Abstract

The occurrence of high stress concentrations in reactor components is a still intractable phenomenon encountered in fusion reactor design. Here, we observe and quantitatively model a non-linear high-dose radiation mediated microstructure evolution effect that facilitates fast stress relaxation in the most challenging low-temperature limit. In situ observations of a tensioned tungsten wire exposed to a high-energy ion beam show that internal stress of up to 2 GPa relaxes within minutes, with the extent and time-scale of relaxation accurately predicted by a parameter-free multiscale model informed by atomistic simulations. As opposed to conventional notions of radiation creep, the effect arises from the self-organisation of nanoscale crystal defects, athermally coalescing into extended polarized dislocation networks that compensate and alleviate the external stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The central engineering challenge in realising commercially viable fusion power-generating reactors lies in the degradation of materials in components surrounding the fusion plasma1. Structural components inside the vacuum vessel are exposed to extreme conditions2, involving high magnetic fields, gravitational loads, plasma disruptions, and unprecedented levels of neutron and gamma radiation3 that continuously generate microscopic defects, leading to severe degradation of properties of materials critical to their intended function. Furthermore, spatio-temporal variations in irradiation exposure and temperature induce stress concentrations of sufficient magnitude to threaten the integrity of load-bearing or physical barrier4,5,6 components.

The tendency of metals to undergo steady viscoplastic deformation when subjected to mechanical stress at elevated temperatures, known as creep, is of pivotal significance to the structural integrity of a reactor. Irradiation by high-energy particles significantly accelerates creep, causing deformation rates orders of magnitude higher than thermal creep under the otherwise equivalent stress7,8. However, mechanistic understanding of the phenomenon proves elusive, partly because it is challenging to design experiments enabling accurate measurements under simultaneous high irradiation fluence, mechanical, and thermal loads.

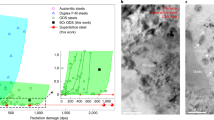

In particular, the role of temperature remains undetermined, due to the scarcity of published experimental data on irradiation creep at low temperatures. Conventional argument suggests that creep rates increase with temperature due to the enhanced thermal diffusion of microstructural defects, mediating the viscoplastic flow. In apparent contradiction with this argument, measurements of low-temperature irradiation creep in austenitic and ferritic/martensitic steels9, Inconel X-75010, molybdenum11, and tungsten12 suggest that at low temperatures the irradiation creep occurs at an anomalously high rate, decreasing as a function of temperature, only to increase again at higher temperatures. Low temperatures, along with large temperature and radiation exposure gradients, are expected in the actively cooled reactor components, making a rational model for the phenomenon a requirement for an expert fusion reactor design.

In this study, we develop a comprehensive quantitative treatise of the anomalous low-temperature irradiation creep phenomenon by combining custom-designed experiments with in situ measurement capabilities and a parameter-free multiscale model. Figure 1 illustrates a time-resolved observation of stress relaxation in a 16 μm thin tungsten wire – thinner than a human hair – under exposure to highly energetic ions. Initially, the wire is stretched until a specified tensile load is reached. Subsequently, the wire is exposed to the ion beam while the force required to maintain its length is monitored. Despite the wire remaining at a temperature where no thermally-driven creep occurs, our observations reveal an initial rapid relaxation of the force occurring within minutes, followed by slower relaxation plateauing over a few hours. Significantly, in Fig. 1f we observe the extent of relaxation to be linearly proportional to the external load, which is in remarkable qualitative and quantitative agreement with predictions derived from an in silico replication of the experiment through a parameter-free model. Our analysis shows that the relaxation is non-linear and involves the coarsening of microscopic defects under external stress. Since only 4% of the wire material is exposed to high-energy ions, the extent of the measured relaxation suggests that locally in the irradiated surface layer, the applied tensile loads of up to 2 GPa relax entirely and solely through the anomalous fast low-temperature irradiation creep.

a A thin tungsten wire of length 15 mm and diameter 16 μm is subjected to external tensile load fz, after which a central wire section of 4 mm length is exposed to a beam of 20.3 MeV W6+ ions whilst monitoring the force required to maintain the initial elongation. b The ion beam damages a thin surface layer of about 2 μm thickness, as seen in the simulated exposure profile in the cross-section. c Upon exposure of the wire to the beam, rapid relaxation of the load is observed. d, e While the wire is initially under uniform tensile stress, a multi-scale simulation of the developing internal stress reveals that in the irradiated surface layer (A), the tensile stress relaxes completely and even becomes compressive, while in the unexposed region deeper in the wire (B), the tensile stress increases to balance the expansion of the irradiated layer. f The final magnitude of the radiation-exposure-induced stress relaxation is proportional to the magnitude of the initial tensile stress, suggesting that the relaxation is strongly biased by the external stress. Error bars indicate the standard error over multiple experiments. The shaded region indicates the 3σ-confidence interval of the simulation prediction, with uncertainty originating from the stochasticity of the atomistic data underlying the surrogate model.

Results

Time-resolved stress relaxation measurement

To measure the time-resolved irradiation-induced stress relaxation, it is necessary to select an appropriate high-energy particle source. Neutrons penetrate deep into materials, allowing for testing of bulk samples, but the conditions in a typical materials test reactor rarely permit in situ mechanical testing. Neutron activation of materials also complicates handling, with low dose rate implying long exposure times. For these reasons, we chose irradiation by high-energy heavy ions. These are readily available, can be produced in the form of intense beams, and cause no activation. It is also possible to incorporate a mechanical testing setup into an ion accelerator beam line.

As high-energy heavy ions have the penetration depth of only a few μm, the exposed zone should span many grains in order to replicate bulk-like irradiation conditions. We selected potassium-doped (60–75 ppm) cold-drawn tungsten wires, as tungsten is the prime candidate material for plasma-facing components due to its high melting point and high thermal conductivity. The wires are industrially produced with diameters as small as 16 μm and feature highly elongated nanoscale grains, as shown in Fig. 2a. Extensive studies of mechanical properties13,14, deuterium retention15, and post-irradiation properties16 of this material are available. To prevent the implantation of impurities, we employ a beam of 20.3 MeV W6+ ions. These ions penetrate about 2 μm into tungsten, exposing about 16% of the wire cross-section. Surface effects are negligible here, as due to the small grain size, most of the grains (~95%) in the irradiated volume fraction do not have free surfaces.

a Ultrafine-grained microstructure of the 16 μm tungsten wire. Left: cross-section images taken using a scanning electron microscope in backscattered electron contrast mode. Right: longitudinal section using secondary electron contrast. b Schematic overview of the ion beam path during the experiment. From left to right: beam limiting aperture, first suppression electrode, 16 μm wire sample, 102 μm measuring wire, second suppression electrode. c Tensile stress (blue) and ion current (orange) during the experiment. Black circles indicate the points where experimental measurements were performed between the irradiation intervals.

To enable a time-resolved measurement of the stress relaxation phenomenon, a dedicated experiment comprising a tensile testing machine mounted in a vacuum vessel was set-up at a beamline of the 3 MV tandem accelerator at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics. The 15 mm long wire samples are mounted between two crossheads of the machine and mechanically tensioned to a uniaxial stress ranging from 0.5 GPa to 2.0 GPa, which is still in the elastic region. While the strain is kept constant, a central wire section of 4 mm length is exposed to the ion beam. Since almost all of the impacting ions’ kinetic energy is absorbed in the wire, the sample’s temperature rises to at most 100°C. We refer to the Supplementary Discussion for an estimation of the sample heating. No thermal creep is expected at such low homologous temperature (T < 0.1 Tmelt). To correct for the influence of the resulting thermal expansion on the force measurement, the beam is periodically turned off at intervals of 5 min to 30 min. The sample cools down during these intervals, allowing for the measurement of the actual force drop. The ion fluence is determined by measuring the electric current flowing through the wire, from which the dose in units of displacements per atom (dpa)17 is computed using the number of displacements per colliding ion from the SRIM software18. The samples are exposed to a peak dose of up to 6 dpa over a typical 6 h duration of an experiment. The measured forces are adjusted for shifting and relaxation of the load cell and measurement setup, and further steps are taken to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the measured ion current, see the Methods sections. Figure 2b schematically illustrates the irradiation part of the experiment.

Insights from in silico testing

While the extent of relaxation in the irradiated volume can be numerically estimated, such estimates do not account for the transient and heterogeneous nature of the stress field developing over the course of irradiation. Similarly, even if microstructural evolution were precisely characterised using imaging techniques, without understanding the physical principles governing it, this insight would not be transferable to complex geometries involving spatially or temporally varying stress fields.

We have opted to develop a virtual representation of the wire experiment based on a small number of precisely defined and tested theoretical principles. The stress relaxation mechanism is described by a surrogate model, derived from the data obtained directly from atomistic simulations, with no additional parameters adjusted to fit the experimental result. In this way, the model has predictive capabilities over a well-defined range of experimental conditions. By embedding the surrogate model into a finite element representation of the wire, we bridge the gap between atomic and micro-mechanical scales, arriving at a digital shadow of the experiment. Atomistic simulations also provide full and precise information about the microstructure, enabling the in silico identification of the mechanisms responsible for the observed relaxation.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been used to successfully predict properties of materials exposed to irradiation without the need for adjustable parameters19,20,21. While MD simulations enable direct and parameter-free analysis of response of radiation effects to thermal and mechanical loads, it would require over 1012 atoms just to represent a 1 μm long wire section. The largest simulation reported in literature involved 2 × 109 atoms22. Consequently, with MD we cannot explicitly simulate the heterogeneous dose profile attenuating on the micrometer scale. In what follows, we employ MD to describe the behaviour of a representative volume element (RVE) under irradiation. The simulation operates as a black box; given an external homogeneous stress, we obtain data on dimensional changes of an RVE during irradiation.

In our atomistic simulations, see Fig. 3, the initially pristine tungsten single crystals were exposed to atomic recoils representative of those initiated by 20.3 MeV W6+ ions, while maintaining a specified external uniaxial load \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\). These recoils lead to the generation of self-similar cascades of atomic displacements, ultimately resulting in the formation of crystal defects that cause dimensional changes of the RVE, here described as eigenstrains parallel and perpendicular to the uniaxial stress direction, \({\varepsilon }_{\parallel }^{* }\) and \({\varepsilon }_{\perp }^{* }\), respectively. While the simulated dose-rate of 20 dpa/μs is nine orders of magnitude higher than in experiment, at a temperature of 100 °C, vacancies are effectively immobile with the mean time between migration events of 1 year. Self-interstitial atom defects, on the other hand, are mobile even at cryogenic conditions23, as their migration barrier is sufficiently small to be overcome by the thermal fluctuations introduced by collision cascades and stress fluctuations arising from the coarsening microstructure. As a result, microstructural evolution follows an effectively athermal pattern, both in experiment and in simulations21.

a Atomistic simulations generate data on deformation eigenstrains for a representative volume element under irradiation and external uniaxial stress. Radiation damage is simulated by assigning randomly chosen atoms in a tungsten crystal (white cutaway) recoil energies, drawn from scattering events with 20.3 MeV W6+ ions, leading to the initiation of collision cascades that result in the formation of nanoscale self-interstitial (red) and vacancy (blue) defects, shown here for 1 GPa. Eigenstrains are extracted in directions parallel (\({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\parallel }^{* }\)) and perpendicular (\({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\perp }^{* }\)) to the uniaxial stress direction. b A surrogate model is matched to the data using maximum likelihood estimation. Solid lines and shaded areas indicate the mean value and standard deviation, respectively, of eigenstrains from five repeated simulations per stress value. c The surrogate model, when adjusted to produce isotropic expansion at zero stress (see text), is in agreement with in situ measurements of elongation strain of tungsten irradiated by fission fragments at 20 K under tension.

Because of the discrete nature of atomic recoils, MD simulations inherently generate discrete datasets of eigenstrain \(\{({\phi }_{0},{{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{0}^{* }),({\phi }_{1},{{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{1}^{* }),\,\cdots \,,({\phi }_{N},{{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{N}^{* })\}\) over dose ϕi in units of dpa. Moreover, independent MD simulations for the same uniaxial stress yield different eigenstrain datasets due to the stochasticity inherent to collision cascades24 and dislocation motion25,26. Since these eigenstrains are intended for the use in a homogenised finite element model, we require a surrogate model representing the expectation value μ and variance s2 of eigenstrains as continuous functions of dose and stress. We express the probability of drawing a parallel or perpendicular eigenstrain component \(({\phi }_{i},{\varepsilon }_{i}^{* })\) from a normal distribution \({{\mathcal{N}}}(\mu ,{s}^{2})\) by

where μ(ϕ; θ) and s(ϕ; θ) are cubic spline functions with unknown knot heights θ. The likelihood to draw the entire eigenstrain data for a common external stress \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\) from the model is

By maximising the log-likelihood over θ,

we obtain a maximum likelihood estimate for \(\hat{{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}\) best matching the data. This process is applied to ε∥ and ε⊥ components, independently for each simulated stress. Finally, μ(ϕ; θ) is interpolated in stress-space using cubic splines, resulting in continuous representations of eigenstrains \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\parallel }^{* }(\phi ,{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}})\) and \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\perp }^{* }(\phi ,{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}})\). From these, a diagonal eigenstrain tensor is formed with \({{{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\rm{MD}}}}^{* }(\phi ,{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}})={{\rm{diag}}}({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\perp }^{* },{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\perp }^{* },{\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{MD}}},\parallel }^{* })\). The eigenstrain input data are obtained from five repeated MD simulations for each stress \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\) between −1.0 GPa and 2.0 GPa in increments of 0.5 GPa. Additional details on MD simulations are given in the Methods section.

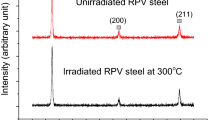

The resulting surrogate model predicts elongation strains consistent with in situ measurements of cold-rolled tungsten samples irradiated under constant tension at cryogenic conditions12, see Fig. 3c. For this specific comparison, we constrained the surrogate model to yield isotropic expansion at zero external stress; this constraint is related to the grain shape, and is discussed in more detail below. Motivated by the favourable comparison between the model and experiment, we proceed under the assumption that the surrogate model is transferable to polycrystalline samples. We note that the influence of grain orientation and texture on athermal irradiation creep is a largely unexplored subject.

It remains to formulate a model for the incremental accumulation of eigenstrain ε* during irradiation. In experiment, the wire is initially in a uniform stress state that becomes non-uniform upon exposure to the spatially attenuating ion beam. The surrogate model, however, describes dimensional changes of a RVE irradiated under a constant homogeneous external stress. The eigenstrain induced by a complex microstructure generally comprises contributions with varying degrees of reversibility in response to a changing stress, and the same is expected to hold true for microstructures formed by irradiation. Atomistic simulations show that eigenstrain formed under irradiation is largely irreversible; a momentary change in external stress has little effect on the eigenstrain. A similar observation was recently reported for aluminium irradiated under external stress27. Figure 3a suggests that at high dose, interstitial defects preferentially arrange themselves into extended structures, such as dislocation networks or new crystal planes28, which cause a dimensional change that is no longer affected by external stress. Motivated by this observation, we assume that eigenstrains accumulate irreversibly over the course of irradiation, with the accumulation driven by the surrogate model evaluated for the instantaneous and local elastic stress σel(r, t) and dose ϕ(r, t) fields:

where σel = σ − σ* is the elastic stress tensor, with σ* ≡ C: ε* using the elastically isotropic stiffness tensor C of tungsten29.

Lastly, because elastic fields have long range, variations in the local stress are implicitly dependent on the spatially heterogeneous stress field involving the entire wire. The gap in length scales between the nanoscale RVE and the microscale wire is bridged by representing the effect of eigenstrain by a body-force acting in a linear elasticity framework5, expressed as f* = − ∇ ⋅ σ*:

We solve for the stress tensor field σ using a finite element method, with the time propagation scheme described in the Methods section.

In Fig. 4a, we compare the in situ measurements and in silico predictions of stress relaxations for the initial applied stress of 1 GPa. Over time, we observe in the stress profile shown in Fig. 1d, the emergence of mutually counterbalancing compressive and tensile elastic stresses in the irradiated and unirradiated regions, respectively. The material exposed to irradiation deforms plastically to accommodate the external tensile stress, resulting in local stress relaxation. This deformation likewise gives rise to a long-ranged elastic tensile stress field extending well into the unexposed region, increasing the tensile stress beyond its initial value, as depicted in Fig. 1e.

a Comparison of four irradiation-induced stress relaxation experiments to a parameter-free simulation using the virtual wire model under an initial uniaxial tensile stress \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\) of 1 GPa. The model predicts a relatively small degree of relaxation, in agreement with experiment, due to the small volume fraction of the irradiated volume of the wire. b Predicted stress relaxation curves for a hypothetical homogeneous irradiation scenario under various initial uniaxial tensile and compressive stresses. Most of the relaxation is predicted to occur within the first 0.3 dpa.

The measured and predicted final relaxations for the various initial stresses are shown in Fig. 1f. The predictions are in good qualitative agreement with experimental results, with an overestimation of approximately 20%. The amount of relaxation appears to obey a linear relationship with the initial external stress \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\). Specifically, the simulation data follows the curve given by \(\Delta {\sigma }^{{{\rm{sim}}}}=14.9\,{{\rm{MPa}}}+0.050\,{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\), whereas the experimental data follows \(\Delta {\sigma }^{\exp }=18.1\,{{\rm{MPa}}}+0.036\,{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\). Assuming that at high dose, the elastic stress relaxes completely within the irradiated region, the fraction of relaxed stress should be close to the irradiated volume fraction Virr/V = 0.04; this is in agreement with the proportionality constants of the linear relations. Bearing this in mind, the major source of uncertainty in our virtual wire model originates not from the stochastic uncertainty of atomistic data, but rather from the dose profile determining the irradiated volume fraction.

We observe that the irradiated region relaxes to a lightly compressive state of −200 MPa instead of an entirely stress-free state. This is a finite-size effect originating from atomistic simulations, where we used a simulation cell with a shape elongated along the uniaxial loading direction (32 × 32 × 80 nm3). In a stress-free simulation, at low dose, the interstitial loops are in prismatic orientation, with their habit planes oriented perpendicular to the Burgers vectors, thus giving rise to isotropic volumetric swelling. As the loops grow under continued irradiation, they interact with their own periodic image across the shorter simulation cell sides, eventually forming extended dislocation networks or new complete crystal planes; as a result the initially isotropic expansion becomes preferentially polarised in the loading direction. For the same reason, the final induced relaxation, shown in Fig. 1f, does not vanish at zero initial stress, as tensile eigenstrain develops under irradiation even in the absence of external stress. The same effect is also observed in experiment, where the grains are similarly elongated along the uniaxial loading direction (~50 × 50 × 1000 nm3), suggesting a genuine irradiation growth phenomenon caused by the anisotropic grain microstructure.

Finally, to assess the potential beneficial effect of fast low-temperature stress relaxation under a realistic reactor operating scenario, we applied the model to a hypothetical case involving a homogeneously irradiated wire, illustrated in Fig. 4b. This scenario is experimentally inaccessible with heavy ion irradiation due to their limited implantation range and is, instead, more representative of neutron irradiation. Using the virtual wire, we can also predict relaxation under a compressive stress, a condition that cannot be tested in our experiments where the wire would buckle. Our predictions exhibit the rapid complete relaxation of the initial stress within 0.3 dpa of exposure. In the same figure, we also show relaxation as predicted by a surrogate model constrained to expand isotropically under stress-free conditions (dotted lines), which is more representative of tungsten with isotropic grain microstructure. The constrained surrogate model was also used in the comparison in Fig. 3c.

Discussion

Inspecting the atomistic simulations underpinning the surrogate model, we have identified three distinct mechanisms contributing to stress relaxation occurring over some distinct dose and stress intervals. Up to the dose of about 0.05 dpa, dislocations form a dispersed microstructure, primarily consisting of \(1/2\left\langle 111\right\rangle\)-type interstitial loops shown in Fig. 5a. In the absence of external stress, the prismatic loops generate isotropic volumetric swelling. When external stress is applied, the loop habit planes tilt to lower the elastic interaction energy30, resulting in a polarised eigenstrain28,31. This tilting is balanced by an increase in the dislocation line tension energy32. Consequently, the degree of anisotropy increases with increasing external stress.

a Irradiation creep is driven by the coarsening and coalescence of highly mobile self-interstitial clusters. At low dose, irradiated microstructure contains mostly interstitial-type (red) and rarely vacancy-type (blue) dislocation loops, as well as dispersed vacancies. With further exposure, the interstitial-type loops grow and coalesce, eventually forming a complex, system-spanning dislocation network of mixed character which enables plastic deformation of the crystal. Shown are defect clusters (N > 2) and dislocations (1/2\(\left\langle 111\right\rangle\): green, \(\left\langle 100\right\rangle\): red) as identified with the Wigner-Seitz and DXA methods, respectively. The reference crystal for Wigner-Seitz analysis is chosen to minimise the number of point defects, allowing for direct visualisation of plastic deformation. b Interstitial and vacancy-type loops orient themselves into opposing directions relative to the external uniaxial stress direction, which leads to a stress-bias in the eventual formation of the dislocation network. Shown are the mean alignments for a given dose (dots) and spline-interpolated values (line) with standard error (shaded). The dashed line indicates prismatic alignment. c The extent of volume swelling is independent of external stress and can be well estimated by 0.64 times the vacancy concentration, with the numerical factor arising from comparison of interstitial and vacancy defect relaxation volumes, see text. Shaded areas indicate the standard error over five repeated simulations.

At higher doses, in the transient phase occurring between approximately 0.05 and 0.10 dpa, the loops grow and coalesce, eventually forming extended networks or even complete crystal planes28,31. The planes form preferentially normal to, or parallel to, the uniaxial tensile and compressive stress directions, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 5a (plastic). Plane formation contributes significantly to the overall dimensional change. As dislocations structures transform into crystal planes, the counterbalancing effect of line tension vanishes, and their partially polarised relaxation volumes become fully polarised.

If the external stress is large, \(| {\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}|\) ≳ 1 GPa, the dislocation network can additionally undergo slip; in an individual atomistic simulation, this is manifested though a substantial change23 in eigenstrain over a few millidpa. Among the three mechanisms, only slip can keep deforming the crystal indefinitely under continued irradiation, while loop tilting and plane formation eventually cease as the microstructure becomes saturated with vacancies, and no further interstitials are created21.

The above relaxation mechanisms conserve volume, keeping the amount of swelling unchanged under application of external stress, see Fig. 5c. Examining the atomistic simulations, we find that mono-vacancies represent over 90% of the vacancy content, while interstitials coalesce into very large clusters. Therefore, the amount of swelling can be estimated using \({{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\rm{vol}}}}^{* }={{\rm{tr}}}({{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}^{* })\approx {c}_{{{\rm{vac}}}}\left(1+{\Omega }_{{{\rm{vac}}}}\right)\), where cvac represents the mono-vacancy number concentration, including those constituting vacancy clusters, and Ωvac = −0.36 is the relaxation volume of a tungsten mono-vacancy33 in atomic volumes, close to the ab initio value34 of Ωvac = −0.345. The simulated microstructures saturate to a vacancy concentration of cvac = (0.30 ± 0.01)% with a volume swelling of \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{vol}}}}^{* }\) = (0.20 ± 0.01)% (with uncertainty indicating standard deviation), which is in close agreement with the swelling estimate of 0.19% based on the vacancy concentration alone.

As was already hypothesised by Grossbeck and Mansur9, the mechanisms responsible for the anomalous, low-temperature irradiation creep are distinctly different from the conventional irradiation creep mechanisms occurring at high temperature. Here, stress relaxation occurs entirely in the absence of thermal diffusion of defects. We observe that dislocation loops preferentially align themselves with respect to the external stress direction at low dose, see Fig. 5a at 0.04 dpa. This observation agrees with a recent study reaching a similar dose27, supporting the stress-induced preferential nucleation hypothesis. However, at higher doses, the dislocation microstructure evolves into a system-spanning network35, enabling the plastic deformation of the entire crystal28. This is correlated with the sudden increase in eigenstrain over this dose range, as seen in Fig. 3b, and a simultaneous decrease in the dislocation line density. This process is driven by the elastic interaction between dislocation loops, ultimately leading to their coalescence into an interconnected network. A microstructure with cvac = 0.3% and preferentially tilted loops can at most attain \({\varepsilon }_{\parallel }^{* }=2.6\times 1{0}^{-3}\), which is already exceeded at \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}=0.5\,{{\rm{GPa}}}\), see Fig. 3b, illustrating that the crystal has undergone plastic deformation, and not just a polarisation of the dislocation microstructure.

The simulated eigenstrain saturates to a value of 1%, which quantitatively is comparable to low-temperature irradiation creep measurements in a broad variety of dissimilar materials, such as austenitic and ferritic/martensitic steels9, molybdenum11, and tungsten12, where higher temperatures were found to yield lower creep rates. Notably, we observed a significant amount of relaxation to occur within 0.3 dpa of exposure, which matches the low-temperature in situ irradiation creep experiments conducted in tungsten12. We conclude that in a high-fluence reactor environment, stresses are expected to relax extremely quickly. Considering the operating conditions in a fusion power plant1, it would take about a week of full-time operation to reach this dose in critically important components such as the first wall, divertor, or cooling pipes. While structural materials close to the plasma may be kept sufficiently hot to stimulate recombination of radiation defects, the actively cooled materials, in which stress concentrations critical to structural integrity are expected to develop, would relax through the favourable low-temperature creep mechanism explored in this study.

The development and integration of an accurate, predictive model for materials into a virtual full-scale fusion reactor remains one of the central challenges in fusion materials modelling. The multiscale model developed here is a necessary step towards the development and integration of a predictive parameter-free description of materials into a digital representation of a whole fusion reactor5,36. Here, by self-consistently embedding a predictive materials model into a finite element framework, we are able to explicitly account for irradiation exposure that is spatially heterogeneous over the length-scale of the sample, similarly to how the neutron flux in a fusion reactor would attenuate over the extent of a reactor component. The multiscale wire model developed here is a digital shadow of the wire experiment, which enables testing experimental outcomes a priori with respect to variations in experimental parameters, such as the sample geometry or the irradiation characteristics.

Methods

Irradiation creep experiment

The irradiation creep experiments were carried out using the General-Purpose Irradiated Fiber and Foil Experiment (GIRAFFE) at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics in Garching. GIRAFFE is a specialised device designed and built for the study of synergistic effects in materials science, consisting of a tensile testing machine that can be integrated into one of the beamlines of a 3 MV tandem accelerator.

The samples were fabricated out of potassium-doped, cold drawn tungsten wire with a diameter of 16 μm, which was manufactured by OSRAM GmbH in Germany. To prepare the samples, an approximately 8 cm long piece of wire was affixed to a polypropylene frame using UHU PLUS ENDFEST 300 epoxy resin, which significantly improved the handling and mounting of the sample. Defined electrical contacts were established at both ends using adhesive copper tape, leaving a central usable length of the sample measuring 15 mm.

After the sample was mounted in the fixture of the tensile testing machine, it was loaded with 50 mN, and an x-y stage was translated between the sample fixture and the load cell in both axes until a minimum force was reached. This procedure ensured a uniaxial tensile load on the wire during the test. To measure the ion current, the lower sample holder was connected to a Keithley 6487 picoamperemeter. In addition, a tungsten beam-limiting aperture with a vertical opening of 4 mm was installed, along with suppression electrodes maintained at a voltage of −500 V to minimise the effect of secondary electron emission from the sample and aperture. An additional 102 μm thin tungsten wire was attached to the lower sample holder, which has no contact with the upper sample holder to avoid influencing the mechanical measurement. This wire performs two functions. During the experiment, it was positioned in the beam path behind the sample, thus increasing the measured ion current by a factor of 102/16 due to its larger diameter, resulting in a significantly improved signal-to-noise ratio. The ion fluence Φ was then calculated from the measured ion current I, the ion charge state (Z = 6), the diameter of the thick wire (d = 102 μm), the aperture height (lirr = 4 mm), and the elementary charge e using equation

The second function of the thick wire was to protect the sample during accelerator start-up and adjustment. For this purpose, the sample holders were rotated by 180° so that the sample lied in the beam shadow cast by the thick wire, preventing the sample from being irradiated before the start of the experiment.

Previous to the actual main experiment, a preliminary experiment was performed to quantify the relaxation of the entire test setup in the absence of irradiation. In this test, the sample is mechanically tensioned to 110% of the initial value of the main experiment, and the force drop measured over a duration of about 2 h. During the first 30 min, an exponential drop of the force was observed, followed by a linear decay. This was likely due to settling effects in the adhesive bonding of the sample. For this reason, we delayed the start of the main experiment by 30 min after application of the mechanical load.

For the main experiment, the sample was again mechanically tensioned to the initial value. After the aforementioned 30 min delay, the irradiation with the high-energy heavy ion beam was started, with the positions of the sample ends held fixed. Since almost all of the energy of the impacting ions was deposited in the sample, it heats up by less than 100 °C (see Supplemental Material for details on this estimate), resulting in thermal expansion and an immediate drop in the tensile force. To compensate for this, the irradiation was carried out in intervals, and the force drop was only measured during brief irradiation pauses after a short cooling phase. At the start of the experiment, the interval duration was 5 min to provide higher time resolution, with the interval length gradually increased up to 30 min during the experiment. The experiments were performed multiple times for each initial stress value, testing 0.5 GPa (3 times), 1.0 GPa (4 times), 1.5 GPa (3 times), or 2.0 GPa (3 times).

The 20.3 MeV W6+ ion beam used to generate the damage in the sample had a beam spot with a diameter of about 1.5 mm and a Gaussian intensity distribution. To ensure uniform irradiation along the sample axis, the ion beam was scanned vertically at a frequency of 1 kHz and limited to a height of 4 mm using the tungsten aperture. As the ion beam diameter was much larger than the sample wire diameter, the intensity was assumed to be constant across the sample. To achieve high time resolution at the beginning of the experiment, the irradiation was started with an initial net ion current of approximately 0.15 nA (as measured by both wires) and then gradually increased up to 0.9 nA over the course of the experiment to reach the desired final dose. This resulted in an ion flux in the range of 2.5 × 1011 cm−2s−1.

The measured force values Fi needed to be corrected for two sources of error:

The first source was a long-term drift of the zero point in the load cell. A preparatory experiment showed that the zero point of the load cell shifted by less than 1 mN during the typical 6 hour duration of the experiment. To quantify this effect, the sample was completely unloaded at the end of the main experiment at time tE, allowing the determination of the zero drift FE. Assuming linear drift, the correction term \({F}_{i}^{{{\rm{(1)}}}}\) at time ti was then estimated using equation

The second correction pertained to the relaxation of the entire measurement setup, particularly the epoxy resin embedding of the sample ends. To address this, the force-over-time curve obtained from the preliminary experiment was divided into intervals of 1000 data points, and the slope of each interval was determined. The individual slopes were then divided by the average force in the interval, and the overall slope average (α) was calculated. The measured values were then corrected using equation

More information on the dose profile calculation and the MD setup is found in the Supplementary Methods.

Molecular dynamics

Simulations were run using the LAMMPS37 software, employing an embedded atom model potential for tungsten33. This potential was chosen because it accurately predicts the defect content of highly irradiated material, in agreement with experiments21,38. All simulations were initialised as pristine single-crystal tungsten consisting of 100 × 100 × 250 body-centered crystal unit cells (32 × 32 × 80 nm3), with periodic boundary conditions applied to all three directions in order to describe a materials volume element representative of a grain in a wire. Uniaxial stress was applied along the z-direction by minimising the potential energy of the system with respect to atom positions and box dimensions using the method of conjugate gradients, under the constraint that all but the σzz component of the internal stress tensor reach near zero. To introduce irradiation damage, rather than simulating the entire track of incident high-energy tungsten ions that extend several microns into the material, we leveraged the known property of collision sequences in which damage-generating scattering events are relatively rare and can be considered as independent and uncorrelated. We used the SRIM software18, which is based on the binary collision approximation method, to generate a set of primary recoil energies representative of those produced by 20.3 MeV W6+ ions impacting solid bulk tungsten. The effect of irradiation was then introduced by the following iterative procedure: First, recoil energies are randomly drawn from the representative set of recoil energies until a target dose increment of \({\sum }_{i}{N}_{{{\rm{d}}}}({T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{(i)})/N\) > 0.0002 dpa is reached, where N is the number of atoms in the cell and Nd(Td) is an estimate for the number of atoms displaced by a recoil with damage energy Td in the NRT model17; a convention commonly used in the nuclear materials community. The damage energy \({T}_{{{\rm{d}}}}^{(i)}\) is computed from the recoil energy \({E}_{{\rm{R}}}^{(i)}\) using Lindhard’s formula17 to account for losses due to electronic stopping. For each drawn recoil energy, a random atom in the system is selected and assigned the corresponding kinetic energy with randomly-oriented velocity. We avoided selecting atoms too close to one another to prevent any spurious effects caused by overlapping regions where damage production occurs. Next, the simulation is propagated in the NVE ensemble for a duration of 10 ps, which was sufficient for the cascade dynamics to conclude. We including damping terms describing energy loss due to electronic excitations; for more details on this, we refer to ref. 21. After the propagation, the atom velocities are set to zero, and the system is relaxed to a local energy minimum while maintaining the uniaxial stress constraint. This procedure is repeated, with every iteration incrementing the dose by approximately 0.0002 dpa, until a target dose of 0.5 dpa is reached. After each relaxation step, the simulation cell dimensions were recorded in a file, from which we computed the eigenstrain as a function of dose for the specified target stress using the formula \({{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}^{* }(\phi ;{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}})={{{\bf{A}}}}_{i}\cdot {{{\bf{A}}}}_{0}^{-1}-{\mathbb{I}}\), where Ai is a matrix with columns represented by the simulation cell vectors at dose ϕi. More information on the sample, the sample preparation process, and the experimental setup is found in the Supplementary Methods. The atomistic structures were analysed with the Wigner-Seitz and DXA methods as implemented in the Ovito software39.

Virtual wire model

The full boundary value problem is given by

We solve for the displacement field u(r) within the region \(\Omega \subset {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) representing the elastic body, subject to traction and displacement conditions applied to the surfaces ∂Ωt and ∂Ωu, respectively, with ∂Ωt ∪ ∂Ωu = ∂Ω. Vector field n(r) represents the outward-facing normal vector of surface ∂Ω.

The boundary value problem was solved using the finite element method (FEM) with the FEniCS40 solver. In practice, we exploit that the wire diameter (d = 16 μm) is significantly smaller than both the initial wire length (l = 15 mm) and the length of the irradiated wire section (lirr = 4 mm), and therefore only solve for the fields within a two-dimensional x-y slice of the irradiated wire section, considering it as representative of the entire irradiated region. In the simulations, we described the uniaxial tensile loads applied in experiment as an external homogeneous stress σext, in which only the \({\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\) component was non-zero. The wire boundaries were subject to traction free conditions. Before simulating the stress relaxation, we required a spatial map of the dose-rate \(\dot{\phi }(x,y)\) within the wire slice, originating from the ion beam irradiation, as the wire is only irradiated from one side and the beam does not penetrate beyond a surface layer of about 2 μm thickness. We used SRIM18 to generate the dose-rate profile \(\dot{\phi }(x,y)\) shown in Fig. 1, with more comprehensive details given in the Supplementary Methods. Beginning with step n = 0, the initial dose and eigenstrain were set to zero: ϕn(x, y) = 0 and \({{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{n}^{* }(x,y)=0\). Additionally, the initial external stress was set at \({{{\mathbf{\sigma }}}}_{0}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}(x,y)={{{\mathbf{\sigma }}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}\). The stress relaxation was propagated using the following explicit method: First, the FEM problem is solved for the total stress σn(x, y), from which we obtain the elastic stress in the irradiated region by subtracting the eigenstrain contribution5, \({{{\mathbf{\sigma }}}}_{n}^{{{\rm{el}}}}(x,y)={{{\mathbf{\sigma }}}}_{n}(x,y)-{{\bf{C}}}:{{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{n}^{* }(x,y)\). Next, the dose profile is updated to the next time step, \({\phi }_{n+1}(x,y)={\phi }_{n}(x,y)+\dot{\phi }(x,y)\Delta t\), and the eigenstrain is incremented using the previous elastic stress state, under assumption that dimensional changes are accrued irreversibly:

The new eigenstrain is used to update body forces and surface tractions for the next iteration of the FEM solver. Relaxation of the uniaxial stress arises from the length change of the irradiated section, which follows entirely from the eigenstrain5 through \(\langle {\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{el}}}}\rangle ={\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}}-E\langle {\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{zz}}},n}^{* }\rangle {l}_{{{\rm{irr}}}}/l\), where E is the Young’s modulus of tungsten and \(\langle {\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{zz}}},n}^{* }\rangle\) is the component of the eigenstrain along the wire length at step n, averaged over the wire cross-section. This procedure is repeated until the simulation advances to the desired exposure time. After every iteration, the profiles of dose, eigenstrain, and elastic stress are exported.

Uncertainty quantification

The stochastic variation of the atomistic eigenstrain data-sets gives rise to uncertainty on the surrogate model parameters \(\hat{{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}\), which propagates up the scale as uncertainties on the predictions from the virtual wire model. Using the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, we obtain 105 random samples of the parameter vector θ. The Markov chain is started with an initial value of \({{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{0}=\hat{{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}\), and moves are proposed according to the protocol \({{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{n+1}={{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{n}+x\cdot {{\boldsymbol{{{\mathcal{N}}}}}}(0,{{\bf{v}}})\), where v is a vector with components \({v}_{i}={\hat{s}}_{i}^{2}\) and x is a step-size between 0.02 and 0.03, chosen to maintain an acceptance ratio between 10% and 20%. A move is accepted if \(r\le {{\mathcal{L}}}({{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{n+1}| {{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}^{* })/{{\mathcal{L}}}({{{\boldsymbol{\theta }}}}_{n}| {{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}^{* })\), where r ∈ [0, 1] is a uniform random number. The initial 104 samples are discarded to allow for burn-in. This process is repeated for every eigenstrain data-set for each common external stress, resulting in 105 realisations of surrogate model parameter vectors θ per stress for both parallel and perpendicular eigenstrains. Finally, every virtual wire simulation is independently executed 5 × 103 times, each time using a surrogate model \({{{\mathbf{\varepsilon }}}}_{{{\rm{MD}}}}^{* }(\phi ,{\sigma }_{{{\rm{zz}}}}^{{{\rm{ext}}}})\) with parameter vectors randomly drawn from their respective Markov chains. From this, a distribution of stress relaxation curves is obtained, allowing construction of the confidence intervals shown in Figs. 1 and 4.

Data availability

The eigenstrain curves and snapshots from the MD simulations, as well as parameters of the eigenstrain surrogate model are available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.13383236.

Code availability

The open-source computer code LAMMPS used for MD simulations is available at https://lammps.sandia.gov. The LAMMPS script used to perform the high-dose MD simulations is available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.13383236. The open-source Python package FEniCS used for multiscale simulations is available at https://fenicsproject.org/.

References

Knaster, J., Moeslang, A. & Muroga, T. Materials research for fusion. Nat. Phys. 12, 424–434 (2016).

Coenen, J. et al. Materials for DEMO and reactor applications—boundary conditions and new concepts. Phys. Scr. 2016, 014002 (2015).

Reali, L., Gilbert, M. R., Boleininger, M. & Dudarev, S. L. Intense γ-photon and high-energy electron production by neutron irradiation: Effects of nuclear excitations on reactor materials. PRX Energy 2, 023008 (2023).

Wu, Y. et al. Identification of safety gaps for fusion demonstration reactors. Nat. Energy 1, 1–11 (2016).

Reali, L., Boleininger, M., Gilbert, M. R. & Dudarev, S. L. Macroscopic elastic stress and strain produced by irradiation. Nucl. Fusion 62, 016002 (2022).

Griffiths, M. Strain Localisation and Fracture of Nuclear Reactor Core Materials. J. Nucl. Eng. 4, 338–374 (2023).

Gilbert, E. & Bates, J. Dependence of irradiation creep on temperature and atom displacements in 20% cold worked type 316 stainless steel. In Measurement of Irradiation-enhanced Creep in Nuclear Materials, 204–209 (Elsevier, 1977).

Was, G. S. Irradiation creep and growth. In Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science: Metals and Alloys. 2nd Ed. 735–791 (Springer New York, NY, 2017).

Grossbeck, M. & Mansur, L. Low-temperature irradiation creep of fusion reactor structural materials. J. Nucl. Mater. 179, 130–134 (1991).

Griffiths, M. Ni-based alloys for reactor internals and steam generator applications. In Structural alloys for nuclear energy applications, 349–409 (Elsevier, 2019).

Pouchou, J.-L. Low temperature irradiation creep of tungsten and molybdenum. Tech. Rep., CEA Centre d’Etudes Nucleaires de Fontenay-aux-Roses (1975).

Ponsoye, J. Irradiation de tungstene sous contrainte uniaxiale a basse temperature. Radiat. Eff. 8, 13–26 (1971).

Riesch, J. et al. Tensile behaviour of drawn tungsten wire used in tungsten fibre-reinforced tungsten composites. Phys. Scr. 2017, 014032 (2017).

Fuhr, M. et al. Rate-controlling deformation mechanisms in drawn tungsten wires. Philos. Mag. 103, 1029–1047 (2023).

Kärcher, A. et al. Deuterium retention in tungsten fiber-reinforced tungsten composites. Nucl. Mater. Energy 27, 100972 (2021).

Riesch, J. et al. Irradiation effects in tungsten–from surface effects to bulk mechanical properties. Nucl. Mater. Energy 30, 101093 (2022).

Norgett, M. J., Robinson, M. T. & Torrens, I. M. A proposed method of calculating displacement dose rates. Nucl. Eng. Des. 33, 50–54 (1975).

Ziegler, J. F. SRIM-2003. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interact. Mater. At. 219, 1027–1036 (2004).

Mason, D. R. et al. Relaxation volumes of microscopic and mesoscopic irradiation-induced defects in tungsten. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 075112 (2019).

Hirst, C. A. et al. Revealing hidden defects through stored energy measurements of radiation damage. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn2733 (2022).

Boleininger, M., Mason, D. R., Sand, A. E. & Dudarev, S. L. Microstructure of a heavily irradiated metal exposed to a spectrum of atomic recoils. Sci. Rep. 13, 1684 (2023).

Zepeda-Ruiz, L. A. et al. Atomistic insights into metal hardening. Nat. Mater. 20, 315–320 (2021).

Derlet, P. M. & Dudarev, S. L. Microscopic structure of a heavily irradiated material. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 023605 (2020).

Sand, A. E., Dudarev, S. L. & Nordlund, K. High-energy collision cascades in tungsten: Dislocation loops structure and clustering scaling laws. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 103, 46003 (2013).

Rizzardi, Q. et al. Mild-to-wild plastic transition is governed by athermal screw dislocation slip in bcc Nb. Nat. Commun. 13, 1010 (2022).

Proville, L. & Choudhury, A. Unravelling the jerky glide of dislocations in body-centred cubic crystals. Nat. Mater. 23, 47–51 (2024).

Da Fonseca, D. et al. Evidence of dislocation loop preferential nucleation in irradiated aluminum under stress. Scr. Materialia 233, 115510 (2023).

Boleininger, M., Dudarev, S. L., Mason, D. R. & Martínez, E. Volume of a dislocation network. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 063601 (2022).

Anderson, P. M., Hirth, J. P. & Lothe, J.Theory of Dislocations (Cambridge University Press, 2017), 3 edn.

Wolfer, W., Okita, T. & Barnett, D. Motion and rotation of small glissile dislocation loops in stress fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 085507 (2004).

Mason, D. R. et al. Observation of transient and asymptotic driven structural states of tungsten exposed to radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 225503 (2020).

Li, Y., Boleininger, M., Robertson, C., Dupuy, L. & Dudarev, S. L. Diffusion and interaction of prismatic dislocation loops simulated by stochastic discrete dislocation dynamics. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 073805 (2019).

Mason, D. R., Nguyen-Manh, D. & Becquart, C. S. An empirical potential for simulating vacancy clusters in tungsten. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 505501 (2017).

Ma, P.-W. & Dudarev, S. L. Effect of stress on vacancy formation and migration in body-centered-cubic metals. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 063601 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Dynamic equilibrium of displacement damage defects in heavy-ion irradiated tungsten. Acta Materialia 244, 118578 (2023).

Reali, L. & Dudarev, S. L. Finite element models for radiation effects in nuclear fusion applications. Nucl. Fusion 64, 056001 (2024).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Mason, D. R. et al. Parameter-free quantitative simulation of high-dose microstructure and hydrogen retention in ion-irradiated tungsten. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 095403 (2021).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2009).

Alnaes, M. S. et al. The FEniCS project version 1.5. Arch. Numerical Softw. 3, https://doi.org/10.11588/ans.2015.100.20553 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Robert Lürbke for taking the photograph shown in Fig. 1a. This work has been carried out within the framework of the EUROfusion Consortium, funded by the European Union via the Euratom Research and Training Programme (Grant Agreement No. 101052200 - EUROfusion), and by the RCUK Energy Programme, Grant No. EP/W006839/1. To obtain further information on the data and models underlying the paper please contact PublicationsManager@ukaea.uk. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. This work was performed using resources provided by the Cambridge Service for Data Driven Discovery (CSD3) operated by the University of Cambridge Research Computing Service (www.csd3.cam.ac.uk), provided by Dell EMC and Intel using Tier-2 funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (capital grant EP/T022159/1), and DiRAC funding from the Science and Technology Facilities Council (www.dirac.ac.uk).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F. and M.B. contributed equally to the formulation of the scientific problem and conceptualisation of experimental and computational studies. A.F. designed and conducted the experiments and analysed the stress relaxation data. M.B. developed the multiscale simulation framework and conducted the simulations. S.L.D. and J.R. jointly supervised the work. D.R.M. and L.R. contributed to the development of the multiscale simulation framework. T.H., M.F., T.S.S., and R.N. contributed to the development of the experiment. All authors contributed to the data discussion and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thanks Weizhong Han and Shijun Zhao for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Xiaoyan Li & John Plummer. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feichtmayer, A., Boleininger, M., Riesch, J. et al. Fast low-temperature irradiation creep driven by athermal defect dynamics. Commun Mater 5, 218 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00655-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00655-5