Abstract

Soft robotic actuation concepts meet and sometimes exceed their natural counterparts. In contrast, artificially recreating natural levels of autonomy is still an unmet challenge. Here, we come to this conclusion after defining a measure of energy- and control-autonomy and classifying a representative selection of soft robots. We argue that, in order to advance the field, we should focus our attention on interactions between soft robots and their environment, because in nature autonomy is also achieved in interdependence. If we better understand how interactions with an environment are leveraged in nature, this will enable us to design bio-inspired soft robots with much greater autonomy in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many soft robotics studies take inspiration from nature, and many natural principles that rely on compliance have been recreated or even surpassed (Fig. 1a–i)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. For example, instability-enabled fast actuation observed in the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula)1 has inspired the design of a soft robotic counterpart7 and adaptive gripping such as by elephants2 has inspired a great variety of soft robotic grippers8,11,12. In contrast to these successes that are mainly focused on actuation, we observe that there is still a striking gap between soft robotic systems and natural organisms regarding their autonomy. Bacteria, plants, and animals demonstrate complex and diverse behavior without external control input, i.e., they operate control-autonomously. Moreover, organisms obtain energy from their environment, and are therefore energy-autonomous. In contrast, existing soft robots are strongly dependent on external control and energy input, severely limiting their autonomy.

a–d Natural and (e–i) soft robotic examples of harnessing compliance. a Adaptive shape change: octopus can squeeze through tiny openings only limited by the size of their rigid beak. b Fast motion: Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) has bistable leaves that close quickly (in ≈ 0.1 s) as a result of a mechanical instability1. c Versatility: elephant trunks are both flexible and very strong, enabling them to lift a wide range of objects using a limited repertoire of movements2. d Power amplification: bullfrogs and grasshoppers slowly load their tendons and other flexible tissue with elastic energy, which they quickly release to jump3. The optimal series tendon stiffness value depends on loading rate, and this may explain why bullfrogs have more compliant series elements than grasshoppers4. The human Achilles tendon stores and releases energy with every step5. e Adaptive shape change: vine robot can pass through openings much smaller than its nominal body width. From ref. 6. Reprinted with permission from AAAS. f Fast motion: artificial Venus flytrap actuator closes in 50 ms. Reprinted from ref. 7 with permission. Copyright 2019 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. g Versatility: soft grippers can grasp a wide variety of objects using a simple pressure input. Reprinted from ref. 8 with permission. Copyright 2011 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. h, i Power amplification: slow storage and quick release of energy in (h) a jumping popper robot (from ref. 9, reprinted with permission from AAAS) and (i) a bistable spine runner (from ref. 10 reprinted with permission under CC BY-NC 4.0). j The human heart as inspiration towards improved autonomy in soft robots. The human heart pumps blood by periodic contractions of its ventricles, paced by action potentials generated in the sinoatrial node (SAN). The ventricles are highly compliant in the relaxed state, such that the filling volume is variable. Moreover, additional filling intrinsically leads to more energetic contraction. This local loop leads to left-right balance. The frequency of action potential generation is the result of physical processes in the cells of the SAN, and these processes are affected by a multitude of attributes of their direct environment, such as neuronal signals and the concentration of specific chemical compounds. These can be interpreted as external control inputs from the environment to the heart. Energy is control-autonomously harvested from the heart’s environment, i.e., from blood passing through it. At the same time, the heart is a crucial element in the blood circulation.

What is currently holding us back from creating autonomous soft robots, and how can inspiration from nature be helpful here, too? To explore this idea, we look at the human heart, one of many possible specific examples from nature, and describe some of the mechanisms behind its functioning in its specific environment (Fig. 1j). We focus our question on control- and energy-autonomy. There are several other aspects that are crucial to autonomy in nature, including self-healing, replication, growth, and evolution. These aspects are partially addressed elsewhere in soft robotics literature13,14, but we limit ourselves to autonomous functioning at a given moment in time.

We also discuss some examples that we believe represent the relevant state-of-the-art of autonomous soft robotics (Fig. 2). Guided by these examples, we give practical definitions of control- and energy, that are applicable to (soft) robots, as well as natural examples.

a Summary of functionality of each system, 1. Octobot. From ref. 20. Reproduced with permission from SNCSC. 2. Robotic fish. From ref. 22. Reprinted with permission from AAAS. 3. Untethered multi-gait robot. From ref. 23. The publisher for this copyrighted material is Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers. 4. Continuously learning modular robot. Reprinted from ref. 25 with permission under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. 5. Ring-oscillator walker26. Credit: David Baillot/University of California San Diego. 6. Relaxation oscillator robot. Reprinted from ref. 29, Copyright (2022), with permission from Elsevier. 7. Twisted LCE strip robot. Reprinted from ref. 30 with permission under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. 8. Human heart. b Control autonomy. Iso-lines (low to high) are determined from the product of task environment complexity (horizontal axis) and independence of external intervention (vertical axis). c Energy autonomy. Iso-lines (low to high) are determined from the product of task duration (horizontal axis) and independence of external intervention (vertical axis).

We compare the state of the art of autonomy in soft robotics with our example from nature to come to our perspective on the future of bio-inspired autonomy in soft robots. Our two main points are: 1. Even robots with very limited autonomy, according to the current state of the art, can be usefully applied, especially when interactions with an environment are leveraged. 2. Compliance seems to play an important role in autonomy, beyond actuation. Soft robotics is a promising platform for studying such effects.

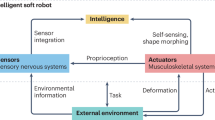

Autonomy in nature as inspiration for soft robotics

To set the scene for our perspective on bio-inspired autonomy of soft robots, we first share our view on control in soft robotics, since this explains our emphasis on interactions with an environment. In soft robotics, we are usually not able to fully observe or control the state of a robot due to its infinite dimensionality and continuous deformations that are strongly influenced by interactions with its (unknown) environment. This complicates the control problem when viewed in the classical context15. We propose a holistic view on soft robot control, inspired by the concept of ‘embodied intelligence’16. Compliance, the defining property of soft robots, implies responsiveness to an environment. Existing successes in soft robotics harness exactly these mechanical interactions (Fig. 1e–i), but such morphological computation alone is insufficient to achieve natural levels of autonomy. Nevertheless, insofar as this responsiveness affects behavior, we consider it as part of a total control system consisting of the robot’s brain, body and environment. Our definition of soft robot control is then the design of a complete system in which desired behavior emerges. The specific challenge as well as the benefit of soft robotics in this context is its innate responsiveness to physical interactions. This may enable the offloading of a larger part of the control problem from the ‘brain’ to the body and environment 17.

Since behavior emerges in interaction with the environment, it follows that it is essential to consider the tasks and possible environments of a robot when discussing autonomy. In fact, thinking about robots as pursuing goals in specific environments, even if they are challenging tasks in dynamic environments, makes the problem of autonomy more tractable, within that delimited scope. This becomes clear when we study a specific example from nature: the human heart (Fig. 1j).

Case study: the human heart

Studying specific examples of compliance in actuation has led to the development of soft robotic actuation principles. Similarly, we believe that looking at specific examples, here the human heart and its task of pumping blood in its environment, may provide direct inspiration for autonomous soft robots. Note that we intentionally single out an organ rather than looking at a full organism. That is because even the highest level of task environment complexity that we are currently able to address by soft robotics is not comparable to the complexity that organisms face in their struggle for survival. As such, focusing on subsystems allows a more relevant comparison for the current state of the art of soft robotics. Organisms have a similar interdependence with their environment, but with an organ, this becomes immediately clear.

Task environment

We focus on the pump function of the heart in a healthy adult. The rest of the body is its environment. The main task of the heart in that scope is to circulate blood through the body. The cardiac output (flow rate) is required to be variable, depending for example on activity level. Note that the cardiovascular system consists of two separate parts that are connected in series. The left, ‘systemic’, circulation provides oxygen-rich blood to the body, the right, ‘pulmonary’, circulation passes carbon dioxide-rich blood to the lungs. An important requirement is that these circulations remain balanced, despite disturbances such as temporal variations in shunt flow and in the vascular system’s resistance to flow18.

Control

The heart leverages mechanical compliance and local control loops, and receives neuronal and hormonal inputs that encode information about the heart’s goal (a specific cardiac output). Isolated heart muscle tissue intrinsically contracts periodically, at a low base frequency. In the heart, contractions are modulated by the sinoatrial node (SAN), a group of cells internal to the heart that generates periodic action potentials. These electrical signals cause the heart muscles to contract at the SAN’s frequency. By these mechanisms, the heart beats fully independently of external control input. Moreover, flow imbalance between left and right circulations is constantly corrected for by the so-called Frank-Starling mechanism. This embodied control loop is also local to the heart and strongly relies on mechanics. When there is imbalance, which in fact continually happens as a result of widening and narrowing of blood vessels during exercise, stress, change of posture, and even breathing, more blood returns to one side of the heart. As a result, the (mechanically compliant) ventricle on that side fills to a larger volume before contraction begins. The resulting increased preload (stretch of the muscle cells) causes the ventricle to contract more efficiently, such that the volume at the end of the contraction is not strongly affected by the increased preload. Therefore, the displaced volume of blood in one heartbeat (stroke volume) increases if the filling is higher, and this causes a negative feedback that restores balance between the left and right circulations. As such, the Frank-Starling effect emerges from the mechanical interaction between the heart and the blood circulation. For all of this, the heart is completely independent of external control input18.

Beyond that, the dynamics of the SAN’s oscillations is affected at molecular level by dozens of external hormonal and neuronal signals, some accelerating and some depressing the generation of action potentials19. As a result, heart rate emerges from a complex analog process in dedicated, highly specialized hardware, completely unlike an explicitly defined control law in a digital computer.

Energy

The required operating time of the heart is the life span of a human, so on the order of 80 years, or 2.5 × 109. During this incredible period of time and number of actuation cycles, the heart harvests energy from its surroundings, specifically from blood. Chemical energy, extracted from food, is transported to the heart by the blood stream. Interestingly, the heart plays a crucial role in the circulation of the blood through the entire body, including itself.

The state-of-the-art of soft robot autonomy

Having examined a natural example in depth, we now introduce seven existing soft robots to initiate a discussion on the topic of artificial autonomy (Fig. 2a). This discussion will encompass the achievements that have been made thus far and the remaining challenges that must be overcome. Nowadays, although clear definitions are lacking, the strive is mostly towards as much autonomy as possible, but is this necessary?

As a first example, ‘Octobot’ is a centimeter scale soft robotic demonstrator shaped after an octopus, whose arms are actuated in two sets of four by a (separately produced) microfluidic oscillator. Microfluidic valves in the oscillator autonomously convert pressurized fuel input into alternating fuel outflow20. The alternating outflow of the oscillator is amplified by a liquid-to-gas conversion (2H2O2(l) → 2H2O(l, g) + O2(g)) over a Pt catalyst, and the resulting alternating gas flow is fed to the soft bending actuators to move the arms. All of the body, including actuators and catalyst is 3D-printed. After being loaded with 1 mL pressurized H2O2 reactant, this robot functions without further user intervention for 4–8 min, where the displayed behavior consists of alternating bending of its two sets of arms, while the robot itself remains stationary.

The second example is the most recent generation of a soft robotic fish. Like previous versions, it has an antagonistic actuator pair on its soft tail. In the more recent versions, the actuators are powered using water, driven by a gear pump21,22. Like Octobot, this aquatic robot is explicitly called autonomous by their creators, and the second and third generations are able to operate without physical tethers. The latest robotic fish is equipped with a camera, and inertial and pressure sensors. Horizontal steering is achieved by differential actuation of the tail actuators. Depth control within a limited range is achieved by a combination of closed-loop buoyancy control and dynamic adjustments to the pitch angle of two dive planes. Operation outside this range requires a diver to attach or remove magnetic weights. User commands are conveyed to the robot via a custom acoustic modem. The robot can swim several hundred meters during its 40 min battery life.

As a third example, we refer to the untethered variant23 of the quintessential multi-gait robot24. Its entire body essentially consists of soft bending actuators: one for each of its four legs, and another for its back. By executing various preprogrammed actuation patterns, the robot can locomote using an undulating or ambulating gait. In order to demonstrate tetherless operation for up to 2 h, the design of the untethered multi-gait robot is scaled up to more than half a meter in length, allowing it to carry a (rigid) control system including a battery, pump and valves on its back.

A fourth example, developed by us, is a modular, continuously learning robot that is made of units that each consist of a soft extension actuator, a pump, a microcontroller, and a position sensor. Individual units are unable to locomote, but the combined robot is able to move forward on smooth terrain when each unit extends and contracts its soft actuator at the right moment with respect to its neighboring units25. Each unit continuously adapts its behavior in order to optimize a measured reward (in this case velocity), without any direct communication with other units. The units employ a stochastic scheme that results in remarkably adaptive behavior and damage tolerance of the collective system. The reward (the goal) is preprogrammed, but the robot learns and adapts its behavior without any control input. The robotic units are connected to an external power supply for most experiments, but they also carry a battery, such that they can operate for about 30 min before being recharged by an operator.

As the fifth example, we look at an electronics-free four-legged robot that uses a fluidic ring oscillator to cyclically activate three (or two rings to activate six) groups of actuators26. The individual switching elements in the ring oscillator are soft bistable valves27. An odd number of these valves connected in a ring will spontaneously oscillate when driven with constant input28. This robot can walk forward when carrying a compressed CO2 canister for its energy supply, running for up to 4 min depending on the canister size. It can change its course in response to user-inputs from a fluidic, tethered remote control. Without user input, it can reverse direction when it bumps into a wall. However, it can do so only once, as the fluidic sensor that detects contact with the wall needs to be pre-pressurized by an operator.

The sixth example, also developed by us, is another electronics-free four-legged robot. It uses a fluidic circuit that consists of three parallel fluidic relaxation oscillators to activate the legs in a cyclic pattern. The individual oscillators are based on compact, soft hysteretic valves that transform a continuous inflow into a pulsatile outflow29. Crucially, this fluidic circuit concept is fundamentally more flexible, because the same circuit supports multiple different activation patterns. The system changes from one pattern to the other in response to mechanical interactions. The specific circuit used in this robot alternatingly activates the two front legs of the four-legged robot. The back legs also step alternatingly, even though the control input to the left and right back legs is identical. Their stepping motion results purely from the interaction between body rotations, leg elasticity, and ground reaction forces. The robot was permanently tethered to a membrane pump.

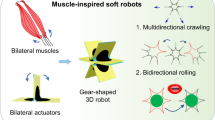

So far, all examples use fluid-driven actuators. To represent how other materials and actuation mechanisms can be used to improve autonomy we include a final example. This soft robot consists of a single twisted strip of liquid crystal elastomer (LCE)30. LCE is a soft material that reversibly deforms when exposed to elevated temperatures. When the twisted strip is placed on a hot surface, the material is locally heated at the contact points and deforms. As a result of these local deformations, the strip globally bends and rolls forwards, causing a new set of contact points to touch the hotplate. This sets up a cycle of heating and deformation that causes the strip to continually bend and roll forward, as long as it remains on a hot surface. The surface can either be smooth, such as a flat hotplate or a curved car roof, or granular, such as dry, hot loose sand and rock terrains. While rolling, the strip can transport cargo or collect debris. Moreover, when the strip rolls into an object, the contact force may cause the strip to snap to a new configuration. As a result, the strip turns or reverses its direction of motion.

Note that this overview is not intended as a complete review. Instead, we provide a selection that we believe spans the range of autonomy that is currently achieved in soft robots. Overall, we see that attention for soft robots with increased autonomy is rising, see for example31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. As a result, many equally interesting works exist within the same range of autonomy that are not included in our comparison. Also, note that only Octobot and the twisted LCE strip robot are completely soft. The other examples are hybrid rigid/soft structures, but soft robotic components are central to their operation. In this perspective, we also include such hybrid robots, since the requirement to be completely soft is application dependent.

Definitions of autonomy in the context of a task environment

We have already mentioned control- and energy-autonomy, but what specifically do we mean by this? In existing soft robotics literature there is no consensus on how to measure autonomy. So to aid our discussion, we introduce definitions that help us compare existing soft robots with natural counterparts.

We define control-autonomy as the ability of a soft robot to show behavior relevant to a higher-level goal in a specific task environment, without external commands.

The first element in our classification of control-autonomy is the abstraction level at which user input is required. Specifically, the desired actions of a lower-level sub-system, such as an actuator, may be dictated by a higher-level controller, such as an online trajectory planning algorithm. In a highly control-autonomous robot this chain of control continues to ever higher levels of abstraction embedded into the robot, until the only required inputs are high-level goals or until no inputs are needed at all. Note that the control system can but does not need to be implemented as an electronic system. It can also be the result of a smartly designed multi-physical response to external cues.

The second element is task environment complexity. If the task environment is more challenging, a robot must display more diverse behavior to operate autonomously. This typically requires more advanced adaptability to the environment, and some level of (implicit or explicit) decision making or planning. It follows that for robots that operate in more challenging task environments, it is more challenging to succeed without external control input.

Taken together, we propose to multiply independence of external control by the complexity of the task environment, to arrive at a control-autonomy index that enables a comparison between different robots (Fig. 2b).

Next, we define energy-autonomy as the ability of a soft robot to fulfill a task without relying on a tether or operator for its energy supply.

The first element in energy-autonomy is the dependence on a tether or active external intervention for its energy supply. If a robot can control-autonomously find and connect to energy sources available in the environment, or continuously collect energy from the environment such as from sunlight, it is completely independent of external intervention for its energy supply. On the other hand, if a robot is powered from a mobile power source such as an electrochemical battery or compressed gas container, but it cannot recharge or replace it without active intervention by an operator, then this robot would be rated lower on independence.

The second element is task duration, more specifically the time a robot needs to be able to operate without intervention in order not to be hindered in its performance. For example, if the task of a soft robot is to deliver a payload, and it takes 1 h to reach the destination, then it is clearly required to be able to operate for 1 h without external intervention (such as a battery swap) to be independent.

The product of independence and task duration results in an energy-autonomy index (Fig. 2c).

Classifying existing soft robots by autonomy

We categorize the seven previously treated robotic examples on their control- and energy-autonomy in Fig. 2b, c, and compare to the human heart.

Control-autonomy

For control-autonomy (Fig. 1b), we score task environment complexity on the horizontal axis. We define four levels:

-

1.

Robot operates without interaction with its environment. This means that the robot cannot impact the world or its position in it.

-

2.

Task and environment are both ‘simple’, i.e., the robot performs a single task and the environment is both known in advance and not diverse. An example is walking on a flat surface, using a single gait.

-

3.

Task, environment, or both are ‘complex’. As a result, the robot needs to show more than a single behavior in order to complete a task, either because that is the nature of the task itself, or in order to perform a single task in a diverse or dynamic environment. An example is locomotion on diverse terrain that requires different gaits.

-

4.

Robot pursues higher-level goals, such as finding a way out of a cluttered environment, or picking only ripe fruits.

Octobot20 does not interact with the environment and is rated level 1 for task environment complexity. The tasks of the untethered multi-gait robot23 (moving forward using one gait or the other), the continuously learning modular robot25 (moving forward while continuously optimizing its gait), the ring-oscillator walker26 (walking in multiple directions), the relaxation oscillator robot29 (responding to mechanical cues), and the twisted LCE strip robot30 (changing direction when touching an obstacle) require multiple behaviors, such that we rate them level 3. We place the robotic fish22 in level 4, assuming that the task is to survey a reef, finding interesting objects to capture on camera, and returning to a home position in time to report and recharge. We define additional use cases for the electronics free walker, robotic fish and multi-gait robot, where they simply move in a predetermined direction, rated level 2.

On the vertical axis, we indicate four levels of independence, i.e., four abstraction levels at which control is taken over by an outside operator or external control system.

-

1.

Timed, actuator-level inputs.

-

2.

Behavior level input, for example commanding a robot to go straight ahead or turn, where the robot autonomously controls the required actuator pressurization.

-

3.

Only higher-level goals are commanded, such as ‘follow blue lights’, or ‘go home’, where the robot still needs to decompose these into the required behaviors.

-

4.

No inputs are required for the robot to fulfill its set purpose.

The ring-oscillator walker and multi-gait robot are both able to show multiple different gaits, when directly instructed to do so, corresponding to independence level 2, at task-complexity level 3. Moreover, they can walk using a single gait without any user-input during operation, corresponding to independence level 4, at task-complexity level 2. (Note that the ring-oscillator walker also changes gait upon hitting a wall without any external commands, but it can do so only once). The continuously learning modular robot, relaxation oscillator robot, and twisted LCE strip robot do not receive any external control input during operation, corresponding to independence level 4. The robotic fish receives behavior-level input (independence level 2) when navigating a complex environment (complexity level 4), but can fully autonomously (independence level 4) move in a certain direction (complexity level 2). As such, we observe that robots can perform simpler tasks more independently and vice versa, resulting in similar levels of autonomy, i.e., for different use cases, they move along iso-autonomy lines in Fig. 2b.

Of the compared soft robots, the continuously learning modular robot, relaxation oscillator robot and twisted LCE strip robot achieve the highest control-autonomy index. Interestingly, these are also the robots whose behavior is influenced by physical interactions. This coupling intrinsically enables them to respond to changes in their environment, essentially recruiting the environment as a resource.

The heart needs to adjust its behavior (heart rate, contractile strength) in order to provide the required cardiac output in its variable environment, while maintaining left-right balance. We therefore rate the task environment complexity as level 3. When viewed as a separate entity, the heart is not fully independent of external control input such that we rate it level 3 for control-independence. The heart’s control-autonomy index is therefore on par with, but does not exceed, the reviewed soft robotic examples.

Energy-autonomy

Regarding energy-autonomy (Fig. 2c), on the horizontal axis, we indicate the order of magnitude of the task duration. This can be a one-time task, or a task that is repeated multiple times, in which case we assume that recharging can be done sufficiently fast by an operator, for example by exchanging a battery or gas cylinder. Examples of tasks for each level of task duration are:

-

1.

Physics research, demonstrating a principle ( ≈ 1 min).

-

2.

Search and rescue ( ≈ 1 h).

-

3.

Robotic hand prosthesis ( ≈ 1 day).

-

4.

Implantable prosthesis ( ≿ 1 week, in the case of an implant possibly years).

We place Octobot20 and the modular robot25 in the first level (physics demonstrator), while the ring-oscillator walker26, relaxation oscillator robot29, the untethered multi-gait robot23, and the twisted LCE strip robot30 appear in the second level, assuming a limited task such as exploration of a limited perimeter as target applications. We classify the robotic fish22 as either level 2 or 3, for two different use cases: a more dedicated mission or a more general long-term monitoring task.

On the vertical axis, we indicate independence, i.e., the ability to meet the required operating time independently of external intervention. We define 4 levels:

-

1.

Complete dependency on a tether for power.

-

2.

Operates without a tether, but does not have enough energy supply to complete a typical task.

-

3.

Operates without a tether for the time required to complete its task. This can be a one-time task, or a repeating task, in which case the robot needs to be recharged by an operator in between task executions.

-

4.

Able to extract all required energy from its surroundings, without user intervention.

The relaxation oscillator robot is permanently tethered (level 1). The ring-oscillator walker is limited by its energy supply in fulfilling its task (level 2), while the robotic fish is able to swim for 40 min (i.e., close to 1 h) on a single charge, placing it at level 3 or 2 depending on the use case. The untethered multi-gait robot has enough energy supply for its task, placing it at level 3. Octobot and the modular robot are also level 3, where it should be noted that their task as a demonstrator is much shorter than the exploring robots. As a result, their energy-autonomy scores lower. The twisted LCE strip robot harvests its energy from its specific environment (level 4).

Operating in specific niches, i.e., on a hot surface and underwater, respectively, the twisted LCE strip robot and the robotic fish achieve the highest energy-autonomy indices. As such, their high ratings demonstrate the importance of the environment also for a robot’s energy-autonomy. We note that for energy-autonomy, iso-autonomy lines are essentially identical to the total operating time before intervention is needed. Still, we find that the explicit distinction between the requirement on the one hand and the ability to fulfill the requirement independently on the other hand helps our understanding.

On our scale, both task duration and independence for the heart are rated the highest level 4. However, this extreme energy-autonomy is only possible because the heart’s environment is highly specialized to provide this energy. This is a reminder that autonomy in nature is not absolute, but is achieved in interdependence with a larger system.

The future of bio-inspired autonomy in soft robotics

From the classification of existing soft robotic examples and the human heart, we observe that although their energy-autonomy is still significantly lower, soft robots already have comparable control-autonomy. We conclude that a soft robot with state-of-the-art autonomy can already be usefully applied as part of a larger system, i.e., in a favorable environment. This is a significant shift from the prevailing implicit perspective that a soft robot operates in a vacuum, and still needs to be fully autonomous.

Natural systems like the human heart provide beautiful examples of embodied intelligence and interdependent autonomy. Cells and organs jointly modulate a shared environment, consuming and providing energy, and processing multiple inputs in parallel via physical interactions, including mechanical interactions. Studying such natural mechanisms reveals alternative routes to highly integrated and robust adaptive behavior.

Next steps in control-autonomy

These observations point to two interesting future lines of research in soft robotics. The first is the study of principles of autonomy in nature, using soft robotics as a platform. This ambitious program clearly requires a highly multi-disciplinary effort, combining insights from biology, neurology, cognition, non-linear dynamics, bio-mechanics and robotics. Examples from existing literature include synthetic multi-cellular assemblies39 and bio-hybrids40 that harness the innate abilities of living cells in novel configurations, homeostatic materials41 achieved by chemo- mechano-chemical self-regulation, and control algorithms based on central pattern generator circuits42. Soft robotics may play an increasingly prominent role as the importance of embodied intelligence and compliance become more widely recognized43,44,45,46.

As the second research line, robots with limited levels of autonomy will increasingly find real-world applications. Think of versatile grippers in industry and agriculture, rovers sent out for exploration, or medical implants. As illustrated by the human heart, complete control-autonomy is not always required to robustly achieve a desired goal in a dynamic environment. As a practical industrial example, a gripper that is permanently mounted to a stationary robotic arm is not hindered in its performance by a permanent tether for energy supply and control inputs. Therefore, it is possible to design useful soft robotic applications today. In this applied line of research, we foresee that the more holistic view on control (harnessing interactions with the environment) proposed in this perspective will gradually enable applications that perform better and require less user intervention.

Admittedly, stating that the environment is important is very different from knowing how to design for emergent behavior. For the moment, this design problem needs to be tackled on a case-by-case basis, precisely because it depends so strongly on the specifics of an environment. This is where both research lines may strengthen each other. Application-based case studies can lead to hypotheses about more general principles. Conversely, general principles found in fundamental research can be applied in other applications than where they were discovered, in order to improve autonomy. For example, our relaxation oscillation walker29 prompts the question if small networks of relaxation oscillators may be designed for many other tasks, inspired by the fact that networks of oscillators are omnipresent in nature, most prominently in neuronal systems including brains.

Next steps in energy-autonomy

A recent review of energy storage and energy conversion methods concludes that energy-autonomy for infinite time is beyond the current state-of-the-art47. Fundamentally, some form of energy harvesting is required for infinite-time energy-autonomy, but existing methods do not provide substantial power levels in general. It therefore seems that energy-autonomy for prolonged operation will remain out of reach in the near future for most applications.

Although this seems an important restriction, we circumvent this issue by defining energy-autonomy in the context of a task and environment. If a search-and-rescue robot operates for 1 h and within that hour finds a survivor who can subsequently be saved, this robot is clearly very useful. But of course, this account is ultimately unsatisfactory. Fundamentally, because natural examples are energy-autonomous in their environment. And practically, there are many applications for which we still cannot create sufficiently energy-autonomous robots. In this context, the twisted LCE strip robot30 beautifully demonstrates that it is indeed possible to design an energy-autonomous robot, but only when considering a highly specific environment and task.

Adding to the existing discussion, we propose that for fluid-driven soft robots a promising route to improving energy-autonomy is increasing system-level energy efficiency. This should of course be complemented by progress on all other fronts (supply, storage, conversion) as well, but specifically energy efficiency is not often analysed in soft robotics. When it is, values on the order of ≈1% are not uncommon48, even though the isolated process of inflating and deflating an (unloaded) actuator can be over 90% efficient49. This suggests ample potential for energy savings. One of the reasons is that during actuation, significant energy is stored in compression of air and elastic deformation of the actuator. In all presented examples of walking robots, for example, pressurized air is vented at the end of each cycle. As an example of improving efficiency by reusing stored energy, venting to an intermediate pressure instead of atmosphere can improve system efficiency by up to 50%50, or harvest up to 44% of the stored energy51. A better understanding of energy flows and efficiency in soft robotics will be a relatively straight-forward route to significantly improving energy-autonomy in soft robots, for example by reusing energy that is otherwise exhausted.

Interestingly, once efforts to improve efficiency lead to robots that require significantly less energy, this not only directly improves energy-autonomy, but also increases the impact of energy harvesting systems that can be integrated with soft robotics, such as organic photovoltaics52 or microbial fuel cells53.

Outlook

We introduce definitions of autonomy that enable comparison between soft robots and help in the analysis of autonomy in natural examples. We note two aspects of natural autonomy that we believe can help advance the field of soft robotics. Firstly, organisms are largely independent of external control in harvesting natural resources, but they still strongly depend on their environment. This becomes even more clear when looking at organs instead of organisms. Similarly, we state that in soft robotic applications complete autonomy should not be a goal per se, but that we should strive to design a robot with an appropriate level of autonomy for its task and environment. Secondly, organisms need to be well adapted to their specific environment or niche to function autonomously. By extension, we claim that when defining autonomy for (soft) robots, a crucial but often overlooked first step should be an explicit description of a robot’s task and environment. Such a description helps to identify opportunities for achieving improved autonomy. That is because according to the embodied intelligence paradigm behavior is the result of not only a robot’s internal structure ("brain and body”), but also external interactions. As such, the task environment may pose challenges and limitations, but also provides resources to enhance energy- as well as control-autonomy. An important direction for future soft robotics research is, therefore, to study how such interactions are leveraged in nature, and to invent bio-inspired methods to leverage them in soft robotics.

References

Forterre, Y., Skotheim, J. M., Dumais, J. & Mahadevan, L. How the Venus flytrap snaps. Nature 433, 421–425 (2005).

Dagenais, P., Hensman, S., Haechler, V. & Milinkovitch, M. C. Elephants evolved strategies reducing the biomechanical complexity of their trunk. Curr. Biol. 31, 4727–4737.e4 (2021).

Bennet Clark, H. C. The energetics of the jump of the locust Schistocerca gregaria. J. Exp. Biol. 63, 53–83 (1975).

Rosario, M. V., Sutton, G. P., Patek, S. N. & Sawicki, G. S. Muscle-spring dynamics in time-limited, elastic movements. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283, 20161561 (2016).

Roberts, T. J. & Azizi, E. Flexible mechanisms: the diverse roles of biological springs in vertebrate movement. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 353–361 (2011).

Hawkes, E. W., Blumenschein, L. H., Greer, J. D. & Okamura, A. M. A soft robot that navigates its environment through growth. Sci. Robot. 2, eaan3028 (2017).

Pal, A., Goswami, D. & Martinez, R. V. Elastic energy storage enables rapid and programmable actuation in soft machines. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1906603 (2020).

Ilievski, F., Mazzeo, A. D., Shepherd, R. F., Chen, X. & Whitesides, G. M. Soft robotics for chemists. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 50, 1890–1895 (2011).

Gorissen, B., Melancon, D., Vasios, N., Torbati, M. & Bertoldi, K. Inflatable soft jumper inspired by shell snapping. Sci. Robot. 5, eabb1967 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Leveraging elastic instabilities for amplified performance: spine-inspired high-speed and high-force soft robots. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz6912 (2020).

Brown, E. et al. Universal robotic gripper based on the jamming of granular material. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18809–18814 (2010).

Shintake, J., Cacucciolo, V., Floreano, D. & Shea, H. Soft robotic grippers. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707035 (2018).

Terryn, S., Brancart, J., Lefeber, D., Assche, G. V. & Vanderborght, B. Self-healing soft pneumatic robots. Sci. Robotics 2, eaan4268 (2017).

Vergara, A., Lau, Y.-S., Mendoza-Garcia, R.-F. & Zagal, J. C. Soft modular robotic cubes: toward replicating morphogenetic movements of the embryo. PLoS One 12, e0169179 (2017).

Della Santina, C., Duriez, C. & Rus, D. Model-based control of soft robots: A survey of the state of the art and open challenges. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 43, 30–65 (2023). This article gives an outstanding overview of the successes and remaining challenges in the application of a more traditional control approach to soft robots.

Pfeifer, R. & Bongard, J. How the Body Shapes the Way We Think (The MIT Press, 2006). This book describes the embodied intelligence paradigm, which understands intelligent behavior as the result of interactions between brain, body, and environment of a (natural or artificial) agent.

Hauser, H., Nanayakkara, T. & Forni, F. Leveraging morphological computation for controlling soft robots: Learning from nature to control soft robots. IEEE Control Syst. Mag. 43, 114–129 (2023). This article introduces soft robotics and morphological computation, argues that the combination is useful for control, and illustrates this with several examples.

Boron, W. & Boulpaep, E. L. Medical Physiology (Elsevier, 2016).

MacDonald, E. A., Rose, R. A. & Quinn, T. A. Neurohumoral control of sinoatrial node activity and heart rate: insight from experimental models and findings from humans. Front. Physiol. 11, 170 (2020).

Wehner, M. et al. An integrated design and fabrication strategy for entirely soft, autonomous robots. Nature 536, 451–455 (2016). This article demonstrates the first soft robot that requires no external energy or control input.

Katzschmann, R. K., Marchese, A. D. & Rus, D. Hydraulic autonomous soft robotic fish for 3D swimming. In Hsieh, M. A., Khatib, O. & Kumar, V. (eds.) Springer Tracts Adv. Robot., vol. 109, 405–420 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Katzschmann, R. K., DelPreto, J., MacCurdy, R. & Rus, D. Exploration of underwater life with an acoustically controlled soft robotic fish. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar3449 (2018).

Tolley, M. T. et al. A resilient, untethered soft robot. Soft Robot. 1, 213–223 (2014).

Shepherd, R. F. et al. Multigait soft robot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20400–20403 (2011).

Oliveri, G., van Laake, L. C., Carissimo, C., Miette, C. & Overvelde, J. T. Continuous learning of emergent behavior in robotic matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2017015118 (2021).

Drotman, D., Jadhav, S., Sharp, D., Chan, C. & Tolley, M. T. Electronics-free pneumatic circuits for controlling soft-legged robots. Sci. Robot. 6, eaay2627 (2021).

Rothemund, P. et al. A soft, bistable valve for autonomous control of soft actuators. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar7986 (2018).

Preston, D. J. et al. A soft ring oscillator. Sci. Robot. 4, eaaw5496 (2019).

Van Laake, L. C., De Vries, J., Kani, S. M. & Overvelde, J. T. B. A fluidic relaxation oscillator for sequential actuation in soft robots. Matter 5, 2898–2917 (2022). This article demonstrates an embodied control method where a single fluidic circuit can activate soft robotic actuators in multiple different sequences, without any control input.

Zhao, Y. et al. Twisting for soft intelligent autonomous robot in unstructured environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200265119 (2022).

Pal, A., Restrepo, V., Goswami, D. & Martinez, R. V. Exploiting mechanical instabilities in soft robotics: control, sensing, and actuation. Adv. Mater. 33, e2006939 (2021).

McDonald, K. & Ranzani, T. Hardware methods for onboard control of fluidically actuated soft robots. Front. Robot. AI 8, 720702 (2021).

Hoang, S., Karydis, K., Brisk, P. & Grover, W. H. A pneumatic random-access memory for controlling soft robots. PLoS One 16, e0254524 (2021).

Hubbard, J. D. et al. Fully 3D-printed soft robots with integrated fluidic circuitry. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe5257 (2021).

Song, S., Joshi, S. & Paik, J. CMOS-inspired complementary fluidic circuits for soft robots. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100924 (2021).

Decker, C. J. et al. Programmable soft valves for digital and analog control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205922119 (2022).

Zhai, Y. et al. Desktop fabrication of monolithic soft robotic devices with embedded fluidic control circuits. Sci. Robot. 8, eadg3792 (2023).

Conrad, S. et al. 3d-printed digital pneumatic logic for the control of soft robotic actuators. Sci. Robot. 9, eadh4060 (2024).

Kriegman, S., Blackiston, D., Levin, M. & Bongard, J. A scalable pipeline for designing reconfigurable organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 1853–1859 (2020).

Lee, K. Y. et al. An autonomously swimming biohybrid fish designed with human cardiac biophysics. Science 375, 639–647 (2022).

He, X. et al. Synthetic homeostatic materials with chemo-mechano-chemical self-regulation. Nature 487, 214–218 (2012).

Ijspeert, A. J., Crespi, A., Ryczko, D. & Cabelguen, J. M. From swimming to walking with a salamander robot driven by a spinal cord model. Science 315, 1416–1420 (2007).

Man, K. & Damasio, A. Homeostasis and soft robotics in the design of feeling machines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 446–452 (2019).

Rossiter, J. Soft robotics: the route to true robotic organisms. Artif. Life Robot. 26, 269–274 (2021).

Cianchetti, M. Embodied intelligence in soft robotics through hardware multifunctionality. Front. Robot. AI 8, 724056 (2021).

Kaspar, C., Ravoo, B. J., van der Wiel, W. G., Wegner, S. V. & Pernice, W. H. P. The rise of intelligent matter. Nature 594, 345–355 (2021).

Aubin, C. A. et al. Towards enduring autonomous robots via embodied energy. Nature 602, 393–402 (2022).

Chun, H. T. D., Roberts, J. O., Sayed, M. E., Aracri, S. & Stokes, A. A. Towards more energy efficient pneumatic soft actuators using a port-hamiltonian approach. 2019 IEEE Int. Conf. Soft Robot. (RoboSoft)277–282 (2019).

Mosadegh, B. et al. Pneumatic networks for soft robotics that actuate rapidly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 2163–2170 (2014).

Chou, C. P. & Hannaford, B. Measurement and modeling of McKibben pneumatic artificial muscles. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 12, 90–102 (1996).

Wang, T., Song, W. & Zhu, S. Analytical research on energy harvesting systems for fluidic soft actuators. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 15, 172988141875587 (2018).

Abolhosen, A. M. R. et al. Functional soft robotic composites based on organic photovoltaic and dielectric elastomer actuator. Sci. Rep. 14, 9953 (2024).

Philamore, H., Rossiter, J., Stinchcombe, A. & Ieropoulos, I. Row-bot: An energetically autonomous artificial water boatman. 2015 IEEE/RSJ Int. Conf. Intell. Robots Syst. (IROS), 3888–3893 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 767195. This work is part of the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and was performed at the research institute AMOLF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: L.C.v.L. and J.T.B.O.; Methodology: L.C.v.L.; Writing - Original Draft: L.C.v.L.; Writing - Review & Editing: L.C.v.L. and J.T.B.O.; Visualization: L.C.v.L.; Supervision: J.T.B.O.; Funding Acquisition: J.T.B.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Ramses Martinez and Falk Tauber for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Laake, L.C., Overvelde, J.T.B. Bio-inspired autonomy in soft robots. Commun Mater 5, 198 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00637-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00637-7

This article is cited by

-

Multi-functional liquid crystal oligomer networks for human-interactive self-regulation

Communications Materials (2025)

-

Lateral Undulation and Force Prediction in Soft Robotic Fish: A Systematic Approach

Journal of Bionic Engineering (2025)