Abstract

Surprisingly, topological metamaterials became a frontier topic in wave physics. What began as a curiosity driven undertaking in condensed matter physics, evolved in serious possibilities to provide topologically resilient guiding of light, sound and vibrations. Topological defects, in the form of disclinations, dislocations, vortices, etc., have capitalized on man-made structures to demonstrate their wave-confining capabilities. In this report, we discuss topological edge and disclination states in valley Hall sonic lattices. A prime meta-constituent is the three-legged rod or tripod as its mere rotation enables spatial symmetry breaking. For the most part, this complicated unit is numerically treated with commercially available finite element solvers. Here, we derive the structure factor for plane wave expansions and a null-field method in combination with a multiple scattering theory to study both valley edge and disclination states. We showcase how this method enables rapid evaluation of both spatial and spectral properties related to valley topological sound wave physics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological defects are local obstructions or kinks in an order parameter field that cannot be rearranged or continuously deformed to reestablish a flawless order. Typically, these defects feature a core where the order is disrupted and an outer zone with slowly varying variables1,2. We categorize defects based on the type of symmetry they break; for example, disclinations and dislocations break rotational and translational lattice symmetries, respectively, and are commonly found in natural systems. Other examples include grain boundaries in polycrystalline graphene3 and topological vortices binding Majorana bound states in topological superconductors4. In various physical systems, such as superfluids and topological superconductors, defects manifest as vortices resistant to destruction through continuous deformation of the order parameter4,5. For instance, a singular vortex carries a quantized magnetic flux characterized by a real-space winding number, akin to the non-zero Berry phase in nontrivial topological insulators. The Jackiw-Rossi model, originally formulated in quantum field theory and subsequently applied to graphene, illustrates how a zero-mode can bind to the vortex core, leading to a topological zero-energy state. Gao et al. took an acoustic approach toward this type of topological vortex defect at which a sonic zero-mode is pinned6,7. Using steel bolts on a plate arranged in a honeycomb pattern, established the basis for a Kekulé-distorted mechanical vortex implementation through flexural mode vibrations8. At higher MHz frequencies a similar approach has been implemented9. Through femtosecond laser direct writing to create waveguide lattices and electron-beam lithography to textured triangular perforations in a silicon layer, near-infrared topological zero-modes and a Dirac-vortex topological-cavity surface-emitting laser at telecommunication wavelengths, respectively, were successfully implemented10,11,12.

Recent observations reveal fractional charges trapped at disclinations lacking rotation symmetry in topological crystalline insulators. Experiments with microwave metamaterials and photonic crystals have reported fractional charges in units of e/4 and e/6, respectively13,14. In the absence of fractional charges, engineered disclinations in acoustic lattices with topological midgap states protected by chiral symmetry have been demonstrated15. Additionally, topological valley-Hall phases have been incorporated with man-made disclinations using both photonic and elastic configurations16,17. Dislocations, as mentioned earlier, are topological defects that persist due to the conservation of the Burgers vector. Edge dislocations run perpendicular, while screw dislocations run parallel to their Burgers vector. Lattice dislocations of the screw type in weak 3D topological insulators have been shown to host gapless helical modes similar to those in a 2D quantum spin Hall insulator18. Acoustic experiments using 3D printing and a cut-and-glue approach have provided evidence of this bulk-dislocation correspondence19,20. Finally, planar defects such as domain walls, analogous to grain boundaries, have been synthesized in intersecting sonic lattices, flanking a topological corner excitation21.

In this computational contribution, we employ the null-field method22,23,24 to study the acoustic interplay in lattices used to analyse topological properties. In the context of valley contrasting physics25,26, we investigate lattices made of the well-known three legged rods (TLRs) or tripods27,28, as their mere rotation breaks the C3ν symmetry, lifts the Dirac degeneracy and is responsible for a wealth valley-scattering related wave physics29,30. Yet, despite its ubiquity in topological studies, this unit remains a challenging object using standard computational tools and is evidently mostly treated using commercially available finite-element solvers. We show that multiple scattering techniques (MSTs) in combination with the null-field method, display remarkable agreement with COMSOL predictions comprising edge states along a valley sonic crystal. In this regard, we showcase the structure factor for such a TLR and discuss the necessity to employ smooth boundaries in our null-field approach to reach convergence of the scattered field and the transmitted wave. Likewise, we broaden the application to topological crystalline insulators where topological disclination defects are analysed, showcasing how the standard approach of multiple scattering extended with the null-field method, efficiently tackles contemporary problems in condensed matter and wave physics.

Results and Discussion

Scattering problem for an isolated TLR

We aim at deriving a wave scattering formalism that enables us to study complex acoustic interaction among TLRs in a periodic lattice. To begin, we consider a perfectly rigid isolated TLR and solve the acoustic scattering problem of such sound-hard rod by applying the Null-field method. This approach was first devised by Waterman to solve electromagnetic scattering problems22,31 and adapted later for problems in acoustics23,24, and elastodynamics32,33. The two-dimensional null-field equations are especially useful when the T-matrix for a single rod whose cross-section deviates from a circle is considered. The method applies the Green’s theorem to express the incident and the scattered waves as a boundary integral in terms of the 2D free-space Green’s function and the total pressure field on the surface S of the rod. Since the incident and scattered fields admit series expansions in terms of cylindrical wave functions, and a suitable set of expansion functions can be chosen to represents the total pressure field on S, a matrix relation of the form \({{\mathsf{A}}}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}={\mathsf{T}}\cdot {{\mathsf{A}}}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\) is obtained, where \({{\mathsf{A}}}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\,({{\mathsf{A}}}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}})\) is a vector of coefficients in the expansion of the scattered (incident) field and \({\mathsf{T}}\) is the T-matrix. We start computing the pressure field scattered by an isolated three-legged rod (TLR) having the cross section displayed in Fig. 1a, when irradiated by means of point sources uniformly distributed around it. As we detail in the Method section, we adapt the T-matrix formulation for sound-hard obstacles to incident and scattered pressure fields that are expanded in terms of cylindrical wave-functions as \({P}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)={\sum }_{q = -\infty }^{\infty }{A}_{q}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}{{{{\rm{J}}}}}_{q}\left(kr\right){{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}q\theta }\) and \({P}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)={\sum }_{q = -\infty }^{\infty }{A}_{q}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{q}\left(kr\right){{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}q\theta }\), respectively24. On this basis, the T-matrix can be incorporated directly into the standard MST to compute the total field scattered by a 2D arrangement of three-legged rods. Moreover, as additionally detailed in the Method section, to avoid the numerical instability that affects the null-field method when applied to the high aspect ratio TLR, we employ a rod with smooth boundaries (continuous line in Fig. 1a) in our null-field approach. We emphasize that the curvy TLR considered in our work is an approximate model of the actual TLR that preserves its C3 symmetry and cross-section area. It is a simple model, devised to reduce the aspect ratio of the TLR and thus improve the convergence of the Null-field method. Moreover, the analytical expressions of its smooth boundary (made of circular arcs) facilitates the computation of the T matrix. The pressure field Psc scattered by a single TLR is determined for any incident wave by means of the relation \({A}_{q}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}={\sum }_{s}{{{{\rm{T}}}}}_{qs}{A}_{s}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\). Using point sources as the incident field, the coefficients \({A}_{s}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\) are given in the Method section. For comparison, by utilizing a widely used commercial finite-element-method solver we are able to implement the exact geometry or a TLR, i.e., the rod with all its sharp edges as illustrated. The acoustic response of an isolated TLR to the field irradiated by three uniformly distributed point sources is presented in Fig. 1b where the spatial distribution of the scattered pressure field is in good agreement with COMSOL simulations.

a Cross sections of both the TLR (dashed line) and the rod with smoother boundary (continuous line) used for the null-field method computations. The cross section area of both rods is approximately the same. The length d = 0.85 cm, width h = 0.3 cm and height h0 = 0.16 cm. The radius of curvature of the larger and smaller circular arcs of the smoother boundary are \({{{{\rm{R}}}}}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}=d\sqrt{3}-{{{{\rm{h}}}}}_{0}/2\) and \(d/\cos \left(\alpha \right)\), \(\alpha =\arctan \left({{{{\rm{h}}}}}_{0}/2d\right)\), respectively. b The scattered field computed through the Null-field method and finite element simulations (COMSOL), respectively. The incoming field is realized by three point sources (white stars) at (in polar coordinates) (2d, π/6), \(\left(2d,5\pi /6\right)\) and (2d, 3π/2), with origin at O = (0, 0), the center of the TLR.

Topologically protected edge waves

To take this comparison one step further, next, we examine valley-edge states propagating along the interface among two sonic lattices with different symmetry-broken geometries. As seen in Fig. 2a, such interface is accomplished by separating lattices with both upright and upside-down TLRs. In both setups the C3 symmetry is preserved while the mirror symmetry is broken due to the TLRs orientation. A detailed investigation conducted by Z. Zhang et al.27 demonstrated that such interface supports topologically protected valley edge states that fall within the bulk band gap. According to their experimental data, when sound is excited inside the band gap, the pressure field remains localized in the vicinity of the interface between the two topological insulators (TIs) and decay exponentially away from it. Here, we use the MST and the T-matrix method to investigate the transmission characteristics. Generally speaking, the scattering environment consists of N0-TLRs located at Rα, with α = 1, 2, …, N0. The rods are surrounded by air with density ρ0 and speed of sound c. When sound, emanating a single point source P0, or multiple thereof, impinges the cluster of TLRs, the total pressure is given by P = P0 + Psc, where Psc is the total scattered field from all individual α-rods. At a given position r, in polar coordinates \(\left(r,\theta \right)\), we have

where Hq is the q-th order Hankel function of the first kind, k = ω/c is the wavenumber and \(\left({r}_{\alpha },{\theta }_{\alpha }\right)\) are the polar coordinates in the reference frame located in the center of the α-cylinders, i.e., rα = r − Rα. Since P0 is known, \({\left({A}_{\alpha }\right)}_{q}\) are the coefficients to be determined (Method). In Fig. 2b we compute the transmission spectra of the topological insulator under study by means of the expression \(20{\log }_{10}\left({P}_{{{{\rm{out}}}}}/{P}_{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\right)\), where Pin and Pout represent the averaged input and output pressure amplitudes, computed at the red points in Fig. 2a. The results show that a significant portion of the edge state intensity is transmitted across the nontrivial interface. Moreover, it is seen that the intensity grows with frequency towards the upper edge of the bulk band gap. The transmission spectra display good agreement among our MST and COMSOL simulations. Further, along the red dashed line in Fig. 2a, we also compare our approach with COMSOL simulation to verify its capability to capture the state localization. As depicted in Fig. 2c, at the mid-gap frequency of f = 7500 Hz, it is not only seen that the edge state is tightly confined, moreover a good agreement among the two techniques is unequivocally shown. Generally speaking, the results clearly indicate how sound exponentially decays away from the interface along which the topological confinement occurs. Specifically, upon inspecting the relative difference among the results from the two methods in terms of the data from COMSOL simulations, we obtain a mean difference of 0.035 (3,5%) and one of 0.042 (4.2%) for the pressure amplitude and the transmission spectrum across the topological band gap, respectively.

a Schematic of the interface separating two TIs with different symmetry-broken geometries, i.e., a triangular lattice with upright and upside down configurations of TLRs (lattice constant a = 2.17 cm). The equidistant red dots mark the sites from where the average pressure amplitudes have been evaluated. b Computed transmission spectra of topological edge states along the said interface using MST and COMSOL simulations. The gray-shaded region indicates the topological band gap. c Pressure amplitude profile along the red dashed line in (a) at the frequency f = 7500 Hz.

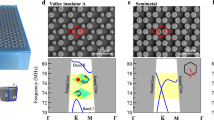

Topological valley disclination

In what follows, we investigate the transmission of sound across a disclination-type topological defect that is embedded within a valley-contrasting lattice. To create such defect, we employ Volterra’s cut-and-glue approach from a finite hexagonal flake by cropping out a π/3 sector, after which the free edges are reattached to form a pentagonal quasi crystal as shown in Fig. 3a. Specifically, the physical space is uniformly deformed in the angular dimension, \({\theta }^{{\prime} }=-\pi +1.2\left(\pi +\theta \right)\), to let the remaining lattice occupy the entire space. Meanwhile, the three-legged rods rotate in pace with the space distortion, forming a topological interface at the cut-and-glue line. We demonstrate that the existence of the distorted interface states can be explained by the real-space Wannier centers and the topological charge caused by the filling anomaly34. To be specific, the single Wannier center is located at the Wyckoff position b in the proposed structure as shown in the left-top panel of Fig. 3a. The distributions of the Wannier centers in the finite structure before distortion are also illustrated. Once we cut and glue the finite structure, the distributions of the Wannier centers along the interface are different from those in the bulk (bottom panel of Fig. 3a). The filling anomaly and the calculated topological charge as marked in the enlarged view support the topological sound propagation along the distorted interface. Furthermore, we extend the standard plane wave expansion (PWE) method by deriving a structure factor representing the TLRs as detailed in the method section. With this, we are able to map out the spectral width of the topological band gaps pertaining to the spatial lattice distortion shown in the right-top panel of Fig. 3a, illustrating its variation around the disclination. In Fig. 3b we use MST and the T-matrix method to compute the pressure amplitude spectrum at the bulk, the output and at the disclination (taking the average pressure amplitude over three positions). The incoming field is emitted by a point source located at the center of the crystal. In contrast with the pronounced intensity dip in the bulk, the spectrum shows a high transmission along the disclination for frequencies falling within the gap. In addition, Fig. 3c displays the spatial distribution of the pressure field at frequencies outside and inside the gapped spectrum, showing that no bulk leakage is present for waves confined and propagating along the disclination, beyond which sound is able emanate the quasicrystal into free space.

a Distributions of the Wannier centers (blue dots) before and after the creation of the disclination-type topological defect, and Spatial distribution of the first band gap through a continuous lattice distortion, obtained through the PWE method. A disclination interface (white stripe) connects the quasicrystal with the output (star). The cyan diamond indicates the location of the point source used for the MST computations and COMSOL simulations in panels (b–d). b Transmission spectrum of the pressure amplitude averaged over the black dots along the disclination, evaluated at the output (star) and within the bulk (square). The bulk band gap predicted from PWE computations in (a) is marked in gray. c, d Spatial distribution of the pressure field emitted by the point source for frequencies outside and inside the bulk gap in (b) using MST and from COMSOL simulations, respectively.

Conclusions

We employed a semi-numerical approach comprising three-legged rods to study valley-contrasting physics using sonic lattices. Using perfectly rigid materials, we derived an exact structure factor as well as an approximative scattering matrix for such widely used acoustic element in the field of topological metamaterials. We discussed how the results of our approach are in very good agreement with commercially available finite-element solvers, making our approach a potentially interesting tool. Specifically, we showed how distorted lattices are able to guide waves along topological destinations, beyond they can be probed by free-space measurements techniques.

Methods

The Null-field method

We depart from the boundary integral representation obtained by Martin24 for the incident and the scattered fields when a sound-hard obstacle is analysed. For a rigid rod whose cross section is bound by a smooth closed curve S, the integral equations lead to (in our notation)

for the incident field inside the rod, and

for the scattered field outside the rod, where P = Pin + Psc and G0 is the 2D free-space Green’s function. For a scalar function u, ∂u/∂n = n ⋅ ∇ u is the directional derivative along a unit normal vector n at the point \(\left({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)\in {{{\rm{S}}}}\); n is pointed outward from the curve S. The origin O = (0, 0) of the polar coordinates is taken at an arbitrary point inside S. This closed curve S is assumed smooth in the sense of having continuous turning normal vector n. In our case, we use G0 expressed in cylindrical coordinates35

Let C− a circle centered on O that is inscribed to S and suppose that Eq. (2) is evaluated for the points inside C−. Then, substituting Eq. (4) for r < rs in Eq. (2) leads to the expression

The field Pin is assumed to be regular inside C− and admits an expansion in terms of regular Bessel functions as \({P}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)={\sum }_{m = -\infty }^{\infty }{A}_{m}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}{{{{\rm{J}}}}}_{m}\left(kr\right){{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}m\theta }\) with coefficient

since the angular functions eimθ are orthogonal over C−. Eqs. (6) are the null-field equations for a sound-hard rod. A more general formulation of these equations for sound-hard obstacles was first derived by Waterman23. Consider now a circle C+ centred on O that is escribed to S. Since Psc admits the expansion \({P}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)={\sum }_{m = -\infty }^{\infty }{A}_{m}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{m}\left(kr\right){{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}m\theta }\) outside the rod, substituting Eq. (4) for r > rs in Eq. (3) and considering the orthogonality of the angular functions eimθ over C+ we obtain

The approach to derive the T-matrix connecting the coefficients \({A}_{m}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\) and \({A}_{m}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\) is to choose a suitable set of expansion functions \({\phi }_{q}\left({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)\) to express \(P\left({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)\) as

where Pq are unknown coefficients. Substituting representation (8) into Eqs. (6) and (7) we have

with

Using matrix notation we rewrite Eq. (9) as

and the transition matrix connecting these coefficients is

Obviously, the computation of \({\mathsf{T}}\) requires the truncation of the infinite set of equation given in (9) to some maximum value N such that \(\left\vert m\right\vert ,\left\vert q\right\vert \leqslant N\).

In principle, any convenient basis of functions ϕq can be chosen to compute the matrix elements given in Eq. (10). However, in practice, the choice of ϕq may be crucial to yield a well conditioned truncated system of equations and a good approximation to \(P\left({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)\)36. Among the most used expansion functions in two dimensions are the cylindrical wave-functions24,37. In this work, we use \({\phi }_{q}\left({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)={{{{\rm{J}}}}}_{q}\left(k{r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right){{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}q{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) to compute the matrix elements (10) which can be written into a suitable form for numerical calculations, namely

and

where \({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}={r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\left(\theta \right)\) and its derivative drs/dθ are determined from the analytical expressions describing the geometry of the rod’s boundary.

For high aspect ratio obstacles, the cylindrical harmonic series representations of the fields require large numbers of terms. In such cases, the Null-field method is hampered by numerical instabilities due to the rapid growth of the Hankel functions used in the method37,38,39,40. To obtain a numerically convergent scattered field, we considered the three-legged rod with smoother boundary and approximately the same cross section area shown in Fig. 1a. The boundary of this rod is made of circular arcs (six sections) which are suitable for the convergence of the cylindrical harmonic series used to express \(P\left({r}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\right)\) and the computation yielding the scattered field, i.e., Eqs. (12) to (14) with \({P}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)={\sum }_{m = -\infty }^{\infty }{A}_{m}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{m}\left(kr\right){{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}m\theta }\). The radius of curvature of the larger circular arcs of the boundary is determined from simple geometrical considerations as \({{{{\rm{R}}}}}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}=d\sqrt{3}-{{{{\rm{h}}}}}_{0}/2\), and \(d/\cos \left(\alpha \right)\), with \(\alpha =\arctan \left({{{{\rm{h}}}}}_{0}/2d\right)\) is radius of curvature of the smaller circular arcs.

Suppose that \({{\mathsf{T}}}_{0}\) is the \({\mathsf{T}}\)-matrix computed for the TLR with smoother boundary (Fig. 1a) using Eqs. (12) to (14). The rotation of the TLR through an angle β implies a change in the \({\mathsf{T}}\)-matrix given by the expression

where β is taken positive (negative) for counterclockwise (clockwise) rotations. Here, m represents an integer that ranges − N, …, 0, …, N, and \({\mathsf{diag}}\left({{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}mx}\right)\) is the \(\left(2N+1\right)\times \left(2N+1\right)\) diagonal matrix whose entries are the 2N + 1 exponential elements \(\left\{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}Nx},\ldots ,1,\ldots ,{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}Nx}\right\}\). Eq. (15) represents an efficient way to compute the T-matrix for all the TLRs comprising the phononic crystal in Fig. 3a. To derive Eq. (15) assume two polar coordinates systems (r, θ) and \(({r}^{{\prime} },{\theta }^{{\prime} })\) with a common origin inside the scattering object (at its center). Suppose that (r, θ) is fixed in space and the \(({r}^{{\prime} },{\theta }^{{\prime} })\) is fixed in the three-legged rod. The primed system is obtained by rotating the system (r, θ) counterclockwise through an angle β. Consider a point B with coordinates \({r}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}},{\theta }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\,({r}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} },{\theta }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} })\) located outside the rod. Due to the rotation transformation, the coordinates \({r}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }={r}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) and \({\theta }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}={\theta }_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}^{{\prime} }+\beta\). The evaluation of incident and the scattered fields \({P}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)\) and \({P}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\left(r,\theta \right)\) at the point B in both coordinate systems leads to the following relations between coefficients \({A}_{n}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}{\prime} }={A}_{n}^{{{{\rm{in}}}}}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}n\beta }\) and \({A}_{n}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}{\prime} }={A}_{n}^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}n\beta }\). Finally, using the definition of \({\mathsf{T}}\)-matrix (12), a relation of the form Eq. (15) is obtained.

Multiple scattering theory

If an external pressure field P0 (e.g., the field emanating from point sources) impinges the cluster of three-legged rods in Fig. 2a and in Fig. 3a, the total scattered field by all the individual constituent cylinder is given by Eq. (1) where \({\left({A}_{\alpha }\right)}_{q}\) are the coefficients to be determined. To this end, we focus on the total field incident on the α-rod which can be expanded in terms of Bessel functions Jq (of order q) as follows

whose coefficients are related with \({\left({A}_{\alpha }\right)}_{q}\) by means of the \({\mathsf{T}}\)-matrix of the α-rod; \({({A}_{\alpha })}_{q}={\sum }_{s}{({{{{\rm{T}}}}}_{\alpha })}_{qs}{({B}_{\alpha })}_{s}\). The matrix Tα is obtained from Eq. (15) taking β as the angle of rotation of the α-rod respect to the upright TLR (Fig. 1a). The total field (16) is the sum of the external field P0 and the field scattered by all the rods except α, \({P}_{\beta \ne \alpha }^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\). These two fields can be expressed in the reference frame of the α-rod by means of the Graft’s addition theorem37

and from Eq. (1)

where (rαβ, θαβ) are the polar coordinates of the β-rod in the reference frame of the α-rod. The amplitudes \({\left({A}_{\alpha }^{0}\right)}_{q}\) of the incident field are assumed to be known. Thus, by truncating the indexes in Eqs. (16), (17), and (18) to some maximum value m and reformulating the equation \({P}_{\alpha }^{0}\left({r}_{\alpha },{\theta }_{\alpha }\right)={P}^{0}+{P}_{\beta \ne \alpha }^{{{{\rm{sc}}}}}\) into matrix form, we obtain a systems of \({{{{\rm{N}}}}}_{{{{\rm{0}}}}}\left(2m+1\right)\) linear equations for the unknown scattered amplitudes \({\left({A}_{\alpha }\right)}_{q}\).

An acoustic point source of order s located at Rs is defined by a Hankel function of the same order by means of the pressure field \({P}_{s}\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)={C}_{s}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{s}\left(k{r}_{s}\right){e}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}s{\theta }_{s}}\), where \(\left({r}_{s},{\theta }_{s}\right)\) are the polar coordinates that represent the position vector rs in the reference frame of the source \(\left({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{s}={{{\bf{r}}}}-{{{{\bf{R}}}}}_{s}\right)\) and Cs is a complex constant. Therefore, in the reference frame of the α-rod, the external field of Ns point sources of order s located at Rj (with j = 1, 2, …, Ns) can be expressed as (17) with

being \({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{\alpha j}=({r}_{\alpha j},{\theta }_{\alpha j})\) the position vector of the j-th point source in the reference frame of the α-rod located at Rα, i.e., rαj = Rj − Rα. In our computations we consider monopole point sources (s = 0).

Plane wave expansion method

The phononic crystal containing a topological defect (TD) shown in Fig. 3a presents a distorted triangular lattice given by shifts in the lattice constant and the different rotation angles of the three-legged rods. This lattice is being treated as a fluid-acoustic modeling based on the linear inhomogeneous acoustic wave equation

where P is the pressure, while ρ and B represent the mass density and the bulk modulus respectively. To compute the spatial distribution of the band gap (separating the first two bands) induced by the TD, we analyzed the different oblique Bravais lattices that can be defined along the structure. Starting from a central TLR and its six nearest rods, each oblique lattice is defined through the set of primitive lattice vectors

where x, y are the standard unit vectors of the Cartesian coordinate system. The angles ψd, θd and the distance r0i between the central rod and the i-th nearest neighbor (i = 1, …, 6) are calculated using the Cartesian coordinates (xi, yi) of the rods

and the amplitudes a1 and a2 are computed as

assuming the six nearest rods are numbered consecutively. For an undistorted triangular lattice (e.g., Fig. 2a) where the central rod and its six nearest are equidistant a1 = a2 = a, θd = π/3, and the primitive lattice vectors are usually chosen in such a way that ψd = 0.

In the analyzed oblique lattices, all the three-legged rods are assumed having the same rotation angle given by the average rotation angle of the central rod and its six nearest rods (denoted by φd); the standard deviation in relation to the average rotation angle is less than 3% for the analyzed lattices.

According to Eq. (21), the reciprocal lattice is generated by the set of vectors G = n1g1 + n2g2 where n1, n2 are integers, whereas the primitive reciprocal lattice vectors g1 and g2 are given by

Since the Bulk modulus \(B\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\) and the mass density \(\rho \left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\) are periodic in the defined oblique lattice, we express their reciprocal functions as Fourier series with Fourier coefficients \(\epsilon \left({{{\bf{G}}}}\right)\) and \(\nu \left({{{\bf{G}}}}\right)\), respectively. Substituting these expansions, as well as the Bloch pressure \(P\left({{{\bf{r}}}},t\right)={e}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}\left({{{\bf{k}}}}\cdot {{{\bf{r}}}}-\omega t\right)}{\sum }_{{{{\bf{G}}}}}{P}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\left({{{\bf{G}}}}\right){e}^{{{{\rm{i}}}}{{{\bf{G}}}}\cdot {{{\bf{r}}}}}\) into Eq. (20) leads to the generalized eigenvalue problem

With only one three-legged rod per unit cell, we compute the Fourier coefficients by integrating over the area of the unit cell, \({A}_{{{{\rm{uc}}}}}={a}_{1}{a}_{2}\sin {\theta }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\). The result can be written in the form

while the expression for \(\epsilon \left({{{\bf{G}}}}\right)\) is obtained by replacing ρ with B in (26). The integration \({\int}_{{S}_{{{{\rm{TLR}}}}}}\) is over the cross section area of the TLR rotated an angle β as in Eq. (15). The filling fraction of the TLR is f = ATLR/Auc, where \({A}_{{{{\rm{TLR}}}}}=3\left(d-h\sqrt{3}/6\right)h+{h}^{2}\sqrt{3}/4\). Thus, Eq. (26) leads to

Equivalently, the expression for \(\epsilon \left({{{\bf{G}}}}\right)\) can be derived. The structure factor \({{{\rm{F}}}}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta \right)\) is the analytic solution to the integral \({\int}_{{S}_{{{{\rm{TLR}}}}}}{e}^{-{{{\rm{i}}}}{{{\bf{G}}}}\cdot {{{\bf{r}}}}}{{{\rm{ds}}}}\) which may be expressed as the sum of the integrals over the area of three rectangular legs and over the remaining triangular region connecting them. Considering the C3 symmetry of the TLR we can write \({{{\rm{F}}}}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta \right)={{{\rm{I}}}}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta \right)+{{{\rm{I}}}}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta +2\pi /3\right)+{{{\rm{I}}}}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta -2\pi /3\right)+{{{{\rm{I}}}}}_{\Delta }\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta \right)\) with

where \({\kappa }_{1}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta \right) \! = \! {G}_{y}\cos \beta -{G}_{x}\sin \beta\) and \({\kappa }_{2}\left({{{\bf{G}}}},\beta \right)={G}_{x}\cos \beta + {G}_{y}\sin \beta\). On the other hand

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Code availability

All related codes can be built with the instructions in the ”Methods” section.

References

Mermin, N. D. The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 591–648 (1979).

Chaikin, P. M. & Lubensky, T. C. Principles of condensed matter physics (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Yazyev, O. V. & Louie, S. G. Electronic transport in polycrystalline graphene. Nat. Mater. 9, 806–809 (2010).

Machida, T. et al. Zero-energy vortex bound state in the superconducting topological surface state of fe(se,te). Nat. Mater. 18, 811–815 (2019).

Read, N. & Green, D. Paired states of fermions in two dimensions with breaking of parity and time-reversal symmetries and the fractional quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 61, 10267 (2000).

Gao, P. et al. Majorana-like zero modes in kekulé distorted sonic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 196601 (2019).

Gao, P. & Christensen, J. Topological sound pumping of zero-dimensional bound states. Adv. Quantum Technol. 3, 2000065 (2020).

Chen, C.-W. et al. Mechanical analogue of a majorana bound state. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904386 (2019).

Ma, J., Xi, X., Li, Y. & Sun, X. Nanomechanical topological insulators with an auxiliary orbital degree of freedom. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 576–583 (2021).

Menssen, A. J., Guan, J., Felce, D., Booth, M. J. & Walmsley, I. A. Photonic topological mode bound to a vortex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 117401 (2020).

Gao, X. et al. Dirac-vortex topological cavities. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 1012–1018 (2020).

Yang, L., Li, G., Gao, X. & Lu, L. Topological-cavity surface-emitting laser. Nat. Photon. 16, 279–283 (2022).

Peterson, C. W., Li, T., Jiang, W., Hughes, T. L. & Bahl, G. Trapped fractional charges at bulk defects in topological insulators. Nature 589, 376–380 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Bulk-disclination correspondence in topological crystalline insulators. Nature 589, 381–385 (2021).

Deng, Y. et al. Observation of degenerate zero-energy topological states at disclinations in an acoustic lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 174301 (2022).

Wang, Q., Xue, H., Zhang, B. & Chong, Y. D. Observation of protected photonic edge states induced by real-space topological lattice defects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 243602 (2020).

Xia, B., Zhang, J., Tong, L., Zheng, S. & Man, X. Topologically valley-polarized edge states in elastic phononic plates yielded by lattice defects. Int. J. Solids Struct. 239, 111413 (2022).

Ran, Y., Zhang, Y. & Vishwanath, A. One-dimensional topologically protected modes in topological insulators with lattice dislocations. Nat. Phys. 5, 298–303 (2009).

Xue, H. et al. Observation of dislocation-induced topological modes in a three-dimensional acoustic topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 214301 (2021).

Ye, L. et al. Topological dislocation modes in three-dimensional acoustic topological insulators. Nat. Commun. 13, 508 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Pseudospin induced topological corner state at intersecting sonic lattices. Phys. Rev. B 101, 220102 (2020).

Waterman, P. Matrix formulation of electromagnetic scattering. Proc. IEEE 53, 805–812 (1965).

Waterman, P. New Formulation of Acoustic Scattering. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 45, 1417–1429 (1969).

Martin, P. Acoustic scattering and radiation problems, and the null-field method. Wave Motion 4, 391–408 (1982).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: Magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 236809 (2007).

Lu, J. et al. Observation of topological valley transport of sound in sonic crystals. Nat. Phys. 13, 369–374 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Topological acoustic delay line. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 034032 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Tian, Y., Cheng, Y., Liu, X. & Christensen, J. Experimental verification of acoustic pseudospin multipoles in a symmetry-broken snowflakelike topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 96, 241306 (2017).

Wen, X. et al. Acoustic Dirac degeneracy and topological phase transitions realized by rotating scatterers. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 091703 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Directional acoustic antennas based on valley-Hall topological insulators. Adv. Mater. 30, 1803229 (2018).

Waterman, P. Symmetry, unitarity, and geometry in electromagnetic scattering. Phys. Rev., D 3, 825–839 (1971).

Waterman, P. Matrix theory of elastic wave scattering. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 60, 567–580 (1976).

Varatharajulu, V. & Pao, Y. Scattering matrix for elastic waves. I. Theory. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 60, 556–566 (1976).

Lin, Zhi-Kang & Jiang, Jian-Hua Dirac cones and higher-order topology in quasi-continuous media. EPL 137, 15001 (2022).

Morse, P. & Ingard, K. Theoretical Acoustics. International series in pure and applied physics (Princeton University Press, 1986).

K. Varadan, V. & V. Varadan (Eds.), V.Acoustic, Electromagnetic, and Elastic Wave Scattering–focus on the T-matrix Approach (New York: Pergamon Press, 1980).

Martin, P. Multiple Scattering: Interaction of Time-Harmonic Waves with N Obstacles. No. v. 10 in Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Martin, P. On connections between boundary integral equations and T-matrix methods. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 27, 771–777 (2003).

Werby, M. F. & Chin-Bing, S. A. Some numerical techniques and their use in the extension of T-matrix and null-field approaches to scattering. Comput. Math. Appl 11, 717–731 (1985).

Lakhtakia, A., Varadan, V. V. & Varadan, V. K. Scattering of ultrasonic waves by oblate spheroidal voids of high aspect ratios. J. Appl. Phys. 58, 4525–4530 (1985).

Acknowledgements

R.P.S. acknowledges support from the CONEX-Plus programme funded by Universidad Carlos III de Madrid and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 801538. Z.Z. acknowledges support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1404501) and NSFC (12104226). J.C. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through a Consolidación Investigadora grant (CNS2022-135706).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P.S. conducted the PWE and MST and Null-field simulations. P.G., Z.Z, M. Kadic and J. Iglesias assisted in the numerical developments. J.C. conceived the project. R.P.S. and J.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Johan Christensen is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Materials and was not involved in the editorial review of, or the decision to publish, this article.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Aldo Isidori.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pernas-Salomón, R., Gao, P., Zhang, Z. et al. Investigating topological valley disclinations using multiple scattering and null-field theories. Commun Mater 5, 169 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00618-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00618-w

This article is cited by

-

Directional sound propagation in acoustic artificial structures

npj Acoustics (2025)