Abstract

Moiré superlattices consisting of two-dimensional materials have attracted immense attention because of emergent phenomena such as flat band-induced Mott insulating states and unconventional superconductivity. However, the effects of spin-orbit coupling on these materials have not yet been fully explored. Here, we show that single- and double-bilayer antimony honeycomb lattices, referred to as antimonene, form moiré superlattices on a Bi(111) substrate due to lattice mismatch. Scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) measurements reveal the presence of spectral peaks near the Fermi level, which are spatially modulated with the moiré period. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) combined with density functional theory calculations clarify the surface band structure with saddle points near the Fermi level, which allows us to attribute the observed STM spectral peaks to the van Hove singularity. Moreover, spin-resolved ARPES measurements reveal that the observed surface states are Rashba-type spin-polarized. The present work has significant implications in that Fermi surface instability and symmetry breaking may emerge at low temperatures, where the spin degree of freedom and electron correlation also play important roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of artificially stacked two-dimensional (2D) materials with moiré superlattices, which are induced by a lattice mismatch and/or a twist angle, has led to the development of new paradigms in condensed matter physics and materials science1,2,3. The successful fabrication of graphene/hexagonal boron nitride heterostructures and, more recently, twisted double layers of graphene have spawned a series of exciting discoveries, e.g., Hofstadter’s butterfly and fractal quantum Hall effect4,5,6, correlated insulating states and unconventional superconductivity7,8,9, charge order10, ferromagnetism and the quantum anomalous Hall effect11,12,13,14. The introduction of spin-orbit coupling (SOC) into moiré superlattices can lead to even richer emergent phenomena such as topological superconductivity, but these studies have been limited to transition metal dichalcogenides thus far14,15,16,17,18. The application of elemental 2D materials with strong SOCs may greatly expand the potential of moiré superlattices, but the exploration of such a possibility has been scarce thus far19.

Bi and Sb are heavy VA elements with strong atomistic SOC and hence important ingredients in topological materials. The most stable form of bulk crystals is the A7 rhombohedral crystal structure, which consists of covalently bonded buckled honeycomb 2D layers (conventionally called bilayers) stacked by weak interlayer bonding20,21,22. This feature makes Bi and Sb atomic layers promising 2D materials beyond graphene23,24,25. They were theoretically predicted to become 2D topological insulators (quantum spin Hall insulators), and their topological edge states were found experimentally26,27,28,29,30,31,32. They are also reported to be resilient against air exposure and chemical processes and thus can potentially be used for various practical applications23,24,33,34. Atomic layers of Bi and Sb are commonly referred to as bismuthene24,31 and antimonene23,25,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, while this nomenclature is not completely correct because they are buckled and do not includes double bonds in their lattices23. Bismuthene and antimonene can be formed on an adequate substrate by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)31,34,35,36,37, in some cases leading to black phosphorus-like puckered layers40,41.

Here, we show by scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) that single- and double-bilayer (BL) antimonene form moiré superlattices on a Bi(111) substrate due to lattice mismatch. They exhibit clear spectral peaks located near the Fermi level, which show distinctive behaviors regarding the moiré periodicity. While the peaks found for single-BL antimonene show only weak modulations in height, those for double-BL antimonene are split by ~100 mV and exhibit strong spatial modulations, suggesting localization due to the moiré superlattice. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) and spin-resolved ARPES (SARPES) combined with density functional theory (DFT) calculations clarify the presence of saddle points near the Fermi level. This allows us to identify the origin of the STM spectral peaks as the van Hove singularity. These surface states are found to be Rashba-type spin polarized. The present work has significant implications for demonstrating that Fermi surface instability and symmetry breaking may emerge at low temperatures, where the spin degree of freedom and electron correlation are intimately involved.

Results

Atomic structures: STM measurements

All the experiments were carried out in ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) chambers with a base pressure of ~1×10−10 mbar (see Methods). First, a Bi(111) thin film was grown on a clean Si(111) surface to 10 BLs by MBE41,42. For the ARPES/SARPES experiments with an imaging-type instrument (see below), Ge(111) substrates were used because of easiness of sample preparation. In this case, a 250 BL-thick Bi(111) film was grown on a clean Ge(111) surface43,44. These two recipes resulted in essentially the same Bi(111) surface structures and did not affect our conclusion. Here, we adopt the rhombohedral crystallographic notation to describe the plane index of the film20,21. The crystallinity of the prepared samples was confirmed with scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and low-energy electron diffraction (LEED). The surface of the Bi(111) film was then covered by 1–2 BL Sb (for LEED patterns, see Supplementary Information A). Since Bi(111) and Sb(111) bilayers share the same buckled honeycomb structure with similar lattice constants of 0.454 nm and 0.431 nm, respectively, a Sb(111) film could grow epitaxially on a Bi(111) film45,46. However, the lattice constant of the free-standing Sb bilayer (1BL antimonene), which is predicted to be 0.408–0.412 nm47,48, is significantly smaller than that of bulk Bi(111). This allows antimonene to grow nonepitaxially on Bi(111) and to form a moiré superlattice, which we indeed observe as follows.

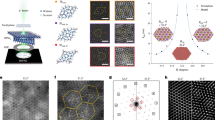

The main panel of Fig. 1a shows a representative STM image of a Bi(111) surface covered with more than 1 BL of Sb. The lower terrace in the image (Region I) features a triangular lattice structure, which is a moiré superlattice made of 1BL antimonene (1BL Sb) on a Bi(111) surface. Although this superlattice includes defects and local deformations, the presence of a well-defined periodicity is clear from its fast Fourier transform (FFT) image (inset of Fig. 1a). From repeated experiments with different surface regions and samples, we determined the moiré lattice constant to be 4.70 ± 0.30 nm (Supplementary Information B). On the upper terrace, there exists another region of the moiré superlattice with a longer periodicity (Region II). Since the height difference of ~0.4 nm between Regions I and II (Fig. 1b) is approximately equal to the height of the Sb bilayer (0.374 nm for bulk)20, Region II is identified as 2BL antimonene (2BL Sb) on a Bi(111) surface. Its moiré lattice constant was determined to be 6.59 ± 0.89 nm. The relatively large uncertainty is due to variations throughout different surface regions, presumably reflecting very small differences in energy. This 2BL Sb layer is bordered by another 1BL Sb layer (Region III), which is located in the upper-right corner of the image. Since they have almost the same topographic heights20, the boundary (indicated by the dashed line) is identified as the location of a buried atomic step of the Bi(111) surface. Our repeated experiments indicate that antimonene layers grow from the step edges of Bi(111) surfaces. They also show that 2BL Sb layers begin to grow before 1BL Sb layers fully cover the whole surface, but 1BL Sb layers occupy ~70% of the total area when the nominal coverage θ of Sb is 1.0 BL. The same trend also applies to the growth of 2BL Sb. Therefore, 1BL and 2BL Sb are the dominant phases for θ = 1.0 BL and 2.0 BL, respectively (Supplementary Information C).

a STM topographic image of 1BL and 2BL Sb grown on a Bi(111) film (Sample bias voltage: Vs = −1.0 V, Tunnelling current: It = 100 pA). Regions I and III correspond to 1BL Sb while Region II to 2BL Sb. The inset shows a FFT transform of a surface area belonging to Region I (scale bar: 0.3 nm−1). b Height profile along the dotted line in a. c, d Atomic resolution images of 1BL Sb c and 2BL Sb d on a Bi(111) surface. (Vs = −50 mV, It = 500 pA c, Vs = −50 mV, It = 300 pA d). The dashed parallelograms indicate the unit cells of the moiré superlattices. e The top and side views of the AA, AB and AC stacking sequences (blue spheres: Sb, red spheres: Bi). The vertical dashed lines shows the alignment of the Sb and Bi atoms.

Magnified STM images of 1BL and 2BL Sb are displayed in Figs. 1c, d, respectively, where the Sb atomic lattices are clearly resolved. The moiré unit cells are indicated by the dashed parallelograms. These features are ascribed to the surface topography because they are reproduced with different bias voltages (for example, see Fig. 2a, d below). We determined the lattice constant of 1BL Sb to be 0.415 ± 0.004 nm (Supplementary Information B). The fact that this value is greater than that of free antimonene (0.408–0.412 nm)47,48 is attributed to the tensile strain exerted from the Bi(111) surface. Likewise, the lattice constant of 2BL Sb was determined to be 0.423 ± 0.005 nm. This value is closer to that of bulk Sb(111) (0.431 nm) than that of 1BL Sb, suggesting lattice relaxation toward the bulk crystal. Combined with the moiré lattice constant determined above, the numbers of Bi and Sb atoms included in the moiré superlattice can be calculated. Assuming that the moiré unit cell consists of NBi × NBi Bi atoms and NSb × NSb Sb atoms per layer (NSb = NBi + 1), we find NBi = 10, NSb = 11 for 1BL Sb and NBi = 13–17, NSb = 14–18 for 2BL Sb. Our FFT analysis of STM images over an extended area reveals that there is no twisting between the moiré and Sb lattices on average (Supplementary Information B), although there are some local deviations due to deformations. Furthermore, Fig. 1c, d shows that the surface is divided into three characteristic regions in terms of topographic height. By comparing these observations to previous reports on related moiré superstructures49,50,51,52,53, we can safely assign them to the regions of the AA, AB, and AC stacking sequences (Fig. 1e). In the AA stacking, all atoms in the two layers are vertically overlapped, while only half of them are in the AB and AC stacking layers. Because of the significant buckling of the honeycomb lattice, the vertical distance between the overlapping atoms in the AB stacking is greater than that in the AA stacking. This leads to the lowering of the top layer by an attractive force. Conversely, in the AC stacking, the vertical distance between the overlapped atoms is smaller than that in the AA stacking. This leads to the raising of the top layer by a repulsive force. As a result of structural relaxation, the areas corresponding to the AB and AC stacking regions expand and shrink, respectively49,50. These features are clearly observed in Fig. 1c, d.

a STM topographic image of 1BL Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattices (Vs = -300 mV, It = 100 pA). The red (AA), blue (AB), and green (AC) squares show the locations for the STS measurements. b dI/dV spectra obtained at individual locations shown in a (broken lines) and their averages (solid lines) taken for the same stacking sequences. The red, blue, and green lines correspond to AA, AB, and AC stackings, respectively. The black solid line is the average of all the spectra. c (Right panel) 2D plot of color-coded dI/dV spectra of 1BL Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattices, which was taken along a straight line connecting the centers of AC, AB, AA, and AC regions (Vs = -300 mV, It = 100 pA). The vertical axis represents the lateral distance from the starting point. (Left panel) Topographic cross section along the measurement line. d–f Results for 2BL Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattices obtained in the same manner with the identical imaging parameters as in a–c.

Electronic structures: STS measurements

The electronic states of the moiré superlattices and their spatial modulations were investigated by scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (STS). First, for 1BL Sb on Bi(111), dI/dV spectra were taken at the center of the AA stacking region at five locations, and this process was repeated for the AB and AC stackings. The selected spectral sites are shown in the topographic STM image in Fig. 2a with red (AA), blue (AB), and green (AC) squares. Figure 2b shows the results of the STS measurements. The broken lines show individual dI/dV spectra, and the solid lines show the average values for the same stacking sequences, with their colors corresponding to those in Fig. 2a. The average of all the measured spectra are also shown by the solid black line. For all of these spectra, clear peak structures are noticeable near the zero bias voltage, with the full width at half maximum of 80 − 100 mV. The spectral peaks at the AB sites are particularly conspicuous, while those at the AA and AC sites are relatively suppressed. More detailed information was obtained through line spectroscopy; dI/dV spectra were taken along a straight line connecting the centers of the AC, AB, AA, and AC sites in this sequence. The right panel of Fig. 2c shows a 2D plot of color-coded dI/dV spectra as a function of bias voltage and lateral distance from the starting point. In the left panel of Fig. 2c, the topographic profile along the line is also shown. We find that the spectral peak is fixed at approximately 0 − 30 mV, while its intensity varies. This result strongly suggests the presence of delocalized states around the Fermi level that are weakly modulated by the moiré superlattice.

Figure 2d–f displays site-dependent dI/dV spectra for 2BL Sb on Bi(111) obtained in the same manner. The symbols and colors used in the figure follow the conventions of Fig. 2a–c. Figure 2e shows that spectral peaks are shifted from zero bias by 48 mV (AA site), -48 mV (AB site), and 144 mV (AC site) on average. The right panel of Fig. 2f shows that clear peak structures at approximately 40 mV and -100 mV are confined within the AA and AB regions, respectively. This result indicates the presence of multiple states near the Fermi level that are localized due to the moiré superlattice54.

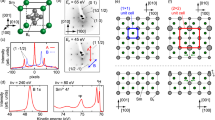

Electronic structures: ARPES/ SARPES measurements

To clarify the origin of the spectral peaks observed by STS, we performed laser-based high-resolution ARPES/SARPES measurements55. For simplicity, the data were analyzed based on the Brillouin zone of Bi(111) (Fig. 3a). First, we focused on the results for 1BL of Sb on a Bi(111) surface. Figure 3b shows a 2D plot of the ARPES intensity along the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{M}}}}\) direction and as a binding energy EB (dark: high, bright: low). We can recognize two bands, denoted as S1 and S2, starting from an EB ≅ 0.2 eV and dispersing upward. These bands disappear at approximately kx = 0.05–0.1 Å−1 by crossing the Fermi level but seem to disperse downward and reappear at approximately kx = 0.4–0.5 Å−1. The band dispersions determined from the plot are highlighted with red dashed curves. The signals are better visualized by the SARPES signal plotted for the range of -0.22 Å−1 < kx < +0.22 Å−1, where the intensity and the spin polarization in the y direction are indicated by brightness (dark: high, bright: low) and color (red: positive, blue: negative), respectively. The maximum spin polarization of the photoelectron is ~0.6. The spin polarizations of the S1 and S2 bands are opposite to each other and are antisymmetric with respect to kx = 0 Å−1. This is characteristic of Rashba-type spin-polarization, which will be discussed later. Figure 3c shows a similar 2D plot of the ARPES intensity along the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}\) (ky) direction. The S1 and S2 bands are also noticeable (highlighted with red dashed lines), but the S2 band reaches a local maximum near the Fermi level at approximately ky = 0.1- 0.15 Å−1 and then disperses downward. For better visibility, the same ARPES data in Fig. 3b, c are displayed in Fig. D2a, b without red dashed lines (Supplementary Information D).

a Bi(111) Brillouin zone and the high symmetry points \(\bar{\Gamma },\bar{{{\rm{M}}}},\bar{{{\rm{K}}}},\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}^{\prime}\). The green rectangle and the red square correspond to the areas for e and f, g, respectively. b 2D plot of ARPES intensity as a function of momentum kx along the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{M}}}}\) direction and as a binding energy EB. c The same plot as in b along the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}\) direction. The orange and blue rectangles correspond to those shown in Fig. 4a. d 2D plot of the SARPES signal as a function of momentum kx along the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{M}}}}\) direction and as a binding energy EB. The intensity and the spin polarization in the y direction are indicated by brightness (dark: high, bright: low) and color (red: positive, blue: negative), respectively. In b–d, the dispersions of S1 and S2 bands are indicated by the red dashed lines. e 2D plot of ARPES intensity measured near the Femi level (EB = 0.02 eV) in the kx–ky space, which gives the Fermi surface contour. The plot includes two data sets obtained in separate runs, which causes an apparent discontinuity at kx = 0.12 Å-1. The dashed lines indicate the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}\) directions. The red ellipses show the locations of the saddle points of the S2 band. f The same plot as in e in a larger momentum space, which was obtained with the imaging-type instrument. g 2D plot of SARPES intensity and spin polarization in the y direction measured near the Fermi level (EB = 0.03 eV) obtained with the imaging-type instrument. The intensity and the spin polarization in the y direction are plotted as in d. The Fermi surface contour of the S2 band determined from f is shown with red solid lines. The black and white dashed lines indicate the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{M}}}}\) directions.

Figure 3e shows the 2D plot of the ARPES intensity measured near the Femi level (EB = 0.02 eV) in the kx–ky space, which gives the Fermi surface contour. The central ring and a surrounding star-like structure are clearly noticeable and can be identified as the S1 and S2 bands, respectively. Notably, some parts of the S2 band appear very weak due to the anisotropic transfer during the photoemission process. By referring to the band dispersions in Fig. 3b-d, we can identify the areas indicated by the red ellipses as saddle points, where the S2 band takes a local maximum in the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}\) direction (k = 0.1–0.15 Å−1, EB ~ 0 eV; see Fig. 3c) and a local minimum in the orthogonal direction. This means that the van Hove singularity exists at the Fermi level56 and explains the origin of the zero bias peak for 1BL Sb/Bi(111) described above. To confirm this result, we also performed Fermi surface mapping with an imaging-type ARPES instrument, which allows us to access a larger momentum space at a faster speed (Fig. 3f)44. The acquired Femi surface well reproduces the features observed in Fig. 3e while better reflecting the sixfold symmetry expected from the C3 and time-reversal symmetries of the present system. We note that the band structure and the Fermi surface resemble those of Bi(111) and Sb(111) surfaces21,42,43,57,58, while saddle points are absent near the Fermi level in the latter cases.

Because of the space-inversion symmetry breaking at surface and strong SOC of Sb and Bi, Rashba-type spin polarization is expected. To confirm this, the distribution of spin polarization in momentum space was investigated with the same imaging-type instrument for 1BL Sb/Bi(111). Figure 3g shows a 2D plot of the SARPES intensity and spin polarization in the y direction (Py) measured near the Fermi level (EB = 0.03 eV). The observed signal is mostly attributed to the S2 band, the location of which is reproduced from Fig. 3f (red solid lines). Along the kx axis (white dashed line) and near the \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}\) lines at ± 60° to the kx axis (black dashed lines), Py is reversed when momentum is reversed with respect to the \(\bar{\Gamma }\) point (see also Supplementary Information D, Fig. D3), although their intensities are different. The variations in the intensity can be attributed to the fact that SARPES (more generally, ARPES) signal is strongly dependent on the transition matrix in the photoemission process. These results are consistent with Rashba-type spin polarization. We should note that the actual distribution of spin polarization deviates from the ideal vortical form, as indicated by the reversal of Py with respect to the black dashed lines. An analogous behavior was also predicted and observed for a clean Bi(111) surface with a giant Rashba splitting44,59,60.

We also performed ARPES/SARPES measurements of 2BL Sb on a Bi(111) surface (Supplementary Information D, Fig. D1). These results are nearly identical to those for 1BL Sb/Bi(111) (Fig. 3), but the observed ARPES signals are clearer than those for 1BL Sb/Bi(111). This difference may be attributed to the better moiré periodicity observed with STM (Fig. 1a).

Electronic structures: DFT calculations

Ab initio calculations of the electronic structure of Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattices are difficult because of the large number of heavy atoms involved within a moiré unit cell. To circumvent this problem, we carried out DFT calculations based on an epitaxial model consisting of 1BL Sb(111) on 5BL Bi(111) (Methods). Although this model does not include the effect of moiré periodicity, it can account for the overall band structures within the Bi(111) Brillouin zone. The structural relaxation within each stacking region in the actual moiré structure (Fig. 1c, d) rationalizes this treatment. Figure 4b shows the band diagram calculated for the epitaxial model with the AB stacking (Fig. 4a). The orange and blue rectangles correspond to the same marked areas in Fig. 3b,c. The sizes of the purple (light blue) circles represent the contributions of the top Sb (Bi) BL. Overall, the two bands starting from the \(\bar{\Gamma }\) point below the Fermi level (designated by the red dashed lines) are mostly derived from the top Sb BL, indicating that they can be preferentially detected in surface-sensitive STM and ARPES measurements. Judging from their dispersions, they can be assigned to the S1 and S2 bands identified above (Fig. 3b-d). Other bands with negligible contribution of Sb are assigned to the Bi(111) surface states on the back side of the model and thus are irrelevant to our experimental data. The same calculations for the AA and AC stackings give very similar band structures near the \(\bar{\Gamma }\) point and around the Fermi level (Supplementary Information E, Fig. E2b and Fig. E3b). Therefore, the presence of saddle points near the Fermi level is theoretically confirmed. The energies E-EF and momenta (kx, ky) of the saddle points are summarized in Table E1 of Supplementary Information E. These features are reflected in the projected density of states (PDOS) on the top Sb BL (Fig. 4g). The three sharp peaks indicated by the arrows at E – EF = 0.02 – 0.05 eV, corresponding to the AA, AB and AC stackings, are due to the van Hove singularity of the saddle point. The peak energies are very close to one another, reproducing the STS results shown in Fig. 2b,c. Assuming that the Fermi level is aligned near these peaks in real samples, we plot the Fermi surface contour of 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) with AB stacking at E – EF = -0.02 eV (Fig. 4c). The central rings and a surrounding star-like structure are consistent with the ARPES results (Fig. 3e, f). The spin structures at the Fermi surface calculated for this model is consistent with the SARPES plot in Fig. 3g (Supplementary Information E, Fig. E4).

a, d Atomic structure models for 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) (a) and 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) (d) with the AB stacking. The solid rectangles are the unit cells for calculations. b, e Band dispersions along the \(\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}-\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{{\rm{M}}}}\) direction calculated with the 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) model (b) and the 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) model (e) with AB stacking. The orange and blue rectangles correspond to those shown in Figs. 3b and 3c. The sizes of the purple (light blue) circles represent the contributions of the top Sb (Bi) BL. c, f Fermi surfaces (E – EF = -0.02 eV) calculated for the 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) model (c) and the 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) model with AB stacking (f). The colors represent the Fermi velocity (red: fast, blue: slow). The red squares correspond to the regions displayed in Fig. 3f, g. g, h Projected density of states (PDOS) on the top Sb BL calculated for the 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) model (g) and the 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) model (h).

The same calculations were also conducted based on an epitaxial model of 2BL Sb(111) on 5BL Bi(111) (Fig. 4d). The band structures and the Fermi surface (E – EF = -0.02 eV) obtained for the AB stack (Fig. 4e, f) resemble those obtained for the 1BL Sb(111) model (Fig. 4b, c) as well as the ARPES results (Supplementary Information D, Fig. D1). This is also the case for the AA and AC stackings (Supplementary Information E, Fig. E2d–f and Fig. E3d–f). However, the PDOSs around the Fermi level calculated for the AA, AB, and AC stacks exhibit more separated energies (Fig. 4h). Qualitatively, these results are in line with the STS data (Fig. 2e, f), but there are some clear discrepancies; e.g., the sharp peak at E – EF = 0 eV for the AC stacking has no corresponding structure in the STS data (Fig. 2e). This difference may be attributed to incomplete structural optimization of the 2BL Sb model, which results from our simplified models of fixing the locations of the Bi atom to those of the bulk Bi crystal (see Methods).

Discussion

We calculated the band structures of antimonene on a Bi(111) surface based on epitaxial models of 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) and 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111), which successfully explained our STM and ARPES data. Obviously, the adopted models are rather crude and do not include the effects of moiré modulations. The fact that all stacking sequencies AA, AB, and AC result in qualitatively identical electronic band structures may also explain the success of the present models. Experimentally, the 1BL-Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattice has nearly no spectral modulation (Fig. 2c), while the 2BL-Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattice has a modulation of 0.1 − 0.2 eV (Fig. 2f). Considering that the transfer integrals between the atomic orbitals in neighboring layers of Bi and Sb are 0.3 − 1.4 eV20, the influences of moiré superlattices are unexpectedly small. It suggests that it is not simply determined by the interlayer coupling strength.

Since Sb and Bi are isovalent, replacing Bi by Sb at the top layer simply leads to variations in electrostatic potential. It is thus possible to interpret the present S2 band, featuring the saddle points near the Fermi level, as a result of continuous deformation of the S2 band of a clean Bi(111) surface61. We also note that Bi is a topologically nontrivial semimetal and that its (111) surface states are protected43,62. Based on the same ground, the surface states of antimonene on Bi(111) can be topologically equivalent to those on Bi(111). In this case, the formation of an energy gap within the surface states is prohibited because it would violate the requirement that the bulk conduction and valence bands be continuously connected by surface states63,64. Indeed, our DFT calculations based on a moiré superlattice model indicate that there are no moiré-induced energy gaps at the zone boundary (see Supplementary Information F, Fig. F1). The result may be attributed to the topological protection discussed above. In this case, (high-order) van Hove singularities are predicted to emerge at the \(\bar{{{\rm{K}}}}\) point of the moiré Brillouin zone63, which calls for a future study.

Here we briefly mention the possibility of alloying of the top layer. It is widely known that Sb and Bi can form alloys with arbitrary ratios, and thus Sb and Bi atoms may be mixed to some extent. However, since the alloy formation does not change the A7 rhombohedral crystal structure of bulk65, it is highly likely to retain the buckled honeycomb lattice of antimonene. Since Sb and Bi are isovalent, the main effect of the mixing should be a simple potential modulation, which may slightly shift the band energy. Nevertheless, considering the good agreement between the band structure obtained by ARPES and that of our theoretical model, the alloying effect can be neglected for the current data set.

Finally, we discuss the implications of the findings in the present work. Generally, the presence of the van Hove singularity means a logarithmic divergence of the density of states and an enhancement of Coulomb interactions. Tuning the Fermi level to a van Hove singularity point can lead to a variety of symmetry-broken phases at low temperatures, such as unconventional superconductivity, charge density waves, ferromagnetism, charge order, and nematicity; these phases have been discussed within the context of high-Tc cuprates, graphene, kagome metals, etc56,66,67,68,69. Since the van Hove singularities in our systems are located close to the Fermi level, their tuning must be technically viable through gate voltage or molecular doping70. Among the possible low-temperature phases, superconductivity is the most likely because of the presence of Rashba-type spin polarization and the resulting spin-momentum locking63. In this case, the absence of space inversion symmetry should lead to a spin singlet-triplet mixed state71. We note that electron‒phonon coupling, which is responsible for superconductivity, is likely to be enhanced here, as discussed for granular Bi films72,73. Regarding 2BL Sb/Bi(111), moiré-induced electron confinement and enhanced electron correlation can further enrich the low-temperature physics beyond the simple van Hove singularity scenario. The inclusion of Rashba-type spin polarization in the moiré system is an open and intriguing problem. Experimentally, preparation of a high-quality sample with less structural defects and a better moiré periodicity would be essential, since it should strengthen the divergent behavior of the van Hove singularity. Thus, the present Sb/Bi(111) moiré superlattices will offer a new playground for investigating the role of the spin degree of freedom in van der Waals materials.

Methods

Sample preparation

The Si(111) substrates were cleaned by direct current heating at 1250 °C for 10 seconds. After repeating the cycle several times, 7\(\times\)7 clean surfaces were obtained. The Ge(111) substrates were cleaned by repeated Ar+ sputtering and annealing several times to obtain 2 × 1 surfaces. Both surfaces were confirmed by observing sharp LEED spots. Bi(111) films were then grown by MBE on Si(111)-7\(\times\)7 surfaces to 10 BLs or on Ge(111)-2 × 1 surfaces to 250 BLs at room temperature. To improve the flatness of the film, the Bi films were annealed at approximately 190 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, Sb was deposited on the Bi(111) surfaces at room temperature to form moiré antimonene. The crystallinity of the sample was improved by mild annealing at approximately 100 °C.

STM measurements

The STM measurements were conducted at 78 K and 4.6 K with a Nanonis controller Mimea BP5e. Topographic images were obtained in constant current mode. The lateral scale of the STM images was calibrated through observation of Bi(111) surfaces by assuming that the lattice constant is equivalent to that of a bulk crystal (0.454 nm). STS measurements were conducted with a built-in lock-in amplifier with a typical bias voltage modulation of 20 mV at 477 Hz.

ARPES measurements

ARPES and SARPES measurements were performed at National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) and at the Institute for Solid State Physics (ISSP), University of Tokyo. For the NIMS measurements, we employed a momentum microscope equipped with an imaging spin detector44,74. A 10.9-eV laser was used as the excitation light. For the measurements at the ISSP, the photoelectrons excited by a 6.994-eV laser were analyzed by a hemispherical photoelectron analyzer equipped with an ultralow-speed electron diffraction spin detector55. For both measurements, samples were prepared in situ. The sample temperature during the measurements was 30 K.

DFT calculations

To calculate the electronic band structures, we adopted epitaxial models of 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111) and 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111). The locations of the Bi atoms and those of the Sb atoms in the in-plane directions were fixed to those of the bulk Bi crystal. The out-of-plane Bi atom positions follow the structure for the Bi(111) thin film used in the literature61. Here, the Bi atom locations in the top Bi BL (adjacent to the Sb BLs) are modified, while the other Bi atoms follow the bulk Bi structure. In contrast, the locations of the Sb atoms in the out-of-plane direction were set equal to those at the centers of the AA, AB and AC stacking regions of the numerically optimized moiré superlattices (indicated by the red, blue and green circles, respectively, in Fig. E1; see Supplementary Information E). To optimize the 1BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111), we prepared a single 11 × 11 supercell of the Sb(111) BL on five vertically stacked 10 × 10 supercells of the Bi(111) BL. While the locations of the Bi atoms are fixed as in the Bi(111) thin film61, the locations of the Sb atoms are optimized by utilizing a neural network potential, PFP (without U) version 5.0.0, on Matlantis (https://matlantis.com/)75. Similarly, to optimize the 2BL Sb(111)/5BL Bi(111), we prepared two 14 × 14 supercells of the Sb BL on five 13 × 13 supercells of the Bi BL and optimized the positions of the Sb atoms.

The noncollinear DFT calculations for the epitaxial models are performed by OpenMX version 3.976,77,78,79 with the PBE exchange correlation functional and spin–orbit coupling. We use the 15 × 15 × 1 k-point grid in the first Brillouin zone for self-consistent field (SCF) calculations. After the SCF calculation, the density of states is obtained on a 256 × 256 × 1 k-point grid by the tetrahedron method. The energy cutoff is set to 100 or 200 Ry. The dependence of the band structure and density of states on the k-point grid and energy cutoff was examined to ensure convergence.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725–733 (2020).

Andrei, E. Y. & MacDonald, A. H. Graphene bilayers with a twist. Nat. Mater. 19, 1265–1275 (2020).

He, F. et al. Moiré patterns in 2D materials: a review. ACS Nano 15, 5944–5958 (2021).

Hunt, B. et al. Massive Dirac fermions and Hofstadter butterfly in a van der Waals heterostructure. Science 340, 1427–1430 (2013).

Dean, C. R. et al. Hofstadter’s butterfly and the fractal quantum Hall effect in moiré superlattices. Nature 497, 598–602 (2013).

Cheng, B. et al. Fractional and symmetry-broken chern insulators in tunable Moiré superlattices. Nano Lett. 19, 4321–4326 (2019).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43 (2018).

Lu, X. et al. Superconductors, orbital magnets and correlated states in magic-angle bilayer graphene. Nature 574, 653–657 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Charge order and broken rotational symmetry in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 573, 91–95 (2019).

Sharpe, A. L. et al. Emergent ferromagnetism near three-quarters filling in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 365, 605–608 (2019).

Serlin, M. et al. Intrinsic quantized anomalous Hall effect in a moiré heterostructure. Science 367, 900–903 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Tunable spin-polarized correlated states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 221–225 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Tunable correlated Chern insulator and ferromagnetism in a moiré superlattice. Nature 579, 56–61 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Correlated electronic phases in twisted bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 19, 861–866 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Hennighausen, Z. et al. Evidence of a purely electronic two-dimensional lattice at the interface of TMD/Bi2Se3 heterostructures. Nanoscale 11, 15929–15938 (2019).

Kezilebieke, S. et al. Moiré-Enabled Topological Superconductivity. Nano Lett. 22, 328–333 (2022).

Le Ster, M., Maerkl, T., Kowalczyk, P. J. & Brown, S. A. Moir\‘e patterns in van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 99, 075422 (2019).

Liu, Y. & Allen, R. E. Electronic structure of the semimetals Bi and Sb. Phys. Rev. B 52, 1566–1577 (1995).

Hofmann, P. The surfaces of bismuth: Structural and electronic properties. Prog. Surf. Sci. 81, 191–245 (2006).

Bian, G. et al. Survey of electronic structure of Bi and Sb thin films by first-principles calculations and photoemission measurements. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 128, 109–117 (2019).

Ares, P., Palacios, J. J., Abellán, G., Gómez-Herrero, J. & Zamora, F. Recent Progress on Antimonene: A New Bidimensional Material. Adv. Mater. 30, 1703771 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Advances of 2D bismuth in energy sciences. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 263–285 (2020).

Xue, C.-L. & Li, S.-C. Recent progress on antimonene: from theoretical calculation to epitaxial growth. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 60, SE0805 (2021).

Murakami, S. Quantum Spin Hall Effect and Enhanced Magnetic Response by Spin-Orbit Coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 236805 (2006).

Zhang, P., Liu, Z., Duan, W., Liu, F. & Wu, J. Topological and electronic transitions in a Sb(111) nanofilm: The interplay between quantum confinement and surface effect. Phys. Rev. B 85, 201410 (2012).

Chuang, F.-C. et al. Tunable topological electronic structures in Sb(111) bilayers: A first-principles study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 022424 (2013).

Drozdov, I. K. et al. One-dimensional topological edge states of bismuth bilayers. Nat. Phys. 10, 664–669 (2014).

Kim, S. H. et al. Topological phase transition and quantum spin Hall edge states of antimony few layers. Sci. Rep. 6, 33193 (2016).

Reis, F. et al. Bismuthene on a SiC substrate: A candidate for a high-temperature quantum spin Hall material. Science 357, 287–290 (2017).

Peng, L. et al. Visualizing topological edge states of single and double bilayer Bi supported on multibilayer Bi(111) films. Phys. Rev. B 98, 245108 (2018).

Ares, P. et al. Mechanical Isolation of Highly Stable Antimonene under Ambient Conditions. Adv. Mater. 28, 6332–6336 (2016).

Wu, X. et al. Epitaxial Growth and Air-Stability of Monolayer Antimonene on PdTe2. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605407 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Epitaxial Growth of Flat Antimonene Monolayer: A New Honeycomb Analogue of Graphene. Nano Lett. 18, 2133–2139 (2018).

Fortin-Deschênes, M. et al. Synthesis of Antimonene on Germanium. Nano Lett. 17, 4970–4975 (2017).

Ji, J. et al. Two-dimensional antimonene single crystals grown by van der Waals epitaxy. Nat. Commun. 7, 13352 (2016).

Zhang, S., Yan, Z., Li, Y., Chen, Z. & Zeng, H. Atomically Thin Arsenene and Antimonene: Semimetal–Semiconductor and Indirect–Direct Band-Gap Transitions. Angew. Chem. Int. 54, 3112–3115 (2015).

Aktürk, O. Ü., Özçelik, V. O. & Ciraci, S. Single-layer crystalline phases of antimony: Antimonenes. Phys. Rev. B 91, 235446 (2015).

Zhang, P. et al. Absence of topological β-antimonene and growth of α-antimonene on noble metal Ag(111) and Cu(111) surfaces. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 074002 (2022).

Nagao, T. et al. Nanofilm Allotrope and Phase Transformation of Ultrathin Bi Film on Si(111)-7×7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 105501 (2004).

Hirahara, T. et al. Role of Spin-Orbit Coupling and Hybridization Effects in the Electronic Structure of Ultrathin Bi Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 146803 (2006).

Ito, S. et al. Proving Nontrivial Topology of Pure Bismuth by Quantum Confinement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 236402 (2016).

Yaji, K. & Tsuda, S. Visualization of spin-polarized electronic states by imaging-type spin resolved photoemission microscopy. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. Meth. 4, 2328206 (2024).

Takayama, A., Sato, T., Souma, S. & Takahashi, T. Rashba effect in antimony and bismuth studied by spin-resolved ARPES. N. J. Phys. 16, 055004 (2014).

Abe, H., Iwasawa, D., Imamura, M., Takahashi, K. & Takayama, A. Electronic structure of Sb ultrathin film on Bi(111) with large lattice mismatch. AIP Adv. 13, 055303 (2023).

Wang, G., Pandey, R. & Karna, S. P. Atomically Thin Group V Elemental Films: Theoretical Investigations of Antimonene Allotropes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 11490–11496 (2015).

Liu, G., Gao, Z. & Zhou, J. Strain effects on the mechanical properties of Group-V monolayers with buckled honeycomb structures. Phys. E Low. Dimens 112, 59–65 (2019).

An, Q., Moutanabbir, O. & Guo, H. Moiré patterns of twisted bilayer antimonene and their structural and electronic transition. Nanoscale 13, 13427–13436 (2021).

Naik, M. H. & Jain, M. Ultraflatbands and Shear Solitons in Moiré Patterns of Twisted Bilayer Transition Metal Dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 266401 (2018).

Li, E. et al. Lattice reconstruction induced multiple ultra-flat bands in twisted bilayer WSe2. Nat. Commun. 12, 5601 (2021).

Liu, B. et al. Moiré Pattern Formation in Epitaxial Growth on a Covalent Substrate: Sb on InSb(111)A. Nano Lett. 23, 3189–3195 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Imaging moiré flat bands in three-dimensional reconstructed WSe2/WS2 superlattices. Nat. Mater. 20, 945–950 (2021).

Pan, Y. et al. Quantum-Confined Electronic States Arising from the Moiré Pattern of MoS2–WSe2 Heterobilayers. Nano Lett. 18, 1849–1855 (2018).

Yaji, K. et al. High-resolution three-dimensional spin- and angle-resolved photoelectron spectrometer using vacuum ultraviolet laser light. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 053111 (2016).

Markiewicz, R. S. A survey of the Van Hove scenario for high-tc superconductivity with special emphasis on pseudogaps and striped phases. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 58, 1179–1310 (1997).

Sugawara, K. et al. Fermi Surface and Anisotropic Spin-Orbit Coupling of Sb(111) Studied by Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 046411 (2006).

Bian, G., Wang, X., Liu, Y., Miller, T. & Chiang, T. C. Interfacial Protection of Topological Surface States in Ultrathin Sb Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 176401 (2012).

Saito, K., Sawahata, H., Komine, T. & Aono, T. Tight-binding theory of surface spin states on bismuth thin films. Phys. Rev. B 93 (2016).

Randeria, M. T. et al. Ferroelectric quantum Hall phase revealed by visualizing Landau level wavefunction interference. Nat. Phys. 14, 796–800 (2018).

Du, H. et al. Surface Landau levels and spin states in bismuth (111) ultrathin films. Nat. Commun. 7, 10814 (2016).

Ohtsubo, Y. et al. Non-trivial surface-band dispersion on Bi(111). N. J. Phys. 15, 033041 (2013).

Wang, T., Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Moiré Surface States and Enhanced Superconductivity in Topological Insulators. Phys. Rev. X 11, 021024 (2021).

Cano, J., Fang, S., Pixley, J. H. & Wilson, J. H. Moiré superlattice on the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 103, 155157 (2021).

Hsieh, D. et al. A topological Dirac insulator in a quantum spin Hall phase. Nature 452, 970–974 (2008).

Kiesel, M. L., Platt, C., Hanke, W., Abanin, D. A. & Thomale, R. Competing many-body instabilities and unconventional superconductivity in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 86, 020507 (2012).

Toyama, H. et al. Two-Dimensional Superconductivity of Ca-Intercalated Graphene on SiC: Vital Role of the Interface between Monolayer Graphene and the Substrate. ACS Nano 16, 3582–3592 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. A unique van Hove singularity in kagome superconductor CsV3-xTaxSb5 with enhanced superconductivity. Nat. Commun. 14, 3819 (2023).

Zhou, H., Xie, T., Taniguchi, T., Watanabe, K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity in rhombohedral trilayer graphene. Nature 598, 434–438 (2021).

Yoshizawa, S. et al. Controlled modification of superconductivity in epitaxial atomic layer–organic molecule heterostructures. Nano Lett. 17, 2287–2293 (2017).

Fujimoto, S. Electron Correlation and Pairing States in Superconductors without Inversion. Symmetry. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 76, 051008 (2007).

Gandhi, A. C. et al. Strong electron-phonon coupling in superconducting bismuth nanoparticles. APL Mater. 7 (2019).

Weitzel, B. & Micklitz, H. Superconductivity in granular systems built from well-defined rhombohedral Bi-clusters: Evidence for Bi-surface superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 385–388 (1991).

Yaji, K. & Tsuda, S. Development of a photoemission microscopy apparatus using a vacuum ultraviolet laser. e-J. Surf. Sci. Nanotechnol. 22, 46 (2023).

Takamoto, S. et al. Towards universal neural network potential for material discovery applicable to arbitrary combination of 45 elements. Nat. Commun. 13, 2991 (2022).

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155108 (2003).

Ozaki, T. & Kino, H. Numerical atomic basis orbitals from H to Kr. Phys. Rev. B 69, 195113 (2004).

Ozaki, T. & Kino, H. Efficient projector expansion for the ab initio LCAO method. Phys. Rev. B 72, 045121 (2005).

Lejaeghere, K. et al. Reproducibility in density functional theory calculations of solids. Science 351, aad3000 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Yoshizawa, F. Arai, S. Takezawa, H. Tanaka, A. Harasawa, and T. Iimori for their technical support during the STM and ARPES experiments. The computation in this work has been partly done using the facilities of the Super-computer Center, the Institute for Solid State Physics, the University of Tokyo. This work was supported financially by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. 20H05621, 22H01961, 20K15133, 22H01183, 23H03818, 23H04524), the World Premier International Research Center (WPI) Initiative on Materials Nanoarchitectonics, MEXT, Japan and the Innovative Science and Technology Initiative for Security Grant Number JPJ004596, ATLA, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N. and T.U. conceived the experiment, and T.N., T.U., K.Y. and Y.Y. wrote the manuscript. T.N., R.N. and W.Q. carried out the STM measurements, and T.N. analyzed the data. T.N., K.Y., Y.F., K.K., and R.M. carried out (S)ARPES measurements at ISSS under the supervision of T.K. Y.C., K.Y., and S.T. carried out (S)ARPES measurements at NIMS. K.Y. and S.T. analyzed the ARPES/SARPES data. Y.Y. performed the DFT calculations. All the authors discussed the results and contributed to finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Baojie Feng and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Dawei Shen and Aldo Isidori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, T., Chen, Y., Nemoto, R. et al. Moiré superlattices of antimonene on a Bi(111) substrate with van Hove singularity and Rashba-type spin polarization. Commun Mater 5, 167 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00615-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00615-z