Abstract

The charge-density wave (CDW) mechanism and resulting structure of the AV3Sb5 family of kagome metals has posed a puzzling challenge since their discovery four years ago. In fact, the lack of consensus on the origin and structure of the CDW hinders the understanding of the emerging phenomena. Here, by employing a non-perturbative treatment of anharmonicity from first-principles calculations, we reveal that the charge-density transition in CsV3Sb5 is driven by the large electron-phonon coupling of the material and that the melting of the CDW state is attributed to ionic entropy and lattice anharmonicity. The calculated transition temperature is in very good agreement with experiments, implying that soft mode physics are at the core of the charge-density wave transition. Contrary to the standard assumption associated with a pure kagome lattice, the CDW is essentially three-dimensional as it is triggered by an unstable phonon at the L point. The absence of involvement of phonons at the M point enables us to constrain the resulting symmetries to six possible space groups. The unusually large electron-phonon linewidth of the soft mode explains why inelastic scattering experiments did not observe any softened phonon. We foresee that large anharmonic effects are ubiquitous and could be fundamental to understand the observed phenomena also in other kagome families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The kagome lattice, composed of three triangular lattices rotated 120 degrees with respect to each other, stands as one of the most thoroughly investigated hexagonal lattices, offering a wealth of intriguing electronic properties linked to its distinct geometry1. Its multi-lattice nature allows for the emergence of flat bands2,3,4,5, which, in turn, lead to high electronic correlation effects provided they fall into the vicinity of the Fermi energy6,7,8,9, while its triangular arrangement provides a natural platform for magnetically frustrated systems3,10. The presence of Dirac cones in the band structure leads also to non-trivial topological effects6,11. Consequently, the recently discovered family of kagome materials, AV3Sb5 with A = Cs, K, Rb12, has garnered significant attention, as it provides a platform for exploring the interplay between electronic correlations, frustrated geometry, charge-density waves (CDWs), topology, and even superconductivity.

All compounds within the AV3Sb5 family exhibit a CDW at a temperature of ~90 K12. The CDW holds a crucial significance because below TCDW a plethora of novel and intriguing physical phenomena have been reported. These include switchable chiral transport13,14, specular optical rotation15, or the presence of a chiral flux phase16,17,18 accompanied by loop currents. This unconventional nature is also manifested in the superconducting order observed below 2.5 K for CsV3Sb519, with reports, for instance, of unconventional superconductivity20,21,22,23, multi-charge flux quantization24, and chiral superconductivity25.

The true nature of the CDW and the resulting atomic structure remain open questions. Moreover, it is not clear what the intricate relation between the CDW order and all observed unconventional phenomena is. In fact, the absence of consensus regarding the CDW structure hinders the understanding of the emerging properties, mainly because they might be constrained by symmetry. Just below TCDW ~ 94 K, the prevailing experimental evidence supports a three-dimensional 2 × 2 × 2 structure for the CDW26,27,28,29, but without a consensus on whether the CDW breaks six-fold symmetry8,26,30,31,32. Some works report a second CDW around \({T}_{CD{W}_{2}} \sim 60\,{{{{\rm{K}}}}}\)8,16,26,27,31,33,34, in which a 2 × 2 × 4 CDW35,36, a mixture of 2 × 2 × 2 with 2 × 2 × 4 orders37, or a transition between both types of ordering34 have been reported. The emergence of the second CDW seems to coincide with the onset of unconventional phenomena, including the chiral flux phase16, activated chiral transport13, and the disruption of C6 symmetry8,31. It is important to note that there are also reports which do not observe this second CDW28. In fact, it is not clear whether this exotic phenomenon is intrinsic to the material or whether it is imposed by external perturbations9. Doubts also persist on the conservation of time-reversal symmetry, with contradictory results from muon spin spectroscopy16,38,39 and magneto-optical Kerr effect15,30,40.

The origin and character of the CDW also remain a subject of debate. At first glance, the nesting mechanism20,27,41,42,43,44,45,46 appears natural, aligning perfectly with the fermiology of the pure kagome lattice and resulting in the widely experimentally confirmed 2 × 2 modulation within the plane8,16,26,27,28,29,31,47. This nesting paradigm has also been employed to account for the reported unconventional character of the CDW42,43,48,49. On the other hand, there are also multiple reports suggesting an electron-phonon-driven mechanism28,47,50. With regard to the CDW character, reports concur on the absence of observed softening in the phonon spectrum in Raman26,28 and inelastic x-ray scattering29 experiments, suggesting a first-order transition to the CDW. Even though a discontinuity observed in the lattice parameters at TCDW supports this picture51, the discontinuity is so minute that a soft phonon mode-driven CDW should not be excluded, which would be consistent with the general mechanism in other CDW materials like transition-metal dichalcogenides52,53,54. Theoretical calculations performed thus far do not clarify these issues as they are mostly limited to phenomenological models41,43,44,45,46,55 or to ab initio calculations within the standard harmonic approximation for the phonons20,26,56, which is known to break down in CDW systems53,54,57,58. A recent investigation into the temperature dependence of the phonon spectra does suggest the presence of soft mode physics59 but lacks the resolution of the specific soft mode triggering the CDW or an in-depth spectral analysis.

In this work, making use of first-principles density-functional theory (DFT) calculations including a non-perturbative treatment for lattice anharmonicity, we show that the CDW instability in CsV3Sb5 is triggered by the softening with decreasing temperature of a phonon mode at the L point. The softening is a consequence of its extraordinarily large electron-phonon coupling, discarding pure electronic nesting as the main destabilizing force. Our calculated TCDW is in very good agreement with experiments, demonstrating that the CDW melts due to lattice entropy and that soft mode physics plays a dominant role in the CDW transition. This is consistent with a second-order phase transition as well as with a weak first-order character. We explain that the phonon softening is not observed experimentally29 due to its huge broadening, a consequence of the large electron-phonon and anharmonic interactions of the soft mode.

Results and discussion

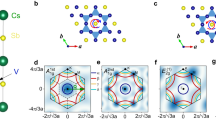

The melting of the CDW phase

The DFT harmonic spectrum of the CsV3Sb5 high-symmetry phase exhibits a significant number of lattice instabilities (Fig. 1a), in agreement with previous works20,56. Two primary instabilities can be observed near the M and L points, coinciding with the nesting vectors of the Van Hove Fermi pockets (Fig. 1d). The most prominent instability occurs at a specific point along the AL line, which we will refer to as the AL mode. However, the instabilities in the phonon spectra of CsV3Sb5 are highly sensitive to the electronic temperature used in the DFT calculations to perform integrals over the Brillouin zone41. Considering that when increasing the electronic temperature in the calculations the L mode stabilizes after the AL one (see Supplementary Material), the main instabilities of the system seem to be the soft modes transforming under \({L}_{2}^{-}\) and \({M}_{1}^{+}\) irreducible representations in line with previous findings20,50,56. Considering that each of these points contributes with three equivalent vectors within the star, we expect the CDW to be described by a six-dimensional order parameter \({{{{\bf{Q}}}}}=\left({M}_{1},{M}_{2},{M}_{3},{L}_{1},{L}_{2},{L}_{3}\right)\).

a Calculated harmonic phonon dispersion of CsV3Sb5 in the P6/mmm phase. The harmonic spectrum exhibits two main instabilities at the M and L high-symmetry points. b Unit cell for CsV3Sb5. The vanadium atoms (pink) form a perfect kagome lattice. c Fermi surface within the first Brillouin zone with labeled high-symmetry points. d While most of the Fermi surface exhibits low dispersion in the z direction, there are closed Fermi surface pockets containing Van Hove singularities situated near the M and L points, indicating the three-dimensional nature of CsV3Sb5.

The high sensitivity of both the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) and \({M}_{1}^{+}\) modes to the electronic temperature has been used to argue in support of an electron-driven CDW via a nesting mechanism41. This concept hinges on the idea that the Van Hove singularities at M and L (Fig. 1d) are coupled by the previously described six-dimensional order parameter Q. As temperature increases, it leads to a reduction in the occupied states associated with these Van Hove singularities, subsequently diminishing the instability. To test the hypothesis of electronic entropy as a stabilizing factor for the high-symmetry phase, we compute in the harmonic approximation the frequency of the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) and \({M}_{1}^{+}\) modes as a function of the real electronic temperature described by Fermi-Dirac statistics. As shown in Fig. 2d, while the modes do eventually stabilize, the predicted transition temperature of ~760 K for the CDW is far from the experimental observations. This, in conjunction with the highly anharmonic Born-Oppenheimer energy landscape illustrated in Fig. 2c, suggests that it is not the electronic entropy, but the ionic entropy, what is responsible for the melting of the CDW as it is the case in transition-metal dichalcogenides54.

a Calculated anharmonic phonon spectrum for the P6/mmm phase at different temperatures above and below TCDW ~ 94 K. The high-symmetry points labeled in red are explicitly computed, while the rest of the spectrum is interpolated. At 80K the system is entirely stabilized by anharmonic effects, considering that the remaining imaginary frequencies are artifacts of the Fourier interpolation. b Zoomed view of the LM path, showcasing the softening of the L mode. Meanwhile, the M phonon remains fully stabilized across the entire temperature range due to anharmonic effects. c Computed Born-Oppenheimer energies as the structure distorts according to the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) phonon responsible for the CDW. d Effects of electronic and ionic entropy on the stability of the CsV3Sb5 high-symmetry phase. The black line shows the squared frequency of the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) and \({M}_{1}^{+}\) modes with respect to electronic temperature, suggesting that the high-symmetry structure is expected to stabilize at around ~ 815 K. Conversely, the red line considers only the ionic entropy for the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) mode. Our calculations predict that ionic entropy stabilizes the system at ~ 77 K, in agreement with the TCDW ~ 94 K experimental value.

To explore this idea, we compute the static phonon spectra as a function of temperature in the high-symmetry phase of CsV3Sb5, taking into account anharmonic effects within the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation (SSCHA)60,61,62,63. As seen in Fig. 2a, the anharmonic corrections strongly renormalize the phonon spectrum to the point where it is fully stabilized above TCDW ~ 80 K, which is in very good agreement with the experimental value of 94 K. This good agreement demonstrates that it is ionic entropy, which is largely affected by anharmonicity, what melts the CDW and that electronic entropy does not play any role. Interestingly, the \({M}_{1}^{+}\) soft mode is no longer almost degenerate with the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) phonon, as it remains stable even at 50 K. This is in agreement with thermal diffuse scattering experiments that do not see any signal at M, only at L29. CsV3Sb5 deviates thus from the ideal two-dimensional kagome instability picture and indicates that the coupling between kagome layers is strong enough to break the degeneracy between the phonons at M and L. This result is in line with quantum oscillation and magnetotransport experiments underscoring the significance of interlayer coupling64. Consequently, a three-dimensional CDW with modulation along the c-axis emerges. This greatly simplifies the analysis of the CDW from a six-dimensional to a three-dimensional order parameter that now is solely related to the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) instabilities. The clear softening observed at the L point in this static calculation shows that soft phonon physics is triggering the CDW transition and that it has to be of second-order or weak first-order character.

One important conclusion from our results is that the CDW mechanism is independent of the novel physics that emerges below TCDW. In other words, the exotic physics observed is not necessary to explain the CDW. The study of the low-temperature physics of CsV3Sb5 becomes, then, more feasible. Instead of dealing with the CDW and the new phenomena in one single problem, one may first solve the CDW structure and then take advantage of the correct symmetries in the next step. Our results suggest as well that anharmonicity cannot be neglected in any model or calculation trying to describe the free energies of the candidate low-symmetry phases, especially given that the Born-Oppenheimer energies of the competing phases are only few meV per formula unit apart26.

The formation of the CDW phase

Despite addressing anharmonicity as the primary factor in the CDW melting process, the mechanism responsible for the formation of the CDW in CsV3Sb5 remains unclear. In order to unveil this issue, we compute both the nesting function and the phonon linewidth given by the electron-phonon interaction along the AL high-symmetry line, which exhibits the most unstable phonons. These two quantities are very similar, with the difference that the latter includes the electron-phonon matrix elements but not the former as discussed in the Supplementary Material. In Fig. 3a we compare these two quantities for two modes: the mode responsible for driving the instability (labeled as α) and the next most unstable mode (labeled as β). The nesting function displays a prominent peak at the A point, reflecting the highly two-dimensional Fermi surface of CsV3Sb5 (Fig. 1b), along with a smaller peak around \(\frac{3}{4}\,AL\), corresponding to the nesting vector between the Van Hove pockets at kz = 0 and the ones at kz = 0.5 (Fig. 1d). Conversely, the electron-phonon linewidth exhibits a significant increase from nearly zero at the A point to a huge value of ~2 meV at the L point for the α mode, while remaining relatively constant for the β mode. Table S1 in the Supplementary Material provides an explicit comparison of the electron-phonon linewidths for all modes at the M and L points, highlighting the significant linewidths of the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) and \({M}_{1}^{+}\) modes compared to the others. These findings further support the idea that the CDW is primarily mediated by the electron-phonon coupling rather than a nesting mechanism, underscoring once again the critical role of lattice effects in this system.

All dotted points in the three plots correspond to explicit calculations. a Harmonic phonon frequencies along the AL high-symmetry line for both the α phonon branch (which contains the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) instability) and the subsequent most unstable branch, β. b The nesting function along the AL high-symmetry line exhibits a peak at A rather than at L, which contradicts expectations for a nesting-driven mechanism. This emphasis on the A point aligns with the highly two-dimensional Fermi surface (Fig. 1c). c The electron-phonon linewidth of the α and β branches along the AL line shows a large peak at the L point for the α mode.

The anharmonic spectral function

Our results indicate either a second-order or a weak first-order character for the phase transition, with the continuous nature imprinted in the softening of the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) phonon (Fig. 2b). However, multiple instances in the literature point to a first-order nature of the CDW26,37, and neither inelastic x-ray scattering29 or Raman spectroscopy experiments28,33 have observed such softening. To understand this apparent contradiction, we compute the spectral function for both the M and L phonons fully accounting for anharmonic effects. The spectral function, as shown in Fig. 4a, b, not only confirms the absence of phonon collapse at the M point but also underscores the profoundly anharmonic nature of the \({L}_{2}^{-}\) phonon that drives the instability. As depicted in Fig. 4b, the unstable \({L}_{2}^{-}\) mode becomes broader and splits into a double peak as the temperature approaches TCDW. Thus, we expect this mode to be exceedingly challenging to observe experimentally. This difficulty arises not only from its double peak and broadened nature but also because the spectral function is typically fitted using a set of Lorentzians representing different modes experimentally. To study the cumulative effects of both anharmonic and electron-phonon linewidths, we first need well-defined quasiparticles to which we can later add the electron-phonon linewidth. To achieve this, we compute the spectral function using a no-mixing approximation by excluding the off-diagonal elements of the anharmonic phonon self-energy. This allows for the independent tracking of different modes, as indicated by different colors in Fig. 4c, d. Nonetheless, for illustrative purposes, the full anharmonic spectral functions are overlaid to demonstrate the impact of this approximation. This approximation works effectively for the M point, except for the softest mode at 50 K, and reveals the softening of a highly anharmonic mode (colored in blue) that corresponds to \({M}_{1}^{+}\). In the case of L, off-diagonal terms exert a more significant influence overall, as evidenced by the stronger differences between panels (b) and (d). For instance, the softening in panel (d) appears at a lower temperature. Still, we are able to capture the softening of a highly anharmonic mode (colored in blue), which develops a double dome and corresponds to \({L}_{2}^{-}\). In Fig. 4e, f we fit a Lorentzian function to each of the individual modes and add the corresponding electron-phonon linewidth in order to obtain a spectral function that captures both anharmonic and electron-phonon interactions. The exact values for the centers and linewidths of the Lorentzian functions at temperatures of 200 K and 50 K are provided in Table S1 of the Supplementary Material. Both at M and L, the phonons highlighted in blue (\({M}_{1}^{+},{L}_{2}^{-}\)) experience such a substantial broadening that they become imperceptible to the eye. This suggests that the electron-phonon linewidth renders this mode experimentally inaccessible, implying that the softening goes unnoticed, reconciling our theoretical results with the experiments28,29,33. The remaining modes at L are well-described by Lorentzian curves, exhibiting a slight broadening as the temperature increases, consistent with the expected impact of anharmonicity.

a, b Fully anharmonic spectral function for the M and L points at various temperatures. While no evident softening is observed at the M point, the L point exhibits a noticeable softening of a peak at approximately ~40 cm−1. Due to the large anharmonic effects, this peak splits into a double peak as the temperature lowers. c, d Employing a no-mixing approximation by discarding the off-diagonal elements of the self-energy allows for the independent tracking of different modes, as indicated by different colors. The complete anharmonic spectral functions from (a and b) are also overlaid. e, f Here, we fit a Lorentzian function to each of the individual modes in (c, d) and add the corresponding electron-phonon linewidth to each of the modes.

Symmetry analysis of the potential resulting phases

Based on our previous findings, we expect that the CDW transition manifests as either a Landau-type phase transition or a subtle first-order transition. This, together with the observation that the \({M}_{1}^{+}\) mode is stabilized by anharmonic effects, provides an opportunity to explore the potential phase transitions permitted by group theory65. By independently varying the amplitudes of each component within the three-dimensional order parameter \({{{{\bf{Q}}}}}=\left({L}_{1},{L}_{2},{L}_{3}\right)\), we identify six distinct possible space groups. Each of these distortions imprints a characteristic pattern between two adjacent kagome lattices as shown in Fig. 5. The resulting space groups are also predicted to exhibit characteristic Raman and infrared spectra, featuring varying numbers of peaks that transform under distinct symmetries (see Table S3). The phonon responsible for the symmetry breaking is expected to transform under the trivial representation Ag of the low-symmetry group. This is because the symmetries that leave this phonon invariant are precisely the ones preserved in the low-symmetry phase. Given that the identity or trivial representation is always contained in [V]2 (the symmetrized square of the vector representation), the mode responsible for the symmetry breaking will always be Raman active in the low-symmetry phase. However, its observation will be hindered because of its large phonon broadening. These distinctions in Raman and infrared activities may offer a robust method for discerning the low-symmetry structure. This stands in contrast to energetic arguments, which can be notably unreliable due to the minute energy differences between phases and the neglect of certain contributions, such as anharmonicity.

Different colors distinguish between different bond lengths within the distorted kagome lattices of vanadium atoms. The most symmetric configuration, depicted in subfigure (c), corresponds to what is usually referred in the literature as a stack of star-of-david and tri-hexagonal (inverse-star-of-david) configurations. The remaining distortions either represent distorted versions of (c) (a, b) or a stack of star-of-david configurations, but with the stars being deformed in some form (d–f).

Conclusions

In summary, our calculations show that the CDW transition in CsV3Sb5 is primarily driven by the large electron-phonon coupling within the system, while the melting of the CDW can be attributed to the robust anharmonic effects of the lattice. The CDW is exclusively triggered by the unstable phonons at the L point, with the M phonons not assuming a pivotal role. Despite the phase transition being of second-order or weak first-order character, an examination of the spectral function at the L point suggests that observing this softening experimentally is impossible29. All in all, in contrast to the pure kagome CDW, which is prototypically nesting-driven and strictly two-dimensional, the CsV3Sb5 CDW exhibits notable deviations being purely three-dimensional and driven by the electron-phonon coupling. The remarkable agreement between our results and experimental data suggests that the CDW mechanism can be studied independently from the phenomena emerging in the CDW phase and that lattice quantum anharmonic effects may also wield a crucial influence on the novel physics in the CDW state. We anticipate a similar impact of the electron-phonon coupling and anharmonicity on other kagome families66,67,68,69, as well as the presence of anomalous phonon spectral functions. For instance, the discrepancy observed in 166 compounds between the phonon collapse and the CDW order66 might be attributed to the phonon responsible for the CDW order going unnoticed because of its large linewidth. On the other hand, the absence of a CDW in titanium-based CsTi3Bi5 kagome compounds67 likely results from a distinct balance between the stabilizing role of anharmonicity and electron-phonon destabilizing forces.

Methods

First-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted using the Quantum Espresso package70,71. We used the generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof parameterization72 together with projector-augmented wave pseudopotentials73 generated by Dal Corso74 and considering 9/5/13 valence electrons for cesium/antimony/vanadium. Unless stated otherwise, we used energy cutoffs of 60/600 Ry for the wavefunctions/density with a Methfessel-Paxton smearing75 of 0.002 Ry for the calculations. The structural relaxation and DFPT calculations were performed using a 16 × 16 × 10 grid, without accounting for spin-orbit coupling (SOC), and internal relaxations were done with the experimental lattice parameters given in12 and stopped when forces were below 0.001 Ry/au. Subsequently, SOC was included to compute the electronic band structures and Fermi surfaces (see Fig. 1). The calculations using Fermi-Dirac smearing were done with an 18 × 18 × 12 k-grid and with smearings ranging from 0.0001 Ry up to 0.0065 Ry. To generate the Fermi surface plots, we employed the Wannierization procedure implemented in Wannier9076, along with WannierTools77. First, we obtained a tight-binding model with a Wannierization considering d and p orbitals in vanadium and antimony sites. Then, we calculated the Fermi surface as implemented in WannierTools for a 200 × 2000 × 100 grid. Harmonic phonons were computed using density functional perturbation theory (DFPT)78 within a 6 × 6 × 4 phonon grid. The anharmonic temperature-dependent phonon calculations were done under the Stochastic Self-Consistent Harmonic Approximation (SSCHA)60,61,62 as implemented in the SSCHA code63. In order to capture all the relevant high-symmetry points, the free energy Hessians (SSCHA anharmonic phonons) were done with the inclusion of fourth-order force constants in a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell, which naturally captures the Γ, A, M, and L points. The Brillouin zone integrals for the supercell calculations were performed with a 7 × 7 × 4 k-grid (equivalent to a 14 × 14 × 8 grid in the primitive cell). The dynamical extension of the theory61,79 was used to compute the spectral function within the so-called bubble approximation for the self-energy. The calculation considered phonon-phonon scattering on a 2 × 2 × 2 and a 0.1 cm−1 Gaussian smearing was used to approximate the Dirac deltas.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All codes used in this study are open-source and available from their respective websites.

References

Syôzi, I. Statistics of kagomé lattice. Prog. Theor. Phys. 6, 306–308 (1951).

Călugăru, D. et al. General construction and topological classification of crystalline flat bands. Nat. Phys. 18, 185–189 (2022).

Kang, M. et al. Topological flat bands in frustrated kagome lattice CoSn. Nat. Commun. 11, 4004 (2020).

Kang, M. et al. Dirac fermions and flat bands in the ideal kagome metal FeSn. Nat. Mater. 19, 163–169 (2020).

Bilitewski, T. Disordered flat bands on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 98, 235109 (2018).

Ghimire, N. J. & Mazin, I. I. Topology and correlations on the kagome lattice. Nat. Mater. 19, 137–138 (2020).

Mazin, I. I. et al. Theoretical prediction of a strongly correlated Dirac metal. Nat. Commun. 5, 4261 (2014).

Zhao, H. et al. Cascade of correlated electron states in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Nature 599, 216–221 (2021).

Guo, C. et al. Correlated order at the tipping point in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nat. Phys. 20, 579–584 (2024).

Sachdev, S. Kagomé- and triangular-lattice Heisenberg antiferromagnets: ordering from quantum fluctuations and quantum-disordered ground states with unconfined bosonic spinons. Phys. Rev. B 45, 12377–12396 (1992).

Yin, J.-X., Lian, B. & Hasan, M. Z. Topological kagome magnets and superconductors. Nature 612, 647–657 (2022).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. New kagome prototype materials: discovery of KV3Sb5, RbV3Sb5, and CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 094407 (2019).

Guo, C. et al. Switchable chiral transport in charge-ordered kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nature. 611, 1–6 (2022).

Guo, C. et al. Distinct switching of chiral transport in the kagome metals KV3Sb5 and CsV3Sb5. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 20 (2024).

Farhang, C., Wang, J., Ortiz, B. R., Wilson, S. D. & Xia, J. Unconventional specular optical rotation in the charge ordered state of Kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 14, 5326 (2023).

Yu, L. et al. Evidence of a hidden flux phase in the topological kagome metal CsV3Sb5. arXiv:2107.10714 [cond-mat] (2021).

Feng, X., Jiang, K., Wang, Z. & Hu, J. Chiral flux phase in the kagome superconductor AV3Sb5. Sci. Bull. 66, 1384–1388 (2021).

Mielke, C. et al. Time-reversal symmetry-breaking charge order in a kagome superconductor. Nature 602, 245–250 (2022).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. CsV3Sb5: A\({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) topological kagome metal with a superconducting ground state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 247002 (2020).

Tan, H., Liu, Y., Wang, Z. & Yan, B. Charge density waves and electronic properties of superconducting kagome metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 046401 (2021).

Chen, H. et al. Roton pair density wave in a strong-coupling kagome superconductor. Nature 599, 222–228 (2021).

Zhao, C. C. et al. Nodal superconductivity and superconducting domes in the topological Kagome metal CsV3Sb5. arXiv:2102.08356 [cond-mat] (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Nature of unconventional pairing in the kagome superconductors AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 177001 (2021).

Ge, J. et al. Charge-4 e and Charge-6 e Flux Quantization and Higher Charge Superconductivity in Kagome Superconductor Ring Devices. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021025 (2024).

Le, T. et al. Superconducting diode effect and interference patterns in kagome CsV3Sb5. Nature 630, 64–69 (2024).

Ratcliff, N., Hallett, L., Ortiz, B. R., Wilson, S. D. & Harter, J. W. Coherent phonon spectroscopy and interlayer modulation of charge density wave order in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, L111801 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Observation of unconventional charge density wave without acoustic phonon anomaly in kagome superconductors AV3Sb5 (A = Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. X 11, 031050 (2021).

Liu, G. et al. Observation of anomalous amplitude modes in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 13, 3461 (2022).

Subires, D. et al. Order-disorder charge density wave instability in the kagome metal (Cs,Rb)V3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 14, 1015 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. Three-state nematicity and magneto-optical Kerr effect in the charge density waves in kagome superconductors. Nat. Phys. 18, 1470–1475 (2022).

Nie, L. et al. Charge-density-wave-driven electronic nematicity in a kagome superconductor. Nature 604, 59–64 (2022).

Kang, M. et al. Charge order landscape and competition with superconductivity in kagome metals. Nat. Mater. 22, 186–193 (2023).

He, G. et al. Anharmonic strong-coupling effects at the origin of the charge density wave in CsV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 15, 1895 (2024).

Stahl, Q. et al. Temperature-driven reorganization of electronic order in CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 105, 195136 (2022).

Ortiz, B. R. et al. Fermi surface mapping and the nature of charge density wave order in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041030 (2021).

Broyles, C. et al. Effect of the interlayer ordering on the fermi surface of kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5 revealed by quantum oscillations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 157001 (2022).

Xiao, Q. et al. Coexistence of multiple stacking charge density waves in kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, L012032 (2023).

Khasanov, R. et al. Time-reversal symmetry broken by charge order in CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023244 (2022).

Shan, Z. et al. Muon spin relaxation study of the layered kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 033145 (2022).

Saykin, D. R. et al. High resolution polar Kerr effect studies of CsV3Sb5: tests for time-reversal symmetry breaking below the charge-order transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 016901 (2023).

Christensen, M. H., Birol, T., Andersen, B. M. & Fernandes, R. M. Theory of the charge density wave in AV3Sb5 kagome metals. Phys. Rev. B 104, 214513 (2021).

Jiang, Y.-X. et al. Unconventional chiral charge order in kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat. Mater. 20, 1353–1357 (2021).

Denner, M. M., Thomale, R. & Neupert, T. Analysis of charge order in the kagome metal AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 217601 (2021).

Lin, Y.-P. & Nandkishore, R. M. Complex charge density waves at Van Hove singularity on hexagonal lattices: Haldane-model phase diagram and potential realization in the kagome metals AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. B 104, 045122 (2021).

Jin, J.-T., Jiang, K., Yao, H. & Zhou, Y. Interplay between pair density wave and a nested Fermi surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 167001 (2022).

Deng, J., Zhang, R., Xie, Y., Wu, X. & Wang, Z. Two elementary band representation model, Fermi surface nesting, and surface topological superconductivity in AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. B 108, 115123 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Electron-phonon coupling in the charge density wave state of CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 105, L140501 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Electronic nature of chiral charge order in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 104, 075148 (2021).

Neupert, T., Denner, M. M., Yin, J.-X., Thomale, R. & Hasan, M. Z. Charge order and superconductivity in kagome materials. Nat. Phys. 18, 137–143 (2022).

Wang, C., Liu, S., Jeon, H., Jia, Y. & Cho, J.-H. Charge density wave and superconductivity in the kagome metal CsV3Sb5 around a pressure-induced quantum critical point. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 094801 (2022).

Frachet, M. et al. Colossal c-Axis Response and Lack of Rotational Symmetry Breaking within the Kagome Planes of the CsV 3 Sb 5 Superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 186001 (2024).

Weber, F. et al. Extended phonon collapse and the origin of the charge-density wave in 2H–NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 107403 (2011).

Diego, J. et al. Van der Waals driven anharmonic melting of the 3D charge density wave in VSe2. Nat. Commun. 12, 598 (2021).

Bianco, R., Monacelli, L., Calandra, M., Mauri, F. & Errea, I. Weak dimensionality dependence and dominant role of ionic fluctuations in the charge-density-wave transition of NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 106101 (2020).

Ferrari, F., Becca, F. & Valentí, R. Charge density waves in kagome-lattice extended Hubbard models at the van Hove filling. Phys. Rev. B 106, L081107 (2022).

Subedi, A. Hexagonal-to-base-centered-orthorhombic 4Q charge density wave order in kagome metals KV3Sb5, RbV3Sb5 and CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 015001 (2022).

Bianco, R., Errea, I., Monacelli, L., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Quantum enhancement of charge density wave in NbS2 in the two-dimensional limit. Nano Lett. 19, 3098–3103 (2019).

Gutierrez-Amigo, M. et al. Purely anharmonic charge density wave in the two-dimensional Dirac semimetal snp. Phys. Rev. B 109, 174112 (2024).

Ptok, A. et al. Dynamical study of the origin of the charge density wave in AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs compounds. Phys. Rev. B 105, 235134 (2022).

Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Anharmonic free energies and phonon dispersions from the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: application to platinum and palladium hydrides. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064302 (2014).

Bianco, R., Errea, I., Paulatto, L., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Second-order structural phase transitions, free energy curvature, and temperature-dependent anharmonic phonons in the self-consistent harmonic approximation: theory and stochastic implementation. Phys. Rev. B 96, 014111 (2017).

Monacelli, L., Errea, I., Calandra, M. & Mauri, F. Pressure and stress tensor of complex anharmonic crystals within the stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024106 (2018).

Monacelli, L. et al. The stochastic self-consistent harmonic approximation: calculating vibrational properties of materials with full quantum and anharmonic effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 363001 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Three-dimensional Fermi surfaces from charge order in layered CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 106, 064510 (2022).

Stokes, H. T. & Hatch, D. M. Isotropy Subgroups of the 230 Crystallographic Space Groups (World Scientific, Singapore, Teaneck, NY, USA, 1988).

Korshunov, A. et al. Softening of a flat phonon mode in the kagome ScV6Sn6. Nat. Commun. 14, 6646 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Electronic nematicity without charge density waves in titanium-based kagome metal. Nat. Phys. 19, 1591–1598 (2023).

Teng, X. et al. Magnetism and charge density wave order in kagome FeGe. Nat. Phys. 19, 814–822 (2023).

Dong, H. et al. Emergent electronic kagome lattice in correlated charge-density-wave state of 1T-TaS2. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.05885 (2023).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Corso, A. Pseudopotentials periodic table: from H to Pu. Comput. Mater. Sci. 95, 337–350 (2014).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Wu, Q., Zhang, S., Song, H.-F., Troyer, M. & Soluyanov, A. A. WannierTools: an open-source software package for novel topological materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 224, 405–416 (2018).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Monacelli, L. & Mauri, F. Time-dependent self-consistent harmonic approximation: anharmonic nuclear quantum dynamics and time correlation functions. Phys. Rev. B 103, 104305 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with J.L. Mañes. M.G.V., I.E., and M.G.A acknowledge the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (grants PID2019-109905GB-C21, PID2022-142008NB-I00, and PID2022-142861NA-I00). I.E. acknowledges the Department of Education, Universities, and Research of the Eusko Jaurlaritza and the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU (Grant No. IT1527-22). M.G.A. thanks the Department of Education of the Basque Government for a predoctoral fellowship (Grant no. PRE_2019_1_0304). M.G.V. and C.F. thank support to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) GA 3314/1-1—FOR 5249 (QUAST) and partial support from European Research Council (ERC) grant agreement no. 101020833. This work has also been funded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation of the Spanish Government through the QUANTUM ENIA project call—Quantum Spain project and by the European Union through the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan—NextGenerationEU within the framework of the Digital Spain 2026 Agenda. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program XBEND (Grant agreement No. 101080740).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.E. and M.G.V. conceived and supervised the project, and also revised the manuscript. M.G.-A. carried out the calculations and drafted the manuscript. The results were discussed with C.G., P.J.W.M., and D.D., who also reviewed the manuscript and contributed suggestions. C.F. and I.E. provided the computational resources. All authors contributed to data analysis and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications materials thank the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Aldo Isidori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutierrez-Amigo, M., Dangić, Ð., Guo, C. et al. Phonon collapse and anharmonic melting of the 3D charge-density wave in kagome metals. Commun Mater 5, 234 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00676-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00676-0

This article is cited by

-

Frustrated magnetism, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of titanium-based kagome materials

Journal of Materials Science (2026)

-

Charge-density-wave quantum critical point under pressure in 2H-TaSe2

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Many-body interference in kagome crystals

Nature (2025)

-

Chirality meets topology: building quantum bridges to catalysis

La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento (2025)

-

Origin of competing charge density waves in kagome metal ScV6Sn6

Nature Communications (2024)