Abstract

Understanding the atomistic structure of the active site during catalytic reactions is of paramount importance in both fundamental studies and practical applications, but such studies are challenging due to the complexity of heterogeneous systems. Here, we use Pt/CeO2 as an example to study the dynamic nature of active sites during the water-gas-shift reaction (WGSR) by combining multiple in situ characterization tools. We show that the different concentrations of interfacial Ptδ+ – O – Ce4+ moieties at Pt/CeO2 interfaces are responsible for the rank of catalytic performance of Pt/CeO2 catalysts: Pt/CeO2-rod > Pt/CeO2-cube > Pt/CeO2-oct. For all the catalysts, metallic Pt is formed during the WGSR, leading to the transformation of the active sites to Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+ and interface reconstruction. These findings shed light on the nature of the active site for the WGSR on Pt/CeO2 and highlight the importance of combining complementary in situ techniques for establishing structure-performance relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With increasing energy demand, supplying clean and affordable energy is a critical challenge. Among various clean energy sources, hydrogen (H2) is one of the most promising energy carriers1,2. Currently, over 95% of hydrogen is produced from steam reforming of fossil fuels. To eliminate the carbon monoxide (CO) present in product streams, the water-gas shift reaction (WGSR) is required to produce hydrogen with a high purity for ammonia synthesis and fuel cell applications3,4. WGSR is an exothermic reaction and, therefore, is thermodynamically limited at high temperatures and kinetically limited at low temperatures2,3,5,6. Thus, the production of H2 in large-scale industrial plants involves a two-step process: a high-temperature step on iron oxide-based catalysts7 and a low-temperature step on copper-based catalysts2. While copper-based catalysts exhibit high activity at low temperatures, they are easily subject to thermal sintering and to chemical poisoning8,9. Considering both catalyst activity and stability, different catalysts have been developed for low-temperature WGSR10,11,12,13. Among them, platinum-ceria (Pt/CeO2) catalysts have gained much interest in the past decade due to their remarkable catalytic performances. It is generally accepted that the WGSR starts with the activation of CO and H2O on Pt and oxygen vacancies of CeO2, respectively, followed by the formation of carboxyl group and/or formate intermediates at the metal-oxide interface to produce CO2 and H214,15. However, depending on the catalyst preparation and reaction conditions, different catalytic active sites at Pt-CeO2 interfaces, such as Pt2+ – O – Ce4+ and Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+ (Ov represents the oxygen vacancy), have been proposed for the WGSR on the Pt/CeO2 catalysts14,16,17. Consequently, the presence of two different sites causes the discussion regarding the identification of active site for the WGSR. For example, González et al.16 reported that PtOx species preferentially interact with Ce on a Ce-TiO2 surface, leading to a higher dispersion and uniformity of Ptδ+ species on the oxide support, which favors the reduction of CeO2. Therefore, the modification of the reducibility of the oxide support by Ptδ+ species results in a higher catalytic activity and stability of Pt supported on Ce-TiO2 than on bare CeO2 or TiO2. More recently, by performing in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy, Li et al.17 proposed that the unique electronic structure and binding environment of the perimeter Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+ sites regulate the adsorbate behaviors that enable high activity of Pt/CeO2 in the WGSR. Indeed, the catalyst surface is highly dynamic under reaction conditions18,19,20. The complexity of adsorbate-surface interactions and structural reconstruction of working catalysts require in situ experimental studies to capture the transformation of heterogeneous interfaces at the atomic level, which is crucial to providing mechanistic insight into the WGSR on the Pt/CeO2 catalyst. Here, CeO2 supports with different exposed facets, including (110), (100), and (111), were fabricated by a hydrothermal method. After in situ deposition of Pt nanoparticles by a chemical reduction method, the Pt/CeO2 catalysts with well-defined nanostructure were used as model catalysts to reveal the dynamics of active sites during the WGSR. In situ experiments demonstrated the structural evolution of catalysts under reaction conditions. For all the catalysts, metallic Pt (Pt0) was formed during the WGSR, even though traces of both Ptδ+ and Pt0 were present before the reactants were introduced into the system. The combination of the synthesis of model catalysts with controlled nanostructure, environmental transmission electron microscopy (ETEM), and ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (AP-XPS) uncover the highly dynamic nature of the active sites at the Pt/CeO2 interface during the WGSR.

Results

Structural characterization

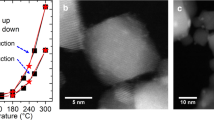

The structure of supported catalysts prepared in this study are presented in Fig. 1. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns show the characteristic planes of the face-centered cubic fluorite structure of CeO221,22. For all the catalysts, no obvious peaks of Pt species were observed, indicating the highly dispersed amorphous or small Pt nanoclusters, which is consistent with the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements, as shown in Fig. 1b–d and Supplementary Figs. 1–3. TEM images show the different morphologies of CeO2 supports. Compared to the CeO2 nanocubes and octahedra, the CeO2 nanorods are less well-ordered, containing a large number of corrugations and surface defects, which may be due to the presence of unstable {110} facets that tend to form {111} microfacets to reduce the surface energy23,24,25. While the CeO2 nanocubes exhibit single-crystal nature with high crystallinity and mainly exposed {100} facets, the surface appears to be irregular due to its polarity. Likewise, the CeO2 octahedra expose predominantly the {111} facets with a truncated structure forming the {100} facets, as shown in Fig. 1d.

a X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of Pt/CeO2 catalysts; b High resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of CeO2 nanorods-supported Pt (Pt/CeO2-rod) catalyst; c High resolution TEM image of CeO2 nanocubes-supported Pt (Pt/CeO2-cube) catalyst; d High resolution TEM image of CeO2 octahedra-supported Pt (Pt/CeO2-oct) catalyst; e Catalytic activities of CeO2 supported Pt catalysts. Solid curves represent the formation rate of CO2 and dash curves represent the formation rate of H2 on the CeO2 supported Pt catalysts.

Catalytic activity

Since the WGSR is thermodynamically limited at high temperature, the reaction has been simulated in ASPEN to predict the thermodynamic equilibrium. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, the WGSR approaches thermodynamic CO conversion at 300 °C. Therefore, the activity tests for all the catalysts were performed under 300 °C. Figure 1e depicts the formation rates of CO2 and H2 on the CeO2 supported Pt catalysts follow the rank: Pt/CeO2-rod > Pt/CeO2-cube > Pt/CeO2-oct.

In situ tracking of dynamics of active sites by spectroscopic characterization

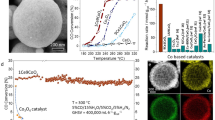

Figure 2 shows the Pt 4f photoemission spectra of the Pt/CeO2 catalysts under different conditions. For all the fresh samples, Pt2+ species dominate the surface composition as evident by features at 73.0 and 76.4 eV in the Pt 4f core level spectra with a small fraction of metallic Pt0 (71.4 and 74.8 eV)26,27,28. In the presence of 0.40 Torr O2 at 400 °C, the formation of Pt4+ was observed on the Pt/CeO2-rod and Pt/CeO2-cube catalysts, as reflected by the peaks located at 74.9 and 78.3 eV27,28, while the oxidation state of Pt remains almost unchanged for the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst (Pt2+). The small fraction of metallic Pt on Pt/CeO2-oct sample after O2 pretreatment may be due to the surface reconstruction of the catalyst, for example, agglomeration of small Pt nanoparticles after pretreatment29. Therefore, a lower photon energy (more surface sensitive) was used (320 eV). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, only oxidized Pt (Pt2+ and Pt4+) species were observed from the Pt 4 f core level, indicating that the top-surface Pt remains oxidized after O2 treatment. Further reduction by 0.40 Torr H2 at 300 °C for 30 min results in almost all the Pt2+ species to be reduced to metallic Pt0 on the Pt/CeO2-oct surface (~98% as shown in Fig. 2f). The reduction of Pt2+ by H2 is much less significant for the Pt/CeO2-rod (~20% of Pt0 as shown in Fig. 2d) and -cube (~40% of Pt0 as shown in Fig. 2e) catalysts.

a Pt 4f spectra of Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst; b Pt 4f spectra of Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst; c Pt 4f spectra of Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst; d oxidation state change of Pt on Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst; e oxidation state change of Pt on Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst; f oxidation state change of Pt on Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst. The solid peaks in a-c represent Pt0. A photon energy of 1100 eV was used. The spectra of fresh catalysts were collected at 400 °C under UHV (2 × 10−8 Torr) conditions. Then, the catalyst was pretreated under 0.40 Torr O2 at 400 °C for 30 min, followed by pretreatment under 0.40 Torr H2 at 300 °C for 30 min. To investigate the oxidation state change of Pt under reaction conditions, the spectra were collected at 300 °C in the presence of 0.35 Torr CO for 60 min. After further introducing 0.70 Torr H2O, another set of spectra were collected at 300 °C for 60 min. The pink solid peaks represent CO adsorption on Pt0 in the presence of CO (and H2O). The percentages of Ptδ+ and Pt0 were obtained from the peak areas of each species. The CO adsorption on Pt0 was included in the calculation of percentage of Pt0. Solid circles in d-f represent the fraction of Pt0, while the open circles represent the fraction of Ptδ+. The survey spectra of all the catalysts are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 5. The oxidation state changes of Pt, Ce and O with time for all the catalysts under different conditions are summarized in Supplementary Figs. 6–13.

As a reducing agent, 0.35 Torr CO reacts with the surface Pt species on all catalysts at 300 °C. After 60 min, the percentage of metallic Pt0 increases from ~20% to ~35% on the Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst, from ~40% to ~75% on the Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst, and ~98% to ~100% on the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst. In addition to the different oxidation states of Pt species, CO adsorption on Pt0 is also observed (72.4 and 75.8 eV) and the peak area increases with time (see Supplementary Fig. 6)30,31. In Supplementary Fig. 9, the Pt 4f spectrum of Pt/CeO2-oct sample shows the CO adsorption on metallic Pt, when a more surface sensitive photon energy (320 eV) was used. Remarkably, the addition of H2O into the system leads to the formation of metallic Pt0 during the WGSR, while the adsorption of CO on Pt0 decreases. As shown in Fig. 2d–f, the percentage of metallic Pt0 increases from 35% to 70% for the Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst, and from 75% to 90% for the Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst, while Pt on the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst remains at metallic state unchanged since CO was introduced to the system (100% of Pt0). The changes of O 1s and Ce 3d spectra are summarized in the Supplementary Figs. 10–13.

In agreement with the AP-XPS results, in situ transmission infrared (TIR) spectra further evidences the change of Pt oxidation state under reaction conditions, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15 and Fig. 3. For all the catalysts, the peaks that appeared in the region between 2000 and 1000 cm−1 (see Supplementary Fig. 14) can be attributed to the O–C–O bands associated with carboxyl group (COOH), formate (HCOO), and carbonate species32,33,34,35. CO adsorption on Pt species can be observed at 1800–2150 cm−1 36,37. The peaks located at 2143 cm−1 (P and R branches at 2200–2100 cm−1) and 2349 cm−1 (P and R branches in the 2400–2300 cm−1 range) are gas phase CO and CO2, respectively38. The peaks observed at 3700–3500 cm−1 are a combination of OH stretching modes of surface hydroxyl (OH) groups and water network34,39.

a In situ TIR spectra of Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst; b In situ TIR spectra of Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst; c In situ TIR spectra of Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst. The bottom panels show a zoomed in version of the plots for the frequency range corresponding to CO and CO2 species, in the range between 2500 cm−1 and 1800 cm−1. The catalyst was pretreated under 0.40 Torr O2 at 400 °C for 30 min, followed by pretreatment under 0.40 Torr H2 at 300 °C for 30 min. Then, the spectrum of the catalyst collected at 300 °C under vacuum conditions was used as background before introducing 0.05 Torr CO. After 60 min, 0.10 Torr H2O was introduced into the system. The full spectra (4000–1000 cm−1) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 14.

CO adsorbs on both Pt0 (~1980 cm−1) and Ptδ+ (~2110 cm−1) for the Pt/CeO2-rod at a pressure of 0.05 Torr. Small features corresponding to Pt0 are seen for -cube catalysts at ~1995 cm−1 and 1870 cm−1. Only CO adsorption on Pt0 was observed on the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst as evidenced by the broad feature between 2150 and 1830 cm−1 ~with peaks centered at 2035, 1991, and 1876 cm−1. The broadness of this band is related the variety of coordination numbers of the metallic surface Pt atoms, which hints at particles with very rough surfaces. There is no obvious gas phase CO observed over Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst. In contrast, the peaks of gas phase CO are more pronounced for the Pt/CeO2-cube and Pt/CeO2-oct catalysts, while the starting CO pressure was same (0.05 Torr). For all the catalysts, the formation of CO2 was observed once CO was introduced into the system, which can be due to the reaction between CO and surface OH groups and lattice O of CeO2. Consequently, the peak areas of gas phase CO2 increase with time for the Pt/CeO2-rod and Pt/CeO2-cube catalysts, while the peak areas of CO adsorbed on different Pt species, gas phase CO and OH group decrease, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. For the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst, the peak areas of all the species (CO, CO2, and OH group) remain almost unchanged, with a very small increase in gas phase CO2 and decrease of gas phase CO. Most of the CO in this case remains bound to the surface Pt. It should be noted that the in situ TIR experiments were performed in a sealed chamber. The reaction between CO and surface species can result in the change of CO pressure. When H2O was further introduced into the system, it was seen that the formation of CO2 increases, while CO (adsorbed and/or gas phase) decrease for all the catalysts. The dissociative adsorption of water on catalyst surface leads to the formation of OH groups, reflected by the increased peak areas of OH groups.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported that the WGSR occurs on the active sites at Pt/CeO2 interfaces. Different structures of the active sites have been proposed, including Ptδ+ – O – Ce4+ and Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+ 14. In this study, in situ AP-XPS shows that Ptδ+ and Ce4+ species are dominant on the Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst with a small fraction (~20%) of Pt0 and Ce3+ species after O2–H2 pretreatment. The O2–H2 pretreatment process also generates a large amount of OH groups on the surface, reflected by the O 1s spectra as shown in Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13. Therefore, Fig. 4a illustrates the structure of the active sites after O2–H2 pretreatment having the Ptδ+ species associated with the Ce4+–O framework surrounded by OH groups. In situ TIR spectroscopy measurements suggest that when CO is initially introduced into the system, the adsorbed CO molecules on the Pt sites (both Pt0 and Ptδ+) react with the surface OH groups and/or lattice O to form CO2 due to the high oxygen storage and release capacity of the CeO2 support. The observed O – C – O bands indicate that the dissociative reaction pathway on the Pt/CeO2 catalysts occurs with the formation of carboxyl (COOH*) and/or formate (HCOO*) intermediates. Compared to the lattice O, the surface OH groups provide an additional reaction pathway with a lower activation barrier for the formation of CO2 via the decomposition of COOH* intermediate, as proposed in previous studies14,40. As a result, the ratio of OH groups/lattice O obtained from in situ AP-XPS measurement decreases, while the ratio of adsorbed O species/lattice O increases due to the adsorption of CO and formation of O-containing intermediates (COOH*, HCOO*, etc.) (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). In the meantime, the consumed OH groups lead to the formation of oxygen vacancies. Consequently, the fractions of Pt0 and Ce3+ increase by ~10%. In the presence of CO, the structure of the active sites changes from Ptδ+ – O – Ce4+ to Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+, as shown in Fig. 4b. When H2O is introduced, the dissociation of water can help refill the oxygen vacancies by forming OH groups. Therefore, the ratio of OH group/lattice O increases. The occurred WGSR also leads to the increased peak area of CO2 in TIR spectra, while the peak areas of consumed OH groups and adsorbed CO (on both Pt0 and Ptδ+) decrease. As shown in Fig. 4c, since the reaction is limited by the activation of water on the oxygen vacancies, the formation of OH groups from H2O is slower than the consumption of OH groups by CO41. Thus, the increased number of Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+ sites leads to an increased fraction of Pt0 as observed in the AP-XPS analysis.

To better visualize the dynamic surface under reaction conditions, the size of each atom is optimized, which does not reflect the real scale. Red: oxygen; yellow: cerium; white: hydrogen; dark blue: oxidized Pt (Ptδ+); light blue: metallic Pt (Pt0); gray: carbon; V: oxygen vacancy. a The initial structure of active site (Ptδ+ – O – Ce4+ with the presence of OH groups) at Pt/CeO2 interface after O2-H2 pretreatment. b CO reacts with surface OH groups to form oxygen vacancy and metallic Pt (Pt0 – Ov – Ce3+). c Dissociation of water on the oxygen vacancy site and formation of CO2 and H2 products.

Similar to the Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst, the changes of surface species on the Pt/CeO2-cube and Pt/CeO2-oct catalysts follow the same trend. The differences between three catalysts are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1–3. After O2–H2 pretreatment, a larger fraction of metallic Pt on the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst was observed, compared to the cases of nanorods and nanocubes. This could be due to two factors, namely a) different surface area of CeO2 supports or b) the Pt-CeO2 interaction. As reported in a previous study using the same synthesis method, the specific surface areas are 87, 13, and 51 m2 g−1 for CeO2 nanorods, nanocubes, and octahedra, respectively22. The different specific surface areas may influence the dispersion of Pt nanoparticles on the CeO2 supports when the same Pt loading is used. AP-XPS and TIR measurements indicate that the oxidation state of Pt on CeO2 nanorods and nanocubes are almost the same under different treatments, despite them representing the two extremes in terms of surface area (87 and 13 m2 g−1, respectively). For example, a larger fraction of oxidized Pt is present after consecutive O2 and H2 pretreatment, while metallic Pt dominates on the CeO2 surface during the WGSR for the Pt supported on CeO2 nanorods and nanocubes. On the other hand, for the case of CeO2 octahedra whose surface area (51 m2 g−1) is between that of nanorods and nanocubes, metallic Pt is observed after O2-H2 pretreatment. While there is a lack of correlation between specific surface area and oxidation state of Pt, there is a clear correlation between the thermodynamic stability of most abundant facet in each nanoshape and their ability to stabilize Pt. It is well accepted that the CeO2(111) facet (present in octahedra) is the most thermodynamically stable surface, followed by CeO2(100), and CeO2(110)22,42,43,44,45. As a result, the weaker interaction between Ptδ+ and CeO2(111) surfaces, which may promote the reduction of Ptδ+ by H2 on CeO2 octahedra. In contrast, the stronger metal-support interaction of Ptδ+ with CeO2(110) and (100) surfaces results stabilization of these species and smaller changes in oxidation state of Pt on CeO2 nanorods and CeO2 nanocubes. This result is also consistent with the surface composition obtained from AP-XPS measurements. As shown in the Supplementary Table 4, a higher Pt/Ce ratio was observed for the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst compared to the other two catalysts, indicating that the dispersion of Pt on CeO2 octahedra surface differs from the other two catalysts. The higher dispersion/concentration of Pt on CeO2 octahedra surface further leads to the lower activity per active sites compared to the other two catalyst. As discussed below in experimental section, due to the complexity of the system and reconstruction of the Pt-CeO2 interfaces, it’s challenging to calculate the activity per site of the catalysts, but the rank of activity remains unchanged. That is: Pt/CeO2-rod > Pt/CeO2-cube > Pt/CeO2-oct.

In the presence of CO and H2O, the less significant changes of oxidation states of Pt and Ce, and OH group/lattice O ratio could be ascribed to the lower activity of Pt/CeO2-cube and Pt/CeO2-oct catalysts. Moreover, previous studies have proposed that the ionic species of Pt enhances the catalytic activity of Pt/CeO2 catalysts by weakening the Ce–O bonds and increasing the oxygen mobility14,46. Therefore, the catalytic performance of these catalysts follows the rank of the concentrations of ionic Pt species on CeO2 surfaces: Pt/CeO2-rod > Pt/CeO2-cube > Pt/CeO2-oct.

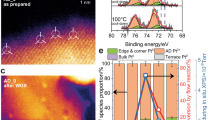

In situ environmental TEM (ETEM) measurements further demonstrate the dynamics of active sites under different conditions. As shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Movies 1–6, the fluxional behavior of surface atoms is observed for all the catalysts during O2–H2 pretreatment. The surface atoms are seen to disappear and reappear in the movies and the sequential images generated from the movies, indicating the surface atoms are highly active. In the supplementary movies, the surface atoms are more active after O2 pretreatment than after H2 pretreatment. Nevertheless, there are no obvious Pt nanoclusters/nanoparticles formed during O2–H2 pretreatment. The ETEM images taken from different spots on these catalysts after O2–H2 pretreatment are summarized in the Supplementary Figs. 17–19 and suggest the Pt species remain highly dispersed on CeO2 supports during the pretreatment.

The Supplementary Movies 1–9 show the dynamics of active sites on Pt/CeO2 catalysts under different conditions. a1 and a2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst after 0.40 Torr O2 pretreatment at 400 °C for 30 min. b1 and b2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst after 0.40 Torr H2 pretreatment at 300 °C for 30 min. c1 and c2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-rod catalyst under reaction conditions with 0.10 Torr CO and 0.20 Torr H2O at 300 °C. d1 and d2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst after 0.40 Torr O2 pretreatment at 400 °C for 30 min. e1 and e2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst after 0.40 Torr H2 pretreatment at 300 °C for 30 min. (f1 and f2) snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-cube catalyst under reaction conditions with 0.10 Torr CO and 0.20 Torr H2O at 300 °C. g1 and g2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst after 0.40 Torr O2 pretreatment at 400 °C for 30 min. h1 and h2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst after 0.40 Torr H2 pretreatment at 400 °C for 30 min. i1 and i2 snapshots of ETEM image of Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst under reaction conditions with 0.10 Torr CO and 0.20 Torr H2O at 300 °C. Scale bars are 2 nm. To minimize electron beam effect, the dynamics of catalyst were recorded after O2 and H2 pretreatment for 30 min. The dynamics of catalyst under reaction conditions were recorded after reactants were introduced into the system. The snapshots were selected when the structural reconstruction occurred. Therefore, 0 s and 10 s do not represent the 0 s of starting time and the 10 s of the reaction.

Under the reaction conditions (CO and H2O), the surface atoms remain dynamically mobile. With time, small nanoclusters are formed on the surface (see Supplementary Movies 7–9). To investigate the beam effect, a similar experiment was conducted on the sample without exposing it to the electron beam. In the presence of CO and H2O, the formation of small nanoclusters was observed after 90 min at 300 °C, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the structure of the active sites undergoes reconstruction during the WGSR. As discussed above, an increasing amount of Pt0 is formed on the defective CeO2 surface during the reaction. The large fraction of oxygen vacancies may promote the structural reconstruction by enhancing the mobility and agglomeration of the free Pt0 atoms to form small nanoclusters, leading to the reshaping of the Pt/CeO2 interfaces.

Conclusions

Here, by performing in situ spectroscopic measurements, we provide mechanistic insights into the dynamic nature of the active sites for the WGSR on well-defined Pt/CeO2 catalysts. For the Pt/CeO2-rod and Pt/CeO2-cube catalysts, the Ptδ+ – O – Ce4+ sites surrounded by OH groups dominate at Pt/CeO2 interfaces after O2–H2 pretreatment. During the WGSR, the surface OH groups react with CO to form CO2, leaving oxygen vacancies formed on the surface. Meanwhile, the associated Ptδ+ species are reduced to Pt0. Since the reaction is limited by the activation of H2O, the faster consumption of surface OH groups by CO molecules results in the increased concentration of surface vacancies and metallic Pt0 and thereby the structural reconstruction. For the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst, Pt0 dominates on the CeO2(111) surface after O2–H2 pretreatment. The WGSR reaction does not change the oxidation state of Pt, which remains unchanged in the metallic state, suggesting the same reaction mechanism on the Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst as the others. The high concentration of metallic Pt0 on Pt/CeO2-oct catalyst after pretreatment results in its lower catalytic activity. These observations may open various opportunities for designing catalytic systems with controlled activity and selectivity by extending the concept to other classes of metal-oxide interfaces.

Methods

Synthesis of CeO2 nanoshapes

CeO2 nanoparticles with rodlike, cubic and octahedral morphologies were synthesized by a hydrothermal method that has been reported in a previous study22. For CeO2 nanorods and nanocubes, 4.80 g sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 18 mL deionized (DI) water. After stirring for 30 min, 2 mL solution containing 0.434 g cerium nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O, Sigma-Aldrich) was added dropwise into the stirring NaOH solution. The resulting slurry was transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave after an additional 30 min stirring. After hydrothermal treatment at 90 and 180 °C for 24 h, respectively, CeO2 nanorods and nanocubes are obtained. For the synthesis of CeO2 octahedra, 0.008 g NaOH and 0.434 g Ce(NO3)3·6H2O were used, while the amount of DI water remained the same as for the synthesis of nanorods and nanocubes. The hydrothermal treatment temperature and time were 180 °C and 24 h. The resulting precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with DI water, and dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C overnight. Finally, the dried powder samples were calcined in a tube furnace at 400 °C for 4 h with a 20 mL min−1 flow of air and ramping rate of 1 °C min−1.

Synthesis of Pt/CeO2 catalysts

To obtain Pt/CeO2 catalysts, a chemical reduction method was used. Briefly, 0.10 mL chloroplatinic acid hexahydrate solution (H2PtCl6·6H2O, Sigma-Aldrich, 0.05 g/mL) was diluted by 20 mL DI water. After stirring for 30 min, 0.2 g CeO2 nanorods powder was added into the solution, giving a Pt loading of ~1 wt%. After stirring for another 2 h, 20 mL solution containing 0.03 mL hydrazine monohydrate (NH2NH2·H2O, Sigma-Aldrich) was slowly added into the mixture at room temperature. The resulting Pt/CeO2 nanorods catalyst was collected by centrifuge after stirring for 12 h, washed thoroughly with DI water, and dried at room temperature for 24 h. For the Pt/CeO2 nanocubes and octahedra, the synthetic procedure was the same as Pt/CeO2 nanorods. The obtained samples are labeled as Pt/CeO2-rod, Pt/CeO2-cube, and Pt/CeO2-oct, referring to the different supports.

Characterization

Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Rigaku SmartLab Universal Diffractometer at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials at Brookhaven National Laboratory was used to investigate the structure of Pt/CeO2 catalysts.

Ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (AP-XPS) was performed at the 23-ID-2 beamline (IOS) of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II)47. Photon energies of 1100 and 320 eV was used. The main chamber (base pressure 2.0 × 10−9 Torr) of the end-station was equipped with a differentially pumped hemispherical analyzer (Specs Phoibos 150 NAP). The Ce 3d photoemission line with the strongest Ce4+ feature at 916.9 eV was used for energy calibration of the AP-XPS signals. For sample pretreatment, 0.40 Torr oxygen (O2) was introduced, and the sample was heated to 400 °C for 30 min to remove any surface-bound carbon species. After O2 was pumped out, 0.40 Torr hydrogen (H2) was introduced to pre-reduce the sample at 300 °C for 30 min when the pressure reached ~5.0 × 10−8 Torr. For the WGSR, 0.25 Torr CO was introduced after the pressure of AP-XPS chamber reached ~5.0 × 10−8 Torr, and the sample was heated to 300 °C for 60 min, followed by introducing 0.50 Torr H2O for another 60 min. During all the experiments, a mass spectrometer was used to monitor the gas compositions in the main chamber. Peak fitting of XPS data was performed using CasaXPS peak fitting software, and fitting parameters are summarized in the Supplementary Tables 5–7.

In situ transmission infrared spectroscopy (TIR) was performed on a Bruker Vertex 80 V spectrometer. Powder sample was pressed on to a tungsten mesh (75% transparency, GoodFellow) to form a thin film. The samples were in situ pretreated at 400 °C under 0.40 Torr O2 for 30 min, followed by pretreatment at 300 °C under 0.40 Torr H2 for 30 min. The system was pumped down to vacuum condition (<1 × 10−5 Torr) before introducing gas. After pretreatment, a background spectrum of sample at 300 °C was collected by averaging 512 scans at 4 cm−1 resolution between 4000 and 800 cm−1. Then, a set of spectra as function of time were collected after 0.05 Torr CO was introduced into the chamber, followed by 0.10 Torr H2O was added into the system. The sample temperature was maintained at 300 °C during the data collection. To track the changes of IR spectra, the peak areas of different species were integrated for comparison. The peak area integration performed at 3703–3630, 2450–2274, 2244–2045, and 2044–1846 cm−1 correspond to OH group, gas phase CO2, gas phase CO and CO adsorption on oxidized Pt species (Pt – O), and CO adsorption on metallic Pt species (Pt0), respectively. The normalization of peak areas is obtained by comparing the peak area different species obtained at different time with the peak area obtained at 3 min. Therefore, for all the formed new species in the IR spectra, the normalized peak area is 1 at 3 min and it increases with time. For comparison, the consumed OH group in the presence of CO and during the WGSR, the negative value was used.

In situ environmental transmission electron microscopy (ETEM) was conducted on a FEI Titan 80-300 environmental transmission electron microscope. The samples were prepared by dispersing Pt/CeO2 powder in water, followed by deposition onto a nano-chip with through hole windows, which was then loaded into s DENSsolution Wildfire heating holder. After loading the sample into the ETEM, 0.40 Torr O2 was introduced into the chamber and the catalyst was pretreated in situ at 400 °C for 30 min. The catalyst was subsequently cooled to 300 °C and the O2 gas was pumped out. To minimize electron beam effects, the catalyst was imaged after pretreatment. Then, 0.40 Torr H2 was introduced into the chamber and the catalyst was reduced in situ at 300 °C for 30 min. After pumping out gas, the catalyst was imaged at 300 °C under vacuum conditions. To produce a water-gas-shift reaction conditions, 0.10 Torr CO and 0.20 Torr H2O were introduced to the chamber. The evolution of structural reconstruction was recorded and imaged under 300 °C in the presence of reactants.

Catalytic activity test

All the catalysts were evaluated in a flow reactor. 50 mg of sample was loaded into a quartz tube with an inner diameter of 4.0 mm. A stream of 50 mL min−1 O2 gas was passed over the sample, which was then heated to 400 °C. After 60 min, a stream of 15 vol% H2/Ar was introduced into the reactor with a flow rate of 100 mL min−1. The catalyst was reduced by H2 at 300 °C for 60 min. After pretreatment, the catalyst was cooled down to room temperature under 50 mL min-1 Ar flow. Then, a stream of 1 vol% CO and 2 vol% H2O balanced with Ar were introduced into the reactor with a total flow rate of 157 mL min−1, given a space velocity of 188,400 ml gcat−1 h−1. The temperature was gradually increased to 300 °C. At each temperature, the system was stabilized for 30 min to inject the gas into an Agilent 7890B gas-chromatography coupled with mass spectrometer (GC-MS) system equipped with a thermal conductivity detector. The CO conversion was calculated based on the concentration of CO and CO2 in the gas stream:

In situ ETEM indicates that the Pt species are highly dispersed on the CeO2 supports after O2 and H2 pretreatment. The catalysts show interface reconstruction under reaction conditions. The size of Pt nanoparticles changes with time. In addition, AP-XPS indicates that the concentration and dispersion of Pt on three different CeO2 supports are different. Therefore, the formation rates of CO2 and H2 on three different catalysts was calculated by comparing the concentration of formed H2 and CO2 with the total amount of Pt (1 wt%; 50 mg catalyst):

Since the AP-XPS results indicates that the concentration/dispersion of surface Pt on the CeO2 octahedra is much higher than that on the CeO2 nanorods and nanocubes. Therefore, the activity per surface sites (Pt-CeO2) of Pt/CeO2-oct may be much lower than that of Pt/CeO2-rod, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4c. However, due to the complexity of Pt/CeO2 interfacial structure as well as the structure reconstruction during the WGSR, it’s challenging to calculate the activity per site for three different catalysts. But the rank of activity per site on CeO2 supported Pt catalysts remains unchanged: Pt/CeO2-rod > Pt/CeO2-cube > Pt/CeO2-oct.

In order to investigate the thermodynamic equilibrium of the WGSR, the reaction was simulated in ASPEN Plus V10 (Gibbs reactor). A feed stream of CO and H2O with a ratio of 1: 2 was applied. Mole fractions of each compound in the feed and product with respect to the temperature of the reactor are shown in the supplementary information.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Pareek, A. et al. Insights into renewable hydrogen energy: Recent advances and prospects. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 3, 319–327 (2020).

Baraj, E., Ciahotný, K. & Hlinčík, T. The water gas shift reaction: Catalysts and reaction mechanism. Fuel 288, 119817 (2021).

Rodriguez, J. A., Liu, P., Hrbek, J., Evans, J. & Pérez, M. Water gas shift reaction on Cu and Au nanoparticles supported on CeO2 (111) and ZnO (000 ̄1): intrinsic activity and importance of support interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 1329–1332 (2007).

Cortright, R. D., Davda, R. & Dumesic, J. A. in Materials For Sustainable Energy: A Collection of Peer-Reviewed Research and Review Articles from Nature Publishing Group 289–292 (World Scientific, 2011).

Ovesen, C., Stoltze, P., Nørskov, J. & Campbell, C. A kinetic model of the water gas shift reaction. J. Catal. 134, 445–468 (1992).

Ovesen, C. et al. A microkinetic analysis of the water–gas shift reaction under industrial conditions. J. Catal. 158, 170–180 (1996).

Zhu, M. & Wachs, I. E. Iron-based catalysts for the high-temperature water–gas shift (HT-WGS) reaction: a review. ACS Catal. 6, 722–732 (2016).

Tanaka, Y., Utaka, T., Kikuchi, R., Sasaki, K. & Eguchi, K. Water gas shift reaction over Cu-based mixed oxides for CO removal from the reformed fuels. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 242, 287–295 (2003).

Ginés, M., Amadeo, N., Laborde, M. & Apesteguia, C. Activity and structure-sensitivity of the water-gas shift reaction over CuZnAl mixed oxide catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 131, 283–296 (1995).

Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Gold atoms stabilized on various supports catalyze the water–gas shift reaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 783–792 (2014).

Ratnasamy, C. & Wagner, J. P. Water gas shift catalysis. Catal. Rev. 51, 325–440 (2009).

Pal, D., Chand, R., Upadhyay, S. & Mishra, P. Performance of water gas shift reaction catalysts: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 93, 549–565 (2018).

Rodriguez, J. A., Senanayake, S. D., Stacchiola, D., Liu, P. & Hrbek, J. The activation of gold and the water–gas shift reaction: Insights from studies with model catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 773–782 (2014).

Reina, T. R. et al. Au and Pt Remain Unoxidized on a CeO2-Based Catalyst during the Water–Gas Shift Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 446–453 (2021).

Jacobs, G. & Davis, B. H. Low temperature water–gas shift: Applications of a modified SSITKA–DRIFTS method under conditions of H2 co-feeding over metal/ceria and related oxides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 333, 192–201 (2007).

Gonzalez, I. et al. A comparative study of the water gas shift reaction over platinum catalysts supported on CeO2, TiO2 and Ce-modified TiO2. Catal. Today 149, 372–379 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. Dynamic structure of active sites in ceria-supported Pt catalysts for the water gas shift reaction. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Dong, Z. et al. Revealing synergetic structural activation of a CuAu surface during water–gas shift reaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2120088119 (2022).

Tang, M. et al. Recent progresses on structural reconstruction of nanosized metal catalysts via controlled-atmosphere transmission electron microscopy: a review. ACS Catal. 10, 14419–14450 (2020).

Martín, A. J., Mitchell, S., Mondelli, C., Jaydev, S. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Unifying views on catalyst deactivation. Nat. Catal. 5, 854–866 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Highly efficient mesoporous Pd/CeO2 catalyst for low temperature CO oxidation especially under moisture condition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 158, 341–347 (2014).

Li, G., Wang, B. & Resasco, D. E. Water promotion (or inhibition) of condensation reactions depends on exposed cerium oxide catalyst facets. ACS Catal. 10, 5373–5382 (2020).

Agarwal, S. et al. Exposed surfaces on shape‐controlled ceria nanoparticles revealed through AC‐TEM and water–gas shift reactivity. ChemSusChem 6, 1898–1906 (2013).

Yang, C. et al. Surface faceting and reconstruction of ceria nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 375–379 (2017).

Spezzati, G. et al. CO oxidation by Pd supported on CeO2 (100) and CeO2 (111) facets. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 243, 36–46 (2019).

Pereira-Hernández, X. I. et al. Tuning Pt-CeO2 interactions by high-temperature vapor-phase synthesis for improved reducibility of lattice oxygen. Nat. Commun. 10, 1358 (2019).

Lykhach, Y. et al. Counting electrons on supported nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 15, 284–288 (2016).

Dvořák, F. et al. Creating single-atom Pt-ceria catalysts by surface step decoration. Nat. Commun. 7, 10801 (2016).

Luo, L., Engelhard, M. H., Shao, Y. & Wang, C. Revealing the dynamics of platinum nanoparticle catalysts on carbon in oxygen and water using environmental TEM. ACS Catal. 7, 7658–7664 (2017).

Michalak, W. D. et al. CO oxidation on PtSn nanoparticle catalysts occurs at the interface of Pt and Sn oxide domains formed under reaction conditions. J. Catal. 312, 17–25 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Adsorbate-driven reactive interfacial Pt-NiO1− x nanostructure formation on the Pt3Ni (111) alloy surface. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat3151 (2018).

Vovchok, D. et al. In situ characterization of mesoporous Co/CeO2 catalysts for the high-temperature water-gas shift. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 8998–9008 (2018).

Vayssilov, G. N., Mihaylov, M., Petkov, P. S., Hadjiivanov, K. I. & Neyman, K. M. Reassignment of the vibrational spectra of carbonates, formates, and related surface species on ceria: a combined density functional and infrared spectroscopy investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 23435–23454 (2011).

Binet, C., Daturi, M. & Lavalley, J.-C. IR study of polycrystalline ceria properties in oxidised and reduced states. Catal. Today 50, 207–225 (1999).

Zhang, Q. et al. In situ DRIFT spectroscopy insights into the reaction mechanism of CO and toluene co-oxidation over Pt-based catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 9, 4538–4551 (2019).

Kalamaras, C. M., Americanou, S. & Efstathiou, A. M. “Redox” vs “associative formate with–OH group regeneration” WGS reaction mechanism on Pt/CeO2: effect of platinum particle size. J. Catal. 279, 287–300 (2011).

Ding, K. et al. Identification of active sites in CO oxidation and water-gas shift over supported Pt catalysts. Science 350, 189–192 (2015).

Meunier, F. C. Relevance of IR spectroscopy of adsorbed CO for the characterization of heterogeneous catalysts containing isolated atoms. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 21810–21823 (2021).

Zhao, F. et al. Water-gas shift reaction on Ni–W–Ce catalysts: catalytic activity and structural characterization. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 2528–2538 (2014).

Liu, P. & Rodriguez, J. A. Water-gas-shift reaction on metal nanoparticles and surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 164705 (2007).

Bruix, A. et al. A new type of strong metal–support interaction and the production of H2 through the transformation of water on Pt/CeO2 (111) and Pt/CeO x/TiO2 (110) catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8968–8974 (2012).

Skorodumova, N., Baudin, M. & Hermansson, K. Surface properties of CeO 2 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 69, 075401 (2004).

Wu, Z., Li, M. & Overbury, S. H. On the structure dependence of CO oxidation over CeO2 nanocrystals with well-defined surface planes. J. Catal. 285, 61–73 (2012).

Wu, Z., Li, M., Mullins, D. R. & Overbury, S. H. Probing the surface sites of CeO2 nanocrystals with well-defined surface planes via methanol adsorption and desorption. Acs Catal. 2, 2224–2234 (2012).

Nolan, M. Hybrid density functional theory description of oxygen vacancies in the CeO2 (1 1 0) and (1 0 0) surfaces. Chem. Phys. Lett. 499, 126–130 (2010).

Fu, Q., Saltsburg, H. & Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Active nonmetallic Au and Pt species on ceria-based water-gas shift catalysts. Science 301, 935–938 (2003).

Waluyo, I. & Hunt, A. Ambient Pressure X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy at the IOS (23-ID-2) Beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source II. Synchrotron Radiat. N. 35, 31–38 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Science, under Award DE-SC002199. AP-XPS experiments were carried out at the 23-ID-2 (IOS) beamline of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, Brookhaven National Laboratory, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. Catalysts synthesis, characterization and performance tests were conducted using the Proximal Probes, Electron Microscopy, and Materials and Characterization Facilities at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials, supported by U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. The authors are thankful to Dr. Dmytro Nykypanchuk for his assistance in X-ray Diffraction measurement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.L. and J.A.B. conceived the project and designed the experiments. G.L. prepared the catalysts. D.Z. performed the ETEM experiments. G.L. and D.Z. analyzed the ETEM data. G.L. performed all the structural characterization and analyzed the data. G.L., T.H., Y.Y., A.R.H., J.A.B., A.H., and I.W. conducted AP-XPS experiments at 23-ID-2 beamline. G.L. and J.A.B. analyzed AP-XPS data. G.L. conducted catalytic activity test and analyzed the data. G.L. and J.A.B. co-wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jet-Sing Lee. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, G., Zakharov, D.N., Hu, T. et al. Tracking the dynamics of catalytic Pt/CeO2 active sites during water-gas-shift reaction. Commun Mater 5, 133 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00575-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00575-4