Abstract

The passivation layer that naturally forms on the lithium metal surface contributes to dendrite formation in lithium metal batteries by affecting lithium nucleation uniformity during charging. Herein, we propose using vacuum thermal evaporation to produce a high-performance ultra-thin lithium metal anode (≤25 µm) with a native layer much thinner than that of extruded lithium. The evaporated lithium metal shows significantly reduced charge-transfer resistance, resulting in uniform and dense lithium plating in both carbonate and ether electrolytes. This study reveals that the evaporated lithium metal outperforms the extruded version in ether electrolyte and with LiFePO4 cathodes, showing a 30% increase in cycle life. Additionally, when paired with LiNi0.6Mn0.2Co0.2O2 cathodes in carbonate electrolyte, the evaporated anode’s cycle life is tripled compared to the extruded lithium metal. This demonstrates that vacuum thermal evaporation is a viable method for producing ultra-thin lithium metal anodes that prevent dendrite growth due to their excellent surface condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The demand for rechargeable batteries with high energy density has significantly increased due to the electrification of transport and the need to store energy from renewable sources1,2. It is expected that the lithium-ion battery market will reach 187.1 billion USD by 2032, representing a compound annual growth rate of 14.2% from 20233. Currently, the vast majority of the lithium-ion batteries have a graphite anode and are approaching their theoretical energy density4. To meet the demand for smaller, lighter, and cleaner batteries, new high-capacity anode materials are required5,6. Among all the candidates, lithium (Li) metal is considered the holy grail of anodes as it has the lowest reduction potential (−3.04 V vs std H) and one of the highest specific capacity (3860 mAh.g−1)7,8,9. However, for a battery, high specific and volumetric energy densities can only be achieved using ultra-thin Li metal (i.e. ≤25 µm)10. Apart from the technical challenge of producing an ultra-thin Li metal anode by conventional extrusion and lamination, another main obstacle to commercialization is its poor chemical and electrochemical stability in batteries11,12. The solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formed on the Li metal surface from its reaction with the electrolyte is typically heterogeneous and mechanically unstable13,14. This results in inhomogeneous Li-ion flux, which can cause dendritic Li deposition during charging of Li metal batteries15,16. During further stripping, the freshly deposited needle-like Li can detach from the anode and become passivated by the electrolyte, resulting in electrically insulated Li metal known as dead Li16,17,18. To prevent the formation of dead Li, reduce electrolyte consumption, and mitigate the large volume change caused by dendritic growth19,20,21, various strategies have been explored to enhance the SEI properties such as electrolyte additives, Li metal coatings, or solid-state electrolytes22,23,24.

Although there has been significant effort to improve the interphase, most research on Li metal omits the role of the native passivation layer on its surface, despite its proven impact on the electrodeposition of Li and the cycling stability of the batteries25. This layer is formed on top of Li metal during processing, handling, and storage, and it typically composed of lithium carbonate (Li2CO3), lithium oxide (Li2O), and lithium hydroxide (LiOH)26. Additionally, this layer typically contains impurities from the extrusion and lamination process, such as silicon (from the oil used during processing) or copper particles. Its thickness varies depending on the storage time and conditions, but it generally ranges from a few nanometers to several hundred nanometers27. It has been shown that the Li nucleation through the passivation layer during early cycles is inhomogeneous, resulting in a heterogenous distribution of spherical nuclei that leads to dendritic growth during further plating28. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the role of the passivation layer and develop methods to produce high-quality Li metal anodes to optimize the interface and reduce its impact on cycling stability.

Several methods are used in battery research to limit the impact of the passivation layer, but they are generally not well controlled. These methods include roll-pressing or brushing the Li metal anode and shortening the storage time29,30,31,32. Additionally, Baek et al. used chemical method to remove the passivation layer using an acid-base reaction with bromine33. The resulting ‘naked’ Li metal exhibits outstanding cyclability in commonly used electrolytes. However, implementing such a preconditioning process in an industrial setting can be challenging as it involves multiple washing and drying steps. Currently, there is a lack of alternative methods to produce high-quality ultra-thin Li metal anodes with good surface conditions.

This work proposes the use of vacuum thermal evaporation of Li metal to produce ultra-thin, dense, homogeneous, smooth, and high-performance Li metal anodes. It is demonstrated that the thermally evaporated ultra-thin Li metal anode has a passivation layer which is one order of magnitude thinner compared to that of commercial extruded Li metal. Consequently, the evaporated Li metal has remarkably low charge-transfer resistance, which results in a dense and homogeneous plating in both carbonate and ether electrolytes. Consequently, evaporated Li metal displays an extremely low overpotential and tripled cycle life in symmetric cells. When combined with NMC622 or LFP cathodes, the evaporated Li metal anode far outperforms extruded Li metal in full cells. This is especially pronounced when using a carbonate electrolyte and NMC622 cathode with an areal capacity of 2 mAh.cm−2 and a current density of 1 mA.cm−2, as the evaporated Li can withstand approximately three times longer cycle life without significant capacity loss compared to extruded Li.

Results

Surface morphology and composition

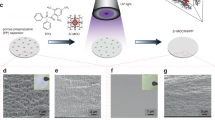

Vacuum thermal evaporation is a widely used technique for large scale production of parts which require a thin coating for mechanical, optical, electrical, or chemical properties34,35. In this study, the evaporated Li metal anode is produced in a vacuum thermal evaporator by condensing Li from a heated Li source onto a copper current collector. The thickness of the evaporated Li metal anode can be easily tuned and was fixed at 25 µm to match that of the commercially available extruded Li metal anode. Figure 1a, b compares the surface morphology of the extruded and evaporated Li metal anodes. For the extruded Li, the surface is rough with visible striations resulting from the extrusion process and localized impurities. The impurities were found to be rich in silicon and copper using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 1). These impurities likely originate from the lamination step, where silicon oils are used. In contrast, the evaporated Li metal has a smooth surface with large grains and no impurities were found on its surface when properly stored. The cross-sectional images in Fig. 1c, d show that both anodes are 25 µm thick, indicating good thickness control for thermal evaporation. For all subsequent electrochemical performance, the thickness of the Li metal was 25 µm with a copper foil current collector of 9 µm.

Pictures of the punched anodes and top view SEM images of the evaporated (a) and extruded (b) Li metal anodes. Cross sectional SEM images of evaporated (c) and extruded (d) Li metal. EDX depth profiles of the atomic concentration of Li, O and C as a function of the accelerating voltage for samples of extruded and evaporated Li metal foils and calculated (Casino) average generation depth of detected Li Kα emission in Li metal for the applied voltages (e).

EDX can be used at different accelerating voltages to estimate the depth composition of Li metal anodes27. This non-destructive method allows for a quick estimation of the composition of the passivation layer. Low accelerating voltages provide information about the composition near the surface, while high accelerating voltages generate X-rays deeper in the sample, providing information about the bulk composition. Figure 1e shows that the concentrations of carbon and oxygen in both Li metal anodes decrease as the acceleration voltage increases. The carbon and oxygen content of the evaporated Li can be explained by its very high reactivity. After deposition under high vacuum, the evaporated Li metal foil is transferred to a glovebox where trace amount of O2, H2O, and CO2 can immediately react with it to inevitably form a very thin passivation layer. However, increasing the acceleration voltage results in a rapid decrease in the oxygen content in evaporated Li, reaching only 1at% at 5 kV. In contrast, extruded Li maintains an oxygen content of around 2 at% even at 10 kV. These findings confirm that the lithium oxide-rich layer is thicker in extruded Li. However, it is important to note that this method has limitations in terms of spatial resolution due to the average X-ray generation depth being 200 nm at 2 kV (see Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, the detection of Li Kα is also limited.

To further investigate the composition of the passivation layer, the Li metal anodes were characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (see Fig. 2). In the wide-scan XPS spectrum of extruded Li (see Supplementary Fig. 2), the silicon impurities, detected with EDX, were also visible. Otherwise, the chemical species present on the two Li metal anodes were Li2CO3, LiOH, Li2O and Li0 with binding energies of 58.1, 57.3, 56.2 and 55.2 eV in the Li 1s spectrum, respectively. The depth compositions of the passivation layers were analyzed using argon ion sputtering. To estimate the etched thickness per sputtering time, a calibration sample of 255 nm thick evaporated Li metal on copper was completely etched (Supplementary Fig. 3). It has also been reported that Li2CO3 and LiOH can decompose under argon ion sputtering and also that the Li2O layer can reform during the measurements even under high vacuum26,27. However, this will not affect the conclusion of a parallel qualitative comparison between the evaporated and extruded Li metal anode. The XPS spectra with all the sputtering steps are given in supplementary information (see Supplementary Fig. 4). Both samples have a similar structure, with a carbonate-rich and hydroxide-rich region near the surface, followed by an oxide-rich region on top of the Li metal. However, the thicknesses of these layers differ significantly between the evaporated and extruded samples. For evaporated Li, the Li0 peak can be detected after only one minute of sputtering (Fig. 2a). According to the calibration sample, one minute of sputtering should correspond to a depth of 10 nm. In contrast, it takes ten minutes of sputtering to detect the Li0 1 s peak on the surface of the extruded Li, which corresponds to a depth close to 100 nm. The analysis demonstrates that the passivation layer of the evaporated Li metal is significantly thinner than that of the extruded Li metal anode. Even after 20 min of sputtering, which should correspond to 200 nm (Fig. 2b), the estimated composition of the extruded Li metal is primarily composed of oxide (43.2 at%) and hydroxide (34.3 at%), with only a limited amount of Li metal (22.6 at%). Whereas for the evaporated Li metal, at the same sputtering step, the main specie is Li metal (51.0 at%) with limited hydroxide (19.4 at%) and oxide (29.6 at%). It is evident that the Li2O layer is several hundred nanometers thick for the extruded Li. In comparison to commercially available extruded Li, the evaporated Li metal has a passivation layer that is only a few tens of nanometers thick, which is one order of magnitude thinner. The extremely thin passivation layer of the evaporated Li is the reason for the visibility of the Li metal rich region after only a few sputtering steps.

Li 1s XPS spectra of the evaporated and extruded Li metal at different sputtering time (a). The sputtering time of 1, 10, 50 min are corresponding to 10, 100, and 500 nm, respectively. Calculated atomic concentration of the carbonate, hydroxide, oxide, and metal from the Li 1s spectra as a function of the depth for the evaporated and extruded Li metal anodes (b).

Impact of the passivation layer on the interfacial resistance

To understand better of the interphase behavior, EIS was measured on Li|Li symmetric cells after cell assembly, after two hours of rest, and after forming at a current density of 0.1 mA.cm−2 and a capacity of 1 mAh.cm−2 for three cycles (Fig. 3a, d) using the two commonly used electrolytes for Li metal batteries: 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC 1:1 + 10 vol% FEC (referred as “carbonate electrolyte”) and 1 M LiTFSI in DOL/DME 1:1 + 0.5 M LiNO3 (referred as “ether electrolyte”). The EIS data were analyzed using DRT (Fig. 3b, e) to extract the values of the solid electrolyte interphase resistance (Rsei), and the values of the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) (an example with the equivalent circuit is given in Supplementary Fig. 5b). The Rsei and Rct resistances (Fig. 3c, f) were calculated using the electrochemical processes located in the ranges of τ of [10−5 −10−3] s and [0.01–1] s (Fig. 3b, e), corresponding of the relaxation time ranges of Rsei and Rct, respectively. All the values of the resistances are given in the supplementary information (Supplementary Table 2).

Nyquist plots for Li|Li symmetric cells comparing extruded and evaporated Li metal (a), DRT peak identification (b), and impedance fitting results (c), for carbonate electrolyte. Nyquist plots for Li|Li symmetric cells comparing extruded and evaporated Li metal (d), DRT peak identification (e), and impedance fitting results (f), for ether electrolyte.

In carbonate electrolyte, the Rsei for both extruded and evaporated Li metal are following the same trend during the resting and the forming cycles as shown in Fig. 3c. The Rsei values for the two types of anodes are very similar, with a slight increase observed after 2 h of rest before stabilizing at 56.7 and 62.4 Ω.cm2 for the evaporated and extruded Li, respectively. As previously reported, this increase of Rsei during resting is due to the chemical reactivity of Li metal with the carbonate electrolyte36. On the contrary, the charge-transfer resistance Rct differs significantly between evaporated and extruded Li. Initially, the Rct is 419.6 Ω.cm2 for evaporated where Rct is 1259.8 Ω.cm2 for extruded Li. This significant difference is mainly due to the thicker oxygen-rich layer present on the extruded Li, offering a low Li+ mobility and a low electrical conductivity and resulting in a high charge-transfer resistance37. After the first forming cycle, the Rct is decreased to 216.0 Ω.cm2 for evaporated Li and 398.3 Ω.cm2 for extruded Li. This decrease of charge-transfer resistance can be explained by the breakage of the passivation layer during Li deposition. The plated Li is only passivated by the SEI, resulting from the reaction of the freshly deposited Li with the electrolyte, which leads to overall decrease of the Rct. Interestingly, after the three forming cycles, the Rct of evaporated Li (193.7 Ω.cm2) is still much lower than for extruded Li (315.0 Ω.cm2). Even after cycling for 50 cycles at a current density of 1 mA.cm−2 and a capacity of 1 mAh.cm−2 per half cycle, the charge-transfer resistance of the evaporated Li metal anodes (20.8 Ω.cm2) is still significantly lower than the one from extruded Li (29.0 Ω.cm2), which evidences that the initial native passivation layer is playing a role on the long-term stability. The Rsei also decreased a lot for the two Li metal anodes after 50 cycles, which can be explained by the increasing of the specific surface aera because of porous dendritic Li formation. However, after 50 cycles the total resistance is still lower for evaporated Li which confirm faster kinetics using evaporated Li in carbonate electrolyte.

For ether electrolyte, the chemical reactivity with Li metal is lower than the carbonate electrolyte36. Consequently, the initial overall resistance is mainly influenced by the surface composition of the Li metal. As shown in Fig. 3f, the initial total resistance of the evaporated Li (99.9 Ω.cm2) is extremely lower than for extruded Li (1523.1 Ω.cm2). Even after two hours of rest, the total resistance is 127.2 Ω.cm2 for evaporated Li and 1832.5 Ω.cm2 for extruded. The total resistance seems to decrease only by breaking the native layer during the forming cycles. Indeed, after forming, evaporated and extruded Li have similar Rsei (101.6 Ω.cm2 and 91.4 Ω.cm2, respectively) but evaporated Li shows a lower Rct (135.1 Ω.cm2) than extruded Li (165.3 Ω.cm2). Similar to the carbonate electrolyte, the evaporated Li metal exhibits lower charge-transfer resistance in ether electrolyte due to its thinner passivation layer. Therefore, evaporated Li metal is expected to exhibit lower overpotential, facilitating homogeneous plating during deposition-dissolution.

Deposition and dissolution in symmetrical cells

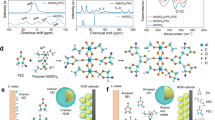

The lower charge-transfer resistance of the evaporated Li is impacting the plating morphology and long-term cyclability in symmetrical cells in both electrolytes. Figure 4a, b shows the top-view SEM images of the deposited Li after plating a capactiy of 1 mAh.cm−2 at a current density of 1 mA.cm−2 in carbonate electrolyte. The plated Li is dense using evaporated Li (Fig. 4a). On the contrary, the plated Li is very porous on extruded Li metal with wisker-like deposits (Fig. 4b). The impedance difference between extruded and evaporated Li metal (as shown in Fig. 3) is evident in the symmetrical cycling, where there is a significant variation in the overpotential. The symmetrical cells with evaporated Li metal exhibit an initial overpotential of approximately 36 mV, while extruded Li metal cells show an overpotential as high as 200 mV (refer to Fig. 4c). In the long-term, the symmetrical cells using extruded Li shows an overpotential increase after 50 h, leading to critical failure at 140 h (Fig. 4c). In comparison, evaporated Li metal anode shows a slower rate of overpotential build-up and stable cycling for more than 300 h (Fig. 4c). Given that both cells have the same configuration and electrolyte, the difference in overpotential at the beginning of the cycle life is due to the intrinsic properties of the Li metal anode. This difference can be explained by the low ionic and electrical conductivity of the oxygen-rich native layer, resulting in a higher total resistance and high overpotential. However, this native layer is also playing a major role for the long-term cycling. At the end of their life, the two types of Li have the same failure mechanism. The symmetrical cells show a rapid increase in overpotential, which can be explained by the accumulation of dead Li. This porous layer increases the tortuosity of the Li+ ions path, which further increases the overpotential. These self-accelerating underisable phenomena lead to rapid cell failure or short circuit in a few cycles. Interestingly, all these parasitic reactions are slowed down using the evaporated Li metal, which can sustain more than twice the number of cycles before critical failure.

SEM images of the plating morphology after one electrodeposition on evaporated (a) and extruded (b), and galvanostatic plating-striping voltage profiles (c), using carbonate electrolyte (1 mAh.cm−2 at 1 mA.cm−2). SEM images of the plating morphology after one electrodeposition on evaporated (d) and extruded (e), and galvanostatic plating-striping voltage profiles (f), using ether electrolyte (1 mAh.cm−2 at 1 mA.cm−2).

Figure 4d, e displays the top-view SEM images of the deposited Li after plating a capactiy of 1 mAh.cm−2 at a current density of 1 mA.cm−2 using ether electrolyte. Impressively, in the ether electrolyte, the plated Li seems to grow epitaxially using evaporated Li and the initial grains structure from the evaporated Li metal is preserved after plating, at least for early cycling (Fig. 4d). In contrast, the plated Li morphology of the extruded Li metal is porous (Fig. 4e). As with the carbonate electrolyte, the higher charge-transfer resistance previously measured is also consistent with the higher overpotential in the symmetrical cells. The cells with evaporated Li have an initial overpotential of approximately 50 mV, whereas for extruded Li, it is approximately 150 mV. For the long-term symmetrical cycling, the failure mechanism in the ether-based electrolyte is a rapid increase in overpotential leading to short circuit. Interestingly, the extruded Li cycles for only 175 h, whereas the evaporated Li is stable for more than 650 h. It is important to note that all cells were cycled in exactly the same conditions and the results were confirmed in multiple cells.

For both electrolytes, the morphology of the counter electrodes during stripping differs significantly between evaporated and extruded Li. When using symmetrical cells with extruded Li metal, the stripping is not homogeneous, resulting in the formation of pits where the copper current collector is visible after only one stripping (see Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast, the counter electrodes with evaporated Li metal are homogeneously stripped with no visible pit formation (see Supplementary Fig. 6). This demonstrates that the low charge-transfer resistance of evaporated Li metal, due to its thinner native passivation layer, also significantly affects the discharge process of stripping Li back from the anodes. Overall, evaporated Li has improved kinetics, resulting in much better plating and stripping morphology, and greatly increased cycle life in symmetrical cells.

Electrochemical performance of full cells

To confirm that evaporated Li outperforms commercially available extruded Li, full cells were cycled using 1.25 mAh.cm−2 LFP cathodes in ether electrolyte and 2.0 mAh.cm−2 NMC622 cathodes in carbonate electrolyte. For both cell configurations, the first coulombic efficiency (Fig. 5a) of evaporated Li is higher than extruded Li. Indeed, in carbonate electrolyte, the average first coulombic efficiency of several cells is increased from 91.5% to 92.0% using evaporated Li. Similarly, in ether-based electrolyte with LFP cathode, it increases from 92.5% (extruded) to 94.3% (evaporated). Higher first coulombic efficiency can be explained by the more homogeneous plating resulting in more stable interphase associated with lower impedance and lower overpotential. The galvanostatic charge/discharge curves (Fig. 5b, c) show that evaporated Li has improved cycling stability and lower polarization in both electrolytes. In contrast, extruded Li exhibits a faster capacity drop. This difference can be attributed to the lower charge-transfer resistance of evaporated Li, resulting in lower overpotential and more uniform plating and striping. These findings confirm that evaporated Li can impede dendrite growth and plate more uniformly than extruded Li, resulting in a slower consumption of active materials. In the long-term cycling (Fig. 5d, e), the cycle life of the evaporated Li metal anode outperforms that of the extruded anode in both cell configurations.

Mean first coulombic efficiency, error bars indicate the standard deviation, over at least three cells (a). Galvanostatic charge/discharge curves for the 1st, 50th, and 100th cycle with NMC622 cathode in carbonates electrolyte (b). Galvanostatic charge/discharge curves for the 1st, 250th, and 500th cycle with LFP cathode in ether electrolyte (c). Discharge capacity and Coulombic efficiency at a current density of 1 mA.cm−2 using 2.0 mAh.cm−2 NMC622 cathode in carbonate electrolyte (d). Discharge capacity and Coulombic efficiency at a current density of 1 mA.cm−2 using 1.25 mAh.cm−2 LFP cathode in ether electrolyte (e).

In the carbonate electrolyte (Fig. 5d), the cycle life is tripled with evaporated Li compared to extruded Li. After 50 cycles, the capacity decreases dramatically for extruded Li, along with a decrease in coulombic efficiency. The rapid decrease in capacity suggests the full consumption of the Li reservoir in the anode10. For evaporated Li, the failure mechanism is very similar but delayed. The capacity only fades after 150 cycles. Again, this can be explained by the thinner passivation layer, lower charge-transfer resistance, and denser Li plating in a carbonate electrolyte using evaporated Li. Additionally, the rate capability measurement (Supplementary Fig. 7a) demonstrates that the evaporated Li also exhibits superior performance compared to extruded Li when subjected to rapid charging. At 5C, the measured specific discharge capacity of evaporated lithium is higher than that of extruded lithium, indicating that the thinner passivation layer, associated with lower charge-transfer resistance, also influences the fast-charging capability.

In the ether electrolyte, it can be observed that evaporated Li is also performing better than extruded Li using LFP cathode (see Fig. 5e). The capacity fading of extruded Li starts after 350 cycles, whereas evaporated Li can handle 450 cycles without significant capacity losses. Moreover, the results of the rate capability measurement (Supplementary Fig. 7b) using ether electrolyte, demonstrate that evaporated lithium exhibits enhanced fast-charging capability, with significantly higher specific charge capacities at 2C, 5C and 10C when compared to extruded Li. This evidence supports the assertion that evaporated Li, similarly than in carbonate electrolytes, exhibits superior fast-charging capability.

To enhance the comprehension of the exceptional electrochemical characteristics of evaporated Li in full cells, postmortem analyses were conducted on the cycled Li metal anodes. In carbonate electrolyte, a relatively dense layer was formed on top evaporated Li even after 50 cycles (see Supplementary Fig. 8a). In contrast, a poorly conductive dead layer, that cracks and delaminates easily, was formed on top of extruded Li metal. Cross-sectional images reveal that extruded Li has a thick and porous dead Li layer, approximately 65 µm thick. In contrast, evaporated Li has only around 15 µm of dead Li on top, which remains electrically conductive and well-attached to the active Li below. Both Li metal anodes exhibit significant volume changes upon cycling in full cells. After 50 cycles, the thickness of the evaporated Li is approximately 95 µm, while extruded Li is around 105 µm. This confirms that even an excellent Li metal anode is subjected to significant volume changes (a 300% increase), which can pose significant challenges for industrialization. The slight difference in overall thickness between the two types of Li metal can be attributed to the thicker and less dense dead Li layer on extruded Li.

In ether electrolyte after 50 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 8c), no dead Li is visible on the surface of both Li metal anodes. For the cross section (Supplementary Fig. 8d), both extruded and evaporated Li are showing similar morphologies, with no visible dead Li formation. This can be explained by the better chemical stability and denser plating achieved when using an ether electrolyte with Li metal36. Additionally, the volume change is lower than with the carbonate electrolyte. The total thickness of the Li after 50 cycles in ether-based electrolyte is 38.1 µm for evaporated and 38.6 µm for extruded. However, the evaporated Li metal is showing denser Li plating and stripping (Supplementary Fig. 8c). After 50 cycles, the surface porosity of the cycled Li anodes has been evaluated to be around 9.8% for extruded Li and only 6.3% for evaporated Li (see Supplementary Fig. 9). This demonstrates that using evaporated Li results in denser and more uniform plating and stripping compared to extruded Li. The improved electrochemical performance in the ether electrolyte (as shown in Fig. 5e) can be attributed to the lower charge-transfer resistance, which leads to denser plating and more homogeneous stripping when using evaporated Li metal. This, in turn, reduces the occurrence of undesirable phenomena that form dead Li and consume the electrolyte.

Figure 6 illustrates the conceptual role of the native layer on the plating and stripping behavior of the Li metal anode. As demonstrated in the XPS data (Fig. 2), commercial extruded Li foil has a passivation layer that is one order of magnitude thicker than evaporated Li metal. Among all the components, including Li2CO3, LiOH, and Li2O, it has been shown that Li2O is the most problematic as it has very poor bulk ionic conductivity at room temperature (10−12 mS.cm−1), resulting in a high charge-transfer resistance25,33,37. This is confirmed as extruded Li metal has huge charge-transfer resistance compared to evaporated Li. Consequently, this thick passivation layer leads to inhomogeneous plating and severe dendrite formation, which was confirmed via symmetrical cell at a current density of 1 mA.cm−2 and an areal capacity of 1 mAh.cm−2 in both electrolytes (see Fig. 4). This directly affects the long-term cyclability of the symmetrical cells as dendrite formation inevitably leads to dead Li formation, electrolyte consumption, and overpotential build up. In contrast, all these parasitic processes are reduced or eliminated using evaporated Li metal due to its inherent ultra-thin passivation layer, very low charge-transfer resistance, ultra-low overpotential. Consequently, the evaporated Li metal can successfully inhibit dendrite formation and allows for high reversibility.

Discussion

Most research on Li metal anode protection or electrolyte design does not consider the impact of the native passivation layer on the lithium surface. However, this passivation layer plays a crucial role in charge-transfer resistance and plating homogeneity. As a result, the long-term cycling performance of a Li metal battery is significantly reduced if the Li metal surface has a thick oxygen-rich passivation layer. Producing an ultra-thin Li metal anode with extrusion and lamination is a technical challenge. Moreover, commonly used extruded Li metal is prone to dendritic growth due to inhomogeneous nucleation through its native passivation layer. This work demonstrates that vacuum thermal evaporation of lithium can be used to produce high-performance ultra-thin Li metal anodes with good thickness control. While extruded lithium exhibits high overpotential during plating and stripping due to its high charge-transfer resistance, the evaporated Li metal anode demonstrates extremely low overpotential and can be uniformly plated due to its thinner passivation layer. It has been demonstrated that the passivation layer of the evaporated Li metal is one order of magnitude thinner than extruded Li. Consequently, evaporated Li metal successfully slows down dendrite formation and outperforms the extruded Li metal anode in both carbonate and ether electrolytes, in both symmetrical and full cells. Vacuum thermal evaporation has been identified as an effective method for producing high-performance ultra-thin Li metal anodes and its scalability is already proven in other industries. To go further, we envision that interphase engineering from a highly pure and controlled surface could open new pathways for optimizing lithium metal anodes. Additionally, subsequent evaporation of lithium and a protective layer could enable a passivation-free Li metal anode which is of considerable interest for developing new Li metal coatings.

Methods

Materials

Li metal rods (Sigma, 99.9%) were used for the vacuum thermal evaporation. Copper current collector (9 µm, MTI) was used as substrate. Extruded Li metal (25 µm) on copper (9 µm) was used as a reference (China Energy). The carbonate electrolyte was 1 M LiPF6 (Sigma, 99,99%, battery grade) in 1:1 EC (Sigma Aldrich, 99%)/DEC (Sigma Aldrich, 99%) with 10 vol% of FEC (TCI Chemicals, 98.0%). The ether electrolyte was composed of 1 M LiTFSI (Sigma Aldrich, 99.99%) in 1:1 DOL (Sigma Aldrich, 99.8%)/DME (Sigma Aldrich, 99.5%) with 0.5 M of LiNO3 (Sigma Aldrich, 99.99%). All the solvents were dried before use using molecular sieves (4 A, Sigma) for at least 24 h and the water contents were measured using Karl Fischer method and were all <15 ppm. To prepare the electrolytes, the solvents were mixed and stirred for 2 h hours before adding the salts and stirred again for 12 h. The polymer separators used for this work were 16 µm thick high porosity polyethylene HPPE (HongTu) and were dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. The CR2032 stainless steel cases, spacers, and springs (Hohsen) were also dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. NMC622 (2.0 mAh.cm−2, NEI) and LFP (1.25 mAh.cm−2, NEI) cathodes were dried under vacuum at 120 °C for 24 h. The electrolytes and all the materials were prepared and stored in a glovebox under argon (O2 < 0.1 ppm, H2O < 0.1 ppm).

Preparation of the evaporated Li metal anode

The copper current collector was cleaned with ethanol and dried under vacuum overnight at 60 °C. Li metal anode was made by using the physical vapor deposition (PVD) method. The PVD system (MBraun), is integrated into an Ar-Glovebox (MBraun). The H2O and O2 levels were kept under <0.1 ppm. The deposition process was controlled using a quartz crystal controller (Inficon GmbH) and a quartz microbalance crystal sensor. The copper current collector was fixed on a rotating glass substrate and the chamber was depressurized to 10e−6 bar. A stainless-steel source crucible was filled with the Li metal rods and heated to deposit 25 µm. The rates and rotation speed were optimized to obtain a dense and smooth Li metal anode. Thereafter, the foil was punched into discs for the electrochemical testing.

Electrochemical characterization

The symmetrical and full cell cycling was performed using a Landt CT3002AU battery test system. The EIS measurements were made using an Octostat Ivium tester. The EIS was measured at the open-circuit potential from 0.1 Hz to 1 M Hz using a voltage amplitude of 10 mV. The EIS data was analyzed using Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) using an internally developed algorithm. The coin cells were assembled in the glovebox and the amount of electrolyte was 60 µL for all the configurations. The Li|Li symmetrical cells were formed at 0.1 mA.cm−2 and 1 mAh.cm−2 for 3 cycles and then cycled at 1 mA.cm−2 and 1 mAh.cm−2. The full cells were formed for 3 cycles at 0.1 mA.cm−2 and cycled at 1 mA.cm−2 with a voltage window for Li|NMC622 between 3 and 4.2 V and for Li|LFP between 3 and 3.9 V. The rate capability measurements were made using the same cells configuration than full cells, with increasing current densities. The current densities, for each step of 5 cycles, were C/20, C/10, C/5, C/2, 1C, 2C, 5C, and followed by 15 cycles at C/2 for carbonate electrolyte and NMC622 cathodes (1C = 2 mA.cm−2). The current densities, for each step of 5 cycles, were C/10, C/5, C/2, 1C, 2C, 5C, 10C, and followed by 15 cycles at 1C for ether electrolyte and LFP cathodes (1C = 1.25 mA.cm−2).

Physicochemical characterization

The evaporated and extruded Li metal anodes were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss Gemini) and were transferred using a vacuum transfer shuttle to avoid any contamination. The Li metal samples were analyzed using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Zeiss, Gemini) and the data was analyzed using the software Aztec (Oxford Instruments). For the postmortem images, the cells were dissembled in the glovebox and the Li metal anodes were washed 3 times using DEC for the Li|NMC622 and DME for the Li|LFP, to remove the salt from the electrolyte, and dried in the glovebox for 24 h. The Li metal anodes were analyzed with XPS using a Kratos Axis Supra with a monochromated Al Kα X-ray source. The energy of the argon ions was set to 4 keV and an area of 2 × 2 mm2 was sputtered by raster scanning. The sputter rate was calibrated as described in the main text using a 255 nm thick calibration sample. The samples were never exposed to air and fully transferred under inert conditions. The XPS data were analyzed using CasaXPS software. While the samples were electrically grounded, minimal binding energy calibration was necessary to reference the spectra acquired during the depth profiling. This was done by setting the C-C/C-H peak of the C 1 s orbital to 284.8 eV.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Maisel, F., Neef, C., Marscheider-Weidemann, F. & Nissen, N. F. A forecast on future raw material demand and recycling potential of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 192, 106920 (2023).

Chu, S. & Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303 (2012).

Markets and Markets. Lithium-ion battery market, global forecast to 2032 (Markets and Markets, 2024).

Zhang, H., Yang, Y., Ren, D., Wang, L. & He, X. Graphite as anode materials: Fundamental mechanism, recent progress and advances. Energy Storage Mater. 36, 147–170 (2021).

Xu, C. et al. Future material demand for automotive lithium-based batteries. Commun. Mater. 1, 99 (2020).

Fichtner, M. et al. Rechargeable Batteries of the Future—The State of the Art from a BATTERY 2030+ Perspective. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2102904 (2022).

Nzereogu, P. U., Omah, A. D., Ezema, F. I., Iwuoha, E. I. & Nwanya, A. C. Anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 9, 100233 (2022).

Azam, M. A., Safie, N. E., Ahmad, A. S., Yuza, N. A. & Zulkifli, N. S. A. Recent advances of silicon, carbon composites and tin oxide as new anode materials for lithium-ion battery: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 33, 102096 (2021).

Wang, R., Cui, W., Chu, F. & Wu, F. Lithium metal anodes: Present and future. J. Energy Chem. 48, 145–159 (2020).

Wu, W., Luo, W. & Huang, Y. Less is more: a perspective on thinning lithium metal towards high-energy-density rechargeable lithium batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 2553–2572 (2023).

Acebedo, B. et al. Current Status and Future Perspective on Lithium Metal Anode Production Methods. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203744 (2023).

Schnell, J., Knörzer, H., Imbsweiler, A. J. & Reinhart, G. Solid versus Liquid—A Bottom-Up Calculation Model to Analyze the Manufacturing Cost of Future High-Energy Batteries. Energy Technol. 8, 1901237 (2020).

Ramasubramanian, A. et al. Stability of Solid-Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) on the Lithium Metal Surface in Lithium Metal Batteries (LMBs). ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 10560–10567 (2020).

Hao, F., Verma, A. & Mukherjee, P. P. Mechanistic insight into dendrite–SEI interactions for lithium metal electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 19664–19671 (2018).

Guo, R., Wang, D., Zuin, L. & Gallant, B. M. Reactivity and Evolution of Ionic Phases in the Lithium Solid–Electrolyte Interphase. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 877–885 (2021).

He, Y. et al. Origin of lithium whisker formation and growth under stress. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 1042–1047 (2019).

Liu, D.-H. et al. Developing high safety Li-metal anodes for future high-energy Li-metal batteries: strategies and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 5407–5445 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Stable Li Metal Anodes via Regulating Lithium Plating/Stripping in Vertically Aligned Microchannels. Adv. Mater. 29, 1703729 (2017).

Didier, C., Gilbert, E. P., Mata, J. & Peterson, V. K. Direct In Situ Determination of the Surface Area and Structure of Deposited Metallic Lithium within Lithium Metal Batteries Using Ultra Small and Small Angle Neutron Scattering. Adv. Energy Mater. 2301266 https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202301266 (2023).

Sheng, S., Sheng, L., Wang, L., Piao, N. & He, X. Thickness variation of lithium metal anode with cycling. J. Power Sources 476, 228749 (2020).

Gu, J., Shi, Y., Du, Z., Li, M. & Yang, S. Stress Relief in Metal Anodes: Mechanisms and Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2302091 https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202302091 (2023).

Lu, G., Nai, J., Luan, D., Tao, X. & Lou, X. W. D. Surface engineering toward stable lithium metal anodes. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf1550 (2023).

Hobold, G. M. et al. Moving beyond 99.9% Coulombic efficiency for lithium anodes in liquid electrolytes. Nat. Energy 6, 951–960 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Strategies to anode protection in lithium metal battery: A review. InfoMat 3, 1333–1363 (2021).

Srout, M., Carboni, M., Gonzalez, J. & Trabesinger, S. Insights into the Importance of Native Passivation Layer and Interface Reactivity of Metallic Lithium by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Small 19, 2206252 (2023).

Otto, S.-K. et al. Storage of Lithium Metal: The Role of the Native Passivation Layer for the Anode Interface Resistance in Solid State Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 12798–12807 (2021).

Otto, S.-K. et al. In-Depth Characterization of Lithium-Metal Surfaces with XPS and ToF-SIMS: Toward Better Understanding of the Passivation Layer. Chem. Mater. 33, 859–867 (2021).

Becking, J. et al. Lithium-Metal Foil Surface Modification: An Effective Method to Improve the Cycling Performance of Lithium-Metal Batteries. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, 1700166 (2017).

Bela, M. M. et al. Tunable LiZn-Intermetallic Coating Thickness on Lithium Metal and Its Effect on Morphology and Performance in Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2300836.

Chen, W. et al. Brushed Metals for Rechargeable Metal Batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202668 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. The effect of removing the native passivation film on the electrochemical performance of lithium metal electrodes. J. Power Sources 520, 230817 (2022).

Ryou, M., Lee, Y. M., Lee, Y., Winter, M. & Bieker, P. Mechanical Surface Modification of Lithium Metal: Towards Improved Li Metal Anode Performance by Directed Li Plating. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 834–841 (2015).

Baek, M. et al. Naked metallic skin for homo-epitaxial deposition in lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 1296 (2023).

Bashir, A., Awan, T. I., Tehseen, A., Tahir, M. B. & Ijaz, M. Interfaces and surfaces. In Chemistry of Nanomaterials 51–87 (Elsevier, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818908-5.00003-2.

Taylor, D. M. Vacuum-thermal-evaporation: the route for roll-to-roll production of large-area organic electronic circuits. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 30, 054002 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. A Comparison of Carbonate-Based and Ether-Based Electrolyte Systems for Lithium Metal Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 170, 010535 (2023).

Lorger, S., Usiskin, R. & Maier, J. Transport and Charge Carrier Chemistry in Lithium Oxide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, A2215–A2220 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jose-Antonio Gonzalez (Belenos Clean Power) for providing some of the extruded Li metal samples.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and C.F. developed the vacuum thermal evaporation of the Li metal anode. N.R. and A.I. designed the research project. N.R. performed all the electrochemical and materials characterizations. N.R. and M.M. performed the XPS measurements and analysis. N.R. and G.M. performed the EIS measurements and DRT analysis. N.R. wrote the whole manuscript. All authors read the manuscript, provided feedback, and contributed to it with useful discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Biao Chen and the other anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Guangmin Zhou and Jet-Sing Lee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rospars, N., Srout, M., Fu, C. et al. High performance ultra-thin lithium metal anode enabled by vacuum thermal evaporation. Commun Mater 5, 179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00619-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00619-9

This article is cited by

-

Research, development, and innovation insights for solid-state lithium battery: laboratory to pilot line production

Discover Electrochemistry (2025)