atom types, are combined with gradient boosting tree (GBT) model. It has been found that our GDA-based learning models can outperform all existing models, as far as we know, on the widely used new materials for solar energetics (NMSE) databank.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Materials innovation and design present a multifaceted approach to tackle humanity’s challenges of sustainable development and climate change1,2,3,4. Recently, halide perovskites have been widely recognized as a remarkable semiconductor material for optoelectronics. Within a decade, halide perovskites have demonstrated great potential to disrupt the photovoltaics and light emitting devices (LEDs) industries5,6,7. Power conversion efficiencies exceeding 26% have been achieved by single-junction perovskite solar cells and even higher efficiency of 33% have been reported for silicon-based tandem perovskite solar cells8,9, while external quantum efficiencies exceeding 23% have been demonstrated for perovskite LEDs7. Of late, two-dimensional (2D) perovskites with their huge structural diversity are emerging candidates for the next-generation perovskite materials (a.k.a. Perovskite 2.0)5,6,10,11,12,13,14,15. These layered materials afford even higher stability and greater tunability of their optoelectronic properties than their three-dimensional (3D) counterparts. However, the discovery and design of new materials is a complicated and challenging process. In fact, materials even with very simple elements can easily end up in a formidably huge chemical space, making the traditional trial-and-error-based materials discovery not only time-consuming but also extremely expensive16.

Recently, data-driven materials informatics manifests its huge potential in materials design and discovery17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Materials informatics17,18,19,20, which is the integration of computational materials science with machine learning (ML) technologies, is the fourth paradigm for material science35. A major milestone of artificial intelligence (AI)-based materials informatics is the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI)3, which was launched in 2011 in the United States with the goals of establishing large-scale collaboration between materials scientists and computer scientists and applying machine learning models to predict, screen, and optimize materials at an unparalleled scale and rate. MGI has promoted the creation of various databanks, such as Materials Project36, JARVIS37, NOMAD38, Aflowlib39, OQMD40, etc. Together with other well-established materials databanks, they provide a solid foundation for data-driven AI models for materials functional prediction and new material design and discovery. Currently, AI models have been widely used in the analysis of various perovskite data, including single perovskites21,41,42,43,44,45, double perovskites46,47,48,49, Pb-free perovskites50,51,52,53, and perovskite solar cell devices54,55,56,57,58.

Mathematically, data-driven material AI models can be classified into two categories, i.e., featurization-based machine learning models and end-to-end deep learning models. Featurization or feature engineering seeks to develop a set of structural, physical, chemical, or biological features that characterize the material intrinsic information28,59,60,61. These features are known as molecular descriptors or fingerprints. Traditional molecular descriptors for materials include atomic radius, ionic radius, orbital radius, tolerance factor, octahedral factor, packing factor, crystal structure measurements, surface/volume features, and physical properties such as ionization potential, ionic polarizability, electron affinity, Pauling electronegativity, valence orbital radii, and HOMO and LUMO, etc. The molecular fingerprint is a long vector composed of a series of systematically generated features, usually from molecular structures. The widely-used material molecular fingerprints include Coulomb matrix29, and Ewald sum matrices62, many-body tensor representation (MBTR)63, smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP)64, and atom-centered symmetry functions (ACSF)65, etc. These molecular descriptors or fingerprints are used as input features for machine learning models and have been applied in various material property predictions, in particular, 2D perovskite bandgap prediction66,67.

Deep learning models, in particular, geometric deep learning models, are free from hand-craft features and provide an end-to-end way to directly learn the materials’ properties. Geometric deep learning is proposed for the analysis of non-Euclidean data, such as graphs, networks, manifolds, etc, by the incorporation of data geometric and topological information into deep learning architectures68,69,70,71. Among the geometric deep learning models are graph neural networks (GNNs), which have been widely used in node classification, link prediction, graph classification, and property prediction72,73,74,75. Recently, various GNN models have been developed for material property analysis, such as SchNet45, crystal graph convolutional neural networks (CGCNN)21, materials graph network (MEGNet)22, improved crystal graph convolutional neural networks (iCGCNN)76, global attention-based graph neural network (GATGNN)77, crystal graph attention network (CYATT)24, compositionally restricted attention-based network (CrabNet)25, neural equivariant interatomic potentials (NequIP)26, atomistic line graph neural network (ALIGNN)78, Matformer79, MatDeepLearn27, and SIGNNA80. In general, materials-based GNN models can be mainly classified into two categories: potential-energy-based GNNs and chemical-composition-based GNNs. The potential-energy-based GNNs, which include SchNet45, MEGNet22, and NequIP26, use specially-designed GNN architecture to approximate potential energy and use it to predict material properties. The chemical-composition-based GNNs, including CYATT24 and CrabNet25, construct deep learning architectures directly on chemical formulas or chemical structures.

Despite the rapid progress in material AI models, efficient representation, and characterization of materials structures; in particular, the material periodic information still remains a major challenge32,33,34. Recently, topological data analysis (TDA) has been used in the characterization of molecular structures81,82. Different from traditional models, advanced intrinsic mathematical invariants from algebraic topology are used as molecular fingerprints in TDA models81,82. TDA-based learning models have proven their advantages in various steps of drug design81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88, and materials design and discovery89,90,91,92,93. Motivated by the success of TDA, geometric data analysis (GDA) has been developed to study the intrinsic geometric properties of data, including discrete curvatures94,95,96,97,98, flows99, and periodicity79,100,101. Persistent Ricci curvature-based learning models have demonstrated a great advantage over traditional descriptors for perovskite data analysis102. More recently, a density fingerprint (DF) model has been proposed to explicitly characterize crystal periodicity information100. The key idea of DF is to characterize the geometric distribution of atoms within a unit cell by the intersection patterns of the neighboring atoms during a filtration process. The DF approach is found to preserve the essential intrinsic structure information and remains invariant to isometries, continuity, and completeness.

Hitherto, to the best of our knowledge, the GDA-based machine learning model for 2D perovskite design is unprecedented. To fully characterize 2D perovskite structural information, we consider an element-specific representation, which is to decompose the perovskite unit cell into a series of element-specific sets. Each set is composed of one or several types of atoms depending on sites, inorganic/organic properties, and halide anion types. The geometric and periodicity information of these element-specific structures is characterized by a series of density functions, i.e., density fingerprint. The GDA-based material fingerprint is obtained by the concatenation of all the corresponding density fingerprints and then is combined with machine learning models, in particular, gradient boosting tree (GBT). Our GDA-GBT model is extensively validated and compared with state-of-the-art models in the 2D perovskite dataset sourced from the new materials for solar energetics (NMSE) databank. To the best of our knowledge, our GDA-GBT model outperforms all the existing models.

Results and discussion

GDA-based material fingerprint

Density fingerprint, which is a series of 1D density functions of different dimensions, is a powerful tool that captures the periodic geometric information of crystals100. They characterize the pattern of neighboring atom spheres overlapping with one another during a filtration process100. More specifically, in the filtration process, each atom is represented as a sphere, denoted as S(t), and their radius (t) is consistently increasing. The overlapping regions in at least k spheres are denoted as ⋃kS(t), with ⋃0S(t) denoting the entire region and ⋃1S(t) denoting the region occupied by at least one sphere. Note that if a certain overlapping region is from k + 1 spheres, then it must be an overlapping region from k spheres, i.e., ⋃k+1S(t) ⊂ ⋃kS(t). The overlapping region of exactly k spheres is defined as ⋃kS(t) − ⋃k+1S(t). In general, the k-th density function is the ratio between the volume of the exact k-sphere overlapping region (within the unit cell) and the volume of the unit cell over a filtration process. Figure 1 shows the overlapping regions (within the unit cell) (a), the exact overlapping regions (within the unit cell) (b), and the 1D density functions (of dimensions 0 to 2) (c). Here the unit cell is a cube structure composed of 8 atoms of the same type. Details for the construction of DF on a 2D perovskite are presented in the Method section.

In this example, the unit cell U is the set \({\left[0,1\right)}^{3}\) with the atoms centered at the vertices, and S(t) are atom spheres with radius t. Panel a: The overlapping region of k spheres (within the unit cell) is denoted as U ∩ ⋃kS(t) (k = 0, 1, 2, 3); Panel b: The overlapping region of exactly k spheres (within the unit cell) is \(U\cap ({\bigcup }^{k}S(t)-{\bigcup }^{k+1}S(t))\) (k = 0, 1, 2); Panel c: The corresponding density functions ψ0, ψ1, ψ2 on the interval [0, 1].

Element-specific DFs can provide a more detailed characterization of material intrinsic structural information. Mathematically, the essential idea of element-specific representation is to systematically select a set of atoms or site combinations to characterize the heterogenous interactions within the molecular structure81,82. For instance, it has been found that the selection of carbon atoms characterizes the hydrophobic interaction network whilst the selection of all nitrogen and/or oxygen atoms characterizes the hydrophilic interaction network81. In our GDA model, we concatenate the DFs calculated from a series of atom sets systematically obtained from sites and their combinations (ACB, ACX, ACBX, BX, B, X), A-site atom types (C, H, O, N), B-site atom types (Bi, Cd, Ge, Pb, \({{{{{{{\rm{Sn}}}}}}}}\)), and X-site atom types, i.e., halide anions (Cl, Br, I). Note that the B-site and X-site encompass all inorganic and halide atoms for each material, and we apply carbon (C atoms) ions as a representative of the A-site (the site of organic cations) for reducing the computational complexity.

GDA-based ML for 2D perovskite design

Database

Unlike three-dimensional (3D) perovskites, there is a scarcity of databases that provide information on 2D perovskites. In 2021, the Laboratory of New Materials for Solar Energetics (NMSE) launched a crowd-sourcing project to collect 2D perovskites from a variety of experiments and literature sources66. This open-access database contains crystal structures with atomic coordinates and offers density function theory (DFT)-based and experiment (Exp)-based bandgaps (with unit eV) as well as ML-based atomic partial charges. It is currently the most comprehensive database available for studying 2D perovskite crystallines and is continuously updated by the NMSE. The current database accommodates 849 compounds, all possessing 3D structures. Within this collection, 753 compounds are equipped with DFT-based bandgap values (eV), while 238 compounds possess experimental bandgap values. It is worth noting that 235 materials exhibit both types of bandgaps. In this study, diverse experimental scenarios encompass the utilization of subsets from the pool of 753 and 238 2D perovskites.

GDA-based ML for 2D perovskite bandgap prediction

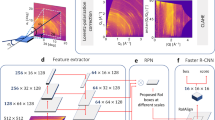

Figure 2 shows a flowchart of our DF-based ML for 2D perovskite material design. Our approach involves several key steps. First, different types of atoms and their combinations within the unit cell, such as organic atoms (e.g., C), inorganic atoms (e.g., \({{{{{{{\rm{Sn}}}}}}}}\)), halide atoms (e.g., Cl), and site combinations (e.g., ACB and ACBX), are systematically extracted from the dataset. Then, we create a multiscale topological representation of the selected atomic system through a filtration process (i.e., a consistent increase of atom radius). Based on the topological representation, we employ the DF algorithm to generate a set of 1D density functions, namely ψ0, ψ1, …ψn, which are referred to as element-specific density fingerprints (see Method for more details). Finally, leveraging the extracted density fingerprints, we employ the gradient boost tree (GBT) model to predict the material bandgaps. One benefit of the GBT model is its great accuracy and robustness103,104,105. Additionally, GBT offers the advantage of providing feature component importance, enabling a more interpretable and explanatory analysis of the relationship between input features and the prediction target.

In this work, we atom-wise compute the density fingerprint of a given material structure. The second slot of the flowchart illustrates the balls centered at the iodine atoms of the material with different radii. The 2D perovskite structures are represented as vectors of density fingerprint curves (ψn, n = 0, 1, 2, …), which serve as features for the machine learning models. In this work, a gradient boosting tree (GBT) model is applied to the DF-based features to predict material bandgaps. Perovskite structures were visualized using the VESTA software120.

We utilize standard statistical scores to evaluate our GDA-GBT models. Four indices are used for error estimation: the coefficient of determination (COD), Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), mean absolute error (MAE), and root-mean-square error (RMSE), where COD and MAE are major targets considered in the present literature66,67,80. To ensure a reliable comparison, we apply the 5-fold cross-validation to each experiment and record the average scores. Results and comparisons are shown in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, our GDA-GBT model exhibits superior performance compared to most other models, highlighted by a COD of 0.9101 and an MAE of 0.0695 (eV). Furthermore, our GBT model, utilizing importance-based DF features (GDA(IF)-GBT), achieves even more remarkable results, as evidenced by a COD of 0.9157 and an MAE of 0.0681 (eV). Further comparison and analysis are given in the following section and Supplementary Notes 1–3.

Extensive comparison with state-of-the-art models

We carried out an extensive comparison of our GDA-GBT model with the state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on 2D perovskite bandgap prediction, including smooth overlap of atomic position (SOAP) kernel-based ML models (SOAP-based KRR67 and MLM166) and GNN models, such as GCN75, ECCN76, CGCNN21, TFGNN106, SIGNNA80, and SIGNNAc80. In particular, SIGNNAc is an enhanced version of SIGNNA that incorporates additional chemical information and machine-learning feature vectors within the SIGNNA architecture80. In comparison to SIGNNA, SIGNNAc achieves improved results with a COD of 0.9270 and MAE of 0.0830 (eV). Table 1 provides a comprehensive performance comparison. It is important to highlight that all the models underwent evaluation using a 5-fold cross-validation analysis. Notably, given the extensive size of the current NMSE database, which comprises over 624 materials with DFT-based bandgap values, we conducted five random subsamples, each with 624 materials, and applied the same 5-fold cross-validation procedure in each case. The reported results represent the average scores achieved across these processing iterations.

Our GDA-GBT model can outperform molecular feature-based ML models. Recently, the SOAP descriptor-based GBT model, known as SOAP-MLM166, has been used for 2D perovskite bandgap prediction. It has a COD ≈ 0.90 and MAE ≈ 0.103 (eV) as demonstrated in Table 1. Further, SOAP descriptor has been combined with autoencoder network107 and kernel ridge regression (KRR) method108 for feature reduction and bandgap prediction67, in particular 3D perovskite datasets67,109,110. However, the SOAP-KRR model has a poorer performance compared to MLM1 when it comes to the NMSE database.

Our GDA-GBT model can also outperform various GNN models. Recently, GNN-based models have demonstrated good performance with 3D perovskite datasets22,23,67,102. We have systematically compared with GNN-based methods on the NMSE database, including CGCNN67, GCN75, ECCN76, TFGNN106, SIGNNA80, and SIGNNAc80. For Table 1, it has been found that our GDA-GBT generally has a better performance. In general, fingerprint-based models perform better than these GNN models. This may be due to the limited training data size and more complicated structures (of the unit cell).

Our GDA-GBT model remains the best model under different training datasets. Since the NMSE database is continually updated, the models presented in Table 1 are trained with different sizes of perovskite data. Note that the size of the dataset used in each model is presented in Table 1. In general, three different sizes, 445, 515, and 624, are used. For a fair comparison, we have also trained our GDA-GBT models on these three datasets. The results are presented in Supplementary Table 1. In general, our GDA-GBT model still outperforms existing models on all these datasets. A detailed discussion can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

Influence of selected features on GDA-GBT models

A careful analysis of the feature importance scores can provide a better understanding of the learning models. Here we consider two different models of selected features from our GDA fingerprints. We first consider the halide atom-based density fingerprint (HF) and combine it with the GBT model, i.e., termed as the GDA(HF)-GBT model. We find that the GDA(HF)-GBT model yields a COD of approximately 0.86 and MAE of around 0.094 (eV), which are better than the performance of all the GNN-based models, except the SIGNNA model. A detailed discussion of the GDA(HF)-GBT model can be found in Method and Supplementary Note 2.

Secondly, GDA importance-based density fingerprints, i.e., GDA(IF), are also considered. The central concept revolves around focusing on GDA features that have been identified as highly significant through GBT-based importance analysis, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Specifically, we extracted the top 1000 most important features from the GDA set to create a streamlined input feature vector for the GBT model. This approach serves as a means to reduce feature dimensionality and mitigate the challenges associated with the curse of high feature dimensionality in machine learning models111. Examining the results in Table 1, it is evident that the GDA(IF)-GBT model, incorporating all these crucial features, exhibits slightly superior performance when compared to the GDA-GBT model.

An illustration of predicted values and error distributions can be found in Supplementary Fig. 2. We have also systematically studied various element-specific models with different site and atom combinations, the results can be found in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2. A detailed discussion can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

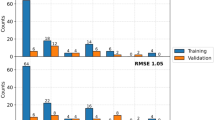

Influence of Exp/DFT-based bandgap labels on GDA-GBT models

As a further comparison of the findings presented in Table 1, which are primarily rooted in DFT bandgap data, we also conducted a comprehensive evaluation of our GDA-GBT and GDA(IF)-GBT models. This assessment encompasses both DFT-based and Exp-based bandgap labels for 2D perovskites. To be specific, our analysis involved 716 compounds with DFT-based bandgap values and 235 compounds with Exp-based bandgap values, as supported by the unit cell representation from the pymatgen package112. This assessment consisted of two distinct experiments. Firstly, we performed a 5 times 5-fold cross-validation on the subset of 235 compounds with experimental bandgap data to calculate the normalized mean squared error (NMSE). Subsequently, our second experiment involved training the GDA-GBT model on the DFT-based dataset and testing it on the Exp-based dataset. The outcomes of these experiments are presented in Table 2.

It is noteworthy that while the GDA(IF) features exhibit a slight performance edge over the GDA features in the context of DFT-based materials, the latter, in turn, exhibit a slightly superior performance compared to the importance-based features. This observation suggests that the entire set of 4500 features may offer additional insights for predicting experimental bandgaps. This, in turn, opens up a promising avenue for future research, focusing on exploring the relationship between GDA descriptors and the experimental bandgaps of materials.

It can be seen that both results are inferior to the ones using only DFT datasets. For the 5-fold cross-validation on the Exp subset, its inferior performance may be due to the relatively smaller data size, which is less than one-third of the DFT-based subset. For training on DFT and testing on the Exp model, it has the worst performance as with the MAE and RMSE roughly two times larger than the DFT-only model. This may indicate the discrepancy between the DFT calculation and experimental results. It also indicates the importance of incorporating Exp labels to boost the performance of models.

Prediction of bandgaps for new 2D materials

To investigate the predicting ability of our models, we studied the 2D perovskites in the NMSE database without bandgap labels, i.e., only the experimental 3D structures are available. More specifically, materials from the NMSE databank with material indices 110, 309, 315, 363, and 452 are used in this study. To evaluate the performance, we systematically computed their DFT bandgaps and compared them with the predictions of our proposed GDA models. The five structures are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3 and the detailed DFT settings are discussed in Supplementary Note 4.

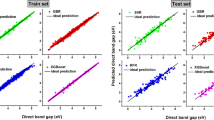

Figure 3 showcases the calculated and predicted bandgap values for five distinct compounds, with the order (110, 315, 452, 309, 363) corresponding to the order of calculated DFT bandgap magnitudes. Specifically, treating the calculated DFT bandgaps as test labels, we computed the MAE values for GDA-GBT and GDA(IF)-GBT, resulting in 0.4179 eV and 0.4282 eV, respectively. While these MAE values are notably higher than those in Tables 1 and 2, this disparity may be due to two major reasons. First, the current data set is still very small with only 849 data points and very few of them are within the range of 0 to 2 eV. Second, DFT models with different parameter settings can result in a huge difference in their predicted values of the 2D band gap. This may be due to the highly complicated 2D perovskite structures. Furthermore, with only minor distinctions, as demonstrated in Fig. 3 and elaborated in Supplementary Table 3, the proposed models consistently preserve the ascending order of the DFT labels. In summary, the GAD-GBT framework exhibits potential in accurately representing crystalline structures and delivering stable bandgap predictions. Additional material details, calculated DFT bandgap values, and prediction data can be found in Supplementary Table 3 in Supplementary Note 4.

Materials are from NMSE but without bandgap labels. Using the DFT model, we evaluated their bandgap values (marked in green). The predicted bandgaps (eV) are marked in blue. The x-axes represent the material indices (110, 315, 452, 309, 363). The y-axes denote bandgap ranges in eV. The MAE values for GDA-GBT and GDA(IF)-GBT predictions are 0.4179 (eV) and 0.4282 (eV), respectively.

Methods

Material mathematical representation

As a cornerstone of the physical and machine learning models, the mathematical representation of molecular data is now a major research target in computational materials. In particular, graphs, networks, and simplicial complexes encode pairwise or higher-order interactions between or among atoms in molecules and have become one of the most important ML frameworks in predicting molecular properties81,82. This section introduces the mathematical representation of material data, in particular, the density fingerprint.

Motif and unit cell

The unit cell is a key concept in describing the crystal structure of a material. It refers to a repeating local atomic system that is mathematically defined as a parallelepiped spanned by a basis \({{{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}}}}=\{{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{1},{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{2},{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{3}\}\) in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\). The induced lattice \({{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}\) is the set of all integral linear combinations of \({{{{{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}}}}\). In other words, the unit cell U is defined as \(U=\{{c}_{1}{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{1}+{c}_{2}{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{2}+{c}_{3}{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{3}\,| \,{c}_{1},{c}_{2},{c}_{3}\in \left[0,1\right)\}\) and the lattice \({{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}\) is defined as \({{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}=\{{c}_{1}{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{1}+{c}_{2}{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{2}+{c}_{3}{{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}}_{3}\,| \,{c}_{1},{c}_{2},{c}_{3}\in {\mathbb{Z}}\}\). A motif M is a non-empty subset of U, and the periodic point set S is defined as the Minkowski sum of \({{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}\) and M, i.e., \(S=M+{{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}=\{{{{{{{{\bf{u}}}}}}}}+{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}\,| \,{{{{{{{\bf{u}}}}}}}}\in M,{{{{{{{\bf{v}}}}}}}}\in {{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}\}\). The motif can be viewed as a local atomic system with respect to a coordinate system or a unit cell in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), and the associated periodic point set of the motif forms the entire material structure.

Material descriptors and fingerprints

Traditional material descriptors and fingerprints

Perovskite descriptors provide general insights into the structural and physical properties of perovskite crystals and have been widely used in QSAR/QSPR models. Traditional molecular descriptors for materials include atomic radius, ionic radius, orbital radius, tolerance factor, octahedral factor, packing factor, crystal structure measurements, surface/volume features, and physical properties such as ionization potential, ionic polarizability, electron affinity, Pauling electronegativity, valence orbital radii, and HOMO and LUMO, etc113,114,115. Recently, a series of material fingerprints have been proposed, including Coulomb matrix62,62, sine Coulomb matrix116, Ewald sum matrices116, many-body tensor representation (MBTR)63, atom-centered symmetry function (ACSF)65, and smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP)64.

TDA-based material fingerprints

Compared to traditional perovskite descriptors and fingerprints, TDA-based perovskite models have two great advantages, i.e., intrinsic representation and multiscale modeling81,82. More specifically, TDA uses topological invariants, i.e., Betti number, to characterize the intrinsic and fundamental structural and interactional properties. With high abstraction and intrinsic information, TDA-based features can have better transferability and interpretability for learning models. Furthermore, molecular systems exhibit a plethora of interactions at different scales, encompassing covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, electrostatic interactions, etc. Through a filtration process, TDA can comprehensively characterize all these interactions on an equal footing. This provides a multiscale model for the characterization of perovskite systems81,82. Recently, TDA-based models have demonstrated great performance in material data analysis32,89,91,102,117.

GDA-based material fingerprint

Different from other molecular systems, materials have unique periodic information at the atomic level, which plays a significant role in material functions and properties. However, traditional learning models usually ignore the information or consider periodic information implicitly by using periodic graphs or supercells. To explicitly address the periodic information, we consider the newly proposed multiscale feature representation model, called density fingerprint, which was originally introduced for the study of periodic crystalline structures in Euclidean spaces100. The key advantage of DF lies in its ability to provide an efficient multiscale geometric representation of both cell structures and periodic information. DF offers intuitive and explainable features for periodic crystalline data due to its geometric invariance and stability (or continuity). It does not require cell extension and can be computed on any unit cell, independent of the choice of motif and unit cell.

Mathematical background for density fingerprint

Given a periodic set \(S\subseteq {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) and t≥ 0, let S(t) = {B(x, t)∣x ∈ S} denote the family of all closed balls centered at points in S with radius t. The set \({\bigcup }^{k}S(t)=\{{{{{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}| {{{{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}}}\,\,{{\mbox{belongs to at least}}}\,\,k\,\,{{\mbox{balls in}}}\,\,S(t)\}\) is defined as the k-fold cover of S(t). This concept captures the interaction behavior of neighborhoods over the set S. The fractional volume of the k-fold cover of S is defined as the probability

The k-th density function (cf.100,101) of a periodic set S is a function \({\psi }_{k}^{S}:[0,\infty )\to [0,1]\) defined as follows:

The density fingerprint of S is defined as the sequence \(\Psi (S)={({\psi }_{k}^{S})}_{k = 0}^{\infty }\) of density functions associated with S. By selecting a finite range t ∈ [0, T] and a finite K, one can consider each curve \({\psi }_{k}^{S}:[0,T]\to [0,1]\) (k = 1, 2,…,K) in the sequence as a feature vector of the periodic set S. These feature vectors can then be used to train machine learning models.

Figure 1 shows an example of density fingerprints \({\psi }_{0}^{S},{\psi }_{1}^{S},{\psi }_{2}^{S}\) defined on the interval [0, 1]. In this case, the set S is the sum of sets \(M+{{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}\), where M = {(0, 0, 0)} and \({{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}\) is the lattice spanned by the standard basis e1 = (1, 0, 0), e2 = (0, 1, 0), and e3 = (0, 0, 1). In particular, the unit cell U and the motif M are defined as the sets \({\left[0,1\right)}^{3}\) and {(0, 0, 0)} respectively, and all the vertices of the closed cube \(\overline{U}={[0,1]}^{3}\) belong to the periodic set S.

Through detailed explicit construction of neighborhoods S(t) in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), DF offers an advanced geometric perspective that seamlessly integrates various unit cell properties, including angles, diameters, shapes, distortions, and overall periodicity. Mathematically, DF has invariance and stability properties that will guarantee the uniqueness of DF in the representation of unit cell structures. This means that the same material, even under different unit cell models, will have exactly the same DF, and a slight change (or perturbation) of material structure (i.e., atom positions) will result in the change of DF, as demonstrated in Supplementary Figs. 4–5. A detailed discussion of DF invariance and stability properties can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

Element-specific density fingerprints

Element-specific density fingerprints concern the geometry and topology of certain atomic systems or their combinations. It has been applied and shown high performance in bioinformatics molecules84,118 and 2D perovskites67,102. Here we consider the DFs generated from not only the entire structure but also different site combinations and atom types. More specifically, the site combinations include ACB, ACX, ACBX, BX, B, and X. A-site atom types include C, H, O, and N. B-site atom types include Bi, Cd, Ge, Pb, and \({{{{{{{\rm{Sn}}}}}}}}\), which are the main inorganic and metal atoms of materials with DFT-based bandgaps in NMSE. X-site atom types include Cl, Br, and I. We call a DF generated from a certain atom type or site combination the element-specific DF. Our GDA-based perovskite fingerprint contains a series of these element-specific DFs.

Furthermore, different combinations of element-specific DFs are considered in our GDA(HF) and GDA(IF) models. Note that GDA(HF) considers only the halide atom-based density fingerprint (HF) and GDA(IF) uses an importance-based density fingerprint (IF). In particular, our GDA(IF) model selects element-specific DFs based on the importance analysis results as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Computationally, we calculate the DF over the interval [0, 12] in angstroms (Å). The interval is uniformly divided into 50 grid points. In our experiment, each DF contains five 1D density functions including ψ0, ψ1, ψ2, ψ3, and ψ4, thus its size is 250, and the total dimension of the input vector of GDA-GBT is 4500.

GDA-GBT and GNN models for 2D perovskites

In our GBT model, we utilized 10000 estimators with maximal depth 7 to analyze the input DF features and used the squared error as the loss metric. The minimum number of samples is 2, the learning rate is 0.001, and the subsampling rate in the training process is set to 0.7, respectively. Note that we have not systematically optimized these parameters, instead we just adopt the basic setting with minor revisions from the algebraic graph-assisted bidirectional transformer model119. For the input feature vector, we employ the function f(x) = 10x to rescale the curves ψ0, ψ1, …, ψ4 from the range of [0, 1] to [1, 10]. This rescaling procedure serves to accentuate the distinctions between the curves, thereby facilitating their classification.

Among all the GNN models for 2D perovskites, SIGNNA model80 has the best performance. In this model, perovskite structures are divided into different sub-structures based on physical properties (for example, the organic and inorganic atom sub-systems). Different GNN models are employed for different sub-structures and learned latent vectors are combined together as the input for a multi-layer neural network. It is found that these substructure neural networks can extract features with heterogeneous properties and achieve better performance in predicting the physical and chemical properties of perovskite structures. This is consistent with the results of our element-specific models.

The size of the training database influences the performance of AI models. Due to the continuous updating of the NMSE database, models in Table 1 use different data sizes. More precisely, the MLM1 model utilizes 515 compounds66, the SOAP-based KRR involves 445 compounds67, all the GNN models (GCN75, ECCN76, CGCNN21, TFGNN106, and SIGNNA80) use 624 data points. To ensure a fair comparison with all existing SOTA models21,66,67, we also trained our GDA-GBT models on the same datasets as previous models. Supplementary Table 1 shows the performances of GDA-GBT models with different data sizes. It can be seen that our GDA-GBT can still outperform all previous models on their datasets.

Data availability

All 2D perovskite data used in this work are available on the official website of the NMSE database: http://www.pdb.nmse-lab.ru/. All materials in the database are encoded in the Crystallographic Information File (CIF) format and can be freely accessed. Descriptions of material properties such as DFT-based or experimental bandgaps, chemical formulas, space groups, etc., are provided on the official website.

Code availability

The code used to generate the DF in this paper can be accessed on the project’s GitHub page: https://github.com/peterbillhu/DFOn2DProveskites. Historic versions, updates, tutorials, parameter descriptions, and essential code can be browsed and accessed on the project’s GitHub. If necessary, please contact the authors for further technical support.

References

Crabtree, G., Glotzer, S., McCurdy, B. & Roberto, J. Computational materials science and chemistry: accelerating discovery and innovation through simulation-based engineering and science. Tech. Rep., USDOE Office of Science (SC)(United States) (2010).

Moskowitz, S. L. The advanced materials revolution: technology and economic growth in the age of globalization. (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014).

Science, N & T. C. Materials genome initiative for global competitiveness. (Executive Office of the President, National Science, and Technology Council: Washington, D.C., USA, (2011).

Green, M. L. et al. Fulfilling the promise of the materials genome initiative with high-throughput experimental methodologies. Appl. Phys. Rev. 4, 011105 (2017).

Grancini, G. & Nazeeruddin, M. K. Dimensional tailoring of hybrid perovskites for photovoltaics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 4–22 (2019).

Mao, L., Stoumpos, C. C. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Two-dimensional hybrid halide perovskites: principles and promises. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1171–1190 (2018).

Fakharuddin, A. et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes. Nat. Electron. 5, 203–216 (2022).

Min, H. et al. Perovskite solar cells with atomically coherent interlayers on SnO2 electrodes. Nature 598, 444–450 (2021).

Sharma, R., Sharma, A., Agarwal, S. & Dhaka, M. S. Stability and efficiency issues, solutions and advancements in perovskite solar cells: a review. Solar Energy 244, 516–535 (2022).

Ahmad, S. et al. Dion-Jacobson phase 2D layered perovskites for solar cells with ultrahigh stability. Joule 3, 794–806 (2019).

Mao, L., Wu, Y., Stoumpos, C. C., Wasielewski, M. R. & Kanatzidis, M. G. White-light emission and structural distortion in new corrugated two-dimensional lead bromide perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5210–5215 (2017).

Ma, C. et al. Photovoltaically top-performing perovskite crystal facets. Joule 6, 2626–2643 (2022).

Jia, Q. et al. Strong synergistic effect of the (110) and (100) facets of the SrTiO3 perovskite micro/nanocrystal: decreasing the binding energy of exciton and superb photooxidation capability for \({{{{{{{{\rm{Co}}}}}}}}}_{2}^{+}\). Nanoscale 14, 12875–12884 (2022).

Wu, G. et al. 2D hybrid halide perovskites: structure, properties, and applications in solar cells. Small 17, 2103514 (2021).

Han, Y., Yue, S. & Cui, B.-B. Low-dimensional metal halide perovskite crystal materials: structure strategies and luminescence applications. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004805 (2021).

Pilania, G., Wang, C. C., Jiang, X., Rajasekaran, S. & Ramprasad, R. Accelerating materials property predictions using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 3, 2810 (2013).

Rajan, K. Materials informatics. Mater. Today 8, 38–45 (2005).

Rajan, K. Informatics for materials science and engineering: data-driven discovery for accelerated experimentation and application. (Butterworth-Heinemann, Kidlington, Oxford, UK, 2013).

Agrawal, A. & Choudhary, A. Perspective: Materials informatics and big data: realization of the “fourth paradigm” of science in materials science. Apl. Mater. 4, 053208 (2016).

Ward, L. & Wolverton, C. Atomistic calculations and materials informatics: A review. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 21, 167–176 (2017).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Chen, C., Ye, W., Zuo, Y., Zheng, C. & Ong, S. P. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 31, 3564–3572 (2019).

Schütt, K. et al. Schnet: A continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 992–1002 (2017).

Schmidt, J., Pettersson, L., Verdozzi, C., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. Crystal graph attention networks for the prediction of stable materials. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7948 (2021).

Wang, A. Y.-T., Kauwe, S. K., Murdock, R. J. & Sparks, T. D. Compositionally restricted attention-based network for materials property predictions. Npj Comput. Mater. 7, 77 (2021).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Fung, V., Zhang, J., Juarez, E. & Sumpter, B. G. Benchmarking graph neural networks for materials chemistry. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 84 (2021).

Ramprasad, R., Batra, R., Pilania, G., Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A. & Kim, C. Machine learning in materials informatics: recent applications and prospects. npj Comput. Mater. 3, 54 (2017).

Himanen, L. et al. DScribe: Library of descriptors for machine learning in materials science. Comput. Phys. Commun. 247, 106949 (2020).

Goodall, R. E. A. & Lee, A. A. Predicting materials properties without crystal structure: deep representation learning from stoichiometry. Nat. Commun. 11, 6280 (2020).

Antunes, L. M., Grau-Crespo, R. & Butler, K. T. Distributed representations of atoms and materials for machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 44 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Encoding the atomic structure for machine learning in materials science. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1558 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Machine learning for perovskite solar cells and component materials: key technologies and prospects. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214271 (2023).

Damewood, J. et al. Representations of materials for machine learning. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 53, 399–426 (2023).

Hey, T. et al. The fourth paradigm: data-intensive scientific discovery, vol. 1 (Microsoft Research Redmond, Redmond, WA, US, 2009).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. Appl. Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Choudhary, K. et al. The joint automated repository for various integrated simulations (JARVIS) for data-driven materials design. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 173 (2020).

Scheidgen, M. et al. NOMAD: A distributed web-based platform for managing materials science research data. J. Open Source Softw. 8, 5388 (2023).

Curtarolo, S. et al. Aflowlib.org: A distributed materials properties repository from high-throughput ab initio calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 58, 227–235 (2012).

Kirklin, S. et al. The open quantum materials database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Comput. Mater. 1, 1–15 (2015).

Pilania, G., Balachandran, P. V., Kim, C. & Lookman, T. Finding new perovskite halides via machine learning. Front. Mater. 3, 19 (2016).

Balachandran, P. V. et al. Predictions of new ABO3 perovskite compounds by combining machine learning and density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 043802 (2018).

Li, Z., Xu, Q., Sun, Q., Hou, Z. & Yin, W.-J. Stability engineering of halide perovskite via machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.06042 (2018).

Park, H. et al. Exploring new approaches towards the formability of mixed-ion perovskites by DFT and machine learning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 1078–1088 (2019).

Schmidt, J. et al. Predicting the thermodynamic stability of solids combining density functional theory and machine learning. Chem. Mater. 29, 5090–5103 (2017).

Pilania, G. et al. Machine learning bandgaps of double perovskites. Sci. Rep. 6, 19375 (2016).

Askerka, M. et al. Learning-in-templates enables accelerated discovery and synthesis of new stable double perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3682–3690 (2019).

L. Agiorgousis, M., Sun, Y.-Y., Choe, D.-H., West, D. & Zhang, S. Machine learning augmented discovery of chalcogenide double perovskites for photovoltaics. Adv. Theory Simul. 2, 1800173 (2019).

Li, Z., Xu, Q., Sun, Q., Hou, Z. & Yin, W.-J. Thermodynamic stability landscape of halide double perovskites via high-throughput computing and machine learning. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1807280 (2019).

Im, J. et al. Identifying Pb-free perovskites for solar cells by machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 37 (2019).

Jacobs, R., Luo, G. & Morgan, D. Materials discovery of stable and nontoxic halide perovskite materials for high-efficiency solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1804354 (2019).

Wu, T. & Wang, J. Global discovery of stable and non-toxic hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites for photovoltaic systems by combining machine learning method with first principle calculations. Nano Energy 66, 104070 (2019).

Lu, S. et al. Accelerated discovery of stable lead-free hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites via machine learning. Nat. Commun. 9, 3405 (2018).

Li, J., Pradhan, B., Gaur, S. & Thomas, J. Predictions and strategies learned from machine learning to develop high-performing perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1901891 (2019).

Odabaşı, Ç. & Yıldırım, R. Assessment of reproducibility, hysteresis, and stability relations in perovskite solar cells using machine learning. Energy Technol. 8, 1901449 (2020).

Odabaşı, Ç. & Yıldırım, R. Machine learning analysis on stability of perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 205, 110284 (2020).

Howard, J. M., Tennyson, E. M., Neves, B. R. A. & Leite, M. S. Machine learning for perovskites’ reap-rest-recovery cycle. Joule 3, 325–337 (2019).

Yu, Y., Tan, X., Ning, S. & Wu, Y. Machine learning for understanding compatibility of organic–inorganic hybrid perovskites with post-treatment amines. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 397–404 (2019).

Schütt, K. T. et al. How to represent crystal structures for machine learning: towards fast prediction of electronic properties. Phys. Rev. B 89, 205118 (2014).

Isayev, O. et al. Materials cartography: representing and mining materials space using structural and electronic fingerprints. Chem. Mater. 27, 735–743 (2015).

Huan, T. D., Mannodi-Kanakkithodi, A. & Ramprasad, R. Accelerated materials property predictions and design using motif-based fingerprints. Phys. Rev. B 92, 014106 (2015).

Rupp, M., Tkatchenko, A., Müller, K.-R. & Von Lilienfeld, O. A. Fast and accurate modeling of molecular atomization energies with machine learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 058301 (2012).

Huo, H. & Rupp, M. Unified representation of molecules and crystals for machine learning. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 3, 045017 (2022).

Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

Behler, J. Atom-centered symmetry functions for constructing high-dimensional neural network potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 074106 (2011).

Marchenko, E. I. et al. Database of two-dimensional hybrid perovskite materials: open-access collection of crystal structures, band gaps, and atomic partial charges predicted by machine learning. Chem. Mater. 32, 7383–7388 (2020).

Mayr, F. & Gagliardi, A. Global property prediction: A benchmark study on open-source, perovskite-like datasets. ACS Omega 6, 12722–12732 (2021).

Atz, K., Grisoni, F. & Schneider, G. Geometric deep learning on molecular representations. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 1023–1032 (2021).

Bronstein, M. M., Bruna, J., LeCun, Y., Szlam, A. & Vandergheynst, P. Geometric deep learning: Going beyond Euclidean data. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 34, 18–42 (2017).

Bronstein, M. M., Bruna, J., Cohen, T. & Veličković, P. Geometric deep learning: Grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.13478 (2021).

Masci, J., Boscaini, D., Bronstein, M. & Vandergheynst, P. Geodesic convolutional neural networks on Riemannian manifolds. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision workshops, 37–45 (2015).

Hamilton, W., Ying, Z. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 1025–1035 (2017).

Vashishth, S., Sanyal, S., Nitin, V. & Talukdar, P. Composition-based multi-relational graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2020) (2020).

Veličković, P. et al. Graph attention networks. stat 1050, 10–48550 (2017).

Welling, M. & Kipf, T. N. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2017) (2017).

Park, C. W. & Wolverton, C. Developing an improved crystal graph convolutional neural network framework for accelerated materials discovery. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 063801 (2020).

Louis, S.-Y. et al. Graph convolutional neural networks with global attention for improved materials property prediction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 18141–18148 (2020).

Choudhary, K. & DeCost, B. Atomistic line graph neural network for improved materials property predictions. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 185 (2021).

Yan, K., Liu, Y., Lin, Y. & Ji, S. Periodic graph transformers for crystal material property prediction. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 15066–15080 (2022).

Na, G. S. Substructure interaction graph network with node augmentation for hybrid chemical systems of heterogeneous substructures. Comput. Mater. Sci. 216, 111835 (2023).

Cang, Z., Mu, L. & Wei, G.-W. Representability of algebraic topology for biomolecules in machine learning based scoring and virtual screening. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1005929 (2018).

Nguyen, D. D., Cang, Z. X. & Wei, G.-W. A review of mathematical representations of biomolecular data. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 4343–4367 (2020).

Cang, Z. X. et al. A topological approach for protein classification. Comput. Math. Biophys. 3, 140–162 (2015).

Cang, Z. X. & Wei, G.-W. Integration of element specific persistent homology and machine learning for protein-ligand binding affinity prediction. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnm.2914 (2017).

Cang, Z. X. & Wei, G.-W. TopologyNet: Topology based deep convolutional and multi-task neural networks for biomolecular property predictions. PLOS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005690 (2017).

Wu, K. D. & Wei, G.-W. Quantitative toxicity prediction using topology based multi-task deep neural networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00558 (2018).

Wu, K., Zhao, Z., Wang, R. & Wei, G.-W. TopP–S: Persistent homology-based multi-task deep neural networks for simultaneous predictions of partition coefficient and aqueous solubility. J. Comput. Chem. 39, 1444–1454 (2018).

Demir, A. & Kiziltan, B. Multiparameter persistent homology for molecular property prediction. In ICLR 2023-Machine Learning for Drug Discovery workshop (2023).

Hiraoka, Y. et al. Hierarchical structures of amorphous solids characterized by persistent homology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, 7035–7040 (2016).

Lee, Y. et al. Quantifying similarity of pore-geometry in nanoporous materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–8 (2017).

Saadatfar, M., Takeuchi, H., Robins, V., Francois, N. & Hiraoka, Y. Pore configuration landscape of granular crystallization. Nat. Commun. 8, 15082 (2017).

Hirata, A., Wada, T., Obayashi, I. & Hiraoka, Y. Structural changes during glass formation extracted by computational homology with machine learning. Commun. Mater. 1, 98 (2020).

Obayashi, I., Nakamura, T. & Hiraoka, Y. Persistent homology analysis for materials research and persistent homology software: HomCloud. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 91, 091013 (2022).

Najman, L. & Romon, P. Modern Approaches to Discrete Curvature. (Springer International Publishing, Gewerbestrasse, Cham, Switzerland, 2017).

Forman, R. Bochner’s method for cell complexes and combinatorial Ricci curvature. Discrete Comput. Geom. 29, 323–374 (2003).

Bakry, D. & Émery, M. Diffusions hypercontractives. In Séminaire de Probabilités XIX 1983/84: Proceedings, 177–206 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006).

Wee, J. & Xia, K. Ollivier persistent Ricci curvature-based machine learning for the protein–ligand binding affinity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 1617–1626 (2021).

Wee, J. & Xia, K. Forman persistent Ricci curvature (FPRC)-based machine learning models for protein–ligand binding affinity prediction. Brief. Bioinforma. 22, bbab136 (2021).

Weber, M., Saucan, E. & Jost, J. Characterizing complex networks with Forman-Ricci curvature and associated geometric flows. J. Complex Netw. 5, 527–550 (2017).

Edelsbrunner, H., Heiss, T., Kurlin, V., Smith, P. & Wintraecken, M. The density fingerprint of a periodic point set. In 37th International Symposium on Computational Geometry (2021).

Anosova, O. & Kurlin, V. Density functions of periodic sequences of continuous events. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 65, 689–701 (2023).

Anand, D. V., Xu, Q., Wee, J., Xia, K. & Sum, T. C. Topological feature engineering for machine learning based halide perovskite materials design. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 203 (2022).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Piryonesi, S. M. & El-Diraby, T. E. Data analytics in asset management: Cost-effective prediction of the pavement condition index. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 26, 04019036 (2020).

Chun, M. et al. Stroke risk prediction using machine learning: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28, 1719–1727 (2021).

Shi, Y. et al. Masked label prediction: Unified message passing model for semi-supervised classification. In 30th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 1548–1554 (2021).

Wang, Y., Yao, H. & Zhao, S. Auto-encoder based dimensionality reduction. Neurocomputing 184, 232–242 (2016).

Vovk, V. Kernel ridge regression. In Empirical inference: Festschrift in honor of Vladimir N. Vapnik, 105–116 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013).

Kim, C., Huan, T. D., Krishnan, S. & Ramprasad, R. A hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite dataset. Sci. data 4, 1–11 (2017).

Pandey, M. & Jacobsen, K. W. Promising quaternary chalcogenides as high-band-gap semiconductors for tandem photoelectrochemical water splitting devices: A computational screening approach. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 105402 (2018).

Rao, H. et al. Feature selection based on artificial bee colony and gradient boosting decision tree. Appl. Soft Comput. 74, 634–642 (2019).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): A robust, open-source Python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Li, W., Ionescu, E., Riedel, R. & Gurlo, A. Can we predict the formability of perovskite oxynitrides from tolerance and octahedral factors? J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 12239–12245 (2013).

Filip, M. R. & Giustino, F. The geometric blueprint of perovskites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 5397–5402 (2018).

Bartel, C. et al. New tolerance factor to predict the stability of perovskite oxides and halides. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav0693 (2019).

Faber, F., Lindmaa, A., Von Lilienfeld, O. A. & Armiento, R. Crystal structure representations for machine learning models of formation energies. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 115, 1094–1101 (2015).

Jiang, Y. et al. Topological representations of crystalline compounds for the machine-learning prediction of materials properties. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 28 (2021).

Szocinski, T., Nguyen, D. D. & Wei, G.-W. AweGNN: Auto-parametrized weighted element-specific graph neural networks for molecules. Comput. Biol. Med. 134, 104460 (2021).

Chen, D. et al. Algebraic graph-assisted bidirectional transformers for molecular property prediction. Nat. Commun. 12, 3521 (2021).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. Vesta 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Nanyang Technological University SPMS Collaborative Research Award 2022, Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research fund Tier 2 grants MOE-T2EP20120-0013, MOE-T2EP20221-0003, and MOE-T2EP50120-0004 as well as the National Research Foundation (NRF), Singapore under its NRF Investigatorship (NRF-NRFI2018-04) and Competitive Research Program (CRP) (NRF-CRP25-2020-0004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.C.S. and K.X. conceived the idea and designed the research. M.C.W. and C.S.H. wrote the code for the density fingerprint model. C.S.H. performed the density fingerprint simulations. C.S.H. performed the GDA-based machine learning models. R. M. provided the DFT results. All authors analyzed the data, discussed the results, and contributed to the manuscript. T.C.S. and K.X. led the project. The computational work for this paper was partially performed on resources of the National Supercomputing Centre (NSCC), Singapore (https://www.nscc.sg).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, CS., Mayengbam, R., Wu, MC. et al. Geometric data analysis-based machine learning for two-dimensional perovskite design. Commun Mater 5, 106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00545-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00545-w